Abstract

Spatial distribution similarity analysis has extensive application value in multiple domains including geographic information science, urban planning, and engineering site selection. However, traditional regional similarity analysis methods face three key challenges: high sensitivity to directional changes, limitations in feature interpretability, and insufficient adaptability to multi-type data. Addressing these issues, this paper proposes a rotation-invariant spatial distribution similarity analysis method based on ring vectors. This method comprises three stages. First, the traversal starting point of the ring vector is dynamically selected based on the maximum value point of the regional feature matrix. Next, concentric ring features are extracted according to this starting point to achieve multi-scale characterization. Finally, the bidirectional weighted comprehensive distance of ring vectors between regions is calculated to measure the similarity between regions. Three experimental sets verified the method’s effectiveness in terrain matching, engineering site selection, and urban functional area identification. These results confirm its rotational invariance, feature interpretability, and adaptability to multi-type data. This research provides a new technical approach for spatial distribution similarity analysis, with significant theoretical and practical implications for geographic information science, urban planning, and engineering site selection.

1. Introduction

Spatial data analysis has emerged as a fundamental research domain within geographic information science, remote sensing, and urban planning, garnering significant attention from both academic and industrial communities in recent years [1,2,3]. The rapid advancement of remote sensing technologies has revolutionized data acquisition processes, enabling unprecedented access to high-resolution satellite imagery (e.g., WorldView-4 with 0.31 m resolution, GF-2 with 0.8m resolution), precise digital elevation models (DEM) (e.g., SRTM90m, TanDEM-X12m), and fine-grained points of interest (POI) datasets [4,5]. These multi-type spatial datasets provide a rich foundation for regional analysis. However, they also present novel challenges for data processing and pattern recognition methodologies [6].

Within the diverse landscape of spatial analysis applications, the identification of regions exhibiting similar spatial distribution patterns represents a fundamental task with extensive practical utility. In urban planning contexts, planners frequently seek communities with comparable functional characteristics to optimize the distribution of public service facilities and resource allocation [7]. Environmental scientists routinely identify ecological habitats with the corresponding geographical features to forecast species distribution and migration patterns [8]. Disaster management frameworks benefit from analyzing terrain similarities between historical disaster sites and potential risk zones to formulate more effective evacuation protocols [9]. Agricultural researchers compare soil distribution patterns across various regions to determine optimal locations for crop transplantation and yield enhancement [10]. Healthcare systems optimize the placement of medical facilities by identifying areas exhibiting similar population density distributions [11].

These multifaceted applications underscore the critical importance of developing robust spatial pattern similarity analysis methodologies; however, existing regional similarity analysis methods still face several key challenges in practical applications:

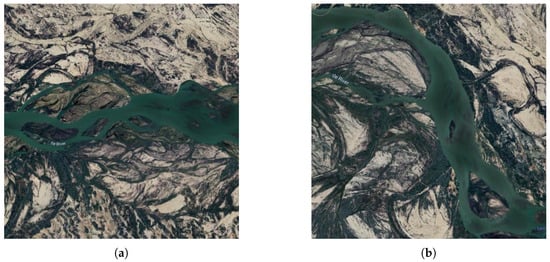

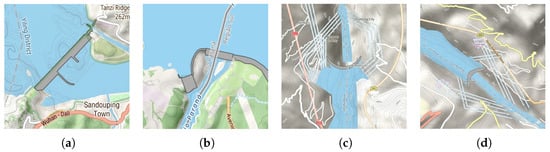

- Directional Sensitivity Issues. Traditional grid or pixel-based comparison methods, such as template matching algorithms, exhibit high sensitivity to rotation. The accuracy of these methods decreases significantly when similar regions undergo rotational changes [12,13]. When identical geographical features are present in different orientations (e.g., north-south versus east-west river valleys, as shown in Figure 1), conventional methods struggle to identify their intrinsic similarities. This issue is particularly pronounced in remote sensing data processing, as the orientation of topographical features is often determined by natural evolutionary processes. Functionally similar regions may exhibit significant directional differences, exemplified by the contrasting ridge orientations of the Himalayan and Alpine mountain ranges.

Figure 1. Remote Sensing Imagery of Ili River Valley in Xinjiang, China with Different Orientations. (a) East-West Oriented Remote Sensing Imagery of Ili River Valley. (b) North-South Oriented Remote Sensing Imagery of Ili River Valley.

Figure 1. Remote Sensing Imagery of Ili River Valley in Xinjiang, China with Different Orientations. (a) East-West Oriented Remote Sensing Imagery of Ili River Valley. (b) North-South Oriented Remote Sensing Imagery of Ili River Valley. - Feature Interpretability Limitations. Although current deep learning-based spatial pattern recognition methods have enhanced feature representation capabilities, their “black box” nature results in similarity measurements lacking geographic semantic interpretations [14]. For instance, Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) classify output images without providing further explanations of scene-corresponding results [15,16]. Consequently, developing techniques that make black-box processes more transparent and comprehensible is crucial in the remote sensing domain. In medical resource allocation scenarios, similarity models that merely output probability values without revealing the spatial association mechanisms between population density distribution and healthcare needs significantly constrain the scientific validity of policy formulation.

- Multi-type Data Adaptation Challenges. Existing methods are predominantly tailored to specific data types, limiting their applicability across diverse spatial datasets [17]. For instance, methods optimized for POI data may fail to perform effectively on road network data or terrain elevation models, and vice versa. This specialization restricts their utility in scenarios where practitioners need to analyze different types of spatial information using a unified analytical framework. Furthermore, the lack of methodological versatility complicates comparative analyses across heterogeneous data sources (such as comparing distribution patterns between satellite imagery and point-based datasets), thereby limiting applications that require consistent similarity assessment across multiple spatial data modalities.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a novel rotation-invariant spatial distribution similarity analysis method based on ring vectors.

The proposed approach overcomes the sensitivity limitations of traditional methods under rotational transformations by incorporating three core components: a dynamic starting point selection mechanism, a multi-layer ring vector representation, and a bidirectional matching strategy. These innovations maintain feature interpretability while ensuring adaptability to multi-type data. The principal contributions of this paper are:

- Development of a dynamic starting point selection mechanism that identifies the maximum value coordinates within the feature matrix to dynamically determine the starting point for ring vector traversal, thereby significantly mitigating the effects of rotation on similarity analysis.

- Creation of a multi-layer ring vector representation framework that extracts concentric ring vectors from the center outward, establishing a multi-scale feature representation that enhances algorithmic robustness against scale variations.

- Implementation of a bidirectional matching mechanism that generates complementary feature representations through both clockwise and counterclockwise traversal methods, substantially improving the algorithm’s capacity to recognize mirror-symmetric or inversely rotated distributions.

The comprehensive advantages of our proposed methodology are manifested in: (1) robust invariance to rotational transformations; (2) intuitive and interpretable feature representations that facilitate decision-making processes in practical applications; and (3) versatility across diverse spatial data types, including Digital Elevation Models (DEM), remote sensing imagery, Points of Interest (POI) distributions, and other spatial datasets, enabling broad application potential.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature, examining the evolutionary trajectory of regional feature representation and similarity measurement methodologies; Section 3 elucidates fundamental definitions and concepts, including spatial grid representation, coordinate transformation, and essential ring vector principles; Section 4 presents a detailed exposition of the proposed methodology and algorithm, encompassing ring vector extraction procedures, similarity calculation techniques, and efficient search strategies; Section 5 comprehensively validates the algorithm’s efficacy through three distinct experimental applications (dam site terrain analysis, radio telescope site evaluation, and urban functional area identification); finally, Section 6 summarizes the research contributions and delineates directions for future investigation.

2. Related Work

2.1. Regional Feature Expression

The effective representation of regional spatial characteristics forms the cornerstone of geographic pattern recognition and similarity analysis. Over the past decade, the evolution of feature expression methodologies has progressed from simple pixel-based descriptors to sophisticated deep learning architectures, each attempting to capture the intrinsic properties of spatial distributions while addressing challenges such as scale variance, rotational sensitivity, and computational efficiency.

Traditional Feature Transformation Approaches leverage mathematical transformations to derive invariant representations from spatial data. Peng et al. [18] employed the Fourier-Mellin transform to extract rotation-invariant spectral features, exploiting the property that Fourier magnitude remains unchanged under rotation. Lu and Yang [19] applied Zernike moments for image feature extraction, utilizing the orthogonality of moment functions to achieve rotational invariance. However, these frequency-domain methods frequently sacrifice spatial locality information during transformation, showing limited sensitivity to subtle variations in spatial distributions. Furthermore, their performance degrades substantially in the presence of noise and local perturbations, which are common in real-world geographic data.

