Intraocular Coinfection by Toxoplasma gondii and EBV Possibly Transmitted Through Unpasteurized Goat Milk in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

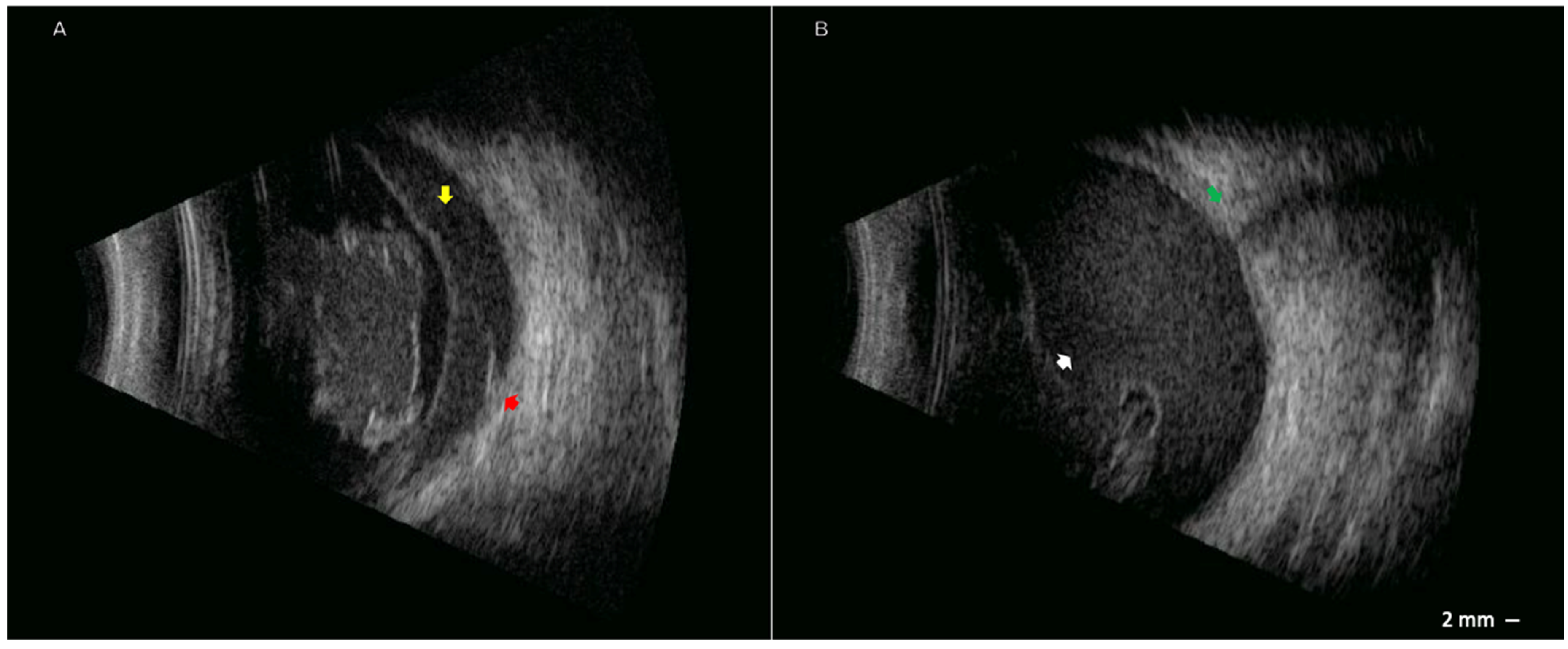

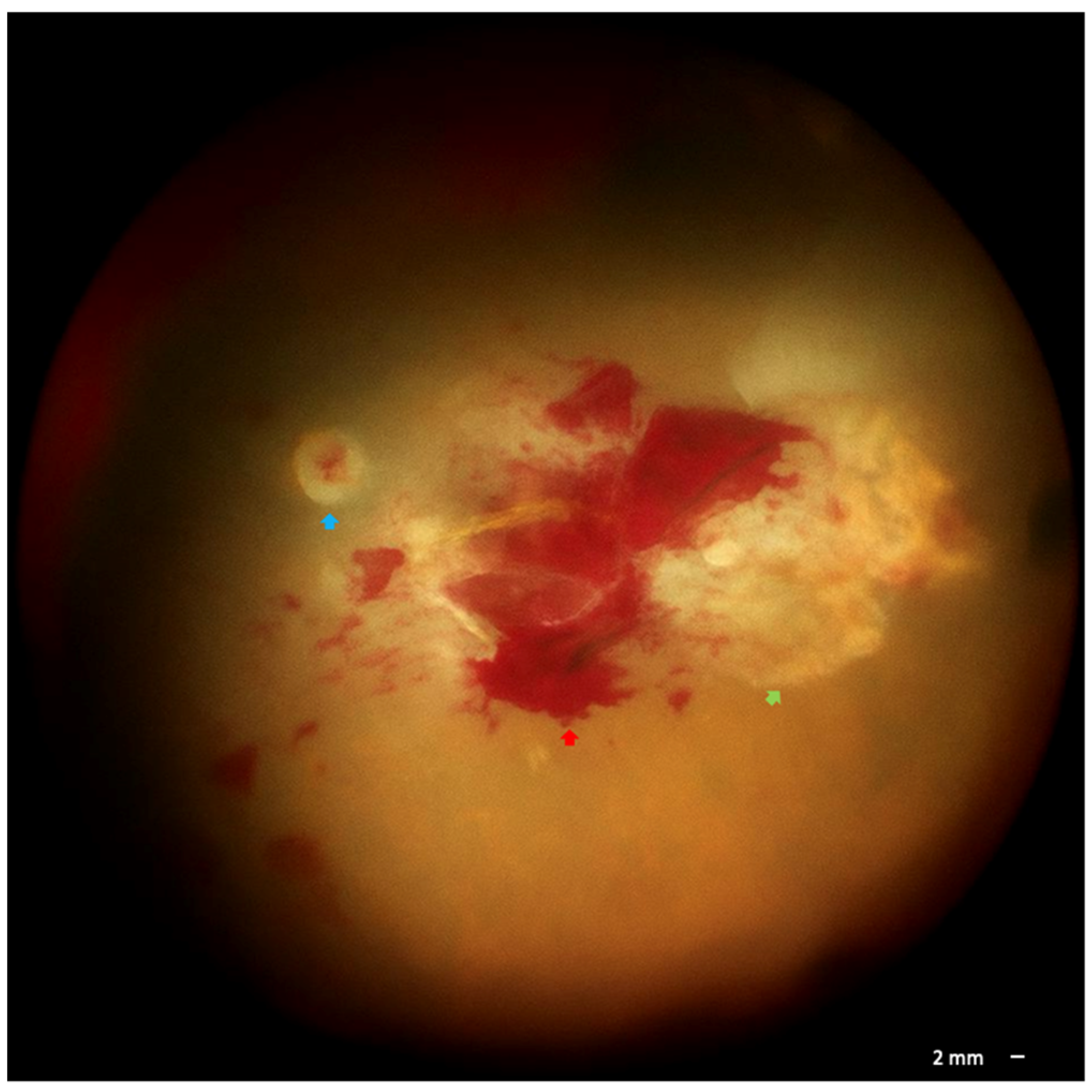

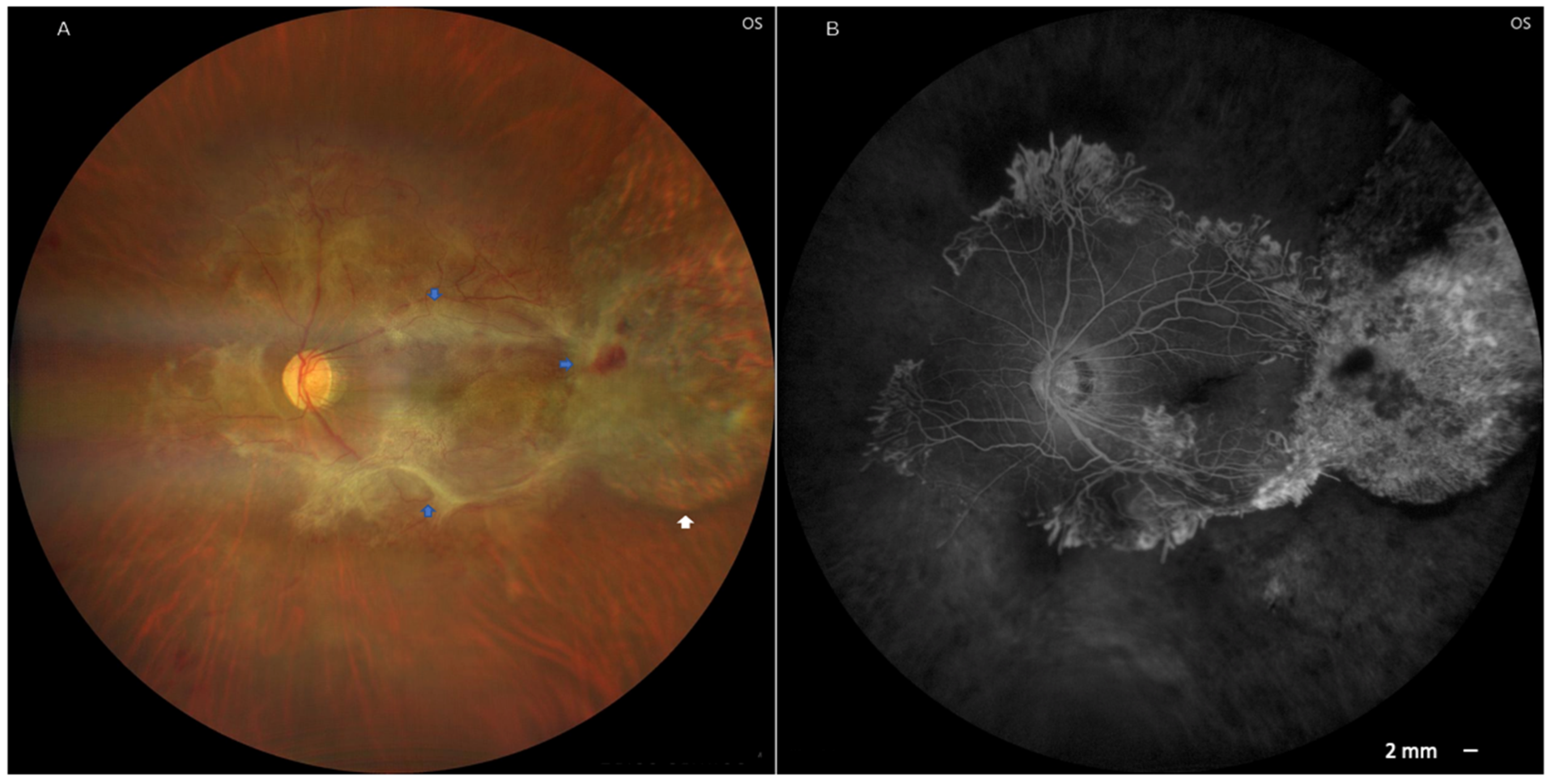

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, J.R.; Ashander, L.M.; Arruda, S.L.; Cordeiro, C.A.; Lie, S.; Rochet, E.; Belfort, R.; Furtado, J.M. Pathogenesis of Ocular Toxoplasmosis. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2021, 81, 100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, J.M.; Winthrop, K.L.; Butler, N.J.; Smith, J.R. Ocular Toxoplasmosis I: Parasitology, Epidemiology and Public Health. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2013, 41, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.L.; Dargelas, V.; Roberts, J.; Press, C.; Remington, J.S.; Montoya, J.G. Risk Factors for Toxoplasma gondii Infection in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belluco, S.; Simonato, G.; Mancin, M.; Pietrobelli, M.; Ricci, A. Toxoplasma gondii Infection and Food Consumption: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Controlled Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 3085–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto-Ferreira, F.; Caldart, E.T.; Pasquali, A.K.S.; Mitsuka-Breganó, R.; Freire, R.L.; Navarro, I.T. Patterns of Transmission and Sources of Infection in Outbreaks of Human Toxoplasmosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 2177–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koethe, M.; Schade, C.; Fehlhaber, K.; Ludewig, M. Survival of Toxoplasma gondii Tachyzoites in Simulated Gastric Fluid and Cow’s Milk. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 233, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.J.G.; Kim, P.C.P.; Moraes, É.P.B.X.; Sá, S.G.; Albuquerque, P.P.F.; Silva, J.G.; Alves, B.H.L.S.; Mota, R.A. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii in the Milk of Naturally Infected Goats in the Northeast of Brazil. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2015, 62, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasundaram, M.B. Outbreak of Acquired Ocular Toxoplasmosis Involving 248 Patients. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2010, 128, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de-la-Torre, A.; Valdés-Camacho, J.; De Mesa, C.L.; Uauy-Nazal, A.; Zuluaga, J.D.; Ramírez-Páez, L.M.; Durán, F.; Torres-Morales, E.; Triviño, J.; Murillo, M.; et al. Coinfections and Differential Diagnosis in Immunocompetent Patients with Uveitis of Infectious Origin. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaal, S.; Kagan, A.; Wang, Y.; Chan, C.-C.; Kaplan, H.J. Acute Retinal Necrosis Associated with Epstein-Barr Virus: Immunohistopathologic Confirmation. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014, 132, 881–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongkosuwito, J.V.; Van Der Lelij, A.; Bruinenberg, M.; Doorn, M.W.-v.; Feron, E.J.C.; Hoyng, C.B.; De Keizer, R.J.W.; Klok, A.-M.; Kijlstra, A. Increased Presence of Epstein-Barr Virus DNA in Ocular Fluid Samples from HIV Negative Immunocompromised Patients with Uveitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 82, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, S.; Vieira, B.R.; Garcia, D.M.; Araújo, M.; Simões, M.; Moreto, R.; Rodrigues, M.W.; Belfort, R.; Smith, J.R.; Furtado, J.M. Clinical Manifestations and Visual Outcomes Associated with Ocular Toxoplasmosis in a Brazilian Population. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Zaafrane, N.; Harrath, M.; Sellem, I.; Mahmoudi, M.; Soudani, S.; Atig, A.; Ghorbel, M.; Ben Abdesslem, N. Vitreous Hemorrhage Complicating Toxoplasmic Retinochoroiditis in a Child: Case Report. JFO Open Ophthalmol. 