Abstract

This review investigates the application of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in biomedical informatics, encompassing domains such as medical imaging, genomics, and electronic health records. Through a systematic analysis of 43 peer-reviewed articles, we examine current trends, as well as the strengths and limitations of methodologies currently used in real-world healthcare settings. Our findings highlight a growing interest in XAI, particularly in medical imaging, yet reveal persistent challenges in clinical adoption, including issues of trust, interpretability, and integration into decision-making workflows. We identify critical gaps in existing approaches and underscore the need for more robust, human-centred, and intrinsically interpretable models, with only 44% of the papers studied proposing human-centred validations. Furthermore, we argue that fairness and accountability, which are key to the acceptance of AI in clinical practice, can be supported by the use of post hoc tools for identifying potential biases but ultimately require the implementation of complementary fairness-aware or causal approaches alongside evaluation frameworks that prioritise clinical relevance and user trust. This review provides a foundation for advancing XAI research on the development of more transparent, equitable, and clinically meaningful AI systems for use in healthcare.

1. Introduction

Advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) are transforming biomedical practices, bioinformatics approaches, and healthcare more broadly. However, the advent of AI has been accompanied by concerns from a significant portion of practitioners and discerning members of the public/patients due to the black-box nature of these systems and their inherent lack of transparency. This sparks unease, particularly in sectors like healthcare, where a flawed decision-making process can lead to significant and potentially devastating consequences [1].

The scientific community within the field of AI is addressing this by investigating methodologies to enhance the interpretability of models and, consequently, the trust of their users. Such solutions are commonly grouped under the umbrella name of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI), which is an established discipline that includes methods and techniques that aim to make the outputs of Machine Learning (ML) models understandable to humans [2].

The need for XAI in clinical environments is driven by several factors that go beyond the technical details of the model. Healthcare professionals are used to making decisions that are informed by knowledge and supported by evidence from established medical tests. Consequently, the lack of rationale for decisions generated by AI-based systems results in diminished trust and increased reluctance among clinicians to employ these technologies, particularly when patient safety is concerned and when the practitioners are operating within a framework that currently lacks well-developed policies regarding risks and liability for decisions delegated to a computer. Human errors in clinical settings that harm patients cannot always be prevented, but the liability is easily traceable. However, without legal frameworks in place, insurance companies may not be able to identify the source of liability when AI systems make harmful decisions [3]. This highlights the importance of considering Human-Centric Metrics (HCMs) when deploying AI models in such contexts.

In practice, legal systems interpret responsibility for AI-assisted decisions through the lens of liability regimes, which may not always consider the metrics used to judge the actual performance of the AI system [4]. Courts and public perspectives consider broader ethical and normative dimensions of AI use, not just a performance metric. This complex situation makes it even more difficult to accept the use of AI, even in scenarios where AI has been proven to be relatively reliable and interpretability is the key factor [5].

In this light, safe and practical integration of AI into healthcare workflows presents multifaceted complexities and pain points, necessitating that such integration be both transparent and clinically pertinent to earn public trust. XAI methodologies offer promising tools for facilitating this process; nonetheless, further development is needed to improve their ability to deliver comprehensive explanations. Given that XAI is a relatively recent discipline, efforts should be focused on making it more systematically organised and well established. The advantages of employing XAI methodologies are evident in certain contexts, as they can help to catch incorrect or biased decisions—occurrences of which are known to be significant (see e.g., [6,7])—thereby mitigating the risk of errors, discrimination, etc. To date, the majority of XAI approaches identify only specific features responsible for the final decision, lacking explanations that align with medical reasoning to substantiate decision-making. Based on these considerations, if it is to be used within healthcare settings, AI should

- 1.

- offer reliable insights;

- 2.

- build trust and assist clinicians and stakeholders in comprehending the underlying rationale for AI-generated decisions or identifying biased or erroneous decisions;

- 3.

- meet regulatory standards to ensure compliance and ethical implementation [8].

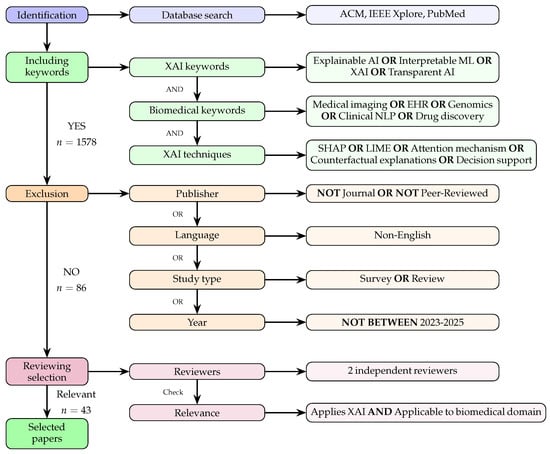

In this work, we examine existing methodologies and identify gaps in their applications while evaluating current trends across various biomedical domains, particularly in medical imaging. By mapping the XAI research landscape, this study aims to elucidate how explainability is employed to foster trust among clinicians. To identify pertinent literature, searches were systematically conducted across major academic databases, including the ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, and PubMed, for work published between March 2023 and Oct 2025. The following search keywords and Boolean combinations were used: (“explainable AI” OR “XAI” OR “interpretable ML” OR “Transparent AI”) AND (“medical imaging”, “EHR”, “genomics”, “clinical NLP”, “drug discovery”) AND (“SHAP”, “LIME”, “attention mechanisms”, “counterfactual explanations”, “decision support”). During screening, we excluded the following categories of records: non-English publications, non-journal or non-peer-reviewed sources (e.g., theses, book chapters, workshop abstracts), methodological XAI papers without a biomedical application, papers outside the medical or clinical domain, and duplicate records. Two reviewers independently screened all articles, and disagreements were resolved by discussion.

The process cumulated in the identification of a corpus of 86 pertinent articles (refer to Figure 1 for a schematic of the entire process). Subsequently, after we had scrutinised the articles in the main pool, our analysis concentrated on a carefully selected subset of 43 articles that were deemed particularly relevant and significant for our purpose. Two reviewers performed the final step, discarding those articles containing imprecisions.

Figure 1.

Literature-selection process for our XAI biomedical survey describing the steps of identification, inclusion, and exclusion and the selection criteria used in the final review. A total of 43 papers published between 2023 and 2025 were eventually selected.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows.

- Section 2 provides a short overview of the main types of XAI methods.

- Section 3 reviews how these methods are applied in biomedical informatics.

- In Section 5, we explore the key challenges XAI faces.

- Finally, in Section 6, we discuss possible directions for future research and offer the conclusion of our study.

2. Taxonomy of XAI Methods

In this paper, we adopt “XAI” as an overarching term that encompasses both post hoc explanation techniques and intrinsically interpretable modelling approaches. The term “interpretable ML” is used specifically to refer to models whose decision-making process is inherently transparent (such as decision trees and rule-based systems). The phrase “transparent AI” is avoided, although this term appears in some of the articles we reviewed. Instead, we adopt “XAI” as the standard terminology throughout this manuscript to maintain consistency.

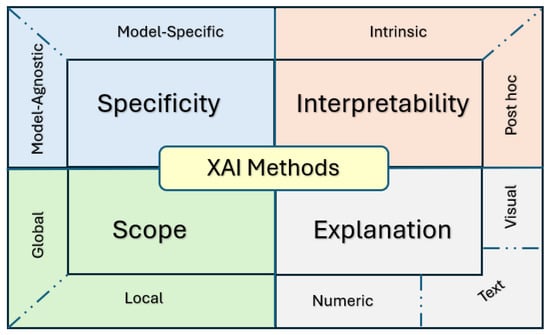

Understanding the various categories of XAI methods is key to choosing the most appropriate XAI tools based on model architecture, specific use cases, or the needs of end users. This is particularly critical in the healthcare sector, where trust and transparency are pivotal. XAI methods are generally classified according to four main criteria.

- Specificity (S).Specificity discriminates between approaches that are Model-Specific (M-S), i.e., their working mechanisms are specific to one model architecture, or Model-Agnostic (M-A), i.e., their mechanisms can be applied to any AI model regardless of the specific architecture [9].

- Scope of Explanation ().This can be Global (G), with an approach capable of explaining the overall behaviour of the model; Local (L), with an approach that explains a single specific prediction made by the model; or Both (B), with an approach that can address aspects of both global and local interpretability [10].

