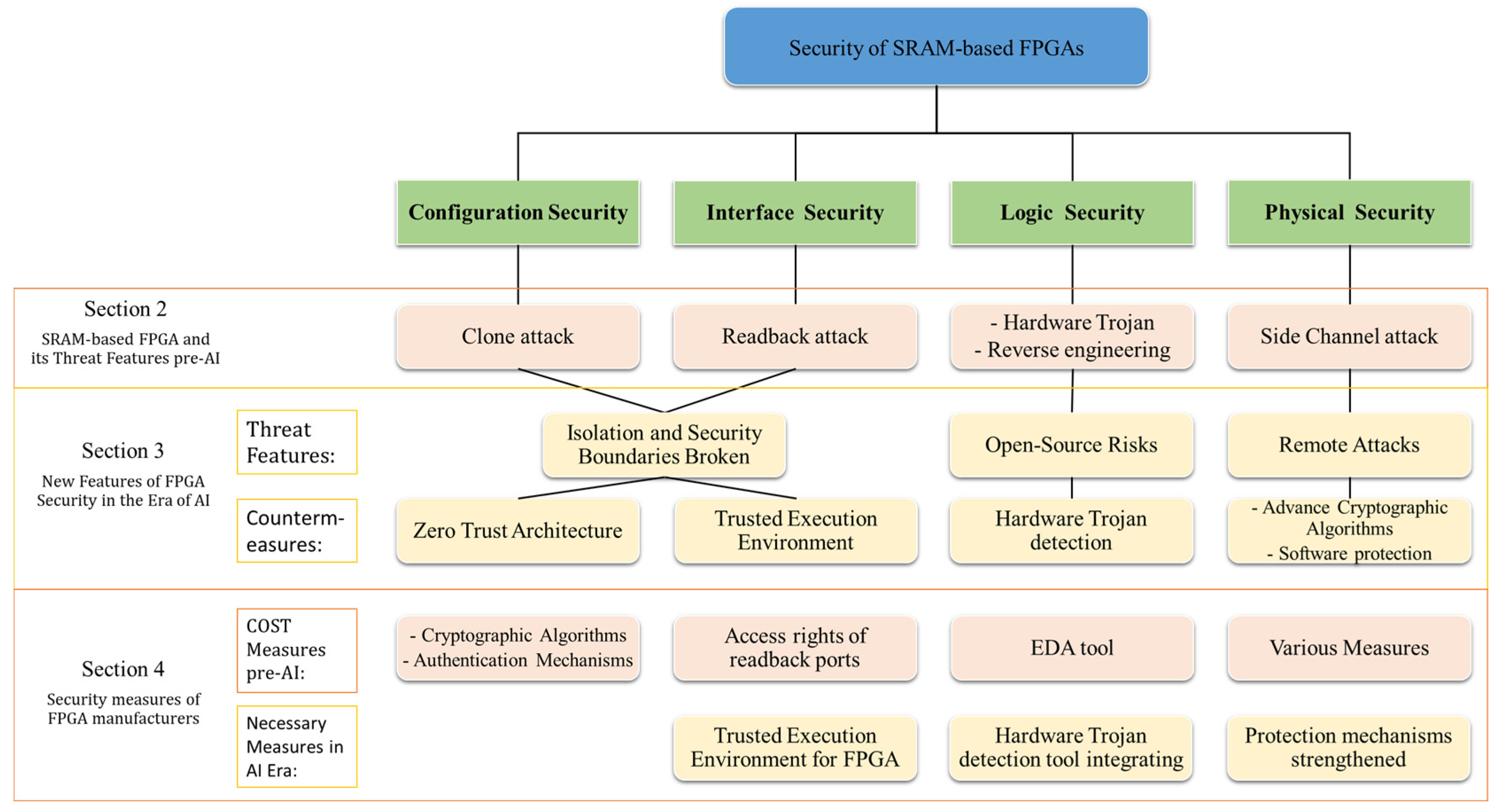

Research on the Security of SRAM-Based FPGAs in the Era of Artificial Intelligence

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Starting from the impacts of AI on aspects such as the architecture of FPGA chips, development methods, and application models, we comprehensively summarize the new characteristics of FPGA security in the AI era, including threat features and potential countermeasures.

- We summarize the protective measures used in COTS FPGA products, and propose a new perspective on the involvement of FPGA manufacturers in FPGA security. Finally, we outline the necessary future measures recommended for implementation by FPGA manufacturers.

