Simple Summary

Heat stress is a major challenge for sheep kept in hot, dry regions. This study demonstrates that simple, affordable measurements can predict when animals begin to overheat, allowing action before welfare and productivity are harmed. Twenty Dorper breeding males in northeastern Brazil were observed under two situations: first without any cooling, and then with evaporative cooling (air cooled by passing it through water). Air temperature and humidity, together with body surface temperatures recorded by a thermal camera (a camera that detects heat) over the eye region and the coat, were used to train computer programs that learn from data. These models estimated two early warning signs of heat stress: internal body temperature and breathing rate. The best model predicted internal body temperature with an average error of about 0.15 degrees Celsius and breathing rate with an average error of about 13 breaths per minute. Cooling made the pen milder than outdoors. The findings indicate that low-cost sensors and data-driven models can support early warnings and guide ventilation, shade, and water management in semi-arid farms. This study also highlights how machine learning models can transform raw environmental and physiological data into actionable insights for early decision-making in animal management.

Abstract

The present study aimed to apply machine learning algorithms to estimate respiratory rate (RR, breaths min−1) and rectal temperature (RT, °C) as indicators of thermal stress in Dorper breeding rams, based on environmental and thermal variables obtained through infrared thermography. The algorithms Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Regression (SVR) with radial kernel were employed, using ocular globe temperature (OGT), air temperature (AT), relative humidity (RH), and coat surface temperature (CST) as predictor variables, and rectal temperature (RT) and respiratory rate (RR) as response variables. Data were collected on a property located in Garanhuns, Pernambuco State, Brazil, under two environmental conditions (with and without climate control), totaling 20 monitored animals and 120 paired observations. Model performance was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R2), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE), complemented by cross-validation (k-fold = 10), and model interpretability was assessed using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to quantify the contribution of each predictor variable to model predictions. The results indicated that the RF model showed superior performance in predicting the physiological variables RR and RT, with higher coefficients (RR: R2 = 0.858; RT: R2 = 0.687) and lower error values. For RR, the RF model achieved RMSE = 16.38 and MAE = 13.33; while for RT, the errors were RMSE = 0.217 and MAE = 0.154. In contrast, the radial kernel SVR model showed lower performance, with R2 values of 0.742 (RR) and 0.533 (RT), and RMSE and MAE values of 21.05 and 17.38 for RR, and 0.262 and 0.196 for RT, respectively. The application of machine learning-based models proved to be a viable and accurate alternative for estimating physiological indicators of thermal stress, contributing to the development of automated thermal management strategies for sheep in the Brazilian semi-arid region. The proposed data-driven approach demonstrates that low-cost thermal sensors combined with explainable artificial intelligence can support automatic decision-making for climate adaptation and animal welfare in semi-arid sheep production systems.

1. Introduction

Heat stress is one of the main challenges to animal productivity in regions with tropical and subtropical climates, such as the Brazilian semi-arid region, where sheep are often subjected to adverse conditions such as high temperatures, low relative humidity, and intense solar radiation. Such environmental factors not only compromise animal welfare but also directly affect physiological and reproductive parameters, leading to significant economic losses in production systems [1,2].

Sheep maintain homeothermy through mechanisms such as vasodilation, increased respiratory rate, and behavioral adjustments, including shade-seeking and reduced activity. However, their limited sweating capacity and dense fleece make them vulnerable to heat accumulation, even in adaptive breeds such as Dorper.

Traditionally, bioclimatic indices such as the Temperature and Humidity Index (THI) have been used to estimate animal thermal comfort. However, these indices present methodological limitations, as they do not integrate the complex interactions between environmental and physiological responses [3]. This limitation reinforces the need for more accurate predictive methods based on artificial intelligence (AI).

Among these techniques, machine learning (ML) stands out for its ability to identify nonlinear patterns in large datasets and generate robust predictive models [4]. Algorithms such as Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Regression (SVR) have been successfully applied in animal biometeorology studies, demonstrating high accuracy and adaptability across species [5,6]. In precision livestock farming, recent studies indicate that ML-based models can outperform traditional statistical approaches in predicting physiological responses, particularly due to their efficiency in processing noisy and correlated data from multiple sensors [7].

The integration of thermographic and environmental data has been widely recognized as a reliable approach for assessing heat stress in small ruminants. Recent studies [8,9] demonstrated that combining surface temperature and ambient data using explainable machine learning techniques allows for improved prediction of physiological responses and provides valuable insights into animal–environment interactions.

