When AI Chatbots Ask for Donations: The Construal Level Contingency of AI Persuasion Effectiveness in Charity Human–Chatbot Interaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

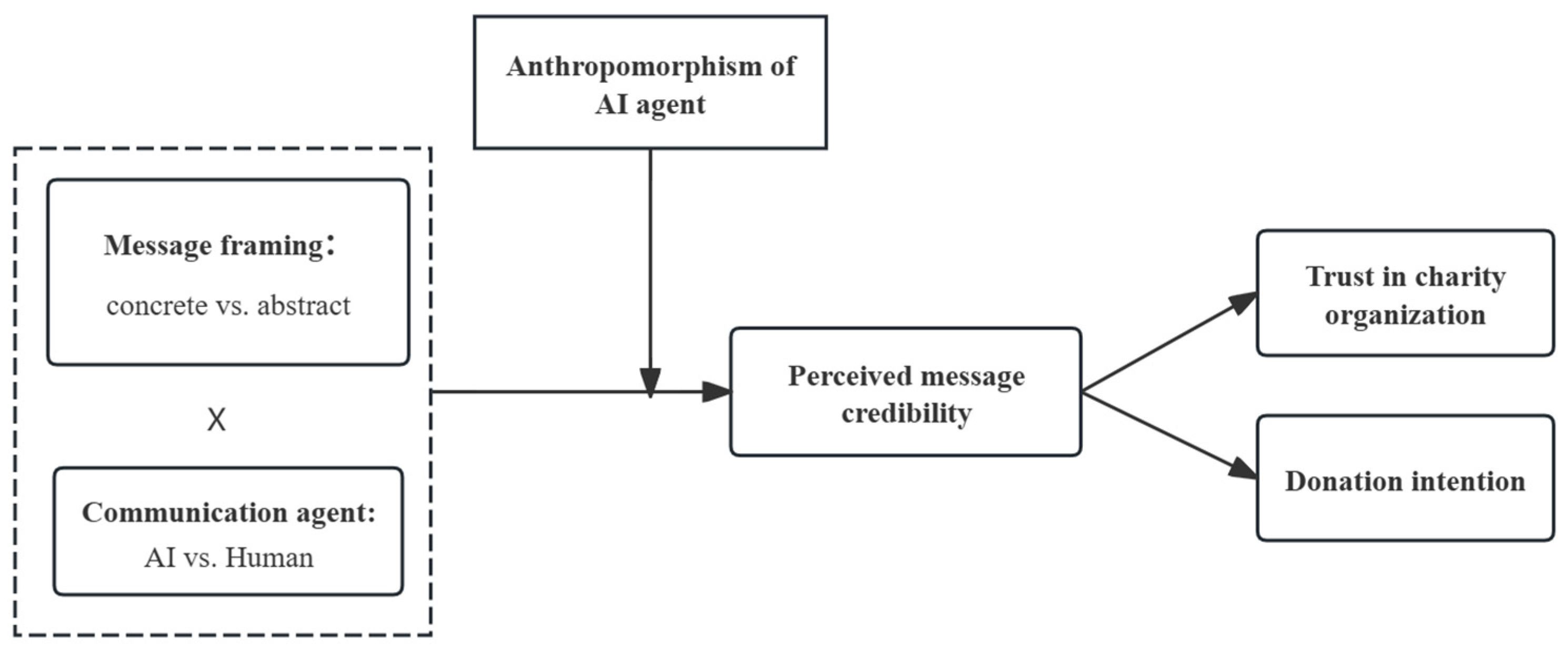

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. The Human-AI Chatbot Interaction and Marketing Persuasion

