Creative and Metacognitive Strategies in Anti-Bullying Programs: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Creativity as a Buffer Against Aggressive Behaviors

1.2. Metacognition Buffer Against Aggressive Behaviors

2. Research Aims

- What is the theoretical background that justifies the application of these tools in anti-bullying programs?

- How common are school anti-bullying programs that integrate creativity and metacognition mechanisms?

- What are the elements of methodology applied in anti-bullying educational programs that use creative and metacognitive strategies?

- What evaluation methods are applied in these programs, and what is the effectiveness of these programs?

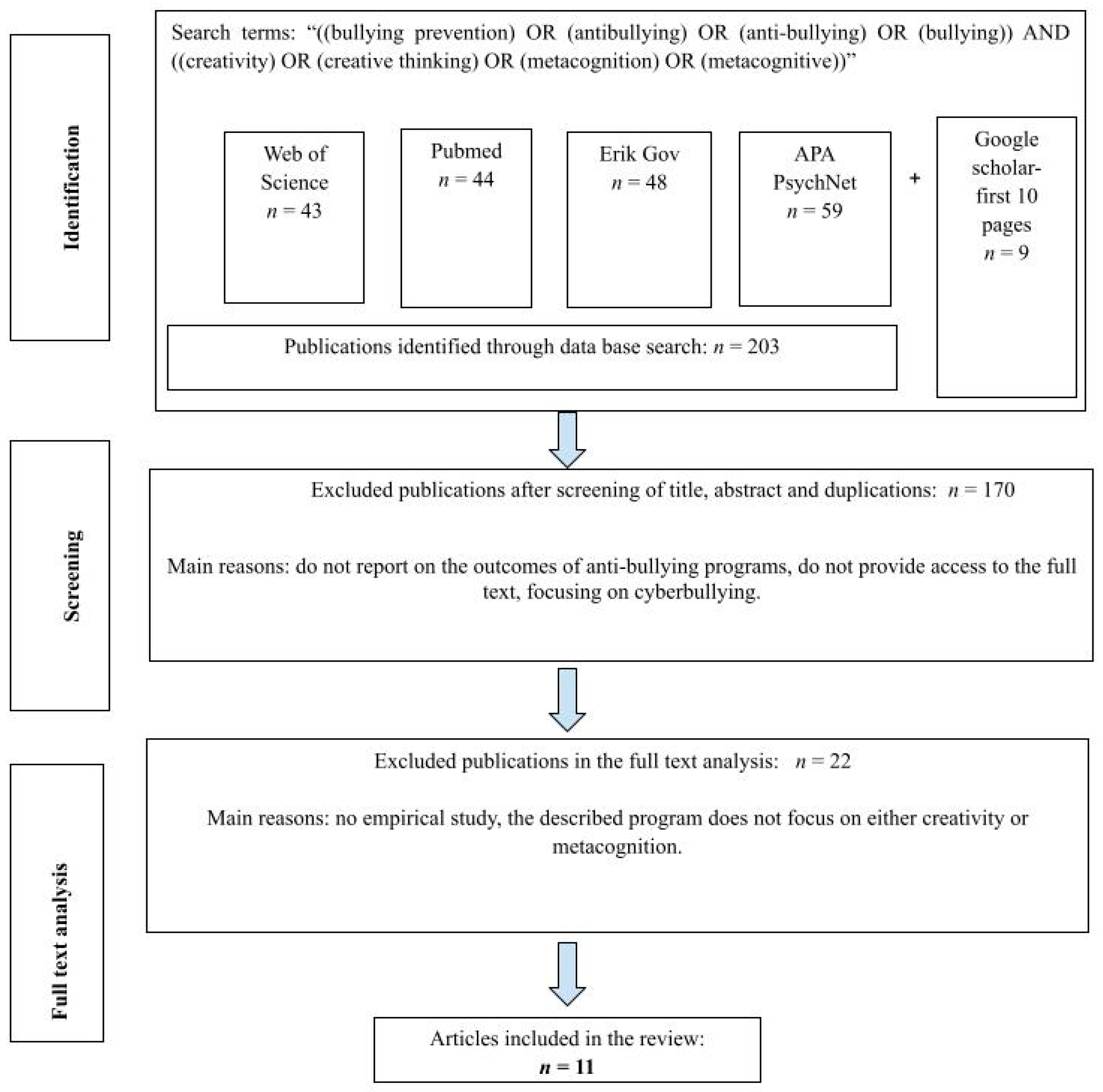

3. Methods

3.1. Search of the Literature

3.2. Establishing Eligibility Criteria

3.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

4. Results of the Literature Search

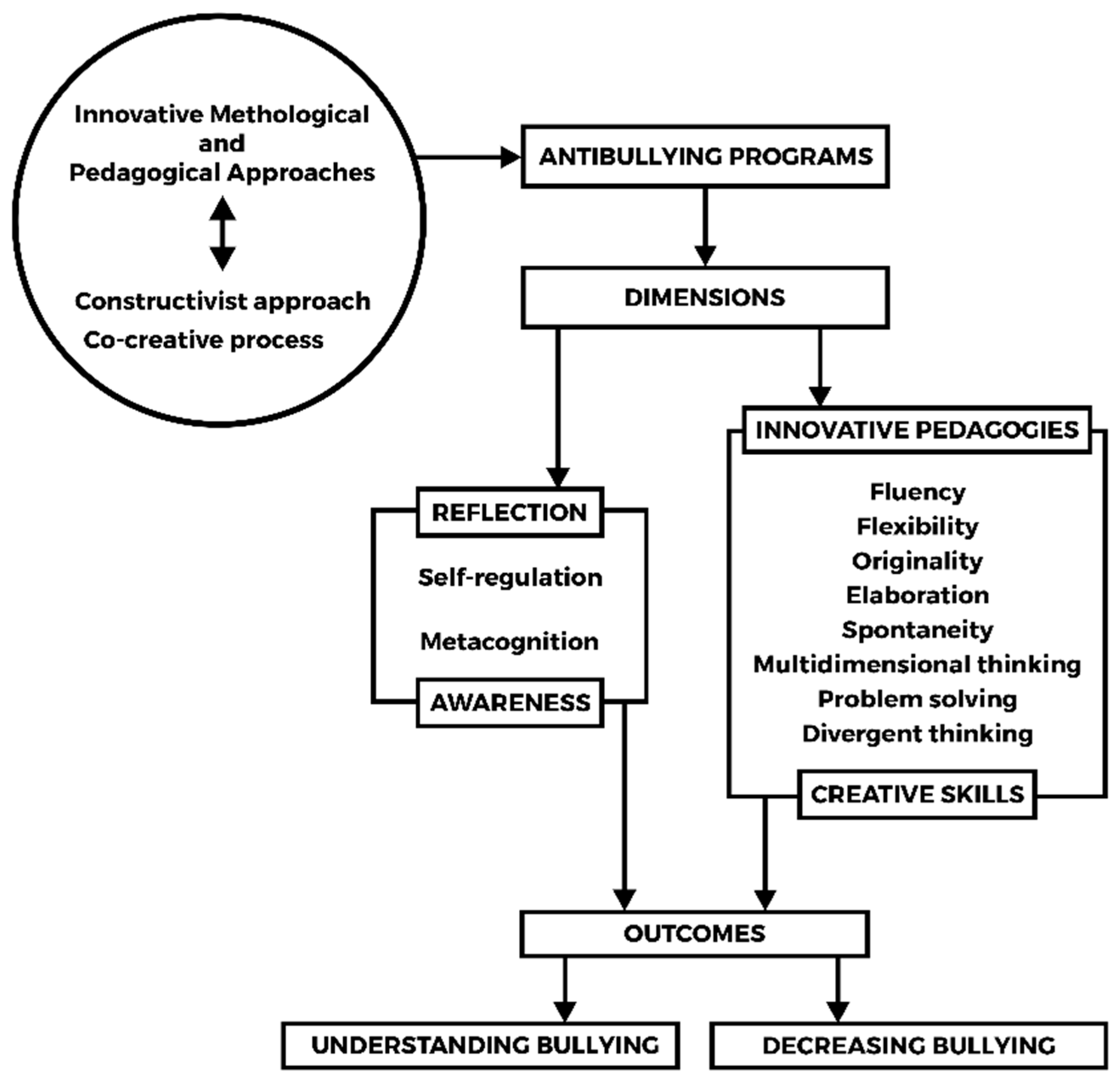

Analysis of the Anti-Bullying Programs in the Included Publications

- (a)

- Creativity and metacognition theoretical background in the anti-bullying programs;

- (b)

- Creative and metacognitive tools in the anti-bullying programs;

- (c)

- The educational training methodology applied in these anti-bullying programs;

- (d)