Although these methods are well established in cattle and pig production systems, few studies have focused on breeding sheep, especially under semi-arid Brazilian conditions. The thermoregulatory complexity of sheep under local microclimates demands predictive models that integrate environmental and physiological information synergistically.

Recent advances in thermal imaging combined with machine learning have expanded the understanding of heat stress responses in several livestock species. In cattle, thermographic indicators such as ocular and coat temperatures have been shown to accurately predict core body temperature and respiratory rate using explainable models such as SHAP, Random Forest, and XGBoost [8,10]. Similar findings were observed in swine, where surface temperature patterns were linked with heat load and behavioral changes under high ambient temperature [11]. Other studies have highlighted the integration of artificial intelligence in animal biometeorology, emphasizing its capacity to quantify physiological resilience and support early-warning systems for welfare monitoring [9,12]. Although these studies address different species, their results reinforce the potential of combining environmental and physiological data with interpretable algorithms to improve the prediction of thermal stress in small ruminants, especially under semi-arid conditions.

Therefore, this study aimed to apply Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Regression (SVR) algorithms to estimate respiratory rate (RR) and rectal temperature (RT) as indicators of heat stress in Dorper breeding rams using environmental and thermal variables obtained by infrared thermography. Additionally, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) were applied to interpret model predictions and determine the relative importance of each predictor variable. The findings aim to support the development of automated, explainable, and sustainable thermal management systems for sheep production in semi-arid regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location of the Experiment

Experimental data were obtained from a commercial sheep farm located in the municipality of Garanhuns, Pernambuco, Brazil (8°53′25″ S, 36°29′34″ W). This region belongs to the Agreste of Pernambuco and is characterized by a tropical highland climate, with mild temperatures during part of the year and significant thermal variations, which makes it relevant for studies of animal environment. The city is located at an average altitude of 842 m above sea level and has an average annual temperature of approximately 21.7 °C, with variations between 19.4 °C in the coldest months and 23.2 °C in the warmest [13].

2.2. Experimental Design and Data Collection

The experiment was conducted in two environmental conditions: natural ventilation (Phase 1) and evaporative cooling (Phase 2), lasting 22 and 43 consecutive days, respectively. During both phases, six Dorper breeding rams (2.5 ± 0.5 years old; 70.5 ± 5.2 kg) were housed in individual pens (2.0 × 1.0 m) with visual contact and ad libitum access to water and feed formulated according to [14]. Environmental data—air temperature (AT), relative humidity (RH), wind speed (WS), and black globe temperature (BGT)—were continuously recorded at 10 min intervals using a HOBO® U12-013 datalogger positioned 1.0 m above the ground. Infrared thermographic images were captured daily using a FLIR E8-XT camera (FLIR Systems Inc., Wilsonville, OR, USA) at 1 m distance, between 09:00 and 15:00 h, under stable lighting and without direct sunlight. Images focused on the ocular globe (OGT) and coat surface temperature (CST). Rectal temperature (RT) and respiratory rate (RR) were measured immediately after image capture using a digital thermometer (±0.1 °C) and visual observation of flank movements per minute. All measurements were paired with their corresponding environmental records, forming an integrated dataset for modeling (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Housing bay with 80% reflective screen.

2.3. Determination of Meteorological and Physiological Variables

Environmental conditions were continuously monitored using sensors connected to a HOBO 4 datalogger (Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, MA, USA). The equipment automatically recorded air temperature (AT), relative humidity (RH), and black globe temperature (BGT). Measurement ranges were −20 to 70 °C for temperature and 5 to 95% for humidity, with accuracies of ±0.35 °C and ±2.5%, respectively.

The BGT was obtained from a hollow polyethylene sphere painted matte black (diameter 15 cm), containing a thermistor sensor inside, coupled to the datalogger for continuous recording of global thermal data.

Thermal images were captured using a FLIR E8-XT infrared thermal camera, FLIR Systems, Wilsonville, Oregon, USA (resolution: 320 × 240 pixels; thermal sensitivity < 0.06 °C; emissivity: 0.98). The camera was positioned approximately 1.5 m from the animals at a perpendicular angle to the right side of the body. Images were obtained from the ocular globe (OGT) and coat surface (CST), which were later used as thermal predictors for estimating physiological responses.

