Tracing Zoonotic Pathogens Through Surface Water Monitoring: A Case Study in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Site

2.2. Sampling of Wastewater, Shrimp, and Fox Feces

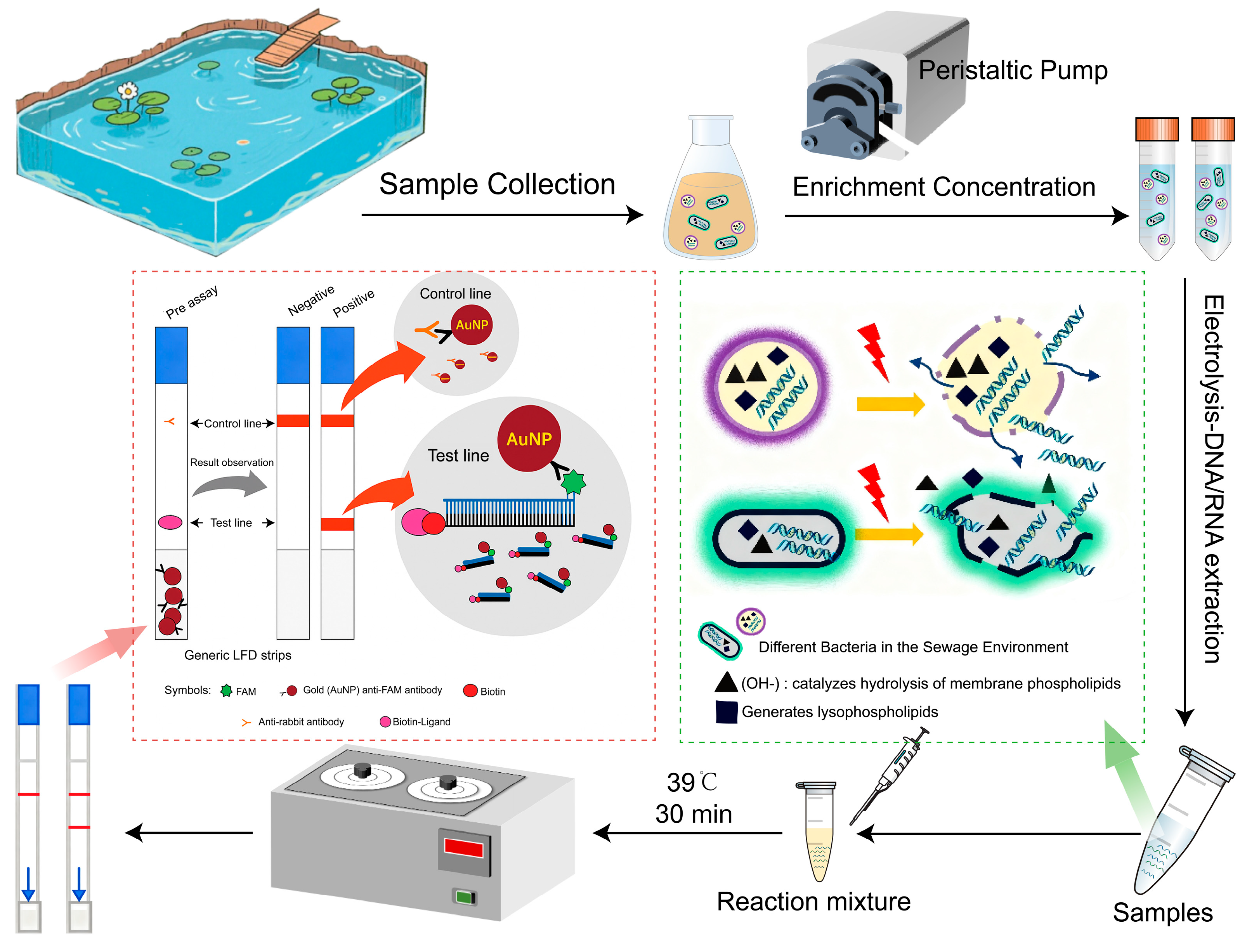

2.3. Pretreatment of Water Samples and Electrochemical DNA Extraction from Aquatic Samples

2.4. RPA-LFD Assay for Bacterial Pathogens in Surface Water

2.5. Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity of the RPA-LFD Assays

