Abstract

This work presents an ultra-low-power on-chip energy management (EM) circuit, which is the most critical and power-intensive block in power management integrated circuits (PMICs) used for energy harvesting (EH) applications. Ultra-low power consumption was the primary design priority to ensure suitability for systems operating under strict energy limitations. The design relies on a compact latch-based core and avoids the need for extra circuits such as voltage references, comparators, or logic blocks, which helps reduce both area and power. To implement the required high resistance, a series of diode-connected zero-threshold NMOS transistors is used. This approach enables very high resistance in a compact area without additional power consumption or biasing issues at low voltages. A PMOS transistor is also integrated at the EM output to directly control different types of loads. The circuit was designed and fabricated using a 65 nm CMOS standard process. Experimental measurements from the fabricated chips show a quiescent current of 170 nA at 3 V and a voltage hysteresis of over 0.9 V. In addition, temperature and process variation were simulated to verify robust operation. These results confirm that the circuit operates reliably under ultra-low-power conditions and is well-suited for EH systems.

1. Introduction

In modern society, portable, wearable, and implementable electronic devices have become essential. The rapid growth of the Internet of Things (IoT) and wireless sensor networks (WSNs) continues to drive efforts to improve quality of life across various domains. However, battery-powered devices suffer from limited lifetime and maintenance challenges, along with environmental concerns and the high cost of replacement. These challenges become even more critical in devices placed in hard-to-access environments, such as inside the human or animal body or in remote locations [1,2].

Energy harvesting (EH) offers a promising alternative to batteries by converting ambient energy from mechanical vibration, light, heat, or radio frequency into electrical power. Common EH technologies include piezoelectric, thermoelectric, and photovoltaic transducers [3,4,5].

Although EH has strong potential, it faces a fundamental limitation. The energy available from ambient sources is often too low and unreliable compared to traditional batteries, especially for many modern electronic applications. As a result, devices powered by EH may experience frequent power interruptions or unstable operation due to inconsistent input energy [6].

Integrating EH techniques with battery-based systems can extend operational time and improve reliability, addressing some of the limitations of using batteries or energy harvesters alone. However, in many cases, this approach is not practical or effective, as the use of batteries still poses significant challenges, particularly in long-term and remote applications [7,8,9].

These devices demand a fundamentally different power management approach compared to systems with fixed supply voltages. Power management integrated circuits (PMICs) in EH systems are inherently more complex and typically consist of several components, including a voltage rectifier, energy storage element, energy management (EM) block, low-dropout regulators (LDOs), and others. Among these, the most complex and power-consuming block in a PMIC is the EM. This block is responsible for detecting the stored energy level and enabling or disabling the load based on the available energy and the energy required by the load. Therefore, implementing this block becomes more complex and requires additional considerations, especially when dealing with limitations in the amount of harvested energy. The EM block is known by various names, including start-up circuit, energy-aware circuit, switching circuit, wake-up circuit, power-on reset circuit, trigger circuit, control circuit, voltage supervisor circuit, voltage monitor circuit, and under-voltage lockout circuit [9,10].

Generally, in electronic circuits, when the supply voltage drops below a certain threshold, even for a short transient period, the probability of system failure or malfunction increases. Preventing such conditions differs between fixed-supply and EH circuits. Fixed-supply and battery-powered systems typically include a voltage monitor connected to the supply rail. When the supply voltage falls below a predefined threshold, which defines the minimum acceptable operating voltage, the voltage monitor output becomes active (either high or low, depending on the design) to disconnect the load. This strategy protects the battery and prevents the circuitry from malfunctioning. When the supply voltage rises above the reference threshold, the monitor allows the load to reconnect, and the load voltage follows the supply voltage [11,12,13]. Beyond these limitations, EM blocks in EH applications face additional challenges due to the unpredictable and often limited nature of the harvested energy, making voltage monitoring more complex and requiring well-considered and efficient implementation techniques.

Recent research on EM architectures has focused on improving the efficiency and reliability of EH systems through more integrated and system-oriented designs. Several system-level approaches have also been introduced [10,14], integrating multiple control and regulation blocks to improve power stability in complex EH platforms. However, these implementations often rely on auxiliary subcircuits such as voltage references, comparators, or biasing networks, which increase quiescent current and occupy larger area [13,15]. In contrast, latch-based EM circuits [2,8,9] provide simpler structures with inherently low power consumption. Despite this advantage, most of the reported designs still depend on off-chip resistors or external bias components to obtain high resistance and hysteresis control, which constrains full on-chip integration and scalability.

In this work, we address these limitations by implementing a fully integrated latch-based EM circuit in a standard 65 nm CMOS process. The proposed design employs a compact voltage divider composed of diode-connected zero-threshold-voltage NMOS devices to emulate very high resistances without biasing overhead, achieving ultra-low quiescent current and a large hysteresis window within a small silicon area.

Beyond circuit-level improvements, the proposed low-power EM circuit is well suited for future multi-chip, power delivery networks (PDNs), and 3D integrated systems, where distributed EM, on-die power monitoring, and hysteresis control are essential for maintaining power integrity under dynamic harvesting or load conditions [16]. It is also highly suitable for EH sources such as triboelectric harvesters, which typically produce rectified output voltages around 3 V, making an EM with very low power consumption particularly valuable.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the fundamental concepts of EMs for EH applications. Section 3 describes the design procedure and analysis of the proposed circuit. Section 4 presents the simulation and measurement results, along with a comparison to existing commercial and research works. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key conclusions.

2. EM Fundumentals

In an EH system, omitting the EM or using a voltage monitor with a fixed single detection threshold can lead to start-up failures, especially when the available energy is lower than what the load requires. It is also important to note that the presence of a storage element, typically a capacitor, is essential regardless of whether the input signal of the EH system is DC or AC. Once the harvested energy charges the storage capacitor (C_S) to the minimum required voltage of the load (VTL), the load turns on. However, the initial current demand causes a sharp drop in the capacitor voltage (VC_S), lowering it below VTL and turning the load off again. This creates a repeated cycle of charging and failed start-up attempts, known as lock-up or start-up failure, which prevents stable operation of the system [9].

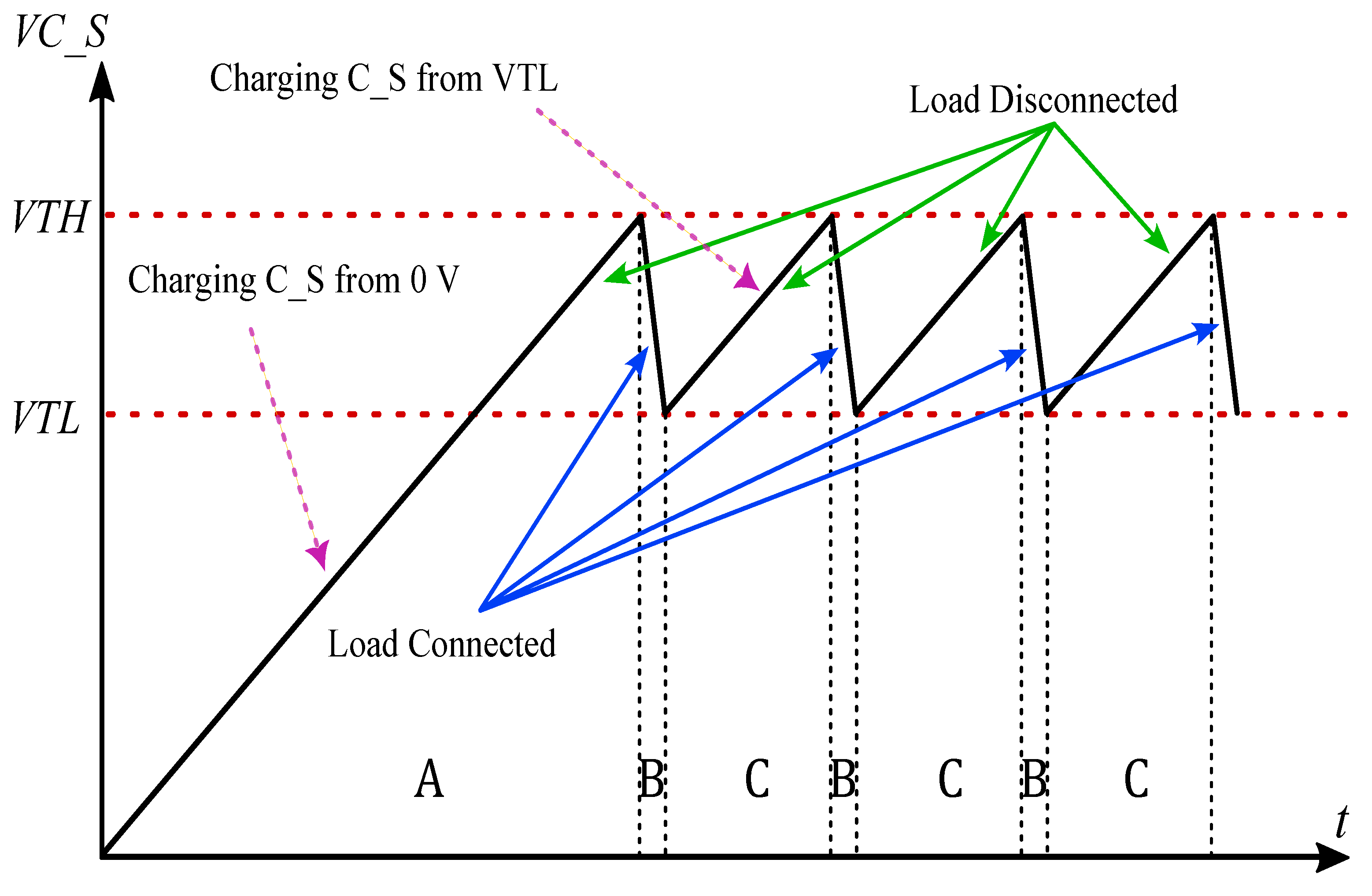

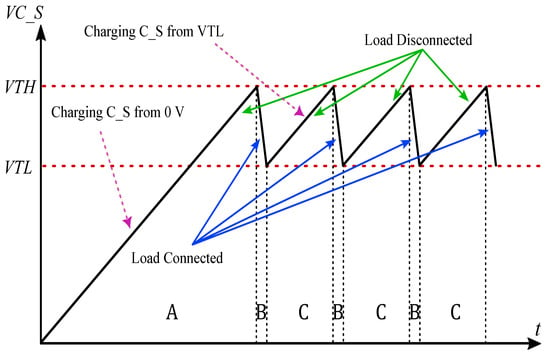

To ensure reliable operation, the EM should have two voltage thresholds. The higher level (VTH) activates the load, while the lower level (VTL) disconnects it. VTH must be high enough to support stable functionality but still remain within the voltage tolerance of the load. This dual-threshold method ensures that the load is only connected when sufficient energy is available. The functional conceptual waveform of an EM in EH systems is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Expected waveforms of a typical EM circuit in an EH system.

