1. Introduction

With the rapid expansion of urban rail transit, new metro lines increasingly intersect with existing underground structures, such as pile foundations, diaphragm walls, and station facilities. In earlier projects, concrete was typically removed manually via vertical shafts or other auxiliary equipment, which substantially increased construction costs and duration. In recent years, however, it has become more common to allow the shield machine to directly cut through existing concrete structures. During this cutting process, the stress redistribution in the surrounding strata can induce uncertain deformations in adjacent structures. Faced with these engineering challenges, it is crucial to enhance the adaptability and resilience of the system under construction-induced disturbances [

1,

2,

3]. In practice, optimizing excavation and tunneling parameters is essential to minimize the impact of cutting loads on existing structures [

4].

Previous studies on structural deformation induced by shield machine cutting have mainly focused on the mechanical behavior of concrete pile foundations. Xu et al. [

5] systematically analyzed the load-transfer behavior of a pile–raft foundation system in the Quyang Road-Liyang Road section of Shanghai Metro Line 10, revealing the impact mechanism of pile-cutting construction on the superstructure. Yuan et al. [

6] investigated the mechanical response of the Guangji bridge piles during shield cutting for Suzhou Metro Line 2, demonstrating that the thrust and torque generated by the cutterhead significantly influence pier deformation. Yao [

7] examined the structural responses of reinforced concrete piles in silty strata during cutting by EPB shield machine on the Tel Aviv Metro Red Line project in Israel, integrating laboratory tests, numerical simulations, and field monitoring. Wang et al. [

8] evaluated the feasibility of a shield cutting-through method for the project, in which a shield tunnel crosses the Fengqi Bridge of Hangzhou Metro Line 2. The results show that the deformation induced by the upward line is greater than that of the downward line.

In contrast to concrete piles, the mechanical response of diaphragm walls to shield machine cutting has received relatively limited attention. Wu et al. [

9] developed a numerical model to investigate the cutting mechanism, in which the joints between adjacent diaphragm wall panels were modeled as hinges and the surrounding soil as spring elements. Their study clarified the deformation patterns and internal force variations of the diaphragm wall during cutting. Furthermore, Zhuang et al. [

10] conducted laboratory tests and numerical simulations to investigate the interaction among diaphragm walls, surrounding soil, and the main structure under seismic loading, thereby elucidating the coupled soil–structure–wall behavior.

Despite these efforts, comprehensive studies on the structural response induced by shield machine cutting through diaphragm walls remain scarce. In this study, a refined numerical model of an existing metro station is established based on a shield crossing project of Suzhou Metro Line 8 to evaluate the mechanical response of the station structure during cutting through diaphragm walls. The model is used to reveal the deformation characteristics of existing metro stations under different tunneling parameters. The findings provide practical guidance for optimizing tunneling parameters and controlling the deformation of existing metro stations.

2. Project Description

2.1. Project Overview

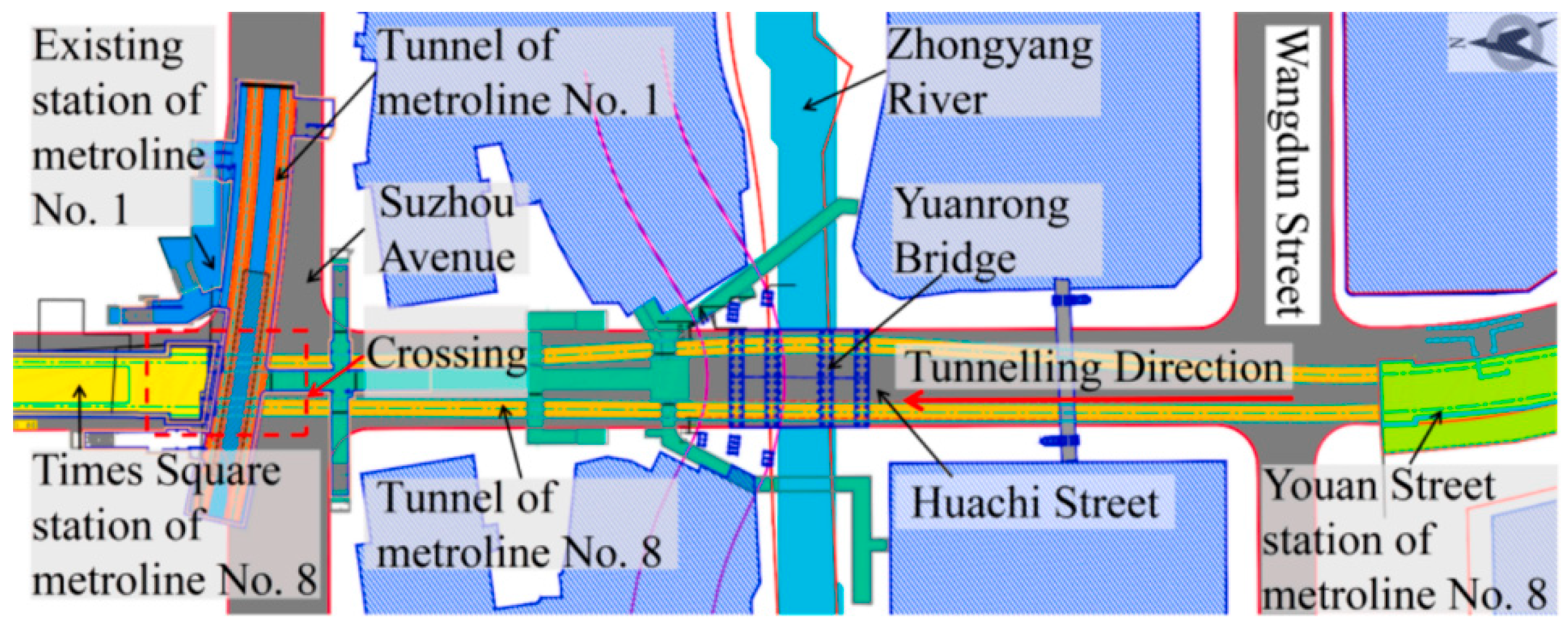

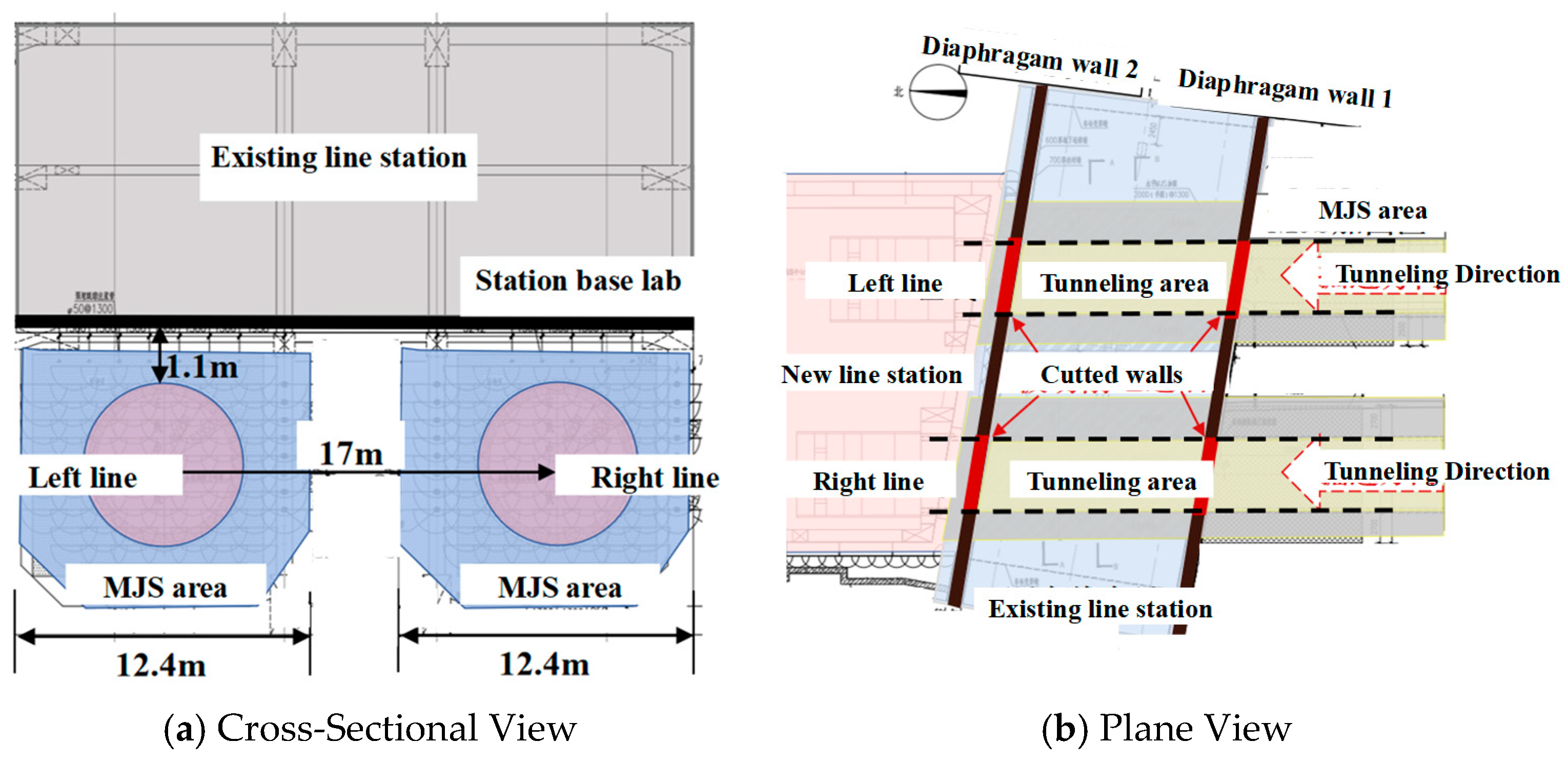

Figure 1 shows the layout of Suzhou Metro Line 8, where the new shield tunnels closely cut through the existing Line 1 section between Time Square Station and Youan Street Station. The total length of the shield tunneling section is 471.3 m on the left line and 474.2 m on the right line. The tunnel axis spacing between the two lines is approximately 17 m. To minimize the construction impact on the existing station, horizontal MJS (Metro Jet System) reinforcement is applied beneath the station base slab. The reinforced zone measures approximately 19.3 m in length and 12.4 m in width.

Figure 2 shows the cross-sectional and plan views of this tunnel section as it passes beneath the existing station.

