1. Introduction

Atmospheric deposition, runoff, and groundwater input are the main external sources of nitrogen nutrients in the coastal marine ecosystem, significantly affecting primary productivity [

1,

2,

3]. In recent years, nitrogen input in coastal water via atmospheric deposition has increased dramatically due to the continuous rise in atmospheric–anthropogenic nitrogen-containing pollutant emission [

4,

5,

6]. Previous studies have predicted that the total nitrogen deposition in China’s coastal water and the northwestern Pacific Ocean will be 1.0 to 1.5 times higher in 2030 compared to 2000 [

7]. Modeling assessments have also indicated that nitrogen and phosphorus deposition in coastal water is equivalent to the riverine input in certain sea areas [

8]. In extreme cases, atmospheric nitrogen deposition input could even exceed input from riverine systems. The annual atmospheric ammonia deposition in the East China Sea exceeded the annual ammonia deposition from the Yangtze River [

9,

10]. Due to the limitations of marine observation conditions and data scarcity, the impact of atmospheric nitrogen deposition on seawater nutrients was severely underestimated [

2,

11,

12,

13].

The impact of atmospheric nitrogen deposition on the marine ecological environment has attracted widespread attention. Previous studies have shown that the input of bioavailable inorganic nitrogen and dissolved organic nitrogen via atmospheric deposition, combined with groundwater input, accounted for 20% to 50% of the external nitrogen input in the coastal water of North America and Europe [

14,

15]. On the eastern coast of North America, the nitrogen deposition flux was approximately 50 mmol·N·m

−2·a

−1, which was dominated by wet deposition and exhibited distinct seasonal variability [

16,

17]. In contrast, atmospheric nitrogen deposition along the South Pacific coast was mainly dominated by dry deposition. Along the eastern coast of North America and the eastern Gulf of Mexico, nitrogen input from atmospheric deposition has exceeded riverine input, contributing approximately 30% of the inorganic nitrogen in coastal surface seawater [

15]. Studies showed that dry nitrogen deposition was dominated by nitric acid, accounting for more than 70% of the total dry nitrogen flux, while wet nitrogen deposition was dominated by nitrate and nitrite, accounting for 40–60% of the total nitrogen deposition [

18,

19].

Long-term monitoring in the Chesapeake Bay showed that atmospheric nitrogen deposition provided approximately 25% to 40% of the total nitrogen input [

20]. Additionally, observational data from a coastal observation station in southern Britain indicated that the proportion of new primary production supported by nitrogen deposition from atmospheric aerosol was about 22.4% [

21]. In the East Sea and Yellow Sea of China, the deposition flux of atmospheric nutrients was dominated by wet deposition [

22]. About 65% of the inorganic nitrogen and 70% of the inorganic phosphorus in the surface nutrients of the Yellow Sea originated from atmospheric deposition [

23]. The nitrogen supply would increase by at least 3 times if the dry deposition of nitrate and ammonium was taken into account [

24]. The inorganic nitrogen deposition input in the Bohai Sea exceeded the riverine input, with atmospheric ammonium deposition being 5 to 10 times greater than the riverine ammonium input [

25,

26,

27]. The atmospheric dry deposition of ammonia and nitric acid nitrogen over the East China Sea and Yellow Sea was 270,000 tons and 160,000 tons, respectively, in 2002 [

10,

28]. The atmospheric ammonia nitrogen input to the entire East China Sea was about 251,000 tons, accounting for 66% of the total nitrogen input in 2004. The annual total atmospheric ammonia input to the Yellow Sea was 195,000 tons, accounting for 88% of the total nitrogen input [

29].

Currently, research on atmospheric nitrogen deposition in coastal water is mainly focused on the East China Sea, Yellow Sea, and Bohai Sea, which suggests that atmospheric nitrogen input may increase the phytoplankton concentration and result in algal blooms in Jiaozhou Bay and the Bohai Sea [

30,

31]. However, there are relatively few studies focusing on atmospheric nitrogen deposition in the coastal area of Southeastern China. These areas are located along the western coast of the Taiwan Strait with a typical subtropical monsoon climate. They are influenced by the “funneling effect” caused by the high mountains on both sides of the strait [

32,

33]. Atmospheric pollutants emitted from North China and the Yangtze River Delta can be transported along the Fujian coast in autumn and winter. But during the warm season, clean air masses originating from the ocean dilute atmospheric pollutants in this area [

34]. Observation and simulation studies have shown that the input of atmospheric nitrogen deposition in the coastal water of Xiamen could support approximately 13% of the region’s primary productivity [

35].

This study focuses on the characteristics of dry and wet atmospheric nitrogen deposition and its influence on nutrients in Xiamen’s coastal water. Samples of atmospheric nitrogen from dry and wet deposition were collected to analyze the source and deposition flux in Xiamen’s coastal area. An atmospheric nitrogen deposition model was developed to investigate the impact of atmospheric nitrogen deposition on the coastal water nutrients and ecological environment.

