Trust or Skepticism? Unraveling the Communication Mechanisms of AIGC Advertisements on Consumer Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

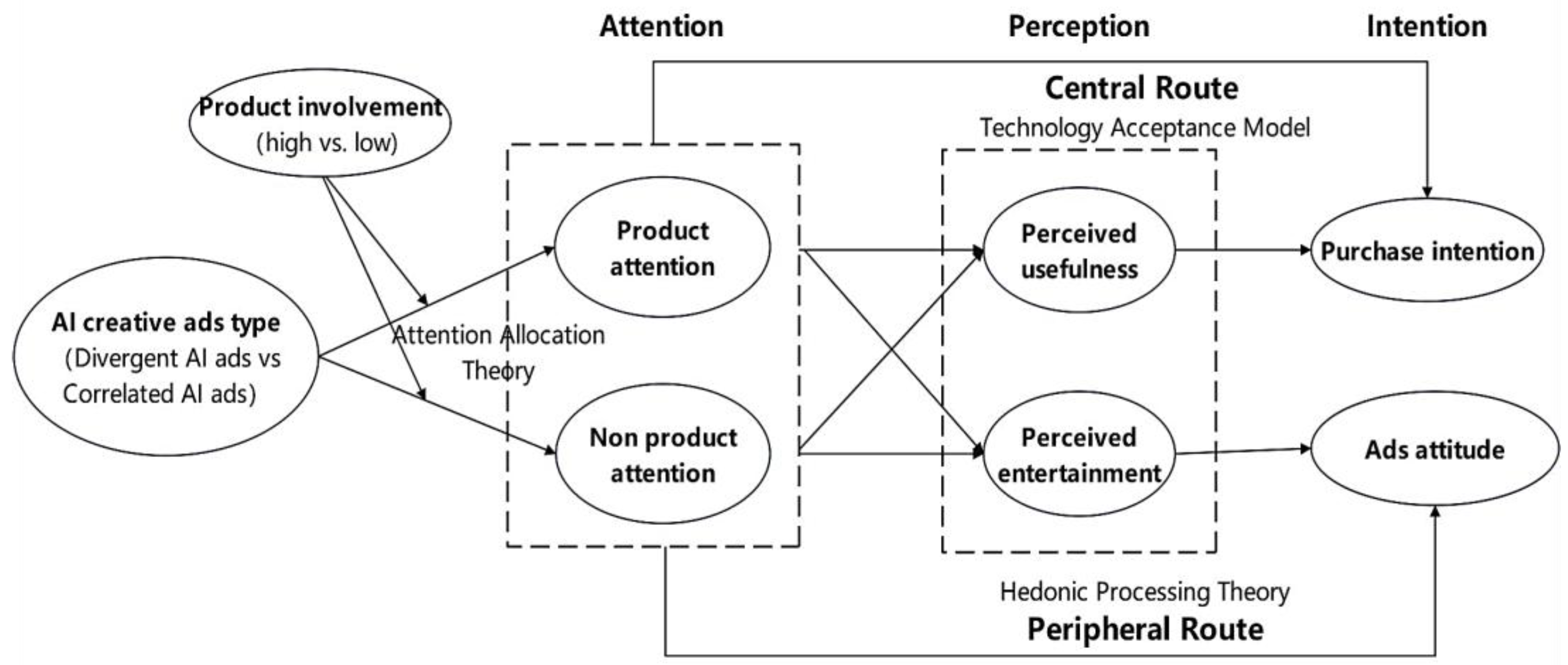

2.1. AIGC Advertising and Creative Advertising

2.2. Attention Allocation and Consumer Response

2.2.1. Product Attention

2.2.2. Non-Product Attention

2.3. Consumer Response

2.4. Mediating Effects of Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Entertainment

2.5. Moderating Effects of Product Involvement

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. Positive Effect of AI Ad Types on Attention

3.2. Positive Impact of AI Advertisements on Consumer Responses

- (1)

- Impact on Purchase Intention

- (2)