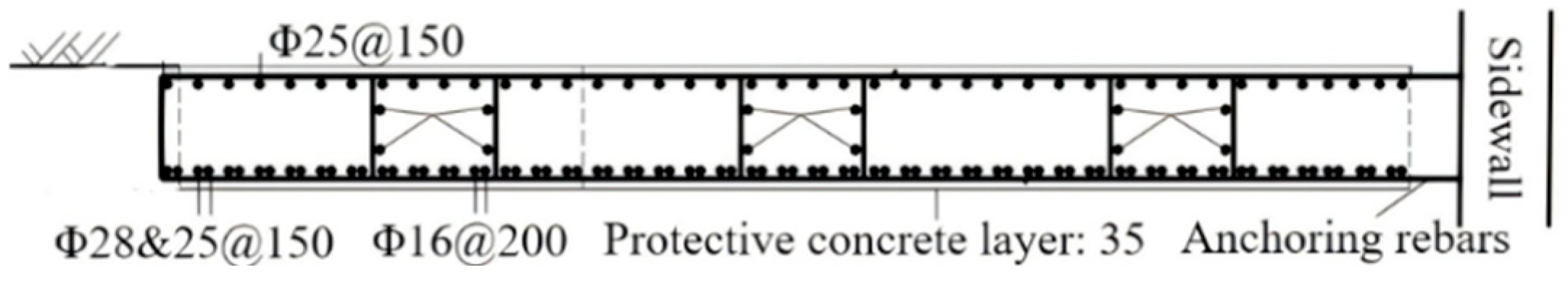

The existing reinforced concrete diaphragm wall is a composite wall structure with a thickness of 600 mm. The concrete compressive strength is C30 (

fc′ = 30 MPa), and its cover thickness is 35 mm. Flexible connections (circular steel locking pipes with a diameter of 550 mm and a thickness of 20 mm) are employed between adjacent diaphragm walls. The reinforcement details for the diaphragm wall are shown in

Figure 3. The outer reinforcement consists of 25 mm diameter bars spaced at 150 mm centers, and the inner reinforcement comprises a combination of 25 mm diameter bars at 150 mm centers and 28 mm diameter bars at 150 mm centers. The steel bars are grade HRB335, with a yield strength of 335 MPa and an ultimate tensile strength of 490 MPa.

2.2. Monitoring Scheme

At the concourse level of existing Line 1 station, vertical displacement of track bed and horizontal displacement of side wall structures are monitored at 10 cross-sections for both the up (S) and down (X) lines, with measurements conducted once daily. Monitoring is performed using a Leica TM50 total station, with angular accuracy of ±0.5″ and distance accuracy of ±0.6 mm +1 ppm. Daily surveys cover 10 cross-sections along the Line 1 station walls and track beds at 6–12 m intervals. Monitoring points were installed in the station concourse and automated measurements were acquired at each section. The layout of monitoring points is illustrated in

Figure 4.

3. Numerical Modeling

3.1. Computational Model

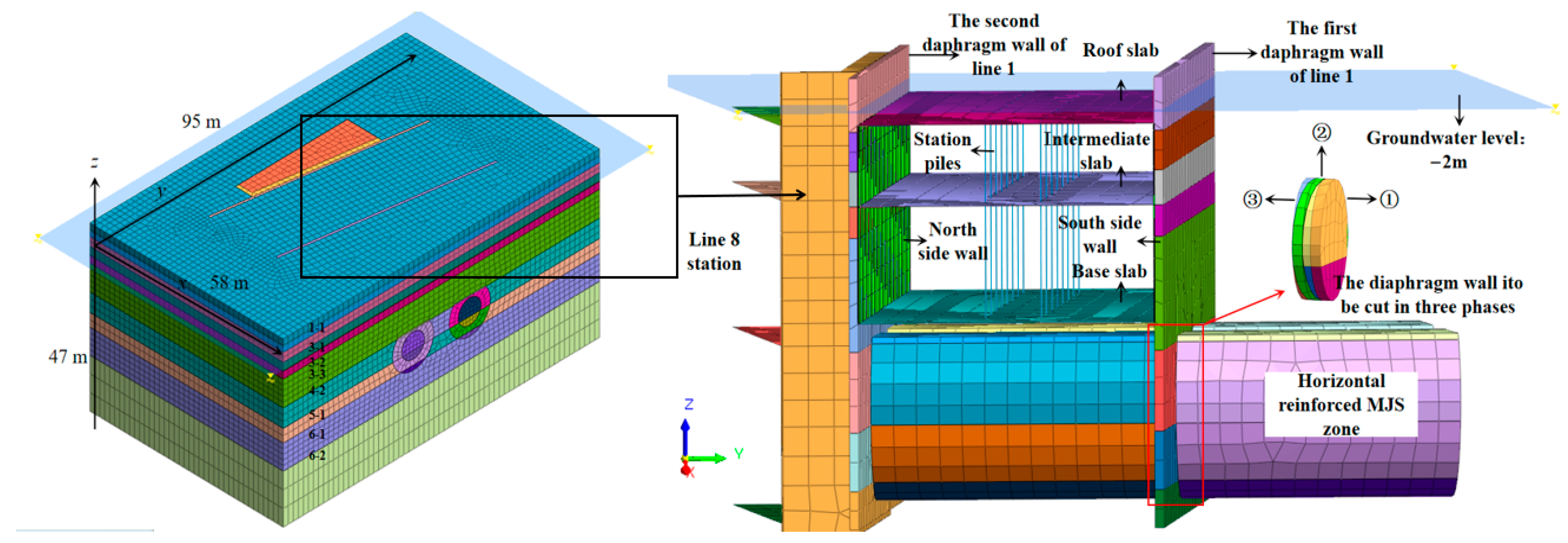

A refined three-dimensional (3D) model is established using Midas/GTS NX, with dimensions of 95 m × 58 m × 47 m (see

Figure 5). The groundwater table is set at 2 m below the ground surface (z = −2 m). The modeled structures include the two diaphragm walls, the two side walls of the existing Line 1 station, the base slab, intermediate slab and roof slab of the station, the receiving shaft of Line 8, and the horizontally reinforced MJS zone. The horizontally reinforced MJS zone is explicitly modeled with its actual geometry and material properties. This element is often neglected in conventional models, but is critical for reducing structural deformation. For the boundary conditions, transverse movement at the vertical plane is constrained, whole displacements and rotations at the model bottom are fully fixed, and the top surface is set free [

11].

An intersection angle of 19° between the shield tunnel and the diaphragm wall is explicitly simulated by dividing the cutting process into three stages (see

Figure 5①–③), allowing more realistic capture of the structural deformation response. The soil-structure interface is modeled with contact elements characterized by a normal stiffness of 20 GPa/m, a tangential stiffness of 20 GPa/m, cohesion of 20 kPa, and a friction angle of 18° [

12]. The methodology of element birth and death is applied to simulate the metro station and the shield tunnel [

13].

To optimize computational resources while focusing on the global deformation response induced by cutting loads, the diaphragm wall is idealized as a continuous elastic solid element with C30 concrete properties in the numerical model. Compared to prior studies, the proposed model addresses two key limitations of conventional models: (1) Incorporating the geometric shape and material property of horizontally reinforced MJS zone, which is frequently ignored but critical for reducing structural deformations [

14,

15,

16]. (2) Establishing a detailed model of the existing station and independent diaphragm walls, considering the frictional effect between soils and structures [

1].

Figure 6 shows the relative positions between the twin tunnels and the main structure. The depth of diaphragm wall is 28.5 m, and the vertical distance from the ground surface to the station base slab is 15.5 m. The shield tunnel excavation radius is 4.3 m. The thickness of MJS reinforcement zone is 2.9 m, and the longitudinal distance between the station base slab and the excavation tunnel is 2.3 m. According to the geological survey, eight soil layers are considered in the modeling process, with detailed parameters summarized in

Table 1. The modified Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion is applied for describing the constitutive behavior of all soils in this study [

17,

18,

19].

In this study, the structural elements are adopted as linear elastic materials [

20], detailed structural properties are listed in

Table 2.

The finite element analysis consists of 68 calculation steps, with a convergence tolerance of ε < 1 × 10−3. The average CPU time is about 8.5 min per step, and the total computation time is approximately 800 min.

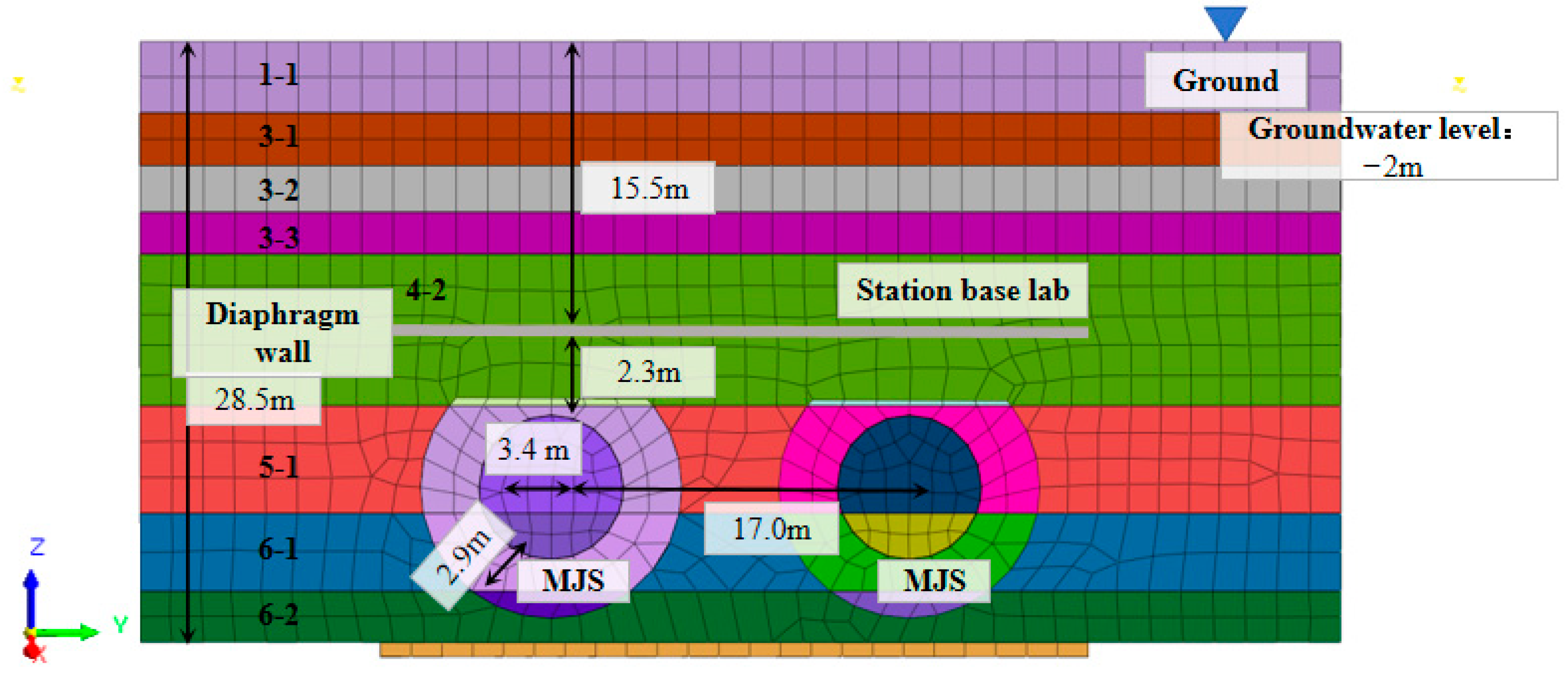

3.2. Modeling Procedure

This study focuses on the deformation response of the existing station induced by shield machine cutting through the diaphragm walls. The simulation process consists of three stages:

(1) All elements and boundary conditions are activated, the groundwater level is assigned, and the initial geo-stress field is calculated to reach equilibrium [

8,

21,

22]. Upon completion, the computed displacements are reset to zero to define the reference configuration [

23].

