1. Introduction

The shifting interplay between mobility, media, and identity has created new, often invisible actors within the global tourism system. Among them, digital nomads—location-independent workers who integrate long-term travel with remote professional activity—have emerged as mobile, self-sustaining micro-communities that blur the lines between resident, tourist, and influencer [

1,

2]. Their mobility patterns, lifestyle choices, and digital narratives are already transforming how destinations are consumed, imagined, and communicated. Yet, while their socio-economic impact on cities and host communities is increasingly studied [

3,

4], their role in shaping destination brands remains under-theorized and largely unacknowledged by formal tourism governance structures.

This paper makes the case that digital nomads are not just consumers of destinations—they are

unintentional brand ambassadors whose decentralized, authentic, and persistent digital output plays a significant role in shaping perceptions of place. Unlike traditional influencers, whose promotional content is contractual, curated, and transient, digital nomads generate location-based narratives organically and consistently, through blogs, vlogs, social media, and peer communication. These outputs, though not strategically framed, often resonate more deeply with audiences due to their perceived authenticity, spontaneity, and insider perspective [

5]. Their cumulative influence represents a form of ambient marketing: subtle, sustained, and often more effective than orchestrated campaigns.

Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs), however, remain slow to recognize this shift. Current marketing strategies tend to privilege formal influencer partnerships, high-visibility media campaigns, and top-down branding initiatives [

6]. These approaches, while effective in some contexts, increasingly overlook the decentralized dynamics of travel inspiration in a digital-first world. The result is a strategic blind spot: a growing group of globally mobile individuals who, without any formal incentive or coordination, are broadcasting destinations to global audiences—often more credibly than paid spokespeople.

This research addresses that blind spot. It introduces and develops the concept of the unintentional brand ambassador, defined as an individual whose digital representations of place contribute meaningfully to destination image formation, despite the absence of any deliberate promotional intent on behalf of a specific destination or tourism organization (e.g., no DMO contract, hosted trip, or formal promotional brief). “Unintentional”, in this sense, refers to the lack of destination-specific promotional goals rather than to an absence of broader self-presentation or audience-building ambitions. We argue that digital nomads, by virtue of their prolonged stays, their embeddedness in local cultures, and their habitual digital storytelling, are uniquely positioned to influence how places are perceived by others—especially peers within their extended digital networks.

To examine this phenomenon, we employ a multi-method, multi-study research design that integrates three strands of empirical inquiry:

Study 1 is a quantitative survey that measures how exposure to digital nomad content influences destination image, perceived authenticity, and travel intentions.

Study 2 conducts controlled experimental comparison of digital nomad versus influencer-generated travel content, focusing on differences in trust, authenticity, and persuasiveness.

Study 3 presents findings from semi-structured depth interviews with senior DMO professionals to assess institutional awareness, engagement strategies and perceived barriers in working with digital nomads.

This study makes three key contributions to tourism research and practice. First, it refines the theoretical boundaries of brand ambassadorship by distinguishing between intentional and emergent forms of influence within user-generated media ecologies. Second, it advances methodological approaches to tourism marketing by triangulating survey data, digital content analysis, and expert interviews—a design rarely applied to the study of mobile digital workers. Third, it offers timely and practical insights for tourism policy: how to engage with non-contracted, non-commercial actors without co-opting or instrumentalizing their authenticity.

In an era where travel decisions are increasingly shaped by casual posts, peer stories, and lifestyle narratives rather than official advertisements [

7], recognizing the role of digital nomads in the informal marketing ecosystem is both conceptually overdue and strategically urgent. As the boundaries between work, travel, and content creation continue to collapse, tourism researchers and managers alike must expand their frameworks to include the ambient, networked, and often unintentional agents of place promotion.

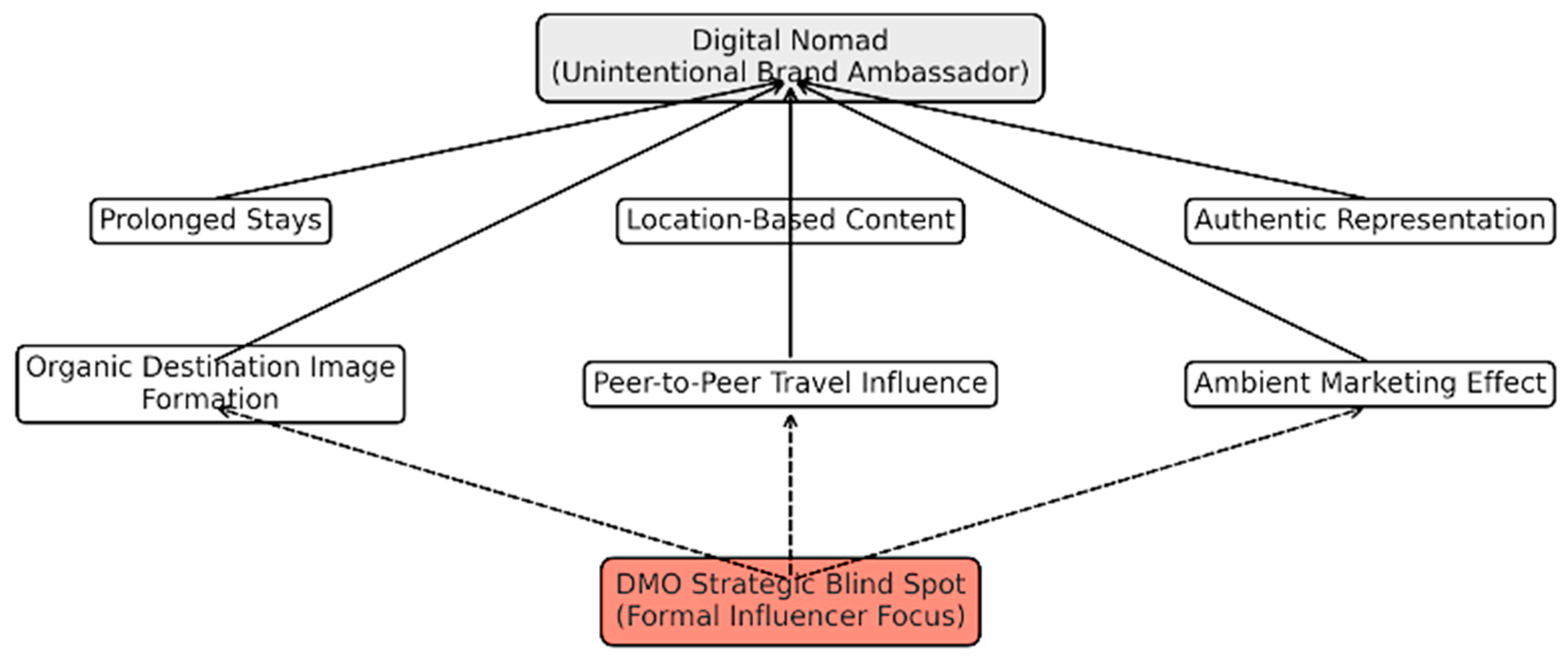

To synthesize these arguments and guide the subsequent empirical analyses, a conceptual model is proposed that positions digital nomads as unintentional brand ambassadors operating within decentralized tourism media ecologies (

Figure 1). The model outlines how digital nomads, by virtue of prolonged stays, authentic engagement with place, and habitual content production, contribute to three key outcomes: (1) organic destination image formation, (2) peer-to-peer influence on travel behavior, and (3) an ambient influence marketing effect that occurs without formal endorsement or sponsorship. Importantly, the model highlights a strategic disconnect: while these actors contribute materially to destination branding, they remain largely invisible to Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs), which continue to prioritize traditional influencer partnerships. This conceptual framework underpins the multi-method investigation reported here and serves as a foundation for developing new theoretical and policy insights into organic forms of destination marketing in the digital era.

Ambient influence is the unprompted, passively encountered impact of unsponsored, life-as-lived creator content on destination-related cognitions and intentions, operating primarily through perceived authenticity and place image rather than through explicit persuasion. It is distinct from conventional eWOM/UGC in its low persuasion salience and ongoing narrative continuity, and from mere exposure in that effects depend on authenticity and identification cues, not just contact frequency. Ambient influence is most likely when audiences repeatedly come across nomad content in their regular feeds, without calls-to-action or disclosures, and outside platform contexts associated with advertising. Hence, we use “ambient influence” to denote the cumulative impact of repeated, non-promotional lifestyle content on how audiences perceive a destination and whether they intend to visit it. In our framing, three antecedents make this influence likely to emerge: (1) serialized exposure to everyday posts rather than one-off promos; (2) authenticity signals—what we term “calibrated amateurism,” such as handheld footage, unpolished captions, and situational candor; and (3) embeddedness in local routines and micro-details (e.g., commute clips, markets, costs). These antecedents operate through three mechanisms: mere exposure and growing familiarity, relational trust rooted in perceived independence from sponsorship, and narrative coherence over time as fragmented posts accumulate into a lived storyline. The primary outcomes are shifts in destination image (cognitive and affective) and intention to visit, with secondary peer diffusion via saves/shares that extends reach beyond the creator’s immediate audience. To support operationalization and replication, we highlight practical proxies that platforms and DMOs can track: content longevity, save-rate, repeat impressions, creator network centrality, and comment quality.

This model illustrates how digital nomads—through prolonged stays, authentic representation, and location-based content creation—contribute to organic destination marketing without formal promotional intent. Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on prior work on destination image, influencer marketing, and eWOM.

