Timing of Deformation in the Provence Fold-and-Thrust Belt (SE France) as Constrained by U-Pb Calcite Geochronology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

2.1. Meso-Cenozoic Tectonic History of Provence

2.2. Tectonic Style of Deformation of Provence

2.3. Meso-Cenozoic Sedimentary Succession of Provence

2.4. The Studied Structures

2.4.1. The Nerthe Range

2.4.2. The Bimont Lake Area

2.4.3. The Rians Basin

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Strategy and Material

3.2. Analysis of Fractures and Stylolites

3.3. Inversion of Fault–Slip Data for Tectonic Paleostress

3.4. Inversion of Calcite Twin Data for Tectonic Paleostress

3.5. U-Pb Calcite Geochronology

4. Results

4.1. Orientations of Fractures, Stylolites, and Faults

4.1.1. The Nerthe Range

4.1.2. The Bimont Lake Area

4.1.3. The Rians Basin

4.2. Petrographic Observations

4.3. Paleostress Orientations from Calcite Twin Inversion

| Sample | Vein Set | Site | Nb Grains | Grain Size | Nb TP/UTP | Tensor | % Comp. TP | Sigma 1 | Sigma 2 | Sigma 3 | Penal. Funct. | Stress Ratio | Min RSS | Nb Incomp. UTP | Nb Comp. TP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tr | Pl | Tr | Pl | Tr | Pl | |||||||||||||

| Z075-2 | JB-B | 16B | 79 | 500–1100 | 193/44 | B1 | 52 | 192 | 68 | 360 | 21 | 91 | 4 | 0.73 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 9 | 100 |

| B2 | 54 | 178 | 71 | 54 | 11 | 321 | 16 | 0.72 | 0.29 | 0.02 | 9 | 104 | ||||||

| 359 | 18 | 103 | 36 | 246 | 49 | |||||||||||||

| Z079-2 | JB-A | 16B | 68 | 400–800 | 196/74 | B3 | 42 | 238 | 41 | 148 | 1 | 57 | 49 | 1.02 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 12 | 82 |

| 44 | 23 | 274 | 58 | 144 | 22 | |||||||||||||

| B4 | 40 | 204 | 11 | 301 | 33 | 97 | 55 | 0.98 | 0.58 | 0.19 | 11 | 78 | ||||||

| Z088 | JN-E | 1N | 42 | 250–450 | 97/44 | N6 | 56 | 33 | 42 | 193 | 46 | 294 | 11 | 1.53 | 0.81 | 0.06 | 9 | 54 |

| 26 | 4 | 238 | 86 | 107 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| N7 | 46 | 181 | 13 | 47 | 71 | 274 | 13 | 0.45 | 0.71 | 0.17 | 8 | 44 | ||||||

| Z101 | JN-D | 3N | 72 | 400–1000 | 125/34 | N5 | 58 | 312 | 14 | 49 | 27 | 197 | 59 | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 8 | 72 |

| N4 | 50 | 132 | 64 | 285 | 23 | 20 | 10 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.08 | 8 | 62 | ||||||

| 51 | 69 | 293 | 10 | 201 | 19 | |||||||||||||

| Z135 | JN-B | 8N | 75 | 500–1150 | 180/36 | N2 | 42 | 193 | 30 | 88 | 24 | 326 | 50 | 1.10 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 11 | 75 |

| 11 | 21 | 107 | 13 | 225 | 65 | |||||||||||||

| N3 | 40 | 322 | 10 | 97 | 76 | 230 | 10 | 0.97 | 0.42 | 0.12 | 11 | 72 | ||||||

| N1 | 46 | 233 | 36 | 338 | 19 | 90 | 48 | 0.92 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 9 | 82 | ||||||

| 218 | 0 | 310 | 66 | 129 | 24 | |||||||||||||

| Z142 | JN-A | 9N | 19 | 1400–2600 | 50/10 | N1 | 50 | 41 | 14 | 309 | 5 | 200 | 76 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 4 | 25 |

