Simple Summary

Hair is a useful and minimally invasive biological sample for evaluating cortisol and long-term stress in cattle. In this study, hair cortisol concentration (HCC) was measured in different dairy cow breeds with various coat colors during a hot summer in Tunisia. The results showed that cows with darker hair, particularly black, had significantly higher HCC than those with lighter hair (p < 0.05). Our finding demonstrates the association between darker hair pigmentation and significantly higher measured cortisol concentrations. These results underscore the necessity to consider pigmentation when using hair cortisol concentration to assess stress.

Abstract

Background: Cortisol is known as the main hormone released during stress responses in cattle and has been used to assess various stressors, including heat stress. This study investigated hair cortisol concentration (HCC) in different hair coat colors in dairy cows under natural heat stress conditions (temperature humidity index = 75). Methods: Hair samples were collected from the forehead region of ten multiparous cows (Brown Swiss, Montbéliarde, and Holstein) per group color at both the beginning and end of a three-week peak summer period in 2024 in the region of Jendouba, North Tunisia. Cows were grouped according to hair coat color (black, brown, red, white, and yellow) for subsequent analysis. Hair samples were prepared using a methanol-based separation protocol and analyzed via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Results: Meteorological data confirmed that cows were sustained under heat stress, with an average temperature humidity index value of 75; results indicated that black hair had considerably more HCC than white hair (p < 0.05). The results showed that there is a significant difference between HCC under three clusters (p < 0.05) according to hair color. Conclusions: The study emphasizes that hair color, along with factors such as breed and environmental conditions, should be carefully considered when using HCC to assess stress in cattle beyond simply black or white hair color.

1. Introduction

Heat stress represents one of the most significant environmental stressors in dairy production for animal health, productivity, and welfare [1]. When ambient temperatures (AT˚C) exceed the thermoneutral zone of dairy cows (typically above 25 °C with high humidity), they experience hyperthermia, leading to physiological and metabolic disruptions [2]. Oxidative stress is increased by prolonged heat stress and systemic inflammation, predisposing cows to metabolic problems such as ketosis and mastitis [3]. Heat stress presents significant challenges and economic losses to dairy production in developing countries and regions like North Africa and Tunisia, where indigenous and cross-bred cattle face severe thermal stress [4].

Along with a lack of energy required for development and milk production [5], excessive uninterrupted heat in the body can result in worse living conditions, a lower quality of life, and, in the worst situations, mortality [6].

Cortisol, the primary glucocorticoid in cattle, is a key endocrine marker of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activation [7]. Integrated glucocorticoid exposure may be reflected in hair cortisol over the hair growth period and may be applicable for assessing both acute and prolonged stress responses [8]. The hair sample is painless to collect and more stable than the conventional matrices at room temperature [9]. Although Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) provides more accuracy and is the gold standard for conclusive molecular information, the ELISA method was selected based on field feasibility and a superior cost-effectiveness/high-throughput trade-off [10]. Prior research has produced conflicting results relating to how cortisol is incorporated into hair of different colors [9,11]. Hair cortisol represents a combined signal from circulating glucocorticoids incorporated during hair growth and possibly local follicular production. It was outside the focus of this study to distinguish these sources, but both contribute to measured cortisol mass [12]. As highlighted by Heimbürge et al. [9], the mechanisms underlying cortisol deposition in differently pigmented hair remain unclear and require further investigation.

To fill this gap, the current study focuses on the influence of hair color on cortisol concentrations in dairy cows exposed to natural heat stress. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to examine the concentrations of cortisol in the hair of cows with different pigmentation under conditions of natural heat stress. Ultimately, these findings will help to improve the interpretation of hair cortisol as a stress biomarker and support its practical application as a herd-level welfare monitoring tool under heat stress conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

The research was conducted in North Tunisia, in the region of Jendouba (36° 34′ 26″ N, 8° 47′ 50″ E), during three weeks of the summer season, from mid-July to August 2024. A total of 50 multiparous dairy cows were selected and assigned to five groups based on hair color: Black, Brown, Yellow, White, and Red (n = 10 per group). The groups were assigned according to hair color. Hair color was recorded based on photographic documentation and confirmed by two independent observers. Three dairy breeds were included: Holstein, Brown Swiss, and Montbéliarde (Table 1).

Table 1.

Averages and standard deviations of the characteristics of hair color groups.