To explore the role of digital nomads as unintentional contributors to destination marketing, this study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: To what extent do digital nomads influence others’ perceptions of destinations through their online presence?

RQ2: How does the influence of digital nomads compare with traditional influencer marketing in terms of perceived trust, authenticity, and audience impact?

RQ3: What strategies, if any, are Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs) employing to recognize or leverage the influence of digital nomads?

These questions guide a multi-method investigation of digital nomads’ symbolic and strategic value within contemporary tourism ecosystems, as outlined in the conceptual framework presented in

Figure 1. Although these questions are broad, they are accompanied in

Section 2 (Literature Review) by four specific, directional propositions (P1–P4) derived from the conceptual model, which we test as formal hypotheses in the quantitative components of the study (Studies 1 and 2).

The three research questions articulated in this study respond directly to critical gaps in the existing tourism and marketing literature. While prior studies have explored digital nomadism from economic, spatial, and lifestyle perspectives [

3,

4,

8], few have examined the symbolic and branding implications of this group’s persistent, place-based digital storytelling. RQ1 breaks new ground by empirically examining the extent to which digital nomads shape destination image outside formal marketing structures. RQ2 addresses a conceptual blind spot in influencer marketing literature by comparing intentional, contract-driven influence with ambient, unintentional influence—an under-theorized distinction. RQ3 is especially novel in its focus on institutional response, exploring how (and whether) Destination Marketing Organizations are adapting to the decentralized, peer-driven dynamics of digital nomad content. Together, these questions position this study at the intersection of tourism branding, digital labor, and participatory media—an area still underexplored in both theoretical and applied tourism research.

Beyond tourism branding, this work connects to electronic commerce by situating destination choice within platform-mediated decision funnels. We propose that ambient influence contributes upstream (awareness/consideration) and interacts with downstream performance marketing via conversion externalities (e.g., save-rates, session depth, revisit windows). This frames digital nomad UGC as a non-contracted, high-trust signal within social commerce ecosystems and raises governance questions about disclosure, algorithmic discovery, and attribution.

2. Literature Review

To position our core construct of ambient influence,

Table 1 contrasts three adjacent forms of influence: (a) sponsored influencer campaigns, (b) conventional eWOM/UGC, and (c) unsponsored, serialized “life-as-lived” content produced by digital nomads. Ambient influence (our construct) refers to the cumulative, low-salience persuasive effect that arises when audiences repeatedly encounter unsponsored, everyday nomad content in their feeds, outside explicit advertising contexts.

This contrast frames the subsequent review and the propositions tested in Studies 1–2. Building on the conceptual distinctions in

Table 1, we state four propositions (P1–P4) that serve as formal hypotheses for the quantitative components of the research and map directly onto Studies 1 and 2.

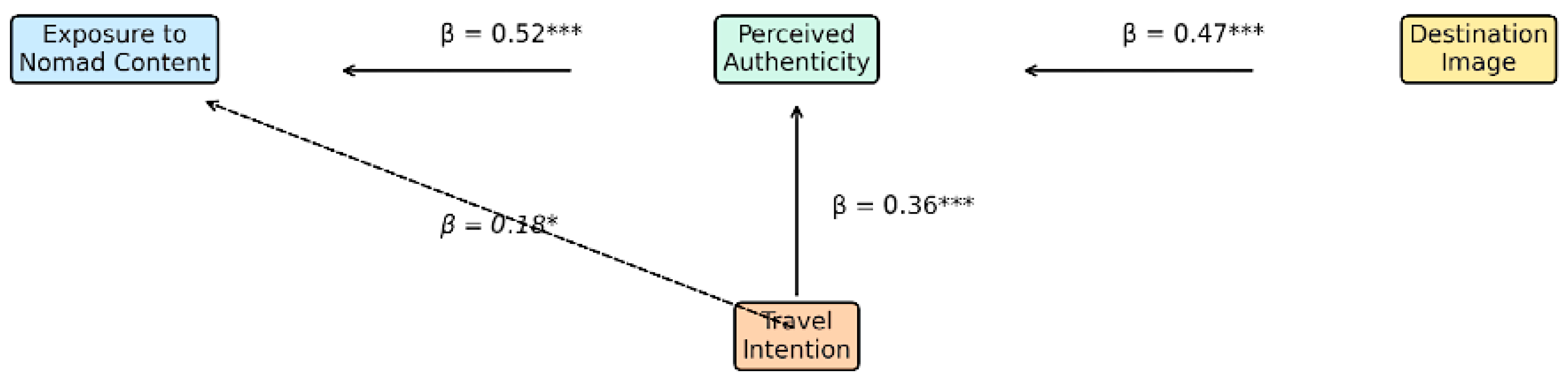

P1 (Exposure → Authenticity). Greater ambient exposure to digital-nomad content is associated with higher perceived authenticity of destination portrayals. (Study 1).

P2 (Authenticity → Image). Perceived authenticity positively predicts destination image/appeal. (Study 1).

P3 (Sequential mediation). Ambient exposure has an indirect positive association with visit intention via authenticity → destination image. (Study 1).

P4 (Persuasion-salience moderation). Making commercial intent salient (sponsored influencer content vs. ambient nomad content) reduces authenticity and trust, attenuating downstream intention. (Study 2 causal test)

P1–P3 specify the mediated pathway that differentiates ambient influence from mere exposure; P4 defines a boundary condition based on persuasion salience.

2.1. Digital Nomadism as Lifestyle, Labor, and Liminality

Digital nomadism has shifted from fringe trend to emblem of the post-pandemic work ethos. Promoted across social media, digital platforms, and coworking spaces, it markets a seductive formula: mobility without instability, productivity without place. This vision resonates with broader neoliberal discourses of flexibility, autonomy, and self-branding [

1,

2]. But digital nomadism is not just a lifestyle—it is a labor model, an urban force, and a form of cultural production.

At a structural level, digital nomadism reflects the precarity and fluidity of platform capitalism. Scholars have mapped its effects on housing markets [

8], local labor dynamics [

4], and the urban fabric of popular nomad hubs like Chiang Mai, Lisbon, or Canggu [

3,

9]. Its participants often operate outside formal employment systems, working as freelancers, content creators, or remote staff while moving across jurisdictions. This mode of living raises questions not only about taxation and infrastructure but about whose mobility is possible—and whose is policed [

10].

Less attention, however, has been paid to digital nomads’

symbolic power—their capacity to frame and narrate the places they inhabit. Through daily digital output—Instagram reels, blog entries, vlogs, podcasts—nomads shape imaginaries of place. These media outputs are not simply personal reflections; they are performative representations that feed into larger circuits of tourism desire and branding [

11,

12].

Digital nomads operate as

locative media nodes—mobile yet grounded transmitters of place-based narratives. Their content is algorithmically distributed, often optimized for discovery via search engines, hashtags, or platform trends. While not produced for marketing, it functions like it: conveying messages about safety, affordability, climate, vibe, and digital infrastructure. The power of this content lies in its perceived authenticity—what Abidin calls “calibrated amateurism”—and its lack of commercial framing [

13]. It feels unfiltered, even if it is anything but.

Their liminal status further amplifies this influence. Digital nomads live in the in-between: not quite tourists, not quite locals. This ambiguity grants them a kind of narrative authority: they are embedded enough to be insightful, yet transient enough to remain relatable. Reichenberger frames this duality as performative—nomads must

appear spontaneous and immersed [

14], even as their routines involve careful curation of content, image, and narrative.

But the story of digital nomadism cannot be separated from privilege. While often framed as borderless, the ability to live and work remotely is stratified by passport power, income security, race, and language [

15,

16]. Western nomads enjoy access to places that citizens of the Global South may not, and many remain detached from the civic, economic, and social responsibilities of the locales they occupy [

17]. The “freedom” to roam is built on complex structures of global inequality.

At the same time, the apparent frictionless mobility projected in digital nomad narratives is underpinned by significant structural privileges and exclusions. The ability to move between “affordable” destinations while earning a remote income in stronger currencies depends on access to high-demand digital skills, stable client or employer relationships, and the financial buffer to absorb mobility risks. It is also conditioned by passport power, visa regimes and border practices that afford far greater freedom of movement to citizens of the Global North than to those from the Global South, and by racialized and gendered safety concerns that make some bodies more vulnerable in transit and in public space than others [

10,

15,

16]. Rising demand from relatively affluent nomads can further amplify housing pressure, spatial segregation and the creation of “nomad enclaves” that coexist uneasily with local livelihoods [

3,

4,

8]. Rather than treating digital nomadism as a universal lifestyle option, we therefore conceptualize it as a privileged mobility regime embedded in wider circuits of platform capitalism and mobility justice [

10]. This critical framing is important for interpreting nomads’ branding influence: their aspirational stories are powerful precisely because they are produced from structurally advantaged positions that many potential travelers and most residents cannot easily occupy.

Despite this, digital nomads remain remarkably effective—and largely unrecognized—agents of

destination branding. Unlike influencers, who produce transactional content tied to campaigns and contracts, nomads offer

ambient marketing: organic, longitudinal, and subtle. Their posts are not endorsements, but they influence. Their stories are not ads, but they stick. Over time, this steady flow of content can meaningfully alter a destination’s digital footprint—especially among other nomads or remote workers seeking similar pathways [

18].

