Impact of an Essential-Oil-Based Oral Rinse on Oral and Gut Microbiota Diversity: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Enrollment and Experimental Design

2.2. 16S rDNA Sequencing

2.3. Bioinformatic and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Evaluation

3.2. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Analysis

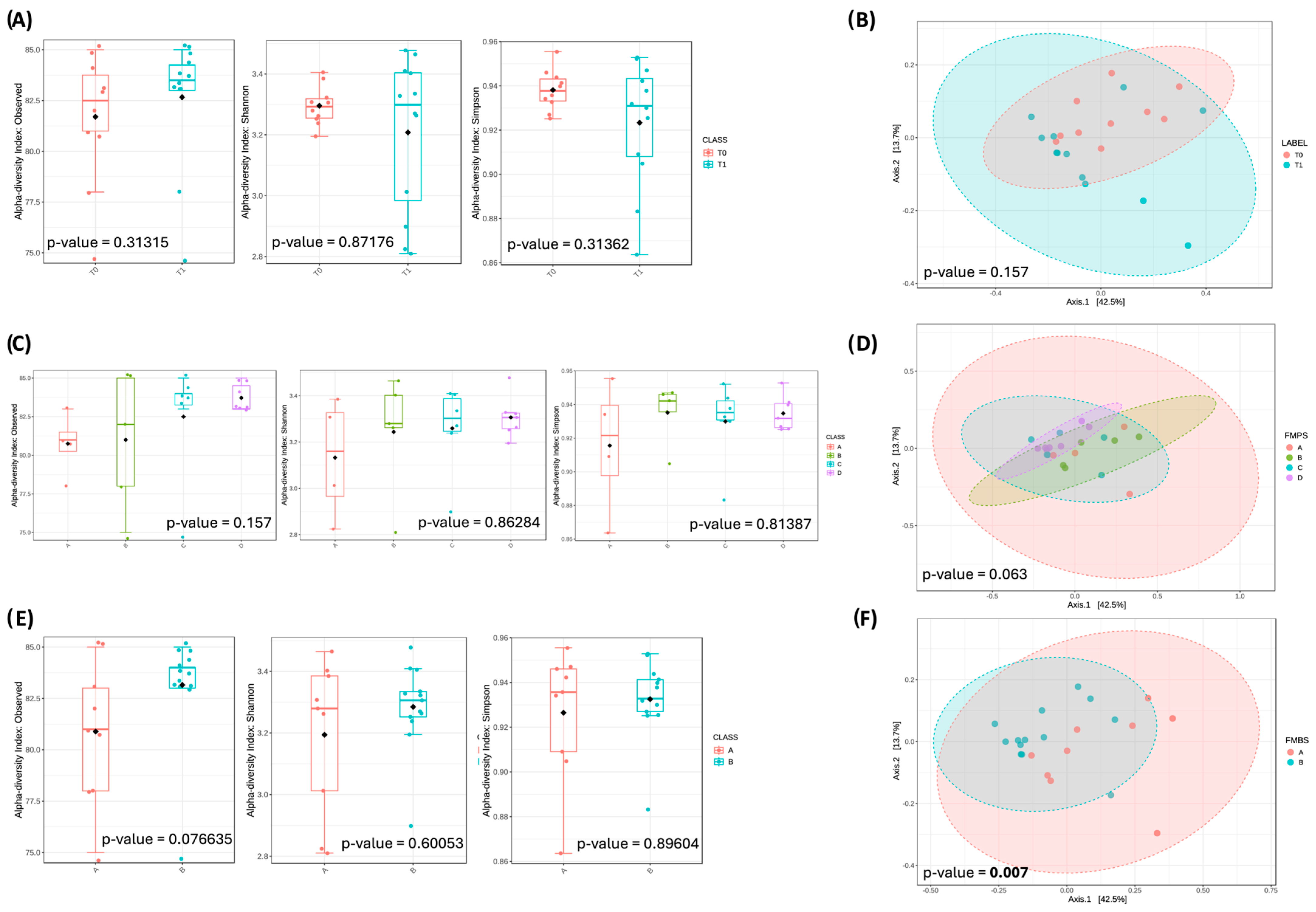

3.3. Oral Microbiota Biodiversity

3.3.1. Community Overview

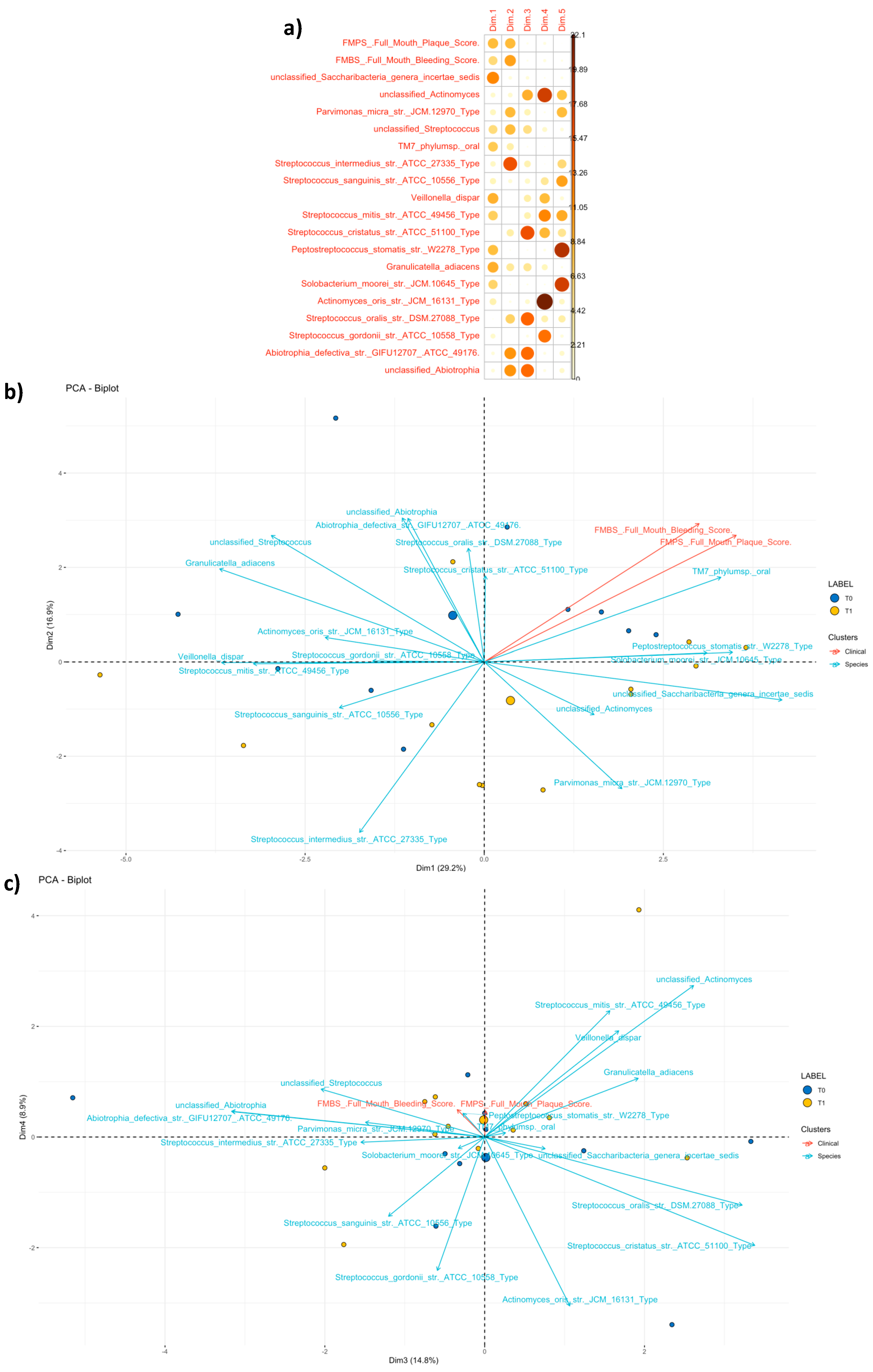

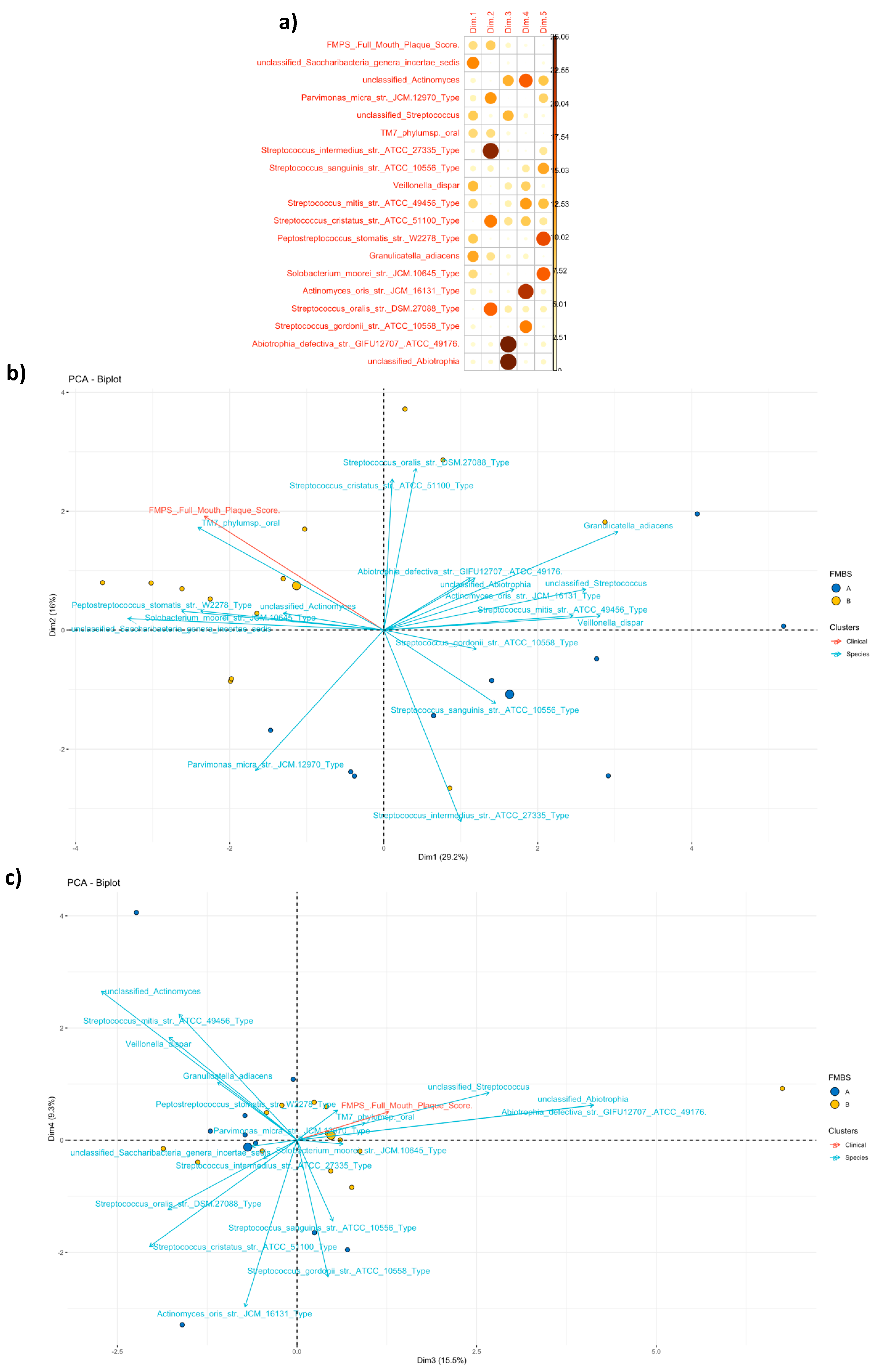

3.3.2. Community Profiling and Signature

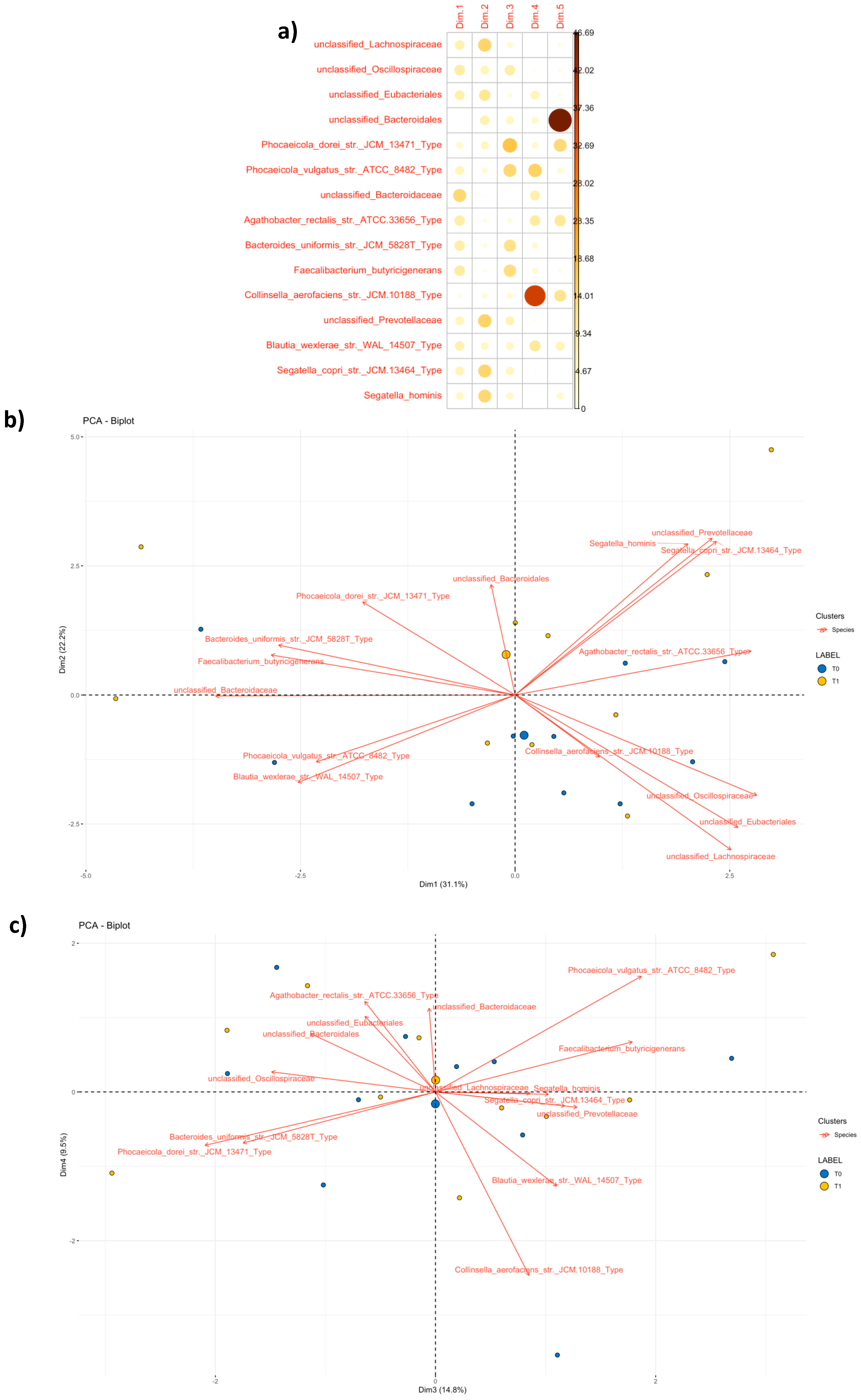

3.4. Fecal Microbiota Biodiversity

3.4.1. Community Overview

3.4.2. Community Profiling and Signature

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Study Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newman, T.; Carranza, K. Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology, 11th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4377-0416-7. [Google Scholar]