| 52 | 22 | 303 | 37 | 165 | 45 | |||||||||||||

4.4. U-Pb Ages of Deformation

4.4.1. The Nerthe Range

4.4.2. The Bimont Lake Area

4.4.3. The Rians Basin

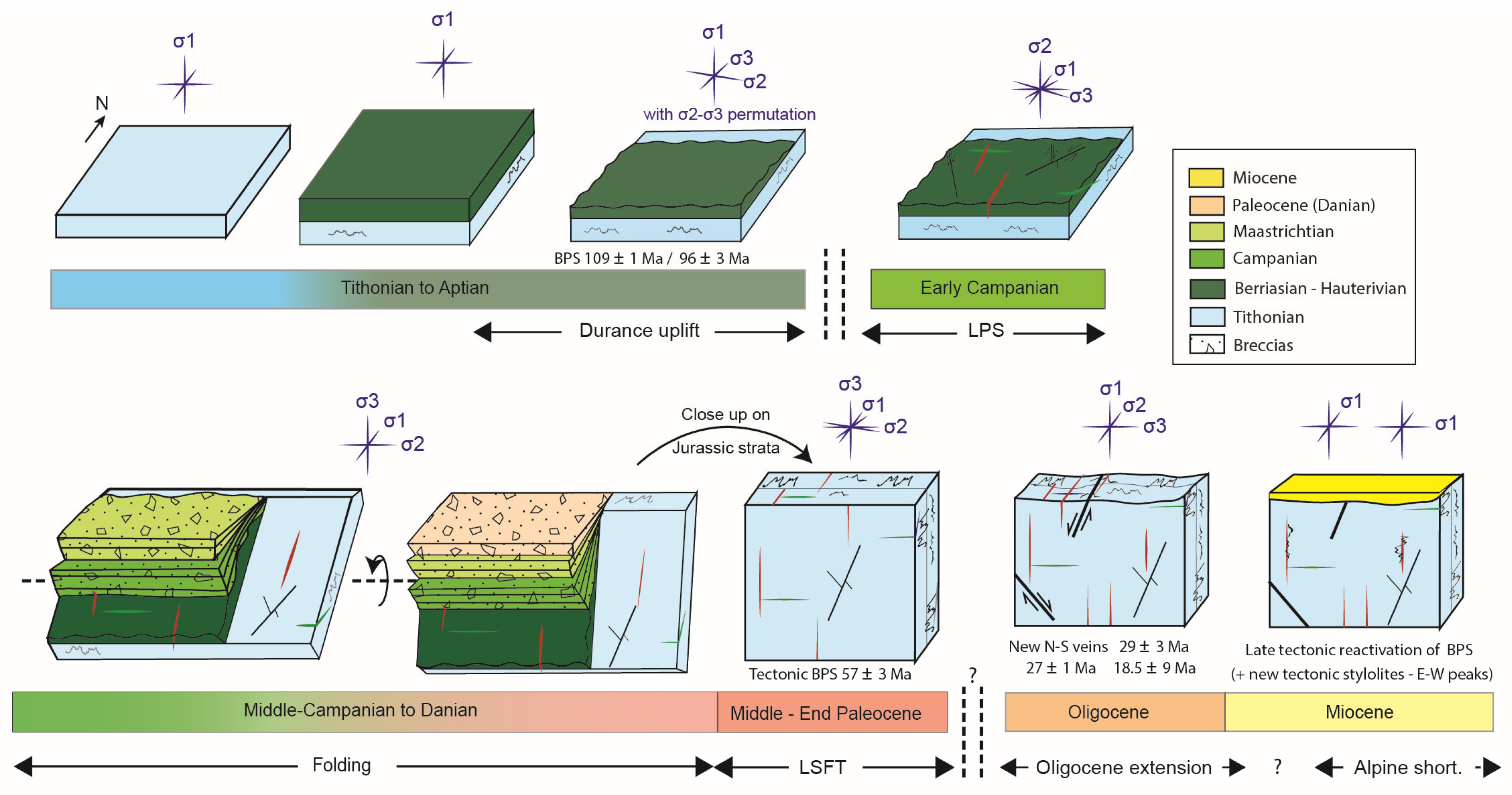

5. Interpretation of Results: Timing of Deformation and Paleostress Evolution

5.1. Sequence of Deformation in the Nerthe Range

5.1.1. Pre-Pyrenean Extension (Albian-Cenomanian, 110–93 Ma)

5.1.2. Pyrenean Compression (81–67 and 59–34 Ma)

5.1.3. Post-Pyrenean Extension (Oligo–Miocene, 33–20 Ma)

5.1.4. Post-Pyrenean (Miocene?) Compression

5.2. Sequence of Deformation in the Bimont Lake Area

5.2.1. Pre-Pyrenean Extension (Albian–Cenomanian, 110–93 Ma)

5.2.2. Pyrenean Compression (71–33 Ma)

5.2.3. Post-Pyrenean Extension (Oligocene, 33–23 Ma)

5.2.4. Post-Pyrenean Alpine Compression (Miocene, 15?—? Ma)

5.3. Sequence of Deformation in the Rians Basin

6. Discussion

6.1. Unlocking > 90 My of Complex Compressional and Extensional Deformation in Provence

6.2. Timing and Evolution of the Pyrenean–Provençal Shortening

6.3. Lessons from Applying U-Pb Calcite Geochronology at Multiple Structural Scales

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lacombe, O.; Beaudoin, N.E. Timing, Sequence, Duration and Rate of Deformation in Fold-and-Thrust Belts: A Review of Traditional Approaches and Recent Advances from Absolute Dating (K–Ar Illite/U–Pb Calcite) of Brittle Structures. Comptes Rendus Géosci. 2024, 356, 467–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuriel, P.; Rosenbaum, G.; Zhao, J.-X.; Feng, Y.; Golding, S.D.; Villemant, B.; Weinberger, R. U-Th Dating of Striated Fault Planes. Geology 2012, 40, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuriel, P.; Weinberger, R.; Kylander, A. Dating Terrestrial Sediments by in Situ U-Pb Dating of Carbonates. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth Annual Goldschmidt Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 18–23 August 2019; p. 2474. [Google Scholar]