2025, 10, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynon, M.W.; Boldrey, E.E.; Strahlman, E.R.; Fine, S.L. Retinal Neovascularization and Ocular Toxoplasmosis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1984, 98, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalogeropoulos, D.; Sakkas, H.; Mohammed, B.; Vartholomatos, G.; Malamos, K.; Sreekantam, S.; Kanavaros, P.; Kalogeropoulos, C. Ocular Toxoplasmosis: A Review of the Current Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022, 42, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogeswaran, K.; Furtado, J.M.; Bodaghi, B.; Matthews, J.M.; International Ocular Toxoplasmosis Study Group; Smith, J.R. Current Practice in the Management of Ocular Toxoplasmosis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 107, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, S.; Caroselli, C.; Menchini, M.; Gabbriellini, G.; Falcone, M.; Bruschi, F. Ocular Toxoplasmosis, an Overview Focusing on Clinical Aspects. Acta Trop. 2022, 225, 106180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, P.; Turunen, H.J.; Paasivuo, R.T.; Leinikki, P.O. Immunoblot Analysis of Toxoplasma Gondii Antigens by Human Immunoglobulins G, M, and A Antibodies at Different Stages of Infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1984, 20, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughattas, S. Toxoplasma Infection and Milk Consumption: Meta-Analysis of Assumptions and Evidences. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2924–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P.; Verma, S.K.; Ferreira, L.R.; Oliveira, S.; Cassinelli, A.B.; Ying, Y.; Kwok, O.C.H.; Tuo, W.; Chiesa, O.A.; Jones, J.L. Detection and Survival of Toxoplasma gondii in Milk and Cheese from Experimentally Infected Goats. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 1747–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-M.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.-Y.; Li, C.-H.; Jiang, Y.-H.; Sun, W.-W. First Detection of Anti-Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies in Domestic Goat’s Serum and Milk during Lactation in China. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 161, 105268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazzonis, A.L.; Zanzani, S.A.; Stradiotto, K.; Olivieri, E.; Villa, L.; Manfredi, M.T. Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies in Bulk Tank Milk Samples of Caprine Dairy Herds. J. Parasitol. 2018, 104, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silpa-archa, S.; Sriyuttagrai, W.; Foster, C.S. Treatment for Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Uveitis Confirmed by Polymerase Chain Reaction: Efficacy of Anti-Viral Agents and a Literature Review. J. Clin. Virol. 2022, 147, 105079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarate-Pinzon, L.; Peña-Pulgar, L.F.; Cifuentes-González, C.; Rojas-Carabali, W.; Salgar, M.J.; de-la-Torre, A. Panuveitis by Coinfection with Toxoplasma gondii and Epstein Barr Virus. Should We Use Antiviral Therapy?—A Case Report. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2024, 32, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Salgado, G.; Cardozo-Pérez, C.; Cifuentes-González, C.; Durán-Merino, C.; de-la-Torre, A. Coinfection Suspicion Is Imperative in Immunosuppressed Patients with Suspected Infectious Uveitis and Inadequate Treatment Response: A Case Report. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2024, 32, 2548–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, S.; Sugita, S.; Sugamoto, Y.; Shimizu, N.; Morio, T.; Mochizuki, M. Quantitative PCR for the Detection of Genomic DNA of Epstein-Barr Virus in Ocular Fluids of Patients with Uveitis. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 52, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerbach, A.; Gruhn, B.; Egerer, R.; Reischl, U.; Zintl, F.; Wutzler, P. Semiquantitative PCR Analysis of Epstein-Barr Virus DNA in Clinical Samples of Patients with EBV-associated Diseases. J. Med. Virol. 2001, 65, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.J.; Bein, G.; Bitsch, A.; Kirchner, H. Detection and Quantification of Latently Infected B Lymphocytes in Epstein-Barr Virus-Seropositive, Healthy Individuals by Polymerase Chain Reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30, 2826–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurmann, S.; Fricke, L.; Wagner, H.