- Nazir, M.A. Prevalence of Periodontal Disease, Its Association with Systemic Diseases and Prevention. Int. J. Health Sci. 2017, 1, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz, M.; Herrera, D.; Kebschull, M.; Chapple, I.; Jepsen, S.; Berglundh, T.; Sculean, A.; Tonetti, M.S. EFP Workshop Participants and Methodological Consultants Treatment of Stage I–III Periodontitis—The EFP S3 Level Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 4–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socransky, S.S.; Smith, C.; Haffajee, A.D. Subgingival Microbial Profiles in Refractory Periodontal Disease: Refractory Microbial Profiles. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2002, 29, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patini, R.; Staderini, E.; Lajolo, C.; Lopetuso, L.; Mohammed, H.; Rimondini, L.; Rocchetti, V.; Franceschi, F.; Cordaro, M.; Gallenzi, P. Relationship between Oral Microbiota and Periodontal Disease: A Systematic Review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 5775–5788. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, D.; Berglundh, T.; Schwarz, F.; Chapple, I.; Jepsen, S.; Sculean, A.; Kebschull, M.; Papapanou, P.N.; Tonetti, M.S.; Sanz, M.; et al. Prevention and Treatment of Peri-implant Diseases—The EFP S3 Level Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 4–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, A.M.; Shanahan, F. The Gut Flora as a Forgotten Organ. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unusan, N. Essential Oils and Microbiota: Implications for Diet and Weight Control. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 104, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendreau, L.; Loewy, Z.G. Epidemiology and Etiology of Denture Stomatitis. J. Prosthodont. 2011, 20, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arweiler, N.B.; Netuschil, L. The Oral Microbiota. In Microbiota. In Microbiota of the Human Body: Implications in Health and Disease; Schwiertz, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 45–60. ISBN 978-3-319-31248-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in Health and Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Ni, C.; Du, Z.; Yan, F. Human Oral Microbiota and Its Modulation for Oral Health. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 99, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandary, R.; Venugopalan, G.; Ramesh, A.; Tartaglia, G.; Singhal, I.; Khijmatgar, S. Microbial Symphony: Navigating the Intricacies of the Human Oral Microbiome and Its Impact on Health. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonocito, S.; Giudice, A.; Polizzi, A.; Troiano, G.; Merlo, E.M.; Sclafani, R.; Grosso, G.; Isola, G. A Cross-Talk between Diet and the Oral Microbiome: Balance of Nutrition on Inflammation and Immune System’s Response during Periodontitis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, M.; Aleya, S.; Alsubih, M.; Aleya, L. Microbiome Dynamics: A Paradigm Shift in Combatting Infectious Diseases. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Daza, M.C.; Pulido-Mateos, E.C.; Lupien-Meilleur, J.; Guyonnet, D.; Desjardins, Y.; Roy, D. Polyphenol-Mediated Gut Microbiota Modulation: Toward Prebiotics and Further. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 689456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Daza, M.C.; De Vos, W.M. Polyphenols as Drivers of a Homeostatic Gut Microecology and Immuno-Metabolic Traits of Akkermansia muciniphila: From Mouse to Man. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, R.; Asopa, S.; Joseph, M.D.; Singh, B.; Rajguru, J.; Saidath, K.; Sharma, U. Red Complex: Polymicrobial Conglomerate in Oral Flora: A Review. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Weijden, F.A.; Slot, D.E. Efficacy of Homecare Regimens for Mechanical Plaque Removal in Managing Gingivitis a Meta Review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, S77–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bescos, R.; Ashworth, A.; Cutler, C.; Brookes, Z.L.; Belfield, L.; Rodiles, A.; Casas-Agustench, P.; Farnham, G.; Liddle, L.; Burleigh, M.; et al. Effects of Chlorhexidine Mouthwash on the Oral Microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, E.R.; Sanders, J.G.; Song, S.J.; Amato, K.R.; Clark, A.G.; Knight, R. The Human Microbiome in Evolution. BMC Biol. 2017, 15, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.; Lee, S.M.; Shen, Y.; Khosravi, A.; Mazmanian, S.K. Disease. In Advances in Immunology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 107, pp. 243–274. ISBN 978-0-12-381300-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz, M.; Kornman, K.; on behalf of working group 3 of the joint EFP/AAP Workshop. Periodontitis and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: Consensus Report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, S164–S169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, K.J.; Nieminen, M.S.; Valtonen, V.V.; Rasi, V.P.; Kesaniemi, Y.A.; Syrjala, S.L.; Jungell, P.S.; Isoluoma, M.; Hietaniemi, K.; Jokinen, M.J. Association between Dental Health and Acute Myocardial Infarction. BMJ 1989, 298, 779–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, F.Q.; Almeida-da-Silva, C.L.C.; Huynh, B.; Trinh, A.; Liu, J.; Woodward, J.; Asadi, H.; Ojcius, D.M. Association between Periodontal Pathogens and Systemic Disease. Biomed. J. 2019, 42, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippa, S.; Conte, M. Dysbiotic Events in Gut Microbiota: Impact on Human Health. Nutrients 2014, 6, 5786–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.; Bunyavanich, S. Role of the Microbiome in Food Allergy. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Hu, Y.; Bruner, D.W. Composition of Gut Microbiota and Its Association with Body Mass Index and Lifestyle Factors in a Cohort of 7–18 Years Old Children from the American Gut Project: Gut Microbiota and BMI in Children. Pediatr. Obes. 2019, 14, e12480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérard, P. Gut Microbiota and Obesity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Legarrea, P.; Fuller, N.R.; Zulet, M.A.; Martinez, J.A.; Caterson, I.D. The Influence of Mediterranean, Carbohydrate and High Protein Diets on Gut Microbiota Composition in the Treatment of Obesity and Associated Inflammatory State. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 23, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Candon, S.; Perez-Arroyo, A.; Marquet, C.; Valette, F.; Foray, A.-P.; Pelletier, B.; Milani, C.; Ventura, M.; Bach, J.-F.; Chatenoud, L. Antibiotics in Early Life Alter the Gut Microbiome and Increase Disease Incidence in a Spontaneous Mouse Model of Autoimmune Insulin-Dependent Diabetes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippo, C.; Di Paola, M.; Giani, T.; Tirelli, F.; Cimaz, R. Gut Microbiota in Children and Altered Profiles in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J. Autoimmun. 2019, 98, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, R.E.; Peterson, D.A.; Gordon, J.I. Ecological and Evolutionary Forces Shaping Microbial Diversity in the Human Intestine. Cell 2006, 124, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Huang, C.-P.; Lan, H.; Lau, H.-G.; Chiang, C.-P.; Chen, Y.-W. Association of Periodontitis and Oral Microbiomes with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Narrative Systematic Review. J. Dent. Sci. 2022, 17, 1762–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, M.; Indari, O.; Baral, B.; Jakhmola, S.; Tiwari, D.; Bhandari, V.; Pandey, R.K.; Bala, K.; Sonawane, A.; Jha, H.C. Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota from the Perspective of the Gut–Brain Axis: Role in the Provocation of Neurological Disorders. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, P.; Sarma, D.K.; Kumawat, M.; Tiwari, R.; Verma, V.; Nagpal, R.; Kumar, M. Implication of Obesity and Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis in the Etiology of Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, Y.; Hua, X.; Wan, Y.; Suman, S.; Zhu, B.; Dagnall, C.L.; Hutchinson, A.; Jones, K.; Hicks, B.D.; Shi, J.; et al. Comparison of Oral Microbiota Collected Using Multiple Methods and Recommendations for New Epidemiologic Studies. mSystems 2020, 5, e00156-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, N.M.; Charles, C.H.; Dills, S.S. Long-Term Effects of Listerine Antiseptic on Dental Plaque and Gingivitis. J. Clin. Dent. 1989, 1, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Julious, S.A. Sample Size of 12 per Group Rule of Thumb for a Pilot Study. Pharm. Stat. 2005, 4, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiese, M.S. Observational and Interventional Study Design Types; an Overview. Biochem. Medica 2014, 24, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.R.; Wang, Q.; Fish, J.A.; Chai, B.; McGarrell, D.M.; Sun, Y.; Brown, C.T.; Porras-Alfaro, A.; Kuske, C.R.; Tiedje, J.M. Ribosomal Database Project: Data and Tools for High Throughput rRNA Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D633–D642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, E.; Sola, D.; Caramaschi, A.; Mignone, F.; Bona, E.; Fallarini, S. A Pilot Study on Clinical Scores, Immune Cell Modulation, and Microbiota Composition in Allergic Patients with Rhinitis and Asthma Treated with a Probiotic Preparation. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 183, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Cascella, F.; Mellai, M.; Barizzone, N.; Mignone, F.; Massa, N.; Nobile, V.; Bona, E. Influence of Sex on the Microbiota of the Human Face. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic Biomarker Discovery and Explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Boernigen, D.; Tickle, T.L.; Morgan, X.C.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Computational Meta’omics for Microbial Community Studies. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2013, 9, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S. Global Prevalence of Periodontitis: A Literarure Review. Int. Arab. J. Dent. 2012, 3, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yazicioglu, O.; Ucuncu, M.K.; Guven, K. Ingredients in Commercially Available Mouthwashes. Int. Dent. J. 2024, 74, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spuldaro, T.R.; Rogério Dos Santos Júnior, M.; Vicentis De Oliveira Fernandes, G.; Rösing, C.K. Efficacy of Essential Oil Mouthwashes With and Without Alcohol on the Plaque Formation: A Randomized, Crossover, Double-Blinded, Clinical Trial. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2021, 21, 101527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnaraj, H.; Vinay Vardhan, M.; Gudibandi, H.V.; Kumar, J.S.; Kumarasamy, S. Abiotrophia defectiva: A Rare Causative Agent of Infective Endocarditis With Severe Complications. Cureus 2024, 16, e73715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyoshi, T.; Oge, S.; Nakata, S.; Ueno, Y.; Ukita, H.; Kousaka, R.; Miura, Y.; Yoshinari, N.; Yoshida, A. Gemella haemolysans Inhibits the Growth of the Periodontal Pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthil Kumar, S.; Gunda, V.; Reinartz, D.M.; Pond, K.W.; Thorne, C.A.; Santiago Raj, P.V.; Johnson, M.D.L.; Wilson, J.E. Oral Streptococci S. Anginosus and S. Mitis Induce Distinct Morphological, Inflammatory, and Metabolic Signatures in Macrophages. Infect. Immunol. 2024, 92, e00536-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewhirst, F.E.; Paster, B.J.; Tzellas, N.; Coleman, B.; Downes, J.; Spratt, D.A.; Wade, W.G. Characterization of Novel Human Oral Isolates and Cloned 16S rDNA Sequences That Fall in the Family Coriobacteriaceae: Description of Olsenella Gen. Nov., Reclassification of Lactobacillus uli as Olsenella uli Comb. Nov. and Description of Olsenella Profusa Sp. Nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001, 51, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, X.-Y.; Li, W.-J.; Stackebrandt, E. An Update of the Structure and 16S rRNA Gene Sequence-Based Definition of Higher Ranks of the Class Actinobacteria, with the Proposal of Two New Suborders and Four New Families and Emended Descriptions of the Existing Higher Taxa. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraatz, M.; Wallace, R.J.; Svensson, L. Olsenella Umbonata Sp. Nov., a Microaerotolerant Anaerobic Lactic Acid Bacterium from the Sheep Rumen and Pig Jejunum, and Emended Descriptions of Olsenella, Olsenella uli and Olsenella profusa. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S.; Chen, W.J.; Adeolu, M.; Chai, Y. Molecular Signatures for the Class Coriobacteriia and Its Different Clades; Proposal for Division of the Class Coriobacteriia into the Emended Order Coriobacteriales, Containing the Emended Family Coriobacteriaceae and Atopobiaceae Fam. Nov., and Eggerthellales Ord. Nov., Containing the Family Eggerthellaceae Fam. Nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 3379–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, M.A.; Banerjee, A.; Watson, T.F.; Wade, W.G. Molecular Analysis of the Microflora Associated with Dental Caries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 3023–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrani-Mougeot, F.K.; Paster, B.J.; Coleman, S.; Ashar, J.; Barbuto, S.; Lockhart, P.B. Diverse and Novel Oral Bacterial Species in Blood Following Dental Procedures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 2129–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogius-Kurikka, L.; Kassinen, A.; Paulin, L.; Corander, J.; Mäkivuokko, H.; Tuimala, J.; Palva, A. Sequence Analysis of Percent G+C Fraction Libraries of Human Faecal Bacterial DNA Reveals a High Number of Actinobacteria. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khachatryan, Z.A.; Ktsoyan, Z.A.; Manukyan, G.P.; Kelly, D.; Ghazaryan, K.A.; Aminov, R.I. Predominant Role of Host Genetics in Controlling the Composition of Gut Microbiota. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, J.D.; Scott, P.T.; Shephard, R.W.; Al Jassim, R.A.M. The Characterization of Lactic Acid Producing Bacteria from the Rumen of Dairy Cattle Grazing on Improved Pasture Supplemented with Wheat and Barley Grain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 1754–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leser, T.D.; Amenuvor, J.Z.; Jensen, T.K.; Lindecrona, R.H.; Boye, M.; Møller, K. Culture-Independent Analysis of Gut Bacteria: The Pig Gastrointestinal Tract Microbiota Revisited. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.; Jérôme, V.; Freitag, R.; Mayer, H.K. Diversity of the Resident Microbiota in a Thermophilic Municipal Biogas Plant. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 81, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yue, H.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Shen, J.; Hailili, G.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, X.; Pu, Y.; Song, H.; et al. Oral Microbiota Linking Associations of Dietary Factors with Recurrent Oral Ulcer. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casarin, R.C.V.; Saito, D.; Santos, V.R.; Pimentel, S.P.; Duarte, P.M.; Casati, M.Z.; Gonçalves, R.B. Detection of Mogibacterium timidum in Subgingival Biofilm of Aggressive and Non-Diabetic and Diabetic Chronic Periodontitis Patients. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2012, 43, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, Y.; Okuyama, T.; Araki, K.; Sekiguchi, K.; Watanabe, T.; Ohnishi, H. First Description of Lachnoanaerobaculum orale as a Possible Cause of Human Bacteremia. Anaerobe 2022, 73, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alauzet, C.; Aujoulat, F.; Lozniewski, A.; Ben Brahim, S.; Domenjod, C.; Enault, C.; Lavigne, J.-P.; Marchandin, H. A New Look at the Genus Solobacterium: A Retrospective Analysis of Twenty-Seven Cases of Infection Involving S. moorei and a Review of Sequence Databases and the Literature. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Feng, Q.; Wong, S.H.; Zhang, D.; Liang, Q.Y.; Qin, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhao, H.; Stenvang, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Metagenomic Analysis of Faecal Microbiome as a Tool towards Targeted Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Colorectal Cancer. Gut 2017, 66, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Manoil, D.; Belibasakis, G.N.; Kotsakis, G.A. Veillonellae: Beyond Bridging Species in Oral Biofilm Ecology. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 774115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Li, X.; Huang, I.-H.; Qi, F. Veillonella Catalase Protects the Growth of Fusobacterium nucleatum in Microaerophilic and Streptococcus gordonii-Resident Environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01079-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, P.I.; Zilm, P.S.; Rogers, A.H. Fusobacterium nucleatum Supports the Growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis in Oxygenated and Carbon-Dioxide-Depleted Environments. Microbiology 2002, 148, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodorea, C.F.; Diven, S.; Hendrawan, D.; Djais, A.A.; Bachtiar, B.M.; Widyarman, A.S.; Seneviratne, C.J. Characterization of Oral Veillonella Species in Dental Biofilms in Healthy and Stunted Groups of Children Aged 6–7 Years in East Nusa Tenggara. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacali, C.; Vulturar, R.; Buduru, S.; Cozma, A.; Fodor, A.; Chiș, A.; Lucaciu, O.; Damian, L.; Moldovan, M.L. Oral Microbiome: Getting to Know and Befriend Neighbors, a Biological Approach. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, A.; Folini, E.; Cosola, S.; Russo, G.; Scribante, A.; Gallo, S.; Stablum, G.; Menchini Fabris, G.B.; Covani, U.; Genovesi, A. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Probiotics Domiciliary Protocols for the Management of Periodontal Disease, in Adjunction of Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy (NSPT): A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, M.T.; De Oliveira, F.L.; Salgaço, M.K.; Mesa, V.; Sartoratto, A.; Duailibi, K.; Raimundo, B.V.B.; Ramos, W.S.; Sivieri, K. Restoring Balance: Probiotic Modulation of Microbiota, Metabolism, and Inflammation in SSRI-Induced Dysbiosis Using the SHIME® Model. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ORAL MICROBIOTA | |||||||