All cows were clinically healthy and at mid-lactation, with no recent history of illness, veterinary treatments, or reproductive interventions. Cows were excluded if they had a somatic cell count surpassing 200,000 cells/mL or were within two weeks postpartum. For the duration of the trial, they were kept in the same free-stall barn and given free access to water.

Cows were fed a total mixed ration prepared following the NRC [13] regulations to meet their maintenance and milk production requirements. Milking was performed twice daily at 02:00 and 14:00 h using a herringbone milking machine.

2.2. Meteorological Data

Daily measurements of AT (°C) and relative humidity (RH%) were collected for 24 h inside the barn to accurately represent the environmental exposure of animals. For the purposes of this measurement, a digital data logger (Model AZ 88162, AZ Instrument Corp., Taichung City, Taiwan) was installed on the farm inside the barn, with registration at intervals of 5 min. The sensor type AT°C was “NTC thermistor, 833ET-1S87P-70370, Semitec Corporation, Tokyo, JP”, measuring range: −30 °C to 70 °C, +/−0.5 °C accuracy. For the RH%, the sensor type was “Capacitive humidity sensor, CS10-195”, Campbell Scientific, Inc., Logan, UT, USA range of measurement: 0.1~99.9%, RH precision: +/−3%, RH (at 25 °C, 10–90% RH range), and additional +/−5%. The data logger for the inside measurements was placed in a representative position of the studied site near the living area of animals, 1.6 m high. The temperature humidity index (THI) [14] is a combination of AT°C and RH%, calculated according to the following formula:

THI = 1.8 × AT − (AT − 14.3) × (100 − RH) ∕ 100 + 32

2.3. Hair Samples Collection and Preparation

Hair sampling was performed from the forehead for each cow selected because it is consistently exposed, has a lower risk of contamination, is easy to collect repeatedly from the same site, and has been commonly used in previous cattle studies for cortisol measurement [15].

Hair samples collected at the start and end of the experimental period were analyzed separately to avoid confounding the effects of environmental exposure during hair growth. Hair was cut carefully (>1 g) from the cow’s forehead about 10 to 20 cm, as near to the skin as feasible. The hair samples were then promptly wrapped with sheets of aluminum foil, numbered, and kept in a plastic bag at 4 °C for the subsequent processes, which included washing, drying, steroidal separation, and ELISA analysis. All samples were collected by a single trained technician to minimize variability.

Hair cortisol separation was performed in accordance with Davenport et al. [16] and Ghassemi Nejad et al. [17]. An amount of 250 mg was weighed from every sample with a digital scale. The hair samples were then put into 15 mL conical polypropylene tubes. Then 5 mL of propanol was added to each tube. The tubes were then vortexed gently for 3 min to remove non-incorporated external cortisol and other surface-bound contaminants, followed by drying. This procedure was repeated twice, followed by drying hair samples for 7 days at room temperature under the hoof. Drying was necessary to remove residual moisture. After that, a portion of 50 mg of hair samples was chopped with scissors into pieces of 1 mm and homogenized into 2 mL tubes using six stainless steel balls and pulverized for 8 min at 50 Hz. Then, a volume of 1 mL of methanol was added. Afterwards, samples were put on a tube rotator in gentle rotation (0.026× g) for a full day at ambient temperature in order to separate cortisol. Later, specimens were centrifuged at 14,296× g for 60 s. Then, a volume of 0.6 mL of supernatant was shifted into a clean microcentrifuge tube (1.5 mL) and incubated at 38 °C until the evaporation of the methanol.