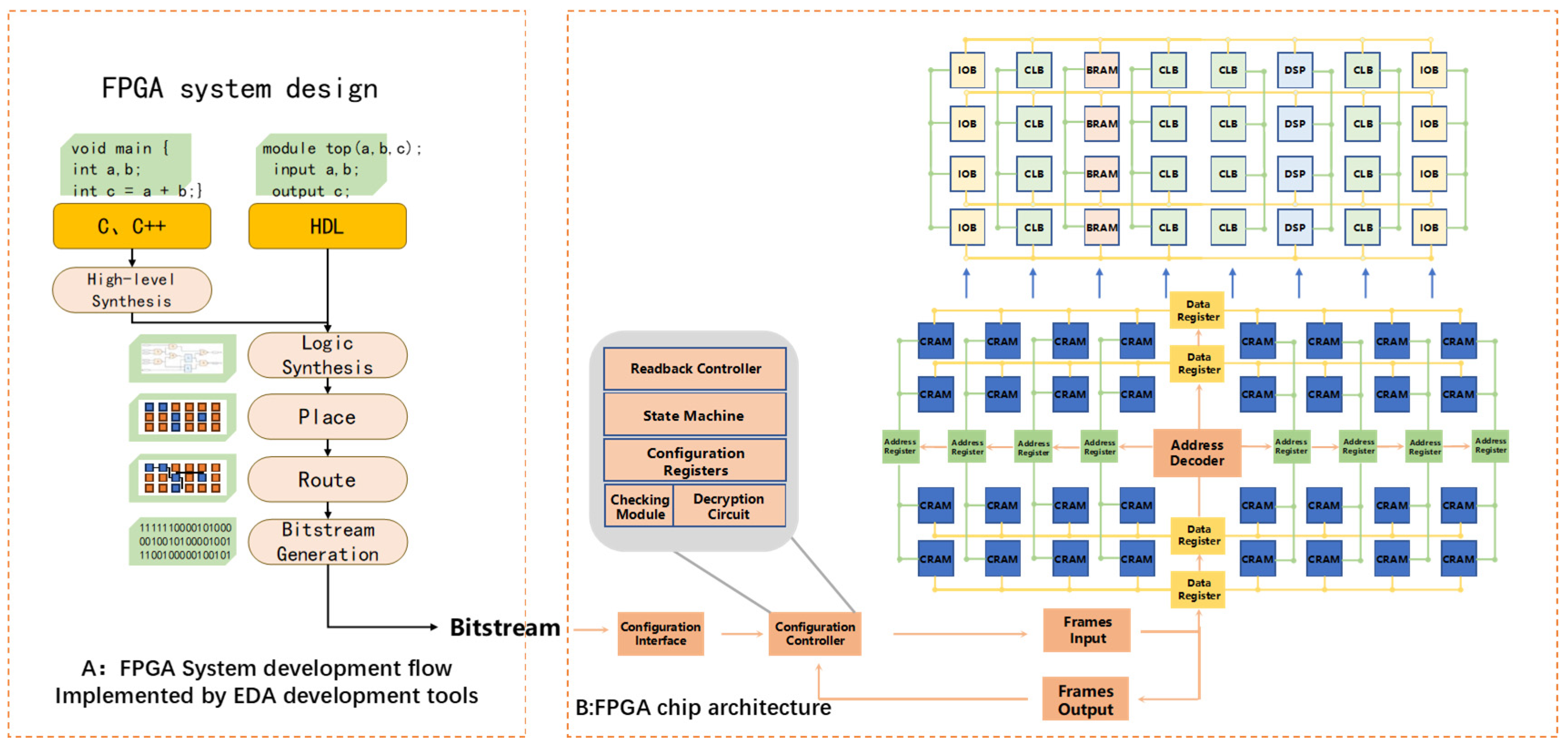

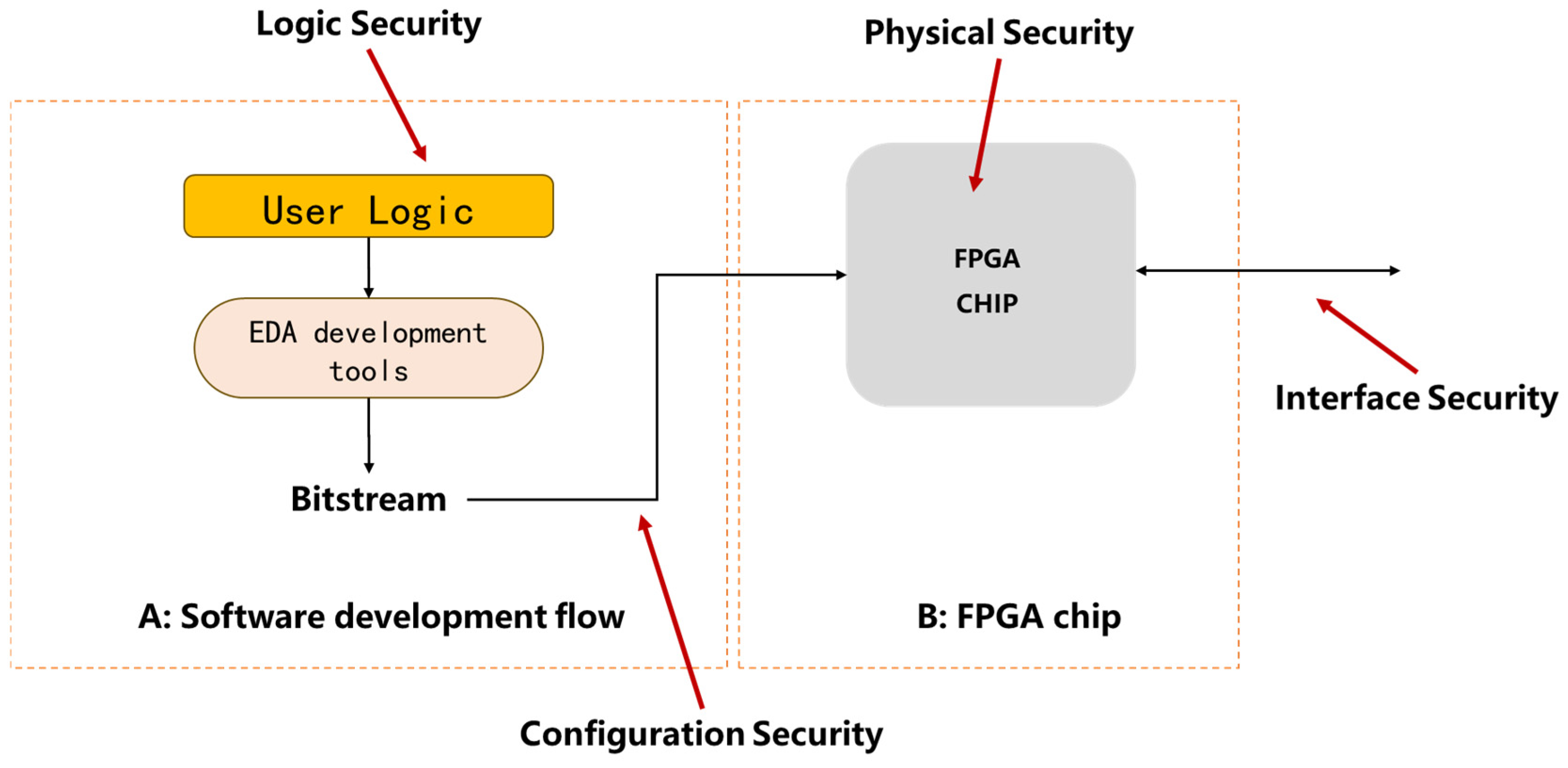

2. SRAM-Based FPGA and Its Threat Features Pre-AI

2.1. SRAM-Based FPGA and Development Process

2.2. The Taxonomy of Threats and Main Security Threats Pre-AI

2.2.1. Configuration Security

2.2.2. Interface Security

2.2.3. Logic Security

2.2.4. Physical Security

2.2.5. Protection Measures

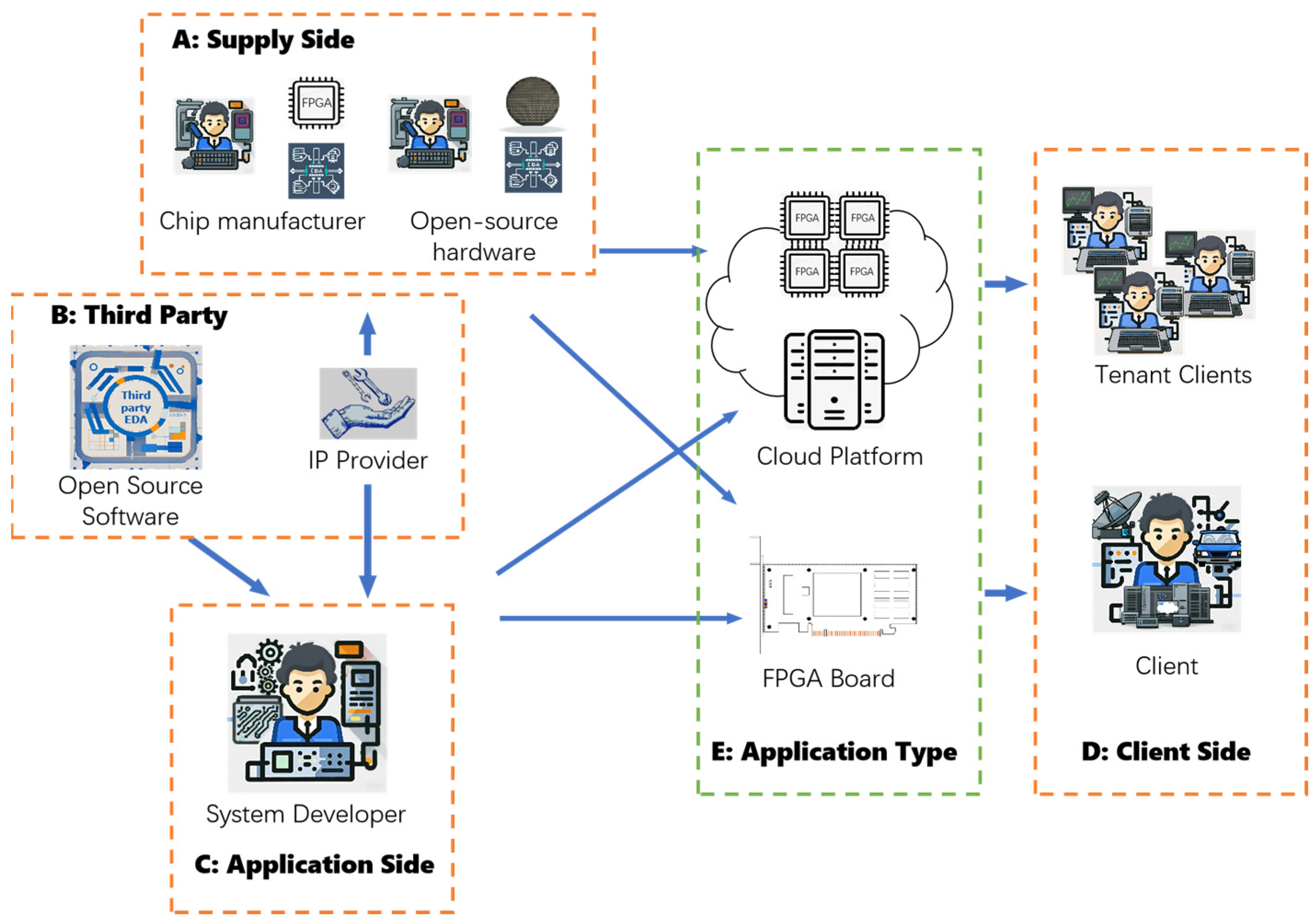

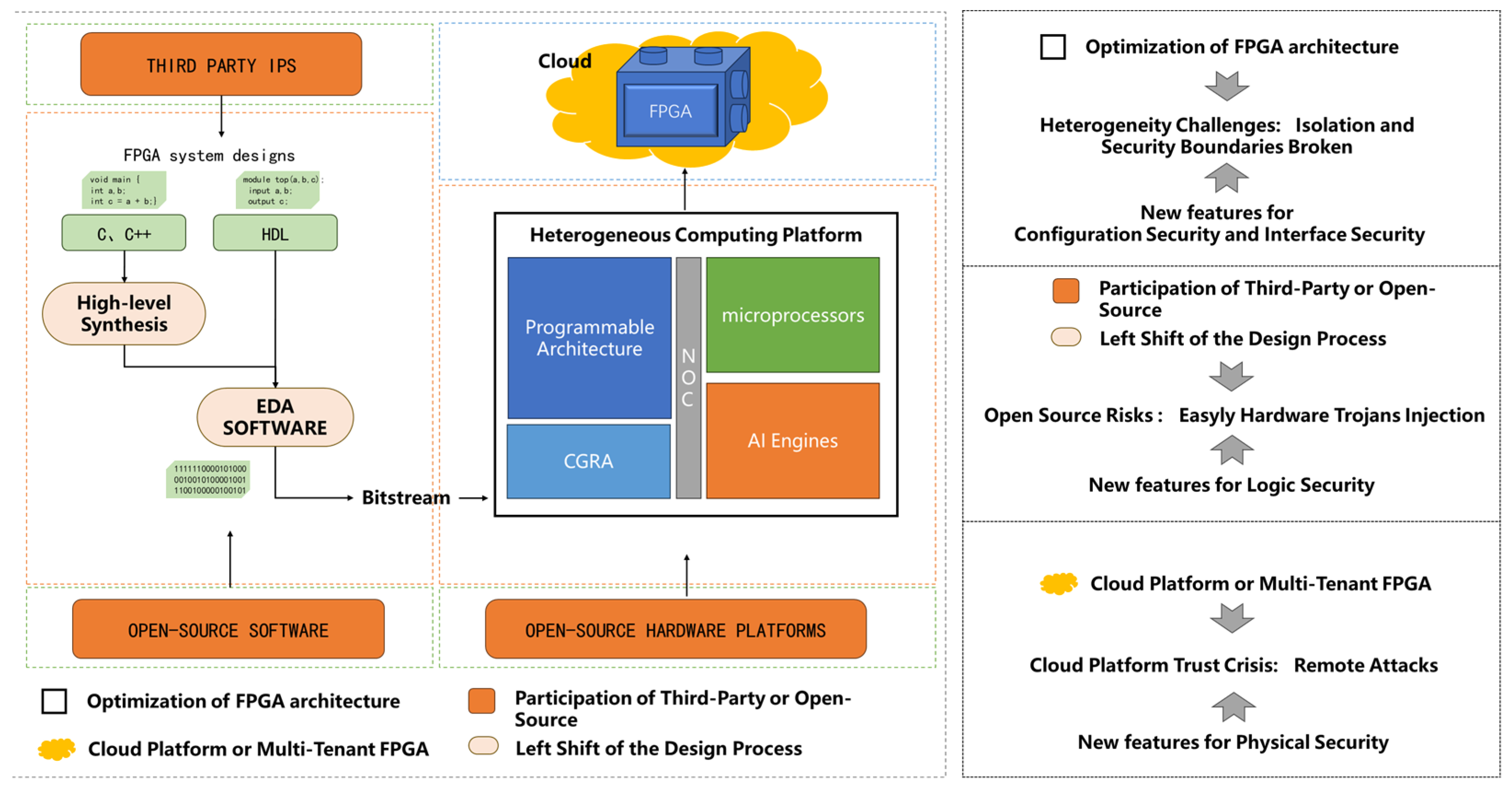

3. New Features of FPGA Security in the Era of AI

3.1. Changes in Architecture and Applications of FPGAs

3.1.1. Optimization of FPGA Architecture

3.1.2. Agilization of the Design Process

3.1.3. Alteration of Market Model

- Supply Side: Suppliers are the core force in the FPGA market and responsible for the research, development, production, and sales of FPGA products and development EDA tools.

- Third-Party Providers: With the growth of the open-source community, third-party IP cores and open-source EDA development software have emerged, presenting more options to application developers.

- Client Side: Clients purchase FPGA-based solutions for specific requirements.