(2) Soil excavation in the station area is simulated, the station structural elements are activated, and the corresponding material properties are assigned and updated as required [

24].

(3) Simulation of the cutting process in three stages: (a) left-line tunneling through the first diaphragm wall, with segment erection and simultaneous grouting; (b) repetition of the process for the second diaphragm wall until breakthrough of the left line; and (c) subsequent shield tunneling of the right line until completion (see

Figure 7).

Load parameters are equivalent tunnel face support pressure and moment generated by the measured thrust and torque of shield machine, and then applying equivalent thrust/torque loads on the structure to simulate the actual cutting process [

25]. The thrust and torque are idealized as uniformly distributed loads acting on the diaphragm wall within the cutting region [

26]. The loading area of shield machine cutterhead is 36 m

2, with thrust and torque values set at 150 kN/m

2 and 300 kN·m, respectively. The grouting layer is modeled as a homogeneous elastic equivalent material [

27,

28,

29]. After each ring of obstruction is cut, the corresponding grouting material is immediately activated in the model. The grouting pressure is set to 0.4 bar. The load configurations for shield cutting are illustrated in

Figure 8.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Model Validation

This section compares the measured vertical displacements of the track bed and the lateral deformations of station side walls with the corresponding numerical simulation results, and validates the reliability and predictive capability of the established numerical model.

