Digital Twin–Based Simulation and Decision-Making Framework for the Renewal Design of Urban Industrial Heritage Buildings and Environments: A Case Study of the Xi’an Old Steel Plant Industrial Park

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Object innovation: Focusing on the unique category of urban industrial heritage, the study proposes a multi-dimensional digital twin modeling method;

- (2)

- Methodological innovation: Achieving deep coupling among ENVI-met (V5.0) microclimate simulation, EnergyPlus building energy analysis, and AnyLogic multi-agent behavioral simulation to quantitatively evaluate the comprehensive performance of design interventions;

- (3)

- Application innovation: Developing a dynamic and visualized multi-criteria decision-support workflow that promotes a paradigm shift in urban regeneration—from experience-based planning toward data-driven and interactive design.

- (1)

- Commonality in spatial structures and forms: Industrial heritage sites typically contain large-scale and structurally robust buildings—such as long-span workshops and tall warehouses—along with spatial patterns shaped by historical production flows, including linear axes and clustered layouts. These distinctive spatial carriers define a universal set of technical challenges in adaptive reuse, including daylighting, ventilation, energy performance, and the reprogramming of large interior volumes.

- (2)

- Commonality in technical systems and performance bottlenecks: Across different regions, traditional industrial buildings share similar deficiencies, such as poor thermal performance of the envelope (e.g., insufficient insulation of brick walls, air leakage around high-level windows), outdated energy systems, and weak microclimate regulation leading to heat-island risks. These shared shortcomings constitute a common baseline for environmental and energy-efficient retrofitting.

- (3)

- Commonality in multi-objective conflicts: Industrial-heritage regeneration inevitably navigates tensions between preservation and renewal, memory and innovation, historic value and contemporary functionality. Balancing multiple objectives—cultural adaptability, environmental comfort, energy efficiency, and spatial vitality—forms a complex decision-making landscape shared by all industrial-heritage renewal projects.

2. Literature Review

2.1. From Manufacturing to Urban Systems: The Paradigm Evolution of Digital Twin

2.2. From Independence to Coupling: Integration of Multi-Physical Field Simulation Technologies in Urban Environments

2.3. From Static Conservation to Smart Regeneration: Paradigm Shifts and Technological Empowerment in Industrial Heritage

- (1)

- At the technological level, the emergence of the Urban Digital Twin (UDT) provides a new methodological foundation for managing and designing complex historical environments. By establishing a data-driven coupling between physical and virtual spaces, UDT enables real-time monitoring, predictive simulation, and decision optimization within urban systems (Deren, L et al., 2021) [29]. The integration of BIM, GIS, and IoT has become the core pathway for constructing city-scale twins. Standardization efforts—such as IFC and City GML—have advanced geometric and semantic interoperability [30,31,32]; however, challenges remain in semantic mapping, spatiotemporal synchronization, and large-scale visualization (e.g., real-time rendering in Unreal, Unity, or Cesium environments).

- (2)

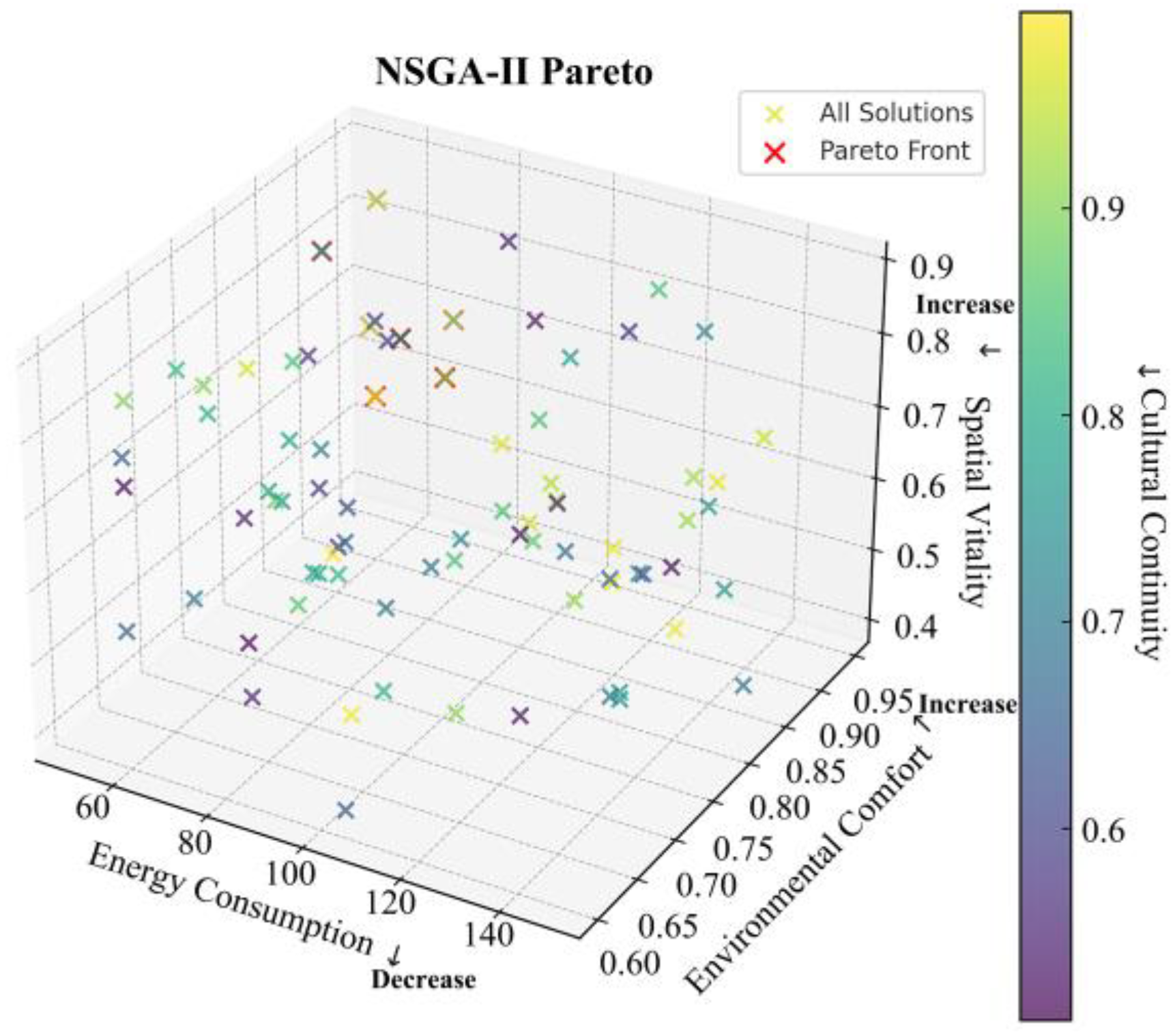

- In the field of decision support, Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) has been widely adopted to comprehensively evaluate indicators such as energy efficiency, thermal comfort, cultural value, and economic benefits. When combined with multi-objective optimization algorithms (e.g., NSGA-II) [33], MCDA enables the generation of Pareto-optimal solution sets for competing design objectives. Furthermore, machine learning (ML) and explainable AI (XAI) approaches are increasingly applied to extract environmental response patterns from large-scale monitoring data, accelerating parameter scanning and data-driven scheme selection [34]. The hybridization of CFD/microclimate simulations with ML models has also become a key trend for improving computational efficiency and predictive accuracy in environmental simulations.

2.4. Literature Review Summary and Research Positioning

- (1)

- The coupling mechanisms among building performance, environmental dynamics, and human behavior are still incomplete, limiting cross-scale model interaction.

- (2)

- Multi-objective decision models often lack the precision needed to balance energy saving, thermal comfort, cultural continuity, and spatial vitality.

- (3)

- Long-term data maintenance and feedback mechanisms of digital twins remain underdeveloped, hindering the continuous monitoring and dynamic evaluation of heritage spaces.