3.2. FPGA Security in the Era of AI

3.2.1. Heterogeneity Challenges

3.2.2. Open-Source Risks

3.2.3. Cloud Platform Remote Attacks

4. Security Measures of FPGA Manufacturers

4.1. Traditional Security Measures of COTS FPGAs

4.1.1. Resist Configuration Security Threats

4.1.2. Resist Interface Security Threats

4.1.3. Resist Physical Security Threats

4.1.4. Resist Logic Security Threats

4.2. Securing the AI Era: Necessary Measures

4.2.1. Trusted Execution Environment Upgrade

4.2.2. Hardware Trojan Detection Tools

4.2.3. Side-Channel Protection Mechanisms

5. Experiments

5.1. Hardware Trojan Detection Experiments

5.1.1. Dataset and Partitioning

5.1.2. Feature Extraction and Graph Construction

5.1.3. GraphSMOTE Balancing

5.1.4. GCN-Based Classification and Training Details

5.1.5. Evaluation Metrics and Baselines

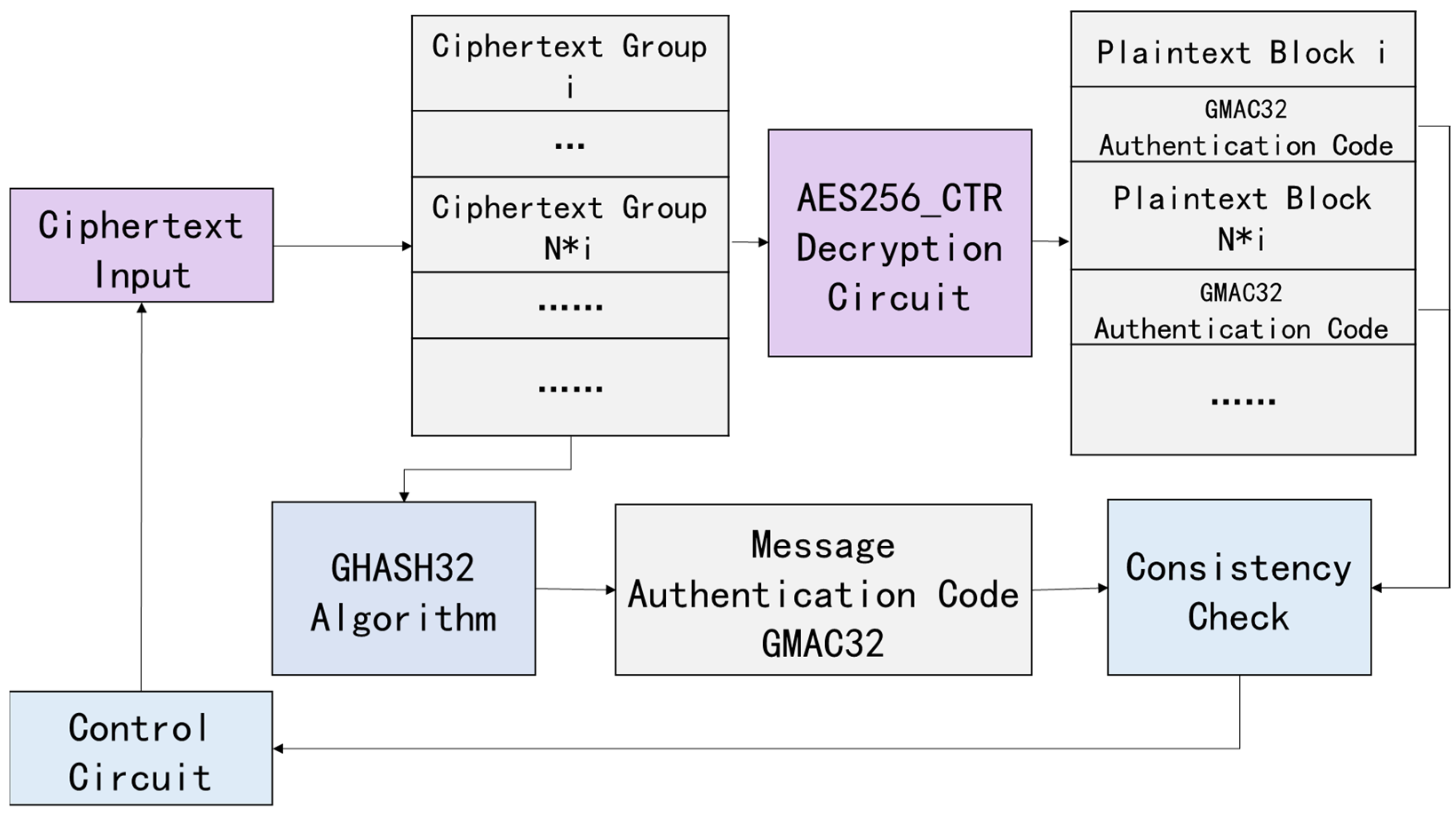

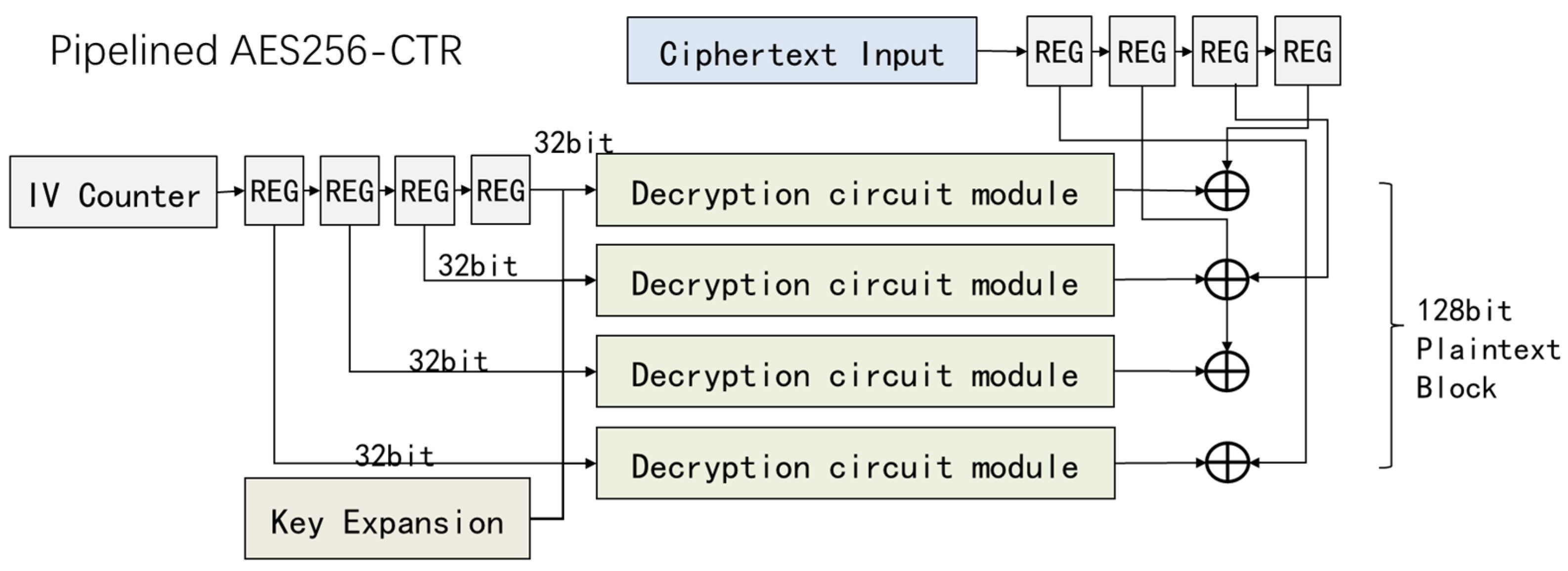

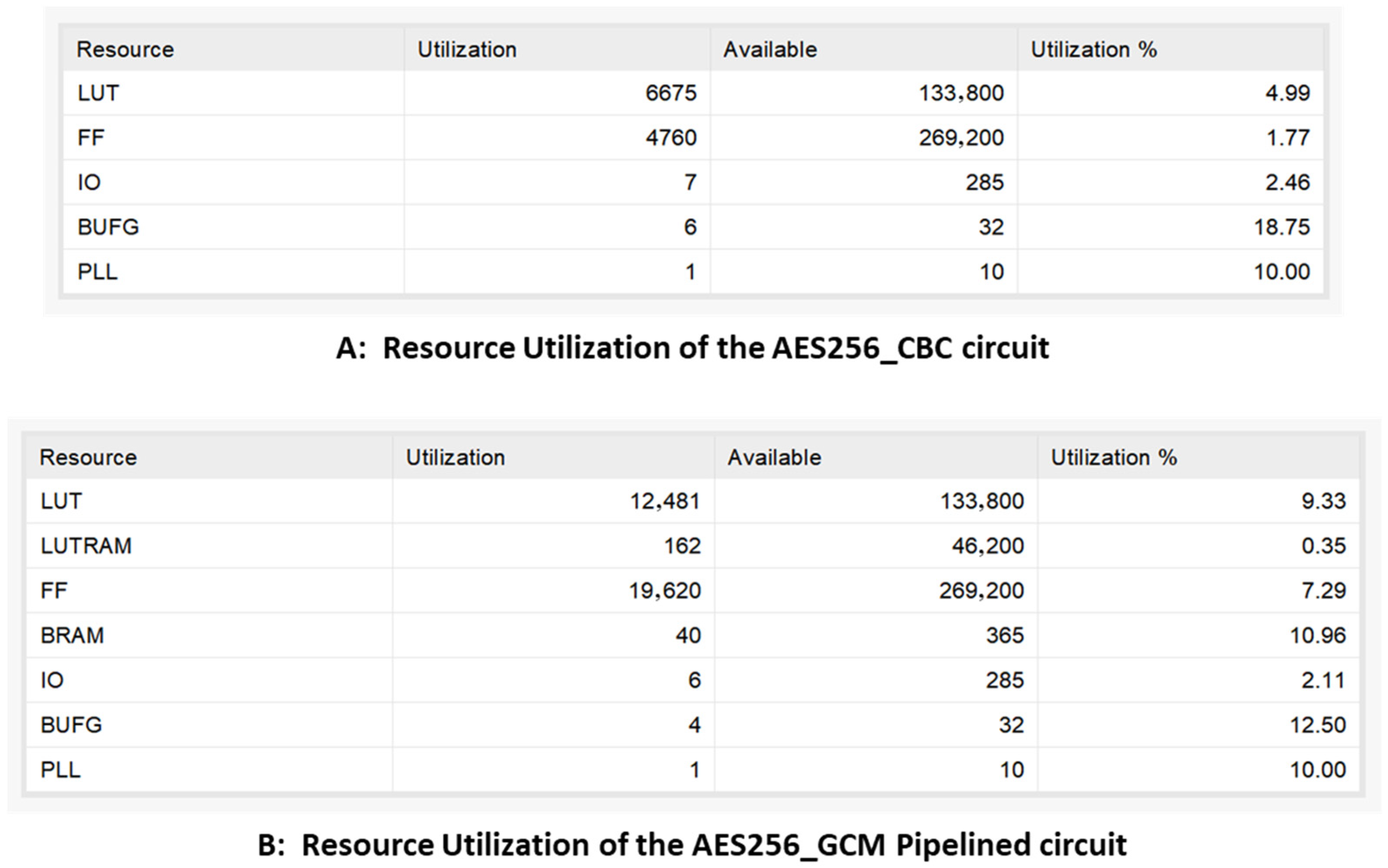

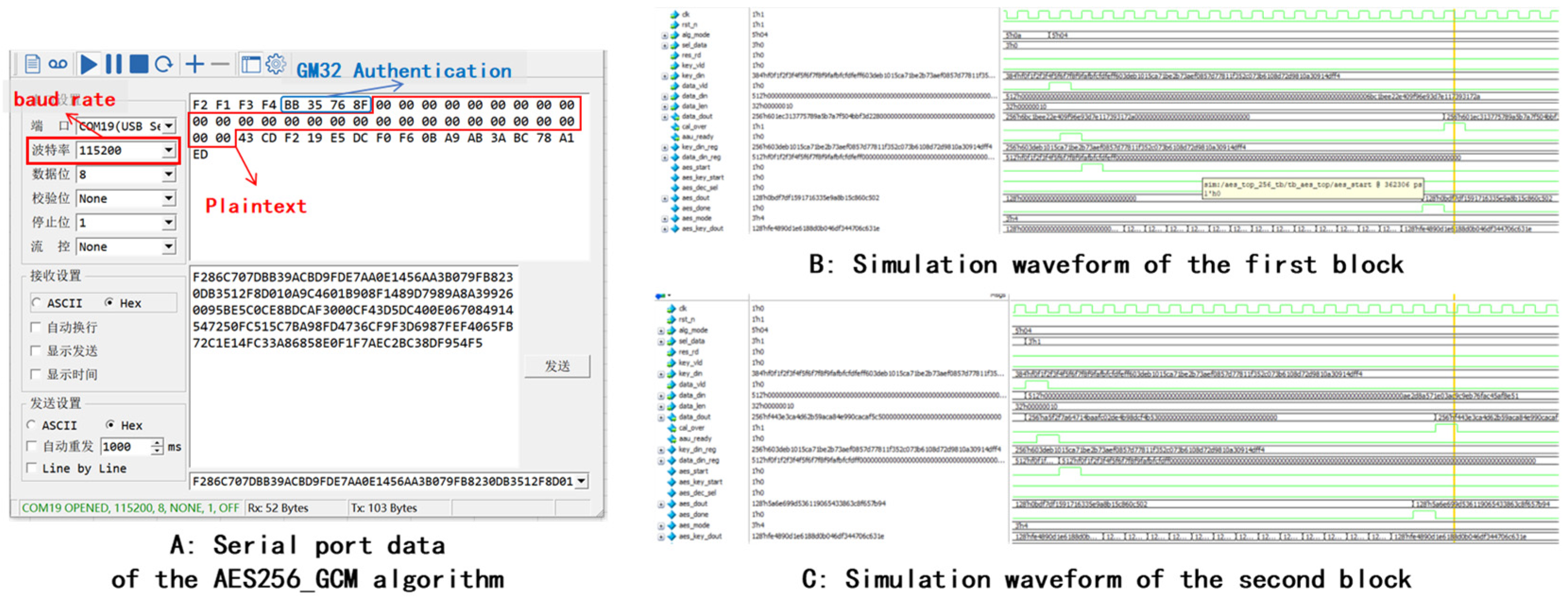

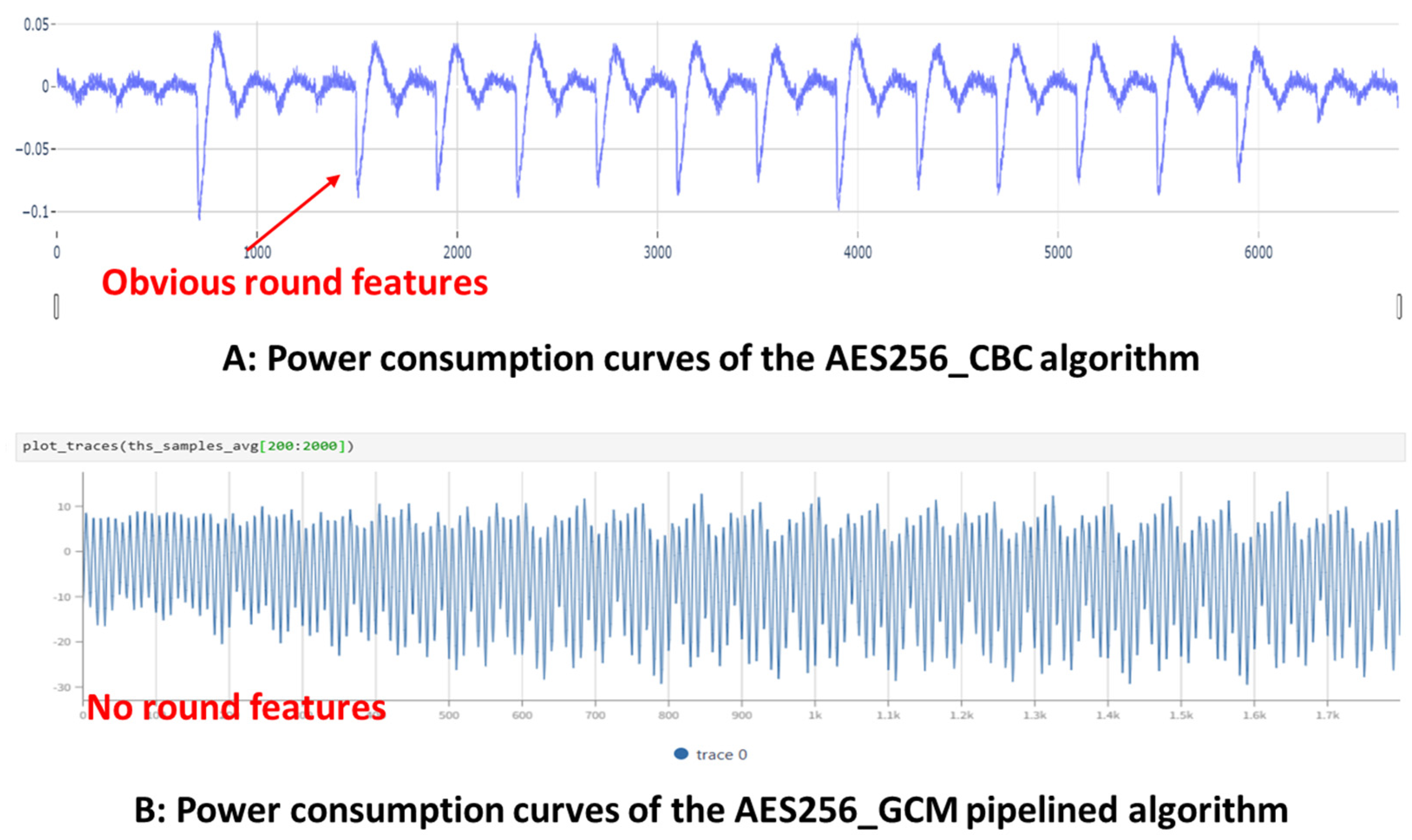

5.2. Side-Channel Evaluation of AES-CTR-GCM Decryption

- (1)

- A conventional AES-256 implementation in CBC mode;

- (2)

- The AES256_CCM pipelined design proposed in [193].

5.2.1. Experimental Setup

5.2.2. Attack Method

5.2.3. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, Y.; Kuppannagari, S.; Prasanna, V. Accelerating Proximal Policy Optimization on CPU-FPGA Heterogeneous Platforms. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 28th Annual International Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing Machines (FCCM), Fayetteville, AR, USA, 3–6 May 2020; pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimberger, S. A reprogrammable gate array and applications. Proc. IEEE 1993, 81, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMD Solutions for Aerospace and Defense. 2025. Available online: https://www.xilinx.com/applications/aerospace-and-defense.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wen, Z.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H. 300 Thousand Gates Single Event Effect Hardened SRAM-based FPGA for Space Application (Abstract Only). In Proceedings of the 2015 ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA′15); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimberger, S.M. Three Ages of FPGAs: A Retrospective on the First Thirty Years of FPGA Technology. Proc. IEEE 2015, 103, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XILINX. VIRTEX UltraScale+ VU19P FPGA Product Brief. 2020. Available online: https://www.xilinx.com/content/dam/xilinx/publications/product-briefs/virtex-ultrascale-plus-vu19pproduct-brief.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- INTEL. Intel® Stratix® 10 GX 10M FPGA Product Specifications. 2020. Available online: https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/products/sku/210290/intel-stratix-10-gx-10mfpga/specifications.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Duncan, A.; Rahman, F.; Lukefahr, A.; Farahmandi, F.; Tehranipoor, M. FPGA Bitstream Security: A Day in the Life. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Test Conference (ITC), Washington, DC, USA, 9–15 November 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qu, G. Recent Attacks and Defenses on FPGA-based Systems. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2019, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, X. A Survey on Machine Learning Against Hardware Trojan Attacks: Recent Advances and Challenges. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 10796–10826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, J. Rethinking FPGA Security in the New Era of Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2020 21st International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 25–26 March 2020; pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, F.; Verbauwhede, I. Trust in FPGA-accelerated Cloud Computing. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matas, K.; La, T.; Grunchevski, N.; Pham, K.; Koch, D. Invited Tutorial: FPGA Hardware Security for Datacenters and Beyond. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA′20); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkavilli, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Q. New Security Threats on FPGAs: From FPGA Design Tools Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), Tampa, FL, USA, 7–9 July 2021; pp. 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessouky, G.; Sadeghi, A.