Assuming the storage capacitor is initially fully discharged, the voltage across it (VC_S) gradually rises from zero to higher levels, as shown in Region A of Figure 1. During this phase, the output of the EM remains disabled, and the load is disconnected.

When VC_S reaches VTH, the output of the EM is enabled, connecting the load to the capacitor. At this point, the capacitor has sufficient energy stored to ensure stable operation, even during sudden discharges by the load. The load continues to function until VC_S drops to VTL, marking region B. At VTL, the EM disables the output and disconnects the load once again. After disconnection, the capacitor begins charging again to reach VTH. This second charging cycle, shown in region C, is faster because it starts from VTL rather than zero, unlike in region A.

These operating cycles repeat intermittently, preventing start-up failure and ensuring stable energy delivery to the load. It is important to note that the EM is always connected to the storage capacitor, even when the load is disconnected. Therefore, the EM should have an ultra-low quiescent current to avoid excessive energy loss.

The difference between VTH and VTL and the capacitor value, define the maximum available energy in each charging and discharging cycle based on Equation (1).

The difference between VTH and VTL is called hysteresis. A larger hysteresis allows more energy to be stored, which helps prevent lock-up. However, increasing hysteresis typically results in higher power consumption in the EM circuit. Therefore, many on-chip EMs proposed in research, as well as commercial monitors designed for ultra-low current consumption, keep hysteresis small or restrict it to low voltage ranges [6,13]. Increasing the capacitor value can also increase the stored energy, but this approach is generally unsuitable for applications with strict size constraints, such as implantable systems.

According to state-of-the-art designs, the EM block can be implemented using three main topologies:

- The first structure relies on voltage comparators, which compare the voltage level to predefined thresholds.

- The second structure employs a comparator in the form of current comparison, evaluating the flow of current within the circuit.

- The last structure is based on a latch circuit, toggling between the supply voltage and ground to control energy flow.

For the first and second structures, comparators are essential. Additionally, complex circuits such as bandgap references, hysteresis control mechanisms, clock generators, timing controls, logic gates, multiplexers, and switches are required. The latch-based network has a simpler structure compared to the others [2,3,9,13,15]. Due to the demands for ultra-low quiescent current and on-chip integration, this work adopts the third approach.

Latch-Based EM

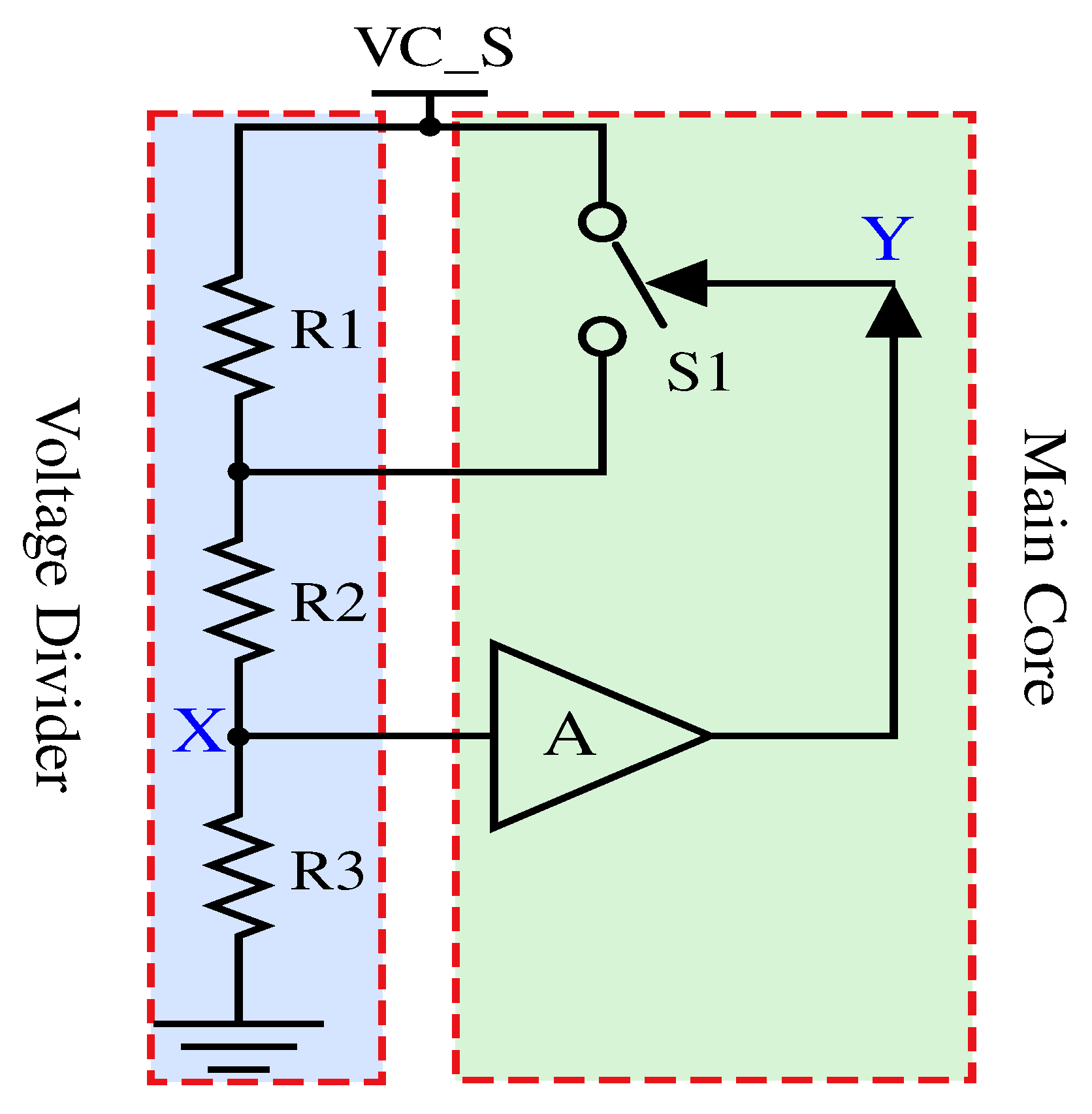

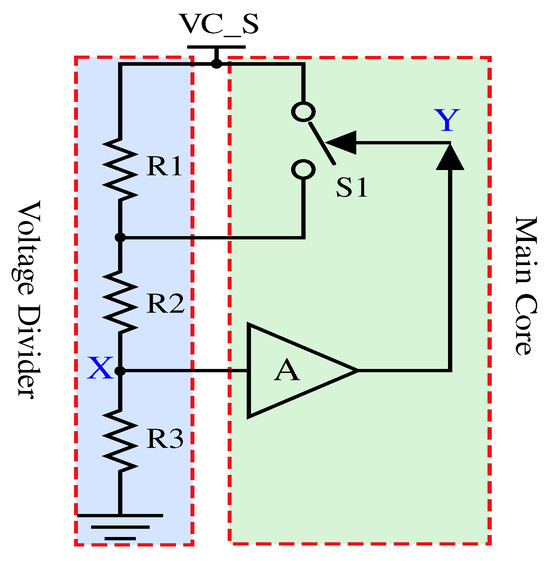

The conceptual topology of a latch-based EM circuit is depicted in Figure 2. VC_S acts as the supply rail or the input voltage of the EM, while resistors R1, R2, and R3 form a voltage divider that sets the thresholds VTH and VTL. The switch (S1) and the semi-gain function (A) together generate hysteresis and toggle the output state. As shown in the related waveform for the storage capacitor in Figure 1, the latch-based circuit alternates between enabling and disabling the load.

Figure 2.

Conceptual architecture of a typical latch-based EM.

- Enabling: When VC_S becomes sufficiently high, the voltage at node X (VX) activates block A, and node Y is enabled. This action closes switch S1, causing resistor R1 to be shorted, which generates hysteresis. After connecting the load, this increase at VX preserves the existing state (region B). The value of VC_S just before the transition to the on state, while switch S1 is still open (region A), is defined as VTH. We have:

- Disabling: When falls below the level required by block A, block A turns off, node Y is disabled, and switch S1 opens (Region C). Similarly, the value of just before the transition to the off state, while switch S1 is still closed (region B), is defined as . We have:

By appropriately manipulating this concept, it becomes possible to implement dual-threshold voltage levels for connecting or disconnecting the load, in a simple manner and without the need for additional circuitry.