3. Materials and Methods

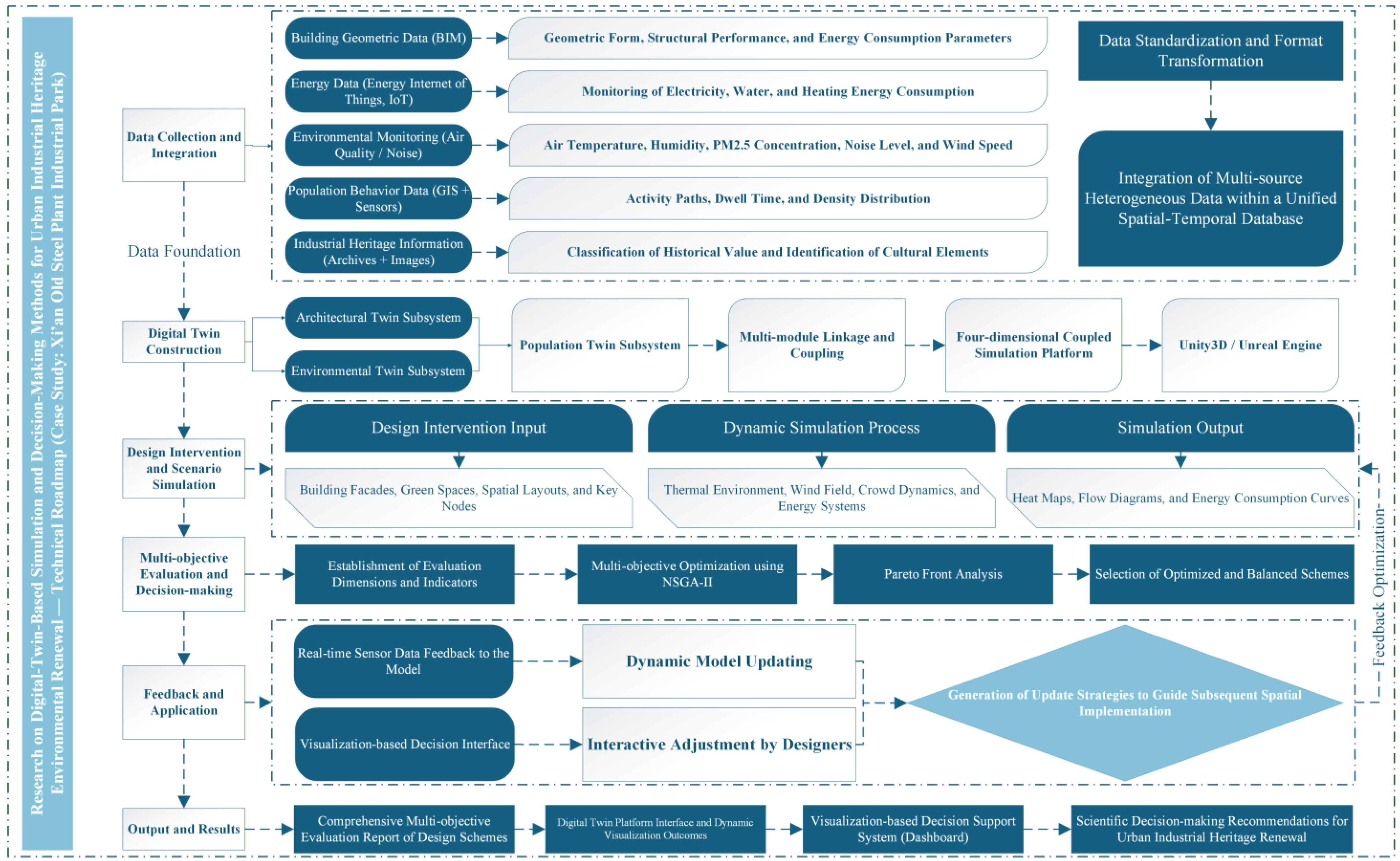

3.1. Research Framework and Technical Route

3.2. Data Collection and Integration

3.3. Construction of the Digital Twin

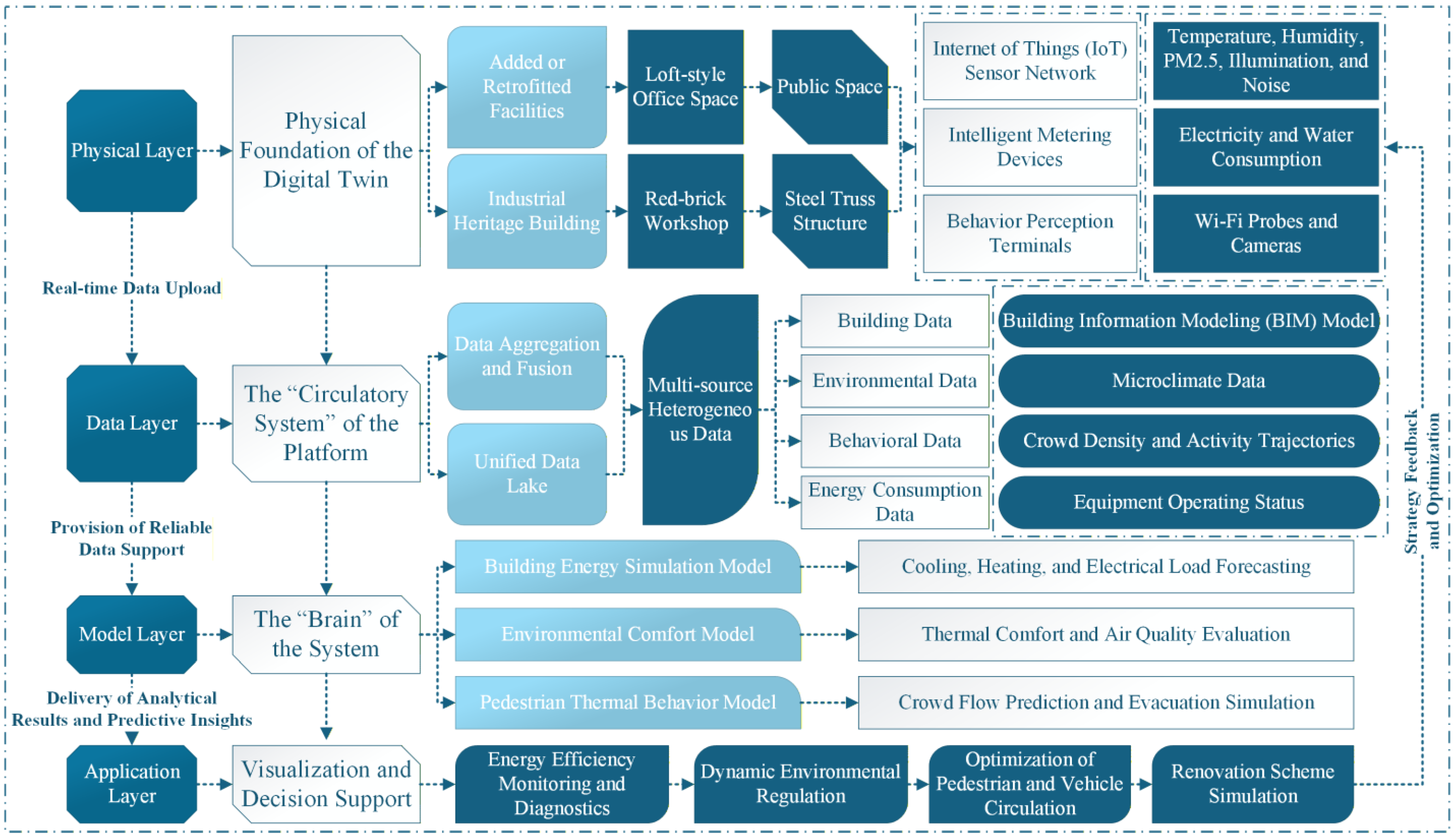

3.3.1. Platform Architecture Design

- (1)

- Building entities: Based on historical drawings, on-site surveys, and public mapping sources (e.g., OpenStreetMap), we developed parametric BIM models for 14 key industrial buildings in the park—such as the No. 1 and No. 2 rolling workshops—together with the newly added LOFT spaces. The models accurately reproduce characteristic features of industrial heritage, including long-span steel frames and red-brick facades.

- (2)

- Hypothetical sensor network: To construct a complete simulation loop, the study conceptually designs an Internet-of-Things (IoT) sensor network, in which virtual monitoring nodes are deployed across the site (Table 2).

- (1)

- Geometric Data: High-precision BIM models are developed based on historical architectural drawings and 3D laser scanning, containing detailed information on building structure, material properties, and spatial functions.

- (2)

- Environmental and energy data: Synchronizing the typical meteorological year data for Xi’an with conceptual sensor readings and simulated energy-consumption data to establish a unified spatiotemporal index.

- (3)

- Behavioral Data: Human flow density, spatial heatmaps, and behavioral trajectories within the park are dynamically identified through the integration of GIS-based spatial analysis and mobile signaling data.

- (4)

- Energy Consumption Data: Data from the IoT system capturing total building energy use and the operational status of key systems, such as HVAC and lighting equipment. All data undergo cleaning and standardization processes before being stored and managed within a unified data lake, which ensures a reliable and consistent data foundation for the upper-level modeling and simulation processes [41,42,43].

- (1)

- Building Energy Model (EnergyPlus V9.1.0): Using the building geometry and envelope material properties exported from the BIM model, together with TMY weather data, the model dynamically simulates hourly energy consumption and carbon emissions under alternative retrofit scenarios (e.g., enhanced insulation or window replacement) [44].

- (2)

- Microclimate Model (ENVI-metV5.0): Based on on-site vegetation patterns, ground-surface materials (e.g., high-absorption asphalt), and 3D building morphology, this model evaluates how design interventions—such as additional greenery or water features—affect outdoor thermal conditions, including UTCI, surface temperature, and wind fields [45].

- (3)

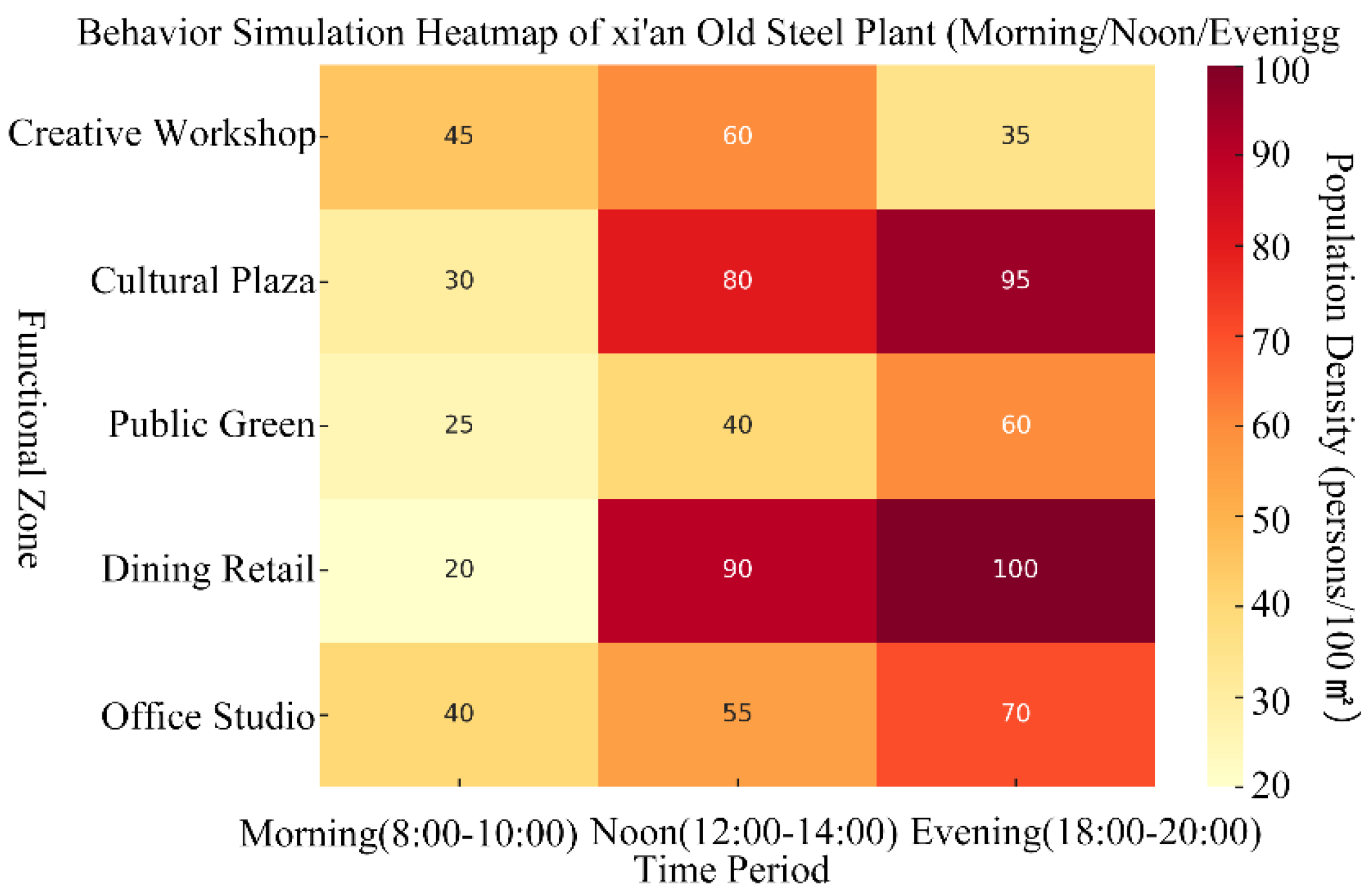

- Pedestrian Behaviour Model (AnyLogic V8.7): Three types of agents—visitors, employees, and residents—are defined, whose behavioral rules (route selection, dwelling decisions) are jointly driven by spatial accessibility, visual attraction, and environmental comfort (UTCI) derived from the ENVI-met model. The model predicts the intensity and spatial distribution of public-space use [46,47].

3.3.2. Real-Time Update and Feedback Mechanism

- (1)

- (2)

- Reverse Intelligent Decision Feedback: Simulation and analysis outputs from the model layer are processed through decision-making algorithms at the application layer to generate optimized control strategies or management recommendations, which are then transmitted back to the actuators in the physical layer. For instance, if the environmental comfort model predicts imminent thermal discomfort in a specific area, the system can automatically adjust the local HVAC settings [52].

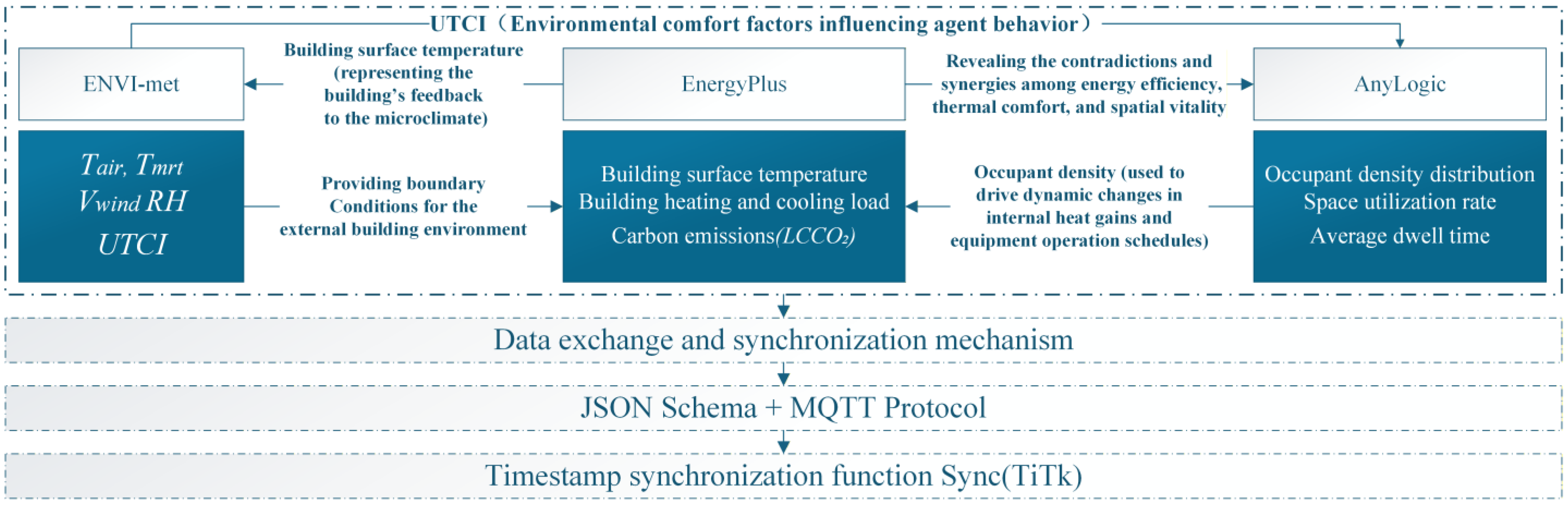

3.3.3. Model Coupling and Interfaces

- Coupling Mechanism A: From Outdoor Microclimate to Building Energy Use

- (1)

- ENVI-met outputs: After completing the typical-day simulation, ENVI-met produces hourly microclimatic variables, including air temperature, humidity, wind fields, and radiative heat fluxes.