Local Invariant Feature Descriptors techniques were initially developed for computer vision and are widely used in remote sensing for image registration and matching. SIFT (Scale-Invariant Feature Transform) and SURF (Speeded-Up Robust Features) are classic examples [20]. They generate descriptors by detecting keypoints in images and computing local gradient orientation histograms, making them invariant to scale and rotation. Although they excel at extracting local features, when applied to regional features, additional frameworks such as aggregation or Bag-of-Words are needed to integrate all local descriptors [20]. This complicates the descriptor generation process and may reduce performance when handling non-textured areas or continuous gradient fields.

Template Matching and Geometric Alignment Methods represent another major paradigm in regional feature representation. Zhang and Su [21] developed a fast matching algorithm accommodating angular variations through multi-angle template rotation, while Choi and Kim [22] introduced a two-stage approach achieving both rotation and illumination invariance. Traditional multi-angle matching is computationally prohibitive for large-scale registration. Current efforts focus on improving efficiency and robustness in multimodal remote sensing data. For instance, the Multi-scale Template Matching (MSTM) framework utilizes frequency-domain convolutional maps and omni-directional aggregated feature vectors to significantly speed up matching while improving adaptability to geometric differences and non-linear radiation differences between multimodal images [23]. Another strategy involves integrating feature matching with template matching: a “feature-to-template” approach leverages local structural information via Local Self-Similarity (LSS) templates for accurate fine matching after coarse alignment [24], successfully resisting significant geometric and intensity differences. These works demonstrate that the core concept of template matching is being updated with structural and frequency domain techniques to tackle modern geospatial challenges.

Shape-Based Descriptors and Contour Analysis techniques attempt to characterize regions through their geometric properties. Yang et al. [25] proposed an invariant multi-scale descriptor for shape representation, matching, and retrieval, incorporating both global shape characteristics and local boundary features. Wang et al. [26] developed a curvature saliency descriptor for complete and partial shape matching, emphasizing perceptually significant boundary segments. Nevertheless, these methodologies are primarily designed for objects with well-defined boundaries and struggle to characterize continuous spatial distributions exhibiting gradient properties, such as elevation surfaces or population density fields.

Deep Learning-Based Feature Representations have emerged as powerful alternatives in recent years. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and their variants excel at processing Euclidean grid data (e.g., remote sensing images and DEMs), automatically learning hierarchical spatial features. However, standard CNN architectures are inherently not rotation-invariant. This limitation must be mitigated through data augmentation or by designing specific rotation-equivariant convolutional kernels (e.g., RIC-CNN) [27]. As the latest state-of-the-art architecture, Vision Transformers (ViT) and its variants are being widely applied in remote sensing image analysis. ViT uses a multi-head attention mechanism to capture long-range contextual relationships between pixels (or image patches) [28]. This mechanism gives ViT greater potential than CNNs for capturing global spatial patterns. For non-Euclidean spatial data (such as Point-of-Interest (POI) distributions, traffic networks, or irregular polygonal land parcels), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as a powerful feature representation tool. GNNs learn node representations by aggregating information from neighboring nodes, thereby explicitly encoding spatial topological relationships (e.g., adjacency, connectivity) into the features [29]. This gives GNNs a distinct advantage in processing irregular spatial data and performing relational reasoning [30].

2.2. Regional Similarity Measurement

Quantifying similarity between spatial regions represents a fundamental analytical task with applications spanning environmental monitoring, urban planning, and resource management. The challenge lies in developing metrics that capture meaningful geographic relationships while remaining robust to variations in scale, orientation, and data modality.

Distance-Based Metrics constitute the most straightforward approach to similarity quantification. Classical measures including Euclidean distance, Manhattan distance, and cosine similarity. Although these approaches offer computational efficiency and simplicity, they demonstrate poor performance when addressing rotational transformations and fail to capture the intrinsic similarities between regions [31].

Structural and Topological Approaches explicitly model spatial relationships and organizational patterns. Shape-based matching techniques [25,26] evaluate regions through their boundary properties, medial axes, and skeletal representations. Graph-based methods represent regions as networks of interconnected features, comparing them through graph matching algorithms or spectral properties.

Graph-Based Similarity Learning methods model spatial regions as networks of interconnected features. Zhou et al. [32] proposed GRLSTM for trajectory similarity computation with graph-based residual LSTM, effectively capturing spatial network structures and temporal dependencies simultaneously. Recent work on deep graph similarity learning has developed sophisticated embedding techniques that map input graphs to target spaces where distances approximate structural distances in the input space, enabling more nuanced comparison of complex spatial relationships.

Deep Learning Approaches for Similarity Computation have gained substantial attention, often focusing on learning the similarity metric itself. These methods go beyond a simple distance calculation (like Euclidean) and instead learn a complex, non-linear function to compare feature vectors. A prominent architecture for this is the Siamese Neural Network. This approach uses two or more identical sub-networks (which can be the CNNs or GNNs discussed in Section 2.1) to process two input regions. The sub-networks output two feature vectors, which are then fed into a final set of layers that are trained to output a similarity score (e.g., 0 to 1). This “deep metric learning” approach is widely used in remote sensing for tasks like image patch matching. Furthermore, as mentioned in Section 2.1, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are particularly relevant. Models like DeepSIM [33] or trajectory similarity frameworks [34] utilize graph-based architectures not just for feature extraction, but as the core mechanism to compute the similarity between two complex graph structures. Despite achieving state-of-the-art performance in specific tasks, these approaches inherit the limitations of deep learning methods: substantial annotated data requirements (e.g., pairs of “similar” and “dissimilar” regions), limited interpretability, and potential brittleness when encountering distribution shifts between training and deployment environments.

Spatial Context-Aware Methods explicitly model spatial relationships and organizational patterns for similarity assessment. Jin et al. [35] proposed the Context-Aware Region similarity learning (CARE) framework that leverages spatial normalization techniques to measure regional significance within surrounding neighborhoods, enabling zero-shot inference for region similarity based on specific application requirements. This approach addresses the challenge of regions with different point-of-interest distributions sharing similar purposes across applications. Abbasi et al. [36] developed a geospatial semantic similarity measure combining BERT architecture with Moran’s I to improve the correlation between semantic similarity and geographical distance in natural language processing applications. These context-aware methods represent significant advances in capturing spatial dependencies, though they may require careful tuning of neighborhood definitions and spatial weight parameters.

3. Relevant Definition

3.1. Regional Feature Matrices

Regional feature matrices represent a two-dimensional array formulation derived from the spatial discretization of continuous geographic information. This representation method divides the study area into regular grid cells, with each cell storing location-specific geographic attribute information, such as elevation, population density, land use type, or vegetation coverage.

Formally, given a geographic region, we can partition it into a grid matrix M of size . Each element in this matrix (where and ) denotes the feature value of the grid cell located at the row and column. This value quantifies the geographic attribute characteristics at that spatial position. The dimensions p and q of matrix M correspond to the granularity of spatial division in the two directional axes of the study area, while the scale of division depends on the specific application scenario and data precision requirements.

Regional feature matrices provide a unified data structure that enables quantitative comparison and mathematical operations on spatial characteristics across different geographic regions, establishing a foundation for subsequent similarity calculations and rotation invariance analysis.

3.2. Coordinate Transformation

In ring vector-based regional similarity measurement, we need to establish a mapping relationship between the matrix index coordinate system and the standard Cartesian coordinate system to more effectively define and manipulate the ring structure.

Consider an odd-order matrix M with row and column indices starting from 0. The center point C of the matrix is located at the row-column coordinates . To facilitate the definition and analysis of ring layers, we establish a Cartesian coordinate system with the center point C as the origin, defined as follows:

- X-axis direction: Consistent with the column direction of the matrix, with positive direction to the right

- Y-axis direction: Opposite to the row direction of the matrix, with positive direction upward (contrary to the traditional rule where matrix row indices increase from top to bottom)

Based on the above definition, there exists a one-to-one conversion relationship between the row-column index coordinates of any element in the matrix and its Cartesian coordinates. For any element in the matrix, where , its coordinates in the Cartesian coordinate system with the center point C as the origin are calculated as Equation (1):

where:

- x represents the horizontal offset of the element relative to the center point C (positive to the right, negative to the left);

- y represents the vertical offset of the element relative to the center point C (positive upward, negative downward).