Thus, digital nomads serve as unintentional brand ambassadors—not because they are paid to promote, but because their lifestyles require them to document. Their hybridity—rooted yet mobile, commercial yet casual—makes them ideally positioned to shape how destinations are imagined and pursued.

Some digital nomads partially commercialize their presence (e.g., affiliate links, personal products, or courses) and actively cultivate a personal brand or audience. In this article, unintentional brand ambassador status is therefore defined at the level of destination-specific intent: it describes actors who, in the focal content, have no contractual destination promotion (no DMO/industry contract, no paid familiarization trip, no destination brief) and no explicit goal to advertise a particular place. Creators who occasionally accept sponsorships remain within scope only when the analyzed or experimental stimuli are unsponsored; content with destination contracts is classified as sponsored influencer material. This boundary preserves construct validity while still recognizing that many nomads hold broader, intentional goals around visibility, self-branding, or generic monetization.

Conceptually, this points to a spectrum of intentionality rather than a simple binary. At one end are highly scripted, campaign-based influencers whose content is explicitly designed to promote a destination; at the other are nomads whose primary intention is to sustain a lifestyle or grow a loosely defined personal brand, with destination promotion emerging as a by-product of narrating everyday life. In between sit hybrid cases—such as “proto-influencers” who optimize thumbnails, hashtags, or posting schedules with an eye to future sponsorships, yet still produce unsponsored, life-as-lived narratives. Our focus on unintentional ambassadorship foregrounds these layered forms of intent: a nomad may deliberately grow an audience or monetize expertise, but the branding effect on place remains emergent, ambient, and only partially anticipated.

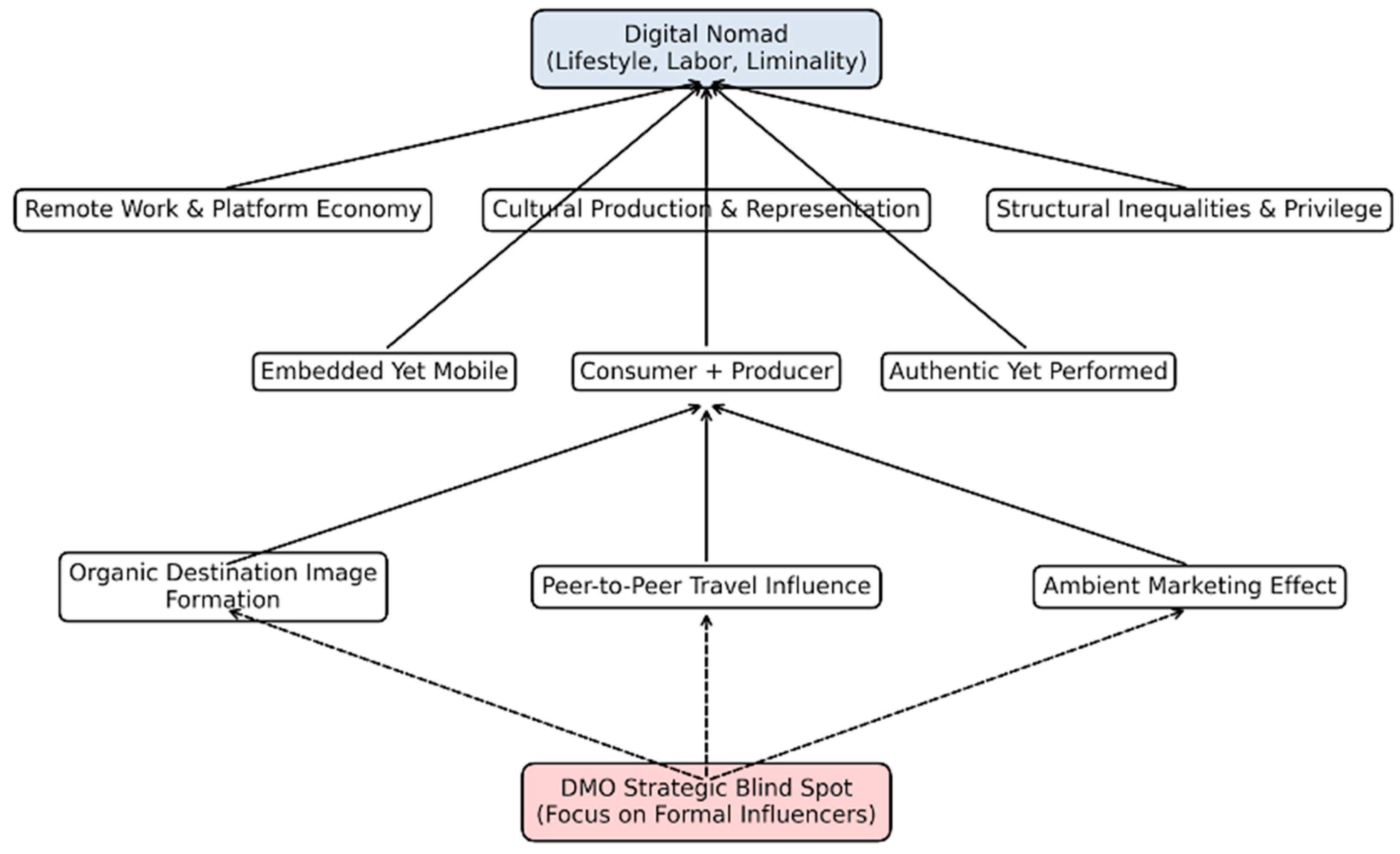

This conceptual framing of digital nomadism—as simultaneously a form of labor, lifestyle, and liminal social position—feeds directly into their emerging role in organic destination branding. Their lived experiences, embedded media production, and dual positionality as both insiders and outsiders enable them to construct compelling, credible narratives of place. These characteristics, while not produced with marketing intent, often result in tangible branding outcomes: shaping how destinations are perceived, circulated, and desired.

Figure 2 visually synthesizes these relationships, mapping how structural enablers and representational behaviors of digital nomads contribute to peer influence, image formation, and ambient marketing—effects that remain largely unacknowledged within traditional Destination Marketing Organization (DMO) frameworks.

This diagram illustrates how digital nomadism—understood through the lenses of lifestyle, labor, and liminality—feeds into unintentional destination branding processes. Rooted in remote work structures, cultural production, and structural privilege, digital nomads occupy a hybrid role that enables authentic yet performative representation of place. Source: Authors’ own illustration, drawing on research on digital nomadism, mobility and locative media.

This multi-dimensional framing of digital nomadism—as a fusion of labor, lifestyle, and liminality—offers critical insight into how these individuals produce and circulate place-based narratives. Their content, while not promotional in intent, plays a significant role in constructing perceptions of destination livability, desirability, and accessibility. As visualized in

Figure 1, these characteristics contribute to unintentional yet impactful destination branding outcomes, including image formation, peer influence, and ambient marketing. This perspective directly informs Research Question 1, which explores the extent to which digital nomads shape destination perceptions through their digital presence.

2.2. Reframing Destination Image: From Control to Co-Creation

The concept of destination image has long held a central place in tourism research, recognized as a key determinant of tourist motivation, decision-making, and satisfaction [

19,

20,

21]. Traditionally, destination image was viewed as something crafted by tourism boards and consumed by travelers—a unidirectional, top-down communication model often categorized into

induced (i.e., marketer-driven) and

organic (i.e., media or experience-driven) sources [

22]. This distinction, however, is increasingly outdated in the age of participatory media, where user-generated content (UGC) not only reflects but actively

constructs the destination image in real time [

23].

With the rise in digital platforms and mobile media, destination image has shifted from a static brand to a dynamic, co-produced narrative [

24,

25]. Travelers are no longer just consumers of place—they are

producers of place meaning. This transition from

image management to

image negotiation represents a fundamental challenge for traditional Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs), which often still prioritize message control over message engagement [

26]. In this evolving context, the role of digital nomads becomes particularly salient.

Digital nomads, by virtue of their prolonged stays and immersive local engagement, produce nuanced representations of place that transcend conventional tourist imagery. Rather than spotlighting iconic attractions, their content often showcases daily routines, overlooked neighborhoods, remote cafés, or coworking hubs—spaces typically absent from official marketing narratives but highly relevant to other remote workers, long-term travelers, and lifestyle migrants [

12,

27]. In doing so, they participate in what could be termed

locational storytelling—a process that enhances the depth and authenticity of destination imagery through experiential, narrative-driven media [

28].

Importantly, these narratives circulate widely beyond their initial audience, aided by platform algorithms, hashtags, and the virality of aspirational lifestyle content. A blog post on “why I moved to Medellín” or a YouTube vlog about “a day in the life of a nomad in Tbilisi” not only informs but also subtly brands these destinations in ways that formal campaigns may struggle to match. The emotional tone, perceived spontaneity, and lived credibility of such content form part of what Urry and Larsen describe as the “tourist gaze 3.0”—a gaze increasingly filtered through peers, influencers [

11], and algorithmic feeds rather than official brochures or guidebooks [

29].

This shift also raises questions of

voice and visibility. Who gets to co-create destination image? Digital nomads—typically young, Western, upwardly mobile individuals—are disproportionately visible in shaping online narratives of place. Their dominance in the UGC landscape can lead to a form of representational monoculture, where the “desirable” version of a place is flattened to reflect the needs, values, and esthetics of a narrow demographic [

15]. As a result, place branding via UGC risks not only reinforcing existing social inequalities but also marginalizing local voices and alternative perspectives [

17].

