1. Introduction

The analysis of unintentional electromagnetic emissions has become a valuable tool for understanding the internal behavior of embedded systems.

When a digital circuit or microcontroller performs logical operations, transitions in internal signal lines generate small variations in current flow that radiate as measurable EM fields. These emissions, although unintentional, contain rich information about the instantaneous activity of the device. In the case of cryptographic hardware, such emissions may reflect the specific structure and timing of encryption routines, revealing when particular algorithms are active.

This phenomenon forms the basis of side channel analysis—a research domain focused on characterizing physical observables such as power consumption, timing, and electromagnetic radiation to study device behavior. While SCA has traditionally been associated with security testing and vulnerability assessment, its methodologies can also be used for diagnostics and behavioral monitoring, allowing one to infer what type of operation is occurring inside a device without invasive probing or code instrumentation.In this context, the analysis of EM traces is not used to extract secret information but rather to automatically detect when and which cryptographic processes are being executed.

Conventional SCA and EM signal analysis methods rely on manual inspection or statistical preprocessing of traces. Techniques such as differential or correlation-based analysis require prior knowledge about the timing of cryptographic activity, precise synchronization, and carefully filtered signals [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, in many practical scenarios, especially during continuous device operation or long-term monitoring, the timing of encryption routines is unknown. The measured EM waveform may consist of long idle periods interspersed with short bursts of cryptographic computation, often buried under noise or unrelated digital activity. As a result, manual segmentation or hardware-based triggering becomes impractical, and automated approaches are required.

Recent progress in machine learning has introduced several techniques capable of automatically extracting meaningful patterns from complex time-domain signals. Deep neural networks, particularly convolutional architectures, can learn hierarchical temporal features directly from raw electromagnetic measurements, without the need for handcrafted preprocessing or strict synchronization. Previous studies have demonstrated their effectiveness in side-channel analysis [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

In particular, Convolutional Neural Networks have shown excellent results in recognizing EM emission patterns related to specific encryption algorithms [

13,

14]. These models learn multi-scale temporal features that are characteristic of each algorithm, enabling reliable classification even under moderate noise or sampling variations.

At the same time, autoencoders have proven highly effective in unsupervised anomaly detection, where the goal is to identify segments of a signal that deviate from typical background behavior. An AE trained on non-cryptographic signal fragments can reconstruct them accurately, but will exhibit high reconstruction error when encountering unseen or “abnormal” activity such as encryption bursts.

This study proposes a two-stage deep learning framework that integrates both paradigms:

- (1)

An autoencoder-based anomaly detector for automatic segmentation of EM signals into potentially relevant time windows.

- (2)

A CNN-based classifier that labels those windows according to the active cryptographic algorithm.

The overall objective is not to perform key extraction or side channel attacks, but rather to provide an automated system for detecting and categorizing cryptographic activity in continuous EM measurements. This capability is valuable for noninvasive monitoring, verification of device behavior, and experimental research in hardware security.

In the proposed approach, the autoencoder serves as a learned model of the device’s baseline electromagnetic behavior—corresponding to idle or non-encrypting operation. By reconstructing the input signal, the AE produces a low reconstruction error for known background states and a high error for segments containing distinct patterns. The regions exceeding a defined error threshold are identified as potential cryptographic activity windows.

In the second stage, these windows are passed to a 1D CNN classifier, which analyzes them and assigns them to one of several known block cipher algorithms: AES, DES, 3DES, SM4, IDEA, Blowfish, or background noise.

This modular pipeline transforms a continuous EM recording into a labeled timeline of cryptographic events, effectively performing automated emission annotation. The combined system offers several key benefits:

It removes the need for manual segmentation or trigger synchronization, allowing analysis of long, continuous recordings;

It filters out irrelevant background activity, focusing computational resources on meaningful events;

It provides scalability for large datasets or real-time applications, as both models operate efficiently on sliding windows;

It enhances interpretability, since detected anomalies and their classifications can be directly visualized on the original EM waveform.

The method was implemented in Python 3.11.9 using the PyTorch 2.5.1 framework and experimentally validated using real measurement data collected from STM32L476RG (STMicroelectronics International N.V., Geneva, Switzerland) and Raspberry Pi RP2040 (Raspberry Pi Ltd., Cambridge, UK) microcontrollers. Both devices were programmed to perform multiple block cipher algorithms under controlled conditions.

By combining unsupervised anomaly detection with supervised classification, the system achieved an average accuracy of over 90% in correctly labeling cryptographic activity windows, demonstrating the potential of this hybrid deep learning approach for automatic analysis of electromagnetic emissions.

2. Methodology

The methodological foundation of this study is based on a sequential and integrated procedure designed to extract, annotate, and analyze electromagnetic emissions generated by microcontrollers during cryptographic operations. The workflow combines empirical data acquisition with machine learning techniques to obtain an automated system capable of detecting and classifying cryptographic activity within long, continuous electromagnetic recordings.

The first stage of the procedure involves the acquisition of uninterrupted electromagnetic emissions from microcontrollers operating under two conditions: during the execution of block cipher algorithms and during periods of idle operation. Continuous recording ensures that each captured waveform reflects natural transitions between active and inactive states, providing realistic data for later detection of cryptographic events. These raw measurements form the basis for constructing both the classification dataset and the anomaly detection mechanism.

In the second stage, the continuous traces are manually segmented into shorter fragments corresponding to specific activities. Each segment is assigned a label indicating either the type of block cipher executed (such as AES, DES, 3DES, SM4, IDEA, or Blowfish) or background noise representing idle periods. This manual annotation step establishes a reliable ground truth set that is subsequently used to train the supervised classifier. The segmentation process also ensures that model training is based on clearly isolated events, while the full-length continuous traces remain available for the evaluation of the anomaly detection system.

The third stage consists of designing and training a one-dimensional convolutional neural network classifier. This network is responsible for identifying the type of cryptographic algorithm present in each labeled fragment. A one-dimensional convolutional architecture was selected specifically because electromagnetic emissions form time-varying waveforms, in which the relevant information is expressed through local temporal patterns rather than spatial structures. Convolutional filters are therefore well-suited for extracting characteristic features that span several clock cycles and repeat in a structurally consistent manner across different executions of a given algorithm. In contrast to recurrent or transformer-based models, which introduce significantly higher computational costs and the risk of overfitting on relatively short windows, a 1D CNN provides an efficient, lightweight, and empirically validated solution widely used in side-channel analysis. The classifier, trained on manually annotated segments, learns to extract discriminative temporal features that characterize the electromagnetic signatures of different block cipher implementations. The resulting model serves as the decision component of the framework, providing semantic interpretations of anomalous signal regions detected in later stages.