- (2)

- Data transfer and mapping: After filtering and spatial aggregation through the parameter-mapping matrix , the processed results are converted via a JSON–MQTT interface into site-specific hourly weather files, which replace the typical meteorological year data as external boundary conditions for EnergyPlus.

- (3)

- EnergyPlus inputs: EnergyPlus performs energy simulations using this microclimate modified by buildings and vegetation, enabling the quantification of how interventions such as added greenery reduce cooling loads through local temperature mitigation.

- Coupling Mechanism B: From Environmental Variables to Human Behavior and Indoor Heat Gains

- (1)

- ENVI-met outputs: ENVI-met provides the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) as a key indicator of outdoor environmental comfort.

- (2)

- AnyLogic inputs and decision-making: The UTCI values are fed into the AnyLogic agent-based model as a core variable within the spatial choice probability function. Agents (pedestrians) tend to select and remain in areas with more favorable comfort conditions.

- (3)

- AnyLogic outputs: This rule-based simulation produces an hourly distribution of indoor occupancy across all buildings within the site.

- (4)

- EnergyPlus inputs: The dynamic occupancy profiles are converted into internal heat-gain schedules and incorporated into EnergyPlus as essential input parameters.

- (5)

- Closed-loop feedback: EnergyPlus recalculates energy consumption based on the updated internal loads. Changes in HVAC operation may further affect indoor conditions, forming—at more advanced levels of implementation—a complete feedback loop across the coupled models.

3.4. Design Interventions and Simulation Scenario Setup

3.4.1. Design Intervention Scenario Setup

- (1)

- Scenario A: Green Space Expansion and Microclimate Regulation—aims to reduce surface temperatures and improve thermal comfort through ground surface modification and increased vegetation coverage. The implementation in the model includes increasing the greening ratio G of the study unit (baseline +10%, +20%, +30%); replacing low-albedo pavements with high-albedo materials; introducing small-scale water features in plazas and streets. ENVI-met is used for three-dimensional microclimate simulation coupling surface–vegetation–radiation processes, outputting hourly fields. In the multi-agent model, environmental comfort (represented by UTCI) is mapped as part of the individual stay preference function to examine the secondary effects of microclimate improvements on crowd behavior [56,57,58].

- (2)

- Scenario B: Building Facade Renovation and Energy Efficiency Enhancement—aims to reduce building operational energy consumption and lifecycle carbon emissions. Key interventions include: increasing external wall insulation thickness, reducing window-to-wall ratio (WWR), introducing low-emissivity glazing and controllable shading devices, and installing rooftop BIPV (Building-Integrated Photovoltaics) systems [59,60,61].

- (3)

- Scenario C: Redesign of Public Activity Spaces and Optimization of Crowd Distribution—aims to enhance dwell time and spatial vitality through improved spatial connectivity and functional layout. Design interventions include: opening secondary factory buildings as atriums/activity spaces, adding pedestrian connectivity nodes, and introducing small-scale cultural activity nodes and nighttime lighting strategies. The AnyLogic/PedSIM multi-agent model is employed to simulate the travel-stay behavior of three groups (visitors, workers, and residents), with the behavioral utility function incorporating accessibility , visual attractiveness and environmental comfort [62,63].

3.4.2. Simulation Period and Dynamic Parameter Settings

- (1)

- Simulation Period and Simulation Dimensions:

- (2)

- Dynamic Parameter Settings (Table 5):

3.5. Multi-Objective Evaluation and Decision-Making Model

3.5.1. Indicator Definition, Quantification, and Standardization

- (1)

- Energy Efficiency (E): Assesses the performance of renovation schemes in reducing building and campus operational energy consumption and increasing renewable energy utilization, including annual energy consumption per unit area (kWh·m−2·a), renewable energy self-sufficiency (%), and carbon emissions per unit area (kgCO2·m−2·a) [64].

- (2)

- Environmental Comfort (C): Focuses on the impact of post-renovation outdoor physical environments on human thermal perception, including spatial averages or improvements of UTCI/PMV, daytime surface temperature (MST) variations, and heat island intensity reduction rate (HIRR) [65].

- (3)

- Pedestrian Activity (P): Evaluates the effect of renovation schemes on public space vitality, including space utilization density (D_t), average dwell time (T_avg), and spatial activity index (SAI) [66].

- (4)

- Cultural Adaptability (H): Quantifies the extent to which renovation schemes protect and transmit industrial heritage cultural values, including survey-based cultural identity scores, accessibility/visibility of heritage elements, and functional diversity [67].

