Abstract

Steel portal frames are widely used in industrial buildings due to their high strength-to-weight ratio and rapid erection capability. However, many existing structures exhibit insufficient load-carrying capacity under current design requirements. This study investigates the use of external post-tensioning (PT) cables and rigid wedge anchorages to enhance the overall performance of steel portal frames. Two stages of numerical analysis were performed: (i) two-dimensional parametric studies to identify the most efficient configuration and (ii) three-dimensional verification under combined gravity, wind, and seismic loading conditions. Results show that the proposed PT system significantly increases the load-carrying capacity of both beams and columns, reduces bending demands, and improves global stability without major geometric modification. The strengthening method is safe, reversible, and offers a practical alternative to conventional welded or plated retrofit techniques.

1. Introduction

Steel construction has gained significant momentum in Türkiye over the past decade, driven by advances in off-site fabrication, stringent quality control, and superior mechanical and seismic performance. Its ability to provide long, unobstructed spans with lightweight and recyclable materials has made it the preferred choice for industrial facilities, particularly those located in high seismic hazard zones [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. However, many existing steel buildings were designed according to outdated standards, resulting in insufficient load-carrying capacity under current design requirements. This problem is further exacerbated by functional modifications such as additional roof equipment, increased snow accumulation, or changes in occupancy, all of which contribute to a growing demand for strengthening and retrofitting strategies [9,10,11,12].

Traditional strengthening approaches—including welded flange plates, haunch extensions, and CFRP laminates—can improve structural capacity but often require on-site hot work, interrupt industrial operations, and may damage existing members. As an alternative, external post-tensioning (PT) has emerged as a lightweight, reversible, and non-intrusive method capable of enhancing structural performance without altering the geometry of existing members. By applying controlled axial forces, external PT systems reduce flexural demands and deflections, thereby improving both stiffness and strength [13,14,15,16,17]. Despite its advantages, most PT-related research has focused on isolated structural components such as girders, struts, or anchorage systems rather than on the holistic behavior of complete frames.

Early studies primarily examined member-level responses. Hosseinejad et al. [18] demonstrated that externally anchored PT cables can effectively increase the capacity of long-span steel beams in industrial facilities. Yücekul [19] showed through theoretical, numerical, and experimental work that prestressing substantially improves the flexural performance of steel girders. Ghannam et al. [20] extended these insights to steel truss systems, reporting enhanced global stiffness and delayed yielding. Garlock et al. [21] evaluated the seismic behavior of post-tensioned steel frames and observed improved energy dissipation and reduced lateral displacements. These studies collectively demonstrate that external PT enhances the performance of various steel structural forms by modifying internal force pathways and introducing beneficial pre-compression. Nevertheless, the majority of prior research has been limited to component-based evaluations or simplified two-dimensional analyses, without examining full-frame behavior, anchorage stiffness, moment–shear interaction, or the stability implications of externally applied axial forces.

Recent research has expanded the understanding of external PT in portal-frame systems. Xin et al. [17] proposed a sickle-type self-locking anchorage that transfers cable forces by friction without welding or drilling, confirming its efficiency through finite-element (FEM) analysis and full-scale field strengthening application. Yu-Qing et al. [15] designed a removable H-type assembled anchoring joint, reporting up to 40% reduction in mid-span bending moments and significant deflection control. Liu et al. [22] introduced a screw-type adjustable strut capable of applying uniform prestress through rotation, achieving approximately 45% deflection reduction in both simulations and experiments. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the practicality of external PT for localized strengthening of portal frames, yet they focus primarily on individual components—anchors or struts—rather than on the overall system behavior of full portal frames under combined vertical and lateral loads [15,17,18,19,22]. As illustrated in Figure 1, external PT systems typically transfer axial forces through cable–wedge anchorage assemblies, thereby reducing bending demands in steel girders. Building on these earlier findings, the present research bridges the gap between component-level studies and full-frame analysis by examining the integrated behavior of post-tensioned steel portal frames under combined loading conditions.

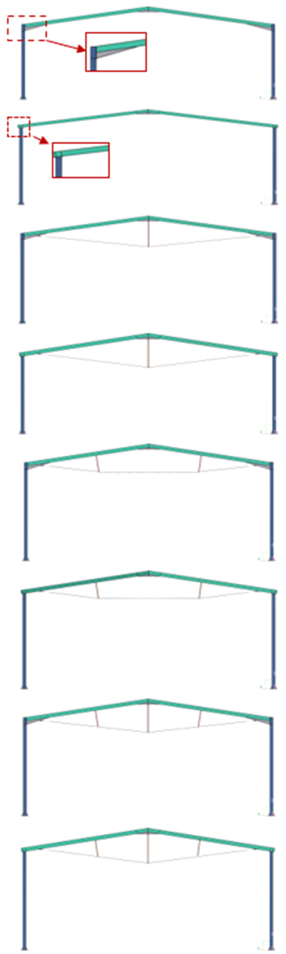

Figure 1.

(a) Steel beam reinforced with a post-tensioning cable; (b) Wedge-anchor detail of the post-tensioning cable.

The novelty of the present study lies in delivering a full system-level evaluation of external post-tensioning in steel portal frames, simultaneously considering rigid and pinned beam–column connections, multiple tendon configurations, and both 2D and 3D analyses. Unlike previous component-based PT research that focuses on girders, anchorage devices, or struts, this work provides an integrated assessment of capacity enhancement, internal-force redistribution, axial–moment interaction, and global stability at the frame level. This is a study to quantify how external PT affects the combined strength–stability behavior of portal frames under realistic gravity, wind, and seismic loading conditions.

This gap defines the novelty of the present study. Unlike previous device-oriented investigations, this work performs a comprehensive system-level assessment of single-storey steel portal frames strengthened with externally applied PT cables. The analyses explicitly consider both moment-resisting (rigid) and moment-releasing (pinned) beam–column connections, three distinct cable configurations, anchorage stiffness, geometric nonlinearity, and realistic loading scenarios. This combination of parameters has not been systematically examined in the literature.

Based on this gap, the study is guided by the following research questions:

- How do external PT cables influence the global and member-level capacity, internal-force redistribution, and stability of portal frames with both rigid and pinned beam–column connections?

- How do different cable configurations and sag geometries modify bending demands, axial compression, and potential shifts in failure mechanisms?

- Can external PT provide a rapid, cost-effective, and non-disruptive strengthening alternative to traditional welded or plated retrofits?

To address these questions, two-dimensional portal-frame models incorporating three PT configurations were first analyzed to establish capacity–stability trends. Based on these findings, a three-dimensional structural model was developed to evaluate the influence of PT on global performance under combined vertical and lateral loads. The analyses were performed separately for rigid and pinned connections to reveal how connection flexibility interacts with cable-induced forces.

