Analysis of the Effect of Reinforced Insulation Design Standards on Energy Performance to Establish ZEB Strategies for Non-Residential Buildings

Abstract

1. Introduction

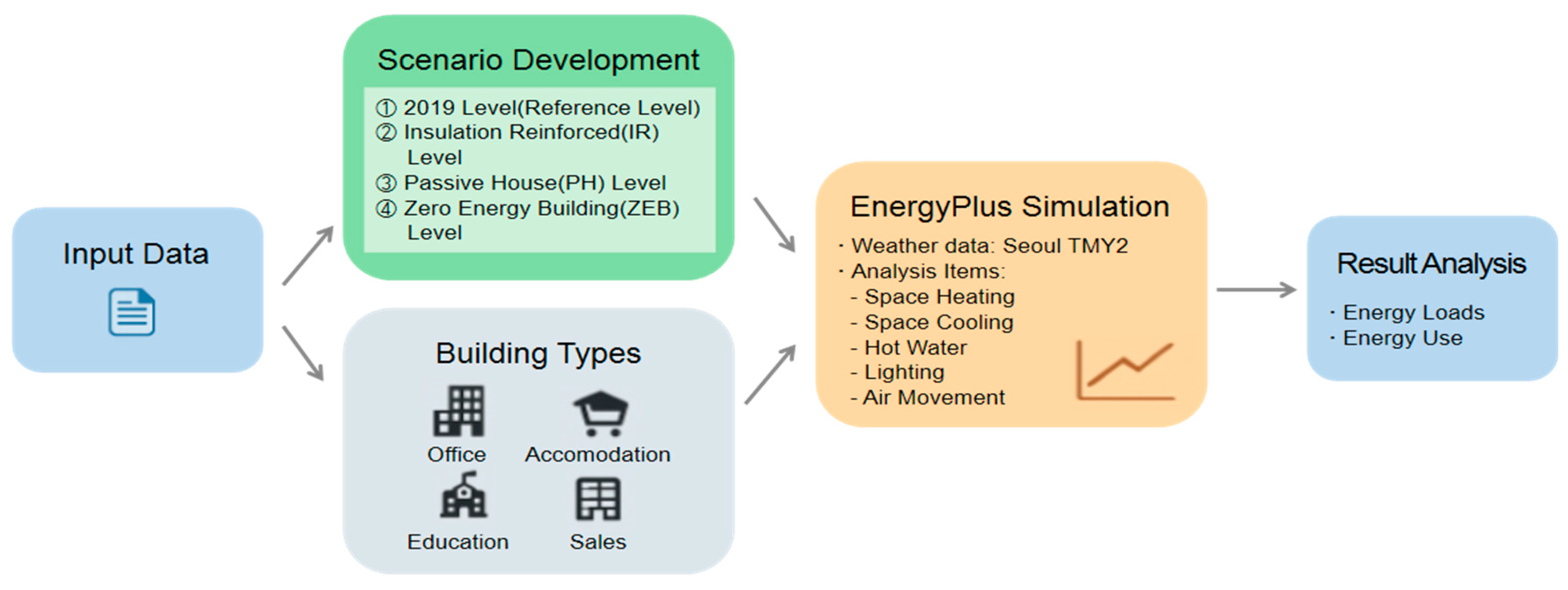

2. Methods

2.1. Object of Research

2.2. Building Energy Analysis Simulation

3. Literature Review

4. Policy Scenarios for Insulation Standards

4.1. Insulation Performance Scenarios

- Reference Level: Based on the 2019 building energy code (used as the baseline year) [22]

- Insulation reinforced level: Improved envelope U-values compared to the reference level [20]

- Passive house level: High insulation and airtightness to meet U-values ≤ 0.15 W/m2·K for the envelope and ≤1.2 W/m2·K for windows, as per Passive House Institute guidelines [23]

- ZEB level: Design standards including enhanced load reduction measures (e.g., SHGC reduction) in addition to improved envelope U-values for ZEB implementation

- (1)

- Reference level

- (2)

- Insulation reinforced level

- (3)

- Passive house level

- (4)