Nonetheless, the impact of digital nomads on destination image formation is both significant and under-acknowledged in tourism scholarship. Their content operates as

ambient branding—slow, persistent, and organic. Unlike influencer campaigns, which are event-driven and time-bound, nomad-produced content contributes to an evolving, decentralized ecosystem of perception. In this environment, branding is no longer a campaign but a conversation—one in which digital nomads, intentionally or not, are increasingly central [

30].

The dynamics outlined in this section directly reinforce the conceptual structure presented in

Figure 1, where digital nomads—through their sustained content production and everyday narrative practices—emerge as key contributors to destination image formation, peer-to-peer influence, and ambient marketing effects. Their ability to shape place perception without strategic intent challenges traditional models of brand ambassadorship and prompts a reconsideration of how destination value is generated and circulated. This reframing directly informs our investigation of how digital nomads function as

unintentional brand ambassadors and guides our first and second research questions: (1) to what extent do digital nomads influence others’ perceptions of destinations through their online presence, and (2) how does this organic influence compare with traditional influencer marketing in terms of trust, authenticity, and reach?

The shift from top-down image management to collaborative, user-driven image-making demands a more flexible understanding of how destination meaning is constructed—and by whom. Digital nomads, through their embeddedness and serialized storytelling, participate in a form of decentralized branding that traditional marketing strategies often overlook. As shown in

Figure 1, their contribution to organic image formation represents a potent, under-recognized influence. This directly supports Research Questions 1 and 2, which explore how such informal content shapes destination perceptions and how it compares with more structured marketing efforts.

2.3. Influencer Marketing: Authenticity and Intentionality in the Digital Age

Influencer marketing has become a dominant strategy in contemporary tourism promotion, rooted in the logic that trusted individuals with large followings can shape perceptions, drive desire, and stimulate travel behaviors [

31]. This model hinges on a deliberate, contractual relationship: destinations partner with influencers to curate specific representations of place, framed by promotional goals, campaign timelines, and audience engagement metrics. However, as social media matures and audiences become more media literate, the limits of this model are increasingly visible. A growing body of research highlights a

trust gap: while influencers offer reach, their association with commercial incentives often undermines the perceived authenticity of their content [

32,

33].

Authenticity, once an esthetic quality, has become a strategic asset in influencer discourse. Influencers deploy “curated imperfection” and “strategic vulnerability” to appear relatable and trustworthy, a phenomenon Abidin terms

calibrated amateurism [

13]. Yet even this performative authenticity is increasingly recognized as stylized and monetized, particularly by younger demographics who seek connection over curation [

34]. In this landscape, digital nomads present a compelling contrast: they generate destination content not through contracts, but through routine. Their influence is ambient, not activated. They promote without promoting.

This distinction between intentional and unintentional influence is a critical conceptual boundary. Influencers are paid to direct attention; digital nomads generate attention as a by-product of lifestyle documentation. Their posts—detailing daily life in Budapest, visa runs in Yerevan, or cost-of-living hacks in Hanoi—are not endorsements in the formal sense, but they nonetheless shape desirability and decision-making among peers. Their embedded, narrative-rich content often carries more weight than branded campaigns precisely because it lacks overt persuasion.

Moreover, digital nomads tend to reach

hyper-specific,

trust-based audiences—communities of aspiring remote workers, slow travelers, or location-independent entrepreneurs. These peer networks often value long-form, process-driven content (e.g., blog series, YouTube episodes) over high-polish, single-shot influencer posts [

27]. Nomads build credibility over time, not through virality but through presence and repetition. Their content is perceived as grounded in lived experience, not promotional obligation—a distinction that may explain why digital nomad content is often cited, shared, and saved by those seeking practical insights rather than inspiration alone.

However, nomads are not exempt from performance. Their content is also curated, often aspirational, and sometimes monetized indirectly through affiliate links, sponsorships, or digital products. The difference lies in

intentionality and

framing: digital nomads rarely brand themselves as destination marketers, yet their influence on place perception can rival or exceed that of formal influencers [

35]. This paradox complicates assumptions about who acts as a brand ambassador, how influence circulates, and what counts as “marketing” in a platform-driven media landscape.

This discussion directly informs the conceptual distinction between formal influencers and unintentional ambassadors, captured in

Figure 1. It also lays the foundation for our second and third research questions: How does the influence of digital nomads compare to that of formal influencers in terms of trust, reach, and impact—and how are these dynamics understood or overlooked by Destination Marketing Organizations?

The contrast between formal influencer marketing and the informal, ambient influence of digital nomads is central to the conceptual structure illustrated in

Figure 1. While traditional influencers represent the intentional, campaign-driven model of destination branding, digital nomads operate in a more decentralized and organic fashion, shaping perceptions of place through continuous, narrative-driven engagement. This distinction is key to understanding how different forms of content carry different levels of authenticity and trust. Our model explicitly highlights this gap between formal and informal influence, emphasizing the strategic blind spot that occurs when DMOs prioritize contractual partnerships over emergent, peer-based influence. These insights guide our second and third research questions, which probe how digital nomad content compares with influencer marketing in perceived effectiveness and how DMOs respond—or fail to respond—to this evolving media ecology.

While the rise in digital nomads as informal content producers disrupts conventional marketing boundaries, it also exposes a critical institutional gap: most DMOs continue to rely on structured influencer campaigns, overlooking the diffuse yet potent influence of digital nomads. This oversight raises strategic questions about how tourism boards define, detect, and engage with new forms of organic place promotion. As informal influence becomes increasingly central in shaping destination perception—particularly among younger, digital-native travelers—understanding how, or whether, DMOs are adapting becomes essential. This leads to the third research question: What strategies, if any, are Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs) employing to recognize or leverage the influence of digital nomads?

The insights from this section further clarify the conceptual distinction illustrated in

Figure 1, where digital nomads operate outside the formal, contractual frameworks typical of influencer marketing, yet still exert meaningful influence through trusted, narrative-rich content. Their unintentional ambassadorship stands in contrast to the intentional, curated messaging of traditional influencers—highlighting a gap in how destinations are marketed and understood. This framing advances the understanding of Research Questions 2 and 3, which examine how digital nomads’ influence compares with formal influencer campaigns in terms of reach, trust, and perceived authenticity, and how Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs) recognize or overlook these dynamics.

2.4. Word-of-Mouth, Peer Networks, and Perceived Authenticity

The role of word-of-mouth (WOM) in tourism decision-making has been extensively researched [

36], with its digital extension—electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM)—now a cornerstone of travel behavior research [

37,

38]. At the core of its efficacy lies the assumption that peer-generated content is perceived as more authentic, personal, and trustworthy than institutionally produced messages. The shift from top-down, marketer-controlled narratives to horizontal, user-led storytelling aligns with broader transformations in consumer culture, where trust is increasingly negotiated through perceived similarity and lived experience rather than brand authority [

24].

In the specific case of digital nomads, this dynamic acquires a new intensity. These mobile professionals, whose lifestyles straddle leisure and labor, do not merely consume destinations; they narrate and reframe them continuously through blogs, vlogs, and social media. Their role in generating what could be termed ambient eWOM—a form of passive, consistent, and non-strategic place promotion—extends beyond the episodic travel review. Instead, it builds a long-tail influence through a slow accretion of everyday content. This is in contrast to traditional influencer campaigns, which tend to be short-term, curated, and anchored in promotional intent [

13,

33].

Digital nomads rarely produce content with the explicit goal of marketing a destination. Rather, they document their lives—coworking, cooking, commuting—and in doing so, render the place legible and desirable to others. These slow media narratives, as conceptualized by Munar and Jacobsen, operate through repetition, familiarity, and the affective proximity they create over time [

13]. Their authenticity stems not from being unmediated, but from being embedded and uncontrived—what Abidin) calls “calibrated amateurism” [

33]. Such content is algorithmically discoverable but appears non-commercial, thereby enhancing its persuasive power.

Unlike tourists, whose presence is transient and content ephemeral, digital nomads inhabit destinations for extended periods. This temporal depth enables them to generate cumulative influence. Their observations are not framed as spectacle but as lived realities: the cost of groceries, the stability of internet connections, the walkability of neighborhoods, or the cultural vibe of a city. These seemingly mundane attributes are precisely what matters to like-minded audiences—remote workers, lifestyle migrants, and long-stay travelers—who make decisions based on practical, emotionally resonant factors [

12,

39].

Importantly, digital nomads operate within dense, horizontal networks—what Wenger terms communities of practice—where knowledge circulates informally but authoritatively [

40]. Facebook groups, Telegram channels, Reddit threads, and comment sections form information ecosystems where first-person narratives are validated, contested, and reshared. In these spaces, nomads are not positioned as promotional authorities but as proximate peers—people “like me” whose insights are perceived as more credible precisely because they lack formal endorsement [

41,

42]. This relational credibility—rooted in shared values, lifestyles, and aspirations—underpins the trust that makes eWOM so effective in shaping destination appeal.

The theoretical significance of these dynamics is underscored by Granovetter’s notion of “the strength of weak ties” [

43]. Digital nomads often function as aspirational weak-tie figures—distant yet familiar, accessible yet inspiring. Their stories open up imagined pathways for others who wish to emulate the nomadic lifestyle. This aspirational function is particularly impactful in the case of lesser-known or emerging destinations, where formal marketing is absent or limited. Here, the first digital nomads to arrive play a role akin to early adopters in diffusion theory [

44], not only discovering but also semiotically constructing the destination for others.

