Study on the Degradation, Wear Resistance and Osteogenic Properties of Zinc–Copper Alloys Modified with Zinc Phosphate Coating

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Coating Fabrication

2.2. Microstructural Characterization

2.3. Electrochemical Test

2.4. Immersion Test

2.5. Slow Strain Rate Tensile Test (SSRT)

2.6. Friction and Wear Test

2.7. In Vivo Tests

2.7.1. Surgical Procedure

2.7.2. Micro-Computed Tomography (Micro-CT) Analysis

2.7.3. Histological Evaluation

2.7.4. In Vivo Biocompatibility Evaluation

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

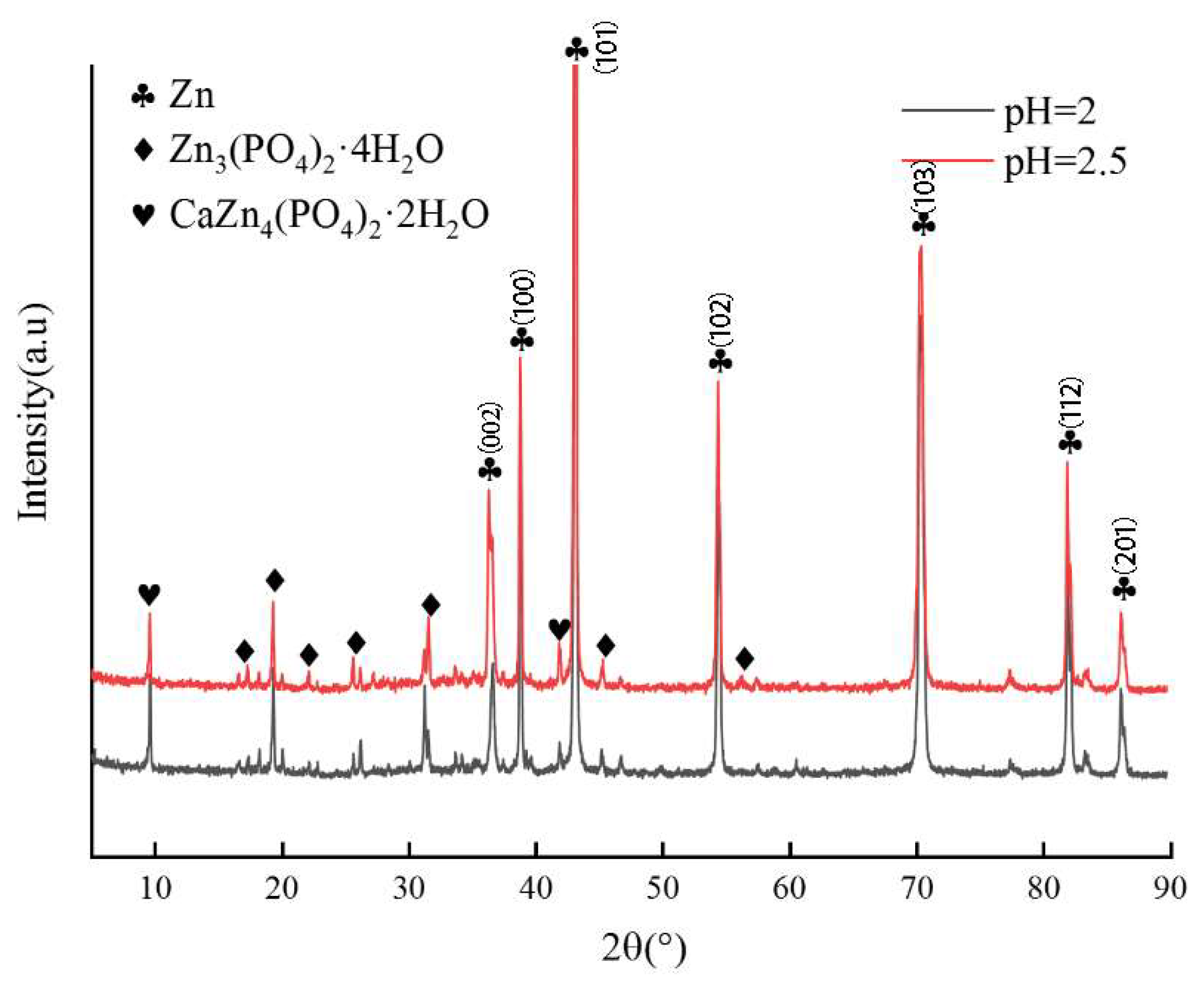

3.1. Microstructural Analysis

3.2. Electrochemical Corrosion

3.3. Immersion Test Analysis

3.4. Slow Strain Rate Tensile Test Analysis

3.5. Friction and Wear Test Analysis

3.6. Micro-CT Results

3.7. Histological Analysis

3.8. In Vivo Biocompatibility Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of the ZnP Coating on the Degradation Resistance and Stress Corrosion of Zn-1Cu Alloy