- ZEB level

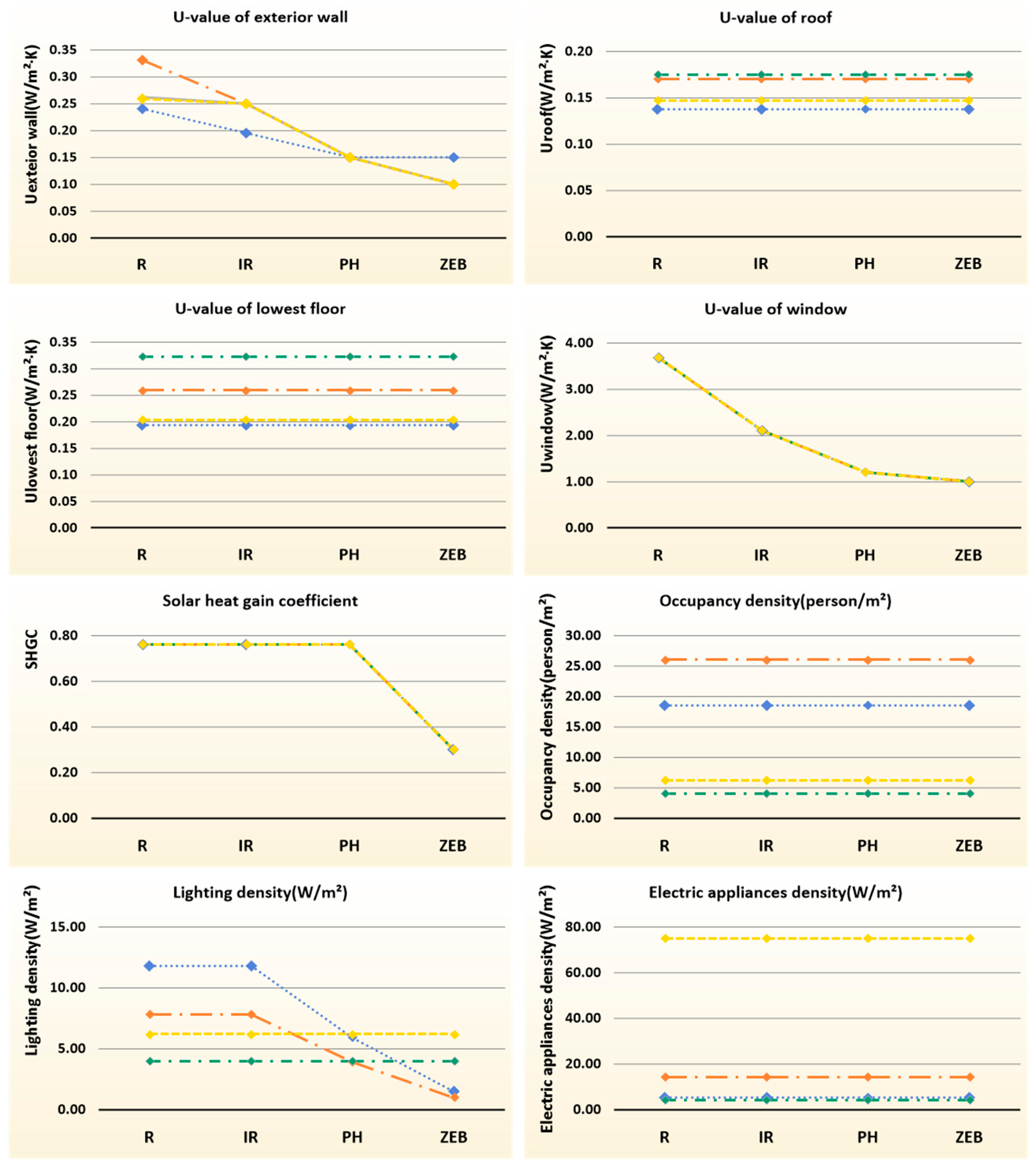

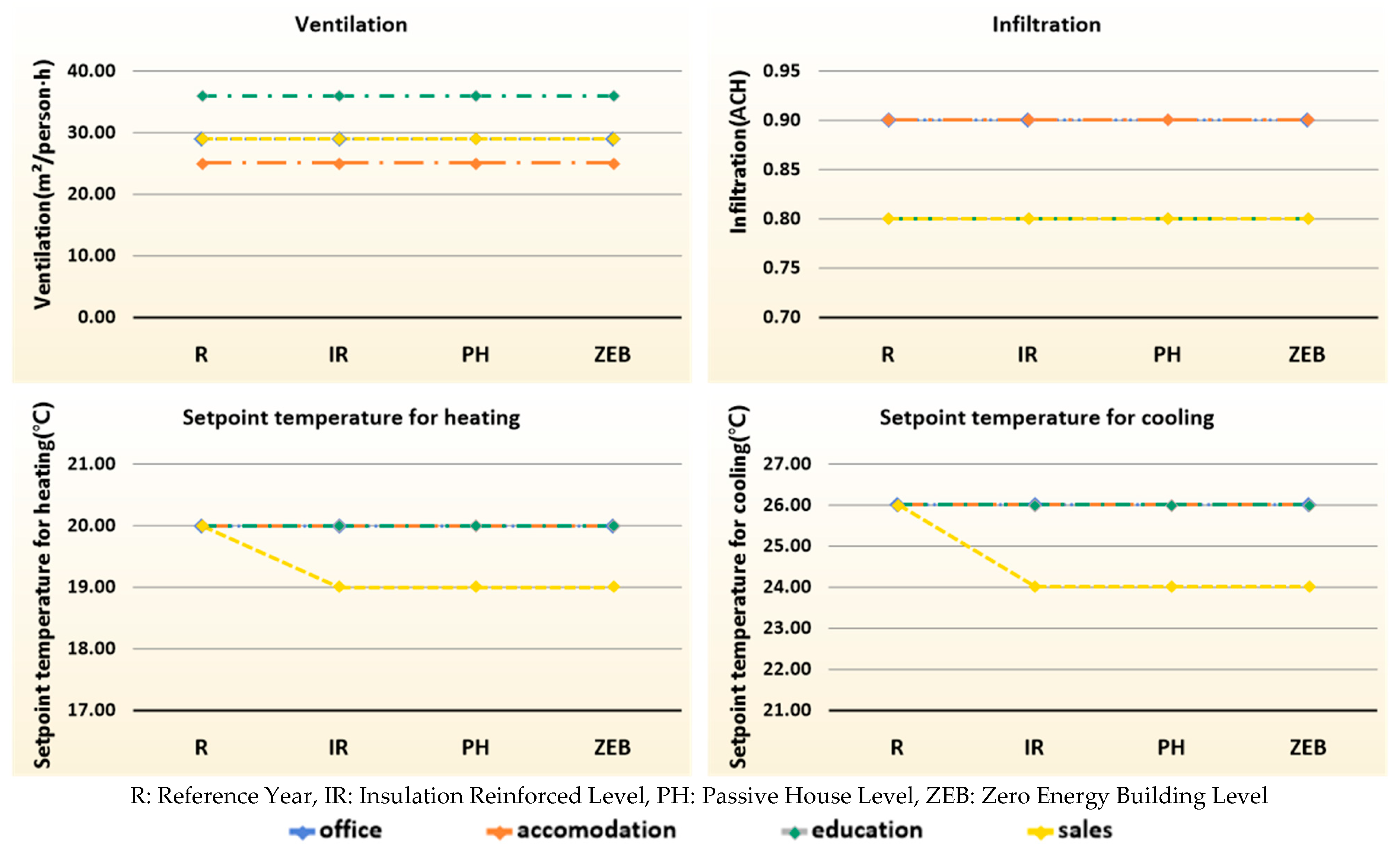

4.2. Data Configuration by Scenario

- Envelope U-values: These decreased with higher scenario levels for all building types, indicating improved insulation performance. For instance, the office building’s exterior wall U-value dropped from 0.240 W/m2·K under the baseline to 0.150 W/m2·K at the ZEB level—an improvement of about 37.5%. Similar improvements were observed in the other building types. Notably, window U-values at the ZEB level were set to 1.000 W/m2·K or lower, assuming the use of high-performance glazing.

- SHGC: Window SHGC remained constant (0.760) from the reference level through the passive house level but dropped sharply to 0.300 under the ZEB scenario. This reflects the assumed use of solar-control glazing or external shading to mitigate cooling loads, especially relevant in sales facilities with high internal gains.

- Occupancy Density: These values were held constant across scenarios and based on typical usage patterns. Office buildings had the lowest occupancy (0.10 persons/m2), while educational and accommodation facilities were set at 0.20 and 0.40 persons/m2, respectively. Sales facilities were set at 0.15 persons/m2, reflecting average foot traffic and staff presence.

- Lighting Density: Lighting loads decreased significantly at higher scenario levels. For example, office buildings dropped from 11.83 W/m2 under the baseline to 1.48 W/m2 at the ZEB level—an 87.5% reduction. Similar reductions (to ~1.2–1.6 W/m2) were seen in accommodation and sales buildings, reflecting the use of LED lighting and sensor-based controls.

- Electric Equipment Density: This varied by building type and remained constant across scenarios. Offices and educational buildings maintained 13.6–14.0 W/m2, while sales facilities were significantly higher at 75.0 W/m2, reflecting continuous operation of display and POS equipment. Though unchanged across scenarios, this parameter is a key indicator of internal load intensity.

- Infiltration and Ventilation: These were fixed by building type, not scenario. Infiltration was held at 0.90 ACH for all types. Ventilation was higher in office and educational buildings and lower in sales and accommodation facilities, reflecting operational norms rather than insulation standards.

- Set-Point Temperatures: Most building types maintained 20 °C for heating and 26 °C for cooling. However, in sales facilities, the cooling set-point was reduced to 24 °C under the ZEB scenario, reflecting the comfort requirements of cooling-dominant spaces and adjusted operational strategies.

