1. Introduction

The rheological evolution of cementitious systems at rest, commonly referred to as structural build-up, has become a central topic in the development of new-generation concretes [

1,

2,

3]. Structural build-up describes the time-dependent increase in static yield stress resulting from the gradual formation of particle networks and early hydration products [

4,

5]. Two distinct mechanisms contribute to this evolution. The first corresponds to reversible physical flocculation, driven by van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions, which can be largely undone by applying shear [

6,

7,

8,

9]. The second is an irreversible chemical contribution, arising from early hydrate formation, primarily calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) and ettringite, that create permanent particle–hydrate bridges [

10,

11,

12]. The quantification of this duality between reversible flocculation and irreversible chemical contributions is essential for predicting slump loss, formwork pressure, pumping resistance, or the buildability of 3D-printed materials [

13,

14,

15].

Several approaches have been developed to assess the structural build-up of cementitious systems, including hysteresis loop measurements, oscillatory rheology, and other time-dependent rheometric methods [

3,

6,

16]. Among these, the monitoring of static yield stress with rest time has emerged as a robust indicator, allowing the separation of reversible and irreversible components. Recent studies have further demonstrated that structural build-up arises from the combined effect of colloidal forces, which dominate in the early minutes, and hydrate nucleation, which progressively contributes to rigidification as hydration advances [

3,

6,

15,

17,

18]. The relative contribution of these mechanisms is highly sensitive to mix design parameters, including solid volume fraction, water-to-cement (w/c) ratio, temperature, and the presence of chemical or mineral admixtures.

While this reversible/irreversible distinction is well recognized [

9,

19,

20,

21], several key questions remain insufficiently addressed, particularly when SCMs are incorporated. SCMs alter both the physical (morphology, surface texture, packing density) and chemical (reactivity, ion release) characteristics of the binder system [

22,

23]. The combined impact of SCM type on total vs. irreversible structural build-up remains poorly quantified, especially under varying thermal conditions. This limits the ability to understand whether SCMs modify structuration primarily through colloidal effects or through changes in hydration-driven bonding.