- Tools for evaluating the outcomes of these anti-bullying programs.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Practical Implications, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akpan, J. P., & Notar, C. E. (2016). Is bullying a global problem or just in America? A comparative meta-analysis of research findings. International Journal of Education and Social Science, 3(9), 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Aleinikov, A. G. (1989). Creative metapedagogy: D-day. AlmaMater Higher Education Bulletin, 1, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Aljughaiman, A., & Mowrer-Reynolds, E. (2005). Teachers’ conceptions of creativity and creative students. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 39(1), 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadori, A., Intra, F. S., Taverna, L., & Brighi, A. (2023). Systematic review of intervention and prevention programs to tackle homophobic bullying at school: A socio-emotional learning skills perspective. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthonysamy, L., Sugendran, P., Wei, L. O., & Hoon, T. S. (2024). An improved metacognitive competency framework to inculcate analytical thinking among university students. Education and Information Technologies, 29, 22475–22497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill, R. M., & Major, J. (2020). What motivates higher education educators to innovate? Exploring competence, autonomy, and relatedness—And connections with wellbeing. Educational Research, 62(2), 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R. (2020). Reflections on the field of metacognition: Issues, challenges, and opportunities. Metacognition Learning, 15, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Huerta, P., Muela, A., & Larrea, I. (2021). Student engagement and creative confidence beliefs in higher education. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 40, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, A. A., Silver, S. H., & Veague, H. B. (2010). Cognitive control reduces sensitivity to relational aggression among adolescent girls. Social Neuroscience, 5(5–6), 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Multifaceted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning. Child Development, 67(3), 1206–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barford, K. A., & Smillie, L. D. (2016). Openness and other Big Five traits in relation to dispositional mixed emotions. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R. A. (2006). Creative self-efficacy: Correlates in middle and secondary students. Creativity Research Journal, 18(4), 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R. A. (2007). Does creativity have a place in classroom discussions? Prospective teachers’ response preferences. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A., Mitchell, A. S., Mott, A., James, S., Cockayne, S., Gascoyne, S., & McDaid, C. (2020). An assessment of the extent to which the contents of PROSPERO records meet the systematic review protocol reporting items in PRISMA-P. F1000Research, 9, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, A., Byrne, P., & O’Kelly, M. (2020). A short instrument for measuring students’ confidence with ‘key skills’ (sicks): Development, validation, and initial results. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 37, 100700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. L. (1987). Metacognition, executive control, self-regulation, and other more mysterious mechanisms. In F. E. Weinert, & R. Kluwe (Eds.), Metacognition, motivation, and understanding (pp. 65–116). L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cécillon, F. X., Mermillod, M., Leys, C., Bastin, H., Lachaux, J. P., & Shankland, R. (2024). The reflective mind of the anxious in action: Metacognitive beliefs and maladaptive emotional regulation strategies constrain working memory efficiency. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(3), 505–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheruvalath, R., & Gaude, A. (2023). Managing problem behavior and the role of metacognitive skills. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 38(3), 1227–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheruvalath, R., & Gaude, A. R. (2024). Introducing a classroom-based intervention to regulate problem behaviours using metacognitive strategies. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39, 2383–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolan, L., Iucu, R., Nedelcu, A., Mironov, C., & Cartiș, A. (2021). Innovative pedagogies: Ways into the process of learning transformation. WP7: Teaching Excellence. Task Force Innovative Pedagogies. CIVIS. A European Civic University. [Google Scholar]

