Elemental Geochemical Analysis for the Gold–Antimony Segregation in the Gutaishan Deposit: Insights from Stibnite and Pyrite

Abstract

1. Introduction

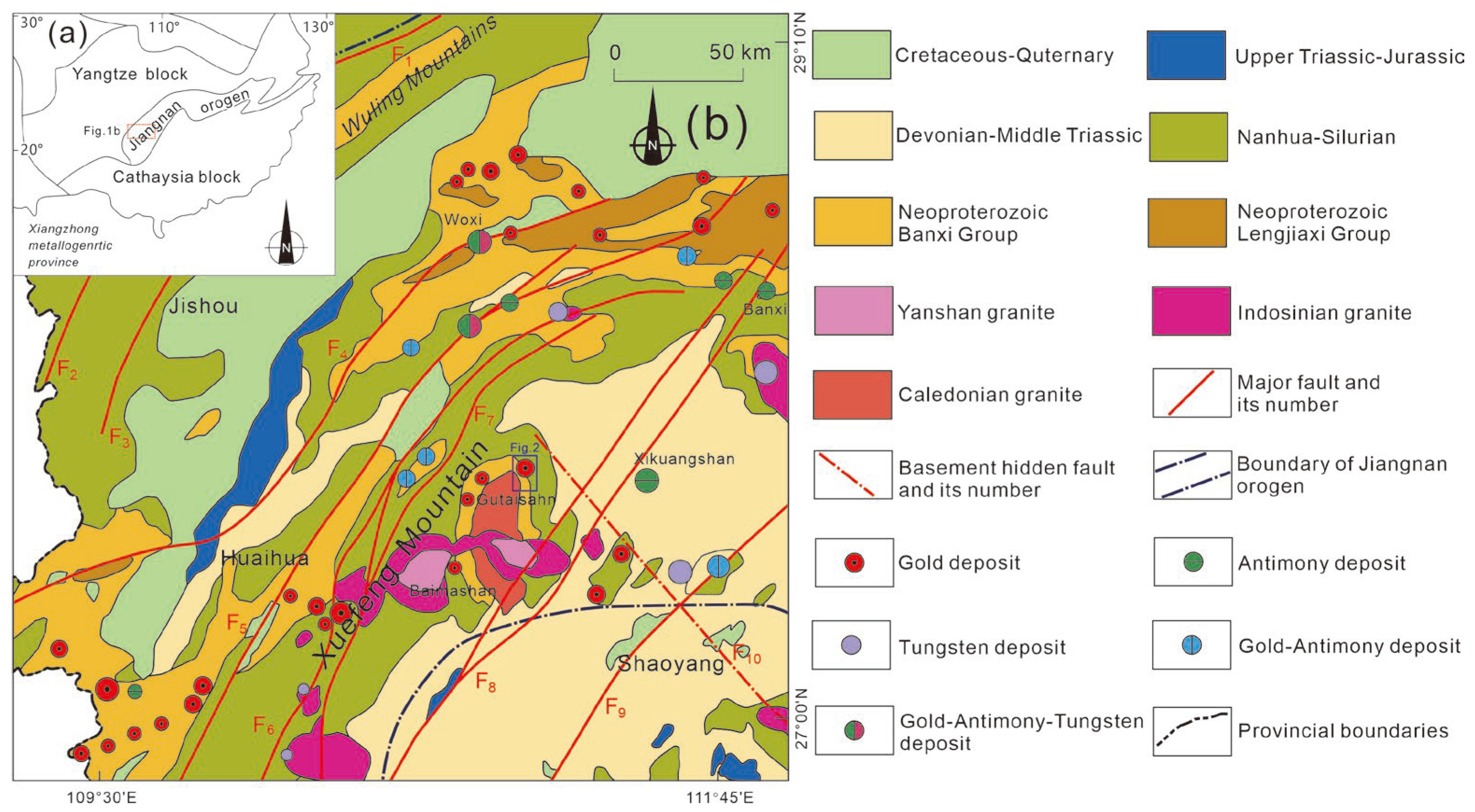

2. Geological Background

2.1. Regional Geology

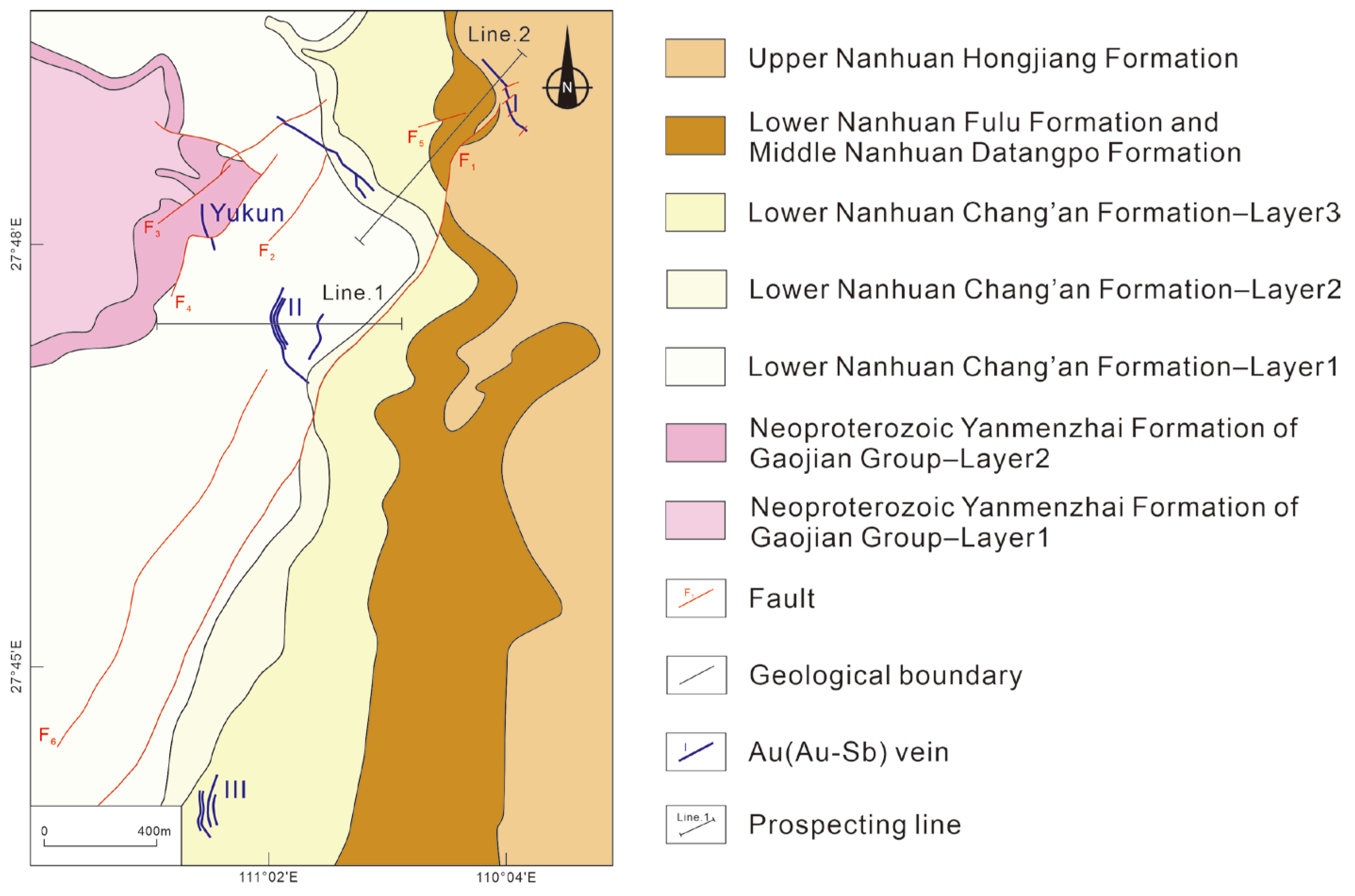

2.2. Ore Deposit Geology

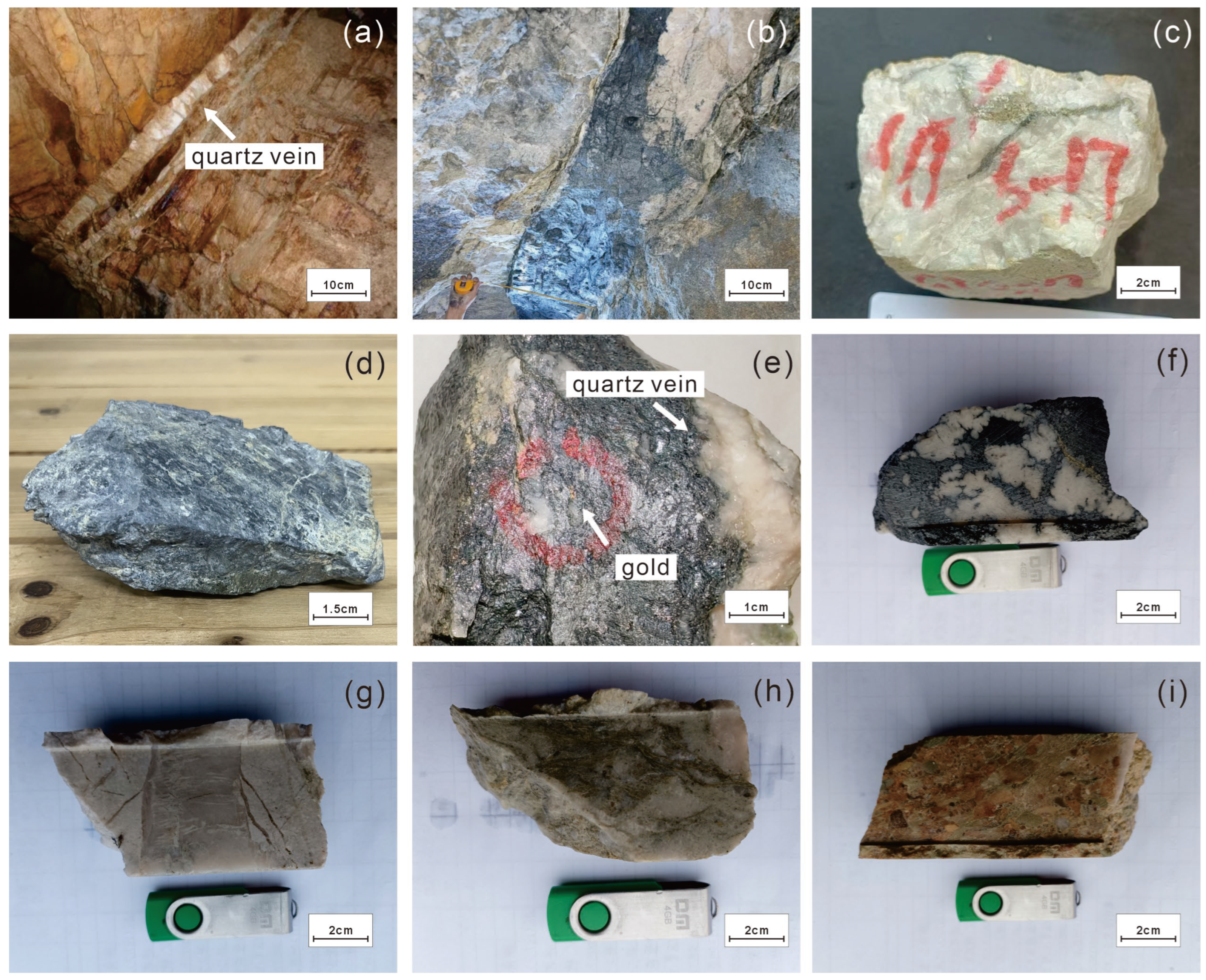

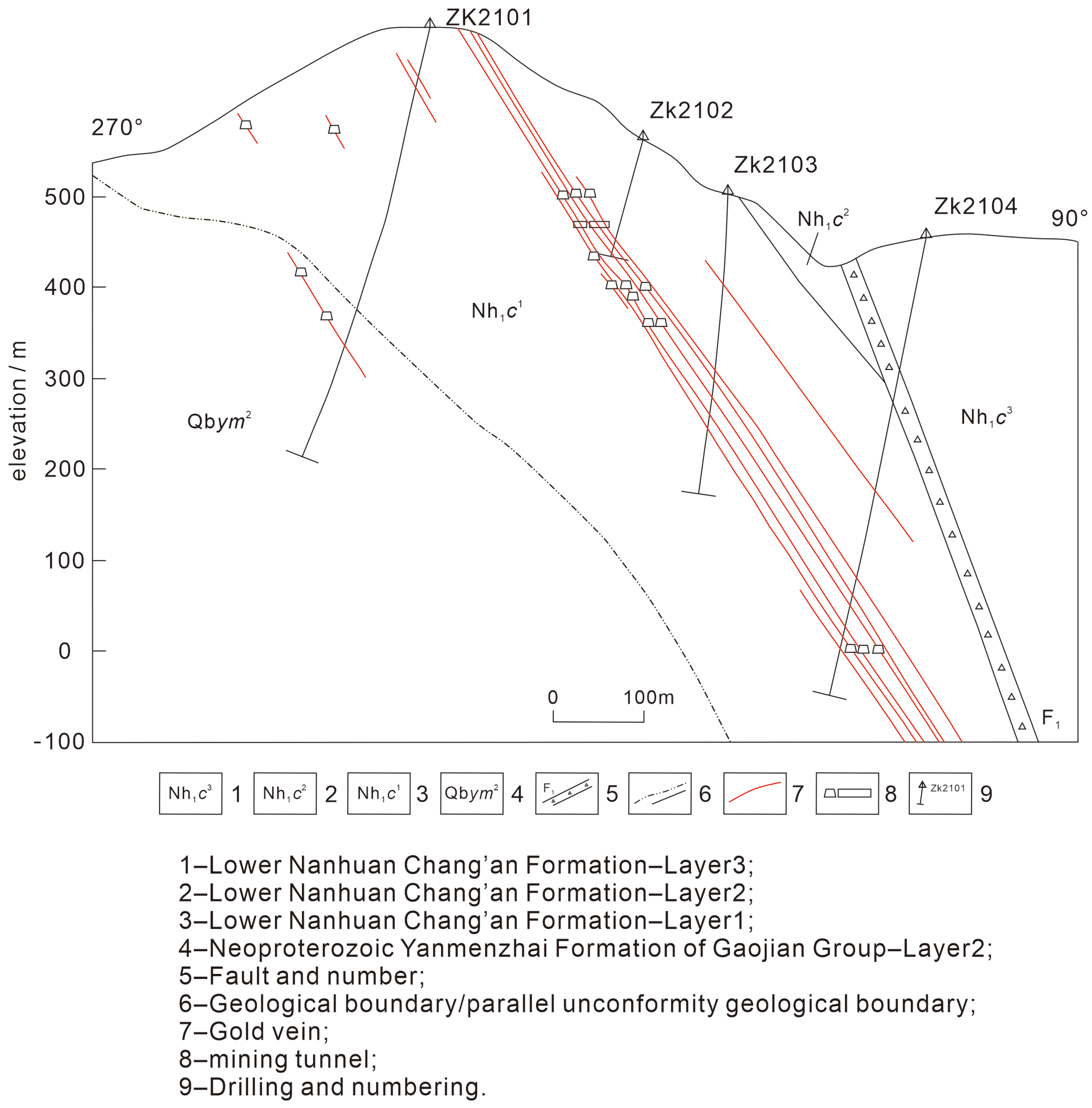

2.3. Ore Body Features

3. Sampling and Methods

3.1. Sampling

3.2. EPMA

3.3. LA–ICP–MS

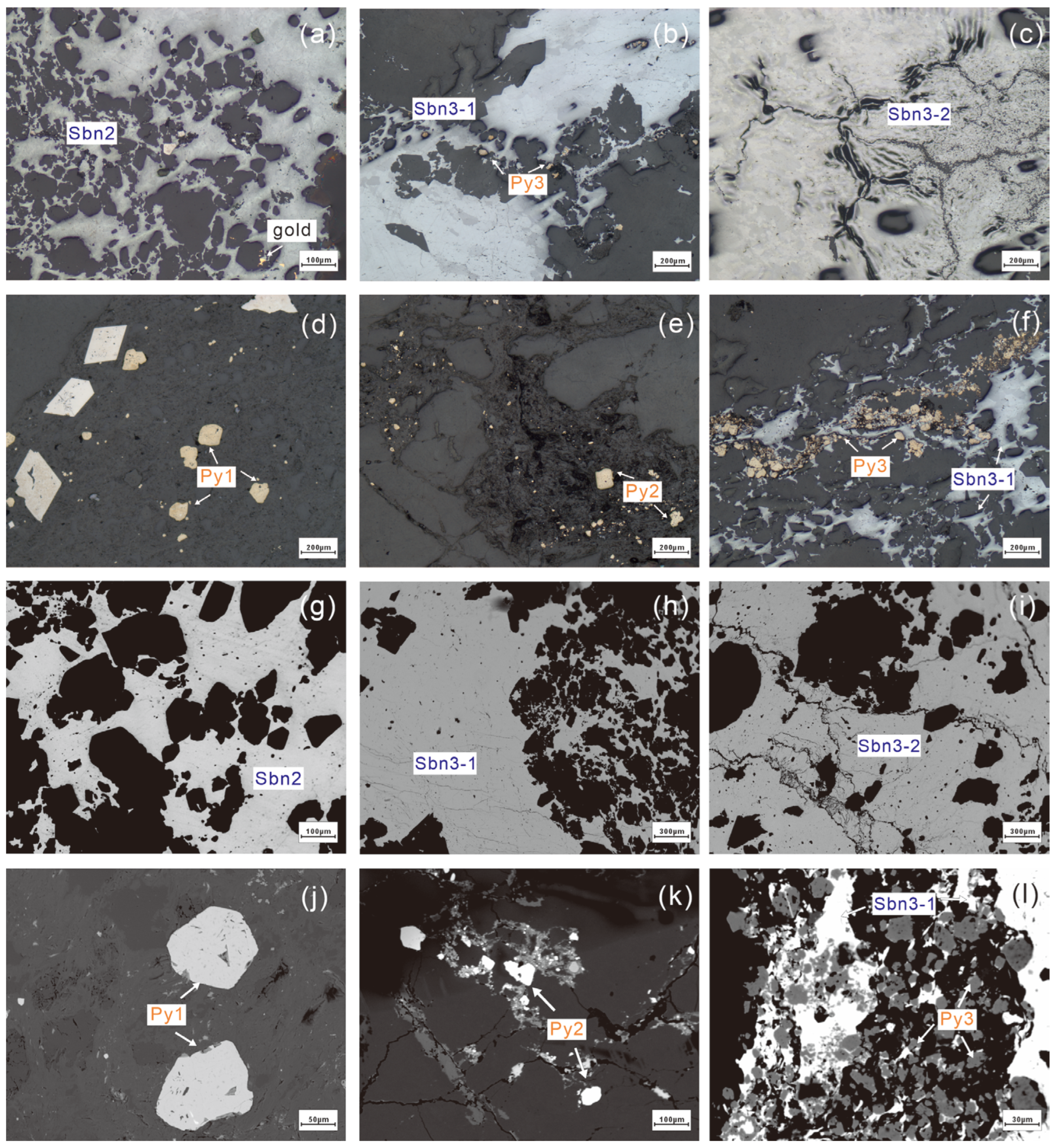

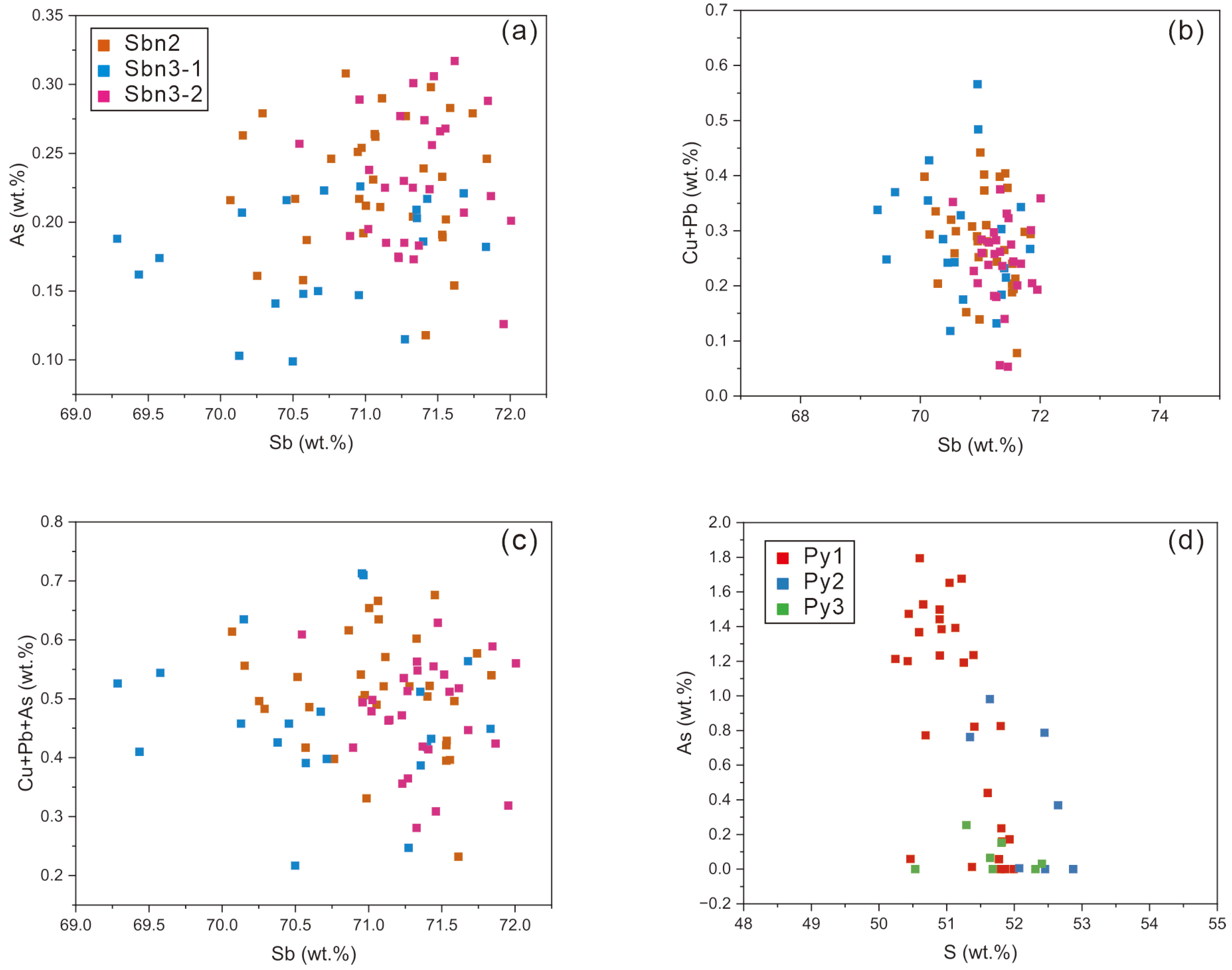

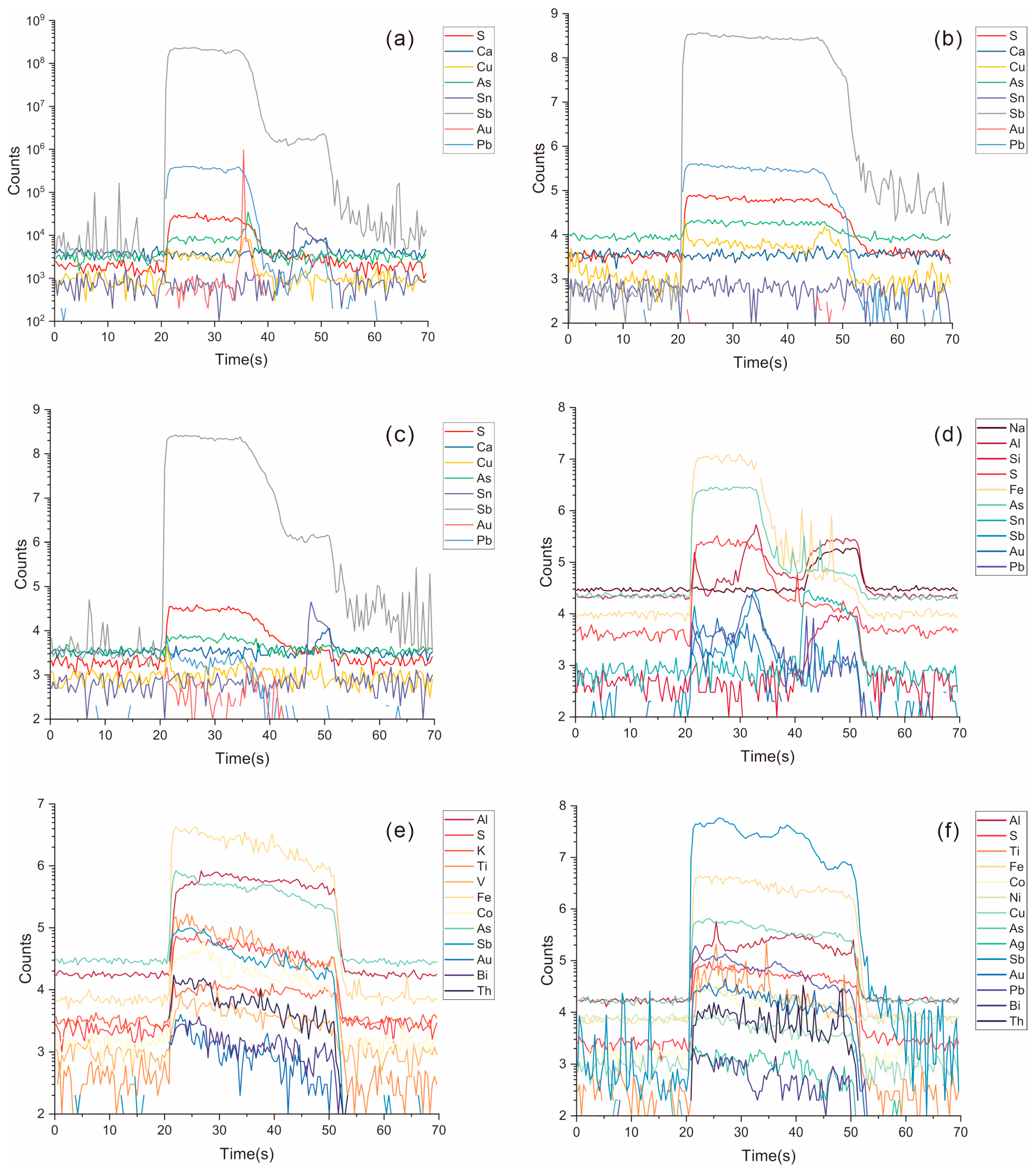

4. Major and Trace Elements of Stibnite and Pyrite

4.1. Major Elements

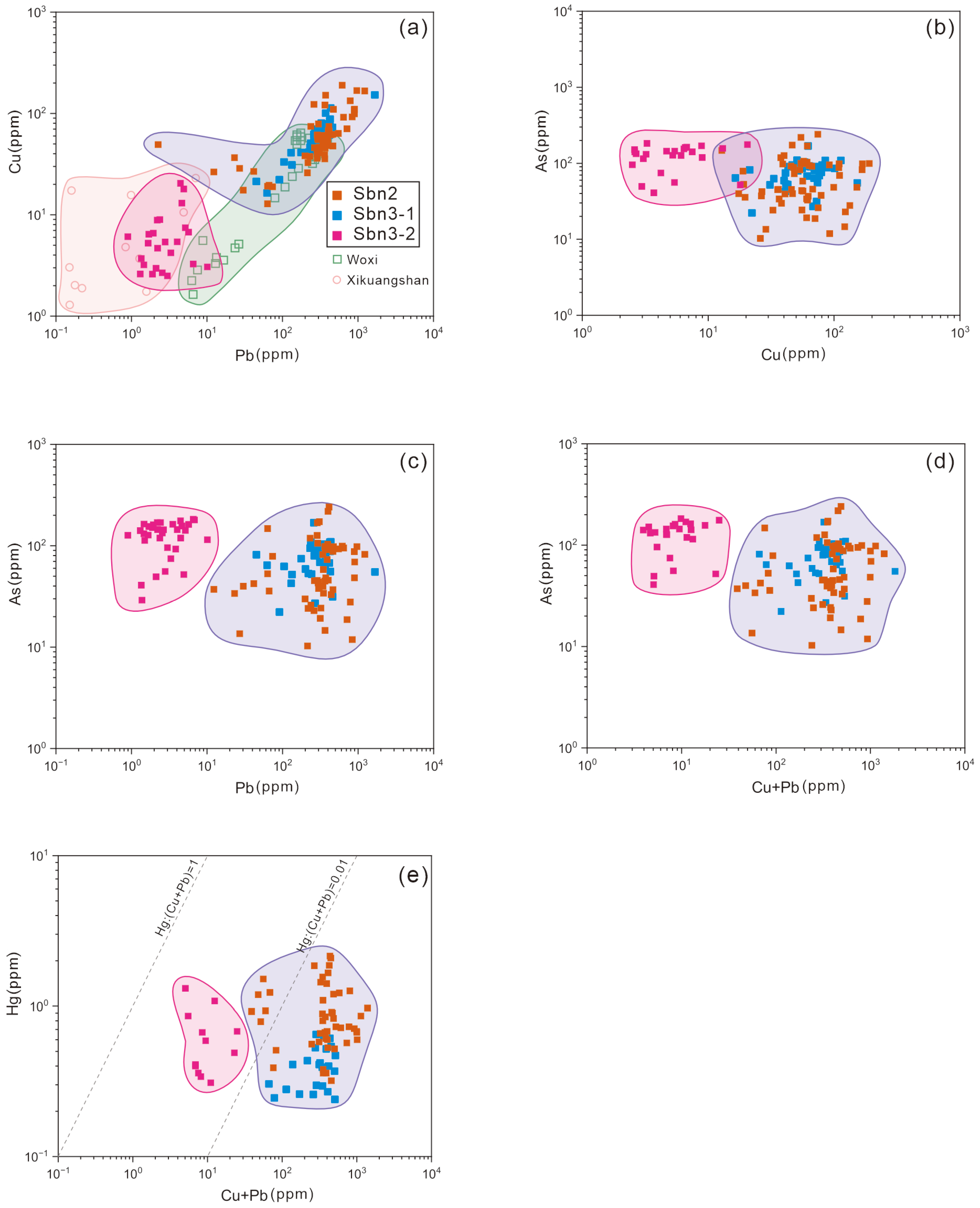

4.2. Trace Elements

5. Discussion

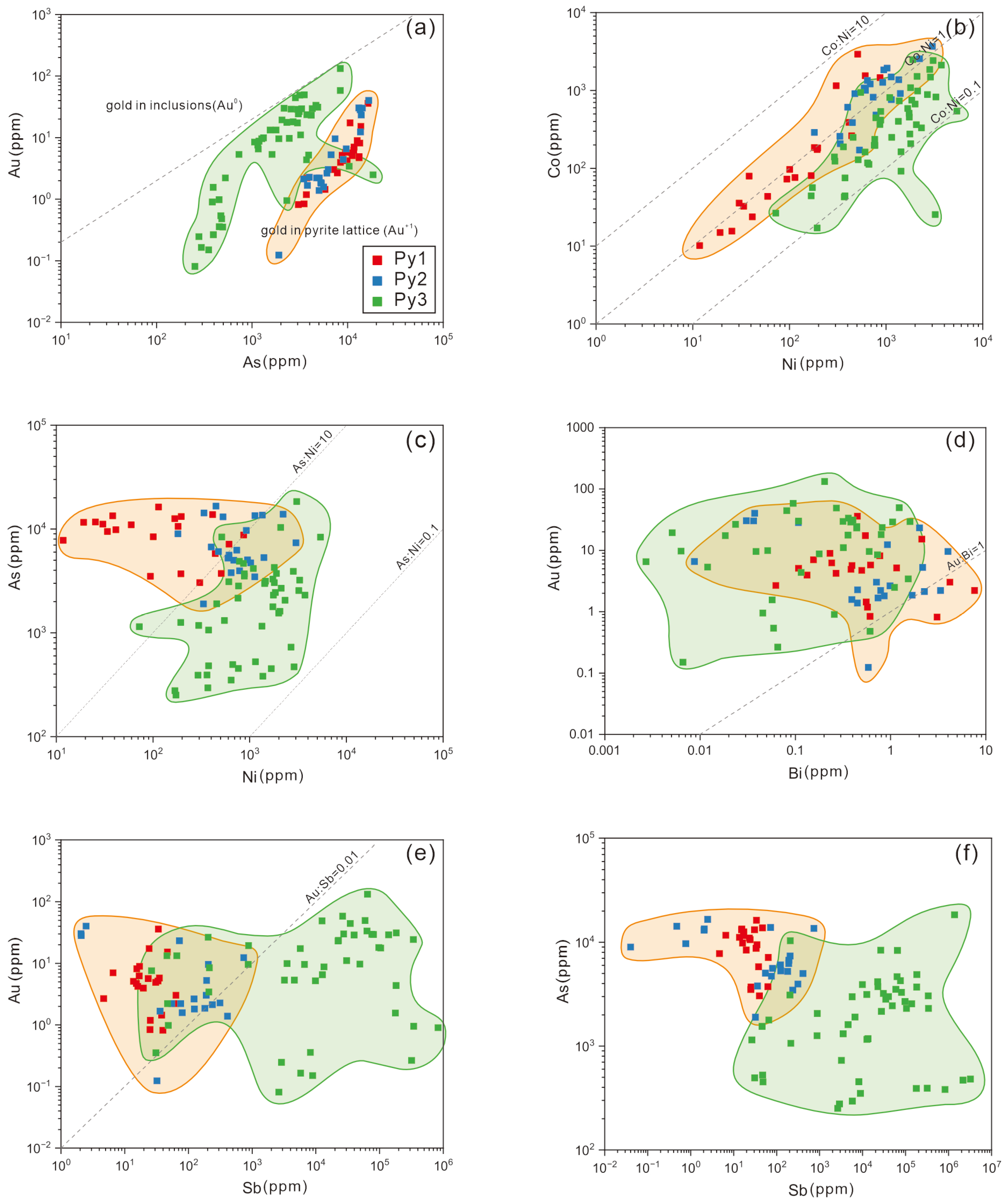

5.1. Occurrence of Trace Elements

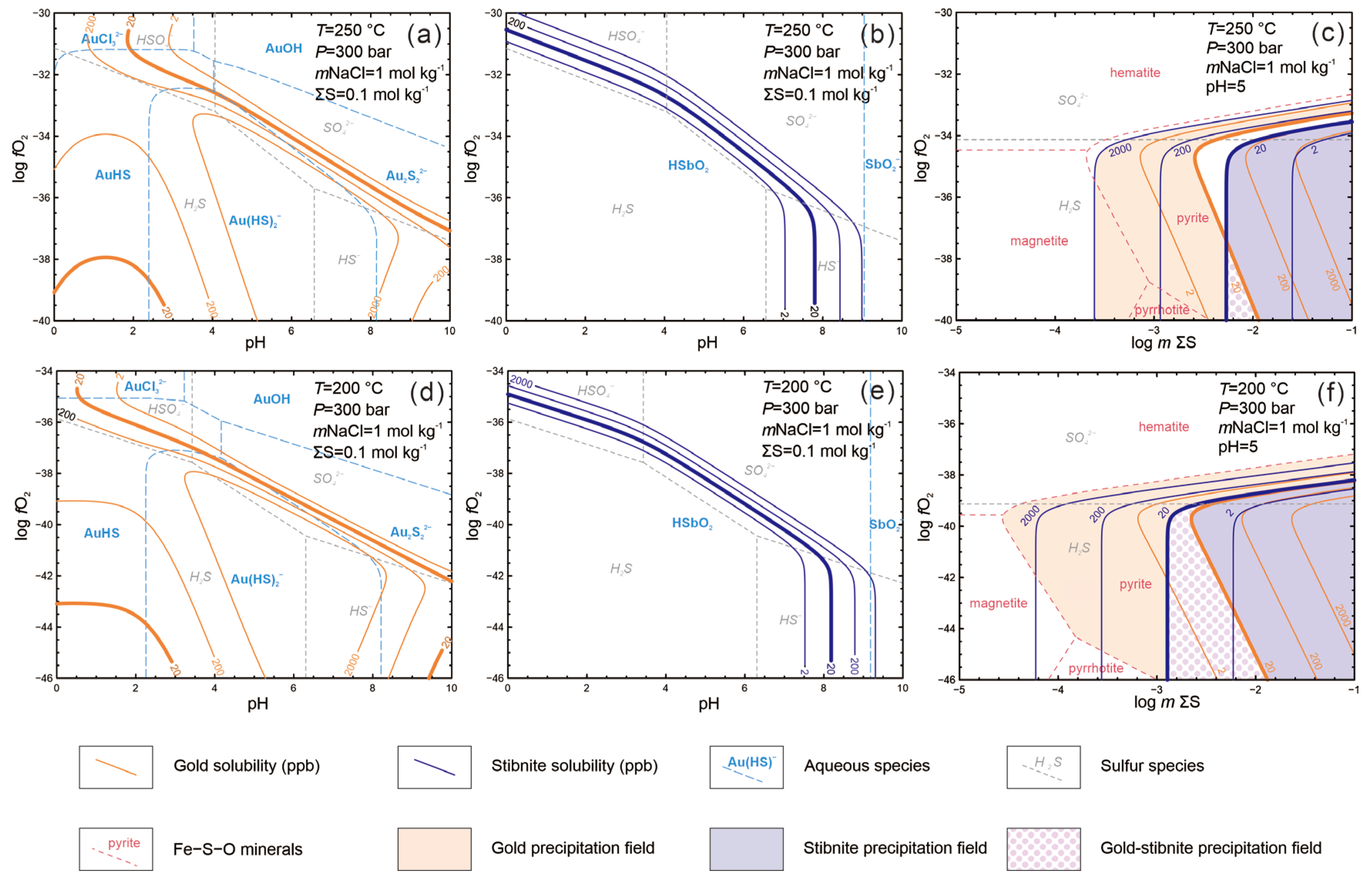

5.2. Implications for Ore-Forming Fluids

5.3. Gold–Antimony Segregation Models

6. Conclusions

- The ore-forming fluids of the Gutaishan deposit are mainly magmatic–hydrothermal in origin, with minor contributions from the metamorphic basement, and were active during the Indosinian and Yanshanian periods.

- The stibnite in the Gutaishan deposit is predominantly of the Woxi type (magmatic–hydrothermal fluids), with minor input from the Xikuangshan type (metamorphic basement fluids).