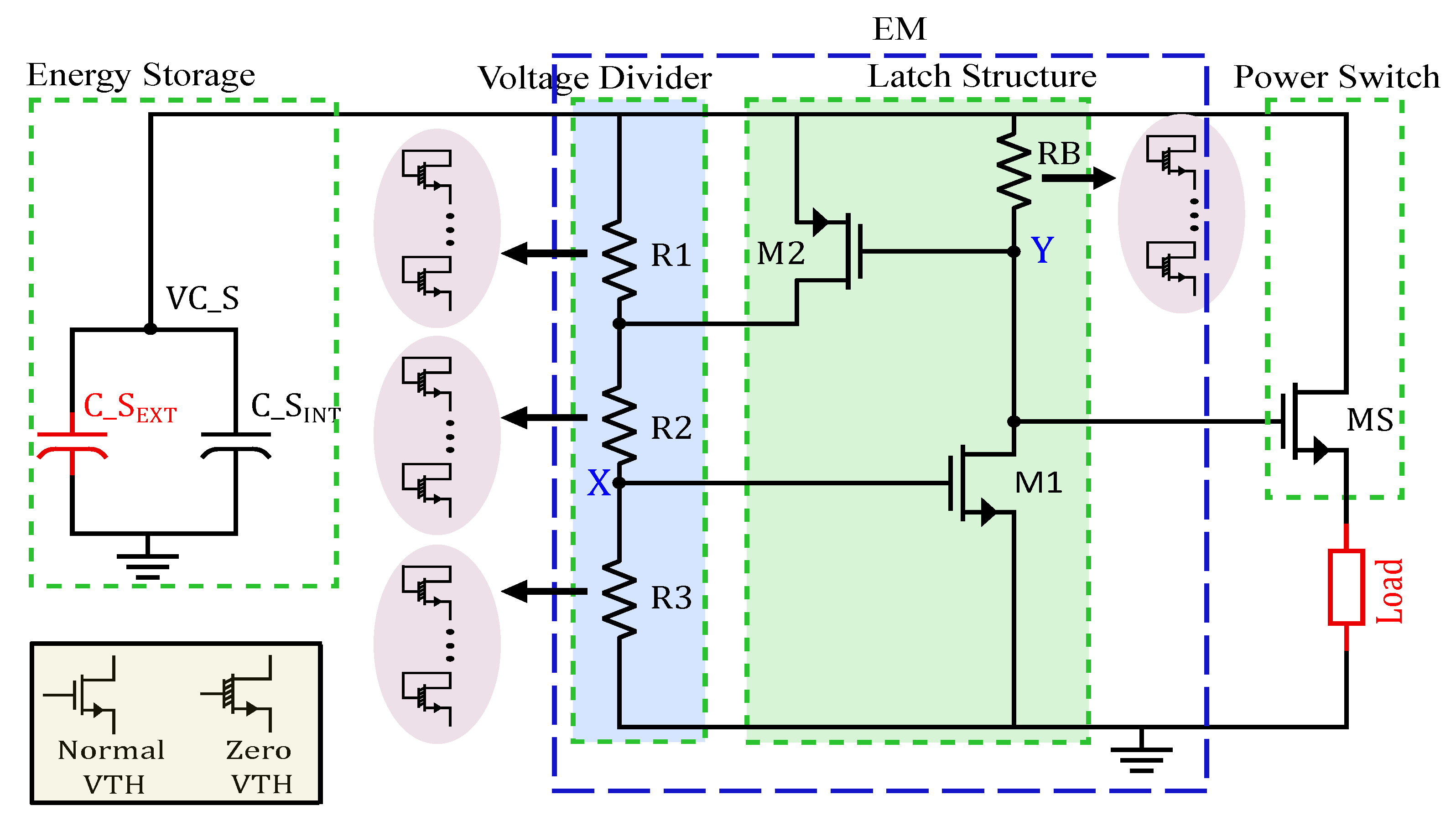

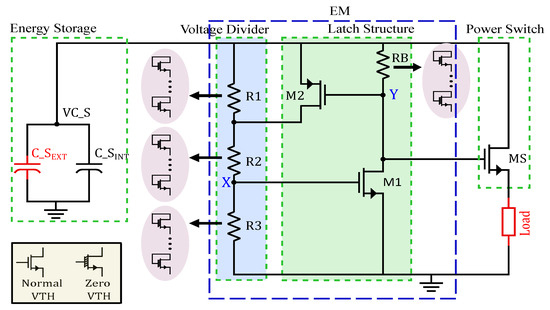

3. Proposed Circuit

The schematic of the proposed EM is highlighted in Figure 3, which is based on Figure 2. The voltage divider is the same as the one shown in Figure 2, where M1 and RB provide the semi-gain function (A), and M2 operates as the switch (S1). In addition, a PMOS transistor (MS) is employed as a power switch to transfer energy to the load. It is important to note that in the proposed EM, all circuit elements are integrated on-chip, except for the load and , which should be implemented off-chip, as highlighted in red in Figure 3. This configuration, which allows flexibility in choosing , enables adjustment of the discharging time based on load requirements and harvested energy. Additionally, unused chip area has been allocated for internal capacitors (), helping to reduce or even eliminate the need for external capacitors when energy demand is low and harvested energy is sufficient.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the proposed EM circuit.

To analyze the EM circuit, the behavior of is examined based on the waveform shown in Figure 1 and Equations (2) and (3).

- Region A: Initially, when is at 0 V, both transistors M1 and M2 are fully off. The output node of EM circuit, labeled as Y, is connected to the supply rail through resistor RB. The PMOS power switch MS, remains off in this region because the voltage at node Y is sufficiently close to . As increases, the voltage at the gate of M1, denoted as , can be expressed as:is the gate-source voltage of M1. When is above 0 V but below the threshold voltage of M1, transistor M1 operates in the sub-threshold region. In this state, M1 is not fully on and conducts only a very low sub-threshold current. The current through M1 can be calculated as:represents the threshold voltage of M1. is a process-dependent current constant, n is the ideality factor, k is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature of the transistor, and q is the electron charge. Equation (5) is valid only at low values, where the current through the voltage divider is low, leading to a low . As a result, M1 conducts only a minimal current, which is insufficient to activate the circuit for normal operation. For M2, we have:At the transition from Region A to Region B, M1 enters a transient state, shifting from nearly off to fully on. Assuming that both M1 and M2 are still off during this transition, we have:Once reaches , transistor M2 turns on, acting as a switch that shorts and causes hysteresis.

- Region B: In this region, all transistors M1, M2 and MS are on. This state continues, and node Y remains nearly tied to ground as long as stays above Vth1 to keep M1 fully on. During this period, M2 shorts , increasing despite the drop in . This keeps M1 on and introduces hysteresis. At the end of region B and the beginning of region C, M2 begins a transition from on to off. By assuming M2 is still on and continues to short , we have:

- Region C: Clearly, M1 stays off, and the voltage at node Y, which controls M2 and MS, is shorted to until reaches again.

3.1. Power Consumption Analysis

To analyze the power consumption of the EM, we examine the current flowing through three vertical branches: the voltage divider, M1 together with the bias resistor RB, and M2. Again, based on the expected waveform shown in Figure 1, the operation is divided into three regions, allowing estimation of current consumption in each state.

- Region A: During the charging phase of from 0 V to , both M1 and M2 remain completely or nearly off, consuming negligible current compared to the voltage divider. The maximum current in this state is given by:

- Region B: During the discharging phase of from to , the EM output is active. Most of the current is consumed by the load through MS, while a smaller portion is consumed by the EM. Since M1 and M2 are on in this region, the quiescent current is higher than in Region A. For M1, the current can be calculated by:where is the process transconductance parameter of the NMOS, W and L are transistor width and length, respectively, , and are the gate-to-source voltage, threshold voltage, and drain-to-source voltage of M1, respectively. where is the process transconductance parameter of the NMOS, W and L are transistor width and length, respectively, , and are the gate-to-source voltage, threshold voltage, and drain-to-source voltage of M1, respectively. To reduce the current through M1, should be minimized. This can be achieved by increasing the value of RB. For example, when is 3 V and the desired current for M1 is 50 nA, RB should be around 60 MΩ. In this design, to properly bias M2 and maintain ultra-low current in M1, even higher values, such as 100 MΩ, are required. The current through M2 is mainly set by and , since the drain–source resistance of M2 (Rds) is much smaller than , effectively shorting . Therefore, the current can be approximated as:Note that this value represents the maximum current for M2 assuming is fully shorted by M2. When is not completely shorted, the third term in the denominator of the first term in Equation (12) is higher, leading to a lower current. The total current consumption in this state can be estimated by:

- Region C: During the charging phase of from to , the EM output is disabled, and the maximum current consumption in this state is similar to that in Region A.

3.2. High Resistance Implementation

Implementing resistors in the tens of megaohms range using standard or high-resistivity polysilicon resistors in a typical CMOS process is generally inefficient because they occupy a large on-chip area. For instance, a 100 MΩ poly-silicon resistor can require around 2 mm2 to 2.5 mm2 of silicon area, depending on the technology used, which makes this approach unsuitable for compact or area-constrained designs.

This limitation explains why most ultra-low quiescent current monitors with large hysteresis in state-of-the-art research are implemented off-chip. Moreover, few commercial voltage monitors provide ultra-low quiescent current, and in many cases, the hysteresis remains small [2,9,11].

To implement high resistance values for , , , and RB on-chip, an effective approach is to connect multiple transistors in series, configured as diode-connected devices, as shown in Figure 3. However, achieving resistance in the tens of megaohms and current levels in the tens of nanoamperes requires a large number of transistors. Consequently, at low voltages, it becomes unachievable to properly bias these transistors or even keep them operating in the subthreshold region due to the cumulative threshold voltage drop. Increasing the channel length-to-width ratio to reduce the transistor count leads to the same problem.

To solve this, we used zero-threshold-voltage (native) NMOS transistors, which are commonly available in standard CMOS technologies. Zero-threshold-voltage NMOS transistors were selected for the stacked network to maintain conduction continuity at very low input voltages and to avoid cumulative threshold losses that occur with regular-Vth devices. Although regular-Vth transistors can provide higher individual resistance, their use in long stacks degraded startup reliability and reduced the accuracy of the latch thresholds. The zero-Vth implementation therefore allows the voltage divider to emulate very high resistances while maintaining predictable hysteresis and reliable startup behavior.

The number and size of these zero-threshold-voltage transistors to implement each resistor depend on the current constraints of the EM and the required resistance, as defined by Equations (8) and (9), to achieve the desired and levels. In our implementation, all zero-threshold-voltage NMOS transistors have the same size, and the values of the resistors were adjusted by varying the number of transistors connected in series. Thanks to this approach, it was possible to implement high resistance values on-chip in a small area without adding extra power consumption to the circuit.

3.3. Load Connection

In many cases, the output of the EM does not directly supply the load. Instead, it serves as a control signal to enable or disable the load, typically a microcontroller, a sensor, or an external switch that connects the load supply to the storage capacitor. In the proposed implementation, a PMOS transistor (MS) is used as the power switch to enable direct power delivery to the load without relying on external components. A PMOS device is chosen because the gate needs to be pulled low relative to the source to conduct, which matches the behavior of node Y, as it remains at a low voltage when sufficient energy is available in the storage capacitor. This approach is particularly advantageous, as it allows operation even at low supply voltages. A relatively large channel width is selected for this pass transistor to ensure it can handle higher current levels when necessary and to minimize on-resistance.

It should be noted that in some applications where the load requires a fixed supply voltage, LDOs are essential after the EM. But for many loads, not using a regulator is acceptable and helps reduce the additional power consumption involved. Many loads, particularly in IoT applications such as the MSP430 and CC1310 microcontrollers from Texas Instruments Inc., are well-known commercial examples that can operate without requiring a regulated supply voltage [17,18].

In our design, the threshold levels were selected to ensure reliable operation of typical low-voltage loads, such as the aforementioned microcontrollers. The high threshold () guarantees proper start-up of the system, while the low threshold () prevents premature shutdown under limited energy conditions. Moreover, as shown by Equation (1), the stored energy in the capacitor is sufficient to sustain the load operation even when the capacitor size is restricted, confirming that these threshold choices provide an optimal trade-off between stability and available energy.