Conversely, for any point in the Cartesian coordinate system that satisfies the condition , the corresponding matrix row-column indices can be calculated using the following Equation (2):

This coordinate transformation mechanism provides us with the ability to flexibly switch between matrix indices and the Cartesian coordinate system, making ring-based feature extraction and rotation invariance analysis more intuitive and convenient. In particular, using the Cartesian coordinate system allows for a more natural definition of the ring boundary condition , thereby constructing a rotation-invariant ring vector representation.

3.3. Ring Vector

The ring vector represents a spatial feature representation method that radiates outward from the matrix center. By organizing matrix elements into concentric rings, this approach provides a rotation-invariant feature extraction mechanism.

Given an odd-order matrix M, where and , we define the center point C of the matrix at coordinates . Taking this center point as the origin of a Cartesian coordinate system, each element in the matrix can be represented by coordinates , where .

The ring vector consists of concentric square rings, each organizing matrix elements into vectors according to specific rules. The r-th ring contains all matrix elements that satisfy Equation (3):

where represents the relative coordinates of the element with respect to the center point C.

Considering the center point as a one-dimensional vector , each concentric ring r surrounding the center point contains elements. These elements are organized into a vector following a predefined traversal order (e.g., clockwise direction). The complete representation of the ring vector is expressed as the sequence , where each captures the spatial feature distribution of the matrix at a distance of r units from the center.

This ring-based representation method provides a structured approach to describe the spatial features of a matrix, establishing a foundation for implementing rotation-invariant similarity measures in subsequent analyses.

4. Methodology

This section provides a detailed description of the regional similarity measurement method based on ring vector representation. The proposed approach utilizes ring vectors as its foundation to establish a framework for regional feature representation and similarity computation with rotational invariance. This framework effectively captures the intrinsic similarity of regional features under rotational transformations.

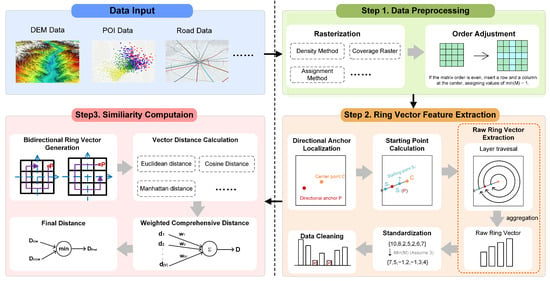

As illustrated in Figure 2, the overall framework of this methodology is structured into three core stages:

Figure 2.

Overall Framework of the Ring Vector-based Similarity Method.

- Data Preprocessing. This stage processes multi-source input data, such as DEM or POI datasets. It employs rasterization to convert unstructured data into standard feature matrices and performs matrix order adjustment to ensure a unique center point, establishing a foundation for subsequent analysis.

- Ring Vector Feature Extraction. This stage, central to our method, begins with “Directional Anchor Localization” (i.e., locating the maximum value point) to determine the region’s dominant direction. Subsequently, a dynamic “Starting Point” is calculated for each ring layer, from which a “Raw Ring Vector” is extracted via traversal. Finally, these vectors undergo “Standardization” and “Data Cleaning” to eliminate scale effects and remove invalid padding values.

- Similarity Computation. This phase first generates “Bidirectional Ring Vectors” (clockwise and counter-clockwise) to enhance robustness against rotational transformations. A ”Distance Calculation” (e.g., Euclidean distance) is then applied to quantify the dissimilarities between corresponding ring layers. These individual distances are ultimately aggregated into a “Weighted Comprehensive Distance”, which serves as the final metric for regional similarity.

4.1. Data Preprocessing

4.1.1. Rasterization

The ring vector construction algorithm requires structured raster data as input, represented as a regular grid matrix . However, a large number of spatial datasets are inherently unstructured, including discrete point data (e.g., POIs, GPS trajectories, sensor networks) and linear features (e.g., road networks, river systems). To adapt our methodology to these unstructured data types, a critical rasterization preprocessing step is required to convert them into structured feature matrices. Specifically, for discrete point data, common point rasterization methods such as the Density Method (e.g., point count density), Kernel Density Estimation (KDE), or even the Assignment Method (for attributing single-point values to grid cells) can be employed. For linear features, core line rasterization techniques like the Coverage Raster Method (to identify line presence within grids), Length-Weighted Method (to quantify proportional line length in each cell), or Distance Raster Method (to characterize proximity to linear features) are applicable to quantify feature relevance within each grid cell. Our urban functional area experiment (Section 5.3.2) serves as a concrete example to illustrate the implementation details of this rasterization preprocessing step.

4.1.2. Matrix Order Adjustment

After obtaining the feature matrix, the proposed algorithm requires the matrix to be of odd order to ensure the uniqueness of the center point. For an input matrix , the following order verification and adjustment are performed:

- If the matrix order N is odd, the original matrix is used directly: , with order .

- If the matrix order N is even, an additional row and column are inserted at the center position (i.e., at the intersection of the -th row and column), with each fill values set to , forming an adjusted matrix with order .

The padding value is set to , an extreme outlier, which ensures it will never be selected as the directional anchor (Section 4.2.1). Crucially, this padding value is explicitly identified and removed during the ’Data Cleaning’ step (Section 4.2.4) before any distance calculations are performed. Therefore, the padding acts purely as a structural placeholder to establish a unique matrix center and does not contribute to the final feature vector’s magnitude or pattern.

4.2. Ring Vector Feature Extraction

In the Ring Vector Feature Extraction stage, the process begins by locating the global maximum value, excluding the center point, within the matrix and defines it as the directional anchor P. Then, using the vector from the center point C to this directional anchor P as the directional reference, a dynamic traversal starting point is calculated for each concentric ring layer r. Subsequently, a clockwise traversal is performed from each ring’s starting point , collecting the element values along the path to construct the raw ring vector for that layer. Finally, all raw ring vectors undergo standardization and data cleaning, yielding the final ring vectors set for the feature matrix. The detailed steps of this procedure are elaborated in the following subsections.

4.2.1. Directional Anchor Localization

To capture significant features within the matrix, the directional anchor of the adjusted matrix is defined as the global maximum value point P, excluding the center point C. The center point C has row and column coordinates . The selection is based on the hypothesis that the maximum value point P in the matrix characterizes the most significant feature of the region and can serve as an indicator of regional directionality, providing a directional reference for ring vector extraction.

The row and column coordinates of the maximum value point P are transformed into Cartesian coordinates with the center point C as the origin according to Equation (1). This transformation establishes a unified spatial reference framework, making the analysis of regional directionality more intuitive.

4.2.2. Ring Vector Starting Point Calculation

This part introduces an adaptive mechanism for selecting ring vector starting points that achieves rotation invariance in feature representation by effectively capturing the directional characteristics of spatial structures. The main idea of this algorithm is that, for each ring layer, the starting point selection follows the dominant direction established from the center point C to the maximum value point P, thereby maintaining consistent relative directional relationships under rotational transformations.

In a Cartesian coordinate system with the center point C as the origin, the coordinates of the maximum value point P contain critical directional information. Based on the relative magnitudes and signs of these coordinate components, we establish a precise directional classification framework that maps all possible spatial orientations into four dominant cases:

- Case 1 (Y-positive dominance): and , indicating that the maximum value point resides in the upper half-plane with the vertical upward component being dominant.

- Case 2 (X-negative dominance): and , indicating that the maximum value point resides in the left half-plane with the horizontal leftward component being dominant.

- Case 3 (Y-negative dominance): and , indicating that the maximum value point resides in the lower half-plane with the vertical downward component being dominant.

- Case 4 (X-positive dominance): and , indicating that the maximum value point resides in the right half-plane with the horizontal rightward component being dominant.

Following the determination of directional dominance, the algorithm computes the Cartesian coordinates of the starting point for each concentric layer r (where ). This calculation preserves the directional consistency between the starting points of various ring layers and the maximum value point P, while adapting to the spatial scope of different ring layers:

- Case 1: .

- Case 2: .

- Case 3: .

- Case 4: .

Here, denotes the operation of rounding to the nearest integer.

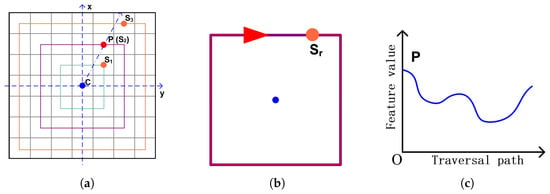

Figure 3a illustrates this process. The starting points for each layer (e.g., , , ) are all calculated to lie on the directional vector from the center C to the anchor point P. In this specific visual example, the anchor point P happens to be located on the second ring, which means the starting point and the anchor point P are the same point.