- Tillberg, M.; Drake, H.; Zack, T.; Kooijman, E.; Whitehouse, M.J.; Åström, M.E. In Situ Rb-Sr Dating of Slickenfibres in Deep Crystalline Basement Faults. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Pluijm, B.A.; Hall, C.M.; Vrolijk, P.J.; Pevear, D.R.; Covey, M.C. The Dating of Shallow Faults in the Earth’s Crust. Nature 2001, 412, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwingmann, H.; Mancktelow, N. Timing of Alpine Fault Gouges. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2004, 223, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, S.H.; Van Der Pluijm, B.A. Clay Quantification and Ar–Ar Dating of Synthetic and Natural Gouge: Application to the Miocene Sierra Mazatán Detachment Fault, Sonora, Mexico. J. Struct. Geol. 2008, 30, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvall, A.R.; Clark, M.K.; Van Der Pluijm, B.A.; Li, C. Direct Dating of Eocene Reverse Faulting in Northeastern Tibet Using Ar-Dating of Fault Clays and Low-Temperature Thermochronometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 304, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, G.; Torgersen, E.; Mazzarini, F.; Musumeci, G.; van der Lelij, R.; Schönenberger, J.; Garofalo, P.S. New Constraints on the Evolution of the Inner Northern Apennines by K-Ar Dating of Late Miocene-Early Pliocene Compression on the Island of Elba, Italy. Tectonics 2018, 37, 3229–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrolijk, P.; Pevear, D.; Covey, M.; LaRiviere, A. Fault Gouge Dating: History and Evolution. Clay Miner. 2018, 53, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.M.W.; Walker, R.J. U-Pb Geochronology of Calcite-Mineralized Faults: Absolute Timing of Rift-Related Fault Events on the Northeast Atlantic Margin. Geology 2016, 44, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.M.W.; Rasbury, E.T.; Parrish, R.R.; Smith, C.J.; Horstwood, M.S.A.; Condon, D.J. A Calcite Reference Material for LA-ICP-MS U-Pb Geochronology. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2017, 18, 2807–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergbauer, S.; Pollard, D.D. A New Conceptual Fold-Fracture Model Including Prefolding Joints, Based on the Emigrant Gap Anticline, Wyoming. Geo. Soc. Am. Bull. 2004, 116, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavani, S.; Storti, F.; Lacombe, O.; Corradetti, A.; Muñoz, J.A.; Mazzoli, S. A Review of Deformation Pattern Templates in Foreland Basin Systems and Fold-and-Thrust Belts: Implications for the State of Stress in the Frontal Regions of Thrust Wedges. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2015, 141, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O.; Beaudoin, N.E.; Hoareau, G.; Labeur, A.; Pecheyran, C.; Callot, J.-P. Dating Folding beyond Folding, from Layer-Parallel Shortening to Fold Tightening, Using Mesostructures: Lessons from the Apennines, Pyrenees, and Rocky Mountains. Solid Earth 2021, 12, 2145–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, N.; Lacombe, O.; Roberts, N.M.W.; Koehn, D. U-Pb Dating of Calcite Veins Reveals Complex Stress Evolution and Thrust Sequence in the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming, USA. Geology 2018, 46, 1015–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeboudj, A.; Lacombe, O.; Beaudoin, N.E.; Callot, J.-P.; Lamarche, J.; Guihou, A.; Hoareau, G. Sequence, Duration, Rate of Deformation and Paleostress Evolution during Fold Development: Insights from Fractures, Calcite Twins and U-Pb Calcite Geochronology in the Mirabeau Anticline (SE France). J. Struct. Geol. 2025, 199, 105460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, N.E.; Labeur, A.; Lacombe, O.; Koehn, D.; Billi, A.; Hoareau, G.; Boyce, A.; John, C.M.; Marchegiano, M.; Roberts, N.M.; et al. Regional-Scale Paleofluid System across the Tuscan Nappe–Umbria–Marche Apennine Ridge (Northern Apennines) as Revealed by Mesostructural and Isotopic Analyses of Stylolite–Vein Networks. Solid Earth 2020, 11, 1617–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, B.W.; Viola, G.; Bingen, B.; Nuriel, P.; Kylander-Clark, A.R.C. Palaeocene Faulting in SE Sweden from U–Pb Dating of Slickenfibre Calcite. Terra Nova 2017, 29, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansman, R.J.; Albert, R.; Gerdes, A.; Ring, U. Absolute Ages of Multiple Generations of Brittle Structures by U-Pb Dating of Calcite. Geology 2018, 46, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullien-Sicre, A.; Missenard, Y.; Blaise, T.; Augier, R.; Parizot, O.; Haurine, F. Timing of Contractional Stress Propagation, From the Pyrenean Orogen to the Intraplate Domain, Evidenced by U-Pb Dating of Syn-Kinematic Calcite. Tectonics 2025, 44, e2024TC008634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizot, O.; Missenard, Y.; Vergely, P.; Haurine, F.; Noret, A.; Delpech, G.; Barbarand, J.; Sarda, P. Tectonic Record of Deformation in Intraplate Domains: Case Study of Far-Field Deformation in the Grands Causses Area, France. Geofluids 2020, 2020, 7598137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizot, O.; Missenard, Y.; Haurine, F.; Blaise, T.; Barbarand, J.; Benedicto, A.; Sarda, P. When Did the Pyrenean Shortening End? Insight from U–Pb Geochronology of Syn-Faulting Calcite (Corbières Area, France). Terra Nova 2021, 33, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, R.R.; Parrish, C.M.; Lasalle, S. Vein Calcite Dating Reveals Pyrenean Orogen as Cause of Paleogene Deformation in Southern England. J. Geol. Soc. 2018, 175, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruset, D.; Vergés, J.; Albert, R.; Gerdes, A.; Benedicto, A.; Cantarero, I.; Travé, A. Quantifying Deformation Processes in the SE Pyrenees Using U–Pb Dating of Fracture-Filling Calcites. J. Geol. Soc. 2020, 177, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.-Y.; Zhao, J.-X.; Feng, Y.-X.; Hofstra, A.H.; Deng, X.-D.; Zhao, X.-F.; Li, J.-W. Calcite U-Pb Dating Unravels the Age and Hydrothermal History of the Giant Shuiyindong Carlin-type Gold Deposit in the Golden Triangle, South China. Econ. Geol. 2021, 116, 1253–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, M.; Zanchetta, S.; Gasparrini, M.; Mangenot, X.; Berra, F.; Deschamps, P.; Guihou, A.; Zanchi, A. U-Pb Carbonate Dating Reveals Long-Lived Activity of Proximal Margin Extensional Faults during the Alpine Tethys Rifting. Terra Nova 2024, 36, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigdefàbregas, C.; Souquet, P. Tecto-Sedimentary Cycles and Depositional Sequences of the Mesozoic and Tertiary from the Pyrenees. Tectonophysics 1986, 129, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séranne, M.; Benedicto, A.; Labaum, P.; Truffert, C.; Pascal, G. Structural Style and Evolution of the Gulf of Lion Oligo-Miocene Rifting: Role of the Pyrenean Orogeny. Mar. Pet. Geol. 1995, 12, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grool, A.R.; Ford, M.; Vergés, J.; Huismans, R.S.; Christophoul, F.; Dielforder, A. Insights Into the Crustal-Scale Dynamics of a Doubly Vergent Orogen From a Quantitative Analysis of Its Forelands: A Case Study of the Eastern Pyrenees. Tectonics 2018, 37, 450–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieu, S.; Saspiturry, N.; Lartigau, M.; Issautier, B.; Angrand, P.; Lasseur, E. Large-Scale Vertical Movements in Cenomanian to Santonian Carbonate Platform in Iberia: Indicators of a Coniacian Pre-Orogenic Compressive Stress. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 2021, 192, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoareau, G.; Crognier, N.; Lacroix, B.; Aubourg, C.; Roberts, N.M.W.; Niemi, N.; Branellec, M.; Beaudoin, N.; Suárez Ruiz, I. Combination of Δ47 and U-Pb Dating in Tectonic Calcite Veins Unravel the Last Pulses Related to the Pyrenean Shortening (Spain). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2021, 553, 116636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouthereau, F.; Filleaudeau, P.-Y.; Vacherat, A.; Pik, R.; Lacombe, O.; Fellin, M.G.; Castelltort, S.; Christophoul, F.; Masini, E. Placing Limits to Shortening Evolution in the Pyrenees: Role of Margin Architecture and Implications for the Iberia/Europe Convergence. Tectonics 2014, 33, 2283–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchiavelli, C.; Vergés, J.; Schettino, A.; Fernàndez, M.; Turco, E.; Casciello, E.; Torne, M.; Pierantoni, P.P.; Tunini, L. A New Southern North Atlantic Isochron Map: Insights Into the Drift of the Iberian Plate Since the Late Cretaceous. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2017, 122, 9603–9626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dielforder, A.; Frasca, G.; Brune, S.; Ford, M. Formation of the Iberian-European Convergent Plate Boundary Fault and Its Effect on Intraplate Deformation in Central Europe. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2019, 20, 2395–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, M.; Masini, E.; Vergés, J.; Pik, R.; Ternois, S.; Léger, J.; Dielforder, A.; Frasca, G.; Grool, A.; Vinciguerra, C.; et al. Evolution of a Low Convergence Collisional Orogen: A Review of Pyrenean Orogenesis. BSGF-Earth Sci. Bull. 2022, 193, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrand, P.; Mouthereau, F. Evolution of the Alpine Orogenic Belts in the Western Mediterranean Region as Resolved by the Kinematics of the Europe-Africa Diffuse Plate Boundary. BSGF-Earth Sci. Bull. 2021, 192, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-López, D.; Cruset, D.; Vergés, J.; Cantarero, I.; Benedicto, A.; Mangenot, X.; Albert, R.; Gerdes, A.; Beranoaguirre, A.; Travé, A. Spatio-Temporal Variation of Fluid Flow Behavior along a Fold: The Bóixols-Sant Corneli Anticline (Southern Pyrenees) from U–Pb Dating and Structural, Petrographic and Geochemical Constraints. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 143, 105788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balansa, J.; Espurt, N.; Hippolyte, J.-C.; Philip, J.; Caritg, S. Structural Evolution of the Superimposed Provençal and Subalpine Fold-Thrust Belts (SE France). Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 227, 103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestani, L.; Espurt, N.; Lamarche, J.; Bellier, O.; Hollender, F. Reconstruction of the Provence Chain Evolution, Southeastern France. Tectonics 2016, 35, 1506–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippolyte, J.-C.; Angelier, J.; Bergerat, F.; Nury, D.; Guieu, G. Tectonic-Stratigraphic Record of Paleostress Time Changes in the Oligocene Basins of the Provence, Southern France. Tectonophysics 1993, 226, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molliex, S. Caractérisation de la Déformation Tectonique Récente en Provence (SE France). Ph.D. Thesis, Université Paul Cézanne-Aix-Marseille III, Marseille, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tempier, C. Modèle Nouveau de Mise en Place des Structures Provencales. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 1987, III, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilau, A.; Rolland, Y.; Dumont, T.; Schwartz, S.; Godeau, N.; Guihou, A.; Deschamps, P. Early Onset of Pyrenean Collision (97–90 Ma) Evidenced by U–Pb Dating on Calcite (Provence, SE France). Terra Nova 2023, 35, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, R.S.M.; Ukar, E.; Laubach, S.E.; Aubert, I.; Lamarche, J.; Wang, Q.; Stockli, D.F.; Stockli, L.D.; Larson, T.E. Episodic Reactivation of Carbonate Fault Zones with Implications for Permeability—An Example from Provence, Southeast France. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 145, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O.; Jolivet, L. Structural and Kinematic Relationships between Corsica and the Pyrenees-Provence Domain at the Time of the Pyrenean Orogeny. Tectonics 2005, 24, TC1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espurt, N.; Hippolyte, J.-C.; Saillard, M.; Bellier, O. Geometry and Kinematic Evolution of a Long-Living Foreland Structure Inferred from Field Data and Cross Section Balancing, the Sainte-Victoire System, Provence, France. Tectonics 2012, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dercourt, J.; Gaetani, M.; Vrielynck, B. Atlas Peri-Tethys Palaeogeographical Maps; CCGM: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Masse, J.; Philip, J. Paléogéographie et Tectonique du Crétacé Moyen en Provence: Révision du Concept d’isthme Durancien. Rev. De Géographie Phys. Et De Géologie Dyn. 1976, 18, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Guyonnet-Benaize, C.; Lamarche, J.; Masse, J.-P.; Villeneuve, M.; Viseur, S. 3D Structural Modelling of Small-Deformations in Poly-Phase Faults Pattern. Application to the Mid-Cretaceous Durance Uplift, Provence (SE France). J. Geodyn. 2010, 50, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergerat, F. Stress Fields in the European Platform at the Time of Africa-Eurasia Collision. Tectonics 1987, 6, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaviglio, P.; Gonzales, J.F. Fracturation et Histoire Tectonique Du Bassin de Gardanne (Bouches-Du-Rhone). Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 1987, III, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O.; Angelier, J.; Laurent, P. Determining Paleostress Orientations from Faults and Calcite Twins: A Case Study near the Sainte-Victoire Range (Southern France). Tectonophysics 1992, 201, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavani, S.; Bertok, C.; Granado, P.; Piana, F.; Salas, R.; Vigna, B.; Muñoz, J.A. The Iberia-Eurasia Plate Boundary East of the Pyrenees. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 187, 314–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyonnet-Benaize, C. Modélisation 3D Multi-Échelle des Structures Géologiques de la Région de la Faille de la Moyenne Durance (SE France). Ph.D. Thesis, Université Aix-Marseille, Marseille, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aubert, I.; Léonide, P.; Lamarche, J.; Salardon, R. Diagenetic Evolution of Fault Zones in Urgonian Microporous Carbonates, Impact on Reservoir Properties (Provence—Southeast France). Solid Earth 2020, 11, 1163–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondillo, N.; Chelle-Michou, C.; Putzolu, F.; Balassone, G.; Mormone, A.; Santoro, L.; Cretella, S.; Scognamiglio, G.; Tarallo, M.; Tavani, S. The Mid-Cretaceous Bauxites of SE France: Geochemistry, U-Pb Zircon Dating and Their Implications for the Paleogeography at the Junction between Alpine Tethys and Pyrenean Rift. Gondwana Res. 2025, 137, 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dercourt, J.; Zonenshain, L.P.; Ricou, L.-E.; Kazmin, V.G.; Le Pichon, X.; Knipper, A.L.; Grandjacquet, C.; Sbortshikov, I.M.; Geyssant, J.; Lepvrier, C.; et al. Geological Evolution of the Tethys Belt from the Atlantic to the Pamirs since the LIAS. Tectonophysics 1986, 123, 241–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advokaat, E.L.; van Hinsbergen, D.J.J.; Maffione, M.; Langereis, C.G.; Vissers, R.L.M.; Cherchi, A.; Schroeder, R.; Madani, H.; Columbu, S. Eocene Rotation of Sardinia, and the Paleogeography of the Western Mediterranean Region. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2014, 401, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthaud, F.; Seguret, M. Les Structures Pyrénéennes du Languedoc et du Golfe du Lion (Sud de La France). Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 1981, S7-XXIII, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hinsbergen, D.J.J.; Torsvik, T.H.; Schmid, S.M.; Maţenco, L.C.; Maffione, M.; Vissers, R.L.M.; Gürer, D.; Spakman, W. Orogenic Architecture of the Mediterranean Region and Kinematic Reconstruction of Its Tectonic Evolution since the Triassic. Gondwana Res. 2020, 81, 79–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivet, J.-L. La Cinématique de la Plaque Ibérique. Bull. Des Cent. De Rech. Explor.-Prod. Elf-Aquitaine 1996, 20, 131–195. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, G.; Lister, G.; Duboz, C. Reconstruction of the Tectonic Evolution of the Western Mediterranean since the Oligocene. J. Virtual Explor. 2002, 8, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schettino, A.; Turco, E. Tectonic History of the Western Tethys since the Late Triassic. GSA Bull. 2011, 123, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergés, J.; Marzo, M.; Muñoz, J.A. Growth Strata in Foreland Settings. Sediment. Geol. 2002, 146, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreani, L.; Loget, N.; Rangin, C.; Le Pichon, X. New Structural Constraints on the Southern Provence Thrust Belt (France): Evidences for an Eocene Shortening Event Linked to the Corsica-Sardinia Subduction. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 2010, 181, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, C.; Choukroune, P.; Clauzon, G. La Déformation Post-Miocène en Provence Occidentale. Geodin. Acta 2000, 13, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corroy, G. La Montagne Sainte-Victoire. Bull. Du Serv. De La Cart. Géologique De Fr. 1957, 55, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Guieu, G. Un Exemple de Tectonique Tangentielle; l’évolution du Cadre Montagneux de Marseille. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 1967, S7-IX, 610–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempier, C.; Durand, J. Importance de l’épisode Tectonique d’âge Crétacé Supérieur dans la Structure du Versant Méridional de la Montagne Sainte-Victoire (Provence). C.R. Acad. Sci. 1981, 293, 629–632. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, P.G.; Muñoz, J.A.; Coney, P.J.; Baldwin, S.L. Asymmetric Exhumation across the Pyrenean Orogen: Implications for the Tectonic Evolution of a Collisional Orogen. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1999, 173, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavenu, A.P.C.; Lamarche, J.; Gallois, A.; Gauthier, B.D.M. Tectonic versus Diagenetic Origin of Fractures in a Naturally Fractured Carbonate Reservoir Analog (Nerthe Anticline, Southeastern France). AAPG Bull. 2013, 97, 2207–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, V.; Ford, M. Assessment of the Tectonic Role of the Triassic Evaporites in the North Toulon Fold-Thrust Belt. BSGF-Earth Sci. Bull. 2021, 192, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roure, F.; Colletta, B. Cenozoic Inversion Structures in the Foreland of the Pyrenees and Alps. Mémoires Du Muséum Natl. D’histoire Nat. 1996, 170, 173–209. [Google Scholar]