2.2. Charitable Donation of Consumers

2.3. Consumer Trust in the Age of AI

2.4. Message Framing and AI Persuasion in Online Fundraising

2.5. Perceived Message Credibility, Consumer Trust and Donation Intention

2.6. The Moderation Effect of Anthropomorphism

3. Study 1

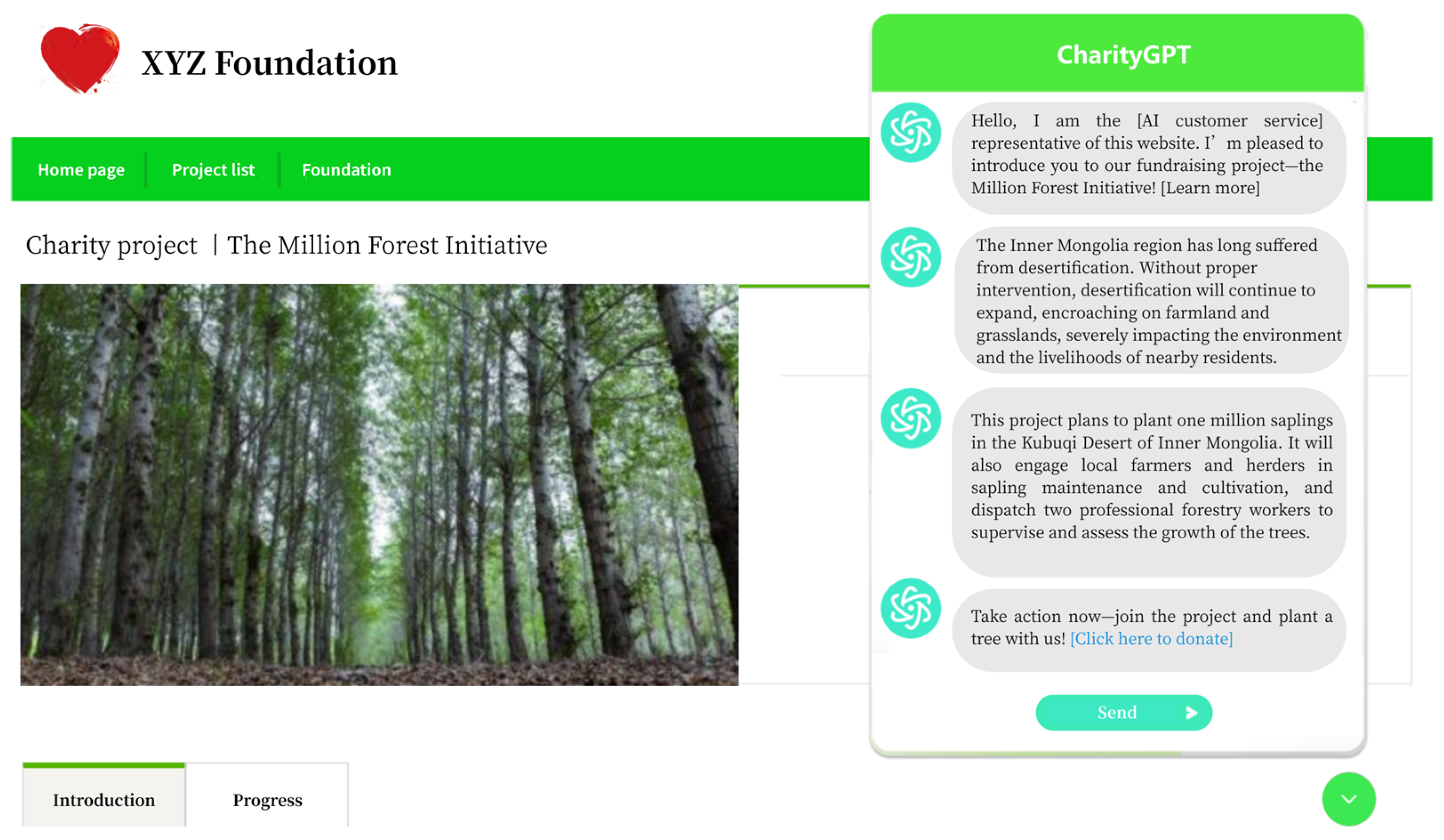

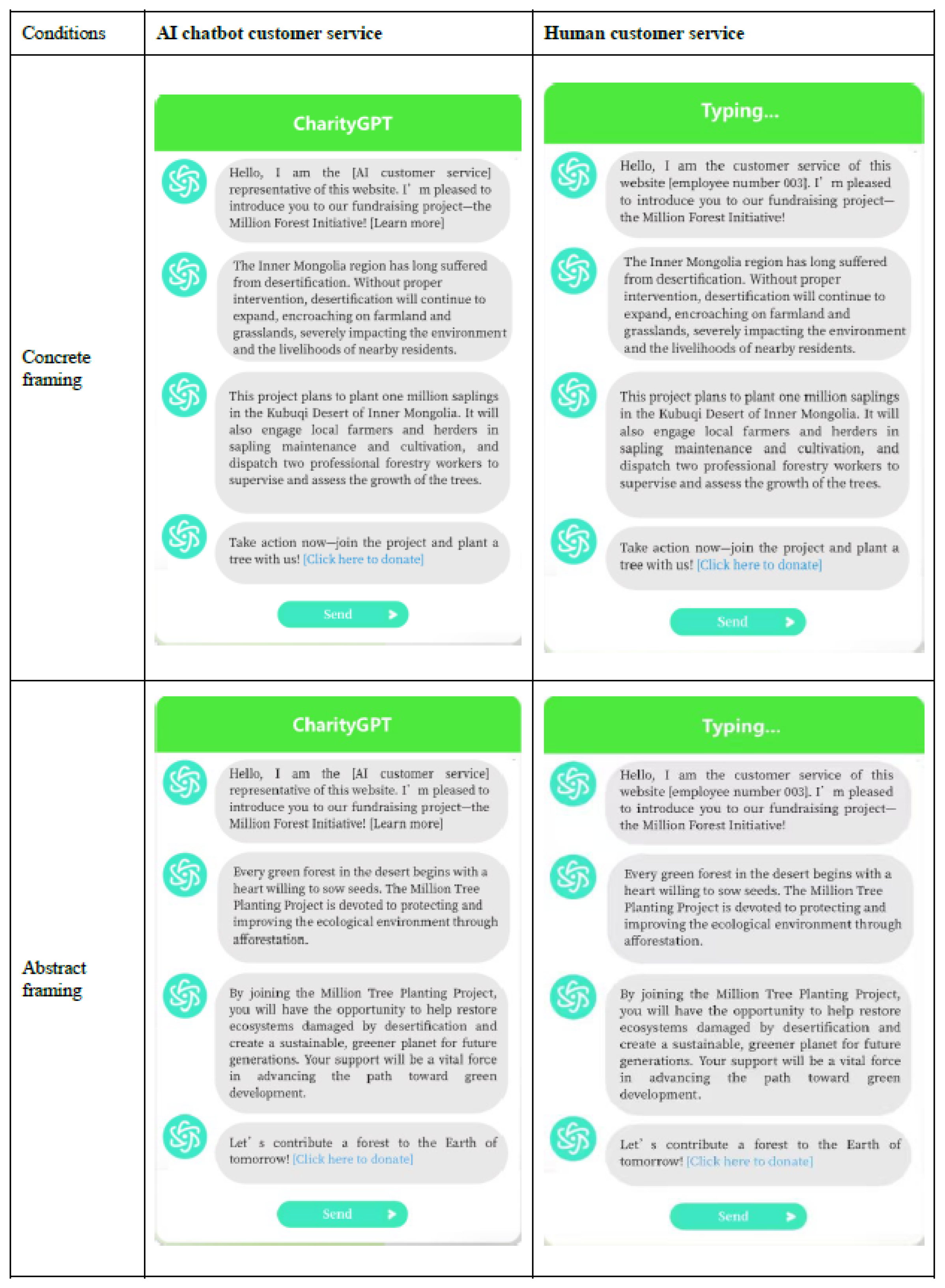

3.1. Prcedure, Materials and Pretest

“Hello, I am the [AI customer service] representative of this website. I’m pleased to introduce you to our fundraising project—the Million Forest Initiative! [Learn more] Every green forest in the desert begins with a heart willing to sow seeds. The Million Tree Planting Project is devoted to protecting and improving the ecological environment through afforestation. By joining the Million Tree Planting Project, you will have the opportunity to help restore ecosystems damaged by desertification and create a sustainable, greener planet for future generations. Your support will be a vital force in advancing the path toward green development. Let’s contribute a forest to the Earth of tomorrow! [Click here to donate]”

“Hello, I am the [AI customer service] representative of this website. I’m pleased to introduce you to our fundraising project—the Million Forest Initiative! [Learn more] The Inner Mongolia region has long suffered from desertification. Without proper intervention, desertification will continue to expand, encroaching on farmland and grasslands, severely impacting the environment and the livelihoods of nearby residents. This project plans to plant one million saplings in the Kubuqi Desert of Inner Mongolia. It will also engage local farmers and herders in sapling maintenance and cultivation, and dispatch two professional forestry workers to supervise and assess the growth of the trees. Take action now—join the project and plant a tree with us! [Click here to donate]”