Yet, this symbolic influence is not evenly distributed. As several scholars have noted, the global discourse around digital nomadism is shaped disproportionately by Western, white, English-speaking content creators [

15,

16,

17]. Their esthetic preferences, cultural values, and infrastructural priorities tend to dominate, often reinforcing neoliberal imaginaries of self-optimization, borderless freedom, and lifestyle entrepreneurship. In doing so, they may inadvertently marginalize local narratives, alternative imaginaries, or more rooted forms of place engagement. This asymmetry in content production and visibility raises critical ethical and epistemological questions about voice, representation, and digital privilege in the tourism media landscape.

Furthermore, the narratives constructed by digital nomads are often shaped by their class position, passport power, and linguistic capital. Their ability to live in Sarajevo, Bali or Medellín while working remotely is contingent on transnational mobility regimes that are not universally accessible. As Sheller and Thompson argue [

1,

10], the freedom to move and narrate space is deeply stratified, embedded in broader structures of global inequality. In this light, the seemingly organic eWOM generated by nomads is not just a neutral form of storytelling, but a culturally and politically situated act—one that requires greater reflexivity from tourism scholars and practitioners alike.

Despite these concerns, the power of ambient, peer-level content remains undeniable. From a marketing perspective, it challenges traditional models of brand control and intentional influence. Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs), which typically focus on orchestrated campaigns and contractual influencer partnerships, may overlook the more diffuse but durable forms of promotion generated by digital nomads. As

Figure 1 in this study illustrates, digital nomads are not merely passive travelers but active co-creators of destination image—albeit without formal roles or recognition. Their embedded storytelling activates precisely the mechanisms—authenticity, credibility, emotional resonance—that tourism research has long identified as central to effective communication [

19,

20].

In sum, digital nomads exemplify a contemporary mode of influence that is ambient, relational, and unintentional. Their content contributes to destination branding not through spectacle, but through situated normalcy. They shape perceptions of place not by marketing, but by narrating their lives. And they persuade not through authority, but through affinity. These dynamics complicate the traditional binaries of influencer vs. user, marketer vs. consumer, and content vs. commerce—suggesting that the future of tourism branding lies not in campaigns, but in conversations.

As such, this section reinforces both Research Question 1 and Research Question 2. It demonstrates how digital nomads influence destination perceptions through continuous, authentic storytelling, and how their peer-generated content is often perceived as more credible than commercial influencer marketing. Their symbolic power emerges not from sponsorship or strategic messaging, but from prolonged engagement, habitual documentation, and a media ecology that increasingly values sincerity over spectacle.

2.5. Destination Marketing Organizations: Blind Spots and Missed Opportunities

Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs) have historically held a central role in constructing and disseminating place-based narratives. Their primary function has been to attract visitors by shaping how destinations are seen, remembered, and desired. For decades, this has involved top-down strategies: developing core brand identities, commissioning high-profile marketing campaigns, and controlling key media channels directed at segmented markets [

45,

46]. These strategies aligned with a broadcast-era logic in which destination image could be managed through centralized messaging and top-down promotional authority.

In recent years, many DMOs have updated their practices to include influencer partnerships and user-generated content (UGC). However, these adaptations often remain surface level, retaining a preference for content that can be framed, contracted, and measured [

6]. This legacy model, while once effective, is increasingly ill-suited to a media landscape defined by decentralization, peer networks, and platform-driven content flows [

25]. As Sigala contends, digital tourism now operates in a media ecology shaped by participatory logics [

26]. Tourists no longer consume place passively but co-create it through their content, social interactions, and embedded digital practices. Despite this, DMOs often maintain legacy models rooted in control—over message tone, platform visibility, and performance metrics—leaving them poorly positioned to engage meaningfully with decentralized or ambient forms of influence. This emphasis on trackability has created a

strategic blind spot: the informal, sustained, and often more credible influence generated by digital nomads is rarely acknowledged, let alone strategically engaged.

Digital nomads fall outside the typical categories of stakeholder engagement in tourism management. They are not residents, not tourists, and not official partners. Their influence is ambient—emerging through serialized lifestyle documentation rather than structured endorsement—and their outputs are typically untracked by formal systems of marketing analytics. This creates what can be described as a misrecognition gap: DMOs often benefit from the branding effects of nomad-generated content while failing to formally acknowledge its value or integrate it into strategy [

8,

9].

A growing number of destinations—Madeira, Bali, Lisbon, and Tbilisi, among others—have launched programs to attract digital nomads through special visas, coworking infrastructure, or promotional campaigns [

2]. These initiatives recognize the economic potential of long-stay remote workers, particularly in post-pandemic recovery contexts. However, policy framing often limits digital nomads to an economic or logistical category. They are treated as consumers of space, not contributors to place identity. Their symbolic labor—the daily production of blogs, social media content, and peer recommendations—is rarely incorporated into destination brand management.

The hesitation to engage with digital nomads is partially rooted in concerns over brand control and representational risk. Because nomads are not paid or managed, their content cannot be scripted. They may highlight infrastructure gaps, social tensions, or cultural misunderstandings that clash with curated destination identities. Yet, as Mariani, Di Felice, and Mura note, perceived authenticity—

even when it reveals flaws—can increase credibility and traveler trust [

31]. Thus, ignoring nomads not only overlooks a valuable promotional asset, but also reinforces a fragile branding logic overly dependent on perfection and message discipline.

Another barrier is methodological: DMOs tend to rely on short-term, campaign-based metrics such as impressions, click-through rates, and return on investment (ROI). These indicators are poorly equipped to capture the diffuse, slow-burn effects of ambient influence or peer-driven content [

47,

48]. As a result, informal content creators like digital nomads fall through the cracks of evaluation logic. Their influence exists, but it cannot be easily quantified or optimized within existing frameworks.

A further complication is epistemological. Institutional knowledge systems are shaped by long-standing assumptions about what constitutes influence, legitimacy, and value. Within many DMOs, influence is still seen as something that is bought, managed, and measured. This paradigm is at odds with the realities of digital travel culture, where trust, relatability, and embeddedness increasingly determine how destinations are imagined and pursued [

13,

38]. Recognizing digital nomads as symbolic producers would require not just new tools but new ways of knowing and valuing media activity.

The strategic blind spot—visualized in

Figure 1—is thus both practical and conceptual. It reflects an institutional lag between the evolution of tourism media and the governance structures tasked with managing it. Addressing this gap involves more than just outreach. It requires a fundamental rethinking of how DMOs engage with informal influence. Several authors have called for such shifts, emphasizing the importance of participatory branding [

28], grassroots place-making [

49], and non-commercial tourism imaginaries [

50]. Digital nomads fit squarely within these frameworks yet remain overlooked. Understanding this blind spot is essential to addressing Research Question 3, which asks whether, and how, DMOs are beginning to recognize the place-branding impact of digital nomads, and what kinds of engagement, if any, are emerging in response.

Future-facing DMOs may benefit from developing light-touch recognition mechanisms for nomadic content creators: informal ambassador networks, opt-in registries, or resource hubs designed to support narrative diversity without sacrificing institutional distance. Rather than controlling narratives, these tools would enable DMOs to curate alongside their communities, engaging in co-production without eroding the organic credibility of peer storytelling.

In sum, the current DMO model privileges visibility, sponsorship, and control. Digital nomads offer a counterpoint: decentralized, unpaid, and often more influential than formal campaigns. Failing to recognize this is not merely a missed opportunity—it is a structural limitation that may leave DMOs increasingly out of sync with how travel inspiration is produced and circulated in a digitally networked world.

3. Methodology

This study adopts a multi-method, multi-study research design to investigate how digital nomads function as unintentional brand ambassadors. The methodological strategy integrates both quantitative and qualitative components to capture the scope, depth and institutional implications of digital nomads’ influence on destination branding. The approach is guided by three research questions, each targeting a distinct aspect of the phenomenon: audience impact (RQ1), comparative influence (RQ2), and institutional response (RQ3). These questions correspond to Studies 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and are visualized in the conceptual model presented in

Figure 1.

3.1. Research Design Overview

The approach is guided by three research questions—audience impact (RQ1), comparative influence (RQ2), and institutional response (RQ3)—which correspond to Studies 1, 2 and 3, respectively:

Study 1: A quantitative survey that measures how exposure to digital nomad content influences destination image, perceived authenticity and travel intentions.

Study 2: A controlled experimental comparison of digital nomad versus influencer-generated travel content, focusing on differences in trust, authenticity and persuasiveness.

Study 3: A qualitative inquiry using semi-structured depth interviews with senior DMO professionals to assess institutional awareness, engagement strategies and perceived barriers in working with digital nomads.

This structure allows triangulation across data types, ensuring both generalizability and depth of insight [

51]. For Studies 1 and 2, we further derive four directional propositions (P1–P4) from the conceptual model, which are tested as structural hypotheses in the quantitative analyses.

3.2. Study 1: Survey of International Travelers

3.2.1. Objectives and Theoretical Justification

Study 1 aims to empirically investigate RQ1:

To what extent do digital nomads influence others’ perceptions of destinations through their online presence? This inquiry builds on destination image theory [

19,

20] and draws from the literature on user-generated content [

52,

53], which emphasizes the credibility and impact of non-institutional sources on travel-related attitudes and intentions.

