Abstract

Fe–Al intermetallic compounds are promising candidates for hydrogen permeation barrier coatings owing to their excellent oxidation stability and inherent resistance to hydrogen embrittlement. However, the mechanical properties and interfacial behavior of different Fe–Al phases, particularly at Fe/Fe–Al interfaces, remain insufficiently understood, limiting their reliable application in hydrogen-containing environments. In this work, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to systematically evaluate the bulk mechanical moduli, surface energetics, and interfacial adhesion of FeAl, Fe3Al, and Fe2Al5. The results reveal that FeAl exhibits the highest elastic and shear moduli due to its B2-ordered structure and directional bonding, while Fe2Al5 shows pronounced anisotropy and the lowest strength as a consequence of its low-symmetry structure. Surface energy analysis indicates that Fe2Al5 possesses relatively stable facets, whereas interfacial adhesion calculations demonstrate that FeAl/Fe and Fe3Al/Fe interfaces provide significantly stronger bonding compared to Fe2Al5/Fe. Charge density and electron localization function (ELF) analyses confirm that Fe–Fe bonds are dominated by metallic character with delocalized electrons, whereas Al-rich regions display enhanced localization, leading to weaker interfacial adhesion in Fe2Al5/Fe. These findings clarify the fundamental mechanisms governing Fe–Al mechanical and interfacial properties and provide theoretical guidance for the design of robust Fe–Al-based hydrogen barrier coatings.

1. Introduction

Hydrogen is increasingly recognized as a pivotal clean energy carrier in the global transition toward decarbonization, owing to its high energy density and zero-carbon combustion products. However, its large-scale utilization remains constrained by severe issues such as hydrogen embrittlement (HE) and material degradation, which can compromise the integrity and safety of critical infrastructures [1,2,3]. In particular, steels used in hydrogen transport pipelines, tubular goods, storage vessels, and other pressurized components are highly susceptible to HE, so ensuring reliable hydrogen barrier performance at their surfaces is a key prerequisite for safe operation. To mitigate hydrogen ingress and associated failures, a variety of hydrogen permeation barrier coatings have been developed, including ceramic, metallic, and composite systems [4,5].

Among these, Fe–Al intermetallic compounds have emerged as particularly promising candidates. When combined with an alumina (Al2O3) surface scale, Fe–Al coatings exhibit excellent hydrogen resistance, high oxidation stability, and dense lattice structures, making them attractive for demanding environments in energy and chemical industries [2,6]. These intermetallic phases are typically produced by aluminization treatments, during which Fe and Al interdiffusion generates Fe–Al transition layers whose interfacial cohesion and mechanical integrity are expected to strongly affect the effective hydrogen permeation barrier; however, the mechanical and interfacial properties of these transition layers have not yet been systematically quantified by atomistic calculations [7]. At the Fe/Fe–Al interfaces, disparities in crystal symmetry, thermal expansion coefficients, and bonding characteristics can induce residual stresses, weak adhesion, and electronic inhomogeneity. Such features may act as preferential sites for crack initiation and hydrogen trapping, ultimately reducing coating durability [3,8].

To address these gaps, this study employs first-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) to investigate the bulk, surface, and interfacial properties of FeAl, Fe3Al, and Fe2Al5. Specifically, we evaluate their elastic and shear moduli, surface energies, and interfacial adhesion, and further elucidate the bonding nature using charge density and electron localization function (ELF) analyses. The findings provide fundamental insights into the hydrogen resistance mechanisms of Fe–Al intermetallics and establish a theoretical basis for the design of robust Fe–Al-based hydrogen barrier coatings.

