In Vitro Cytotoxic and Genotoxic Evaluation of Nitazenes, a Potent Class of New Synthetic Opioids

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

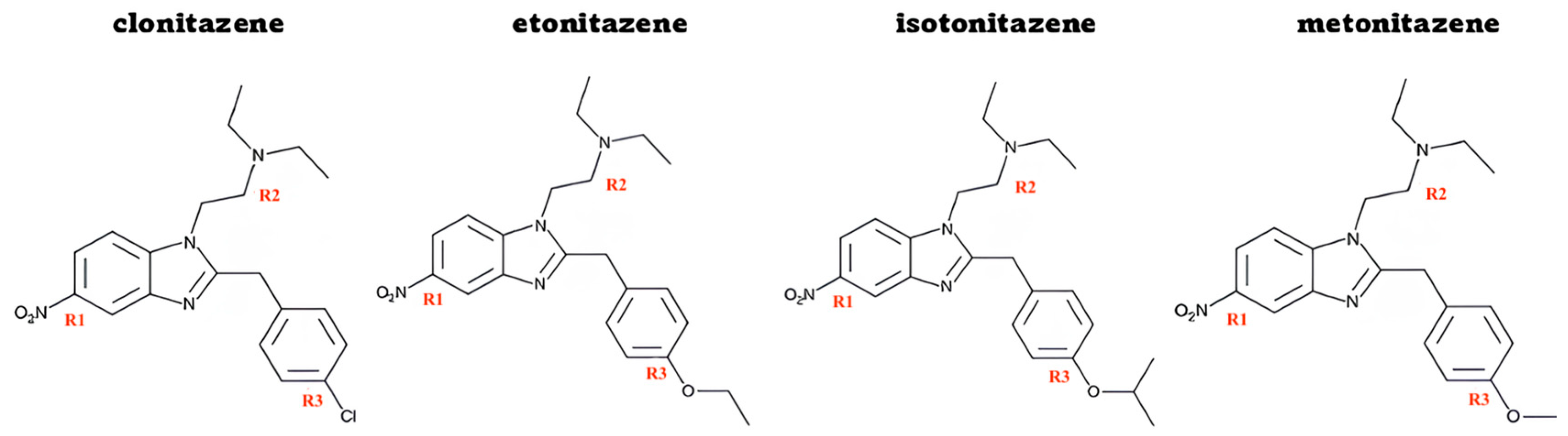

2.2. Nitazenes

2.3. Cell Culture

2.4. Test Condition

2.4.1. Selection of Concentration

2.4.2. Measurement of Cytotoxicity

2.4.3. Measurement of Cytostasis

2.4.4. Measurement of Apoptosis

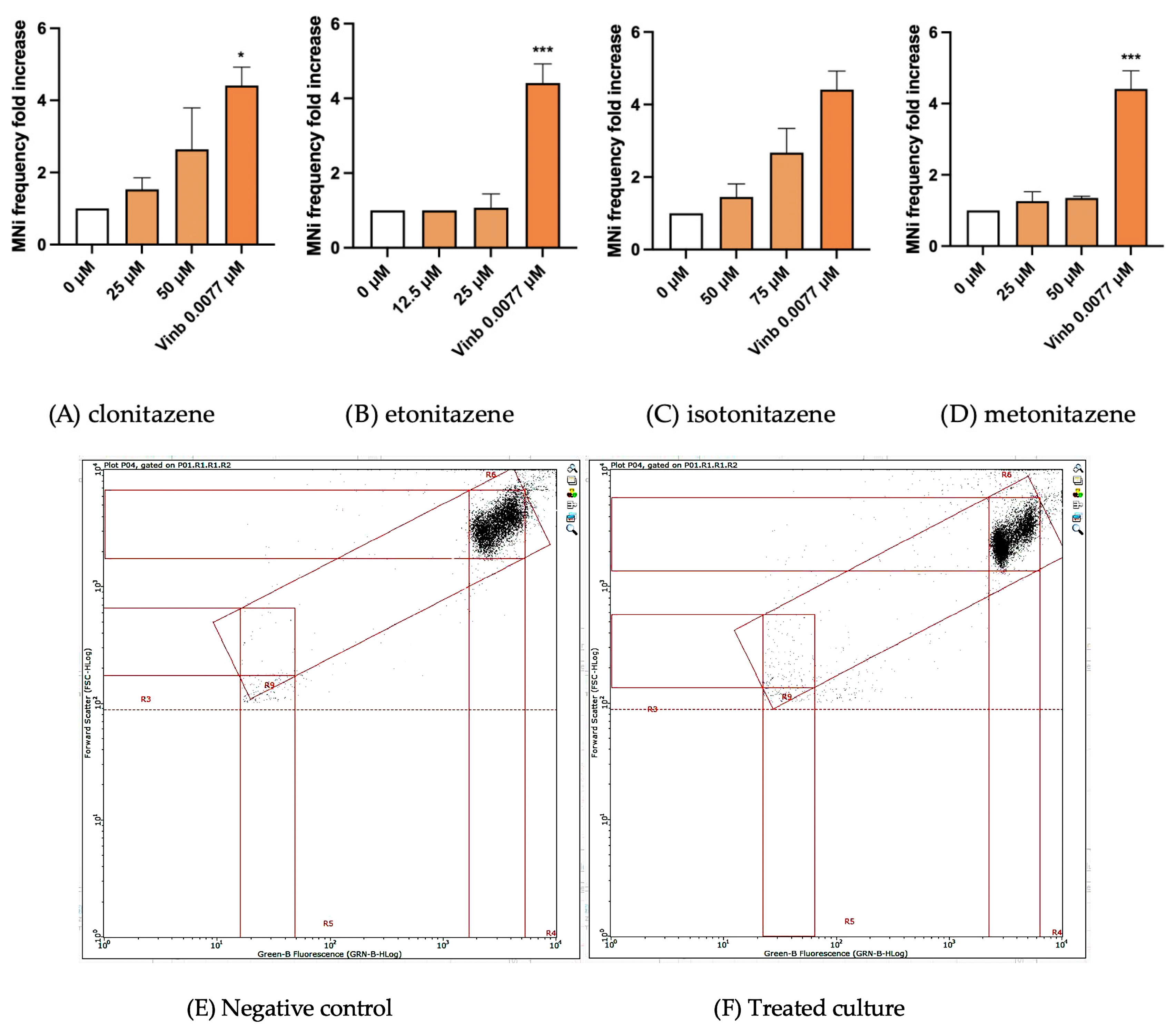

2.4.5. Measurement of MNi Frequency

2.4.6. Flow Cytometry

2.4.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

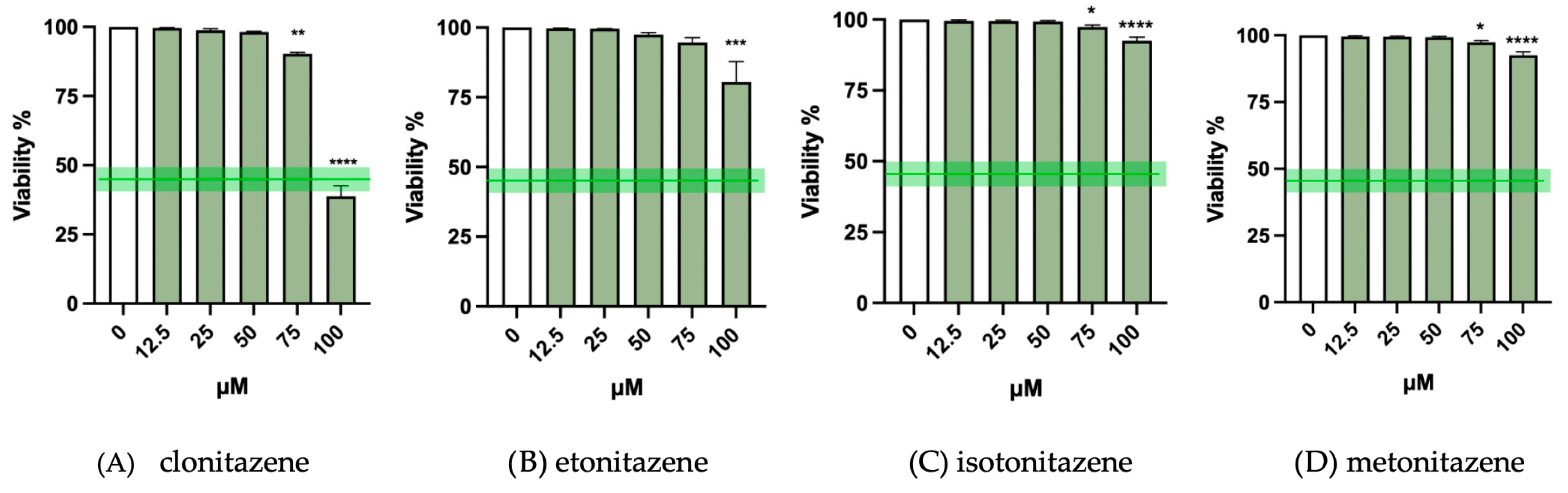

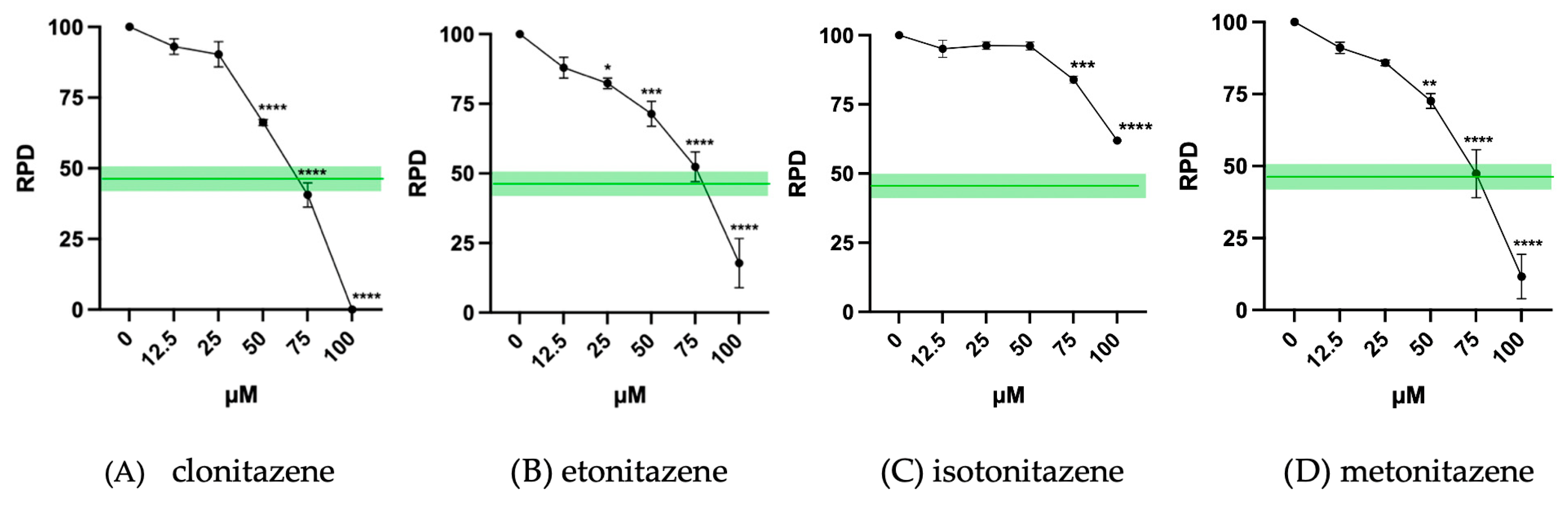

3.1. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