- Model Interpretability (MI).This can be Intrinsic (I), usually for simple models whose working mechanism is defined in such a way that they can be explained by design, or Post Hoc (P), for models whose complexity requires the application of approaches to analyse predictions only after they have been trained to generate an explanation [11].

- Explanation Modalities (EM)This criterion categorises the XAI methods based on the format/s of the explanations they provide as output [9], which may include measures of or visualisation of how specific features contributed to the decision, rule-based logic explanations, example-based explanations, and text-based summaries.

Each criterion focuses on a specific aspect of the method or the type of explanation it generates; the criteria can therefore be used in conjunction to describe an XAI approach in detail (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Taxonomy of XAI methods.

2.1. On Model-Specific and Model-Agnostic Methods

Model-Specific (M-S) explainability is achieved with methods that are optimised for or closely linked with a specific model architecture, e.g., Decision Trees (DTs) and Neural Networks (NNs).

The methods that are widely used for models having a tree structure are usually called “path analysis” and aim at explaining each single step. In DT, this is made possible by navigating the tree structure from top (root node) to bottom (leaf node) [12].

Similar strategies are infeasible for NNs, whose intricate architecture and operational mechanisms necessitate the use of internal elements such as weights, activation functions, and attention mechanisms to return explanations that are precise and easily comprehensible [13]. In this case, M-S XAI applications are still possible but cannot be universally applied across diverse architectures or models with varying parameters or operational logic [14].

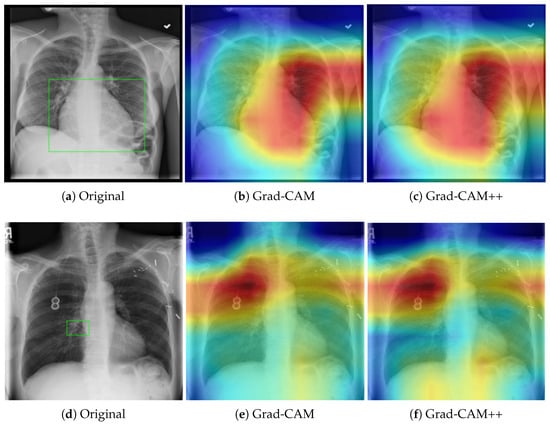

Visualisation methods are useful when dealing with NNs, in particular in healthcare applications. For example, attention maps are widely used in transformer and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) models to show which parts of the input the model is focusing on [15]. Other examples include saliency maps [16] and Grad-CAM [17], which are often used for Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). They highlight important regions in an image, helping to visualise which parts of the image influenced the model’s prediction.

Different versions of Grad-CAM exist, such as Grad-CAM++ [18], which handles multiple instances of objects in an image, and LayerCAM [19], which generates more detailed heatmaps, considering features across different layers. Examples of Grad-CAMs explanations are provided in Figure 3, which shows their application to a thoracic x-ray inspection task.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Grad-CAM and Grad-CAM++ saliency maps on chest X-rays for cardiomegaly (top row: panels (a–c)) and atelectasis (bottom row: panels (d–f)). The green frame in (a,d) indicates the areas of interest. Red regions indicate areas of high feature importance, while blue regions represent areas of low relevance. Grad-CAM++ provides finer localization and improved boundary delineation compared to standard Grad-CAM, enhancing interpretability.

In the top panel (Cardiomegaly), both Grad-CAM and Grad-CAM++ consistently highlight the enlarged cardiac silhouette, corroborating clinical markers of cardiac enlargement. The bottom panel (Atelectasis) shows the concentration of attention at the base and periphery of the lung. Notably, Grad-CAM++ provides more precise boundary delineation, reducing diffuse activation and improving interpretability. However, both methods require clinical validation to confirm that highlighted regions correspond to actual pathological findings rather than spurious correlations.

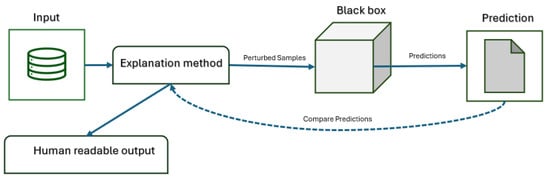

Differently, M-A techniques explain predictions by testing any model with different inputs and observing the results [20]. As shown in Figure 4, the explanation algorithm (e.g., SHAP, LIME) perturbs input samples, feeds them to the black-box model, collects and compares predictions, and generates a human-readable explanation. The model remains untouched, ensuring the approach can be applied to any predictive system regardless of its internal structure. Grad-CAM++ provides more precise localization, but both methods require clinical validation to confirm alignment with actual pathology.

Figure 4.

Workflow of model-agnostic explanation methods.

These approaches are the most flexible and can be virtually applied to any framework, as they are based on broad principles for interpreting input–output signals and thus are highly scalable and adaptable. Hence, they are also simpler to use and applicable to entire pipelines wherein some incompatibilities prevent M-S models from being applied to explain a decision made through a cascade of AI-driven steps.

Two well-known examples of model-agnostic explanation methods are Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) [21] and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) [22]. LIME operates by making incremental alterations to the input data and observing the resulting variations in the model’s predictions. This approach renders it adaptable and applicable to nearly all ML models. Differently, SHAP employs concepts from game theory to calculate the contribution of each feature to a prediction, which also enables its applicability across a diverse array of model types regardless of their working mechanisms (more details follow in Section 3). SHAP is known for its high computational cost, as it requires evaluating all possible combinations of the so-called “feature coalitions”, the number of which can increase significantly (exponentially) in the presence of high-dimensional data and when dealing with “complex” models. To address this challenge, various approximation techniques have been proposed to calculate the contributions of individual features; these techniques can be divided into two main categories: replacement and estimation [23].

Estimation techniques determine how subsets of features are selected and evaluated during Shapley value computation (e.g., sampling or Kernel SHAP), while replacement strategies define how the values of features not included in a selected subset are simulated (e.g., substituting baseline values or samples from a distribution).

As in many other scientific domains, no universally preferred approach can be identified. Therefore, it is important to determine which method is most suitable for a given scenario. Generally, M-A approaches are more applicable and may be the only choice in the presence of certain complex models [24]. However, their general-purpose nature makes them less accurate than M-S methods [25]. In conclusion, if an M-S method is available for analysing a particular decision, it should be employed or at least tested before an M-A approach is tried, as the latter may miss important internal dynamics of the model and occasionally yield less accurate results [26].

2.2. Scope of Explanation

The level of detail offered when interpreting or explaining a model is also commonly referred to as the “granularity” of the returned explanation in the XAI literature. XAI techniques offer different options on this regard, including (a) Global Explainability (overall model behaviour), which provides insights into the entire model’s behaviour across all inputs, and (b) Local Explainability (single prediction), which explains single predictions rather than overall model behaviour.

One widely used approach across both local and global interpretability is feature importance, which examines the impact of individual features on predictions. Feature importance is a flexible concept that bridges both local and global explainability, depending on whether it captures average behaviour across all predictions (global) or details the impact of individual features on a single decision (local).

Various levels of granularity can be used to explain different aspects of model behaviour to adjust to the distinct objectives of different stakeholders, such as elucidating AI-driven diagnoses and rationalising decisions.

Table 1 presents several prevalent and contemporary XAI methodologies, classified according to their level of explanation granularity to differentiate between local and global attribution methods.

Table 1.

An overview of established XAI methods for feature attribution, showing different combinations of specificity and scope. Abbreviations: S→Specificity, SE→Scope of Explanation, M-A→Model-Agnostic, M-S→ModelSpecific, G→Global, L→Local, EHR→Electronic Health Records.

2.3. Intrinsic and Post-Hoc Approaches

Models that are intrinsically interpretable because of their simplicity or structure allow users to understand the results without necessarily requiring additional methods to generate explanations. While these methods offer interpretability, they may lack predictive power compared to more complex models [33].

DT exemplifies a highly interpretable decision-model structure [34]. They are easy to visualise and understand, with a clear logic of decision and leaf nodes in a tree graph. The decision process is straightforwardly traceable from the root to an outcome (leaf), and feature importance is easily determined by closeness to the root node.

Linear regression models are also simple to explain by inspection of the feature coefficients, which directly show how much each input affects the prediction.

Similarly, rule-based systems are based on logic operators that intrinsically provide explanations [35], removing any uncertainty with regard to the rationale behind the decision.

When model complexity does not allow for these considerations, post hoc approaches can be used after training without altering the model’s architecture. These methods approximate the model’s behaviour around specific instances. They often rely on local simplifications that do not capture the global or causal logic of the underlying model, leading to misleading or incomplete explanations [36].