- Le Pichon, X.; Bergerat, F.; Roulet, M.-J. Plate Kinematics and Tectonics Leading to the Alpine Belt Formation; A New Analysis. In Processes in Continental Lithospheric Deformation; Clark, S.P., Jr., Burchfiel, B.C., Suppe, J., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1988; pp. 111–131. ISBN 978-0-8137-2218-4. [Google Scholar]

- Merle, O.; Michon, L. The Formation of the West European Rift; a New Model as Exemplified by the Massif Central Area. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 2001, 172, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherchi, A.; Mancin, N.; Montadert, L.; Murru, M.; Putzu, M.T.; Schiavinotto, F.; Verrubbi, V. The Stratigraphic Response to the Oligo-Miocene Extension in the Western Mediterranean from Observations on the Sardinia Graben System (Italy). Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 2008, 179, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccenna, C.; Mattei, M.; Funiciello, R.; Jolivet, L. Styles of Back-Arc Extension in the Central Mediterranean. Terra Nova 1997, 9, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattacceca, J.; Deino, A.; Rizzo, R.; Jones, D.S.; Henry, B.; Beaudoin, B.; Vadeboin, F. Miocene Rotation of Sardinia: New Paleomagnetic and Geochronological Constraints and Geodynamic Implications. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2007, 258, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueguen, E.; Doglioni, C.; Fernandez, M. On the Post-25 Ma Geodynamic Evolution of the Western Mediterranean. Tectonophysics 1998, 298, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccenna, C.; Jolivet, L.; Piromallo, C.; Morelli, A. Subduction and the Depth of Convection in the Mediterranean Mantle. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2003, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestani, L. Géométrie et Cinématique de l’Avant-Pays Provençal: Modélisation par Coupes Équilibrées dans une Zone à Tectonique Polyphasée. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Aix-Marseille, Marseille, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hemelsdaël, R.; Séranne, M.; Husson, E.; Ballas, G. Structural Style of the Languedoc Pyrenean Thrust Belt in Relation with the Inherited Mesozoic Structures and with the Rifting of the Gulf of Lion Margin, Southern France. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 2021, 192, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séranne, M. The Gulf of Lion Continental Margin (NW Mediterranean) Revisited by IBS: An Overview. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1999, 156, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séranne, M.; Couëffé, R.; Husson, E.; Baral, C.; Villard, J. The Transition from Pyrenean Shortening to Gulf of Lion Rifting in Languedoc (South France) – A Tectonic-Sedimentation Analysis. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 2021, 192, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molliex, S.; Bellier, O.; Terrier, M.; Lamarche, J.; Martelet, G.; Espurt, N. Tectonic and Sedimentary Inheritance on the Structural Framework of Provence (SE France): Importance of the Salon-Cavaillon Fault. Tectonophysics 2011, 501, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauzon, G.; Fleury, T.-J.; Bellier, O.; Molliex, S.; Mocochain, L.; Aguilar, J.-P. Morphostructural Evolution of the Luberon since the Miocene (SE France). Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 2011, 182, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroux, E. Tectonique Active en Région à Sismicité Modérée: Le Cas de la Provence (France): Apport d’une Approche Pluridisciplinaire. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Paris, Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Combes, P. La tectonique récente de la Provence Occidentale Microtectonique, Caractéristiques Dynamiques et Cinématiques: Méthodologie de Zonation Tectonique et Relations Avec la Séismicité. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Guignard, P.; Bellier, O.; Chardon, D. Géométrie et cinématique post-oligocène des failles d’Aix et de la moyenne Durance (Provence, France). Comptes Rendus Geosci. 2005, 337, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyonnet-Benaize, C.; Lamarche, J.; Hollender, F.; Viseur, S.; Münch, P.; Borgomano, J. Three-Dimensional Structural Modeling of an Active Fault Zone Based on Complex Outcrop and Subsurface Data: The Middle Durance Fault Zone Inherited from Polyphase Meso-Cenozoic Tectonics (Southeastern France). Tectonics 2015, 34, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarche, J.; Lavenu, A.P.C.; Gauthier, B.D.M. How Far Facies and Diagenesis Control Fractures in Carbonates. In Second EAGE Workshop on Naturally Fractured Reservoirs; European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers (EAGE): Houten, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe, O.; Mouthereau, F. Basement-Involved Shortening and Deep Detachment Tectonics in Forelands of Orogens: Insights from Recent Collision Belts (Taiwan, Western Alps, Pyrenees). Tectonics 2002, 21, 12-1–12-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthaud, F.; Matte, P. Les Décrochements Tardi-Hercyniens du Sud-Ouest de l’Europe. Géométrie et Essai de Reconstitution des Conditions de la Déformation. Tectonophysics 1975, 25, 139–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthaud, F.; Matte, P. Détermination de la Position Initiale de la Corse et de la Sardaigne à la Fin de l’orogénèse Hercynienne grâce aux Marqueurs Géologiques Anté-Mesozoiques. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 1977, S7-XIX, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushing, E.M.; Bellier, O.; Nechtschein, S.; Sébrier, M.; Lomax, A.; Volant, P.; Dervin, P.; Guignard, P.; Bove, L. A Multidisciplinary Study of a Slow-Slipping Fault for Seismic Hazard Assessment: The Example of the Middle Durance Fault (SE France). Geophys. J. Int. 2008, 172, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestani, L.; Espurt, N.; Lamarche, J.; Floquet, M.; Philip, J.; Bellier, O.; Hollender, F. Structural Style and Evolution of the Pyrenean-Provence Thrust Belt, SE France. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 2015, 186, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espurt, N.; Wattellier, F.; Philip, J.; Hippolyte, J.-C.; Bellier, O.; Bestani, L. Mesozoic Halokinesis and Basement Inheritance in the Eastern Provence Fold-Thrust Belt, SE France. Tectonophysics 2019, 766, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennessier, G. Étude Tectonique du Massif de Bras (Var) et Description Détaillée des Synclinaux Bauxitifères à Partir des Travaux Miniers (Feuilles de Draguignan et de Brignoles à 1:50000); BRGM: Orléans, France, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, J.; Masse, J.L.; Machhour, L. L’Evolution Paleogeographique et Structurale du Front de Chevauchement Nord-Toulonnais (Basse-Provence Occidentale, France). Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 1987, III, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelier, J.; Aubouin, J. Contribution à l’Etude Géologique des Bandes Triasiques Provençales de Barjols (Var) Au Bas Verdon. Bull. du BRGM 1976, 3, 187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Célini, N.; Callot, J.-P.; Ringenbach, J.-C.; Graham, R. Jurassic Salt Tectonics in the SW Sub-Alpine Fold-and-Thrust Belt. Tectonics 2020, 39, e2020TC006107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léonide, P.; Floquet, M.; Villier, L. Interaction of Tectonics, Eustasy, Climate and Carbonate Production on the Sedimentary Evolution of an Early/Middle Jurassic Extensional Basin (Southern Provence Sub-Basin, SE France). Basin Res. 2007, 19, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masse, J.-P.; Villeneuve, M.; Leonforte, E.; Nizou, J. Block Tilting of the North Provence Early Cretaceous Carbonate Margin: Stratigraphic, Sedimentologic and Tectonic Data. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 2009, 180, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, P.-J. Typologie, Cadre Géodynamique et Genèse des Bauxites Françaises. Geodin. Acta 1990, 4, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorowicz, J.; Mekarnia, A. Mise en Evidence d’une Extension Albo-Aptienne Orientée NW-SE en Provence (Sud-Est de La France). C.R. Acad. Sci. 1992, 315, 861–866. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, J. Palaeoécologie des Formations à Rudistes du Crétacé Supérieur—l’exemple du Sud-Est de la France. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1972, 12, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, D. Architecture du Bassin Rhodano-Provençal Miocène (Alpes, SE France): Relations Entre Déformation, Physiographie et Sédimentation Dans un Bassin Molassique d’Avant-Pays. Ph.D. Thesis, École Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Paris, Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clauzon, G. Sequence boundaries and geodynamic evolution. Géomorphologie Relief Process. Environ. 1996, 2, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufaure, P.; Ferrat, J.; Laumondais, A.; Mille, M. Description Sommaire d’un Sondage dans la Chaine de Martigues (Bouches-du-Rhône). Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 1969, S7-XI, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guieu, G. L’évolution Tectonique de la Chaine de la Nerthe au Nord-Ouest de Marseille. Comptes Rendus De L’Académie Des Sci. 1973, 276, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Denizot, G. Observations sur le Quaternaire Moyen de la Méditerranée Occidentale et sur la Signification du Terme de Monastirien. Bull. De La Société Geol. De Fr. 1935, 7, 559–571. [Google Scholar]

- Denizot, G. Feuille de Martigues et Extension Au 50.000ème. Bull. Du Serv. De La Cart. Géologique De Fr. 1962, 59, 247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Froget, C.; Guieu, G.; Roux, M.R. Etude Tectonique de La Region Sud de La Nerthe. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 1966, 7–VII, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guieu, G. Etude Tectonique de La Région de Marseille. Ph.D. Thesis, Aix Marseille, Marseille, France, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Guieu, G.; Froget, C.; Roux, M.R. Observations Nouvelles Sur La Structure de La Partie Sud-Ouest de La Chaîne de La Nerthe, à l’ouest de Marseille (BdR). Comptes Rendus De L’Académie Des Sci. 1964, 258, 2360–2362. [Google Scholar]

- Repelin, J. Nouvelles Observations sur sa Tectonique de la Chaine de la Nerthe. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 1900, 28, 236–263. [Google Scholar]

- Repelin, J. Observations au Sujet de la Tectonique de la Partie Occidentale de la Chaîne de la Nerthe. Comptes Rendus De L’académie Des Sci. 1933, 196, 197–198. [Google Scholar]

- Tempier, C. Les Facies Calcaires du Jurassique Provençal. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Marseille, Marseille, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Chorowicz, J.; Ruiz, R. La Sainte Victoire (Provence): Observations et Interprétations Nouvelles. Géologie De La Fr. 1984, 4, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, J.P.; Tempier, C. Etude Tectonique de la Zone des Brèches du Massif de Sainte-Victoire dans la Région du Tholonet (Bouches-du-Rhône). Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 1962, S7-IV, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guieu, G.; Philip, J.; Durand, J.-P.; Nury, D.; Redondo, C. Le détritisme provençal du Crétacé moyen à l’Oligocène dans son cadre paléogéographique, structural et géodynamique. Géologie Alp. Mémoire H.S. 1987, 13, 247. [Google Scholar]