-R.; Zeitouni, S. SoK: Secure FPGA Multi-Tenancy in the Cloud: Challenges and Opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), Vienna, Austria, 6–10 September 2021; pp. 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Wang, W.; Luo, Y.; Xu, X. A Survey of Recent Attacks and Mitigation on FPGA Systems. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), Tampa, FL, USA, 7–9 July 2021; pp. 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Mishra, P. A Survey on Hardware Vulnerability Analysis Using Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 49508–49527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrahis, L.; Patnaik, S.; Shafique, M.; Sinanoglu, O. Embracing Graph Neural Networks for Hardware Security. In Proceedings of the 41st IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD′22); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, A.; Asfia, Y.; Khawaja, S.G. Power profiling-based side-channel attacks on FPGA and Countermeasures: A survey. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Digital Futures and Transformative Technologies (ICoDT2), Rawalpindi, Pakistan, 24–26 May 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghibijouybari, H.; Koruyeh, E.M.; Abu-Ghazaleh, N. Microarchitectural Attacks in Heterogeneous Systems: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, D.G.; Lenders, V.; Stojilović, M. Electrical-Level Attacks on CPUs, FPGAs, and GPUs: Survey and Implications in the Heterogeneous Era. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köylü, T.Ç.; Reinbrecht, C.R.W.; Gebregiorgis, A.; Hamdioui, S.; Taouil, M. A Survey on Machine Learning in Hardware Security. J. Emerg. Technol. Comput. Syst. 2023, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koblah, D.S.; Acharya, R.Y.; Capecci, D.; Dizon-Paradis, O.P.; Tajik, S.; Ganji, F.; Woodard, D.L.; Forte, D. A Survey and Perspective on Artificial Intelligence for Security-Aware Electronic Design Automation. ACM Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Syst. 2023, 28, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, A.; Chouinard, J.-Y.; Fortier, P.; Miled, A. A Survey on FPGA Cybersecurity Design Strategies. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2023, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero-Montalvo, P.D.; István, Z.; Hernandez, W. A Survey of Trusted Computing Solutions Using FPGAs. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 31583–31593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erata, F.; Deng, S.; Zaghloul, F.; Xiong, W.; Demir, O.; Szefer, J. Survey of Approaches and Techniques for Security Verification of Computer Systems. J. Emerg. Technol. Comput. Syst. 2023, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Fu, Y.; Yi, W.; Yang, J.; Cao, J.; Dong, Z.; Xie, F.; Li, H. Vulnerabilities and Security Patches Detection in OSS: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abideen, Z.U.; Gokulanathan, S.; Aljafar, M.J.; Pagliarini, S. An overview of FPGA-inspired obfuscation techniques. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.K.; Kealoha, M.P.; Mbongue, J.M.; Saha, S.K.; Tchinda, E.N.; Mbua, P.E.; Bobda, C. Multi-Tenant Cloud FPGA: A Survey on Security, Trust, and Privacy. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2025, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Sun, H.; Sun, J.; Xu, H. A Multi-mode Configuration Circuit Design for SoPC. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 6th Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), Beijing, China, 3–5 October 2022; pp. 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, J.; Pang, Y.; Du, Z. A Survey on FPGA Electronic Design Automation Technology Based on Machine Learning. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2023, 45, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Du, B.; Sterpone, L.; Codinachs, D.M. A new EDA flow for the mitigation of SEUs in dynamic reconfigurable FPGAs. In Proceedings of the 2016 21th IEEE European Test Symposium (ETS), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 23–27 May 2016; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollinger, T.; Guajardo, J.; Paar, C. Security on FPGAs: State-of-the-art implementations and attacks. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2004, 3, 534–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saar, D. Volatile FPGA Design Security—A Survey. Available online: https://saardrimer.com/sd410/papers/fpga_security.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2008).