Figure 3.

Schematic Diagram of Key Steps in Ring Vector Generation. (a) Starting Point Calculation, and different colored lines represent different layers. (b) Raw Ring Vector Extraction. (c) The Variation Trend of Feature Values.

This direction-adaptive computational mechanism ensures that across different ring layers, the starting points maintain a consistent spatial directional relationship with the maximum value point. When the matrix undergoes rotational transformation, although the absolute position of the maximum value point changes, the ring layer starting points calculated using the aforementioned method maintain their invariant relative positional relationship with the maximum value point, thereby achieving invariance to rotational transformations during the feature extraction process.

4.2.3. Raw Ring Vector Extraction

Starting from the initial point of each ring layer r, we traverse the entire layer in a clockwise direction, and collect matrix element values along the traversal path to form the raw ring vector , as illustrated in Figure 3b, where represents the value of the j-th element in the r-th ring layer. Each ring layer r contains elements. During the traversal process, we employ coordinate transformation rules to map points in the Cartesian coordinate system back to matrix row and column indices , thereby extracting the corresponding matrix element values. After processing ring layers, we obtain ring vectors, which together with the one-dimensional vector formed by the center point, constitute the raw ring vector set . During traversal starting from the starting point , the collected feature values follow a distinct trend. They decrease gradually at the beginning, but start to increase again as the traversal nears point , as shown in Figure 3c.

4.2.4. Vectors Standardization and Data Cleaning

To eliminate the influence of scale differences among eigenvalues on similarity measurements, the original ring vectors must undergo standardization and removal of invalid data introduced during standardization. First, each original ring vector is subjected to a translation transformation using Equation (4):

This operation normalizes the data baseline to zero by subtracting the minimum value of the feature matrix , thereby eliminating differences in absolute numerical scale.

Following standardization, it is necessary to remove padding values inserted during the matrix standardization phase, as their presence would interfere with similarity calculations. These padding values consistently transform to after standardization. The cleaning operation is defined by Equation (5):

The cleaned ring vector retains only the valid features from the original matrix. Notably, center points of even-order matrices (standardization padding values) are eliminated in this step, ultimately generating a refined set of ring vectors:

Therefore, for any square matrix of order , the modulus length of the final ring vector set is . The ring vector set can be uniformly expressed as:

The cardinality (length) of each ring vector is defined as:

Based on the construction process described above, the ring vector representation possesses the following key characteristics:

- Directional Consistency: Through maximum value point localization and region classification, we ensure that even when the matrix is rotated, the starting point of the ring vector maintains a relatively consistent spatial direction.

- Structural Preservation: The ring layer structure preserves the spatial adjacency relationships among elements in the matrix, enabling the ring vector to effectively capture the spatial structural features of the region.

- Scale Invariance: Vector normalization processing eliminates the influence of numerical scale, making the ring vector robust to intensity variations in regional features.

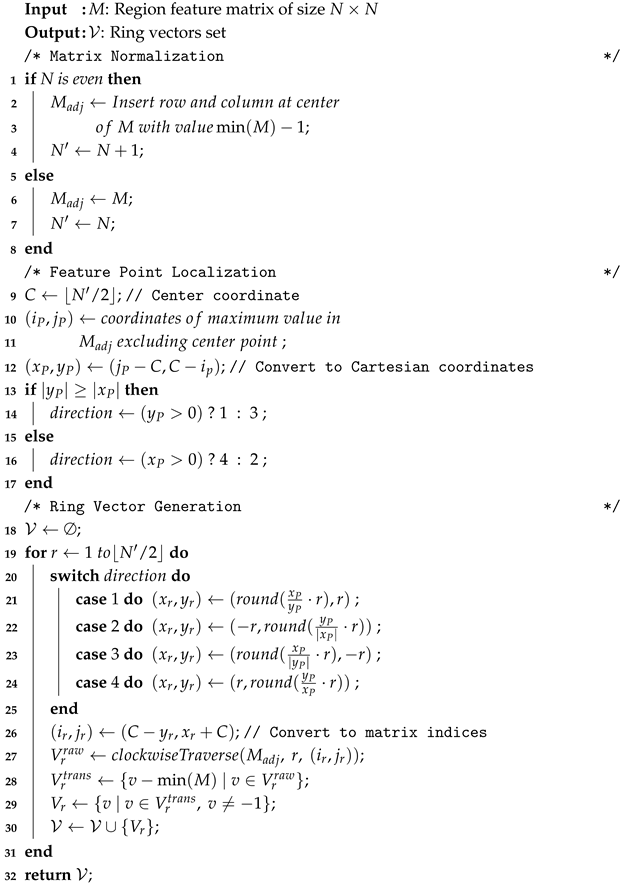

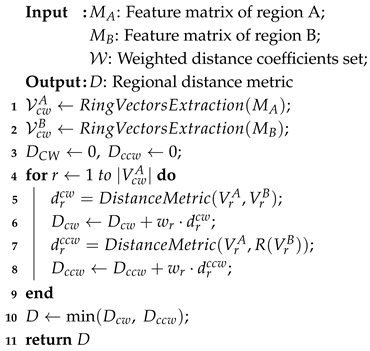

These characteristics collectively ensure that the ring vector remains relatively stable under matrix rotational transformations, providing a solid foundation for implementing rotation-invariant regional similarity metrics. The ring vector not only captures the spatial distribution features of a region but also, through its special construction mechanism, achieves adaptability to regional rotational transformations, enabling similarity calculations based on this approach to identify essentially similar regions under different rotational states. The pseudo-code for ring vector generation is shown in Algorithm 1.

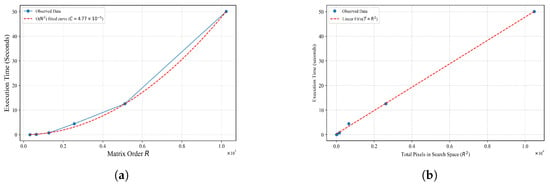

The time complexity of the Ring Vector Generation Algorithm can be analyzed through its two primary phases.

In the standardization phase, the algorithm first checks whether the input matrix has odd or even dimensions, which constitutes an operation. For matrices with even dimensions, the algorithm creates a new matrix and copies the original data, requiring operations. Subsequently, the algorithm identifies the maximum value point by traversing all elements (excluding the center point), yielding a time complexity of . The conversion of matrix indices to Cartesian coordinates is performed in constant time, .

During the ring vectors generation phase, the algorithm processes concentric rings, where represents the adjusted matrix dimension (approximately equal to N). For each ring r, the algorithm processes elements, with each element requiring constant time operations for coordinate transformation and value extraction. Consequently, the total processing time for all rings can be expressed as Equation (9),

When , can be simplified to approximately , which asymptotically approaches . Combining both phases, the overall time complexity of the Algorithm 1 is .

| Algorithm 1: Ring Vectors Extraction |

|

4.3. Similarity Computation

Given two regional feature matrices of identical dimensions, , this section presents a similarity measurement method based on bidirectional ring vectors to quantify the degree of similarity between two regional feature distributions.

For the two input regional feature matrices and , we first apply Algorithm 1 to generate their corresponding sets of clockwise traversal ring vectors:

- The clockwise traversal ring vector set for is defined as

- The clockwise traversal ring vector set for is defined as

To enhance the algorithm’s robustness against rotational invariance, we further derive the counterclockwise traversal ring vector set for from as , where represents the reverse operation on vector elements while maintaining the position of the first element unchanged as Equation (10),

The distances in both traversal directions are calculated as shown in Equations (11) and (12):

where can be selected based on specific data characteristics, such as Euclidean distance, Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD), or other appropriate metrics. The term represents the clockwise directional distance between ring vectors of layer r from both matrices, while represents the counterclockwise directional distance.

Based on the distances at each ring layer, we calculate the weighted comprehensive distance for both traversal directions using Equations (13) and (14):

where represents the comprehensive clockwise directional distance between and ring vectors, and represents the comprehensive counterclockwise distance. The coefficient is the weight assigned to ring layer r, satisfying the normalization condition .