4. Results

In this section, we present both simulation results from Cadence Spectre and measurement results of the proposed EM circuit, fabricated in a 65 nm CMOS standard process with a single polysilicon layer and nine metal layers. All transistors used in the design, including NMOS, PMOS, and zero-threshold NMOS, are high-voltage devices that safely operate under a 3.3 V supply. To characterize the circuit, a Keithley 2450 SourceMeter and a Keithley 2000 multimeter with an input impedance greater than 10 GΩ were used. Transient responses were recorded using an Agilent DSO1052B oscilloscope.

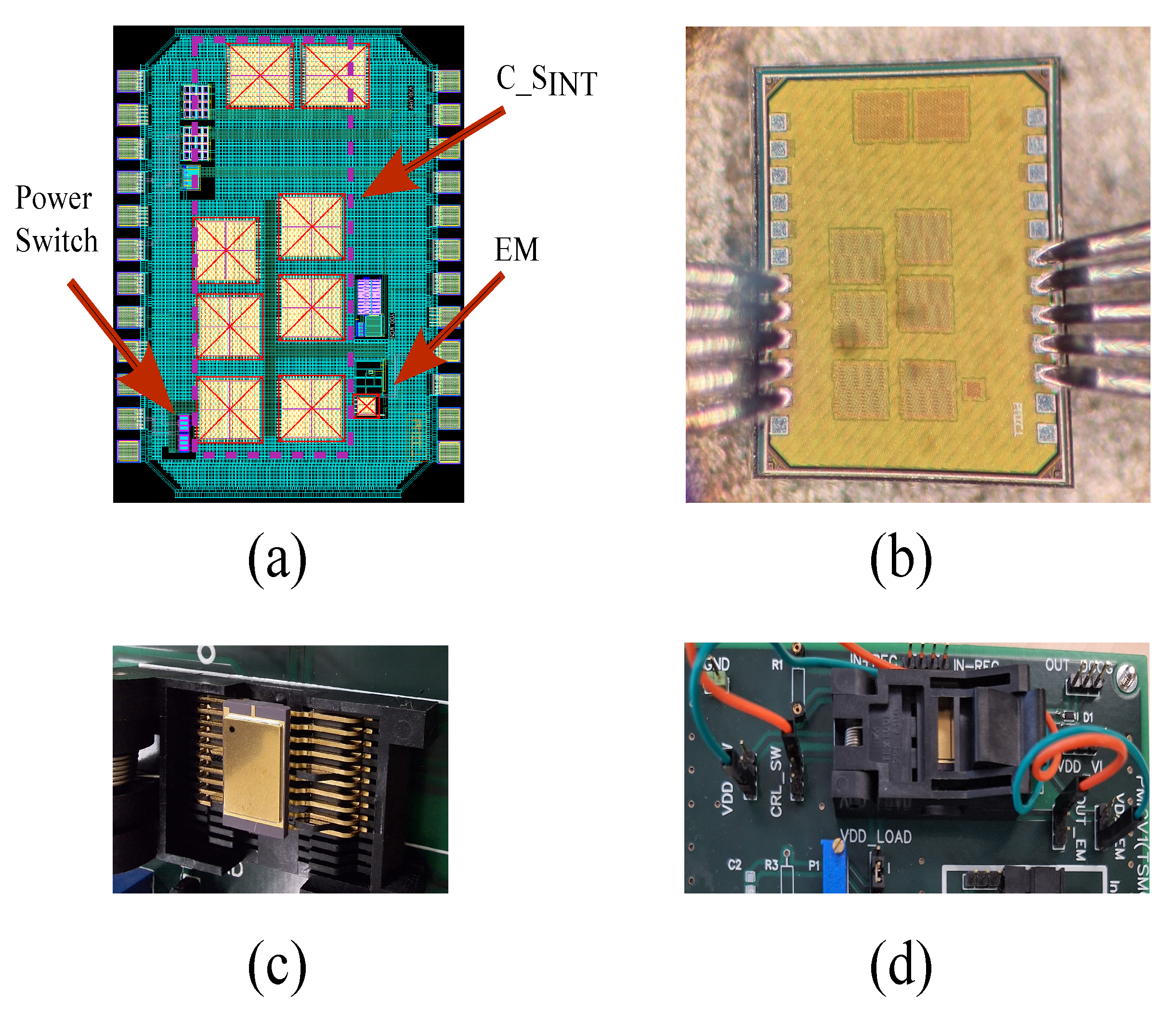

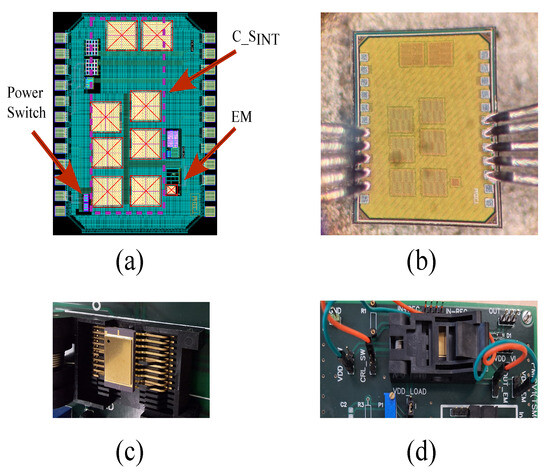

The layout of the proposed circuit is shown in Figure 4a, with a total area of 1.4 mm × 1 mm. In this layout, the EM, power switch, and capacitors are labeled and take approximately 1.2%, 0.13%, and 16.5% of the total die area, respectively. As illustrated, the EM and power switch occupy only a small portion of the die, while the large portion of the area is allocated to the internal storage capacitor, which has a capacitance of approximately 180 pF. To ensure robust operation and minimize leakage and thermal effects, the layout employs a combination of common-centroid placement for matched transistors, guard-ring isolation, and careful positioning of thermally sensitive elements. This layout strategy helps reduce mismatch caused by temperature gradients and parasitic coupling, while maintaining the stability of the EM circuit. The equivalent microphotograph of the fabricated die is presented in Figure 4b. In this image, only the capacitors and bonding pads are visible due to the presence of metal filling layers. To facilitate easier measurements on dies, SOIC-20 packaging was used for the fabricated dies, as shown in Figure 4c. The evaluation printed circuit board (PCB) used to test the proposed circuit is depicted in Figure 4d.

Figure 4.

(a) Full layout of the proposed circuit. (b) Die microphotograph. (c) Prototype packaging of the die. (d) Test board of the proposed circuit.

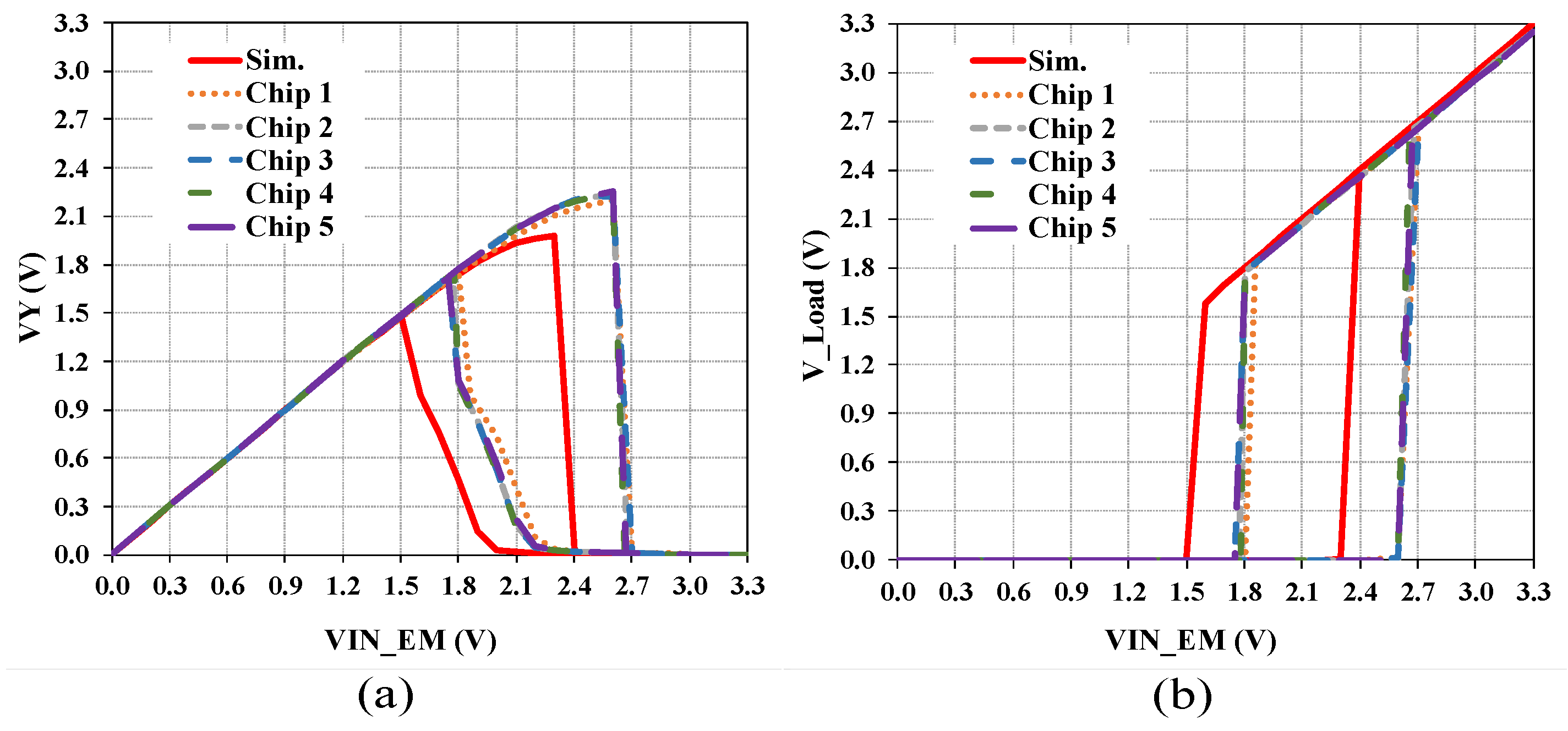

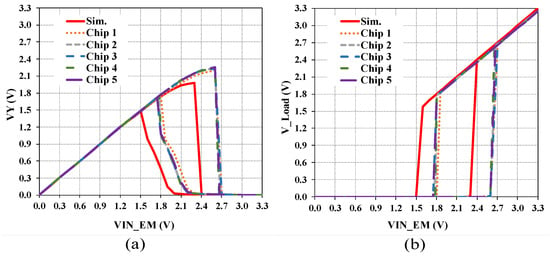

Assessment of the proposed circuit involves analyzing the operating thresholds and . A DC voltage sweep was applied to the EM supply voltage, corresponding to the storage voltage across the capacitor () in typical EH applications. The voltage was swept from 0 V to 3.3 V to determine , and then from 3.3 V down to 0 V to determine . A 10 kΩ external resistor was used as a typical load. Simulation results at 27 °C are shown as solid lines, while measured results from five different chips are indicated with dotted and dashed lines in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

DC input voltage sweep of the EM, showing simulation and measurement: (a) Voltage recorded at node Y. (b) Voltage recorded across a 10 kΩ resistor as a typical load.