4.2. Effects of the ZnP Coating on the Osteogenic Properties of Zn-1Cu Alloy

5. Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ho-Shui-Ling, A.; Bolander, J.; Rustom, L.E.; Johnson, A.W.; Luyten, F.P.; Picart, C. Bone Regeneration Strategies: Engineered Scaffolds, Bioactive Molecules and Stem Cells Current Stage and Future Perspectives. Biomaterials 2018, 180, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hak, D.J.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Bishop, J.A.; Marsh, J.L.; Tilp, S.; Schnettler, R.; Simpson, H.; Alt, V. Delayed Union and Nonunions: Epidemiology, Clinical Issues, and Financial Aspects. Injury 2014, 45, S3–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kar, A.K.; Kaja, A.; Lim, E.J.; Choi, W.; Son, W.S.; Oh, J.-K.; Sakong, S.; Cho, J.-W. More Weighted Cancellous Bone Can Be Harvested from the Proximal Tibia with Less Donor Site Pain than Anterior Iliac Crest Corticocancellous Bone Harvesting: Retrospective Review. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, R.A.; Rozental, T.D. Bone Graft Substitutes. Hand Clin. 2012, 28, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Stok, J.; Van Lieshout, E.M.M.; El-Massoudi, Y.; Van Kralingen, G.H.; Patka, P. Bone Substitutes in the Netherlands—A Systematic Literature Review. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnis, S.; Neri, T.; Klasan, A.; Coolican, M. The Outcome of Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Bone Substitute in a Medial Opening Wedge High Tibial Osteotomy. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2020, 31, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka-Kobayashi, M.; Katagiri, H.; Lang, N.P.; Imber, J.-C.; Schaller, B.; Saulacic, N. Addition of Synthetic Biomaterials to Deproteinized Bovine Bone Mineral (DBBM) for Bone Augmentation-a Preclinical In Vivo Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jia, B.; Yang, H.; Han, Y.; Wu, Q.; Dai, K.; Zheng, Y. Biodegradable ZnLiCa Ternary Alloys for Critical-Sized Bone Defect Regeneration at Load-Bearing Sites: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 3999–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S. Clinical, Immunological, Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Roles of Zinc. Exp. Gerontol. 2008, 43, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Bao, G.; Jia, B.; Wang, M.; Wen, P.; Kan, T.; Zhang, S.; Liu, A.; Tang, H.; Yang, H.; et al. An Adaptive Biodegradable Zinc Alloy with Bidirectional Regulation of Bone Homeostasis for Treating Fractures and Aged Bone Defects. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 38, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Yang, H.; Jia, B.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Dai, K. Biodegradable Zn-Cu Alloys Show Antibacterial Activity against MRSA Bone Infection by Inhibiting Pathogen Adhesion and Biofilm Formation. Acta Biomater. 2020, 117, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, A.; Fan, J.; Wang, M.; Dai, J.; Jin, X.; Deng, H.; Wang, X.; Liang, Y.; Li, H.; et al. A Drug-Loaded Composite Coating to Improve Osteogenic and Antibacterial Properties of Zn-1Mg Porous Scaffolds as Biodegradable Bone Implants. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 27, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Miao, B.; Xiong, Y.; Guan, Y.; Lu, Y.; Jia, Z.; Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; Guan, C.; He, R.; et al. 3D Printed Porous Magnesium Metal Scaffolds with Bioactive Coating for Bone Defect Repair: Enhancing Angiogenesis and Osteogenesis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Zuo, K.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, M.; Li, Y.; Tian, S.; Lu, Y.; Xiao, G. Effect of Substrates Performance on the Microstructure and Properties of Phosphate Chemical Conversion Coatings on Metal Surfaces. Molecules 2022, 27, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-K.; Yu, X.; Cohen, D.M.; Wozniak, M.A.; Yang, M.T.; Gao, L.; Eyckmans, J.; Chen, C.S. Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2-Induced Signaling and Osteogenesis Is Regulated by Cell Shape, RhoA/ROCK, and Cytoskeletal Tension. Stem Cells Dev. 2012, 21, 1176–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.-L.; Yen, C.-E.; Lin, Y.-S.; Yeh, M.-L. Evaluation of Biodegradability and Biocompatibility of Pure Zinc Coated with Zinc Phosphate for Cardiovascular Stent Applications. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2023, 43, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilnejad, A.; Yarmand, B. Improving Biocompatibility and Corrosion Behavior of Biodegradable Zinc Implant Using a Calcium Zinc Phosphate Layer Sealed by Hydroxyapatite/Polylactic Acid. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 516, 132760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Feng, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y. Recent Advances and Perspectives for Zn-Based Batteries: Zn Anode and Electrolyte. Nano Res. Energy 2023, 2, e9120039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Yang, J.; Xu, B.; Chen, J.; Zhou, C. Effect of Heat Treatment on Chemical Plating of Ni-Cr-P on 65Mn Alloy Steel. Int. J. Inf. Retr. Res. 2024, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Qian, J.; Qin, H.; Hou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, Z.; Yu, F.; Chen, Y.; Wan, G.; Zeng, H. Osteogenerative and Corrosion-Decelerating Teriparatide-Mediated Strontium–Zinc Phosphate Hybrid Coating on Biodegradable Zinc–Copper Alloy for Orthopaedic Applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 109010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, S.; Tan, L.; Etim, I.P.; Yang, K. Comparative Study on Effects of Different Coatings on Biodegradable and Wear Properties of Mg-2Zn-1Gd-0.5Zr Alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 352, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wang, K.; Gao, J.; Yang, Y.; Qin, Y.