The final regional distance metric D is defined as the minimum value between the clockwise comprehensive distance and the counterclockwise comprehensive distance, as shown in Equation (15):

This bidirectional ring vector generation strategy enables the algorithm to simultaneously consider feature distribution patterns in both clockwise and counterclockwise directions across the region, effectively enhancing recognition robustness against mirror symmetry transformations and reverse rotation patterns. The complete algorithm procedure is presented in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: Area Similarity Measurement |

|

For two regional feature matrices and to be compared, our algorithm applies Algorithm 1 to generate clockwise ring vectors with a time complexity of . When generating counterclockwise ring vectors, we perform an element reversal operation on the clockwise vectors according to the Equation (10). This process requires processing all elements in the matrix, resulting in an equivalent time complexity of .

In the distance calculation phase, the algorithm’s performance is influenced by the chosen distance metric method. Assuming that the computational complexity of a single element comparison operation is , the overall complexity can be analyzed as follows:

- Single-layer Distance Calculation: If the selected distance metric method has a computational complexity for vectors of length L, where represents the additional operational complexity for each element comparison, then the distance calculation complexity for layer r is at most . This is because the ring vector at layer r contains a maximum of elements (each layer forms a ring path with a “perimeter” of ).

- Total Distance Calculation Complexity: By summing the computational complexity across all layers:

The algorithm calculates distances in both clockwise and counterclockwise directions, essentially executing the distance calculation process twice. Therefore, the overall time complexity of Algorithm 2 is .

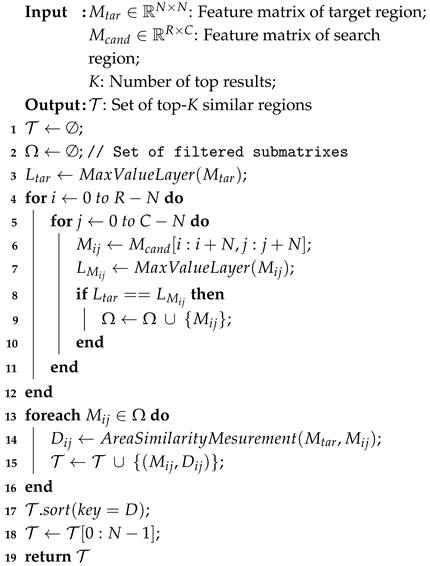

In the field of regional distribution pattern similarity search, traditional methods typically employ sliding window techniques to enumerate all possible sub-regions within a given area. These approaches calculate the similarity between each subregion and the target pattern, ultimately identifying the K regions with the highest similarity scores. However, this exhaustive search strategy incurs substantial computational costs when processing large-scale regional data, making it inefficient for many practical applications.

To enhance search efficiency, our research introduces a pre-filtering mechanism based on ring layer features. This approach stems from a key observation about regional distribution patterns: the ring layer containing the maximum value typically reflects the core distribution characteristics of a region (such as terrain peaks or areas of high population density). This observation leads to an important insight: if two regions exhibit significant differences in their maximum value ring layers, their overall distribution patterns are unlikely to possess high similarity. By leveraging this property, we can quickly eliminate many dissimilar regions before performing more computationally intensive similarity calculations.

Let us examine the theoretical basis for this approach. Consider two highly similar regional feature matrices and , with their respective ring vector representations:

According to our definition of similar regions, the weighted comprehensive distance between and should approach zero. Consequently, the distance between their ring vectors at each layer should also approach zero.

The ring layer that contains the maximum value plays a particularly crucial role in characterizing regional features. Therefore:

This mathematical relationship indicates that the feature distributions in the ring layers containing the maximum values of both matrices should exhibit high similarity. Since maximum value points typically represent the most significant features in a region, these points should maintain consistent positions within similar regions.

The algorithm can be formally described through the following steps:

- Input Definition: Given a target region feature matrix and a larger region matrix to be searched .

- Target Analysis: Extract the ring layer containing the maximum value point from the target matrix .

- Candidate Generation: Employ a sliding window technique to traverse all possible sub-matrices in .

- Feature Extraction: For each sub-matrix , calculate the ring layer containing its maximum value.

- Pre-filtering: Apply the ring layer filtering condition: if , add to the candidate set .

- Refined Similarity Calculation: For each region in the candidate set , apply Algorithm 2 to calculate its distance from the target region.

- Result Ranking: Sort by distance and return the set containing the K regions with the highest similarity.

The pseudocode for this algorithm is presented in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3: Similar Region Search |

|

To determine the layer containing the maximum value point in the target matrix , we must traverse the entire matrix to identify the maximum value. This step has a time complexity of . Determining the layer to which the maximum value belongs is an operation. Therefore, the total complexity of this preliminary step is .

When using the sliding window approach to traverse all potential sub-matrices, there are sub-matrices to examine, where R and C represent the dimensions of the larger search space. For each sub-matrix, the algorithm performs the following operations:

- Sub-matrix Extraction: Obtaining the candidate sub-matrix through index slicing, which is a pure indexing operation with a time complexity of .

- Maximum Value Point Localization: Finding the maximum value point within the candidate sub-matrix requires traversing all elements, resulting in a time complexity of .

- Layer Assignment and Filtering: Determining the layer to which the maximum value point belongs and comparing it with the target layer . If they match, the sub-matrix is added to the candidate set . These operations require constant time, with a complexity of .

Consequently, the complexity of a single iteration is , and the total complexity of the sliding window traversal is .

Considering the continuity of the sliding window in both horizontal and vertical directions, we can optimize the maximum value update process through incremental computation:

- Horizontal Sliding Optimization: When the window moves from position to , the new window removes the leftmost column (N elements) and adds a rightmost column (N elements). By maintaining information about the current window’s maximum value and its position, the maximum value can be incrementally updated in time.

- Vertical Sliding Optimization: Similarly, when the window moves from position to , incremental updates can be performed by removing the top row and adding a bottom row.

- Optimized Complexity: Through incremental computation, the complexity of a single window movement for maximum value updates is reduced from to , resulting in an optimized total time complexity for the sliding window traversal as .

This optimization delivers significant performance improvements in large-scale search scenarios.

Assuming the number of candidate regions retained through the pre-filtering mechanism is , complete similarity calculations (invoking Algorithm 2) must be executed for each candidate region. The computational complexity for calculating the similarity of a single candidate region is (as described in Part B). Inserting the calculated similarity results into an ordered result set can be accomplished in time using appropriate data structures (such as heaps or balanced binary trees), where K represents the number of top-K results to be returned.

Therefore, the complexity for similarity calculation of a single candidate region is . Consequently, the total complexity for similarity calculations across all candidate regions is .

Integrating the above analyses, the total time complexity of Algorithm 3 is , where the first term represents the preprocessing complexity for the target region, the second term represents the optimized sliding window traversal complexity for pre-filtering, and the third term represents the complexity for similarity calculations across candidate regions.

4.4. Elaboration on Rotational Invariance

The rotational invariance of the proposed similarity measure is ensured by the combination of two core mechanisms: the Dynamic Anchor Localization (Section 4.2.1) and the Bidirectional Matching Strategy (Section 4.3):

- Role of the Dynamic Anchor (Primary Invariance): The Dynamic Anchor (the global maximum value point P) acts as an internal, data-driven “compass” for the matrix. Consider a matrix M and its version which has been rotated by 45°. In M, the algorithm identifies the max point and calculates all starting points relative to the vector 8. This generates the ring vector set . In , the entire internal structure is rotated. The original max point is now at a new 45° position, . The algorithm, when run on , identifies as its anchor. It then calculates its starting points relative to the vector . Because the relative structure is identical (just rotated), the vector generated from this process will be identical to the original vector . The dynamic anchor effectively "normalizes" the vector generation process, ensuring the final vectors are already aligned, regardless of the original matrix’s orientation.

- Role of Bidirectional Matching (Safeguard): The Bidirectional Matching strategy is a safeguard against perfect 180° rotations or mirror-symmetric patterns. A 180° rotation is functionally equivalent to traversing the same ring in the reverse (counter-clockwise) direction. By calculating the distance for both the clockwise vector () and its reverse () and taking the minimum, the method robustly identifies 180° rotations as highly similar.

5. Experimental Evaluation

In this section, we systematically evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm. We first detail the experimental configuration and justify our selection of validation datasets, followed by three targeted experiments across diverse datasets. This comprehensive approach demonstrates the algorithm’s performance characteristics and computational efficiency in various application scenarios.

5.1. Datasets

To ensure a comprehensive and representative evaluation, we selected three datasets with significant domain differences and diverse spatial characteristics. Each dataset provides specific validation dimensions and challenging scenarios for our algorithm.