2.4. Hair Cortisol Analysis

The HCC was measured in duplicate using a commercially available bovine cortisol ELISA kit (Catalog Num.: MBS7606296, MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA) with intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (8% and 10%) and recovery rate (97%). The ELISA kit was taken out of the freezer about twenty minutes before and equilibrated to room temperature (18–25 °C). Then, the standard, samples, and control wells were set on the pre-coated plate, respectively, recording their points. Later, the plate was washed 2 times prior to adding the standard, sample, and control wells. In addition, 50 µL of zero tube, 1st tube, 2nd tube, 3rd tube, and 4th tube was aliquoted into each standard well. A volume of 50 µL buffer for dilution of samples was added to the control well. Then, 50 µL pilot samples were added to every sample well. In addition, a volume of 50 µL of biotin-labeled Antibody Working Solution was introduced into every well immediately. Move the plate slightly for 1 min to guarantee complete mixing. After that, statically incubate for 45 min at 37 °C. Moreover, the liquid in the plate was absorbed by repeatedly tapping the plate on a fresh piece of absorbent paper. A volume of 350 µL of wash buffer was added to each well, and the liquid in the well was discarded. The washing step was repeated three times. Next, a volume of 100 µL of SABC working solution was transferred into every well. The plate was covered and kept for 30 min at 37 °C. After that, a wash procedure for five times was required by removing the cover and then washing the plate with the wash buffer. An aliquot of 90 µL of TMB substrate was introduced to every well, then the plate was sealed and stably incubated at 37 °C for 10–20 min in the dark. After that, the microplate reader was turned on and preheated for 15 min. The liquid in the well was kept after staining, and an amount of 50 µL stop solution was introduced into every well. The color changed to yellow instantly. Finally, the optical density (OD) absorbance was determined at 450 nm in a microplate reader (Tecan Trading AG, Mannedorf, Switzerland) immediately. After that, the results were treated by calculating the mean OD 450 value, plotting the mean absorbance for each standard on the y-axis across the concentration on the x-axis, and calculating the sample concentration.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To examine the effect of hair color on cortisol concentration, SAS® software (version 9.4, SAS® Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to conduct statistical analyses. Hair samples were categorized into five color groups (black, brown, yellow, white, and red). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to compare mean cortisol concentrations across hair color groups. Mean and standard deviations were reported, and the GLM procedure was used for the analysis. The statistical model contained the effects of hair color and the residual error and was expressed as yij =μ + ci + eij, where y is the variable of interest, μ is the general mean, c is the influence of hair color, and e is the residual error. For mean separation when a significant difference was present, least significant difference (LSD) comparison procedures were applied. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Additionally, to explore patterns in HCC across different hair colors, an analysis of hierarchical clusters was carried out, applying Ward’s minimum variance approach with Euclidean distance as a metric for dissimilarity for minimizing intra-cluster variance.

3. Results

3.1. Meteorological Data Collection

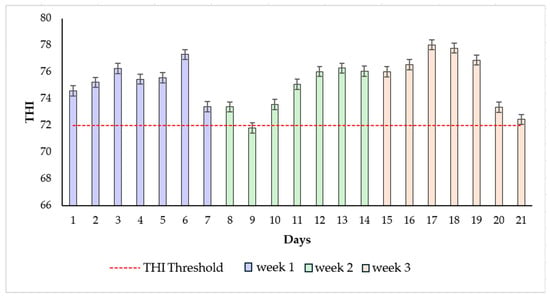

The average AT and RH for the first, second, and third weeks of the experiment were 27.52 °C, 29.12%; 31.13 °C, 31.77%; and 32.13 °C, 30.35%, respectively. Figure 1 shows the average THI values for each week of the trial. The average THI was 72.04 ± 0.66, 75.68 ± 0.85, and 76.71 ± 0.24 for weeks 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Figure 1.

Temperature humidity index (THI) values during the experimental period, the mean values of THI, and the error bars were presented during the three weeks of the experiment in 2024.

3.2. Variation in Hair Cortisol in Relation to Hair Color

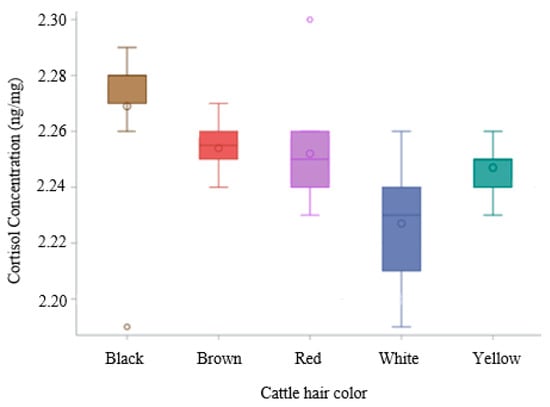

The white coats have the lowest average HCC, contrary to the black color coat, which presents the highest average HCC (p < 0.05), Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Boxplot of hair cortisol concentration across different hair colors.

Utilizing a post hoc Tukey HSD test to account for multiple comparisons, the Least Squares Means (LSMs) for the factor color were analyzed. A significant difference (p < 0.05) was observed between black (LSM = 2.269 ng/mg) and white (LSM = 2.229 ng/mg) color (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pairwise comparisons (Tukey’s HSD test) of hair cortisol least-squares means (ng/mg).