5. Results

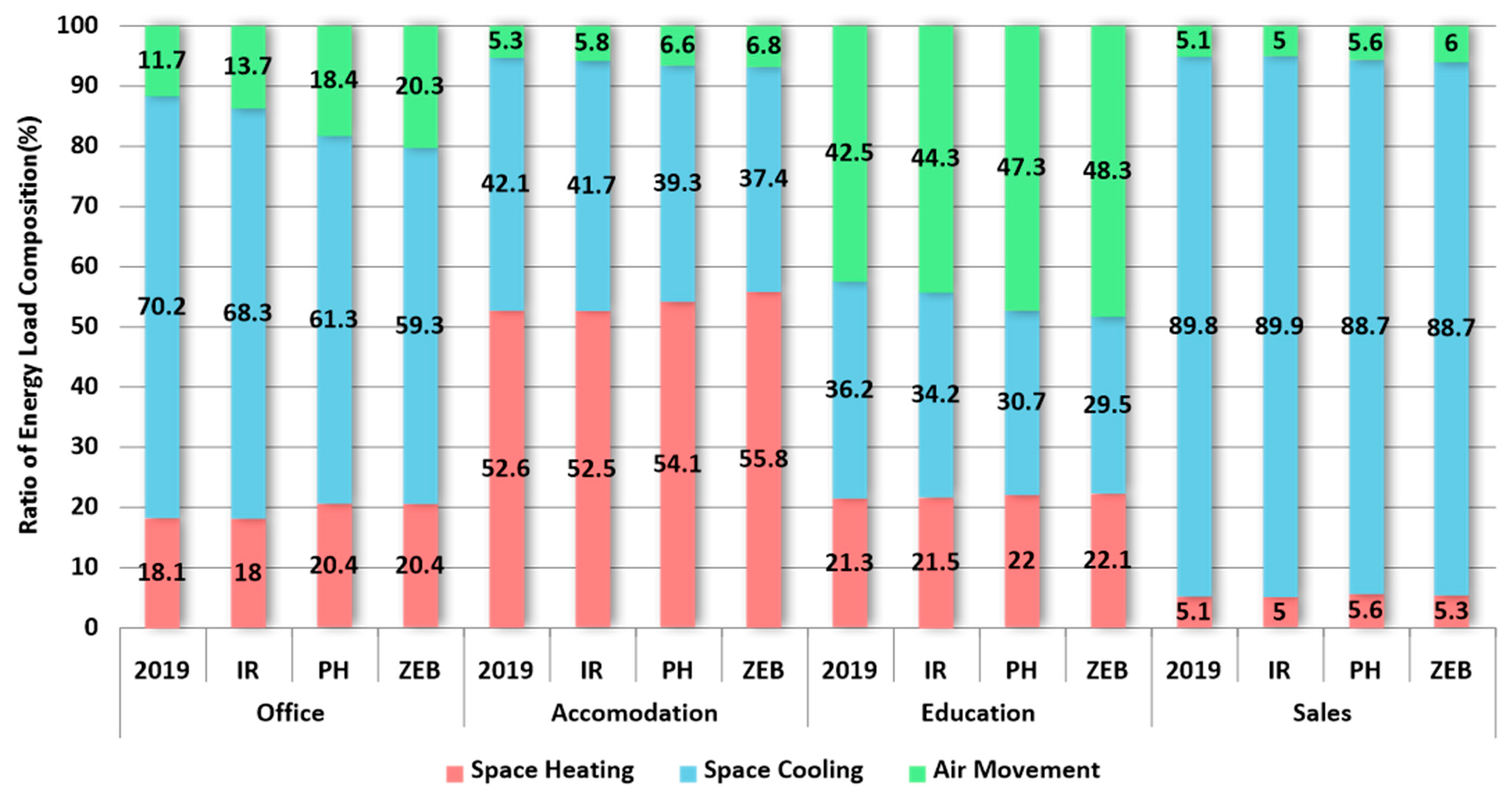

5.1. Energy Load

- (1)

- Office buildings

- (2)

- Accommodation facilities

- (3)

- Educational facilities

- (4)

- Sales facilities

5.2. Energy Consumption

- (1)

- Office buildings

- (2)

- Accommodation facilities

- (3)

- Educational facilities

- (4)

- Sales facilities

5.3. Reference Building Model Validation

- Heating: 47.5 kWh/m2 (this study) vs. 36.6 kWh/m2 [28]