2. Methods

2.1. Observational Location

Xiamen is located in the southern part of the subtropical zone and characterized by a southern subtropical marine monsoon climate. The annual average precipitation is approximately 1432.2 mm. Generally, precipitation is primarily concentrated in April to September, accounting for about 80% of the annual total precipitation. The sampling site is situated on the rooftop of the 10th Research Building (about 45 m above sea level) at the Marine Atmospheric Environment Monitoring Station in Xiamen, China (24°16′ N, 118°05′ E,

Figure 1), which is closed to the coast and free from obstruction by surrounding structures, ensuring minimal interference with sample collection.

2.2. Observation and Measurement Methods

Dry deposition samples for atmospheric particulate matter were collected using a YH-1000 sampler (Qingdao Jingcheng Instrument Co., Ltd. Qingdao, China) with a sampling flow rate of 1.0 Nm3·min−1. Wet deposition samples of atmospheric precipitation were collected using an MH310 atmospheric dry–wet deposition sampler (Minhope, Qingdao, China). The sampling of atmospheric dry and wet deposition was conducted in February, May, August, and November in 2023. Dry and wet deposition samples were collected continuously for one month in each quarter, with dry deposition samples collected as daily integrated samples (once every 24 h).

The dry and wet deposition samples were analyzed using an ion chromatography system (Thermo Scientific Co., Ltd., Waltham, MA, USA), including a DIONEX ICS-2500 (for cation analysis) and DIONEX ICS-90A (for anion analysis). The laboratory environment was strictly controlled in terms of temperature (25 ± 1 °C) and humidity (<80%) to ensure stable analytical conditions. The detection limits of different ions are 0.009 mg·L−1, 0.02 mg·L−1 and 0.03 mg·L−1 for NH4+, NO2−, and NO3−, respectively.

2.3. Source Appointment of Aerosol N

In this study, the aerosol N source was apportioned using a modified positive-definite matrix factor (PMF) model, which was based on the mass concentration of different aerosol components. The details of the PMF methodology have been comprehensively described by Wang et al. (2022) [

35].

2.4. Inorganic Nitrogen Deposition Flux Calculation

The atmospheric nitrogen deposition flux calculation model for Xiamen’s coastal area was developed by integrating relevant marine environmental parameters, which were obtained from satellite remote sensing. The model’s key parameters, such as wind speed, temperature, humidity, wave condition, particulate matter properties, etc., include the transport and distribution characteristics of atmospheric particulate matter over the sea surface. Meteorological, environmental, and wave parameters, along with other relevant data, from satellite remote sensing are required in the model to calculate the deposition velocity of atmospheric particulate matter. The model discretizes the spatial observation and computes the atmospheric nitrogen deposition flux for each discrete grid cell based on the in situ coastal observational data and satellite remote sensing data.

Generally, the deposition flux of fine particles can be calculated as follows [

36]:

where α is the crushing surface coefficient,

Cz is the concentration of a specific pollutant at height

z (µg·m

−3),

Cδs and

Cδb are the concentrations at the top of the deposition layer above the smooth water surface and breaking water surface (µg·m

−3), respectively,

Vgd is the gravitational settling velocity based on the dry particle size (cm·s

−1), and

Kab and

Kas are the transfer coefficients for the smooth surface and breaking surface, respectively.

The flux through the deposition layer can be expressed as

where

Vgw is the gravitational settling velocity of wet particles (cm·s

−1) and

C0 is the concentration at the air–seawater interface.

Under steady-state conditions, the calculation formula for the dry deposition velocity of particles above the sea surface can be derived as follows:

where

Vdi is the deposition velocity of particles with a specific size (cm·s

−1);

Kss is the transfer coefficient for the smooth surface;

Kbs is the transfer coefficient for the breaking surface;

Kab is the turbulent transfer coefficient for the breaking surface;

Kas is the turbulent transfer coefficient for the smooth surface;

Km is the lateral transfer coefficient;

Vgw is the gravitational settling velocity of wet particles (cm·s

−1); and

Vgd is the gravitational settling velocity of dry particles (cm·s

−1).

The settling velocity is calculated based on the aerosol size spectrum [

36]:

where

i represents the size distribution of the particles and

dri is the coefficient based on the size distribution of the particles.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Aerosol Nitrogen from Dry and Wet Deposition