In the fourth stage, an anomaly detection mechanism is developed in the form of a one-dimensional convolutional autoencoder. The autoencoder is trained exclusively on fragments representing idle or non-cryptographic activity, allowing it to learn a compact representation of typical background electromagnetic behavior. When applied to continuous, unsegmented traces, the autoencoder identifies deviations from this learned baseline by evaluating reconstruction errors. Elevated error values indicate anomalous windows that are likely to contain cryptographic operations. This enables automatic extraction of candidate regions from lengthy recordings without reliance on manual inspection or external trigger signals.

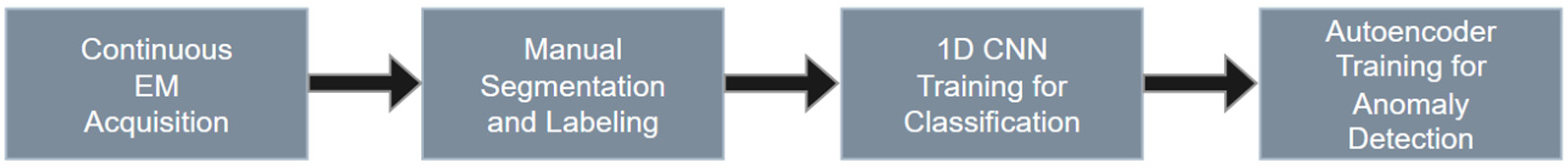

Together, these four stages form a coherent methodological framework in which continuous electromagnetic recordings are first collected and annotated, followed by the development of two complementary models: a classifier responsible for identifying cryptographic algorithms and an autoencoder dedicated to locating anomalous regions indicative of encryption activity. The integration of these components enables automated detection and classification of cryptographic processes directly from raw electromagnetic emissions. The overall structure of the proposed procedure is illustrated in the diagram (

Figure 1) presented below, while the subsequent section provides a detailed description of the measurement setup used for data acquisition.

3. Measurement Setup

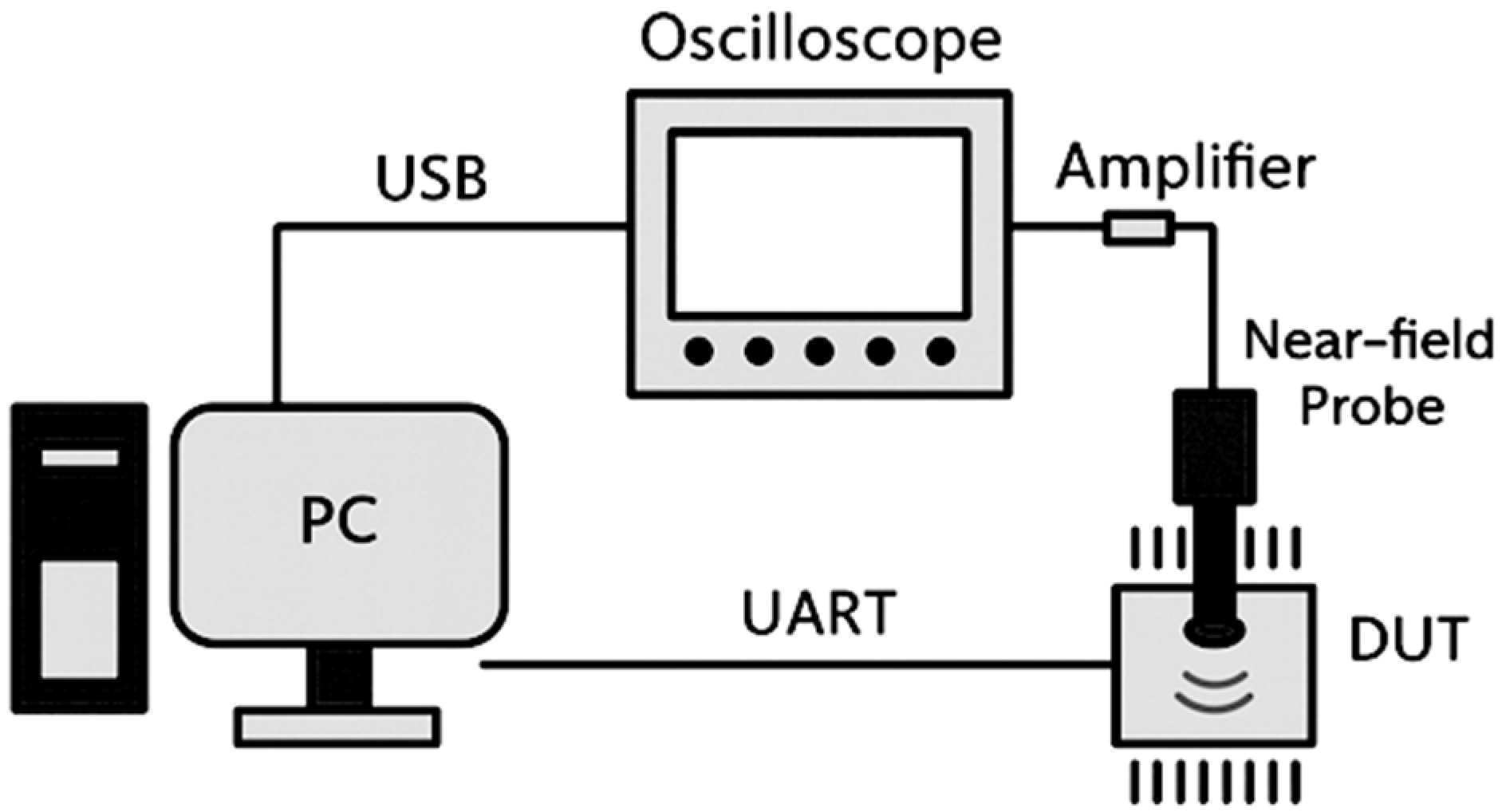

The experimental setup for electromagnetic emission acquisition was designed to capture weakly radiated signals generated by microcontrollers during cryptographic operations. The measurement system consisted of the following main components:

Near field electromagnetic probe—Riscure (Keysight Technologies Netherlands Riscure B.V., Delft, The Netherlands) EM probe (ø1.25mm)—used to sense local EM fields near the microcontroller’s surface.

Low noise amplifier (LNA)—the amplifier is an integrated part of the Riscure probe used. The manufacturer claims that the probe + LNA set can measure signals up to 6 GHz.

Oscilloscope—amplified analog signals were digitized using a Picoscope 3206D digital storage oscilloscope (Pico Technology Ltd., St Neots, Cambridgeshire, UK). The oscilloscope operated at a sampling rate of 500 MS/s, with 12-bit resolution. Data were transmitted to a host PC via a USB 3.0 interface.