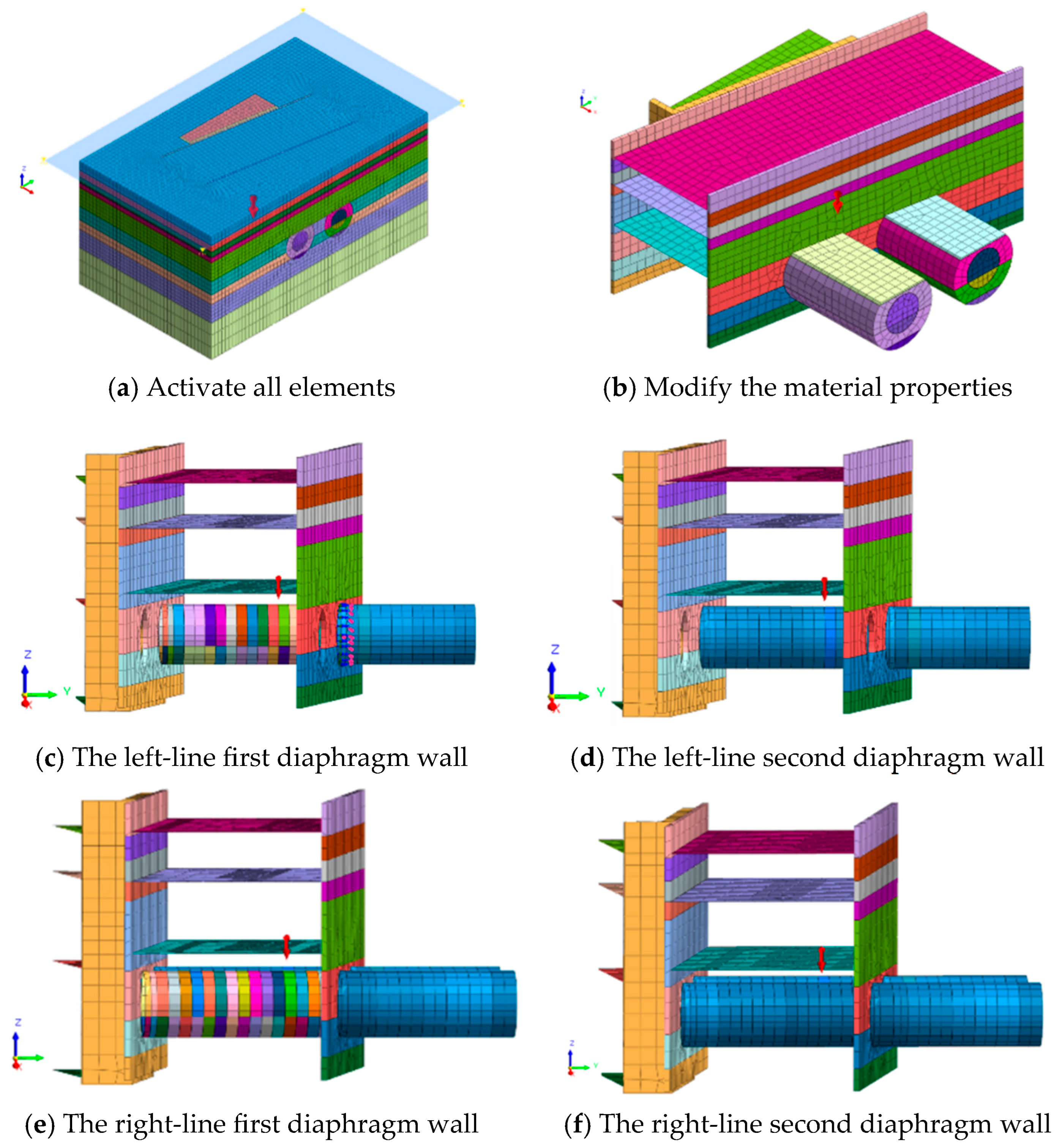

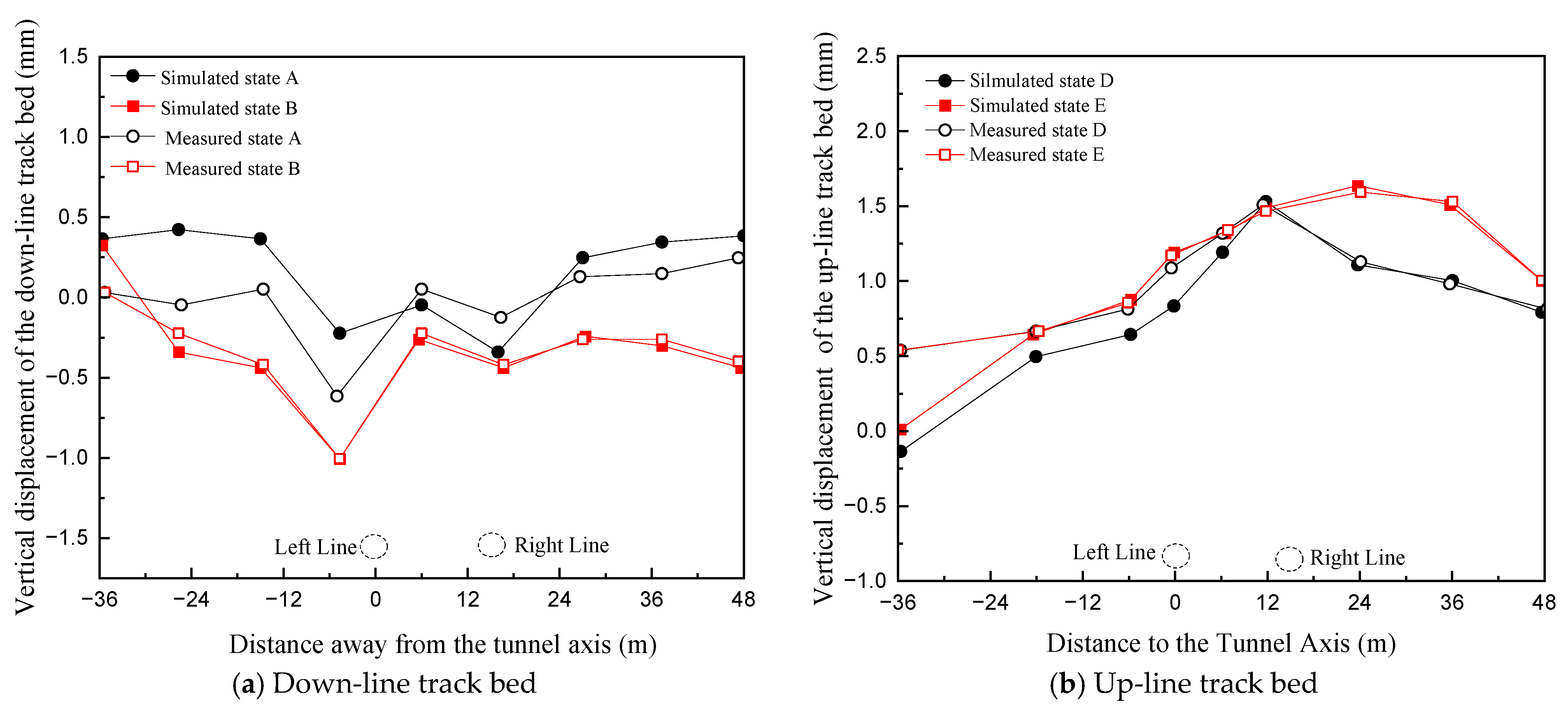

4.1.1. Track Bed Vertical Displacement

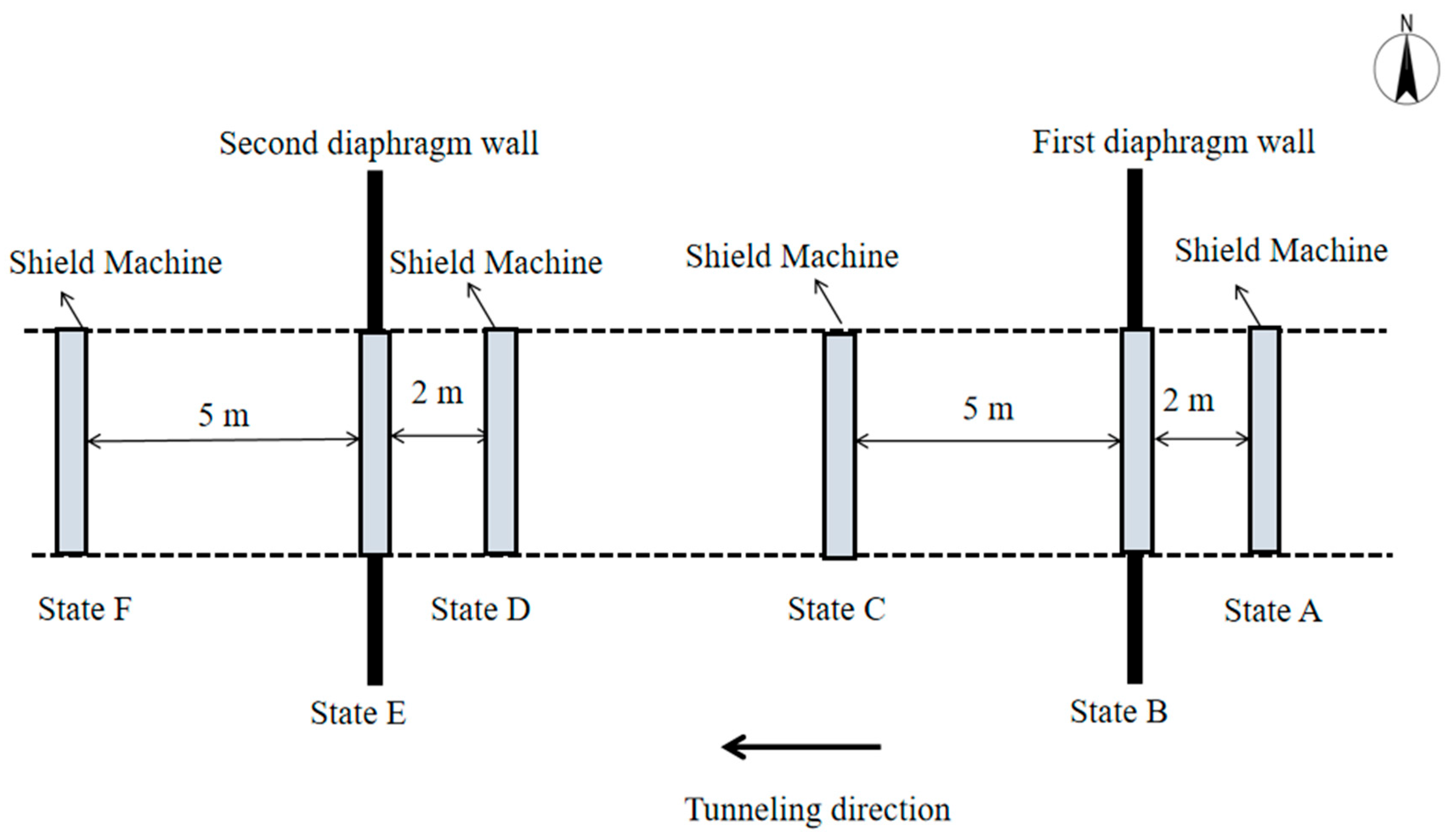

As the structural deformation induced by left tunnel lines are similar to that of right tunnel lines, and the left line is constructed prior to the right line, the model validation mainly focuses on the left-line crossing two diaphragm walls. To comprehensively characterize the vertical displacement behavior of the track bed during the cutting process, six representative shield positions (States A–F) are defined, as schematically illustrated in

Figure 9:

(1) States A–C (first diaphragm wall): State A: Cutterhead positioned 2 m prior to the first wall; State B: Cutting the first wall; State C: Advance of 5 m beyond the first wall.

(2) States D–F (second diaphragm wall): State D: Cutterhead positioned 2 m prior to the second wall; State E: Cutting the second wall; State F: Advance of 5 m beyond the second wall.

Figure 9.

Position of shield machine.

Figure 9.

Position of shield machine.

Table 3 presents the correspondence between the excavation ring numbers in the actual construction sequence and the segment ring numbers in the numerical model, enabling a spatiotemporal alignment of field monitoring data and simulation results.

Figure 10 shows the cross-sectional settlements of the track bed at monitoring points 4–12 on both up and down lines. As the shield machine approaches the first diaphragm wall and prepares to cut through it, a slight uplift of the down-line track bed is observed [

1,

17,

18]. When the cutterhead is 2 m away from the first diaphragm wall, the change in settlement is approximately 0.5 mm. During the cutting process of first diaphragm wall, the settlement increases and reaches a peak value of 1.52 mm. Subsequently, as the shield continues to advance, a gradual rebound of the track bed occurs. This behavior is attributed to the combined effects of disturbances induced by shield tunneling and cutting, ground loss, and the temporary deficiency in grout body strength relative to the design requirement.

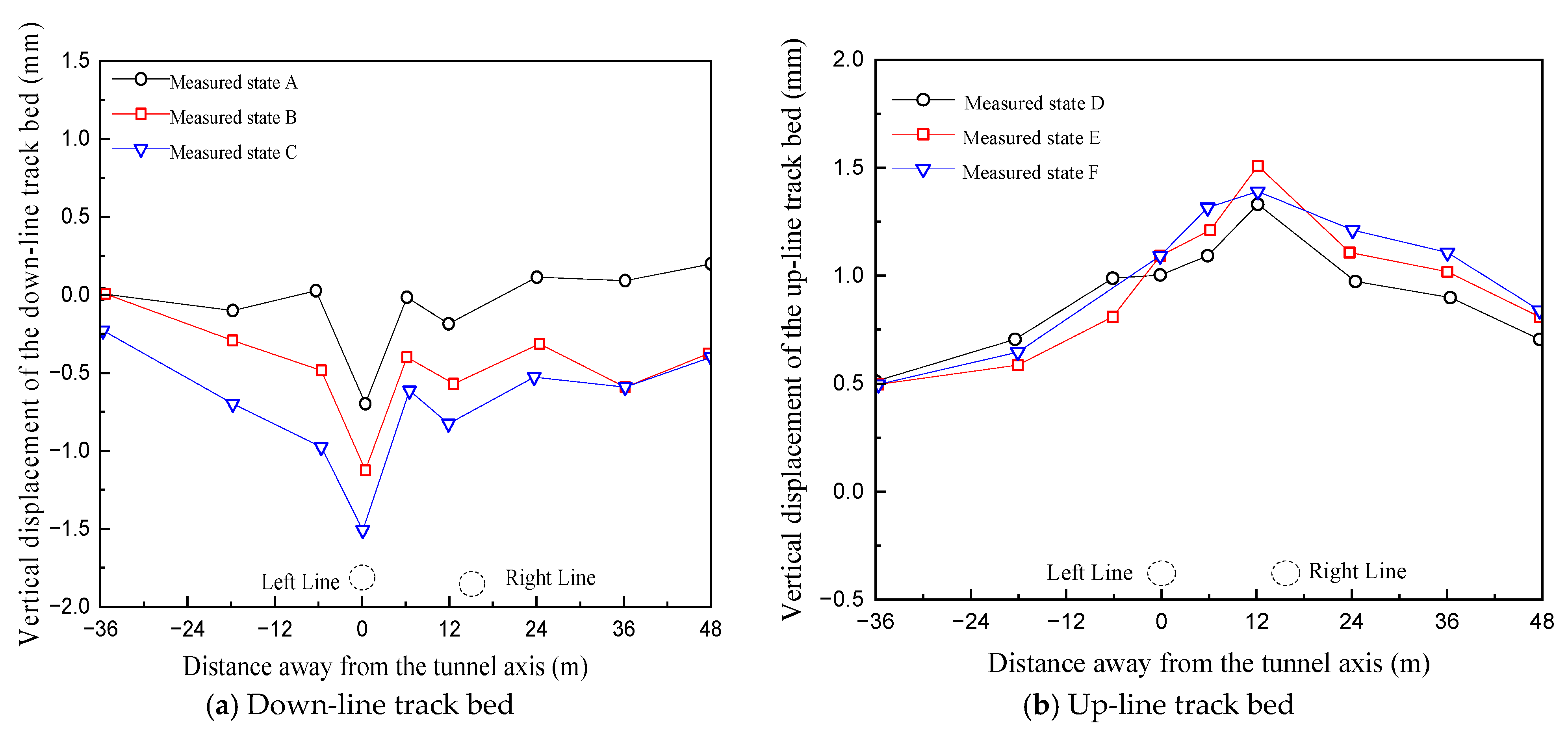

A comparison between the field monitoring data and the numerical simulation results is shown in

Figure 11. The vertical displacement trends of the up-line and down-line track beds are consistent with the simulations. However, the measured settlements of the up-line track bed are slightly smaller than the simulated values. This discrepancy is attributed to targeted deformation-control measures implemented during construction, such as deep-hole grouting reinforcement of the station base slab, adoption of a steel sleeve receiving technique, and timely reduction in soil chamber pressure during cutting. These measures effectively mitigate deformation. During the entire simulation process, the maximum lateral deformation of adjacent station walls reaches 2.49 mm. A slight uplift manifesting at the base slab center with a peak value of 2.54 mm. All obtained structural deformations remain well below the permission value of 5 mm, with observed maxima constituting only 50% of this safety threshold [

29].

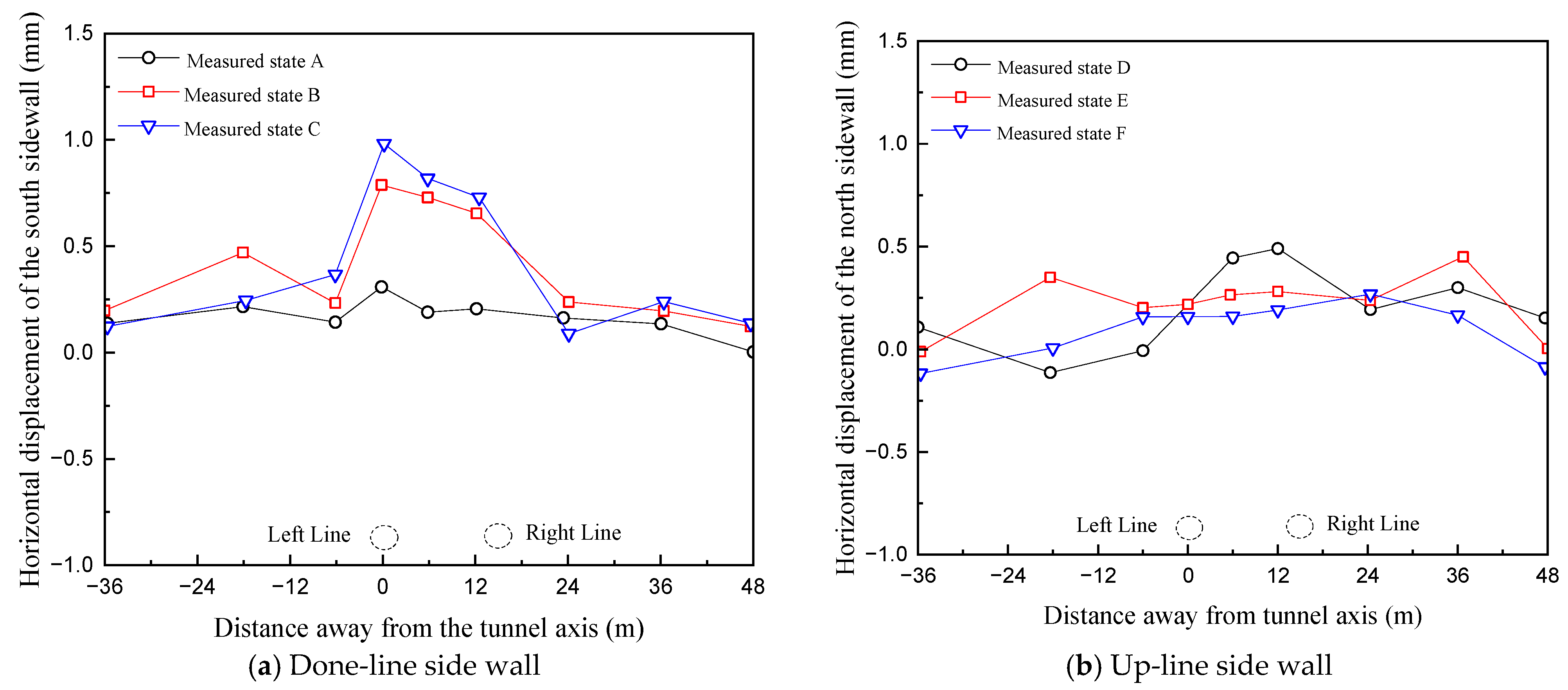

4.1.2. Overlying Station Side Walls Horizontal Displacement

For consistency, the aforementioned six shield states (A–F) are also used to describe the evolution of horizontal displacement in the overlying station side walls. The temporal variation in horizontal displacement in the north and south side walls during shield tunneling through the diaphragm walls is shown in

Figure 12. The side wall deformations are mainly concentrated within a zone extending approximately 2.5 times the tunnel diameter on either side of the shield axis. During the cutting of the first diaphragm wall, the south side wall exhibits a peak horizontal displacement of about 0.9 mm toward the south. Although the shield thrust is not directly applied to the station side walls, the close contact between the diaphragm walls and the side walls leads to lateral deformation through force transfer.