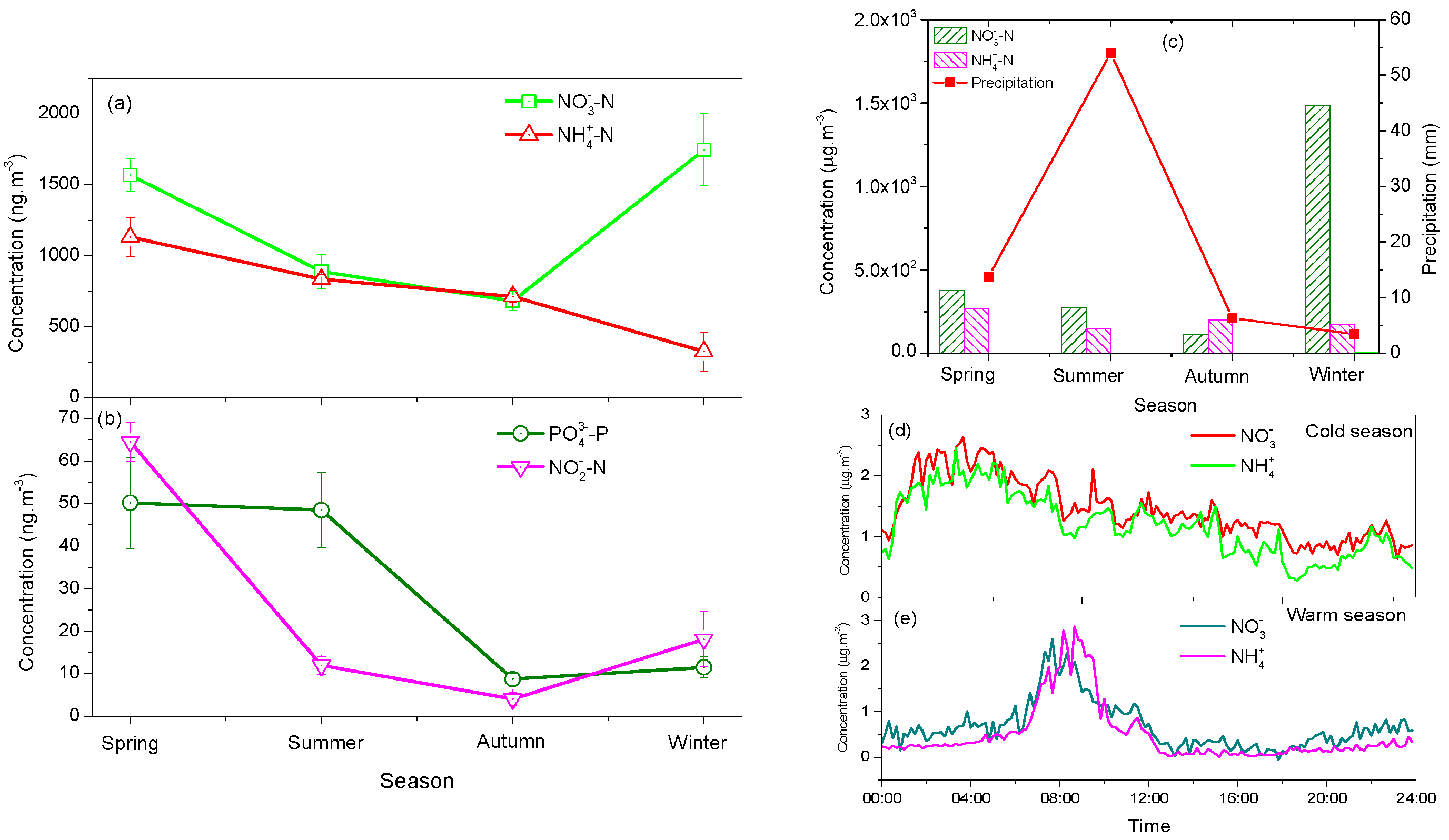

Figure 2a,b show that NH

4+-N and NO

3−-N were the predominant inorganic nitrogen deposition species in Xiamen’s coastal area. NH

4+-N exhibited a relatively high concentration in spring (1100 ng·m

−3) and dropped to about 300 ng·m

−3 in winter. In contrast, a high NO

3−-N concentration was found in winter and spring, with a concentration of 1800 ng·m

−3 and 1600 ng·m

−3, respectively. This reverse variation may be associated with the sources and transformation processes of different nitrogen forms. Specifically, the elevated concentration of NH

4+-N in spring was driven by ammonia volatilization from agricultural fertilization, while the increase in NO

3−-N in winter was likely associated with the enhancement of anthropogenic emission and pollutant transport from northern Xiamen. An extremely low concentration of PO

43−-P and NO

2−-N was present, as seen in

Figure 2b, but high levels occurred in spring and low concentrations were detected in winter.

The NO

3−-N concentration was extremely high in the precipitation (1800 μg·m

−3), exceeding that observed during summer rainfall by more than five times, as shown in

Figure 2c. The highest rainfall amount was present in the summertime, while the concentration of NO

3−-N in rainwater was extremely low in the summertime. This phenomenon was mainly affected by the concentration of NO

3− in the atmosphere and the amount of rainfall. As seen in

Figure 2b, the NO

3− concentration was relatively low in summer. High rainfall amounts in the summertime led to the dilution of NO

3− concentration in rainwater.

The diurnal variation in NO

3−-N and NH

4+-N in the cold season and warm season revealed the differential influence of atmospheric nitrogen. In the cold season, the concentration of NO

3− and NH

4+ was low between 0:00 and 4:00 and gradually increased, then maintained a relatively fluctuating state (

Figure 2d). In the warm season, the concentration of NO

3− and NH

4+ was low before 6:00 and increased rapidly in the morning, then gradually decreased in the afternoon (

Figure 2e). This diurnal pattern was closely associated with the diurnal variation in the height of the boundary layer and human activities. Intensified human activities during the daytime, such as transportation and industrial emissions, provided an adequate source of nitrogen, which was consistent with the observations obtained from Xiamen’s coastal area [

37].

The seasonal and diurnal variations in atmospheric nutrients were determined from the combined effect of pollution source emissions, meteorological conditions, and chemical transformation processes. The pronounced seasonal variability of nitrogen, particularly NH4+-N and NO3−-N, reflected the dominant role of seasonal differences in anthropogenic sources. These characteristics provided a foundation for further quantifying the contribution of atmospheric nutrient deposition to the coastal marine ecosystem.

