1. Introduction

Recent experimental, numerical and data-driven studies have demonstrated that a rigorous treatment of unsaturated soil behaviour is essential for reliable analysis and design of modern geotechnical systems, including slopes, pavements, retaining structures and mine rehabilitation works [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The measurement of soil suction and corresponding moisture content, which are the most relevant state variables of unsaturated soils, is fundamental to defining the soil-water retention curve (SWRC). Both suction and moisture content are crucial in governing the thermo-hydro-mechanical behaviour of unsaturated soils, making it essential to measure them accurately. Since the mid-1900s, several laboratory techniques have been developed to obtain SWRC, and these can broadly be categorised into suction measurement methods and suction control techniques.

Suction measurement techniques include direct methods such as low and high-suction tensiometers [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], and indirect methods such as psychrometers [

12,

13,

14], filter paper [

14,

15,

16], chilled-mirror hygrometer [

17,

18], and conductivity sensors [

19,

20,

21]. Suction control techniques include axis-translation method, the vapour equilibrium technique (VET) [

22,

23], and the osmotic technique [

24]. Among these, the axis-translation method has become the most widely adopted laboratory technique for controlling suction and determining the SWRC of unsaturated soils in the low suction range [

25,

26,

27]. However, some studies have highlighted limitations of this method, including the effects of elevated air pressure on pore-water cavitation, occlusion of the air phase, and adsorptive suction, as well as associated experimental challenges [

28,

29,

30]. The VET controls the total suction of soil specimens by equilibrating them with a salt solution of known relative humidity in a closed chamber. Despite its effectiveness, difficulties have been reported in maintaining thermal equilibrium between the specimen and the chamber, as well as discontinuities in suction values when using saturated salt solutions [

22,

30]. In contrast, the osmotic method has emerged as a relatively simple, reliable, and alternative approach for controlling suction, without requiring a closed chamber or air pressure control [

27,

31].

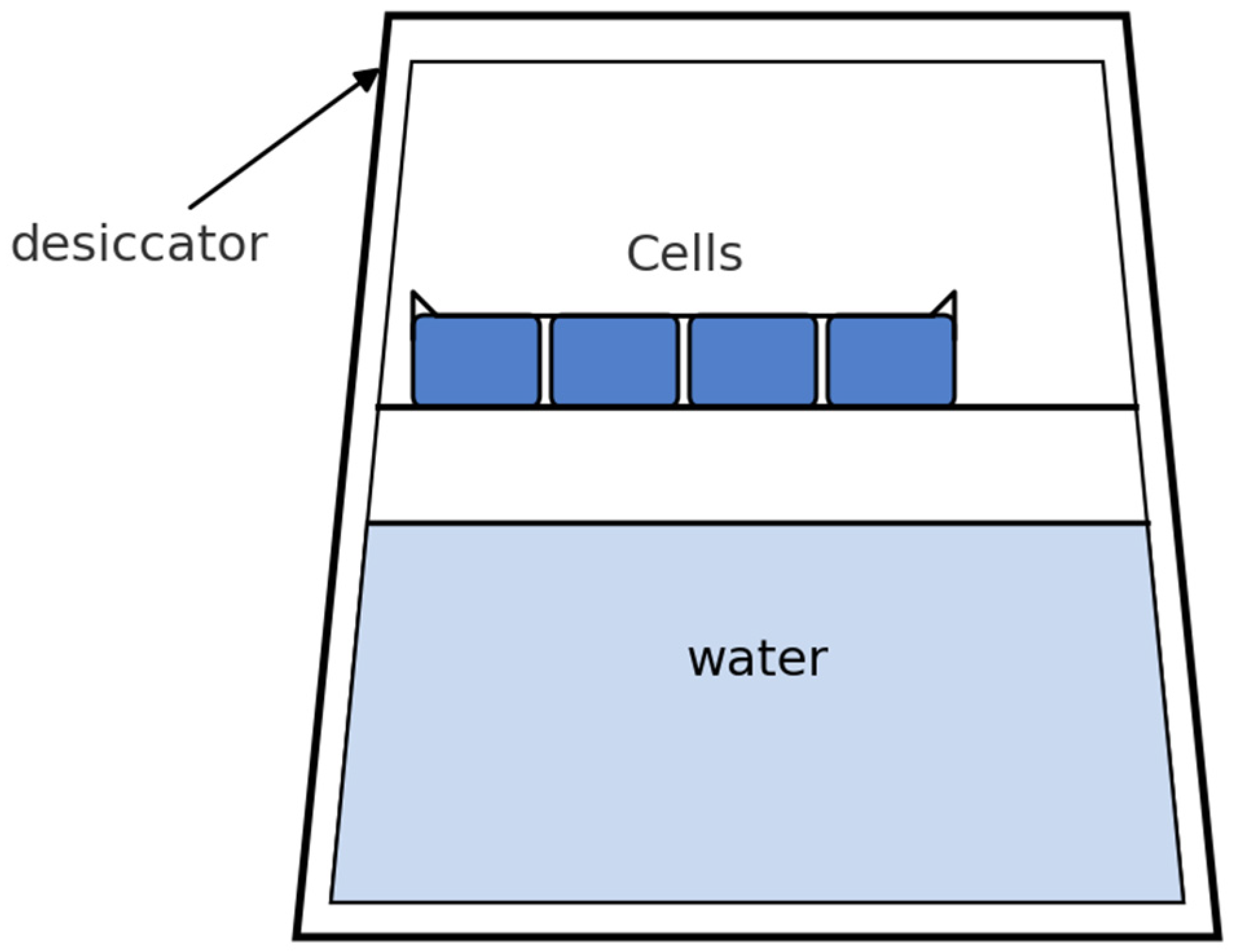

The osmotic technique controls matric suction by placing the soil specimen in contact with an aqueous solution separated by a semi-permeable membrane, which allows moisture transfer through osmosis while restricting solute passage [

24,

32]. The most commonly used solute is polyethylene glycol (PEG). The equilibrium suction achieved depends on the concentration of the PEG solution: higher concentrations correspond to higher suction values, up to a maximum reported value of about 10 MPa [

33]. Although PEG is widely used as the osmotic agent in this method, several limitations and constraints have been reported. For example, significant variations in calibration curves for the same molecular-weight PEG have been observed among different researchers [

31,

33]. Han et al. [

34] reported that PEG undergoes oxidative degradation in the presence of air, reducing its molecular weight. Tarantino and Mongiovi [

35] observed that, beyond 1 MPa suction, some PEG molecules penetrated the soil specimen, leading to inaccurate measurements. This problem arises because, at higher suctions, PEG molecules break down into smaller units that can pass through the semipermeable membrane [

35]. In addition, PEG degradation has been linked to interactions with ions expelled from the pore water of soil specimens [

32]. Microbial growth in the PEG solution, caused by penetration from soil specimens through the semi-permeable membrane, has also been reported by several researchers [

36,

37,

38]. To overcome these drawbacks, alternative solutes have been explored by several researchers. For instance, Bulolo and Leong [

31] used NaCl as an alternative to PEG in the osmotic technique to induce matric suction of up to 1.3 MPa in the soil specimen.

In addition to the limitations of PEG, the commonly used cellulosic semi-permeable membranes have also been associated with critical challenges. The membranes were observed to undergo microbial degradation when left in long-term contact with soil specimens [

30,

31,

39]. Furthermore, Tripathy et al. [

32] reported that PEG molecules could infiltrate the soil specimen due to the enlargement of membrane pores caused by mechanical strain. To address these issues, several alternative membranes have been investigated in recent years, including polyether sulfonated (PES) membranes [

39,

40,

41], polysulfones, polyamides [

42], and reverse osmosis (RO) membranes [

31].