3.5.2. Multi-Objective Optimization (NSGA-II) and Pareto Analysis

3.6. Simulation Data Sources and Uncertainty Considerations

4. Results-Case Study

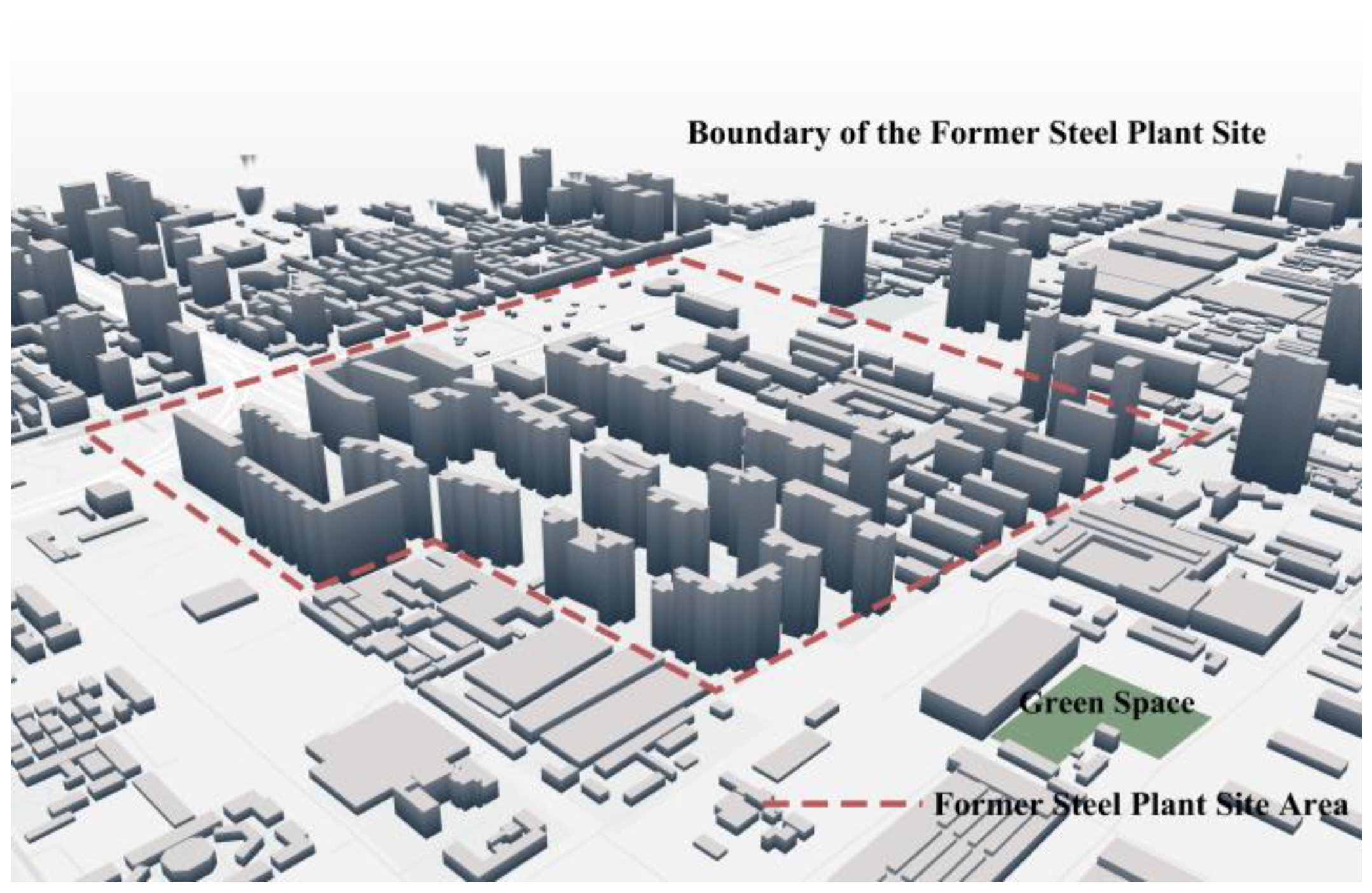

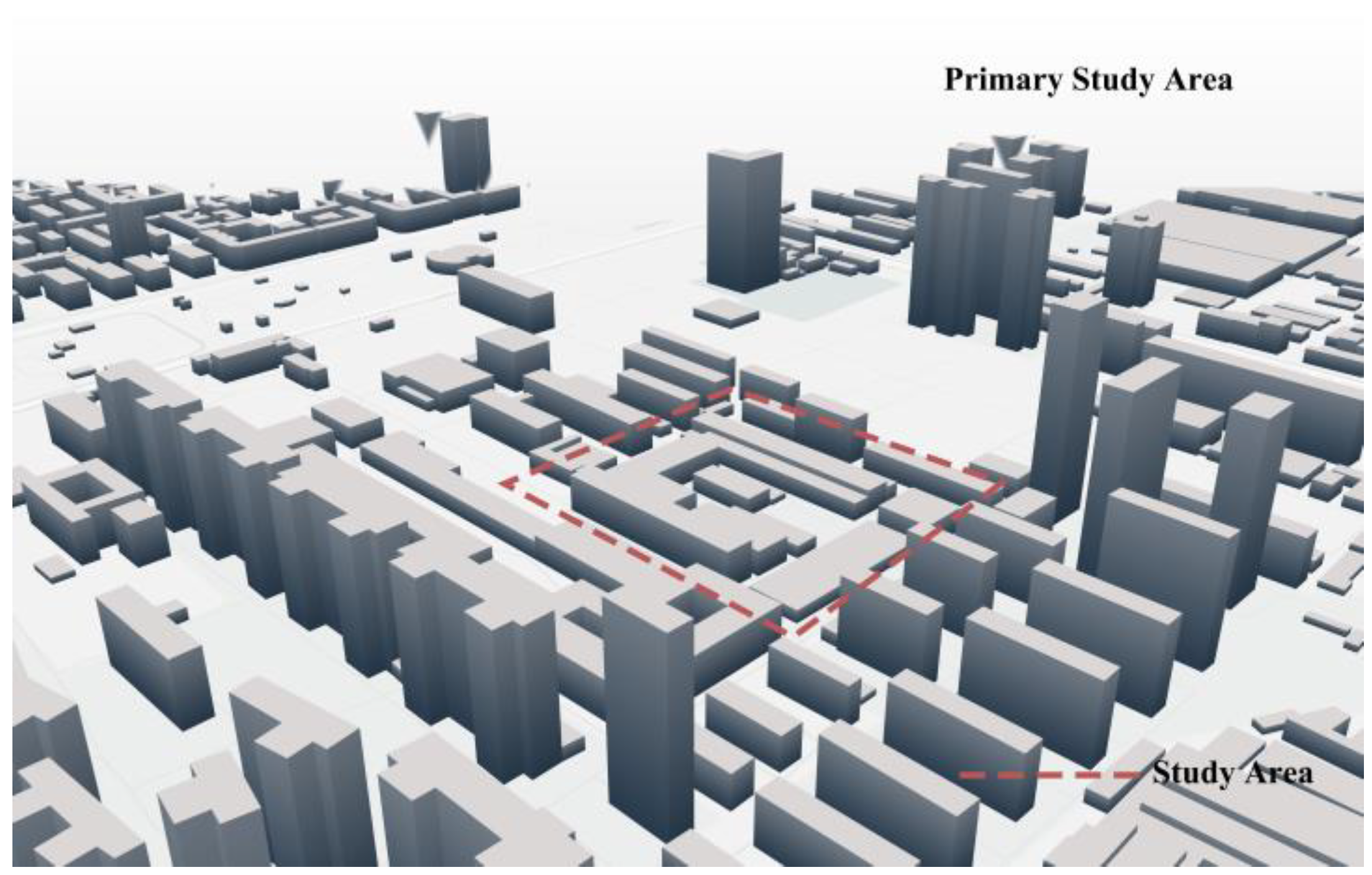

4.1. Regional Overview

4.1.1. Location Characteristics and Historical Evolution

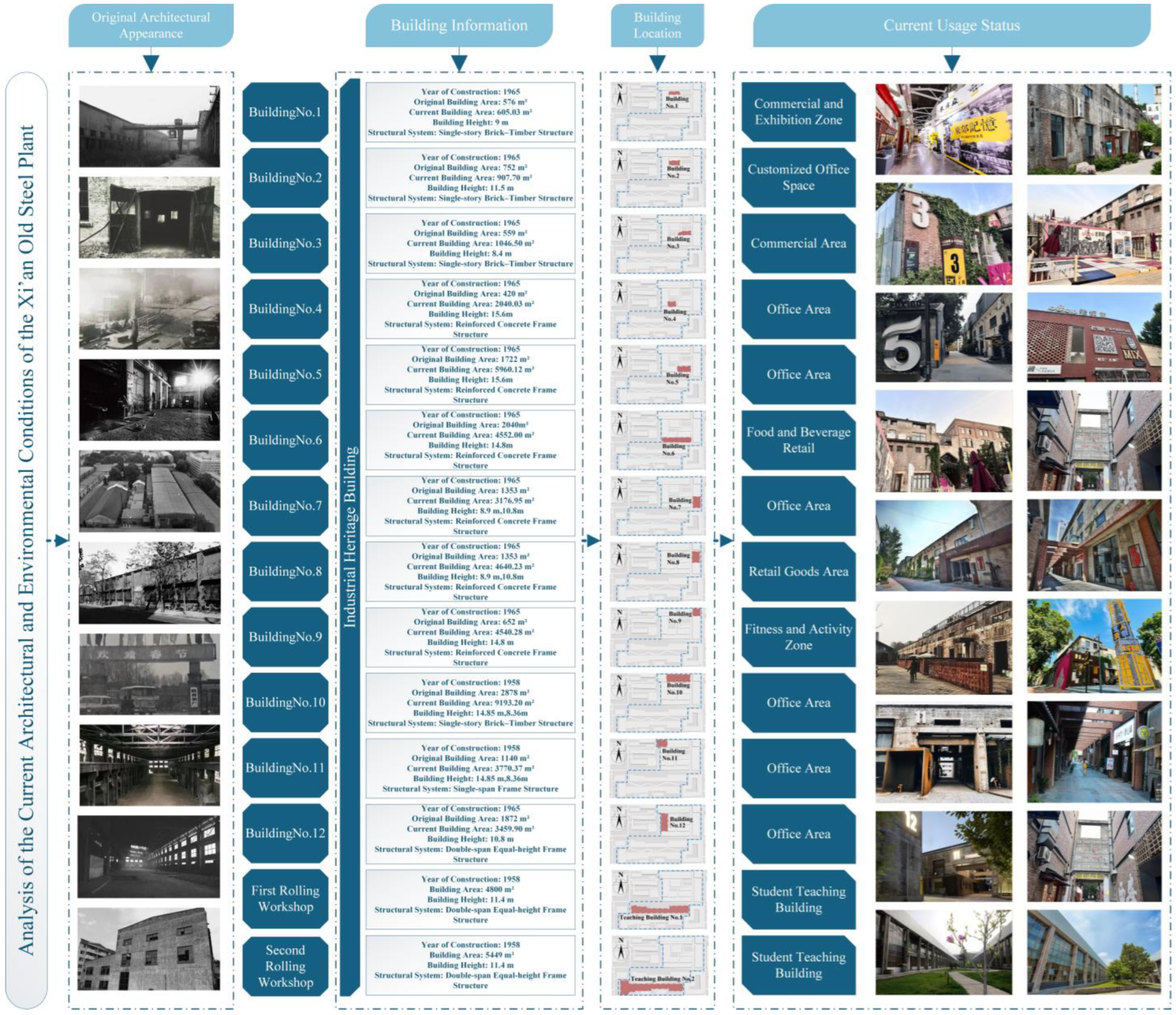

4.1.2. Current Spatial Structure and Functional Layout

4.1.3. Characteristics of Existing Buildings and Infrastructure

4.2. Digital Twin System Construction

4.2.1. Visualization of Data Acquisition and Model Construction Process

4.2.2. Coupled Simulation of Building and Environmental Modules

4.2.3. Real-Time Monitoring and Design Parameter Interaction

4.3. Design Intervention Simulation and Results Analysis

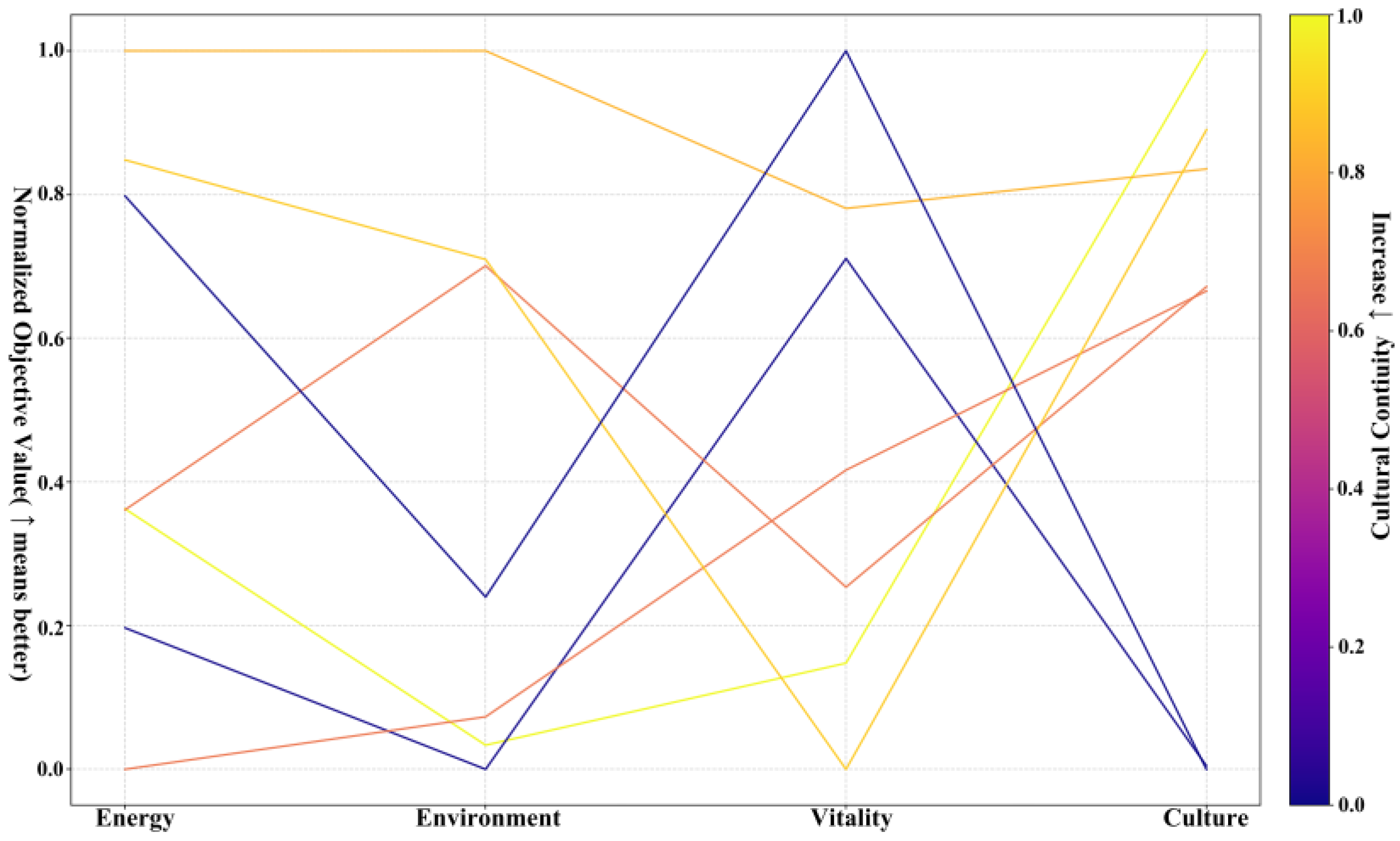

- (1)

- To integrate data of different dimensions, the min-max normalization method was adopted:

- (2)

- The Comprehensive Performance Index (CPI) is defined as follows:

- (1)

- Spatial foundation data: Urban topographic data (1:2000 scale maps) and satellite imagery (Landsat 8, 2023) released by the Xi’an Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning were combined with field surveys to reconstruct spatial structures and classify land use. Building morphology parameters were obtained from the Xi’an Industrial Heritage Register (2022), which documents the volumetric and height attributes of the Old Steel Plant workshops and ancillary structures.

- (2)

- Environmental and energy simulation data: Microclimatic parameters were derived from Typical Meteorological Year (TMY 2024) data provided by the Xi’an Meteorological Bureau and used in the ENVI-met model to simulate Heat Island Reduction Rate (HIRR) and changes in the Universal Thermal Climate Index (ΔUTCI). Building energy performance was modeled using EnergyPlus, calibrated against Building Energy Consumption Standards (GB/T 51161-2016) [86] and ASHRAE 90.1-2019, to calculate the annual variation rate of energy consumption (ΔE).

- (3)

- Behavioral and social data: Population density and spatial vitality data were obtained from multi-agent simulations conducted in AnyLogic, with model parameters informed by the Xi’an Urban Park Visitor Behavior Report (2021) and relevant academic literature (Nouri, A et al., Building Simulation, 2024) [12]. The Cultural Perception Index (CPI) was established using a weighted questionnaire-based evaluation system (α = 0.87), with weights determined through the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP).

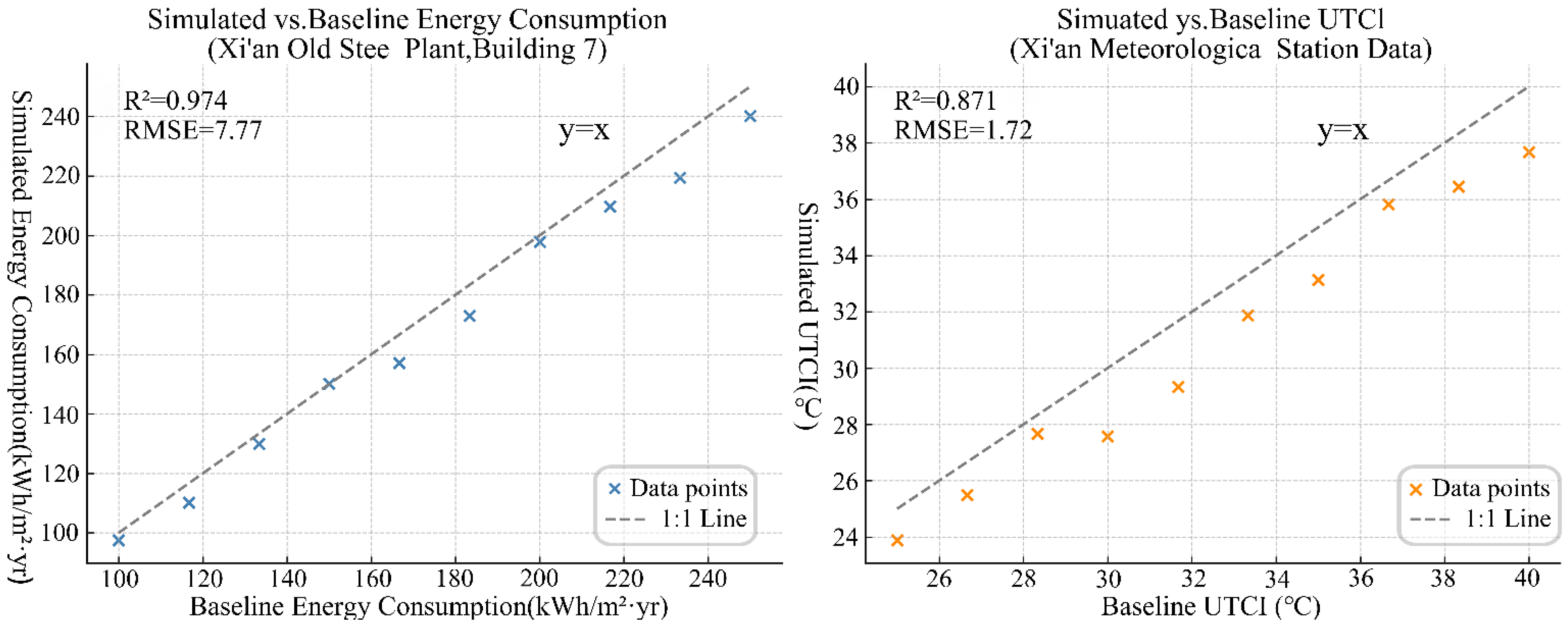

4.4. Model Sensitivity Analysis and Consistency Verification

- (1)