- Temperature decrease is the dominant factor controlling gold–antimony segregation: gold precipitated first at a high temperature, while the co-precipitation of gold and stibnite deposited at a lower temperature.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- An, F.; Zhu, Y. Native antimony in the Baogutu gold deposit (west Junggar, NW China): Its occurrence and origin. Ore Geol. Rev. 2010, 37, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellot, J.-P.; Lerouge, C.; Bailly, L.; Bouchot, V. The Biards Sb-Au–bearing shear zone (Massif Central, France): An indicator of crustal-scale transcurrent tectonics guiding late Variscan collapse. Econ. Geol. 2003, 98, 1427–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.J.; Chryssoulis, S.L. Concentrations of invisible gold in the common sulfides. Can. Mineral. 1990, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Silyanov, S.A.; Sazonov, A.M.; Naumov, E.A.; Lobastov, B.M.; Zvyagina, Y.A.; Artemyev, D.A.; Nekrasova, N.A.; Pirajno, F. Mineral Paragenesis, formation stages and trace elements in sulfides of the Olympiada gold deposit (Yenisei Ridge, Russia). Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 143, 104750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, D.-P.; Shen, L.-W.; Algeo, T.J.; Elatikpo, S.M. A general ore formation model for metasediment-hosted Sb-(Au-W) mineralization of the Woxi and Banxi deposits in South China. Chem. Geol. 2022, 607, 121020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wu, Y.; Yu, P.; Chen, X.; Hu, Z.; Long, L. Triassic multistage antimony-gold mineralization in the Precambrian sedimentary rocks of South China: Insights from structural analysis, paragenesis, 40Ar/39Ar age, in-situ S-Pb isotope and trace elements of the Longwangjiang-Jiangdongwan orefield, Xuefengshan Mountain. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 148, 105030. [Google Scholar]

- Krinov, L. A Review on the mineralogy of stibnite in hydrothermal gold deposits. Acad. J. Earth Sci. 2024, 2, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Sun, X.; Yi, J.; Zhang, X.; Mo, R.; Zhou, F.; Wei, H.; Zeng, Q. Geology, geochemistry, and genesis of orogenic gold–antimony mineralization in the Himalayan Orogen, South Tibet, China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2014, 58, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, R.; Xiao, J.; Zhuo, Y.; Yan, J.; Oyebamiji, A. Genesis of gold and antimony deposits in the Youjiang metallogenic province, SW China: Evidence from in situ oxygen isotopic and trace element compositions of quartz. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 116, 103257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, Z.-L.; Yang, R.-D.; Du, L.-J.; Liao, M.-Y. Gold and antimony metallogenic relations and ore-forming process of Qinglong Sb (Au) deposit in Youjiang basin, SW China: Sulfide trace elements and sulfur isotopes. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiva, A.; Andráš, P.; Ramos, J. Antimony quartz and antimony–gold quartz veins from northern Portugal. Ore Geol. Rev. 2008, 34, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryachev, N.; Yurgenson, G.; Nikanyuk, T. Ore mineralization of the Aliya ore field (Transbaikalian sector of the Mongol–Okhotsk Orogenic Belt): Structural relationships, mineralogy, geochemistry, and zoning. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2025, 66, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, L.-Q.; Groves, D.I.; Sun, S.-C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.-Y.; Li, R.-H.; Wu, S.-G.; Gao, L.; Guo, J.-L. An overview of timing and structural geometry of gold, gold-antimony and antimony mineralization in the Jiangnan Orogen, southern China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 115, 103173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xie, G.-Q.; Mao, J.-W.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Fu, B.; Lu, S. Muscovite 40Ar/39Ar and in situ sulfur isotope analyses of the slate-hosted Gutaishan Au–Sb deposit, South China: Implications for possible Late Triassic magmatic-hydrothermal mineralization. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 101, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Shao, Y.; Tan, H.; Li, H.; Lai, C. Ore-forming mechanism and physicochemical evolution of Gutaishan Au deposit, South China: Perspective from quartz geochemistry and fluid inclusions. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 119, 103382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Shao, Y.; Lai, C. Pyrite geochemistry and metallogenic implications of Gutaishan Au deposit in Jiangnan Orogen, South China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 117, 103298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, D.; Li, B.; Jiang, C. Deformation sequences, metallogenic events and ore-controlling structures at Gutaishan Au-Sb deposit in central Hunan province. Miner. Depos. 2023, 42, 229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Y. Geological characteristics and genesis of Gutaishan gold (antimony) deposit in central Hunan. Miner. Resour. Geol. 2024, 38, 847–861. [Google Scholar]