- Code, J. (2020). Agency for learning: Intention, motivation, self-efficacy, and self-regulation. Frontiers in Education, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E., Shealy, T., Grohs, J., & Godwin, A. (2020). Design thinking among first-year and senior engineering students: A cross-sectional, national study measuring perceived ability. Journal of Engineering Education, 109(1), 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, M., M’Bale, K., & Josyula, D. (2018). Multi-level metacognition for adaptive behavior. Biologically Inspired Cognitive Architectures, 26, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, A., Molcho, M., & Pickett, W. (2024). A focus on adolescent peer violence and bullying in Europe, central Asia and Canada (Vol. 2). WHO Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Cremin, T., Burnard, P., & Craft, A. (2006). Pedagogies of possibility thinking. International Journal of Thinking Skills and Creativity, 1(2), 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropley, A. J. (1992). More ways than one: Fostering creativity in the classroom. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, V. I. (1997). In search of the Wild Bohemian: Challenges in the identification of the creatively gifted. Roeper Review, 19(3), 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineen, R., & Niu, W. (2008). The effectiveness of western creative teaching methods in China: An action research project. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 2(1), 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K. A., & Schwartz, D. (1997). Social information processing mechanisms in aggressive behavior. In D. M. Stoff, J. Breiling, & J. D. Maser (Eds.), Handbook of antisocial behavior (pp. 171–180). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe, P. (2007). The bullying prevention pack: Steps to dealing with bullying in your school. An Leanbh Og: The OMEP Journal of Early Childhood Studies, 1(1), 233–257. [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe, P., & O’Sullivan, C. (2015). The bullying prevention pack: Fostering vocabulary and knowledge on the topic of bullying and prevention using role-play and discussion to reduce primary school bullying. Scenario: A Journal of Performative Teaching, Learning, Research, IX(1), 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durugbo, C., & Pawar, K. (2014). A unified model of the co-creation process. Expert Systems with Applications, 41(9), 4373–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwiningrum, S. I.-A., & Wahab, N. A. (2020). Creative teaching strategy to reduce bullying in schools. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 19(4), 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escortell, R., Aparisi, D., Martínez-Monteagudo, M. C., & Delgado, B. (2020). Personality traits and aggression as explanatory variables of cyberbullying in Spanish preadolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (Eds.). (2004). Bullying in American schools: A social-ecological perspective on prevention and intervention. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (Eds.). (2010). Bullying in North American schools. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, S. W., Owens, J. S., & Bunford, N. (2014). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 43(4), 527–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evgin, D., & Bayat, M. (2020). The effect of behavioral system model-based nursing intervention on adolescent bullying. Florence Nightingale Journal of Nursing, 28(1), 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A., Cachia, R., & Punie, Y. (2009). Innovation and creativity in education and training in the EU member states: Fostering creative learning and supporting innovative teaching. JRC Technical Note, 52374, 64. Publication of the European Community. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, A., Enciso, P., & Benveniste, M. (2023). Narrative creativity training: A new method for increasing resilience in elementary students. Journal of Creativity, 33(3), 2713–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokides, E. (2017). Using digital storytelling to inform students about bullying: Results of a pilot program. International Journal of Bias, Identity and Diversities in Education (IJBIDE), 2(1), 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füller, J., Hutter, K., & Faullant, R. (2011). Why co-creation experience matter? Creative experience and its impact on the quantity and quality of creative contributions. R&D Management, 41(3), 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, H., Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2021). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying perpetration and victimization: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 17(2), e1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genco, N., Holtta-Otto, K., & Seepersad, C. C. (2012). An experimental investigation of the innovation capabilities of undergraduate engineering students. Journal of Engineering Education, 101(1), 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, G., Marino, C., & Spada, M. M. (2019). The role of metacognitions and thinking styles in the negative outcomes of adolescents’ peer victimization. Violence and Victims, 34(5), 752–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombert, J.-L. (1990). Le développement métalinguistique. Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, J., Bradley, S. K., Donohoe, P., Queen, K., O’Shea, M., & Horgan, A. (2019). Bullying in schools: An evaluation of the use of drama in bullying prevention. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 14(3), 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1969). Three sides of the intellect. Psychological thinking. Progress. [Google Scholar]