- Validation of Microclimate Simulation: In the microclimate module, ENVI-met was used to conduct a sensitivity analysis of the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI), surface temperature (Ts), and wind field (V). The main parameters—air temperature (Ta), surface albedo (α), and vegetation coverage (Vc)—were perturbed within ±10% to assess their influence on thermal comfort indicators. The results indicate that UTCI is most sensitive to air temperature variation (sensitivity coefficient Si = 0.62), followed by surface albedo (Si = 0.37), while wind speed has a relatively minor impact (Si = 0.21). This suggests that the thermal environment simulation is primarily governed by surface thermal properties and boundary climatic conditions, and the model’s physical consistency aligns well with theoretical expectations for urban heat environment modeling. Comparison with measured meteorological data (Xi’an Meteorological Bureau, July 2024) shows a root mean square error (RMSE) of 1.26 °C and a Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) of 0.91, indicating high consistency and predictive reliability of the microclimate model [89].

- (2)

- Validation of Building Energy Simulation: The building energy model, developed using EnergyPlus, incorporated envelope thermal parameters (U-value), equipment coefficient of performance (COP), and occupancy density (D) as key sensitivity variables to simulate variations in building energy consumption (E) and carbon emissions (LCCO2). Single- and multi-factor sensitivity analyses revealed that a 10% reduction in envelope heat transfer coefficient decreased total energy use by approximately 5.8%, a 10% improvement in equipment efficiency reduced carbon emissions by about 6.4%, while a 10% increase in occupancy density led to a 4.2% rise in energy consumption. Further linear regression analysis demonstrated a strong correlation between model predictions and the benchmark values defined in GB/T 51161-2016, with an R2 of 0.95 and a mean deviation within ±6%, confirming the stability and parameter consistency of the energy simulation model.

- (3)

- Validation of Spatial Vitality Simulation: The spatial vitality module employed an AnyLogic multi-agent simulation to validate behavioral dynamics, with walking speed (v), spatial attractiveness weight (W), and stay probability (P) as primary sensitivity parameters. By adjusting each within ±15%, the model evaluated responses in average dwell time (T), path coverage (C), and gathering index (GI). Results show that the model output is most sensitive to spatial attractiveness weight (Si = 0.68), suggesting that spatial configuration and node layout are the key factors influencing behavioral distribution. Field observation data (n = 312) were used for validation, yielding an RMSE of 0.18 and a correlation coefficient r = 0.89, confirming the model’s high accuracy and consistency in predicting spatial behavior patterns [90].

5. Discussion

5.1. Methodological Value and Generalizability

- (1)

- Modular architecture: The framework consists of relatively independent data, model, and application layers. The core simulation modules for industrial heritage—such as building performance, microclimate, and pedestrian dynamics (e.g., EnergyPlus, ENVI-met, AnyLogic)—and their coupling interfaces are universally applicable. When deployed in other industrial heritage sites (e.g., textile mills, port districts, or mining zones), only local geometric data, material properties, meteorological files, and behavioral parameters need to be updated, without modifying the underlying model-coupling logic or decision-analysis workflow.

- (2)

- Parameterization and adaptability: Key parameters—such as envelope thermal performance, greening strategies, and activity-node configuration—are defined in a parametric manner. This allows researchers to rapidly adapt the framework to projects in different climatic zones, scales, or heritage typologies by adjusting parameter sets, enabling differentiated evaluation of the “technological–ecological–cultural” co-benefits.

- (3)

- Transferability of the technical workflow: The integrated pipeline—from multi-source data fusion and cross-scale model coupling to multi-objective decision optimization—provides a replicable paradigm for addressing renewal challenges in diverse built environments, particularly complex heritage areas. Although the quantitative results in this study rely on simulation data from Xi’an, the methodology’s value in revealing systemic interactions, balancing multi-objective trade-offs, and supporting evidence-based design is broadly applicable.

5.2. Implications for the Sustainable Renewal of Industrial Heritage: Causal Chains Between Design Parameters and Performance Revealed by Coupled Simulation

- Improving environmental comfort: the synergy between surface reflectance and vegetative shading

- (1)

- Higher surface albedo: Replacing the original dark asphalt pavement (albedo ≈ 0.1) with light, high-reflectance materials (albedo ≥ 0.5) reduced absorbed shortwave radiation by ~40%. This led to notable decreases in surface temperature and mean radiant temperature (Tmrt), making it the primary contributor to UTCI improvement.

- (2)

- Geometric shading from vegetation: Newly introduced tree canopies blocked direct solar radiation by altering shading geometry. Simulations show that incident solar radiation on the human body decreased by 60–75% within shaded zones. The synergy between material reflectance (a material parameter) and canopy-coverage ratio (a spatial-form parameter) drives the improvement in thermal comfort.

- 2.

- Optimizing energy efficiency: directly linked to quantitative improvements in envelope thermal performance

- (1)

- Reduced wall U-value: Increasing insulation thickness to 80 mm reduced the wall U-value from 1.5 W/(m2·K) to 0.45 W/(m2·K). Sensitivity analysis indicates that this single parameter accounts for over 50% of the annual reduction in heating and cooling loads.

- (2)

- Improved window-to-wall ratio (WWR) and glazing properties: Reducing the WWR from 0.6 to 0.4 and applying low-SHGC Low-E glazing maintained daylighting while effectively limiting summer solar heat gain, contributing roughly 30% to the reduction in cooling loads.

- 3.

- Enhancing spatial vitality: Shaped jointly by environmental physical factors and functional spatial layout.

- (1)

- Environmental comfort as a behavioral driver: In the AnyLogic model, UTCI outputs from ENVI-met were incorporated into agents’ “stay-preference” functions. When UTCI improved from “strong heat stress” to “slight heat stress,” the probability of agents choosing the space increased by ~25%, indicating that microclimate interventions directly influence behavioral decision-making.

- (2)

- Spatial attraction of functional nodes: Newly added cultural installations and rest areas (functional parameters) create activity destinations. The combined effect—comfortable paths (determined by physical parameters) leading to attractive destinations (determined by functional parameters)—ultimately produces the observed high level of spatial vitality.

5.3. Theoretical Implications and Contributions to the Knowledge System of Industrial Heritage Regeneration

- (1)

- Methodological contribution: Establishing an operational technical paradigm for evidence-based design

- (2)

- Theoretical contribution: Advancing the understanding of the built environment as a complex system

- (3)

- Practical contribution: Reshaping the basis for collaborative governance and dialogue among diverse stakeholders.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

- (1)

- Deep integration with AI predictive models: Upon acquiring long-term in situ energy consumption and pedestrian flow data, more rigorous model calibration can be conducted using online updating techniques such as Kalman filtering or Bayesian updating, alongside uncertainty quantification, gradually replacing simulation-based inference with observation-driven empirical conclusions. Additionally, the integration of machine learning surrogate models within the framework can provide rapid approximations of high-fidelity physical simulations, significantly accelerating computation while maintaining acceptable accuracy, thereby enabling real-time generation and performance prediction of design alternatives [95].

- (2)

- Establishing a holographic IoT data infrastructure: Collaborating with site management to gradually deploy a comprehensive IoT sensor network can enable real-time data updating and long-term self-calibration of the digital twin. By embedding extensive sensors within future industrial heritage sites, environmental parameters (temperature, humidity, illumination, noise), building energy consumption, and crowd density can be continuously collected and automatically fed into the digital twin platform, enabling self-updating and calibration of the model and transforming it into a “living entity” that evolves synchronously with the physical environment [96,97].

- (3)

- Expanding immersive VR/AR interactions: Integrating digital twins with virtual and augmented reality technologies can create an immersive platform for public engagement. Stakeholders can “enter” visualized scenarios of proposed designs, experiencing them in a more intuitive and realistic manner, thereby providing deeper and more informed feedback, and elevating the level of public participation to a new standard [18,98].

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Deep integration with artificial intelligence: Incorporating machine-learning surrogate models to replace computationally intensive simulations will markedly improve computational efficiency, enabling near–real-time generation of design alternatives and performance predictions.

- (2)

- Enhancing participatory design: Integrating the digital-twin platform with VR/AR technologies will create immersive environments for public engagement, allowing non-expert stakeholders to intuitively experience and evaluate design alternatives. This will elevate collaborative governance to an unprecedented level.

- (3)

- In summary, this study goes beyond the scope of a single case and offers an integrated solution that combines methodological innovation, theoretical insight, and practical applicability for the sustainable regeneration of industrial heritage. It lays a solid foundation for establishing a more rigorous, scientific, and inclusive paradigm for future research and practice in this field.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

- (1)

- Observability: Priority is given to variables that can be obtained directly from field surveys, BIM/point-cloud data, or published statistical and meteorological datasets, or can be reasonably approximated from them.

- (2)

- Parameterizability: Each variable must have a clear definition, physical meaning, dimensions, and units, allowing consistent mapping across ENVI-met, EnergyPlus, and AnyLogic.

- (3)

- Calibratability: When field observations or industry/national standards are available, they are prioritized and used to calibrate model inputs. If assumptions are required, their influence ranges must be documented and reported through uncertainty or sensitivity analyses.

| Parameter Category | Variable | Unit | Physical Meaning | Data Source (On-Site/Literature/Model Default) | Calibration Method or Reference Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building Geometry | Building footprint and envelope (length × width × height) | m, m2 | Building mass and exterior surface area (influencing radiation and ventilation performance) | Historical drawings (on-site and archival), OpenStreetMap (as supplementary data), and satellite imagery (Google Earth Pro) were used, with volumetric verification based on the Xi’an Industrial Heritage Register. | Comparison with on-site survey drawings ensured a volumetric discrepancy within ±5% (2022–2024). |

| Floor height/Number of floors | m/floors | Determines indoor volume and volumetric heat capacity | |||

| Window-to-wall ratio (WWR) | % | Affects daylighting performance and heat gains | |||

| Material Properties | Envelope U-value | W·m−2·K−1 | Thermal transmittance (critical EnergyPlus input parameter) | Parameter values were assigned based on on-site measurements and the recommended ranges for similar existing industrial buildings specified in Chinese design standards. | According to the Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings (GB 50189-2015) [55], material properties were referenced to empirically measured ranges of comparable industrial buildings (e.g., U-value of red-brick walls ≈ 1.2–1.5 W/(m2·K)). |

| Thermal conductivity (k) | W·m−1·K−1 | Governs conductive heat transfer; used to derive U-values | |||

| Surface albedo | Dimensionless (0–1) | Surface or roof reflectance of incoming solar radiation | |||

| Surface emissivity (ε) | Dimensionless (0–1) | Governs longwave radiative heat exchange | |||

| Environmental Data | Air temperature (Ta) | °C | Meteorological boundary condition | Xi’an’s Typical Meteorological Year file from the China Standard Weather Database (CSWD), supplemented with hourly monitoring data from the Xi’an Meteorological Bureau for the summer of 2024. | Model inputs were validated against observed meteorological data for summer 2024, achieving an RMSE ≤ 1.5 °C. |

| Wind speed (V)/wind direction | m·s−1/direction | Influences microscale wind field and ventilation dynamics | |||

| Solar radiation (G) | W·m−2 | Incident shortwave solar radiation | |||

| Pedestrian Activity | Pedestrian density (D) | persons·m−2 | Intensity of space use (AnyLogic input/output variable) | For the AnyLogic multi-agent simulation, behavioral parameters were derived from the Xi’an Urban Park Visitor Behavior Report (2021). | The behavioral model was validated through on-site observations (n = 312), yielding a correlation coefficient of r = 0.89. |

| Average dwelling time (T_avg) | min | Influences energy use and comfort through lighting and ventilation demand | |||

| Behavioral choice coefficients (β1, β2, β3) | Dimensionless | Logit model regression coefficients (AnyLogic simulation) |