To situate our approach within established practice,

Table 1 provides a concise, side-by-side comparison of the novel poly-potassium salt (PPS) osmotic technique used in this study and the conventional polyethylene glycol (PEG) osmotic method commonly applied to SWRC testing. The attributes were chosen to reflect factors that most affect test quality and practicality: membrane requirement, risk of solute intrusion into the specimen, thermal sensitivity over 20–30 °C, suction stability at high values, setup and maintenance needs, equilibration behaviour, and biofouling risk. In brief, PPS operates without a semi-permeable membrane (we use only a physical separator), which simplifies assembly and removes common PEG failure modes (membrane fouling, leakage, and added mass-transfer resistance). Within our tested temperature window, PPS exhibited modest, predictable thermal drift and stable high-suction control with consistent early-time kinetics, supporting reliable and repeatable SWRC measurements in compacted kaolin. The comparison is intended to clarify the practical rationale for adopting PPS in this work while acknowledging that broader chemistry/transport benchmarking across wider conditions remains a valuable direction for future studies.

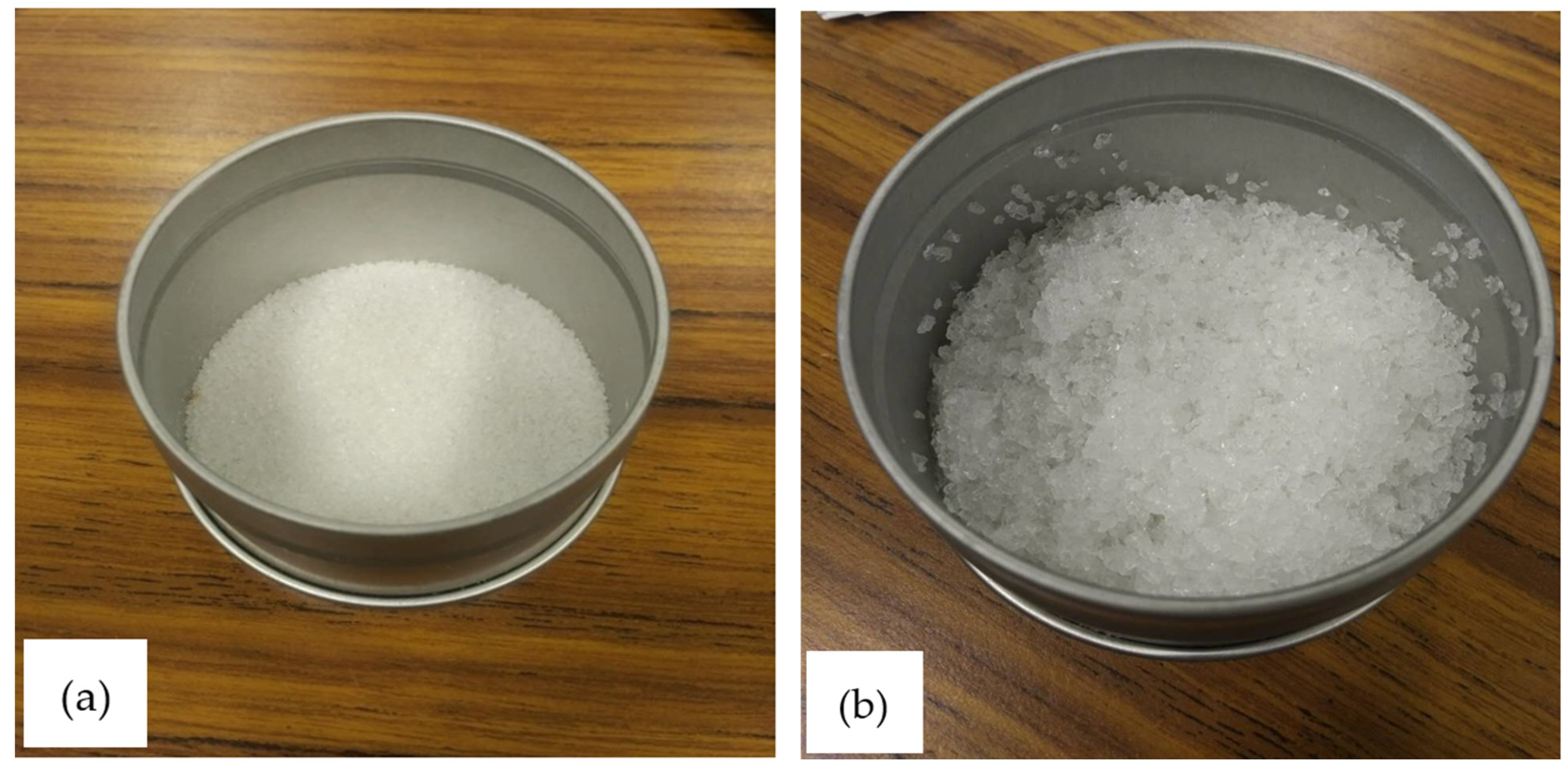

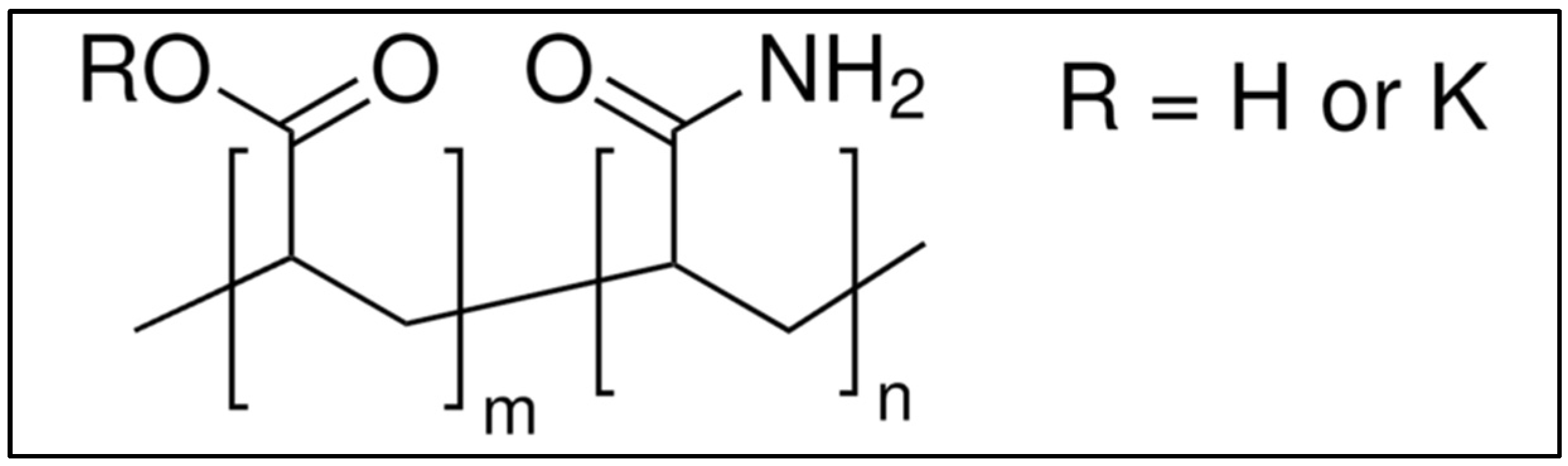

The present study investigates the use of a novel potassium salt, poly (acrylamide-co-acrylic acid), as an alternative to PEG. This material, synthesised through free radical polymerisation of acrylamide and acrylic acid in the presence of potassium, belongs to the class of superabsorbent polymers and has recently been applied in osmotic tensiometers for matric suction measurements [