- Actel. Understanding Actel Antifuse Device Security. 2004. Available online: www.actel.com/documents/AntifuseSecurityWP.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Jiaojiao, T.; Min, X. MRUC Method for FPGA Configuration. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 3rd Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), Chongqing, China, 12–14 October 2018; pp. 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H. A highly-integrated wireless configuration circuit for FPGA chip. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Symposium on Integrated Circuits (ISIC), Singapore, 10–12 December 2014; pp. 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R. XAPP1292 Loading Partial Bitstreams Using TFTP. Available online: https://www.xilinx.com/member/forms/download/design-license.html?cid=472824&filename=xapp1292-loading-partial-bitstreams-using-tftp.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2016).

- Vliegen, J.; Mentens, N.; Verbauwhede, I. Secure, Remote, Dynamic Reconfiguration of FPGAs. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2014, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XAPP151, Virtex Series Configuration Architecture User Guide. Available online: https://docs.amd.com/v/u/en-US/xapp151 (accessed on 20 October 2004).

- Ender, M.; Moradi, A.; Paar, C. The Unpatchable Silicon: A Full Break of the Bitstream Encryption of Xilinx 7-Series FPGAs. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.13756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ender, M.; Leander, G.; Moradi, A.; Paar, C. A Cautionary Note on Protecting Xilinx’ UltraScale(+) Bitstream Encryption and Authentication Engine. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 30th Annual International Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing Machines (FCCM), New York, NY, USA, 15–18 May 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Note, J.-B.; Rannaud, É. From the bitstream to the netlist. Proc. FPGA 2008, 8, 264. [Google Scholar]

- Benz, F.; Seffrin, A.; Huss, S.A. BIL: A tool-chain for bitstream reverse-engineering. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Field Programmable Logic and Applications (FPL), Oslo, Norway, 29–31 August 2012; pp. 735–738. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L. Deriving an NCD file from an FPGA bitstream: Methodology, architecture and evaluation. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2013, 37, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, K.D.; Horta, E.; Koch, D. BITMAN: A tool and API for FPGA bitstream manipulations. In Proceedings of the Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), 2017, Lausanne, Switzerland, 27–31 March 2017; pp. 894–897. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.; Seo, Y.; Jang, J.; Cho, M.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Kwon, T. A bitstream reverse engineering tool for FPGA hardware trojan detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 2318–2320. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Tehranipoor, M.; Farahmandi, F. BitFREE: On significant speedup and security applications of FPGA bitstream format reverse engineering. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE European Test Symposium (ETS), Venezia, Italy, 22–26 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- McKendrick, R.; Simpson, C.; Nelson, B.; Goeders, J. Leveraging FPGA primitives to improve word reconstruction during netlist reverse engineering. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Field-Programmable Technology (ICFPT), Hong Kong, 5–9 December 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Perumalla, A.; Stowasser, H.; Emmert, J.M. Fast FPGA Reverse Engineering for Hardware Metering and Fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the NAECON 2023-IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference, Dayton, OH, USA, 28–31 August 2023; pp. 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, M.; Lee, J.; Jung, E.; Kim, Y.H.; Cho, K. Extract LUT logics from a downloaded bitstream data in FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Florence, Italy, 27–30 May 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kashani, S.; Emami, M.; Larus, J.R. Bitfiltrator: A general approach for reverse-engineering Xilinx bitstream formats. In Proceedings of the 2022 32nd International Conference on Field-Programmable Logic and Applications (FPL), Belfast, UK, 29 August–2 September 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Im, N.; Choi, S.; Yoo, H. S-Box attack using FPGA reverse engineering for lightweight cryptography. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 25165–25180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Yeo, J.; Yoo, H. Extraction of ROM Data from Bitstream in Xilinx FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2020 International SoC Design Conference (ISOCC), Yeosu, Republic of Korea, 21–24 October 2020; pp. 97–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z. A reverse engineering-based framework assisting hardware Trojan detection for encrypted Ips. In Proceedings of the 2018 Eighth International Conference on Instrumentation & Measurement, Computer, Communication and Control (IMCCC), Harbin, China, 19–21 July 2018; pp. 1649–1652. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, D.; Baktir, S.; Karakoyunlu, D. Trojan Detection using IC Fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SSP’07), Berkeley, CA, USA, 20–23 May 2007; pp. 296–310. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten, A.; Steffen, M.; Clausman, M.; Zambreno, J. A case study in hardware Trojan design and implementation. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2011, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yuan, F.; Xu, Q. DeTrust: Defeating hardware trust verification with stealthy implicitly-triggered hardware Trojans. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS′14); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Giri, N.; Anandakumar, N.N. Design and Analysis of Hardware Trojan Threats in Reconfigurable Hardware. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Information Technology and Engineering (ic-ETITE), Vellore, India, 24–25 February 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhani, E.M.; Bossuet, L.; Aubert, A. The Security of ARM TrustZone in a FPGA-Based SoC. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2019, 68, 1238–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ender, M.; Swierczynski, P.; Wallat, S.; Wilhelm, M.; Knopp, P.M.; Paar, C. Insights into the mind of a trojan designer: The challenge to integrate a trojan into the bitstream. In Proceedings of the 2019 24th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASP-DAC), Tokyo, Japan, 21–24 January 2019; pp. 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, R.S.; Saha, I.; Palchaudhuri, A.; Naik, G.K. Hardware trojan insertion by direct modification of FPGA configuration bitstream. IEEE Des. Test 2013, 30, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Njilla, L.; Kamhoua, C.A.; Yu, Q. Thwarting Security Threats from Malicious FPGA Tools with Novel FPGA-Oriented Moving Target Defense. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 2019, 27, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieg, C.; Wolf, C.; Jantsch, A. Malicious LUT: A Stealthy FPGA Trojan Injected and Triggered by the Design Flow. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD), Austin, TX, USA, 7–10 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Standaert, F.X.; van Oldeneel tot Oldenzeel, L.; Samyde, D.; Quisquater, J.J. Power analysis of FPGAs: How practical is the attack? In Proceedings of the Field Programmable Logic and Application: 13th International Conference, FPL 2003, Lisbon, Portugal, 2 September 2003; Proceedings 13; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 701–710. [Google Scholar]