Host control computer—a desktop PC managed the measurement procedure. It communicated with the DUT via UART, sent plaintext blocks for encryption, initiated the oscilloscope acquisition, and stored all resulting traces. A custom Python interface automated this process to ensure consistent timing and labeling.

Device Under Test (DUT)—two embedded platforms were examined:

STM32L476RG (ARM Cortex-M4, 80 MHz clock),

Raspberry Pi RP2040 (dual core ARM Cortex M0+, 133 MHz clock).

These devices represent different microcontroller classes (high performance and low power) and are widely used in cryptographic applications.

Each microcontroller was programmed to perform block cipher encryption routines using six algorithms: AES, DES, 3DES, SM4, IDEA, and Blowfish. An additional noise class was collected by running the device in an idle state or executing non-cryptographic loops. All encryption algorithms were implemented in ECB (Electronic Codebook) mode, ensuring deterministic timing and reproducibility across runs [

15,

16].

To ensure that each recorded waveform contained both the cryptographic operation and the surrounding idle regions, the microcontroller firmware used in the preliminary stages of data collection was instrumented with a dedicated trigger signal. The trigger line was asserted at the exact moment the encryption routine began and cleared immediately after the routine completed. This hardware marker allowed us to capture a sufficiently wide acquisition window that always included a period of idle activity preceding the encryption process, the encryption itself, and the idle region that followed. By aligning oscilloscope acquisition with the rising edge of the trigger, we ensured full and repeatable coverage of the entire operation cycle in all recorded traces. Each captured trace contained approximately 130,000–600,000 samples, covering the entire encryption sequence and surrounding idle regions.

Synchronization between the encryption command and EM capture was controlled by a PC via a USB/UART interface. The PC transmitted plaintext blocks to the DUT, triggered the encryption, and simultaneously initiated the oscilloscope acquisition. This setup provided deterministic execution timing while preserving the natural variability of the background electromagnetic noise. The overall measurement setup is shown schematically in

Figure 2.

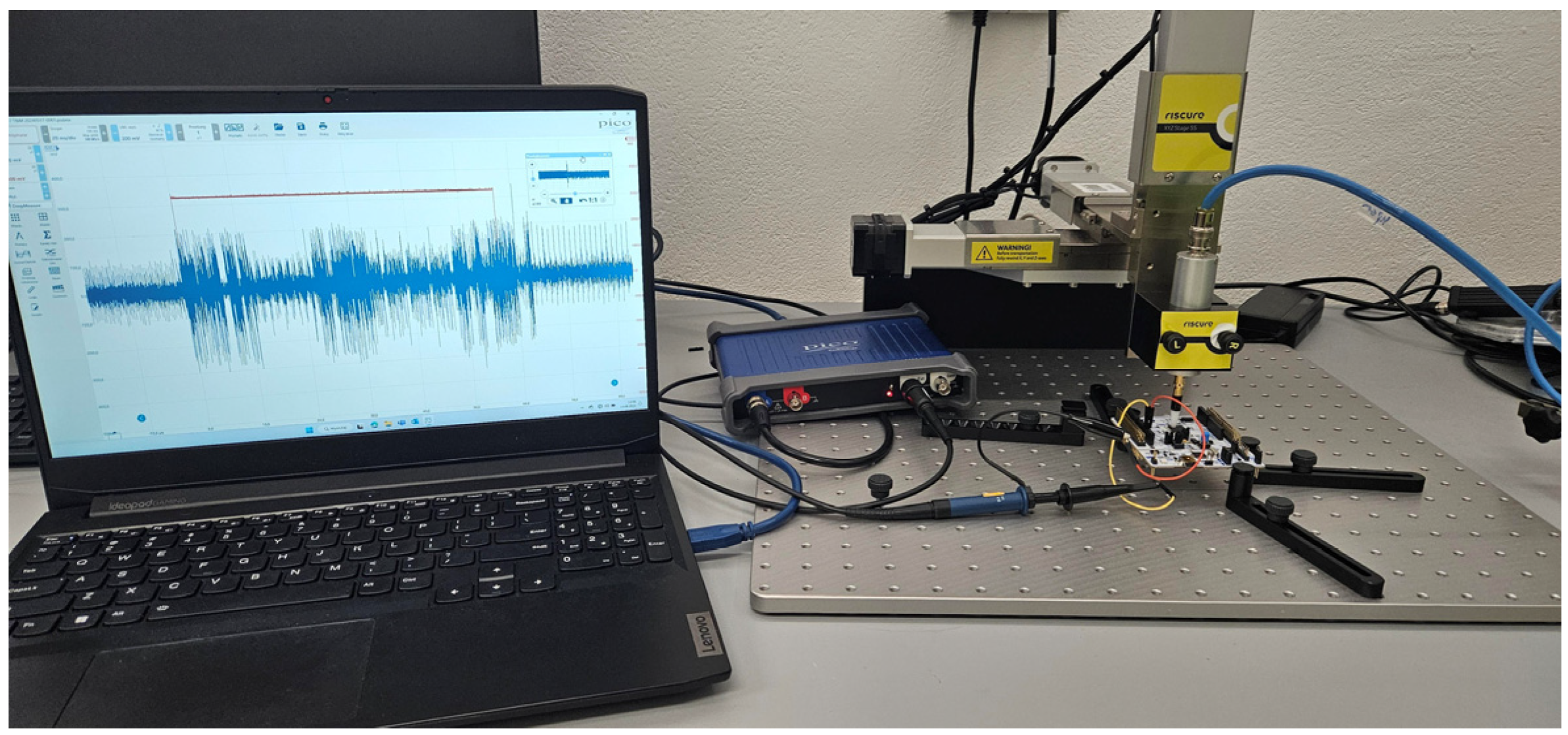

The measurement system (

Figure 3) thus provided a high-fidelity dataset of real radiated emissions under well-defined cryptographic workloads. These data served as the input for further machine learning analysis, including anomaly detection and classification [

17,

18,

19].

4. Dataset Preparation

The effectiveness of any data-driven learning approach relies heavily on the quality and representativeness of the training dataset. In this work, the dataset consisted of electromagnetic emission traces recorded from two microcontroller platforms executing various block cipher algorithms. Each trace represented the temporal evolution of the EM field intensity during a single encryption routine, measured as an analog voltage signal.

4.1. Data Structure and Organization

All recorded signals were stored in binary NumPy format to ensure efficient access and compatibility with Python-based machine learning frameworks. Each file contained two columns:

For each encryption algorithm and each hardware platform, approximately 600 traces were collected. The entire dataset contained over 3000 EM recordings, grouped according to the executed cryptographic routine:

AES;

DES;

3DES;

SM4;

Idea;

Blowfish;

Noise.

Each directory corresponded to one class label used later during CNN training. The noise category consisted of traces recorded while the microcontrollers were idle or executing non-cryptographic tasks. This baseline class was essential for training the autoencoder, which learned to model “normal” system behavior in the absence of encryption.