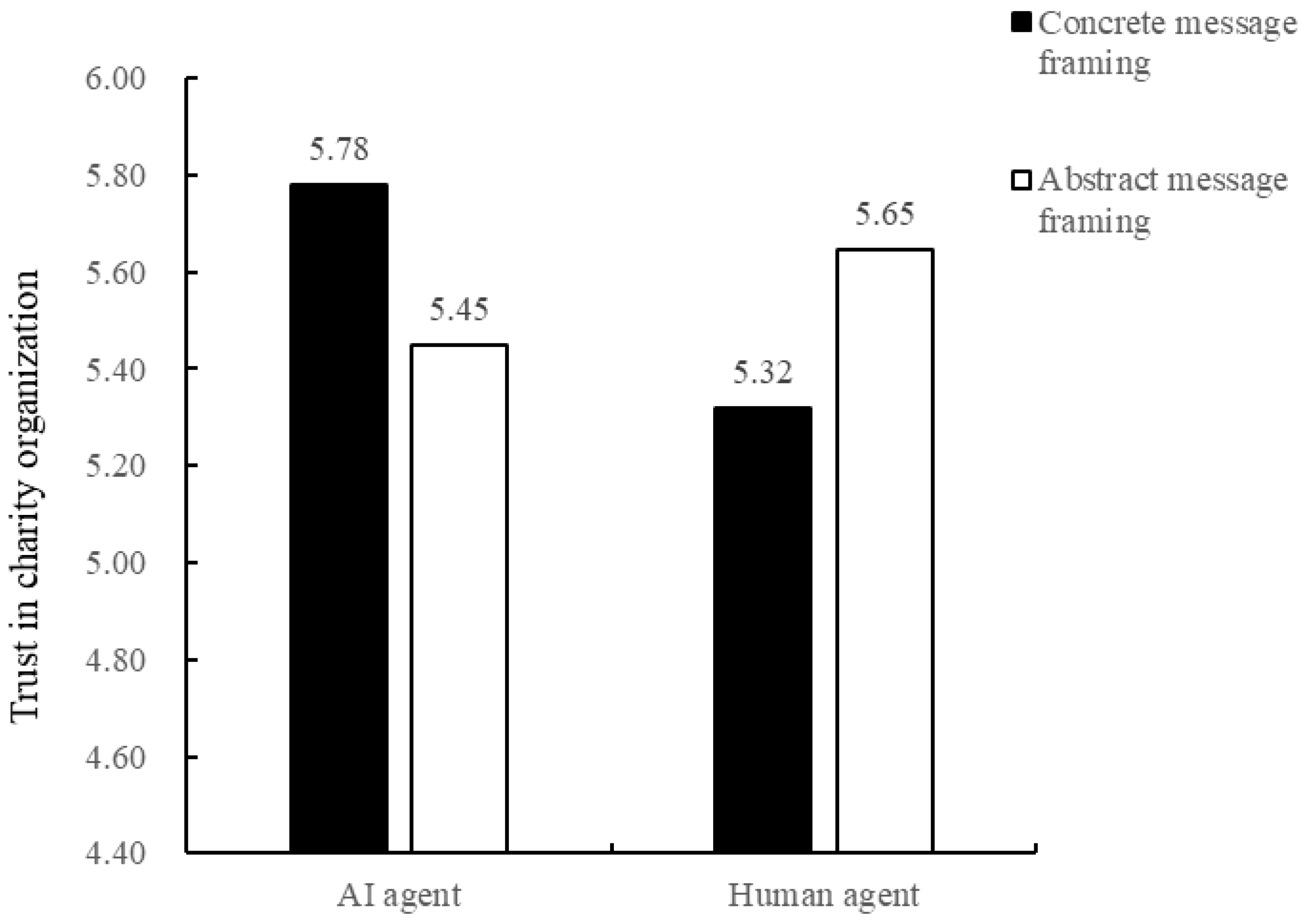

3.2. Results

3.3. Study 1 Discussion

4. Study 2a

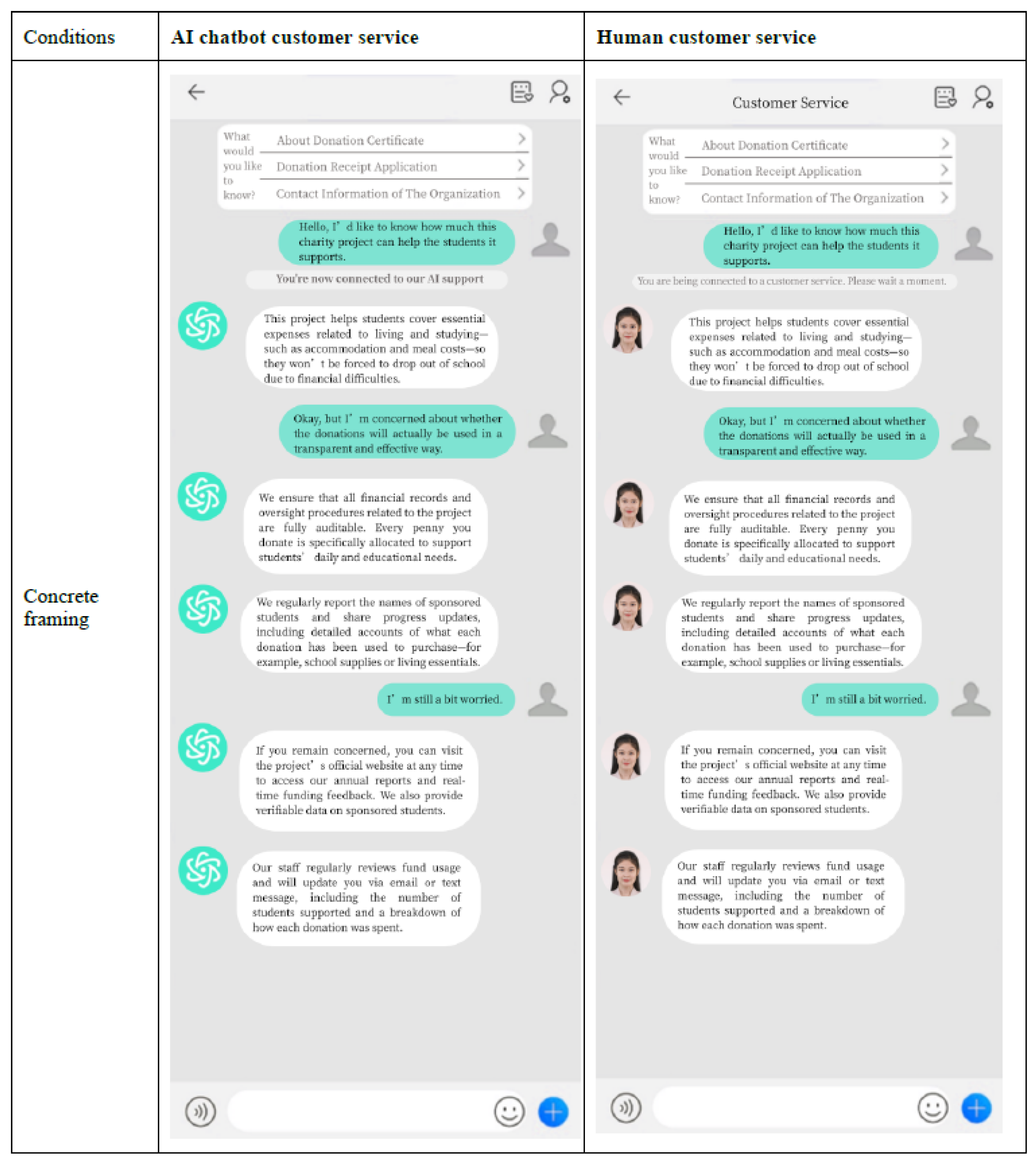

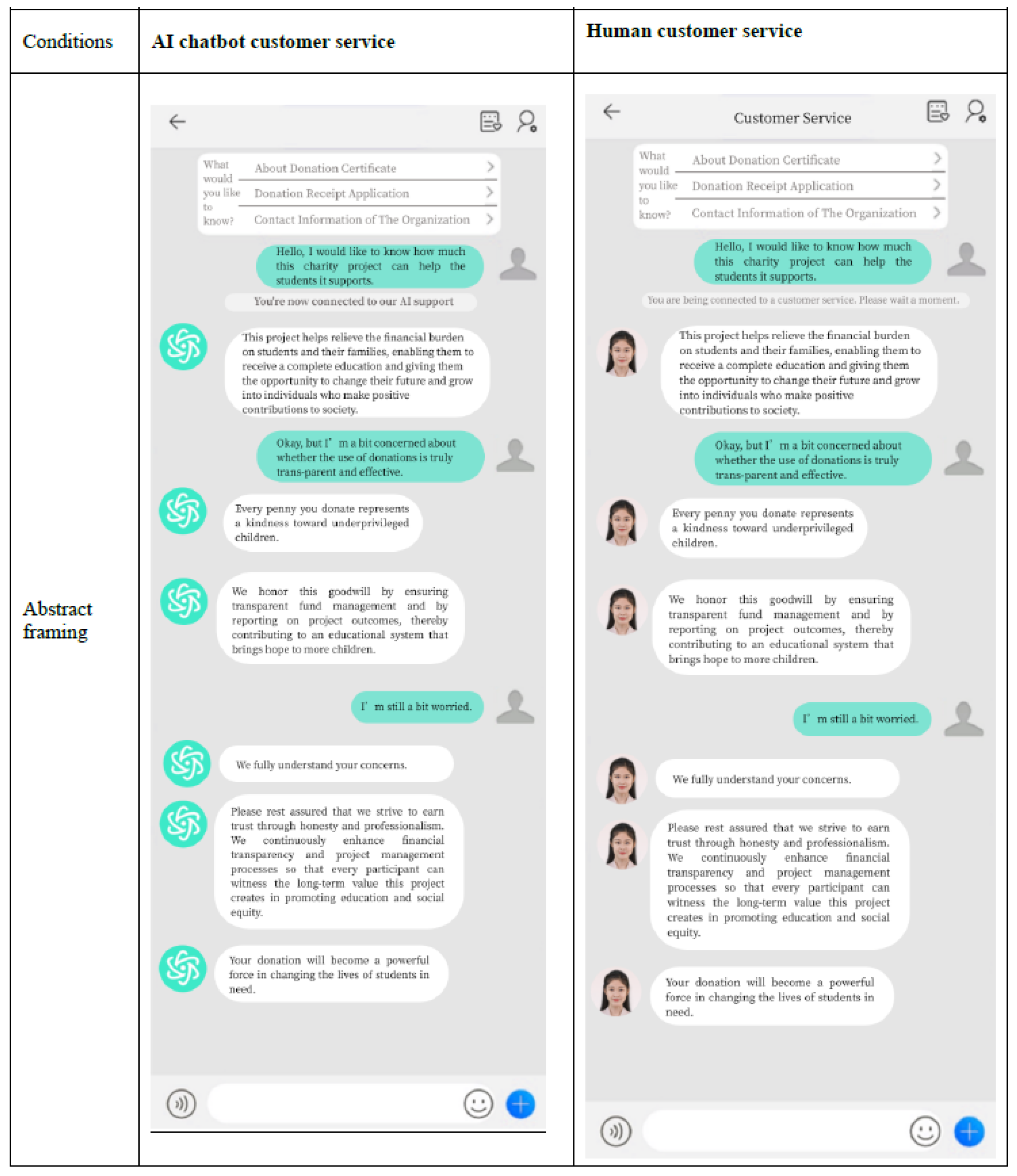

4.1. Procedure, Materials and Pretest

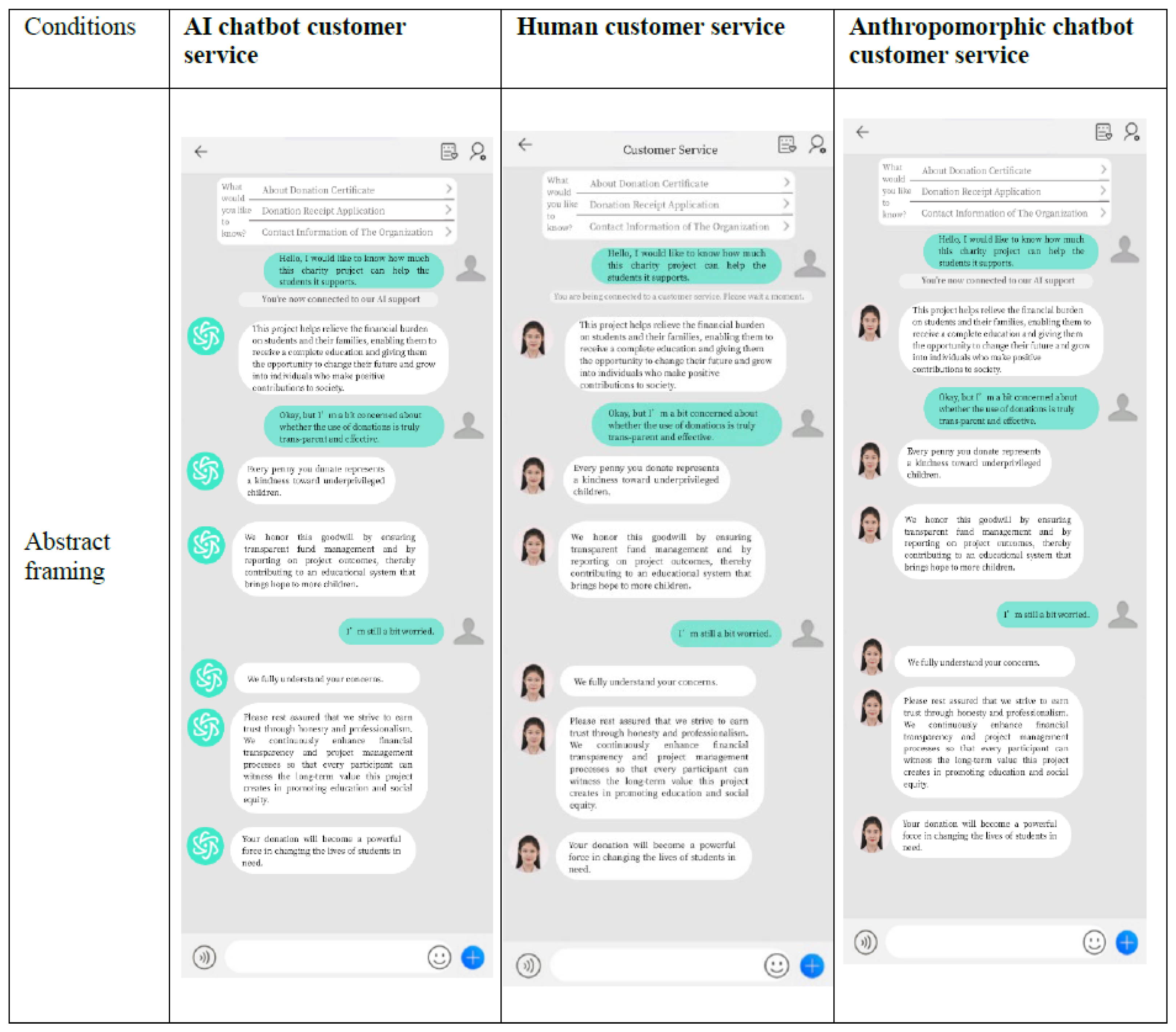

Q: Hello, I would like to know how much this charity project can help the students it supports.A: This project helps relieve the financial burden on students and their families, enabling them to receive a complete education and giving them the opportunity to change their future and grow into individuals who make positive contributions to society.(Round 1)

Q: Okay, but I’m a bit concerned about whether the use of donations is truly transparent and effective.A: Every penny you donate represents a kindness toward underprivileged children. We honor this goodwill by ensuring transparent fund management and by reporting on project outcomes, thereby contributing to an educational system that brings hope to more children.(Round 2)