- Delvaux, D.; Sperner, B. New Aspects of Tectonic Stress Inversion with Reference to the TENSOR Program. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2003, 212, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bons, P.D.; Elburg, M.A.; Gomez-Rivas, E. A Review of the Formation of Tectonic Veins and Their Microstructures. J. Struct. Geol. 2012, 43, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petracchini, L.; Antonellini, M.; Billi, A.; Scrocca, D. Fault Development through Fractured Pelagic Carbonates of the Cingoli Anticline, Italy: Possible Analog for Subsurface Fluid-Conductive Fractures. J. Struct. Geol. 2012, 45, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharonov, E.; Karcz, Z. How Stylolite Tips Crack Rocks. J. Struct. Geol. 2019, 118, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, N.E.; Koehn, D.; Aharonov, E.; Billi, A.; Daeron, M.; Boyce, A. Reconstruction of the Temperature Conditions of Burial-Related Pressure Solution by Clumped Isotopes Validates the Analysis of Sedimentary Stylolites Roughness as a Reliable Depth Gauge. Minerals 2025, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.B. Low-Porosity Haloes at Stylolites in the Feldspathic Upper Jurassic Ula Sandstone, Norwegian North Sea: An Integrated Petrographic and Chemical Mass-Balance Approach. J. Sediment. Res. 2006, 76, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, M.T. Stylolites in Sandstones. J. Geol. 1955, 63, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allmendinger, R.W.; Cardozo, N.; Fisher, M. Structural Geology Algorithms: Vectors and Tensors; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadhadi, F.; Daniel, J.-M.; Azzizadeh, M.; Lacombe, O. Evidence for Pre-Folding Vein Development in the Oligo-Miocene Asmari Formation in the Central Zagros Fold Belt, Iran. Tectonics 2008, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O.; Bellahsen, N.; Mouthereau, F. Fracture Patterns in the Zagros Simply Folded Belt (Fars, Iran): Constraints on Early Collisional Tectonic History and Role of Basement Faults. Geol. Mag. 2011, 148, 940–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, D.J.; Peacock, D.C.P.; Nixon, C.W. Fracture Sets and Sequencing. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 257, 104888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, D.D.; Aydin, A. Progress in Understanding Jointing over the Past Century. GSA Bull. 1988, 100, 1181–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, D.; Renard, F.; Toussaint, R.; Passchier, C. Growth of Stylolite Teeth Patterns Depending on Normal Stress and Finite Compaction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2007, 257, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelier, J. Tectonic Analysis of Fault Slip Data Sets. J. Geophys. Res. 1984, 89, 5835–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O. Do Fault Slip Data Inversions Actually Yield “Paleostresses” That Can Be Compared with Contemporary Stresses? A Critical Discussion. Comptes Rendus Geosci. 2012, 344, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, C. Paleostress Inversion Techniques: Methods and Applications for Tectonics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 978-0-12-811947-1. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard, M. Calcite Twins, Their Geometry, Appearance and Significance as Stress-Strain Markers and Indicators of Tectonic Regime: A Review. J. Struct. Geol. 1993, 15, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O. Paleostress Magnitudes Associated with Development of Mountain Belts: Insights from Tectonic Analyses of Calcite Twins in the Taiwan Foothills. Tectonics 2001, 20, 834–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O.; Parlangeau, C.; Beaudoin, N.E.; Amrouch, K. Calcite Twin Formation, Measurement and Use as Stress–Strain Indicators: A Review of Progress over the Last Decade. Geosciences 2021, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrouch, K.; Lacombe, O.; Bellahsen, N.; Daniel, J.-M.; Callot, J.-P. Stress and Strain Patterns, Kinematics and Deformation Mechanisms in a Basement-Cored Anticline: Sheep Mountain Anticline, Wyoming. Tectonics 2010, 29, TC1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrouch, K.; Beaudoin, N.; Lacombe, O.; Bellahsen, N.; Daniel, J.-M. Paleostress Magnitudes in Folded Sedimentary Rocks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L17301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, N.; Leprêtre, R.; Bellahsen, N.; Lacombe, O.; Amrouch, K.; Callot, J.-P.; Emmanuel, L.; Daniel, J.-M. Structural and Microstructural Evolution of the Rattlesnake Mountain Anticline (Wyoming, USA): New Insights into the Sevier and Laramide Orogenic Stress Build-up in the Bighorn Basin. Tectonophysics 2012, 576–577, 20–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, N.; Koehn, D.; Lacombe, O.; Lecouty, A.; Billi, A.; Aharonov, E.; Parlangeau, C. Fingerprinting Stress: Stylolite and Calcite Twinning Paleopiezometry Revealing the Complexity of Progressive Stress Patterns during Folding—The Case of the Monte Nero Anticline in the Apennines, Italy. Tectonics 2016, 35, 1687–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O.; Angelier, J.; Laurent, P.; Bergerat, F.; Tourneret, C. Joint Analyses of Calcite Twins and Fault Slips as a Key for Deciphering Polyphase Tectonics: Burgundy as a Case Study. Tectonophysics 1990, 182, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O.; Amrouch, K.; Mouthereau, F.; Dissez, L. Calcite Twinning Constraints on Late Neogene Stress Patterns and Deformation Mechanisms in the Active Zagros Collision Belt. Geology 2007, 35, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O.; Malandain, J.; Vilasi, N.; Amrouch, K.; Roure, F. From Paleostresses to Paleoburial in Fold–Thrust Belts: Preliminary Results from Calcite Twin Analysis in the Outer Albanides. Tectonophysics 2009, 475, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourneret, C.; Laurent, P. A New Computer Method for Rapid and Precise Determination of Calcite Crystallographic Orientation from U-Stage Measurements. Comput. Geosci. 1991, 17, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeboudj, A.; Bah, B.; Lacombe, O.; Beaudoin, N.E.; Gout, C.; Godeau, N.; Girard, J.-P.; Deschamps, P. Depicting Past Stress History at Passive Margins: A Combination of Calcite Twinning and Stylolite Roughness Paleopiezometry in Supra-Salt Sendji Deep Carbonates, Lower Congo Basin, West Africa. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 152, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O.; Laurent, P. Determination of Deviatoric Stress Tensors Based on Inversion of Calcite Twin Data from Experimentally Deformed Monophase Samples: Preliminary Results. Tectonophysics 1996, 255, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, P.; Kern, H.; Lacombe, O. Determination of Deviatoric Stress Tensors Based on Inversion of Calcite Twin Data from Experimentally Deformed Monophase Samples. Part II. Axial and Triaxial Stress Experiments. Tectonophysics 2000, 327, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlangeau, C.; Lacombe, O.; Schueller, S.; Daniel, J.-M. Inversion of Calcite Twin Data for Paleostress Orientations and Magnitudes: A New Technique Tested and Calibrated on Numerically-Generated and Natural Data. Tectonophysics 2018, 722, 462–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bah, B.; Lacombe, O.; Beaudoin, N.E.; Zeboudj, A.; Gout, C.; Girard, J.-P.; Teboul, P.-A. Paleostress Evolution of the West Africa Passive Margin: New Insights from Calcite Twinning Paleopiezometry in the Deeply Buried Syn-Rift TOCA Formation (Lower Congo Basin). Tectonophysics 2023, 863, 229997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.M.W.; Drost, K.; Horstwood, M.S.A.; Condon, D.J.; Chew, D.; Drake, H.; Milodowski, A.E.; McLean, N.M.; Smye, A.J.; Walker, R.J.; et al. Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) U–Pb Carbonate Geochronology: Strategies, Progress, and Limitations. Geochronology 2020, 2, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeesch, P. IsoplotR: A Free and Open Toolbox for Geochronology. Geosci. Front. 