- Haseeb, A. S. (2018). Higher education in the era of IR 4.0. New Straits Times. Available online: https://www.nst.com.my/education/2018/01/323591/higher-education-era-ir-40 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Hennessey, B. A. (2017). Intrinsic motivation and creativity in the classroom: Have we come full circle? In R. A. Beghetto, & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 227–264). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herodotou, C., Sharples, M., Gaved, M., Kukulska-Hulme, A., Rienties, B., Scanlon, E., & Whitelock, D. (2019). Innovative pedagogies of the future: An evidence-based selection. Frontiers in Education, 4, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J., Morrison, L., Mamolo, A., Laffier, J., & de Castell, S. (2019). Addressing bullying through critical making. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(1), 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymel, S., & Swearer, S. M. (2015). Four decades of research on school bullying: An introduction. American Psychologist, 70(4), 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyin, E. P. (2011). Psychology of creativity and talent. Publishing House Peter. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyin, E. P. (2014). Psychology of aggressive behavior: A textbook. Publishing House Peter. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen, J. E., & Graham, S. E. (2001). Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kassim, H. (2019, April 25–27). Strategizing learning experience through e-learning platforms to enhance creative potential and language performance. International Conference on Language Teaching and Learning Today, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four C model of creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanolainen, D., & Semenova, E. (2023). Self and others in school bullying and cyberbullying: Fine-tuning a new arts-based method to study sensitive topics. Qualitative Psychology, 10(1), 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. H. (2011). The creativity crisis: The decrease in creative thinking scores on the torrance tests of creative thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 23(4), 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komalasari, K. (2011). Pembelajaran kontekstual, konsep dan aplikasi, kualitatif, dan R&D. Refika Aditama. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, K. A., & Gerber, M. M. (1987). Effects of social metacognitive training for enhancing overt behavior in learning disabled and low-achieving delinquents. Exceptional Children, 54(3), 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H., & Portillo, M. (2022). Transferability of creative self-belief across domains: The differential effects of a creativity course for university students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 43, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, S. S., Waasdorp, T. E., Paskewich, B. S., Bevans, K. B., & Winston, F. K. (2020). The Free2B multi-media bullying prevention experience: An exemplar of scientific edutainment. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyngstad, M. B., Baraldsnes, D., & Gjærum, R. G. (2022). Process drama in anti-bullying intervention: A study of adolescents’ attitudes and initiatives. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 27(4), 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, X., Liu, J., & Xue, Z. (2022). Does bullying attitude matter in school bullying among adolescent students: Evidence from 34 OECD countries. Children, 9(7), 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maor, R. (2025). Teachers’ intentions to implement antibullying practices: The role of social dominance orientation and teaching for creativity. Psychology in the Schools, 62(3), 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M., Webb, L., Villares, E., & Brigman, G. (2015). Effect of participation in student success skills on prosocial and bullying behavior. Professional Counselor, 5(3), 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, G. E., & Bronnick, K. S. (2009). Creative self-efficacy: An intervention study. International Journal of Educational Research, 48(1), 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, L. T., Simcock, G., Schwenn, P., Beaudequin, D., Driver, C., Kannis-Dymand, L., Lagopoulos, J., & Hermens, D. F. (2022). Cyberbullying, metacognition, and quality of life: Preliminary findings from the Longitudinal Adolescent Brain Study (LABS). Discover Psychology, 2(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mevarech, Z. R., & Kramarski, B. (2014). Critical maths for innovative societies: The role of metacognitive pedagogies. Educational Research and Innovation. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, S., Klein, J. P., Lysaker, P. H., & Mehl, S. (2019). Metacognitive and cognitive-behavioral interventions for psychosis: New developments. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 21(3), 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacimiento Rodríguez, L., & Mora-Merchán, J. A. (2014). El uso de estrategias de afrontamiento y habilidades metacognitivas ante situaciones de bullying y cyberbullying. European Journal of Education & Psychology, 7(2), 121–129. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1293/129332645006.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Nelson, T. O., & Narens, L. (1990). Metamemory: A theoretical framework and new findings. In Psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 26, pp. 125–173). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parjanen, S., Hennala, L., & Konsti-Laakso, S. (2012). Brokerage functions in a virtual idea generation platform: Possibilities for collective creativity? Innovation, 14(3), 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A. F., Storbacka, K., & Frow, P. (2007). Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. (2002). The role of metacognitive knowledge in learning, teaching, and assessing. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P., & García, T. (1993). Intraindividual differences in students’ motivation and self-regulated learning. German Journal of Educational Psychology, 7(3), 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Plucker, J. A., Beghetto, R. A., & Dow, G. (2004). Why isn’t creativity more important to educational psychologists? Potential, pitfalls, and future directions in creativity research. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PP, N. (2008). Cognitions about cognitions: The theory of metacognition. Online Submission. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED502151.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Rizzi, V., Pigeon, C., Rony, F., & Fort-Talabard, A. (2020). Designing a creative storytelling workshop to build self-confidence and trust among adolescents. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 38, 100704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roser, T., Samson, A., Humphreys, P., Cruz-Valdivieso, E., Humphreys, P., & Cruz-Valdivieso, E. (2009). Co-creation: New pathways to value [White paper]. Promise/LSE Enterprise. [Google Scholar]