2.6. DNA and RNA Extraction from Shrimp and Fox Fecal Samples

2.7. Isolation and Identification of Bacterial Enteric Pathogens from Wastewater, Shrimp, and Fox Fecal Samples

2.8. Genome Sequencing and Gene Content Analysis

2.9. RNA Extraction and Sequencing of Norovirus GII

2.10. Bioinformatic Analysis of the Norovirus GII

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Concentration Recovery and Electrochemical DNA Extraction Efficiency

3.2. Determination of the LOD and Specificity of RPA-LFD Assays

3.3. Detection of Pathogens in Wastewater by RPA-LFD Technique

3.4. Isolation of Pathogens in Shrimp and Fox Farms

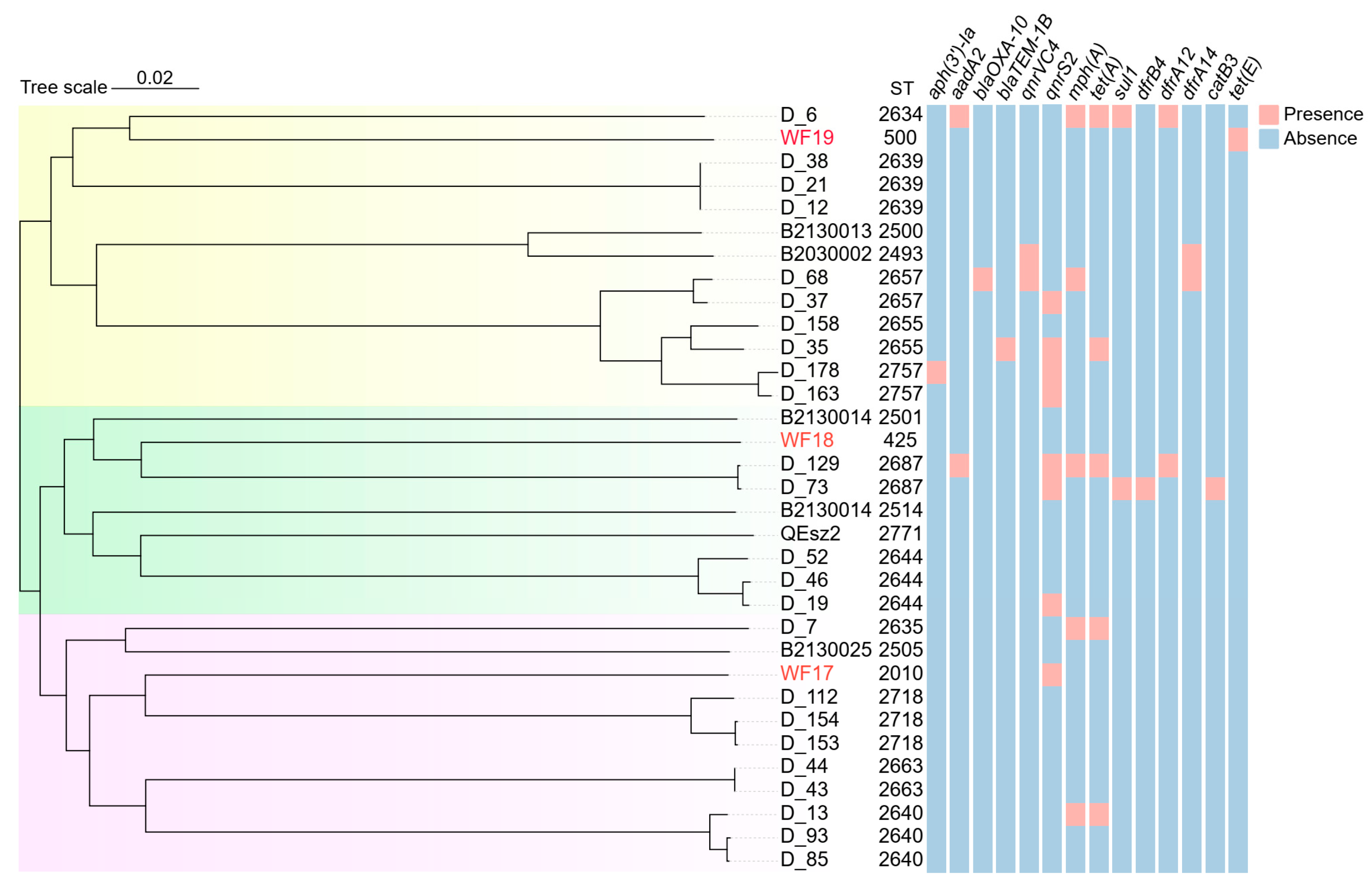