2. Computational Methods

All calculations were carried out using density functional theory (DFT) [9] as implemented in the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP) [10]. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional [11] was employed to describe exchange–correlation effects, and the projector augmented wave (PAW) method [12] was used for electron–ion interactions. A plane-wave kinetic-energy cutoff of 500 eV [13] with a k-point spacing of 0.02 (2π Å−1) were adopted, as convergence tests confirmed that these settings lead to changes in total energy below 10−3 eV per atom and yield converged mechanical and interfacial properties for the Fe–Al systems studied. Structural relaxations and self-consistent field (SCF) calculations were performed with the Methfessel–Paxton smearing method [14] (0.1 eV width), applying convergence criteria of 10−6 eV for total energy and 5 × 10−3 eV Å−1 for atomic forces. For electronic density of states (DOS), the Blöchl-corrected tetrahedron method [15] was adopted. Elastic constants were obtained via the stress–strain approach, and bulk, shear, and Young’s moduli as well as Poisson’s ratios were derived using the Voigt approximation. For all surface and interface calculations, slab models were separated by a vacuum region of 15 Å along the surface normal, which is sufficient to suppress interactions between periodic images.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Bulk Structure and Mechanical Properties

To validate the reliability of the computational models employed in this study, structural optimizations were performed for pure Fe and three representative Fe–Al intermetallic compounds: FeAl, Fe3Al, and Fe2Al5 The optimized model is reasonably consistent with previously reported theoretical and experimental values, as shown in Table 1, confirming the reliability of the calculated parameters, which are therefore used in the subsequent calculations [16,17,18,19].

Table 1.

Optimized lattice parameters (Å) for Fe and Fe–Al intermetallics, compared with representative literature values.

Based on the generalized Hooke’s law, the elastic constants of the Fe–Al binary intermetallic compounds were determined via the stress–strain method. A series of distinct strain modes were applied to the optimized crystal structures, and the corresponding Cauchy stress tensors were evaluated for each deformation configuration. The relevant elastic constants were subsequently extracted based on the linear stress–strain relationships defined by the applied strain modes [20].

Here,

represents the normal stress,

denotes the shear stress,

are the elastic constants, while

and

correspond to the normal and shear strains, respectively. The total number of independent elastic constants is dictated by the symmetry of the crystal. For high-symmetry systems, the number of distinct strain modes required to compute the full set of

can be significantly reduced, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The calculated stiffness matrix parameters of Fe and Fe-Al compounds.

By comparing the stiffness matrix parameters of Fe, FeAl, Fe3Al, and Fe2Al5, significant differences in mechanical properties among these materials can be observed. Fe exhibits the highest stiffness, particularly in the tensile and compressive directions (C11, C22, C33), while its shear stiffness components (C44, C55, C66) are relatively lower. FeAl shows a slightly reduced overall stiffness compared to Fe, but demonstrates a notable enhancement in shear stiffness, indicating improved shear resistance, making it suitable for applications requiring high shear strength. The mechanical properties of Fe3Al lie between those of Fe and FeAl, exhibiting a well-balanced performance in both tensile/compressive and shear stiffness, which suggests its advantage in applications demanding moderate impact resistance and wear protection, such as functional coatings. In contrast, Fe2Al5 shows significantly lower values in both tensile/compressive and shear stiffness, indicating its suitability for low-load coating environments. Notably, the stiffness coefficients of Fe2Al5 (e.g., C11, C12, C13, C44, C66) reveal pronounced anisotropy. The low symmetry of its crystal structure leads to substantial directional variations in mechanical response, in stark contrast to the more uniform stiffness distributions observed in Fe, FeAl, and Fe3Al. This reflects the inhomogeneous nature of interatomic interactions in Fe2Al5.

The observed differences in stiffness can be fundamentally attributed to variations in interatomic interactions, electronic structure, and crystal symmetry. The high stiffness of pure Fe primarily stems from the strong metallic bonding inherent in its body-centered cubic (BCC) crystal structure. These dense interatomic interactions endow Fe with high elastic stiffness coefficients and excellent resistance to deformation. With the incorporation of Al, the presence of Al atoms in FeAl alloys weakens the metallic bonding strength within the lattice, resulting in a decrease in overall stiffness. Concurrently, the addition of Al alters the shear deformation mechanisms, significantly enhancing the material’s resistance to shear—an effect particularly pronounced in FeAl and Fe3Al. As the Al content increases further in Fe3Al and Fe2Al5, the crystal symmetry is reduced, and the interatomic interactions become increasingly directional, leading to marked anisotropy in the stiffness coefficients. This effect is especially evident in Fe2Al5, where the complex atomic arrangement and low symmetry give rise to substantial directional variations in mechanical response, further diminishing the overall stiffness. These observations highlight the critical role of Al content and crystal structure in tailoring the mechanical properties of Fe–Al intermetallic compound (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Calculated bulk modulus B, Young’s modulus E, shear modulus G, Poisson’s ratio ν, Zener anisotropy factor Az (for cubic phases), and Al atomic percentage for Fe, Fe3Al, FeAl, and Fe2Al5. Az is not defined for the orthorhombic Fe2Al5 phase.