- Ventilation: 13.5 kWh/m2 vs. 5.2 kWh/m2

- Cooling: 60.7 kWh/m2 vs. 25.5 kWh/m2

- Lighting: 52.7 kWh/m2 vs. 15.1 kWh/m2

6. Discussions & ZEB Strategy

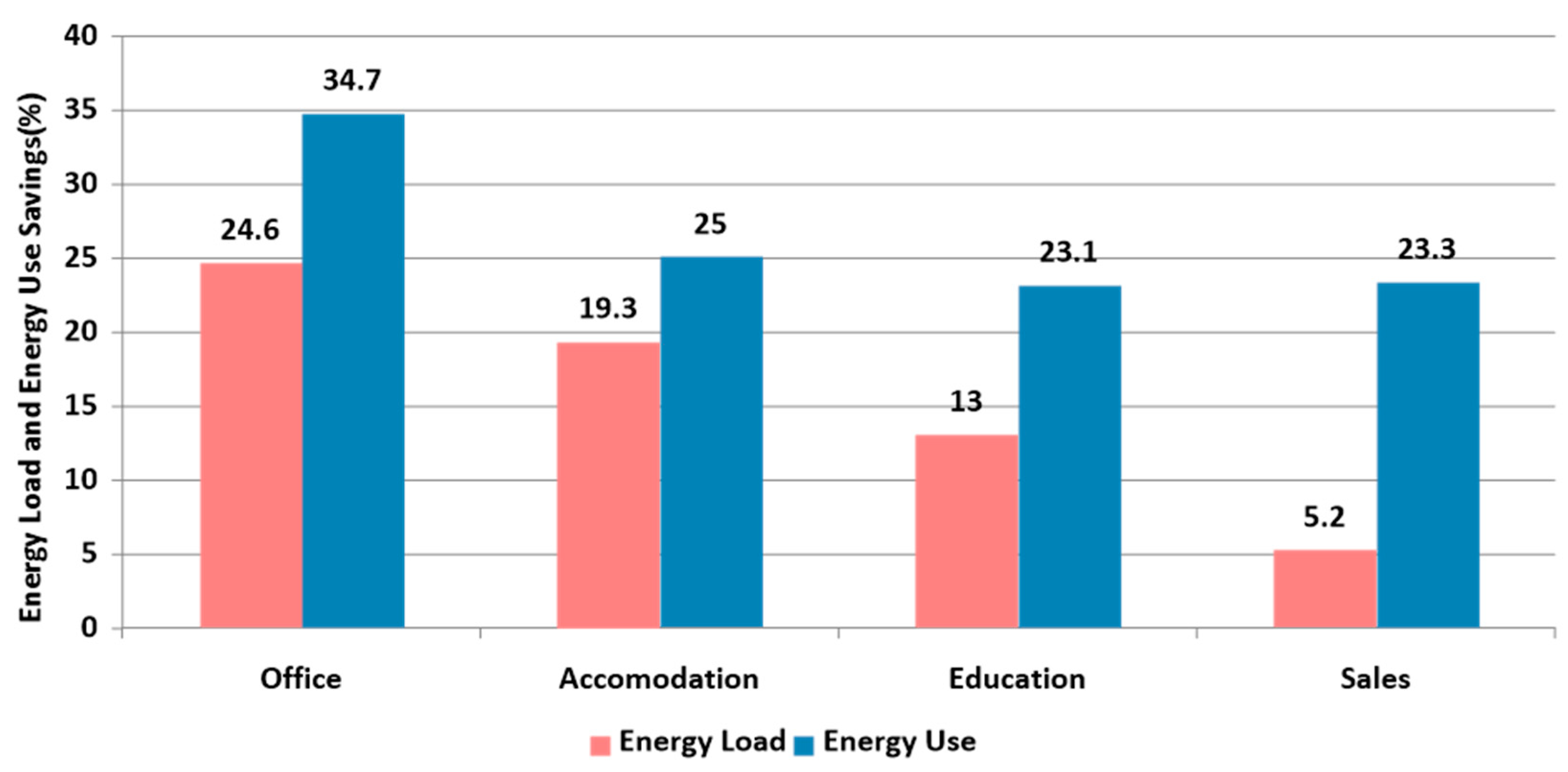

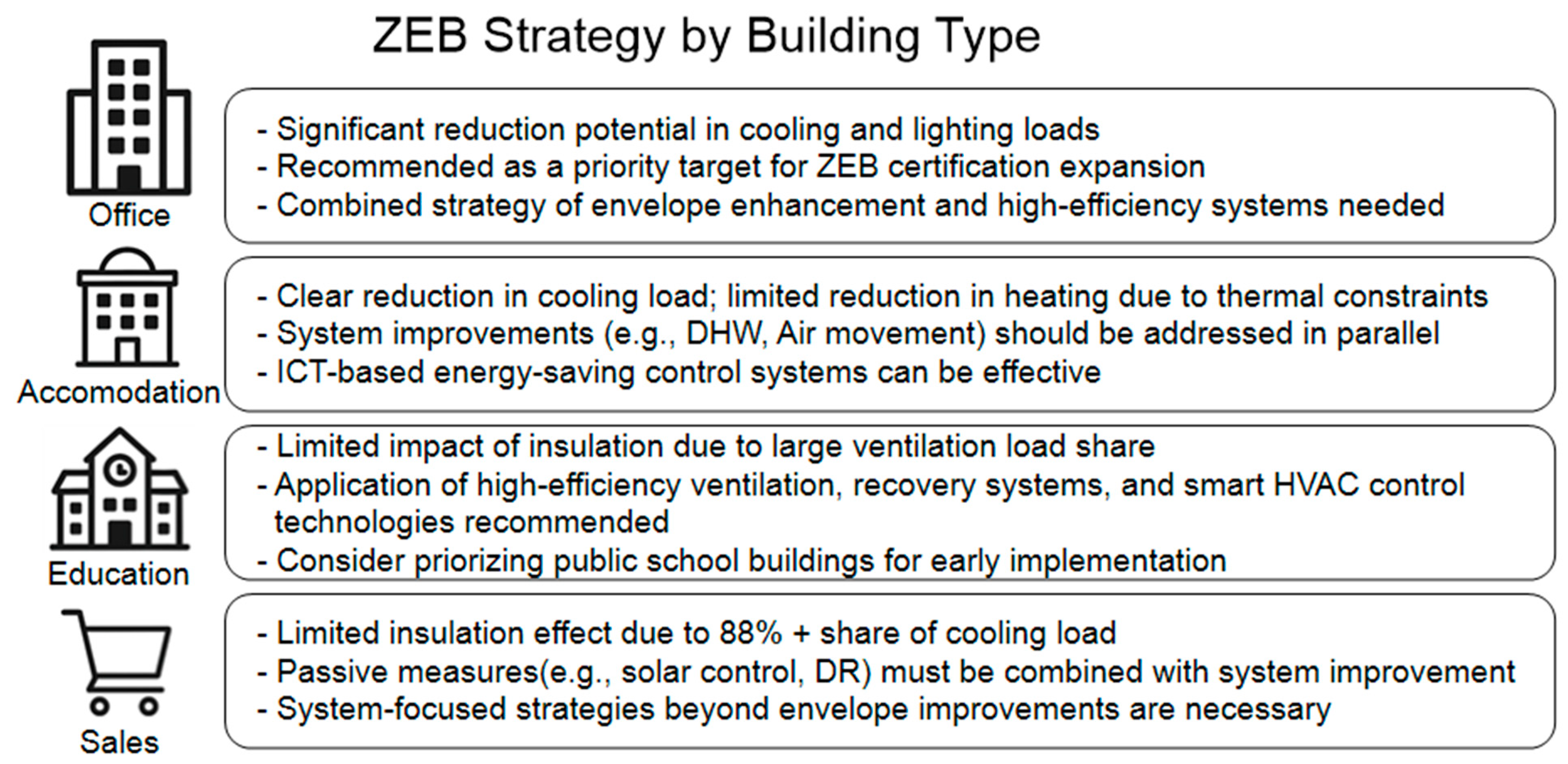

- Office buildings showed the highest performance improvement under the ZEB-level scenario, with a 24.6% reduction in energy load and a 34.7% reduction in total energy consumption. Significant savings came from cooling and lighting energy, reflecting the benefits of high-efficiency lighting and enhanced solar radiation control. Thus, office buildings are strong candidates for ZEB certification prioritization and policy incentives.

- Accommodation facilities achieved a 25.0% reduction in total energy consumption, with primary savings in cooling and lighting. However, domestic hot water and ventilation energy remained nearly unchanged across scenarios, suggesting that equipment efficiency improvements in these areas are necessary to achieve further reductions.

