Reducing Extreme Commuting by Built Environmental Factors: Insights from Spatial Heterogeneity and Nonlinear Effect

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Measurement of Extreme Commuting

2.2. Factors Influencing Commuting Burden

2.3. Methods of Quantifying the Relationship Between the Built Environment and Commuting Demand

3. Data Preparation and Variables

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Study Area Classification

3.3. Threshold Setting for Extreme Commuting

3.4. The Explanatory Definitions and Descriptive Statistics

4. Methods

4.1. Extreme Commuting Index

4.2. GWRF Model

4.3. SHAP Model

5. Results

5.1. Distribution of Index

5.2. Model Performance

5.3. Spatial Distribution of Relative Importance

5.3.1. Overall Analysis

5.3.2. Generation Scenario

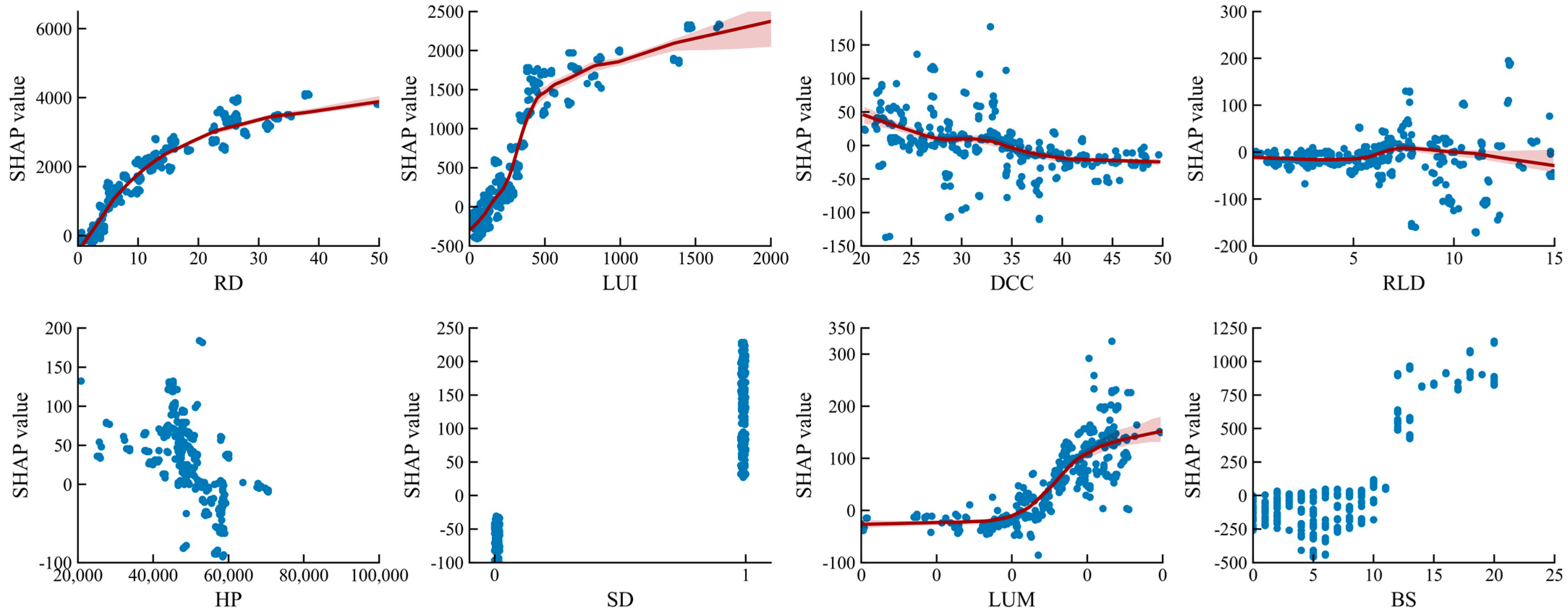

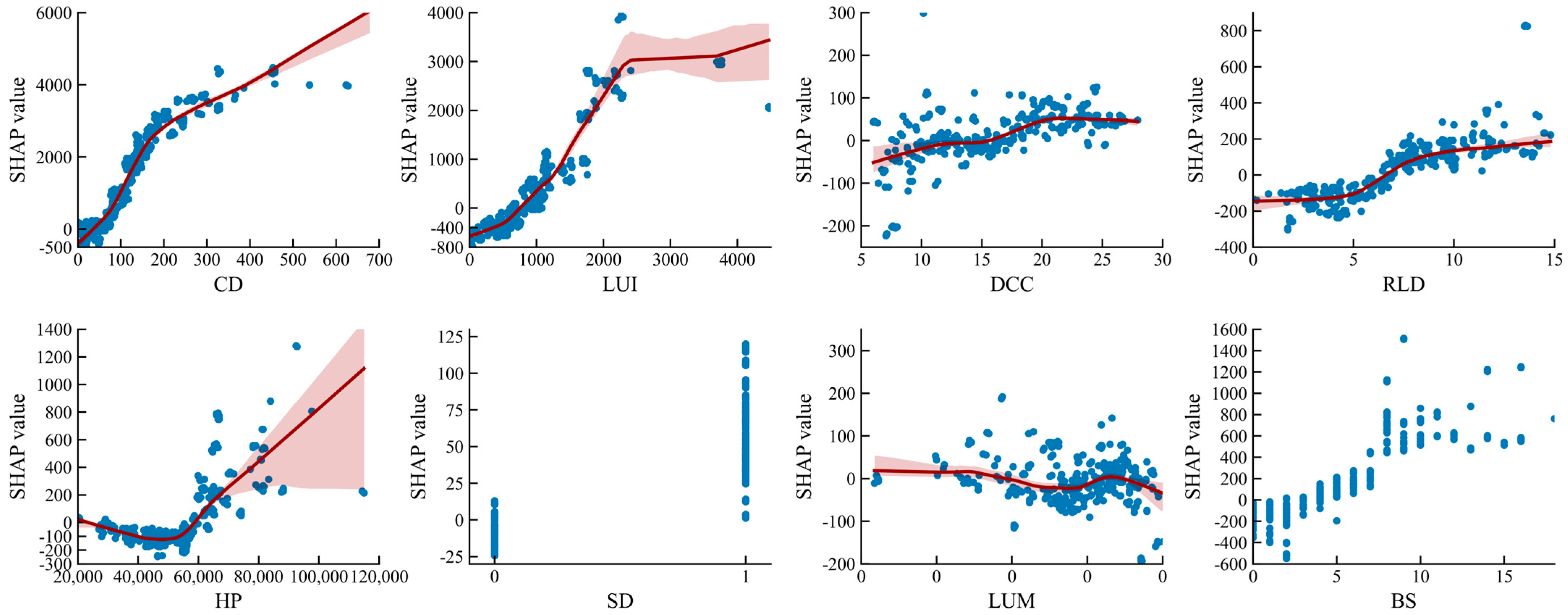

5.3.3. Attraction Scenario

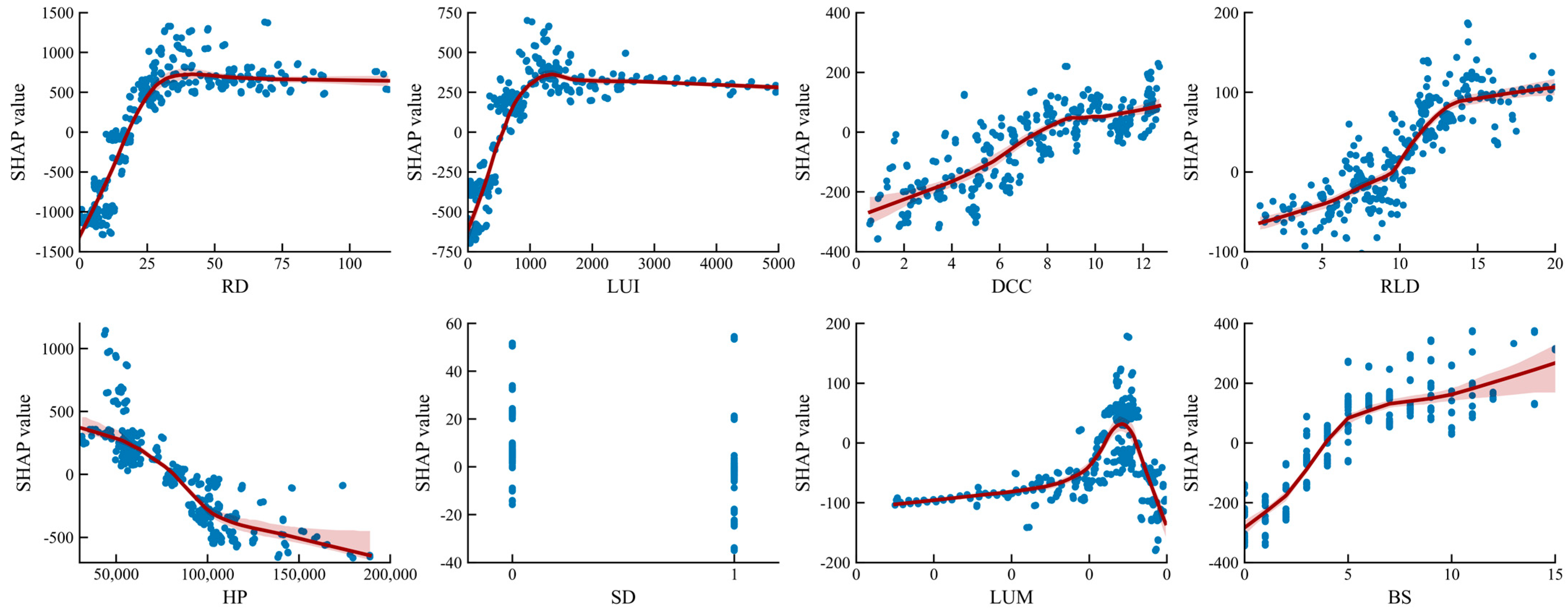

5.4. Nonlinear Associations Among Different Regions

6. Discussion

6.1. Comparison with Related Studies

6.2. Policy Implication on Reducing Extreme Commuting

- (1)

- Regional differentiation suggestions based on important variables

- (2)

