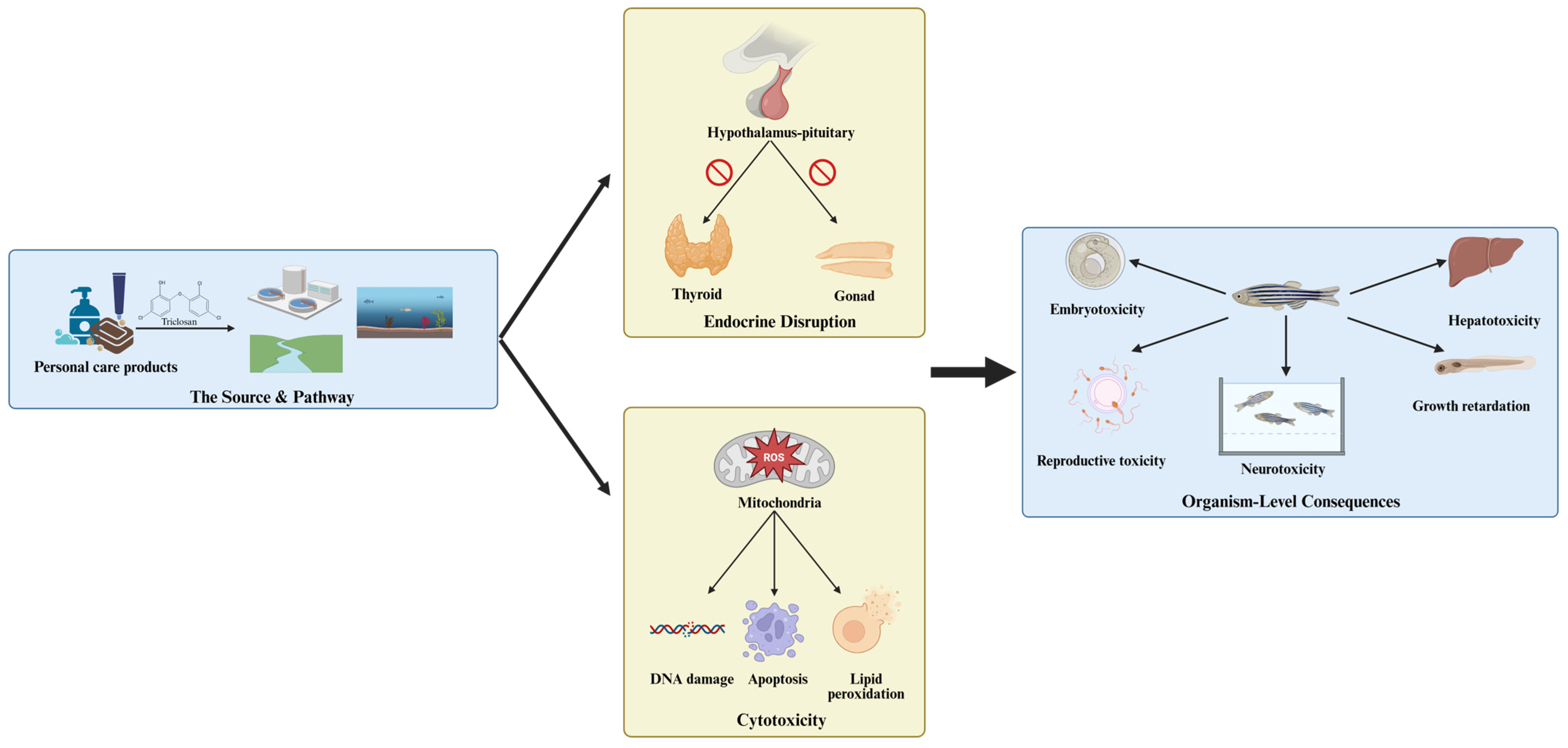

Hazards and Health Risks of the Antibacterial Agent Triclosan to Fish: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