Moreover, post hoc explanations typically reveal correlational associations rather than causal mechanisms and do not necessarily represent fairness or transparency with regard to model output [37,38]. Evaluating fairness requires deeper audits, counterfactual simulations [39], and subgroup analyses (i.e., [40]) beyond surface explanations.

2.4. Explanation Modalities (Visual, Textual, Symbolic)

Different methods return different outputs. Nonetheless, they can be processed in multiple ways for presentation to the audience. In healthcare domains such as radiology, visual elements predominate; however, augmenting them with textual or alternative modalities may also be beneficial.

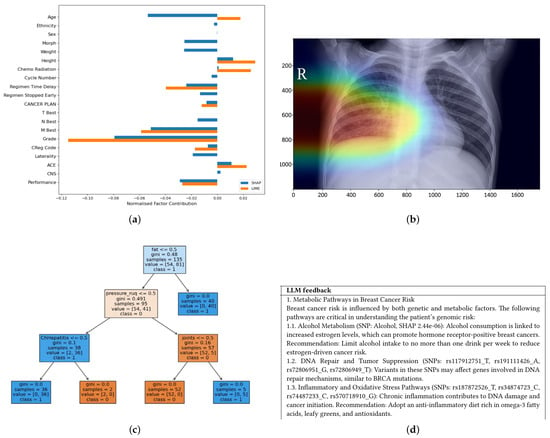

Examples of visualisations of different modalities of explanations are illustrated in Figure 5. The bar charts in Figure 5a show SHAP and LIME feature-importance results for tabular or EHR-based models. In this example, both methods consistently rank key clinical variables such as Grade and MBest, providing clinicians with clear insight into the factors that most strongly influence Covid-19 survival and supporting personalized treatment decisions.

Figure 5.

An example showing different XAI modalities used in XAI through (a) a simple bar chart showing explanations for predictions of life expectancy in lung cancer (b) visual Grad-CAM heatmaps of a lung disease (c) symbolic logic trees, and (d) textual explanations generated by an LLM. (a) SHAP & Lime Bar Chart [41]. (b) Grad-CAM Heatmap [42]. (c) Tree-Based Explanation [43]. (d) Text-Based Explanation [44].

Heatmaps generated by Grad-CAM (Figure 5b) highlight the image regions that most influenced the model’s prediction. In chest X-rays, Grad-CAM can localise opacities suggestive of pneumonia; in MRI scans, it can highlight tumour regions. This spatial attribution aligns with radiologists’ reasoning and helps verify that the model attends to clinically relevant areas rather than artefacts.

Rule-based explanations (Figure 5c) are valuable in genomics and pathology, where decision paths can be expressed as interpretable conditions, supporting compliance and formal reasoning in clinical workflows. Text-based summaries (Figure 5d) complement visual outputs by explaining high-risk predictions in natural language, as by highlighting breast cancer patients with elevated risk scores, thereby improving accessibility for non-technical stakeholders and building trust in the predictions.

The textual, visual, and symbolic elements demonstrate how each modality offers distinct affordances based on audience needs and model interpretability. Ideally, the outputs of the XAI methods should be analysed and represented through multiple modalities to generate further insight into the system.

2.5. Modalities in Medical Imaging

Visual explanation methods play a critical role in AI used in medical imaging by providing localised intuitive insights into the behaviour of the model.

Visualisation tools like Grad-CAM help explain deep learning models by showing which parts of an image a CNN focuses on and are typically applied to models that have already been trained [45,46].

Although visual descriptions provide graphical or spatial indications of the model’s primary areas of emphasis, which can be advantageous in numerous contexts, there remain shortcomings or unresolved issues that necessitate additional research efforts to align these approaches more closely with clinical environments. For example, several XAI methods for medical imaging have been found to disproportionately focus on pixels that significantly influenced the decision. However, these pixels may not correspond to clinically relevant image areas [47]. This suggests that, irrespective of the XAI method’s validity, the final decision still requires human validation [48], which is sometime challenging if clinicians have not been trained in interpreting such visualisation maps.

To overcome this problem, other methods can also be used or added to include local approximations like those resulting from the application of LIME and attribution of input features such as SHAP. Textual explanations, given in natural language or symbolic text, make it easier for clinicians to understand XAI method theorems. However, there is a risk that these explanations may oversimplify the situation and misrepresent the model’s logic [49].

The previously mentioned symbolic and logical interpretations based on decision sets, symbolic reasoning, and logical rules are less prone to misinterpretation. This modality is excellent for formal reasoning and compliance [50] but less effective when dealing with high-dimensional or unstructured data [51].

2.6. Overview of the Main XAI Techniques

LIME explains individual predictions by generating synthetic perturbations around an input instance—perturbing pixels for images, sampling from a distribution for tabular data, or masking tokens for text—and querying the black-box model to obtain predictions for the perturbed samples [21].

An interpretable surrogate model (e.g., a sparse linear model such as Lasso) is then fitted to this weighted dataset. The sparsity constraint is essential, as it forces the explanation to highlight only the most influential features. By analysing the coefficients of this locally faithful surrogate, LIME identifies which input features most strongly influence the specific prediction [21].

Due to its flexibility and applicability to diverse data types [52], LIME has become popular in biomedical domains such as medical imaging and EHR analysis. However, its explanations are sensitive to the perturbation distribution and kernel width, which are often chosen heuristically. This can cause instability, where explanations vary across runs due to sampling randomness. Moreover, LIME provides only a local approximation, which may not faithfully reflect the model’s global behaviour or decision logic across the full feature space [53].

SHAP explains model predictions by quantifying the contribution of each input feature to the deviation in the model’s output from a specified baseline value, typically the mean prediction over the dataset. The exact computation of Shapley values necessitates evaluating the model on all possible subsets of features, which leads to an exponential increase in computational complexity as the number of features increases. To address this intractability, SHAP incorporates approximation methods (e.g., KernelSHAP, TreeSHAP) that render the estimation of Shapley values computationally feasible [22].

SHAP supports both local (per-instance) and global (dataset-level) explanations and is widely used in biomedical tasks such as risk prediction, biomarker analysis [54], and multimodal integration [55]. Its theoretical grounding contributes to its popularity, though the computational cost and assumptions about feature independence remain important limitations [22].

Attention mechanisms, originally introduced for neural machine translation [56], are now widely adopted in deep learning architectures for biomedical imaging (e.g., Vision Transformers [57]), time-series modelling (e.g., EEG [58]), and multimodal fusion ([59]). These mechanisms compute dynamic, context-aware weights over input elements.

Attention typically relies on learned Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) projections. The attention weights are obtained by computing the scaled dot-product between Q and K, then implementing Softmax normalisation. In practice, this produces spatial attention over image regions, temporal attention over sequential data, or feature-level attention in tabular biomedical records. These weights offer intrinsic interpretability by revealing the elements the model focuses on during prediction [60].

Attention-based explanations are often intuitive and align with clinical reasoning [61]. For example, they may highlight tumour regions in radiological scans [62] or critical segments in physiological signals [63]. However, attention reflects correlational importance rather than causal influence. Attention distributions can be unstable or misleading, particularly in models with multi-head attention or models in which shortcut learning occurs, making careful validation essential in clinical applications [64,65].

3. Applications in Biomedical Informatics

We conducted a comprehensive literature review that offers an extensive overview of diverse applications, use cases, and emerging trends in XAI within the biomedical AI domain. We summarise the findings from this survey in Table 2 and Table 3, which reports the key details derived from the analysis, as presented in the following sections.

3.1. Genomics and Omics Data

In the domain of genomics, SHAP has been applied to explain the discovery of disease-relevant biomarkers, particularly for the prediction of Alzheimer’s disease [66] and colorectal cancer [67]. These papers have leveraged SHAP values to rank genetic features by importance and, in some cases, applied dimensionality-reduction techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) to project SHAP-based embeddings into interpretable visual clusters [67]. Another example from [68] has facilitated the identification of disease subgroups with distinct molecular profiles. However, it is worth reporting that such approaches often lack validation from clinical stakeholders.

3.2. Electronic Health Records

In predictive healthcare applications, SHAP has been used to interpret tree-based models such as XGBoost [69], facilitating the identification of key clinical and demographic risk factors. For example, SHAP has been applied to models predicting stroke risk based on Electronic Health Record (EHR) [70] and changes in HbA1c levels in diabetes management [69], providing transparency into the contributions of specific patient characteristics.