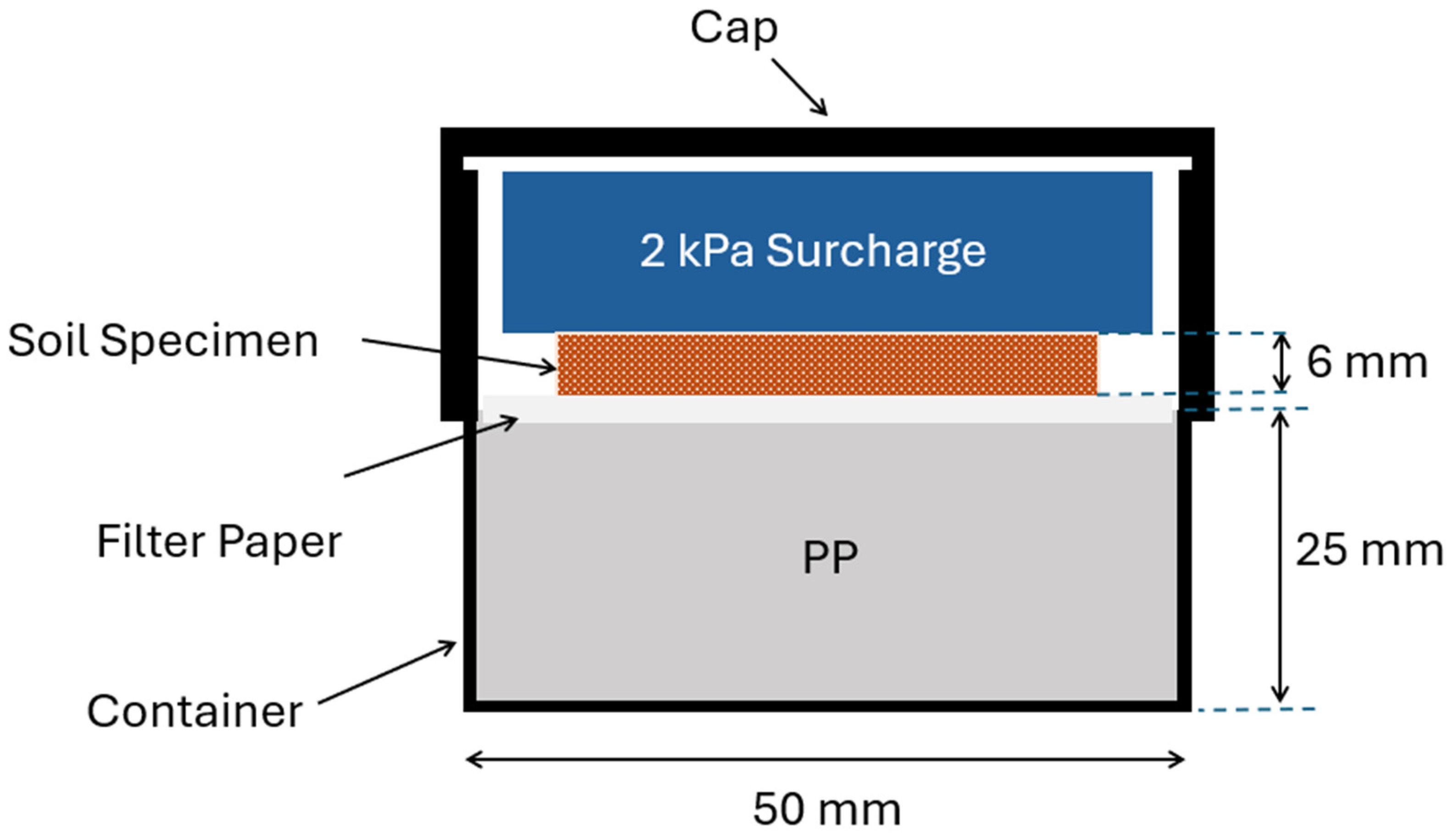

43]. In the current work, this poly potassium (PP) salt is evaluated for its effectiveness in determining the soil-water retention curve (SWRC) of kaolin, in combination with a low-cost grade 42 filter paper used as a physical separator in place of the conventional cellulosic semi-permeable membrane.

In this study, PP was selected as the osmotic medium because its cross-linked hydrogel structure eliminates several practical limitations associated with PEG-based methods. Unlike PEG solutions, PP does not require a semi-permeable membrane, liquid circulation, or tight sealing to prevent leakage. Its solid-state form also reduces issues such as membrane clogging, solution degradation, and temperature-driven density variations. Moreover, PP provides a stable and reproducible water activity that can be calibrated directly using WP4C, allowing consistent suction control within the tested range.

Grade-42 filter paper was used as the interface layer because it provides uniform and well-characterised pore size distribution, good chemical compatibility with the PP hydrogel, and sufficient mechanical strength to maintain intimate contact between the soil and the PP layer during equilibration. Importantly, the filter paper does not serve as a semi-permeable membrane, so it avoids the clogging, osmotic back-pressure, and permeability decay issues commonly observed in PEG–membrane systems. These characteristics collectively justify the choice of PP and Grade-42 filter paper as a membrane-free alternative that directly addresses several long-standing limitations of conventional osmotic techniques.

3. Results

3.1. Osmotic Behaviour of Poly Potassium (PP)

The osmotic calibration of Poly Potassium (PP) solutions was conducted to establish their capability to generate stable suctions over a broad range.