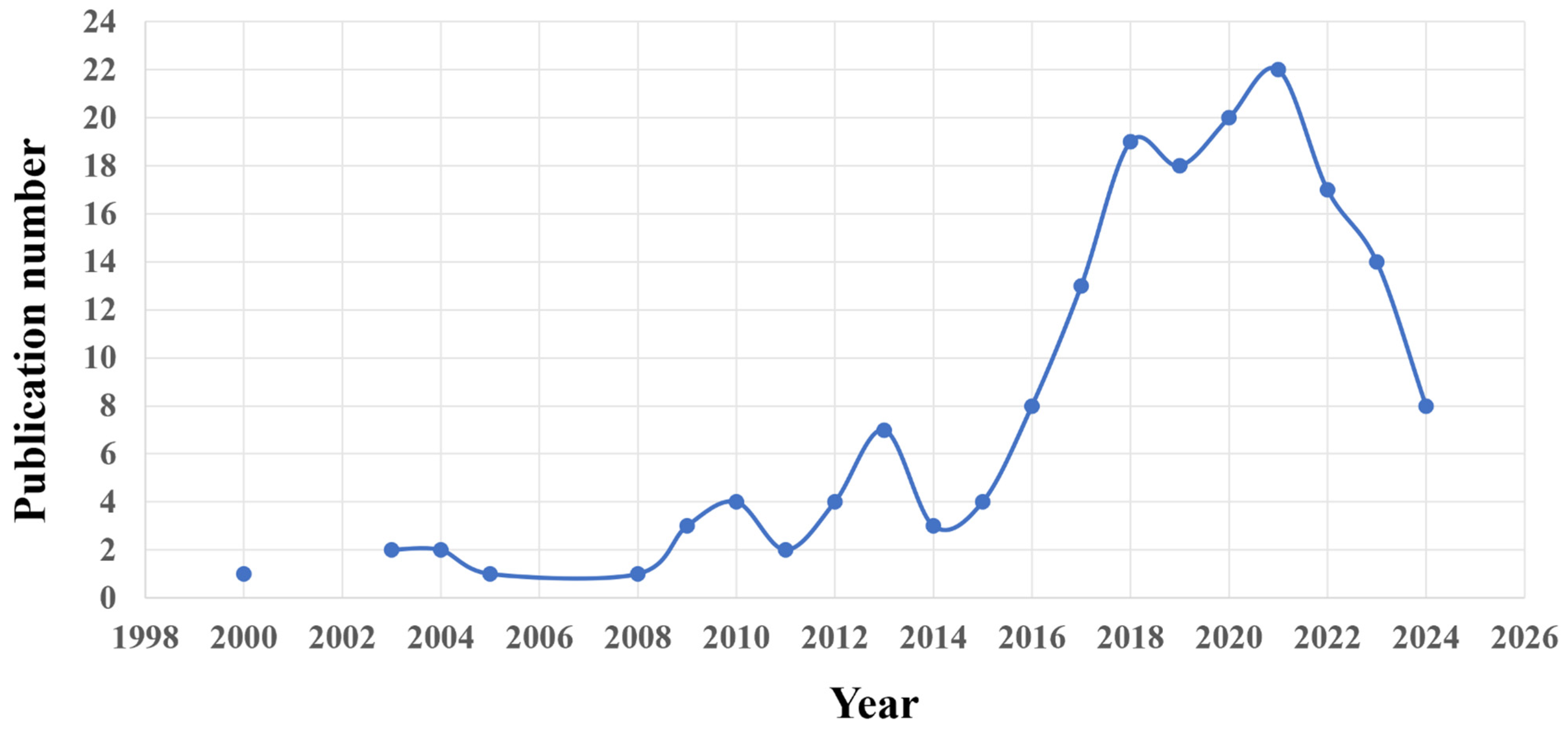

2. Methods

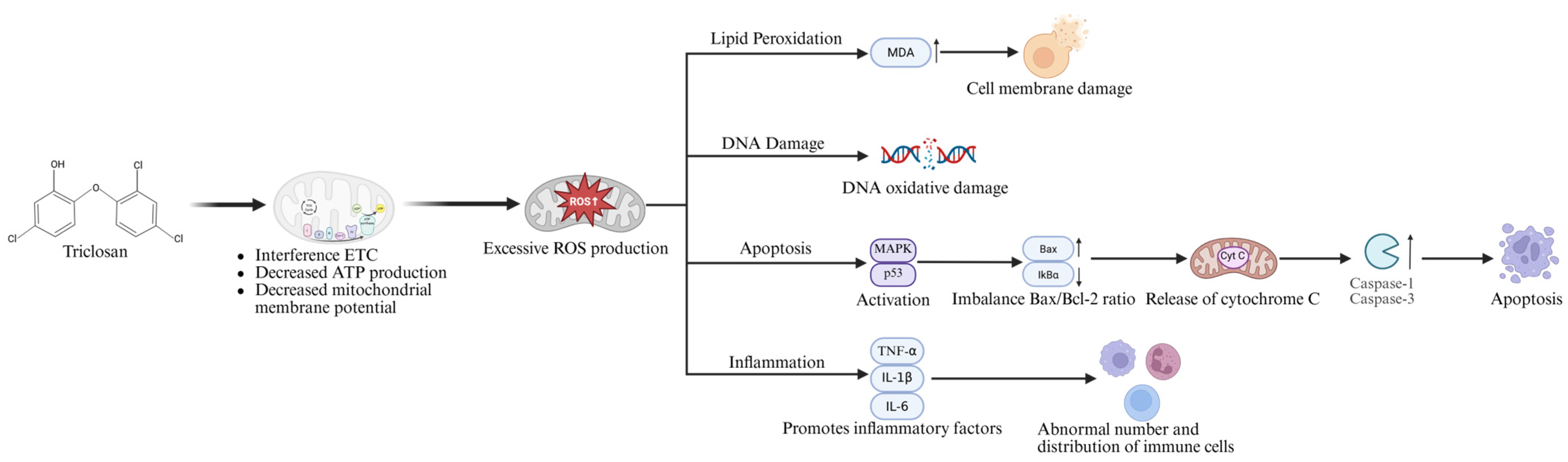

3. Metabolism and Cytotoxicity of Triclosan

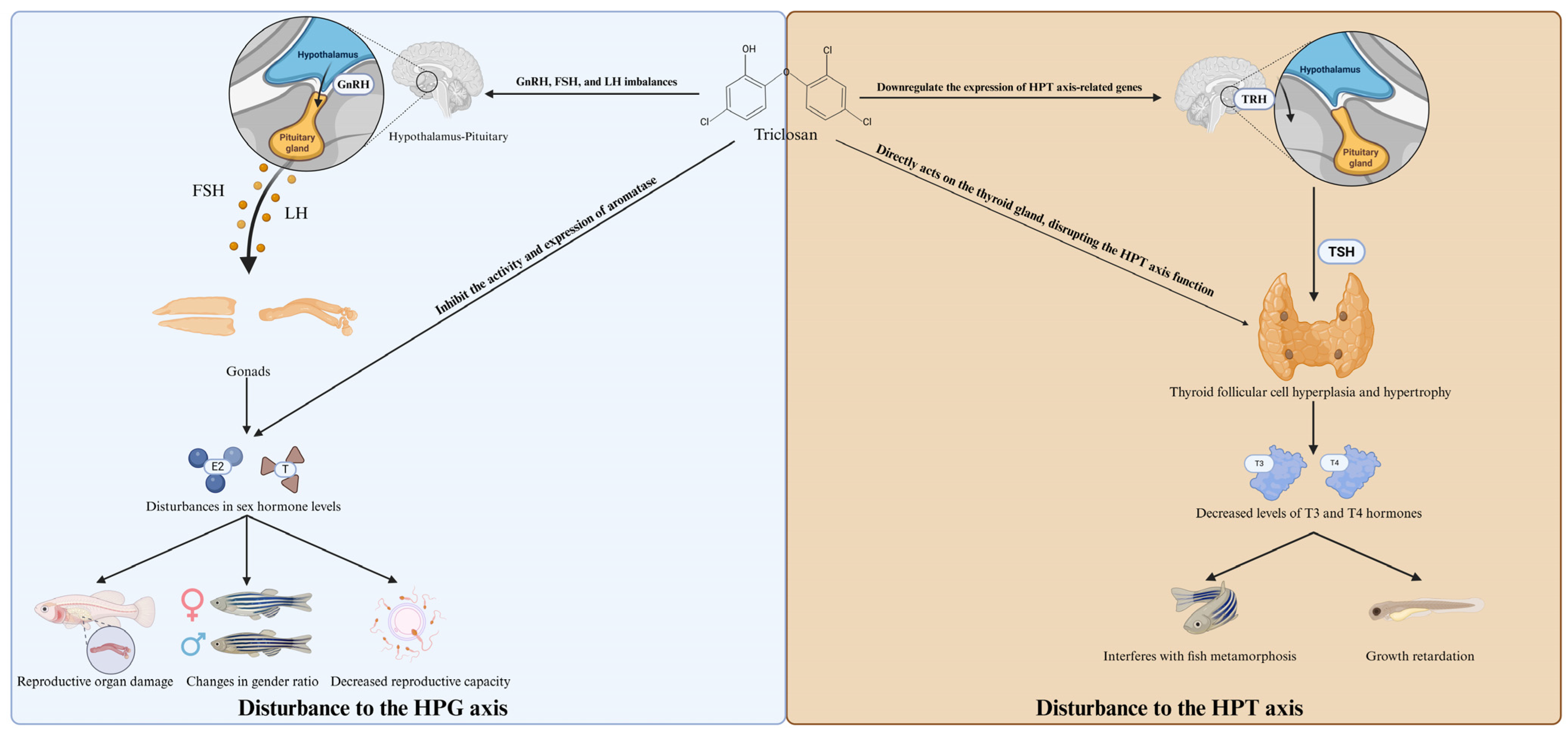

4. Embryonic Development

4.1. Embryotoxicity

4.2. Developmental Toxicity

5. Reproductive Toxicity

6. Neurotoxicity

7. Hepatotoxicity

8. Summary and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Narrowe, A.B.; Albuthi-Lantz, M.; Smith, E.P.; Bower, K.J.; Roane, T.M.; Vajda, A.M.; Miller, C.S. Perturbation and restoration of the fathead minnow gut microbiome after low-level triclosan exposure. Microbiome 2015, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, D.; Nataraj, B.; Rangasamy, B.; Shobana, C.; Ramesh, M. DNA damage and physiological responses in an Indian major carp Labeo rohita exposed to an antimicrobial agent triclosan. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 45, 1463–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, D.; Rangasamy, B.; Nataraj, B.; Ramesh, M. Assessment of triclosan impact on enzymatic biomarkers in an Indian major carp, Catla catla. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2019, 80, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mou, L.; Qu, J.; Wu, L.; Liu, C. Adverse effects of triclosan exposure on health and potential molecular mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 879, 163068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Niu, X.; Chen, G.; An, T. Toxicity evolution of triclosan during environmental transformation and human metabolism: Misgivings in the post-pandemic era. Environ. Int. 2024, 190, 108927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, J.; Ni, A.; Fang, L.; Xi, M.; Qian, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H. Deciphering the molecular mediators of triclosan-induced lipid accumulation: Intervention via short-chain fatty acids and miR-101a. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhou, X.; Yang, J.H.; Zhao, J.L.; Chen, Z.Y. Uptake, tissue distribution, and biotransformation pattern of triclosan in tilapia exposed to environmentally-relevant concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Ming, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xi, Y.; Weihua, X.; Yunguo, L.; Tang, Y. Technology and principle of removing triclosan from aqueous media: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 378, 122185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, O.I.; Aslam, R.; Pan, D.; Sharma, S.; Andotra, M.; Kaur, A.; Faggio, C. Source, bioaccumulation, degradability and toxicity of triclosan in aquatic environments: A review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 25, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Guo, Y.; Luo, D.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Z. Tradeoffs between hygiene behaviors and triclosan loads from rivers to coastal seas in the post COVID-19 era. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 203, 116507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wang, H.; Qian, Q.; Yan, J. MiR-133b as a crucial regulator of TCS-induced cardiotoxicity via activating β-adrenergic receptor signaling pathway in zebrafish embryos. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 334, 122199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, R.; Domingues, I.; Koppe Grisolia, C.; Soares, A.M. Effects of triclosan on zebrafish early-life stages and adults. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2009, 16, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Ai, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Toxicity mechanisms regulating bone differentiation and development defects following abnormal expressions of miR-30c targeted by triclosan in zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 158040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokki Veettil, P.; Nikarthil Sidhick, J.; Kavungal Abdulkhader, S.; Ms, S.P.; Kumari Chidambaran, C. Triclosan, an antimicrobial drug, induced reproductive impairment in the freshwater fish, Anabas testudineus (Bloch, 1792). Toxicol. Ind. Health 2024, 40, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fang, L.; Xi, M.; Ni, A.; Qian, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yan, J. Toxic effects of triclosan on hepatic and intestinal lipid accumulation in zebrafish via regulation of m6A-RNA methylation. Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 269, 106884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Reproductive endocrine disruption effect and mechanism in male zebrafish after life cycle exposure to environmental relevant triclosan. Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 270, 106899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, O.I.; Vinothkanna, A.; Aslam, B.; Furkh, A.; Sharma, S.; Kaur, A.; Gao, Y.-A.; Jia, A.Q. Dynamic alterations in physiological and biochemical indicators of Cirrhinus mrigala hatchlings: A sublethal exposure of triclosan. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, F. Mechanism-based understanding of the potential cellular targets of triclosan in zebrafish larvae. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 102, 104255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Hamilton, C.; Hobbs, J.; Miller, E.; Sutton, R. Triclosan and methyl triclosan in prey fish in a wastewater-influenced estuary. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2023, 42, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, Y. Environmentally relevant concentrations of triclosan induce lethality and disrupt thyroid hormone activity in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 100, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Liu, F. Analysis of the effect of triclosan on gonadal differentiation of zebrafish based on metabolome. Chemosphere 2023, 331, 138856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yuan, T.; Li, J.; Shen, Z.; Tian, Y. Occurrence, health risk assessment and water quality criteria derivation of six personal care products (PCPs) in Huangpu River, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; He, J.; Han, P.; Qu, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. Long-term exposure to environmental relevant triclosan induces reproductive toxicity on adult zebrafish and its potential mechanism. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, C.M.; Bhat, K.; Ramaswamy, B.R.; Kumar, V.; Singhal, R.K.; Basu, H.; Udayashankar, H.N.; Vasantharaju, S.G.; Praveenkumarreddy, Y.; Shailesh; et al. Seasonal occurrence and risk assessment of pharmaceutical and personal care products in Bengaluru rivers and lakes, India. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Dar, O.I.; Singh, K.; Thakur, S.; Kesavan, A.K.; Kaur, A. Genomic markers for the biological responses of Triclosan stressed hatchlings of Labeo rohita. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 67370–67384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; He, C.; Ku, P.; Xie, M.; Lin, J.; Lu, S.; Nie, X. Effects of triclosan on the RedoximiRs/Sirtuin/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway in mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis). Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 230, 105679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Sarkar, S.; Nag, S.K.; Kumari, K.; Saha, K.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Aftabuddin, M.; Das, B.K. Occurrence and safety evaluation of antimicrobial compounds triclosan and triclocarban in water and fishes of the multitrophic niche of River Torsa, India. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2020, 79, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaniyan, L.W.; Okoh, A.I. Determination and ecological risk assessment of two endocrine disruptors from River Buffalo, South Africa. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juksu, K.; Zhao, J.L.; Liu, Y.S.; Yao, L.; Sarin, C.; Sreesai, S.; Klomjek, P.; Jiang, Y.-X.; Ying, G.G. Occurrence, fate and risk assessment of biocides in wastewater treatment plants and aquatic environments in Thailand. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 1110–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, F.; Chen, W.; Xu, R.; Wang, W. Effects of triclosan (TCS) on hormonal balance and genes of hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis of juvenile male Yellow River carp (Cyprinus carpio). Chemosphere 2018, 193, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.C.; Araújo, C.V.; López-Doval, J.C.; Neto, M.B.; Silva, F.T.; Paiva, T.C.; Pompêo, M.L. Potential effects of triclosan on spatial displacement and local population decline of the fish Poecilia reticulata using a non-forced system. Chemosphere 2017, 184, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.C.; Hsiao, C.D.; Kawakami, K.; William, K.F. Triclosan (TCS) exposure impairs lipid metabolism in zebrafish embryos. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016, 173, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, G. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals in Water, Sediments and Fish Observed in Urban Tributaries of the Freshwater Tidal Potomac River: Occurrence, Bioaccumulation and Tissue Distribution. Ph.D. Thesis, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Inam, E.; Offiong, N.A.; Kang, S.; Yang, P.; Essien, J. Assessment of the occurrence and risks of emerging organic pollutants (EOPs) in Ikpa River Basin freshwater ecosystem, Niger Delta-Nigeria. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2015, 95, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick-Hopper, T.L.; Koster, L.P.; Diamond, S.L. Accumulation of triclosan from diet and its neuroendocrine effects in Atlantic croaker (Micropogonias undulatus) under two temperature regimes. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 112, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, S.; Torres, T.; Santos, M.M. Methyl-triclosan and triclosan impact embryonic development of Danio rerio and Paracentrotus lividus. Ecotoxicology 2017, 26, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Dar, O.I.; Thakur, S.; Kesavan, A.K.; Kaur, A. Environmentally relevant concentrations of triclosan cause transcriptomic and biomolecular alterations in the hatchlings of Labeo rohita. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 96, 104004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantal, D.; Kumar, S.; Shukla, S.P.; Karmakar, S.; Jha, A.K.; Singh, A.B.; Kumar, K. Chronic toxicity of sediment-bound triclosan on freshwater walking catfish Clarias magur: Organ level accumulation and selected enzyme biomarker responses. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 351, 124108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boreen, A.L.; Arnold, W.A.; McNeill, K. Photodegradation of pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment: A review. Aquat. Sci. 2003, 65, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latch, D.E.; Packer, J.L.; Stender, B.L.; VanOverbeke, J.; Arnold, W.A.; McNeill, K. Aqueous photochemistry of triclosan: Formation of 2,4-dichlorophenol, 2,8-dichlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, and oligomerization products. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2005, 24, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greim, L.W.W.H. The toxicity of brominated and mixed-halogenated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans: An overview. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 1997, 50, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, K.; Chang, Y.Y.; Kim, Y.M.; Jeon, J.R.; Kim, E.J.; Chang, Y.S. Enhanced transformation of triclosan by laccase in the presence of redox mediators. Water Res. 2010, 44, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundt, K.A.I.; Martin, D.; Hammer, E.; Jonas, U.; Kindermann, M.K.; Schauer, F. Transformation of triclosan by Trametes versicolor and Pycnoporus cinnabarinus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 4157–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, P.; Mohan, S. Treatment of triclosan through enhanced microbial biodegradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, O.I.; Sharma, S.; Singh, K.; Sharma, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Kaur, A. Biochemical markers for prolongation of the acute stress of triclosan in the early life stages of four food fishes. Chemosphere 2020, 247, 125914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, O.I.; Sharma, S.; Singh, K.; Sharma, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Kaur, A. Biomarkers for the toxicity of sublethal concentrations of triclosan to the early life stages of carps. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaiber, M.; Moreno-Gordaliza, E.; Gómez-Gómez, M.M.; Marazuela, M.D. Human intake assessment of triclosan associated with the daily use of polypropylene-made antimicrobial food packaging. Food Chem. 2024, 451, 139475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.K.; Clifton, M.S. Dietary exposures and intake doses to bisphenol A and triclosan in 188 duplicate-single solid food items consumed by US adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lu, S. A holistic review on triclosan and triclocarban exposure: Epidemiological outcomes, antibiotic resistance, and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 872, 162114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Xie, R.; Qian, Q.; Yan, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Triclosan induced zebrafish immunotoxicity by targeting miR-19a and its gene socs3b to activate IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Yan, X.; Liang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L.; Zeng, H. Histopathology and transcriptome reveals the tissue-specific hepatotoxicity and gills injury in mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) induced by sublethal concentration of triclosan. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 220, 112325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimoh, R.O.; Sogbanmu, T.O. Sublethal and environmentally relevant concentrations of triclosan and triclocarban induce histological, genotoxic, and embryotoxic effects in Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 31071–31083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Liang, S.X. Parabens, triclosan and bisphenol A in surface waters and sediments of Baiyang Lake, China: Occurrence, distribution, and potential risk assessment. Toxics 2023, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaich, E.; Capdevielle, M.; Urbach-Ross, D.; Gallagher, S.; Wolf, J. Medaka (Oryzias latipes) multigeneration test with triclosan. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2019, 38, 1770–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saemi-Komsari, M.; Pashaei, R.; Abbasi, S.; Esmaeili, H.R.; Dzingelevičienė, R.; Hadavand, B.S.; Kalako, M.P.; Szultka-Mlynska, M.; Gadzała-Kopciuch, R.; Buszewski, B.; et al. Accumulation of polystyrene nanoplastics and triclosan by a model tooth-carp fish, Aphaniops hormuzensis (Teleostei: Aphaniidae). Environ. Pollut. 2023, 333, 121997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Guo, X.; Chen, W.; Sun, Y.; Fan, C. Effects of triclosan on hormones and reproductive axis in female Yellow River carp (Cyprinus carpio): Potential mechanisms underlying estrogen effect. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2017, 336, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.N.; Liu, Z.T.; Yan, Z.G.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.L.; Zhou, J.L.; Pei, S.W. Development of aquatic life criteria for triclosan and comparison of the sensitivity between native and non-native species. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 260, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Das, B.K.; Ganguly, S.; Nag, S.K.; Sadhukhan, D.; Raut, S.S. Emerging contaminant triclosan incites endocrine disruption, reproductive impairments and oxidative stress in the commercially important carp, Catla (Labeo catla): An insight through molecular, histopathological and bioinformatic approach. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 268, 109605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, M.; Gölz, L.; Rinderknecht, M.; Koegst, J.; Braunbeck, T.; Baumann, L. Developmental exposure to triclosan and benzophenone-2 causes morphological alterations in zebrafish (Danio rerio) thyroid follicles and eyes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 33711–33724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullaguri, N.; Nema, S.; Bhargava, Y.; Bhargava, A. Triclosan alters adult zebrafish behavior and targets acetylcholinesterase activity and expression. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 75, 103311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullaguri, N.; Grover, P.; Abhishek, S.; Rajakumara, E.; Bhargava, Y.; Bhargava, A. Triclosan affects motor function in zebrafish larva by inhibiting ache and syn2a genes. Chemosphere 2021, 266, 128930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Zhang, R.; Huang, H.; Lu, C.; Xia, Y.; Wang, X.; Du, G. Exploration of the developmental toxicity of TCS and PFOS to zebrafish embryos by whole-genome gene expression analyses. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 56032–56042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Chen, Q.; Di Paolo, C.; Shao, Y.; Hollert, H.; Seiler, T.B. Behavioral profile alterations in zebrafish larvae exposed to environmentally relevant concentrations of eight priority pharmaceuticals. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 664, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Shi, M.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Response mechanisms to joint exposure of triclosan and its chlorinated derivatives on zebrafish (Danio rerio) behavior. Chemosphere 2018, 193, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiang, C.; Huang, W.; Mei, J.; Sun, L.; Ling, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Wang, H. Neurotoxicological effects induced by up-regulation of miR-137 following triclosan exposure to zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquat. Toxicol. 2019, 206, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Fan, P.; Chen, L.; Yu, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, W.; Ouyang, F. The effect of early life exposure to triclosan on thyroid follicles and hormone levels in zebrafish. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 850231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Differential immunotoxicity effects of triclosan and triclocarban on larval zebrafish based on RNA-Seq and bioinformatics analysis. Aquat. Toxicol. 2023, 262, 106665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.; Pu, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Ni, A.; Han, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Yan, J.; Wang, H. Acute/chronic triclosan exposure induces downregulation of m6A-RNA methylation modification via mettl3 suppression and elicits developmental and immune toxicity to zebrafish. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimah, E.; Dong, X.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H. Sublethal concentrations of triclosan elicited oxidative stress, DNA damage, and histological alterations in the liver and brain of adult zebrafish. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 17329–17338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, S.; Padmavathy, P.; Srinivasan, A.; Sugumar, G.; Jawahar, P. Effect of triclosan (TCS) on the protein content and associated histological changes on tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters, 1852). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 59899–59907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, E.; Scarcia, P.; Marino, D.; Mac Loughlin, T.; Rossi, A.; de La Torre, F. Oxidative stress responses after exposure to triclosan sublethal concentrations: An integrated biomarker approach with a native (Corydoras paleatus) and a model fish species (Danio rerio). J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 2022, 85, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.F.; de Paula, V.D.C.S.; Martins, L.R.R.; Garcia, J.R.E.; Yamamoto, F.Y.; de Freitas, A.M. Sublethal effects of triclosan and triclocarban at environmental concentrations in silver catfish (Rhamdia quelen) embryos. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 127985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, Y.; Yamagishi, T.; Takahashi, H.; Iguchi, T.; Tatarazako, N. Effects of triclosan on Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) during embryo development, early life stage and reproduction. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2018, 38, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, H.; Matsumura, N.; Hirano, M.; Matsuoka, M.; Shiratsuchi, H.; Ishibashi, Y.; Takao, Y.; Arizono, K. Effects of triclosan on the early life stages and reproduction of medaka Oryzias latipes and induction of hepatic vitellogenin. Aquat. Toxicol. 2004, 67, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falisse, E.; Voisin, A.S.; Silvestre, F. Impacts of triclosan exposure on zebrafish early-life stage: Toxicity and acclimation mechanisms. Aquat. Toxicol. 2017, 189, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Fan, M.; Belanger, S.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Fan, B.; Li, W.; Gao, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z. Oryzias sinensis, a new model organism in the application of eco-toxicity and water quality criteria (WQC). Chemosphere 2020, 261, 127813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, T.; Shukla, S.P.; Kumar, K.; Poojary, N.; Kumar, S. Effect of temperature on triclosan toxicity in Pangasianodon hypophthalmus (Sauvage, 1878): Hematology, biochemistry and genotoxicity evaluation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, T.; Kumar, S.; Shukla, S.P.; Pal, P.; Kumar, K.; Poojary, N.; Biswal, A.; Mishra, A. A multi-biomarker approach using integrated biomarker response to assess the effect of pH on triclosan toxicity in Pangasianodon hypophthalmus (Sauvage, 1878). Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 114001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, V.K.; Karmakar, S.; Kumar, S.; Shukla, S.P.; Kumar, K. Triclosan toxicity alters behavioral and hematological parameters and vital antioxidant and neurological enzymes in Pangasianodon hypophthalmus (Sauvage, 1878). Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 202, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, K.K.; Kumar, S.; Paul, T.; Prasad, K.P.; Shukla, S.P.; Kumar, K. Triclosan induces immunosuppression and reduces survivability of striped catfish Pangasianodon hypophthalmus during the challenge to a fish pathogenic bacterium Edwardsiella tarda. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassef, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Seki, M.; Khalil, F.; Kang, I.J.; Shimasaki, Y.; Oshima, Y.; Honjo, T. Acute effects of triclosan, diclofenac and carbamazepine on feeding performance of Japanese medaka fish (Oryzias latipes). Chemosphere 2010, 80, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escarrone, A.L.V.; Caldas, S.S.; Primel, E.G.; Martins, S.E.; Nery, L.E.M. Uptake, tissue distribution and depuration of triclosan in the guppy Poecilia vivipara acclimated to freshwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 560, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Nie, X.; Ying, G.; An, T.; Li, K. Assessment of toxic effects of triclosan on the swordtail fish (Xiphophorus helleri) by a multi-biomarker approach. Chemosphere 2013, 90, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannetta, A.; Caioni, G.; Di Vito, V.; Benedetti, E.; Perugini, M.; Merola, C. Developmental toxicity induced by triclosan exposure in zebrafish embryos. Birth Defects Res. 2022, 114, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Paul, T.; Shukla, S.P.; Kumar, K.; Karmakar, S.; Bera, K.K. Biomarkers-based assessment of triclosan toxicity in aquatic environment: A mechanistic review. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 286, 117569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.J.; Quintaneiro, C.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Monteiro, M.S. Effects of triclosan on early development of Solea senegalensis: From biochemical to individual level. Chemosphere 2019, 235, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, W.; Tong, D.; Lu, L.; Zhou, W.; Tian, D.; Liu, G.; Shi, W. Triclosan and triclocarban weaken the olfactory capacity of goldfish by constraining odorant recognition, disrupting olfactory signal transduction, and disturbing olfactory information processing. Water Res. 2023, 233, 119736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F. Environmental relevant concentrations of triclosan affected developmental toxicity, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in zebrafish embryos. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbulut, C. Histopathological and apoptotic examination of zebrafish (Danio rerio) gonads exposed to triclosan. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2021, 73, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ai, W.; Sun, L.; Fang, F.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, H. Triclosan-induced liver injury in zebrafish (Danio rerio) via regulating MAPK/p53 signaling pathway. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 222, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidony, N.S.; Scaini, J.L.R.; Oliveira, M.W.B.; Machado, K.S.; Bastos, C.; Escarrone, A.L.; Souza, M.M. ABC proteins activity and cytotoxicity in zebrafish hepatocytes exposed to triclosan. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 271, 116368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, J.; Wang, X.; Qian, Q.; Wang, H. Study on the toxic-mechanism of triclosan chronic exposure to zebrafish (Danio rerio) based on gut-brain axis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 156936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, W.; Qian, Q.; Sheng, G.; He, A.; Yan, J.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Triclosan targets miR-144 abnormal expression to induce neurodevelopmental toxicity mediated by activating PKC/MAPK signaling pathway. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 431, 128560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parenti, C.C.; Ghilardi, A.; Della Torre, C.; Mandelli, M.; Magni, S.; Del Giacco, L.; Binelli, A. Environmental concentrations of triclosan activate cellular defence mechanism and generate cytotoxicity on zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1752–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Dar, O.I.; Singh, K.; Kaur, A.; Faggio, C. Triclosan elicited biochemical and transcriptomic alterations in Labeo rohita larvae. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 88, 103748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Ling, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Differential mechanisms regarding triclosan vs. bisphenol A and fluorene-9-bisphenol induced zebrafish lipid-metabolism disorders by RNA-Seq. Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, X.; Bhandari, R.K. Developmental abnormalities and epigenetic alterations in medaka (Oryzias latipes) embryos induced by triclosan exposure. Chemosphere 2020, 261, 127613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Bae, S. The pH-dependent toxicity of triclosan on developing zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos using metabolomics. Aquat. Toxicol. 2020, 226, 105560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebi, H.; Gök, O. Effect of triclosan exposure on mortality and behavioral changes of Poecilia reticulata and Danio rerio. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2018, 24, 1327–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Wang, X.; Huang, H.; Wang, H. Risk assessment of cardiotoxicity to zebrafish (Danio rerio) by environmental exposure to triclosan and its derivatives. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 114995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, S.A.; Angus, R.A. Triclosan has endocrine-disrupting effects in male western mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 1287–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, P.I.; Guerreiro, E.M.; Power, D.M. Triclosan interferes with the thyroid axis in the zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxicol. Res. 2013, 2, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, J.G.; Frederich, B.; Dussenne, M.; Klaren, P.H.; Silvestre, F.; Das, K. Triclosan exposure results in alterations of thyroid hormone status and retarded early development and metamorphosis in Cyprinodon variegatus. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016, 181, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.J.; Quintaneiro, C.; Rocha, R.J.; Pousão-Ferreira, P.; Candeias-Mendes, A.; Soares, A.M.; Monteiro, M.S. Single and combined effects of ultraviolet radiation and triclosan during the metamorphosis of Solea senegalensis. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, E.M. Thyroid Axis Disruption by Goitrogens: A Molecular and Functional Approach. Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Gong, Z.; Kelly, B.C. Metabolomic profiling of zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos exposed to the antibacterial agent triclosan. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2019, 38, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Tan, Y.X.R.; Gong, Z.; Bae, S. The toxic effect of triclosan and methyl-triclosan on biological pathways revealed by metabolomics and gene expression in zebrafish embryos. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 189, 110039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, W.; Yan, J.; Wang, X.; Qian, Q.; Wang, H. Mechanisms regarding cardiac toxicity triggered by up-regulation of miR-144 in larval zebrafish upon exposure to triclosan. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, X.; Qian, Q.; Yan, J.; Huang, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Mechanistic exploration on neurodevelopmental toxicity induced by upregulation of alkbh5 targeted by triclosan exposure to larval zebrafish. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 457, 131831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, D.; Jiang, J.; Sun, W.; Ai, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Triclosan induces zebrafish neurotoxicity by abnormal expression of miR-219 targeting oligodendrocyte differentiation of central nervous system. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Location | Matrix | Concentration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Six lakes and Nag River, Nagpur, India | Water | 74.3 μg/L | [16] |