5.1.1. SRTM 90M DEM

The SRTM 90M DEM (Shuttle Radar Topography Mission 90 Meter Digital Elevation Model) is a global digital elevation model jointly released by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA). This dataset provides global terrain coverage with a spatial resolution of 90 m and is accessible from the CGIAR Consortium for Spatial Information (CGIAR-CSI) website (https://srtm.csi.cgiar.org/ (accessed on 27 September 2024) ). It constitutes an important open resource for terrain analysis research.

5.1.2. Beijing WIFI Access Point Dataset

The dataset utilized in this experiment comprises the geospatial distribution information of 23,144,836 WIFI access points across Beijing, comprehensively reflecting the density and distribution characteristics of the city’s digital infrastructure. Each record details the access point’s latitude and longitude coordinates, MAC address, and associated address information. Given our focus on the core metropolitan area, the study scope was confined to the region within Beijing’s Fourth Ring Road, from which 6,982,254 data points were extracted, with only their coordinates used for subsequent analysis. The spatial distribution pattern of WIFI access points is highly correlated with human activity intensity and urban development density, establishing this dataset as an ideal testing scenario for validating the algorithm’s capability to identify similar distribution patterns. The inherent high density and heterogeneity of these data points provide a challenging validation environment for the pattern matching algorithm, effectively assessing the proposed method’s robustness and efficacy in processing complex urban spatial data.

5.1.3. Beijing POI Dataset

The Beijing Points of Interest (POI) dataset contains 633,372 spatial records covering nine major functional categories, including catering services, scenic spots, corporate enterprises, commercial shopping centers, and business residences. Consistent with our WIFI dataset processing approach, we limited the analysis to within Beijing’s Fourth Ring Road, ultimately utilizing 135,659 data points with only their geographical coordinates extracted. POI data typically form functional cluster areas (such as business centers and shopping districts), presenting unique spatial distribution patterns. This provides an ideal testing foundation for evaluating the algorithm’s performance in identifying similarities between urban functional areas.

5.2. Experimental Setup

5.2.1. Experimental Design

Euclidean distance is employed for ring vector similarity measurement and equal weighting is adopted across ring layers in our experimental framework, with detailed justifications provided in Section 5.2.2 and Section 5.2.3. Three experiments were designed to evaluate the algorithm’s rotation invariance, engineering applicability, and multi-type data adaptability.

- Experiment 1: Dam Terrain Classification. Eight representative dams worldwide were selected as research subjects, with terrain features extracted from SRTM 90M DEM data. These dams can be classified into two categories based on construction terrain: gravity dams (Three Gorges, Itaipu, Guri, Grand Coulee) located in wide U-shaped valleys spanning one to two kilometers, and arch dams (Baihetan, Xiluodu, Wudongde, Jinping-I) situated in narrow V-shaped canyons with steep slopes. The primary objective of this experiment is to verify the effectiveness of the proposed method in identifying similar terrain features, and to benchmark its performance against established baseline methods, including Normalized Cross-Correlation (NCC), Fourier-Mellin Transformation (FMT) [18], and Zernike Moments (ZM) [19].For each dam area, a grid size was employed, covering approximately 2.25 km × 2.25 km around each dam. This dimension was determined through preliminary testing with grid sizes ranging from to , which demonstrated stable discrimination performance in the to range. The configuration was selected to optimally balance three requirements: capturing sufficient terrain context beyond the dam structure, maintaining adequate resolution for elevation gradient representation, and avoiding inclusion of irrelevant distant terrain.

- Experiment 2: FAST Telescope Site Selection. China’s FAST radio telescope site selection was used as a case study to demonstrate practical engineering application. The telescope requires karst depression terrain with “high periphery, low center” morphology. An grid was extracted from the actual FAST construction site as the template, covering 720 m × 720 m at 90 m resolution.This grid size was determined to directly correspond to engineering requirements: the configuration at 90 m resolution yields 720 m total coverage, accommodating FAST’s 500 m aperture with approximately 110 m peripheral margin on each side. This margin is essential for capturing the surrounding high-elevation terrain that characterizes suitable sites. Smaller grids would truncate the critical peripheral features, while larger grids would introduce irrelevant distant terrain. The search space encompassed the southern Guizhou karst region ( grid cells, approximately 456 km × 146 km), and the top-20 candidate regions were retrieved.

- Experiment 3: Urban Functional Area Identification. WiFi access point and POI distributions within Beijing’s Fourth Ring Road were analyzed to demonstrate adaptability to urban spatial data. The study area was partitioned into 200 m × 200 m grid cells, totaling cells.This cell size was chosen to align with typical urban functional block scales in Beijing, where coherent zones (residential compounds, commercial clusters, parks) span 100–300 m. Finer resolutions would fragment functional areas across excessive cells, while coarser resolutions would merge distinct zones. At 200 m resolution, the grid provides sufficient detail for block-level analysis while maintaining computational tractability for large point datasets. Taoranting Park and its northwestern region were selected as the template, exhibiting a distinct “dense on one side, sparse on the other” pattern characteristic of park-residential interfaces. The top 10 most similar regions () were retrieved for both datasets.

5.2.2. Distance Measurement Method

Euclidean distance was selected as the fundamental metric for measuring ring vector similarity based on three key advantages. First, geometric intuitiveness is provided through direct measurement of straight-line distance in multidimensional space, naturally reflecting differences in spatial distribution patterns. Second, high computational efficiency is achieved with O(N) complexity, making the method suitable for large-scale analysis. Third, essential mathematical properties (non-negativity, identity, symmetry, triangle inequality) are satisfied, ensuring reliable and consistent measurement behavior.

For two ring vectors and , their Euclidean distance is defined as Equation (18):

where n is the dimension of the vector, and and represent the values of the two vectors in the l-th dimension, respectively.

5.2.3. Multi-Layer Ring Vector Weighting Strategy

When calculating comprehensive similarity using multi-layer ring vector distances, we adopted an average weighting strategy. Specifically, each ring layer is assigned an equal weight coefficient as Equation (19):

where is the total number of ring layers, and is the weight coefficient for the r-th ring layer.

In our concentric ring structure, ring layer r contains elements, meaning outer rings contain progressively more elements and cover larger geographic areas. When Euclidean distance is computed between corresponding ring layers, larger distance values are naturally produced by outer rings due to their increased element counts, even with similar per-element differences. This natural increase effectively emphasizes large-scale spatial structures without requiring explicit weighting schemes. These natural data distribution characteristics are preserved through equal weighting, allowing the relative importance of different scales to emerge from the data structure itself rather than being imposed through arbitrary parameters. This makes the algorithm more general and applicable across diverse domains without requiring application-specific calibration.

5.3. Experiment Results and Analysis

5.3.1. Experiment 1

To validate the proposed algorithm’s performance in terrain feature capture and rotational invariance, this experiment was conducted using eight globally representative dams as research subjects, with NCC, FMT, and ZM applied as baseline methods for comparison. Based on their structural types and terrain adaptability, these dams were classified into two categories:

- Gravity Dams: These are distributed across wide, gentle U-shaped valleys or Y/T-type river sections. The river valleys typically span 1–2 km in width with gradual slopes and minimal upstream-downstream elevation differences. The reservoir areas are predominantly characterized by wide valleys, hills, or plateaus. Representative projects include Three Gorges Dam (Yangtze River, China), Itaipu Hydroelectric Dam (Paraná River, Brazil/Paraguay), Guri Hydroelectric Power Station (Caroní River, Venezuela), and Grand Coulee Dam (Columbia River, USA).

- Arch Dams: These are primarily concentrated in deeply incised canyon regions with narrow V-shaped or U-shaped valleys. These sites feature steep slopes, high mountain symmetry, significant elevation differences, and dramatic terrain fluctuations. Representative projects include Baihetan Hydropower Station (Jinsha River, China), Xiluodu Hydropower Station (Jinsha River, China), Wudongde Hydropower Station (Jinsha River, China), Jinping-I Hydropower Station (Yalong River, China).

Figure 4 presents DEM renderings of selected study areas, clearly illustrating the distinct terrain characteristics associated with different dam types. In the experiment, using each dam’s center as the origin point, we extracted grid regions (covering 2.25 km × 2.25 km) from SRTM 90M DEM data, ensuring the analysis window encompassed both the dam structure and surrounding characteristic terrain features.

Figure 4.

Representative dams DEM rendering images. (a) Three Gorges Dam. (b) Itaipu Hydroelectric Dam. (c) Baihetan Hydropower Station. (d) Xiluodu Hydropower Station.