3.2. Source Appointment of Atmospheric Nutrient Deposition

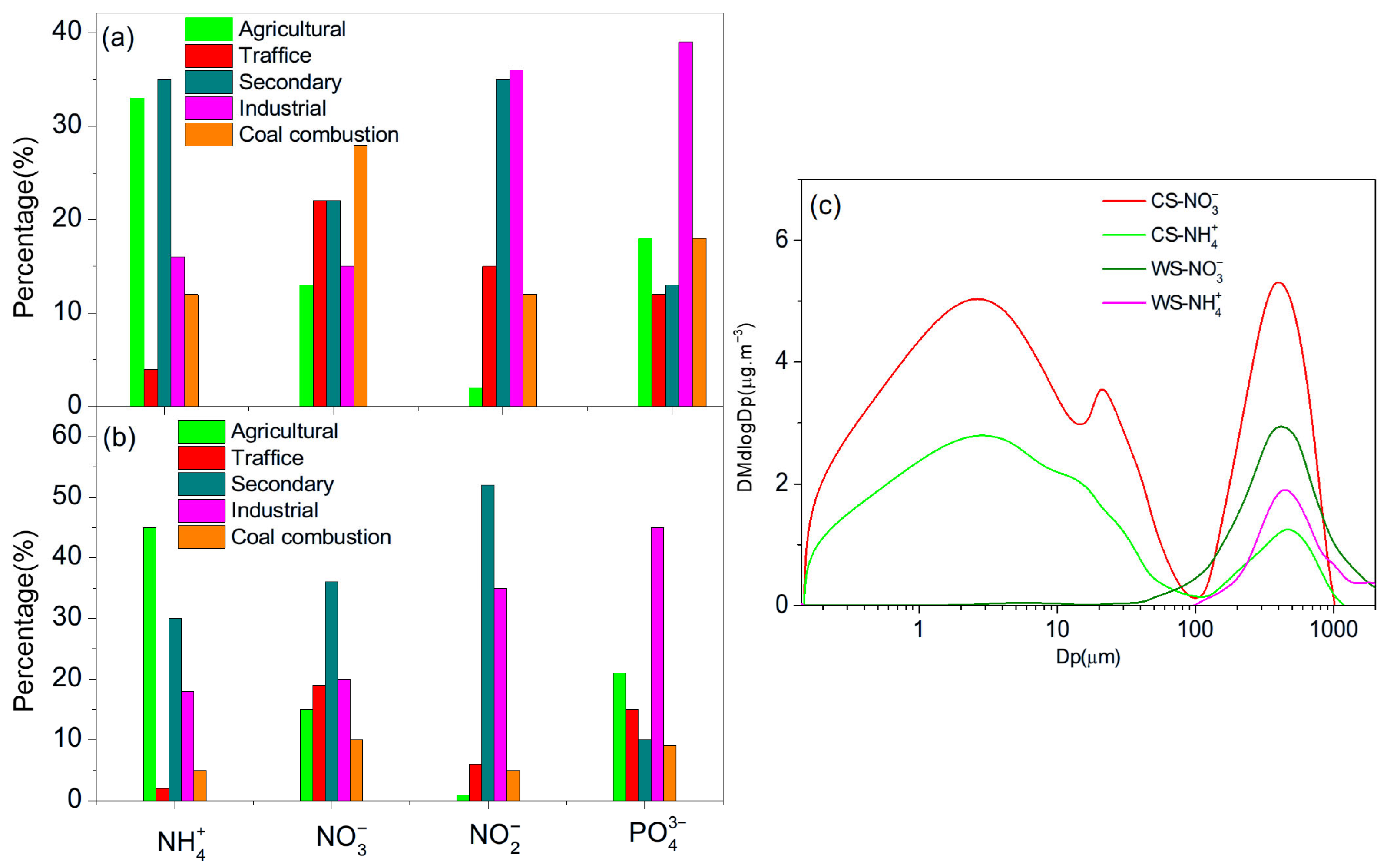

Atmospheric nitrogen deposition in Xiamen’s coastal area exhibited distinct seasonal variations, indicating that atmospheric nitrogen was affected by different sources.

Figure 3a,b present the sources of atmospheric nitrogen in Xiamen’s coastal area during the cold and warm seasons. Agricultural emission was the main source of NH

4+, with a contribution of over 45% in the warm season and 35% in the cold season, followed by secondary and industrial sources. This indicated that the emission of NH

3 from agricultural activities was the main source of NH

4+.

In contrast, traffic, secondary sources, and coal combustion were the main sources of NO3−, accounting for 24%, 25%, and 28%, respectively. This indicated that traffic emission and secondary formation in Xiamen’s coastal area had a significant impact on atmospheric NO3− deposition. The main sources of NH4+ and NO3− were different in the cold and warm seasons. The contribution of agricultural and secondary sources increased in the warm season, which was consistent with the temporal pattern of agricultural activities. In addition, the high temperature in summer facilitated the release of NH3 during fertilization. Meanwhile, strong solar radiation with high humidity in the summer benefited secondary aerosol formation. In contrast to the warm season, the contribution of coal combustion sources to NO3− increased significantly in the cold season.