| Gomati River, South India | Water | 1.1–9.65 μg/L (Maximum: 9.56 μg/L) | [17,18] |

| Freshwater lake, Yangtze River Basin, Central China | Water | 0.47 μg/L | [17] |

| Baiyangdian Lake, China | Water | 26.1 ng/L | [19] |

| Laizhou Bay, China | Water | 58.3 ng/L | [20] |

| Bouregreg River, Rabat, Morocco | Water | 48–301 ng/L | [20] |

| Yangtze River, China | Water | 1.0–20.6 ng/L | [20] |

| Yamuna River, India | Water | 269.8 ± 1.0 ng/L | [20] |

| Lake Victoria, Uganda | Water | 89–1400 ng/L | [20] |

| Tamiraparani River, India | Water | Up to 5.2 μg/L | [21] |

| Huangpu River, China | Water | 1.48–89.76 ng/L | [22] |

| Shanghai, China | Water | 533–774 ng/L | [23] |

| Benedict River and lakes, India | Water | 297–1761 ng/L | [24] |

| Tamiraparani River, India | Water | 0.944 μg/L | [25] |

| Kaveri and Vellar Rivers, India | Water | 3.8–5.16 μg/L | [25] |

| Xiaoqing River, China | Water | Up to 245 ng/L | [26] |

| Torsa River, India | Water | 0.055–0.184 μg/L | [27] |

| Buffalo River, Eastern Cape, South Africa | Water | 0–1264.2 ng/L | [28] |

| Estuarine system, Bangkok, Thailand | Water | Up to 185 ng/L | [29] |

| Freshwater, Switzerland | Water | 18–98 ng/L | [2] |

| Yellow River, China | Water | Up to 64.7 ng/L | [30] |

| Atibaia River, São Paulo, Brazil | Water | Up to 0.34 mg/L | [31] |

| Paraíba do Sul River, São Paulo, Brazil | Water | Up to 0.78 mg/L | [31] |

| Pearl River Delta, South China | Water | 1 μg/L | [32] |

| Campredo Lake, Spain | Water | 0.285 μg/L | [32] |

| Hunting Creek, USA | Water | 15.5 ± 3.71 ng/L | [33] |

| Ikpa River Basin, Nigeria | Water | 55.1–297.7 ng/L | [34] |

| Jiulong River and estuary, China | Water | 64 ng/L | [35] |

| Ton Canal, Japan | Water | 134 ng/L | [35] |

| Ems estuary, Germany | Surface water | 0.012–0.11 ng/L | [35] |

| Weser estuary, Germany | Surface water | 0.018–0.620 ng/L | [35] |

| Elbe estuary, Germany | Surface water | 1.20–6.87 ng/L | [35] |

| Vellar River, India | Surface water | Up to 516 μg/L | [36] |

| Tamiraparani River, Tamil Nadu, India | Surface water | Mean: 944 ng/L; Maximum: 5160 ng/L | [14] |