Q: I’m still a bit worried.A: We fully understand your concerns. Please rest assured that we strive to earn trust through honesty and professionalism. We continuously enhance financial transparency and project management processes so that every participant can witness the long-term value this project creates in promoting education and social equity. Your donation will become a powerful force in changing the lives of students in need.(Round 3)

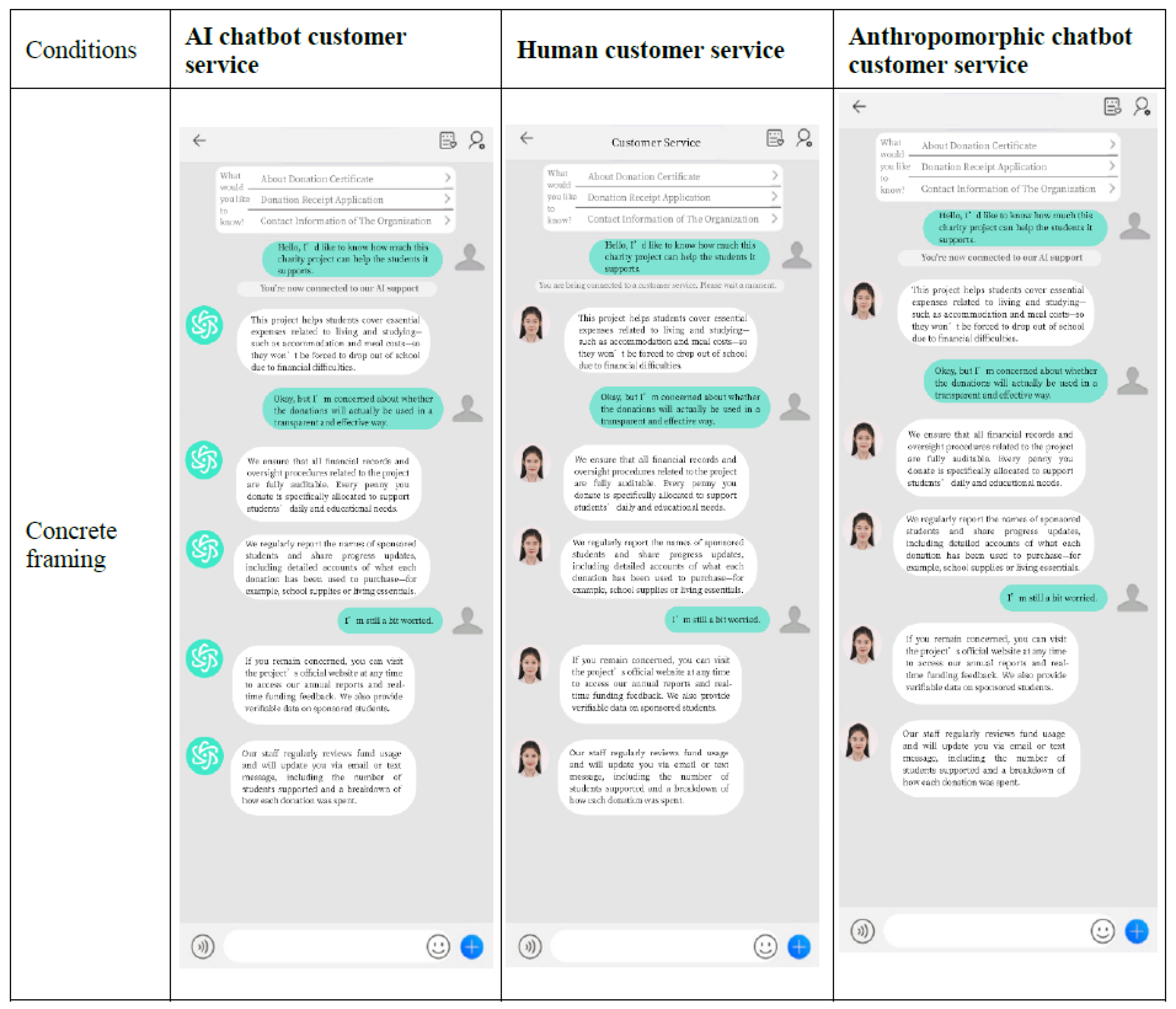

Q: Hello, I’d like to know how much this charity project can help the students it supports.A: This project helps students cover essential expenses related to living and studying—such as accommodation and meal costs—so they won’t be forced to drop out of school due to financial difficulties.(Round 1)

Q: Okay, but I’m concerned about whether the donations will actually be used in a transparent and effective way.A: We ensure that all financial records and oversight procedures related to the project are fully auditable. Every penny you donate is specifically allocated to support students’ daily and educational needs. We regularly report the names of sponsored students and share progress updates, including detailed accounts of what each donation has been used to purchase—for example, school supplies or living essentials.(Round 2)

Q: I’m still a bit worried.A: If you remain concerned, you can visit the project’s official website at any time to access our annual reports and real-time funding feedback. We also provide verifiable data on sponsored students. Our staff regularly reviews fund usage and will update you via email or text message, including the number of students supported and a breakdown of how each donation was spent.(Round 3)