The scope of this study is limited to single-storey steel portal frames with spans up to 25 m and eave heights below 10 m, representing typical industrial building configurations in Türkiye. The analyses are conducted within a static, elastic, and strength-based analytical framework; therefore, dynamic behavior, time-history effects, and full elastoplastic deformation demands are not evaluated. Long-term prestress losses, fatigue behavior, and construction-sequence effects are discussed only qualitatively. Accordingly, the findings of the present study are applicable primarily to regular portal-frame typologies and should not be directly generalized to multi-storey or irregular structural systems.

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the material and geometric characteristics of the two-dimensional (2D) portal frame and the three-dimensional (3D) structure, the applied loads and governing design codes, the operational principle of the strengthening system, and the modeling configurations adopted in the numerical analyses.

2.1. Geometric Properties of the Portal Frame

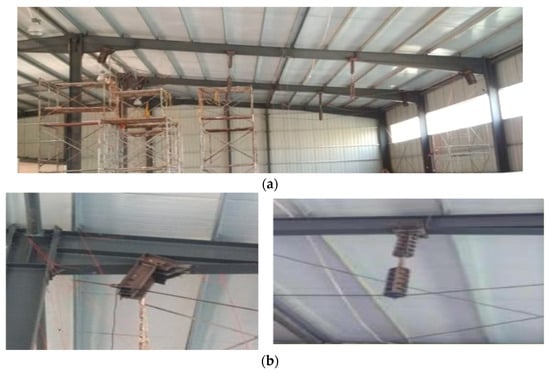

The reference portal frame consists of columns 6.5 m in height, a bay width of 20 m, a ridge height of 8 m above ground level, and a roof slope of 15%. Eighteen purlins, spaced at 6 m intervals between consecutive frames, were considered to define the weak-axis buckling length and roof load distribution. The geometric proportions (height-to-span ratio and roof slope) were selected to represent typical industrial portal frames used in practice. The columns and beams were modeled in SAP2000 v25 [23] using frame elements with six degrees of freedom per node. The section profiles were designated as HEA 260 for the columns and IPE 450 for the beams. All members were assumed to be fabricated from S235 structural steel, characterized by a yield strength (fy) of 235 MPa, an ultimate tensile strength (fu) of 360 MPa, an elastic modulus (E) of 210 GPa, and a Poisson’s ratio (ν) of 0.3. The self-weight of the members was automatically included by the program. The portal frame geometry and chosen profiles are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Geometry of the portal frame and section profiles used.

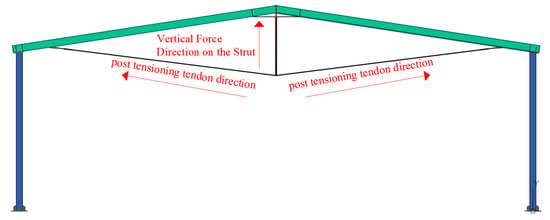

Two reference models were defined based on their connection details: DTRF (Reference Design Type with Fixed Connections) and DTRP (Reference Design Type with Pinned Connections). To evaluate the influence of external post-tensioning (PT) on the global response, six strengthened variants—DT1F, DT1P, DT2F, DT2P, DT3F, and DT3P—were generated. The PT configurations (DT1F, DT1P, DT2F, DT2P, DT3F, and DT3P) were selected to represent two practically implementable cable layouts (two-strut and three-strut systems), each examined for both moment-resisting (F) and pinned (P) beam–column connections. This matrix structure was designed to systematically isolate the influence of (i) connection rigidity and (ii) cable geometry on internal force redistribution and global frame stability. The complete set of configurations is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Design Configurations.

For all strengthened configurations, a 24 mm-diameter high-strength steel tendon was modeled using tension-only frame elements. Each tendon was assigned a target axial force of 300 kN, corresponding to approximately 65% of its nominal tensile capacity (457.5 kN), thereby maintaining a 35% safety margin (Table 2). This prestress level falls within the commonly recommended utilization range of 55–70% for external post-tensioning systems, as reported in recent studies [15,17,22]. Before adopting this value, AISC 360-16 [24] axial-compression and Euler buckling checks were performed. The resulting axial force corresponded to only 18% of the LRFD compressive capacity (ϕPn) and 22% of the elastic buckling limit (Pcr), confirming that the selected prestress level does not introduce instability or excessive axial demand. Additionally, a preliminary parametric sweep (100–400 kN) indicated that prestress levels below 200 kN produce limited structural enhancement, whereas values above 350 kN introduce unnecessary axial dominance with diminishing returns. The 300 kN level provided the optimal reduction in bending moments (up to 40–50%) and the most favorable demand-to-capacity (D/C) ratios for both beams and columns.

Table 2.

Mechanical Properties of the Post-Tensioning Tendon [25].

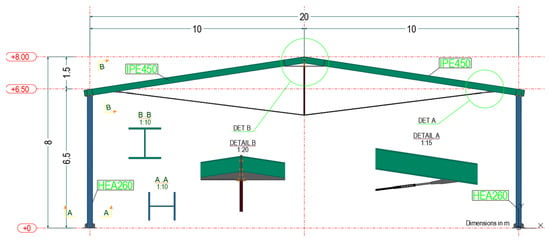

The cables were modeled using the Maximum Vertical Sag option with 16 cable segments, consistent with standard catenary discretization in SAP2000 V23 [23]. A total vertical sag of 2.5 m, measured relative to the beam ridge, was assigned; this value included approximately 1.0 m of vertical sag along the cable’s own axis, as defined in the cable-geometry input parameters. Axial forces were transferred to the rafters through rigid wedge anchorages (Figure 3), ensuring full load transfer without slip. In rigid-connection cases, the post-tensioning cables were anchored at beam–column joint rather than directly to the column members. Thus, vertical members are not physically connected to the cables; instead, the axial PT force is transferred through the beam–column joint regions. For pinned-connection models, column bases were assumed fully fixed, while the beam-column joints were modeled as moment-releasing. For rigid-connection models, both the column bases and beam-column joints were defined as fully restrained. These boundary conditions are consistent with conventional industrial portal-frame design practice.

Figure 3.

Working Principle of the Strengthened System.

All analyses were performed using SAP2000’s linear static solver with a full stiffness-matrix formulation. Geometric nonlinearity (P–Δ effects) was not activated, as the structural response remained within the elastic range under the applied load levels. The analysis adopted a 2% Rayleigh damping ratio, a commonly accepted value for single-storey steel frames. Since the investigated system represents a single-storey steel portal frame with bolted and welded joints, the inherent damping is expected to be low; thus, a 2% critical damping ratio was considered appropriate, consistent with standard practice and with previous investigations on externally post-tensioned steel systems [15,17,22].