- Jianguo, Y. Alteration features and its direction of looking for the deposit in Gutaishan Au-Sb deposit, Xinhua. Hunan Geol. 1998, 17, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Xie, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X. Constraint on the genesis of Gutaishan gold deposit in central Hunan Province: Evidence from fluid inclusion and CHO isotopes. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2016, 32, 3489–3506. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Kang, L.; Li, B.; Kang, P. Geochemical Constraints on Antimony Mineralization in the Gutaishan Au–Sb Deposit, China: Insights from Trace Elements in Quartz and Sulfur Isotopes in Stibnite. Minerals 2025, 15, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Xie, B.W.; Duan, A.J.; Huang, X.J.; Ai, G.; Liu, W. Study on Geological Characteristics and Prospecting Direction of No. 3 Vein in Gutaishan Gold-antimony Deposit,Hunan Province. Mod. Min. 2024, 40, 49–53+61. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, D.; Mathur, R.; Liu, S.-A.; Liu, J.; Godfrey, L.; Wang, K.; Xu, J.; Vervoort, J. Antimony isotope fractionation in hydrothermal systems. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2021, 306, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupp, R.E. Solubility of stibnite in hydrogen sulfide solutions, speciation, and equilibrium constants, from 25 to 350 °C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1988, 52, 3005–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Jones, A.E.; Norman, C. Controls of mineral parageneses in the system Fe-Sb-SO. Econ. Geol. 1997, 92, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guodong, A.; Dai Tagen, C.M. Pyrite-arsenite-antimony type and the occurrence status of gold in gold deposits-taking gold deposits in Hunan Province as an example. Geol. Resour. 2010, 19, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Z.X. A preliminary study on gold-bearing property of stibnite in tungsten-antimony-arsenic-gold deposits in central and western Hunan. Precious Metals Geology 1992, 1, 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Large, R.R.; Meffre, S.; Burnett, R.; Guy, B.; Bull, S.; Gilbert, S.; Goemann, K.; Danyushevsky, L. Evidence for an intrabasinal source and multiple concentration processes in the formation of the Carbon Leader Reef, Witwatersrand Supergroup, South Africa. Econ. Geol. 2013, 108, 1215–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, M.; Smith, D.J.; Doyle, K.; Holwell, D.A.; Jenkin, G.R.; Barry, T.L.; Becker, J.; Rampe, J. Pyrite chemistry: A new window into Au-Te ore-forming processes in alkaline epithermal districts, Cripple Creek, Colorado. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2020, 274, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, D.D.; Large, R.R.; Bath, A.B.; Steadman, J.A.; Wu, S.; Danyushevsky, L.; Bull, S.W.; Holden, P.; Ireland, T.R. Trace element content of pyrite from the kapai slate, St. Ives Gold District, Western Australia. Econ. Geol. 2016, 111, 1297–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.; Ciobanu, C.L.; George, L.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Wade, B.; Ehrig, K. Trace element analysis of minerals in magmatic-hydrothermal ores by laser ablation inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry: Approaches and opportunities. Minerals 2016, 6, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xie, G.-Q.; Mao, J.-W.; Cook, N.J.; Wei, H.-T.; Ji, Y.-H.; Fu, B. Precise age constraints for the Woxi Au-Sb-W deposit, south China. Econ. Geol. 2023, 118, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-X.; Zhang, L.; Powell, C.M. South China in Rodinia: Part of the missing link between Australia–East Antarctica and Laurentia? Geology 1995, 23, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jahn, B.-m. Crustal evolution of southeastern China: Nd and Sr isotopic evidence. Tectonophysics 1998, 284, 101–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Liu, J.; Zheng, M.; Tang, J.; Qi, L. Provenance and tectonic setting of the Proterozoic turbidites in Hunan, South China: Geochemical evidence. J. Sediment. Res. 2002, 72, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greentree, M.R.; Li, Z.-X.; Li, X.-H.; Wu, H. Late Mesoproterozoic to earliest Neoproterozoic basin record of the Sibao orogenesis in western South China and relationship to the assembly of Rodinia. Precambrian Res. 2006, 151, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Suo, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Santosh, M.; Wang, P.; Wang, G.; Guo, L.; Yu, S.; Lan, H. Mesozoic tectono-magmatic response in the East Asian ocean-continent connection zone to subduction of the Paleo-Pacific Plate. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 192, 91–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.-F.; Wu, R.-X.; Wu, Y.-B.; Zhang, S.-B.; Yuan, H.; Wu, F.-Y. Rift melting of juvenile arc-derived crust: Geochemical evidence from Neoproterozoic volcanic and granitic rocks in the Jiangnan Orogen, South China. Precambrian Res. 2008, 163, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Deng, T.; Chi, G.; Wang, Z.; Zou, F.; Zhang, J.; Zou, S. Gold mineralization in the Jiangnan Orogenic Belt of South China: Geological, geochemical and geochronological characteristics, ore deposit-type and geodynamic setting. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 88, 565–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Yonezu, K.; Imai, A.; Tindell, T.; Li, H.; Gabo-Ratio, J.A. Trace elements mineral chemistry of sulfides from the Woxi Au-Sb-W deposit, southern China. Resour. Geol. 2022, 72, e12279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.-Z.; Zhou, M.-F. Multiple Mesozoic mineralization events in South China—An introduction to the thematic issue. Miner. Depos. 2012, 47, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruizhong, H.; Shanling, F.; Jiafei, X. Major scientific problems on low-temperature metallogenesis in South China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2016, 32, 3239–3251. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.; Fu, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, M.-F.; Fu, S.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Bi, X.; Xiao, J. The giant South China Mesozoic low-temperature metallogenic domain: Reviews and a new geodynamic model. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 137, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.-Z.; Chen, W.T.; Xu, D.-R.; Zhou, M.-F. Reviews and new metallogenic models of mineral deposits in South China: An introduction. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 137, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A’xiang, H.; Jiantang, P. Fluid inclusions and ore precipitation mechanism in the giant Xikuangshan mesothermal antimony deposit, South China: Conventional and infrared microthermometric constraints. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 95, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, W.; Sun, M.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, T. Geochronological, geochemical and geothermal constraints on petrogenesis of the Indosinian peraluminous granites in the South China Block: A case study in the Hunan Province. Lithos 2007, 96, 475–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Hu, R.; Bi, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Huang, Y. Origin of Triassic granites in central Hunan Province, South China: Constraints from zircon U–Pb ages and Hf and O isotopes. Int. Geol. Rev. 2015, 57, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Mao, J.; Li, W.; Fu, B.; Zhang, Z. Granite-related Yangjiashan tungsten deposit, southern China. Miner. Depos. 2019, 54, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.-Y.; Qiu, K.-F.; Santosh, M.; Yu, H.-C.; Jiang, X.-Y.; Zou, L.-Q.; Tang, D.-W. Fingerprinting the metal source and cycling of the world’s largest antimony deposit in Xikuangshan, China. Bulletin 2023, 135, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Chen, P.; Chen, W.; Huang, H.; Zhou, X. Single zircon LA-ICPMS U-Pb dating of Weishan granite (Hunan, South China) and its petrogenetic significance. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2006, 49, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, P.; Huang, H.; Ding, X.; Sun, T. Chronological and geochemical studies of granite and enclave in Baimashan pluton, Hunan, South China. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2007, 50, 1606–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, J.; Feng, W.; Huang, X. The geochronologic characteristics of Baimashan granite in western Hunan Province and its geotectonic significance. Earth Sci. Front. 2013, 20, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R. Large Scale Low-Temperature Metallogenesis in South China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2021; pp. 1–469. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, J. The mantle-crustal tectonic metallogenic model and ore-prospecting in the Xikuangshan antimony orefield. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 1999, 23, 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z. Research on the Finite Element Numerical Simulation of the Geodynamic Evolution Features and Characteristics of Metallogenic in Hunan Region since Mesozoic; Central South University: Changsha, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- MA, D.-s. Ore source of Sb (Au) deposits in central Hunan: I. Evidences of trace elements and experimental geochemistry. Miner. Depos. 2002, 21, 367–376. [Google Scholar]

- Shanling, F.; Ruizhong, H.; Youwei, C.; Jincheng, L. Chronology of the Longshan Au-Sb deposit in central Hunan Province: Constraints from pyrite Re-Os and zircon U-Th/He isotopic dating. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2016, 32, 3507–3517. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W. Geological-Geochemical Characteristics of Caledonian Granitoids and its Geological Significance, Hunan Province-Taking Baimashan, Xuehuading, Hongxiaoqiao Plutons as Examples; Central South University: Changsha, China, 2013; pp. 10–70. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Y. LA-ICPMS zircon U–Pb dating for Baimashan and Jintan Indosinian granitic plutons and its petrogenetic implications. Geotecton. Metallog. 2010, 34, 282–290. [Google Scholar]

- SRM 610; Trace Elements in Glass. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2012.