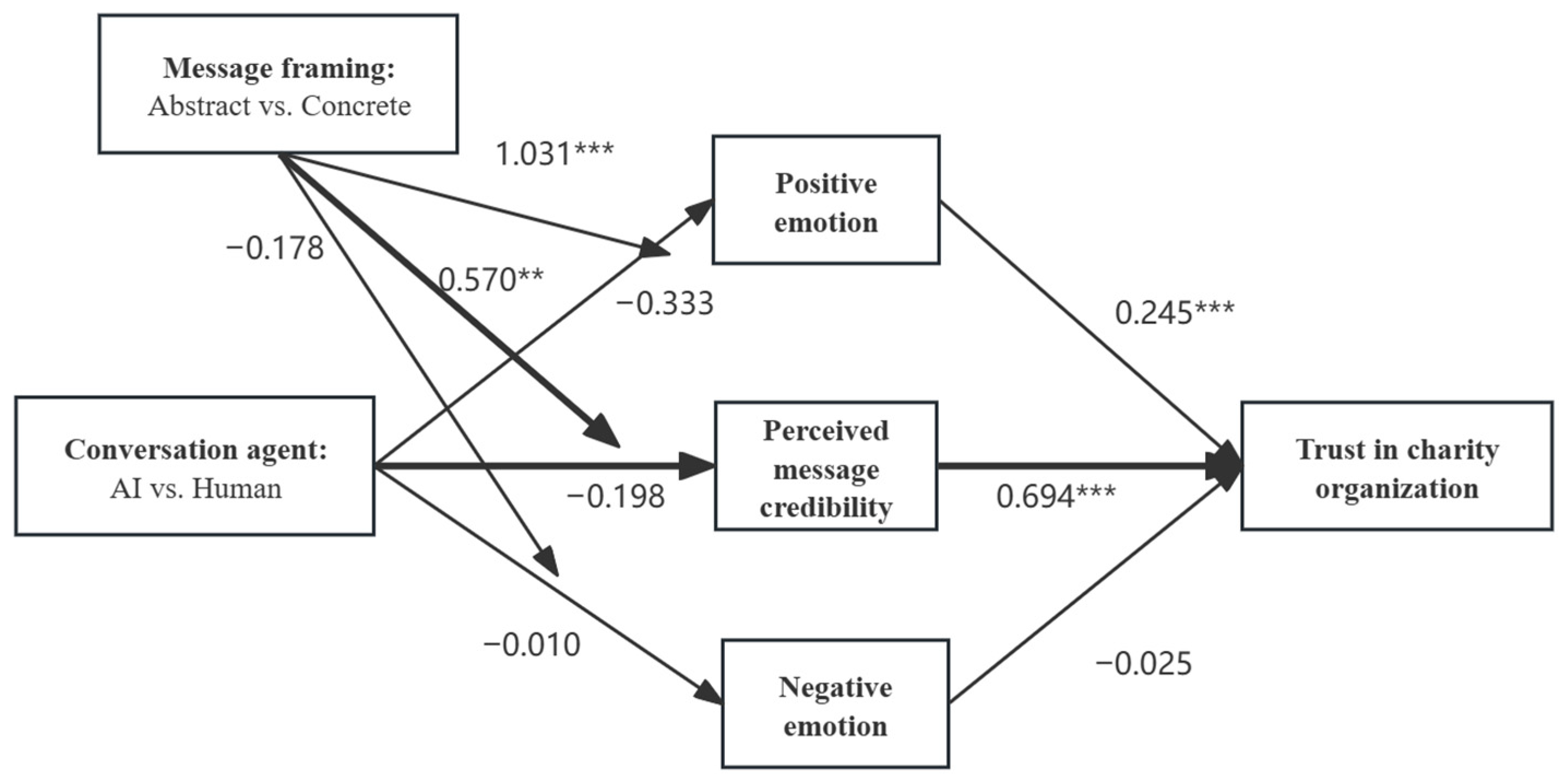

4.2. Results

4.3. Study 2a Discussion

5. Study 2b

5.1. Procedure, Materials and Pretest

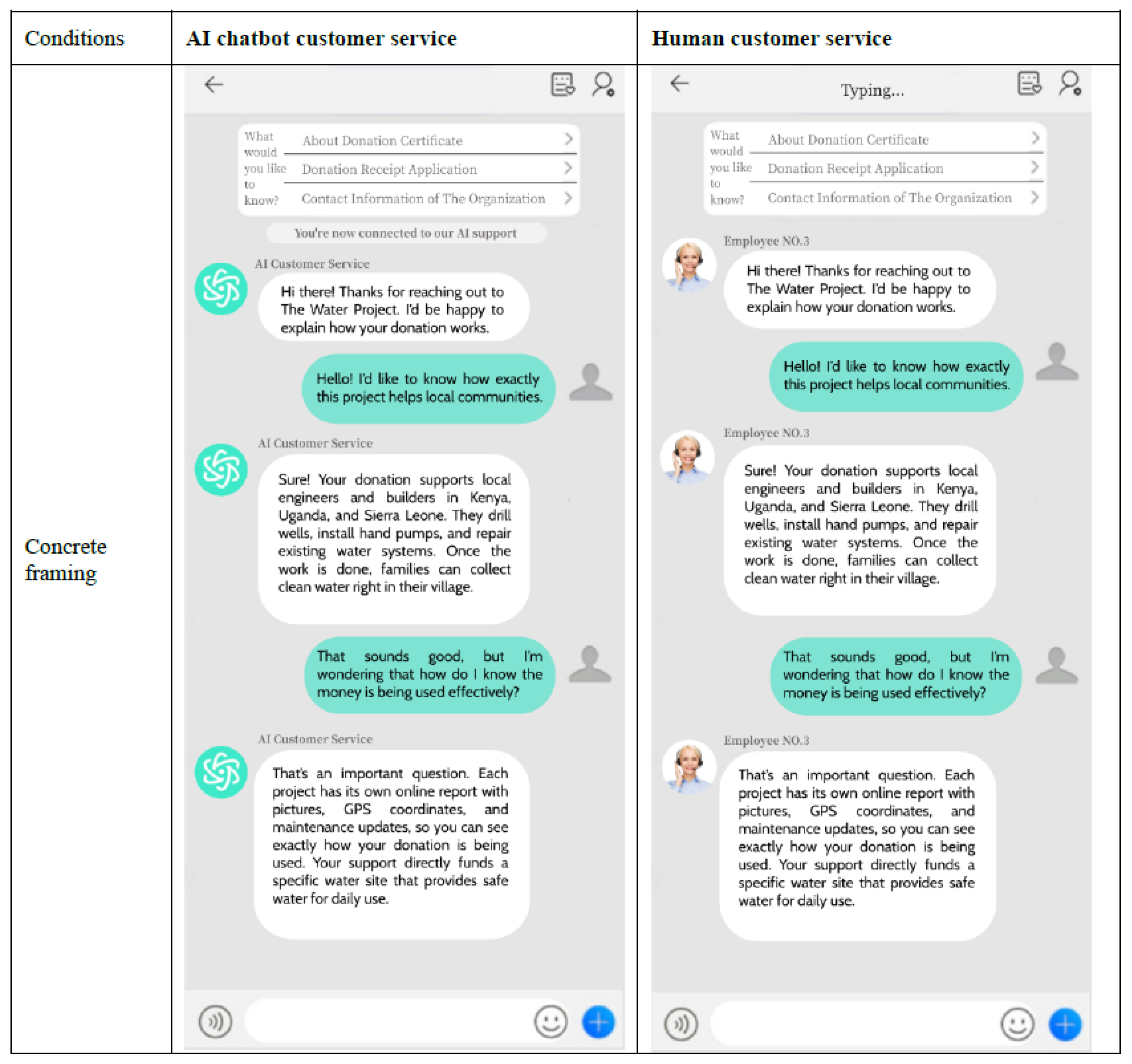

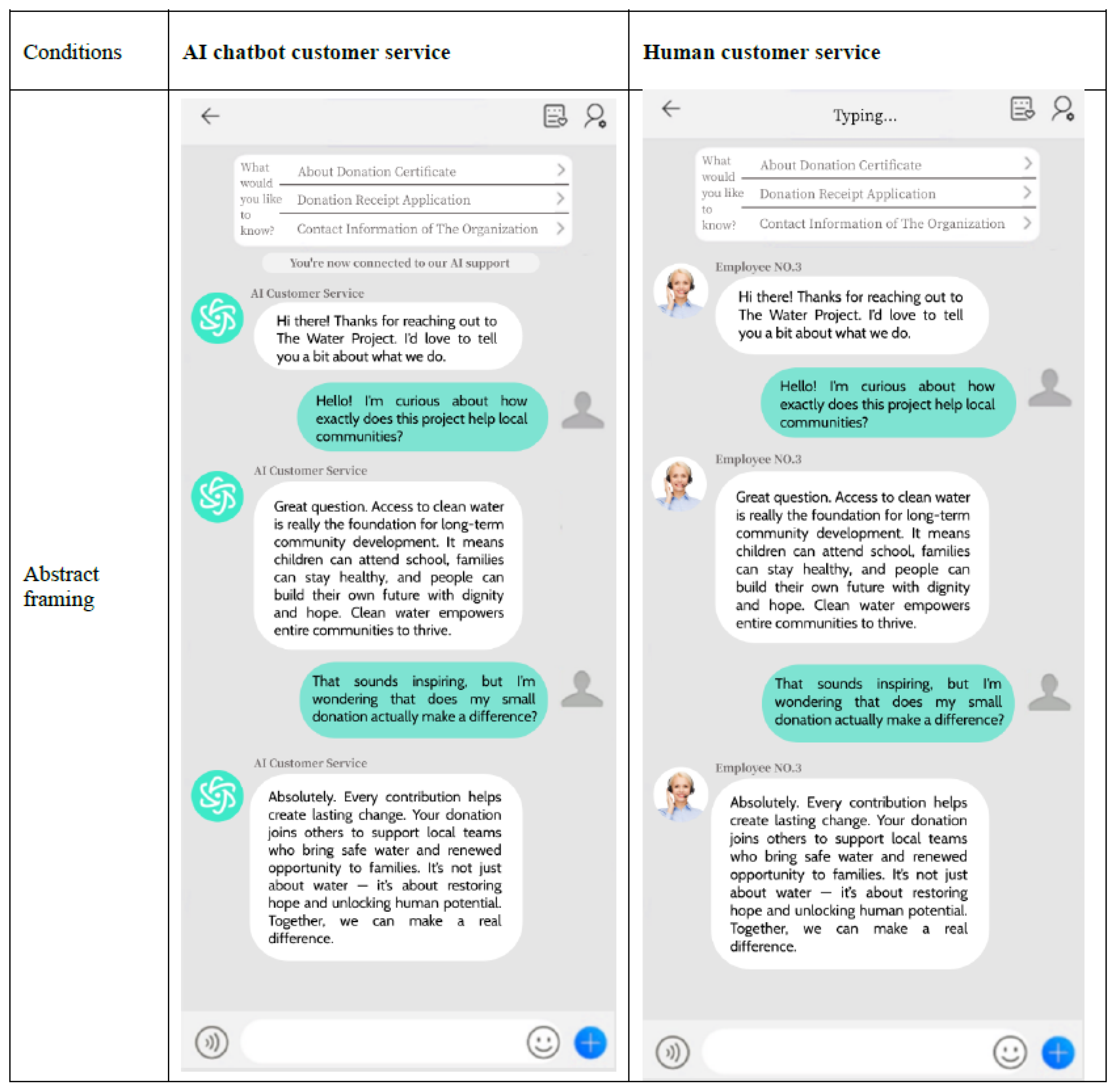

Customer Service: Hi there! I’m the AI (human) representative from The Water Project, and I’d love to share a bit about what we do.Q: Hello! I’m curious how exactly does this project help local communities?Customer Service: Great question. Access to clean water is really the foundation for long-term community development. It means children can attend school, families can stay healthy, and people can build their own future with dignity and hope. Clean water empowers entire communities to thrive.Q: That sounds inspiring, but I’m wondering does my small donation actually make a difference?Customer Service: Absolutely. Every contribution helps create lasting change. Your donation joins others to support local teams who bring safe water and renewed opportunity to families. It’s not just about water—it’s about restoring hope and unlocking human potential. Together, we can make a real difference.

Customer Service: Hi there! I’m the AI (human) representative from The Water Project, I’d be happy to explain how your donation works.Q: Hello! I’d like to know how exactly this project helps local communities.Customer Service: Sure! Your donation supports local engineers and builders in Kenya, Uganda, and Sierra Leone. They drill wells, install hand pumps, and repair existing water systems. Once the work is done, families can collect clean water right in their village.Q: That sounds good, but I’m wondering how do I know the money is being used effectively?Customer Service: That’s an important question. Each project has its own online report with pictures, GPS coordinates, and maintenance updates, so you can see exactly how your donation is being used. Your support directly funds a specific water site that provides safe water for daily use.