Figure 3c shows the particle size distributions of NH

4+ and NO

3−. NH

4+ and NO

3− particles exhibited a bimodal distribution in the cold season, with a peak value of 0.03 μm and 0.5 μm, respectively. During the warm season, NH

4+ and NO

3− exhibited a unimodal distribution and most particles were concentrated in the 0.1–1 μm. The average particle sizes of NH

4+ and NO

3− in the warm season were larger than those in the cold season, which was related to the sources of NH

4+ and NO

3− in the cold and warm seasons. The particulate matter concentration was reduced due to the influence of prevailing southwest winds, high temperatures, and precipitation in the warm season. In contrast, stagnant weather conditions led to the accumulation of fine particulate matter, resulting in increased pollution in the cold season. Air masses controlled by the northeast monsoon were often affected by fossil fuel combustion, affecting local pollutants in Xiamen’s coastal area [

38]. As the northeast wind strengthened, the concentration of PM

2.5 also increased [

39], which was consistent with the results of this study.

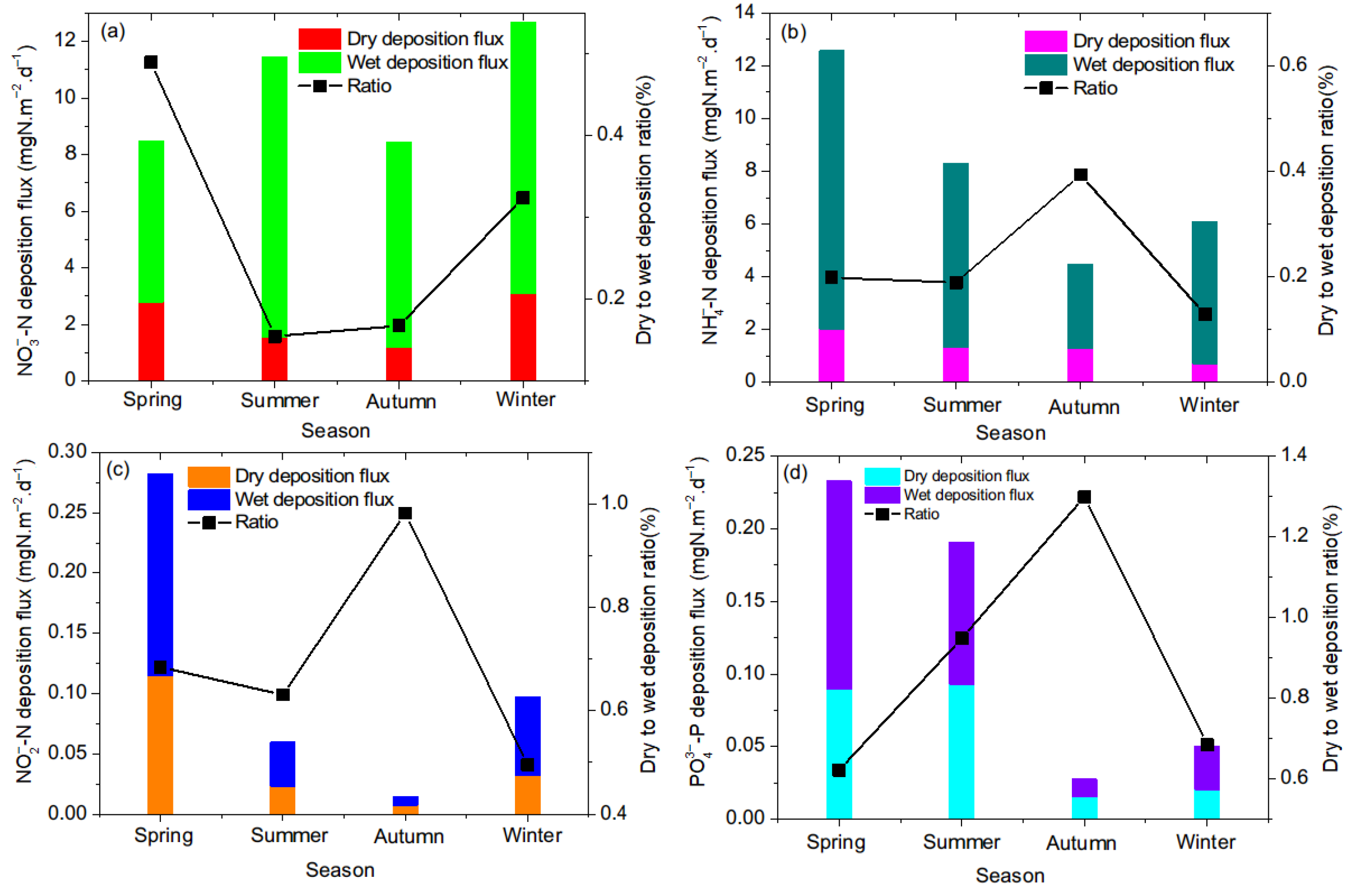

3.3. Dry and Wet Deposition of Nitrogen Fluxes in Coastal Xiamen

Figure 4a illustrates the seasonal variation characteristics of the dry and wet deposition fluxes of NO