Appendix A.2

| Dimension | Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Microclimate Improvement | Heat Island Intensity Reduction Rate (HIRR) | |

| Thermal Comfort Enhancement | ΔUTCI | Average UTCI Change Before & After Simulation | |

| Energy | Energy Output | Renewable Energy Self-sufficiency Rate (RES) | |

| Energy Saving | ΔE | ||

| Energy Consumption | Energy Saving per Unit Area (ESD) | ||

| Carbon Emission Reduction | LCCO2 Reduction Rate | EnergyPlus Output | |

| Social | Space Utilization | Heritage Space Utilization Intensity (UHI) | |

| Dwell Time | ΔT_mean | Average Dwell Time Change | |

| Cultural Identity | C_index | Survey Mean Score |

References

- Jiang, Z.; Qi, Z.; Chen, L.; Xu, L.; Wan, D.; Burak-Gajewski, P.; Zawisza, R.; Liu, L. External Spatial Morphology of Creative Industries Parks in the Industrial Heritage Category Based on Spatial Syntax: Taking Tianjin as an Example. Buildings 2024, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Court, S.; Yang, L.; Wang, S.; Thirunavukarasu, A.; Zhao, Y. A Review of Digital Twin Technologies for Enhanced Sustainability in the Construction Industry. Buildings 2024, 14, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespedes-Cubides, A.S.; Jradi, M. A Review of Building Digital Twins to Improve Energy Efficiency in the Building Operational Stage. Energy Inf. 2024, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems; Kahlen, F.-J., Flumerfelt, S., Alves, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 85–113. ISBN 978-3-319-38754-3. [Google Scholar]

- Negri, E.; Fumagalli, L.; Macchi, M. A Review of the Roles of Digital Twin in CPS-Based Production Systems. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 11, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. Digital Twins in City Planning. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2024, 4, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lv, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sun, B.; Han, D. A Systematic Review of the Digital Twin Technology in Buildings, Landscape and Urban Environment from 2018 to 2024. Buildings 2024, 14, 3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruse, M.; Fleer, H. Simulating Surface–Plant–Air Interactions inside Urban Environments with a Three Dimensional Numerical Model. Environ. Model. Softw. 1998, 13, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, D.B.; Lawrie, L.K.; Winkelmann, F.C.; Buhl, W.F.; Huang, Y.J.; Pedersen, C.O.; Strand, R.K.; Liesen, R.J.; Fisher, D.E.; Witte, M.J.; et al. EnergyPlus: Creating a New-Generation Building Energy Simulation Program. Energy Build. 2001, 33, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoka, S. Evaluating the Impact of Urban Microclimate on Buildings’ Heating and Cooling Energy Demand Using a Co-Simulation Approach. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasandi, L.; Qian, Z.; Woo, W.L. Quantifying Urban Microclimate Feedback on Building Energy Use Using a Coupled Sim-ulation Workflow. Build. Environ. 2025, 285, 113657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, A.; Van Treeck, C.; Frisch, J. Sensitivity Assessment of Building Energy Performance Simulations Using MARS Meta-Modeling in Combination with Sobol’ Method. Energies 2024, 17, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Chau, H.-W.; Jamei, E.; Vrcelj, Z. Enablers and Challenges of Smart Heritage Implementation—The Case of Chinatown Melbourne. SASBE, 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, H.K.; Chan, H.W.E. Implementation Challenges to the Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings: Towards the Goals of Sustainable, Low Carbon Cities. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaie, F.; Remøy, H.; Gruis, V. Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings; a Systematic Literature Review of Success Factors. Habitat Int. 2023, 142, 102926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Li, Q.; Hu, X. Value Assessment for the Restoration of Industrial Relics Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process: A Case Study of Shaanxi Steel Factory in Xi’an, China. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 69129–69148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niccolucci, F.; Markhoff, B.; Theodoridou, M.; Felicetti, A.; Hermon, S. The Heritage Digital Twin: A Bicycle Made for Two. The Integration of Digital Methodologies into Cultural Heritage Research. Open Res. Eur. 2023, 3, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. Integrating Emerging Technologies with Digital Twins for Heritage Building Conservation: An Interdisciplinary Approach with Expert Insights and Bibliometric Analysis. Heritage 2024, 7, 6432–6479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Zhong, R.Y.; Jiang, Y. Digital Twin and Its Applications in the Construction Industry: A State-of-Art Systematic Review. Digit. Twin 2025, 2, 2501499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizzi, S. The Relevance of the Venice Charter Today. odk 2024, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douet, J. (Ed.) Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-42652-5. [Google Scholar]

- Baiani, S.; Altamura, P.; Turchetti, G.; Romano, G. Transizione energetica e circolare del patrimonio industriale. Il caso dell’ex SNIA a Roma | Energy and circular transition of the industrial heritage. The Ex SNIA case in Rome. Agathón 2024, 15, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrisano, M.; Bottero, M.; Cavana, G.; Fabbrocino, F.; Gravagnuolo, A.; Fusco Girard, L. Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Built Heritage: Towards the Implementation of the Circular City Model. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1561982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çeltekligil, A.; Arabacıoğlu, F.P. Adaptive Reuse in Industrial Heritage: A Bibliometric Review (2004–2024). In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference of Contemporary Affairs in Architecture and Urbanism, ICCAUA2025, Antalya, Turkey, 8–9 May 2025; Volume 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullen, P.A.; Love, P.E.D. Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings. Struct. Surv. 2011, 29, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, J. Conservation Values, the Authorised Heritage Discourse and the Conservation-Planning Assemblage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 709–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F.; Bosone, M.; Orabona, M. Multicriteria Evaluation Framework for Industrial Heritage Adaptive Reuse: The Role of the ‘Intrinsic Value’. Land 2024, 13, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Gu, K.; Zhang, X. Urban Conservation in China in an International Context: Retrospect and Prospects. Habitat Int. 2020, 95, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deren, L.; Wenbo, Y.; Zhenfeng, S. Smart City Based on Digital Twins. Comput. Urban Sci. 2021, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.-D.; Gu, B.-H.; Lam, H.-K.; Ok, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-H. Digital Twin Smart City: Integrating IFC and CityGML with Semantic Graph for Advanced 3D City Model Visualization. Sensors 2024, 24, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhu, J. CityGML in the Integration of BIM and the GIS: Challenges and Opportunities. Buildings 2023, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelou, T.; Gkeli, M.; Potsiou, C. Building Digital Twins for Smart Cities: A Case Study in Greece. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, X-4/W2-2022, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Multi-Objective Optimization Method for Building Energy-Efficient Design Based on Multi-Agent-Assisted NSGA-II. Energy Inf. 2024, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palley, B.; Poças Martins, J.; Bernardo, H.; Rossetti, R. Integrating Machine Learning and Digital Twins for Enhanced Smart Building Operation and Energy Management: A Systematic Review. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Academy of Building Research Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015; ISBN 1511211824.

- Meschini, S.; Pellegrini, L.; Locatelli, M.; Accardo, D.; Tagliabue, L.C.; Di Giuda, G.M.; Avena, M. Toward Cognitive Digital Twins Using a BIM-GIS Asset Management System for a Diffused University. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 959475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.-Y.; Li, J.-R.; Liang, Y.-J.; Wang, Q.-H.; Zhou, X.-F. Trochoidal Toolpath for the Pad-Polishing of Freeform Surfaces with Global Control of Material Removal Distribution. J. Manuf. Syst. 2019, 51, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, A.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital Twin in Industry: State-of-the-Art. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2019, 15, 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, K.-J.; Liu, S.-H. How Personality Traits and Professional Skepticism Affect Auditor Quality? A Quantitative Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ta, N.; Yu, B.; Wu, J. Are the Accessibility and Facility Environment of Parks Associated with Mental Health? A Comparative Analysis Based on Residential Areas and Workplaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 237, 104807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagini, C.; Bongini, A.; Marzi, L. From BIM to Digital Twin. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2024, 29, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, L.; Onstein, E.; Merschbrock, C. BIM and IoT Data Fusion: The Data Process Model Perspective. Autom. Constr. 2023, 149, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buuveibaatar, M.; Shin, S.; Lee, W. Digital Twin Framework for Road Infrastructure Management. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z. Prediction of Building Energy Consumption for Public Structures Utilizing BIM-DB and RF-LSTM. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 4631–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, E.; Gomes, J.; Conceição, M.I.; Conceição, M.; Lúcio, M.M.; Awbi, H. Modelling of Indoor Air Quality and Thermal Comfort in Passive Buildings Subjected to External Warm Climate Conditions. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaziyeva, D.; Stutz, P.; Wallentin, G.; Loidl, M. Large-Scale Agent-Based Simulation Model of Pedestrian Traffic Flows. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2023, 105, 102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, M.; Chang, Y.; Dang, Y.; Wang, K. Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction in Crowded Environments Using Social Attention Graph Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Chavez, S.A.; Eltamaly, A.M.; Garces, H.O.; Rojas, A.J.; Kim, Y.-C. Toward an Intelligent Campus: IoT Platform for Remote Monitoring and Control of Smart Buildings. Sensors 2022, 22, 9045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, Q. Virtual Reality in Historic Urban District Renovation for Enhancing Social and Environmental Sustainability: A Case of Tangzixiang in Anhui. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, P.; Berktold, M.; Müller, D. Real-Life Data-Driven Model Predictive Control for Building Energy Systems Comparing Different Machine Learning Models. Energy Build. 2024, 305, 113895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyyamozhi, M.; Murugesan, B.; Rajamanickam, N.; Shorfuzzaman, M.; Aboelmagd, Y. IoT—A Promising Solution to Energy Management in Smart Buildings: A Systematic Review, Applications, Barriers, and Future Scope. Buildings 2024, 14, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, S.; Li, G.; Shen, Q. Real-Time Monitoring and Optimization Methods for User-Side Energy Management Based on Edge Computing. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Luo, X.; Mortezazadeh, M.; Albettar, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhan, D.; Wang, L.; Hong, T. A Data Schema for Exchanging Information between Urban Building Energy Models and Urban Microclimate Models in Coupled Simulations. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2025, 18, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadhor, A.; Alsubai, S.; Kryvinska, N.; Ghazouani, N.; Bouallegue, B.; Al Hejaili, A.; Sampedro, G.A. A Synergistic Approach Using Digital Twins and Statistical Machine Learning for Intelligent Residential Energy Modelling. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial Group of the “Energy Efficiency Design Standards for Public Buildings” Implementation Guide for Energy Efficiency Design Standards for Public Buildings; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015; ISBN 978-7-112-18451-4.