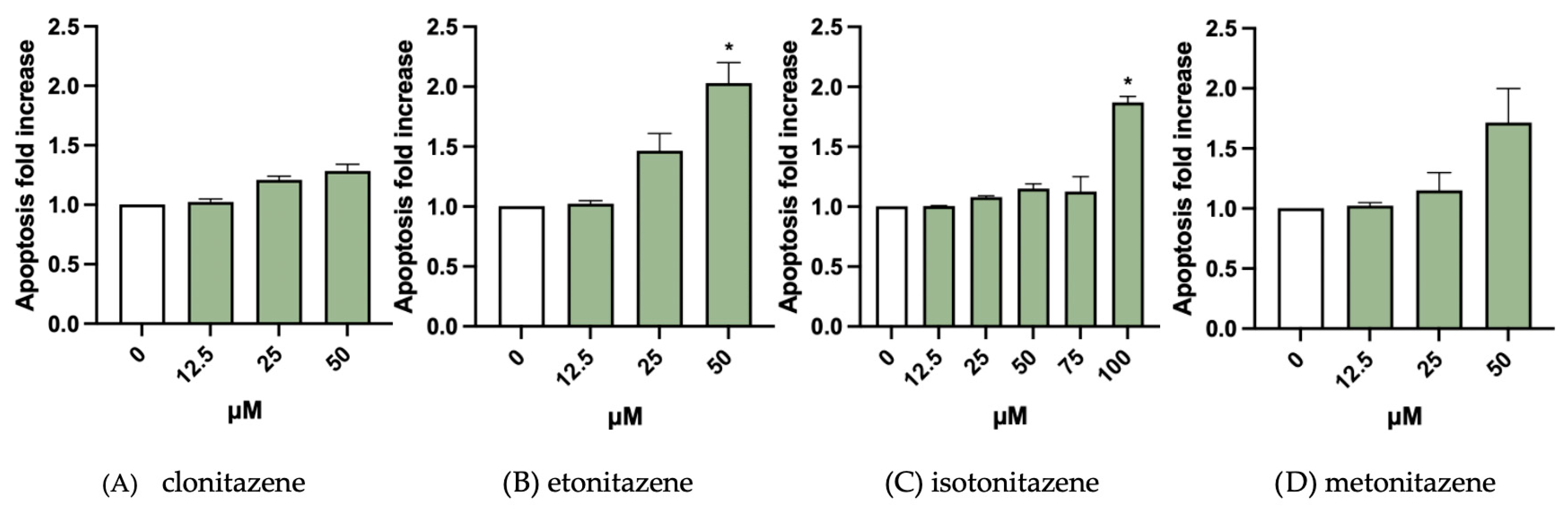

3.2. Apoptosis Evaluation

3.3. MNi Frequency Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NPS | New Psychoactive Substances |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| TK6 | Human lymphoblastoid cells |

| NSO | New Synthetic Opioids |

| EUDA | The European Union Drugs Agency |

| EWS | Early Warning System |

| CIBA | Chemische Industrie Basel |

| DEA | Drug Enforcement Administration |

| MNi | Micronuclei |

| FCM | Flow Cytometry |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| FBS | Fetal Bovin Serum |

| L-GLU | L-Glutamine |

| PS | Penicillin-Streptomycin solution |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PI | Propidium Iodide |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| BPC | Bulk Pharmaceutical Chemical |

| Vinb | Vinblastine |

| MN | Micronucleus |

| SKS | Alcoholic solution of the tested molecules |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| PD | Population Doubling |

| RPD | Relative Population Doubling |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| α-PVP | Alpha-pyrrolidinopentiophenone |

| α-PHP | alpha-pyrrolidinohexanophenone |

| 4,4′-DMAR | 4-Methyl-5-(4-methylphenyl)-4,5-dihydroxazol2-amine |

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| S9 | Supernatant 9—Exogenous metabolizing systems |