- Impact on Advertising Attitude

3.3. Mediating Effects of Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Entertainment

3.4. Moderating Effects of Product Involvement

4. Research Design Framework

5. Eye-Tracking Experiment

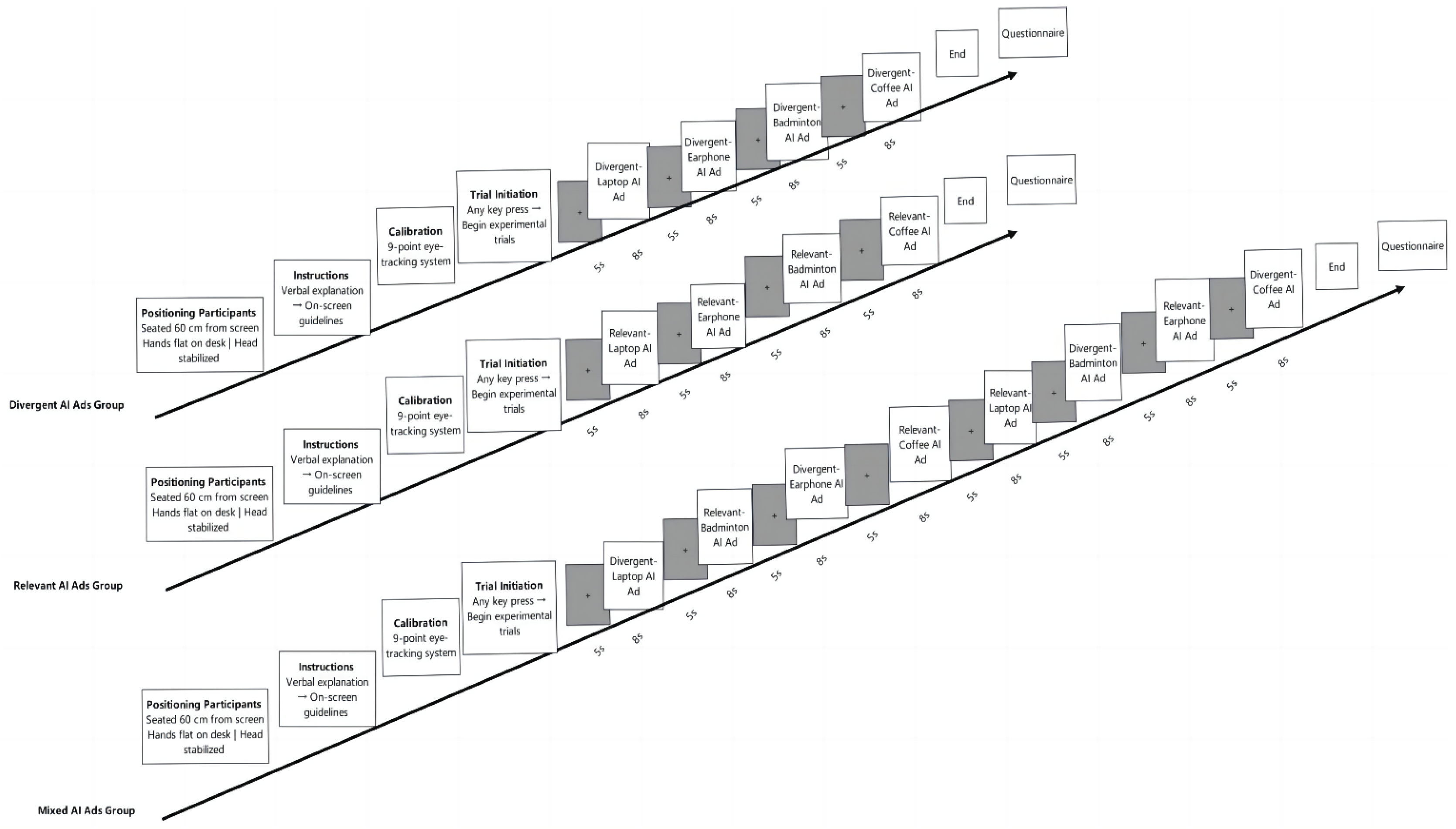

5.1. Experiment Design

5.2. Study 1: Eye-Tracking Experiment of AI Advertisement in the Divergent Ad Group and Relevant Ad Group

5.2.1. Participants

5.2.2. Apparatus and Design

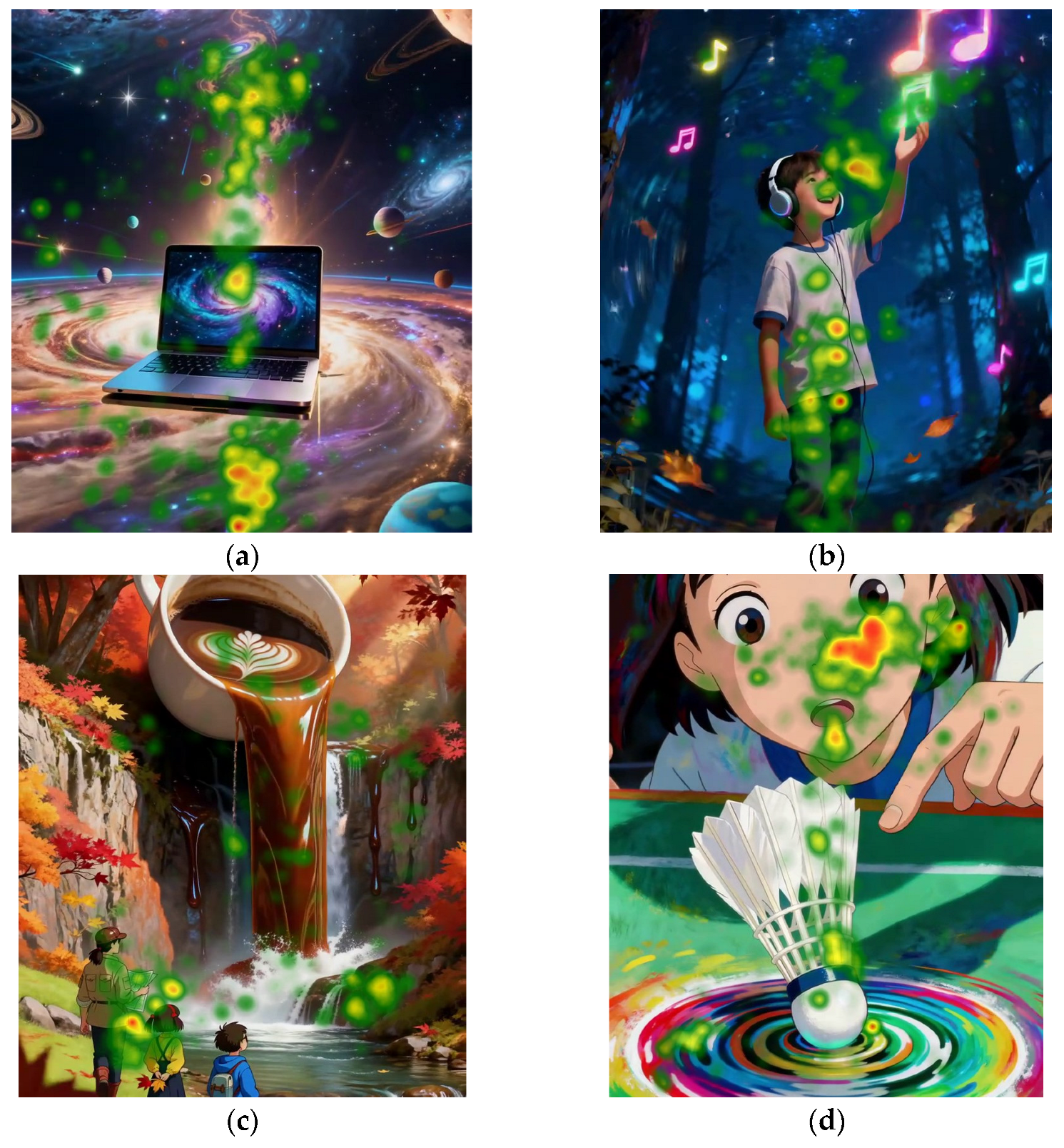

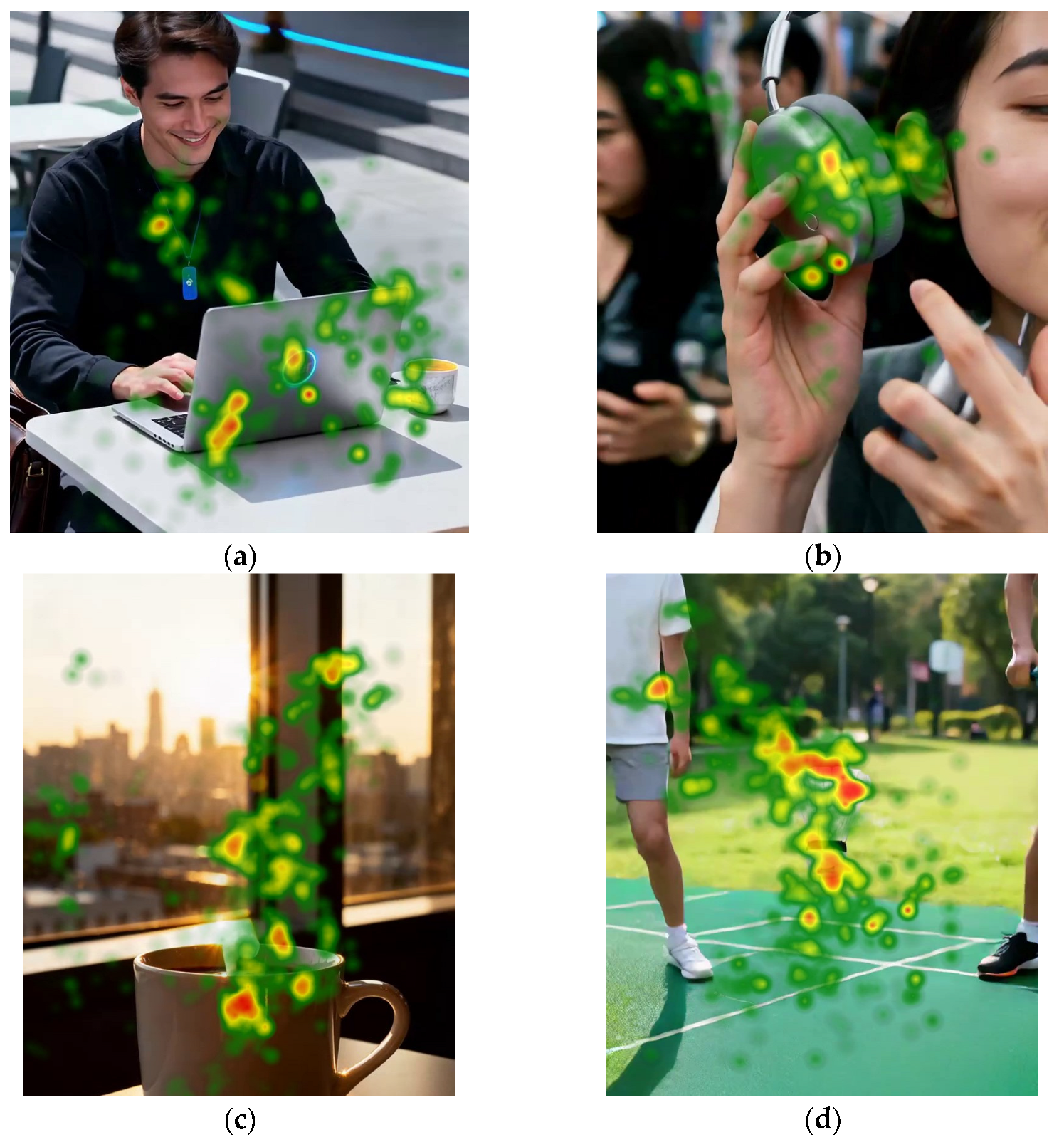

5.2.3. Stimuli Preparation

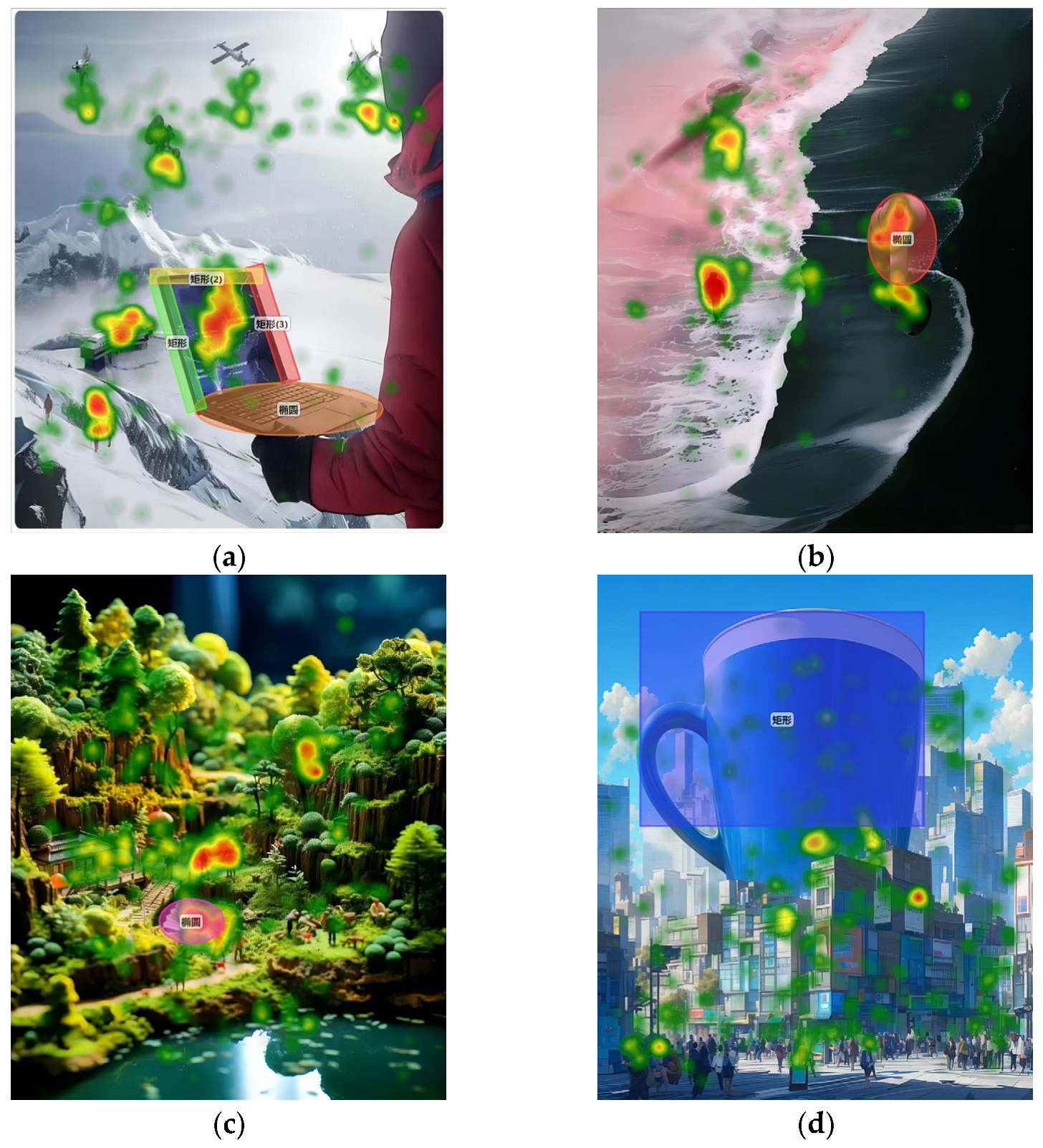

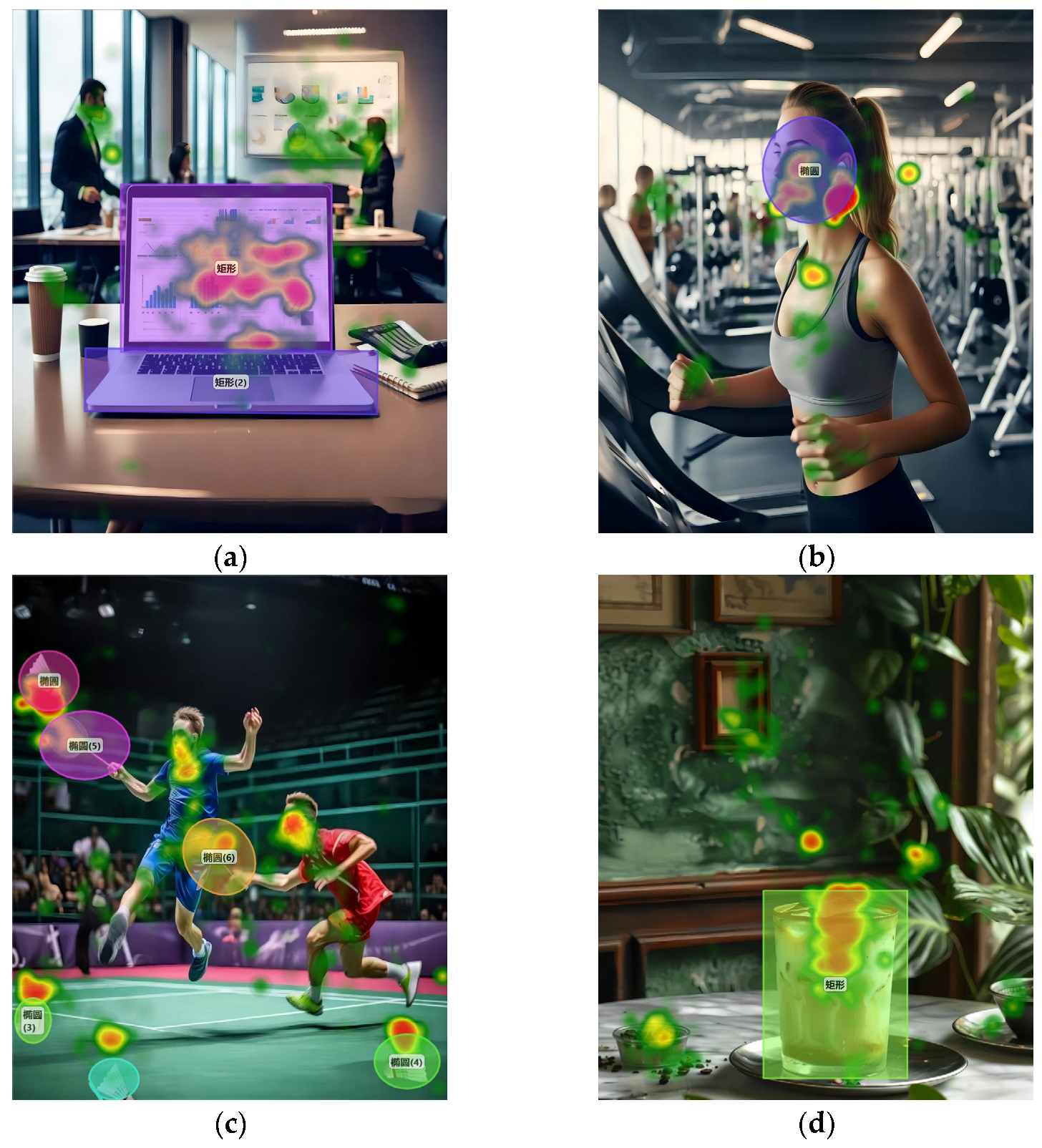

- 1.

- Product Selection

- 2.

- Ad Design

- 3.

- Visual feature quantification and matching

- 4.

- AI ad type Validation

5.2.4. Procedure

- Participants were seated 60 cm from a 24-inch LCD monitor, with head position stabilized using a chin rest to maintain a consistent viewing distance and ensure accurate binocular alignment with the eye-tracking system.

- The researcher provided standardized instructions: “You will now complete an eye-tracking session. Please browse the advertisements naturally as you would online. A gray fixation cross will appear for 5 s before each advertisement, which will then be displayed for 8 s.”

- A nine-point calibration procedure was performed, with accuracy validated through gaze-contingent verification trials. Data collection commenced only when the calibration error was confirmed to be below 0.10° of visual angle.

- Upon successful calibration, the core experimental phase began, during which participants viewed the advertisement stimuli under free-viewing conditions.

- Following the eye-tracking session, participants provided basic demographic information and completed a validated questionnaire assessing advertisement perception, advertising attitude, and purchase intention.

5.2.5. Data Processing

- (1)

- Fixation duration (total dwell time within AOIs), which reflects the depth of cognitive engagement with a specific area, with longer fixation durations indicating more extensive information processing [69];

- (2)

- Fixation count (frequency of visits to AOIs), which captures attentional salience, with higher counts suggesting stronger visual appeal of the area to consumers [68];

- (3)

- Fixation time ratio (dwell time in AOIs relative to total advertisement viewing time), which quantifies the priority of attention allocation, with higher ratios indicating that consumers are more inclined to direct their limited cognitive resources toward that area.

5.2.6. Data Analysis

- (1)

- Analysis of Single-Type Group (Divergent vs. Relevant Static Ads)

- (2)