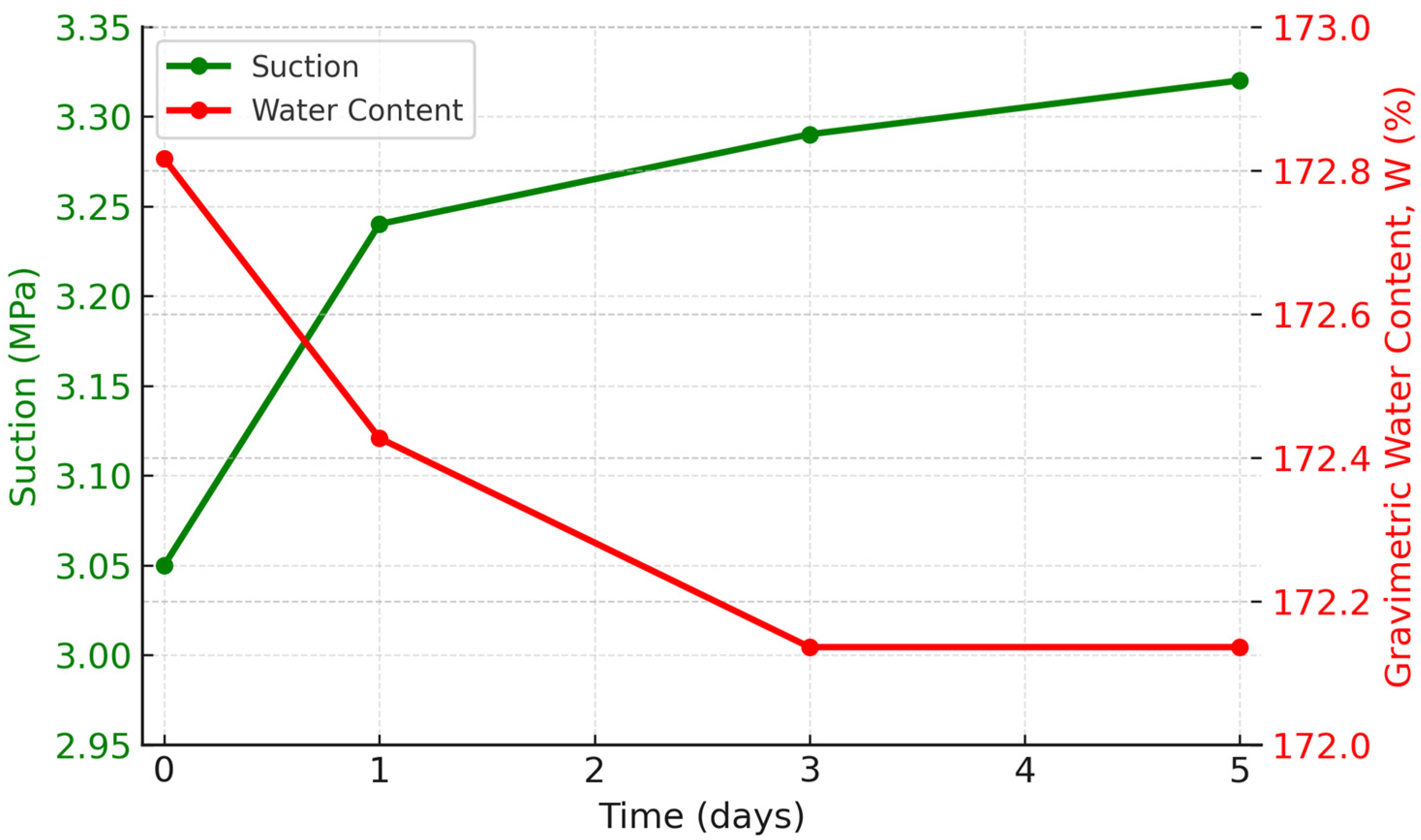

Figure 7 illustrates the temporal evolution of total suction and gravimetric water content (W) for the soil specimen subjected to a PP-controlled osmotic environment within a sealed cell over a five-day equilibration period. The imposed suction, initially near 3.0 MPa, increased asymptotically to approximately 3.4 MPa within the first two days, beyond which variations remained below 0.05 MPa, indicating attainment of hydraulic equilibrium. Correspondingly, the specimen’s water content decreased from about 176% to 170%, suggesting minor desaturation due to the osmotic gradient imposed by the PP medium. The parallel stabilisation trends of suction and specimen’s water content confirmed that equilibrium was achieved rapidly, satisfying the adopted equilibrium criterion (|Δm|/m < 0.1% over consecutive 24 h periods). The smooth evolution of both parameters demonstrates the reproducibility and stability of the PP-based method, reflecting negligible vapour-phase lag and minimal hysteretic effects. This response verifies the efficiency of the set-up in maintaining a constant total suction and ensuring isothermal equilibrium across the soil–polymer interface.

In contrast, the gravimetric water contents shown in

Figure 7 (≈172–173%) correspond to the swollen PP hydrogel, which has a much higher water-holding capacity than the compacted kaolin reported in

Table 4.

In this study, the total suction measured by the WP4C for the PP–water specimens is interpreted as the osmotic suction of the PP gel, ψπ, because no air phase or capillary menisci are present in the gel. Under isothermal conditions, this osmotic suction is transmitted across the semi-permeable membrane and is taken as equal in magnitude to the matric suction applied to the soil specimen (s ≈ −ψπ). The calibration in

Figure 7, therefore, provides the direct relationship between PP water content and the suction imposed on the kaolin specimens in the subsequent SWRC tests.