The mechanical properties obtained from the Voigt model show that Al content has a pronounced effect on the Fe–Al intermetallics. With increasing Al concentration, both Young’s modulus and shear modulus increase from Fe to Fe3Al and FeAl, while the bulk modulus decreases and Poisson’s ratio decreases monotonically. This indicates that Al addition enhances stiffness and shear resistance but reduces compressibility and ductility. Among the investigated phases, FeAl exhibits the highest Young’s and shear moduli, consistent with its B2 ordering and strong directional Fe–Al bonding. Fe3Al ranks second in stiffness, reflecting the strengthening effect of DO3 chemical ordering on a BCC-like lattice, whereas pure Fe, despite its high symmetry, shows slightly lower moduli due to the absence of such ordering. Fe2Al5, in contrast, has the lowest bulk, shear and Young’s moduli, which is attributed to its low-symmetry orthorhombic (Cmcm) structure and complex atomic arrangement that weaken the overall bonding stiffness.

The elastic anisotropy of the cubic phases was quantified by the Zener factor [21].

The values

for Fe and

for FeAl indicate moderate elastic anisotropy, while Fe3Al exhibits a much larger Zener factor of

, revealing a strongly anisotropic elastic response associated with DO3 ordering. For the orthorhombic Fe2Al5 phase, a cubic-type Zener ratio is not defined; here its mechanical behavior is therefore discussed primarily in terms of the reduced moduli and low Poisson’s ratio, which together suggest a comparatively brittle response.

3.2. Slab Structure and Surface Energy of Fe–Al Compounds

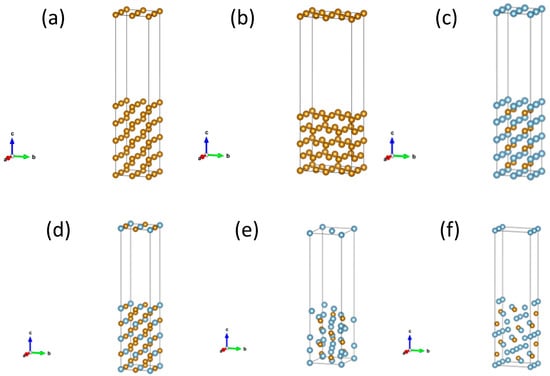

To investigate the interfacial structures formed between various Fe–Al intermetallic compounds and suitably oriented Fe surfaces, supercell and surface models were constructed for the (001) surface of FeAl, the (001) surface of Fe3Al, the (001) and (0

0) surfaces of Fe2Al5, as well as the (001) and (110) surfaces of Fe as shown in Figure 1. In this work, we restrict our analysis to low-index surfaces that are thermodynamically favorable and frequently reported in Fe/Fe–Al coating systems. For bcc Fe, the (110) and (001) surfaces are widely used reference orientations due to their relatively low surface energies and simple atomic arrangements. For B2-FeAl and DO3-Fe3Al, the (001) terminations provide highly symmetric surfaces that can form nearly coherent interfaces with Fe(001). For orthorhombic Fe2Al5, we focus on the (001) and (0

0) facets, which are consistent with experimentally reported Fe2Al5(0

0)/Fe(110) orientation relationships and enable construction of interfaces with small lattice mismatch [15]. Structural optimizations were performed for the supercell and surface models, and the corresponding surface energies were subsequently calculated [22].