- Targeted local strategies considering nonlinear associations and thresholds

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Vincent-Geslin, S.; Ravalet, E. Determinants of extreme commuting. Evidence from Brussels, Geneva and Lyon. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 54, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Palm, M.; Tiznado-Aitken, I.; Farber, S. Inequalities of extreme commuting across Canada. Travel Behav. Soc. 2022, 29, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Academy of Urban Planning and Design (CAUPD). 2024 Commuting Monitoring Report for Major Cities in China, China Academy of Urban Planning and Design. 2024. Available online: https://www.caupd.com/index.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Marion, B.; Horner, M.W. Comparison of socioeconomic and demographic profiles of extreme commuters in several US metropolitan statistical areas. Transp. Res. Rec. 2007, 2013, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, T.; Coombes, M.; Brown, D.L. Migration and longer-distance commuting in rural England. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gately, C.K.; Hutyra, L.R.; Sue Wing, I. Cities, traffic, and CO2: A multidecadal assessment of trends, drivers, and scaling relationships. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 4999–5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; De Vos, J.; Ma, L. Analysing the association of dissonance between actual and ideal commute time and commute satisfaction. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 132, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Nadal, J.I.; Molina, J.A. Daily feelings of US workers and commuting time. J. Transp. Health 2019, 12, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandow, E.; Westerlund, O.; Lindgren, U. Is your commute killing you? On the mortality risks of long-distance commuting. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2014, 46, 1496–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Cao, X.; Yu, B.; Ju, Y. Non-linear associations between zonal built environment attributes and transit commuting mode choice accounting for spatial heterogeneity. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 148, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Shao, C. Revisiting commuting, built environment and happiness: New evidence on a nonlinear relationship. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 100, 103043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jia, P.; Feng, T.; Li, H.; Kuang, H. Spatiotemporal analysis of built environment restrained traffic carbon emissions and policy implications. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 121, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, E.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y. Spatiotemporal influence of built environment on intercity commuting trips considering nonlinear effects. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 114, 103744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.K.; Saphores, J.D.M. Why do they live so far from work? Determinants of long-distance commuting in California. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 80, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandow, E.; Westin, K. The persevering commuter–Duration of long-distance commuting. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2010, 44, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhai, W.; Steiner, R.L.; He, Z. Exploring extreme commuting and its relationship to land use and socioeconomics in the central Puget Sound. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 88, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüger, H.; Stawarz, N.; Skora, T.; Wiernik, B.M. Longitudinal relationship between long-distance commuting willingness and behavior: Evidence from European data. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 77, 101667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, L. Non-linear relationships between built environment and commuting duration of migrants and locals. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 106, 103517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoh, H.; Tang, Z. Determinants of normal and extreme commute distance in a sprawled midsize Canadian city: Evidence from Windsor, Canada. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 25, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Chai, Y. Early birds, night owls, and tireless/recurring itinerants: An exploratory analysis of extreme transit behaviors in Beijing, China. Habitat Int. 2016, 57, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.H.; Hipp, J.R. Do employment centers matter? Consequences for commuting distance in the Los Angeles region, 2002–2019. Cities 2024, 145, 104669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Geertman, S.; Hooimeijer, P.; Lin, Y.; Yang, H.; Yang, L. Interaction ors on long-distance commuting after disentangling residential self-selection: An empirical study in Xiamen, China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 105, 103481. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Z.; An, R.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Luo, M. Exploring non-linear and spatially non-stationary relationships between commuting burden and built environment correlates. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 104, 103413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cao, M.; Yang, T.; Ma, L.; Wu, M.; Cheng, L.; Ye, R. Inequalities in the commuting burden: Institutional constraints and job-housing relationships in Tianjin, China. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 42, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderrama, M. Extreme Commuting in Southern California: Prevalence, Patterns, and Equity. Ph.D. Thesis, California State Polytechnic University, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Mishra, S.; Lu, G.; Yang, J.; Liu, C. Influences of built environment characteristics and individual factors on commuting distance: A multilevel mixture hazard modeling approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 51, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman, D.; Young, O.; Jing, Y.; Bramble, B.; Bu, M.; Chen, C.; Furst, K.; Hu, T.; Li, Y.; Logan, K.; et al. Environmental governance in China: Interactions between the state and “nonstate actors”. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 220, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buliung, R.N.; Kanaroglou, P.S. Commute minimization in the Greater Toronto Area: Applying a modified excess commute. J. Transp. Geogr. 2002, 10, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limtanakool, N.; Dijst, M.; Schwanen, T. On the participation in medium-and long-distance travel: A decomposition analysis for the UK and the Netherlands. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2006, 97, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, R.; Páez, A. Determinants of distance traveled with a focus on the elderly: A multilevel analysis in the Hamilton CMA, Canada. J. Transp. Geogr. 2009, 17, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaugh, K.; Miranda-Moreno, L.F.; El-Geneidy, A.M. The effect of neighbourhood characteristics, accessibility, home–work location, and demographics on commuting distances. Transportation 2010, 37, 627–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P. The determinants of the commuting burden of low-income workers: Evidence from Beijing. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2015, 47, 1736–1755. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, J.; Lee, S.; Ko, J. Unraveling the impact of travel time, cost, and transit burdens on commute mode choice for different income and age groups. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 141, 147–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cassel, S.H.; Macuchova, Z.; Rudholm, N.; Rydell, A. Willingness to commute long distance among job seekers in Dalarna, Sweden. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axisa, J.J.; Scott, D.M.; Newbold, K.B. Factors influencing commute distance: A case study of Toronto’s commuter shed. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; He, S.; Zhao, P. Revisiting inequalities in the commuting burden: Institutional constraints and job-housing relationships in Beijing. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 71, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Boisjoly, G.; El-Geneidy, A.; Levinson, D. Accessibility and the journey to work through the lens of equity. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 74, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Roy, U.K. Taxonomy of urban mixed land use planning. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Allan, A.; Cui, J. The influence of jobs–housing balance and socio-economic characteristics on commuting in a polycentric city: New evidence from China. Environ. Urban. ASIA 2016, 7, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Ho, S.N.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, X. Built environment, commuting behaviour and job accessibility in a rail-based dense urban context. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 87, 102438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P. The impact of the built environment on individual workers’ commuting behavior in Beijing. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2013, 7, 389–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Xiao, L. Non-linear associations between built environment and active travel for working and shopping: An extreme gradient boosting approach. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 92, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Tang, G.; Shen, H.; Rasouli, S. Spatial heterogeneity in the nonlinear impact of built environment on commuting time of active users: A gradient boosting regression tree approach. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 2023, 6217672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georganos, S.; Grippa, T.; Niang Gadiaga, A.; Linard, C.; Lennert, M.; Vanhuysse, S.; Mboga, N.; Wolff, E.; Kalogirou, S. Geographical random forests: A spatial extension of the random forest algorithm to address spatial heterogeneity in remote sensing and population modelling. Geocarto Int. 2021, 36, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Ye, Z.; Wu, H. Nonlinear effects of built environment on intermodal transit trips considering spatial heterogeneity. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 90, 102677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Lo, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Q. Nonlinear and synergistic effects of TOD on urban vibrancy: Applying local explanations for gradient boosting decision tree. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 72, 103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fan, P.; Yue, W. Environmental factors for outdoor jogging in Beijing: Insights from using explainable spatial machine learning and massive trajectory data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 243, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yan, X.; Wang, W.; Titheridge, H.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y. Characterizing the polycentric spatial structure of Beijing Metropolitan Region using carpooling big data. Cities 2021, 109, 103040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidu Maps. 2019 China Urban Transportation Report, Baidu Maps. 2020. Available online: https://jiaotong.baidu.com/cms/reports/traffic/2023/index.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Huo, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Xue, D. Spatio-temporal analysis on online designated driving based on empirical data. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 183, 104047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Xie, B.; Chan, E.H. Exploring impacts of the built environment on transit travel: Distance, time and mode choice, for urban villages in Shenzhen, China. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 132, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhou, L.; Liu, C.; Guo, Y.; Sun, S.; Guo, L.; Sun, X. Reducing automobile commuting in inner-city and suburban: Integrating land-use and management intervention. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 136, 104460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Explanatory Variables | Description | Mean | Min | Max | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Built-Environment Factors | |||||