These findings indicate that the mean response associated with the black color is significantly different from that of the white color. Conversely, brown (LSM = 2.254 ng/mg), red (LSM = 2.252 ng/mg), and yellow (LSM = 2.247 ng/mg) (Table S1) did not exhibit statistically significant differences among themselves. The HCC in the white coat was significantly lower than in the brown, yellow, and red coats. However, the HCC in the black coat was significantly higher than in the brown, yellow, and red coats.

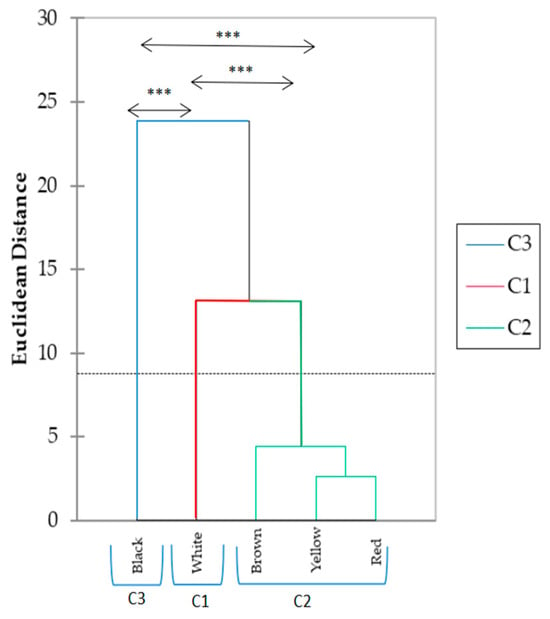

The results presented by the hierarchical clustering in Figure 3 showed that black represents the highest mean effect, white the lowest, and the remaining colors (brown, red, and yellow) form intermediate HCC.

Figure 3.

Classification of hair cortisol concentration by hair color clusters of heat-stressed dairy cows. *** p < 0.05 between hair color clusters. Cluster 1 (C1) color: white; Cluster 2 (C2) color: brown, yellow, and red; Cluster 3 (C3) color: black. The horizontal dotted line across the dissimilarity threshold used to define the final three clusters (C1, C2, and C3).

The dendrogram groups five color categories, including black, white, brown, yellow, and red, based on their dissimilarities. Three primary clusters were identified: Cluster 3 (C3) includes black color, which shows the highest dissimilarity from the other colors; Cluster 2 (C2) groups yellow and red, indicating high similarity between these two; and Cluster 1 (C1) encompasses white color. The dotted horizontal line indicates a threshold for comparing the dissimilarity levels. These results illustrate distinct groupings based on the dissimilarity analysis, providing insight into the relative differences between the categories and clusters.

4. Discussion

During the experiment, the meteorological data indicated that cows were exposed to heat stress conditions, with the THI consistently exceeding the threshold value of 72. This level is considered critical for dairy cattle, as it marks the point where thermal discomfort begins to impair physiological and productive functions [1,18,19].

To date, there are difficulties in establishing a universal, context-specific stress threshold for hair cortisol concentration in cattle. Comin et al. [20] discovered a concentration of hair cortisol released in response to a switch from confined winter grazing to outdoor grazing conditions in dairy cows of 2.1 ± 0.10 and 2.9 ± 0.17 pg/mg, respectively. Talló-Parra et al. [21] stipulated that white hair samples (pg/mg) contain less cortisol from day 0 to day 25 of the experiment (2.1 ± 1.10 to 1.4 ± 0.73) than black hair (3.9 ± 1.44; 2.5 ± 1.61). These results are in accordance with our findings, in which HCC was lower in white than black hair (p < 0.05). Otten et al. [22] confirm our findings, demonstrating that samples of black hair have higher cortisol concentrations than samples of light hair (p < 0.05). This is in line with findings from prior research on both humans and cattle showing that dark or black hair shows increased HCC [21,23].