3.5. Genomic Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis of V. parahaemolyticus and A. veronii

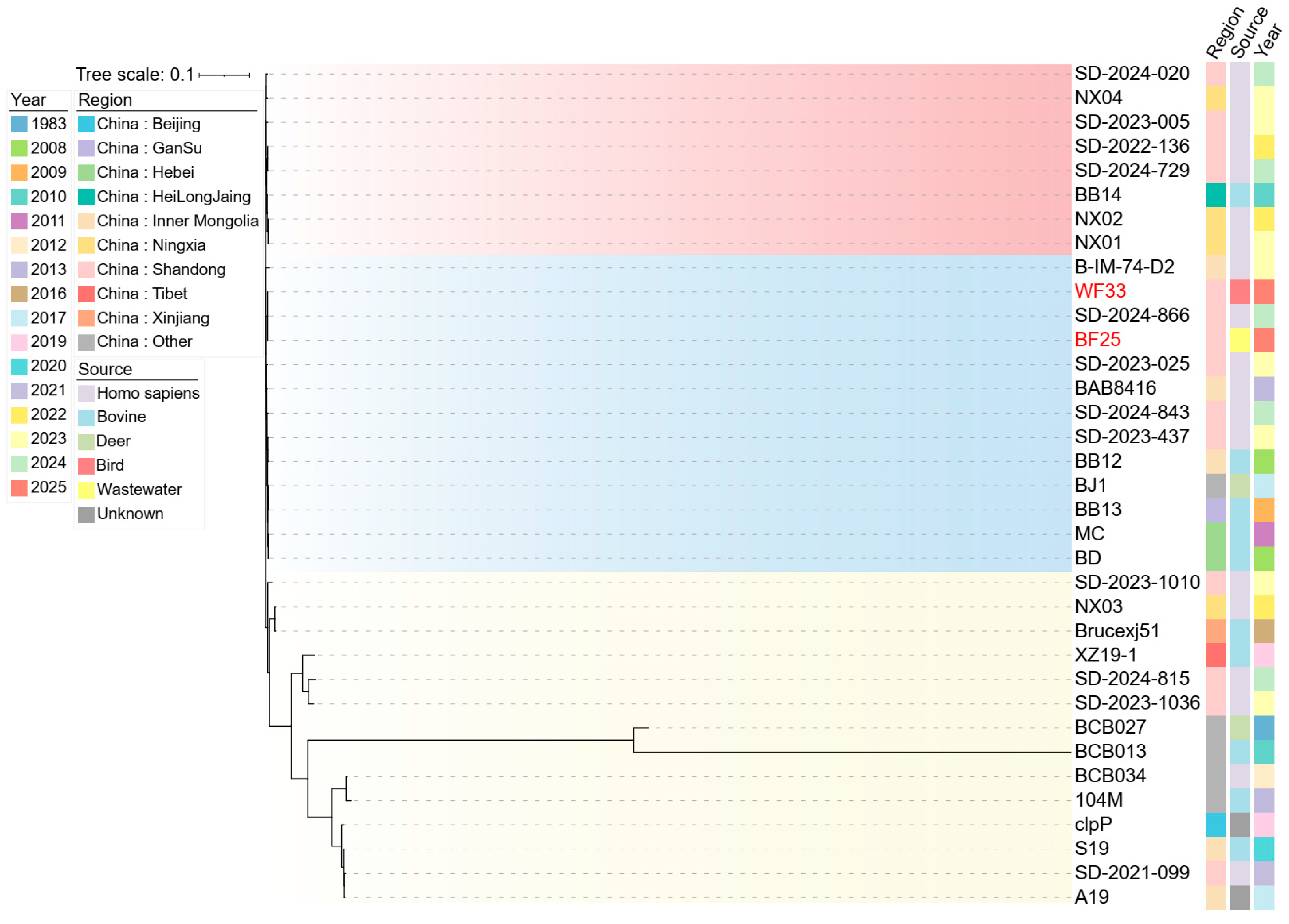

3.6. Phylogenetic Analysis of B. abortus

3.7. Genotyping and Phylogenetic Analysis of Norovirus in the Surface Water and Fox Farm

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RPA-LFD | Recombinase Polymerase Amplification coupled with Lateral Flow Dipstick |

| LOD | Limits of Detection |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| ARG | Antimicrobial Resistance Gene(s) |

| MDR | Multidrug-Resistant |

| MLST | Multilocus Sequence Typing |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