- Supplementary Analysis of Dynamic AIGC Ads

5.3. Study 2: Eye-Tracking Experiment of AI Advertisement in the Mixed Ad Group

5.3.1. Participants

5.3.2. Design

5.3.3. Data Analysis

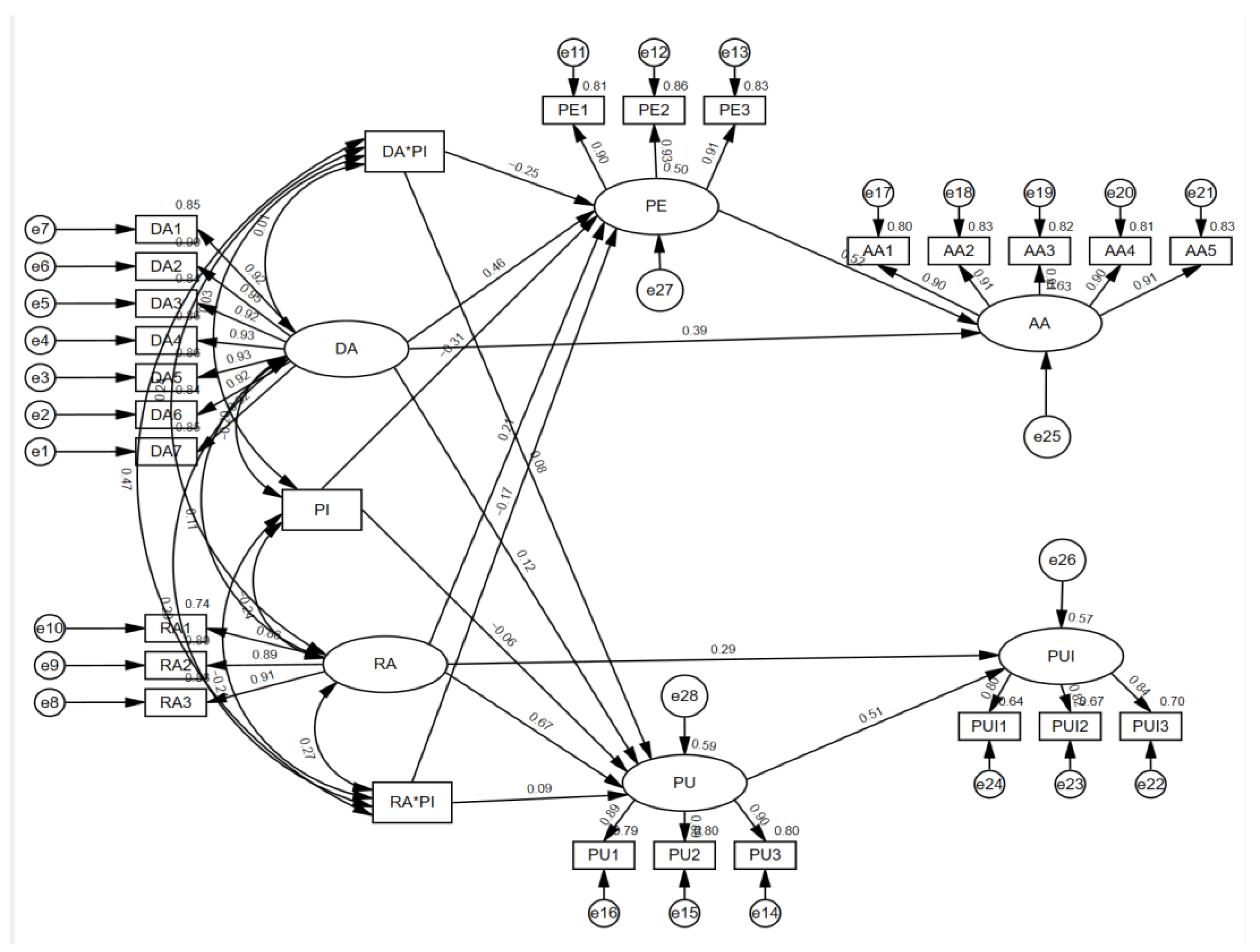

6. Empirical Research on the Consumer Perception Mechanism

6.1. Research Design

6.2. Measure Item

6.3. Reliability and Validity Tests

6.3.1. Common Method Bias Assessment

6.3.2. Reliability Analysis

6.3.3. Validity Analysis

6.4. Descriptive Statistics

6.5. Model Test

6.5.1. Model Fit Assessment

6.5.2. Main Effects Test

6.5.3. Mediating Effects Test

- Perceived entertainment mediated the relationship between divergent advertising and advertising attitude (effect size = 0.233, Boot SE = 0.018, 95% CI [0.189, 0.224], z = 12.434, p < 0.01).

- Perceived usefulness mediated the relationship between divergent advertising and purchase intention (effect size = 0.034, Boot SE = 0.009, 95% CI [0.027, 0.061], z = 3.871, p < 0.01).

- Perceived entertainment mediated the relationship between relevant advertising and advertising attitude (effect size = 0.087, Boot SE = 0.013, 95% CI [0.057, 0.108], z = 6.667, p < 0.01).

- Perceived usefulness mediated the relationship between relevant advertising and purchase intention (effect size = 0.253, Boot SE = 0.019, 95% CI [0.252, 0.325], z = 13.534, p < 0.01).