3−-N. The wet deposition flux of NO

3−-N was much higher than that of the dry deposition flux. The wet deposition flux peaked in winter and summer, but the dry deposition flux was higher in spring and winter. The dry deposition flux was mainly determined by the pollutant concentration and the deposition velocity, while the wet deposition flux was primarily governed by the pollutant concentration and the amount of precipitation. It was found that the concentration of NO

3−-N in summer precipitation was low, but the wet deposition flux was high in summer due to the large amount of precipitation. The high concentration of atmospheric NO

3−-N led to a relatively high wet deposition flux in winter, though the amount of precipitation was low. The highest ratio of dry to wet deposition flux (about 0.45) was observed in spring, and the lowest values occurred in summer and autumn. This was mainly because of the low NO

3−-N concentration in summer and autumn, resulting in a low dry deposition flux, while heavy rainfall in the summertime increased the wet deposition flux. Similarly to NO

3−-N, the wet deposition flux of NH

4+-N was higher than the dry deposition flux. However, the dry to wet ratio of NH

4+-N was high in autumn but low in winter, as shown in

Figure 4b.

The deposition flux of NO

2−-N and PO

43−-P presented similar distribution characteristics (

Figure 4c,d), exhibiting a relatively high value in spring and summer but a low value in autumn. However, in contrast to NO

3−-N, the ratio of dry to wet deposition for NO

2−-N and PO

43−-P was high in autumn. The seasonal patterns of dry and wet deposition observed in this study were consistent with existing findings [

40]. Nitrate wet deposition through summer precipitation dominated the seasonal peak of wet deposition in the North China Plain, while ammonium wet deposition in winter further confirmed the enhancing effect of precipitation on ammonium scavenging [

38].