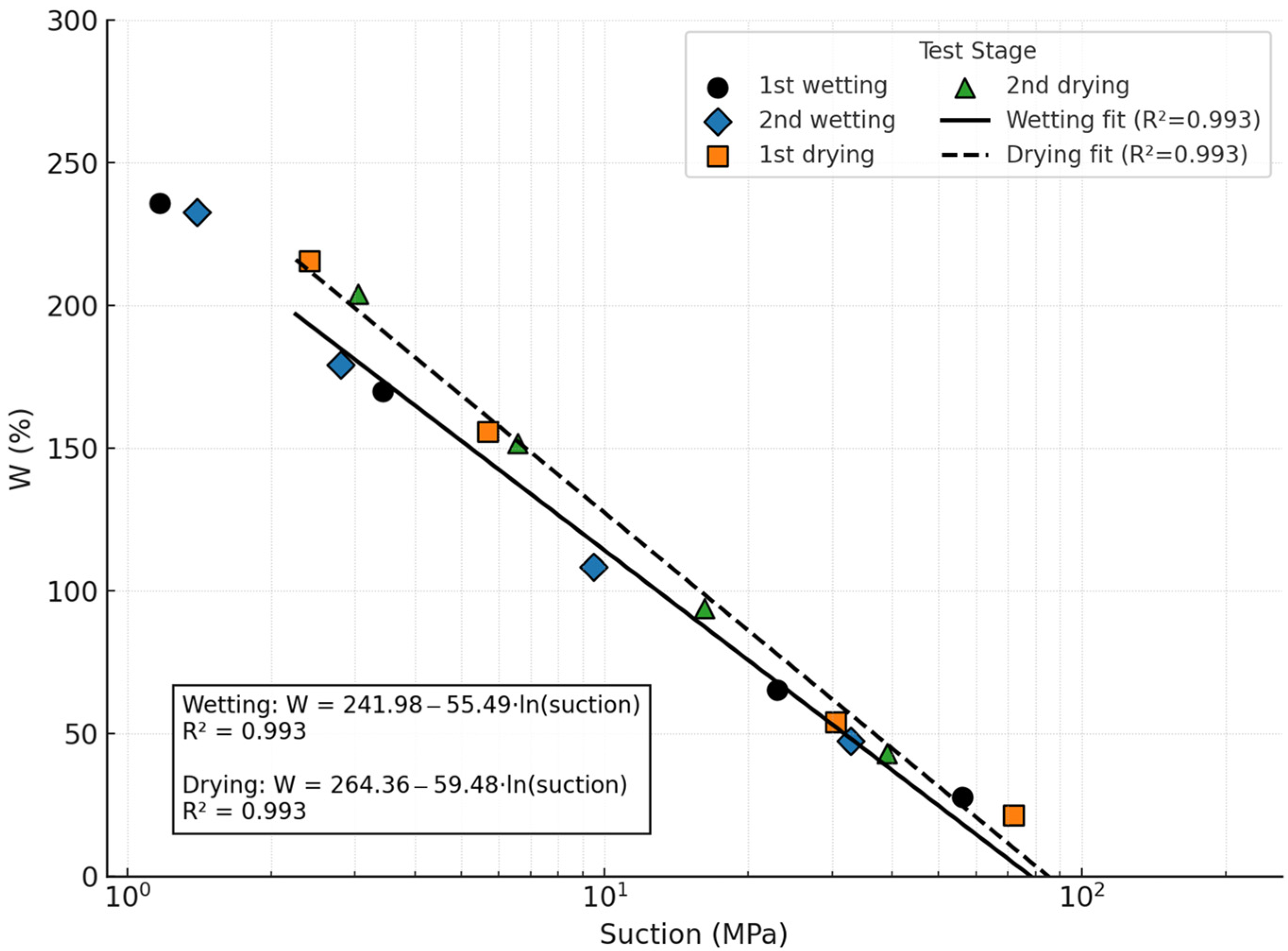

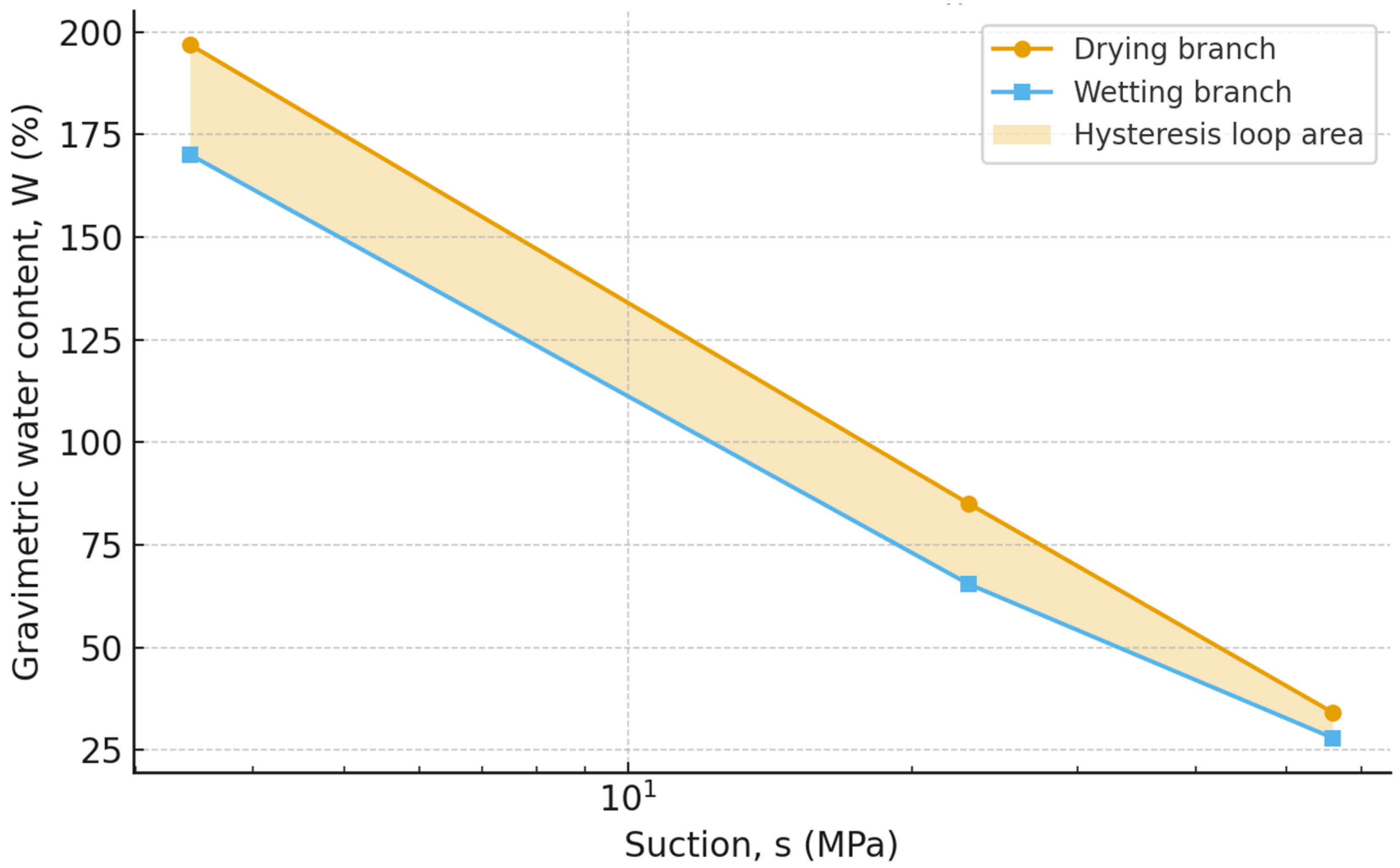

Figure 8 illustrates the water retention characteristics of the kaolin under sequential wetting and drying cycles. Both wetting and drying paths show a clear logarithmic decline in water content with increasing suction, following highly correlated regressions (R

2 = 0.993 for both paths). The fitted equations, Wetting: W = 241.98–55.49·ln(suction) and Drying: W = 264.36–59.48·ln(suction), accurately describe the experimental data over the suction range of approximately 1–70 MPa. The similarity in slopes between the wetting and drying curves indicates that the hydraulic behaviour is largely reversible, with only minor hysteresis evident at intermediate suctions (10–30 MPa). The small offset between the two paths, with slightly higher water contents during drying, reflects typical capillary effects related to pore-air entrapment and interfacial tension during desorption. Overall, the consistent trend across the first and second wetting/drying stages confirms excellent repeatability and suction control, demonstrating that the polymer-based method provides stable equilibrium and reproducible water retention behaviour across multiple hydraulic cycles.

In this study, the hysteresis observed in the SWRC is interpreted as being primarily soil-controlled rather than polymer-controlled. Hysteresis in kaolin is expected due to well-known mechanisms such as irreversible changes in pore structure, ink-bottle effects and contact-angle differences between drying and wetting paths. By contrast, the PP hydrogel used as the osmotic medium may exhibit only a minor path dependence in its swelling/deswelling response, and our independent calibration did not reveal any systematic difference between drying and wetting beyond the experimental scatter. The magnitude and shape of the hysteresis obtained with the PP method are consistent with those measured using the WP4C device, indicating that the polymer does not govern the overall hysteretic behaviour. For conventional PEG solutions commonly used in osmotic suction control, the suction–concentration relationship is generally treated as essentially single-valued, and significant hysteresis is not reported; therefore, the hysteresis reported here should be attributed mainly to the soil.

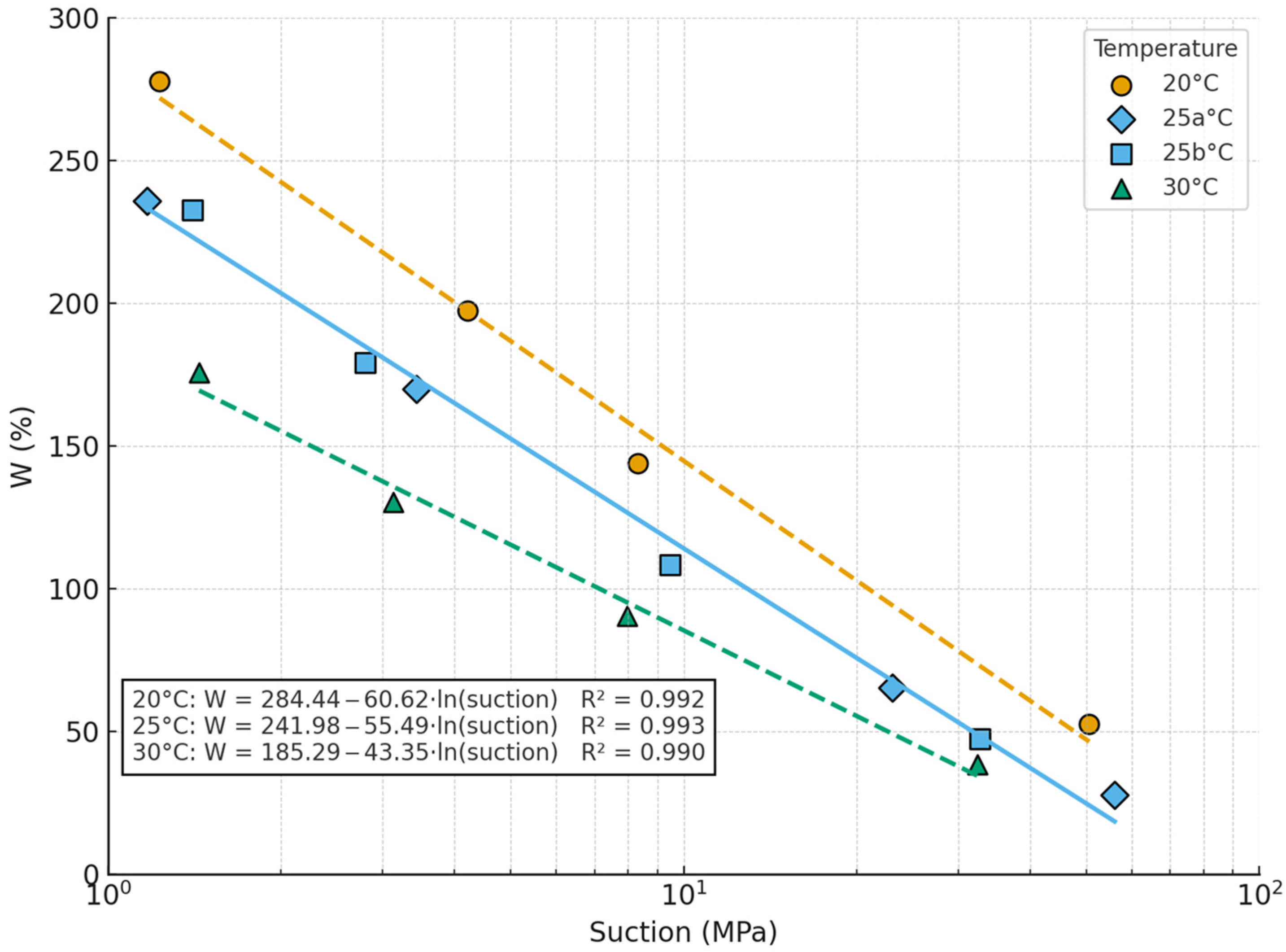

Figure 9 presents the water retention characteristics of the tested soil–polymer system at 20 °C, 25 °C, and 30 °C, plotted as the relationship between gravimetric water content (W) and total suction (MPa) on a logarithmic scale. The datasets labelled 25a and 25b correspond to independent duplicate tests conducted at 25 °C to assess experimental reproducibility. Their near-identical trends demonstrate excellent repeatability of the polymer-controlled suction technique, confirming that equilibrium was reliably achieved. All three temperature curves exhibit a strong logarithmic decline in water content with increasing suction, and coefficients of determination R

2 exceeding 0.99, validating the applicability of the logarithmic equation to describe the hydraulic behaviour.

