Abstract

Apple leaf diseases can significantly affect the yield and quality of apple crops. However, conventional manual detection methods are inefficient and highly susceptible to subjective judgment, rendering them inadequate for large-scale agricultural production. To address these limitations, this study proposes Mobile-CBSD, a lightweight deep learning model for apple leaf disease detection based on an enhanced version of YOLOv11. First, the original backbone network of YOLOv11 is replaced with MV4_CBAM, a lightweight architecture that improves feature representation capability while reducing model size. Second, the SE attention mechanism is redesigned and integrated into the network to strengthen multi-scale feature fusion. Furthermore, the traditional CIoU loss function is replaced with SIoU to accelerate convergence and enhance localization precision. Experimental results demonstrate that, while maintaining model compactness, Mobile-CBSD achieves an mAP@0.5 of 90.89%, representing a 2.16% improvement over the baseline, along with a 1.02% increase in overall precision. The model size is reduced from 5.4 MB to 4.8 MB. These findings indicate that Mobile-CBSD achieves an effective balance among accuracy, inference speed, and deployability, offering a practical and scalable solution for the efficient monitoring of apple leaf diseases.

1. Introduction

Apple is a globally significant fruit, ranking third in terms of total area and yield, only behind bananas (including plantains) and citrus fruits. According to statistics, apples are produced in 93 countries and regions worldwide, with over 80 of these having established large-scale apple production. In terms of cultivation area and yield, China has consistently held the leading position, contributing an average annual share of 50.98% to the global apple production [1]. The apple farming sector plays a significant role in the development of China’s agricultural economy.

Apple yield is determined by various factors, like climate, soil quality, irrigation, and diseases. During the growth process, apples are susceptible to numerous types of leaf diseases, each with distinct causes. The main characteristic of apple leaf diseases is their diversity, with symptoms often appearing similar, which poses a significant challenge to visual differentiation. As a result, farmers are unable to take timely and appropriate measures, leading to a decline in apple yield [2].

Current manual detection of apple leaf disease lesions requires significant human resources. However, this approach is prone to subjective bias based on the experience of the inspectors and is also affected by fatigue, leading to decreased efficiency. As a result, manual detection suffers from low efficiency and relatively low accuracy. Recently, deep learning has become increasingly prevalent in various intelligent agricultural devices, making the automatic identification of apple leaf diseases through the integration of deep learning and machine vision. Deep learning-based detectors demonstrate a substantial advantage over conventional techniques in key performance metrics, notably in the efficiency and accuracy of identifying apple leaf disease lesions, reduce labor costs, and are well-suited for large-scale agricultural production [3].

Numerous scholars have proposed methods for detecting and identifying apple leaf diseases through deep learning technologies. Wang et al. [4] employed ResNet50 to allocate weights to different feature channels, integrated Feature Pyramid Networks (FPN) to fuse multi-level features, and modified Faster R-CNN into Cascade R-CNN with a cascading mechanism. This method sampled positive and negative examples at different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds to generate high-quality prediction boxes, thereby improving classification and regression accuracy. Wang et al. [5] focused on obtaining semantic and spatial information from multiple levels and combined the EfficientNet-B0 classification network with DenseNet121. They also introduced a focal loss function combined with label smoothing to enhance the model’s attention to apple leaf images with difficult classification decision boundaries. Ding et al. [6] suggested two schemes combining ResNet18 for apple leaf disease classification, one incorporating the CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) and the other with a random cropping branch. The accuracy of these models reached 95.2% and 97.2%, respectively, demonstrating improved classification accuracy for apple leaf diseases. To balance model compactness and performance, Gong and Zhang [7] used ShuffleNetV2 as the backbone of YOLOv5s and incorporated the CBAM module to enhance feature representation. They introduced the RFB-s module in the small-scale branch to increase the network’s receptive field and strengthen the model’s capability to identify small-scale lesions. The SIoU loss function was used to measure the regression loss of the predicted boxes, enhancing inference accuracy. Liu et al. [8] enhanced the Inception ResNetV2 model by integrating the CBAM module for refined feature extraction and applying focal loss to mitigate class imbalance in the apple leaf disease dataset, and performed model ensemble using snapshot ensemble methods to obtain a model for apple leaf disease severity recognition. Wang et al. [9] presented an improvement to the YOLOv5 network model by integrating Ghost modules, mobile inverted residual bottlenecks, and a CBAM attention mechanism These enhancements culminated in the MGA-YOLO network, a mobile-deployable system capable of real-time apple leaf disease diagnosis.

Although existing networks and algorithms have improved the efficiency of automatic apple leaf disease detection to a certain extent, several critical bottlenecks remain. Most studies have been conducted under simplified or controlled background conditions, which limits their generalization ability in complex and realistic field environments. Image classification-based approaches may fail to detect diseases when lesions are small or visually indistinct. Furthermore, a significant challenge lies in achieving effective model compression without compromising detection performance.

In this study, we propose a lightweight Mobile-CBSD model based on an improved YOLOv11 [10]. The model is designed to detect common and economically significant apple leaf diseases—Apple Scab, Apple Rust, Gray Spot, and Powdery Mildew—with Healthy leaves included as a control category. The original YOLOv11 backbone network is replaced with the more efficient MobileNetV4 architecture, while preserving key components such as the Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fusion (SPPF) layer and C2PSA module to maintain robust feature representation. To enhance feature discrimination, the CBAM attention module is integrated into the backbone network to improve channel-spatial feature recalibration. Additionally, the SE-DCCS attention mechanism is introduced at the final stage of the neck network to strengthen multi-scale feature fusion, particularly for detecting small disease spots. Moreover, the CIoU loss function is replaced with the SIoU loss function to improve the stability and convergence speed of bounding box regression. The proposed framework aims to achieve an optimal balance between model compactness and detection accuracy, enabling fast and reliable apple leaf disease detection suitable for real-world agricultural deployment.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- We propose the MV4_CBAM backbone network by replacing the original YOLOv11 backbone with a lightweight MobileNetV4 architecture and integrating the CBAM attention mechanism after the SPPF layer. This design enables more effective weight allocation across spatial and channel dimensions, thereby enhancing feature representation and improving model detection accuracy.