Similarly, in cardiovascular applications such as generating prognoses for acute myocardial infarction, SHAP has been employed to produce both global and local feature attributions, as well as to support counterfactual reasoning [71].

3.3. Time Series and Clinical Monitoring

Models for time series rely on temporal patterns, making feature importance dependent on the position within a sequence. This introduces additional complexity to interpretability compared to static data. Most existing XAI tools, such as SHAP and LIME, were originally developed for tabular or image data and require adaptation before they can be used in time-series applications. Popular approaches proposed for use in time series include, among others, integrated gradients and DeepLIFT [72]. As the name suggests, integrated gradients calculate feature-level contributions by integrating the gradients of a model’s output with respect to its input features along a straight path from a baseline (typically zero or a neutral input) to the actual input. In contrast, DeepLIFT assigns importance scores to input features by calculating the difference between their activation of each neuron and a reference (or baseline) activation and (back)propagating these differences through the network via modified chain rules. DeepLIFT demonstrated superior performance over SHAP and LIME in explaining LSTM-based alert classification. In part, this is due to the fact that it does not need gradient calculations and hence avoids the vanishing gradient issue and provides better fidelity, consistency, and alignment with expert assessments.

Traditional SHAP methods assume regular time steps and static inputs, limiting their applicability to irregular time series. Building on these developments, [73] introduces a framework for explainable temporal inference in irregular multivariate time series, with a focus on early prediction of multidrug resistance in ICUs. The framework incorporates three complementary XAI components: (1) pre hoc feature selection using Causal Conditional Mutual Information (CCMI), (2) intrinsic Hadamard Attention for variable-level interpretability, and (3) post hoc IT-SHAP for fine-grained temporal attribution. CCMI further improves transparency by selecting causally relevant features prior to model training, filtering out redundant or irrelevant inputs. Hadamard Attention enhances interpretability by applying element-wise weighting across both time steps and features, effectively capturing temporal dependencies in irregular multivariate time series. IT-SHAP extends SHAP to handle irregular timestamps, missing data, and variable-length sequences, enabling time-resolved explanations for each variable at each time step.

SHAP-like approaches have also supported interpretability in privacy-sensitive architectures through the use of federated and meta-learning in medical IoT monitoring systems [42].

3.4. Emerging Approaches

Another emerging direction in XAI involves the integration of domain-specific or symbolic knowledge into model training to enhance both accuracy and interpretability. Neuro-Symbolic AI approaches [74], such as those incorporating semantic loss functions, enable models to respect domain constraints during learning. For instance, recent work in human-activity recognition demonstrates that enforcing symbolic logic through semantic loss improves model reasoning by penalising predictions that violate contextual constraints [75]. This approach provides a mechanism for embedding structured domain knowledge directly into the training objective, thereby improving context awareness without requiring symbolic reasoning at the time of inference.

Similarly, Physics-Informed Deep Learning (PIDL) [76] makes use of equations describing laws of physics or other known biological principles in the loss function or in the activation functions of neural models. This allows models to adhere not only to patterns observed in data but also to validated domain constraints. As a result, PIDL enhances generalisability and ensures model outputs remain within plausible physiological or physical bounds, which is particularly valuable in high-stakes fields like engineering and medicine [15].

For example, in the context of MRI analysis, PIDL has been applied to incorporate domain-specific knowledge into deep learning models. The approach generates intrinsic, model-specific explanations, often through attention mechanisms, to highlight clinically significant features such as tumour regions [15,76]. Although this improves interpretability and model trustworthiness [77], the method depends on the quality and specificity of the encoded physical constraints and has not yet been validated across diverse datasets. Furthermore, its performance is highly dependent on access to high-quality annotated data [78].

In addition, enhancing model interpretability at the architectural level can significantly improve explainability. The study in [79] presents Mathematics-Inspired models as a new class of ML architectures designed to tackle the black-box problem of deep neural networks. These models promote design transparency by leveraging statistical and mathematical foundations (such as PCA, Canonical Correlation Analysis, and Statistics-Guided Optimization), which inherently support interpretability.

Collectively, domain-informed, Mathematics-Inspired and neuro-symbolic strategies reflect a shift toward embedding meaningful priors into AI systems, enabling them to reason within the constraints of clinical or physical logic. This not only improves prediction quality, but also enhances user trust by ensuring explanations are grounded in domain knowledge.

Another related line of work, exemplified by MiMICRI [80], explores the use of counterfactual explanations tailored for medical imaging tasks such as cardiovascular diagnosis. Unlike generic counterfactuals, MiMICRI modifies input features in a way that maintains anatomical plausibility, e.g., adjusting ventricle-wall thickness or simulating changes in blood flow, thereby ensuring the interpretability and realism of generated counterfactual instances. However, this approach may face performance limitations, particularly in generating real-time counterfactuals for high-resolution 3D medical imaging.

Visual explanation techniques have become central to the interpretation of deep learning models in medical imaging. Methods such as Grad-CAM, Grad-CAM++, LIME, LayerCAM, and Integrated Gradients are frequently used to generate saliency maps or super-pixel visualisations, which help localise the model’s attention to pathology-relevant regions in input images other than areas of predominant feature importance (a problem discussed in Section 2.5). These visual cues are particularly valuable in clinical settings, where model interpretability can directly impact diagnostic confidence and decision-making. These techniques have seen widespread use in imaging domains including COVID-19 diagnosis, gastrointestinal endoscopy, lung and breast cancer classification, and dental imaging [45,81,82,83,84]. For instance, post hoc explanation methods such as Grad-CAM and LIME are commonly applied after training to explain predictions in models for COVID-19 classification and myocardial infarction prognosis [71,85]. These visual explanations allow for retrospective verification of model decisions and can help uncover reliance on spurious features. Some efforts went beyond static saliency mapping by stress-testing the robustness of visual explanations. For example, patch-perturbation experiments have been run to evaluate whether models rely on true pathological features or irrelevant artefacts. In [42], saliency maps generated before and after applying artificial image patches were compared; significant shifts in focus indicated that the model may have learned spurious correlations rather than medically meaningful features.

Similarly, large language models (LLMs) have been applied to generate personalised healthcare recommendations. For instance, ref. [44] uses SHAP values to rank features by importance; these are then provided as contextual input to the LLM.

A notable contribution to this area is the integration of multiple explanation techniques in ensemble XAI frameworks. Some articles combine Grad-CAM, LIME, and SHAP to generate both global and local explanations for diagnostic tasks [86]. One such example applies this ensemble approach to COVID-19 respiratory imaging, producing clinically relevant visualizations, although the outputs sometimes suffer from redundancy or internal inconsistency [80,81].

In gastrointestinal diagnosis using capsule endoscopy, models have been interpreted using Grad-CAM++, LayerCAM, LIME, and SHAP, but these articles often lack validation through user studies or clinician involvement [45,87]. In lung cancer classification, dual-path CNNs have been augmented with Grad-CAM++ and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) to produce high-fidelity visual explanations that align with tumour regions in CT scans, thereby enhancing clinical interpretability [66,82,88].

Additionally, attention-based mechanisms and gradient-based attribution methods such as Integrated Gradients have been employed to provide more focused and interpretable insights. These methods aim to highlight which specific features, such as brain regions, drug histories, or imaging biomarkers, contribute to a particular model prediction. For example, attention maps have been used to identify regions associated with the progression of neurodegenerative conditions such as hippocampal atrophy [89], while other models employ integrated gradients and SHAP-like visualisations to explain why a model predicts drug resistance in individual patients [90]. These approaches are particularly valuable for generating local, instance-specific explanations that can be readily interpreted by clinicians.

3.5. Other Medical Imaging and Multimodal Applications

Visual and hybrid XAI methods are extensively used across medical imaging applications to support model transparency. While ensemble approaches and advanced techniques like attention mechanisms and integrated gradients enhance interpretability, challenges remain, particularly around explanation redundancy, computational efficiency, and the lack of systematic user validation. These limitations underscore the need for human-centred design and evaluation strategies in future XAI development for clinical applications.

An important trend in XAI research within clinical domains is the combination of multiple explanation techniques to improve model interpretability. These ensemble approaches are particularly prominent in medical imaging applications, where deep learning models are often complex and require layered interpretive strategies. For instance, some articles employ Grad-CAM, LIME, and SHAP in tandem to generate global, post hoc explanations for tasks such as respiratory COVID-19 diagnosis [80]. While this strategy can improve interpretability by offering different perspectives on model behaviour, it may also introduce redundant or conflicting outputs that complicate clinical interpretation [91]. Similarly, in gastrointestinal imaging using capsule endoscopy, an ensemble of Grad-CAM, Grad-CAM++, LayerCAM, LIME, and SHAP has been used to explain deep learning decisions. However, this work lacks clinician-involved validation, raising questions about the real-world relevance of these explanations [87].