| Treatment | |||||||

| Species | p-Value | FDR | T0 | T1 | - | - | LDAscore |

| Gemella haemolysans | 0.004532 | 0.28683 | 2495.4 | 315.2 | - | - | 3.04 |

| Gemella sp. | 0.0068622 | 0.28683 | 16,557 | 7753 | - | - | 3.64 |

| Bacillus sp. | 0.010123 | 0.28683 | 12,284 | 6795.7 | - | - | 3.44 |

| Actinomyces viscosus | 0.024968 | 0.41875 | 4641.7 | 10,855 | - | - | −3.49 |

| Unclassified Bacillota | 0.029559 | 0.41875 | 28,275 | 20,852 | - | - | 3.57 |

| Unclassified Bacteria | 0.029559 | 0.41875 | 117,490 | 100,810 | - | - | 3.92 |

| Unclassified Sphingomonadaceae | 0.034806 | 0.42264 | 265.24 | 1964.3 | - | - | −2.93 |

| Granulicatella sp. | 0.040946 | 0.43505 | 14724 | 6799.1 | - | - | 3.6 |

| Streptococcus oralis | 0.047913 | 0.45251 | 1536.5 | 354.75 | - | - | 2.77 |

| FMPS | |||||||

| Species | p-Value | FDR | A | B | C | D | LDAscore |

| Streptococcus anginosus | 0.0025017 | 0.091112 | 170.68 | 1737.9 | 11,440 | 11,686 | 3.76 |

| Peptostreptococcus sp. | 0.00272 | 0.091112 | 1762.7 | 220.04 | 18,882 | 12,141 | 3.97 |

| Mogibacterium vescum | 0.0041699 | 0.091112 | 259.11 | 1467.5 | 933.09 | 4185 | 3.29 |

| Peptostreptococcus stomatis | 0.0042876 | 0.091112 | 5234.8 | 156.33 | 24,490 | 22,427 | 4.09 |

| Megasphaera micronuciformis | 0.0094057 | 0.1599 | 61.924 | 5424.6 | 601.57 | 691.99 | 3.43 |

| Olsenella phocaeensis | 0.015309 | 0.19365 | 2303.7 | 553.1 | 5203.9 | 4735 | 3.37 |

| Streptococcus intermedius | 0.015947 | 0.19365 | 53,980 | 52,952 | 30,232 | 8520.1 | 4.36 |

| Mogibacterium timidum | 0.02066 | 0.21952 | 159.35 | 126.54 | 4012.1 | 1604.9 | 3.29 |

| TM7 phylum sp oral | 0.023401 | 0.22101 | 24,809 | 9438 | 54,974 | 61,458 | 4.42 |

| Solobacterium sp. | 0.030214 | 0.23557 | 1687.4 | 2205.9 | 3168.4 | 7259.9 | 3.45 |

| Actinomyces massiliensis | 0.030513 | 0.23557 | 1701.8 | 9631.9 | 4266.1 | 3781 | 3.6 |

| Unclassified Atopobiaceae | 0.033257 | 0.23557 | 1452.9 | 696.03 | 3241.2 | 2826.6 | 3.11 |

| Actinomyces israelii | 0.042092 | 0.25381 | 3614 | 142.23 | 547.97 | 968.23 | 3.24 |

| Veillonella dispar | 0.043343 | 0.25381 | 26,994 | 74,435 | 11,232 | 10,832 | 4.5 |

| Lachnoanaerobaculum saburreum | 0.04479 | 0.25381 | 2764.5 | 711.87 | 5135.4 | 5977.7 | 3.42 |

| FMBS | |||||||

| Species | p-Value | FDR | A | B | C | D | LDAscore |

| Streptococcus anginosus | 0.00020954 | 0.017811 | 1041.4 | 11,573 | - | - | −3.72 |

| Peptostreptococcus sp. | 0.00074545 | 0.031682 | 905.66 | 15,252 | - | - | −3.86 |

| Peptostreptococcus stomatis | 0.0012006 | 0.032611 | 2413.4 | 23,380 | - | - | −4.02 |