2.2. Portal Frame Loading and Design Principles

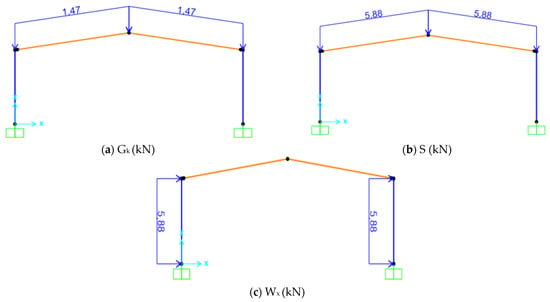

The applied loads included the frame self-weight (G), cladding dead load (Gk), snow load (S), wind pressure (Wx), and seismic load (Ex). The cladding weight was taken as 0.25 kN/m2; assuming a 6 m bay spacing, this corresponds to a distributed load of 1.47 kN/m acting on the beams. The snow load was determined according to TS EN 1991-1-3 [26] for the city of Konya, located at an altitude of 1016 m. Considering an exposure coefficient Ce = 1.0 and a roof slope of 15%, the resulting snow pressure was approximately 0.98 kN/m2, equivalent to 5.88 kN/m per frame. Wind pressure was computed following TS EN 1991-1-4 [27] for terrain category III, yielding a similar surface pressure of approximately 0.98 kN/m2 (5.88 kN/m line load). Seismic effects were calculated in accordance with the Turkish Building Earthquake Code (TBEC 2018) [11] using the equivalent lateral force procedure. Site parameters were derived from the AFAD hazard map [28], including a Ct coefficient (used in the empirical fundamental period calculation) of 0.08, an eccentricity of 5%, and a long-period spectral value of Tl = 6.0 s. The mapped spectral accelerations were taken as Ss = 0.305 (short-period spectral acceleration) and S1 = 0.073 (1 s spectral acceleration), while the local site class was defined as ZD. Seismic design parameters were assigned as a response modification factor R = 4, overstrength factor D = 2.5, and occupancy importance factor I = 1. As the 2D analysis was conducted in the X–Z plane, the horizontal effects were considered only in the global X direction. The cladding load (Gk), snow load (S), and wind load in the X direction (Wx) are presented in Figure 4, while the seismic load (Ex) was directly applied to the SAP2000 V23 [23] numerical model in accordance with the specified parameters.

Figure 4.

Loads Acting on the Frame (kN): (a) Gk, Cladding Load; (b) S, Snow Load; (c) Wx, Wind Load in the X Direction.

Design checks were carried out in compliance with the Steel Structures Design, Calculation and Construction Regulation (SSDCR 2016) [29] and AISC 360-16 [24], adopting the Load and Resistance Factor Design (LRFD) method. The frame type was classified as an Ordinary Concentrically Braced Frame with Limited Ductility (OCBFI). The column bases were modeled as pinned supports, while the beam–column connections were defined as either rigid or hinged, depending on the model type.

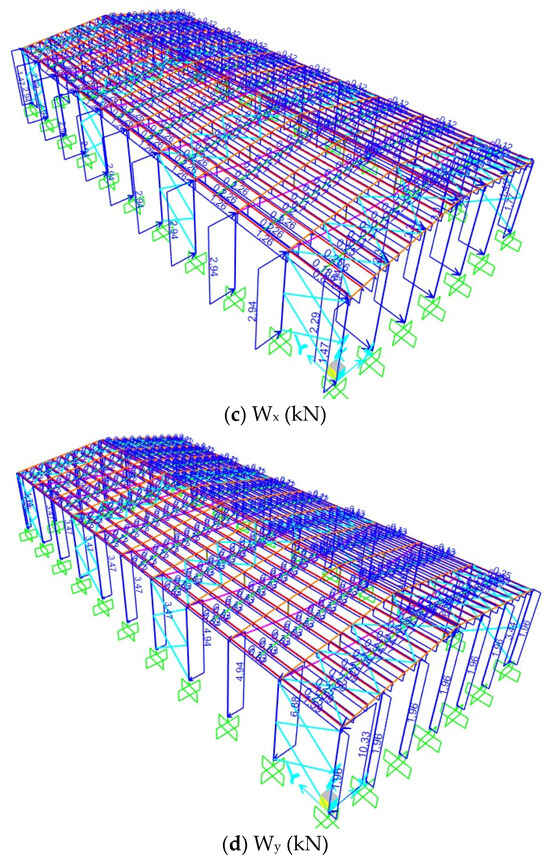

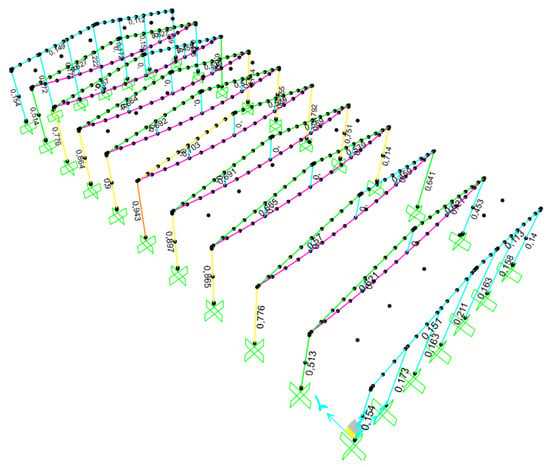

2.3. Three-Dimensional Structural Geometric Properties

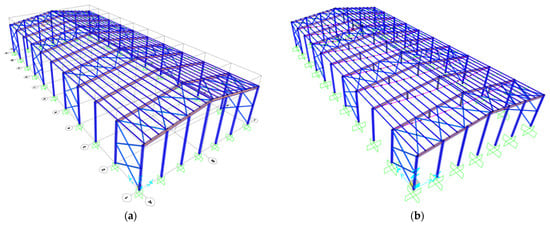

A 3D model was developed based on the configuration that yielded the most favorable D/C ratio in the 2D analyses, identified as DT3F. The 3D structure comprises columns 8 m in height, a 25 m span, an eave-to-ridge height of 10 m, and a roof slope of 15%. The spacing between portal frames is 5.5 m, resulting in a total building length of 55 m. Ten purlins per roof side (20 in total) were modeled at 1.25 m intervals. The member cross-sections were selected as HEA 280 for columns, HEA 200 for wind columns, IPE 400 for beams, IPE 180 for purlins, and RHS 100 × 3 mm for bracings. The strengthened variant was reinforced with 24 mm steel cables and anchorage wedges identical to those in DT3F. Perspective and sectional views of the model are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

(a) Perspective view of the existing structure; (b) Perspective view of the reinforced structure.