2.4. Data Selection and Preparation

A total of 120 paired observations were collected during both experimental phases. All data were checked for consistency, duplication, and correct coding. No missing or inconsistent values were identified, so no imputation or exclusion was required.

To examine linear relationships among variables, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. Multicollinearity was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), with all predictors showing acceptable values (VIF < 5).

The dataset was standardized using z-score normalization to align variable scales and improve the stability of the learning algorithms, particularly the SVR, which is sensitive to magnitude differences.

2.5. Data Division

The dataset was randomly divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets, maintaining the proportional distribution of the response variables through stratified sampling. To improve model robustness, a 10-fold cross-validation strategy was applied during training.

2.6. Machine Learning Models

To predict the physiological variables rectal temperature (RT) and respiratory rate (RR), two supervised learning algorithms were implemented: Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Regression (SVR), both configured for regression tasks. Analyses were conducted in R (version 4.2.3) using RStudio (version 2023.03) and the packages randomForest [15], e1071 [16], caret, and Metrics. These packages offer validated implementations for model fitting, hyperparameter tuning, cross-validation, and visualization.

Although more recent ensemble learning algorithms such as Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) have become increasingly popular in agricultural prediction tasks due to their scalability, efficiency, and ability to handle complex nonlinear data structures [17,18], the Random Forest algorithm was chosen in this study because of its robustness in smaller datasets and lower risk of overfitting. Furthermore, when combined with SHAP-based interpretability, Random Forest provides clear insights into variable importance and model decision processes, which are essential for applied animal biometeorology studies.

The RF model was tuned with 100 estimators (trees), an undefined maximum depth, and mean squared error as the split criterion. For the SVR, a radial basis function (RBF) kernel was used, due to its capacity to model nonlinear relationships among environmental and physiological variables. Hyperparameters (C, epsilon, and gamma) were optimized through grid search cross-validation (k = 10) using the caret package.

Model performance was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R2), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). Scatter plots of predicted vs. observed values were also generated to visualize adherence to the identity line (y = x).

After model training and validation, both RF and SVR models were analyzed for interpretability using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), a unified framework that decomposes each model prediction into additive feature contributions. This approach provides a transparent evaluation of how each input variable influences the output, complementing numerical performance metrics and enhancing biological interpretability. The adoption of SHAP was motivated by its growing application in animal biometeorology. Recent studies [8] have successfully applied explainable machine learning to predict core body temperature in dairy cows using infrared thermography, demonstrating how SHAP identifies the most influential environmental and physiological factors in thermal stress prediction.

2.7. Model Interpretability (SHAP Analysis)

To quantify the contribution of each predictor variable to the model outputs, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) were computed based on game theory principles [8,19,20]. This approach replaces traditional PCA-based interpretation, providing model-specific insights and enabling visualization of both feature importance and the direction of influence on the response variables.

The SHAP method was chosen because of its growing application in animal biometeorology and explainable machine learning. Recent studies [8] demonstrated that SHAP can effectively interpret how thermal and physiological features contribute to the prediction of core body temperature in livestock, improving transparency and model trust in practical farm management scenarios.

In this study, SHAP analysis was applied specifically to the Random Forest (RF) model, as its tree-based structure enables direct extraction of feature contributions and intuitive visualization of predictor effects. Through this interpretability framework, it was possible to quantify the relative influence of each environmental and thermographic variable—ocular globe temperature (OGT), coat surface temperature (CST), air temperature (AT), and relative humidity (RH)—on the predicted physiological responses (rectal temperature and respiratory rate).

This procedure provided a biological understanding of how each predictor influenced the model output: positive SHAP values indicated an increase in predicted heat load (higher RT or RR), while negative values indicated lower thermal stress levels. Such analysis enhances the interpretability of complex models and reinforces their reliability for practical decision-making in precision livestock management.

2.8. Model Performance

Model performance was evaluated using three statistical metrics: Coefficient of determination (R2): the proportion of variance explained by the model; Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): penalizes large deviations; Mean Absolute Error (MAE): represents the mean absolute deviation between predictions and observations. Metrics were calculated for both training and test sets to compare model generalization and overfitting tendencies.