4.2. Signal Conditioning and Segmentation

During acquisition, EM traces were captured with a time window significantly wider than the actual encryption activity. This ensured that the recorded waveform included both the cryptographic operation itself and the surrounding idle regions. From these longer recordings, the relevant time intervals containing the encryption process were extracted to create a clean, well-annotated dataset suitable for deep learning. These cropped segments were then cataloged according to the algorithm type (AES, DES, 3DES, SM4, IDEA, Blowfish, or Noise) and stored as separate .npy files. This process provided the neural networks with consistent, high-quality examples of EM activity for each cryptographic routine.

After segmentation, all extracted fragments were standardized using the following preprocessing pipeline:

Resampling—to ensure a uniform input length across all samples, each signal was resampled to 128,000 points using Fast Fourier Transform.

Normalization—Each resampled trace was scaled to the range

using min–max normalization:

The purpose of standardization was twofold. Firstly, it removed the influence of absolute amplitude variations caused by differences in measurement conditions, such as probe positioning, gain settings, or slight changes in supply voltage.

Secondly, it allowed the neural networks to focus on the shape and temporal dynamics of the waveform rather than on absolute signal magnitudes.This significantly improved training stability—preventing the gradients from exploding or vanishing—and facilitated faster convergence of both the autoencoder and CNN during optimization.

Moreover, normalization unified the data distribution between traces from different hardware platforms, which enabled cross-device generalization and made the learned features more robust to environmental and instrumental variations.

4.3. Data Augmentation

Since EM emission patterns can vary due to small changes in probe position, clock jitter, and background interference, the dataset was expanded through data augmentation to improve model generalization. Randomized transformations were applied dynamically during training:

These augmentations effectively diversified the training set and encouraged the neural networks to learn invariant, algorithm-specific patterns rather than overfitting to device or session-specific artifacts.

4.4. Dataset Partitioning

After preprocessing, segmentation, and augmentation, the dataset was divided into three disjoint subsets:

Training set: 80%

Validation set: 15%

Testing set: 5%

The partitioning was performed by class to preserve the relative contribution of each algorithm across all subsets. This ensured consistent performance evaluation and minimized errors during model validation. The testing set was relatively small because it was not directly involved in model training.

The resulting dataset provided a comprehensive and well-balanced foundation for the subsequent stages of analysis—namely, autoencoder-based anomaly detection and CNN-based classification of detected cryptographic windows.

5. Autoencoder-Based Anomaly Detection

Unsupervised anomaly detection was employed as the first stage of the proposed framework, aiming to automatically locate time intervals within continuous electromagnetic signals that contain cryptographic activity. This task was accomplished using a one-dimensional convolutional autoencoder, which learned to reconstruct normal background signals.

Once trained exclusively on non-cryptographic (idle) traces, the autoencoder was able to recognize deviations from this learned pattern as anomalies, corresponding to active encryption events.

5.1. Theoretical Background

An autoencoder (AE) is a neural network designed to learn a compressed representation of the input data without requiring explicit labels.

In the context of this study, the autoencoder operated on a continuous electromagnetic (EM) signal divided into short, overlapping time windows.

Each window was independently passed through the network, which attempted to reconstruct it as accurately as possible based on patterns learned from normal, non-cryptographic activity.

During inference, the AE processed the entire test signal window by window, producing both the reconstructed version of each fragment and the corresponding reconstruction error—defined as the difference between the input and the network’s output.

Windows that resembled typical background noise were reconstructed with very low error, while those containing encryption-related activity exhibited significantly higher error due to their unfamiliar structure.

By computing the reconstruction error across all windows, a temporal error profile was generated, allowing the system to identify intervals where anomalies occurred.

This profile effectively transformed the raw EM signal into a one-dimensional “anomaly map” that marked the most probable regions of cryptographic activity.

An autoencoder consists of two main components:

where

is the number of samples in each signal window.

When an autoencoder is trained only on examples of normal system behavior (in this case, EM emissions during idle operation), the autoencoder learns to accurately reconstruct familiar patterns but fails to reproduce unseen or unusual ones.

Therefore, the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between input and reconstruction can serve as a measure of anomaly intensity:

where

is the length of the sliding window. A window size of 50,000 samples was used in this study.

If the reconstruction error exceeded a predefined threshold, the corresponding segment was marked as anomalous—indicating that the microcontroller was likely performing a cryptographic computation.

This approach is particularly suitable for EM-based side channel analysis for the following reasons:

Background noise and idle emissions are statistically stationary, while cryptographic routines produce distinctive transient patterns.

The model operates in an unsupervised manner—no manual labeling of cryptographic windows is required.

It can process continuous, streaming data, enabling future extensions to real-time monitoring.

5.2. Autoencoder Network Architecture

The implemented autoencoder followed a convolutional symmetric structure, optimized for one-dimensional time series signals.

Convolutional layers captured local dependencies between adjacent samples and allowed efficient learning of the characteristic temporal features of the background signal.

The architecture used in this work is summarized below (

Table 1):

The encoder progressively reduced the signal’s temporal resolution while increasing the number of feature channels, effectively learning a compressed latent representation of typical EM behavior. The decoder then performed a symmetric expansion to reconstruct the original waveform.

The encoder consisted of two convolution–pooling blocks that progressively reduced the temporal resolution while increasing feature dimensionality. This compressed the idle-state EM segments into a compact latent representation. The decoder mirrored this structure via transposed convolutions, reconstructing the input waveform. The kernel sizes (7 and 5) were empirically selected to capture local EM fluctuations at a granularity corresponding to several clock cycles. MaxPooling with stride 2 halved the temporal dimension, enabling multiscale representation learning. The final Tanh activation ensured that the reconstructed signals remained in the normalized range (−1, 1).

All convolutional and transposed convolutional layers used zero padding to maintain consistent signal alignment. The model was implemented in PyTorch.

5.3. Training Procedure

The autoencoder was trained on windows extracted exclusively from noise (non-encrypting) signals. The training process followed these parameters (

Table 2):

During training, the autoencoder learned to minimize the reconstruction error for background activity. After convergence, the model’s parameters were frozen, and the trained AE was used as a feature extractor and anomaly detector for subsequent EM traces. To avoid overfitting, the model was trained with data augmentation techniques described in

Section 4.3, ensuring exposure to slightly distorted but still “normal” background examples.