Lung cancer classification is another area where ensemble XAI has proven effective. Dual-path convolutional neural networks have been integrated with Grad-CAM++ and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) to both improve diagnostic performance and provide localized visual explanations aligned with tumour features in CT scans [66,88]. These combined methods enhance clinical usability, particularly when visual interpretations are required for trust and decision-making.

Beyond ensemble methods, attention mechanisms and integrated gradients offer another avenue for the use of interpretable AI. These techniques produce case-specific localised explanations by highlighting the characteristics that most influence the prediction made by a model, such as specific drugs or anatomical regions. For example, attention and gradient-based methods have been used to identify clinically relevant factors in drug-resistance prediction [90], as well as to pinpoint neuroanatomical markers, such as hippocampal atrophy, which is predictive of disease progression [89]. Such models not only increase transparency but also align more closely with the reasoning processes used by clinicians.

Additionally, SHAP has been incorporated into frameworks aimed at identifying mislabelled training examples in imaging data, quantifying data values, and detecting potential biases in model predictions [92].

Integrating Multimodal Information

Multimodal models integrating imaging data with structured clinical records have also benefited from SHAP. In these contexts, SHAP has been used to determine whether models attend to clinically meaningful features, improving the transparency and trustworthiness of decision-making in high-stakes domains such as in CT, MRI scans, neuro-imaging, and outcome prediction for intracerebral haemorrhage [90,93,94].

3.6. Discussion and Considerations from Further Applications

It is worth noting that a significant portion of the articles reviewed in the previous sections focus on post hoc techniques to generate explanations but do not favour specificity. Furthermore, while technical performance metrics are commonly reported in the wast majority of the studies, only a few include HCMs, which commonly include interpretability [67,68,95,96,97,98,99], actionability [45,66,69,81,100], user trust [72,101,102,103,104,105,106], and appropriate reliance [107].

These human-centric dimensions are crucial for bridging algorithmic output with real-world decision-making. Interpretability concerns how clearly a model’s decisions can be understood, especially by non-experts. Actionability extends this by assessing whether users can effectively leverage these insights to make informed choices or conduct informed interventions, bridging explanation and decision-making. User trust, meanwhile, reflects the confidence individuals place in the system’s outputs and is influenced by factors such as transparency, consistency, and alignment with user expectations and values. Appropriate reliance occurs when a human trusts the AI when it provides correct information and refuses to trust it when the information is incorrect. This concept highlights the alignment between the actual performance of the AI and the human decision to rely on it. Together, these metrics shift the focus from technical validation alone to real-world utility, making XAI systems not only intelligible but also empowering and reliable [108,109].

It is also clear that SHAP has become one of the most widely used XAI techniques in medical ML due to its ability to attribute prediction outcomes to individual input features in a theoretically grounded manner. Across the current literature, SHAP has been extensively applied to a range of tasks, including risk prediction [70], genomic analysis, multimodal integration [110], feature contributions [99,111,112], and assessment of outcome quality [100].

Table 2.

List of the 43 articles selected, along with the modalities studied, their domains of application, the names and links of the datasets used, and the access status. Details of datasets and types of access are provided whenever this information could be found. 30 of these articles use at least one public (n = 28) or access-controlled (n = 3) dataset. Abbreviations: EHR→Electronic Health Records, ICU→Intensive Care Unit, CT→Computed Tomography, MRI→Magnetic Resonance Imaging, NDA→Not Directly Applied (but claimed relevant to Biomedical domain), SNP→Single Nucleotide Polymorphism, Pri→Private, Pub→Public, Con→Access is controlled through a restricted portal that may either require prior approval or funding, ✗→information is missing from the revised manuscript.

Table 2.

List of the 43 articles selected, along with the modalities studied, their domains of application, the names and links of the datasets used, and the access status. Details of datasets and types of access are provided whenever this information could be found. 30 of these articles use at least one public (n = 28) or access-controlled (n = 3) dataset. Abbreviations: EHR→Electronic Health Records, ICU→Intensive Care Unit, CT→Computed Tomography, MRI→Magnetic Resonance Imaging, NDA→Not Directly Applied (but claimed relevant to Biomedical domain), SNP→Single Nucleotide Polymorphism, Pri→Private, Pub→Public, Con→Access is controlled through a restricted portal that may either require prior approval or funding, ✗→information is missing from the revised manuscript.

| Ref. | Modalities | Domain | Datasets | Links | Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [113] | Clinical Tabular | EHR | Cardiac MRI Phenotypes & Brain Volumetric MRI | [114] | Con |

| [15] | MRI | Medical Imaging | Brain Tumor MRI Dataset | [115] | Pub |

| [81] | X-ray | Medical Imaging | CAPE Model Development Dataset & Interpretation Evaluation Dataset & NIH Chest X-Ray Public Dataset | [116] | Pri & Pri & Pub |

| [45] | Endoscopy | Medical Imaging | Kvasir-Capsule Dataset | [117] | Pub |

| [118] | Dermoscopic Images | Medical Imaging | Skin Cancer MNIST | [119] | Pub |

| [100] | ICU Tabular | EHR | Al-Ain Hospital ICU Electronic Health Records (EHR) Dataset | ✗ | Pri |

| [66] | SNP | Genomics | ADNI Genetic GWAS Dataset (Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative) | [120] | Pub |

| [82] | CT | Medical Imaging | IQ-OTH/NCCD Lung Cancer CT Dataset | [121] | Pub |

| [89] | MRI | Medical Imaging | Alzheimer MRI Dataset | [122] | Pub |

| [123] | Pathology Slides | Medical Imaging | Warwick-QU & Cancer Dataset | [124] & Unknown | Pub & Unknown |

| [110] | Oncology | Multimodal Data | GenoMed4All + Synthema MDS Training Cohort | [125,126,127] | Con |

| [71] | Clinical Tabular | EHR | Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry | ✗ | Pri |

| [85] | X-ray | Medical Imaging | Chest X-Ray Pneumonia Dataset & SARS-CoV-2 CT-scan dataset | [128,129] | Pub |

| [42] | X-ray | Medical Imaging | COVID-19 Radiography Database | [130,131] | Pub |

| [93] | CT | Medical Imaging | ICH for Non-Contrast Computed Tomography | ✗ | Pri |

| [90] | MRI | Medical Imaging | Simulated Bias in Artificial Medical Images (SimBA) | [90] | Pub |

| [87] | Institutional Review Board | Clinical Text & Notes | Institutional Review Board (IRB) Protocol Dataset | ✗ | Pri |

| [132] | X-ray | Medical Imaging | Tuberculosis (TB) Chest X-Ray Database | [133] | Pub |

| [80] | MRI | Medical Imaging | UK Biobank Cardiac MRI Dataset | [114] | Con |

| [134] | Microscopic PBS | Medical Imaging | C-NMC-19 & Taleqani Hospital Dataset & Multi-Cancer Dataset | [135,136,137] | Pub |

| [138] | MRI | Medical Imaging | Internal Single-Center Brain Metastasis MRI Dataset | ✗ | Pri |

| [68] | SNP | Genomics | CREA-AA Ex Situ Germplasm Collection | ✗ | Pri |

| [69] | Tabular Data | EHR | Finnish Real-World EHR Dataset of T2D patients | ✗ | Pri |

| [70] | Tabular Data | EHR | Kaggle Stroke Prediction Dataset & Kushtia Medical College Hospital | ✗ | Pub |

| [67] | Microbiome Data | Genomics | YachidaS_2019, YuJ_2015, WirbelJ_2019, ZellerG_2014, VogtmannE_2016 | [139,140,141,142,143] | Pub |

| [144] | Simulation Data & Structural Features | Multimodal Data | Simulated Molecular Structures and QM/MM Reaction Paths | [145] | Pub |

| [96] | Imaging, Tabular Data | Multimodal Data | Survey and Interviews | ✗ | Pri |

| [146] | EHR & Clinical Tabular Data | Multimodal Data | MIMIC-III | [147] | Pub |

| [75] | Time Series & Tabular Data | Multimodal Data | DOMINO & ExtraSensory Dataset | [148] | Pri & Pri |