In addition to these numerical indicators, the results were graphically analyzed using scatter plots of predicted versus observed values, allowing visual inspection of model fit relative to the identity line (y = x). This combined numerical and graphical approach ensured a comprehensive evaluation of predictive accuracy and reliability.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evaluation of Environmental Parameters in the Two Experimental Phases

The analysis of the environmental conditions revealed marked differences between the periods without air conditioning (Phase 1) and with artificial air conditioning (Phase 2). The graphs presented (Figure 2) clearly demonstrate the variation in air temperature and relative humidity, both in the external environment and in the pen where the animals were kept.

Figure 2.

Variation in air temperature (°C) and relative humidity (%) in the external and internal environments (bay), during periods without air conditioning) and with artificial air conditioning. (A) Air temperature—without air conditioning; (B) Air temperature—with air conditioning; (C) Relative humidity—without air conditioning; (D) Relative humidity—with air conditioning.

In Phase 1, it was observed that temperatures in the bay closely followed the variations in the external temperature, with averages above 27 °C during the peak of the day. Relative humidity, on the other hand, showed a downward trend in the hottest hours, reaching values below 55%. These conditions are unfavorable to the thermal comfort of sheep, as they hinder heat dissipation by evaporation, especially when natural ventilation is insufficient.

With the introduction of the evaporative HVAC system (Phase 2), the thermal effects were significantly mitigated. Temperatures inside the bay became consistently lower than those outside, with a daily average reduced by approximately 2 °C. Indoor relative humidity also increased, especially in the hottest hours, reaching up to 15% higher than outdoors. This indicates the effectiveness of the evaporative system in improving the microclimate of the housing environment, promoting more stable and favorable conditions for animal welfare.

These results are in line with [21], who demonstrated that artificial air conditioning contributes to the reduction in heat stress in sheep in semi-arid regions. Reference [22] also emphasized the importance of controlled environments to maintain physiological parameters within normal ranges.

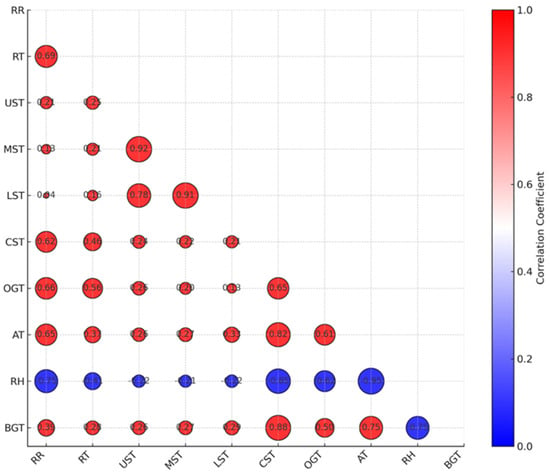

3.2. Pearson Correlation and Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

The Pearson correlation analysis between the physiological variables (rectal temperature—RT and respiratory rate—RR) and the environmental variables allowed the identification of significant associations that supported the selection of predictors for the models (Figure 3). It was observed that coat surface temperature (CST), ocular globe temperature (OGT), and air temperature (AT) showed moderate positive correlations with RT and RR, while relative humidity (RH) showed a negative correlation, especially with RR. This behavior aligns with the thermoregulatory physiology of sheep, since high RH hinders evaporative heat dissipation, directly influencing the animals’ respiratory response [23,24].

Figure 3.

Correlation between physiological and meteorological variables. The color scale ranges from blue (negative correlation) to red (positive correlation), with values between −1 and +1, indicating the strength and direction of the associations between the variables.

Complementarily, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to explore multivariate relationships among variables. The first two components (PC1 and PC2) together explained 76.1% of the total variance, with 52.4% attributed to PC1 and 23.7% to PC2. In the correlation circle (Figure 4), the variables CST, OGT, and AT presented longer vectors oriented positively to PC1, indicating high contribution. In contrast, RH showed an inversely oriented vector, reinforcing its negative relationship with thermal variables [24].

Figure 4.

Correlations (circle of correlations) of the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). ocular globe temperature (TGO), coat surface temperature (CST), rectal temperature (RT), respiratory rate (RR), air temperature (TAR), relative humidity (RH), lower scrotal temperature (TINF), medial scrotal temperature (TMED), upper scrotal temperature (TSUP).

Based on these results, TGO, CST, TAR, and RH were selected as predictor variables for the machine learning models, as they showed high correlation with physiological responses and significant representativeness in the multivariate structure.