5.2. Results

5.3. Study 2b Discussion

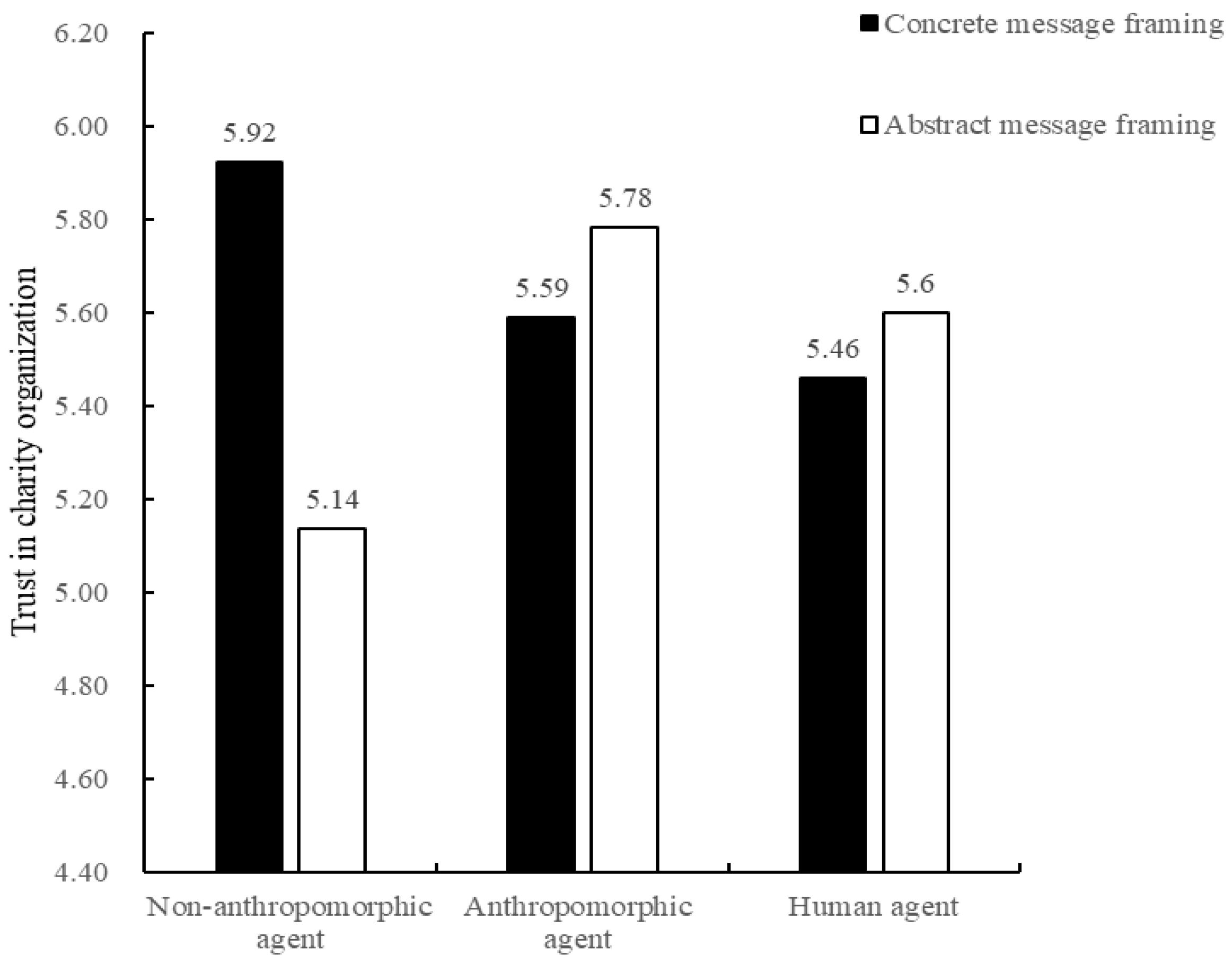

6. Study 3

6.1. Procedure and Materials

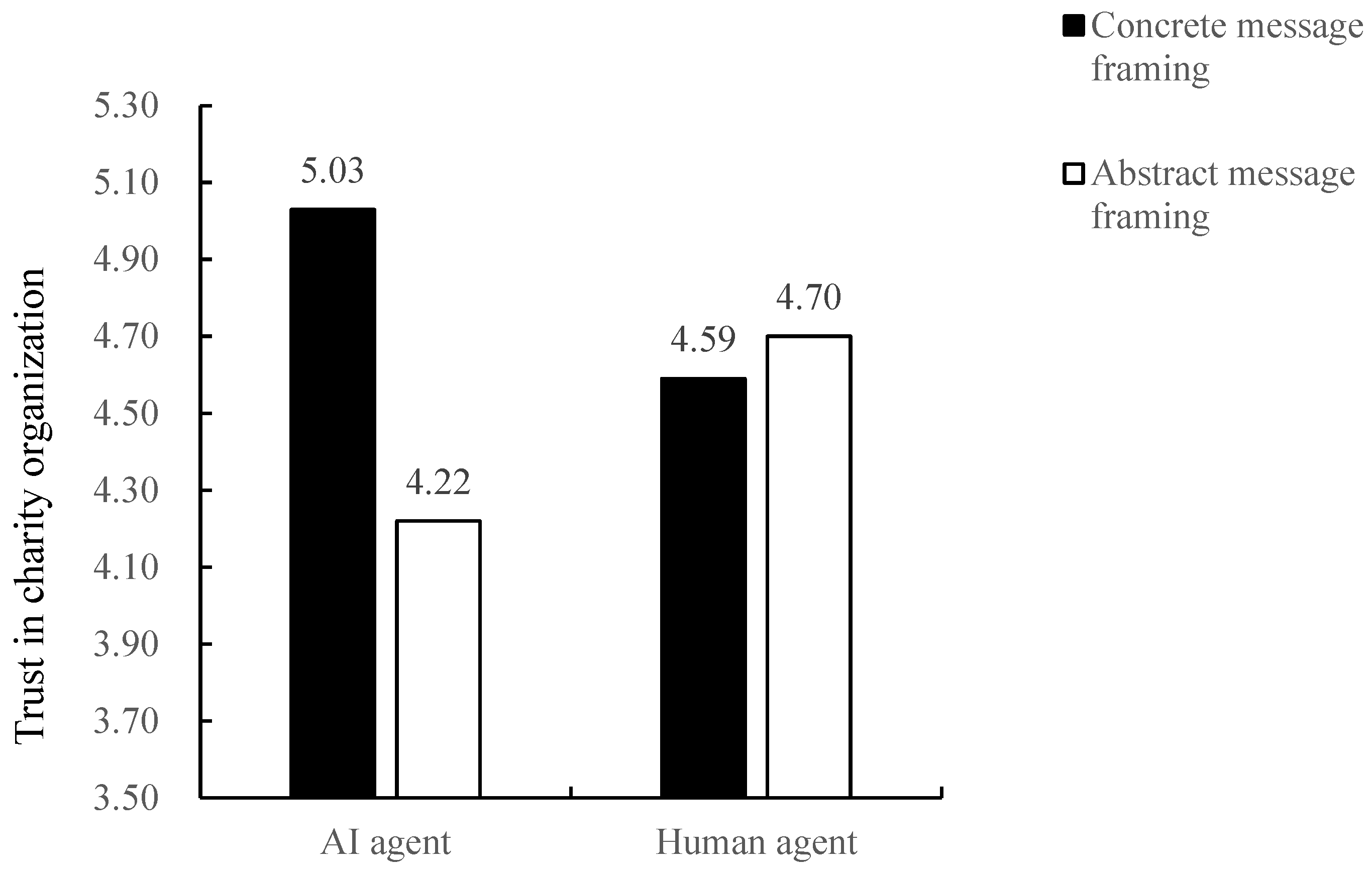

6.2. Results

6.3. Study 3 Discussion

7. General Discussion

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Variables | Measures | Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived message credibility (Study 2a/b and 3) [86] | To what extent do you feel that this AI/human agent is … | α = 0.923 (Study 2a); α = 0.965 (Study 2b); α = 0.914 (Study 3) |

| Dependable—Undependable Honest—Dishonest Reliable—Unreliable Sincere—Insincere Trustworthy—Untrustworthy Expert—Not an expert Experienced—Inexperienced Knowledgeable—Unknowledgeable Qualified—Unqualified Skilled—Unskilled | ||

| Response format: 7-point Stapel scale (1 = strongly agree with the statement on the left, 7 = strongly agree with the statement on the right). | ||

| Trust in charitable organization (Study 1, 2 a/b, 3) [78]; | I have no doubt this charitable organization can be trusted. I feel that this charitable organization is reliable. I trust this charitable organization. Response format: 7-point Likert scale (1 = Definitely not, 7 = Definitely yes) | α = 0.834 (Study 1); α = 0.825 (Study 2a); α = 0.955 (Study 2b); α = 0.845 (Study 3) |

| Donation intention (Study 1, 2 a/b, 3) [79] | I am willing to donate to this project through the organization. I am likely to donate to this project through the organization. Response format: 7-point Likert scale (1 = Definitely not, 7 = Definitely yes) | α = 0.807 (Study 1); α = 0.825 (Study 2a); α = 0.964 (Study 2b); α = 0.750 (Study 3) |

| Positive emotion (Study 2 a/b) [87] | Your conversation with the online customer service … made you feel happy. elicited positive feelings. elicited feelings of joy. left you with a good feeling. (Response format: 7-point Likert scale, 1= Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) | α = 0.926 |

| Negative emotion (Study 2 a/b) [87] | Your conversation with the online customer service … made you feel sad. elicited negative feelings. Left you with a bad feeling (Response format: 7-point Likert scale, 1= Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) | α = 0.885 |

| Condition | N | Gender | Education | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest of Study 1 | ||||