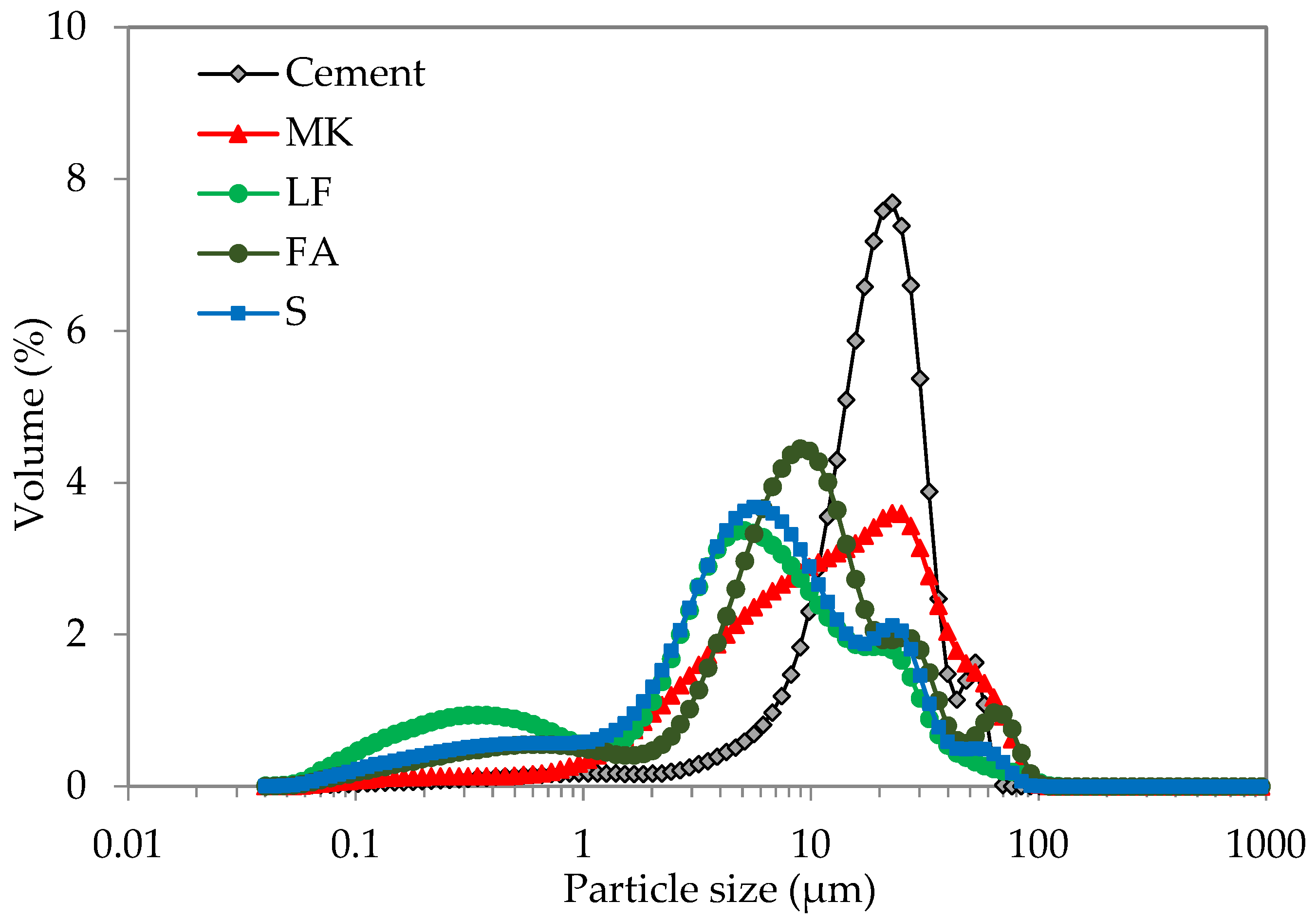

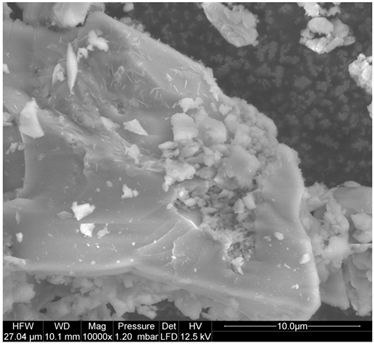

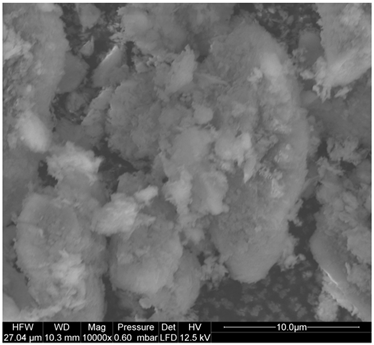

The rheological response of blended cement paste is further complicated by the intrinsic particle characteristics of SCMs [

12,

22,

23]. Fineness, specific surface area and morphology strongly influence interparticle spacing, water film thickness, and flocculation tendencies [

24]. Smooth and spherical particles, such as fly ash or slag, tend to reduce interparticle friction and enhance flowability, whereas angular or lamellar particles, such as metakaolin or silica fume, increase water demand and promote flocculation [

24]. While these effects on initial rheology are well documented, their consequences for structural kinetics, particularly the irreversible fraction, remain insufficiently explored.

Beyond these physical effects, the chemical and physicochemical contributions of SCMs further complicate the rheological response [

22,

23]. Studies by Ahari et al. [

25] and Yuan et al. [

12] revealed that SCMs influence both the magnitude and reversibility of structuration by modifying thixotropy, breakdown energy, and zeta potential. Finer and more reactive SCMs (e.g., metakaolin, silica fume) accelerate structuration and enhance thixotropy, whereas coarser or inert materials (e.g., fly ash, slag) delay the process and promote workability retention. Importantly, Yuan et al. [

12] demonstrated that hydration rate does not always correlate with structural build-up, suggesting that early-age structuration is often dominated by colloidal interactions rather than by hydrate formation.