The proposed algorithm was applied to calculate the distance D between the eight dam regions, which was then converted to a normalized similarity score S:

where represents the maximum distance value among all dam pairs, ensuring that , with higher values indicating greater similarity.

To quantitatively assess algorithm performance, we defined three key metrics:

- Intra-class Similarity (): The average similarity score between dam pairs within a single category. In this experiment, we calculate two such metrics: for gravity dams and for arch dams.

- Inter-class Similarity : The average similarity score between dam pairs across different categories.

- Discrimination : The overall classification capability, defined as the difference between the average intra-class similarity () and the inter-class similarity ().

All four methods (our method, NCC, FMT, and ZM) were applied to the eight dam DEM datasets. For NCC, the maximum correlation coefficient was first converted to a distance metric (D = 1 − NCC), which was subsequently normalized using Equation (20) to yield the final similarity score. For FMT, ZM, and our method, similarity was calculated based on the Euclidean distance between their respective feature vectors, which was then normalized using Equation (20). The resulting classification performance metrics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative performance on the Dam Classification task.

The results in Table 1 clearly and quantitatively demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed method. The method achieved high intra-class similarity scores for both gravity dams () and arch dams (). These results are particularly significant as they demonstrate that the proposed method successfully overcomes substantial directional differences among dams within the same category (e.g., Itaipu and Guri, which are rotated almost 180° relative to each other). This capability to accurately identify similarly typed dams regardless of their orientation explicitly validates the method’s rotation-invariant characteristics.

This rotational robustness stands in sharp contrast to the traditional Template Matching (NCC) method, which failed entirely () due to its critical weakness in handling directional sensitivity. The established rotation-invariant methods, FMT and Zernike Moments, performed better (positive ), which validates their known theoretical properties. However, the proposed method achieved a far superior discrimination score of .

This comparative analysis confirms the advancement of the proposed approach. The method uniquely achieves robust rotation invariance while simultaneously preserving the multi-scale spatial structure. This preservation of interpretable spatial patterns allows it to capture the nuanced terrain differences between the “U-shaped” gravity dam valleys and the "V-shaped" arch dam canyons far more effectively than other methods.

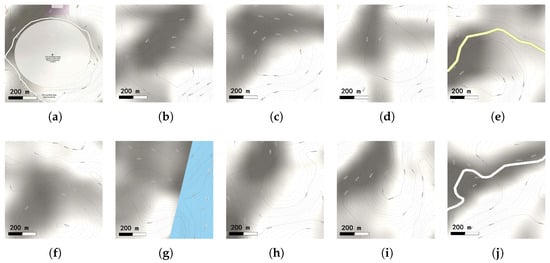

5.3.2. Experiment 2

Southern Guizhou represents one of China’s most extensively developed karst topographical regions, characterized by widespread dissolution depressions (approximately 300–800 m in diameter). These natural formations inherently conform to the “high periphery, low center” bowl-shaped terrain requirements for the 500-m aperture Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) [37]. This experiment aims to validate the proposed algorithm’s capability to precisely search for specific terrain patterns in complex topographical regions and to evaluate its practical application value in large-scale engineering site selection.

The experiment selected Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data from the actual FAST telescope construction site (Dawodang depression in Pingtang County, Guizhou Province) as a template, extracting an grid (720 m × 720 m, 90 m resolution) that precisely covered its core depression area (approximately 500 m in diameter). The research employed SRTM 90 M DEM data from southern Guizhou as the search space, encompassing grid cells (approximately 456 km × 146 km), comprehensively covering regions with dense karst topography. The actual FAST site location falls within this search range, facilitating comparison between algorithm-recommended areas and the actual site’s terrain similarity.

By applying Algorithm 3 and traversing the entire search area with an sliding window, we extracted the 20 candidate regions with the highest similarity scores. Table 2 presents the key parameters of these candidate regions and their comparison with the FAST template region. Evaluation metrics include similarity scores and critical engineering parameters, including peripheral elevation difference and depression diameter.

Table 2.

FAST Construction Site Similar Area Search Results.

Table 2.

FAST Construction Site Similar Area Search Results.

| Area | Similarity | Peripheral | Depression | Figure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Elevation | Diameter | ||

| (0–1) | Difference (m) | (m) | ||

| FAST | 1.0 | 255 | 600 | Figure 5a |

| 1 | 0.9516 | 209 | 560 | |

| 2 | 0.9484 | 228 | 580 | Figure 5b |

| 3 | 0.9479 | 231 | 650 | |

| 4 | 0.9468 | 225 | 680 | |

| 5 | 0.9448 | 220 | 650 | Figure 5c |

| 6 | 0.9430 | 256 | 500 | |

| 7 | 0.9424 | 201 | 400 | |

| 8 | 0.9419 | 261 | 500 | Figure 5d |

| 9 | 0.9418 | 254 | 450 | Figure 5e |

| 10 | 0.9417 | 211 | 560 | Figure 5f |

| 11 | 0.9416 | 237 | 600 | |

| 12 | 0.9408 | 261 | 650 | Figure 5g |

| 13 | 0.9408 | 261 | 650 | Figure 5h |

| 14 | 0.9401 | 200 | 500 | |

| 15 | 0.9400 | 237 | 480 | |

| 16 | 0.9391 | 232 | 400 | Figure 5i |

| 17 | 0.9391 | 211 | 500 | |

| 18 | 0.9389 | 224 | 650 | |

| 19 | 0.9387 | 315 | 400 | Figure 5j |

| 20 | 0.9387 | 205 | 380 | |

| avg | 0.9424 ±0.0036 | 234.55 ± 23.82 | 539.5 ± 96.5 |

The ring vector-based algorithm demonstrated high precision and robustness in identifying specific terrain patterns. All Top-20 candidate regions identified by the algorithm exhibited the typical “high periphery, low center” karst depression morphological characteristics, achieving a precision of for this search task with regions 2, 5, 8, 14, and 16 displaying particularly high structural similarity to the actual FAST radio telescope construction site. Quantitative analysis revealed:

- The average similarity score of candidate regions reached , indicating the algorithm’s high precision in identifying terrain features. Notably, the standard deviation of similarity was , reflecting the stability and consistency of algorithm output—a significant attribute for large-scale spatial data analysis.

- The average peripheral elevation difference was m, close to the FAST template region (255 m) and within the acceptable engineering error range.

- The mean depression diameter distribution was m, with most regions satisfying FAST’s engineering requirements for bowl-shaped depression dimensions (500 m aperture). This demonstrates the algorithm’s capacity to precisely capture terrain features at specific scales.

Despite the algorithm’s effective performance in terrain pattern recognition, actual engineering site selection necessitates comprehensive consideration of multidimensional constraint conditions. The current analysis, based solely on elevation features, presents the following limitations:

- Unidimensionality of Features: The algorithm matches solely based on elevation features, without integrating critical engineering parameters such as transportation accessibility, hydrological distribution, and geological stability. Deeper analysis revealed that candidate regions 9 and 19 were traversed by existing roads, while region 12 overlapped with rivers by more than 35%. Despite their high terrain conformity, these regions are unsuitable for constructing large radio telescopes.

- Single-Scale Analysis: The experiment employed only an grid (720 m × 720 m) as the template scale, without considering multi-scale fusion analysis, potentially leading to insufficient assessment of terrain stability over larger areas. In practical engineering, the terrain characteristics of the broader area surrounding FAST similarly exert significant influence on engineering stability and electromagnetic environment.

Figure 5.

Some of the top 20 representative areas are similar to the FAST construction site. (a) FAST. (b) area 2. (c) area 5. (d) area 8. (e) area 9. (f) area 10. (g) area 12. (h) area 14. (i) area 16. (j) area 19.

This experiment validated the proposed algorithm’s capability to precisely identify specific spatial patterns within large-scale terrain data. In the FAST radio telescope site selection case study, the algorithm efficiently screened candidate regions meeting the “high periphery, low center” bowl-shaped terrain requirements, providing robust data support for preliminary site selection. Quantitative analysis of key indicators such as similarity scores, peripheral elevation differences, and depression diameters demonstrated high congruence between algorithm-identified candidate regions and engineering requirements.

The case study highlights that in practical engineering applications, our algorithm should function as a pre-filtering component within a larger Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) framework. This framework is necessary because structural similarity alone is insufficient; comprehensive evaluation requires integrating other specialized assessments, such as hydrology, geology, and accessibility. Future work will focus on integrating our ring vector method with diverse geographic information data to construct a formal, integrated evaluation system, thereby maximizing its application value in complex site selection tasks.