In Figure 5a, the voltage at the output node of the EM core (VY) is measured. During the rising phase of VIN_EM, VY closely follows VIN_EM until it reaches the threshold voltage , after which it drops to 0 V to activate the PMOS power switch. Similarly, during the falling phase, from values above , VY remains at 0 V until VIN_EM reaches ; beyond this point, VY once again tracks VIN_EM, ensuring that the load remains disconnected in this configuration. In Figure 5b, the voltage available at the load, which corresponds to the drain terminal of the PMOS power switch, is shown. This voltage has an inverse relationship compared to VY. As shown in Figure 5, the five measured chips show almost identical behavior, except that chip 1 has a slightly higher . As VIN_EM begins to ascend, the measured and simulated values are approximately 2.75 V and 2.45 V, respectively. When VIN_EM descends, the measured and simulated values are around 1.75 V and 1.5 V, respectively.

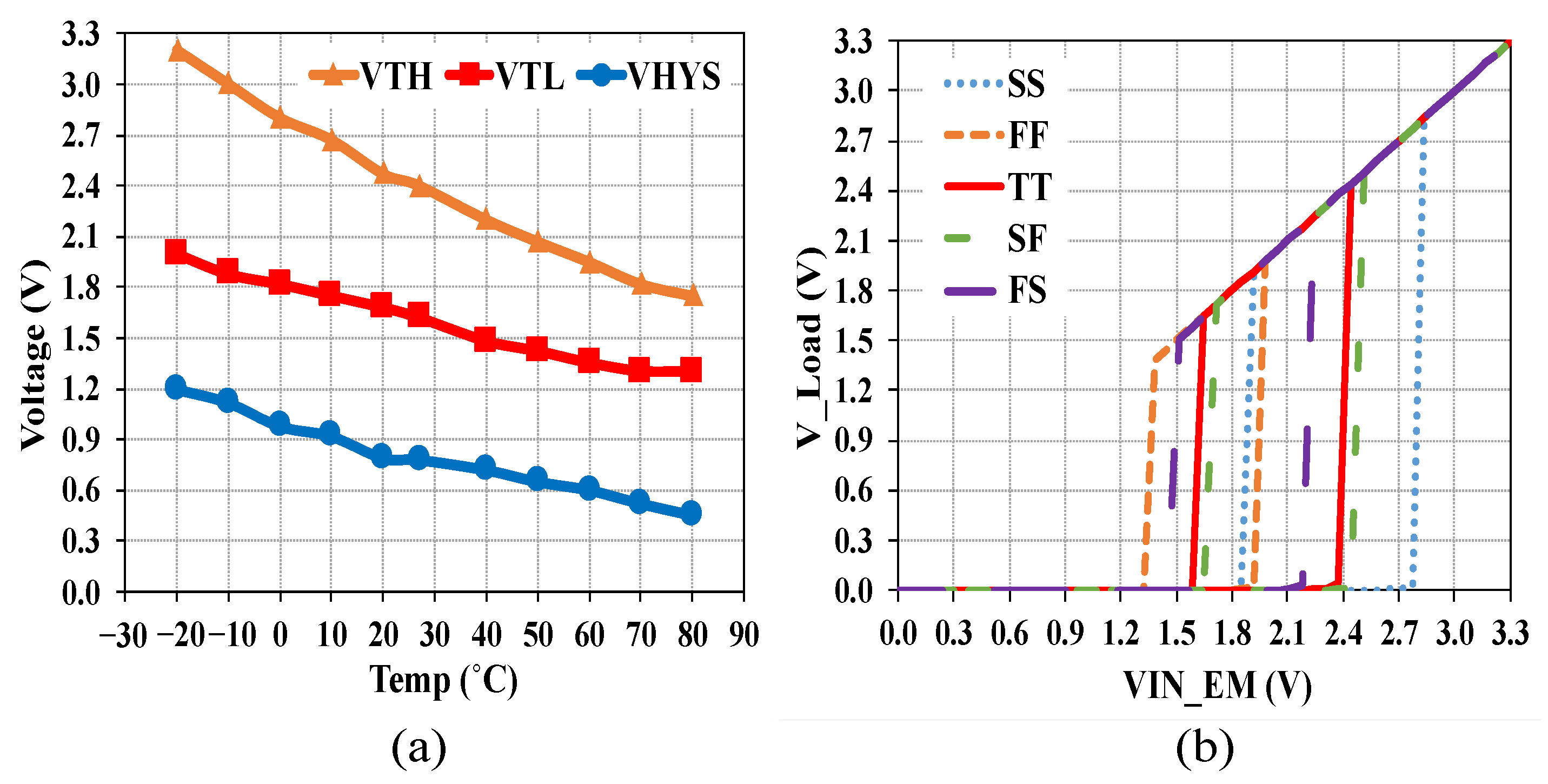

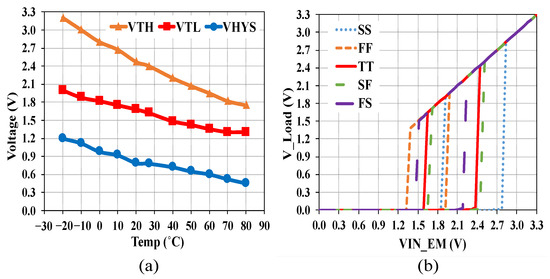

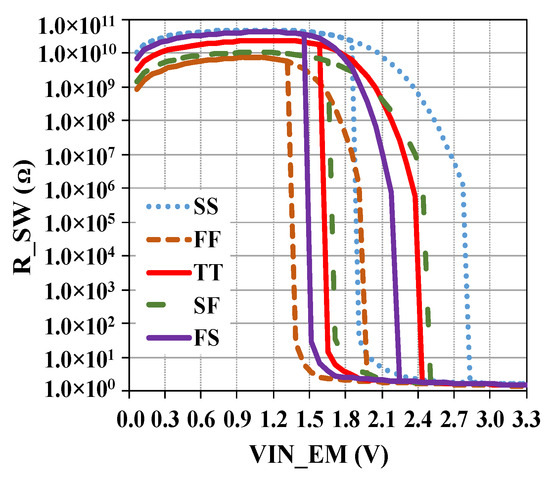

To evaluate different fabrication processes and testing conditions, simulation results at various temperatures and process corners are illustrated in Figure 6. From Figure 6a, it can be seen that the values of , , and hysteresis are higher at lower temperatures and decrease as the temperature rises. Moreover, Figure 6b shows that the threshold values increase toward slower process corners and decrease toward faster corners.

Figure 6.

DC input voltage sweep of the EM with R_Load = 10 KΩ: (a) Thresholds at different temperatures. (b) Thresholds across different process corners.

It is true that there are unavoidable deviations in , ranging from 1.95 V (FF) to 2.85 V (SS), and in , from 1.35 V (FF) to 1.85 V (SS). However, even in the worst-case scenario, a hysteresis of approximately 0.6 V is maintained, which can still supply the required energy based on Equation (1).