- Guerri, G.; Crisci, A.; Morabito, M. Urban Microclimate Simulations Based on GIS Data to Mitigate Thermal Hot-Spots: Tree Design Scenarios in an Industrial Area of Florence. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Tan, Y. Cooling Effects and Energy-Saving Potential of Urban Vegetation in Cold-Climate Cities: A Comparative Study Using Regression and Coupled Simulation Models. Urban Clim. 2025, 59, 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zhou, B. Optimizing Vegetation Configurations for Seasonal Thermal Comfort in Campus Courtyards: An ENVI-Met Study in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Climates. Plants 2025, 14, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvalai, G.; Zhao, F. Active Prefabricated Façade with Building-Integrated Photovoltaic (APF-BIPV) Technologies for High Energy Efficient Building Renovation: A Systematic Review of Recent Research Advancements. Energy Build. 2025, 348, 116440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasbi, F.; Khdair, A.I.; Aburumman, G.A.; Tahmasebi, M.; Thi, N.H.; Afrand, M. Energy-Efficient Building Façades: A Comprehensive Review of Innovative Technologies and Sustainable Strategies. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 99, 111643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, P.M. Sustainable Insulation Technologies for Low-Carbon Buildings: From Past to Present. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, H. Microscopic Simulation-Based Pedestrian Distribution Service Network in Urban Rail Station. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 9, 100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, C.; Radu, V.; Gheorghe, R.; Tăbîrcă, A.-I.; Ștefan, M.-C.; Manea, L. Crowd Panic Behavior Simulation Using Multi-Agent Modeling. Electronics 2024, 13, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, F.S.; Sa’di, B.; Safa-Gamal, M.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Alrifaey, M.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Stojcevski, A.; Horan, B.; Mekhilef, S. Energy Efficiency in Sustainable Buildings: A Systematic Review with Taxonomy, Challenges, Motivations, Methodological Aspects, Recommendations, and Pathways for Future Research. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 45, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, N.; Tang, F. Outdoor Thermal Comfort Research and Its Implications for Landscape Architecture: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Cui, J.; Sun, J.; Guo, W. Research on Pedestrian Vitality Optimization in Creative Industrial Park Streets Based on Spatial Accessibility: A Case Study of Qingdao Textile Valley. Buildings 2025, 15, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Angrisano, M.; Bosone, M.; Buglione, F.; De Toro, P.; Fusco Girard, L. Participatory Evaluation of Cultural Heritage Adaptive Reuse Interventions in the Circular Economy Perspective: A Case Study of Historic Buildings in Salerno (Italy). J. Urban Manag. 2024, 13, 107–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, S.; Kumar, A.; Ram, M.; Klochkov, Y.; Sharma, H.K. Consistency Indices in Analytic Hierarchy Process: A Review. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frish, S.; Talmor, I.; Hadar, O.; Shoshany, M.; Shapira, A. Enhancing Consistency of AHP-Based Expert Judgements: A New Approach and Its Implementation in an Interactive Tool. MethodsX 2025, 14, 103341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea-Salim, C.; Flores-Larsen, S.; Hongn, M.; Gonzalez, S. A Framework for Multi-Objective Optimization in Energy Retrofit of Heritage Museums: Enhancing Preservation, Comfort, and Conservation Conditions. Heritage 2024, 7, 7210–7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, R.; Bai, Y.; Wang, J.; Deng, G. Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm-II: A Multi-Objective Optimization Method for Building Renovations with Half-Life Cycle and Economic Costs. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, W.; Dimitrijević, B. Analytic Hierarchy Process-Based Industrial Heritage Value Evaluation Method and Reuse Research in Shaanxi Province—A Case Study of Shaanxi Steel Factory. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Wang, J. A Study on the Impact of Cultural Inheritance and Innovative Practices on Tourist Behavior in Industrial Heritage-Themed Districts: A Case Study of Xi’an. Buildings 2025, 15, 2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Feng, Q.; Wu, M.; Xi, S.; Zhang, P. HIDT: A Digital Twin Modeling Approach through Hierarchical Integration for Industrial Internet. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 181, 109306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Ahmad, R.; Li, D.; Ma, Y.; Hui, J. Industrial Applications of Digital Twins: A Systematic Investigation Based on Bibliometric Analysis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Aihemaiti, M.; Abudureheman, B.; Tao, H. High-Precision Optimization of BIM-3D GIS Models for Digital Twins: A Case Study of Santun River Basin. Sensors 2025, 25, 4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, S.U.; Kim, I.; Hwang, K.-E. Advancing BIM and Game Engine Integration in the AEC Industry: Innovations, Challenges, and Future Directions. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2025, 12, 26–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, J.; Wooley, A.; Harris, G. Verification and Validation of Digital Twins: A Systematic Literature Review for Manufacturing Applications. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 63, 342–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirbod, O.; Choi, D.; Schueller, J.K. From Simulation to Field Validation: A Digital Twin-Driven Sim2real Transfer Approach for Strawberry Fruit Detection and Sizing. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wilde, P. Building Performance Simulation in the Brave New World of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins: A Systematic Review. Energy Build. 2023, 292, 113171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoka, S.; Tsikaloudaki, K.; Theodosiou, T. Coupling a Building Energy Simulation Tool with a Microclimate Model to Assess the Impact of Cool Pavements on the Building’s Energy Performance Application in a Dense Residential Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barahouei Pasandi, H.; Moradbeikie, A.; Barros, D.; Verde, D.; Paiva, S.; Lopes, S.I. Improving BLE Fingerprint Radio Maps: A Method Based on Fuzzy Clustering and Weighted Interpolation. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Enhanced Network Techniques and Technologies for the Industrial IoT to Cloud Continuum, New York, NY, USA, 10 September 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, S.; Yan, S.; Chau, H.-W.; Jamei, E.; Vrcelj, Z. From Data to Cultural Response: A Machine Learning–Driven Digital Twin Model for Smart Heritage Precincts in Urban Context. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2025, 30, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Caceres, A.; Hunger, F.; Forssén, J.; Somanath, S.; Mark, A.; Naserentin, V.; Bohlin, J.; Logg, A.; Wästberg, B.; Komisarczyk, D.; et al. Towards Digital Twinning for Multi-Domain Simulation Workflows in Urban Design: A Case Study in Gothenburg. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2025, 18, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Rios, A.; Petrou, M.L.; Ramirez, R.; Plevris, V.; Nogal, M. Industry 5.0, towards an Enhanced Built Cultural Heritage Conservation Practice. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Hong, T.; Li, C.; Zhang, Q.; An, J.; Hu, S. A Thorough Assessment of China’s Standard for Energy Consumption of Buildings. Energy Build. 2017, 143, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roka, R.; Figueiredo, A.; Vieira, A.; Cardoso, C. A Systematic Review of Sensitivity Analysis in Building Energy Modeling: Key Factors Influencing Building Thermal Energy Performance. Energies 2025, 18, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eingrüber, N.; Korres, W.; Löhnert, U.; Schneider, K. Investigation of the ENVI-Met Model Sensitivity to Different Wind Direction Forcing Data in a Heterogeneous Urban Environment. Adv. Sci. Res. 2023, 20, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Daii, S.; Liu, C.; Niu, S.; Xia, L.; Xiao, L.; Ikeda, Y. A Study on Roaming Behaviour of Crowd in Public Space with the Analysis in Computer Vision and Agent-Based Simulation. In Proceedings of the 55th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association, Perth, Australia, 1–2 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, T.W.; Mo, Y. A Comprehensive Digital Twin Framework for Building Environment Monitoring with Emphasis on Real-Time Data Connectivity and Predictability. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 17, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosamo, H.; Mazzetto, S. Integrating Knowledge Graphs and Digital Twins for Heritage Building Conservation. Buildings 2024, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Calderon, C.; Ford, A.; Robson, C.; Jin, J. Digital Twin for Resilience and Sustainability Assessment of Port Facility. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2025, 15, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E. Digital Twins for the Automation of the Heritage Construction Sector. Autom. Constr. 2023, 156, 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moufid, O.; Praharaj, S.; Jarar Oulidi, H.; Momayiz, K. A Digital Twin Platform for the Cocreation of Urban Regeneration Projects. A Case Study Morocco. Habitat Int. 2025, 161, 103427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eneyew, D.D.; Capretz, M.A.M.; Bitsuamlak, G.T. Continuous Model Calibration Framework for Smart-Building Digital Twin: A Generative Model-Based Approach. Appl. Energy 2024, 375, 124080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Ji, W. Development and Application of a Digital Twin Model for Net Zero Energy Building Operation and Maintenance Utilizing BIM-IoT Integration. Energy Build. 2025, 328, 115170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, G.; Agostinelli, S.; Muzi, F. Smart Buildings and Digital Twin to Monitoring the Efficiency and Wellness of Working Environments: A Case Study on IoT Integration and Data-Driven Management. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoban, V.; Yantaç, A.E. Expert Insights into XR and Urban Digital Twins: Shaping Future Phygital Cultural Experiences. In Proceedings of the EKSIG 2025: Data as Experiential Knowledge and Embodied Processes, Budapest, Hungary, 12–13 May 2025; Design Research Society: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Data Type | Content | Reference for Parameterization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building Geometry Data | Includes structural form, material properties, and spatial function information | Typical Parameters Obtained from Field Survey | Public Data https://zygh.xa.gov.cn/ywpd/cxghgsgb/ghglpqgs/3.html (accessed on 23 October 2025). http://www.lgccyy.com/Admission/outfit/office/index.html (accessed on 25 October 2025) |

| Environmental Monitoring Data | Real-time parameters such as air quality, noise, and temperature–humidity | Public Data http://sn.cma.gov.cn/ (accessed on 20 October 2025) https://www.worldweatheronline.com/xian-weather-averages/shaanxi/cn.aspx (accessed on 23 October 2025) | |

| Population Activity Data | Enables dynamic recognition of pedestrian density and behavioral trajectories | Public Data https://www.xa.gov.cn/, (accessed on 25 October 2025) http://www.lgccyy.com/Admission/outfit/office/index.html (accessed on 25 October 2025) | |

| Energy Data | Monitors building energy consumption and equipment operation status | Public Data https://www.xincheng.gov.cn/zwgk/zfbmml/qzfgzbm/xasxcqtjj/1.html (accessed on 25 October 2025) https://tjj.xa.gov.cn/index.html(accessed on 20 October 2025) https://swj.xa.gov.cn/zyyw/zyhj/1.html (accessed on 23 October 2025) | |

| Dimension | Primary Scope |

|---|---|

| Microclimate | Temperature–humidity sensors, anemometers, and solar radiation sensors are virtually deployed in major plazas, streets, and building perimeters. |

| Energy use | Smart meters are assigned to the main electrical distribution boards to simulate the acquisition of whole-building energy consumption. |

| Human activity | Wi-Fi probes are conceptually placed at primary entrances and activity nodes to simulate the monitoring of crowd density and movement trajectories. |

| Model | Main Inputs | Main Outputs | Coupled Targets | Calibration Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENVI-met | Meteorological Boundary Conditions, Building Form | Air Temperature, Humidity, Wind Speed, UTCI | EnergyPlus, AnyLogic | Xi’an Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) Data |

| EnergyPlus | Building Material Parameters, Meteorological Data | Energy Consumption, Carbon Emissions | ENVI-met | GB 50189-2015 [55] |

| AnyLogic | Spatial Comfort, Accessibility | Pedestrian Density, Dwell Time | ENVI-met | Behavioral Survey Report |

| Temperature | Level |

|---|---|

| 46 °C | Extreme Heat Stress |

| 38–46 °C | Very Strong Heat Stress |

| 32–38 °C | Strong Heat Stress |

| 26–32 °C | Moderate to Slight Heat Stress |

| 9–26 °C | No Heat Stress/Neutral |

| Parameter Category | Specific Settings | Data Source | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meteorological Boundary Conditions | Typical Meteorological Year (TMY): Xi’an TMY Data Representative Summer Day: July 27 Daily Maximum Temperature: 35.2 °C Average Wind Speed: 1.8 m/s Predominant Wind Direction: South Weather Conditions: Clear sky, no precipitation | China Standard Meteorological Database; Xi’an Meteorological Bureau | Simulation covers a full 24 h period to comprehensively evaluate the performance of design interventions under extreme heat conditions. | |

| Occupant Activity Patterns | Workers | Active period: Weekdays (Monday–Friday) 09:00–18:00. Behavioral rules: follow fixed activity patterns based on office locations. | Campus operation data; survey questionnaires | Higher base visitation rates and longer average stochastic dwell times are set for weekends to simulate varying usage intensities. |

| Visitors, Tourists | Active period: full day; weekends (Saturday–Sunday) with higher intensity. Behavioral rules: arrival time, dwell duration, and activity choice (touring, consumption) follow probability distributions derived from field surveys. | |||

| Building Operation Schedule | Cooling system: operating schedules and setpoint temperatures are defined according to the “Code for Energy Efficiency Design of Public Buildings” and actual campus operation. Lighting system: on/off schedules and energy intensity are set based on the “Code for Energy Efficiency Design of Public Buildings,” natural daylight availability, and actual campus operation. | “Code for Energy Efficiency Design of Public Buildings” (GB 50189-2015) [55]; campus property management records | Operational schedules differentiate weekdays and weekends to reflect building energy usage patterns. | |

| n | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI | 0 | 0 | 0.58 | 0.90 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.32 |