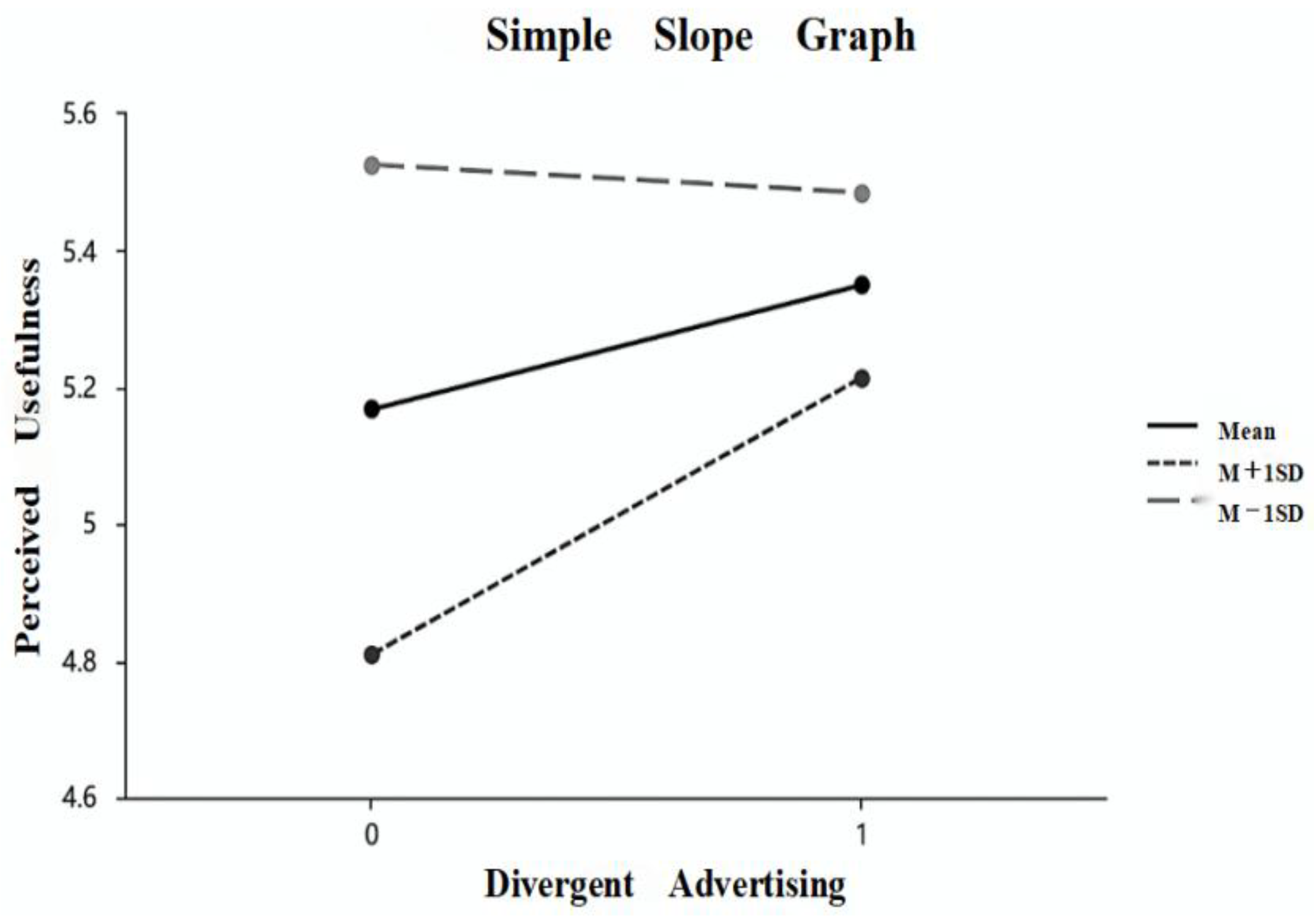

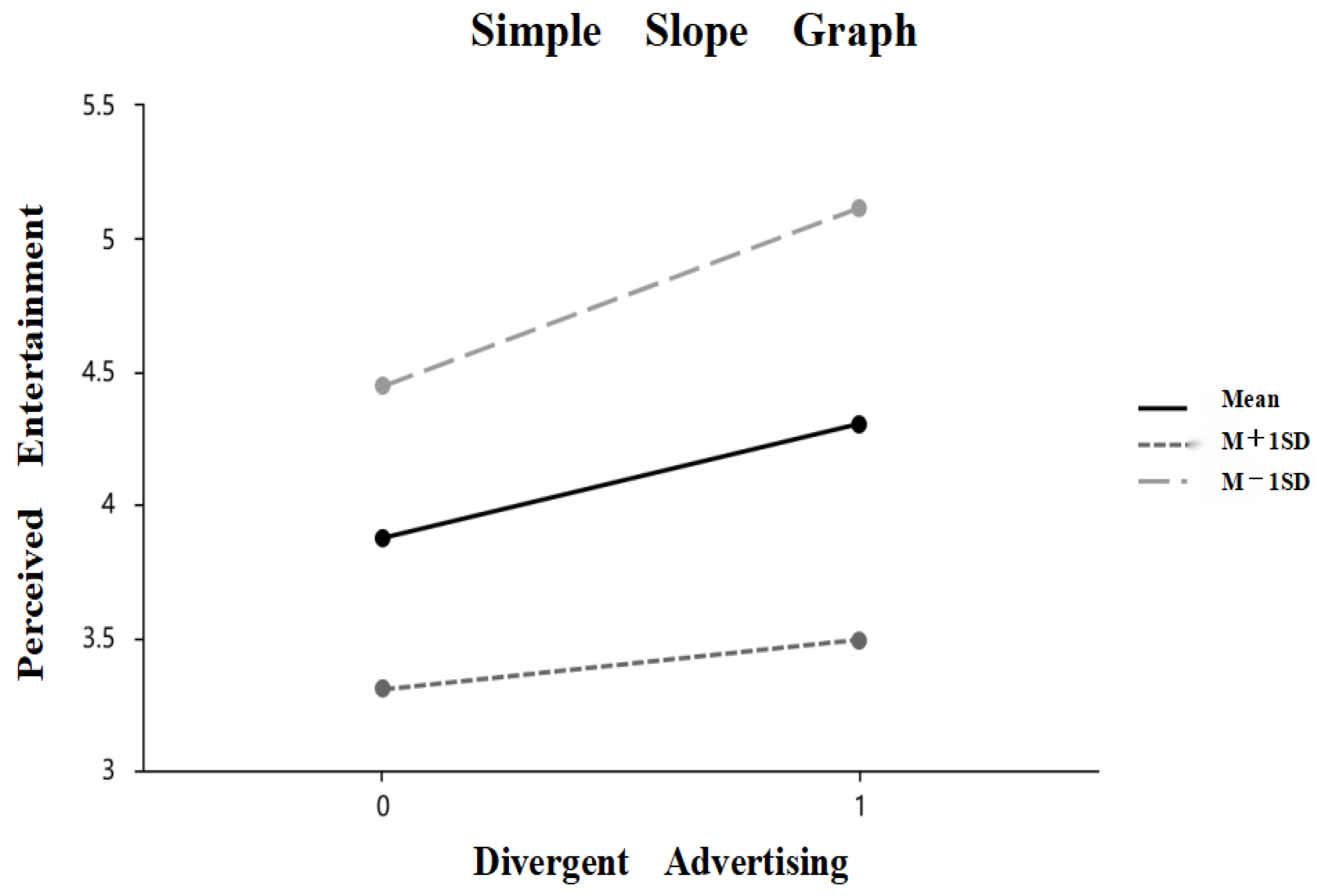

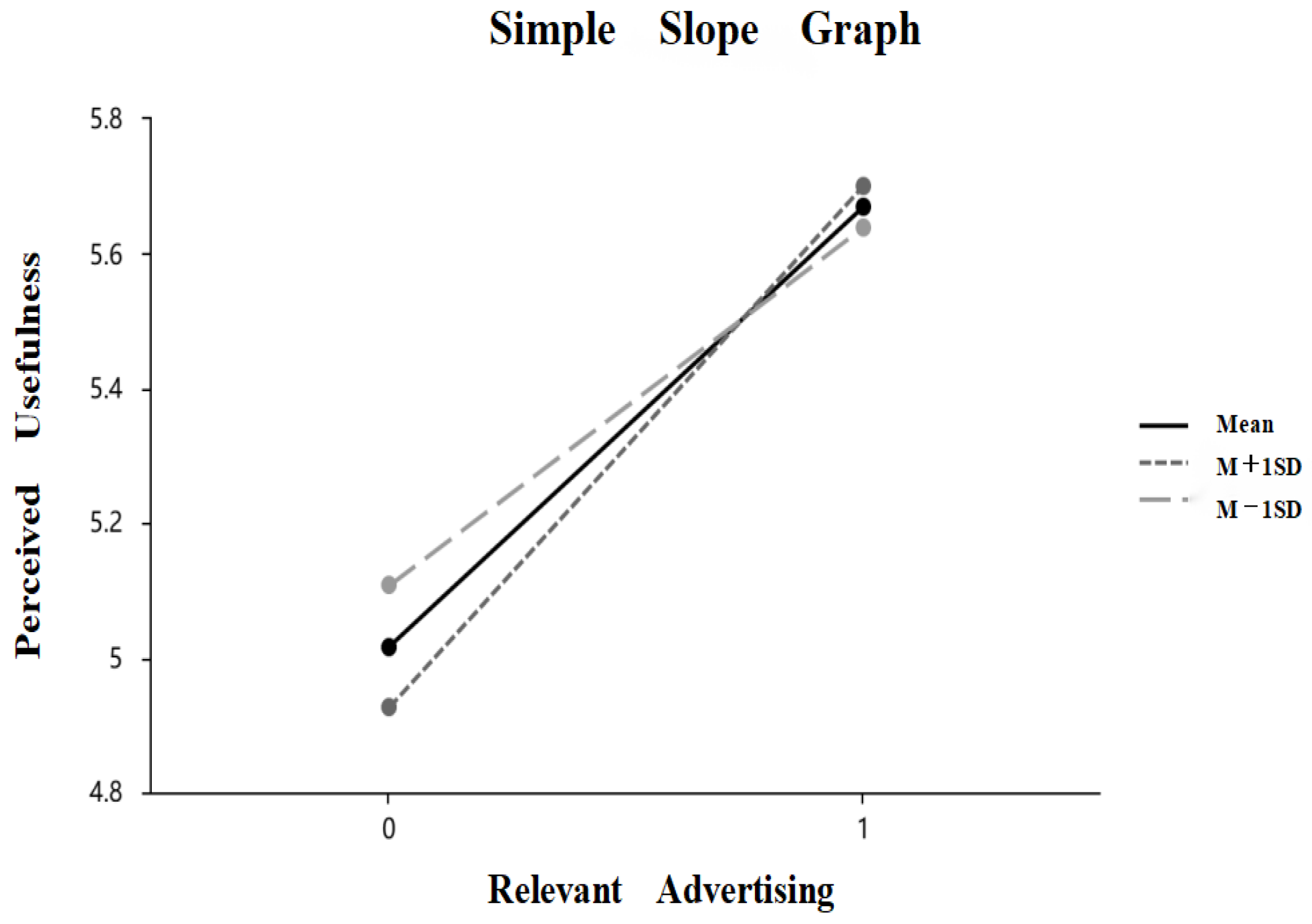

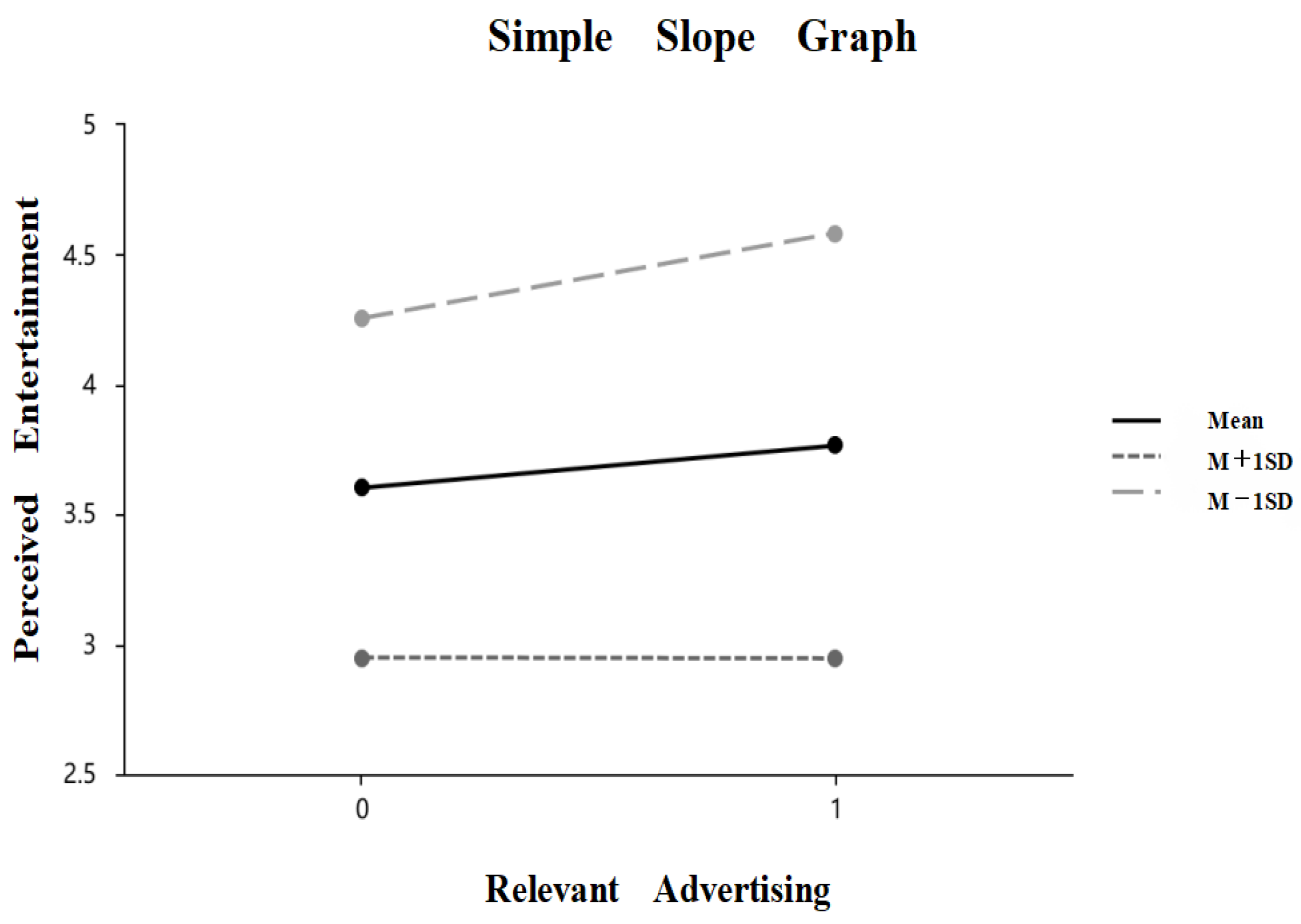

6.5.4. Moderating Effects Test

- 1.

- Divergent Advertising Moderating Effect Analysis

- 2.

- Relevant Advertising Moderating Effect Analysis

7. Discussion

7.1. Overall Conclusions and Hypothesis Summary

7.2. General Discussion

7.2.1. Theoretical Mechanism Interpretation: Validating and Extending the ELM in the AIGC Context

7.2.2. The Unique Attributes of AIGC Advertising and Consumer Response

7.2.3. Limitations and Boundary Conditions

7.3. Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implications

7.3.1. Theoretical Contributions

- 1.

- Integrating Objective Attention Metrics to Empirically Validate the ELM in AIGC Advertising.

- 2.