| [92] | Tabular Data | EHR | 22 Real-World Tabular | [92] | Pub |

| [46] | X-ray | Medical Imaging | Knee ArthroScan, Lung X-Ray, FracAtlas | [149,150,151] | Pub |

| [73] | ICU | Time-series | University Hospital of Fuenlabrada | ✗ | Pri |

| [82] | CT | Medical Imaging | IQ-OTH//NCCD Lung Cancer Dataset | [121] | Pub |

| [44] | SNP | Genomics | MalaCards & OMIM & DisGeNet & SympGAN | [152,153,154,155] | Pub |

| [107] | Image | NDA | CUB-200-2011 | [156] | Pub |

| [72] | Textual | NDA | ALERT Telegram Threat Dataset | [157] | Pub |

| [79] | Imaging | NDA | Japanese Female Facial Expression Database | [158] | Pub |

| [159] | Tabular Data | NDA | CIFAR-10 & CIFAR-100 & ImageNet-1K | [160,161,162] | Pub |

| [94] | CT & MRI | Medical Imaging | LIDC-IDRI & Duke Breast Cancer MRI Dataset | [163,164] | Pub |

| [86] | Ultrasound | Medical Imaging | Gallbladder Diseases Dataset | [165] | Pub |

| [99] | EHR, Text and Tabular Clinical Data | Multimodal Data | UCSF | ✗ | Pri |

| [112] | Tabular Data | EHR | Psychiatric Emergency Department Electronic Health Records | ✗ | Pri |

| [111] | MRI | Medical Imaging | Brain Tumor MRI Dataset & Large MRI Training Dataset | [115,166] | Pub |

Table 3.

Quantitative review of the 43 selected articles and their key characteristics. The table shows that there is no significant bias towards specificity or locality, but most papers studied are post hoc, with more than half of them focusing on medical imaging. Abbreviations: S→Specificity, SE→Scope of Explanation, MI →Model Interpretability, HCM→Human-Centric Metrics (), M-A→Model-Agnostic (), M-S→Model-Specific (), B→ Both, G→Global (), L→Local (), P→Post hoc (), I→Intrinsic (), EHR→Electronic Health Records, ICU→Intensive Care Unit, SNP→Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms, ✗→HCM is not used, ✓→HCM is used.

Table 3.

Quantitative review of the 43 selected articles and their key characteristics. The table shows that there is no significant bias towards specificity or locality, but most papers studied are post hoc, with more than half of them focusing on medical imaging. Abbreviations: S→Specificity, SE→Scope of Explanation, MI →Model Interpretability, HCM→Human-Centric Metrics (), M-A→Model-Agnostic (), M-S→Model-Specific (), B→ Both, G→Global (), L→Local (), P→Post hoc (), I→Intrinsic (), EHR→Electronic Health Records, ICU→Intensive Care Unit, SNP→Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms, ✗→HCM is not used, ✓→HCM is used.

| Articles n = 43 | n = 19 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref. | Area | Stakeholders | AI Method(s) Used | S | SE | MI | HCM |

| [113] | Difficult to deploy in real-world settings | Patients | SHAP | M-A | G | P | ✗ |

| [15] | Low interpretability in DL models | Practitioners | PIDL | M-S | L | I | ✗ |

| [81] | Model interpretability | Clinicians | Grad-CAM, LIME, SHAP | M-A | G | P | ✓ |

| [45] | Black-box nature of DL models | Gastroenterologists | Grad-CAM, LIME, SHAP, GradCAM++, LayerCAM | M-A | L | P | ✓ |

| [118] | Data privacy, model interpretability | Healthcare Providers | Saliency Maps, Grad-CAM | M-A | G | P | ✗ |

| [100] | Resource allocation, model transparency | Hospital Administrators | SHAP, Different plots | M-A | G | P | ✓ |

| [66] | Biomarker Identification, Model Interpretability | Neurologists | SHAP | M-A | G | P | ✓ |

| [82] | Improving interpretability of CNN | Radiologists, Oncologists | CNNs, Grad-CAM, SHAP, Attention Mechanisms | M-S | L | P | ✗ |

| [89] | Efficient AI-based screening | Neurologists, Radiologists, Researchers | EfficientNetB0, Dual Attention Mechanisms | M-S | G | P | ✗ |

| [123] | Enhancing diagnostic accuracy | Radiologists, Oncologists | Adaptive Aquila Optimizer, DL Models | M-S | L | P | ✗ |

| [110] | Data scarcity in rare cancers | Oncologists, Researchers | MOSAIC Framework, SHAP, ML | M-S | G | P | ✗ |

| [71] | Interpretability, Trust | Cardiologists | Tree-based models, SHAP, DiCE | M-A | G | P | ✗ |

| [85] | Trust, Usability of Explanations | Radiologists | Grad-CAM, LIME | M-A | L | P | ✓ |

| [42] | Saliency map reliability | Radiologists | Grad-CAM | M-S | L | P | ✗ |

| [93] | Model interpretability in critical care | Neurologists, Radiologists | SHAP, Guided Grad-CAM, CNNs | M-S | G | P | ✗ |

| [90] | Systematic bias in AI models | Model Developers, Policymakers | Fairness Metrics, SHAP | M-A | G | P | ✗ |

| [87] | Uncertainty in AI predictions | Researchers, Health Planners | Transformers, Calibration Layers | M-S | G | P | ✓ |

| [132] | Interpretability of transformer-based models | Radiologists, Pulmonologists | Vision Transformer, Grad-CAM | M-S | L | P | ✗ |

| [80] | Realism and relevance of counterfactuals | Cardiologists, Researchers | MiMICRI Framework | M-A | L | P | ✗ |

| [134] | Trade-off between transparency and model performance | Haematologists, Pathologists | CNN, Grad-CAM, CAM. IG, LIME | M-S | L | P | ✗ |

| [138] | Interpretability of longitudinal monitoring tools | Neurosurgeons, Oncologists | Streamlit, Grad-CAM, SmoothGrad | M-S | L | P | ✗ |

| [68] | Model transparency in breeding programs | Plant Geneticists, Breeders | SHAP, Regression Models | M-A | G | P | ✓ |

| [69] | Improve individualized treatment strategies and interpretability of predictions | Endocrinologists, Public Health Officials | XGBoost, SHAP | M-A | G | P | ✓ |

| [70] | Improve predictive accuracy and interpretability for clinical decision-making | Neurologists, General Practitioners | Ensemble Models, SHAP, LIME | M-A | G | P | ✓ |

| [67] | Improve interpretability of microbiome-based disease prediction, feature interpretation | Oncologists, Microbiome Researchers | SHAP | M-A | G | P | ✓ |

| [144] | Understanding enzyme dynamics and resistance | Structural Biologists, Pharmacologists | SHAPE, XGBoost | M-A | G | P | ✓ |

| [96] | Interprets medical reality and supports clinicians | System Designers, Clinicians | MAP Model, Transparent design | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [146] | Enhance diagnostic and treatment recommendations | Clinicians, Medical AI Developers | Transformer | M-S | L | P | ✓ |

| [75] | Deploy-ability of NeSy HAR | Researchers, Developers | Semantic Loss Functions, GradCAM | M-S | G | I | ✓ |

| [92] | GBDT explainability, efficiency | ML Practitioners | TREX, BoostIn | M-S | L | P | ✗ |

| [46] | Generalization across datasets | Radiologists, clinicians | EfficientNet-B0, ViT, Swin Transformer, CBAM, Grad-CAM | M-S | L | P | ✗ |

| [73] | XAI methods for time-varying outputs | ICU clinicians | IT-SHAP, CCMI, Hadamard Attention | M-A | B | B | ✓ |

| [82] | Interpretability in CNN-based models | Radiologists, Oncologists | Multi-Head Attention (MHA), Grad-CAM, SHAP | B | B | P | ✗ |

| [44] | Integration between risk prediction and actionable recommendations | Oncologists, GPs | hybrid Transformer-CNN, SHAP, LLMs | M-A | B | P | ✗ |

| [107] | Human–AI collaboration and Explainable A | Designers, Researchers | Deception of Reliance (DoR) metric | M-A | L | P | ✓ |

| [72] | Lack of labeled Telegram data | Policymakers | RoBERTa+, Integrated Gradients, DeepLIFT, LIME, SHAP | B | B | B | ✓ |

| [79] | Transparency with design of DNs | Researchers | PCA, DCT, CCA | M-S | G | I | ✗ |

| [159] | Computational cost of exact Shapley values | Researchers | SHAP | B | L | P | ✗ |

| [94] | Limitations of classical image forensics | Researchers, Cybersecurity | SHAP, Back-in-Time Diffusion | M-S | L | P | ✗ |

| [86] | Misdiagnosis, heterogeneity in lesion appearance | Hepatobiliary Specialists | CNN with multi-scale feature extraction + Grad-CAM, LIME | B | L | P | ✗ |

| [99] | Social determinants | Clinicians, Policymakers | ✗ | M-S | G | P | ✓ |

| [112] | Early identification of suicide risk | Psychiatry | SHAP, BD plots | M-S | L | P | ✗ |

| [111] | Feature interpretability | Radiologists, Neurologists | SHAP | M-A | G | P | ✓ |