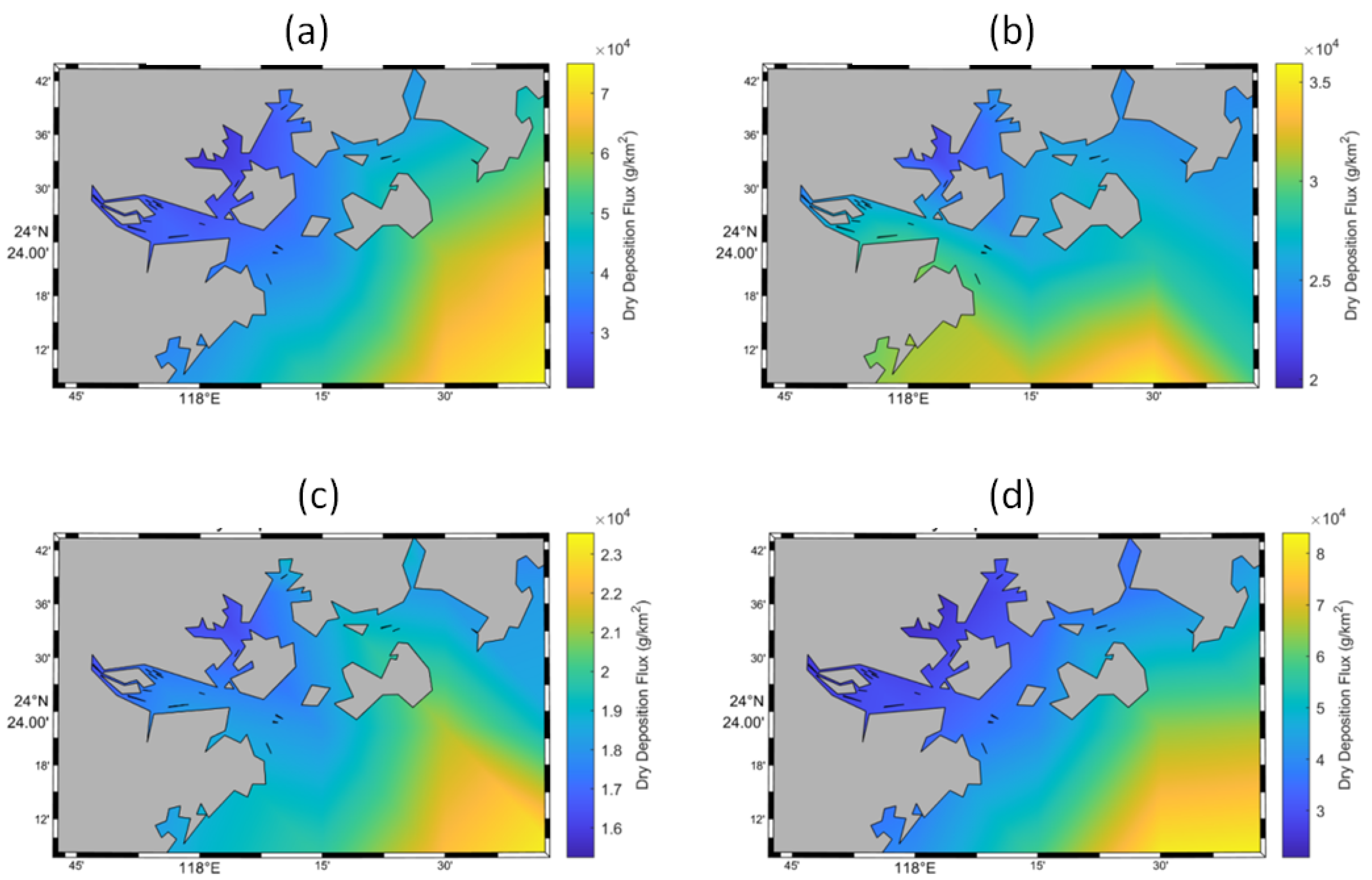

3.4. Spatial Distribution of IN Deposition in the Coastal Area of Xiamen

Figure 5 presents the spatial distribution of inorganic nitrogen (IN) deposition flux in the coastal Xiamen Bay. The IN deposition flux was high in spring and winter but low in summer and autumn. This was mainly related to the distribution of pollutant concentration and the monsoonal climate of Xiamen. During spring and winter, pollutants were transported from northern Xiamen, resulting in an increase in the atmospheric nutrient concentration in the cold season. On the other hand, the wind speed during spring and winter was higher than that in summer and autumn in Xiamen’s coastal area. Both of these factors led to the increase in the atmospheric nitrogen deposition flux.

Additionally, the flux of IN deposition on the sea surface was low in the inner bay and high in the offshore area. This was mainly affected by the sea surface wind speed. The wind speed in the offshore area was higher than that in the inner bay. Generally, atmospheric nitrogen deposition flux is determined by wind speed. The deposition flux increased with increasing wind speed. The simulation results reflected the deposition characteristics of atmospheric nitrogen nutrients in coastal Xiamen well.

The nitrogen deposition flux was consistent with the seasonal variation in deposition velocity. The deposition velocity in Xiamen’s coastal area was high in spring and winter, while the average deposition velocity was low in summer and autumn. The highest deposition velocity was observed in winter, ranging from 0.06 to 0.105 cm·s

−1, and the lowest deposition velocity occurred in autumn, with a value below 0.076 cm·s

−1. In terms of spatial distribution, the deposition velocity in Xiamen’s coastal area was low in the inner bay and high in the offshore area, indicating that atmospheric nitrogen deposition in Xiamen’s coastal area was mainly controlled by the deposition velocity, which was consistent with the observation results from this area [

35].

3.5. Influence of IN Deposition on Water Nutrients in Coastal Xiamen

Atmospheric deposition, as an important external nutrient input pathway, can rapidly affect marine surface water, leading to an increase in nutrient concentration. Nitrate flux has increased by a factor of 3 to 8 times since the early 1900s due to the increase in anthropogenic NO

x emission and nitrogen deposition in the northeastern United States [

41]. The water quality declined in Chesapeake Bay, USA, which was mainly affected by the deposition of atmospheric nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen [

42]. Atmospheric deposition may have increased the surface-dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) concentration by up to 14 mmol·m

−3 in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea of China [

43].

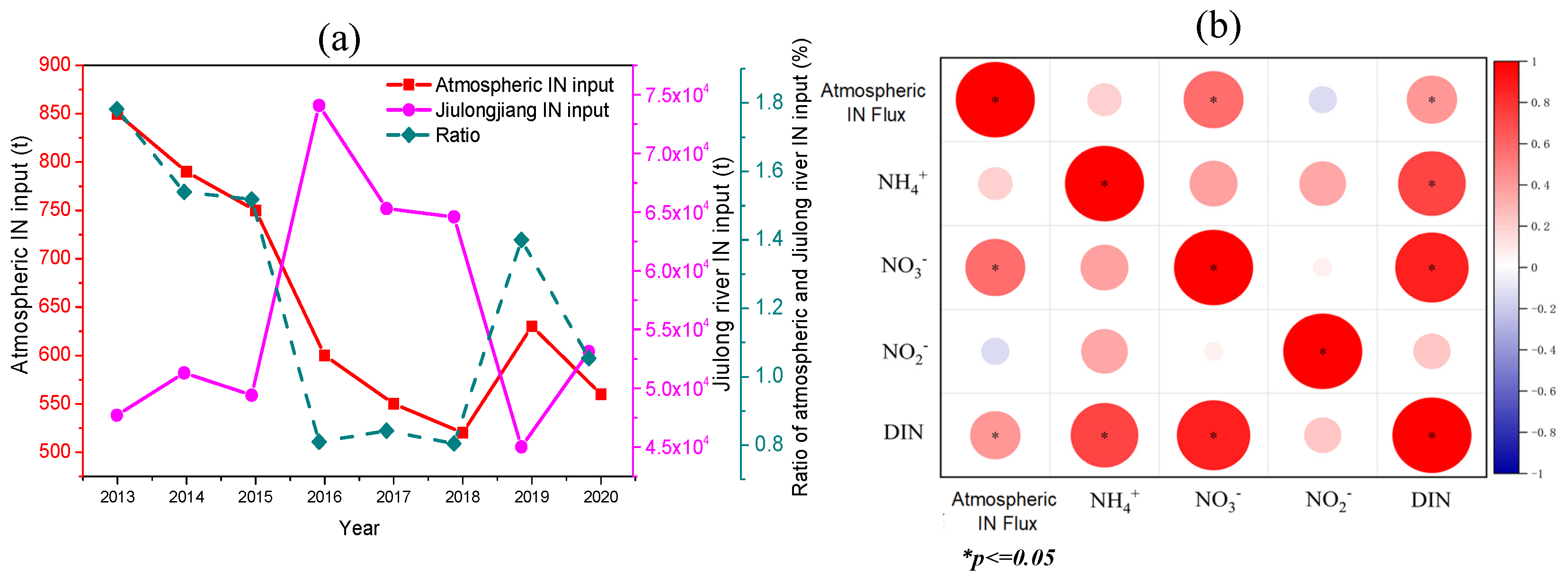

Generally, the nitrogen runoff input to the coastal water of Xiamen is primarily sourced from the Jiulong River. To analyze the contribution of atmospheric nitrogen deposition to the nutrient input in the coastal water of Xiamen,