- (2)

- We introduce a modified SE attention mechanism that incorporates dilated convolution and channel shuffle to expand the receptive field, improve contextual information capture, enhance inter-channel feature interaction, increase feature utilization efficiency, and facilitate multi-scale feature fusion—particularly for the detection of small lesions.

- (3)

- The CIoU loss function is replaced with the SIoU loss function to improve localization accuracy and training stability while accelerating convergence during model training. Extensive experimental evaluations were conducted, and the results demonstrate that the proposed model outperforms multiple state-of-the-art baseline models in terms of detection accuracy, inference speed, and model compactness.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

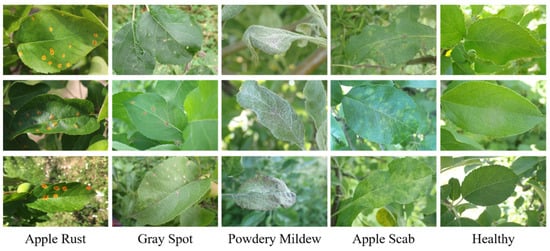

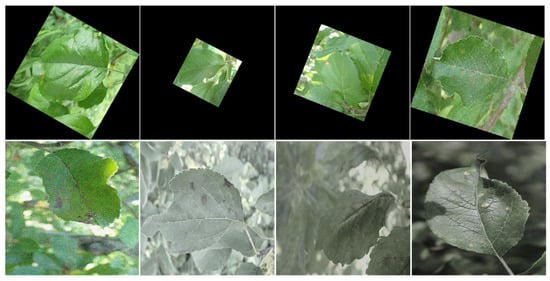

To assess the model’s efficacy and generalization, we utilized apple leaf images from the publicly available FGVC8 dataset presented at CVPR 2021 FGVC8 Plant Pathology Recognition Challenge public dataset [11]. The images in this dataset were captured in natural scenes, making them more realistic and complex compared to single-background images typically collected in laboratory or synthetic environments. This diversity aids the model to assimilate a richer feature set, consequently strengthening its generalization capacity. The experimental dataset comprised 4848 images encompassing five distinct categories: 973 images of Powdery Mildew, 950 images of Apple Scab, 943 images of Apple Rust, 989 images of Gray Spot, and 993 Healthy images (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sample dataset.

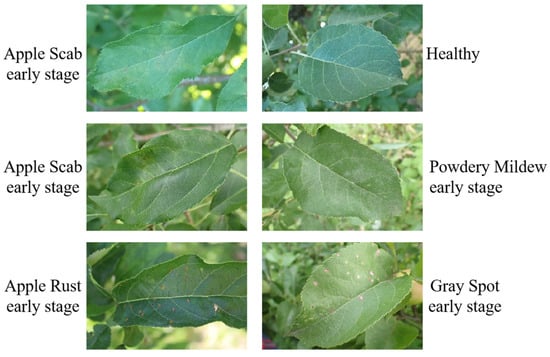

Throughout the image selection and organization, the following characteristics of apple leaf diseases were observed: In the early stages of Apple Scab, the symptoms and coloration closely resemble those of healthy leaves, making it difficult to distinguish them with the naked eye. Both Apple Scab and Powdery Mildew initially manifest at specific locations on the leaf, with the disease gradually spreading across the entire leaf as it progresses. Apple Rust and Gray Spot both feature small lesions with similar initial coloration, posing significant challenges for fine-grained localization (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of data features.

Compared to similar experiments, the dataset used in this study is sufficiently large and diverse. Additionally, the YOLOv11 model inherently performs Mosaic data augmentation on the dataset. Therefore, no further data augmentation is applied during the preprocessing phase. To facilitate feature learning, disease lesions on apple leaves were annotated using LabelImg v1.8.6. The dataset was subsequently partitioned into training and validation sets following an 80:20 ratio.

2.2. Experimental Setup and Parameter Configuration

The operating system used in this experiment was Ubuntu 20.04, with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) featuring 24 GB of memory. The implementation leveraged PyTorch 1.12.1 with CUDA 11.3 as the deep learning framework, alongside Python 3.9 as the programming language.

The Hyper-parameter settings during the experiment are shown below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hyper-parameter settings.

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

A comprehensive evaluation of the proposed model’s lightweight character and practical feasibility employs multiple metrics: Precision (P), Recall (R), mean Average Precision (mAP), parameter count, Giga floating-point operations per second (GFLOPs), and model size. The relevant formulas are provided below.

Formula for Precision (P):

Formula for Precision (R):

Formula for Precision (mAP):

In the formula, TP denotes True Positive, referring to a correct prediction where positive samples are classified as positive; FP denotes False Positive, indicating an incorrect detection in which negative samples are classified as positive; FN denotes False Negative, representing the misclassification of positive samples as negative. For the five categories (n = 5) in this research, AP represents the area under the PR curve, and mAP@0.5 is the weighted average of AP values over all classes evaluated at a 0.5 IoU threshold.

2.4. Lightweight YOLOv11-Based Mobile-CBSD Model

YOLOv11 [10] represents a single-stage detection framework originating from the Ultralytics team. Unlike two-stage algorithms, the single-stage approach directly performs feature extraction and predicts both the object classification and its location, providing a significant advantage in detection speed. This enables real-time and fast target detection. YOLO-based models have consistently demonstrated competitive performance in detection tasks due to their outstanding speed and accuracy.