Thermally, the WRCs exhibit a consistent downward shift with increasing temperature, indicating that at a given suction, the water content decreases as the temperature rises. This trend arises from thermodynamic and physicochemical mechanisms: (i) higher temperature reduces surface tension of pore water, thereby lowering the capillary pressure required to drain pores of a given radius; (ii) elevated temperature increases vapor pressure and molecular kinetic energy, which enhances the rate of desorption and decreases water potential; and (iii) reduced hydrogen-bond strength at higher temperatures lowers the soil’s capacity to retain adsorbed water on particle surfaces. The fitted equations, W(20 °C) = 284.44–60.62 ln(suction), W(25 °C) = 241.98–55.49 ln(suction), and W(30 °C) = 185.29–43.35 ln(suction), reflect these effects quantitatively: both the intercept and slope decrease with temperature, indicating reduced initial saturation and weaker suction sensitivity in the higher-temperature curves. Overall, the near-parallel spacing of the WRCs confirms that the temperature effect primarily alters the energy state of water without significantly modifying pore-size distribution, demonstrating the method’s precision and the material’s stable hydraulic structure across thermal variations.

Another key outcome was the demonstration of thermal robustness in the suction–water content behaviour of the PP-controlled system. As shown in

Figure 9, the logarithmic water retention curves between 20 °C and 30 °C exhibited only minor shifts in both slope and intercept, indicating that the relationship between suction and water content remained largely invariant with temperature. This behaviour confirms that the PP maintains a stable water activity–suction relationship across moderate thermal variations, a property rarely achieved by conventional osmotic techniques. In typical PEG-based systems, temperature fluctuations of even a few degrees can significantly alter osmotic potential due to changes in solute activity and solution density, necessitating continuous correction or tight thermal control. In contrast, the polymer-based system used here exhibits negligible sensitivity to thermal changes, as the water activity of the hydrated polymer is governed primarily by its internal polymer–water equilibrium rather than external solution thermodynamics. This inherent thermal stability minimises calibration errors, reduces uncertainty in imposed suction, and ensures equilibrium reliability during long-duration tests, thereby establishing PP as a practical and resilient alternative for geotechnical applications where maintaining constant laboratory temperature is challenging.

3.2. Equilibrium Time of Kaolin Specimens

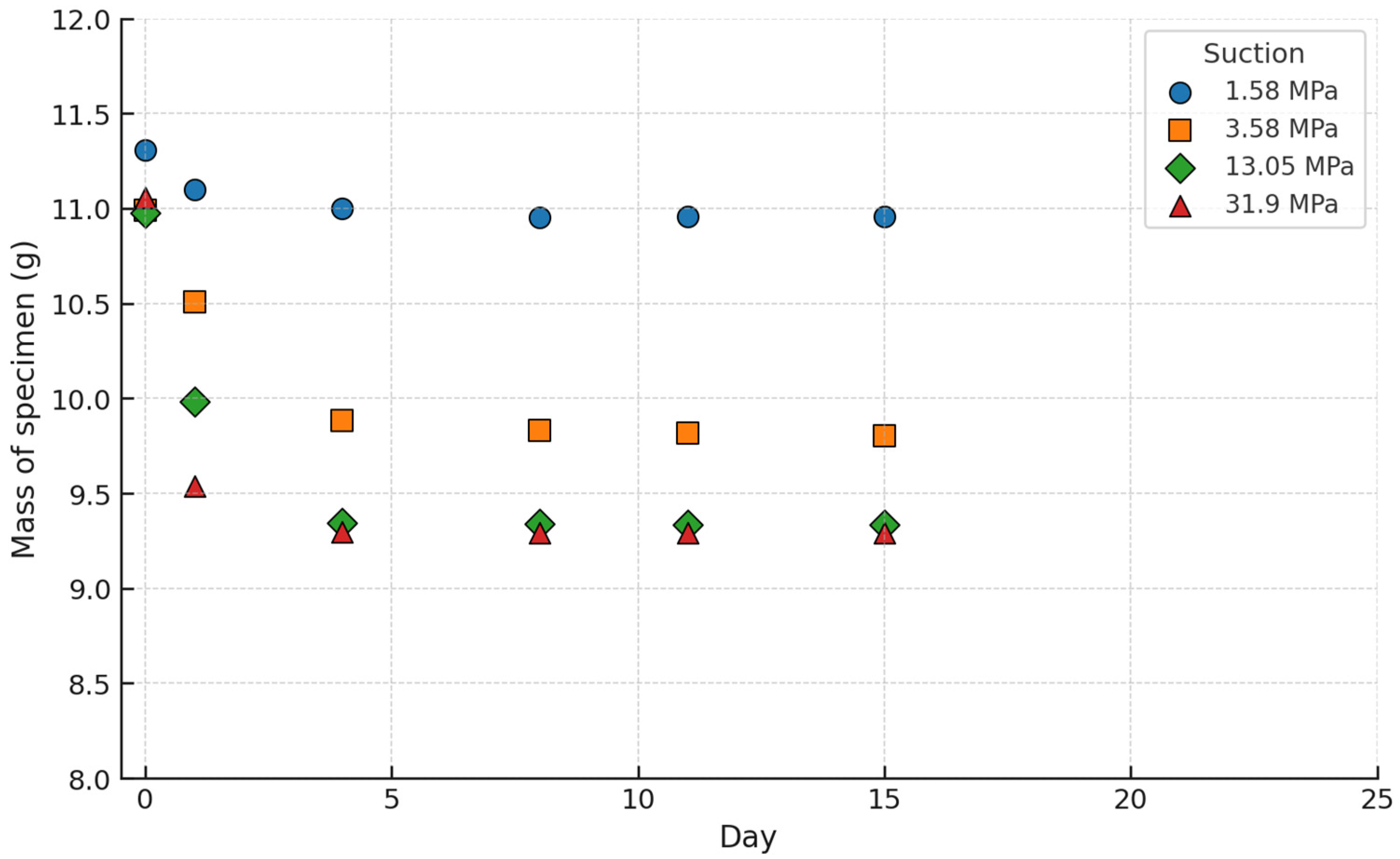

Figure 10 illustrates the mass evolution of soil specimens subjected to different imposed suctions (1.58, 3.58, 13.05, and 31.9 MPa) over 15 days, highlighting the equilibration process under polymer-controlled suction. The data show a rapid mass reduction during the first few days, followed by stabilisation beyond approximately 8 days, indicating the attainment of suction equilibrium between the soil specimens and the PP. At low suction (1.58 MPa), the specimen mass remained nearly constant at around 10.96–11.31 g, whereas at the highest suction (31.9 MPa), the mass decreased from 11.06 g to about 9.29 g, corresponding to greater water loss and reduced equilibrium water content. This trend reflects the fundamental thermodynamic principle that higher suction levels correspond to lower relative humidity and water potential, thereby enhancing vapour-phase diffusion and capillary drainage from the pore network. The consistent stabilization across all suctions confirms that equilibrium was achieved within approximately two weeks and satisfies the steady-state criterion (|Δm|/m < 0.1%), demonstrating the effectiveness of PP in imposing and maintaining stable suction conditions. The data also suggests that the PP creates a controlled and diffusion-dominated moisture exchange environment, allowing for accurate and repeatable suction regulation across a wide range of potentials. In the tests, equilibrium for each suction step was typically achieved within 24–48 h, although higher suction levels occasionally required up to 72 h to satisfy the mass-change criterion, which is consistent with previous SWRC studies where equilibrium was generally attained within 24–48 h [

46].

During equilibration, the PP hydrogel exchanges water with the soil until a common suction is reached, and this process is accompanied by some volumetric strain of the polymer. In the present tests, the net amount of water transferred from the compacted kaolin specimen to the PP layer is small compared with the total water stored in the swollen polymer, so the additional volume change of PP during soil equilibration is limited. Visual inspection during and after testing confirmed that the PP layer remained in full contact with the filter paper and the cell walls, and no debonding or gap formation was observed. From a suction-control standpoint, the boundary condition imposed on the soil is governed by the water activity of the PP, which is described by the independently calibrated PP water retention curve. This calibration implicitly incorporates the effect of volumetric strain on the PP suction, so that the volume change of the hydrogel during testing does not compromise the imposed suction, provided that the cell is dimensioned to accommodate the small additional swelling.