Figure 13 presents the horizontal displacement at monitoring points 4–12 on both the up and down lines. The influence of cutting through the second diaphragm wall on the station side walls is significantly weaker than that associated with the first diaphragm wall. This reduction is attributed to the protective effect provided by the vertical MJS reinforcement piles and the third diaphragm wall on the north side wall. A comparison of the field monitoring data and numerical simulation results reveals a high degree of agreement in the horizontal displacement trends of the station side walls, thereby validating the rationality and accuracy of the numerical model.

In summary, the track bed vertical displacement and the side wall horizontal displacement obtained from the numerical simulations show a good agreement with corresponding field measurements, with only small quantitative discrepancies. These findings demonstrate that the established numerical model is both reasonable and reliable, and that it can accurately capture the actual structural response of the station during shield tunneling construction.

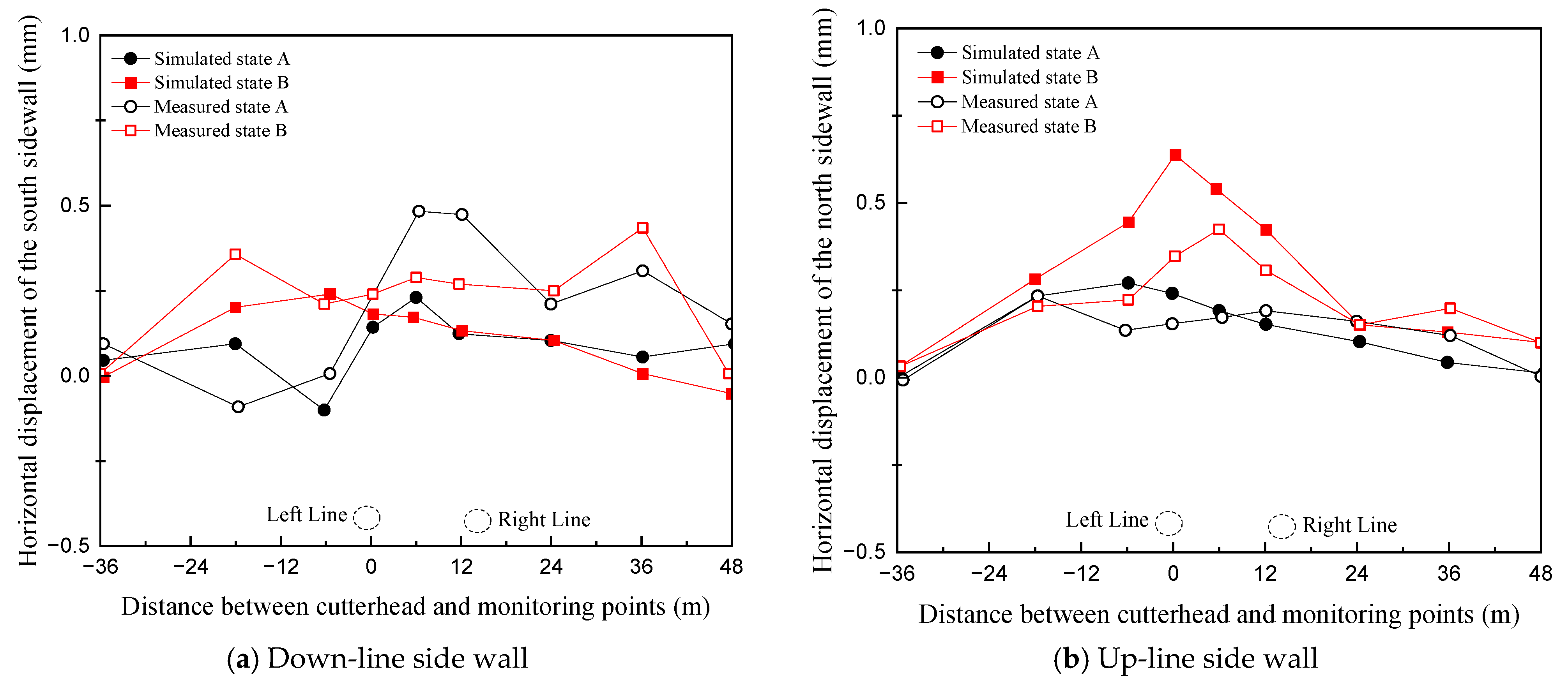

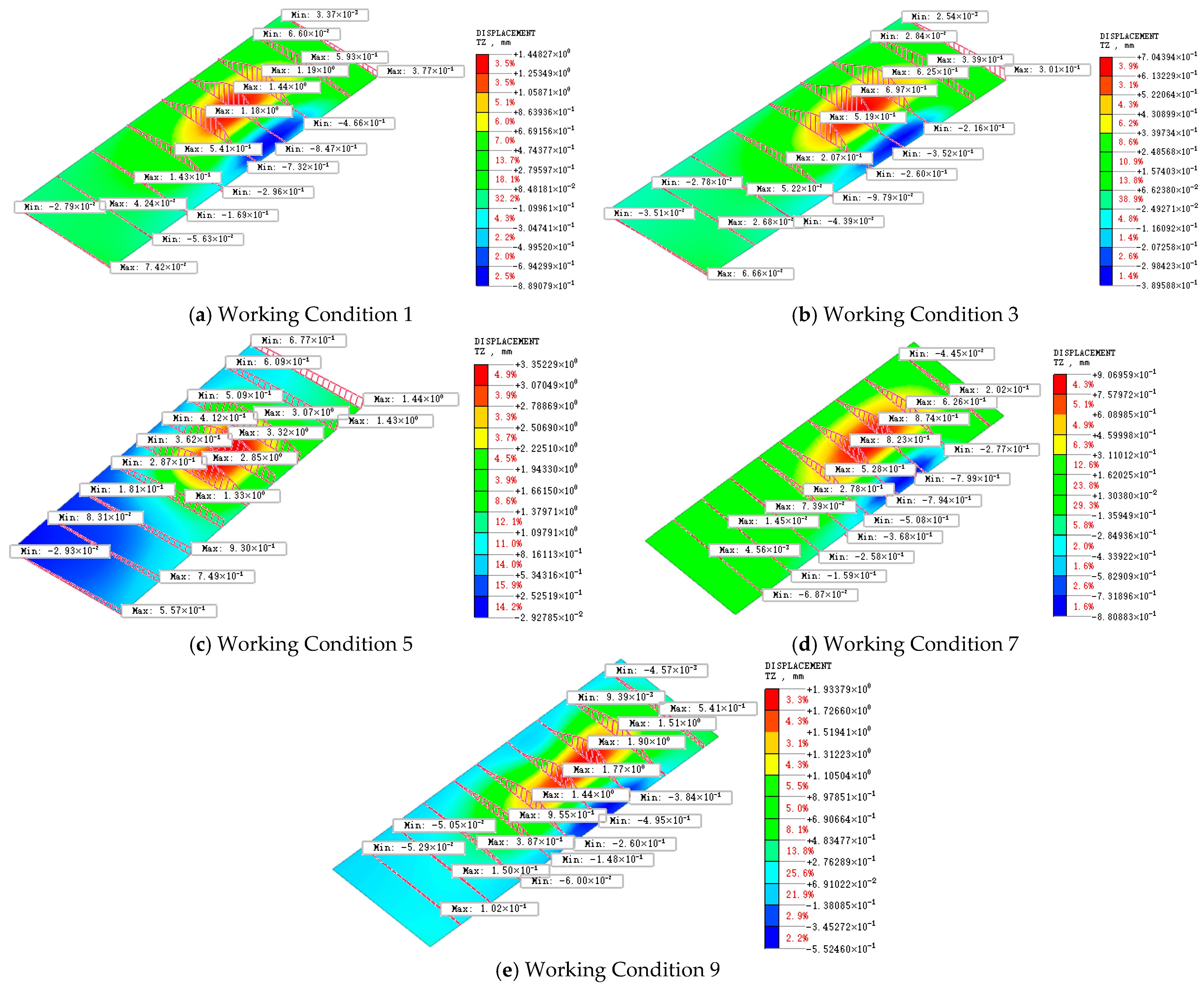

4.2. Influence of Different Cutterhead Load

To better understand the influence of shield thrust and torque on station structural deformations, the numerical model is further analyzed for optimizing construction parameters. Nine working conditions are simulated (

Table 4). Condition 1 corresponds to the actual field condition; conditions 2–5 investigate the relationship between thrust and structural deformation, whereas conditions 6–9 examine the relationship between torque and structural deformation. According to the design specifications, the tunnel structure settlement, horizontal displacement, and uplift should not exceed 5 mm, and the design allowable compressive stress for C30 concrete is 20 MPa.

4.2.1. Vertical Deformation of Station Base Slab

To analyze the influence of thrust on the vertical deformation of the station base slab, the following steps are performed using the established numerical model:

(a) Thrust and torque are applied as uniformly distributed loads to simulate structural deformation during cutting through the diaphragm wall;

(b) The base slab vertical deformation and the side wall lateral deformation are extracted;

(c) Mathematical analysis is carried out to explore the deformation and stress mechanism of the base slab under combined loading and to investigate the quantitative relationships among deformation, thrust, and torque.

Figure 14 shows the deformation of the station base slab during cutting of the first diaphragm wall under different working conditions.

As thrust and torque increase or decrease, the deformation of the station base slab varies accordingly, indicating a significant positive correlation between thrust/torque and base slab deformation. However, the magnitude and trend of deformation differ among the working conditions, indicating that the effects of thrust and torque on slab deformation are nonlinear and are influenced by soil conditions and construction parameters. To further quantify these relationships, the maximum deformation values of the base slab during cutting of the first diaphragm wall on the left line under each condition are extracted and analyzed. Based on these data, curve fitting is performed, and the results are shown in

Figure 15.