- Refining the Moderating Role of Product Involvement and Delineating its Boundary Conditions in AIGC Contexts.

- 3.

- Confirming the Dual-Value Nature of AIGC Advertisements and Providing Contextual Support for the Dual-Value Model.

7.3.2. Practical Implications

- 1.

- Providing Precise Guidance for AIGC Advertising Creativity and Content Generation

- 2.

- Refining Advertising Effect Measurement and Media Placement

- 3.

- Deepening Practical Insights for Personalized Marketing

7.4. Limitations and Future Research

- Sample Representativeness: Although the eye-tracking experiment achieved adequate statistical power, the participant pool was predominantly composed of university students. This reliance on a demographic characterized by higher technological receptivity but potentially lower independent purchasing power may limit the generalizability of findings to broader consumer populations with more diverse product involvement profiles. Future research should expand sampling strategies to include participants across different age groups and socioeconomic brackets to validate the moderating effects of product involvement and enhance the ecological validity of the findings.

- Advertising Modality Constraints: The current investigation focused exclusively on static AI-generated advertisements, neglecting increasingly prevalent dynamic formats such as video or interactive content. Given that dynamic advertising has been demonstrated to enhance attention capture and memory retention, the relationships observed between advertisement type and consumer outcomes in this study might differ in more immersive formats. Furthermore, creative elements were operationalized dichotomously (divergent versus relevant) rather than as continuous dimensions. Future research could employ multi-dimensional creativity scales to explore potential curvilinear effects and investigate how these relationships manifest in interactive advertisement formats.

- Methodological Boundaries: The laboratory controls implemented, while necessary for internal validity, introduced two primary constraints: reduced ecological validity compared to natural media consumption contexts and potential biases inherent in self-reported perceptual measures. To address these limitations, future research should consider

- (1)

- Integrating neuroimaging techniques (such as fNIRS or EEG) with eye-tracking to map the neural pathways connecting attention allocation and emotional processing;

- (2)

- Conducting field experiments that monitor advertisement engagement within authentic social media feeds using platform APIs;

- (3)

- Employing implicit measures (e.g., the Implicit Association Test) to assess unconscious biases toward AI-generated content.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIGC | Artificial Intelligence-Generated Content |

| ELM | Elaboration Likelihood Model |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| PU | Perceived Usefulness |

| PE | Perceived Entertainment |

| PI | Product Involvement |

| AOI | The Area of Interest |

| PUC | Professionally Generated Content |

| UGC | User-Generated Content |

Appendix A

Eye-Tracking Experiment on Dynamic AIGC Advertisements

- 1.

- Participants

- 2.

- Experimental Design

- 3.

- Stimuli Preparation

- 4.

- Apparatus and Procedure

- 5.

- Heatmap Analysis

References

- Rebelo, A.D.P.; Inês, G.D.O.; Damion, D.E.V. The impact of artificial intelligence on the creativity of videos. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2022, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishadi, G.P.K. AI-generated advertisements on consumer acceptance with the mediating effect of perceived intelligence in AI endorsement. Sri Lanka J. Manag. Stud. 2025, 7, 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, L.; Singaraju, S.P.; Niininen, O. Consumer responses to AI-generated charitable giving ads. J. Advert. 2023, 52, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, H.Z.; Hill, S.R.; Li, B.L. Consumer attitudes toward AI-generated ads: Appeal types, self-efficacy and AI’s social role. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 185, 114867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Niu, W.; Lin, C.-L.; Fu, S.; Liao, K.-T.; Zhang, W. Loss of control: AI-based decision-making induces negative company evaluation. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, K.; Till, B.D.; Carlson, B.D. Advertising creativity and repetition. Int. J. Advert. 2013, 32, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E.; Yang, X. Toward a general theory of creativity in advertising: Examining the role of divergence. Mark. Theory 2004, 4, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crano, W.D.; Prislin, R. Attitudes and persuasion. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2006, 57, 345–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Messinger, P.R.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Yang, S.; Li, G. Divergent versus relevant ads: How creative ads affect purchase intention for new products. J. Mark. Res. 2024, 61, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Li, X.; Xiang, Q. The infinite monkey theorem in AIGC advertising: Matching effects between AI disclosure and advertising appeals on consumer advertising avoidance intention. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonton, D.K. Creativity: Cognitive, personal, developmental, and social aspects. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducoffe, R.H. How consumers assess the value of advertising. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 1995, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armel, K.C.; Beaumel, A.; Rangel, A. Biasing simple choices by manipulating relative visual attention. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2008, 3, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Plangger, K.; Sands, S.; Kietzmann, J. Preparing for an era of deepfakes and AI-generated ads: A framework for understanding responses to manipulated advertising. J. Advert. 2022, 51, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, C.P.; Givi, J. The AI-authorship effect: Understanding authenticity, moral disgust, and consumer responses to AI-generated marketing communications. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 186, 114984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, J.; Rita, P.; Trigueiros, D. Attention, emotions, and cause-related marketing effectiveness. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 1728–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Attention and Effort; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E. Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, R.; Wedel, M.; Batra, R. The stopping rule in attention to advertising. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 29, 327–349. [Google Scholar]

- Behe, B.K.; Bae, M.; Huddleston, P.T.; Sage, L. The effect of involvement on visual attention and product choice. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 24, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Qiu, X.; Wang, Y. The impact of AI-personalized recommendations on clicking intentions: Evidence from Chinese e-commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ray, M.L. Affective responses mediating acceptance of advertising. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, R.B. Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 9, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Jia, S.; Lai, J.; Chen, R.; Chang, X. Exploring consumer acceptance of AI-generated advertisements: From the perspectives of perceived eeriness and perceived intelligence. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2218–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El, B.; Zou, J. Moloch’s Bargain: Emergent Misalignment When LLMs Compete for Audiences. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.06105. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass, R.B. Review of Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research, by M. Fishbein & I. Ajzen. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 10, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lange, P.A.; Kruglanski, A.W.; ToryHiggins, E.; Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 438–459. [Google Scholar]