| Parameter Category | Key Parameter Examples | Data Source and Generation Method | Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building Geometry | Form, Dimensions, Floor Height | 3D modeling based on OpenStreetMap and satellite imagery, with volumetric verification against the “Xi’an Industrial Heritage Inventory” | Reconstructed from publicly available maps; no on-site precision survey conducted |

| Material Properties | Envelope Thermal Transmittance (U-value) | Assigned based on recommended value ranges for similar existing buildings from the “Code for Energy Efficiency Design of Public Buildings” (GB 50189-2015) [55] | Based on limited observations, historical documentation, and literature; source materials are not publicly accessible |

| Environmental Data | Air Temperature, Humidity, Wind Speed | Typical year data for Xi’an station from the China Standard Meteorological Year (TMY) database | Based on Xi’an meteorological data; environmental conditions are inherently variable |

| Pedestrian Activity | Visitation Rate, Dwell Time | Set according to probability distributions of behavioral patterns derived from limited on-site observations and studies of similar cultural and creative parks | Based on limited observations and literature; behavioral patterns involve assumptions |

| Time Period | Key Events and Development Stages |

|---|---|

| 1958 | Plant established and named “Shaanxi Steel Plant” (abbreviated as “Shaan Steel”) |

| 1964–1965 | Relocated to Xi’an in 1964. In 1965, a workshop moved from Dalian Steel Plant was reorganized and put into production |

| 1960s–1980s | Became one of China’s eight major special steel enterprises. Produced over 100 types of specialty steels, including high-speed tool steel, and some military products |

| 1988–1998 | In 1988, the plant ceased production for transformation. By 1998, faced with debt and other challenges, it confronted a shutdown and restructuring |

| 2002 | Officially declared bankrupt and acquired by Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology Science & Education Industry Group |

| 2012 | Under the promotion of Xin Cheng District government, initiated the positioning and development of the “Old Steel Plant Design and Creative Industry Park” |

| 2013–2016 | Redevelopment project commenced, with the park officially opening in 2016 |

| From 2016 to the present | Currently houses approximately 150 enterprises with an annual output exceeding 1 billion RMB, becoming a landmark for urban innovation and a model for industrial heritage redevelopment in Xi’an |

| Dimension | Key Features |

|---|---|

| Building Renovation Strategy | The core principles are “restoration to original” and “micro-renovation.” The main structures, red brick façades, and industrial facilities of nine Soviet-style workshops are preserved, while functionality is enhanced through added skylights and the integration of modern materials such as glass curtain walls and steel structures. |

| Spatial Function Transformation | Single-purpose industrial spaces are converted into mixed-use industrial parks combining creative offices, cultural exhibitions, and commercial leisure. Notable examples include converting pickling pools into ecological water features, workshop tracks into art corridors, and assembling discarded components into large-scale installation artworks. |

| Structure and Materials | The large-span spatial characteristics of the original industrial buildings are fully utilized. Lofts are added internally to increase usable area while retaining brick walls, industrial slogans, and other era-specific details. |

| Landscape and Ecological Environment | Renovation emphasizes preserving the original ecological environment, including retaining many native trees. Industrial heritage elements are creatively reused, such as converting pickling pools into water features and repurposing old materials for planters, creating a distinctive industrial landscape. |

| Cultural and Social Benefits | The site has become a cultural landmark and a model for industrial tourism. Institutions such as the “Cheng dong Impression” Experience Hall and Xi’an Urban Memory Museum preserve and communicate the industrial history and urban memory. |

| Category | Technical Parameters | Data and Accuracy (Simulated Values) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) | Number of scan stations: 400; point cloud density: ~1000 pts/m2; range accuracy: ±10 mm | Generated point cloud: ~3.8 × 109 points; mean registration error: 0.015 m | Simulated high-precision ground geometry acquisition for building and terrain model reconstruction |

| UAV Oblique Photogrammetry | Flight altitude: 120 m; forward overlap: 80%; side overlap: 70%; resolution: 2.5 cm/pixel | Simulated generation of orthophotos and DSM; planimetric error: 0.035 m; elevation error: 0.045 m | Simulated acquisition of macro-scale spatial data and roof geometry capture |

| Ground-Based Photogrammetry | Shooting distance: 20 m; focal length: 24 mm | Simulated façade images; spatial error < 3 cm | Provides building façade texture and structural detail data |

| Point Cloud Preprocessing and Feature Extraction | Noise removal threshold: σ = 3σ_mean; feature extraction rate: 92% | Output simplified point cloud: ~48 GB | Forms a high-quality spatial dataset for model reconstruction |

| BIM Data Integration | Includes 14 main factory buildings; total building area ~68,000 m2 | 120 metadata fields (structural type, materials, construction year, function, etc.) | Simulated construction of Digital Information Model (DIM) |

| Visualization Platform Integration | Data linkage frequency: 1 Hz; real-time rendering frame rate ≥ 30 FPS | 3D model accuracy (simulated): ≤0.05 m | Supports multi-scale visualization and interactive presentation |

| Model Accuracy Verification | Ground Control Points (GCPs): 25 | Planimetric error: 0.035 m; elevation error: 0.043 m | Simulated geometric accuracy verification results |

| Scenario | Retrofit Strategy | ΔT (°C) | Δ Energy Consumption (%) | Δ Illuminance (%) | PMV | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Baseline (original roof structure, no greening) | - | - | - | +0.4 | High heat load, low comfort |

| B | Optimized skylight + diffused glass | −2.8 | −8.7 | +35 | −0.2 | Balanced light and heat |

| C | B + Roof greening | −4.5 | −15.3 | +33 | −0.3 | Optimal thermal condition |

| D | C + Natural ventilation optimization | −4.2 | −14.8 | +31 | −0.3 | Best overall performance |

| Area | Heat Island Intensity Reduction Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| A | 18.5 |

| B | 14.2 |

| C | 20.1 |

| D | 12.4 |

| E | 17.8 |

| Area | ||

|---|---|---|

| A | 18.5 | 0.79 |

| B | 14.2 | 0.23 |

| C | 20.1 | 1.00 |

| D | 12.4 | 0.00 |

| E | 17.8 | 0.70 |

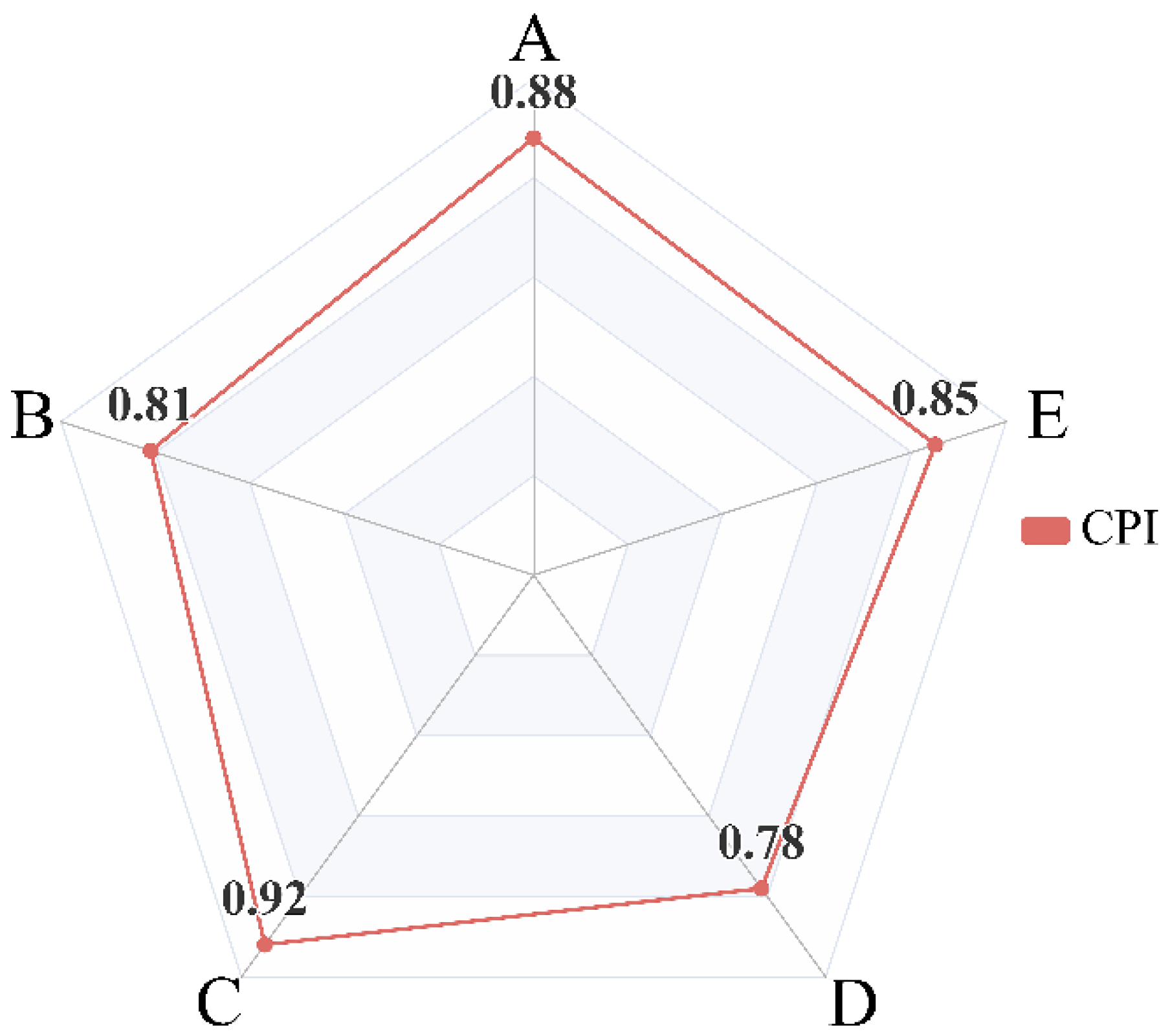

| Area | HIRR (%) | ΔE (kWh/m2·a) Annually | ΔUTCI (°C) | Increase in Crowd Density (%) | CPI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 12.5 | 18.6 | −1.8 | 25.4 | 0.88 |

| B | 10.3 | 15.2 | −1.5 | 18.2 | 0.81 |

| C | 14.1 | 19.8 | −2.0 | 31.7 | 0.92 |

| D | 9.8 | 13.5 | −1.3 | 15.6 | 0.78 |

| E | 16.4 | 12.1 | −2.4 | 12.2 | 0.85 |

| Data Type | Primary Sources of Calibration Reference Data |

|---|---|

| Environmental Data | Hourly meteorological observations (temperature, humidity, and wind speed) for July 2024 were obtained from the Xi’an Meteorological Bureau. These data were used to calibrate the ENVI-met microclimate model. |

| Energy Consumption Data | Monthly electricity billing records for 2024 were collected from a representative office building within the Old Steel Plant Industrial Park (floor area ≈ 4200 m2). These records served as the baseline for calibrating the annual load curve of the EnergyPlus energy model. |

| Behavioral Data | Manual pedestrian counts were conducted at three major plazas within the park across six sessions (three weekdays and three weekends), yielding a total of 312 valid sample points. These data were used to calibrate population density parameters in the AnyLogic multi-agent simulation model. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, W. Digital Twin–Based Simulation and Decision-Making Framework for the Renewal Design of Urban Industrial Heritage Buildings and Environments: A Case Study of the Xi’an Old Steel Plant Industrial Park. Buildings 2025, 15, 4367. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234367

Zhao Y, Li K, Zhang W. Digital Twin–Based Simulation and Decision-Making Framework for the Renewal Design of Urban Industrial Heritage Buildings and Environments: A Case Study of the Xi’an Old Steel Plant Industrial Park. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4367. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234367

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yian, Kangxing Li, and Weiping Zhang. 2025. "Digital Twin–Based Simulation and Decision-Making Framework for the Renewal Design of Urban Industrial Heritage Buildings and Environments: A Case Study of the Xi’an Old Steel Plant Industrial Park" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4367. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234367

APA StyleZhao, Y., Li, K., & Zhang, W. (2025). Digital Twin–Based Simulation and Decision-Making Framework for the Renewal Design of Urban Industrial Heritage Buildings and Environments: A Case Study of the Xi’an Old Steel Plant Industrial Park. Buildings, 15(23), 4367. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234367