3.3. Water Retention Curves (WRCs) of Kaolin

The water retention curve (WRC) of compacted kaolin obtained using the PP method is presented in

Figure 11, alongside WP4C results. The PP method successfully captured the entire desaturation process, spanning low suctions (<10 MPa) through the residual water content regime (>200 MPa). Unlike WP4C, which displayed increased scatter and instability at higher suctions, the PP-derived WRC exhibited a smooth, monotonic trend. This improvement is attributed to the larger specimen size used in PP tests, which mitigates localized heterogeneity effects and enhances representativeness. The reproducibility of the PP curve across replicate tests reinforces its utility as a reliable method for generating WRC data for compacted clays.

The practical importance of this result lies in the ability to provide continuous WRC data without the need to combine multiple methods, which is often the case in unsaturated soil mechanics (for example, stitching VET at low suctions with WP4C at high suctions). The PP method thus bridges these suctions, yielding a single consistent curve that simplifies constitutive modelling. Moreover, because the PP curve extended reliably into the high suction range, it captured the residual region of kaolin where storage capacity is minimal but hydraulic conductivity becomes highly sensitive to further drying. Capturing this transition is crucial for predicting long-term desiccation effects in clay liners.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overcoming Limitations of Conventional Osmotic Techniques

The PP method addresses several limitations inherent to PEG-based osmotic testing. The elimination of a semi-permeable membrane removes a major source of error and failure. Membrane clogging, bacterial degradation, and leakage have been reported as persistent issues in PEG systems, often leading to inconsistent results and extended equilibration times [

18,

28].

Additionally, PP’s temperature stability (

Figure 9) further distinguishes it from PEG. Many laboratories lack the infrastructure for precise temperature control, meaning PEG tests often require correction factors or repeated calibrations. The PP eliminates this complication by producing consistent suction–water content curves across normal laboratory temperatures. This reliability simplifies experimental procedures and reduces uncertainty, making PP more practical for routine use in geotechnical testing.

To place the proposed poly-potassium (PP) osmotic technique in context, it is useful to compare it with the conventional polyethylene glycol (PEG) membrane method. Both techniques rely on osmotic equilibrium to impose matric suction on the soil and therefore require independent calibration of the osmotic medium (concentration–suction for PEG solutions, and water content–suction for the PP hydrogel). However, the physical implementation is different. In the PEG method, an aqueous PEG solution is separated from the soil by a semi-permeable membrane, and practical issues such as membrane clogging, air diffusion, solution leakage and the need for circulation and tight temperature control are often reported. In the PP method used here, a cross-linked solid hydrogel layer is placed beneath the soil specimen and separated by filter paper, eliminating the need for a semi-permeable membrane and liquid circulation, and greatly simplifying handling, sealing and maintenance. The results for compacted kaolin show that the PP-based SWRC closely matches the independent WP4C measurements over the suction range tested, indicating that PP can provide an accurate and operationally simpler alternative to PEG for suction control. At the same time, it should be recognised that PEG has a long history of use across a wide variety of soils, whereas the present PP calibration is limited to one polymer and one soil; systematic comparison of PP and PEG for different soil types and suction ranges is therefore identified as an important direction for future work.

In this work, the number of imposed suction levels was intentionally limited in order to balance curve resolution with the very long equilibration times required at each step, especially at higher suctions. The selected suction steps were chosen to capture the main characteristics of the kaolin SWRC, including the initial slope, the air-entry region and the high-suction tail. While a larger number of data points would certainly provide a smoother and more detailed definition of the SWRC, the close agreement between the curves obtained with the PP method and those measured using the WP4C device indicates that the current resolution is sufficient for the comparative objectives of this study. Nevertheless, increasing the number of suction levels, particularly around the air-entry value, is identified as an important direction for future work.

From a practical standpoint, the PP osmotic technique used in this study should be regarded as a suction-control method for quasi-static laboratory testing rather than a tool for direct or real-time suction measurement. Equilibration between the soil and PP typically requires on the order of 24–48 h in our experiments, so rapid measurements within minutes or seconds are not feasible using this approach. For applications that demand time-sensitive or continuous suction monitoring, alternative techniques such as tensiometers or dew-point devices are therefore more appropriate. The main advantage of the PP method lies in its ability to impose stable, high-range suctions in a simple, membrane-free setup, which is well suited to SWRC determination and other long-term unsaturated soil tests where the relevant timescale is days rather than minutes.

4.2. Thermal Parameterisation of the PP-Controlled Water Retention Curve (20–30 °C)

Gravimetric water content

(%, dry mass basis) follows a log–linear form

with suction,

(in MPa). Independent fits at 20, 25(a), 25(b), and 30 °C yield:

Both the intercept and the magnitude decrease monotonically with , consistent with higher equilibrium vapour pressure (Kelvin/Clapeyron effect) and lower surface tension at elevated temperature, which reduces capillary/adsorbed retention at a fixed suction set-point. The duplicate 25 °C datasets overlap within parameter uncertainties, evidencing good reproducibility.

Using the 25 °C average as reference, the mean decrease from 20 to 30 °C is 42.7% at MPa, 52.2% at 10 MPa, and 77.6% at 30 MPa (computed from the fitted curves). Although the absolute slope becomes slightly less negative as increases, the relative sensitivity grows toward the dry end, where thin-film adsorption dominates and small changes in water activity cause large fractional changes in . For transparency, we report at MPa together with the 20 → 30 °C percentage change.

A compact linear-in-temperature model fitted to the four curves is

with

in °C and

in MPa. Coefficient uncertainties are

and

for

, and

and

for

. This relation reproduces the observed trends over 20–30 °C and enables interpolation/normalisation across temperature without re-fitting. The intended validity domain is the tested soil and branch under PP control, for

MPa and

°C; use outside this window should be treated as extrapolation.

4.3. Equilibration Kinetics Under PP-Controlled Suction

The equilibration behaviour was quantified from mass–time series at target suctions of 1.58, 3.58, 13.05, and 31.9 MPa, measured on days 0, 1, 4, 8, 11, and 15. For each series, the initial and final masses

and

define the total exchange

. The time to reach 95% of that exchange,

, was obtained by linear interpolation between the two observation days that bracket the 95% completion level. This procedure is strictly data-driven, avoids model extrapolation, and is robust to the day-level sampling used here. Across all suctions, the curves exhibit a two-stage form: a rapid first-day decline followed by a progressively slower approach to an asymptote.

Equilibration metrics (data-derived).

Table 6 summarises the quantities used in the analysis—initial/final masses, total exchange

, Day-1 drop, and

computed by Equation (8).

increases monotonically with suction (0.3501 → 1.7641 g), confirming that higher set-points impose stronger vapour-phase driving forces. Concomitantly, decreases from 7.19 d to 2.98 d, indicating a faster approach to practical steady state as the moisture-potential gradient increases. The Day-1 drops—0.2087, 0.4828, 0.9934 and 1.5176 g—constitute ≈ 59.6%, 40.6%, 60.6% and 86.0% of , respectively; thus, most adjustment occurs early, with a slow tail reflecting internal redistribution as gradients diminish. Minor end-stage non-monotonicity is within balance resolution and does not materially affect (e.g., at 1.58 MPa, day 8 → 15 differs by ≈0.006 g ≈ 1.8% of ; at 31.9 MPa, day 8 → 15 differs by ≈0.0009 g ≈ 0.05% of ).