Figure 15a,b present the fitted relationships between thrust/torque and base slab deformation. The relationship between thrust and base slab deformation follows an upward-opening quadratic function, in which deformation increases markedly with increasing thrust. In contrast, the relationship between torque and base slab deformation is represented by a downward-opening quadratic function. Although deformation increases with torque, the influence of torque on base slab deformation is weaker than that of thrust.

In practice, the shield thrust is primarily used to overcome soil resistance and propel the machine forward. Excessive thrust leads to larger loads transferred to the base slab and consequently greater deformation. Therefore, MJS reinforcement is essential for shield tunneling in soft soil formations, such as those in Suzhou. These results indicate that the mechanisms by which thrust and torque affect base slab deformation are complex and nonlinear.

4.2.2. Lateral Deformation of Station Side Wall

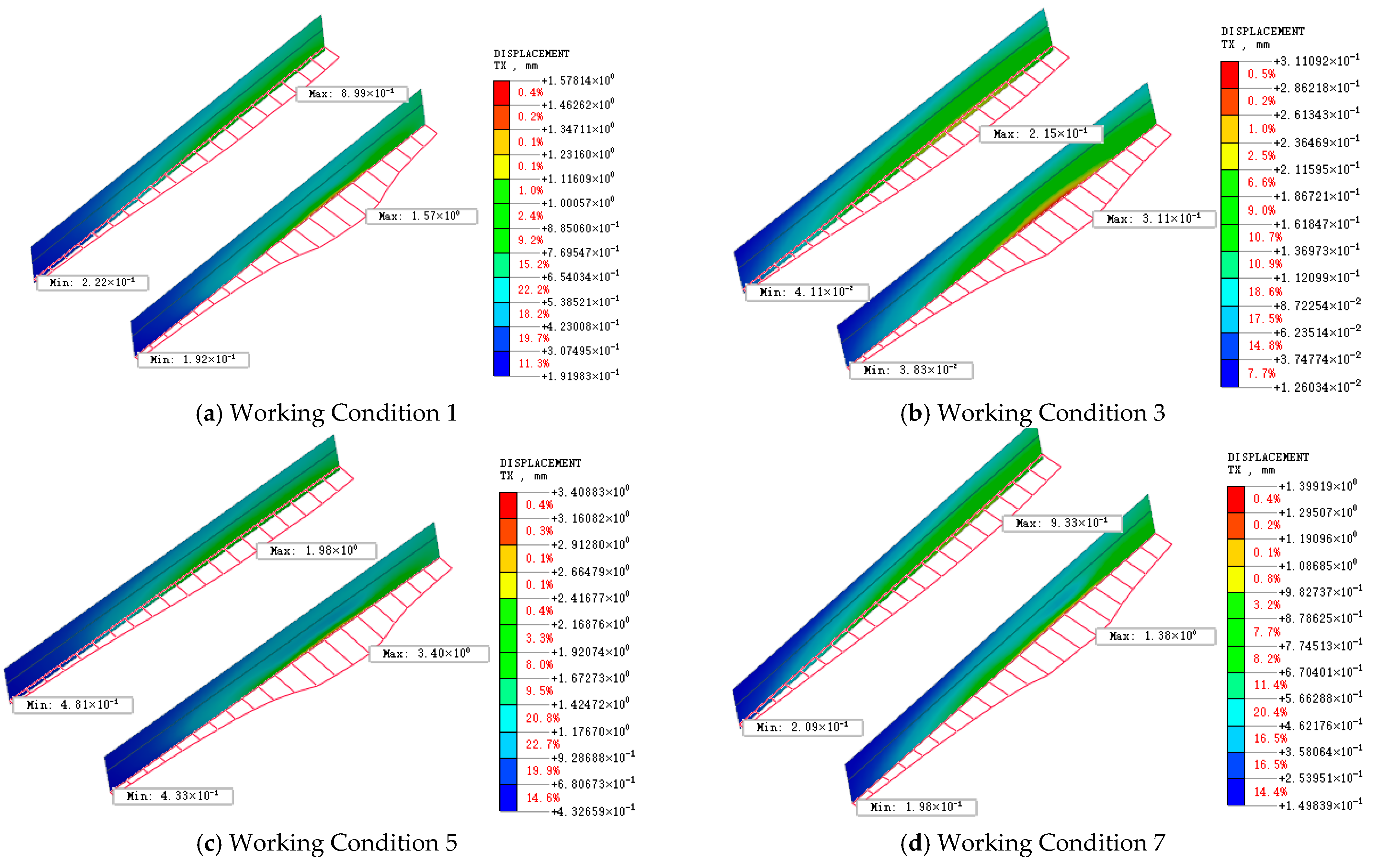

To further investigate the influence of thrust and torque on the lateral deformation of the station side walls, numerical simulations are conducted under the nine working conditions listed in

Table 4. The deformation of the side walls during cutting of the first diaphragm wall is selected as representative, as shown in

Figure 16.

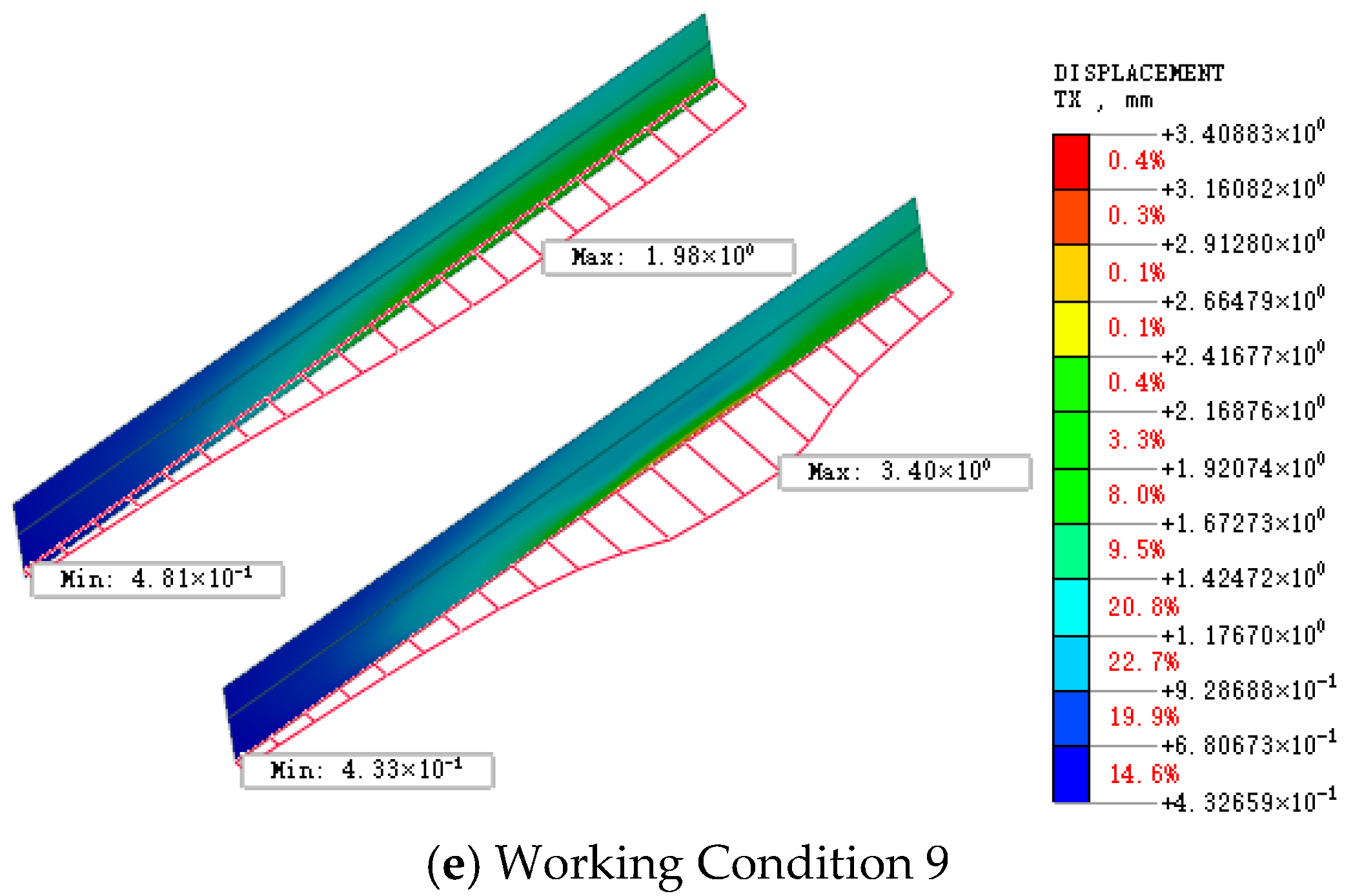

Figure 16 presents the simulated side wall deformations under the nine conditions. As thrust and torque increase or decrease, the lateral deformation of the side walls changes correspondingly, indicating a significant positive correlation between these loads and side wall deformation. The influence of thrust on side wall deformation is clearly greater than that of torque. This is because thrust acts in the same general direction as the observed side wall displacement and thus directly induces lateral deformation. In contrast, torque acts perpendicular to the direction of side wall deformation, which can be transmitted to the side wall via deformation of the contact region between the diaphragm wall and the side wall. This indirect transmission mechanism weakens the effect of torque. Based on the simulation data, curve fitting is performed and the results are shown in

Figure 17.

The relationship between thrust and side wall deformation follows an upward-opening quadratic function, with deformation increasing significantly as thrust increases. In contrast, the relationship between torque and side wall deformation follows a downward-opening quadratic function, where deformation initially increases and then tends to stabilize as torque increases. The effect of torque reaches a critical value at approximately 500 kN·m, beyond which further increases in torque produce negligible additional side wall deformation. This can be explained by the fact that thrust directly induces lateral deformation along the direction of wall displacement, whereas the torque is transmitted to the side wall through shear deformation in the surrounding strata. Once the torque exceeds the critical shear resistance of the soil, the incremental shear deformation is limited, leading to a plateau in side wall deformation.