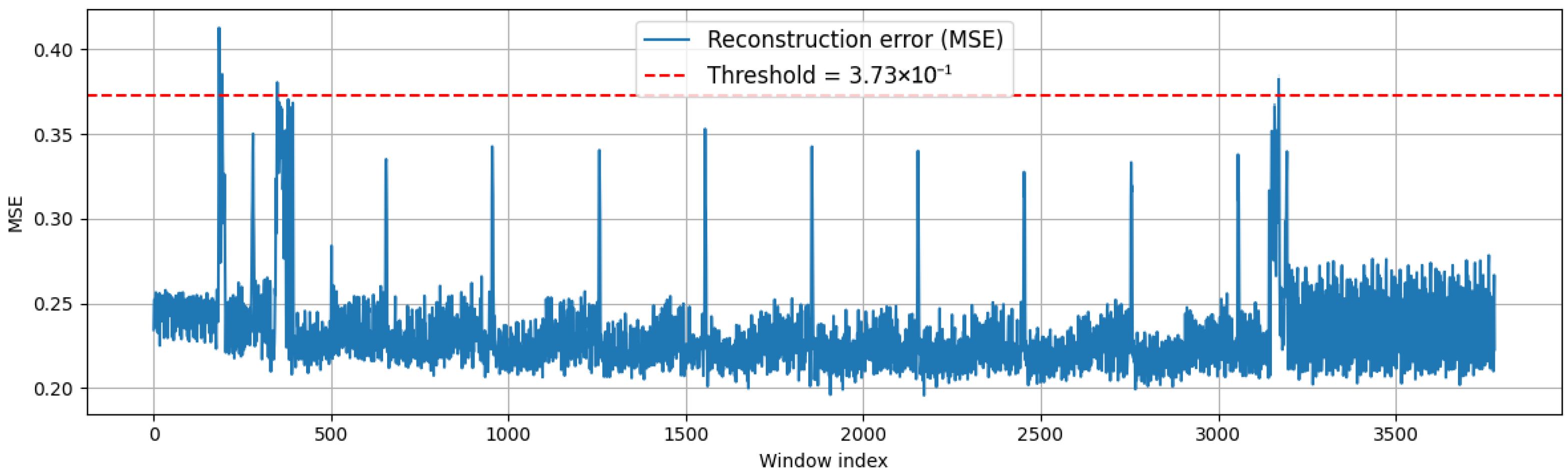

5.4. Anomaly Detection and Thresholding

After training, the autoencoder was applied to continuous EM traces, which could have contained both idle and encryption periods. The reconstruction error was computed for each overlapping window, forming an error profile along the entire signal.

To automatically distinguish normal and abnormal regions, an adaptive threshold was defined as follows:

where

and

denote the mean and standard deviation of the reconstruction error over the entire background dataset, and

is a sensitivity coefficient (empirically set to 4). Each signal window whose reconstruction error exceeded the threshold (

) was considered anomalous and associated with a local increase in electromagnetic activity. The coefficient

controls the tradeoff between false alarms and missed detections. In this context, false alarms refer to windows incorrectly marked as anomalous despite containing only normal background behavior. These events occur when natural fluctuations, probe jitter, or transient noise locally increase the reconstruction error but do not correspond to actual cryptographic activity. To select a value of

, the distribution of reconstruction errors for the background dataset was analyzed empirically. For idle EM segments, the reconstruction error showed near-Gaussian behavior, with light tails, allowing its statistical variability to be quantified by

. Values of the threshold below

produced an excessive number of false alarms, as normal fluctuations in the background noise frequently exceeded the threshold. Conversely, thresholds above

led to missed detections of cryptographic activity, particularly in traces whose encryption signatures did not significantly exceed the noise floor. Selecting

placed the threshold in the region where the probability of background fluctuations exceeding

was statistically bounded by the tail of the empirical distribution, while still allowing the detector to respond to structurally distinct patterns generated during encryption. The application of this threshold is illustrated in

Figure 4.

In contrast to conventional methods that merge adjacent anomalous windows into longer intervals, the implemented system adopted a center-based localization approach. For each group of consecutive anomalous windows, the algorithm determined the central point of the segment, calculated as follows:

Equation (9) computes the temporal center of an anomalous region detected by the autoencoder. The array indices contains the starting positions of all consecutive windows whose reconstruction error exceeds the anomaly threshold. The middle element of this array represents the central anomalous window. Since each window is aligned by its starting index, half of the window length is added to obtain the true midpoint in the original signal. This value defines the most likely center of the cryptographic activity and is used to extract a precise classification window for the CNN model.

This approach ensured that only the most relevant regions centered on the actual anomaly peaks were analyzed in detail, avoiding redundant or overlapping segments. The use of central point localization instead of contiguous merging provided several benefits:

Improved temporal precision, as the CNN operated on windows centered exactly at the points of maximum anomaly;

Reduced data redundancy, since overlapping anomalous areas were represented by a single, well-defined center;

Simplified pipeline integration, as each detected center corresponded to one candidate classification region.

This center-based strategy effectively bridged the anomaly detection and classification stages, transforming continuous EM signals into a sequence of candidate regions that were both compact and semantically meaningful.

5.5. Practical Application and Visualization

To illustrate the operation of the anomaly detection module,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the results of the autoencoder applied to a representative EM signal containing both idle and cryptographic activity. In

Figure 4, the reconstruction error (MSE) of the autoencoder is plotted for each sliding window along the signal. The red dashed line represents the detection threshold, determined as described in

Section 4.3. Windows with an average reconstruction error exceeding this threshold are classified as anomalies.

In

Figure 5, the corresponding raw EM signal is shown, with red dashed vertical lines marking the boundaries of windows identified as anomalous.

Each detected window is labeled with a red digit placed at its center, indicating the order of detection.

From the plots, it can be observed that regions of elevated reconstruction error (in

Figure 4) align with short bursts or distortions in the EM signal (in

Figure 5), indicating transitions from idle to active computing phases. By automatically identifying these regions, the system effectively isolates candidate segments for subsequent CNN-based classification without the need for manual synchronization or trigger signals.

Detected windows are processed individually by the CNN classifier to distinguish background noise from cryptographic activity and to identify the specific block cipher in use.

In practice, each window is fed as a separate input to the CNN.

6. CNN-Based Classification

After anomaly detection, each identified window of the electromagnetic signal is processed individually by a classifier based on a one-dimensional convolutional neural network. The goal of this stage is twofold:

In this way, the CNN serves as the decision layer of the proposed framework, transforming the automatically detected anomalies into semantically meaningful labels such as AES, DES, 3DES, SM4, IDEA, Blowfish, or Noise.

6.1. Theoretical Background

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are particularly effective for analyzing one-dimensional time series data, as they can automatically extract hierarchical features from raw signals without manual preprocessing [

20].