Figure 1.

Atomic model of the (a) Fe (001) surface, (b) Fe (110) surface, (c) FeAl (001) surface, (d) Fe3Al (001) surface, (e) Fe2Al5 (001) surface, (f) Fe2Al5 (020) surface. The black lines denote the unit cell. The Fe and Al atoms are displayed in yellow and blue colors.

The

represents the total energy of the surface structure,

denotes the total energy per atom or molecule in the bulk phase, n is the number of atoms or molecules contained in the surface structure, and A is the area of the corresponding surface. Therefore, γ provides a direct measure of the average energy cost per broken bond at the surface, including the extent to which this energy can be partially recovered by surface relaxation.

As shown in Table 4, the surface energies of different Fe–Al intermetallic compounds exhibit clear phase- and orientation-dependent trends. This behavior can be rationalized from three aspects. First, according to Equation (3), γ is the excess energy associated with breaking Fe–Fe and Fe–Al bonds and partially recovering this energy by surface relaxation. The relatively high surface energies of Fe(001), FeAl(001) and Fe3Al(001) indicate a larger average penalty per broken bond, which is consistent with strong metallic bonding in these phases. Second, the ordered B2-FeAl and DO3-Fe3Al structures provide relatively dense and highly coordinated (001) terminations, whereas the orthorhombic Fe2Al5 (Cmcm) exposes more open, Al-rich, low-coordination sites along the (001)/(0

0) facets that can undergo pronounced relaxation and rebonding, thereby lowering γ. Third, as will be discussed in Section 3.3, Bader charge density and ELF analyses reveal stronger electron localization and bonding heterogeneity at Fe2Al5 surfaces and interfaces, which further facilitates such relaxation and is consistent with their comparatively low surface energies.

Table 4.

Surface orientations, surface areas, and surface energies of Fe and Fe–Al intermetallic compounds.

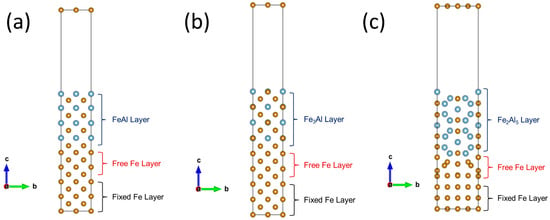

For the FeAl/Fe and Fe3Al/Fe interfaces, FeAl(001)/Fe(001) and Fe3Al(001)/Fe(001) configurations were selected as the research objects due to their high symmetry, well-ordered atomic arrangements, and minimal lattice mismatch resulting from the close similarity in lattice parameters of the two materials. These characteristics facilitate the construction of well-defined interface models and effectively reduce boundary effects.

In addition, the selection of the Fe2Al5/Fe interface was based on experimental observations indicating that the orientation relationship between Fe2Al5 and Fe is not unique. To simplify the computational process and more accurately reflect practical conditions, low-index or close-packed planes are typically chosen for modeling. Previous work has shown that the Fe2Al5(0

0)/Fe(110) interface contains relatively few atoms and has a small lattice mismatch, so this configuration was adopted here. The lattice mismatch of each interface model was then calculated using Equation (4) [23].

where

and

represent the interplanar spacings along the (hkl) crystallographic directions on either side of the interface, while K and L are integer coefficients used to describe the lattice matching relationship at the interface.Based on this approach, the calculated lattice mismatches for the FeAl(001)/Fe(001), Fe3Al(001)/Fe(001), and Fe2Al5(0

0)/Fe(110) interfaces are 1.413%, 1.41%, and 1.85%, respectively. The optimized interface structures are illustrated in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Atomic models of the (a) FeAl (001)/Fe (001), (b) Fe3Al (001)/Fe (001) and (c) Fe2Al5 (00)/Fe (110) interface , showing the layered atomic arrangement used for hydrogen diffusion calculations. The black lines denote the unit cell. The Fe and Al atoms are displayed in yellow and blue colors.