References

- Reverter, M.; Sarter, S.; Caruso, D.; Avarre, J.C.; Combe, M.; Pepey, E.; Pouyaud, L.; Vega-Heredía, S.; de Verdal, H.; Gozlan, R.E. Aquaculture at the crossroads of global warming and antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.G.; Domingues, C.P.F.; Figueiredo, J.F.; Dionisio, F.; Botelho, A.; Nogueira, T. Estuarine aquacultures at the crossroads of animal production and antibacterial resistance: A metagenomic approach to the resistome. Biology 2022, 11, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.; Yin, G.; Liu, M.; Chen, C.; Jiang, Y.; Hou, L.; Zheng, Y. A systematic review of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in estuarine and coastal environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 146009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haile, A.T.; Kibret, M.; Haileselassie, M.M.; Anley, K.A.; Bekele, T.W.; Kassa, J.M.; Demissie, K.; Werner, D.; Graham, D.; Mateo-Sagasta, J. Designing a monitoring plan for microbial water quality and waterborne antimicrobial resistance in the Akaki catchment, Ethiopia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusi, J.; Ojewole, C.O.; Ojewole, A.E.; Nwi-Mozu, I. Antimicrobial resistance development pathways in surface waters and public health implications. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborda, P.; Sanz-García, F.; Ochoa-Sánchez, L.E.; Gil-Gil, T.; Hernando-Amado, S.; Martínez, J.L. Wildlife and antibiotic resistance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 873989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milijasevic, M.; Veskovic-Moracanin, S.; Babic Milijasevic, J.; Petrovic, J.; Nastasijevic, I. Antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture: Risk mitigation within the One Health context. Foods 2024, 13, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algammal, A.M.; Mabrok, M.; Ezzat, M.; Alfifi, K.J.; Esawy, A.M.; Elmasry, N.; El-Tarabili, R.M. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) pattern, virulence determinant and AMR genes of emerging multi-drug resistant Edwardsiella tarda in Nile tilapia and African catfish. Aquaculture 2022, 548, 737643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopo, M.G.; Mabrok, M.; Abu-Elala, N.; Yu, Y. Navigating fish immunity: Focus on mucosal immunity and the evolving landscape of mucosal vaccines. Biology 2024, 13, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrok, M.; Algammal, A.M.; El-Tarabili, R.M.; Dessouki, A.A.; ElBanna, N.I.; Abd-Elnaby, M.; El-Lamie, M.M.M.; Rodkhum, C. Enterobacter cloacae as a re-emerging pathogen affecting mullets (Mugil spp.): Pathogenicity testing, LD50, antibiogram, and encoded antimicrobial resistance genes. Aquaculture 2024, 583, 740619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raharjo, H.M.; Budiyansah, H.; Mursalim, M.F.; Chokmangmeepisarn, P.; Sakulworakan, R.; Debnath, P.P.; Sivaramasamy, E.; Intan, S.T.; Chuanchuen, R.; Dong, H.T.; et al. The first evidence of blaCTX-M-55, QnrVC5, and novel insight into the genome of MDR Vibrio vulnificus isolated from Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer) identified by resistome analysis. Aquaculture 2023, 571, 739500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein, M.; Ripanda, A.S. Pollution by antimicrobials and antibiotic resistance genes in East Africa: Occurrence, sources, and potential environmental implications. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 101969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.; Thomson, N.; Weill, F.X.; Holt, K.E. Genomic insights into the emergence and spread of antimicrobial-resistant bacterial pathogens. Science 2018, 360, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, M.E.; Webster, G.; Perry, W.B.; Baldwin, A.; Rushton, L.; Pass, D.A.; Cross, G.; Durance, I.; Muziasari, W.; Kille, P.; et al. National-scale antimicrobial resistance surveillance in wastewater: A comparative analysis of HT qPCR and metagenomic approaches. Water Res. 2024, 262, 121989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziarati, M.; Zorriehzahra, M.J.; Hassantabar, F.; Mehrabi, Z.; Dhawan, M.; Sharun, K.; Emran, T.B.; Dhama, K.; Chaicumpa, W.; Shamsi, S. Zoonotic diseases of fish and their prevention and control. Vet. Q. 2022, 42, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, A.; Silva, V.; Poeta, P.; Aonofriesei, F. Vibrio spp.: Life strategies, ecology, and risks in a changing environment. Diversity 2022, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches-Fernandes, G.M.M.; Sá-Correia, I.; Costa, R. Vibriosis outbreaks in aquaculture: Addressing environmental and public health concerns and preventive therapies using gilthead seabream farming as a model system. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 904815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Fu, S.; Qu, B.; Defoirdt, T. One health pathogen surveillance demonstrated the dissemination of gut pathogens within the two coastal regions associated with intensive farming. Gut Pathog. 2021, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Pang, B.; Lan, R.; Wei, D.; Qu, B.; Liu, Y. Continuous genomic surveillance monitored the in vivo evolutionary trajectories of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and identified a new virulent genotype. mSystems 2021, 6, e01254-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytkönen, A.; Meriläinen, P.; Valkama, K.; Hokajärvi, A.M.; Ruponen, J.; Nummela, J.; Mattila, H.; Tulonen, T.; Kivistö, R.; Pitkänen, T. Scenario-based assessment of fecal pathogen sources affecting bathing water quality: Novel treatment options to reduce norovirus and Campylobacter infection risks. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1353798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wareth, G.; Melzer, F.; El-Diasty, M.; Schmoock, G.; Elbauomy, E.; Abdel-Hamid, N.; Sayour, A.; Neubauer, H. Isolation of Brucella abortus from a dog and a cat confirms their biological role in re-emergence and dissemination of bovine brucellosis on dairy farms. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, e27–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, G.; Roche, X.; Brioudes, A.; von Dobschuetz, S.; Fasina, F.O.; Kalpravidh, W.; Makonnen, Y.; Lubroth, J.; Sims, L. A literature review of the use of environmental sampling in the surveillance of avian influenza viruses. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador, D.; Neto, C.; Benoliel, M.J.; Caeiro, M.F. Assessment of the presence of hepatitis E virus in surface water and drinking water in Portugal. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.; Ng, C.; Nshimyimana, J.P.; Loh, L.L.; Gin, K.Y.; Thompson, J.R. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) for assessment of microbial water quality: Current progress, challenges, and future opportunities. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Long, Y.; Yang, X.; Du, X.; Du, X.; Zahan, N.; Deng, Z.; Du, C.; Fu, S. Harnessing a Surface Water-Based Multifaceted Approach to Combat Zoonotic Viruses: A Rural Perspective from Bangladesh and China. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, S.; Rausch, V.; Bier, F.F.; von Nickisch-Rosenegk, M. Rapid detection of Plasmodium falciparum with isothermal recombinase polymerase amplification and lateral flow analysis. Malar. J. 2014, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Zhao, G.; Wang, H.; He, C.; Huan, Y.; He, H. Development of a recombinase polymerase amplification combined with lateral-flow dipstick assay for detection of bovine ephemeral fever virus. Mol. Cell. Probes 2018, 38, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Luo, N.; Zong, Y.; Jia, M.; Rao, Y.; Huang, H.; Jiang, H. Recombinase polymerase amplification combined with lateral flow dipstick assay for the rapid and sensitive detection of Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yu, H.; Lv, M.; Gao, H.; Lin, W.; Li, W.; Cheng, M.; Huang, Y.; Meng, D.; Wen, T.; et al. Dual-mode electro-driven biosensor: Low-voltage lysis and hybridization synergy for rapid and sensitive pathogen screening. Bioelectrochemistry 2025, 168, 109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-R.; Xu, J.-N.; Fan, H.-Y.; Zheng, Y.-P.; Zhou, T.-Q.; Zhang, Y.; Dan, X. Establishment of a method for rapid detection of Aeromonas hydrophila by recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) combined with lateral flow strips (LFD). Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2024, 48, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y. A recombinase polymerase amplification-based lateral flow strip assay for rapid detection of genogroup II noroviruses in the field. Arch. Virol. 2020, 165, 2767–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumaa, M.M.; Cao, X.; Li, Z.; Lou, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Fu, B. Establishment of a recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) assay for the detection of Brucella spp. infection. Mol. Cell. Probes 2019, 47, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Ren, Y.; Han, X.; Xue, J.; Shan, T.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Recombinase polymerase amplification-lateral flow (RPA-LF) assay combined with immunomagnetic separation for rapid visual detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in raw oysters. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 2903–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.; Shi, W.; Ma, C.; Tang, W.; Qian, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Shen, J.; Ji, J.; Ma, J.; et al. Duplex detection of Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio parahaemolyticus by real-time recombinase polymerase amplification. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2022, 35, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Deng, Z.; He, F.; Jiang, X.; Shen, L. Longitudinal wastewater surveillance of four key pathogens during an unprecedented large-scale COVID-19 outbreak in China facilitated a novel strategy for addressing public health priorities-A proof of concept study. Water Res. 2023, 247, 120751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Dahouk, S.; Nöckler, K. Implications of laboratory diagnosis on brucellosis therapy. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2011, 9, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbehiry, A.; Aldubaib, M.; Al Rugaie, O.; Marzouk, E.; Abaalkhail, M.; Moussa, I.; El-Husseiny, M.H.; Abalkhail, A.; Rawway, M. Proteomics-based screening and antibiotic resistance assessment of clinical and sub-clinical Brucella species: An evolution of brucellosis infection control. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M.; et al. The RAST Server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiden, M.C.; Bygraves, J.A.; Feil, E.; Morelli, G.; Russell, J.E.; Urwin, R.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, J.; Zurth, K.; Caugant, D.A.; et al. Multilocus sequence typing: A portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 3140–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zankari, E.; Hasman, H.; Cosentino, S.; Vestergaard, M.; Rasmussen, S.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Larsen, M.V. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2640–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahwage, S.; Lanzarini, N.M.; de Paula, B.B.; Saggioro, E.M.; de Faro Motta, A.T.; Mannarino, C.F.; Miagostovich, M.P. Viral genetic diversity in surface and groundwater at a non-operational dumpsite and its surrounding neighborhood. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1002, 180604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Kang, S.; Fuhrmann, L.; Topolsky, I.; Kent, C.; Quick, J.; Stadler, T.; Julian, T.R.; Beerenwinkel, N. Characterizing influenza A virus lineages and clinically relevant mutations through high-coverage wastewater sequencing. Water Res. 2025, 287, 124453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, T.W.; Silvester, R.; Kevill, J.; Farkas, K.; Malham, S.K.; Cross, G.; Robins, P.; Jones, D.L. Predicting norovirus contamination and antimicrobial resistance in coastal waters from community and hospital-derived sources. Water Res. 2025, 288, 124555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Wang, N.; Jing, H.; Lv, J.; Wu, S. Integrating RPA-LFD and TaqMan qPCR for rapid on-site screening and accurate laboratory identification of Coilia brachygnathus and Coilia nasus in the Yangtze River. Foods 2025, 14, 3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Zhu, Q.; Chang, Y.; Wang, L.; Teng, Z.; Wei, X.; Chang, M.; Liu, M.; et al. Establishment and application of dual isothermal amplification of Pasteurella multocida and Streptococcus suis in pigs. Vet. Res. Forum 2025, 16, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivorakul, S.; Guntawang, T.; Sittisak, T.; Gordsueb, T.; Boonsri, K.; Khattiya, R.; Sthitmatee, N.; Pringproa, K. Development of reverse transcriptase recombinase polymerase amplification combined with lateral flow dipstick for rapid detection of Tilapia Lake Virus (TiLV): Pilot study. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. of Weeks | Time | Sample Name | V. parahaemolyticus | Brucella | Aeromonas veronii | Norovirus | V. cholerae | A. hydrophila |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| River | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 February 2025 | WW-1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | 8 February 2025 | WW-3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | 15 February 2025 | WW-4 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | 22 February 2025 | WW-5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | 1 March 2025 | WW-6 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6 | 8 March 2025 | WW-7 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | 15 March 2025 | WW-8 | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| 8 | 22 March 2025 | WW-10 | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| 9 | 29 March 2025 | WW-12 | + | - | + | + | - | - |