A 1D CNN applies convolutional filters along the time axis, capturing local correlations between adjacent samples and learning the characteristic temporal motifs of each class. Formally, a 1D convolutional layer computes the feature map

from the input

as follows:

where

are the convolutional kernels,

are bias terms,

denotes discrete convolution,

is the number of input channels, and

is a nonlinear activation function (e.g., ReLU). Pooling layers are subsequently applied to reduce dimensionality while preserving dominant features, leading to progressively more abstract representations of the input waveform. This property makes CNNs highly suitable for side channel analysis tasks, where subtle, repetitive signal structures correspond to distinct cryptographic operations.

6.2. CNN Network Architecture

The proposed CNN was optimized for windows produced by the autoencoder’s detection stage. Each window represents an isolated time fragment of the EM signal centered around a detected anomaly. The network architecture is summarized in the table below (

Table 3):

The Softmax output layer produces a normalized probability vector:

where

K = 7 corresponds to the number of classes (six encryption algorithms plus noise). The class with the highest probability

is selected as the model’s prediction.

6.3. Training Procedure

The CNN was trained using labeled windows derived from the preprocessed dataset described in

Section 3. Each training sample corresponded to one of the seven classes, balanced through data augmentation and class weighting to prevent bias toward more frequent algorithms. Training parameters are summarized below (

Table 4):

The cross-entropy loss function was defined as follows:

where

represents the true label and

is the predicted probability for class

.

6.4. Model Evaluation

The trained CNN was evaluated on the test subset of the dataset using standard metrics:

ACC—accuracy,

P—precision,

R—recall, and

F1-score, defined as follows:

where

TP—True Positives,

TN—True Negatives,

FP—False Positives,

FN—False Negatives. The model achieved an average classification accuracy exceeding 90% on unseen test data, demonstrating its ability to reliably distinguish different block ciphers from background activity.

6.5. CNN Classifier Summary

The CNN classifier forms the second stage of the proposed detection pipeline.

Operating on the anomaly-centered windows provided by the autoencoder, it assigns a semantic label to each detected segment. This architecture enables the system to autonomously analyze long EM traces, accurately identifying when encryption occurs and which algorithm is being executed—without manual segmentation, synchronization, or prior knowledge of the signal timing.

7. Results

7.1. Training Parameters

All configuration parameters used in the experimental evaluation are documented in the corresponding configuration tables.

Table 2 presents the configuration of the autoencoder employed for anomaly detection, detailing the model structure, learning parameters, and the method used to determine the reconstruction-error threshold.

Table 4 provides a complete specification of the convolutional neural network classifier, including the architecture, hyperparameters, and optimization settings. Together, these tables summarize all training and evaluation settings relevant to the results reported in this section, ensuring clarity and reproducibility of the presented findings.