- Archambeau, C.; Peeters, E.; Standaert, F.X.; Quisquater, J.J. Template attacks in principal subspaces. In Proceedings of the Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems-CHES 2006: 8th International Workshop, Yokohama, Japan, 10–13 October 2006; Proceedings 8; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar, N.; Mehrabi, M.A.; Kong, Y.; Anjum, A. Machine-learning-based side-channel evaluation of elliptic-curve cryptographic FPGA processor. Appl. Sci. 2018, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Suh, G.E. FPGA-based remote power side-channel attacks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, A.; Barenghi, A.; Kasper, T.; Paar, C. On the vulnerability of FPGA bitstream encryption against power analysis attacks: Extracting keys from xilinx Virtex-II FPGAs. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS′11); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, A.; Oswald, D.; Paar, C.; Swierczynski, P. Side-channel attacks on the bitstream encryption mechanism of Altera Stratix II: Facilitating black-box analysis using software reverse-engineering. In Proceedings of the ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA′13); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Swierczynski, P.; Moradi, A.; Oswald, D.; Paar, C. Physical Security Evaluation of the Bitstream Encryption Mechanism of Altera Stratix II and Stratix III FPGAs. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2014, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, A.; Schneider, T. Improved Side-Channel Analysis Attacks on Xilinx Bitstream Encryption of 5, 6, and 7 Series. In Constructive Side-Channel Analysis and Secure Design; Standaert, F.X., Oswald, E., Eds.; COSADE 2016; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettwer, B.; Leger, S.; Fennes, D.; Gehrer, S.; Güneysu, T. Side-channel analysis of the xilinx zynq ultrascale+ encryption engine. IACR Trans. Cryptogr. Hardw. Embed. Syst. 2021, 2021, 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian, T. Microchip Further Protects FPGA-based Designs with First Tool that Combats Major Industry Threat to System Security in the Field. Available online: https://www.microchip.com/en-us/about/news-releases/products/microchip-further-protects-fpga-based-designs-with-first-tool-th (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Using the Design Security Features in Intel® FPGAs, (intel.com). Available online: https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/docs/programmable/683269/current/using-the-design-security-features-in-fpgas.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Della Sala, R.; Bellizia, D.; Scotti, G. A Lightweight FPGA Compatible Weak-PUF Primitive Based on XOR Gates. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 2972–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PolarFire Family FPGA Security User Guide. 2025 Microchip Technology Inc. and Its Subsidiaries. DS60001726. Available online: https://www.microchip.com/content/dam/mchp/documents/FPGA/ProductDocuments/UserGuides/Microchip_PolarFire_FPGA_and_PolarFire_SoC_FPGA_Security_User_Guide_VA%20(2).pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Farahmand, F.; Sharif, M.U.; Briggs, K.; Gaj, K. A High-Speed Constant-Time Hardware Implementation of NTRUEncrypt SVES. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Field-Programmable Technology (FPT), Naha, Japan, 10–14 December 2018; pp. 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, R.; Zhao, W. FPGA based optimization for masked AES implementation. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE 54th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 7–10 August 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Pan, S.; Ma, H.; Gao, Y.; Song, X.; He, J.; Jin, Y. Side Channel Security Oriented Evaluation and Protection on Hardware Implementations of Kyber. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2023, 70, 5025–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amouri, E.; Bhasin, S.; Mathieu, Y.; Graba, T.; Danger, J.-L.; Mehrez, H. Balancing WDDL dual-rail logic in a tree-based FPGA to enhance physical security. In Proceedings of the 2014 24th International Conference on Field Programmable Logic and Applications (FPL), Munich, Germany, 2–4 September 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanshenas, S.; Betz, V. COFFE 2: Automatic Modelling and Optimization of Complex and Heterogeneous FPGA Architectures. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2019, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, E.; Rasoulinezhad, S.; Leong, P.H.W.; Wilton, S.J.E. FPGA Architecture Exploration for DNN Acceleration. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2022, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Shen, H.; Fan, J.; Xu, Y.; Huang, K. An All-digital Compute-in-memory FPGA Architecture for Deep Learning Acceleration. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2024, 17, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Zhou, H.; Wang, L. VIB: A Versatile Interconnection Block for FPGA Routing Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Field Programmable Technology (ICFPT), Yokohama, Japan, 12–14 December 2023; pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Rao, N.; Gore, G.; Tang, X. Architectural Exploration of Heterogeneous FPGAs for Performance Enhancement of ML Benchmarks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Asia Pacific Conference on Circuits and Systems (APCCAS), Hyderabad, India, 19–22 November 2023; pp. 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, Z.; Kumar, A. BioCare: An Energy-Efficient CGRA for Bio-Signal Processing at the Edge. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Daegu, Republic of Korea, 22–28 May 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Tan, C.; Agostini, N.B.; Li, A.; Tumeo, A.; Dave, N.; Geng, T. ML-CGRA: An Integrated Compilation Framework to Enable Efficient Machine Learning Acceleration on CGRAs. In Proceedings of the 2023 60th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 9–13 July 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, O.; Kamal, M.; Afzali-Kusha, A.; Pedram, M.; Shafique, M. X-CGRA: An Energy-Efficient Approximate Coarse-Grained Reconfigurable Architecture. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2020, 39, 2558–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.; Cao, J.; Zhaoa, D.; Jia, G.; Meng, Q. A Hardware and Software Task-Scheduling Framework Based on CPU+FPGA Heterogeneous Architecture in Edge Computing. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 148975–148988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Arikawa, Y.; Ito, T.; Morita, K.; Nemoto, N.; Miura, F.; Terada, K.; Teramoto, J.; Sakamoto, T. Communication-Efficient Distributed Deep Learning with GPU-FPGA Heterogeneous Computing. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium on High-Performance Interconnects (HOTI), Piscataway, NJ, USA, 19–21 August 2020; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M.; Anderson, E.; Ardalan, S.; Bhargava, P.; Buchbinder, S.; Davenport, M.L.; Fini, J.; Lu, H.; Li, C.; Meade, R.; et al. TeraPHY: A Chiplet Technology for Low-Power, High-Bandwidth In-Package Optical I/O. IEEE Micro 2020, 40, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvey, T.E.; Kaul, A.; Rajan, S.K.; Dasu, A.; Gutala, R.; Bakir, M.S. Microfluidic Cooling of a 14-nm 2.5-D FPGA With 3-D Printed Manifolds for High-Density Computing: Design Considerations, Fabrication, and Electrical Characterization. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 9, 2393–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Giacomin, E.; Chauviere, B.; Alacchi, A.; Gaillardon, P.-E. OpenFPGA: An Open-Source Framework for Agile Prototyping Customizable FPGAs. IEEE Micro 2020, 40, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.; Fuguet, C.; Million, D. Invited Paper: Open Source Heterogeneous Chiplet-Based Computing Architectures. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Conference On Computer Aided Design (ICCAD), Newark, NJ, USA, 27–31 October 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.L.; Dao, N.; Yu, J.; Koch, D. How to shrink my fpgas—Optimizing tile interfaces and the configuration logic in fabulous fpga fabrics. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays, FPGA′22; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wentzlaff, D. PRGA: An Open-Source FPGA Research and Prototyping Framework. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA′21); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Beidas, R.; Chacko, V.; Hsiao, H.; Ling, X.; Ragheb, O.; Wang, X.; Yu, T. CGRA-ME: An Open-Source Framework for CGRA Architecture and CAD Research: (Invited Paper). In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 32nd International Conference on Application-Specific Systems, Architectures and Processors (ASAP), Virtual, 7–9 July 2021; pp. 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Xie, C.; Li, A.; Barker, K.J.; Tumeo, A. OpenCGRA: An Open-Source Unified Framework for Modeling, Testing, and Evaluating CGRAs. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 38th International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD), Hartford, CT, USA, 18–21 October 2020; pp. 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F4PGA (Formerly SymbiFlow). Project X-Ray. 2018. Available online: https://prjxray.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Wolf, C.; Lasser, M. Project IceStorm. 2015. Available online: https://www.clifford.at/icestorm/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Python Productivity for Zynq. Available online: https://pynq.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Azzaz, M.S.; Maali, A.; Kaibou, R.; Kakouche, I.; Saad, M.; Hamil, H. FPGA HW/SW Codesign Approach for Real-time Image Processing Using HLS. In Proceedings of the 2020 1st International Conference on Communications, Control Systems and Signal Processing (CCSSP), El Oued, Algeria, 16–17 May 2020; pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Z. FracBNN: Accurate and FPGA-efficient binary neural networks with fractional activations. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA’21), Virtual, 28 February–2 March 2021; pp. 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.H.; Chi, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, C.H.; Zhou, Y.; Cong, J.; Zhang, Z. Hete roCL: A multi-paradigm programming infrastructure for software-defined reconfigurable computing. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA’19), Seaside, CA, USA, 24–26 February 2019; pp. 242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Q.; Kaul, A.; Pattanaik, N.K.D.; Pattanayak, P.; Pandurangan, V. Securing Applications of Large Language Models: A Shift-Left Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Electro Information Technology (eIT), Eau Claire, WI, USA, 30 May–1 June 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, A.X.; Zhang, F.; Chen, F. FPGA Resource Pooling in Cloud Computing. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2021, 9, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Hao, C.; Jeong, H.; Huang, J.; Chen, D. ScaleHLS: Achieving scalable high level synthesis through MLIR. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Languages, Tools, and Techniques for Accelerator Design (LATTE’21), Online, 15 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Elgammal, M.A.; Mohaghegh, A.; Shahrouz, S.G.; Mahmoudi, F.; Koşar, F.; Talaei, K.; Fife, J.; Khadivi, D.; Murray, K.; Boutros, A.; et al. VTR 9: Open-Source CAD for Fabric and Beyond FPGA Architecture Exploration. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2025, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Hung, E.; Wolf, C.; Bazanski, S.; Gisselquist, D.; Milanovic, M. Yosys+nextpnr: An Open Source Framework from Verilog to Bitstream for Commercial FPGAs. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 27th Annual International Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing Machines (FCCM), San Diego, CA, USA, 28 April–1 May 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, M.M.; Réal, M.M.; Pelcat, M.; Besnier, P. Bus Electrocardiogram: Vulnerability of SoC-FPGA Internal AXI Bus to Electromagnetic Side-Channel Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC Europe, Krakow, Poland, 4–8 September 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giechaskiel, I.; Rasmussen, K.B.; Szefer, J. C3APSULe: Cross-FPGA Covert-Channel Attacks through Power Supply Unit Leakage. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–21 May 2020; pp. 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.; Krautter, J.; Gnad, D.; Gruber, M.; Sigl, G.; Tahoori, M. FPGANeedle: Precise Remote Fault Attacks from FPGA to CPU. In Proceedings of the 28th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASPDAC′23); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, Z.; Tiemann, T.; Moghimi, D.; Custodio, E.; Eisenbarth, T.; Sunar, B. JackHammer: Efficient Rowhammer on Heterogeneous FPGA-CPU Platforms. IACR Trans. Cryptogr. Hardw. Embed. Syst. 2020, 2020, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Wang, D.; Lyu, Y.; Tian, R.; Wang, C.; Qu, G. VoltJockey: A New Dynamic Voltage Scaling-Based Fault Injection Attack on Intel SGX. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2021, 40, 1130–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, H. Hardware/Software Co-Assurance for the Rust Programming Language Applied to Zero Trust Architecture Development. Ada Lett. 2023, 42, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Niraula, A.; Bhattarai, H.; Niamat, M. A Zero Trust Architecture employing Blockchain and Ring Oscillator Physical Unclonable Function for Internet-of-Things. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Electro Information Technology (eIT), Eau Claire, WI, USA, 30 May–1 June 2024; pp. 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Hazari, N.A.; Niamat, M.Y. A Zero Trust-Based Framework Employing Blockchain Technology and Ring Oscillator Physical Unclonable Functions for Security of Field Programmable Gate Array Supply Chain. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 89322–89338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Nam, K.; Jeon, S.; Cho, Y.; Paek, Y. MeetGo: A Trusted Execution Environment for Remote Applications on FPGA. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 51313–51324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Su, L.; Gu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Guan, Y.; Niu, D.; Gao, M.; Xie, Y.; et al. Salus: A Practical Trusted Execution Environment for CPU-FPGA Heterogeneous Cloud Platforms. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Volume 4 (ASPLOS′24); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Gao, M.; Kozyrakis, C. ShEF: Shielded enclaves for cloud FPGAs. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems (ASPLOS′22); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1070–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Hou, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Cao, J.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ying, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Enabling Rack-scale Confidential Computing using Heterogeneous Trusted Execution Environment. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–21 May 2020; pp. 1450–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, E.; Feng, D.; Du, D.; Xia, Y.; Zheng, W.; Zhao, S.; Chen, H. SIOPMP: Scalable and Efficient I/O Protection for TEEs. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Volume 2 (ASPLOS′24); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chen, Y.; Wong, W.-F.; Chang, E.-C. T-Edge: Trusted Heterogeneous Edge Computing. In Proceedings of the 2024 Annual Computer Security Applications Conference (ACSAC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 9–13 December 2024; pp. 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbongue, J.M.; Saha, S.K.; Bobda, C. A Security Architecture for Domain Isolation in Multi-Tenant Cloud FPGAs. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), Tampa, FL, USA, 7–9 July 2021; pp. 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallat, S.; Albartus, N.; Becker, S.; Hoffmann, M.; Ender, M.; Fyrbiak, M.; Drees, A.; Maaßen, S.; Paar, C. Highway to HAL: Open-sourcing the first extendable gate-level netlist reverse engineering framework. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM International Conference on Computing Frontiers; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 392–397. [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumaran, S.; Venkatesan, A.N.; Pula, K.; Narayanan, R.V.; Vemuri, R.; Emmert, J. Reverse Engineering of RTL Controllers from Look-Up Table Netlists. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), Foz do Iguacu, Brazil, 20–23 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, D.G.; Shokry, B.; Lenders, V.; Hu, W.; Stojilović, M. X-Attack 2.0: The Risk of Power Wasters and Satisfiability Don’t-Care Hardware Trojans to Shared Cloud FPGAs. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 8983–9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Chakraborty, R.S. Novel Hardware Trojan Attack on Activation Parameters of FPGA-Based DNN Accelerators. IEEE Embed. Syst. Lett. 2022, 14, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, Y.; Takemoto, S.; Ikezaki, Y.; Yoshikawa, M. LUT oriented Hardware Trojan for FPGA based AI Module. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Applied System Innovation (ICASI), Taitung, Taiwan, 5–8 November 2020; pp. 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikhila, S.; Yamuna, B.; Balasubramanian, K.; Mishra, D. FPGA Based Implementation of a Floating Point Multiplier and its Hardware Trojan Models. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 16th India Council International Conference (INDICON), Rajkot, India, 13–15 December 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, A.; Pasha, M.A.; Masud, S.; Qadri, M.Y.; Basit, A. FPGA Based Intelligent Hardware Trojan Design and its SoC Implementation. In Proceedings of the 2023 30th IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS), Istanbul, Turkiye, 4–7 December 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Jang, J.; Seo, Y.; Jeong, S.; Chung, S.; Kwon, T. ‘Towards bidirectional LUT-level detection of hardware Trojans. Comput. Secur. 2021, 104, 102223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Hu, W. Hardware Trojan Detection at LUT: Where Structural Features Meet Behavioral Characteristics. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Hardware Oriented Security and Trust (HOST), McLean, VA, USA, 27–30 June 2022; pp. 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazira, M.; Baleghi, Y.; Mahmoodpour, M.-A.; Jafari, H. Neural Networks & Logistic Regression for FPGA Hardware Trojan Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th Iranian International Conference on Microelectronics (IICM), Tehran, Iran, Islamic Republic of, 25–26 October 2023; pp. 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Su, H.; Zhang, X.; Tai, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, W. Automated Hardware Trojan Detection at LUT Using Explainable Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer Aided Design (ICCAD), San Francisco, CA, USA, 28 October–2 November 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, S. A Security-Driven FPGA Application Development Workflow Based on GCN Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Symposium of Electronics Design Automation (ISEDA), Xi’an, China, 10–13 May 2024; pp. 796–803. [Google Scholar]