Contrary to these findings, Gonzalez-de-la-Vara et al. [24] stipulated that concentrations were greater in white hair as opposed to black hair. In a search carried out by Burnett et al. [25], HCC was higher in white than in black hair (7.8 ± 1.1 vs. 3.8 ± 1.1 pg/mg). The results found by Nedić et al. [26] in Holstein cows indicate no significant difference was found between concentrations in black and white hair. The contradictory findings concerning HCC in white versus black hair, particularly the results of González-de-la-Vara et al. [24] and Burnett et al. [25], which reported higher concentrations in white hair versus our findings and those of Talló-Parra et al. [21], are likely attributable to methodological differences and breed-specific factors. A primary methodological consideration is the analytical technique used; differences in assay type (radioimmunoassay [RIA] vs. [LC MS/MS]), separation solvent, and protocol for washing the hair can significantly impact the measured HCC. In fact, hair is either ground into powder or cut with scissors into tiny pieces (1 mm) after cleaning. In cattle, ground hair had greater concentrations than fragmented hair [25]. A pestle and mortar can be used to grind hair in liquid nitrogen [27] or a ball mill [26]. Such a method was conducted in our case. Typically, methanol is utilized as a solvent to separate cortisol. It results in solubilization, dispersion of cortisol, and swelling of the hair. Hair extract is reconstituted into a suitable medium [28], such as PBS buffer [27], following solvent evaporation. Analysis of cortisol levels can be performed by RIA, chemiluminescent immunoassays, HPLC-mass spectrometry, HPLC with fluorescence detection, and enzyme immunoassay (EIA) [28]. Using validation testing, RIA has been utilized to analyze cortisol in dairy cows [20,24]. EIA has been fully validated in beef cattle [29]. Additionally, it has been proven that EIA may detect HCC in dairy cattle with acceptable repeatability and reliability [21]. Vesel and Pavić’s study [27] indicated that ELISA was an excellent method for detecting hair cortisol in dairy cows. Other research on cattle, however, has revealed inconsistent findings [24,25,30] or no effects [26,31]. Therefore, the conflicting results regarding cortisol concentrations in light and dark hair remain unclear and may be attributed to interactions with melanin, elevated blood circulation to the skin coated by black hair, and the interior space within the hair follicle [32].

Thus far, the contradictory results regarding cortisol concentrations in both light and dark hair have yet to be completely proven but might be connected to melanin interactions or increased UV-induced washout in darker hair [25,33,34,35,36]. Otten et al. [11] showed that the photodegradation of hair cortisol under the influence of exposure to light may be the cause of the lower cortisol concentrations in white or bright hair. Pigmentation of melanin in dark hair could capture radiation, preventing cortisol from being photodegraded or eliminated as a result of structural alterations in the hair structure.

According to Favretto et al. [37], drugs are more likely to photodegrade in bright hair than in dark hair. Solano et al. [38] explained that the total and proportional concentrations of pheomelanin (red) and eumelanin (black) regulate hair color; hence, black hair is defined by high levels of eumelanin and white hair by low levels of melanin.

Furthermore, Hoting et al. [39] stated that melanin pigments absorb UV radiation, protecting proteins from photodegradation. Thus, black hair is more photostable than white hair [39], and other materials, such as medications and glucocorticoids, are likely shielded from photodegradation by the considerable eumelanin content of dark and black hair [37]. Additionally, it has been shown that the color of a dog’s hair affects its cortisol content; German Shepherds with yellow hair had higher cortisol concentrations than those with agouti and black hair [40].

The substantial difference in HCC between black and white hair is driven by the unique binding properties of eumelanin, the dominant pigment in dark hair. Eumelanin, a complex biopolymer, possesses a high density of reactive functional groups that create strong hydrophobic and electrostatic affinities for lipophilic steroid hormones, including cortisol, effectively sequestering the circulating glucocorticoid as it incorporates into the growing hair shaft [41]. Conversely, white hair lacks this dense eumelanin structure (containing minimal or no pigment), resulting in a significantly lower capacity to bind and retain cortisol [42]. This difference not only explains the higher HCC in dark hair but also relates to the pigment’s protective role, as the light-absorbing properties of eumelanin shield incorporated molecules from the photodegradation that is more pronounced in bright hair [43]. The melanin type, therefore, acts as a key biological determinant of measurable HCC, demonstrating the importance of taking hair color into consideration when interpreting stress biomarkers.