| RD | Residential land use density in each grid (/km2) | 3.32 | 0 | 150.62 | 97.63 |

| CD | Company land use density in each grid (/km2) | 23.72 | 0 | 1953.55 | 6807.76 |

| LUM | Land use diversity index in each grid | 0.39 | 0 | 0.88 | 0.08 |

| LUI | Land use intensity index in each grid (/km2) | 125.39 | 0 | 5404.97 | 137,290 |

| BA | Building coverage area in each grid (%) | 88,593.4 | 0 | 463,784 | |

| HP | Average house prices in each grid (CNY) | 53,158.8 | 10,558 | 195,481 | |

| SD | Whether they have the key primary and secondary schools in each grid | 0.02 | 0 | 1 | 0.02 |

| DCC | Distance to the core center (km) | 38.79 | 0.51 | 128.92 | 570.63 |

| DNS | Distance to the nearest subcenter (km) | 19.49 | 0.11 | 97.31 | 274.69 |

| BS | Number of bus stops in each grid | 2.07 | 0 | 42 | 9.49 |

| RLD | Road length density in each grid (km) | 4.59 | 0 | 21.93 | 12.07 |

| ST | Number of subway stations in each grid | 0.08 | 0 | 6 | 0.13 |

| Demographic Factors | |||||

| YC | Percentage of commuters between the ages of 25 and 34 in each grid (%) | 0.36 | 0 | 1 | 0.02 |

| MC | Percentage of male workers in the total number of workers in each grid (%) | 0.62 | 0 | 1 | 0.03 |

| CO | Percentage of commuters owning private cars (%) | 0.26 | 0 | 1 | 0.02 |

| HE | Percentage of population with bachelor’s degree or higher (%) | 0.13 | 0 | 1 | 0.02 |

| IS | Median income score in each grid | 2.79 | 1 | 5 | 0.26 |

| CS | Median consumption score in each grid | 2.17 | 1 | 3 | 0.08 |

| Explanatory Variables | Description | Mean | Min | Max | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECS_A | Extreme commuting severity in each attraction grid | 849.9 | 0 | 50,337.8 | |

| ESC_G | Extreme commuting severity in each generation grid | 637.66 | 0 | 30,919.2 |

| Scenario | Moran’s I | p | Z |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generation grid (O) | 0.210 | 0.000 | 91.783 |

| Attraction grid (D) | 0.478 | 0.000 | 28.220 |

| Scenario | Coefficient | OLS | RF | GWR | GWRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation | R2 | 0.41 | 0.65 | 0.49 | 0.68 |

| RMSE | 300.14 | 271.23 | 197.48 | 186.54 | |

| MAE | 204.23 | 192.73 | 131.21 | 129.87 | |

| CVRMSE | 0.421 | 0.387 | 0.281 | 0.266 | |

| NMAE | 0.251 | 0.245 | 0.153 | 0.149 | |

| Attraction | R2 | 0.39 | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.71 |

| RMSE | 494.25 | 413.44 | 486.13 | 427.61 | |

| MAE | 326.70 | 351.35 | 301.27 | 292.72 | |

| CVRMSE | 0.448 | 0.358 | 0.439 | 0.374 | |

| NMAE | 0.362 | 0.390 | 0.234 | 0.224 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, F.; Liu, X.; Yan, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Ma, L. Reducing Extreme Commuting by Built Environmental Factors: Insights from Spatial Heterogeneity and Nonlinear Effect. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120487

Li F, Liu X, Yan X, Liu Z, Zhao X, Ma L. Reducing Extreme Commuting by Built Environmental Factors: Insights from Spatial Heterogeneity and Nonlinear Effect. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(12):487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120487

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Fengxiao, Xiaobing Liu, Xuedong Yan, Zile Liu, Xuefei Zhao, and Lu Ma. 2025. "Reducing Extreme Commuting by Built Environmental Factors: Insights from Spatial Heterogeneity and Nonlinear Effect" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 12: 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120487

APA StyleLi, F., Liu, X., Yan, X., Liu, Z., Zhao, X., & Ma, L. (2025). Reducing Extreme Commuting by Built Environmental Factors: Insights from Spatial Heterogeneity and Nonlinear Effect. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(12), 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120487