SCMs also differ in their chemical reactivity, which may be temperature dependent [

26]. Their contribution to hydrate nucleation and growth can therefore change significantly under cold or warm mixing conditions. Although temperature is known to accelerate cement hydration, its effect on the balance between reversible and irreversible structuration has been rarely quantified for SCM-blended systems. This knowledge gap is particularly relevant for low-clinkers, low-carbon binders, where reduced early reactivity may compromise build-up and early stability.

Finally, the growing demand for sustainable and low-clinker concretes strengthens the need to understand these mechanisms [

27,

28]. Reducing clinker content through SCMs mitigates environmental impact but also modifies the early-age rheological behavior that governs placement, finishing, and additive manufacturing processes [

29]. A better understanding of how SCMs alter the interplay between physical flocculation, particle packing, and early hydrate formation is thus essential for designing robust, low-carbon mixtures.

To address these gaps, the present study investigates the time-dependent structuration of cement pastes incorporating four common SCMs (fly ash, slag, limestone filler, and metakaolin) under three temperatures (5, 20, 30 °C). The static yield stress approach is employed to separate the total and irreversible contributions to structural build-up.

This work aims to answer the following research questions: (1) How do different SCMs modify the rate and magnitude of total vs. irreversible structural build-up? (2) To what extent are these effects governed by particle morphology, packing, and clinker dilution versus early-age hydration kinetics? (3) How does temperature influence the physical (reversible) and chemical (irreversible) components of structural build-up in plain and blended systems?

By integrating rheological and isothermal calorimetric measurements, this study provides new insights into the mechanisms governing early-age behavior in blended cement systems, knowledge that is crucial for optimizing their performance in self-compacting and 3D-printable concretes.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of SCMs on Flowability and Static Yield Stress