The work of adhesion (

) is a critical physical quantity used to characterize the interfacial bonding strength between two materials. It is defined as the energy required to separate the two materials at the interface into two free surfaces. The value of

can be expressed by Equation (5) [15]:

where

denotes the work of adhesion;

and

denote the surface energies of materials α and β, respectively;

is the total energy of the α/β interface system; and S is the interfacial area.

In the present study, full atomic relaxation and self-consistent field (SCF) calculations were performed to obtain the total interfacial energies and the surface energies of the individual free surfaces. Based on these results and Equation (4),

of different Fe–Al compound/Fe interfaces was quantitatively evaluated, providing insight into the interfacial bonding strength. All calculations were conducted using consistent computational parameters to ensure the reliability and comparability of the results.

These results indicate that both interfaces exhibit strong interfacial bonding and comparable interfacial stability. Such behavior is consistent with the crystallographic characteristics of FeAl and Fe3Al, where the directional Fe–Al bonding in FeAl contributes to strong adhesion, while the synergistic interaction of Fe–Fe and Fe–Al bonds in Fe3Al further enhances the interfacial bonding strength. The similar cross-sectional areas of both models suggest consistency in model construction and high comparability of the computational results.

In contrast, the calculated work of adhesion for the Fe2Al5(0

0)/Fe(110) interface is 1.119 J/m2, with an interfacial distance of approximately 1.989 Å. Although this interface structure converged upon structural optimization, the result deviates from previous findings reported in the literature. This discrepancy may arise from differences in the construction of the Fe2Al5(0

0) surface model compared to that in the reference, and more significantly, from the relatively large initial separation between the two surface slabs, which likely led to a larger optimized interfacial distance. The latter factor generally has a more pronounced impact.

Interfacial energy (

) is a key parameter characterizing the thermodynamic stability of material interfaces. It quantifies the excess energy associated with atomic rearrangements or chemical bond reconstructions in the interfacial region. The interfacial energy is typically defined as the difference between the total energy of the interface system and the sum of the energies of the two isolated surfaces and the chemical potentials of the constituent elements, normalized by the interfacial area [15]. The corresponding expression is generally given as:

Here,

represents the total energy of the interface system, while

and

denote the number of atoms and the chemical potential of component i, respectively. S is the interfacial area. The interfacial energy is commonly used to evaluate the thermodynamic stability of an interface: a lower value indicates a more stable interface. If the interfacial energy is negative, the interface is thermodynamically stable and may form spontaneously. The result is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The optimized structure information and calculated work of adhesion and interface energy.

Previous studies have demonstrated a relationship between the work of adhesion and interfacial energy [15], as described in Equation (7):

Equation (7) indicates that a lower interfacial energy leads to a higher work of adhesion. In this study, the FeAl(001)/Fe(001) interface exhibits the lowest interfacial energy and thus the highest work of adhesion, which is consistent with the trend predicted by the equation.

The interfacial fracture resistance describes the ability of an interface to resist crack initiation and propagation and is commonly characterized by the critical energy release rate

or by the work of adhesion

. Within the Griffith framework, the energetically preferred crack path is the one that requires the lowest fracture energy: if the energy needed to create new surfaces along the interface (proportional to

) is lower than that for bulk fracture, cracks tend to propagate along the interface; otherwise, they are more likely to penetrate through the bulk. In this sense,

provides an energetic measure of the resistance to interfacial separation and is governed by the interfacial bonding strength and the crystallographic characteristics of the adjoining phases.

For the FeAl(001)/Fe(001) and Fe3Al(001)/Fe(001) interfaces, the calculated works of adhesion are 5.25 J m−2 and 5.19 J m−2, respectively, indicating strong and essentially comparable interfacial bonding and structural stability. The slightly higher

of the FeAl/Fe interface may be related to the larger fraction of directional Fe–Al bonds in B2-structured FeAl, whereas DO3-structured Fe3Al contains a relatively higher proportion of Fe–Fe bonds with weaker directionality due to reduced orbital overlap. In both cases, the large

values imply that a substantial amount of energy is required to separate the interface, suggesting good resistance to interfacial crack initiation and growth. By contrast, the Fe2Al5(0

0)/Fe(110) interface exhibits a much lower work of adhesion of only 1.119 J m−2, which is markedly smaller than the values obtained for the FeAl/Fe and Fe3Al/Fe interfaces. This indicates a more fracture-prone and mechanically fragile interface, where crack propagation along the interface is energetically easier. The weak interfacial bonding can be attributed to the complex, low-symmetry crystal structure of Fe2Al5 and the relatively large interfacial separation, which together reduce the effectiveness and density of bonds across the interface.