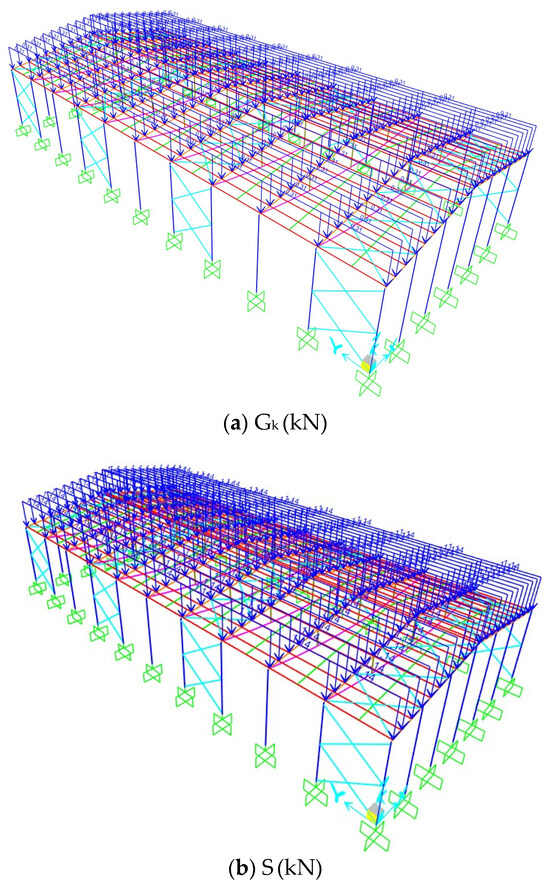

2.4. Three-Dimensional Structure Loads and Design

The applied loads for the 3D model included self-weight (G), cladding dead load (Gk = 0.25 kN/m2), snow load (S ≈ 0.92 kN/m2), wind forces in both global directions (Wx and Wy), and seismic forces in both horizontal directions (Ex and Ey). Snow and wind loads were determined according to TS EN 1991-1-3 [26] and TS EN 1991-1-4 [27], respectively. Seismic forces were computed using TBEC 2018 [11] based on the same site parameters defined in Section 2.2, where the mapped spectral accelerations were taken as Ss = 0.305 (short-period spectral acceleration) and S1 = 0.073 (1 s spectral acceleration), and the local site class was defined as ZD. The seismic design coefficients were assigned as a response modification factor R = 4, an overstrength factor D = 2.5, and an occupancy importance factor I = 1. All load definitions were implemented directly in SAP2000 [23]. The cladding load (Gk), snow load (S), and wind loads (Wx and Wy) applied to the three-dimensional structure are illustrated in Figure 6; the seismic loads (Ex and Ey) were applied directly through the numerical model as described above.

Figure 6.

Loads acting on the three-dimensional structure (kN): (a) Gk, cladding dead load; (b) S, snow load; (c) Wx, wind load in the X-direction; (d) Wy, wind load in the Y-direction.

For the strengthened model, an additional post-tensioning cable load was applied. To minimize the influence of geometric variations on the prestressing force, minor adjustments were made to keep the cable tension close to the target value of 300 kN. SAP2000’s target-force loading definition was employed, whereby the software automatically applies the specified axial force under combined gravity, wind, and seismic effects. In both the 2D and 3D models, each cable was defined with a fixed 1.0 m drop below the column top. Owing to the difference in roof rise heights—1.5 m in the 2D model and 2.0 m in the 3D model—the resulting total vertical sags measured from the beam ridge were 2.5 m and 3.0 m, respectively. These values fall within the typical range reported in previous studies (0.8–3.0 m) and were found to be geometrically feasible for the portal-frame layout. Preliminary sensitivity screening showed that intermediate sag values exhibit similar behavioral trends, whereas extreme values are either geometrically infeasible or require unrealistically high prestress forces. Small discrepancies (<2%) between the achieved and target loads were considered negligible. A structural damping ratio of 2% was adopted, consistent with typical values reported for steel portal frames in previous studies [15,22].

2.5. Model Verification and Limitations

Since experimental testing was beyond the scope of this study, model reliability was verified indirectly through comparison with previously published results. The predicted reductions in mid-span bending moments (≈40–50%) and vertical deflections (≈45%) are consistent with the findings of Yu-Qing et al. [15] and Liu et al. [22] for similar external post-tensioned systems, indicating that the modeling approach accurately captures the global behavior of the strengthened portal frame. However, it should be noted that this verification remains comparative rather than experimental. Parameters such as joint flexibility, anchorage deformation, frictional losses, and time-dependent effects were not explicitly modeled and are discussed qualitatively in Section 3.2.4. Additionally, the axial–moment interaction (ϕPn–Mn) and buckling safety checks of the strengthened rafter were independently verified using AISC 360-16 [24] design equations. The design-based hand calculations showed that the SAP2000-predicted internal forces correspond to only 18–22% of the member capacity, demonstrating full consistency between numerical results and codified analytical predictions.

3. Analysis Results and Evaluation

3.1. Two-Dimensional Portal Frame Analysis

In the first phase of the study, two-dimensional analyses were conducted to evaluate the influence of post-tensioning configuration and connection type on the structural response of the portal frame. For each design type, the axial, shear, and bending moment diagrams were examined, and the demand-to-capacity (D/C) ratios were used as the principal performance indicator. The demand-to-capacity (D/C) ratio, defined as the ratio of applied internal force to the design capacity of each member, was evaluated to determine the efficiency of each design type. The load combinations producing the maximum effects on the frame were identified as 1.2G + 1.6S + 0.8Wx and 1.2G + 1.6S − 0.8Wx. Since the only difference between these is the direction of the wind load, detailed evaluation was carried out under 1.2G + 1.2Gk + 1.6S + 0.8Wx, representing the governing condition. The maximum internal forces for all design types are summarized in Table 3, while Table 4 and Table 5 list the percentage variations relative to the fixed and pinned reference models, respectively.

Table 3.

The maximum internal forces for all design types.

Table 4.

Percent Change in Forces Relative to Fixed-Connection Reference Design Type.

Table 5.

Percentage Change in Force According to the Reference Design Type of the Pinned Connection.

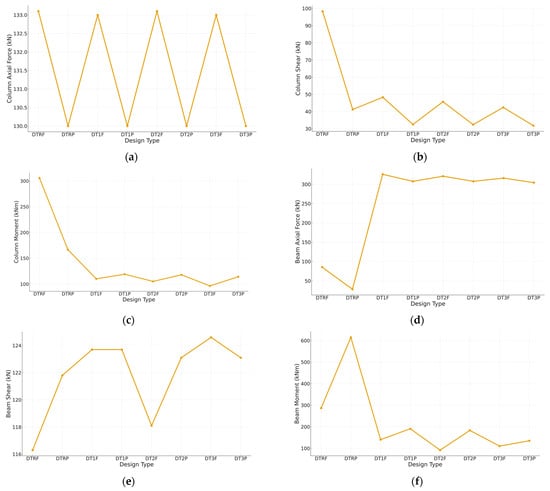

The results indicate that the maximum bending moment in columns decreased by up to 68% for fixed-connection types and 31% for pinned types compared with their respective reference models. The DT3F configuration achieved the best performance, reducing column moments from 305.8 kNm to 96.5 kNm. Although axial forces in the columns remained nearly constant, shear forces decreased by approximately 50–57% with the inclusion of post-tensioning. Across all PT configurations, column axial forces varied by less than 1%, which is below the commonly accepted 5% threshold used to classify changes as non-significant for global frame behavior.