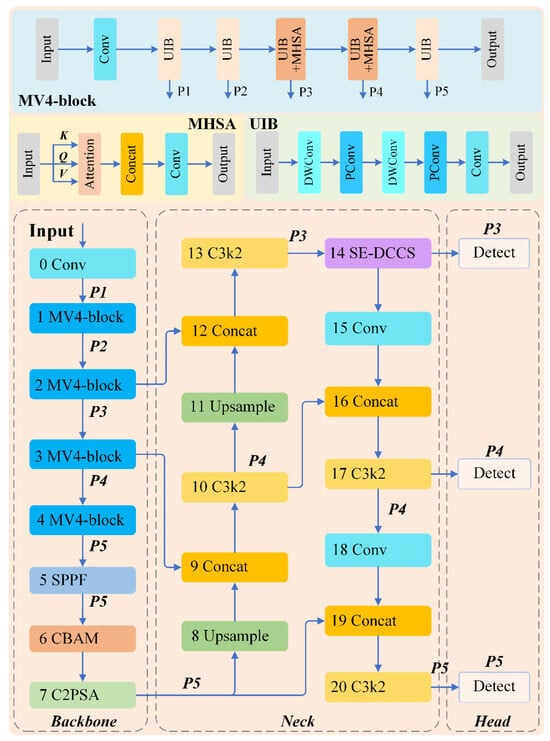

The architecture of YOLOv11 four fundamental components: Input, Backbone, Neck, and Head networks. The input module is responsible for receiving raw image data and applying Mosaic augmentation to enhance the data, thus improving the model’s generalization ability. The backbone network integrates C3K2 and C2PSA modules, which strengthen feature extraction. The neck module employs a PAN architecture for effective multi-scale feature integration. Within the head architecture, depth-separable convolutions are utilized in the CLS branch, reducing redundant computations and improving computational efficiency.

By comparing YOLOv11 with other models in the YOLO series, it is apparent that the Ultralytics team has focused on making the model lightweight. However, it still does not fully meet the requirements for end-to-end deployment in practical application scenarios. Therefore, this study aims to further optimize the related structures in YOLOv11 to attain enhanced recognition precision, improved operational responsiveness, and a more flexible, lightweight network architecture.

2.4.1. Improvement Strategy

The Mobile-CBSD model is an enhancement of YOLOv11, where the backbone network of YOLOv11 is replaced with MobileNetV4 [12]. The design concept behind MobileNetV4 aims to create a more lightweight network while preserving precision detection. The core innovation of MobileNetV4 lies in the introduction of the Universal Inverted Bottleneck (UIB) module, which is particularly adapted for optimized network design. The framework demonstrates versatility across multiple optimization criteria and achieves an optimal balance between spatial and channel feature interactions, effectively enlarging the perceptual domain while ensuring maximal operational efficiency.

Following the SPPF layer in the backbone network, a CBAM attention mechanism [13] is inserted. This combination improves the model’s ability to express features and enhances decision accuracy. The SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation) attention mechanism [14] is redesigned by using dilated convolutions and channel shuffling to capture more contextual information and improve feature utilization efficiency. Finally, the CIoU loss function is substituted with its SIoU counterpart, accelerating the convergence of training and enhancing the model’s predictive capability. Figure 3 provides a schematic overview of the Mobile-CBSD network architecture.

Figure 3.

The architecture of Mobile-CBSD.

2.4.2. Lightweight MV4_CBAM Backbone

In the YOLOv11 C3K2 architecture, although the use of concatenated bottleneck structures has been reduced, a significant computational burden still remains, resulting in excessive redundancy in channel information. To address this, many networks have adopted various methods for lightweight design. For example, MobileNetV1 [15] utilizes depthwise separable convolutions to improve efficiency, GhostNet [16] increases depthwise convolutions’ relative frequency, and MobileNetV2 [17] introduces linear bottlenecks and inverted residuals to enhance memory efficiency.

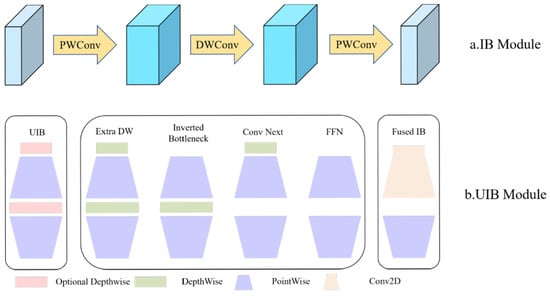

Our architectural configuration employs MobileNetV4 as the foundational feature extractor, replacing the original backbone network of YOLOv11. MobileNetV4 inherits the Inverted Bottleneck (IB) module from MobileNetV2, which is further expanded into the Universal Inverted Bottleneck (UIB) module.

As shown in Figure 4a, the IB module first uses pointwise (PW) convolution for dimension expansion, followed by depthwise (DW) convolution, which performs convolutions in a higher-dimensional space to extract features. Finally, PW convolution is applied again to reduce the dimensionality, thereby compressing the data and achieving a more compact network. As shown in Figure 4b, the UIB module unifies the existing IB module, ConvNext-like module, and the FeedForward Network (FFN) from Vision Transformers (ViT). It incorporates an optional depthwise separable convolutional operation during the pre-expansion phase and allows the DW convolution between the expansion and projection layers to be optional. Furthermore, UIB presents an innovative architectural variation: the Extra Depthwise Separable IB (ExtraDW) module. The ExtraDW module increases architectural complexity and perceptual scope with minimal computational cost, combining the advantages of both ConvNext-like and IB structures. At each stage of feature extraction, UIB can adaptively modulate the perceptual range and balance the trade-off between spatial mixing and channel mixing, thereby maximizing computational efficiency.

Figure 4.

IB module and UIB module.

In real-world environments, the background of apple leaves is often complex, and small target lesions, such as those caused by Apple Rust and Gray Spot, typically appear in clustered formations. To minimize complex background feature interference and to enhance feature extraction capabilities, the CBAM attention mechanism architecturally integrated following the final SPPF layer of the backbone network. This mechanism suppresses non-essential areas, such as the background, while amplifying the network’s capacity for discerning feature saliency.

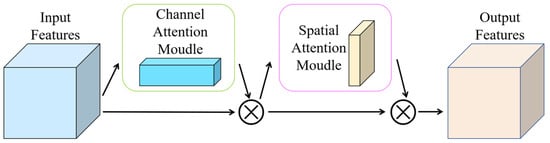

The CBAM attention mechanism comprises a channel attention module and a spatial attention module, as illustrated in Figure 5. The channel attention module enables the model to automatically learn inter-channel dependencies within the feature map and dynamically adjust the significance of each channel, thereby improving model performance and generalization capability. The spatial attention module allows the model to selectively focus on informative spatial regions during image processing, thus facilitating the extraction of critical visual features. By integrating these two modules, the model achieves more meaningful weight allocation across both channel and spatial dimensions. As a result, detection accuracy and model robustness are enhanced, computational efficiency is optimized, parameter overhead is reduced, and overall feature representation capability is significantly improved [18].