-J.; Schlenke, P.; Hennig, H.; Steinhoff, J.; Jabs, W.J. Molecular Parameters for Precise Diagnosis of Asymptomatic Epstein-Barr Virus Reactivation in Healthy Carriers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 5419–5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Yang, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhu, M.; Ai, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, B.; Shao, L.; Zhang, W. Clinical Application of Epstein-Barr Virus DNA Loads in Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Diseases: A Cohort Study. J. Infect. 2021, 82, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cardona-López, J.; Rodríguez, F.J.; Igua, R.; de-la-Torre, A. Intraocular Coinfection by Toxoplasma gondii and EBV Possibly Transmitted Through Unpasteurized Goat Milk in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Case Report. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1222. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121222

Cardona-López J, Rodríguez FJ, Igua R, de-la-Torre A. Intraocular Coinfection by Toxoplasma gondii and EBV Possibly Transmitted Through Unpasteurized Goat Milk in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Case Report. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1222. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121222

Chicago/Turabian StyleCardona-López, Juanita, Francisco J. Rodríguez, Ricardo Igua, and Alejandra de-la-Torre. 2025. "Intraocular Coinfection by Toxoplasma gondii and EBV Possibly Transmitted Through Unpasteurized Goat Milk in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Case Report" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1222. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121222

APA StyleCardona-López, J., Rodríguez, F. J., Igua, R., & de-la-Torre, A. (2025). Intraocular Coinfection by Toxoplasma gondii and EBV Possibly Transmitted Through Unpasteurized Goat Milk in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Case Report. Pathogens, 14(12), 1222. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121222