Furthermore, breed-specific factors could influence the results, such as the density of melanin and the corresponding presence of the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) receptor on melanocytes, which is linked to cortisol uptake and can vary between breeds like Holstein-Friesians. We also note briefly that breed differences in heat tolerance (Holstein: low; Montbéliarde: moderate; Brown Swiss: high) and their coat patterns may contribute to the HCC variation observed. In heat stress conditions, Ghassemi Nejad et al. [31] found that cows with over 85% white coats had lower HCC than cows with over 80% black coats. They realized that cattle of the Holstein breed with white coats are more heat-resistant. More research is required to fully understand the impact of hair color on HCC. Most recently, according to Ghassemi Nejad et al. [32], greater hair cortisol was detected in white-coat-colored cows in cold winter compared to black-coated cows. The protein that controls coat color uses the melanocortin signaling system, which modulates the production of cortisol [32,44]. The signaling system is linked to stress adaptation and determines the color of skin and hair. Melanocyte-stimulating hormone and melanocortin receptors, which control hair coat and color [32], are involved in glucocorticoid and pigment production, which is identical in mammals in terms of physiological and biochemical development [40,45]. The transmembrane G-protein-coupled melanocortin-1 receptor (MC1R) and its agonist, melanin-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), and antagonist, agouti protein, regulate the melanin-based coloring process [32,44]. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels rise intracellularly as a result of circulating α-MSH stimulating MC1R in melanocytes. This color pattern occurs in a number of domesticated animals, such as cows, dogs, pigs, and horses [46]. Several domesticated breeds exhibit this color pattern, including dogs, pigs, horses, and cows [46].

HCC is a long-term retrospective biomarker of stress exposure in cattle, which allows for minimally invasive monitoring of herd welfare and management practices. This allows for targeted, timely heat mitigation strategies (like optimizing ventilation or cooling systems), ultimately preventing significant economic losses associated with reduced production, making HCC a highly justifiable addition to routine herd health monitoring. Further research is needed to assess HCC as strong, objective evidence for actionable on-farm decisions.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that hair color can influence measured cortisol concentrations under similar environmental conditions, suggesting that pigmentation should be considered when interpreting hair cortisol data in dairy cattle. Further biochemical validation studies are required to confirm the mechanisms underlying this effect. Black hair can provide valuable insight into individual stress concentrations when pigmentation effects are properly accounted for. Sampling feasibility, estimated cost, and the potential for farmer training to enable on-farm monitoring of stress.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ruminants5040060/s1, Table S1: Means of Hair cortisol concentration (HCC) and standard deviation according to hair color and breed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B., U.B. and R.B.; Data curation, E.B.; Formal analysis, E.B., L.B. and M.A.; Investigation, E.B. and U.B.; Methodology, E.B., L.B., M.A., U.B. and R.B.; Resources, E.B., M.A. and U.B.; Software, E.B.; Supervision, U.B. and R.B.; Validation, L.B., U.B., M.A. and R.B.; Visualization, E.B. and R.B.; Writing—original draft, E.B.; Writing—review and editing: E.B., L.B., M.A., U.B. and R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study adhered to the principles of the ARRIVE guidelines (2.0) for the reporting of animal research. All procedures employed in this study meet ethical guidelines and adhere to Tunisian legal requirements (the Livestock Law No.2005-95 of 18 October 2005).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the laboratory staff at DAFNE, the dairy farm personnel, and Ramzi Albouchi for their valuable help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| AT | Ambient temperature |

| EIA | Enzyme immunoassay |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| HCC | Hair cortisol concentration |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| RIA | Radioimmunoassay |

| SABC | HRP-Streptavidin Conjugate |

| THI | Temperature humidity index |

| TMB | 3,3′,5,5′-Tetra Methyl Benzidine |

References

- Bernabucci, U.; Lacetera, N.; Baumgard, L.H.; Rhoads, R.P.; Ronchi, B.; Nardone, A. Metabolic and hormonal acclimation to heat stress in domesticated ruminants. Animal 2010, 4, 1167–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.W. Effects of heat-stress on production in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 2131–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, S.; Orellana, R.M.; Weng, X.; Marins, T.N.; Dahl, G.E.; Bernard, J.K. Symposium review: The influences of heat stress on bovine mammary gland function. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 5642–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Salem, M.; Bouraoui, R. Heat Stress in Tunisia: Effects on dairy cows and potential means of alleviating it. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 39 (Suppl. S1), 256–259. [Google Scholar]