7.2. Visualization of Classification Results

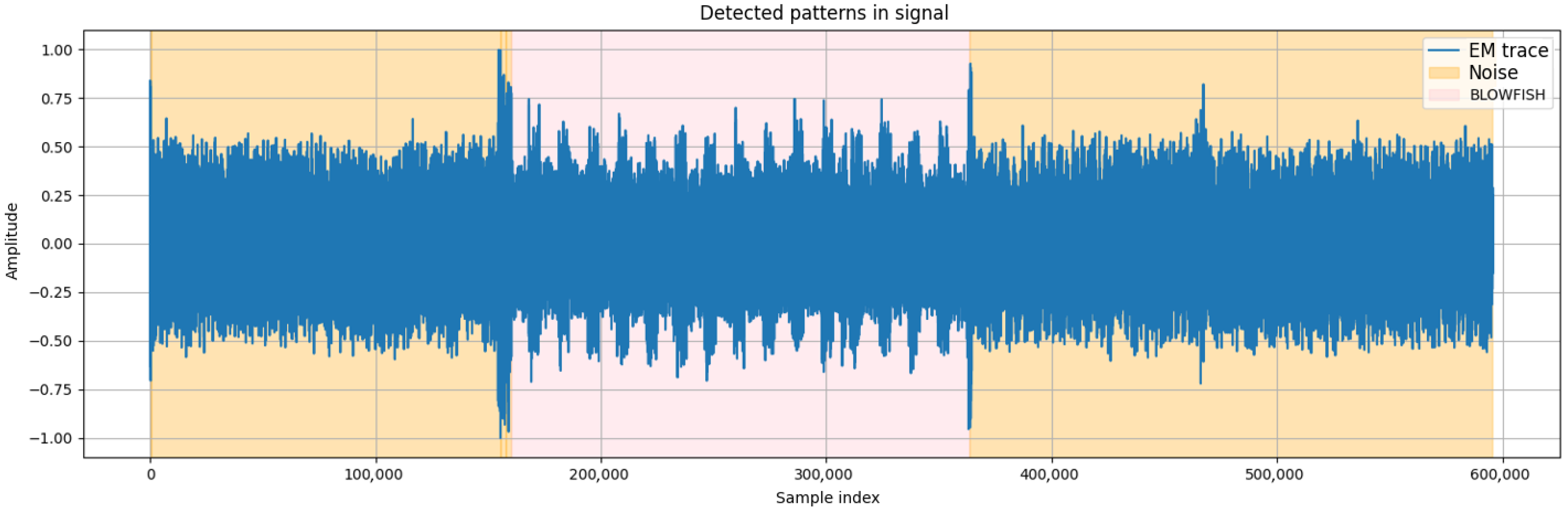

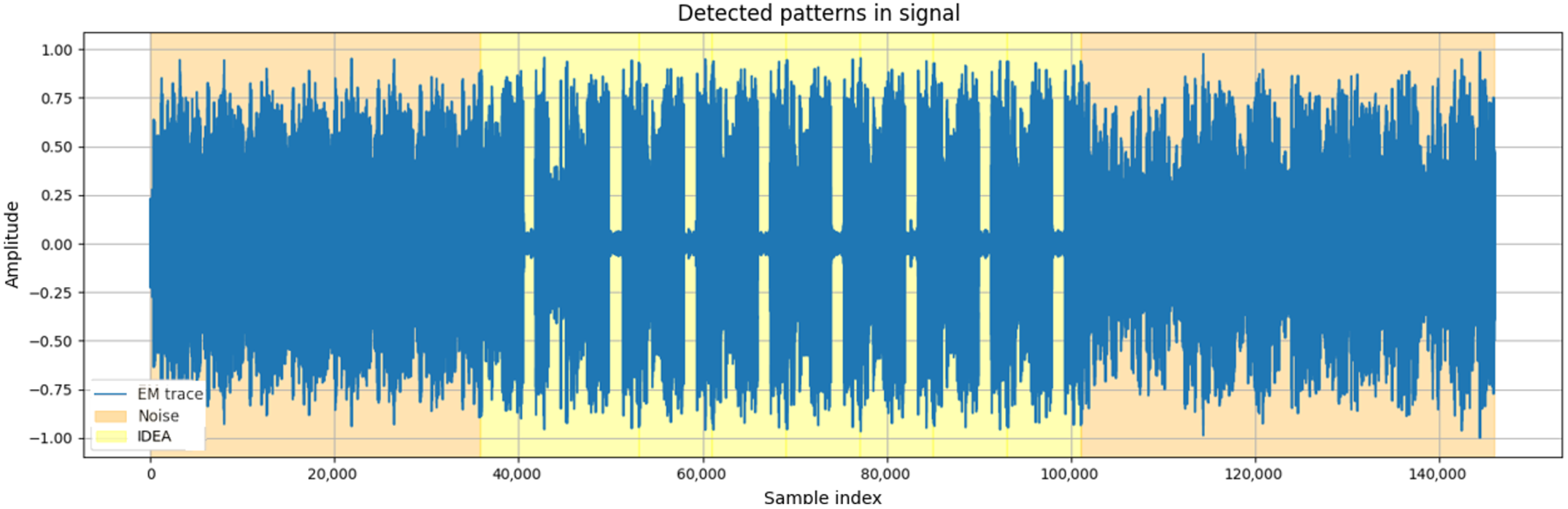

To provide an intuitive understanding of the system’s operation,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate representative examples of electromagnetic signal classification and anomaly detection results obtained from the trained models.

In

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, color-coded overlays correspond to regions detected and classified by the CNN as different cryptographic algorithms or background noise. Each segment originates from continuous EM measurements acquired during the execution of block cipher routines on a microcontroller. In

Figure 6, the model correctly identifies the Blowfish encryption phases interleaved with intervals of background noise. The transition boundaries between active and idle states are sharply delineated, demonstrating that the windowing mechanism guided by the autoencoder effectively isolates cryptographic activity. Similarly,

Figure 7 shows the classification of 3DES encryption, with the blue regions corresponding to detected 3DES activity. The model maintains high temporal precision, marking only the relevant fragments of the signal while ignoring non-informative background intervals.

Figure 8 clearly illustrates why simple energy threshold detection fails to reliably identify cryptographic operations in EM signals. During encryption, the signal energy does not significantly deviate from the background, making energy-based thresholds ineffective. Although the autoencoder is able to approximately delineate the window containing relevant activity, the boundaries are not perfect. This slightly imprecise window is still suitable for a CNN-based classifier, which can learn and tolerate such variations, but it is insufficient for a classical correlation-based detector, as the signal within the window may be shifted or misaligned relative to the template. Therefore, classical methods such as energy detection or correlation are unable to achieve robust detection in this scenario.

Comparable visualization results were also obtained for the other analyzed algorithms—3DES, SM4, and Blowfish. In each case, the CNN network correctly distinguished between different cipher implementations. These consistent visual results across multiple cryptographic procedures confirm the generalizability of the proposed detection and classification process.

7.3. Evaluation Metrics

The model was evaluated on the validation subset using the metrics defined in

Section 5.4: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score.

Table 5 summarizes the per-class results obtained on unseen data.

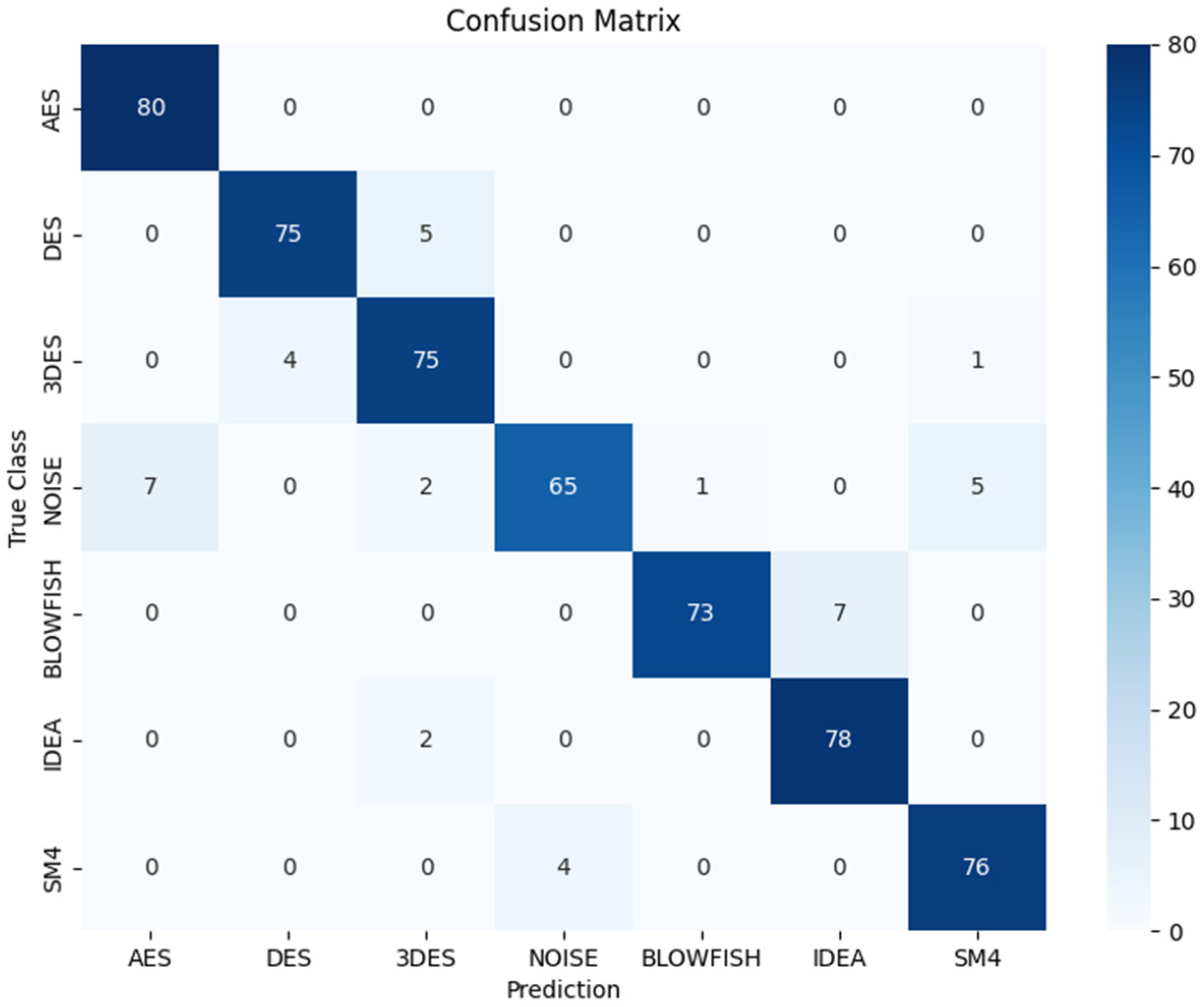

Additionally, a confusion matrix was created (using 100 examples for each class to show which classes are most often confused), which is shown in

Figure 9.