3.7. Comparison of XAI Methods

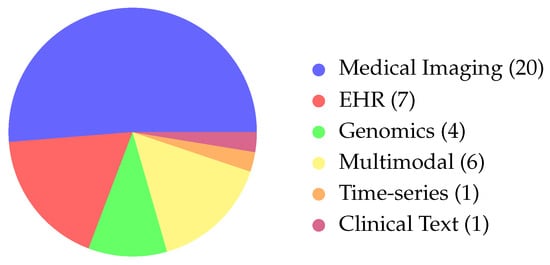

Based on the refined categorisation of the reviewed articles, biomedical applications were grouped into five main domains (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Distribution of modalities across the biomedical articles. We observe that the majority of the papers focus on Medical Imaging, with more included under Multimodal articles. (Abbreviations: EHR→Electronic Health Records).

Medical imaging was the most common focus, with 20 articles (≈51%), underscoring the dominance of radiology, ultrasound, and MRI-based explainability. The category EHR and clinical tabular data comprised seven studies (≈18%), confirming the ongoing importance of structured datasets for model development and interpretability. Genomics and other omics were under-represented, with only four studies (≈10%), despite a rising interest in precision medicine. Time-series clinical data (e.g., ICU monitoring, EEG) appeared in one study (≈3%), and multimodal biomedical applications (imaging, text, and clinical variables) were found in five articles (≈13%). Overall, these figures show a strong bias toward imaging-centred XAI, with limited use in genomics and longitudinal monitoring, highlighting the need for broader methodological work across biomedical domains.

SHAP is the most widely used explanation technique, followed by Grad-CAM, LIME, and attention-based methods. Usage varies by domain: medical imaging mainly uses saliency-based tools like Grad-CAM, while EHR and genomics articles rely almost entirely on SHAP for feature-level interpretability.

4. Evaluation Metric and Clinical Assessment

A central challenge in biomedical XAI is the absence of standardised and clinically grounded evaluation protocols. Many articles report explanations visually or descriptively, but few assess how well these explanations align with expert reasoning or support real-world clinical decision-making. Human-Centric Metrics (HCMs) are used unevenly across biomedical domains. Medical Imaging has the lowest rate of HCM adoption (four articles), relying mainly on technical saliency validation rather than human-centred evaluation. In contrast, EHR (three articles) and Genomics (two articles) integrate HCMs more robustly, likely because they support clinical decision-making and risk prediction, where user trust and human–AI collaboration are more critical. Evaluating an XAI system requires both technical metrics that assess explanation quality and task-based protocols that quantify clinical utility.

4.1. Quantitative Evaluation

These metrics evaluate how well an explanation corresponds to established biomedical knowledge. Common approaches include Intersection-over-Union (IoU) or Dice coefficients comparing saliency maps with radiologist-annotated regions [167], feature-ranking agreement between SHAP/LIME attributions [168], and histopathology image analysis for classification of rare tumours for imaging models [169].

Such metrics assess whether explanations highlight clinically relevant structures or concepts rather than spurious correlations. However, traditional evaluation of saliency or heatmap-based XAI methods often relies on qualitative visual inspection or loose metrics like the “pointing game” (checking whether the max pixel falls inside a region), and these metrics fail to distinguish among different levels of importance (e.g., localisation vs. discriminative features) [170]. Due to this limitation, different metrics have been proposed, such as the customized five-band score, which stratifies pixel attribution into bands (e.g., discriminative features vs localisation) [171].

4.2. Faithfulness Metrics

Fidelity measures how accurately the explanation reflects the underlying model behaviour [172], with techniques such as Faithfulness Correlation, Faithfulness Estimate, Infidelity, and Region Perturbation commonly used to assess it. High-fidelity explanations should reliably and consistently lead to specific, predictable changes in the responses of the model. Current fidelity metrics lack consensus and reliability, especially for complex, non-linear models, while some achieve perfect fidelity but see performance degrade in the presence of out-of-distribution (OOD) samples [172]. Multiple frameworks, such as [173], are used to evaluate the faithfulness of Explainable AI (XAI) methods. F-Fidelity addresses these problems by fine-tuning models with random masking and controlled stochastic removal during evaluation to keep inputs in-distribution.

4.3. Robustness Metrics

An explanation should remain stable under small perturbations to the input or model [174]. Metrics such as explanation variance, neighbourhood stability, and surrogate model consistency assess whether different runs or small input changes produce substantially different explanations. These are common issues particularly relevant to LIME, SHAP variants, and noisy biomedical datasets. Ref. [175] proposed a metric that evaluates XAI algorithms on multiple stability aspects, enabling objective comparison and better selection for real-world applications.

4.4. Clinician-in-the-Loop Evaluation

Beyond technical metrics, clinical utility must be assessed through structured user studies, as human factors research is essential for designing AI systems that fit clinical environments and user needs [176]. Current research emphasises human-centred design and regulatory compliance for XAI [177]. These human-centric assessments typically examine four critical dimensions: (1) diagnostic accuracy, comparing clinician performance with versus without AI explanations [178]; (2) confidence calibration, measuring alignment between subjective confidence and objective performance when using explanations [179]; (3) decision-time analysis, assessing whether explanations reduce cognitive burden and improve workflow efficiency [180]; and (4) appropriateness of reliance, evaluating clinicians’ ability to distinguish when to trust versus override AI recommendations [181]. Over-reliance may lead to automation bias and diagnostic errors, while under-reliance wastes the potential benefits of AI systems. Explanation design should incorporate uncertainty visualisation and confidence calibration to support appropriate reliance and informed clinical judgement.

5. Challenges

Despite the growing adoption of XAI in bioinformatics and healthcare systems, this review of the literature has identified several unresolved challenges that must be overcome in the coming years to facilitate the application of XAI in real-world clinical settings.

The lack of involvement of domain experts is one major problem. Many articles report techniques developed without clinical validation, and medical professionals are rarely involved in evaluating the generated explanations; the accompanying risk involves coming to erroneous conclusions or explaining clinically irrelevant aspects of the decision-making process [182]. This disconnect from clinicians can also undermine trust, making progress even harder.

A secondary concern arises from the observation that numerous scholarly publications fail to account for the limitations intrinsic to their implemented XAI methodologies or their underlying assumptions.The SHAP method exemplifies such concerns. It works on an assumption of feature independence [26] that rarely holds in real-world clinical datasets, where features are highly correlated in the vast majority of cases [183], and its use is rarely validated through user-centric activities. Many SHAP-based studies do not include clinician feedback or human-subject evaluations to assess the utility or clarity of the explanations provided (as highlighted by the overview in Table 3). This gap is particularly evident in genomics and imaging applications, where the clinical relevance of identified features may not be immediately apparent without expert input [66,68,100]. As a result, while SHAP facilitates algorithmic transparency, it does not guarantee interpretability from a clinical perspective, as argued in [184].

Another important consideration is the importance of choosing the most appropriate approximation method for the SHAP values. The study in [159] evaluated 25 different Shapley value-approximation techniques, revealing that M-S methods outperform M-A ones in terms of both accuracy and runtime. The study also found that mean imputation can distort feature contributions, particularly in non-linear models. Among the evaluated techniques, FastSHAP [185] emerged as a promising approach for deep learning applications. It remains the most-recognised and most-employed XAI technique.

Despite progress in XAI, we still need more reliable, human-centred, and clinically validated systems to ensure that explanations are not only technically sound but practically useful in healthcare. Diverse explanation strategies—such as highlighting key input features—can aid understanding, but they often tell only part of the story. As demonstrated by counterfactual models [39], alternative approaches can enrich trust, though explanation methods themselves may mislead if they are not critically evaluated. To avoid masking bias, XAI systems must be held to high standards of interpretability and accountability—especially as regulatory frameworks like the EU AI Act [186] and NIST’s AI Risk Framework [187] demand clarity and reliability in sensitive domains.