Figure 5.

CBAM attention mechanism.

2.4.3. SE-DCCS Attention Mechanism

Attention mechanisms have been widely adopted and have yielded significant results. The inspiration behind this mechanism originates from the human visual system, which selectively focuses on important aspects of an image while disregarding irrelevant information. By incorporating the attention mechanism, neural networks can more efficiently allocate their limited computational resources, focusing on capturing the most critical image features, ultimately enhancing detection performance.

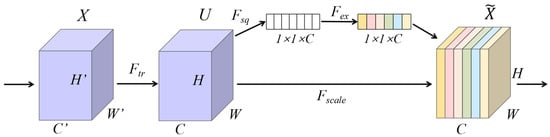

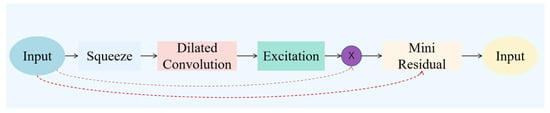

To accommodate the substantial scale variation present in apple leaf pathological regions, the SE attention mechanism was introduced and redesigned within the Mobile-CBSD model. The SE module dynamically adjusts the features across channels, recalibrating and enhancing representational capability (Figure 6). This mechanism improves the sensitivity and accuracy in feature extraction, effectively mitigating the issue of missed detection due to inconsistent lesion sizes on apple leaves.

Figure 6.

SE attention mechanism.

The SE module operates by automatically learning and incorporating an attention mechanism along the channel dimension, assigning adaptive weights to each feature map. This allows the network to emphasize more informative channels and capture salient features, thereby enhancing model accuracy. The SE mechanism comprises two key stages: Squeeze and Excitation. In the first stage, the squeeze operation applies global average pooling to compress the input feature map of size W × H × C into a channel-wise descriptor—a global feature vector z of dimension 1 × 1 × C—effectively aggregating spatial information and capturing global context for subsequent weight computation [19].

In Figure 6, X denotes the input data, represents the convolution operator, U signifies the weighted feature map, refers to the transformation result, and H, W, and C denote the height, width, and number of channels of the spatial dimensions, respectively.

The formula for the squeeze operation is as follows:

Upon obtaining the global feature vector, an excitation operation is applied to model the inter-channel dependencies by adaptively enhancing informative features and suppressing less relevant ones. The mathematical formulation of this operation is as follows:

In the formulation, denotes the sigmoid activation function, denotes the ReLU activation function, refers to the compressed real-valued outputs, represents the parameters for dimensionality reduction, and represents the parameters for dimensionality expansion.

Finally, the weights produced by the excitation operation are applied to the features of each channel through element-wise multiplication, where each channel is scaled by its corresponding weight coefficient, thereby recalibrating the original feature representation. The mathematical formulation is as follows:

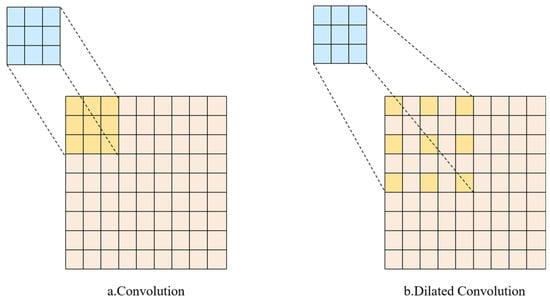

The SE attention mechanism utilizes global average pooling for feature aggregation from the entire feature map. Although global average pooling introduces some degree of translation invariance, it can also distort spatial information in the image and may cause the loss of important local features. To address this issue, dilated convolution [20] is incorporated after the Squeeze operation. Group convolutions within the dilated convolution allow for an effective expansion of the receptive field, enhancing contextual comprehension, while simultaneously minimizing model parameters and enhancing computational efficiency. Figure 7a shows a standard convolution operation, where there is no gap between the kernel elements. To enhance the receptive field, either the kernel size must be increased or additional convolution layers need to be stacked, leading to a dual escalation of parameter quantity and computational requirements., thereby reducing model efficiency. Figure 7b illustrates the dilated convolution, where gaps are introduced between adjacent kernel elements, with a position difference of 2 between adjacent elements, as shown in the convolution kernel above.

Figure 7.

Convolution and dilated convolution.

Let k represent the size of the original convolutional kernel, k′ is the size of the dilated convolutional kernel, and r is the dilation factor. The relationship can be formulated as:

Then, the receptive field of the i-th layer can be expressed as , the receptive field of the (i − 1)-th layer as , and the stride as stride. The relationship can be formulated as:

It is evident that the receptive field increases with the use of dilated convolution. In conventional convolutions, after stacking multiple layers, the feature map resolution typically decreases due to pooling operations or the increased size of convolutional kernels, leading to image details loss. In contrast, dilated convolution expands the receptive field and preserves the resolution of the feature map, which is important in detection frameworks that require the retention of image detail information.

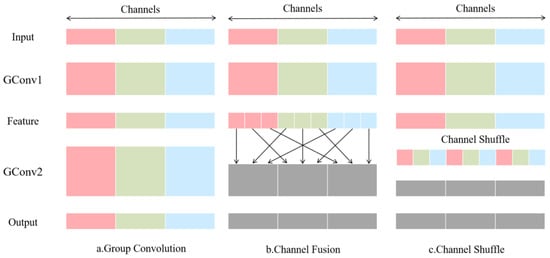

Moreover, to prevent the SE module from focusing excessively on specific channels while neglecting other equally important feature information, which could degrade model’s generalization ability, a Channel Shuffle module is introduced after the Excitation operation. This module enhances inter-channel communication, thereby improving feature utilization efficiency. The Channel Shuffle operation, proposed by ShuffleNet [21], separates the input feature map into distinct groups and rearranges the channel order, facilitating information flow and integration across different channels. Figure 8a illustrates the conventional two-group convolution operation, which hampers the flow of information. However, by using channel information between feature maps as shown in Figure 8b, the output features can incorporate information from each group, as demonstrated in the Channel Shuffle implementation shown in Figure 8c.

Figure 8.

Group convolution, channel fusion, channel shuffle.