| Olsenella phocaeensis | 0.0019016 | 0.032611 | 1331.2 | 4951.4 | - | - | −3.26 |

| Mogibacterium timidum | 0.0019183 | 0.032611 | 141.12 | 2715.9 | - | - | −3.11 |

| TM7 phylum sp oral | 0.0029623 | 0.041966 | 16269 | 58,465 | - | - | −4.32 |

| Unclassified Atopobiaceae | 0.0045388 | 0.055114 | 1032.4 | 3017.9 | - | - | −3 |

| Streptococcus intermedius | 0.0068405 | 0.070943 | 53409 | 18541 | - | - | 4.24 |

| Olsenella sp. | 0.0083279 | 0.070943 | 344.4 | 999.39 | - | - | −2.52 |

| Veillonella dispar | 0.0083462 | 0.070943 | 53,350 | 11,017 | - | - | 4.33 |

| Eubacterium infirmum | 0.012274 | 0.080251 | 5130.4 | 15,496 | - | - | −3.71 |

| Solobacterium sp. | 0.012274 | 0.080251 | 1975.5 | 5371.5 | - | - | −3.23 |

| Solobacterium moorei | 0.012274 | 0.080251 | 5215.3 | 15,359 | - | - | −3.71 |

| Lachnoanaerobaculum saburreum | 0.014793 | 0.089817 | 1624.1 | 5589 | - | - | −3.3 |

| Mogibacterium vescum | 0.021231 | 0.12031 | 930.41 | 2684.1 | - | - | −2.94 |

| Eubacterium sp. | 0.025282 | 0.13431 | 548.56 | 1442.9 | - | - | −2.65 |

| Veillonella sp. | 0.029985 | 0.14993 | 9099.8 | 2423.4 | - | - | 3.52 |

| Lachnoanaerobaculum sp. | 0.035421 | 0.16727 | 1195.1 | 3186.7 | - | - | −3 |

| Unclassified Streptococcaceae | 0.048844 | 0.1977 | 1388.2 | 765.94 | - | - | 2.49 |

| Unclassified Eubacteriales | 0.048844 | 0.1977 | 20448 | 31,240 | - | - | −3.73 |

| Unclassified Erysipelotrichaceae | 0.048844 | 0.1977 | 687.05 | 1939.1 | - | - | −2.8 |

| GUT MICROBIOTA | |||||||

| Treatment | |||||||

| Species | p-Value | FDR | T0 | T1 | - | - | LDAscore |

| Parabacteroides sp. | 0.00015705 | 0.013686 | 418.38 | 2088.9 | - | - | −2.92 |

| Bacteroides sp. | 0.00028512 | 0.013686 | 767.94 | 5919.5 | - | - | −3.41 |

| Phocaeicola sp. | 0.00050654 | 0.016209 | 1848 | 9764.7 | - | - | −3.6 |

| Unclassified Lachnospiraceae | 0.0019397 | 0.046553 | 145,830 | 105,380 | - | - | 4.31 |

| Alistipes sp. | 0.0045711 | 0.082543 | 513.29 | 3287.1 | - | - | −3.14 |

| Unclassified Eubacteriales | 0.005159 | 0.082543 | 67824 | 44192 | - | - | 4.07 |

| Intestinibacter bartlettii | 0.0065017 | 0.089166 | 1347.8 | 658.69 | - | - | 2.54 |

| Intestinibacter sp. | 0.010165 | 0.10843 | 1677.1 | 813.07 | - | - | 2.64 |

| Blautia luti | 0.010165 | 0.10843 | 4365.7 | 1911.3 | - | - | 3.09 |

| Unclassified Bacillota | 0.028366 | 0.27231 | 22268 | 13051 | - | - | 3.66 |

| Unclassified Bacteria | 0.034294 | 0.29929 | 240,380 | 308,880 | - | - | −4.53 |

| Unclassified Peptostreptococcaceae | 0.04125 | 0.33 | 8057 | 4639.9 | - | - | 3.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bona, E.; Cavarra, F.; Caramaschi, A.; Massa, N.; Bazzano, C.; Patini, R.; Rocchetti, V.; Rimondini, L. Impact of an Essential-Oil-Based Oral Rinse on Oral and Gut Microbiota Diversity: A Pilot Study. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120251

Bona E, Cavarra F, Caramaschi A, Massa N, Bazzano C, Patini R, Rocchetti V, Rimondini L. Impact of an Essential-Oil-Based Oral Rinse on Oral and Gut Microbiota Diversity: A Pilot Study. Microbiology Research. 2025; 16(12):251. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120251

Chicago/Turabian StyleBona, Elisa, Francesco Cavarra, Alice Caramaschi, Nadia Massa, Chiara Bazzano, Romeo Patini, Vincenzo Rocchetti, and Lia Rimondini. 2025. "Impact of an Essential-Oil-Based Oral Rinse on Oral and Gut Microbiota Diversity: A Pilot Study" Microbiology Research 16, no. 12: 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120251

APA StyleBona, E., Cavarra, F., Caramaschi, A., Massa, N., Bazzano, C., Patini, R., Rocchetti, V., & Rimondini, L. (2025). Impact of an Essential-Oil-Based Oral Rinse on Oral and Gut Microbiota Diversity: A Pilot Study. Microbiology Research, 16(12), 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120251