| Concrete framing | 50 | 0.64 | 3.00 | 36.18 |

| Abstract framing | 50 | 0.54 | 2.86 | 37.14 |

| F-value | 1.02 | 0.80 | 0.17 | |

| p-value | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.68 | |

| Study 1 | ||||

| AI chatbot customer service concrete framing | 71 | 0.68 | 3.01 | 30.31 |

| AI chatbot customer service abstract framing | 67 | 0.66 | 3.12 | 31.99 |

| Human customer service concrete framing | 69 | 0.75 | 3.00 | 30.41 |

| Human customer service abstract framing | 70 | 0.77 | 3.04 | 31.93 |

| F-value | 1.08 | 0.65 | 1.26 | |

| p-value | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.29 | |

| Pretest of Study 2a | ||||

| Concrete framing | 49 | 0.61 | 2.96 | 36.82 |

| Abstract framing | 50 | 0.56 | 2.86 | 36.24 |

| F-value | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.06 | |

| p-value | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.81 | |

| Study 2a | ||||

| AI chatbot customer service concrete framing | 75 | 0.69 | 3.00 | 30.63 |

| AI chatbot customer service abstract framing | 75 | 0.65 | 3.01 | 29.47 |

| Human customer service concrete framing | 73 | 0.73 | 2.88 | 30.49 |

| Human customer service abstract framing | 76 | 0.68 | 3.04 | 31.32 |

| F-value | 0.31 | 0.82 | 0.75 | |

| p-value | 0.82 | 0.49 | 0.52 | |

| Pretest of Study 2b | ||||

| Concrete framing | 52 | 0.54 | 2.58 | 43.00 |

| Abstract framing | 45 | 0.44 | 2.36 | 46.53 |

| F-value | 0.78 | 1.01 | 1.83 | |

| p-value | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.18 | |

| Study 2b | ||||

| AI chatbot customer service concrete framing | 70 | 0.49 | 2.43 | 43.13 |

| AI chatbot customer service abstract framing | 70 | 0.59 | 2.66 | 42.86 |

| Human customer service concrete framing | 70 | 0.41 | 2.53 | 43.09 |

| Human customer service abstract framing | 69 | 0.43 | 2.66 | 45.28 |

| F-value | 1.65 | 0.72 | 0.54 | |

| p-value | 0.18 | 0.54 | 0.66 | |

| Study 3 | ||||

| AI chatbot customer service concrete framing | 66 | 0.65 | 2.97 | 32.52 |

| AI chatbot customer service abstract framing | 64 | 0.64 | 3.13 | 29.56 |

| Human customer service concrete framing | 69 | 0.65 | 2.93 | 32.70 |

| Human customer service abstract framing | 66 | 0.76 | 3.03 | 30.79 |

| Anthropomorphized AI chatbot customer service concrete framing | 65 | 0.62 | 3.00 | 31.89 |

| Anthropomorphized AI chatbot customer service abstract framing | 69 | 0.77 | 2.88 | 30.09 |

| F-value | 1.30 | 1.08 | 1.85 | |

| p-value | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.10 |

References

- Grand View Research. Conversational AI Market Size, Share|Industry Report, 2030. 2023. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/conversational-ai-market-report (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Climate Reality Project Climate Reality’s New Rapid Response Team Is a Facebook Bot for Good, Not Evil. CleanTechnica 2017. Available online: https://www.climaterealityproject.org/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Winstead, E. Can AI Chatbots Correctly Answer Questions About Cancer?—NCI. Cancer Currents Blog 2023. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2023/chatbots-answer-cancer-questions (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Arotherham. New AI Newsletter—Leading Indicator: AI in Education. Eduwonk 2024. Available online: https://www.eduwonk.com/2024/06/new-ai-newsletter-from-bellwether-leading-indicator-ai-in-education.html (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Sundar, S.S. Rise of machine agency: A framework for studying the psychology of human–AI interaction (HAII). J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2020, 25, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Eastin, M.S. Birds of a feather flock together: Matched personality effects of product recommendation chatbots and users. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Syahrivar, J.; Simay, A.E. Unveiling the influence of anthropomorphic chatbots on consumer behavioral intentions: Evidence from China and Indonesia. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial—What is an interactive marketing perspective and what are emerging research areas? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Fei, Z.; He, Y.; Yang, Z. How human-chatbot interaction impairs charitable giving: The role of moral judgment. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 178, 849–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Huang, M. Can personalized recommendations in charity advertising boost donation? The role of perceived autonomy. J. Advert. 2022, 53, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Priluck, R. Consumer responses to generative AI chatbots versus search engines for product evaluation. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Understanding the impact of artificial intelligence on the justice of charitable giving: The moderating role of trust and regulatory orientation. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 2624–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, S.; Cheah, I.; Thaichon, P. The power of flattery: Enhancing prosocial behavior through virtual influencers. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1629–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.; Valsesia, F.; Segal, S. Assessing AI receptivity through a persuasion knowledge lens. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2024, 58, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.H.; Hsieh, J.-K.; Kumar, S. Does the verified badge of social media matter? The perspective of trust transfer theory. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir, D.M.; Bulut, Z.A. Business and customer-based chatbot activities: The role of customer satisfaction in online purchase intention and intention to reuse chatbots. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2961–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Cong, R. Artificial intelligence disclosure in cause-related marketing: A persuasion knowledge perspective. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietvorst, B.J.; Simmons, J.P.; Massey, C. Supplemental material for algorithm aversion: People erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2015, 144, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, C.; Cian, L. Artificial intelligence in utilitarian vs. hedonic contexts: The “word-of-machine” effect. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Baek, E. Let Virtual creatures stay virtual: Tactics to increase trust in virtual influencers. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.W.; Park, J.; Park, H. How can I trust you if you’re fake? Understanding human-like virtual influencer credibility and the role of textual social cues. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 730–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarella, S.; Torromino, G.; Gagliardi, D.; Rossi, D.; Babiloni, F.; Cartocci, G. Investigating the negative bias towards artificial intelligence: Effects of prior assignment of AI-authorship on the aesthetic appreciation of abstract paintings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 137, 107406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, R.J.; Cho, S.Y.; Tsai, W.S. Demystifying computer-generated imagery (CGI) influencers: The effect of perceived anthropomorphism and social presence on brand outcomes. J. Interact. Advert. 2022, 22, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.D.; Pallant, J.I.; Johnson, L.W. Exploring the impact of chatbots on consumer sentiment and expectations in retail. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitardi, V.; Marriott, H.R. Alexa, She’s not human but… Unveiling the drivers of consumers’ trust in voice—Based artificial intelligence. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 626–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.S.; Nass, C. Source Orientation in human-computer interaction: Programmer, networker, or independent social actor. Commun. Res. 2000, 27, 683–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, S. Social- or task-oriented: How does social crowding shape consumers’ preferences for chatbot conversational styles? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 641–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, M.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Understanding influencer marketing: The role of congruence between influencers, products and consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, X. Chatbot or human? The impact of online customer service on consumers’ purchase intentions. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 2186–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamitov, M.; Rajavi, K.; Huang, D.-W.; Hong, Y. Consumer trust: Meta-analysis of 50 years of empirical research. J. Consum. Res. 2024, 51, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R.; Wiepking, P. Accuracy of self-reports on donations to charitable organizations. Qual. Quant. 2011, 45, 1369–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, S.; Horne, S. Giving to charity: Questioning the donor decision process. J. Consum. Mark. 1996, 13, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Chakrabarti, S. Charity donor behavior: A systematic literature review and research agenda. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2023, 35, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H.; Mitchell, K.V.; Hall, J.A.; Lothert, J.; Snapp, T.; Meyer, M. Empathy, expectations, and situational preferences: Personality influences on the decision to participate in volunteer helping behaviors. J. Pers. 1999, 67, 469–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquino, K.; Reed, A. The self-importance of moral identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brañas-Garza, P.; Capraro, V.; Rascón-Ramírez, E. Gender differences in altruism on mechanical Turk: Expectations and actual behaviour. Econ. Lett. 2018, 170, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.N.; Sharpe, D.L. The nature and causes of the U-shaped charitable giving profile. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2007, 36, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A. Older adults’ motivations for gift giving to charitable organizations: An exchange theory perspective. Psychol. Mark. 1996, 13, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, L.A.; Dovidio, J.F.; Piliavin, J.A.; Schroeder, D.A. Prosocial behavior: Multilevel perspectives. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoto, A.M. Processes of Community Change and Social Action; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-8058-4393-4. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.W.; Faro, D.; Burson, K.A. More for the many: The influence of entitativity on charitable giving. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 39, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryder, C.E.; Loewenstein, G.; Scheines, R. The donor is in the details. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 120, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D. E-Commerce: The role of familiarity and trust. Omega 2000, 28, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, W.; Becker, A.; Boenigk, S. The antecedents of charity trust and its influence on charity supportive behavior. J. Philanthr. Mark. 2021, 26, e1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. Developing and validating trust measures for E-commerce: An integrative typology. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 334–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavas, Z.R. A review on trust in human-robot interaction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2105.10045. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Qiu, L.; Kim, D.; Benbasat, I. Effects of rational and social appeals of online recommendation agents on cognition- and affect-based trust. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 86, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, A.; West, D.C.; Ford, J.B. Does perception matter? An empirical analysis of donor behaviour. Serv. Ind. J. 2004, 24, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, A. Cyber trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.J. Trust transfer on the world wide web. Org. Sci. 2003, 14, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyal, T.; Liberman, N. Morality and psychological distance: A construal level theory perspective. In The Social Psychology of Morality: Exploring the Causes of Good and Evil; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.-L.; Chung, H.F.L. Achieving close psychological distance and experiential value in the MarTech Servicescape: A mindfulness-oriented service perspective. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 358–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Brennan, E.; Gibson, L.A.; Tan, A.S.L.; Kybert-Momjian, A.; Liu, J.; Hornik, R. Predictive validity of an empirical approach for selecting promising message topics: A randomized-controlled study: Validating a message topic selection approach. J. Commun. 2016, 66, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J. The role of construal level in message effects research: A review and future directions. Commun. Theory 2019, 29, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Peng, X. Persuasive and Substantive: The impact of matching charity advertising appeal with numeric format on individual donation intentions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallacher, R.R.; Wegner, D.M. Levels of personal agency: Individual variation in action identification. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Duhachek, A. Artificial Intelligence and persuasion: A construal-level account. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, S.; Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, Global Edition; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Teeny, J.; Briñol, P.; Petty, R.E. The elaboration likelihood model: Understanding consumer attitude change. In Routledge International Handbook of Consumer Psychology; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Briñol, P.; Petty, R.E. Source factors in persuasion: A self-validation approach. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 20, 49–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackob, N. Credibility Effects. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Appelman, A.; Sundar, S.S. Measuring message credibility: Construction and validation of an exclusive scale. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2016, 93, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, J.K.; Birk, T.; Pfau, M. Nonverbal behaviors, persuasion, and credibility. Hum. Commun. Res. 1990, 17, 140–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, J.K.; Bonito, J.A.; Bengtsson, B.; Cederberg, C.; Lundeberg, M.; Allspach, L. Interactivity in human–computer interaction: A study of credibility, understanding, and influence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2000, 16, 553–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Keh, H.T.; Lee, A.Y. Shaping consumer preference using alignable attributes: The roles of regulatory orientation and construal level. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2019, 36, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, A.-K.; Weber, A. Can you believe it? The effects of benefit type versus construal level on advertisement credibility and purchase intention for organic food. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lee, M.K.O.; Liu, R.; Chen, J. Trust transfer in social media brand communities: The role of consumer engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waytz, A.; Cacioppo, J.; Epley, N. Who sees human? The stability and importance of individual differences in anthropomorphism. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, T.; Nourbakhsh, I.; Dautenhahn, K. A Survey of socially interactive robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2003, 42, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.S.; Kim, J. Machine heuristic: When we trust computers more than humans with our personal information. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi, G.; Vannucci, V.; Mazzoli, V.; Donvito, R. I, Chatbot! The impact of anthropomorphism and gaze direction on willingness to disclose personal information and behavioral intentions. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 1372–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Pinxteren, M.M.E.; Wetzels, R.W.H.; Rüger, J.; Pluymaekers, M.; Wetzels, M. Trust in humanoid robots: Implications for services marketing. J. Serv. Mark. 2019, 33, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, E.; Alavi, S.; Bezençon, V. Trojan horse or useful helper? A relationship perspective on artificial intelligence assistants with humanlike features. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 1153–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waytz, A.; Heafner, J.; Epley, N. The mind in the machine: Anthropomorphism increases trust in an autonomous vehicle. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 52, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Xia, C. Narrative information on secondhand products in E-commerce. Mark. Lett. 2022, 33, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Kashyap, R.; Zhou, N.; Yang, Z. Brand trust as a second-order factor: An alternative measurement model. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 50, 817–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstein, A.; Kronrod, A. Does sparing the rod spoil the child? How praising, scolding, and an assertive tone can encourage desired behaviors. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 53, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.W.; Thompson, D.V. Is there a substitute for direct experience? Comparing consumers’ preferences after direct and indirect product experiences. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Keh, H.T. I implement, they deliberate: The matching effects of point of view and mindset on consumer attitudes. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, A.; Isaac, M.S.; Wang, R.J.-H. Construal matching in online search: Applying text analysis to illuminate the consumer decision journey. J. Mark. Res. 2021, 58, 1101–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semin, G.R.; Fiedler, K. The cognitive functions of linguistic categories in describing persons: Social cognition and language. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, C.P.; Givi, J. The AI-authorship effect: Understanding authenticity, moral disgust, and consumer responses to AI-generated marketing communications. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 186, 114984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, L.; Singaraju, S.P.; Niininen, O. Consumer responses to AI-generated charitable giving Ads. J. Advert. 2023, 52, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Muro, F.; Murray, K.B. An arousal regulation explanation of mood effects on consumer choice. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnen, U.; Oyserman, D. Thinking about the self influences thinking in general: Cognitive consequences of salient self-concept. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 38, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, K.C.; Tan, T.; Jackson, J.C.; Shariff, A.; Gray, K. Cultural differences in people’s reactions and applications of robots, algorithms, and artificial intelligence. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2023, 19, 859–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, B.D.; Ewell, P.J.; Brauer, M. Data quality in online human-subjects research: Comparisons between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabholkar, P.A.; van Dolen, W.M.; de Ruyter, K. A dual-sequence framework for B2C relationship formation: Moderating effects of employee communication style in online group chat. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 145–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid Saeed, M.; Khan, H.; Lee, R.; Lockshin, L.; Bellman, S.; Cohen, J.; Yang, S. Construal level theory in advertising research: A systematic review and directions for future research. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 183, 114870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhou, X.; Chen, C.; Wu, D.; Zhou, H.; Dong, X.; Cao, L.; Lu, J.G. AI aversion or appreciation? A capability–personalization framework and a Meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2025, 151, 580–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo, N.; Bos, M.; Lehmann, D. Task-dependent algorithm aversion. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambino, A.; Fox, J.; Ratan, R.A. Building a stronger CASA: Extending the computers are social actors paradigm. Hum.-Mach. Commun. 2020, 1, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Harris, G. From tools to trusted allies: Understanding how IoT devices foster deep consumer relationships and enhance CRM. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. (Ed.) The Palgrave Handbook of Interactive Marketing; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-14960-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, W.-H.S.; Liu, Y.; Chuan, C.-H. How chatbots’ social presence communication enhances consumer engagement: The mediating role of parasocial interaction and dialogue. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 460–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, K.C.; Eng, A.; Gray, K. Machine replacement: A mind-role fit perspective. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2025, 12, 239–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, N.; Rosenkrans, S. Nonprofit AI: A Comprehensive Guide to Implementing Artificial Intelligence for Social Good; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lalot, F.; Bertram, A.-M. When the bot walks the talk: Investigating the foundations of trust in an artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2025, 154, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Najaf, M. Interactivity, humanness, and trust: A psychological approach to ai chatbot adoption in e-commerce. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Luo, J.; Lan, T. An empirical assessment of a modified artificially intelligent device use acceptance model—From the task-oriented perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 975307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lei, J. I will recommend a salad but choose a burger for you: The effect of decision tasks and social distance on food decisions for others. J. Appl. Bus. Behav. Sci. 2025, 1, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, T.; Huang, E.; Jin, X. The effects of public health emergencies on altruistic behaviors: A dilemma arises between safeguarding personal safety and helping others. J. Appl. Bus. Behav. Sci. 2025, 1, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robiady, N.D.; Windasari, N.A.; Nita, A. Customer engagement in online social crowdfunding: The influence of storytelling technique on donation performance. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Weng, J.-Y.; Chen, K.Y. Interactive marketing and instant donations: Psychological drivers of virtual YouTuber followers’ contributions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Cui, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, D. Who says what? How message appeals shape virtual- versus human-influencers’ impact on consumer engagement. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hypothesis | Statistical Indicator | Study 1 | Study 2a | Study 2b | Study 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: When the communication agent is an AI chatbot (vs. a human), using concrete (vs. abstract) message framing will more effectively enhance consumers’ trust in the charitable organization. | effect size (η2) | 0.035 | 0.017 | 0.035 | ☐ |