Overall, considering both interfacial bonding strength and crystal-structure effects, the FeAl(001)/Fe(001) interface, with its slightly higher but generally large work of adhesion, offers the best interfacial fracture resistance and is well suited for the design of high-strength, high-stability interfacial materials. The Fe3Al(001)/Fe(001) interface, with similarly robust

and favorable overall performance, is appropriate for applications with moderate-to-high strength requirements. In contrast, the Fe2Al5(0

0)/Fe(110) interface, owing to its much lower

, is more prone to interfacial fracture and would benefit from further structural optimization to enhance its interfacial bonding strength and stability under high-stress conditions.

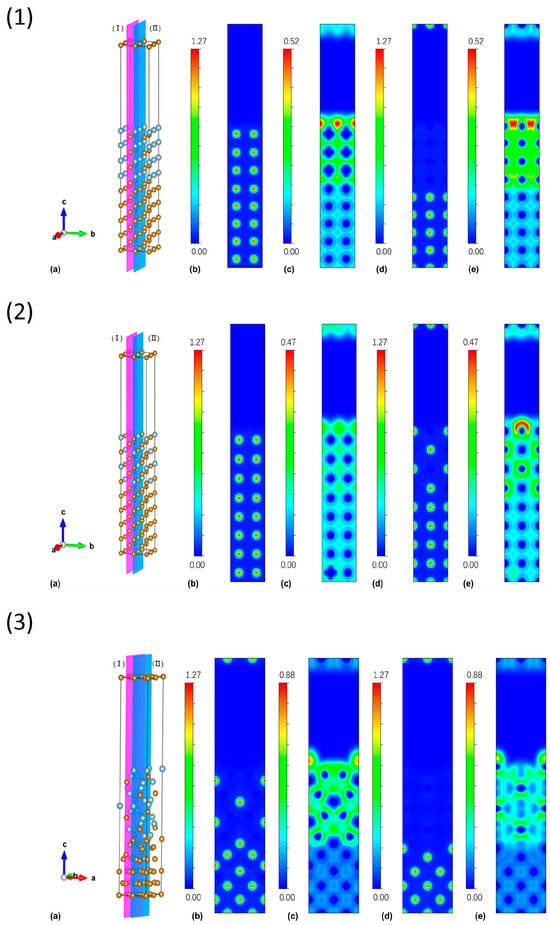

3.3. Fundamental Mechanism of Interfacial Adhesion

Across the three Fe–Al/Fe interfaces, metallic Fe–Fe bonding is predominant, but the electronic characteristics vary systematically with composition and crystal structure. At the FeAl/Fe (B2) interface, the charge density and ELF maps indicate a largely continuous metallic character with only weak Al-centered localization. This compact interfacial separation correlates with the highest work of adhesion (5.25 J m−2), indicating strong interfacial cohesion. The Fe3Al/Fe (DO3) interface remains dominated by Fe–Fe metallic bonding; the interfacial states are mainly governed by delocalized Fe 3d orbitals with limited Fe–Al hybridization, consistent with a slightly lower adhesion energy of 5.19 J m−2. In contrast, the Al-rich Fe2Al5/Fe (Cmcm) interface exhibits pronounced Al-centered localization in the ELF maps and a clear partial ionic character, together with a larger interfacial spacing (~1.99 Å) and the lowest adhesion energy (1.12 J m−2).