3.3. Descriptive Analyses of the Selected Variables

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables used as predictors in the models for estimating rectal temperature (RT) and respiratory rate (RR).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the predictor variables of the study.

The OGT variable presented the lowest coefficient of variation (CV = 2.38%), indicating low dispersion and stability across measurements. This confirms its reliability as a physiological indicator of thermal response, as previously demonstrated by [25]. CST and AT showed intermediate variation (8–9%), reflecting natural microclimatic fluctuations. RH exhibited the highest variability (12.32%), consistent with semi-arid oscillations and the evaporative system’s performance [26].

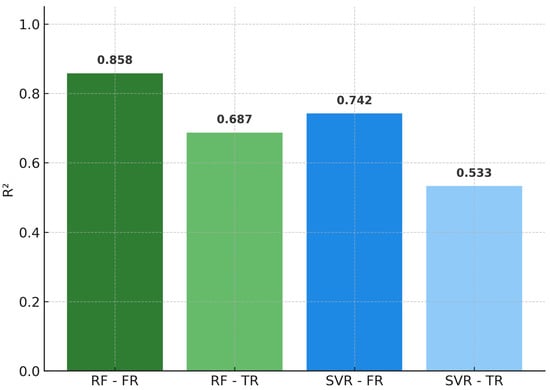

3.4. Model Performance

Table 2 summarizes the performance indicators of the Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Regression (SVR) models.

Table 2.

Performance indicators of the Random Forest and SVR Radial models.

The RF model demonstrated superior accuracy for both variables, reinforcing its robustness in datasets with environmental variability and biological complexity [27,28]. Its ensemble nature minimizes overfitting and effectively captures nonlinear and correlated interactions.

Figure 5 and Figure 6 graphically illustrate the values of R2, RMSE and MAE, allowing a clear comparison between the models. Random Forest’s superior performance reinforces its robustness in the face of datasets with environmental variability and biological complexity. As it is a model based on multiple decision trees, RF reduces the risk of overfitting and deals well with nonlinearity and collinearity between variables [27,28]. In addition, its ability to perform automatic weighting on the importance of each variable makes it especially suitable for multivariate problems in the natural environment, such as those observed in animal production [29].

Figure 5.

Coefficient of Determination (R2) values obtained for the models Random Forest (RF) e Support Vector Regression with kernel radial (SVR Radial), applied to the prediction of respiratory rate (RR) and rectal temperature (RT) of breeding sheep. The R2 expresses the proportion of the variance of the data explained by the model. Values closer to 1 indicate better predictive performance.

Figure 6.

Comparison of mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) values for the RF and SVR Radial models in the prediction of the physiological variables RF and RT. The RMSE and the MAE are presented in the respective units of the variables (movements per minute for RR and °C for RT), reflecting the mean deviation between the predicted values and the observed values. Lower values indicate higher model accuracy.

3.5. Explainable Machine Learning: SHAP and Partial Dependence Analysis

To enhance the interpretability of the predictive models, the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method was employed to quantify the contribution of each predictor variable to the model outputs [23,30,31]. SHAP values provide a unified approach to explain how changes in each input variable influence the prediction of rectal temperature (RT) and respiratory rate (RR), facilitating the translation of complex model behavior into biologically meaningful insights.

The SHAP summary plots (Figure 7 and Figure 8) illustrate the contribution and direction of each predictor variable to the Random Forest model outputs for rectal temperature (RT) and respiratory rate (RR). Each point represents a single observation, with colors indicating the magnitude of the corresponding feature value (from low to high).

Figure 7.

SHAP summary plot for the Random Forest model predicting rectal temperature (RT).

Figure 8.

SHAP summary plot for the Random Forest model predicting respiratory rate (RR).

The updated figures now clearly display the full distribution of SHAP values, enabling a more transparent interpretation of feature importance and directionality. Ocular globe temperature (OGT) and coat surface temperature (CST) showed the strongest positive influence on RT and RR, followed by ambient temperature (AT) and relative humidity (RH), confirming their relevance in explaining thermal stress variations in Dorper rams.

The partial dependence plots (PDPs) provided a complementary visualization of these effects. In both cases, OGT exhibited a monotonic positive relationship with RT and RR: as ocular temperature increased beyond 35 °C, both physiological indicators rose sharply, signaling heat stress onset. CST followed a similar but slightly delayed pattern, indicating that surface warming occurs after internal temperature changes (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Partial dependence plots (PDP) for the Random Forest model showing the marginal effects of OGT and CST on rectal temperature (RT).