This operation enhances the cross-channel communication of features, enhancing the model’s capacity to assimilate and utilize the correlations between different channels. Through Channel Shuffle, the model develops a more profound comprehension of the input data, thereby strengthening its generalization ability. Finally, small residual blocks are added before the output, introducing skip connections that allow the input layer to directly pass through to the main path, thus reducing the risk of gradient vanishing, enhancing feature reusability, and further optimizing the features. The resulting SE-DCCS attention mechanism is illustrated below (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

SE-DCCS attention mechanism.

2.4.4. SIoU Loss Function

As a pivotal element in model optimization, the loss function aligns predicted values with the actual results, providing a clear direction for model optimization. It serves as a tool to quantify prediction errors. During the training process, the loss function evaluates the discrepancy between the predicted and actual values, known as the loss value. A smaller loss value indicates higher prediction accuracy and better model performance. The goal is to minimize the loss function; the smaller the loss, the higher the model’s robustness.

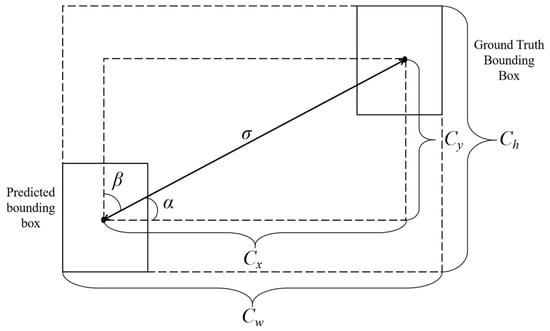

In YOLOv11, the boundary box regression loss uses CIoU, which accounts for the spatial relationship between the predicted and ground truth boxes, the aspect ratio consistency, and the overlap area. Nevertheless, CIoU fails to consider the misalignment between predicted and ground-truth bounding boxes. In contrast, SIoU [22] further incorporates the vector angle between the predicted and true boxes, thereby improving the anchor’s localization precision and optimizing the convergence efficiency in low-overlap scenarios.

As shown in Figure 10, SIoU considers four components: angle loss, distance loss, shape loss, and IoU loss. This improvement makes the loss function more aligned with the diversity of real-world targets.

Figure 10.

The computational diagram of the SIoU loss function.

The angle loss considers the spatial orientation relationship between bounding box centroids. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formulation, represents the Euclidean distance between the center point of the predicted bounding box and that of the ground truth box, while denotes the difference in height between the two center points.

The distance loss derives from the relative distance between the center points of the boundary boxes and is used to calculate the distance cost. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formulation, , and denote the square of the ratio of to , while represents the square of the ratio of to . Under the influence of angular loss, the closer the predicted bounding box is to being aligned horizontally with the ground truth box, the smaller the contribution of the distance loss becomes. Conversely, when the angle between the center points approaches 45°, the contribution of the distance loss increases.

The shape loss is responsible for considering the disparity in aspect ratios between the predicted and ground-truth boundary boxes. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formulation, denotes the ratio of the absolute width difference between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth box to the maximum value, denotes the ratio of the absolute height difference between the two boxes to the maximum value, and represents the weighting coefficient for the shape loss [23].

The final form of the SIoU loss function is expressed as follows:

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Ablation Study

3.1.1. Ablation Study of the Improved Network

In this experiment, the original backbone network of YOLOv11 was replaced with MobileNetV4 to achieve a lightweight network. Additionally, the CBAM attention mechanism was integrated after the SPPF layer to enhance the model’s feature extraction ability. Furthermore, the SE-DCCS attention mechanism was inserted at the end of the neck network to enhance feature integration. Finally, the CIoU loss function was substituted with the SIoU optimized variant to accelerate the model’s convergence.

To specifically evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of the MV4_CBAM lightweight backbone, SE-DCCS attention mechanism, and SIoU loss function, ablation experiments were conducted for each of the individual modules. Our results are presented below (Table 2), where “√” denotes the inclusion of the respective module.

Table 2.

Ablation test.

Firstly, YOLOv11 was used as the baseline network. Subsequently, the efficacy of the enhanced components was evaluated against reference architecture. Experimental results show that the addition of each individual module resulted in varying degrees of improvement regarding average precision and accuracy when in comparison with the baseline model. Some modules also contributed to slight increases in the recall rate.

The substitution of the default backbone with the MV4_CBAM architecture led to a decrease in the model’s parameter size by 0.4 MB, a reduction in computational complexity by 0.9 GFLOPs, as well as a decrease in model size by 0.6 MB compared to the original YOLOv11 (Table 2). While the recall rate decreased slightly, mAP@0.5 improved by 1.16% points, and accuracy increased by 3.01% points. These results suggest that the model’s feature extraction capacity was significantly enhanced while achieving a lightweight design.

Incorporating the SE-DCCS attention mechanism into the YOLOv11 network resulted in increased mAP@0.5 and accuracy, demonstrating that the attention mechanism benefits the neck network’s ability to fuse apple leaf disease features, thereby improving the model’s detection precision.

By replacing the CIoU loss function with the SIoU loss function based on YOLOv11, the mAP@0.5 increased by 0.89% points, and accuracy improved by 2.91% points. These results demonstrate that the modified loss function enables the model achieves precise localization and reliable target identification, accelerates model convergence, and ultimately enhances the overall performance.

Further, by incorporating the SE-DCCS attention mechanism and the SIoU loss function into the improved MV4_CBAM backbone, both mAP@0.5 and accuracy showed improvement. Additionally, the recall rate increased after the insertion of the SIoU loss function. Furthermore, the parameters and computational complexity of the model are both decreased.

In summary, by incorporating the MV4_CBAM backbone, the SE-DCCS attention mechanism, and the SIoU loss function into YOLOv11, the refined model achieved notable advancement in functional performance. The mAP@0.5 increased by 2.16% points, accuracy rose by 1.02% points, and recall improved by 0.86% points. Additionally, the model’s parameter count decreased by 0.39 MB, computational complexity was decreased by 0.9 G, and the model size decreased by 0.6 MB. These results demonstrate that the improved Mobile-CBSD model successfully achieved the goal of network lightweighting, while also enhancing both detection accuracy and efficiency.