| significance (p-value) | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.002 | ☐ | |

| H1b: When the communication agent is an AI chatbot (vs. a human), using concrete (vs. abstract) message framing will more effectively enhance consumers’ donation intention. | effect size (η2) | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.019 | ☐ |

| significance (p-value) | 0.013 | 0.041 | 0.020 | ☐ | |

| H2a: Perceived message credibility mediates the interactive effect of communication agent type (AI chatbot vs. human) and message framing type (concrete vs. abstract) on consumers’ trust in the charitable organization. | index of moderated mediation | ☐ | 0.578 | 0.489 | ☐ |

| 95% confidence interval | ☐ | [0.140, 1.026] | [0.080, 0.934] | ☐ | |

| H2b: Perceived message credibility mediates the interactive effect of communication agent type (AI chatbot vs. human) and message framing type (concrete vs. abstract) on consumers’ donation intention. | index of moderated mediation | ☐ | 0.611 | 0.496 | ☐ |

| 95% confidence interval | ☐ | [0.151, 1.065] | [0.088, 0.977] | ☐ | |

| H3a: The level of anthropomorphism moderates the interactive effect of communication agent type (AI chatbot vs. human) and message framing type (concrete vs. abstract) on consumers’ trust in charitable organizations via perceived information credibility. | index of moderated mediation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | 0.726 |

| 95% confidence interval | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | [0.434, 1.053] | |

| H3b: Anthropomorphism moderates the interactive effect of communication agent type (AI chatbot vs. human) and message framing type (concrete vs. abstract) on consumers’ donation intention via perceived information credibility. | index of moderated mediation | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | 0.658 |

| 95% confidence interval | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | [0.395, 0.972] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, J.; Si, J. When AI Chatbots Ask for Donations: The Construal Level Contingency of AI Persuasion Effectiveness in Charity Human–Chatbot Interaction. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040341

Sun J, Si J. When AI Chatbots Ask for Donations: The Construal Level Contingency of AI Persuasion Effectiveness in Charity Human–Chatbot Interaction. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(4):341. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040341

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Jin, and Jia Si. 2025. "When AI Chatbots Ask for Donations: The Construal Level Contingency of AI Persuasion Effectiveness in Charity Human–Chatbot Interaction" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 4: 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040341

APA StyleSun, J., & Si, J. (2025). When AI Chatbots Ask for Donations: The Construal Level Contingency of AI Persuasion Effectiveness in Charity Human–Chatbot Interaction. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(4), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040341