- Polsky, L.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Invited review: Effects of heat stress on dairy cattle welfare. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 8645–8657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mader, T.L.; Davis, M.S.; Brown-Brandl, T. Environmental factors influencing heat stress in feedlot cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormède, P.; Andanson, S.; Aupérin, B.; Beerda, B.; Guémené, D.; Malmkvist, J.; Manteca, X.; Manteuffel, G.; Prunet, P.; van Reenen, C.G.; et al. Exploration of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function as a tool to evaluate animal welfare. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliokoski, O.; Jellestad, F.K.; Murison, R. A systematic review of studies utilizing hair glucocorticoids as a measure of stress suggests the marker is more appropriate for quantifying short-term stressors. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimbürge, S.; Kanitz, E.; Tuchscherer, A.; Otten, W. Within a hair’s breadth– Factors influencing hair cortisol levels in pigs and cattle. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2020, 288, 113359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saluti, G.; Ricci, M.; Castellani, F.; Colagrande, M.N.; Di Bari, G.; Vulpiani, M.P.; Cerasoli, F.; Savini, G.; Scortichini, G.; D’Alterio, N. Determination of hair cortisol in horses: Comparison of immunoassay vs LC-HRMS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 8093–8105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, W.; Bartels, T.; Heimbürge, S.; Tuchscherer, A.; Kanitz, E. The dark side of white hair? Artificial light irradiation reduces cortisol concentrations in white but not black hairs of cattle and pigs. Animal 2021, 15, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keckeis, K.; Lepschy, M.; Schöpper, H.; Moser, L.; Troxler, J.; Palme, R. Hair cortisol: A parameter of chronic stress? Insights from a radiometabolism study in guinea pigs. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2012, 182, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 7th ed.; National Academic Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, E.C. The discomfort index. Weather Wise 1959, 12, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataallahi, M.; Park, G.W.; Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Park, K.H. Evaluation of earwax and hair cortisol concentration in relation to environmental stressors in Hanwoo cattle. Vet. Res. Commun. 2025, 49, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, M.D.; Tiefenbacher, S.; Lutz, C.K.; Novak, M.A.; Meyer, J.S. Analysis of endogenous cortisol concentrations in the hair of rhesus macaques. Gen. Comp.Endocrinol. 2006, 147, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Ataallahi, M.; Park, K.H. Methodological validation of measuring Hanwoo hair cortisol concentration using bead beater and surgical scissors. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2019, 61, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmi, E.; Souli, A.; Maroini, M.; Abid, I.; Ben-Attia, M.; Salama, A.A.K.; Ayadi, M. Seasonal variations of physiological responses, milk production, and fatty acid profile of local crossbred cows in Tunisia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 56, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, R.; Lahmar, M.; Majdoub, A.; Djemali, M.; Belyea, R. The relationship of temperature-humidity index with milk production of dairy cows in a Mediterranean climate. Anim. Res. 2002, 51, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comin, A.; Prandi, A.; Perić, T.; Corazzin, M.; Dovier, S.; Bovolenta, S. Hair cortisol levels in dairy cows from winter housing to summer highland grazing. Livest. Sci. 2011, 138, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallo-Parra, O.; Manteca, X.; Sabes-Alsina, M.; Carbajal, A.; Lopez-Bejar, M. Hair cortisol detection in dairy cattle by using EIA: Protocol validation and correlation with faecal cortisol metabolites. Animal 2015, 9, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, W.; Heimbürge, S.; Tuchscherer, A.; Kanitz, E. Hair cortisol concentration in postpartum dairy cows and its association with parameters of milk production. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2023, 84–85, 106792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binz, T.M.; Rietschel, L.; Streit, F.; Hofmann, M.; Gehrke, J.; Herdener, M.; Quednow, B.B.; Martin, N.G.; Rietschel, M.; Kraemer, T.; et al. Endogenous cortisol in keratinized matrices: Systematic determination of baseline cortisol levels in hair and the influence of sex, age and hair color. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 284, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-de-la-Vara, M.D.R.; Valdez, R.A.; Lemus-Ramirez, V.; Vázquez-Chagoyán, J.C.; Villa-Godoy, A.; Romano, M.C. Effects of adrenocorticotropic hormone challenge and age on hair cortisol concentrations in dairy cattle. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2011, 75, 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, T.A.; Madureira, A.M.; Silper, B.F.; Nadalin, A.; Tahmasbi, A.; Veira, D.M.; Cerri, R.L.A. Short communication: Factors affecting hair cortisol concentrations in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 7685–7690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedi’c, S.; Panteli’c, M.; Vranješ-Duri’c, S.; Nedi’c, D.; Jovanovi’c, L.; Cebulj- Kadunc, N.; Kobal, S.; Snoj, T.; Kirovski, D. Cortisol concentrations in hair, blood and milk of Holstein and Busha cattle. Slov. Vet. Res. 2017, 54, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesel, U.; Pavić, T. Welfare Assessment of Dairy Cows in Large Slovenian Farms Using Welfare Quality® Assessment Protocol and Hair Cortisol Measurement. Master’s Thesis, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.S.; Novak, M.A. Minireview: Hair cortisol: A novel biomarker of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical activity. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 4120–4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya, D.; Schwartzkopf-Genswein, K.S.; Veira, D.M. Standardization of a non-invasive methodology to measure cortisol in hair of beef cattle. Livest. Sci. 2013, 158, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Lee, B.H. Coat color affects cortisol and serotonin levels in the serum and hairs of Holstein dairy cows exposed to cold winter. Domest. Anim. Endocrin 2023, 82, 106768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Kim, B.W.; Lee, B.H.; Sung, K.I. Coat and hair color: Hair cortisol and serotonin levels in lactating Holstein cows under heat stress conditions. Anim. Sci. J. 2016, 88, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Ghaffari, M.H.; Ataallahi, M.; Jo, J.H.; Lee, H.G. Stress concepts and applications in various matrices with a focus on hair cortisol and analytical methods. Animals 2022, 12, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratacos-Cubarsi, M.; Castellari, M.; Valero, A.; García-Regueiro, J. Hair analysis for veterinary drug monitoring in livestock production. J. Chromatogr. B 2006, 834, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pragst, F.; Balikova, M.A. State of the art in hair analysis for detection of drug and alcohol abuse. Clin. Chim. Acta 2006, 370, 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.E.; Pradhan, D.S.; Soma, K.K. Dehydroepiandrosterone and corticosterone are regulated by season and acute stress in a wild songbird: Jugular versus brachial plasma. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 2537–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heimbürge, S.; Kanitz, E.; Otten, W. The use of hair cortisol for the assessment of stress in animals. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2019, 270, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favretto, D.; Tucci, M.; Monaldi, A.; Ferrara, S.D.; Miolo, G. A study on photodegradation of methadone, EDDP, and other drugs of abuse in hair exposed to controlled UVB radiation. Drug Test. Anal. 2014, 6, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, F. Melanins: Skin pigments and much more– types, structural models, biological functions, and formation routes. New J. Sci. 2014, 2014, 498276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoting, E.; Zimmermann, M.; Höcker, H. Photochemical alterations in human hair. Part II: Analysis of melanin. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 1995, 46, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, A.; Hayssen, V. Measuring cortisol in hair and saliva from dogs: Coat color and pigment differences. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2010, 39, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowland, G.B.; Bernstein, R.M.; Koster, J.; Fiorello, C.; Brenn-White, M.; Liu, J.; Schwartz, L.; Campbell, A.; von Stade, D.; Beagley, J.; et al. Fur Color and Nutritional Status Predict Hair Cortisol Concentrations of Dogs in Nicaragua. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 565346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, P.; Healy, M.; Laird, E.; Marunica Karšaj, J.; Gao, W.; Zgaga, L. The determination of endogenous steroids in hair and fur: A systematic review of methodologies. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2025, 246, 106649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekara, M.N.; Ranganathaiah, C. Chemical and photochemical degradation of human hair: A free-volume microprobe study. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2010, 101, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittilsen, S.; Schjolden, J.; Beitnes-Johansen, I.; Shaw, J.; Pottinger, T.G.; Sørensen, C.; Braastad, B.O.; Bakken, M.; Øverli, Ø. Melanin-based skin spots reflect stress responsiveness in salmonid fish. Hormones Behav. 2009, 56, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kersey, D.C.; Dehnhard, M. The use of noninvasive and minimally invasive methods in endocrinology for threatened mammalian species conservation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2014, 203, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comin, A.; Veronesi, M.C.; Montillo, M.; Faustini, M.; Valentini, S.; Cairoli, F.; Prandi, A. Hair cortisol level as a retrospective marker of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity in horse foals. Vet. J. 2012, 194, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).