- Pieters, R.; Wedel, M.; Zhang, J. Optimal feature advertising design under competitive clutter. Manag. Sci. 2007, 53, 1815–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Li, J. Research on driving factors of consumer purchase intention of artificial intelligence creative products based on user behavior. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Shao, X.; Li, X.T.; Guo, Y.; Nie, K. How live streaming influences purchase intentions in social commerce: An IT affordance perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 37, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.H.; Cheng, K.L.B. Does virtual reality attract visitors? The mediating effect of presence on consumer response in virtual reality tourism advertising. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseeh, H.I.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Pentecost, R.; Ashaduzzaman, M.; Arli, D.; Weaven, S. A meta-analytic review of mobile advertising research. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Ryoo, Y.; Choi, Y.K. That uncanny valley of mind: When anthropomorphic AI agents disrupt personalized advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2024, 43, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xie, P.; Dong, J.; Wang, T. Understanding programmatic creative: The role of AI. J. Advert. 2019, 48, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, S.; Husain, O.; Abdalla, E.A.M.; Ibrahim, A.O.; Hashim, A.H.A.; Elshafie, H.; Motwakel, A. Generative AI for Industry Transformation: A Systematic Review of ChatGPT’s Capabilities and Integration Challenges. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2025, 25, 221–249. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Cong, R. Artificial Intelligence Disclosure in Cause-Related Marketing: A Persuasion Knowledge Perspective. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Qiu, X. AI technology and online purchase intention: Structural equation model based on perceived value. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results. Ph.D. Thesis, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bimaruci, H.; Hudaya, A.; Ali, H. Model of consumer trust on travel agent online: Analysis of perceived usefulness and security on re-purchase interests (Case study: Tiket.com). Dinasti Int. J. Econ. Financ. Account. 2020, 1, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, A.L.; Piao, X.; Yu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Is AI chatbot recommendation convincing customer? An analytical response based on the elaboration likelihood model. Acta Psychol. 2024, 250, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, M.M.; Ho, S.C.; Liang, T.P. Consumer attitudes toward mobile advertising: An empirical study. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2004, 8, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.J. The influence of personalization in affecting consumer attitudes toward mobile advertising in China. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2006, 47, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Zheng, C.; Yin, J.; Teo, H.-H. AI-generated voice in short videos: A digital consumer engagement perspective. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Information Systems, Hyderabad, India, 10–13 December 2023; AIS Electronic Library (AISeL): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Matz, S.C.; Teeny, J.D.; Vaid, S.S.; Peters, H.; Harari, G.M.; Cerf, M. The potential of generative AI for personalized persuasion at scale. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, B.D.; Baack, D.W. Recall and persuasion: Does creative advertising matter? J. Advert. 2005, 34, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, J.R. Defining the necessary components of creative, effective ads. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. The personal involvement inventory: Reduction, revision, and application to advertising. J. Advert. 1994, 23, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Haley, E.; Koo, G.Y. Comparison of the paths from consumer involvement types to ad responses between corporate advertising and product advertising. J. Advert. 2009, 38, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.S.; Wang, J.Q.; Tu, S.H.; Liao, K.T.; Lin, C.L. Detecting latent topics and trends in IoT and e-commerce using BERTopic modeling. Internet Things 2025, 32, 101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.X.; Jin, Z.C. An eye-tracking study on the effect of involvement on processing rational appeal advertising. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2009, 41, 357–366. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.X.; Wen, X.S.; Wei, L.N.; Zhao, W.H. Advertising persuasion in China: Using Mandarin or Cantonese? J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2383–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, H.; Chen, L.N.; Feng, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Q. The effects of subtitle and product involvement on video advertising processing: Evidence from eye movements. J. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 43, 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.E. The double-edged sword of generative artificial intelligence in digitalization: An affordances and constraints perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 2924–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismajli, P. Generative AI in Digital Advertising: Exploring consumer attitudes regarding AI. Bus. Horiz. 2025, 63, 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- Molosavljevic, M.; Cerf, M. First attention then intention: Insights from computational neuroscience of vision. Int. J. Advert. 2008, 27, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozharliev, R.; Rossi, D.; De Angelis, M. A picture says more than a thousand words: Using consumer neuroscience to study Instagram users’ responses to influencer advertising. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.Y.; Sia, C.L.; Kuan, K.K.Y. Is this review believable? A study of factors affecting the credibility of online consumer reviews from an ELM perspective. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.C.; Xu, H.; Xu, C.; Zhang, H.; Ling, H. Privacy concerns for mobile app download: An elaboration likelihood model perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2017, 94, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, R.M.; Horton, R.S.; Vevea, J.L.; Citkowicz, M.; Lauber, E.A. A re-examination of the mere exposure effect: The influence of repeated exposure on recognition, familiarity, and liking. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 459–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.G.; Brandt, D.; Nairn, A. Brand relationships: Strengthened by emotion, weakened by attention. J. Advert. Res. 2006, 46, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, P. Attitudes and Persuasion, 1st ed.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, K. Anarchy of effects? Exploring attention to online advertising and multiple outcomes. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y. Effects of implicit memory on memory-based versus stimulus-based brand choice. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 34, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espigares-Jurado, F.; Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Correia, M.B.; Sousa, C.M.; Ramos, C.M.; Faísca, L. Visual attention to the main image of a hotel website based on its position, type of navigation and belonging to Millennial generation: An eye tracking study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Huo, J.L.; Jiang, Y.S. Can advertising creativity overcome banner blindness—Empirical analysis based on eye tracking technology. J. Mark. Sci. 2019, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.; Tinkham, S.; Edwards, S.M. The multidimensional structure of attitude toward the ad: Utilitarian, hedonic, and interestingness dimensions. In Proceedings of the American Academy of Advertising Conference, Hong Kong, China, 1–4 June 2005; American Academy of Advertising: Belleair Bluffs, FL, USA, 2005; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Jiang, Y.S.; Li, J.Z. The exposure effect of creative web-ads—Evidence from eye tracking. Chin. J. Manag. 2017, 14, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Yaveroglu, I.; Donthu, N. Advertising repetition and placement issues in online environments. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gironda, J.T.; Korgaonkar, P.K. iSpy? Tailored versus invasive ads and consumers’ perceptions of personalized advertising. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 29, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.E.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sinkovics, R.; Pezderka, N.; Haghirian, P. Determinants of consumer perceptions toward mobile advertising—A comparison between Japan and Austria. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Lin, J. What drives purchase intention for paid mobile apps? An expectation confirmation model with perceived value. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2015, 14, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheinin, D.A.; Varki, S.; Ashley, C. The differential effect of ad novelty and message usefulness on brand judgments. J. Advert. 2011, 40, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyanarayana, S.; Mohanasundaram, T. Fit indices in structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis: Reporting guidelines. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2024, 24, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.L.; Wu, Y.; Hou, J.T. Latent interaction in structural equation modeling: Distribution-analytic approaches. Psychol. Explor. 2013, 33, 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. Human-AI alignment in ad targeting: Addressing misestimation for vulnerable groups. J. Advert. 2025, 54, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zeng, Z.; Cheng, K. Navigating the Intrusiveness Paradox: A Comprehensive Literature Review on AI Marketing and Consumer Perception. Adv. Consum. Res. 2024, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Castelo, N.; Bos, M.W.; Lehmann, D.R. Task-dependent algorithm aversion. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Lü, K.; Fang, W. Machines vs. humans: The evolving role of artificial intelligence in livestreaming e-commerce. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 188, 115077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Hypothesis | Core Theory | Independent Variable | Dependent/Mediating/Moderating Variable |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Attention Allocation Theory [17] | AIGC Ad Type (Relevant vs. Divergent) | Dependent: Product Attention |

| H2 | Attention Allocation Theory [17] | AIGC Ad Type (Relevant vs. Divergent) | Dependent: Non-product Attention |

| H3 | ELM (Central Route) [18] | AIGC Ad Type (Relevant) | Dependent: Purchase Intention |

| H4 | ELM (Peripheral Route) [18] | AIGC Ad Type (Divergent) | Dependent: Ad Attitude |

| H5 | ELM + TAM [18,39] | AIGC Ad Type (Relevant/Divergent) | Mediator: Perceived Usefulness (PU) |

| H6 | ELM + Hedonic Processing Theory [18,22] | AIGC Ad Type (Relevant/Divergent) | Mediator: Perceived Entertainment (PE) |

| H7 | ELM + PI Theory [18,48] | AIGC Ad Type × PI | Moderator: Product Involvement (PI) |

| Research Hypothesis | Primary Study for Verification | Data/Method Employed |

|---|---|---|

| H1: Relevant AI ads → Product attention | Eye-tracking Experiment 1 (Single-type Group) | AOI metrics (Fixation time, count, ratio) |

| H2: Divergent AI ads → Non-product attention | Eye-tracking Experiment 1 (Single-type Group) | AOI metrics (Fixation time, count, ratio) & Heatmaps |

| H1 & H2 (Robustness Check) | Eye-tracking Experiment 2 (Mixed Group) | Comparative analysis of AOI metrics vs. Single-type groups |

| H3: Relevant AI ads → Purchase intention | Empirical Study (Questionnaire) | Structural Equation Modeling (Path Analysis) |

| H4: Divergent AI ads → Advertising attitude | Empirical Study (Questionnaire) | Structural Equation Modeling (Path Analysis) |

| H5: Mediating role of Perceived Usefulness (PU) | Empirical Study (Questionnaire) | Bootstrap Mediation Test |

| H6: Mediating role of Perceived Entertainment (PE) | Empirical Study (Questionnaire) | Bootstrap Mediation Test |

| H7: Moderating role of Product Involvement (PI) | Empirical Study (Questionnaire) | Hierarchical Regression Analysis |

| Mixed Ad Group (M ± SD) | Divergent Ad Group (M ± SD) | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOI fixation time (s) | 1.06 ± 0.35 | 1.21 ± 0.31 | 0.62 | 0.56 |

| AOI fixation time ratio (%) | 14.96 ± 7.04 | 15.64 ± 5.38 | 0.16 | 0.88 |

| AOI fixation count (n) | 3.15 ± 2.57 | 3.83 ± 1.39 | 0.46 | 0.66 |

| Mixed Ad Group (M ± SD) | Relevant Ad Group (M ± SD) | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOI fixation time (s) | 2.43 ± 0.59 | 2.36 ± 0.37 | −0.19 | 0.85 |

| AOI fixation time ratio (%) | 41.43 ± 12.37 | 30.26 ± 4.56 | −1.70 | 0.14 |

| AOI fixation count (n) | 5.25 ± 3.30 | 7.25 ± 0.96 | 1.16 | 0.32 |

| Variable | Measurement Items | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Divergence | 1. The ad was “out of the ordinary.” | Jiang et al. [9] |

| 2. The ad broke away from habit-bound and stereotypical thinking. | ||

| 3. The ad contained ideas that moved from one subject to another. | ||

| 4. The ad connected objects that are usually unrelated. | ||

| 5. The ad brought unusual items together. | ||

| 6. The ad contained more details than expected. | ||

| 7. The ad was visually/verbally distinctive. | ||

| Relevance | 1. The ad contained elements that are strongly related. | |

| 2. I think the ad was relevant to me. | ||

| 3. The ad was very meaningful to me. | ||

| Perceived usefulness | 1. I think this ad is valuable. | Gironda & Korgaonkar [70] |

| 2. The ad helps me to reach more useful information. | ||

| 3. The ad is helpful for my future purchase decisions. | ||

| Perceived Entertainment | 1. I find the ad very interesting. | Ducoffe [12] |

| 2. I think I enjoyed the ad. | Lee et al. [71] | |

| 3. I find the ad to be enjoyable. | Liu et al. [72] | |

| Purchase intention | 1. I find purchasing product advertised to be worthwhile. | Hsu & Lin [73] |

| 2. I will strongly recommend others to purchase product advertised. | ||

| 3. I would like to have the advertised products. | ||

| Advertising attitude | 1. I enjoy the ad. | Sheinin et al. [74] |

| 2. I like the ad. | ||

| 3. I find this ad very appealing. | ||

| 4. I think the content of this ad is very original and creative. | ||

| 5. I will recommend this ad to others. |

| Factor | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained (%) | Cumulative Variance Explained (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11.12 | 37.08 | 37.08 |

| 2 | 5.27 | 17.56 | 54.64 |

| 3 | 2.84 | 9.46 | 64.10 |

| 4 | 1.60 | 5.35 | 69.45 |

| 5 | 1.37 | 4.57 | 74.01 |

| Divergence | Relevance | Perceived Usefulness | Perceived Entertainment | Purchase Intention | Advertising Attitude | Product Involvement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divergence | 0.926 | ||||||