-X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, D. Enhanced Cytocompatibility and Antibacterial Property of Zinc Phosphate Coating on Biodegradable Zinc Materials. Acta Biomater. 2019, 98, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzer, N.; Atrens, A.; Song, G.; Ghali, E.; Dietzel, W.; Kainer, K.U.; Hort, N.; Blawert, C. A Critical Review of the Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) of Magnesium Alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2005, 7, 659–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-N.; Zhu, S.-M.; Nie, J.-F.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, Z. Investigating the Stress Corrosion Cracking of a Biodegradable Zn-0.8 wt%Li Alloy in Simulated Body Fluid. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 1468–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biemond, J.E.; Eufrásio, T.S.; Hannink, G.; Verdonschot, N.; Buma, P. Assessment of Bone Ingrowth Potential of Biomimetic Hydroxyapatite and Brushite Coated Porous E-Beam Structures. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2011, 22, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, K.; Li, A.; Si, T.; Lei, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.; Xiao, G.; Lu, Y.; Li, N. Structural Optimization of Sr/Zn-Phosphate Conversion Coatings Triggered by Ions Preloading on Micro/Nanostructured Titanium Surfaces for Bacterial Infection Control and Enhanced Osteogenesis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.-W.; Du, C.-M.; Zuo, K.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-X.; Xu, X.-Q.; Li, Y.-B.; Tian, S.; Yang, H.-R.; Lu, Y.-P.; Cheng, L.; et al. Calcium-Zinc Phosphate Chemical Conversion Coating Facilitates the Osteointegration of Biodegradable Zinc Alloy Implants by Orchestrating Macrophage Phenotype. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2202537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Qiu, B.; Ze, Y.; Li, P.; Du, Y.; Gong, P.; Lin, J.; Yao, Y. Copper-Containing Titanium Alloys Promote Angiogenesis in Irradiated Bone through Releasing Copper Ions and Regulating Immune Microenvironment. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 139, 213010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, H.; Han, C.; Yan, Z.; Lu, Y.; Ren, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Xue, L. The Effect of Copper Content in Ti-Cu Alloy with Bone Regeneration Ability on the Phenotypic Transformation of Macrophages. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 252, 114641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Escobar, D.; Pajares-Chamorro, N.; Chatzistavrou, X.; Hankenson, K.D.; Hammer, N.D.; Boehlert, C.J. Tailored Coatings for Enhanced Performance of Zinc-Magnesium Alloys in Absorbable Implants. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 338–354. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.; Qin, H.; Zeng, P.; Hou, J.; Mo, X.; Shen, G.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Wan, G. Metal-Organic Zn-Zoledronic Acid and 1-Hydroxyethylidene-1,1-Diphosphonic Acid Nanostick-Mediated Zinc Phosphate Hybrid Coating on Biodegradable Zn for Osteoporotic Fracture Healing Implants. Acta Biomater. 2023, 166, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Joshi, A.; Agrawal, A.; Nain, A.; Bagde, A.; Patel, A.; Syed, Z.Q.; Asthana, S.; Chatterjee, K. NIR-Responsive Deployable and Self-Fitting 4D-Printed Bone Tissue Scaffold. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 49135–49147. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, F.; Dai, T.; Zhou, J.G.; Liu, J.; Song, K.; Tian, L.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y. In Vivo Biocompatibility and Degradability of a Zn–Mg–Fe Alloy Osteosynthesis System. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 7, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Cui, S.; Fu, R.K.Y.; Sheng, L.; Wen, M.; Xu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Chu, P.K.; Wu, Z. Optimization of the in Vitro Biodegradability, Cytocompatibility, and Wear Resistance of the AZ31B Alloy by Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings Doped with Zinc Phosphate. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 179, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Gao, A.; Liao, Q.; Li, Y.; Ullah, I.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, X.; Tong, L.; Li, X.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Balancing the Anti-bacterial and Pro-osteogenic Properties of Ti-based Implants by Partial Conversion of ZnO Nanorods into Hybrid Zinc Phosphate Nanostructures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2311812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheonea, R.; Crasmareanu, E.C.; Plesu, N.; Sauca, S.; Simulescu, V.; Ilia, G. New Hybrid Materials Synthesized with Different Dyes by Sol-Gel Method. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 2017, 4537039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Joshi, A.; Dasgupta, D.; Ghosh, A.; Asthana, S.; Chatterjee, K. 4D Printed Biocompatible Magnetic Nanocomposites toward Deployable Constructs. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 3345–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirasadi, K.; Yousefi, M.A.; Jin, L.; Rahmatabadi, D.; Baniassadi, M.; Liao, W.-H.; Bodaghi, M.; Baghani, M. 4D Printing of Magnetically Responsive Shape Memory Polymers: Toward Sustainable Solutions in Soft Robotics, Wearables, and Biomedical Devices. Adv. Sci. 2025, e13091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Areas | Chemical Composition (wt.%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn | Cu | P | O | |