In beams, the introduction of post-tensioning caused a pronounced increase in axial force, reaching nearly three times the reference level—an expected outcome of the prestressing action that transforms the beam into a combined bending–compression member. Simultaneously, the bending moments in beams decreased significantly, by 62–78%, depending on the connection type. This behavior arises from the opposing cable tension that redistributes bending stresses along the beam and reduces moment concentration at mid-span.

The fixed connection type provided slightly better moment control, while pinned connections showed modest benefits in limiting axial-force accumulation in beams. Variations in beam shear forces were minimal (<10%), suggesting that the post-tensioning primarily affected flexural rather than shear behavior.

The internal-force comparisons for all design types are illustrated in Figure 7. The diagrams clearly show smoother bending-moment distributions and more uniform shear-force patterns in the post-tensioned frames, confirming the balancing effect of the external cables. These trends are consistent with the findings of Yu-Qing et al. and Liu et al. [15,22], who reported 35–55% moment reductions in externally post-tensioned steel frames.

Figure 7.

Internal Force Graphs for Columns and Beams Across All Design Types (a) Column Axial Force vs. Design Type; (b) Column Shear Force vs. Design Type; (c) Column Moment vs. Design Type; (d) Beam Axial Force vs. Design Type; (e) Beam Shear Force vs. Design Type; (f) Beam Moment vs. Design Type.

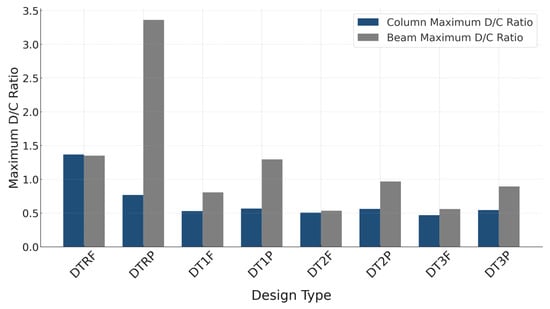

The maximum D/C ratios for all design types are presented in Table 6, and their relative changes are listed in Table 7 and Table 8. The reference model with fixed connections (DTRF) exhibited D/C ratios exceeding unity (1.35–1.37), indicating overstressed members. After strengthening, the DT3F model achieved reductions of 66% in columns and 58% in beams, resulting in maximum D/C ratios of 0.47 and 0.56, respectively—well within safe design limits. For pinned cases, the DT3P configuration provided comparable improvements, reducing the column and beam ratios by 29% and 73%, respectively.

Table 6.

Portal Frame D/C Ratios for All Design Types.

Table 7.

Percentage Change in D/C Ratio Relative to the Reference Design Type for Fixed Connection.

Table 8.

Percentage Change in D/C Ratio Relative to the Reference Design Type for Pinned Connection.

These outcomes demonstrate that external post-tensioning not only reduces internal-force magnitudes but also establishes a more balanced load transfer within the frame. The convergence of D/C ratios between fixed and pinned systems indicates that post-tensioning mitigates sensitivity to connection rigidity. The comparative graphical representation in Figure 8 clearly illustrates the substantial reductions achieved in both beam and column D/C ratios across all strengthened configurations.

Figure 8.

Comparative Representation of Demand-to-Capacity Ratios in Column and Beam Elements According to Design Types in Portal Frame Systems.

Among these, the DT3F configuration consistently exhibited the lowest D/C ratios and the most uniform stress distribution, confirming its superiority in enhancing the overall structural efficiency of the portal frame.

3.2. Analysis Results and Evaluation of the Three-Dimensional Structural Model

In the second phase, three-dimensional analyses were performed to assess the overall behavior of the existing and strengthened structures under combined gravity, wind, and seismic loads. The governing load combination producing maximum stress effects was 1.2G + 1.2Q + 1.6S − 0.8Wx.

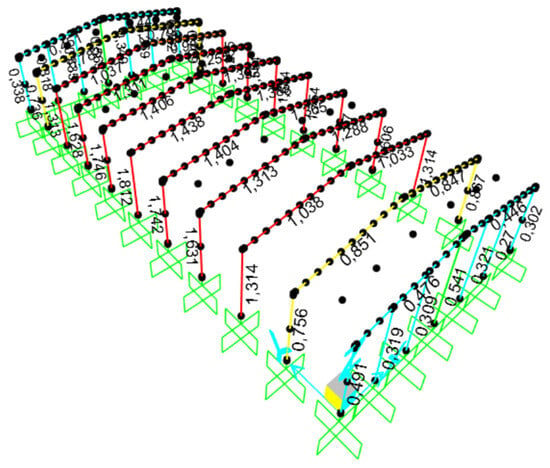

3.2.1. Existing Structure

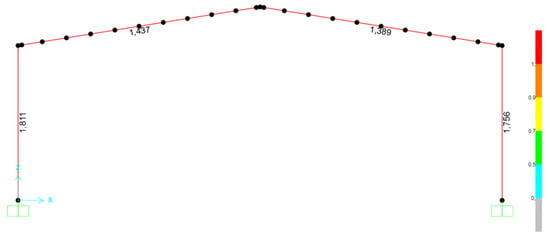

The demand-to-capacity (D/C) distributions for the existing structure are illustrated in Figure 9, while the internal-force diagrams along the critical 6–6 axis are provided in Figure 10. The variation in D/C ratios along the same axis is shown in Figure 11. The unstrengthened frame exhibited high bending and shear demands at the beam–column junctions and ridge regions, with maximum column and beam moments of 485 kNm and 461 kNm, respectively. These findings indicate insufficient flexural stiffness and localized overstressing near the beam–column junctions under the combined effects of gravity and lateral loads.

Figure 9.

Capacity Ratios of beams and columns of the existing structure.

Figure 10.

Internal Force Diagrams of the Existing Structure along Axis 6–6: (a) Axial force diagram (kN); (b) Shear force diagram (kN); (c) Moment diagram (kNm).

Figure 11.

Demand-to-Capacity Ratio of the Existing Structure Along Axis 6–6.