As shown in Figure 3, Fe–Fe bonding regions are associated with low ELF values (blue–green colors), characteristic of highly delocalized metallic bonding, whereas regions around interfacial Al atoms display higher ELF values (yellow–red colors), reflecting enhanced electron localization and partial ionic/covalent character. These localized Al-centered regions are particularly prominent at the Fe2Al5/Fe interface, consistent with its weaker work of adhesion and more fragile interfacial behavior compared with the FeAl/Fe and Fe3Al/Fe interfaces. Overall, increasing Al content and decreasing symmetry enhance electronic localization and disrupt metallic continuity across the interface, leading to a monotonic reduction in interfacial cohesion (FeAl/Fe > Fe3Al/Fe ≫ Fe2Al5/Fe) and a corresponding hierarchy in thermodynamic robustness.

Figure 3.

(1) FeAl(001)/Fe(001)interface, (2) Fe3Al(001)/Fe(001) interface, (3) Fe2Al5(001)/Fe(001) interface model. For each model, (a) Optimized atomic structure of the investigated interface/surface, where yellow and blue spheres denote Fe and Al atoms, respectively. .For each structure, the electronic structures of cross-sections (I) and (II) were investigated, with their charge density distributions and local electronic function populations shown. (b,c) correspond to cross-section (I), and (d,e) to cross-section (II). Red regions correspond to the strongest electron-density localization or highest ELF values, followed by yellow and green. Blue colors indicate weak electron localization: dark blue denotes regions with the lowest electron density/ELF, while light blue (cyan) represents slightly higher values that are still much lower than the green–yellow–red regions.

4. Conclusions

In this work, the structural, mechanical, and interfacial properties of Fe and three representative Fe–Al intermetallic compounds—FeAl, Fe3Al, and Fe2Al5—were systematically investigated via first-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT). The optimized bulk structures exhibited excellent agreement with available theoretical and experimental data, validating the reliability of the computational framework.

Mechanical property analysis shows that Al incorporation strongly modifies the stiffness, anisotropy, and ductility of Fe-based alloys. Among the intermetallics, FeAl exhibits the highest stiffness and shear resistance, consistent with its B2-ordered structure and relatively directional Fe–Al bonding. By contrast, Fe2Al5 displays the lowest moduli and the most pronounced elastic anisotropy, which can be attributed to its low-symmetry Cmcm lattice and complex atomic configuration. With increasing Al content, the bulk modulus and Poisson’s ratio exhibit an overall decreasing trend, indicating reduced ductility and a more brittle character in the Al-rich phases, particularly Fe2Al5.

Surface energy calculations indicated that Fe2Al5 exhibits the lowest surface energies among all compounds examined, implying greater thermodynamic stability on specific crystallographic facets. The FeAl(001)/Fe(001) and Fe3Al(001)/Fe(001) interfaces exhibited strong interfacial bonding, with high adhesion energies of 5.25 J/m2 and 5.19 J/m2, respectively. By contrast, the Fe2Al5(0

0)/Fe(110) interface displayed a substantially lower adhesion energy of 1.12 J/m2, suggesting weak interfacial bonding and limited structural robustness.

Charge density and electron localization function (ELF) analyses further clarify the bonding characteristics at the interfaces (Figure 3). For the FeAl/Fe and Fe3Al/Fe interfaces, the charge density is mainly concentrated around Fe nuclei and extends across the interface, while the ELF maps are dominated by blue–green regions, indicating that Fe–Fe and Fe–Al bonding is largely metallic and highly delocalized. This delocalized metallic bonding supports strong interfacial cohesion and is consistent with the relatively high works of adhesion obtained for these systems. In contrast, the Fe2Al5/Fe interface shows more pronounced Al-centered electron localization (yellow–red regions in the ELF maps) and a more heterogeneous bonding environment. This enhanced localization disrupts the continuity of metallic bonding across the interface and correlates with both the relatively low work of adhesion and the low surface energies of Fe2Al5 facets in Table 4. In other words, stronger electronic localization at Fe2Al5 surfaces and interfaces facilitates structural relaxation and bond rearrangement upon cleavage, which helps to reduce the excess energy and weakens interfacial cohesion.