| A | 23.08 | 0.35 | 13.76 | 62.81 |

| B | 22.39 | 0.37 | 15.02 | 62.22 |

| Ecorr (V) | icorr (μA/cm2) | CR (μm/Year) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH = 2 | −0.96 ± 0.026 | 0.26 ± 0.021 | 0.016 ± 0.025 |

| pH = 2.5 | −0.91 ± 0.024 | 0.15 ± 0.011 | 0.010 ± 0.009 |

| Rolled Zn-1Cu | −0.98 ± 0.036 | 0.72 ± 0.042 | 10.64 ± 0.017 |

| Alloys | UTS (MPa) | YS (MPa) | EL (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH = 2 | 100.08 ± 1.41 | 94.59 ± 1.22 | 14.89 ± 0.42 |

| pH = 2.5 | 117.03 ± 0.78 | 100.23 ± 0.49 | 20.61 ± 0.22 |

| Rolled Zn-1Cu | 82.83 ± 1.58 | 54.06 ± 1.27 | 10.89 ± 0.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, P.; He, J.; Han, S.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Hao, G.; Chen, J.; Yu, B. Study on the Degradation, Wear Resistance and Osteogenic Properties of Zinc–Copper Alloys Modified with Zinc Phosphate Coating. Coatings 2025, 15, 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121447

Dong P, He J, Han S, Liu Y, Cheng H, Hao G, Chen J, Yu B. Study on the Degradation, Wear Resistance and Osteogenic Properties of Zinc–Copper Alloys Modified with Zinc Phosphate Coating. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121447

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Pingyi, Jianing He, Shengkun Han, Yuandong Liu, Honghui Cheng, Guangliang Hao, Junxiu Chen, and Bo Yu. 2025. "Study on the Degradation, Wear Resistance and Osteogenic Properties of Zinc–Copper Alloys Modified with Zinc Phosphate Coating" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121447

APA StyleDong, P., He, J., Han, S., Liu, Y., Cheng, H., Hao, G., Chen, J., & Yu, B. (2025). Study on the Degradation, Wear Resistance and Osteogenic Properties of Zinc–Copper Alloys Modified with Zinc Phosphate Coating. Coatings, 15(12), 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121447