- Chithra, C.; Kokila, J.; Ramasubramanian, N. Detection of Hardware Trojans using Machine Learning in SoC FPGAs. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Computing and Communication Technologies (CONECCT), Bangalore, India, 2–4 July 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaiari, U.; Gebali, F. Hardware Trojan Detection Using Reconfigurable Assertion Checkers. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 2019, 27, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Basel, H. Hardware Trojan Detection and High-Precision Localization in NoC-Based MPSoC Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 28th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASPDAC′23); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Q. EA-based Mitigation of Hardware Trojan Attacks in NoC of Coarse-Grained Reconfigurable Arrays. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Networking and Network Applications (NaNA), Urumqi, China, 3–5 December 2022; pp. 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, Z. Toward FPGA Security in IoT: A New Detection Technique for Hardware Trojans. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 7061–7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Panoff, M.K.; Wang, S.; Forte, D. HT-EMIS: A Deep Learning Tool for Hardware Trojan Detection and Identification through Runtime EM Side-Channels. In Proceedings of the Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI 2023 (GLSVLSI′23); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ma, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Golden Chip-Free Trojan Detection Leveraging Trojan Trigger’s Side-Channel Fingerprinting. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2020, 20, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Feng, S. Detecting Hardware Trojans by Monitoring Powersupply Noise Based on Ring Oscillator Network in FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Advanced Electronic Materials, Computers and Software Engineering (AEMCSE), Shenzhen, China, 24–26 April 2020; pp. 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giechaskiel, I.; Tian, S.; Szefer, J. Cross-VM Information Leaks in FPGA-Accelerated Cloud Environments. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Hardware Oriented Security and Trust (HOST), Tysons Corner, VA, USA, 12–15 December 2021; pp. 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilias, G.; Tian, S.; Jakub, S. Cross-VM Covert- and Side-Channel Attacks in Cloud FPGAs. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2022, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Suh, G.E. Remote Power Side-Channel Attacks on FPGAs. IEEE Des. Test 2025, 42, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yasaei, R.; Chen, H.; Li, Z.; Al Faruque, M.A. Stealing Neural Network Structure through Remote FPGA Side-channel Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA′21); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moini, S.; Deric, A.; Li, X.; Provelengios, G.; Burleson, W.; Tessier, R.; Holcomb, D. Voltage Sensor Implementations for Remote Power Attacks on FPGAs. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2022, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yang, B.; Xu, G.; Shao, B.; Zhao, X.; Ren, K. Persistent Fault Injection in FPGA via BRAM Modification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Dependable and Secure Computing (DSC), Hangzhou, China, 18–20 November 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moini, S.; Tian, S.; Holcomb, D.; Szefer, J.; Tessier, R. Power Side-Channel Attacks on BNN Accelerators in Remote FPGAs. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Circuits Syst. 2021, 11, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Moini, S.; Holcomb, D.; Tessier, R.; Szefer, J. A Practical Remote Power Attack on Machine Learning Accelerators in Cloud FPGAs. In Proceedings of the 2023 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), Antwerp, Belgium, 17–19 April 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glamocanin, O.; Coulon, L.; Regazzoni, F.; Stojilovic, M. Are cloud FPGA really vulnerable to power analysis attacks? In Proceedings of the 2020 Design, Automation Test in Europe Conference Exhibition (DATE), Grenoble, France, 9 March 2020; pp. 1007–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Huegle, L.; Gotthard, M.; Meyers, V.; Krautter, J.; Gnad, D.R.E.; Tahoori, M.B. Power2Picture: Using Generative CNNs for Input Recovery of Neural Network Accelerators through Power Side-Channels on FPGAs. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 31st Annual International Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing Machines (FCCM), Marina Del Rey, CA, USA, 8–11 May 2023; pp. 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yasaei, R.; Chen, H.; Li, Z.; Faruque, M.A.A. Stealing Neural Network Structure Through Remote FPGA Side-Channel Analysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2021, 16, 4377–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, V.; Gnad, D.; Tahoori, M. Reverse Engineering Neural Network Folding with Remote FPGA Power Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 30th Annual International Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing Machines (FCCM), New York, NY, USA, 15–18 May 2022; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Mazumdar, B.; Yasin, M.; Sinanoglu, O. Logic Locking With Provable Security Against Power Analysis Attacks. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2020, 39, 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifoori, Z.; Mirzargar, S.S.; Stojilović, M. Closing Leaks: Routing Against Crosstalk Side-Channel Attacks. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA′20); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himuro, M.; Iokibe, K.; Toyota, Y. FPGA Switching Current Modeling Based on Register Transfer Level Logic Simulation for Power Side-channel Attack Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC Europe, Gothenburg, Sweden, 5–8 September 2022; pp. 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Selvakumaran, D.; Zhu, D.; Chang, N.; Chow, C.; Nagata, M.; Monta, K. Fast and Comprehensive Simulation Methodology for Layout-Based Power-Noise Side-Channel Leakage Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Smart Electronic Systems (iSES) (Formerly iNiS), Chennai, India, 14–16 December 2020; pp. 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kian, A.; Hosseintalaee, H.; Jahanian, A. Protecting the FPGA IPs against Higher-order Side Channel Attacks using Dynamic Partial Reconfiguration. In Proceedings of the 2020 20th International Symposium on Computer Architecture and Digital Systems (CADS), Rasht, Iran, 19–20 August 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtex-4 FPGA Configuration User Guide. Available online: https://docs.xilinx.com/v/u/en-US/ug071 (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Virtex-5 FPGA Configuration User Guide. Available online: https://docs.xilinx.com/v/u/en-US/ug191 (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Bootgen User Guide (UG1283). Available online: https://docs.xilinx.com/r/2022.2-English/ug1283-bootgen-user-guide (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- UltraScale Architecture Configuration User Guide (UG507). Available online: https://docs.amd.com/v/u/en-US/ug570-ultrascale-configuration (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- MachXO3D Family Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.latticesemi.com/view_document?document_id=52590 (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- AC432: Using SHA-256 System Services in SmartFusion2 and IGLOO2 Devices. Available online: https://www.microchip.com/en-us/application-notes/ac432 (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- SmartFusion 2 and IGLOO 2 FPGA Security and Best Practices User Guide (Earlier UG0443). Available online: https://ww1.microchip.com/downloads/aemDocuments/documents/FPGA/ProductDocuments/UserGuides/SmartFusion2_IGLOO2_FPGA_Security_Best_Practices_UG0443_V10.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Wang, S.; Fan, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Ju, L.; Zhou, Z. FPGA-TrustZone: Security Extension of TrustZone to FPGA for SoC-FPGA Heterogeneous Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2025 62nd ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 22–25 June 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Luo, Y.; Xu, X.; Wei, S. SGX-FPGA: Trusted Execution Environment for CPU-FPGA Heterogeneous Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2021 58th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 5–9 December 2021; pp. 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MachXO5-NX Family Root-of-Trust Devices (FPGA-DS-02120-0.81). Available online: https://www.latticesemi.com/view_document?document_id=54310 (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Benhani, E.M.; Marchand, C.; Aubert, A.; Bossuet, L. On the security evaluation of the ARM TrustZone extension in a heterogeneous SoC. In Proceedings of the 2017 30th IEEE International System-on-Chip Conference (SOCC), Munich, Germany, 5–8 September 2017; pp. 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, M.A.; Bhatti, M.K.; Gogniat, G. Architectures for Security: A comparative analysis of hardware security features in Intel SGX and ARM TrustZone. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Communication, Computing and Digital systems (C-CODE), Islamabad, Pakistan, 6–7 March 2019; pp. 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, C.; Patil, S.B.; Dhanuskodi, S.N.; Provelengios, G.; Pillement, S.; Holcomb, D.; Tessier, R. FPGA Side Channel Attacks without Physical Access. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 26th Annual International Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing Machines (FCCM), Boulder, CO, USA, 29 April–1 May 2018; pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krautter, J.; Gnad, D.R.E.; Schellenberg, F.; Moradi, A.; Tahoori, M.B. Active Fences against Voltage-based Side Channels in Multi-Tenant FPGAs. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD), Westminster, CO, USA, 4–7 November 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorobogatov, S.; Woods, C. Breakthrough silicon scanning discovers backdoor in military chip. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems (CHES′12); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyrbiak, M.; Wallat, S.; Swierczynski, P.; Hoffmann, M.; Hoppach, S.; Wilhelm, M.; Weidlich, T.; Tessier, R.; Paar, C. HAL—The Missing Piece of the Puzzle for Hardware Reverse Engineering, Trojan Detection and Insertion. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2019, 16, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, W. Novel Design of Hardware Trojan: A Generic Approach for Defeating Testability Based Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 19th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Guangzhou, China, 29 December 2020–1 January 2021; pp. 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, H. ASAX: Automatic security assertion extraction for detecting Hardware Trojans. In Proceedings of the 2018 23rd Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASP-DAC), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 22–25 January 2018; pp. 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, J.; Hu, W. Identifying Specious LUTs for Satisfiability Don’t Care Trojan Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 34th International System-on-Chip Conference (SOCC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 14–17 September 2021; pp. 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yuan, F.; Wei, L.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Q. VeriTrust: Verification for Hardware Trust. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2015, 34, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Hu, W.; Wu, L.; Zhu, D.; Mu, D. LUT Level Information Flow Tracking for FPGA Design Security Verification. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2024—2024 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 12 December 2024; pp. 3093–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, K.; Wang, S.; Zhou, J. Integration of a Trojan Detection Tool with BFDS: Enhancing Field-Programmable Gate Array Security. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Automation and Algorithms, Shanghai, China, 29 September 2024; pp. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bayrak, A.G.; Velickovic, N.; Regazzoni, F.; Novo, D.; Brisk, P.; Ienne, P. An EDA-friendly protection scheme against side-channel attacks. In Proceedings of the 2013 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), Grenoble, France, 18–22 March 2013; pp. 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhan, I.; Batina, L.; Yarom, Y.; Schaumont, P. SoK: Design Tools for Side-Channel-Aware Implementations. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security (ASIA CCS′22); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, J.; Chowdhury, A.B.; Sinanoglu, O.; Garg, S.; Karri, R.; Knechtel, J. ASCENT: Amplifying Power Side-Channel Resilience via Learning & Monte-Carlo Tree Search. In Proceedings of the 43rd IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 27–31 October 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahiyan, A.; Park, J.; He, M.; Iskander, Y.; Farahmandi, F.; Forte, D.; Tehranipoor, M. SCRIPT: A CAD Framework for Power Side-channel Vulnerability Assessment Using Information Flow Tracking and Pattern Generation. ACM Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Syst. 2020, 25, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, Y.; He, J.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, Y. PathFinder: Side channel protection through automatic leaky paths identification and obfuscation. In Proceedings of the 59th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC′22); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Shi, J.; Zhang, S.; Pan, W.; Hao, Y. Hardware Trojan Detection for Gate-level Netlists Based on Graph Neural Network. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2023, 45, 3253–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, T.; Togawa, N. Hardware-trojan classification based on the structure of trigger circuits utilizing random forests. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 27th International Symposium on On-Line Testing and Robust System Design (IOLTS), Torino, Italy, 28–30 June 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, K.; Hidano, S.; Nozawa, K.; Kiyomoto, S.; Togawa, N. R-htdetector: Robust hardware-trojan detection based on adversarial training. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2022, 72, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Tai, Y.; Cai, H.; Wang, S.; Xiao, K.; Zhang, X.; Dong, H.; Du, Z. Efficient and high-security FPGA configuration bitstream cryptographic algorithm and implementation. Integr. Circuits Embed. Syst. 2025, 25, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Research Area | Year | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Duncan [8] | D1: FPGA security studies | 2019 | Threats and vulnerabilities associated with FPGA bitstreams. |