With this article, we report on omissions that we believe should not be overlooked in XAI articles. To advance the discipline, future articles should report details that allow replicability of the results and give insights into some aspects such as, e.g., computational overhead, to allow comparisons and provide interesting insights into the proposed method. In this regard, ref. [188] reported that several articles on XAI do not justify the sample sizes used or explain how their findings apply to other datasets. These issues should be addressed. We also observe in Table 2 that about 30% () of the papers studied made use of private datasets, which may make replication even harder.

We also encourage ablation studies to remove redundant algorithmic components in published frameworks. The presence of redundant components in ensemble methods is becoming more common due to the current tendency to combine several XAI methods. Sometimes, this can lead to the generation of conflicting explanations, which may confuse rather than clarify model predictions [189].

These discrepancies between explanations arise from methodological differences (e.g., local feature attribution vs. counterfactuals), the complexity of high-dimensional non-linear models, distribution shifts, unstable surrogate models, and conflicts between local and global interpretability. This also holds in visual tools like heatmaps, where conflicting feedback may highlight misleading patterns in the map instead of actual signs of diseases.

Such conflicts can undermine trust, distort decision-making, and put regulatory compliance at risk in high-stakes domains such as healthcare and finance. They are particularly common in developed countries like the UK. When methods are not harmonised, models exhibit large variability in feature importance; when explanation metrics are not standardised, the result is inconsistent and potentially misleading explanations [190].

The use of different explanations to analyse the behaviour of a model would result in a better understanding. The use of diverse explanation strategies—such as highlighting key input features—can aid understanding, but these strategies often tell only part of the story. As demonstrated by counterfactual models [39], alternative approaches can enrich trust, though explanation methods themselves may mislead if they are not critically evaluated. To avoid masking bias, XAI systems must be held to high standards of interpretability and accountability—especially as regulatory frameworks like the EU AI Act [186] and NIST’s AI Risk Framework [187] demand clarity and reliability in sensitive domains.

Finally, we have observed that approximately half of the papers selected in this study focus on medical imaging. A reason for this may be that AI image interpretation is generally done by complex back-box deep neural networks that are very difficult to interpret due to their nature. This is very different for other domains like textual information, where LLMs can easily provide plausible textual explanations that are also easily verifiable. We also note that medical imaging on its own is facing specific issues that may explain this focus. Indeed, interpreting medical images is time-consuming; this is especially true for CT or MRI scans, as experts usually look at them slice by slice. There is also an insufficient number of radiographers in some developed countries like the UK [191]; combined with reported human-level capabilities [192], this situation makes AI very promising as a tool for the domain. However, the adoption of AI in critical care can only be accepted if interpretability and explainability can be ensured to keep humans in the loop. Hence, it is not surprising to see a strong interest in the application of XAI to medical imaging.

6. Conclusions

Society is facing the conundrum of creating life-saving decision-making tools with human-level capabilities that cannot be used, as they provide neither interpretability nor explanability and thus face legal and ethical barriers. This review highlights the key role that XAI can play in the fields of bioinformatics and healthcare. As AI systems become increasingly integrated into clinical workflows and biomedical research, the demand for transparency, interpretability, and trustworthiness has never been greater. XAI methods are rapidly evolving, and this survey captures their growth by categorising them in a way that helps both developers and end users select the most appropriate techniques for their specific challenges.

We have shown how XAI is expanding its influence across a wide range of biomedical applications, including medical imaging—a domain studied in the majority of the papers we reviewed—genomics, EHR analysis, and clinical decision-support systems. In each of these areas, XAI serves as a bridge between high-performing black-box models and the need for real-world usability, accountability, and clinical relevance.

Despite identifying several promising research directions—such as causal explainability, human-in-the-loop systems, and domain-specific interpretability—we also uncovered persistent challenges. These include a lack of standardised evaluation metrics, limited generalisability across datasets, and insufficient clinical validation. Moreover, many articles suffer from issues related to reproducibility and lack of impact-focused design (that is, they do not align with clinically relevant needs).

The fact that fewer than half of the reviews are concerned with HCMs is also a concern, with only 19 papers out of 43 including human-centred validation. Indeed, XAI methods aim at alleviating some of the concerns raised by professionals about the use of AI in clinical settings, but not including these professionals in the validation process could be counterproductive. We presume that including Patient Participation Groups or professional evaluators can add significant complexity or costs to a research project, but future work should be done to identify what factors are actually hindering HCM adoption.

We conclude by emphasising the urgent need for XAI systems that are not only technically sound but also clinically meaningful and ethically grounded. We call for a more rigorous, replicable, and impactful approach in future research, encouraging the community to prioritise transparency, usability, and stakeholder engagement in the development of next-generation XAI tools.

Author Contributions

Original draft preparation, Methodology: H.E.; Validation: F.T.; Review and Editing: F.C.; Supervision: B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xu, H.; Shuttleworth, K.M.J. Medical artificial intelligence and the black box problem: A view based on the ethical principle of “do no harm”. Intell. Med. 2024, 4, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, D.; Wang, H.X.; Li, Y.F.; Nguyen, T.N. Explainable artificial intelligence: A comprehensive review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 3503–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauzier, J.; Rock, N.; Kelly, P.; Pons, A.; Andre, A.; Urwin, L. Navigating AI Liability Risks. 2024. Available online: https://www.dlapiperoutsourcing.com/blog/tle/2024/navigating-ai-liability-risks.html (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Jones, C.; Thornton, J.; Wyatt, J.C. Artificial intelligence and clinical decision support: Clinicians’ perspectives on trust, trustworthiness, and liability. Med. Law Rev. 2023, 31, 501–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, J.M.; Jongsma, K.R. Who is afraid of black box algorithms? On the epistemological and ethical basis of trust in medical AI. J. Med. Ethics 2021, 47, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. Ethics and discrimination in artificial intelligence-enabled recruitment practices. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy-Stang, Z.; Davies, J. Human biases and remedies in AI safety and alignment contexts. AI Ethics 2025, 5, 4891–4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, C.I.; Shuib, L. The role of explainability and transparency in fostering trust in AI healthcare systems: A systematic literature review, open issues and potential solutions. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 1999–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Mehta, M.A. An Overview of Explainable AI Methods, Forms and Frameworks. In Explainable AI: Foundations, Methodologies and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, C.; Ley, D.; Krishna, S.; Saxena, E.; Pawelczyk, M.; Johnson, N.; Puri, I.; Zitnik, M.; Lakkaraju, H. OpenXAI: Towards a Transparent Evaluation of Model Explanations. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.11104. [Google Scholar]

- Salih, A.; Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; Boscolo Galazzo, I.; Radeva, P.; Petersen, S.E.; Menegaz, G.; Lekadir, K. A Perspective on Explainable Artificial Intelligence Methods: SHAP and LIME. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.02012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning, 3rd ed.; Leanpub: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Olah, C.; Satyanarayan, A.; Johnson, I.; Carter, S.; Schubert, L.; Ye, K.; Mordvintsev, A. The Building Blocks of Interpretability. Distill 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devireddy, K. A Comparative Study of Explainable AI Methods: Model-Agnostic vs. Model-Specific Approaches. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Hasan, K.; Hossain, M.S. XAI-Empowered MRI Analysis for Consumer Electronic Health. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 71, 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kares, F.; Speith, T.; Zhang, H.; Langer, M. What Makes for a Good Saliency Map? Comparing Strategies for Evaluating Saliency Maps in Explainable AI (XAI). arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Sarkar, A.; Howlader, P.; Balasubramanian, V.N. Grad-CAM++: Generalized Gradient-based Visual Explanations for Deep Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.11063. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P.T.; Zhang, C.B.; Hou, Q.; Cheng, M.M.; Wei, Y. LayerCAM: Exploring Hierarchical Class Activation Maps for Localization. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 5875–5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepiolo, D.; Ligeza, A. Towards Explainability of Tree-Based Ensemble Models: A Critical Overview. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 484, pp. 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Why Should I Trust You? Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 4–9 December 2017; NIPS’17. pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Covert, I.C.; Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. Algorithms to estimate Shapley value feature attributions. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothinti, R.R. Fusion of Multi-Modal Deep Learning and Explainable AI for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Stratification. Int. J. Nov. Res. Dev. (IJNRD) 2023, 8, 136–144. [Google Scholar]