- Royston, R., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2019). Creative self-efficacy as a mediator between creative mindsets and creative problem-solving. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 53(4), 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagone, E., & De Caroli, M. E. (2016). “Yes …I can”: Psychological resilience and self-efficacy in adolescents. INFAD Revista de Psicología. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1), 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagone, E., De Caroli, M. E., Falanga, R., & Indiana, M. L. (2020). Resilience and perceived self-efficacy in life skills from early to late adolescence. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saibon, J., Leong, A. C. H., & Razak, M. Z. A. (2017). Enhancing knowledge of bullying behavior through creative pedagogy among students. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 14, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R. K. (2015). A call to action: The challenges of creative teaching and learning. Teachers College Record, 117(10), 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacter, J., Thum, Y. M., & Zifkin, D. (2006). How much does creative teaching enhance elementary school students’ achievement? The Journal of Creative Behavior, 40(1), 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrage, M. (1995). Customer relations. Harvard Business Review, 73(4), 154–156. [Google Scholar]

- Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19(4), 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C. L. (1999). Teachers’ biases toward creative children. Creativity Research Journal, 12(4), 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H. A., Lee, E. A., & Kim, K. H. (2005). Korean science teachers’ understandings of creativity in gifted education. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 16, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. (2011). Cultivating innovative learning and teaching cultures: A question of garden design. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(4), 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, E., Hoekstra, R., Fiore, S., & McCauley, P. (2017). An investigation of the state of creativity and critical thinking in engineering undergraduates. Creative Education, 8(9), 1495–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, E. R., Anyan, F., Hjemdal, O., Nordahl, H. M., & Nordahl, H. (2024). Dysfunctional attitudes versus metacognitive beliefs as within-person predictors of depressive symptoms over time. Behavior Therapy, 55(4), 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmidt, K. J., Rakowiecka, B., & Okraszewski, K. (1996). Porzadek i Przygoda. Lekcje tworczosci [Order and Adventure. Creativity lessons]. Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne. [Google Scholar]

- Thingbak, A., Capobianco, L. P., Wells, A., & O’Toole, M. S. (2024). Relationships between metacognitive beliefs and anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 361, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, E. P. (1977). Creativity in the classroom: What research says to the teacher. National Education Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Broekhoven, K., Belfi, B., Hocking, I., & van der Velden, R. (2020). Fostering university students’ idea generation and idea evaluation skills with a cognitive-based creativity training. Creativity. Theories–Research-Applications, 7(2), 284–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H. M., Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., Bullis, M., Sprague, J. R., Bricker, D., & Kaufman, M. J. (1996). Integrated approaches to preventing antisocial behavior patterns among school-age children and youth. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 4(4), 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H. M., & Shinn, M. R. (2002). Structuring school-based interventions to achieve integrated primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention goals for safe and effective schools. In M. R. Shinn, H. M. Walker, & G. Stoner (Eds.), Interventions for academic and behavior problems II: Preventive and remedial approaches (pp. 1–25). National Association of School Psychologists. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, D., & Purdy, N. (2019). Cartoons as visual representations of the development of primary school children’s understanding of bullying behaviours. Pastoral Care in Education, 37(3), 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westby, E. L., & Dawson, V. (1995). Creativity: Asset or burden in the classroom? Creativity Research Journal, 8(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, E., & Twigg, E. (2017). Developing creativity in early childhood studies students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 23, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Moylan, A. R. (2009). Self-regulation: Where metacognition and motivation intersect. In D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Handbook of metacognition in education (pp. 299–315). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, E. (2018). The 4 C’s of learning in a connected classroom. EdTech Magazine. Available online: https://edtechmagazine.com/k12/article/2018/07/4-cs-learning-connected-classroom (accessed on 6 April 2025).

| Authors | Themes | Participants (N) | Methods, Techniques | Means of Learning | Skills | Methods of Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Evgin and Bayat (2020) | Bullying phenomenon Awareness and recognition of emotions Bullying identification Developing empathy Improving problem-solving skills Developing social skills Emotional self-regulation Increasing awareness of bullying | N = 72 students, 7th grade (12–13 years) | Role playing Improvisation Brainstorming Photographic Memory technique | Dull image Behavior list Information cards Role writing | Problem solving Empathy Awareness of bullying Social and emotional skills Self-efficacy | Traditional Peer Bullying Scale (TPBS) Inventory for Children (PSIC) Problem Solving Empathy Index for Children Observation Evaluation of the content of activities Data collection form Tracking: self-reflective |

| 2. Goodwin et al. (2019) | Understanding bullying The role of observation Developing empathy Preventing intervention in bullying | N = 50 students (12–15 years) | Viewed a one-act scripted performance based on a schoolyard bullying incident Interactive slideshow presentation Involving students in proposing prevention strategies | Interactive theater Interactive presentations Worksheet Slides-visual resources (diapositive) | Empathy Problem-solving Awareness of bullying social and emotional skills Teamworking | Observation Group interview to explore students’ experiences of the interactive theater-based workshop Students’ reports |