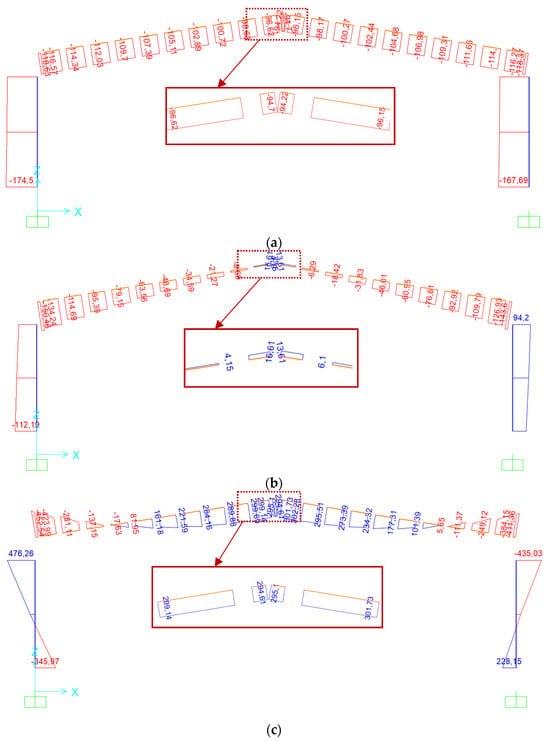

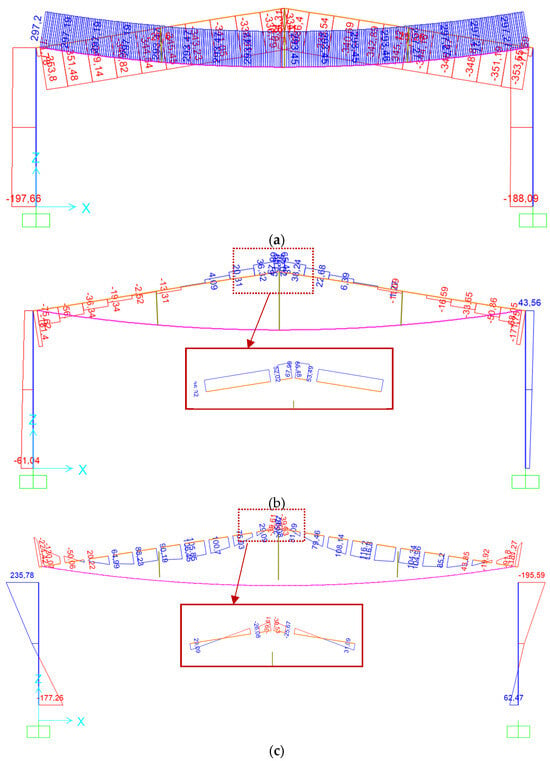

3.2.2. Retrofitted Structure

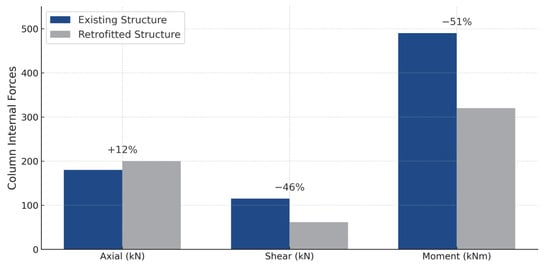

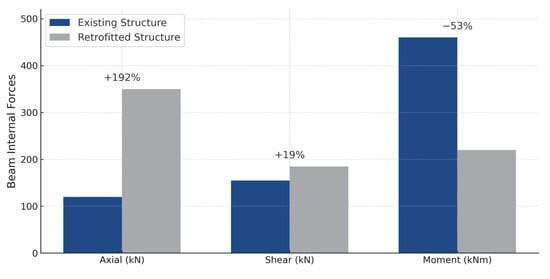

The results for the strengthened model, retrofitted according to the DT3F configuration using post-tensioning cables and anchorage wedges, are presented in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14. The inclusion of the external cable system produced a distinct reduction in bending moments at the beam–column joint regions and at the ridge point, accompanied by a moderate increase in shear forces. The induced prestressing transformed the beams into compression–bending hybrid members, reducing mid-span curvature and improving the overall load redistribution pattern. As summarized in Table 9, column shear and moment forces decreased by 46% and 50%, respectively, while beam moments reduced by 52%. The beam axial force increased by approximately 200%, consistent with the compressive action induced by post-tensioning, and beam shear forces exhibited a modest 18% increase. These variations are depicted graphically in Figure 15 and Figure 16, demonstrating the balancing effect of the external tendons on the internal force flow.

Figure 12.

Capacity Ratios of beams and columns of the Retrofitted Structure.

Figure 13.

Internal Force Diagrams Along Axis 6–6: (a) Axial force diagram (kN); (b) Shear force diagram (kN); (c) Moment diagram (kNm).

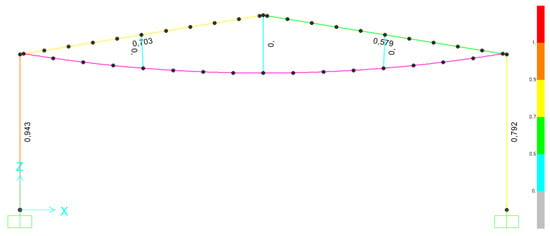

Figure 14.

Demand-to-Capacity Ratio Along Axis 6–6.

Table 9.

Maximum Internal Forces and Percentage Changes for Column and Beam Elements According to Structural Model.

Figure 15.

Column Internal Force Comparison by Structural Model.

Figure 16.

Beam Internal Force Comparison by Structural Model.

3.2.3. Discussion of Three-Dimensional Behavior

The comparison of the two models confirms that the proposed post-tensioning system effectively mitigates flexural demands at the beam–column joint regions and ridge point, resulting in moment reductions of roughly 50% in both columns and beams. The moderate increase in axial and shear forces remains within the elastic range and contributes to a more uniform internal-force equilibrium.

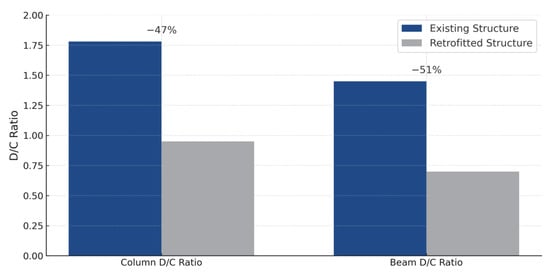

The corresponding D/C ratios, listed in Table 10, decreased from 1.81 to 0.94 for columns and from 1.44 to 0.70 for beams—representing reductions of 48% and 51%, respectively. The graphical comparison in Figure 17 further illustrates these improvements.

Table 10.

Maximum D/C Ratios and Percentage Changes for Column and Beam Elements According to Structural Model.

Figure 17.

Comparison of D/C Ratios by Structural Model.

The strengthened structure thus satisfies both strength and serviceability requirements in accordance with AISC 360-16 and TBEC 2018 [11,24]. The increased stiffness and reduced deformations observed in the analyses validate the use of a linear-elastic model for global assessment.

These findings are in agreement with the results reported by Xin et al. [17] for similar externally anchored portal frames, confirming that the adopted modeling approach accurately captures the essential mechanical behavior of post-tensioned steel structures.

3.2.4. Buckling Assessment and Safety Evaluation

The introduction of post-tensioning induces additional compressive stresses in the beam members; therefore, the risk of instability was examined in accordance with AISC 360-16 [24] and classical Euler buckling theory. The analysis was performed using the design compressive strength equations of AISC E.3 and verified by the elastic critical buckling load.

- (a)

- Design Axial Capacity (AISC 360-16 LRFD)

The nominal compressive strength of a steel member is defined by AISC Equation (E3-2):

where = 0.9 is the resistance factor for compression, Ag is the gross area of the cross-section, and Fcr is the critical buckling stress, determined as:

with the nondimensional slenderness parameter:

For the IPE400 beam (, , ),

Accordingly, Equation (2) (upper case) is applicable:

Substituting into Equation (1):

The maximum compressive force obtained from analysis is

and the corresponding utilization ratio is

indicating that the beam carries only 18% of its design axial capacity, far below the AISC limit of unity.