2018, 9, 1479–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagel, M.; Bonifacie, M.; Schneider, D.A.; Gautheron, C.; Brigaud, B.; Calmels, D.; Cros, A.; Saint-Bezar, B.; Landrein, P.; Sutcliffe, C.; et al. Improving Paleohydrological and Diagenetic Reconstructions in Calcite Veins and Breccia of a Sedimentary Basin by Combining Δ47 Temperature, δ18Owater and U-Pb Age. Chem. Geol. 2018, 481, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drost, K.; Chew, D.; Petrus, J.A.; Scholze, F.; Woodhead, J.D.; Schneider, J.W.; Harper, D.A.T. An Image Mapping Approach to U-Pb LA-ICP-MS Carbonate Dating and Applications to Direct Dating of Carbonate Sedimentation. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2018, 19, 4631–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoareau, G.; Claverie, F.; Pecheyran, C.; Barbotin, G.; Perk, M.; Beaudoin, N.E.; Lacroix, B.; Rasbury, E.T. The Virtual-Spot Approach: A Simple Method for Image U–Pb Carbonate Geochronology by High-Repetition-Rate LA-ICP-MS. Geochronology 2025, 7, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoareau, G.; Claverie, F.; Pecheyran, C.; Paroissin, C.; Grignard, P.-A.; Motte, G.; Chailan, O.; Girard, J.-P. Direct U–Pb Dating of Carbonates from Micron-Scale Femtosecond Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry Images Using Robust Regression. Geochronology 2021, 3, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.A.; Polyak, V.J.; Asmerom, Y.; Provencio, P.P. Constraints on a Late Cretaceous Uplift, Denudation, and Incision of the Grand Canyon Region, Southwestern Colorado Plateau, USA, from U-Pb Dating of Lacustrine Limestone. Tectonics 2016, 35, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstwood, M.S.A.; Košler, J.; Gehrels, G.; Jackson, S.E.; McLean, N.M.; Paton, C.; Pearson, N.J.; Sircombe, K.; Sylvester, P.; Vermeesch, P.; et al. Community-Derived Standards for LA-ICP-MS U-(Th-)Pb Geochronology—Uncertainty Propagation, Age Interpretation and Data Reporting. Geostand. Geoanalytical Res. 2016, 40, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godeau, N.; Deschamps, P.; Guihou, A.; Leonide, P.; Tendil, A.; Gerdes, A.; Hamelin, B.; Girard, J.-P. U-Pb Dating of Calcite Cement and Diagenetic History in Microporous Carbonate Reservoirs: Case of the Urgonian Limestone, France. Geology 2018, 46, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroux, E.; Béthoux, N.; Bellier, O. Analyses of the Stress Field in Southeastern France from Earthquake Focal Mechanisms. Geophys. J. Int. 2001, 145, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michard, A.; Dumont, T.; Andreani, L.; Loget, N. Cretaceous Folding in the Dévoluy Mountains (Subalpine Chains, France): Gravity-Driven Detachment at the European Paleomargin versus Compressional Event. Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 2010, 181, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottram, C.; Coutand, I.; Grujic, D.; Kellett, D. Directly Dating Deformation with Calcite U-Pb; the Good, the Bad and the Ugly! Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2019, 21, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, J. Les Formations Calcaires à Rudistes du Crétacé Supérieur Provençal et Rhodanien. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Marseille, Marseille, France, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, J. La Bande Triasique de l’Huveaune. In Villeneuve et al. Mémoire Explicatif, Carte géol. France (1/50 000), Feuille Aubagne-Marseille, 3ième Edition (1044); BRGM: Orléans, France, 2018; pp. 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, J.; Vianey-Liaud, M.; Martin-Closas, C.; Tabuce, R.; Léonide, P.; Margerel, J.-P.; Noël, J. Stratigraphy of the Haut Var Paleogene Continental Series (Northeastern Provence, France): New Insight on the Age of the ‘Sables Bleutés du Haut Var’ Formation. Geobios 2017, 50, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenat, C.; Barrier, P.; Hibsch, C. Enregistrement des événements pyrénéo-provençaux dans les chaînes subalpines méridionales (Baronnies, France). Sédimentation continentale et tectonique éocènes. Géologie Fr. 2005, 1, 23–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrill, D.A.; Cawood, A.J.; Smart, K.J.; Lehrmann, D.J.; Evans, M.A.; Stockli, L.D.; Stockli, D.F. Fault Zone Deformation and Fracture Intensity in Chalk-Dominated Carbonates. J. Struct. Geol. 2025, 199, 105469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykut, T.; Yıldırım, C.; Uysal, I.T.; Ring, U.; Zhao, J. Coeval Upper Crustal Extension and Surface Uplift in the Central Taurides (Türkiye) above the Cyprus Subduction Zone. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, J.; Anderson, M.; Mottram, C.; Price, G.D.; Parrish, R.; Sanderson, D. Using U–Pb Carbonate Dating to Constrain the Timing of Extension and Fault Reactivation within the Bristol Channel Basin, SW England. J. Geol. Soc. 2024, 181, jgs2024–jgs2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pană, D.I.; van der Pluijm, B.A. Orogenic Pulses in the Alberta Rocky Mountains: Radiometric Dating of Major Faults and Comparison with the Regional Tectono-Stratigraphic Record. GSA Bull. 2015, 127, 480–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pluijm, B.A.; Vrolijk, P.J.; Pevear, D.R.; Hall, C.M.; Solum, J. Fault Dating in the Canadian Rocky Mountains: Evidence for Late Cretaceous and Early Eocene Orogenic Pulses. Geology 2006, 34, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homberg, C.; Hu, J.C.; Angelier, J.; Bergerat, F.; Lacombe, O. Characterization of Stress Perturbations near Major Fault Zones: Insights from 2-D Distinct-Element Numerical Modelling and Field Studies (Jura Mountains). J. Struct. Geol. 1997, 19, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, C.; Hellstrom, J.; Paul, B.; Woodhead, J.; Hergt, J. Iolite: Freeware for the visualisation and processing of mass spectrometric data. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2011, 26, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, J.D.; Hergt, J.M. Strontium, neodymium and lead isotope analyses of NIST glass certified reference materials: SRM 610, 612, 614. Geostand. Newslett. 2001, 25, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, D.M.; Petrus, J.A.; Kamber, B.S. U–Pb LA–ICPMS dating using accessory mineral standards with variable common Pb. Chem. Geol. 2014, 363, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.; Griffin, W.L.; Pearson, N.J.; Powell, W.; Wieland, P.; O’Reilly, S.Y. Trace element partitioning in mixed-habit diamonds. Chem. Geol. 2013, 355, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo, S.M.; Ewing, T.A.; Müntener, O. Paleocene metamorphism along the Pennine–Austroalpine suture constrained by U–Pb dating of titanite and rutile (Malenco, Alps). Swiss J Geosci 2019, 112, 517–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaise, T.; Augier, R.; Bosch, D.; Bruguier, O.; Cogne, N.; Deschamps, P.; Guihou, A.; Haurine, F.; Hoareau, G.; Nouet, J. Characterisation and interlaboratory comparison of a new calcite reference material for U-Pb geochronology—The “AUG-B6” calcite-cemented hydraulic breccia. In Proceedings of the 2023 Goldschmidt Conference, Lyon, France, 9–14 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | Site | Formation | Structure/ Vein Set | Age (Ma) | Uncertainties (Ma) | MSWD | U (µg/g) | Pb (µg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRT_22_Z093-cem2 | 1N | Barremian | Diag. cement | 67.3 | ±0.9 Ι 2.5 | 1.67 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z093-cem1 | 1N | Barremian | Diag. cement | 71.7 | ±3.6 Ι 4.3 | 1.8 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z096-1 | 3N | Valanginian | JN-D | 92.8 | ±1.7 Ι 3.5 | 1.75 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z096-2 | 3N | Valanginian | JN-D | 93.1 | ±1.2 Ι 3.3 | 1.36 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z103-1 | 3N | Valanginian | JN-D | 108.7 | ±0.3 Ι 1.6 | 5.7 | 5–0.3 | <0.2 |