| Jiliang Zhang [9] | 2019 | Threats and defense mechanisms in FPGA-based systems, focusing on supply chain and design flow. | |

| Z. Huang [10] | D2: Studies on applications of AI in FPGA security | 2020 | ML-based approaches against HT attacks from four perspectives: HT detection, DFS, bus security, and secure architecture. |

| X. Xu [11] | D3: Security studies on FPGA application | 2020 | The dual impact of machine learning on FPGA security, both as a tool for attack and defense. |

| Furkan Turan [12] | 2020 | Trust models and security challenges in FPGA-accelerated cloud computing platforms and reviews existing solutions. | |

| Kaspar Matas [13] | 2020 | Hardware security challenges for FPGAs in datacenters. | |

| S. Sunkavilli [14] | D1: FPGA security studies | 2021 | Security threats in new FPGA utilization model in the era of machine learning and cloud computing. |

| G. Dessouky [15] | D3: Security studies on FPGA application | 2021 | Security challenges and opportunities in secure FPGA multi-tenancy in the cloud. |

| S. Duan [16] | 2021 | Security vulnerabilities and defense mechanisms in FPGA-based hardware acceleration systems. | |

| Z. Pan [17] | D2: Studies on applications of AI in FPGA security | 2022 | Utilization of machine learning techniques for hardware vulnerability analysis. |

| Lilas Alrahis [18] | 2022 | Application of GNNs in hardware security and attacks on logic locking. | |

| A. Hasnain [19] | D1: FPGA security studies | 2022 | Power profiling-based side-channel attacks on FPGAs and associated countermeasures. |

| Hoda Naghibijouybari [20] | D3: Security studies on FPGA application | 2022 | Microarchitectural attacks in heterogeneous computing systems. |

| Dina G. Mahmoud [21] | 2022 | Electrical-level security threats on CPUs, FPGAs, and GPUs. | |

| Troya Çağıl Köylü [22] | D2: Studies on applications of AI in FPGA security | 2023 | Applications of machine learning in hardware security. |

| David Koblah [23] | 2023 | Application of artificial intelligence and machine learning in electronic design automation. | |

| Alexandre Proulx [24] | D1: FPGA security studies | 2023 | Security aspects of SoC FPGA devices incorporating a hard processing system. |

| P. D. Rosero-Montalvo [25] | D3: Security studies on FPGA application | 2023 | Security concerns for utilizing FPGAs in cloud computing. |

| Ferhat Erata [26] | 2023 | Methods for security verification across hardware and software layers in computer systems. | |

| Ruyan Lin [27] | D1: FPGA security studies | 2024 | Methods for detecting vulnerabilities and security patches while identifying research gaps and future directions. |

| Zain Ul Abideen [28] | D3: Security studies on FPGA application | 2024 | Reconfigurable-based obfuscation techniques that combat security threats in hardware design. |

| Muhammed Kawser Ahmed [29] | 2025 | Examination of the security concerns associated with multi-tenant cloud FPGAs, providing a comprehensive overview of the related security, privacy and trust issues, and discussing forthcoming challenges in this evolving field of study. |

| Threat Domain | Security Measure Summary | FPGA Manufacturers | Security Measures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration Security | Cryptographic algorithms and authentication mechanisms | Manufacturers | Device | Security Method |

| Xilinx | 28 nm [165] | AES CBC + HMAC | ||

| 14 nm [166] | AES GCM + RSA | |||

| Intel [75] | 40 nm | AES CTR | ||

| 28 nm | AES CBC | |||

| 20 nm | AES CTR + HMAC | |||

| Lattice [167] | e | |||

| Microchip [168,169] | AES + SHA + HMAC + ECDSA | |||

| Interface Security | Access rights of readback ports | Intel [75] | 20 nm | The control function of access rights to the JTAG port |

| Microchip [74] | Verification mechanism for disabling readback debugging | |||

| Physical Security | Various measures | Xilinx | 14 nm [166] | Pre-authentication, rolling keys, and internal self-authentication |

| PSoC [170] | ARM TrustZone | |||

| Intel | PSoC [171] | Software Guard Extensions (SGX) | ||

| Lattice [172] | Hardware root of trust (HRoT) functions | |||

| Microchip [168,169] | Key-tree derivation algorithm | |||

| Logic Security | EDA tool | Microchip [74] | DesignShield development tool | |

| Manufacturers | Device | Security Measures | Defense Effect | Bypass Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xilinx | 28 nm [165] | AES CBC + HMAC | Mainstream anti-cloning and anti-tampering capabilities | StarBleed vulnerability [41] Side-channel analysis [72] |

| 14 nm [166] | AES GCM + RSA | Better anti-cloning and anti-tampering capabilities | GHASH-based checksum and authentication downgrade attacks [42] | |

| Pre-authentication, rolling keys, and internal self-authentication | DPA resistance | Side-channel analysis [73] | ||

| PSoC [170] | ARM TrustZone | Heterogeneous SoC protection | Third-party IP attacks [173] Software-based side-channel attacks [174] Hardware Trojans [60] | |

| Intel [75] | 40 nm | AES CTR | Mainstream anti-cloning and anti-tampering capabilities | Side-channel analysis [175] |

| 28 nm | AES CBC | |||

| 20 nm | AES CTR + HMAC | |||

| The control function of access rights to the JTAG port | Debug interface protection | \ | ||

| PSoC [171] | Software Guard Extensions (SGX) | Heterogeneous SoC protection | Fault injection attack [115] Software-based side-channel attacks [174] | |

| Lattice [167] | AES + HMAC + ECDSA | Anti-cloning and anti-tampering capabilities | Side-channel analysis [176] | |

| Hardware root of trust (HRoT) functions | DPA resistance | |||

| Microchip | AES + SHA + HMAC + ECDSA [168,169] | Anti-tamper | \ | |

| Verification mechanism for disabling readback debugging [172] | Reverse engineering protection | Backdoor for accessing FPGA configuration [177] | ||

| Key-tree derivation algorithm [168,169] | Data security through system service | \ | ||

| DesignShield development tool [172] | Anti-HT | |||

| Method | True Positive Rate (TPR) | True Negative Rate (TNR) | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| GCN + GraphSMOTE [184] | 96.1% | 94.0% | 88.1% |

| GraphSAGE [190] | 92.9% | 99.8% | 86.2% |

| Random Forest [191] | 63.6% | 100.0% | 77.8% |

| R-HTDetector [192] | 96.8% | 94.5% | 59.9% |

| LUT-Level Detection Methods [134] | 98.4% | 100.0% | 99.5% |

| Neural Networks and Logistic Regression [135] | 86% | - | - |

| XGNNs [136] | 98.8% | 98.7% | 99.2% |

| Target Implementation | Traces Used | Max Observed Correlation | Key Recovered? |

|---|---|---|---|

| AES-256 (CBC, conventional) | 5000 | 0.42 | Yes |

| AES256_CTR + GMAC_GF32 (pipelined, as in [193]) | 100,000 | 0.08 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Xiao, K.; Wang, S. Research on the Security of SRAM-Based FPGAs in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2025, 15, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jlpea15040066

Zhou J, Zhao X, Zhang S, Chen L, Xiao K, Wang S. Research on the Security of SRAM-Based FPGAs in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. Journal of Low Power Electronics and Applications. 2025; 15(4):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jlpea15040066

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Jing, Xiangyu Zhao, Shengbing Zhang, Lei Chen, Ke Xiao, and Shuo Wang. 2025. "Research on the Security of SRAM-Based FPGAs in the Era of Artificial Intelligence" Journal of Low Power Electronics and Applications 15, no. 4: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jlpea15040066

APA StyleZhou, J., Zhao, X., Zhang, S., Chen, L., Xiao, K., & Wang, S. (2025). Research on the Security of SRAM-Based FPGAs in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. Journal of Low Power Electronics and Applications, 15(4), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jlpea15040066