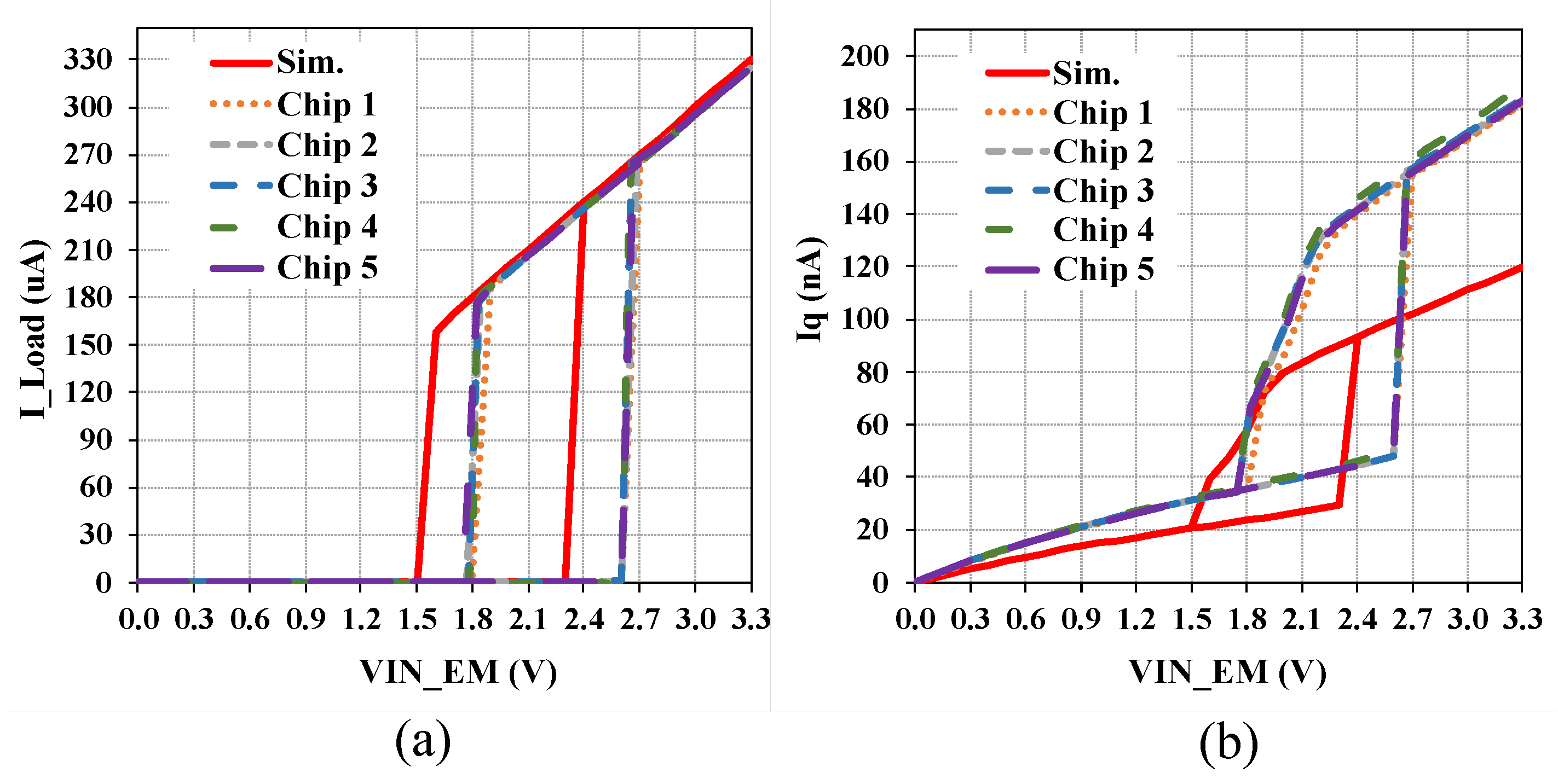

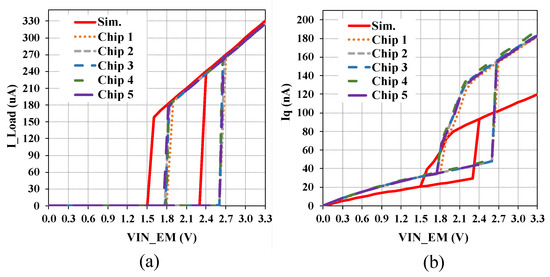

The current measurement results are shown in Figure 7. In this test, a DC voltage sweep was performed to monitor the current consumption. The current sunk by a 10 kΩ resistor as the load is depicted in Figure 7a, with simulation results shown by solid lines and five measured chip samples by dotted and dashed lines. It is clearly observed that as the supply voltage increases, there is no current consumption by the load before reaching . After crossing , the load begins to consume current, effectively consuming most of the supplied power. For instance, at 3 V, the measured current through the load is approximately 300 µA. Similarly, during the descending phase, the load stops consuming current once the voltage drops below .

Figure 7.

DC input voltage sweep of the EM, simulation and measurement: (a) I_Load with R_Load = 10 KΩ. (b) Iq when R_Load is open.

As mentioned earlier, the current consumption of an EM is one of the most critical specifications and is commonly referred to as quiescent current (Iq). To characterize this feature, the EM was tested without a connected load, and the supply current was measured directly. For a more accurate evaluation of the quiescent current of the EM, both rising and falling DC voltage sweeps were performed, as illustrated in Figure 7b. For example, at 3 V, the simulated quiescent current is 111 nA, while the measured value is 170 nA.

Figure 7b shows that the current consumed by the EM remains ultra-low after passing and before reaching . This behavior is a significant advantage of the proposed EM, as it enhances efficiency during the charging phase of the storage capacitor.

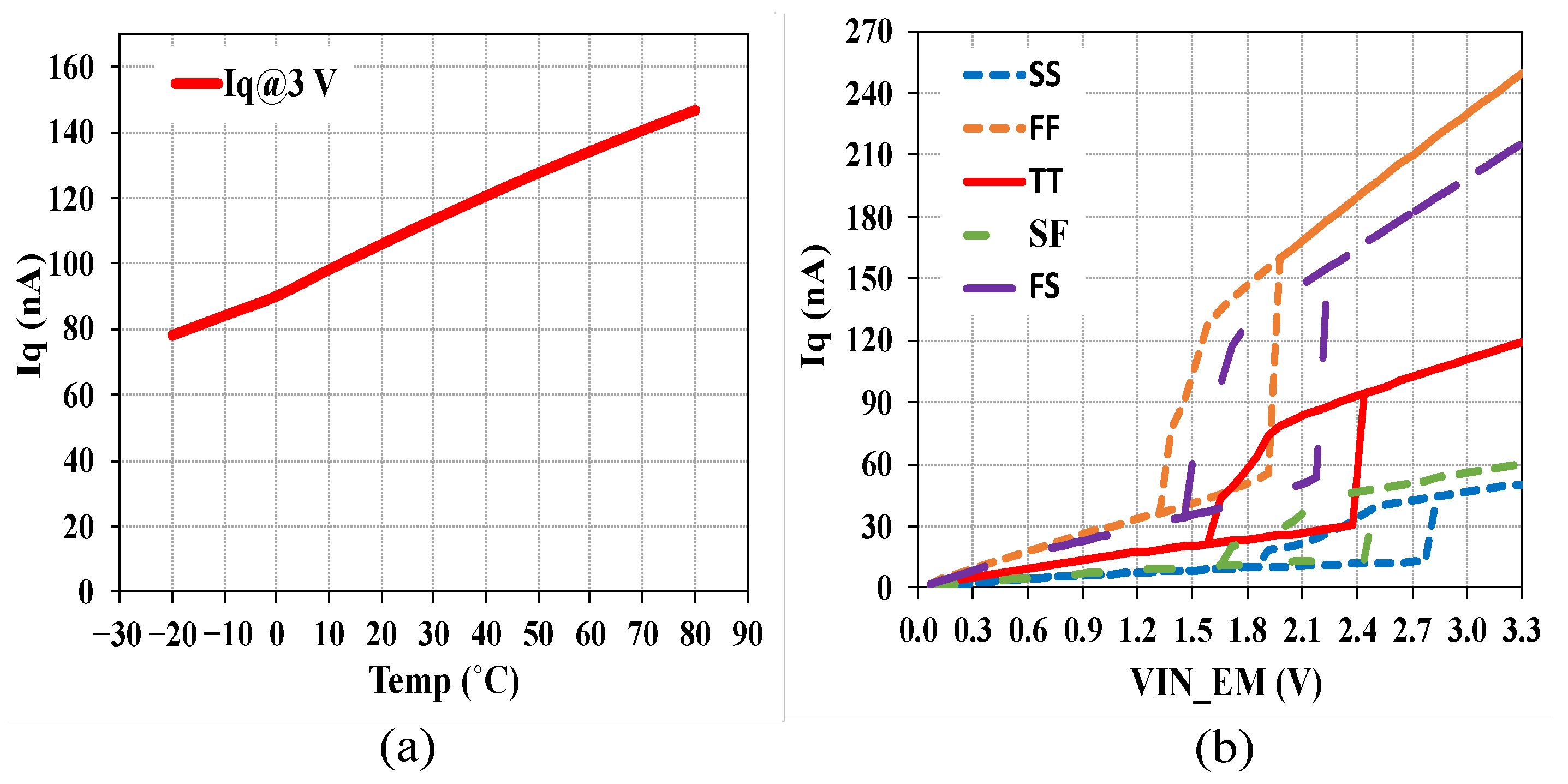

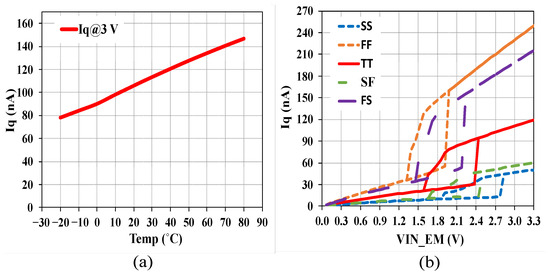

Simulation results for different temperatures and process corners related to Iq are shown in Figure 8. From Figure 8a, it can be observed that Iq decreases at lower temperatures and increases at higher temperatures. For instance, at a supply voltage of 3 V, the value of Iq varies from 77 nA at −20 °C to 147 nA at 80 °C. Regarding process variations, Iq ranges from 47 nA (SS) to 225 nA (FF) at 3 V as depicted in Figure 8b. Taking the TT corner as a reference, the variation in current consumption across other corners is considerable. However, the key point is that the circuit still maintains proper functionality, generating both and , and even in the worst-case (FF corner), the current consumption remains acceptable for many EH applications.

Figure 8.

DC input voltage sweep of the EM when R_Load is open: (a) Iq of the EM at 3 V versus temperature. (b) Iq of the EM across different process corners.

To provide a better quantitative inspection of the circuit behavior, we summarized the simulated values of , , and Iq at critical corners (SS and FF) and at three different temperatures in Table 1.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison of VTH, VTL, and Iq at different corners and temperatures.

To better evaluate the performance of the proposed circuit under process variations and mismatch, Monte Carlo simulations were carried out at 27 °C using 200 samples. The results of this analysis for three key parameters , , and Iq, based on a DC sweep are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Monte Carlo simulation results for DC response.

By considering the mean, standard deviation, and maximum and minimum values for the three parameters , , and Iq, noticeable variations can be observed. However, even in the worst-case scenarios, the differences between and and the value of Iq remain acceptable for energy-limited applications.

When the load is powered through an internal switch, the value of the load resistance can become problematic, especially when it is comparable to the on-resistance of the internal power switch. In this case, a significant voltage drop may develop across the internal switch, leading to a reduced voltage at the load and potentially causing system malfunction.