A cross-sectional online survey methodology was selected due to its appropriateness for capturing perceptual data from a diverse, geographically dispersed population [

54]. Surveys remain a foundational tool for examining psychological constructs like image perception, trust, and behavioral intention in tourism research, and offer the benefit of statistical generalizability when combined with appropriate sampling and measurement rigor [

55].

3.2.2. Instrument Development, Measures and Scale Design

Respondents evaluated their exposure to digital nomad content, perceived authenticity, destination image, and travel intention. Each construct, with the exception of the “Exposure to nomad content”, was measured using multi-item 7-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Exposure items were measured on a 1–5 scale; in the primary analyses, we modeled Exposure as its own latent variable on its native 1–5 metric (no rescaling), together with the other 1–7 latent constructs. As a robustness check, we standardized all items (z-scores) prior to CFA/SEM; the pattern, size, and significance of all structural paths were unchanged. Measures included:

Exposure to nomad content—Captured recency, frequency, and channel (e.g., YouTube, Instagram, blogs), with 3 items (α = 0.82). The “Exposure to digital nomad content” measure was developed specifically for this study, drawing conceptually on prior studies that assess social media and user-generated content exposure (e.g., Ayeh et al. and Xiang & Gretzel) [

38,

52]. It included three items assessing frequency, recency and primary platform, pre-tested for clarity and reliability.

Destination image—Combined cognitive (infrastructure, safety) and affective (excitement, friendliness) perceptions, based on Baloglu and McCleary [

56], and Tasci and Gartner [

20], with 5 items (α = 0.86).

Perceived authenticity—Measured using items adapted from Lou and Yuan [

33] and Kolar and Zabkar [

57], with 4 items (α = 0.88).

Behavioral intention—Likelihood of visiting the destination as inspired by the content, adapted from Ajzen [

58], with 3 items (α = 0.85).

Recent TPB-based tourism research using similar 7-point Likert scales and SEM supports these image/attitude/behavior links [

59]. Items were pre-tested with 28 participants to refine clarity and ensure face validity. Cronbach’s alpha values from the pilot indicated acceptable internal consistency for all constructs (α > 0.78). Exploratory factor analysis confirmed unidimensionality and confirmatory factor analysis was used to test model fit and validity. The measures were designed to align with constructs in the conceptual model (

Figure 1). Study 1 tests P1–P3 via SEM (with bootstrapped indirect effects for P3).

3.2.3. Bias Diagnostics/Common Method Bias

We included a short social-desirability marker (3 items) collected concurrently with Study 1. Following the marker-variable technique, we partialed the marker from all substantive constructs and re-estimated the SEM. Key paths changed by <0.02 and remained significant; model fit was unchanged (ΔCFI ≤ 0.001; ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.002). We also entered social desirability as a covariate at the construct level; its effects were small (|β| ≤ 0.08) and non-substantive. Full deltas are reported in

Table 2.

We estimated an alternative model with a latent methods factor loading on all indicators (loadings constrained equal; methods factor uncorrelated with substantive factors). The estimated method variance was negligible (mean method loading ≤ 0.12), and substantive paths were unchanged (|Δβ|< 0.02; signs/significance identical). Fit did not improve meaningfully (ΔCFI = 0.002). Full results appear in

Table 3.

3.2.4. Sampling Strategy and Participant Characteristics

A non-probability purposive sampling strategy was used, targeting internationally mobile individuals aged 18–45 who consume travel-related digital content. Participants were recruited via Prolific Academic, Reddit travel subforums, and Instagram call-outs. Eligibility screening ensured respondents had viewed digital nomad content and for having traveled internationally in the past 12 months.

A total of 487 valid responses were collected from 34 countries, with proportional representation from Europe (38%), North America (29%), Southeast Asia (17%), and other regions (16%). The sample was balanced by gender (52% female) and skewed toward Millennials and Gen Z (M = 29.7 years, SD = 6.3), reflecting the digital-native demographic most likely to be influenced by nomadic content.

3.2.5. Data Analysis Procedures

Data analysis was conducted in SPSS 30 and AMOS 26. Following initial data screening, descriptive statistics and reliability analysis (Cronbach’s alpha) were performed. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to validate construct structure, followed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess model fit. Path analysis via structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine relationships between content exposure, destination image, authenticity, and travel intention.

Model fit indices followed Hu and Bentler’s criteria (e.g., RMSEA < 0.08, CFI > 0.90) [

60]. Normality was assessed via skewness, kurtosis, and Mardia’s coefficient. Mediation effects were tested using bootstrapping (5000 resamples) to determine whether perceived authenticity mediated the link between exposure and behavioral intention. Effect sizes (Cohen’s f

2) were reported for all significant paths.

3.2.6. Methodological Limitations

While online surveys are effective for capturing large-scale attitudinal data, limitations include potential self-selection bias and reliance on self-reported exposure and intent. To mitigate these issues, eligibility screening was enforced and exploratory analyses controlled for social desirability bias using the Marlowe-Crowne scale short form.

3.3. Study 2: Experimental Comparison of Content Types

3.3.1. Objectives and Theoretical Justification

Study 2 addresses RQ2:

How does the influence of digital nomads compare with traditional influencer marketing in terms of perceived trust, authenticity, and audience impact? This research question emerges from the literature’s growing concern with declining trust in highly commercialized content [

32,

34], and the need to distinguish between intentional (sponsored) and unintentional (lifestyle-based) forms of place promotion. Drawing from persuasion theory [

61], and the source credibility model [

62], this study experimentally tests whether content created by digital nomads is perceived as more authentic, trustworthy, and persuasive than content produced by traditional travel influencers.

An online between-subjects experimental design was selected to establish causal relationships while maintaining ecological validity through the use of realistic stimuli [

63]. Experimental methodology is appropriate when isolating the effect of message source (i.e., nomad vs. influencer) on psychological outcomes such as trust, authenticity perception, and behavioral intention [

33]. Study 2 provides a causal test of P4 by manipulating persuasion salience—participants viewed either an ambient (unsponsored) nomad video or a sponsored influencer video with salient commercial intent.

3.3.2. Stimuli and Experimental Conditions

Two video stimuli 3–4 min each (Nomad: 231 s; Influencer: 224 s; production quality and topic were matched) were curated for this study:

Condition A (Digital Nomad Content): A casual, non-sponsored video blog (vlog) created by a digital nomad showing a “day in the life” in a mid-tier destination (e.g., Chiang Mai). Content focused on everyday activities, local interactions, work setups, and housing.

Condition B (Influencer Content): A professionally edited, clearly sponsored travel video by a well-known influencer promoting the same destination, with cinematic visuals, branded hashtags, and tourism board messaging.

Both videos were pre-tested (see

Section 3.3.3) to ensure comparability in length, location, and production quality. Differences in tone and presentation were sufficient to distinguish between organic and commercial content.

Both stimuli were sourced from publicly available YouTube vlogs identified through a structured search using destination names and digital-nomad–related keywords. The creators of these videos had no involvement in the design or analysis of the study and were not informed that their content was being used as research material. To maximize transparency and reproducibility while respecting third-party copyright, we archived verbatim transcripts of the segments used, high-resolution still frames, and full metadata for each video (titles, channel names, public URLs, upload dates, durations and view counts at the time of data collection) in the open Zenodo repository referenced in the Data & Materials Availability section (

Section 3.6). Researchers wishing to replicate or extend the experiment can reconstruct the stimuli by following the step-by-step procedure documented in the repository README, or, if necessary, can request time-limited view-only access to the original files from the corresponding author.

3.3.3. Stimulus Pre-Test and Equivalence

Prior to the main study, we pre-tested the two videos (

n = 60; inclusion: prior exposure to the platform ≥ monthly; fluent English; passed an attention check). We verified equivalence on length and production quality and checked baseline familiarity with the destination; participants who reported prior viewing of either video or failed the attention check were excluded (

n = 4), leaving

n = 56 (28 per condition) for analysis. As intended, perceived promotional intent differed strongly across versions, while length, production quality, and baseline familiarity showed no meaningful differences (

Table 4).

3.3.4. Measures and Instrumentation

Following stimulus exposure, participants completed a structured questionnaire measuring:

Perceived authenticity—Adapted from Lou and Yuan [

33], including 3 items such as “This content feels real and unfiltered.”

Perceived trustworthiness of the source—Based on Ohanian’s 3 items scale [

64].

Perceived promotional intent—Items measuring how commercial or strategic the content felt (3 items), adapted from Evans et al. [

65].

Destination appeal and travel intention—Likelihood of visiting the destination based on the content, adapted from Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior (3 items) [

58].

All items used 7-point Likert scales (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree) and demonstrated acceptable reliability (α ≥ 0.80).

3.3.5. Sampling and Procedure

Participants (n = 210) were recruited via Prolific and social media channels. Inclusion criteria required participants to be active social media users aged 18–40, who follow or consume travel-related content online. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions and provided informed consent prior to viewing.

Demographics were balanced across conditions (Condition A: n = 106; Condition B: n = 104), and groups were statistically equivalent in terms of age, gender, travel frequency, and prior familiarity with the destination (p > 0.10 for all comparisons).

3.3.6. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 30 and JASP 0.95.3. Independent-samples t-tests were used to compare mean scores across groups for each dependent variable (authenticity, trust, intent, perceived persuasion). Effect sizes (Cohen’s d, partial η2) were reported for all statistically significant differences. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and reliability checks (Cronbach’s α > 0.80) confirmed the internal consistency of scales.