| 3. Fokides (2017) | Digital Storytelling | N = 24 students 4th grade (9–10 years) | Digital Storytelling Presentation of the stories Collectively developed story Development of the final story Short essays | Story maker Software tool for the development of their digital stories Student scenario Students’ story | Creative thinking Collaborative Communicative Flexibility Taking the initiative and leadership Problem-solving skills Digital skills | Evaluation of the digital stories Evaluation of students’ essays |

| 4. Hughes et al. (2019) | Hands-on creative activities and the use of digital technologies by utilizing maker pedagogy (STEAM) | N = 2 students 6th grade (11–12 years) | Digital design Photography/videography technique Maker digital poster E-textile | App PicCollage for digital poster-making App Word Swag for button-making iPad Air for photography/videography Piktochart to create infographics based on bullying statistics E-textile components to create a wearable Circuits to “highlight” and spread messages of positivity | Digital literacy Ability to troubleshoot Problem-solving Creative and expressive skills through digital design and art Critical thinking | Assessment of creativity Technical skills and understanding of bullying based on digital and physical works created by students Observation |

| 5. Warwick and Purdy (2019) | Cartoons with many common forms of bullying and cyberbullying | N = 90 children (6–7 years and 10–11 years) | Cartooning Focus group Definition of bullying Illustration with stick figures | 16 new cartoons were created (covering many common forms of bullying and cyberbullying) | Awareness of bullying Critical reflection Understanding bullying behaviors | Focus group Evaluation of cartoons and definitions |

| 6. Mariani et al. (2015) | Student Success Skills classroom Guidance program | N = 336 (age 10) | Classroom lessons Booster sessions using “tell–show–do” format | Prosocial Behaviors Bullying behaviors Engagement in school success skills Perceptions of classroom climate | The comparison between the treatment group and the comparison group, quantitative evaluation | |

| 7. Khanolainen and Semenova (2023) | Artmaking and creative engagement components of arts-based research | N = 35 students (13–16 years) | Story completion Graphic elicitation | Set of six graphic vignettes: traditional vignettes, narrative inquiry, and graphic elicitation | Students’ perceptions and experiences of bullying and cyberbullying | Exploratory and diagnostic study Follow-up interviews In-depth interviews Story completion Sensitive research |

| 8. Saibon et al. (2017) | Creative and fun pedagogy approach | N = 234 (14–16 years) | Sculpture performance Storytelling Rhyme and dance Mannequin/puppet act Dialog and spontaneous role play, Videos Coloring Matching and making paper Collage activities Game mode | Creativity components: Fluency Flexibility Originality Elaboration Knowledge of bullying among students | Quantitative method with support Qualitative approaches utilizing quasi-experiments design. It was used The Student Bullying Knowledge Level (TPBL) questionnaire Pre-test and post-test, which 25 items that examine student knowledge about bullying behaviors and structured interviews were also conducted on seven students | |

| 9. Leff et al. (2020) | Peer bullying fact norms supporting bullying Prosocial behavior Power of the observer Problem-solving steps Empathy Perspective taking | N = 1990 students | Interactive experience/learning video inspiration 3D movie Audio experience | Handheld devices | Knowledge of bullying facts, norms supporting bullying vs. Prosocial behavior, attitude about role of the observer, knowledge of social problem-solving steps, understanding empathy perspective taking | Student self-reported Data pre-, post-, and during the interactive quiz show, 3 pilot studies totaling 1990 students 13 pre- and post-assembly questions |

| 10. Lyngstad et al. (2022) | Role play with themes: Meeting, Voices in the head, Hot seats, Image theater, ‘Letters’, A meeting with teacher-in-role, the exercise deals with bullying out of role | N = 95 students, 16 years | Drama workshops Role play | Understanding of the complexity within the situation, to deal with being themselves and in role, skills of observing others in different roles Able to experience the bullying from different perspectives (teachers, students, parents). Skills to cope with their insecurity or to show resistance, being more active, and taking initiative, able to show their empathy and care | Observation of the process Drama, The assessment choices are called the Four Corners, four alternative responses To every statement, one response placed in each corner Short questionnaire after the drama workshop | |