| Relevance | 0.105 ** | 0.888 | |||||

| Perceived usefulness | 0.215 ** | 0.677 ** | 0.894 | ||||

| Perceived entertainment | 0.484 ** | 0.212 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.913 | |||

| Purchase intention | 0.189 ** | 0.594 ** | 0.639 ** | 0.219 ** | 0.821 | ||

| Advertising attitude | 0.627 ** | 0.149 ** | 0.200 ** | 0.680 ** | 0.317 ** | 0.904 | |

| Product involvement | −0.158 ** | −0.279 ** | −0.255 ** | −0.409 ** | −0.351 ** | −0.372 ** | 0.630 |

| Construct | Item | Item Reliability | Convergence Reliability | Composite Reliability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std. | SMC | AVE | CR | ||

| Divergent Advertising | DA1 | 0.922 | 0.851 | 0.857 | 0.977 |

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | DA2 | 0.949 | 0.901 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | DA3 | 0.918 | 0.843 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | DA4 | 0.926 | 0.858 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | DA5 | 0.927 | 0.859 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | DA6 | 0.918 | 0.842 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | DA7 | 0.921 | 0.848 | ||

| Relevant Advertising | RA1 | 0.857 | 0.734 | 0.789 | 0.918 |

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | RA2 | 0.897 | 0.804 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | RA3 | 0.911 | 0.829 | ||

| Perceived Usefulness | PU1 | 0.891 | 0.795 | 0.799 | 0.923 |

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | PU2 | 0.894 | 0.799 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | PU3 | 0.896 | 0.803 | ||

| Perceived Entertainment | PE1 | 0.898 | 0.806 | 0.833 | 0.937 |

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | PE2 | 0.929 | 0.864 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | PE3 | 0.91 | 0.828 | ||

| Purchase Intention | PUI1 | 0.816 | 0.666 | 0.673 | 0.861 |

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | PUI2 | 0.803 | 0.645 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | PUI3 | 0.842 | 0.709 | ||

| Advertising Attitude | AA1 | 0.898 | 0.806 | 0.818 | 0.957 |

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | AA2 | 0.909 | 0.825 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | AA3 | 0.908 | 0.824 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | AA4 | 0.900 | 0.810 | ||

| Divergence Relevance Perceived usefulness Perceived entertainment Purchase intention Advertising attitude Product involvement | AA5 | 0.908 | 0.825 | ||

| Product Involvement | PI1 | 0.579 | 0.335 | 0.396 | 0.766 |

| PI2 | 0.606 | 0.367 | |||

| PI3 | 0.614 | 0.377 | |||

| PI4 | 0.688 | 0.473 | |||

| PI5 | 0.655 | 0.429 | |||

| Number | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 114 | 49.60 |

| Female | 116 | 50.40 | |

| Age group | Under 18 years old | 32 | 13.90 |

| 18–23 years old | 76 | 33.00 | |

| 24−29 years old | 43 | 18.70 | |

| 30−35 years old | 38 | 16.50 | |

| 36−41 years old | 15 | 6.50 | |

| 42–47 years old | 16 | 7.00 | |

| 48 years old and above | 10 | 4.30 | |

| Occupation | Student | 74 | 32.20 |

| Employees of Enterprises and Public Institutions | 12 | 5.20 | |

| Teacher | 10 | 4.30 | |

| Freelancer | 24 | 10.40 | |

| Farmer | 23 | 10.00 | |

| Corporate Employee | 69 | 30.00 | |

| Corporate Executive | 7 | 3.00 | |

| Self-employed Businessperson | 11 | 4.80 | |

| Monthly income range | No income | 79 | 34.30 |

| Less than 3000 yuan | 33 | 14.30 | |

| 3001–4500 yuan | 17 | 7.40 | |

| 4501–6000 yuan | 18 | 7.80 | |

| 6001–7500 yuan | 21 | 9.10 | |

| 7501–9000 yuan | 26 | 11.30 | |

| 9001–10,500 yuan | 15 | 6.50 | |

| 10,501–12,000 yuan | 8 | 3.50 | |

| 12,000 yuan and above | 13 | 5.70 |

| Path Relationship | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU <--- RA | 0.665 | 0.022 | 30.953 | *** |

| PE <--- RA | 0.208 | 0.02 | 10.25 | *** |

| PU <--- DA | 0.125 | 0.017 | 6.901 | *** |

| PE <--- DA | 0.458 | 0.018 | 23.28 | *** |

| PU <--- PI | −0.061 | 0.022 | −3.303 | *** |

| PE <--- PI | −0.313 | 0.023 | −16.189 | *** |

| PUI <--- PU | 0.509 | 0.024 | 15.655 | *** |

| AA <--- PE | 0.523 | 0.02 | 25.542 | *** |

| PUI <--- RA | 0.294 | 0.024 | 9.277 | *** |

| AA <--- DA | 0.385 | 0.017 | 20.056 | *** |

| PU <--- DA*PI | 0.076 | 0.014 | 3.815 | *** |

| PE <--- DA*PI | −0.25 | 0.014 | −11.946 | *** |

| PU <--- RA*PI | 0.089 | 0.015 | 4.311 | *** |

| PE <--- RA*PI | −0.167 | 0.015 | −7.821 | *** |

| Variable | Perceived Usefulness | Perceived Entertainment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Constant | 5.228 ** | 5.223 ** | 5.168 ** | 3.824 ** | 3.815 ** | 3.875 ** |

| Gender | −0.138 | −0.129 | −0.102 | −0.152 * | −0.138 * | −0.168 ** |

| Age groups | −0.058 * | −0.066 ** | −0.050 * | 0.048 * | 0.035 | 0.019 |

| Occupation | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.007 | −0.003 | 0.000 | −0.004 |

| Monthly income range | −0.013 | −0.011 | −0.008 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.002 |

| Divergent advertising | 0.216 ** | 0.182 ** | 0.182 ** | 0.484 ** | 0.431 ** | 0.430 ** |

| Product involvement | −0.278 ** | −0.276 ** | −0.436 ** | −0.439 ** | ||

| Divergent advertising * Product involvement | 0.172 ** | −0.187 ** | ||||

| VIF | 1.044 | 1.045 | 1.002 | 1.044 | 1.045 | 1.002 |

| R2 | 0.052 | 0.102 | 0.165 | 0.238 | 0.35 | 0.418 |

| F | 20.007 | 34.764 | 51.739 | 114.269 | 164.484 | 187.464 |

| Variable | Perceived Usefulness | Perceived Entertainment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 | |

| Constant | 4.974 ** | 4.982 ** | 5.016 ** | 3.610 ** | 3.650 ** | 3.603 ** |

| Gender | −0.111 * | −0.108 * | −0.105 | −0.192 * | −0.178 * | −0.183 ** |

| Age groups | −0.014 | −0.018 | −0.01 | 0.117 ** | 0.093 ** | 0.083 ** |

| Occupation | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.019 | 0.021 | 0.020 | 0.023 |

| Monthly income range | −0.014 | −0.013 | −0.014 | −0.008 | −0.003 | −0.002 |

| Relevant advertising | 0.706 ** | 0.685 ** | 0.654 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.119 ** | 0.162 ** |

| Product involvement | −0.088 ** | −0.070 ** | −0.479 ** | −0.503 ** | ||

| Relevant advertising * Product involvement | 0.094 ** | −0.128 ** | ||||

| VIF | 1.088 | 1.123 | 1.103 | 1.088 | 1.123 | 1.103 |

| R2 | 0.462 | 0.467 | 0.484 | 0.064 | 0.192 | 0.221 |

| F | 314.486 | 266.982 | 245.009 | 25.104 | 72.433 | 74.057 |

| Hypothesis | Statement | Verification Result |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Relevant AI advertisements significantly enhance consumers’ product attention compared to divergent AI advertisements. | Supported |

| H2 | Divergent AI advertisements significantly enhance consumers’ non-product attention compared to relevant AI advertisements. | Supported |

| H3 | Relevant AI advertisements significantly enhance consumers’ purchase intention. | Supported |

| H4 | Divergent AI advertisements significantly enhance consumers’ advertising attitudes. | Supported |

| H5 | Perceived usefulness (PU) mediates the effect of AI ad types on purchase intention. | Supported (The specific partial/full mediation pattern as theorized was confirmed). |

| H6 | Perceived entertainment (PE) mediates the effect of AI ad types on advertising attitude. | Supported (The specific partial/full mediation pattern as theorized was confirmed). |

| H7 | Product involvement (PI) moderates the relationships between AI ad types and perceived values (PU & PE). | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, S.; Zheng, W.; Kong, H. Trust or Skepticism? Unraveling the Communication Mechanisms of AIGC Advertisements on Consumer Responses. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040339

Jiang S, Zheng W, Kong H. Trust or Skepticism? Unraveling the Communication Mechanisms of AIGC Advertisements on Consumer Responses. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(4):339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040339

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Shoufen, Wanqing Zheng, and Haiyan Kong. 2025. "Trust or Skepticism? Unraveling the Communication Mechanisms of AIGC Advertisements on Consumer Responses" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 4: 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040339

APA StyleJiang, S., Zheng, W., & Kong, H. (2025). Trust or Skepticism? Unraveling the Communication Mechanisms of AIGC Advertisements on Consumer Responses. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(4), 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040339