Figure 10.

Partial dependence plots (PDP) for the Random Forest model showing the marginal effects of OGT and CST on respiratory rate (RR).

From a practical standpoint, these findings highlight the potential of infrared thermography combined with explainable machine learning as a non-invasive tool to identify early physiological responses to thermal stress. The integration of SHAP and PDP analyses allowed not only the evaluation of prediction accuracy but also the understanding of why the model produces such predictions—essential for developing reliable, interpretable tools in animal biometeorology [32].

3.6. Cross-Validation of Models

To evaluate the robustness and generalizability of the developed models, a 10-fold cross-validation (k = 10) was performed using the complete dataset. This technique allows a more reliable estimation of model performance, minimizing the bias caused by a single random division between training and testing subsets [32].

The results confirmed the superior consistency of the Random Forest (RF) model. For RR, RF achieved a mean coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.841 and a mean root mean squared error (RMSE) of 17.02 mov/min, with low variability between folds (SD = 2.31). For RT, the mean R2 was 0.669 and the mean RMSE was 0.225 °C, also with low dispersion, confirming its strong generalization capacity and stability across subsets (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

RMSE (A) and MAE (B) values obtained by the models Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Regression with kernel radial (SVR Radial) in the prediction of respiratory rate (RR) and rectal temperature (RT) of sheep. Units: RMSE and MAE in mov/min for FR and in °C for TR. Models with lower values indicate greater predictive accuracy.

In contrast, the Support Vector Regression (SVR) model showed lower and more variable results, with mean R2 values of 0.719 (RR) and 0.498 (RT). The higher RMSE dispersion observed in SVR indicates greater sensitivity to data scaling and hyperparameter tuning, confirming the limitations of kernel-based regressors in heterogeneous biological datasets [33,34].

The superior performance and stability of the RF model demonstrate its robustness for predicting physiological indicators in animals exposed to dynamic environmental conditions. Beyond accuracy, the model’s explainability through SHAP reinforces its value as a decision-support tool for animal welfare management.

This combination of predictive precision and interpretability supports the development of early-warning systems for heat stress and adaptive management strategies for semi-arid livestock production systems, enabling producers to anticipate stress events and optimize environmental control practices.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that machine learning algorithms, particularly Random Forest (RF), are effective tools for predicting physiological responses associated with heat stress in breeding sheep. The RF model exhibited superior predictive performance compared to Support Vector Regression (SVR) with a radial kernel, due to its ability to capture nonlinear interactions and manage multicollinearity among environmental and thermal variables.

The high accuracy observed for the respiratory rate (RR) reinforces its role as a sensitive early indicator of thermal discomfort and physiological adjustment to environmental changes. In contrast, the lower variability of rectal temperature (RT) contributed to slightly lower predictive performance, reflecting its more homeostatic nature and stability in response to short-term fluctuations.

The integration of explainable AI techniques, such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Partial Dependence Plots (PDP), provided biological interpretability to the models, identifying ocular globe temperature (OGT) and coat surface temperature (CST) as the most influential predictors. These insights strengthen the practical applicability of thermography-based monitoring for precision livestock farming.

Cross-validation confirmed the robustness and generalization capacity of the RF model, highlighting its potential for real-world applications in automated management systems and real-time animal monitoring. Collectively, these findings advance the field of precision environment control in small ruminant farming, offering scientific and technological foundations for the development of adaptive management strategies that promote thermal comfort, welfare, and productivity in semi-arid regions.