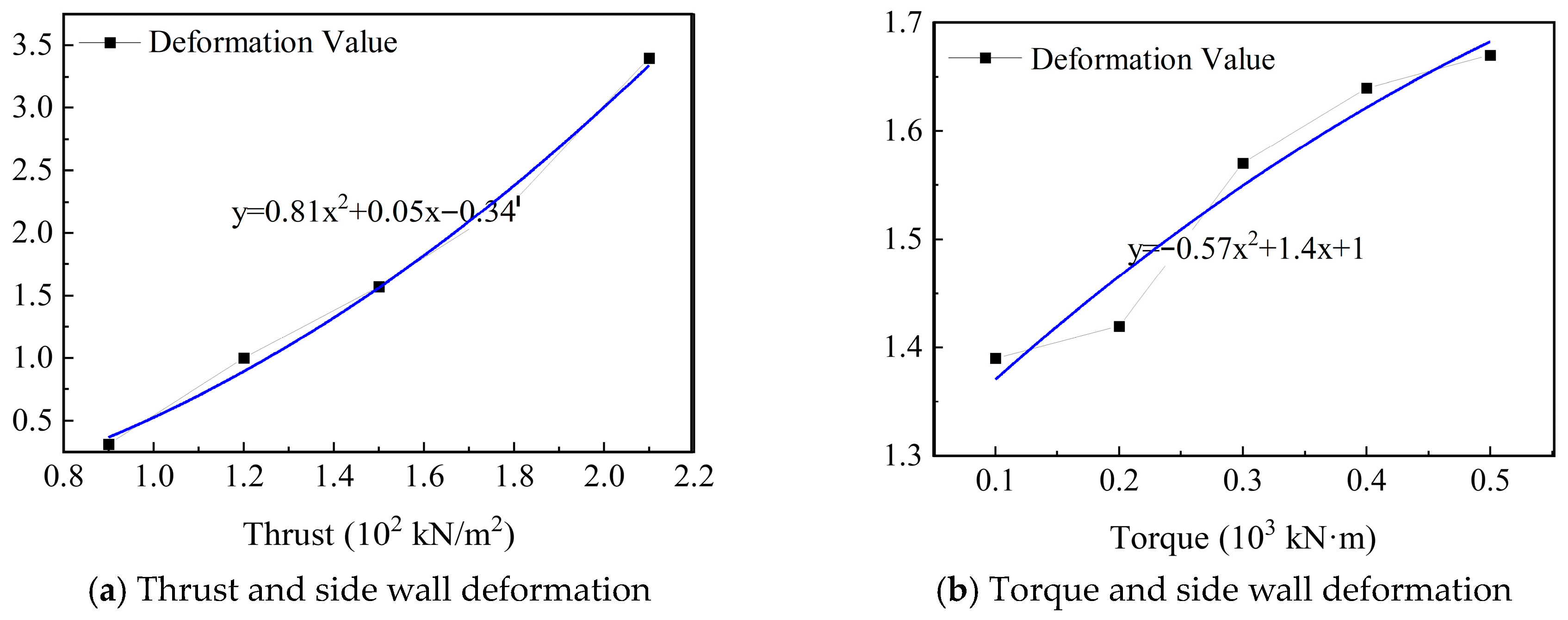

4.2.3. Stress Distribution of Base Slab and Side Wall

The stability of a station structure is governed not only by its lateral and vertical displacements but also by its internal stress state. The stress state is a key indicator of structural safety, as stresses exceeding design allowable limits may lead to damage or failure. Therefore, this section examines the changes in internal forces within the station structure under different loading conditions, and the in-plane stress distribution in the base slab and side walls is analyzed. The objective is to evaluate the load-bearing capacity and overall stability of the station.

Figure 18 illustrates the stress distribution in the station base slab and side walls during cutting through the first diaphragm wall of nine working conditions.

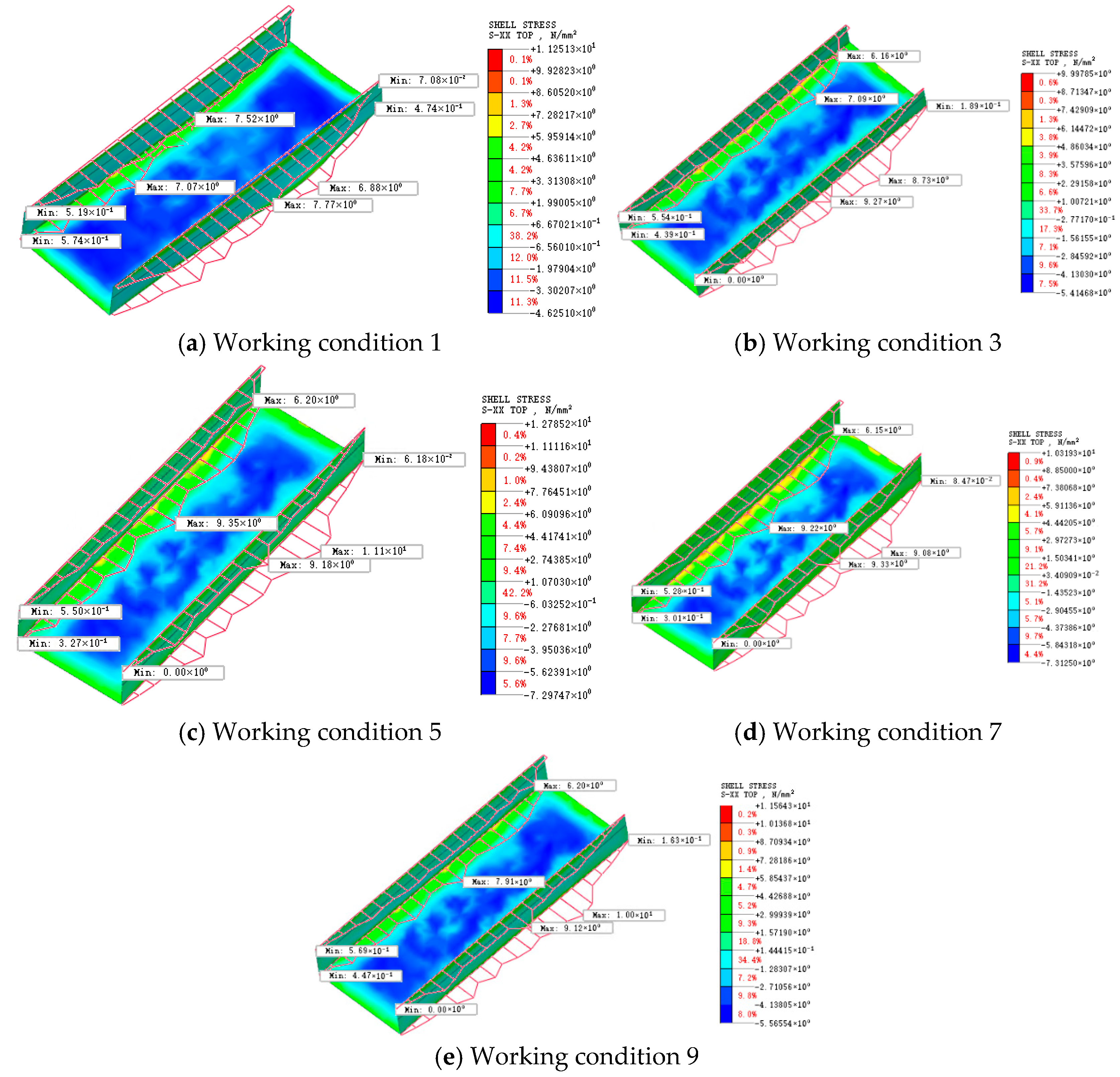

As thrust and torque increase or decrease, the stress levels in the station structure vary correspondingly, indicating a clear correlation between cutterhead loads and structural stress. It is also evident that variations in thrust have a more pronounced impact on structural stress than variations in torque. To further quantify these effects, the maximum stress values in the station structure during cutting of the first diaphragm wall on the left line under each working condition are extracted and analyzed. The curve-fitting results are shown in

Figure 19.

Thrust exhibits an upward-opening quadratic relationship with structural stress: the stress increases significantly with increasing thrust, and the rate of increase accelerates at higher thrust values. By contrast, torque exhibits a downward-opening quadratic relationship with structural stress, in which stress initially increases with torque and then stabilizes. A critical value for the effect of torque on station structural stress is observed at approximately 600 kN·m. This behavior arises because thrust acts directly as a line load on the station structure, causing direct amplification of stress, whereas torque is transmitted indirectly through soil shear stresses generated by cutterhead rotation. Once the torque exceeds the critical shear strength of the ground, additional torque contributes little to further stress growth.

Overall, the influence of thrust on structural stress is significantly greater than that of torque. Although increasing thrust or torque gradually raises the stress of station structure. Even under the maximum thrust and torque considered, the stresses in the station base slab and side walls remain below the design allowable limits. Further analysis indicates that when thrust reaches the maximum allowable capacity of the equipment, the internal forces in the station structure still satisfy the design safety requirements. This is attributed to the safety margins incorporated during the design phase. Consequently, for subsequent optimization of tunneling parameters, the vertical deformation of base slab and the lateral deformation of side walls are adopted as the primary assessment criteria for evaluating structural safety.

4.3. Limitations of Numerical Simulations

Although the proposed modeling strategy can reflect the structural response induced by shield machine cutting the reinforced concrete diaphragm wall, some shortcomings are still existed in current study:

(1) Diaphragm wall is assumed as a continuous elastic solid element without considering the distributions of steel rebars and the plastic behavior of concrete;

(2) Measured thrust and torque of shield cutterhead are equivalent to tunnel face pressures and moments at diaphragm walls;

(3) Equations obtained by the relationship between shield thrust/torque and structural deformation are governed by specific structural dimensions and material properties, extending these equations requires more case studies.

5. Conclusions

Based on the project of Suzhou Metro Line 8 undercrossing the station of Line 1, this study investigates the mechanical response of an existing metro station induced by shield machine cutting through the diaphragm wall. A refined three-dimensional numerical model is established by Midas/GTS NX for evaluating deformation characteristics of metro station and diaphragm walls. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Vertical displacements dominate the station base slab, with influence zones extending approximately 2.5 times the tunnel diameter. Diaphragm wall exhibits horizontal deformation orient opposite to the tunneling direction, while the maximum lateral deformation of adjacent station walls reaches 2.49 mm. A slight uplift manifesting at the base slab center with a peak value of 2.54 mm.

(2) Both thrust and torque are positively associated with the deformation magnitude of overlying structure. Increasing thrust exacerbates the lateral displacement of station base slab and side walls, whereas the influence of torque is gradually decreased. Precision thrust control is critical for deformation mitigation.