- Educational facilities saw a 23.1% decrease in energy consumption, mainly from cooling and lighting. However, ventilation energy accounted for over 40% of the total load and remained constant across insulation scenarios. This highlights the need to install high-efficiency ventilation systems and heat-recovery devices, and to adopt smart control technologies to improve indoor air quality while reducing heating and cooling demand.

- Sales facilities had the most cooling-intensive load structure, with cooling accounting for over 88% of the total energy load. In some scenarios, the cooling load even increased due to thermal storage effects from improved insulation. The total energy reduction was only 23.3% under the ZEB scenario, highlighting that insulation-focused strategies alone are insufficient. Therefore, a comprehensive approach combining high-efficiency cooling systems, advanced glazing or dynamic shading, and night ventilation should be prioritized for these building types.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Building Type | Office | Accommodation | ||||||||

| Input Parameters | R | IR | PH | ZEB | R | IR | PH | ZEB | ||

| U-value | Exterior Wall | W/m2·K | 0.240 | 0.195 | 0.150 | 0.150 | 0.331 | 0.250 | 0.150 | 0.100 |

| Roof | W/m2·K | 0.138 | 0.138 | 0.138 | 0.138 | 0.170 | 0.170 | 0.170 | 0.170 | |

| Lowest Floor | W/m2·K | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.259 | 0.259 | 0.259 | 0.259 | |

| Window | W/m2·K | 3.675 | 2.100 | 1.200 | 1.000 | 3.675 | 2.100 | 1.200 | 1.000 | |

| Solar Heat Gain Coefficient | Window | - | 0.760 | 0.760 | 0.760 | 0.300 | 0.760 | 0.760 | 0.760 | 0.300 |

| Internal Heat Gain | Occupancy Density | peron/m2 | 18.58 | 18.58 | 18.58 | 18.58 | 26.01 | 26.01 | 26.01 | 26.01 |

| Lighting Density | W/m2 | 11.83 | 11.83 | 5.91 | 1.48 | 7.84 | 7.84 | 3.92 | 0.98 | |

| Electric Appliances Density | W/m2 | 5.25 | 5.25 | 5.25 | 5.25 | 14.30 | 14.30 | 14.30 | 14.30 | |

| Etc. | Ventilation | m3/person·h | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 |

| Infiltration | ACH | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | |

| Set-Point Temperature | Heating | °C | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Cooling | °C | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | |

| Building Type | Education | Sales | ||||||||

| Input Parameters | R | IR | PH | ZEB | R | IR | PH | ZEB | ||

| U-value | Exterior Wall | W/m2·K | 0.262 | 0.250 | 0.150 | 0.100 | 0.259 | 0.250 | 0.150 | 0.100 |

| Roof | W/m2·K | 0.175 | 0.175 | 0.175 | 0.175 | 0.147 | 0.147 | 0.147 | 0.147 | |

| Lowest Floor | W/m2·K | 0.323 | 0.323 | 0.323 | 0.323 | 0.204 | 0.204 | 0.204 | 0.204 | |

| Window | W/m2·K | 3.675 | 2.100 | 1.200 | 1.000 | 3.675 | 2.100 | 1.200 | 1.000 | |

| Solar Heat Gain Coefficient | Window | - | 0.760 | 0.760 | 0.760 | 0.300 | 0.760 | 0.760 | 0.760 | 0.300 |

| Internal Heat Gain | Occupancy Density | peron/m2 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 6.19 | 6.19 | 6.19 | 6.19 |

| Lighting Density | W/m2 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 1.72 | 0.43 | 10.20 | 10.20 | 5.10 | 1.28 | |

| Electric Appliances Density | W/m2 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 75.00 | 75.00 | 75.00 | 75.00 | |

| Etc. | Ventilation | m3/person·h | 36.00 | 36.00 | 36.00 | 36.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 |

| Infiltration | ACH | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | |

| Set-Point Temperature | Heating | °C | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Cooling | °C | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 24 | 24 | 24 | |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Technology Perspectives 2020; IEA: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-technology-perspectives-2020 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- 2050 Presidential Commission on Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth. 2050 Carbon Neutrality Scenario (Draft): Material for Establishing Carbon Neutrality Vision for the New Administration; 2050 Presidential Commission on Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). The Third Green Building Master Plan (2021–2025); Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT): Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, Y.; Kang, J.-A.; Huh, J.-H.; Jeong, Y.-S.; Huh, J.-H. Development and application of a flexible modeling approach to reference buildings for energy analysis. Energies 2020, 13, 5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.; Kang, J.-A.; Huh, J.-H.; Kim, T.-H.; Jeong, Y.-S. An analysis of the effectiveness of greenhouse gas reduction policy for office building design in South Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Kim, Y.M.; Lee, S.H.; Park, W.Y.; Bok, Y.J.; Ha, S.K.; Lee, S.Y. Development of reference building energy models for South Korea. In Proceedings of the 15th IBPSA Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 7–9 August 2017; pp. 2693–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, M.; Mathur, J.; Garg, V. Development of reference building models for India. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 21, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.; Ghisi, E. Method for obtaining reference buildings. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraldi, M.; Garlet, L.; Gapski, N.; Quevedo, T.; Melo, A.P.; Lamberts, R. Developing reference building models for the non-residential sector to support public policies in Brazil. Energy Build. 2025, 332, 115419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão de Vasconcelos, A.; Almeida, M.; Ferreira, M. A Portuguese approach to define reference buildings for cost-optimal methodologies. Appl. Energy 2015, 140, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; McCuskey Shepley, M.; Choi, J. Exploring the effects of a building retrofit to improve energy performance and sustainability: A case study of Korean public buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 25, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krarti, M. Evaluation of large-scale building energy efficiency retrofit program in Kuwait. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Energy Agency. 2023 Energy Consumption Statistics in the Building Sector; Building Energy Information Center, Korea Energy Agency: Ulsan, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Crawley, D.B.; Lawrie, L.K.; Winkelmann, F.C.; Buhl, W.F.; Huang, Y.J.; Pedersen, C.O.; Glazer, J. EnergyPlus: Creating a new-generation building energy simulation program. Energy Build. 2001, 33, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deru, M.; Field, K.; Studer, D.; Benne, K.; Griffith, B.; Torcellini, P.; Halverson, M.U.S. DOE Commercial Reference Building Models of the National Building Stock (NREL/TP-5500-46861); National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2011. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy11osti/46861.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Ballarini, I.; Corrado, V.; Madrazo, L. Use of reference buildings to assess the energy saving potentials of the residential building stock: The experience of TABULA project. Energy Policy 2014, 68, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Halverson, M.; Delgado, A.; Yu, S. Building energy code compliance in developing countries: The potential role of outcomes-based codes in India. In 2014 ACEEE Summer Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings; American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE): Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 8-61–8-74. [Google Scholar]