Figure 6a shows the interannual variation patterns of atmospheric inorganic nitrogen, nitrogen input from the Jiulong River, and nutrients in the coastal water of Xiamen. The annual DIN input from the Jiulong River to Xiamen Bay ranged from 38,300 t to 74,100 t, presenting a trend of an initial fluctuating increase followed by a gradual decrease. In contrast to the DIN input from the Jiulong River, the atmospheric IN input showed an overall fluctuating downward trend, gradually decreasing from about 850 t in 2013 to about 550 t in 2020. This was closely associated with the reduction in atmospheric nitrogen pollutant emissions. The concentration of atmospheric NO

x has decreased gradually since 2014 with the implementation of air pollution control, resulting in a decrease in IN deposition.

The input of atmospheric IN deposition in the coastal water of Xiamen accounted for approximately 0.9% to 1.8% of the IN input to the Jiulong River. Similar results were found in Dalian Bay, which showed that dry and wet IN deposition accounted for 1.9% of the total IN input [

44]. But atmospheric nitrogen deposition in the South China Sea accounted for about 20% of the total surface nitrogen input [

45]. The atmospheric nitrogen deposition input in Xiamen Bay was relatively low, compared with the nitrogen input in other regions of China. The input of atmospheric IN deposition in coastal water was determined by the deposition flux and the sea surface area. In this study, the IN deposition amount was calculated only in the Xiamen Bay. Hence, the contribution of atmospheric nitrogen deposition was low in the coastal water of Xiamen.

Figure 6b shows the correlation between the nitrogen nutrient concentration in the water of Xiamen Bay and the atmospheric nitrogen deposition flux. The NO

3− concentration in the Xiamen coastal water was significantly positively correlated with the atmospheric dry nitrogen deposition flux (

p < 0.05), while there was little correlation between nitrogen dry deposition flux and the DIN, NH

4+, and NO

2− concentrations in the seawater. This indicates that the water NO

3− concentration in Xiamen Bay was affected by atmospheric nitrogen deposition. Similar results were found in previous studies, which showed that there was a significant positive correlation between DIN in the Ganges River and NO

3− in atmospheric deposition [

46]. The ratio of atmospheric nitrogen deposition input to the inorganic nitrogen input from the Jiulong River in the coastal water of Xiamen Bay was relatively low; however, NO

3− in the coastal water of Xiamen still showed a significant correlation with atmospheric NO

3− deposition. This was primarily due to the fact that the atmospheric deposition input bypassed the estuarine filtration effect and influenced the surface water directly, directly impacting water nutrients. Therefore, the impact of atmospheric nitrogen deposition input still needs to be emphasized.

4. Conclusions

The seasonal variation in atmospheric inorganic nitrogen deposition was investigated in Xiamen’s coastal area. NH4+-N and NO3−-N were the major compositions of the inorganic nitrogen species. The highest NH4+-N concentration was observed in the spring (approximately 1100 ng·m−3), which gradually decreased to approximately 300 ng·m−3 in winter. In contrast, the NO3−-N concentration was higher in winter and spring (1800 ng·m−3 and 1600 ng·m−3, respectively) and lower in the warm season.

The wet deposition fluxes of NH4+-N and NO3−-N were significantly higher than their dry deposition fluxes. The wet deposition flux of NO3−-N peaked in winter and summer, while the dry deposition flux was higher in spring and winter. The wet deposition flux of NH4+-N was also high in winter and summer. Source apportionment indicated that NH4+-N mainly originated from agricultural sources, contributing over 45% during the warm season and 35% during the cold season, whereas NO3−-N was primarily derived from traffic sources (24%), secondary sources (25%), and coal combustion sources (28%). Spatially, the inorganic nitrogen deposition flux was low in the inner bay and high in the offshore area, which was associated with the higher sea surface wind speed in the offshore region than in the inner bay.

The NO3− concentration in Xiamen Bay showed a significant positive correlation with the dry deposition flux of atmospheric nitrogen (p < 0.05). The input of atmospheric inorganic nitrogen accounted for only 0.9% to 1.8% of the inorganic nitrogen input from the Jiulong River into Xiamen Bay; however, atmospheric nitrogen deposition directly influenced coastal water nutrients through bypassing the estuarine filtration effect and acting directly on the surface water. This work provided valuable insight into atmospheric inorganic nitrogen deposition in Xiamen’s coastal area and its ecological implications; however, the mechanism of atmospheric nitrogen deposition in the coastal water of Xiamen is complex, and the sources and influencing factors remain unclear. Long-term observations are needed to further understand the trend of nitrogen deposition and its potential cumulative impacts on Xiamen Bay’s ecosystem.