- (b)

- Elastic Euler Buckling Verification

The elastic critical buckling load is expressed as [30]:

where is the least-axis moment of inertia.

For , , and :

The ratio of the applied axial load to the elastic buckling capacity is

indicating that the beam was stressed to approximately 22% of its elastic buckling limit.

- (c)

- Axial–Moment Interaction Verification (ϕPn–Mn)

In addition to the axial compressive strength and elastic buckling verification, the combined axial–flexural interaction (Equation (10)) was evaluated using the AISC 360-16 LRFD provisions. The interaction equation for members subjected to simultaneous axial compression and bending is given by:

where

- : applied axial force from analysis

- : applied bending moment

- : design axial compressive strength

- : design flexural strength

- : LRFD resistance factors

For the strengthened frame, the maximum demand ratios were obtained from SAP2000 along the governing 6–6 axis. Using the axial force and the corresponding moment demand , the interaction ratio becomes:

According to both AISC 360-16 LRFD and Euler elastic buckling theory [30], the beam remains well within the safe range. The applied compressive load represents approximately 18% of the design axial capacity and 22% of the elastic buckling limit; thus, neither global flexural buckling nor lateral-torsional buckling (LTB) is expected within the elastic domain. The compact section classification and verified unbraced length checks (KL/r = 38 < 200) further confirm the adequacy of the member. In addition to axial and global buckling verification, the combined axial–moment interaction was evaluated using the AISC ϕPn–ϕMn criteria. The maximum interaction ratio was obtained as:

indicating that the strengthened rafter satisfies the combined compression–bending limit state with a 40% safety margin. These results collectively demonstrate that the additional axial compression introduced by the external post-tensioning does not pose a risk of global or local instability. The applied axial force corresponds to only 18% of the AISC LRFD compressive strength and 22% of the Euler buckling limit, while the axial–moment interaction ratio remains significantly below unity. Since the IPE400 rafter is a compact section with an adequate unbraced length, neither flexural buckling nor local flange/web buckling is expected. Therefore, the post-tensioning system enhances flexural performance without compromising the member-level stability of the frame. Comparable studies, such as Yu-Qing et al. and Liu et al. [15,22], have reported similar safety margins, where axial compression induced by external post-tensioning remained below 30% of the critical buckling threshold for portal-frame applications. Consequently, the post-tensioning system adopted herein enhances flexural performance and redistributes internal forces without compromising either member-level or global stability of the steel frame. In addition to these stability verifications, the implications of the post-tensioning-induced moment reduction were also examined at a conceptual level. The 50% decrease in bending demand leads to a redistribution of internal forces toward axial compression in the rafter, which is consistent with the mechanics of externally applied post-tensioning. Since all axial demands remain within 18–22% of both the AISC design compressive strength and the Euler buckling limit, this redistribution does not pose any risk of instability. Fatigue effects, cyclic behavior, and local detailing requirements (e.g., bolt/weld demands and panel-zone response) were not modeled in this static, strength-based framework and thus remain outside the scope of the present study; however, these topics are acknowledged as important areas for future research.

- (d)

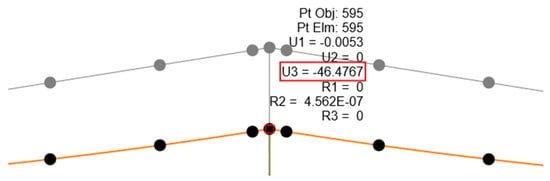

- Vertical Deflection Check (Service Limit State)

For the governing service load combination , the maximum downward deflection [29] at the rafter mid-span was obtained from SAP2000 as Δmax = 46.5 mm (Figure 18). This value satisfies the commonly used serviceability criterion for roof girders,

and also remains below the stricter recommended limit,

Figure 18.

Vertical mid-span deflection of the strengthened rafter under service load combination.

Therefore, the strengthened portal frame meets vertical deflection requirements, and the upward pre-camber induced by the external post-tensioning cables further reduces the effective deflection under snow and cladding loads.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluated the effectiveness of using external post-tensioning (PT) cables and rigid wedge anchorages to enhance the load-carrying capacity of steel portal frames. Two stages of numerical analysis were performed: (i) two-dimensional parametric assessments to identify the most efficient PT configuration, and (ii) three-dimensional verification under combined gravity, wind, and seismic loading.

The main findings are summarized as follows:

- External post-tensioning was found to increase the flexural and axial load-carrying capacities of portal-frame members by introducing beneficial pre-compression. The applied cable force reduced tensile stresses in beams and lowered bending demands in columns, contributing to a more uniform internal force distribution.

- For the optimum configuration (DT3F), the demand-to-capacity (D/C) ratios of the columns and beams decreased by approximately 66% and 58%, respectively, relative to the unstrengthened frame. These reductions demonstrate a notable enhancement in the reserve strength within the evaluated loading conditions.

- The applied tendon force of 300 kN remained well within safe stability limits—utilizing only 18% of the design compressive capacity and 22% of the Euler buckling load. The strengthened rafter also satisfied the axial–moment interaction (ϕPn–Mn) requirement with a 40% safety margin. These results indicate that, within the examined configuration, PT-induced compression does not compromise member stability.

- Among the analyzed configurations, the DT3F system provided the most balanced structural response, offering improved capacity without the need for substantial material addition or geometric modification. Within the investigated parameter range, this configuration appears promising for retrofit or optimization of single-span portal frames.

- The applicability of the proposed technique is limited to single-storey, regular steel portal frames with spans up to 25–28 m and eave heights below 10 m. The analyses were conducted under static, elastic, and strength-based assumptions; therefore, dynamic behavior, long-term prestress losses, anchorage deformation, temperature effects, and construction-sequence influences were not modeled. These aspects represent important areas for future research.

- As a retrofit solution, external PT offers a non-invasive and reversible alternative that can be installed with minimal interruption to industrial operations. It may also support design optimization in new structures by enabling reduced section sizes and improved material efficiency.

- Future studies should include experimental verification, cyclic and fatigue testing, long-term monitoring of prestress losses, and seismic fragility assessment to extend the findings to broader structural contexts.