- Wilson, S.; Ridley, W.; Koenig, A. Development of sulfide calibration standards for the laser ablation inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry technique. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 2002, 17, 406–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochum, K.P.; Wilson, S.A.; Abouchami, W.; Amini, M.; Chmeleff, J.; Eisenhauer, A.; Hegner, E.; Iaccheri, L.M.; Kieffer, B.; Krause, J. GSD-1G and MPI-DING reference glasses for in situ and bulk isotopic determination. Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research 2011, 35, 193–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillong, M.; Hametner, K.; Reusser, E.; Wilson, S.A.; Günther, D. Preliminary characterisation of new glass reference materials (GSA-1G, GSC-1G, GSD-1G and GSE-1G) by laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry using 193 nm, 213 nm and 266 nm wavelengths. Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research 2005, 29, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BCR-2; Columbia River Basalt. United States Geological Survey (USGS): Denver, CO, USA, 2022.

- BHVO-2; Hawaiian Volcano Observatory Basalt. United States Geological Survey (USGS): Denver, CO, USA, 2022.

- AGV-2; Guano Valley Andesite. United States Geological Survey (USGS): Denver, CO, USA, 2022.

- RGM-2*-NP; Rhyolite. myStandards GmbH: Kiel, Germany, 2024.

- Powell, W.; Pearson, N.; O’Reilly, S. GLITTER: Data reduction software for laser ablation ICP-MS/Ed. PJ Sylvester. Laser Ablation ICP-MS Earth Sci. 2008, 40, 308–311. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, P.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Tang, G.; Xiang, Z. Trace element compositions of pyrite and stibnite: Implications for the genesis of antimony mineralization in the Yangla Cu skarn deposit, Northwestern Yunnan, China. Acta Geochim. 2024, 43, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.J.; Ciobanu, C.L.; Pring, A.; Skinner, W.; Shimizu, M.; Danyushevsky, L.; Saini-Eidukat, B.; Melcher, F. Trace and minor elements in sphalerite: A LA-ICPMS study. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 4761–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deditius, A.P.; Utsunomiya, S.; Reich, M.; Kesler, S.E.; Ewing, R.C.; Hough, R.; Walshe, J. Trace metal nanoparticles in pyrite. Ore Geol. Rev. 2011, 42, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, C.; Cook, N.; Kelson, C.; Guerin, R.; Kalleske, N.; Danyushevsky, L. Trace element heterogeneity in molybdenite fingerprints stages of mineralization. Chem. Geol. 2013, 347, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Gilbert, S.; Liu, J.J.; Shi, W.S. LA–ICP–MS and EPMA studies on the Fe–S–As minerals from the Jinlongshan gold deposit, Qinling Orogen, China: Implications for ore-forming processes. Geol. J. 2014, 49, 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L.; Cook, N.J.; Wade, B.P. Trace and minor elements in galena: A reconnaissance LA-ICP-MS study. Am. Mineral. 2015, 100, 548–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longerich, H.P.; Jackson, S.E.; Günther, D. Inter-laboratory note. Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometric transient signal data acquisition and analyte concentration calculation. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 1996, 11, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Hu, R.; Bi, X.; Sullivan, N.A.; Yan, J. Trace element composition of stibnite: Substitution mechanism and implications for the genesis of Sb deposits in southern China. Appl. Geochem. 2020, 118, 104637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousov, I.; Large, R.; Meffre, S.; Danyushevsky, L.; Steadman, J.; Beardsmore, T. Pyrite compositions from VHMS and orogenic Au deposits in the Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia: Implications for gold and copper exploration. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 79, 474–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H. Trace elements in pyrite from orogenic gold deposits: Implications for metallogenic mechanism. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2023, 39, 2330–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.C.; Lockwood, P.V.; Ashley, P.M.; Tighe, M. The chemistry and behaviour of antimony in the soil environment with comparisons to arsenic: A critical review. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, C.L.; Melfos, V.; Voudouris, P.; Papadopoulou, L.; Spry, P.G.; Peytcheva, I.; Dimitrova, D.; Stefanova, E. A fluid inclusion and critical/rare metal study of epithermal quartz-stibnite veins associated with the Gerakario Porphyry Deposit, Northern Greece. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, H.; Yonezu, K.; Imai, A.; Tindell, T. In-situ trace elements and sulfur isotopic analyses of stibnite: Constraints on the genesis of Sb/Sb-polymetallic deposits in southern China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2023, 247, 107177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.-T.; Xia, Y.; Gregory, D.D.; Steadman, J.A.; Tan, Q.-P.; Xie, Z.-J.; Liu, X.-J. Multistage pyrites in the Nibao disseminated gold deposit, southwestern Guizhou Province, China: Insights into the origin of Au from textures, in situ trace elements, and sulfur isotope analyses. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 122, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Xian, H.; Zhu, J.; Tan, W.; Wu, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Qiu, K.; Zhu, R.; Henry Teng, H. Evaluating the physicochemical conditions for gold occurrences in pyrite. Am. Mineral. 2023, 108, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, P.; Holliger, P.; Boiron, M.; Cathelineau, M.; Wagner, F. New Improvements in the Characterization of Refractory Gold in Pyrites: An Electron Microprobe, Mössbauer Spectrometry and ion Microprobe Study; Instituto Brasileiro de Mineracao (IBRAM): Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, M.; Kesler, S.E.; Utsunomiya, S.; Palenik, C.S.; Chryssoulis, S.L.; Ewing, R.C. Solubility of gold in arsenian pyrite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2005, 69, 2781–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shao, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, K.; He, M.; Chen, Z. Ore-forming process and ore genesis of the Wangu gold deposit in the Jiangnan orogenic Belt, South China: Constraints from pyrite textures, trace elements and in-situ sulfur isotopes composition. Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 178, 106485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, Q.-H.; Evans, N.J.; Zhou, Z.-K.; Kong, H.; Xi, X.-S.; Lin, Z.-W. Geochemistry and geochronology of the Banxi Sb deposit: Implications for fluid origin and the evolution of Sb mineralization in central-western Hunan, South China. Gondwana Res. 2018, 55, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Lai, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; He, H.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Wang, C.; Wen, C. Material Source and Genesis of the Daocaowan Sb Deposit in the Xikuangshan Ore Field: LA-ICP-MS Trace Elements and Sulfur Isotope Evidence from Stibnite. Minerals 2022, 12, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xie, G.; Yuan, L. Discussion of the genetic relations between W and Sb-Au mineralization of Xiangzhong ore district: Constraints from Sr-Nd-HO isotopic compositions of the Caojiaba W and Longshan Sb-Au deposits. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2023, 39, 1847–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, C.; Lu, W.; Guo, A.; Xiao, R.; Wei, H.; Tan, S.; Jia, P. He–Ar–Sr isotope geochemistry of ore–forming fluids in the gutaishan Au–Sb deposit in hunan province and its significance for deep prospecting. Acta Geosci. Sin. 2020, 41, 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bralia, A.; Sabatini, G.; Troja, F. A revaluation of the Co/Ni ratio in pyrite as geochemical tool in ore genesis problems: Evidences from southern Tuscany pyritic deposits. Miner. Depos. 1979, 14, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, O.L. Pyrite composition and ore genesis in the Prince Lyell copper deposit, Mt Lyell mineral field, western Tasmania, Australia. Ore Geol. Rev. 1996, 10, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.; Vokes, F.; Solberg, T. Pyrite: Physical and chemical textures. Miner. Depos. 1998, 34, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Grguric, B.; Mumm, A.S. Genetic implications of pyrite chemistry from the Palaeoproterozoic Olary Domain and overlying Neoproterozoic Adelaidean sequences, northeastern South Australia. Ore Geol. Rev. 2004, 25, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Large, R.R.; Danyushevsky, L.; Hollit, C.; Maslennikov, V.; Meffre, S.; Gilbert, S.; Bull, S.; Scott, R.; Emsbo, P.; Thomas, H. Gold and trace element zonation in pyrite using a laser imaging technique: Implications for the timing of gold in orogenic and Carlin-style sediment-hosted deposits. Econ. Geol. 2009, 104, 635–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, D.D.; Large, R.R.; Halpin, J.A.; Baturina, E.L.; Lyons, T.W.; Wu, S.; Danyushevsky, L.; Sack, P.J.; Chappaz, A.; Maslennikov, V.V. Trace element content of sedimentary pyrite in black shales. Econ. Geol. 2015, 110, 1389–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafagna, F.; Jugo, P.J. An experimental study on the geochemical behavior of highly siderophile elements (HSE) and metalloids (As, Se, Sb, Te, Bi) in a mss-iss-pyrite system at 650 °C: A possible magmatic origin for Co-HSE-bearing pyrite and the role of metalloid-rich phases in the fractionation of HSE. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2016, 178, 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.-J.; Wang, W.-S.; Liu, Q.-Q.; Zhang, Y. Trace element analysis of pyrite from the Zhengchong gold deposit, Northeast Hunan Province, China: Implications for the ore-forming process. Minerals 2018, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koglin, N.; Frimmel, H.E.; Lawrie Minter, W.; Brätz, H. Trace-element characteristics of different pyrite types in Mesoarchaean to Palaeoproterozoic placer deposits. Miner. Depos. 2010, 45, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.V.; Large, R.R.; Bull, S.W.; Maslennikov, V.; Berry, R.F.; Fraser, R.; Froud, S.; Moye, R. Pyrite and pyrrhotite textures and composition in sediments, laminated quartz veins, and reefs at Bendigo gold mine, Australia: Insights for ore genesis. Econ. Geol. 2011, 106, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deol, S.; Deb, M.; Large, R.R.; Gilbert, S. LA-ICPMS and EPMA studies of pyrite, arsenopyrite and loellingite from the Bhukia-Jagpura gold prospect, southern Rajasthan, India: Implications for ore genesis and gold remobilization. Chem. Geol. 2012, 326, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Deng, J.; Chen, H.-y.; Yang, L.-q.; Cooke, D.; Danyushevsky, L.; Gong, Q.-j. LA-ICP-MS trace element analysis of pyrite from the Chang’an gold deposit, Sanjiang region, China: Implication for ore-forming process. Gondwana Res. 2014, 26, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.-M.; Hu, R.-Z.; Huang, X.-W.; Gao, J.-F.; Sasseville, C. The origin of the carbonate-hosted Huize Zn–Pb–Ag deposit, Yunnan province, SW China: Constraints from the trace element and sulfur isotopic compositions of pyrite. Mineral. Petrol. 2019, 113, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, I.; Large, R.R.; Bull, S.; Gregory, D.G.; Stepanov, A.S.; Ávila, J.; Ireland, T.R.; Corkrey, R. Pyrite trace-element and sulfur isotope geochemistry of paleo-mesoproterozoic McArthur Basin: Proxy for oxidative weathering. Am. Mineral. 2019, 104, 1256–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, B.A. Trace-element contents and partitioning of elements in ore minerals from the CSA Cu-Pb-Zn deposit, Australia, and implications for ore genesis. Can. Mineral. 1989, 27, 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.-X.; Frimmel, H.E.; Jiang, S.-Y.; Dai, B.-Z. LA-ICP-MS trace element analysis of pyrite from the Xiaoqinling gold district, China: Implications for ore genesis. Ore Geol. Rev. 2011, 43, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslennikov, V.; Maslennikova, S.; Large, R.; Danyushevsky, L. Study of trace element zonation in vent chimneys from the Silurian Yaman-Kasy volcanic-hosted massive sulfide deposit (Southern Urals, Russia) using laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICPMS). Econ. Geol. 2009, 104, 1111–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S.; Wang, D.; Yu, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zha, Z.; Wang, J. Trace elements and sulfur isotopes of sulfides in the Zhangquanzhuang gold deposit, Hebei Province, China: Implications for physicochemical conditions and mineral deposition mechanisms. Minerals 2020, 10, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuz, A.-K.; Mönch, H.; Johnson, C.A. Sorption of Sb (III) and Sb (V) to goethite: Influence on Sb (III) oxidation and mobilization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 7277–7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockmann, K.; Schulin, R. Leaching of antimony from contaminated soils. In Competitive Sorption and Transport of Heavy Metals in Soils; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; Volume 119. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Li, X.-H.; Ge, W.; Li, Z.-X. Age and origin of middle Neoproterozoic mafic magmatism in southern Yangtze Block and relevance to the break-up of Rodinia. Gondwana Res. 2007, 12, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, J.M. CHNOSZ: Thermodynamic calculations and diagrams for geochemistry. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, H.C. Summary and critique of the thermodynamic properties of rock-forming minerals. Am. J. Sci. A 1978, 278, 1–229. [Google Scholar]