A post hoc MANOVA was conducted to assess interaction effects of demographic moderators (e.g., age, social media use frequency) on message impact.

3.3.7. Methodological Limitations

Although video stimuli were selected to mimic real-world content, exposure was limited to a single instance, whereas influence in naturalistic settings is often cumulative. Future studies could explore long-term exposure patterns or include behavioral tracking. Nonetheless, the experimental design allows for causal inference on the role of message source in shaping key outcomes related to digital branding.

3.4. Study 3: Destination Marketing Organizations—Depth Interviews with Experts

3.4.1. Objectives and Theoretical Justification

Study 3 explores RQ3:

What strategies, if any, are Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs) employing to recognize or leverage the influence of digital nomads? This component addresses a critical institutional gap identified in the literature: while digital nomads generate valuable user-generated content (UGC) that shapes destination perception, their influence often falls outside the strategic purview of traditional tourism governance models [

26,

45].

A qualitative, semi-structured personal depth-interview approach was employed to access the lived perspectives of marketing professionals within DMOs and uncover how they interpret and respond to the evolving landscape of peer-to-peer influence. This method is particularly suited to examining under-theorized or emergent organizational practices [

66], allowing for both inductive and theoretically informed insights.

3.4.2. Paradigm & Reflexivity

We adopted a post-positivist stance. The lead researcher was an outsider to DMOs and maintained a reflexive journal throughout data collection/analysis. Member checking was offered to a subset of interviewees (

n = 4) and peer debriefs were conducted after every 3–4 interviews. Saturation was reached at approximately interview 12, with two further interviews confirming stability. (See Reflexivity Note in

Supplementary Materials for additional detail, at:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17199056)

3.4.3. Sampling and Participant Profile

Using purposive and snowball sampling, 14 senior DMO professionals were recruited from across Europe, Asia-Pacific, and Latin America. Participants included directors of marketing, digital strategy leads, and public-private tourism partnership managers. Recruitment emphasized variation in destination type (urban/rural, emerging/established) and digital maturity (e.g., social media presence, influencer program history).

Participants represented national, regional, and city-level DMOs, ensuring a diversity of perspectives on institutional strategy, capacity, and branding priorities.

3.4.4. Interview Protocol and Procedure

A semi-structured depth interview guide was designed around four thematic areas:

Awareness—To what extent are digital nomads recognized as a distinct traveler segment?

Perception—How do DMO professionals evaluate the impact of nomad-generated content?

Strategy—Are there existing or planned efforts to engage with this group?

Barriers—What institutional, financial, or political factors prevent formal recognition or inclusion?

Interviews were conducted via Zoom and Microsoft Teams, each lasting between 45 and 70 min. All interviews were audio-recorded with consent and professionally transcribed. Identifying information was anonymized. Analysis followed reflexive thematic analysis with double-coding on ~25% of transcripts; discrepancies were discussed to convergence. Quotations were selected for representativeness and divergence and are labeled by role/level to preserve anonymity.

3.4.5. Thematic Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed thematically using NVivo 14. Coding followed Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework for reflexive thematic analysis [

67]:

Familiarization with transcripts.

Initial coding of segments related to nomad visibility, value, and voice.

Collapsing codes into broader themes (e.g., “invisible influence,” “operational uncertainty,” “risks of informality”).

Reviewing themes against full dataset.

Defining and naming themes.

Producing the narrative synthesis.

Both inductive and deductive approaches were used to surface key patterns. To ensure trustworthiness, coding was peer-reviewed by a second researcher, and thematic saturation was reached by the 12th interview. Themes were iteratively refined in relation to the conceptual model (

Figure 1), particularly the “DMO strategic blind spot” construct.

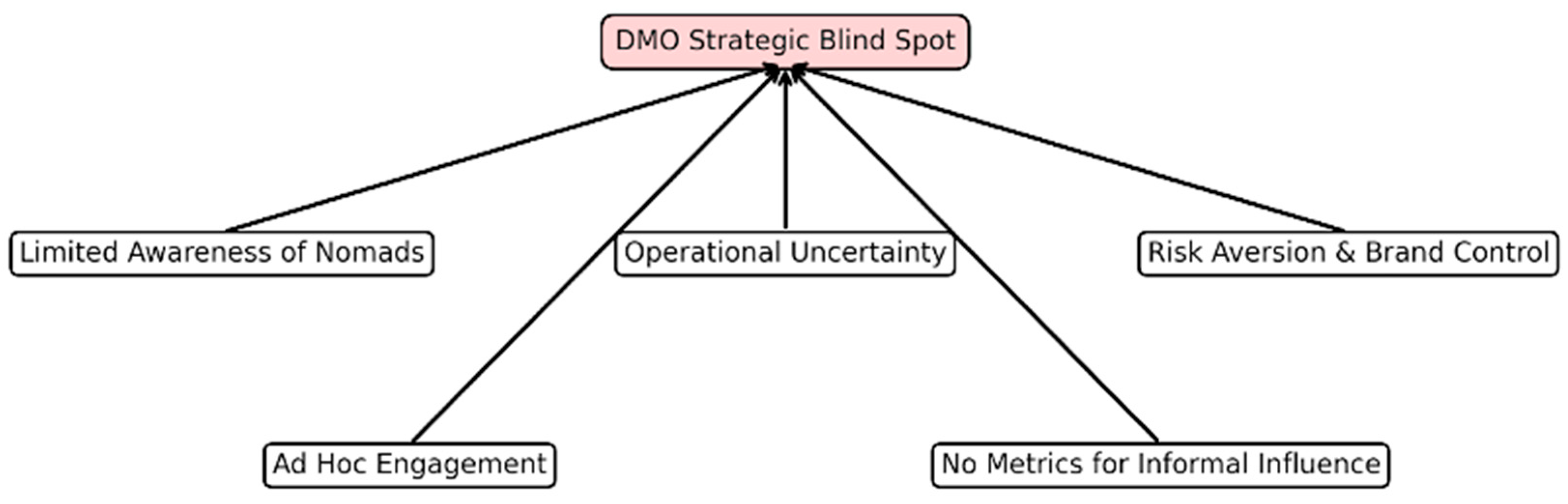

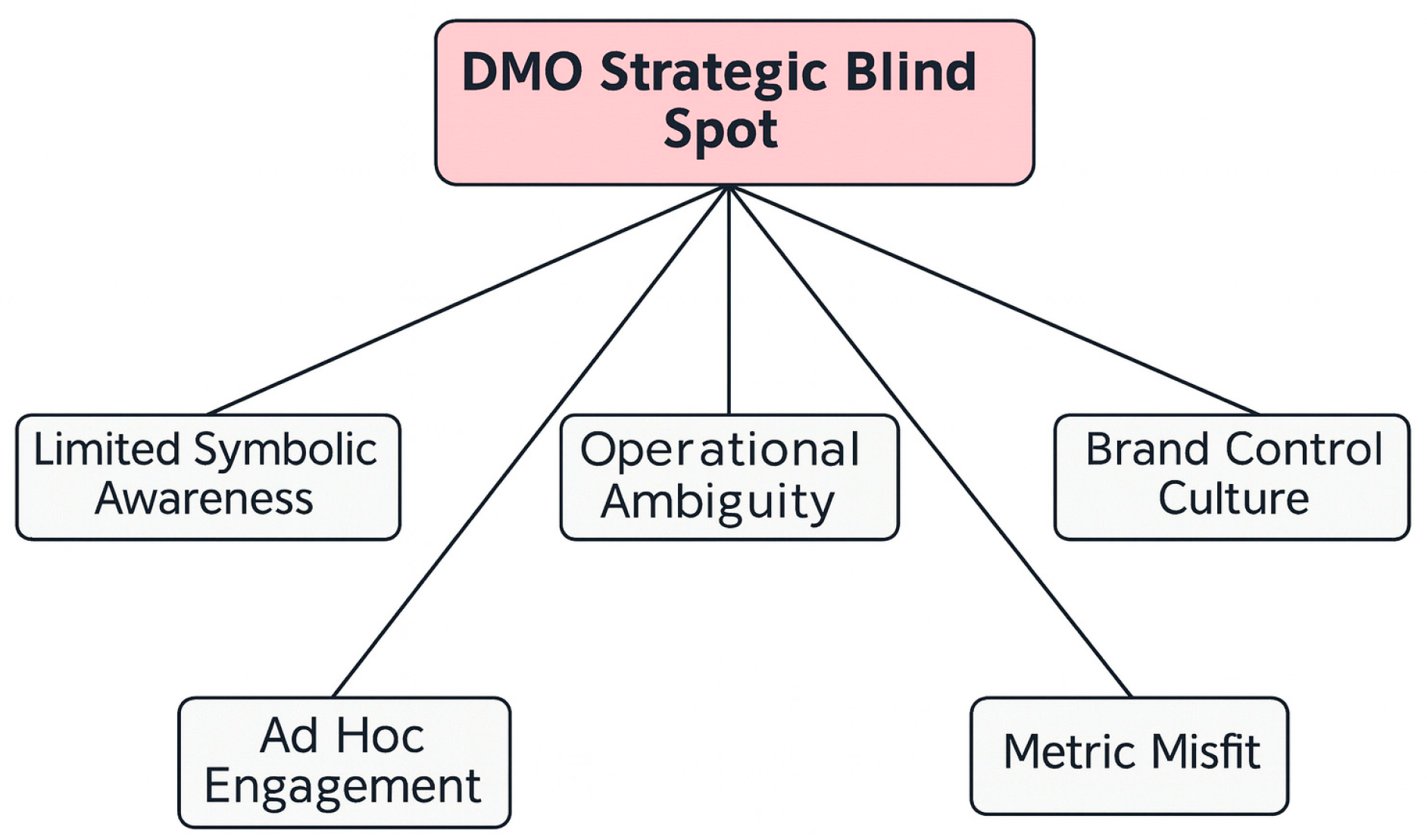

Thematic analysis revealed a consistent pattern across interviews: while some DMOs acknowledged the visibility and potential influence of digital nomads, institutional responses remained fragmented and reactive. The five emergent themes collectively underscore the structural and perceptual barriers that prevent DMOs from engaging meaningfully with this informal yet impactful group. These findings are visually summarized in

Figure 3, which maps the core “strategic blind spot” and its contributing dimensions, reinforcing the conceptual model presented in

Figure 1.