References

- European Union Drugs Agency. European Drug Report 2024. In European Drug Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vandeputte, M.M.; Stove, C.P. Navigating Nitazenes: A Pharmacological and Toxicological Overview of New Synthetic Opioids with a 2-Benzylbenzimidazole Core. Neuropharmacology 2025, 275, 110470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadem, S.N.; Arslan, Z.; Turkmen, Z. A New Synthetic Opioid Threat: A Comprehensive Review on MT-45. Forensic Sci. Int. 2025, 371, 112479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, O. Opioid Crisis: Fall in US Overdose Deaths Leaves Experts Scrambling for an Explanation. BMJ 2024, 386, q2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, J.; Brinkman, D.J. A Comprehensive Narrative Review of Protonitazene: Pharmacological Characteristics, Detection Techniques, and Toxicology. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2025, 137, e70078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel-Ollo, K.; Tõnisson, M.; Rausberg, P.; Riikoja, A.; Barndõk, T.; Oja, M.; Denissov, G.; Des Jarlais, D.; Uusküla, A. The Nitazene Epidemic in Estonia: A First Report. Eur. J. Public Health 2025, ckaf160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawilska, J.B.; Adamowicz, P.; Kurpeta, M.; Wojcieszak, J. Non-Fentanyl New Synthetic Opioids—An Update. Forensic Sci. Int. 2023, 349, 111775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeputte, M.M.; Krotulski, A.J.; Papsun, D.M.; Logan, B.K.; Stove, C.P. The Rise and Fall of Isotonitazene and Brorphine: Two Recent Stars in the Synthetic Opioid Firmament. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2021, 46, bkab082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujváry, I.; Christie, R.; Evans-Brown, M.; Gallegos, A.; Jorge, R.; De Morais, J.; Sedefov, R. DARK Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Etonitazene and Related Benzimidazoles. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 1072–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasperini, S.; Bilel, S.; Cocchi, V.; Marti, M.; Lenzi, M.; Hrelia, P. The Genotoxicity of Acrylfentanyl, Ocfentanyl and Furanylfentanyl Raises the Concern of Long-Term Consequences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzi, M.; Gasperini, S.; Bilel, S.; Corli, G.; Rombolà, F.; Hrelia, P.; Marti, M. New Synthetic Opioids: What Do We Know About the Mutagenicity of Brorphine and Its Analogues? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test No. 487: In Vitro Mammalian Cell Micronucleus Test. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/test-no-487-in-vitro-mammalian-cell-micronucleus-test_9789264264861-en.html (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Lenzi, M.; Cocchi, V.; Hrelia, P. Flow Cytometry vs Optical Microscopy in the Evaluation of the Genotoxic Potential of Xenobiotic Compounds. Cytom. Part B Clin. Cytom. 2018, 94, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, Z.; Homiski, M.L.; Dickinson, D.A.; Spellman, R.A.; Li, D.; Scott, A.; Cheung, J.R.; Coffing, S.L.; Munzner, J.B.; Sanok, K.E.; et al. Development and Validation of an in Vitro Micronucleus Assay Platform in TK6 Cells. Mutat. Res. 2012, 746, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbury, C.J.; Zhivotovsky, B. DNA Damage-Induced Apoptosis. Oncogene 2004, 23, 2797–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, M.; Cocchi, V.; Gasperini, S.; Arfè, R.; Marti, M.; Hrelia, P. Evaluation of Cytotoxic and Mutagenic Effects of the Synthetic Cathinones Mexedrone, α-PVP and α-PHP. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, M.; Gasperini, S.; Cocchi, V.; Tirri, M.; Marti, M.; Hrelia, P. Genotoxicological Characterization of (±)Cis-4,4′-DMAR and (±)Trans-4,4′-DMAR and Their Association. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franckenstein, D.; Bothe, M.K.; Hurtado, S.B.; Westphal, M. Hydromorphone Impurity 2,2-Bishydromorphone Does Not Exert Mutagenic and Clastogenic Properties via in Silico QSAR Prediction and in Vitro Ames and Micronucleus Test. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 46, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonopoulou, Μ.; Thoma, A.; Konstantinou, F.; Vlastos, D.; Hela, D. Assessing the Human Risk and the Environmental Fate of Pharmaceutical Tramadol. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 135396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A. Notes from the Field: Nitazene-Related Deaths—Tennessee, 2019–2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1196–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancox, J.C.; Wang, Y.; Copeland, C.S.; Zhang, H.; Harmer, S.C.; Henderson, G. Nitazene Opioids and the Heart: Identification of a Cardiac Ion Channel Target for Illicit Nitazene Opioids. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. Plus 2024, 10, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benigni, R.; Bossa, C. Data-Based Review of QSARs for Predicting Genotoxicity: The State of the Art. Mutagenesis 2019, 34, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, J.D.; Richard, A.; Waller, C.; Newman, M.C.; Gerberick, F. The Practice of Structure Activity Relationships (SAR) in Toxicology. Toxicol. Sci. 2000, 56, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradeep, P.; Judson, R.; DeMarini, D.M.; Keshava, N.; Martin, T.M.; Dean, J.; Gibbons, C.F.; Simha, A.; Warren, S.H.; Gwinn, M.R.; et al. Evaluation of Existing QSAR Models and Structural Alerts and Development of New Ensemble Models for Genotoxicity Using a Newly Compiled Experimental Dataset. Comput. Toxicol. 2021, 18, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Selected Concentrations for MNi Test | |

|---|---|

| clonitazene | 25 µM and 50 µM |

| etonitazene | 12.5 µM and 25 µM |

| isotonitazene | 50 µM and 75 µM |

| metonitazene | 25 µM and 50 µM |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rombolà, F.; Bartoletti, S.; Bilel, S.; Hrelia, P.; Marti, M.; Lenzi, M. In Vitro Cytotoxic and Genotoxic Evaluation of Nitazenes, a Potent Class of New Synthetic Opioids. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060203

Rombolà F, Bartoletti S, Bilel S, Hrelia P, Marti M, Lenzi M. In Vitro Cytotoxic and Genotoxic Evaluation of Nitazenes, a Potent Class of New Synthetic Opioids. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2025; 15(6):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060203

Chicago/Turabian StyleRombolà, Francesca, Sara Bartoletti, Sabrine Bilel, Patrizia Hrelia, Matteo Marti, and Monia Lenzi. 2025. "In Vitro Cytotoxic and Genotoxic Evaluation of Nitazenes, a Potent Class of New Synthetic Opioids" Journal of Xenobiotics 15, no. 6: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060203

APA StyleRombolà, F., Bartoletti, S., Bilel, S., Hrelia, P., Marti, M., & Lenzi, M. (2025). In Vitro Cytotoxic and Genotoxic Evaluation of Nitazenes, a Potent Class of New Synthetic Opioids. Journal of Xenobiotics, 15(6), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060203