3.1.2. Ablation Study of Different Attention Mechanisms

To verify the efficacy of the SE-DCCS attention module during the instructional process, various attention mechanisms, including the ECA attention mechanism, SAM attention mechanism, SE attention mechanism, and the improved SE-DCCS attention mechanism, were sequentially inserted into the neck feature fusion network of the original YOLOv11.

Our results indicated that mAP value of the original SE attention mechanism is higher than that of the ECA and SAM attention mechanisms (Table 3). Therefore, this study chose to improve the SE mechanism by incorporating dilated convolution and channel shuffling. The results indicate that the improved SE-DCCS attention mechanism significantly outperforms the others in terms of accuracy, recall, and mAP.

Table 3.

Ablation test of different attention mechanisms.

3.2. Comparison Experiment

To verify the superiority of the Mobile-CBSD model, which is based on YOLOv11, compared to other models, the dataset compiled in this study was input into YOLOv11, YOLOv9t [24], YOLOv10n [25], CenterNet [26], SSD [27], and Faster R-CNN [28] models for comparison experiments, with all training parameters held constant.

Our results reveal that the proposed Mobile-CBSD model outperforms YOLOv11, YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n, CenterNet, SSD, and Faster R-CNN by mAP improvements of 2.16%, 4.09%, 4.39%, 3.3%, 13.19%, and 51.17% points, respectively (Table 4). Compared to the more accurate CenterNet model, the Mobile-CBSD model reduces computational load by 67.8 GB and parameter count by 122.37 MB. Therefore, the Mobile-CBSD model demonstrates considerable superiority in apple leaf diseases recognition, improving detection accuracy and achieving model lightweighting.

Table 4.

Comparative test of different network models.

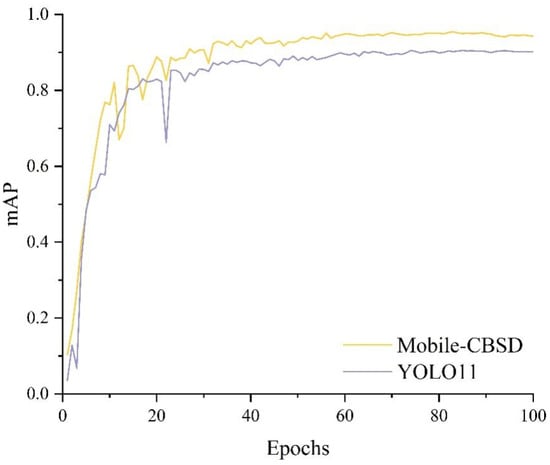

A comparison was conducted between the improved Mobile-CBSD model and the original YOLOv11 model. Except for the modifications introduced in this study, other hyperparameters were set according to Table 1. As illustrated in Figure 11, the improved network achieves a higher mAP@0.5 with the same number of iterations.

Figure 11.

Comparison of mAP values before and after improvement.

3.3. Per-Class Performance Evaluation

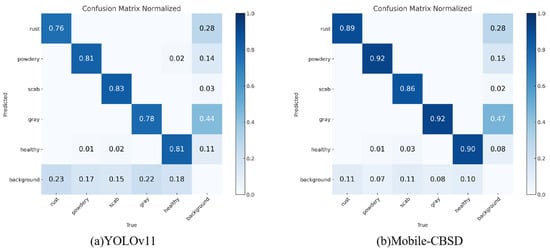

The confusion matrix is a valuable tool for evaluating the performance of a classification algorithm. Each row corresponds to the actual class, while each column represents the class predicted by the model. The elements along the main diagonal indicate the number of correctly classified instances, referred to as True Positives (TP). The lower left triangular region reflects the count of False Negatives (FN), representing cases in which the model failed to detect actual positive instances, resulting in undetected targets or misclassification into other categories. Conversely, the upper right triangular region captures the number of False Positives (FP), where the model incorrectly assigns background or irrelevant instances to the target class. Elevated values in the upper right portion suggest a tendency toward over-prediction, indicating that the model frequently misclassifies non-target instances as positive. In contrast, high values in the lower left portion imply a higher rate of under-detection, revealing difficulties in recognizing actual instances of the corresponding classes.

Figure 12 presents the normalized confusion matrices of the model before and after enhancement, with values scaled between 0 and 1 [29]. As illustrated in the figure, the overall performance of the improved Mobile-CBSD model has been enhanced compared to the baseline YOLOv11. Notably, Mobile-CBSD demonstrates significant improvements across most disease categories. In particular, detection accuracy shows marked gains in Apple Rust, Powdery Mildew, and Gray Spot, achieving accuracy rates of 89%, 92%, and 92%, respectively. The accuracy for the Healthy class has also increased from 81% to 90%, indicating that the optimized model is more effective at distinguishing healthy leaves from diseased ones. These results suggest that the model enhancements have led to improved classification precision across diverse disease categories. However, as shown in Table 5, the AP value for Apple Scab slightly decreased from 92.06 to 90.23. Although this decline is marginal, it suggests potential limitations in the model’s ability to maintain performance on this specific class. Nevertheless, the confusion matrix analysis confirms that the overall performance improvement underscores the effectiveness of the proposed optimization strategy and the model’s enhanced detection capability for the majority of apple leaf diseases.

Figure 12.

Comparison of confusion matrices of YOLOv11 and Mobile-CBSD on the test set.

Table 5.

Per-class detection performance comparison between YOLOv11 and Mobile-CBSD.

3.4. Generalization Performance Evaluation

To evaluate the adaptability and generalization capability of the improved model in complex environments, this study conducted a performance assessment on an external dataset. The dataset includes eight categories: Apple leaf mites, Apple litura moth, Black rot, Glomerella leaf spot, Healthy, Mosaic, Rust, Scab. Following data augmentation, the dataset comprises a total of 2389 images, partitioned into training (1913 images), validation (238 images), and test sets (238 images) at an 8:1:1 ratio, as illustrated in Figure 13. Furthermore, to assess model robustness, salt-and-pepper noise was introduced during the inference phase to simulate real-world environmental complexity.

Figure 13.

The external dataset was augmented using methods such as random scaling, random rotation, random saturation, and Gaussian blur.