5.3.3. Experiment 3

WiFi distribution and Points of Interest (POI) distribution effectively reflect urban spatial structure characteristics and social activity patterns, particularly spatial features related to population mobility, commercial activities, and urban functional layout. This experiment aims to validate the proposed algorithm’s generalization capability and application potential in multi-type urban data analysis, with specific objectives including:

- Searching for regions with the highest similarity within Beijing’s Fourth Ring Road based on WiFi access points and POI distribution data, using the same target area.

- Comparing matching results from both data sources, analyzing their spatial overlap and differences.

- Evaluating the algorithm’s practical value in identifying urban functional zones and its implications for urban planning.

This study divided the area within Beijing’s Fourth Ring Road into a 200 m × 200 m grid network (totaling grid cells), with each cell covering approximately 40,000 square meters, suitable for block-level spatial analysis. Two types of spatial distribution feature matrices were constructed:

- WiFi Density Matrix , where , with representing the number of WiFi access points within grid cell , reflecting regional human activity intensity and real-time population density.

- POI Density Matrix , where , with representing the count of various POI categories within grid cell , reflecting regional infrastructure distribution and functional attributes.

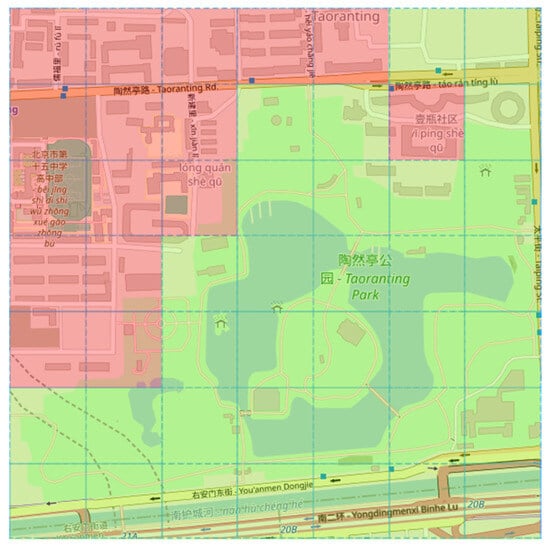

The study selected Taoranting Park and its northwestern region as the template area, as shown in Figure 6. This region combines green space (low density) and residential/commercial mixed areas (medium-high density), displaying a distinct “dense on one side, sparse on the other” spatial distribution pattern, making it suitable as a representative sample of mixed functional zones.

Figure 6.

Map of Taoranting Park and its northwestern region (the template). Red and green overlays highlight the high-density (built-up) and low-density (park) areas, respectively. The overlaid grid on each map represents cells.

Applying the proposed algorithm, the top-10 similar regions were identified in both the WiFi density matrix and POI density matrix, denoted as sets and . Through qualitative and quantitative comparative analysis of matching results from both data sources, the algorithm’s effectiveness in capturing urban spatial structure characteristics was evaluated, with particular attention to its identification capabilities across different spatial orientations.

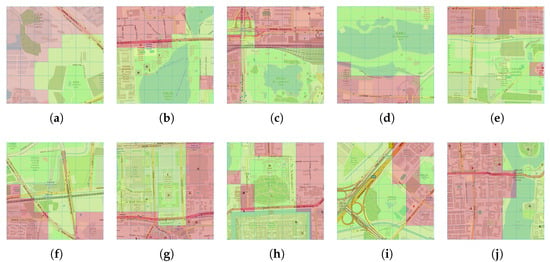

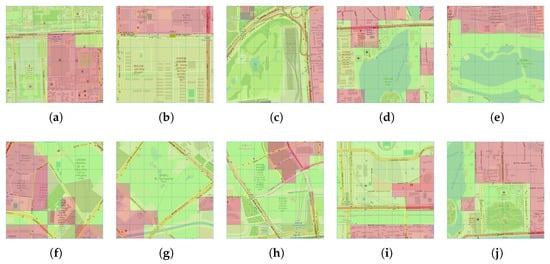

The algorithm identified “half-dense half-sparse” distribution patterns similar to the target area (Taoranting Park and surroundings) in both the WiFi density matrix (Figure 7) and the POI density matrix (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

TOP-10 matching results of Taoranting area on WIFI dataset. Red and green overlays highlight the corresponding high-density and low-density areas in each matched region. The overlaid grid on each map represents cells. (a) W1. (b) W2. (c) W3. (d) W4. (e) W5. (f) W6. (g) W7. (h) W8. (i) W9. (j) W10.

Figure 8.

TOP-10 matching results of Taoranting area on POI dataset. Red and green overlays highlight the corresponding high-density and low-density areas in each matched region. The overlaid grid on each map represents cells. (a) P1. (b) P2. (c) P3. (d) P4. (e) P5. (f) P6. (g) P7. (h) P8. (i) P9. (j) P10.

In the WiFi dataset matching results, all top 10 regions exhibited the typical “dense on one side, sparse on the other” distribution characteristics, primarily including:

- Chaoyang Park Fenghuayuan and its northwestern region (W1): sparse WiFi in the park area, dense WiFi in surrounding residential areas.

- Beihai Park and its northern surrounding area (W2): sparse WiFi distribution within the park, dense WiFi distribution in northern commercial and residential areas.

- Lianhuachi Park and its western and northern regions (W3): sparse WiFi in the park and railway areas, dense WiFi in surrounding schools and residential areas.

- Jingshan Park north of the Forbidden City and surrounding areas (W8): sparse in the park area, dense WiFi in the eastern side.

- Zhongnanhai and its western region (W10): Zhongnanhai’s river area has sparse WiFi, while the western downtown residential area has dense WiFi.

In the POI dataset matching results, the top 10 regions similarly reflected “dense on one side” distribution characteristics, primarily including:

- South of the Forbidden City and around Tiananmen Square (P1): sparse POI in the northern Forbidden City, more POI around southern Tiananmen Square and the National Museum.

- Wanliu Golf Course and its eastern region (P3): sparse POI in the golf course, dense POI in eastern residential areas.

- Yuyuantan Park and its northern region (P5): sparse POI in the park area, dense POI in northern residential areas.

- Taiyangong Sports and Leisure Park and its southwestern region (P6): sparse POI in the large park area, dense POI in the southwest with residential areas, schools, and companies.

- Beihai Park, Jingshan Park, and their surroundings (P10): fewer POI in Beihai Park and Jingshan Park, more POI in northeastern residential and commercial areas.

These matching results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm effectively captures functional zone differences in urban spaces, with significant advantages in identifying typical mixed functional zones such as “ecological-residential” and “park-commercial” areas.

By comparing the spatial directional distribution of the target area with the matching results, we further validated the algorithm’s advantages in rotational invariance. The Taoranting area exhibits a distinct directional distribution of “dense northwest, sparse southeast.” In the matching results, some regions displayed spatial orientations different from the template:

- WiFi matching region W6 shows sparse northwest and dense southeast distribution, opposite to the template area; W9 exhibits “northeast-southwest” density gradient distribution; W4, W5, W7, and W8 all display “north-south” density gradient distribution; W10 shows an “east-west” distribution pattern.

- POI matching region P1 has its dense area in the southeast, opposite to the template; P2 and P5 display “north-south” density gradient distribution; P3 and P10 show “east-west” distribution trends; P6 and P7 exhibit “northeast-southwest” density gradient distribution.

Despite these directional differences, the algorithm dynamically adjusts the starting point of ring vector traversal through maximum value point positioning, enabling the generated feature vectors to maintain high similarity. This characteristic makes the algorithm applicable to natural urban data distribution without requiring preset directional constraints.

Both WiFi and POI data reflect regional population density distribution to some extent, and the algorithm captured the spatial coupling between the two data types:

- Jingshan Park area (ID: W8/P10) was selected as a high-similarity area by both WiFi and POI models, where the park area forms a low-density zone while surrounding commercial clusters form high-density zones, perfectly reproducing the mixed functional features of the template.

- Beihai Park area (W2/P4): displays north-south distribution in both WiFi and POI distribution patterns, with sparse WiFi and POI distribution in the southern park area and dense WiFi and POI distribution in northern commercial and residential areas.

- Yuyuantan Park area (ID: W4/P5) exhibits “north-south” density gradients in both data sources, reflecting the typical functional distribution of park-residential areas.

This spatial coupling of multi-type data verifies the algorithm’s effectiveness and stability in identifying urban functional zones.