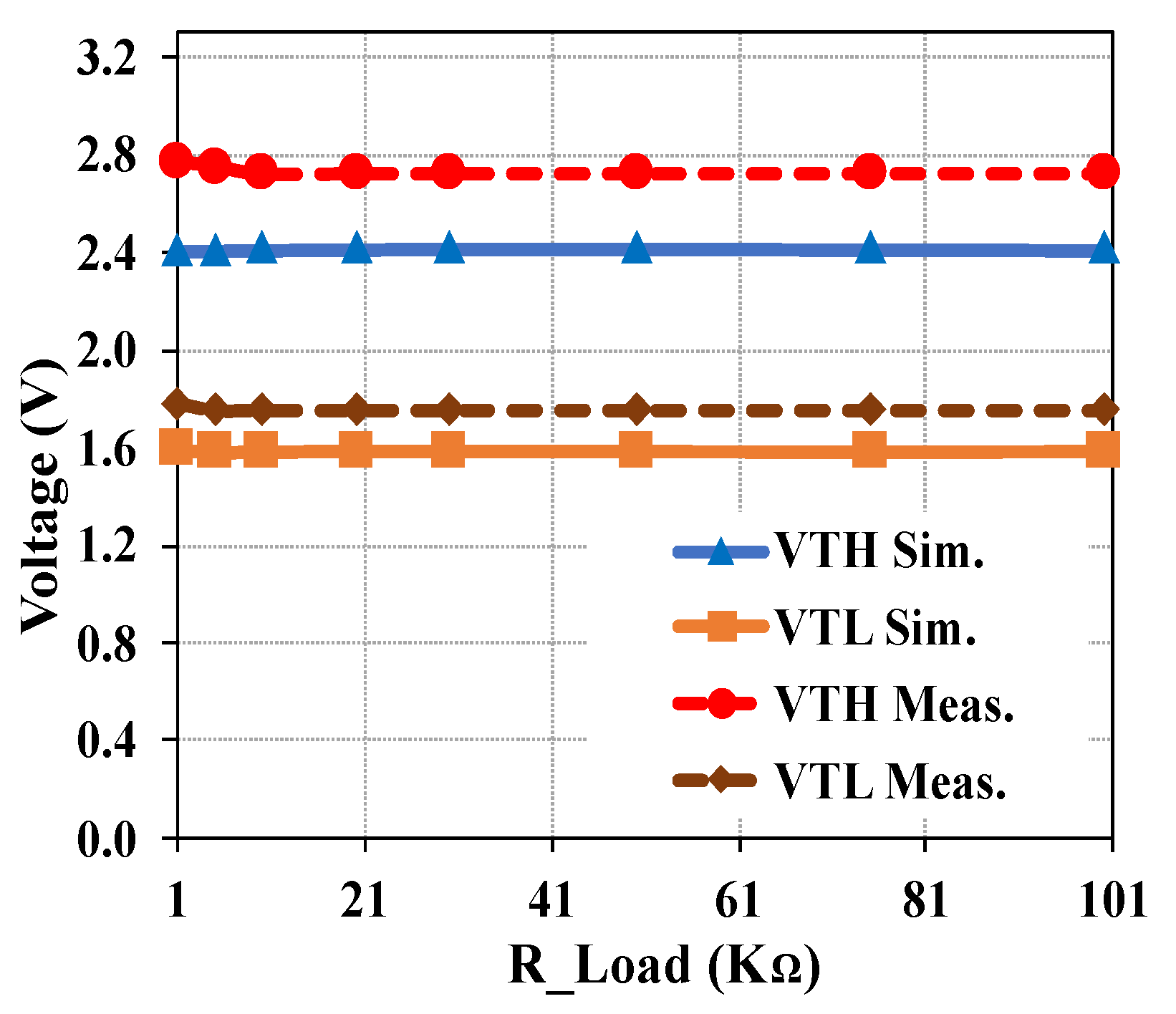

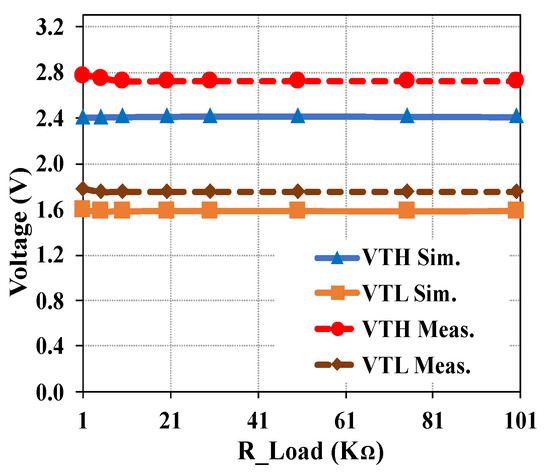

Figure 9 illustrates the effect of load resistance on the and values. The threshold levels remain nearly constant for load resistances ranging from 1 kΩ to 100 kΩ, indicating that the proposed circuit maintains stable performance across this range. This demonstrates the reliable operation of the EM with an internal power switch under varying load resistance conditions.

Figure 9.

Effect of load resistance value on and with simulation and measurement.

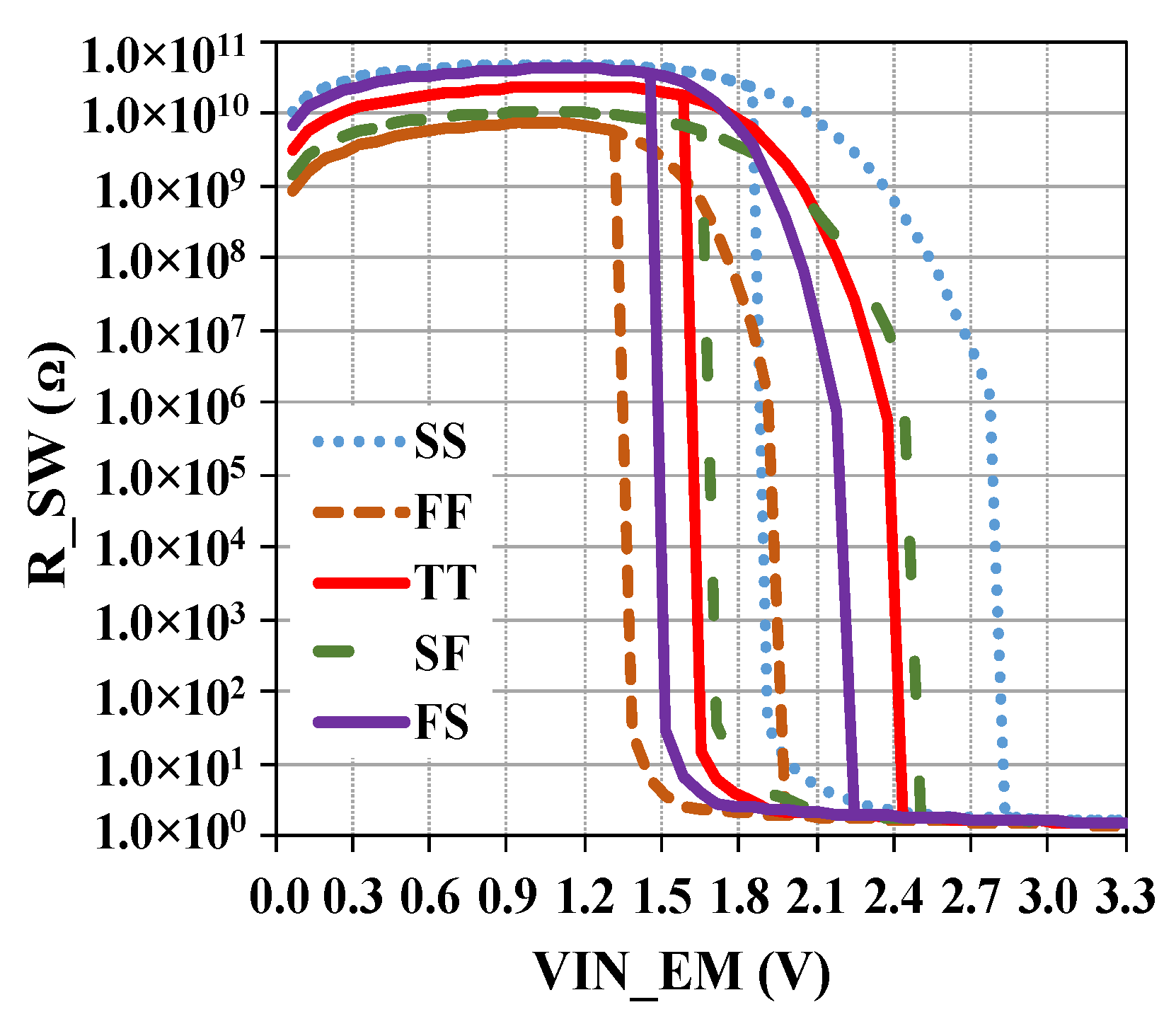

To gain a deeper understanding of the power switch operation, Figure 10 illustrates the resistance behavior of the switch. These simulation results were obtained across different process corners by performing a DC sweep of the supply voltage, using a 10 kΩ resistor as the load. During the rising phase of VIN_EM, the switch resistance remains high before reaching . As the supply voltage approaches level, the resistance gradually decreases but remains significantly higher than the load resistance, indicating that the switch can still be considered off. Once is reached, the switch resistance drops sharply to just a few ohms or less, allowing current to flow through the load. In the falling phase of VIN_EM, the switch stays fully on with low resistance until is reached. After this threshold, the switch turns off and the resistance becomes very high again.

Figure 10.

Resistance value of the power switch at different input voltage levels across process corners.