The experimental results presented in Table 6 demonstrate that the enhanced Mobile-CBSD model significantly outperforms the baseline YOLOv11 on the external dataset. Specifically, Mobile-CBSD achieves a mAP@0.5 of 76.5%, representing a substantial improvement over YOLOv11’s 66.21%. In addition, both precision and recall are improved, with precision increasing from 73.35% to 86.68% and recall rising from 60.13% to 68.17%, indicating higher detection accuracy and enhanced ability to identify positive instances.

Table 6.

Generalization performance comparison of YOLOv11 and Mobile-CBSD on the external dataset.

In summary, the proposed Mobile-CBSD model exhibits superior detection accuracy and stronger recognition performance for positive samples compared to the baseline. It also demonstrates significant improvements in generalization capability and robustness, confirming its effectiveness in practical agricultural applications.

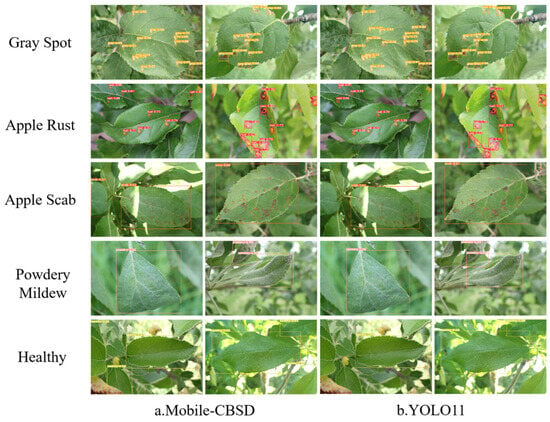

3.5. Instance Detection

To comprehensively evaluate the enhanced Mobile-CBSD framework’s detection capabilities, target detection was performed on five groups of apple leaf diseases using both YOLOv11 and Mobile-CBSD. The comparison results, as shown in Figure 14, implied that the original YOLOv11 model generally demonstrated inferior detection precision accompanied by occasional omission errors. By comparison, the enhanced Mobile-CBSD model achieved superior detection performance for each type of disease. This suggests that the proposed Mobile-CBSD model can more accurately detect various diseases, further confirming its effectiveness and feasibility in improving detection performance.

Figure 14.

Comparison of YOLOv11 results before and after improvement.

4. Discussion

This work presents the Mobile-CBSD model, which integrates several effective modules into the YOLOv11 architecture. The model achieves an optimal equilibrium between architectural efficiency and perceptual precision for apple leaf disease detection, demonstrating strong practical applicability. Existing approaches like SSD [30] and Faster R-CNN [31] have achieved competitive results across various domains; however, these methods typically face deployment bottlenecks due to their extensive parameterization and processing requirements in constrained environments. As a result, lightweight object detection has become a major research focus. Representative models such as YOLOv11 and YOLOv8 have introduced several improvements to enhance computational efficiency and detection accuracy, yet they still exhibit certain limitations [32].

The core contribution of this research is the design of the MV4_CBAM backbone network. The apple leaf disease dataset contains numerous images of diverse disease types, which generally require substantial computational resources, particularly for real-time monitoring. To address this challenge, the MobileNetV4 network employs depthwise separable convolutions to reduce computational overhead and model parameters. Moreover, MobileNetV4 enhances feature extraction by introducing convolution kernels of varying sizes, improving performance under resource-limited conditions—a benefit that becomes especially evident when processing complex datasets [33]. The model is trained on an apple disease dataset featuring naturally complex backgrounds where the contrast between lesions and surrounding foliage is often low. For instance, early-stage lesions of diseases such as black spot and powdery mildew exhibit subtle differences from healthy tissues. The CBAM attention mechanism addresses this issue by integrating channels and spatial attention to emphasizing lesion features while attenuating background noise, consequently elevating recognition precision [13].

To optimize recognition performance while preserving compact architecture, this study also refines the SE attention mechanism in two key ways. First, dilated convolutions are incorporated into the SE module to expand the receptive field without increasing computational cost, facilitating the acquisition of extended contextual awareness and preserve fine-grained local features—an essential capability for detecting small lesions [34]. Second, a channel shuffle module is integrated to facilitate information exchange among channels, preventing the SE mechanism from overemphasizing specific channels and enhancing inter-channel interactions. This improvement strengthens the network’s feature representation, thereby boosting generalization, detection accuracy, and resilience characteristics within the apple leaf disease dataset [35]. Additionally, the SIoU loss function is utilized to accelerate model convergence and enhance bounding-box regression. By addressing the small size and irregular shapes of apple leaf lesions, SIoU reduces detection errors, consequently improving operational effectiveness [36].

Despite these advances, the Mobile-CBSD model has certain limitations. Although the model’s ability to detect diseased leaves has improved, the early symptoms of Apple Scab are often subtle, and the boundary between infected and healthy tissue remains ambiguous. This can lead to misclassification of certain Apple Scab samples as healthy leaves, resulting in an increase in both false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN), thereby reducing the category-specific average precision (AP). In future work, this limitation will be further addressed to enhance the model’s detection accuracy for Apple Scab.

Furthermore, the current dataset remains relatively small and, while it includes multiple disease types, it fails to comprehensively encompass real-world heterogeneity. Forthcoming investigations will concentrate on broadening dataset diversity, including images from different cultivars and environments. Furthermore, integrating edge computing with cloud-based processing offers promising opportunities to improve real-time performance and adaptability. Subsequent research will also explore methods based on knowledge distillation and multimodal data fusion to further increase the model’s accuracy, robustness, and practical deployment potential.

5. Conclusions

The present study introduces Mobile-CBSD, a lightweight framework built upon YOLOv11. By substituting the original backbone with the lightweight MV4_CBAM architecture, these enhancements synergistically improve the model’s operational performance, yielding higher precision and faster processing speeds for apple leaf disease detection. Our results demonstrate that the Mobile-CBSD model exhibits enhanced detection accuracy across above apple leaf diseases types and environmental conditions, effectively addressing practical challenges such as the diversity of disease types and varying image quality. These findings validate its wide applicability in real-world agricultural production, offering a practical tool to support sustainable crop management practices.