(3) All obtained structural deformations remain well below the permission value of 5 mm, verifying the feasibility of shield machine directly cutting through existing diaphragm walls. This approach aligns with sustainable urban development principles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W. and Y.S.; methodology, S.W.; software, L.G.; validation, T.Z. and D.W.; formal analysis, Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.S. and L.G.; project administration, S.W. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Post-funded Project of the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. Z_20240044; Approval No. 23FFXA004).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the constructive comments and dedicated efforts of the editors and reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Shejiang Wang, Lin Gui, Tao Zhang and Daogang Wang are employed by the company Suzhou Rail Transit Group Co., Ltd. Author Yingyin Shen is employed by the Soochow University. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, B.; Li, T.; Han, Y.; Li, D.; He, L.; Fu, C.; Zhang, G. DEM-Continuum Mechanics Coupling Simulation of Cutting Reinforced Concrete Pile by Shield Machine. Comput. Geotech. 2022, 152, 105036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Yang, Y.; Ji, M. Analysis of Ground Surface Settlement Induced by the Construction of a Large-Diameter Shield-Driven Tunnel in Shanghai, China. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 51, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.-W.; Zhu, H.-H.; Ma, X.-F.; Ma, Z.-Z. Pile Underpinning and Removing Technology of Shield Tunnels Crossing through Group Pile Foundations of Road Bridges. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2012, 34, 1217–1226. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L. Mechanical Responses and Safety Control of Composite Multi-Layered Ground and Built Environment due to Shield Tunneling in Urban Areas. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Zhu, H.; Ma, X.; Wang, R. A Case History of Shield Tunnel Crossing through Group Pile Foundation of a Road Bridge with Pile Underpinning Technologies in Shanghai. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 45, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Wang, F. Theory and Practice of Shield Tunneling Through Large-Diameter Reinforced Concrete Pile Groups; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X. Construction Technology of Metro Shield Continuously Crossing underneath Riverway and Railway in Silt Layer in Israel. Tunnel Constr. 2019, 39, 858–867. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wei, G.; Li, B.; Li, Q.; Yao, W. Field Measurement Analysis of the Influence of Double Shield Tunnel Construction on Reinforced Bridge. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 81, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Jia, S.; Chen, W.; Zeng, P.; Wang, J. Modelling Analysis of the Influence of Shield Crossing on Deformation and Force in a Large Diaphragm Wall. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 72, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Wang, R.; Shi, P.; Li, Y.; Chen, J. Seismic Response and Damage Analysis of Underground Structures Considering the Effect of Concrete Diaphragm Wall. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 116, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-N.; Shen, S.-L.; Chen, R.-P.; Zhou, A. Three-Dimensional Numerical Modelling on Localised Leakage in Segmental Lining of Shield Tunnels. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 122, 103549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Tan, Z.; Huangfu, S.; He, F.; Han, Y.; Gao, B.; Zhen, F. Study on deformation control measures for metro mined tunnels closely undercrossing existing stations in loess areas. Urban Rapid Rail Transit 2025, 38, 120–128. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Jia, B. Analysis of Excavating Foundation Pit to Nearby Bridge Foundation. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2012, 5, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Jiang, Y.; Geng, D.; Huang, Z.; Ding, H. Numerical Investigation of the Combined Influence of Shield Tunneling and Pile Cutting on Underpinning Piles. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 896634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z. Influence of macadamia nutshell particles on the apparent density and mechanical behavior of cement-based mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, J.; Liang, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z. A new improved particle swarm algorithm for optimization of anchor lattice beam support structures. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, T.; Wang, S.; Fu, J.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, X. Numerical Examination of EPB Shield Tunneling–Induced Responses at Various Discharge Ratios. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2019, 33, 04019021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Wen, S.; Li, D.; Wang, D.-Y.; Fang, H.-C. Study on Launch Tunneling Parameters of a Shield Tunnel Buried in Pebble Soil with Existing Pipelines Based on Discrete-Continuous Coupling Numerical Method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 129, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Zeng, Z.; Gu, D. Numerical Simulation and Analysis of the Pile Underpinning Technology Used in Shield Tunnel Crossings on Bridge Pile Foundations. Undergr. Space 2020, 6, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ma, S.-J.; Hong, K.-R.; Ding, Y.-G. Effects on Upper Masonry Structures Caused by Double-Line Parallel Shield Cutting Group Pile Construction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Qaytmas, A.M.; Lu, D.; Du, X. Stress Path of the Surrounding Soil During Tunnel Excavation: An Experimental Study. Transport. Geotech. 2023, 38, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, K.; Wang, Y.; Lin, G.; He, C. Soil Disturbance Induced by EPB Shield Tunneling in Multilayered Ground with Soft Sand Lying on Hard Rock: A Model Test and DEM Study. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 130, 104738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qu, T.; Fang, Y.; Fu, J.; Yang, J.-S. Stress Responses Associated with Earth Pressure Balance Shield Tunneling in Dry Granular Ground Using the Discrete-Element Method. Int. J. Geomech. 2019, 19, 04019050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, H.; Hai, Z.; Helin, F.; Shaokun, M.; Ying, L. Deformation Response Induced by Surcharge Loading above Shallow Shield Tunnels in Soft Soil. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 24, 2533–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Pham, K.; Park, S.; Oh, J.-Y.; Choi, H. Determination of Effective Parameters on Surface Settlement During Shield TBM. Geomech. Eng. 2020, 21, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.-T.; Chen, X.-S.; Su, D.; Han, K.; Zhu, M. An Analytical Model to Evaluate the Resilience of Shield Tunnel Linings Considering Multistage Disturbances and Recoveries. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 127, 104581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Tao, R.; Bao, X.; Wu, X.; Qiu, T.; Shen, J.; Han, Z.; Chen, X.-S. Seismic Resilience Evolution of Shield Tunnel with Structure Degradation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wu, Q. Effect of the Excavation Clearance of an Under-Crossing Shield Tunnel on Existing Shield Tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 78, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50911-2013; Code for Monitoring Measurement of Urban Rail Transit Engineering. China Academy of Urban Planning and Design: Beijing, China, 2013.

Figure 1.

Layout of metro line 8 project.

Figure 1.

Layout of metro line 8 project.

Figure 2.

Plane and cross-section view of tunneling interval.

Figure 2.

Plane and cross-section view of tunneling interval.

Figure 3.

Distribution of steel rebars in diaphragm wall (unit: mm).

Figure 3.

Distribution of steel rebars in diaphragm wall (unit: mm).

Figure 4.

Layout of monitoring points.

Figure 4.

Layout of monitoring points.

Figure 5.

Details of numerical model.

Figure 5.

Details of numerical model.

Figure 6.

Relative positions of structures.

Figure 6.

Relative positions of structures.

Figure 7.

Simulation process.

Figure 7.

Simulation process.

Figure 8.

Load configuration.

Figure 8.

Load configuration.

Figure 10.

Measured vertical displacement of track bed.

Figure 10.

Measured vertical displacement of track bed.

Figure 11.

Comparison between measured and simulated vertical displacement.

Figure 11.

Comparison between measured and simulated vertical displacement.

Figure 12.

Measured horizontal displacement of side walls (left-line).

Figure 12.

Measured horizontal displacement of side walls (left-line).

Figure 13.

Comparison between measured and simulated cross-sectional deformation of side walls (left-line).

Figure 13.

Comparison between measured and simulated cross-sectional deformation of side walls (left-line).

Figure 14.

Deformation of base Slab.

Figure 14.

Deformation of base Slab.

Figure 15.

Relationship of base slab deformation against cutterhead load.

Figure 15.

Relationship of base slab deformation against cutterhead load.

Figure 16.

Deformation of the station side wall during the cutting of the first diaphragm wall.

Figure 16.

Deformation of the station side wall during the cutting of the first diaphragm wall.

Figure 17.

Relationship of side wall deformation against cutterhead load.

Figure 17.

Relationship of side wall deformation against cutterhead load.

Figure 18.

Stress cloud map of the station base slab during cutting of the first diaphragm wall (left line).

Figure 18.

Stress cloud map of the station base slab during cutting of the first diaphragm wall (left line).

Figure 19.

Relationship of side wall stress against cutterhead load.

Figure 19.

Relationship of side wall stress against cutterhead load.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of soil.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of soil.

| Soil Type | Unit Weight

γ/(kN·m−3) | Elastic Modulus Es/(MPa) | Possion’s Ratio μ | Cohesion c/(kPa) | Internal Friction Angle φ/(°) |

|---|

| 1-1 Fill | 18.0 | 3.57 | 0.20 | 2.0 | 15.0 |

| 3-1 Clay | 20.0 | 3.57 | 0.31 | 61.5 | 15.0 |

| 3-2 Silty Clay | 19.2 | 3.56 | 0.32 | 28.6 | 14.7 |

| 3-3 Clayey silt with silty sand | 19.3 | 7.54 | 0.32 | 7.5 | 30.2 |

| 4-2 Silty sand with silty clay | 19.8 | 15.20 | 0.32 | 2 | 32.5 |

| 5-1 Silty clay | 19.2 | 5.18 | 0.33 | 25.1 | 14.6 |

| 6-1 Clay | 20.3 | 11.19 | 0.31 | 59.2 | 15.1 |

| 6-2 Silty clay | 19.3 | 11.29 | 0.32 | 28.1 | 14.9 |

Table 2.

Structural material parameters.

Table 2.

Structural material parameters.

| Structural Components | Element Type | Unit Weight

γ/(kN·m−3) | Elastic Modulus

Es/(MPa) | Possion’s Ratio

μ |

|---|

| Diaphragm wall | 3D Solid | 25 | 3.0 × 104 | 0.2 |

| Horizontal MJS zone | 20 | 100 | 0.3 |

| MJS isolation piles | 20 | 700 | 0.3 |

| Station piles | 1D Beam | 25 | 3 × 104 | 0.35 |

| Slab | 2D Shell | 25 | 3.0 × 104 | 0.2 |

| Shield shell | 210 | 2.5 × 108 | 0.2 |

| Tunnel segment (Lining) | 25 | 5 × 104 | 0.3 |

| Grouting | 22.5 | 4 × 104 | 0.37 |

Table 3.

Correspondence between model simulation and actual construction sequence.

Table 3.

Correspondence between model simulation and actual construction sequence.

| Monitoring Date | Construction Log | Model Step (Ring No.) | Analysis Stages |

|---|

| Left Line | Right Line |

|---|

| 28 February 2023 | 2 m from the first wall | MJS construction | Left ring 6 | A |

| 1 March 2023 | Cutting the first wall | MJS construction stopped | Left ring 8 | B |

| 2 March 2023 | 5 m beyond the first wall | | Left ring 13 | C |

| 3 March 2023 | 10 m beyond the first wall | | Left ring 17 | |

| 4 March 2023 | 2 m from the second wall | | Left ring 22 | D |

| 5 March 2023 | Cutting the second wall | | Left ring 26 | E |

| 6 March 2023 | 5 m beyond the second wall | | Left ring 28 | F |

| 7 March 2023 | Left line completed; Deep grouting at the station | | Left ring 32 | |

| 25 May 2023 | | 2 m from the first wall | Right ring 4 | A |

| 26 May 2023 | | Cutting the first wall | Right ring 6 | B |

| 27 May 2023 | | 5 m beyond the first wall | Right ring 11 | C |

| 28 May 2023 | | 10 m beyond the first wall | Right ring 15 | |

| 29 May 2023 | | 2 m from the second wall | Right ring 20 | D |

| 30 May 2023 | | Cutting the second wall | Right ring 24 | E |

| 31 May 2023 | | 5 m beyond the second wall | Right ring 26 | F |

| 1 June 2023 | | Right line completed; Deep grouting at the station | | |

Table 4.

Working conditions.

Table 4.

Working conditions.

| Working Conditions | Thrust (kN/m2) | Torque (kN·m) |

|---|

| 1 | 150 | 300 |

| 2 | 90 | 300 |

| 3 | 120 | 300 |

| 4 | 180 | 300 |

| 5 | 210 | 300 |

| 6 | 150 | 100 |

| 7 | 150 | 200 |

| 8 | 150 | 400 |

| 9 | 150 | 500 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).