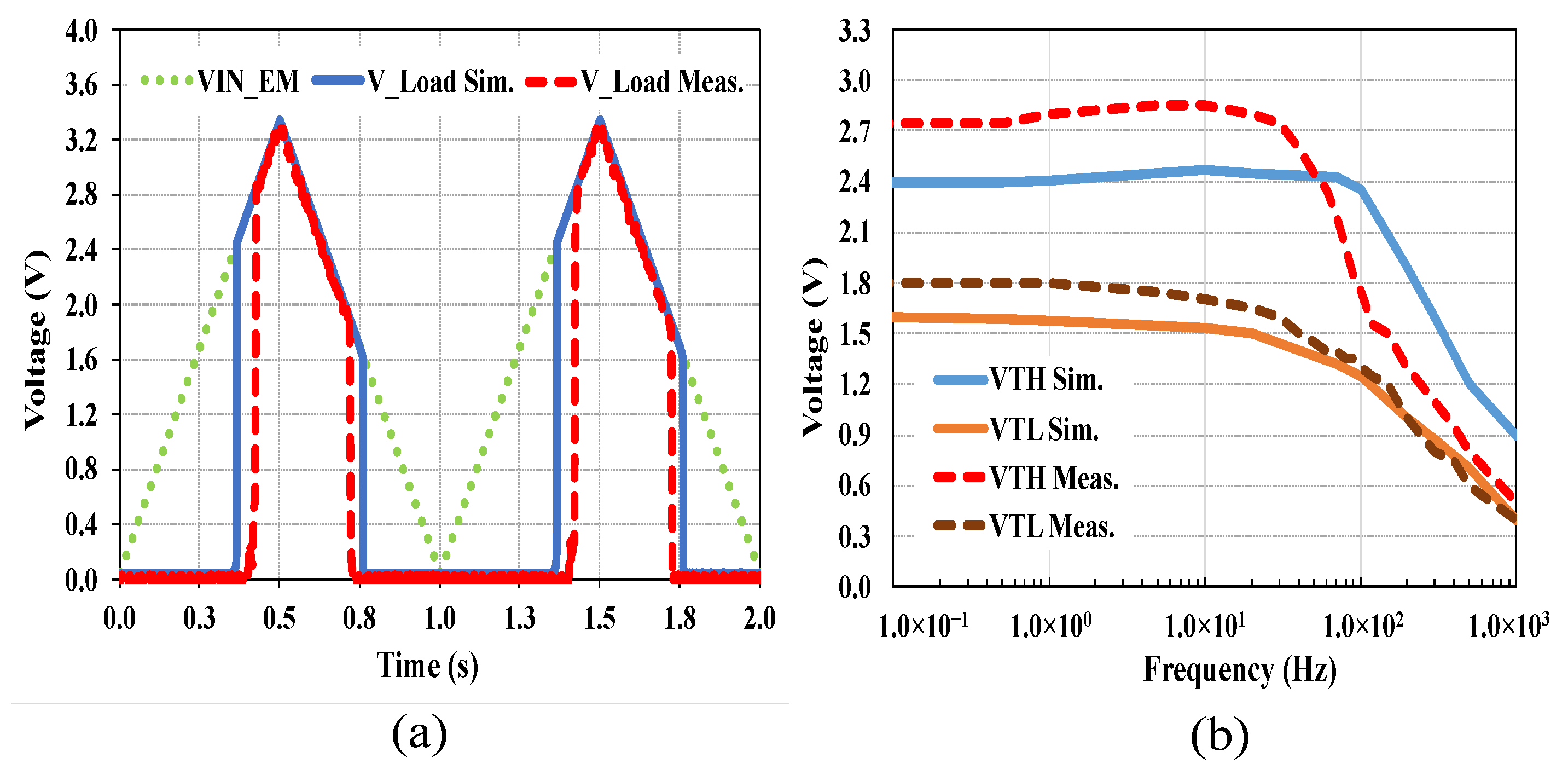

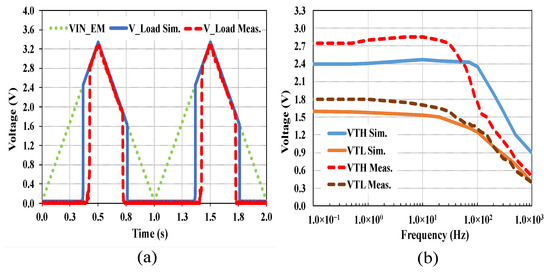

Generally, for EH applications, the evaluation and characterization of an EM are based on DC sweeps, since the voltage change rate across the storage capacitor is very slow and can often be approximated as a DC voltage. Accordingly, the simulations and measurements conducted so far have relied on DC sweeps. To further assess the proposed EM, Figure 11 illustrates the threshold levels under various VIN_EM frequency conditions.

Figure 11.

Response of the EM to triangular inputs, simulation and measurement: (a) Transient response. (b) Threshold levels at different frequencies.

A triangular input signal with a time period of 1 s is applied to the EM, as shown by the dotted lines in Figure 11a. To assess the response, both simulated and measured output waveforms of the proposed circuit using a 10 kΩ resistive load are presented. The and values obtained from simulation and measurement closely match those in Figure 5b, indicating that the performance of the proposed circuit at an input frequency of 1 Hz is effectively equivalent to that under a DC input.

To provide a clearer understanding, the frequency of the triangular signal applied to the input of the EM was varied from 0.1 Hz to 1 kHz to evaluate the frequency-dependent behavior, as shown in Figure 11b. The value remains nearly constant up to 100 Hz in simulation and 30 Hz in measurement. Similarly, stays steady up to 20 Hz in simulation and 10 Hz in measurement. This behavior aligns well with the needs of EH applications, mainly due to the presence of a storage capacitor, which significantly reduces the voltage change rate. Although a considerable reduction in both threshold levels is observed at higher frequencies, a hysteresis voltage window still exists, ensuring correct switching behavior for energy storage based on Equation (1).

Similar to the DC sweep, Monte Carlo simulations were performed for the transient response of the proposed circuit. Results for three different frequencies within the range shown in Figure 11b are summarized in Table 3. The obtained values confirm that a hysteresis voltage gap persists even at higher frequencies, further validating the functionality of the proposed EM in applications where supply voltage changes occur faster than expected in EH systems.

Table 3.

Monte Carlo simulation results for transient response.

Table 4 summarizes the most relevant state-of-the-art EMs, highlighting their technologies, implementation techniques, the presence of power switches, and key performance metrics, including hysteresis behavior and power consumption. As observed, latch-based structures stand out for their simplicity and ultra-low power consumption. However, because they rely on high-value resistors, designs employing them are typically implemented off-chip. Among commercial solutions, the XC6140 [12] from Torex Semiconductor exhibits remarkably low current consumption, comparable to that of our proposed design. However, unlike our circuit, it consumes more power at lower voltages, even when the load is disconnected. To illustrate this, during the capacitor charging process from 0 V to , the XC6140 datasheet [12] reports currents of 30 nA, 80 nA, 107 nA, 123 nA, and 138 nA at 0.5 V, 1 V, 1.5 V, 2 V, and 2.5 V, respectively, whereas the proposed EM, as shown in Figure 7b, consumes only 12 nA, 23 nA, 31 nA, 38 nA, and 45 nA at the same voltages. This lower current consumption of the EM during the charging phase is an important factor in shortening the time needed to reach , improving the overall efficiency of the EM, and making it more suitable for energy-limited EH systems.

Table 4.

Comparison of the Proposed EM with related works.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents an ultra-low-power, robust EM circuit, designed and fabricated using a 65 nm CMOS standard process. The proposed EM has a simple architecture, consisting of a latch-based core and a high-resistance voltage divider. Thanks to this configuration, it eliminates the need for additional circuits such as voltage references, comparators, and logic control units, resulting in significantly lower power consumption. Additionally, simulation results at different temperatures and across various process corners, considering the effects of mismatch, demonstrate the robustness of this circuit.

Traditionally, ultra-low-power EMs use off-chip voltage dividers to obtain high resistance values, as implementing such large passive resistors on-chip is impractical. In this work, a high-resistance voltage divider is implemented on-chip using a series of diode-connected zero-threshold NMOS transistors. This approach enables the realization of extremely high resistances in a compact area, without any additional power consumption. Although this method can lead to resistance inaccuracy under different fabrication and test conditions, both simulation and measurement results indicate that the performance of the proposed EM remains within acceptable specifications. The measured threshold voltages are approximately 2.75 V () and 1.75 V (). The quiescent current at is 160 nA, and the hysteresis voltage is about 1 V, making the design well suite for energy-constrained applications. The circuit operates properly when the storage voltage varies at frequencies of a few hertz. It also maintains functionality at higher frequencies due to the hysteresis window, which ensures reliable load triggering once the minimum required voltage of the load is met. The proposed circuit also includes a PMOS power switch to eliminate the need for an external switching component.

Finally, the proposed EM circuit has strong potential for integration into energy-limited PDNs and chiplet-based systems, where the low quiescent current helps maintain local voltage stability and prevent malfunction under dynamic operating conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and A.B.; methodology, M.S. and H.S.; software, M.S. and A.B.; validation, A.B. and H.S.; formal analysis, M.S. and A.B.; investigation, M.S., A.B. and N.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, A.B. and N.P.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, A.B. and N.P.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the HORIZON-EIC-2022-PATHFINDERCHALLENGES-01 project Blood2Power (Grant Agreement No. 101115525), funded by the European Union. This work is also supported by the ELKARTEK ENHARPE project (KK-2024/00104), funded by the Basque Government (Spain).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EM | Energy Management |

| PMIC | Power Management Integrated Circuit |

| EH | Energy Harvesting |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| WSN | Wireless Sensor Network |

| LDO | Low-Dropout Regulator |

| PDN | Power Delivery Network |

| PCB | Printed Circuit Board |

References

- Peng, W.; Du, S. The advances in conversion techniques in triboelectric energy harvesting: A review. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2023, 70, 3049–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Fu, M.; Liang, J. A three-transistor energy management circuit for energy-harvesting-powered iot devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, S.; Gao, W.; Zhang, J.; Xu, D.; Chen, F.; Lu, Z.; Yu, X. A High-Efficiency Piezoelectric Energy Harvesting and Management Circuit Based on Full-Bridge Rectification. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2024, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Miao, L.; Song, Y.; Su, Z.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. High efficiency power management and charge boosting strategy for a triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2017, 38, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solar, H.; Beriain, A.; Berenguer, R.; Sosa, J.; Montiel-Nelson, J.A. Semi-passive UHF RFID sensor tags: A comprehensive review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 135583–135599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Gasso, A.; Beriain, A.; Solar, H.; Berenguer, R. Power Management Unit for Solar Energy Harvester Assisted Batteryless Wireless Sensor Node. Sensors 2022, 22, 7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Ma, T. Passive power management for triboelectric nanogenerators in sub-microwatt applications. Nano Energy 2024, 119, 109079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.; Liang, J.; Du, S. A nano-power wake-up circuit for energy-driven IoT applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Austin, TX, USA, 27 May–1 June 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 2383–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghisi, D.; Ferrari, V.; Ferrari, M.; Touati, F.; Crescini, D.; Mnaouer, A.B. A new nano-power trigger circuit for battery-less power management electronics in energy harvesting systems. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2017, 263, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Wei, R.; Zhao, L.; Yang, X.; Geng, L.; Feng, P.X.L. An ultralow quiescent current power management system with maximum power point tracking (MPPT) for batteryless wireless sensor applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 7326–7337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analog Devices Inc. LTC3588-1 Datasheet: Nanopower Energy Harvesting Power Supply. Analog Devices Inc., Document No. LTC3588-1, Rev. E. 2020. Available online: https://www.analog.com/media/en/technical-documentation/data-sheets/35881fc.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Torex Semiconductor Ltd. XC6140 Series Datasheet: Voltage Monitoring IC for Energy Harvesting Applications. Torex Semiconductor Ltd., Document No. XC6140, Rev. 1.0. 2022. Available online: https://product.torexsemi.com/system/files/series/xc6140.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Chew, Z.J.; Ruan, T.; Zhu, M. Power management circuit for wireless sensor nodes powered by energy harvesting On the synergy of harvester and load. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 34, 8671–8681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrarathna, S.C.; Graham, S.A.; Ali, M.; Ranaweera, A.L.A.K.; Karunarathne, M.L.; Yu, J.S.; Lee, J.W. Analysis and Experiment of Self-Powered, Pulse-Based Energy Harvester Using 400 V FEP-Based Segmented Triboelectric Nanogenerators and 98.2% Tracking Efficient Power Management IC for Multi-Functional IoT Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.K.; Tam, W.S.; Kok, C.W. A Current Comparison Based Voltage Supervisory Circuit with On-Chip Detection Voltage Trimming. Solid State Electron. Lett. 2021, 3, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Chekuri, V.C.K.; Rahman, N.M.; Dolatsara, M.A.; Torun, H.M.; Swaminathan, M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Lim, S.K. Chiplet/interposer co-design for power delivery network optimization in heterogeneous 2.5-D ICs. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 11, 2148–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texas Instruments. CC1310 SimpleLink Ultra-Low-Power Sub-1 GHz Wireless Microcontroller; Texas Instruments Inc., 2018. Available online: https://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/cc1310.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Texas Instruments. MSP430x2xx Family Datasheet; Texas Instruments Inc. Available online: https://www.ti.com/product-category/microcontrollers-processors/msp430-mcus/products.html (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Ishibashi, K.; Takahashi, S. A 375 nA Input Off Current Schmitt Triger LDO for Energy Harvesting IoT Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), Hong Kong, China, 8–11 July 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).