| 10 | 5 April 2025 | WW-15 | - | - | - | + | - | - |

| 11 | 12 April 2025 | WW-17 | - | + | - | + | - | - |

| 12 | 19 April 2025 | WW-21 | - | - | - | + | - | - |

| Shrimp | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 February 2025 | SW-1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | 8 February 2025 | SW-2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | 15 February 2025 | SW-3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | 22 February 2025 | SW-4 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | 1 March 2025 | SW-5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6 | 8 March 2025 | SW-6 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | 15 March 2025 | SW-7 | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| 8 | 22 March 2025 | SW-8 | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| 9 | 29 March 2025 | SW-9 | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| 10 | 5 April 2025 | SW-10 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11 | 12 April 2025 | SW-11 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 12 | 19 April 2025 | SW-12 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fox feces | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 February 2025 | WB1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | 8 February 2025 | WB2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | 15 February 2025 | WB3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | 22 February 2025 | WB4 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | 1 March 2025 | WB5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6 | 8 March 2025 | WB6 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | 15 March 2025 | WB7 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | 22 March 2025 | WB8 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 9 | 29 March 2025 | WB13 | - | - | - | + | - | - |

| 10 | 5 April 2025 | WB17 | - | - | - | + | - | - |

| 11 | 12 April 2025 | WB21 | - | + | - | + | - | - |

| 12 | 19 April 2025 | WB28 | - | + | - | + | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Du, X.; Du, X.; Yi, L.; He, F.; Fu, S. Tracing Zoonotic Pathogens Through Surface Water Monitoring: A Case Study in China. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120252

Wang Y, Du X, Du X, Yi L, He F, Fu S. Tracing Zoonotic Pathogens Through Surface Water Monitoring: A Case Study in China. Microbiology Research. 2025; 16(12):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120252

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yi, Xinyan Du, Xin Du, Liu Yi, Fenglan He, and Songzhe Fu. 2025. "Tracing Zoonotic Pathogens Through Surface Water Monitoring: A Case Study in China" Microbiology Research 16, no. 12: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120252

APA StyleWang, Y., Du, X., Du, X., Yi, L., He, F., & Fu, S. (2025). Tracing Zoonotic Pathogens Through Surface Water Monitoring: A Case Study in China. Microbiology Research, 16(12), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120252