Author Contributions

J.X.: Conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision; W.Z.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft; Y.Z.: Data curation; S.B.: Validation, resources; J.L.: Writing—review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development (Competitive Platform) Project [grant numbers 2024CXPT020]; Shandong Province Key R&D Program (Major Science and Technology Innovation) [grant Number (2021LZGC014-3)].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/plant-pathology-2021-fgvc8 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yu, M.; Wen, Y.; Mao, M. The pattern and development trend of China’s apple foreign trade. China Fruits 2002, 225, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Xiao, X.; Liu, Z.; Lu, L. Improved apple leaf disease detection based on YOLOv5s. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2023, 51, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bing, S.; Ji, Y.; Yan, B.; Xu, J. Grading method of fresh cut rose flowers based on improved YOLOv8s. Smart Agric. 2024, 6, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lan, P.; Li, F.; Ge, C.; Sun, F. Apple disease identification using improved Faster R-CNN. J. For. Eng. 2022, 7, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, F.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X. Identifying apple leaf diseases using improved EfficientNet. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2023, 39, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Qiao, Y.; Yang, X.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wang, D.; Liu, H. Improved ResNet based apple leaf diseases identification. IFAC-Pap. 2022, 55, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, S. Lightweight detection of small target diseases in apple leaf using improved YOLOv5s. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2023, 39, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xu, H.; Li, C.; Song, H.; He, D.; Zhang, H. Apple leaf disease identification method based on snapshot ensemble CNN. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J. MGA-YOLO: A lightweight one-stage network for apple leaf disease detection. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 927424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YoLOv11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, R.; Zhang, K.; Snavely, N.; Belongie, S.; Khan, A. Plant Pathology 2021—FGVC8. 2021. Available online: https://kaggle.com/competitions/plant-pathology-2021-fgvc8 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Qin, D.; Leichner, C.; Delakis, M.; Fornoni, M.; Luo, S.; Yang, F.; Wang, W.; Banbury, C.; Ye, C.; Akin, B.; et al. MobileNetV4: Universal models for the mobile ecosystem. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2024: 18th European Conference, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Leonardis, A., Ricci, E., Roth, S., Russakovsky, O., Sattler, T., Varol, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tan, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X. A CBAM based multiscale transformer fusion approach for remote sensing image change detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 6817–6825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Xie, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhao, B.; Chen, Z.; Tan, X. Delving deep into spatial pooling for squeeze-and-excitation networks. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 121, 108159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijwil, M.M.; Doshi, R.; Hiran, K.K.; Unogwu, O.J.; Bala, I. MobileNetV1-based deep learning model for accurate brain tumor classification. Mesopotamian J. Comput. Sci. 2023, 2023, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. GhostNet: More features from cheap operations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Zhou, C.; Ruan, Y.; Li, Y. MobileNetV2 model for image classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Information Technology and Computer Application (ITCA), Guangzhou, China, 18–20 December 2020; pp. 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A.; Ruby, A.U. Evaluating CNN architectures using attention mechanisms: Convolutional Block Attention Module, Squeeze, and Excitation for image classification on CIFAR10 dataset. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.L.; Su, W.H.; Zhang, H.Y.; Peng, Y. SE-YOLOv5x: An optimized model based on transfer learning and visual attention mechanism for identifying and localizing weeds and vegetables. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R. Rethinking dilated convolution for real-time semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 4675–4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gao, Y.; Deng, W. Defect detection using shuffle Net-CA-SSD lightweight network for turbine blades in IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 32804–32812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorgyan, Z. SIoU loss: More powerful learning for bounding box regression. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zheng, K.; Shi, P.; Mei, Y.; Li, H.; Qiu, T. Traffic sign detection based on the improved YOLOv5. Appl Sci. 2023, 13, 9748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Mark Liao, H.Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Computer Vision—ECCV 2024, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Leonardis, A., Ricci, E., Roth, S., Russakovsky, O., Sattler, T., Varol, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J. YoLOv10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; pp. 107984–108011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Gong, J.; Hu, J.; Zhi, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Bao, G. Feature-enhanced CenterNet for small object detection in remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, H.; Yang, J.; Jiao, H.; Feng, Z.; Chen, L.; Gao, T. Fast vehicle detection algorithm in traffic scene based on improved SSD. Measurement 2022, 201, 111655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadharshini, G.; Dolly, D.R.J. Comparative investigations on tomato leaf disease detection and classification using CNN, R-CNN, fast R-CNN and faster R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS), Coimbatore, India, 17–18 March 2023; pp. 1540–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Zong, Z.; Xuan, K.; Zhang, R.; Shi, W.; Liu, H.; Han, Z.; Luan, T. Detection of maturity and counting of blueberry fruits based on attention mechanism and bi-directional feature pyramid network. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 6193–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xu, H.; Liu, B.; He, D.; He, J.; Zhang, H.; Geng, N. MEAN-SSD: A novel real-time detector for apple leaf diseases using improved light-weight convolutional neural networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 189, 106379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, S. A high-precision detection method of apple leaf diseases using improved faster R-CNN. Agriculture 2023, 13, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhao, X.; Yue, X.; Yue, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, H.; Zhang, X. A lightweight YOLOv8 model for apple leaf disease detection. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang-Anh, N.D.; Manh, H.H.; Pham, D.M.; Nguyen, M.A.; Duong Le, B.T.; Lan-Anh, D.T.; Pham, P.N. Efficient Multi-Scale Attention Based on Mobilenetv4 Followed OmniSPPF and ODGC2f for Small-Scale Egg Identification. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on “Modelling, Computation and Optimization in Information Systems and Management Sciences” MCO 2025, Metz, France, 4–6 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Kampffmeyer, M.; Jenssen, R. and Salberg, A.B. Dense dilated convolutions’ merging network for land cover classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 6309–6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Hu, B. An attention-based CoT-ResNet with channel shuffle mechanism for classification of alzheimer’s disease levels. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 930584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, M.T.; Kim, T.D.; Ha, M.H.; Chen, O.T.C.; Nguyen, D.C.; Tran, A.L.Q. An Effective Method for Detecting Personal Protective Equipment at Real Construction Sites Using the Improved YOLOv5s with SIoU Loss Function. In Proceedings of the 2023 RIVF International Conference on Computing and Communication Technologies (RIVF), Hanoi, Vietnam, 23–25 December 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).