| United States | Surface water | 250–850 ng/L | [18] |

| England | Surface water | 58 μg/L | [20] |

| Guangzhou, China | Tap water | 14.5 ng/L | [26] |

| Hunting Creek, USA | Sediment | 72.5 ± 9.41 ng/g (d.w.) | [33] |

| Estuarine system, Bangkok, Thailand | Sediment | 242 ng/g | [29] |

| Valiyar estuary, India | Sediment | 132–3073 μg/kg | [25] |

| Baiyangdian Lake, China | Sediment | 32.5 ng/g | [19] |

| Pearl River, China | Sediment | 1329 μg/kg | [16] |

| Gomati River, South India | Sediment | 5.11–50.36 μg/kg | [37] |

| Valiyar estuary, Tamil Nadu, India | Sediment | 132–3073 ng/kg | [14] |

| Freshwater, Thailand | Sediment | Up to 0.726 mg/kg | [38] |

| Municipal WWTP, Savannah, USA | Effluent | 86.161 μg/L | [23] |

| Test Organism | Exposure Duration | LC50 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aphaniops hormuzensis | 96 h | 0.924 mg/L | [55] |

| Carassius auratus | 96 h | 1111.9 µg/L, 1.839 mg/L | [56,57] |

| Catla catla | 96 h | 0.73 mg/L | [58] |

| Catla catla | 96 h | 0.36 mg/L | [3] |

| Cirrhinus mrigala | 96 h | 0.131 mg/L | [46] |

| Clarias gariepinus | 96 h | 16.04 mg/L | [52] |

| Ctenopharyngodon idella | 96 h | 0.116 mg/L | [46] |

| Cyprinus carpio | 96 h | 0.80 mg/L | [30] |

| Cyprinus carpio | 96 h | 0.80 mg/L | [56] |

| Cyprinus carpio | 96 h | 0.315 mg/L | [46] |

| Zebrafish embryos (Danio rerio) | 120 h | 217 μg/L | [59] |

| Zebrafish embryos (Danio rerio) | 96 h | 267.8 μg/L, 0.608 ± 0.064 mg/L, 420 μg/L | [20,60,61,62] |

| Zebrafish embryos (Danio rerio) | 48 h | 1.50 ± 0.48 mg/L | [63] |

| Juvenile zebrafish (Danio rerio) | 96 h | 510 μg/L, 0.42 mg/L | [64,65,66,67,68] |

| Danio rerio | 96 h | 340 mg/L, 398.9 μg/L | [60,62,66,69] |

| Danio rerio | 32 days | 74.6 μg/L | [20] |

| Gambusia affinis | 96 h | 1.399 mg/L | [51] |

| Labeo rohita | 96 h | 126 μg/L | [25] |

| Labeo rohita | 96 h | 96 μg/L, 0.39 mg/L | [2,20,45] |

| Misgurnus anguillicaudatus | 96 h | 0.045 mg/L | [57] |

| Oreochromis mossambicus | 96 h | 715 μg/L, 740 μg/L | [20,70] |

| Oryzias latipes | 96 h | 1.7 mg/L, 210 mg/L | [71,72] |

| Oryzias latipes | 21 days | 330.6 μg/L | [73] |

| Oryzias latipes | 96 h | 169.78 μg/L, 399 μg/L | [73,74] |

| Oryzias latipes | 96 h | 117.9, 600, 602 µg/L | [73,74] |

| Oryzias latipes | 48 h | 0.352 mg/L | [35] |

| Oryzias latipes | 96 h | 1700 μg/L | [75] |

| Oryzias melastigma | - | 300 μg/L | [20] |

| Oryzias sinensis | 96 h | 0.63 mg/L | [76] |

| Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | 96 h | 848.33 μg/L (25 °C) 1181.94 μg/L (30 °C) 1356.96 μg/L (35 °C) | [77] |

| Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | 96 h | 910 mg/L (pH 6.5) 1110 mg/L (pH 7.5) 1380 mg/L (pH 8.5) | [78] |

| Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | 96 h | 1458 μg/L | [79] |

| Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | 96 h | 1177 μg/L | [80] |

| Pimephales promelas | 96 h | 260 μg/L | [75,81] |

| Poecilia vivipara | 96 h | 0.6 mg/L | [82] |

| Pseudorasbora parva | 96 h | 0.071 mg/L | [57] |

| Tanichthys albonubes | 96 h | 0.889 mg/L | [57] |

| Xiphophorus helleri | 96 h | 1.47 mg/L | [83] |

| Lepomis macrochirus | 96 h | 370 µg/L | [81] |

| Test Organism | Exposure Duration | NOEC | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos | 96 h | 200 μg/L | [84] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos | 144 h | 160 μg/L | [19] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos | 144 h | 160 μg/L | [36] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | 9 days | 26 μg/L | [20] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | 32 days | 48.4 μg/L | [20] |

| Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | 35 days | 71.3 μg/L | [20] |

| Medaka (Oryzias latipes) | 182 days | 11 μg/L | [54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Ma, N.; Mo, G.; Qin, X.; Zhang, J.; Yao, X.; Guo, J.; Sun, Z. Hazards and Health Risks of the Antibacterial Agent Triclosan to Fish: A Review. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060204

Wang J, Ma N, Mo G, Qin X, Zhang J, Yao X, Guo J, Sun Z. Hazards and Health Risks of the Antibacterial Agent Triclosan to Fish: A Review. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2025; 15(6):204. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060204

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiangang, Nannan Ma, Gancong Mo, Xian Qin, Jin Zhang, Xiangping Yao, Jiahua Guo, and Zewei Sun. 2025. "Hazards and Health Risks of the Antibacterial Agent Triclosan to Fish: A Review" Journal of Xenobiotics 15, no. 6: 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060204

APA StyleWang, J., Ma, N., Mo, G., Qin, X., Zhang, J., Yao, X., Guo, J., & Sun, Z. (2025). Hazards and Health Risks of the Antibacterial Agent Triclosan to Fish: A Review. Journal of Xenobiotics, 15(6), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060204