- Robie, R.A.; Hemingway, B.S. Thermodynamic Properties of Minerals and Related Substances at 298.15 K and 1 bar (105 Pascals) Pressure and at Higher Temperatures; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume 2131. [Google Scholar]

- Tagirov, B.; Akinfiev, N.; Zotov, A. Gold (I) complexation in chloride hydrothermal fluids. Geol. Ore Depos. 2024, 66, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagirov, B.R.; Akinfiev, N.N.; Tarnopolskaia, M.E.; Nikolaeva, I.Y.; Zlivko, I.Y.; Volchenkova, V.A.; Koroleva, L.A.; Zotov, A.V. Gold in sulfide fluids revisited. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2024, 406, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shock, E.L.; Sassani, D.C.; Willis, M.; Sverjensky, D.A. Inorganic species in geologic fluids: Correlations among standard molal thermodynamic properties of aqueous ions and hydroxide complexes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1997, 61, 907–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cook, N.J.; Xie, G.-Q.; Mao, J.-W.; Ciobanu, C.L.; Li, J.-W.; Zhang, Z.-Y. Textures and trace element signatures of pyrite and arsenopyrite from the Gutaishan Au–Sb deposit, South China. Miner. Depos. 2019, 54, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Z.; Ji, S.; Aimin, G.; Pengyuan, J.; Wen, L.; Hantao, W.; Ding, G.; Yi, C. A comparative study of the ore-forming fluids of the typical gold-antimony deposits along Middle Xuefeng arc structure belt. Geol. China 2020, 47, 1241–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, M.; Courjault-Radé, P.; Tollon, F. The massive stibnite veins of the French Palaeozoic basement: A metallogenic marker of Late Variscan brittle extension. Terra Nova 1992, 4, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, S.G.; Lüders, V. PTX conditions of hydrothermal fluids and precipitation mechanism of stibnite-gold mineralization at the Wiluna lode-gold deposits, Western Australia: Conventional and infrared microthermometric constraints. Miner. Depos. 2003, 38, 936–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotov, A.; Shikina, N.; Akinfiev, N. Thermodynamic properties of the Sb (III) hydroxide complex Sb (OH)3(aq) at hydrothermal conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 1821–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, P.; Creagh, C.; Ryan, C. Invisible gold in ore and mineral concentrates from the Hillgrove gold-antimony deposits, NSW, Australia. Miner. Depos. 2000, 35, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Cook, N. Late-Variscan antimony mineralisation in the Rheinisches Schiefergebirge, NW Germany: Evidence for stibnite precipitation by drastic cooling of high-temperature fluid systems. Miner. Depos. 2000, 35, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, S.; Ning, Y.; Xiao, L.; Huang, K.; Chen, S.; Zhu, X.; He, H.; Yu, M. Elemental Geochemical Analysis for the Gold–Antimony Segregation in the Gutaishan Deposit: Insights from Stibnite and Pyrite. Geosciences 2025, 15, 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120462

Lu S, Ning Y, Xiao L, Huang K, Chen S, Zhu X, He H, Yu M. Elemental Geochemical Analysis for the Gold–Antimony Segregation in the Gutaishan Deposit: Insights from Stibnite and Pyrite. Geosciences. 2025; 15(12):462. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120462

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Shiyi, Yongyun Ning, Liang Xiao, Ke Huang, Siqi Chen, Xuan Zhu, Hao He, and Miao Yu. 2025. "Elemental Geochemical Analysis for the Gold–Antimony Segregation in the Gutaishan Deposit: Insights from Stibnite and Pyrite" Geosciences 15, no. 12: 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120462

APA StyleLu, S., Ning, Y., Xiao, L., Huang, K., Chen, S., Zhu, X., He, H., & Yu, M. (2025). Elemental Geochemical Analysis for the Gold–Antimony Segregation in the Gutaishan Deposit: Insights from Stibnite and Pyrite. Geosciences, 15(12), 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120462