To characterise the two-regime behaviour directly from observations, an early-time residual after one day is cast as a dimensionless quantity

, which in turn defines an apparent first-day rate constant

. A naive first-order prediction for the 95% time then follows, and comparison with the observed

yields a deceleration factor

that quantifies the late-time slowdown.

where

is the dimensionless residual mass fraction at

day, i.e., the portion of the total mass change that remains after the first day. Hence

, with

indicating no change by day 1 and

indicating the final mass has been reached by day 1. Equivalently,

Applied to the present series, spans 0.52–1.97 d−1 and increases with suction, consistent with stronger moisture-potential gradients; lies between 1.01 and 2.18, indicating that late-time redistribution can extend practical equilibration by up to roughly a factor of two beyond what the day-1 rate alone would predict. These indicators support clear procedures for the PP method over 1.6–32 MPa: (i) allocate ≈3–7 days to reach 95% equilibration (longer at the low end); (ii) acquire denser weighings during the first 24–48 h to resolve the rapid transient; and (iii) terminate when the absolute mass change over a 48–72 h interval is 1% of . All values, equations, and recommendations above are computed solely from the present mass–time tables.

4.4. Hysteresis and Scanning-Path Effects (Wetting vs. Drying)

The four-point curves for 1st/2nd wetting and 1st/2nd drying allow quantification of the retention hysteresis and its persistence after a full cycle. At approximately matched suctions, the drying branch sits above the wetting branch, as expected for kaolin due to ink-bottle effects and contact-angle asymmetry. We define a pointwise hysteresis gap

and a loop-area index over a suction band

,

which removes units and permits comparison across materials.

Using linear interpolation on the first-cycle datasets,

at three common suctions are presented in

Table 7.

In

Figure 12, the shaded region between first-cycle wetting (squares) and drying (circles) water-retention curves for kaolin denotes the hysteresis loop area

on a

axis. Over

–

MPa, the loop-area ratio is

, consistent with pointwise gaps

of 16–30% reported in

Table 7.

The mean relative gap across 3–56 MPa is ≈23%. The corresponding loop-area index over the same band is , i.e., the hysteresis area is ~17% of the drying-branch area on a abscissa. This compact metric is reproducible from sparse points and is convenient for benchmarking materials or test configurations.

On the second cycle, the hysteresis is still clear at matched suctions: at ~9.46 MPa, (≈24% of wetting ); at ~32.7 MPa, (≈20%). Within the resolution of the present data, there is no strong fading-memory effect; the gap magnitude remains in the ~20–25% range, suggesting that microstructural changes induced by the first loop are minor for this kaolin under the tested stress path.

- (i)

For modelling, a single main drying curve will overpredict on wetting by ~20–30% in the 3–33 MPa range; including a hysteresis rule (e.g., scanning-curve interpolation with a pore-bundle constraint) is warranted.

- (ii)

For device cross-checks (PP vs. WP4C) performed on different paths, path alignment matters: comparisons should be made on the same branch (drying-on-drying or wetting-on-wetting) or corrected using

- (iii)

Practically, if only one branch can be measured, reporting alongside the branch used provides a one-number warning about expected path bias in applications.

4.5. Implications for Liner Design

The improved accuracy, reproducibility, and efficiency of the PP osmotic method have clear implications for landfill engineering. Continuous WRC data allow more precise modelling of unsaturated behaviour, particularly in predicting desiccation cracking and moisture redistribution in compacted clay liners (CCLs). Faster equilibration times improve turnaround for design testing, accelerating project schedules. Additionally, the robustness of PP in both thermal stability and concentration tunability ensures that test results are less prone to error, improving the reliability of liner assessments.

For GCLs, which rely heavily on bentonite hydration, PP provides a more realistic platform for exploring the interaction between chemical salinity and suction behaviour. Since PP eliminates membrane artefacts, it can simulate field-scale osmotic processes more faithfully. Overall, PP offers a membrane-free, thermally stable, and reproducible method for generating high-quality unsaturated soil property datasets, representing a step change in the laboratory characterization of barrier materials.

It should be emphasised that the present validation of the PP osmotic technique is limited to a compacted low-plasticity kaolin. The method itself is generic, because the imposed suction is governed by the independently calibrated PP water retention curve and is, in principle, independent of the soil type. However, materials with higher activity, such as expansive smectitic clays, are likely to exhibit larger volume changes, lower hydraulic conductivity and more pronounced hysteresis, which would mainly influence the equilibration time and the detailed shape of the SWRC obtained with the PP method. In addition, soils with high ionic strength pore water or strong organic content may alter the hydrogel response and would require specific PP calibration. Systematic application of the PP technique to highly active clays and a broader range of natural soils is therefore identified as an important direction for future research.

4.6. Limitations and Scope of Applicability

While this study offers substantive contributions and methodological innovations, it also carries limitations that should be acknowledged and that suggest clear directions for future research. The present validation is restricted to low-activity kaolin, which exhibits relatively modest volume change and microstructural rearrangement over the investigated suction range. For highly active clays (for example, Na-bentonite or natural expansive clays with large specific surface area and strong diffuse double layers), the coupling between imposed osmotic suction, fabric evolution and hydraulic conductivity is likely to be stronger. Swelling and shrinkage during equilibration may lengthen the time required to reach steady state and could locally alter the boundary condition at the filter-paper interface. Although the PP solution does not come into direct contact with the soil in the proposed configuration, further work is needed to confirm that cation release and changes in pore-water chemistry do not significantly modify the PP water-activity–suction relationship. Systematic testing on expensive and highly plastic clays is therefore an important next step before extending the method to more active materials.

- -

All temperature conclusions are for 20–30 °C and compacted kaolin; extension outside this scope or to chemically active clays (for example, Na-bentonite) requires validation because polymer–water activity and soil adsorption energetics may differ.

- -

Although the approach avoids conventional semi-permeable membranes, a Grade-42 filter paper was used as a physical separator. Its moisture impedance and any sorption/ion-exchange with PP were not independently quantified and could bias early-time kinetics or very-dry end points. Future work could measure the separator’s standalone resistance and verify that no polymer fragments cross the interface under high gradients.

- -

Validation against WP4C used a small number of paired points; the driest pair dominated the regression leverage. Additional matched points above ≈10–12 MPa would better define any scale bias in the ultra-dry tail.

- -

Kinetic parameters here are “apparent” because day-level sampling forces a coarse estimate of the fast stage; sub-hourly weighings in the first 6–12 h are recommended if one wishes to identify true multi-exponential behavior or to invert a rigorous diffusion model.

- -

The osmotic activity of PP may be altered by cations released from pore water; no chemical assays of the PP phase were performed before/after tests. This is unlikely in kaolin at 25 °C, but should be checked for saline or reactive soils.

5. Conclusions

This work demonstrates that a potassium-neutralised poly (acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) hydrogel (PP) can reliably impose and maintain high suction for determining the water-retention behaviour of compacted kaolin without the use of a conventional semi-permeable membrane. The PP calibration curve aligns closely with WP4C measurements (R2 ≈ 0.985; RMSE ≈ 0.08 MPa), and the imposed suction remains stable under moderate laboratory temperature variation (20–30 °C) with only small, predictable shifts in the log-linear W–ln s relation. Time-series measurements reveal fast early-time exchange followed by a slow approach to equilibrium; practical design metrics (first-day drop, t95, and a deceleration factor quantifying late-time slowdown) provide clear guidance for test planning. The method yields smooth, single-method WRCs spanning from low to very high suctions, enabling robust curve fitting and credible air-entry/residual characterisation, while measured wetting–drying hysteresis is moderate and quantifiable (~20–25% gap at matched points).

Practically, the approach removes common PEG-method failure modes (membrane degradation, polymer intrusion, microbial growth) and reduces the burden of strict thermal control, improving repeatability and throughput for routine geotechnical characterisation. For laboratory practice, denser weighing in the first 24–48 h is recommended to resolve the rapid transient, with termination when |Δm|/m over 48–72 h falls below 0.1%. Scope and limitations are tied to the tested configuration (kaolin, 20–30 °C, thin disc geometry, filter-paper separator); extension to other soils, chemistries, geometries, or wider temperatures should be supported by dedicated recalibration and additional matched PP–WP4C points in the ultra-dry range. Overall, PP represents a practical and thermally robust alternative osmotic medium that can simplify and strengthen high-suction THM testing in unsaturated soil mechanics.

Accordingly, the results should be viewed as a proof-of-concept using compacted kaolin, and dedicated studies on expansive and other highly active clays are required before the poly potassium osmotic technique is generalised to all soils.