- Corgnati, S.P.; Fabrizio, E.; Filippi, M.; Monetti, V. Reference buildings for cost optimal analysis: Method of definition and application. Appl. Energy 2013, 102, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut Wohnen und Umwelt (IWU). Typology Approach for Building Stock Energy Assessment (TABULA); Institut Wohnen und Umwelt (IWU): Darmstadt, Germany, 2010; Available online: https://www.building-typology.eu (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Hong, T.; Sun, K.; Chen, Y.; Taylor-Lange, S.C.; Yan, D. An occupant behavior modeling tool for co-simulation. Energy Build. 2020, 207, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.S.; Jung, H.K.; Jang, H.K.; Yu, K.H. A study on the reference building based on the building design trends for non-residential buildings. J. Korean Sol. Energy Soc. 2014, 34, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). 2020 Energy Saving Design Standards; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT): Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Passive House Institute Korea. Passive House Requirements. Available online: https://www.phiko.kr (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). Building Energy Efficiency Rating Certification Standards; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT): Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). Regulations on the Operation of the Building Energy Efficiency Rating Certification System; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT): Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). Regulation for Facility in Building; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT): Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). ASHRAE Standard 90.1-2019: Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings; ASHRAE: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.-Y.; Jin, H.-S.; Ha, S.-Y.; Kim, S.-I.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, S.-J.; Suh, I.-A. Detailed office building energy information based on in situ measurements. Energies 2020, 13, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Technology Perspectives 2017; IEA: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-technology-perspectives-2017 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

| Category | Evaluation Model | Researcher | Target Building Type | Major Analysis Variable | Simulation Tool | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | DOE RB model | Deru et al. [15] | 16 building types | Standard design conditions and operating conditions | EnergyPlus |

|

| Europe | TABULA project | IWU et al. (2010) [19] | Residential buildings (representative housing type by country) | Construction year, insulation thickness, design conditions, etc. | PHPP, EnergyPlus |

|

| Brazil | RB model | Schaefer&Ghisi (2016) [8] | Single-family housing | Window configuration and U-value | EnergyPlus |

|

| India | RB model | Bhatnagar et al. (2019) [7] | Office | Form, envelope conditions, systems, etc. | EnergyPlus DesignBuilder |

|

| South Korea | RB model | Hong et al. (2020) [20] | Apartments (mid/low, middle, and high floor levels) | Total floor area, number of floors, window-to-wall ratio, U-value, SHGC, internal heat gain, ACH, etc. | EnergyPlus |

|

| South Korea | RB model | Jeong et al. (2014) [21] | Office | U-value, window-to-wall ratio, boiler efficiency, refrigerator COP, etc. | ECO2 |

|

| South Korea | Present study | Office, accommodation, educational, and sales facilities | Envelope U-value, SHGC, internal heat gain, and insulation level scenarios | EnergyPlus |

|

| Parameter | Unit | Baseline (2019) | Insulation Reinforced | Passive House | ZEB Level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-value | Exterior wall | W/m2·K | 0.240 | 0.195 | 0.150 | 0.150 |

| Roof | W/m2·K | 0.138 | 0.138 | 0.138 | 0.138 | |

| Lowest floor | W/m2·K | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.193 | |

| Window | W/m2·K | 3.675 | 2.100 | 1.200 | 1.000 | |

| Window SHGC | - | 0.760 | 0.760 | 0.760 | 0.300 | |

| Occupancy density | persons/m2 | 0.10–0.40 | 0.10–0.40 | 0.10–0.40 | 0.10–0.40 | |

| Lighting density | W/m2 | 11.83 | ||||

| Equipment density | W/m2 | 13.6–75.0 | 13.6–75.0 | 13.6–75.0 | 13.6–75.0 | |

| Ventilation rate | m3/person·h | 25–36 | 25–36 | 25–36 | 25–36 | |

| Infiltration rate | ACH | 0.8–0.9 | 0.8–0.9 | 0.8–0.9 | 0.8–0.9 | |

| Set-point temperature (Heating/Cooling) | °C | 20/26 | 20/26 | 20/26 | 20/24 | |