The highest recognition accuracy was achieved for the AES class, reaching 1.0. The rest algorithms were also identified reliably, though with slightly lower accuracy values. The 3DES class achieved an accuracy of 0.93, but its structure overlaps partially with DES due to similar structural and temporal characteristics. The Noise class showed the lowest recognition rate (0.81), indicating that distinguishing non-cryptographic background signals remains the most challenging task for the model. The lower performance of the Noise class is expected, as noise in EM measurements is inherently heterogeneous and may include a wide range of transient disturbances, background activity, and device-specific artifacts. In our dataset, the Noise class was also the largest and most diverse, containing fragments collected from both hardware platforms, which increases intra-class variability and makes it difficult for the model to learn a compact representation. On average, the overall classification accuracy reached 0.93, demonstrating solid generalization across all categories.

Although overall accuracy provides a convenient single-number summary of classifier performance, it does not fully reflect the structure of the errors observed in multi-class time-series classification tasks. The confusion matrix reveals that misclassifications are not uniformly distributed among the classes: some categories are more easily separable, while others contain partially overlapping temporal characteristics or exhibit greater intra-class variability. In such situations, relying solely on accuracy may obscure systematic tendencies of the model, such as increased false positive rates for specific classes or reduced sensitivity to low-energy or structurally subtle patterns. For this reason, class-wise precision, recall, and F1 score were additionally reported. These metrics offer a more nuanced assessment of performance: precision captures the propensity of the model to generate false detections, recall measures the ability to correctly identify true events, and the F1-score provides a balanced indicator that remains informative even under class imbalance or heterogeneous noise conditions. Together, these measures offer a more reliable characterization of the classifier’s behavior across all categories of electromagnetic emissions.

8. Discussion and Summary

The presented two-stage framework, integrating an autoencoder-based anomaly detector with a CNN-based classifier, represents a novel, data-driven approach to electromagnetic emission analysis for cryptographic systems. Unlike traditional side-channel analysis methods, which focus primarily on key extraction or statistical leakage evaluation, the proposed system aims at automated detection, localization, and recognition of cryptographic activity within continuous EM traces [

3,

21,

22].

Classical EM-based detection approaches, such as amplitude/energy thresholding or statistical preprocessing, are generally effective only when encryption activity produces clearly distinguishable amplitude peaks. In continuous EM recordings, however, cryptographic operations often appear with amplitudes comparable to background noise. As illustrated in

Figure 8, simple energy-based methods fail to detect such low-amplitude events. In contrast, the autoencoder captures subtle structural deviations in the waveform rather than relying solely on absolute signal magnitude. Furthermore, traditional methods typically require prior timing information or stable triggers, while the proposed framework operates autonomously without synchronization or manual segmentation.

8.1. Innovative Aspects and Practical Usefulness

The proposed approach introduces a fully autonomous detection framework that operates without manual synchronization, external triggers, or prior knowledge of when cryptographic operations occur. At its core, the autoencoder functions as an unsupervised observer, learning the normal electromagnetic behavior of the device and highlighting any deviations that may correspond to cryptographic processing. This design enables the identification of subtle computational activity even when the useful signal is almost indistinguishable from background noise.

From a practical perspective, the developed system can be applied in several areas related to embedded security and hardware analysis:

Security verification and auditing—The method can automatically confirm whether cryptographic routines on a tested device operate as expected. Continuous observation of emitted signals makes it possible to reveal unauthorized code modifications, hidden encryption modules, or hardware Trojans that alter the expected execution flow.

Device fingerprinting and implementation profiling—Distinct electromagnetic signatures often arise from different implementations of the same algorithm (e.g., software-based vs. hardware-based AES). The CNN classifier can therefore support identification of specific firmware versions, encryption libraries, or chip-level variants [

15,

16].

Anomaly monitoring in secure IoT environments—When deployed as a continuous monitoring tool, the combined autoencoder CNN architecture can detect abnormal cryptographic activity, such as unplanned data encryption, potential ransomware-like behavior, or covert communication attempts.

Support for side channel testing and certification—Instead of manually searching for encryption intervals in lengthy signal captures, engineers can use this method to automatically locate and label relevant segments, significantly reducing the time required for evaluation and certification.

8.2. Limitations

Although the proposed framework demonstrates strong performance, several limitations of the current study should be acknowledged.

First, the threshold coefficient k (in Equation (8)) was based on empirical observations, and it is influenced by characteristics of the measurement setup, such as probe positioning, device architecture, background noise level, and amplification chain. This dependence is typical for EM based detection systems. However, a more systematic exploration of how k behaves under varying conditions would help further generalize the method.

Second, although classical detection methods such as energy thresholding and correlation were discussed, the study did not include a full quantitative comparison against these baselines. Such an evaluation would clarify under which conditions deep-learning-based detectors offer measurable advantages and where traditional approaches may still be competitive.

Together, these limitations outline directions for future work, including structured analysis of k sensitivity, investigation of measurement setup dependency, and quantitative benchmarking against classical EM detection techniques.

9. Conclusions

The proposed autoencoder–CNN framework introduces an effective and fully automated approach to analyzing electromagnetic emissions generated by cryptographic devices. By combining unsupervised anomaly detection with supervised classification, the system autonomously detects, localizes, and identifies cryptographic activity directly from continuous EM traces.

This method shifts the focus of side channel analysis from offensive exploitation toward defensive monitoring and hardware integrity assurance.

It provides a practical tool for noninvasive device inspection, capable of recognizing different block cipher algorithms with high accuracy. Importantly, the autoencoder can detect subtle anomalies even when signal amplitudes remain close to the noise level, demonstrating high robustness under realistic conditions.

Despite its capabilities, this research also presents several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the framework exhibits a degree of dependence on the specific hardware platforms used during data acquisition, such as STM32 or RP2040, which may restrict its portability across heterogeneous embedded systems. Second, the system is sensitive to variations in probe placement—shifts beyond a certain threshold can noticeably influence the reconstruction error and classification accuracy, limiting robustness in uncontrolled measurement setups. Moreover, the proposed approach is not intended for key extraction and focuses solely on identifying the type of cryptographic algorithm present in the EM trace.

Beyond research applications, the framework offers significant potential for cybersecurity monitoring of embedded and IoT systems. With further optimization, it can evolve into a real-time monitoring platform, continuously analyzing EM emissions to detect unauthorized cryptographic operations, hidden firmware behavior, or hardware Trojans. Such systems could play a vital role in ensuring trustworthy and resilient embedded security, enabling continuous, noninvasive supervision of cryptographic processes at the physical layer.