- A qualitative comparison with conventional strengthening techniques was also provided. While methods such as haunch extensions, flange-plate additions, CFRP laminates, or steel bracing can enhance local strength, they typically require hot work, additional dead load, and operational downtime. In contrast, external PT increases global load-carrying capacity by improving axial–flexural interaction without altering member geometry. Nevertheless, detailed cost–benefit analysis, long-term durability, and maintenance considerations remain topics for future investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K.; software, H.Ş.; validation, H.Ş. and M.K.; formal analysis, H.Ş. and M.K.; investigation, H.Ş. and M.K.; resources, H.Ş.; data curation, H.Ş.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Ş. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The results of this study are based on a section of the Master’s thesis prepared by Hüseyin ŞEN at the Graduate School of Konya Technical University. Mustafa KOÇER is the thesis advisor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Symbol/Acronym | Definition/Description |

| PT | Post-tensioning (external prestressing cable system) |

| D/C | Demand-to-capacity ratio |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| G | Dead load (self-weight of structure) |

| Gk | Additional permanent load (cladding dead load) |

| S | Snow load |

| Wx, Wy | Wind load in X and Y directions |

| Ex, Ey | Seismic load in X and Y directions |

| Fy | Yield strength of steel |

| Fu | Ultimate tensile strength |

| E | Modulus of elasticity |

| Ag | Gross cross-sectional area |

| Iy, Ix | Moment of inertia about y and x axes |

| r | Radius of gyration |

| KL | Effective buckling length |

| λc | Nondimensional slenderness parameter |

| Fcr | Critical buckling stress |

| Pn | Nominal axial compressive capacity |

| ϕPn | Design axial compressive strength (factored) |

| Pu | Applied axial force from analysis |

| Pcr | Euler elastic buckling load |

| Mu | Applied bending moment |

| Vu | Applied shear force |

| θ | Roof slope (in degrees) |

| Ct | Topographic amplification coefficient (TBEC 2018) |

| ε | Strain |

| σ | Stress |

| u | Lateral displacement |

| Δ | Interstory drift and mid-span displacement |

| P–Δ | Geometric nonlinearity effect |

| LRFD | Load and Resistance Factor Design method |

| IR | İnteraction Ratio |

| LTB | Lateral-torsional buckling |

References

- Aral, M.; Tunç, G. Studies and recommendations for establishing building identification information based on earthquake performance in Turkey. Disaster Risk J. 2021, 4, 20–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ekinci, N.; İpek, C. The main reasons for collapsed buildings in the Kahramanmaraş earthquakes. In Proceedings of the ASES II. International Disaster Congress, Kahramanmaraş, Türkiye, 26–27 August 2023. Congress Imprint. [Google Scholar]

- Eren, Ö. Large-Span Steel Structures; Arı Sanat Publications: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2014; pp. 111–112. [Google Scholar]

- Güler, B. Structural Steel Production-Organization-Application in Turkish Construction Industry. Master’s Thesis, Istanbul Kültür University, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- İrban, M.Y.; Fenkli, M. Sustainability in steel prefabricated structures. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. Technol. 2022, 6, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz, Y. Reflections of Social Change and Steel Construction Material Interaction on Architectural Design. Master’s Thesis, Konya Technical University, Konya, Türkiye, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meistermann, A. Step by Step/Load-Bearing Systems; Construction-Industry Center Publications: Birkhäuser, Basel, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ünver, H. Analysis of Steel Structure Details in Terms of Load-Bearing Systems. Master’s Thesis, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Akdumanlar, E. Steel Structure Design and Construction Problems in Turkey. Master’s Thesis, Yıldız Technical University, Beşiktaş, Türkiye, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Çelebi, N.G.; Arpacioğlu, Ü. Analyzing Steel and Reinforced Concrete Frame Structures in the Context of Earthquake and Environmental Impact. In Proceedings of the ACADEMY 1st International Conference on Earthquake Studies, İstanbul, Türkiye, 21 May 2023; Conference Book. p. 434. [Google Scholar]

- TBEC. Turkish Building Earthquake Code-2018; Rebublic of Türkiye Minister of Environment, Urbanisation and Climate Change: Ankara, Türkiye, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, Y.; Cumhur, A. Investigation of seismic performance of risky reinforced concrete buildings using Canadian seismic scanning method: Yalova example. In Proceedings of the ASES II. International Disaster Congress, Kahramanmaraş, Türkiye, 26–27 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ghannam, M.; Mahmoud, N.S.; Badr, A.; Salem, F.A. Numerical analysis for strengthening steel trusses using post tensioned cables. Glob. J. Res. Eng. 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Granello, G.; Leyder, C.; Palermo, A.; Frangi, A.; Pampanin, S. Design approach to predict post-tensioning losses in post-tensioned timber frames. J. Struct. Eng. 2018, 144, 04018115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu-Qing, S.; Xinjie, L.; Weilong, C.; Shilian, Z.; Qingbo, W.; Junqi, W.; Yajun, X.; Shuliang, C. Study on reinforcement effect of H-type assembled anchoring joint in portal frame. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2021, 24, 1883–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.J.; Ridge, I.M.L. Rope and rope-like structures. In WIT Transactions on State-of-the-Art in Science and Engineering; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2005; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Y.; Wu, J.; Wu, Q.; Cui, W.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, S. Study on the sickle anchoring joint in external prestressing strengthening of portal frame. Structures 2020, 28, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinnejad, H.; Lotfollahi-Yaghin, M.; Hosseinzadeh, Y.; Maleki, A. Numerical investigation of response of the post-tensioned tapered steel beams with shape memory alloy tendons. Int. J. Eng. 2021, 34, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücekul, N.K. Strengthening of Steel Truss Systems with Post-Tensioned Cables. Master’s Thesis, Ege University, Izmir, Türkiye, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ghannam, M.; Mahmoud, N.S.; Badr, A.; Salem, F.A. Effect of post tensioning on strengthening different types of steel frames. J. King Saud Univ.-Eng. Sci. 2017, 29, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlock, M.M.; Ricles, J.M.; Sause, R.; Zhao, C.; Lu, L.W. Seismic behavior of post-tensioned steel frames. In STESSA 2000: Behaviour of Steel Structures in Seismic Areas; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 593–599. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, C.; Xin, Y. Research on prestressed loading strut of cable supported portal frame. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAP2000, C.S.I. Analysis Reference Manual, Structural Analysis Program, Version 25.0.0; Computers and Structures, Inc.: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016.

- ANSI/AISC 360-16; Specification for Structural Steel Buildings. American Institute of Steel Construction: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016.

- Anonim. Steel Rope Products Promotion Site. Available online: https://www.celikhalat.com.tr/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- TS EN 1991-1-3; Eurocode 1—Actions on Structures—Part 1–3: Snow Loads. Turkish Standards Institution: Ankara, Türkiye, 2025.

- TS EN 1991-1-4; Eurocode 1—Actions on Structures—Part 1–4: General Actions—Wind Actions. Turkish Standards Institution: Ankara, Türkiye, 2022.

- AFAD. Türkiye Earthquake Hazard Maps Interactive Web Application; Republic of Turkey Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency: Ankara, Turkey, 2020. Available online: https://tdth.afad.gov.tr/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- SSDCR. Steel Structures Design, Calculation and Construction Regulation; Ministry of Environment and Urbanisation: Ankara, Türkiye, 2016.

- Timoshenko, S.P.; Gere, J.M. Theory of Elastic Stability, 2nd ed.; McGraw–Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).