This figure summarizes the five central themes that emerged from qualitative interviews with Destination Marketing Organization (DMO) professionals. At the core is the “DMO strategic blind spot,” a conceptual gap identified in Figure 1. The sub-themes reflect specific institutional limitations: limited awareness of digital nomads as content creators, operational uncertainty in responding to emergent forms of influence, risk aversion tied to brand control, ad hoc or reactive engagement strategies, and a lack of metrics to capture the value of informal, ambient promotion. Together, these themes highlight systemic barriers to integrating digital nomads into destination branding strategies. Source: Authors’ own analysis of qualitative interview data (Study 3).

3.4.6. Validity and Reflexivity

Triangulation was ensured by comparing data across DMO types, locations, and respondent roles. Member-checking was conducted with four participants to validate thematic interpretations. Reflexivity was maintained through a research log documenting positionality, assumptions, and interpretive decisions throughout analysis [

68].

3.4.7. Methodological Limitations

Findings from this study reflect the perspectives of DMO professionals and may not represent broader government or industry views. The reliance on English-speaking participants may also introduce geographic and linguistic bias. However, the purposive sampling and thematic saturation achieved across interviews support the validity of emergent insights regarding institutional awareness and strategy.

3.5. Ethical Considerations and Participant Consent

All participants provided informed consent and were debriefed. Anonymity and data security were ensured across all phases of the research. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Organisation Management, Marketing and Tourism of the International Hellenic University (protocol code 138 and date of approval 17 October 2024) for studies involving humans.

Participation in all three empirical components was voluntary and based on explicit informed consent. For Study 1 (survey) and Study 2 (experiment), respondents first viewed an online information sheet describing the purpose of the research, the nature and expected duration of their participation, the voluntary character of participation, potential risks and benefits, data protection procedures, and contact details of the research team. Only individuals who actively indicated consent (by clicking an “I agree to participate” button) could proceed to the questionnaire. Participants were informed that they could discontinue the survey or close the browser window at any point before submission without penalty and that no incentives would be affected by withdrawal. No directly identifying information (e.g., names, email addresses) was collected with the survey or experimental responses, and demographic questions were restricted to broad categories (e.g., age range, self-described gender, region). IP addresses were not stored. At the end of the questionnaire, participants received a short debriefing explaining the aims of the project and how their anonymized data would be used.

For Study 2, the consent page additionally explained that the original creators of the video clips used as stimuli were not research participants, and that participants’ responses would be analyzed only in aggregated form without any link back to their personal profiles or viewing history. Participants were informed that no sensitive content was included in the videos.

For Study 3 (DMO interviews), potential participants received an email information sheet and consent form prior to scheduling an interview. Written consent was obtained for participation, audio recording, and the use of anonymized quotations in publications. Interviewees were reminded that participation was voluntary, that they could decline to answer any question, and that they could request withdrawal of their data up to the point of anonymization and analysis. Organizational and personal identifiers were removed or generalized (e.g., by using regional labels and role descriptions) during transcription and coding, and only anonymized excerpts are reported in the findings.

Across all three studies, data were stored on password-protected drives accessible only to the research team, and all datasets used for analysis and public archiving were de-identified in line with GDPR and institutional requirements (see

Section 3.6).

3.6. Data & Materials Availability

Study 1 (Survey): cleaned, de-identified dataset; codebook; SEM/CFA scripts and output; item wordings and scale anchors.

Study 2 (Experiment): cleaned, de-identified dataset; pre-registered; analysis scripts for manipulation checks, ANCOVA, and mediation; instrument and manipulation-check items.

Study 3 (Interviews): anonymized excerpted quotations used in the paper; theme/codebook; audit trail summary (sampling, saturation notes).

Supplementary Materials: figure/table source files; robustness checks (controls, multigroup, invariance); README with step-by-step replication instructions and software versions.

Restrictions: In line with copyright restrictions, we do not redistribute local copies of the full video stimuli. Instead, we provide verbatim transcripts, frame stills, and detailed metadata (including public URLs, durations and posting dates), together with step-by-step procedures to reconstruct the stimuli set from the original YouTube pages. This gives readers open access to all information needed to reproduce the experimental manipulation while respecting third-party rights. Researchers may additionally request time-limited, view-only access to the original video files for verification purposes under a non-distribution agreement (subject to institutional approval).

Anonymization & compliance: All datasets are de-identified and stored per GDPR and institutional ethics approval (IRB protocol code 138, date of approval 17 October 2024). Any indirect identifiers were removed or binned.

Licensing & citation: Data and materials are released under CC BY 4.0. Please cite the repository DOI when reusing these materials.

Reproducibility: A replication script (R/Python) reproduces the tables/figures reported here from the raw de-identified data; session info and package versions are provided.

3.7. Integration and Rigor

The three studies were integrated to triangulate findings and offer a layered understanding of unintentional influence. Quantitative results validated behavioral and perceptual effects, while qualitative insights contextualized institutional responses and policy gaps. Together, this design supports both empirical robustness and practical relevance, aligned with the journal’s focus on actionable tourism research.

5. Discussion

This study explored the emergent but under-theorized role of digital nomads as unintentional brand ambassadors—individuals whose organic, unsponsored, and serialized content plays a significant role in shaping destination image and influencing travel behavior [

74]. Drawing on a multi-method, multi-study design—including quantitative modeling (Study 1), controlled experiment comparison (Study 2), and expert depth interviews (Study 3)—the research offers new conceptual tools and empirical insights into how influence is enacted, perceived, and managed in digitally mediated tourism environments.

In doing so, the study challenges core assumptions in both tourism branding and destination governance: that influence must be intentional to be effective, that control ensures credibility, and that only traceable promotional activity has strategic value [

73].

5.1. Toward a Theory of Ambient Influence

The main theoretical contribution of this study is the articulation of ambient influence—a form of symbolic power that emerges not from deliberate promotion, but from the cumulative effects of unsponsored, everyday digital content. Ambient influence is characterized by its persistence, subtlety, and relational nature, distinguishing it from both formal marketing and traditional user-generated content (UGC). Unlike campaigns designed with conversion metrics in mind, ambient influence operates through presence rather than persuasion, repetition rather than reach, and familiarity rather than novelty. It is an influence of osmosis, accruing meaning through slow exposure rather than strategic delivery.

This approach critiques foundational paradigms in tourism branding, which prioritize intentionality, central messaging, and campaign-based planning [

6,

25,

46]. Ambient influence reframes the unit of analysis from institutional strategy to informal social practice, aligning more closely with emergent models of media circulation in digital culture [

75,

76]. By focusing on the symbolic labor of lifestyle-based content producers—particularly digital nomads—this framework highlights a layer of influence that remains under-theorized in destination marketing.

Empirically, Study 1 grounds this concept by demonstrating that exposure to digital nomad content significantly shapes both destination image and travel intention. This occurs even in the absence of promotional framing, suggesting that perceived authenticity—not production quality or esthetic polish—is the critical mediator. This aligns with growing skepticism toward overtly commercial content [

38] and supports findings that peer-level content is more trusted than official messaging [

33,

37]. In this respect, ambient influence draws from the logic of narrative embeddedness—where storylines accumulate credibility through consistency and proximity [

13].

Study 2 strengthens this distinction by comparing traditional influencers with digital nomads across multiple dimensions. Nomad content consistently outperforms influencer content in perceived authenticity, trustworthiness, and behavioral intent. This is not because nomads are inherently more persuasive, but because their content aligns with platform-native expectations of sincerity and relatability [

34,

77]. The finding challenges the assumption that institutional visibility equates to effectiveness—DMOs may be investing in high-visibility actors who lack audience credibility, while overlooking informal creators whose influence is diffuse but substantial.

This produces a key theoretical tension: institutional visibility versus audience believability. Sponsored influencers are embedded within formal brand ecosystems—tracked, approved, and scripted—but are often perceived by audiences as overly polished or commercially motivated [

48]. Digital nomads, in contrast, are not institutionally visible, but resonate more strongly with users precisely because they appear unscripted. Their influence is structurally ambient, not by design, but by default—born of repetition, routine, and low-stakes storytelling. In this way, their media practices enact what Couldry and Hepp term deep mediatization: the embedding of media logic into the everyday [

75], shaping how destinations are felt and imagined.

This ambient dynamic is analogous to the role of micro-celebrities or contextual influencers in other sectors, who engage niche audiences through sustained presence rather than wide-scale broadcasting [

13,