For future studies, it is recommended to expand the dataset and explore additional algorithms such as Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), along with behavioral and microclimatic variables. The integration of remote sensing, IoT, and edge-computing technologies is also encouraged to develop even more robust, interpretable, and scalable predictive models adapted to tropical livestock systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.G.d.C.S., H.P., W.A.d.S. and G.L.P.d.A.; Data curation, A.M.G.d.C.S., H.P., W.A.d.S. and A.S.M.; Formal analysis, A.M.G.d.C.S., A.S.M., H.J.d.L.P., N.A.F.M. and M.V.d.S.; Funding acquisition, H.P. and M.V.d.S.; Investigation, A.M.G.d.C.S., W.A.d.S., H.J.d.L.P. and G.L.P.d.A.; Methodology, A.M.G.d.C.S., H.P., W.A.d.S., A.S.M., N.A.F.M., M.B.F. and M.V.d.S.; Project administration, H.P.; Resources, H.P., G.L.P.d.A., N.A.F.M., M.B.F. and M.V.d.S.; Software, A.M.G.d.C.S., W.A.d.S. and A.S.M.; Supervision, H.P.; Validation, A.M.G.d.C.S., H.P., W.A.d.S., H.J.d.L.P., G.L.P.d.A. and M.B.F.; Visualization, A.M.G.d.C.S., H.P., W.A.d.S., A.S.M., H.J.d.L.P., G.L.P.d.A., N.A.F.M., M.B.F. and M.V.d.S.; Writing—original draft, A.M.G.d.C.S., H.P. and G.L.P.d.A.; Writing—review and editing, A.M.G.d.C.S., H.P., W.A.d.S., A.S.M., H.J.d.L.P., G.L.P.d.A., N.A.F.M., M.B.F. and M.V.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals of the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco (CEUA/UFRPE), under (protocol code 6990060223), approved on 8 February 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this research is confidential and are made available upon request by the reader.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Joy, A.; Dunshea, F.R.; Leury, B.J.; Clarke, I.J.; DiGiacomo, K.; Chauhan, S.S. Resilience of Small Ruminants to Climate Change and Increased Environmental Temperature: A Review. Animals 2020, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silanikove, N. Effects of Heat Stress on the Welfare of Extensively Managed Domestic Ruminants. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2000, 67, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderaro, C.F.; Brennecke, K.; Pereira, L.A.M.; Adorno, L.S.B.; Martins, O.O.; de Lima, T.O.; Sgavioli, S. Índices de Conforto Térmico Em Aves de Produção—Revisão Sistemática. Res. Soc. Dev. 2023, 12, e11012641910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnighausen, V.C.R. Estimation of Thermal Comfort Indexes for Production Animals Using Multiple Linear Regression Models. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2019, 7, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Peng, D.; Gu, X. Predicting Rectal Temperature and Respiration Rate Responses in Lactating Dairy Cows Exposed to Heat Stress. J. Dairy. Sci. 2020, 103, 5466–5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezov, D.; Hristov, H.; Dimov, D.; Alexiev, K. Predicting the Rectal Temperature of Dairy Cows Using Infrared Thermography and Multimodal Machine Learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, R.; Aguilar, J.; Toro, M.; Pinto, A.; Rodríguez, P. A Systematic Literature Review on the Use of Machine Learning in Precision Livestock Farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 179, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yan, G.; Li, F.; Lin, H.; Jiao, H.; Han, H.; Liu, W. Optimized Machine Learning Models for Predicting Core Body Temperature in Dairy Cows: Enhancing Accuracy and Interpretability for Practical Livestock Management. Animals 2024, 14, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebez, E.B.; Sejian, V.; Silpa, M.V.; Kalaignazhal, G.; Thirunavukkarasu, D.; Devaraj, C.; Nikhil, K.T.; Ninan, J.; Sahoo, A.; Lacetera, N.; et al. Applications of Artificial Intelligence for Heat Stress Management in Ruminant Livestock. Sensors 2024, 24, 5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Li, Y.; Bindelle, J.; Jin, Z.; Fang, T.; Xing, M.; Guo, L.; Wang, W. Predicting Physiological Responses of Dairy Cows Using Comprehensive Variables. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 207, 107752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Rodríguez, L.F.; Titto, E.A.L.; Henrique, F.L.; Longo, A.L.S.; Hooper, H.B.; Pereira, T.L.; Pereira, A.M.F.; Titto, C.G. Termografia Infravermelha da Superfície Ocular como Indicador de Estresse em Suínos na Fase de Creche. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2017, 37, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhao, K.; Duan, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, Q.; Hong, X.; Zhang, R.; Wang, M. Detection of Respiratory Rate of Dairy Cows Based on Infrared Thermography and Deep Learning. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLIMATE-DATA. ORG Clima de Garanhuns: Tempo Em Garanhuns e Temperatura Por Mês. Available online: https://pt.climate-data.org/america-do-sul/brasil/pernambuco/garanhuns-4458/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: Sheep, Goats, Cervids, and New World Camelids, 1st ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and Regression by RandomForest. R. News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D.; Dimitriadou, E.; Hornik, K.; Weingessel, A.; Leisch, F.; Chang, C.-C.; Lin, C.-C. E1071: Misc Functions of the Department of Statistics, Probability Theory Group (Formerly: E1071), TU Wien. R Package Version 2019, 1. Available online: https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=fc1a25fa-4c7b-4b91-a707-1ce7ce33659e (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NeurIPS 2017); Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3146–3154. Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/hash/6449f44a102fde848669bdd9eb6b76fa-Abstract.html (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning: A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable, 2nd ed.; 2022; Available online: https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NeurIPS 2017); Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 4765–4774. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/hash/8a20a8621978632d76c43dfd28b67767-Abstract.html (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- da Silva, T.G.P.; Lopes, L.A.; de Carvalho, F.F.R.; Batista, Â.M.V.; Guim, A.; dos Santos Nascimento, J.C.; da Silva Neto, J.F. Respostas Fisiológicas de Ovinos Alimentados Com Genótipos de Palma Forrageira. Med. Vet. (UFRPE) 2021, 15, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejian, V.; Silpa, M.V.; Reshma Nair, M.R.; Devaraj, C.; Krishnan, G.; Bagath, M.; Chauhan, S.S.; Suganthi, R.U.; Fonseca, V.F.C.; König, S.; et al. Heat Stress and Goat Welfare: Adaptation and Production Considerations. Animals 2021, 11, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starling, J.M.C.; Silva, R.G.D.; Cerón-Muñoz, M.; Barbosa, G.S.S.C.; Costa, M.J.R.P.D. Análise de Algumas Variáveis Fisiológicas Para Avaliação Do Grau de Adaptação de Ovinos Submetidos Ao Estresse Por Calor. R. Bras. Zootec. 2002, 31, 2070–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.S.B.; Paiva, S.R.; Silva, E.C.; McManus, C.M.; Caetano, A.R.; Façanha, D.A.E.; de Sousa, M.A.N. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Different Varieties of Morada Nova Hair Sheep from Brazil. Genet. Mol. Res. 2014, 13, 2480–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.d.F.A.; Pandorfi, H.; Soares, R.G.F.; Almeida, G.L.P.d.; Santana, T.C.; Silva, M.V.d. Computational Techniques for Analysis of Thermal Images of Pigs and Characterization of Heat Stress in the Rearing Environment. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 3203–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, G.T.B.; Pandorfi, H.; da Silva, M.V.; Montenegro, A.A.D.A.; de Sousa, L.D.B.; Desenzi, R.; da Silva, J.L.B.; de Oliveira-Júnior, J.F.; Mesquita, M.; de Almeida, G.L.P.; et al. Bioclimatic Zoning for Sheep Farming through Geostatistical Modeling in the State of Pernambuco, Brazil. Animals 2023, 13, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.R.; Edwards, T.C.; Beard, K.H.; Cutler, A.; Hess, K.T.; Gibson, J.; Lawler, J.J. Random Forests for Classification in Ecology. Ecology 2007, 88, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, R.V.d.; Campos, J.C.D.; Pagin, G.; Pereira, D.F.; Conceição, A.R.; Tabile, R.A.; Martello, L.S. Non-Invasive Assessment of Heat Comfort in Dairy Calves Based on Thermal Signature. Dairy 2025, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.R.d.; Pires, J.A.d.S.; Silva, R.d.S.; Rodrigues, R.C.M.; Mascarenhas, N.M.H.; Batista, L.F.; Oliveira, J.P.F.d.; Vaz, A.F.d.M.; de Souza, B.B. Efeitos Do Estresse Térmico Induzido Sobre Os Parâmetros Fisiológicos, Bioquímicos e Hormonais de Ovinos Nativos de Diferentes Genótipos Em Câmara Climática. Obs. Econ. Latinoam. 2025, 23, e9634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.; Nelson, G.; Mayberry, D.; Herrero, M. Impacts of Heat Stress on Global Cattle Production during the 21st Century: A Modelling Study. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e192–e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Johnson, K. Applied Predictive Modeling; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4614-6848-6. [Google Scholar]

- Smola, A.J.; Schölkopf, B. A Tutorial on Support Vector Regression. Stat. Comput. 2004, 14, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I.; Gunn, S.; Nikravesh, M.; Zadeh, L.A. Feature Extraction: Foundations and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; Volume 207, ISBN 3540354883. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).