| Building Type | Office | Accommodation | ||||||||

| Output | R | IR | PH | ZEB | R | IR | PH | ZEB | ||

| Energy Demand | Space Heating | kWh/m2 | 27.80 | 25.06 | 28.42 | 34.63 | 51.80 | 42.91 | 42.56 | 50.83 |

| Space Cooling | kWh/m2 | 55.60 | 58.55 | 47.29 | 23.46 | 56.37 | 59.86 | 52.69 | 31.25 | |

| Air Circulation | kWh/m2 | 17.09 | 16.82 | 17.19 | 17.67 | 23.10 | 22.61 | 22.50 | 23.78 | |

| Total | kWh/m2 | 100.48 | 100.43 | 92.90 | 75.75 | 131.26 | 125.37 | 117.75 | 105.86 | |

| Energy Use | Space Heating | kWh/m2 | 47.51 | 43.60 | 47.96 | 52.79 | 47.96 | 39.28 | 39.93 | 49.15 |

| Space Cooling | kWh/m2 | 60.67 | 63.51 | 54.66 | 41.75 | 20.47 | 21.66 | 18.88 | 11.23 | |

| Domestic Hot Water | kWh/m2 | 15.56 | 15.54 | 15.56 | 15.56 | 34.76 | 34.76 | 34.76 | 34.76 | |

| Lighting | kWh/m2 | 52.66 | 52.65 | 26.31 | 6.59 | 40.07 | 40.07 | 20.03 | 5.01 | |

| Air Circulation | kWh/m2 | 13.52 | 13.80 | 11.07 | 10.84 | 22.40 | 21.67 | 19.40 | 16.01 | |

| Total | kWh/m2 | 189.92 | 189.09 | 155.55 | 127.53 | 165.66 | 157.43 | 133.01 | 116.16 | |

| Building Type | Education | Sales | ||||||||

| Output | R | IR | PH | ZEB | R | IR | PH | ZEB | ||

| Energy Demand | Space Heating | kWh/m2 | 7.09 | 6.21 | 6.46 | 7.61 | 7.57 | 6.03 | 5.69 | 5.80 |

| Space Cooling | kWh/m2 | 44.13 | 45.95 | 43.90 | 30.58 | 330.58 | 358.38 | 344.82 | 309.88 | |

| Air Circulation | kWh/m2 | 36.24 | 35.68 | 35.66 | 37.89 | 35.43 | 37.96 | 37.90 | 38.55 | |

| Total | kWh/m2 | 87.46 | 87.84 | 86.02 | 76.08 | 373.57 | 402.37 | 388.42 | 354.22 | |

| Energy Use | Space Heating | kWh/m2 | 14.37 | 12.42 | 12.47 | 15.49 | 5.08 | 3.95 | 3.74 | 3.87 |

| Space Cooling | kWh/m2 | 7.72 | 7.88 | 7.32 | 5.02 | 117.00 | 131.89 | 126.47 | 114.03 | |

| Domestic Hot Water | kWh/m2 | 3.07 | 3.07 | 3.07 | 3.07 | 10.55 | 10.55 | 10.55 | 10.55 | |

| Lighting | kWh/m2 | 17.20 | 17.20 | 8.60 | 2.15 | 53.90 | 53.90 | 26.95 | 6.76 | |

| Air Circulation | kWh/m2 | 3.75 | 3.87 | 3.68 | 2.54 | 69.96 | 80.15 | 76.13 | 70.27 | |

| Total | kWh/m2 | 46.11 | 44.44 | 35.14 | 28.27 | 256.49 | 280.44 | 243.84 | 205.48 | |

| Classification | Energy Use (kWh/m2) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This Study | Kim et al. [6] | Deru et al. [15] | Bhatnagar et al. [7] | Song et al. [29] | ||||||

| Space Heating | 47.51 | 25% | 118.5 | 31% | 26.0 | 33% | - | 1% | 36.6 | 27% |

| Space Cooling | 60.67 | 32% | 93.6 | 25% | 21.7 | 27% | - | 20% | 25.5 | 19% |

| Domestic Hot Water (DHW) | 15.56 | 8% | 12.2 | 3% | 5.3 | 7% | - | 15% | 4.2 | 3% |

| Lighting | 52.66 | 28% | 51.0 | 13% | 21.8 | 27% | - | 21% | 15.1 | 11% |

| Air Movement | 13.52 | 7% | 44.7 | 12% | 5.2 | 7% | - | 13% | 5.2 | 4% |

| Others | - | - | 60.5 | 16% | - | - | - | 30% | 47.0 | 35% |

| Total | 189.90 | 100% | 380.5 | 100% | 80.0 | 100% | - | 100% | 133.6 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, H.-S.; Jeong, Y.-S. Analysis of the Effect of Reinforced Insulation Design Standards on Energy Performance to Establish ZEB Strategies for Non-Residential Buildings. Buildings 2025, 15, 4366. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234366

Jin H-S, Jeong Y-S. Analysis of the Effect of Reinforced Insulation Design Standards on Energy Performance to Establish ZEB Strategies for Non-Residential Buildings. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4366. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234366

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Hye-Sun, and Young-Sun Jeong. 2025. "Analysis of the Effect of Reinforced Insulation Design Standards on Energy Performance to Establish ZEB Strategies for Non-Residential Buildings" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4366. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234366

APA StyleJin, H.-S., & Jeong, Y.-S. (2025). Analysis of the Effect of Reinforced Insulation Design Standards on Energy Performance to Establish ZEB Strategies for Non-Residential Buildings. Buildings, 15(23), 4366. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234366