| 11. Donohoe and O’Sullivan (2015) | The Bullying Prevention Pack (BPP) | N = 231 male primary school pupils N = 13 teachers -junior infants to first class (5–7 years) and the senior (8–12 years) | Bullying role play, Onlooker role play, the strategy of using the popular student instead of the defender -role play-Defending with Confidence, Confident Behaviors Exercise, Group discussions | Contract to prevent bullying in their school | enhanced learner knowledge of the topic of bullying and the use of role play, and the development of vocabulary specific to bullying | Monthly check-ups by the class teacher, follow-up sessions |

| Study | Type of Study | Methods | Outcomes | Type of Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Evgin and Bayat (2020) | Quantitative quasi-experimental study with pre-post test and control group | Observation Evaluation of the content of activities Email tracking Data collection | Problem-solving skills Empathy skills Awareness of bullying skills Social and emotional skills Self-efficacy skills | Understanding bullying Decreasing bullying |

| 2. Goodwin et al. (2019) | Qualitative | Observation Group interview | Empathy skills Problem-solving skills Awareness of bullying skills Social and emotional skills Teamworking skills | Understanding bullying |

| 3. Fokides (2017) | Qualitative pilot study | Creative thinking Collaborative skills Communicative skills Flexibility Taking initiatives and leadership Problem-solving skills digital skills | Understanding bullying | |

| 4. Hughes et al. (2019) | Qualitative case study that focused on two students | Observation Assessment of creativity Technical skills and understanding of bullying based on digital and physical works created by students | Digital literacy skills Ability to troubleshoot Problem-solving skills Creative and expressive skills through digital design and art Critical thinking | Understanding bullying |

| 5. Warwick and Purdy (2019) | Qualitative | Focus group Evaluation of cartoons and definitions | Awareness of bullying skills Critical reflection Understanding bullying behaviors | Understanding bullying |

| 6. Mariani et al. (2015) | Quantitative | The comparison between the treatment group and comparison group Quantitative evaluation | Prosocial behaviors Bullying behaviors engagement in school success skills Perceptions of classroom climate | Understanding bullying Decreasing bullying |

| 7. Khanolainen and Semenova (2023) | Qualitative | Exploratory and diagnostic study Follow-up interviews Individual discussions and interview Story completion, sensitive research | Students’ perceptions and experiences of bullying and cyberbullying | Understanding bullying |

| 8. Saibon et al. (2017) | Mixed mostly quantitative and qualitative approaches (7 interviews) | Quantitative method with the support of qualitative approaches utilizing quasi-experimental design | Creativity components: fluency, flexibility, originality, elaboration Knowledge of bullying among students | Understanding bullying |

| 9. Leff et al. (2020) | Mixed-quantitative Qualitative-focus group | 3 pilot studies totaling 1990 students 13 pre- and post-assembly questions | Immediate outcomes: knowledge of bullying facts, norms supporting bullying vs. prosocial behavior, attitude about the role of the observer, knowledge of social problem-solving steps, understanding empathy, and perspective taking | Understanding bullying |

| 10. Lyngstad et al. (2022) | Qualitative case study—observations and open-ended questions | Observation of the process drama | Understanding the complexity within the situation, to deal with being themselves and in role, skills of observing others in different roles Able to experience bullying from different perspectives (teachers, students, parents), skills to cope with their insecurity or to show resistance, being more active, and taking initiative, able to show their empathy and care | Understanding bullying |

| 11. Donohoe and O’Sullivan (2015) | Mixed | Monthly check-ups by the class teacher Follow-up sessions | Enhanced learner knowledge of the topic of bullying and the use of role play, the development of vocabulary specific to bullying | Understanding bullying |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diac, G.; Grădinariu, T.; Maor, R.; Rogoz, N.; Vechiu, A.-P. Creative and Metacognitive Strategies in Anti-Bullying Programs: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111457

Diac G, Grădinariu T, Maor R, Rogoz N, Vechiu A-P. Creative and Metacognitive Strategies in Anti-Bullying Programs: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111457

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiac, Georgeta, Tudorița Grădinariu, Rotem Maor, Nicoleta Rogoz, and Adina-Petronela Vechiu. 2025. "Creative and Metacognitive Strategies in Anti-Bullying Programs: A Systematic Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111457

APA StyleDiac, G., Grădinariu, T., Maor, R., Rogoz, N., & Vechiu, A.-P. (2025). Creative and Metacognitive Strategies in Anti-Bullying Programs: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111457