In summary, the FeAl/Fe interface offers superior mechanical strength and fracture toughness, rendering it highly suitable for applications requiring robust interfacial integrity. The Fe3Al/Fe interface exhibits balanced performance and structural compatibility, making it appropriate for moderate-stress environments. In contrast, the Fe2Al5/Fe interface, due to its low adhesion strength and high anisotropy, may necessitate further structural optimization to enhance interfacial stability and reliability under mechanical loading.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.N., Q.C., P.W., J.W. and H.F.; Methodology, S.X.; Validation, Y.N.; Formal analysis, P.W. and S.X.; Investigation, Y.N., Q.C., P.W. and J.J.; Resources, J.J. and J.W.; Data curation, Q.C.; Writing – original draft, Y.N. and S.Z.; Writing – review & editing, Y.N., Q.C., C.L., H.F. and S.Z.; Visualization, Q.C., P.W., J.W., H.F., S.X. and S.Z.; Supervision, Q.C. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the CNPC Science and Technology Project (grant No. 2ZZ11-03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable..

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Xiao, S.; Meng, X.; Shi, K.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Lian, W.; Zhou, C.; Lyu, Y.; Chu, P.K. Hydrogen Permeation Barriers and Preparation Techniques: A Review. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2022, 40, 060803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, R. Hydrogen in Iron Aluminides. J. Alloys Compd. 2002, 330–332, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, U.; Parvathavarthini, N.; Dayal, R.K. Effect of Composition on Hydrogen Permeation in Fe–Al Alloys. Intermetallics 2007, 15, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemanič, V. Hydrogen Permeation Barriers: Basic Requirements, Materials Selection, Deposition Methods, and Quality Evaluation. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2019, 19, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Tang, T.; Lai, X. Preparation Technique and Alloying Effect of Aluminide Coatings as Tritium Permeation Barriers: A Review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 3697–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanzade, M.; Barnoush, A.; Motz, C. A Review on the Properties of Iron Aluminide Intermetallics. Crystals 2016, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Yang, F.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X. Effect of Steel Substrates on the Formation and Deuterium Permeation Resistance of Aluminide Coatings. Coatings 2019, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupka, M.; Stępień, K. Hydrogen Permeation in Fe–40 at.% Al Alloy at Different Temperatures. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 699–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xie, H.; Luo, L.-M.; Zan, X.; Liu, D.-G.; Wu, Y.-C. Preparation and properties of FeAl/Al2O3 composite tritium permeation barrier coating on surface of 316L stainless steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 383, 125282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Guo, B.; Mao, H.; Misra, R.D.K.; Xu, H. First-principles calculation of interfacial stability, energy, and elemental diffusional stability of Fe(111)/Al2O3(0001) interface. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 125313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewmon, P.G. Diffusion in Solids; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Palm, M. Iron aluminides. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2019, 49, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.-Y.; Wu, Q.-Y.; Sun, Y.-K. Hydrogen permeation behavior in a Fe3Al-based alloy at high temperature. J. Alloys Compd. 2005, 389, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methfessel, M.; Paxton, A. T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 51, 4929–4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-J.; Zhang, C.; Wei, S.-Z.; Yu, H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, G.-W.; Zhou, Y.-C.; Xiong, M.; Chen, C.; Wang, X.-D.; et al. Effects of active elements (Si, Cu, Zn, Mg) on the interfacial properties of Fe/Fe2Al5: A first-principles study. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient Iterative Schemes for ab initio Total-Energy Calculations Using a Plane-Wave Basis Set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector Augmented-Wave Method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. The Elastic Behaviour of a Crystalline Aggregate. Proc. Phys. Soc. A 1952, 65, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kube, C.M. Elastic Anisotropy of Crystals. AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 095209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Miller, N.E.; Marzari, N. Surface Energies, Work Functions, and Surface Relaxations of Low-Index Metallic Surfaces from First Principles. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 235407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Dai, J. Review of Highly Mismatched III–V Heteroepitaxy Growth on Si Substrates. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).