| NRT_22_Z105 | 4N | Valanginian | JN-D | 92.9 | ±1.3 Ι 3.3 | 3 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z107 | 5N | Tithonian | JN-A | 43.6 | ±1 Ι 1.8 | 1.93 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z118b | 5N | Tithonian | JN-C | 110.1 | ±0.5 | 0.83 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z121 | 6N | Turonian– Santonian | JN-A | 78.4 | ±1 Ι 1.9 | 0.89 | 2–0.3 | <0.5 |

| NRT_22_Z126 | 6N | Turonian– Santonian | Minor fault | 75.5 | ±1.1 Ι 2.9 | 1.8 | 1.5–0.1 | 0.7–0.1 |

| NRT_22_Z128 | 6N | Turonian– Santonian | Minor fault | 36.8 | ±0.3 Ι 1 | 3.3 | 0.7–0.1 | <0.1 |

| NRT_22_Z132-C | 7N | Turonian– Santonian | Fault rock | 72.7 | ±1.3 | 1 | 3–0.02 | 0.2–0.03 |

| NRT_22_Z133a | 7N | Tithonian | Fault rock | 70.4 | ±1.4 Ι 2.4 | 2.9 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z133b | 7N | Tithonian | Fault rock | 33.4 | ±1.3 Ι 2.5 | 3 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z136-1 | 8N | Tithonian | JN-C | 75.9 | ±1 Ι 2.7 | 1.79 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z137-1 | 8N | Tithonian | JN-B | 78.1 | ±0.8 Ι 2.3 | 9.6 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z137-2 | 8N | Tithonian | JN-C | 74.5 | ±1.7 Ι 3 | 1.31 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z137-3 | 8N | Tithonian | JN-B | 75.9 | ±0.4 Ι 0.7 | 2.6 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z142 | 9N | Barremian | JN-A | 79.6 | ±0.5 Ι 1.1 | 4.4 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z154 | 9N | Barremian | JN-B | 81 | ±1.3 Ι 2.3 | 3 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z155 | 9N | Barremian | Minor fault | 79.7 | ±0.3 Ι 0.6 | 3.7 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z159 | 9N | Barremian | Diag. cement | 43.4 | ±24 Ι 24 | 1.13 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z161 | 9N | Barremian | Diag. cement | 28.7 | ±0.4 Ι 1 | 3.38 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z169-2 | 10N | Valanginian | JN-B | 78 | ±1 Ι 2.8 | 0.81 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z170 | 11N | Valanginian | JN-D | 108.4 | ±1 Ι 1.1 | 1.5 | 3–0.6 | <0.05 |

| NRT_22_Z181 | 11N | Valanginian | Minor vein set | 74.5 | ±0.6 Ι 1 | 3.2 | 3–0.1 | 0.2–0.005 |

| NRT_22_Z189_1a | 14N | Barremian | JN-B | 77.8 | ±1.6 Ι 2.8 | 1.12 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z189_1b | 14N | Barremian | JN-B | 70.2 | ±1.8 Ι 2.6 | 2.38 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z189_2a | 14N | Barremian | JN-C | 73.5 | ±0.7 Ι 1.8 | 1.75 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z189_2b | 14N | Barremian | JN-C | 20.2 | ±2.3 Ι 5.2 | 4.7 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z190-a | 14N | Barremian | Fault rock | 71.7 | ±0.73 | 0.25 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z190-b | 14N | Barremian | Diag. cement | 18.6 | ±9.6 | 1.6 | - | - |

| NRT_22_Z203 | 17N | Kimmeridgian | Fault rock | 55.2 | ±9.1 Ι 9.3 | 0.79 | 5–0.3 | <0.2 |

| RNS_21_Z002 | 3R | Maastrichtian | JR-B | 33.1 | ±1 Ι 1.6 | 2.4 | 0.8–0.01 | 0.07–0.01 |

| RNS_21_ZB2-J1 | 3R | Maastrichtian | jog | 45.4 | ±1.7 Ι 2 | 0.85 | - | - |

| RNS_21_ZB3-1 | 3R | Maastrichtian | JR-A | 35.9 | ±0.5 Ι 1.7 | 1.14 | - | - |

| RNS_21_ZB4-1 | 3R | Maastrichtian | JR-A | 32.7 | ±0.6 Ι 1.3 | 1.09 | - | - |

| BIM_22_Z206 | 19B-Contact | Bathonian– Bajocian | Fault rock | 57.2 | ±1.5 Ι 3.9 | 1.8 | 0.3–0.01 | <0.05 |

| BIM_22_Z207 | 19B-Contact | Bathonian– Bajocian | Fault rock | 47.1 | ±5.5 Ι 5.7 | 0.75 | - | - |

| BIM_22_Z211 | 19B-Cave | Toarcian | Minor fault | 57.4 | ±12.6 Ι 12.7 | 0.74 | - | - |

| BIM_22_Z212a | 19B-Cave | Toarcian | Minor fault | 71.1 | ±1.1 Ι 2.7 | 5.4 | - | - |

| BIM_22_Z212b | 19B-Cave | Toarcian | Minor fault | 33 | ±6 | 0.45 | - | - |

| BIM_22_Z215 | 20B | Kimmeridgian | Fault rock | 58.6 | ±4.1 Ι 4.5 | 1.14 | - | - |

| BIM_22_Z216 | 20B | Kimmeridgian | Fault rock | 25.9 | ±0.9 Ι 1.3 | 3.3 | 2–0.01 | <0.1 |

| BIM_22_C8-1 | 16B | Kimmeridgian | JB-A | 18.5 | ±9.1 Ι 9.1 | 0.59 | - | - |

| BIM_22_C8-3 | 16B | Kimmeridgian | JB-A | 29.2 | ±3 Ι 3.1 | 0.86 | - | - |

| BIM_22_C8-J1 | 16B | Kimmeridgian | jog | 96.4 | ±3.3 Ι 4.6 | 1 | - | - |

| BIM_22_C8-J2 | 16B | Kimmeridgian | jog | 57.2 | ±2.4 Ι 3 | 1.11 | - | - |

| BIM_22_C8-J3 | 16B | Kimmeridgian | jog | 109 | ±1.1 Ι 3.8 | 1.22 | - | - |

| BIM_21_Z071-2 | 14B | Kimmeridgian | JB-A | 27.4 | ±1 Ι 1.3 | 0.87 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeboudj, A.; Lacombe, O.; Beaudoin, N.E.; Callot, J.-P.; Lamarche, J.; Guihou, A.; Hoareau, G.; Barbotin, G.; Pecheyran, C.; Deschamps, P. Timing of Deformation in the Provence Fold-and-Thrust Belt (SE France) as Constrained by U-Pb Calcite Geochronology. Geosciences 2025, 15, 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120463

Zeboudj A, Lacombe O, Beaudoin NE, Callot J-P, Lamarche J, Guihou A, Hoareau G, Barbotin G, Pecheyran C, Deschamps P. Timing of Deformation in the Provence Fold-and-Thrust Belt (SE France) as Constrained by U-Pb Calcite Geochronology. Geosciences. 2025; 15(12):463. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120463

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeboudj, Anies, Olivier Lacombe, Nicolas E. Beaudoin, Jean-Paul Callot, Juliette Lamarche, Abel Guihou, Guilhem Hoareau, Gaëlle Barbotin, Christophe Pecheyran, and Pierre Deschamps. 2025. "Timing of Deformation in the Provence Fold-and-Thrust Belt (SE France) as Constrained by U-Pb Calcite Geochronology" Geosciences 15, no. 12: 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120463

APA StyleZeboudj, A., Lacombe, O., Beaudoin, N. E., Callot, J.-P., Lamarche, J., Guihou, A., Hoareau, G., Barbotin, G., Pecheyran, C., & Deschamps, P. (2025). Timing of Deformation in the Provence Fold-and-Thrust Belt (SE France) as Constrained by U-Pb Calcite Geochronology. Geosciences, 15(12), 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120463