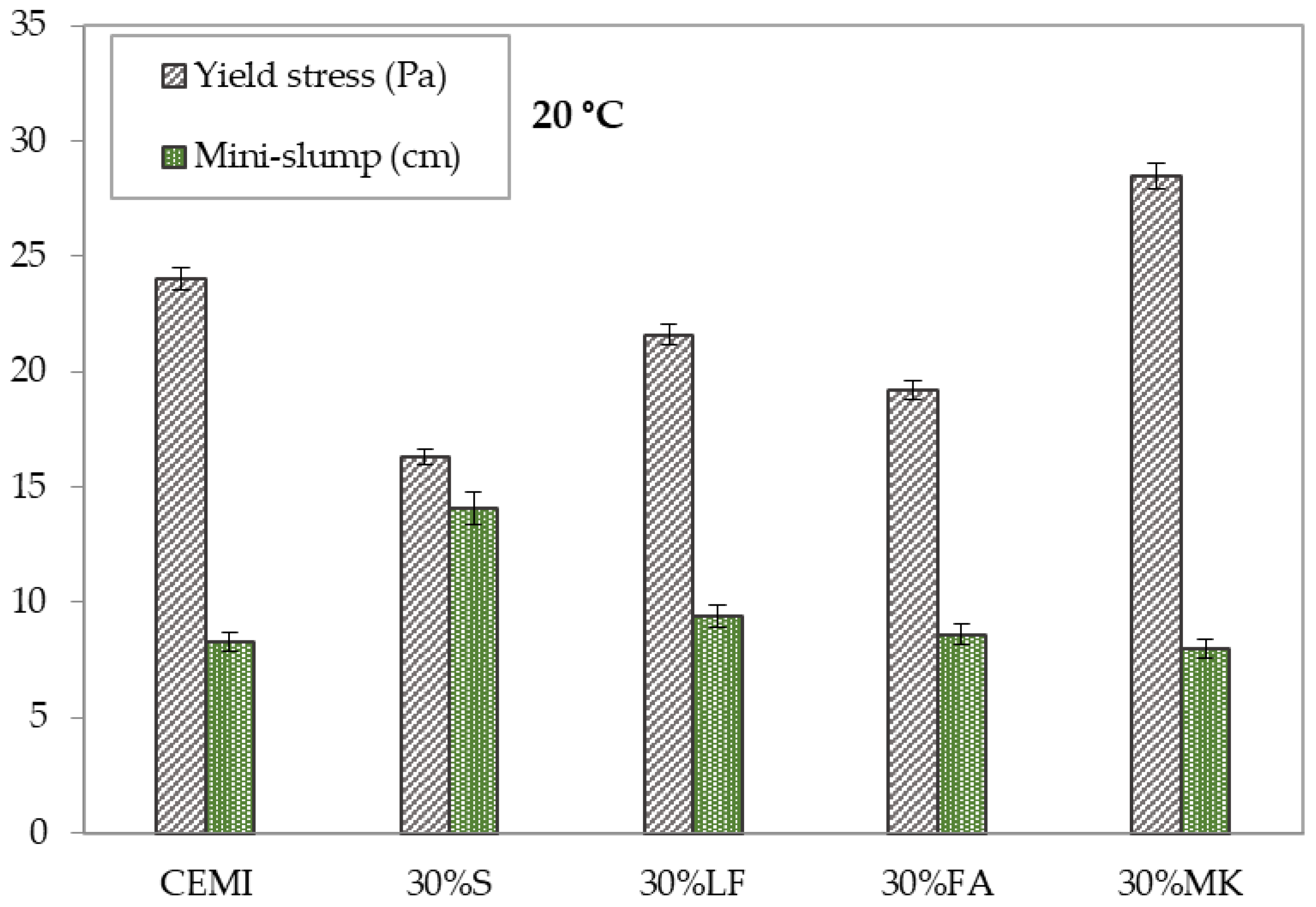

Figure 2 shows the influence of different SCMs on the initial yield stress and mini-slump flow of cement pastes at a constant w/b ratio of 0.45. The reference paste (CEM I) exhibited a yield stress of 24 Pa and a mini slump of 8.3 cm, indicating moderate consistency and flowability.

The addition of SCMs slightly influences rheological properties depending on their surface characteristics, morphology and reactivity [

22,

24,

34,

35,

36]. Slag produced the lowest yield stress (16 Pa, −33% relative to the reference) and the largest mini-slump (14 cm, +69%), indicating enhanced flowability. This behavior is consistent with its smooth, vitreous particle surface and moderate fineness, which reduces interparticle friction and improves packing density. This trend is consistent with the results of Ahari et al. [

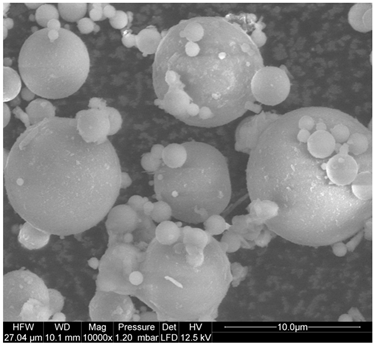

25] and Shanahan et al. [

24], who demonstrated that finely ground slag weakens flocculated structures and promotes dispersion at an early age.

Pastes containing FA and LF exhibited intermediate behavior, with yield stresses of 19–21.6 Pa (−10 to −20% vs. reference) and mini-slump diameters of 8.6–9.4 cm (+4 to +13%). Both SCMs slightly reduced inter-particle friction compared with cement. For FA, this effect is attributed to its spherical particle shape, which promotes rolling and improved packing [

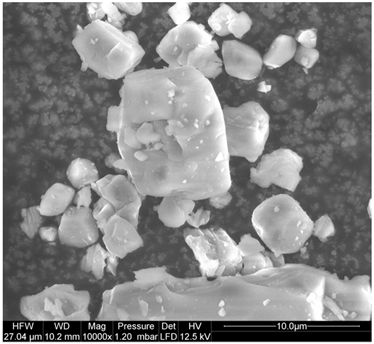

37], whereas LF particles, with smooth cubic shape (

Table 1), primarily act as fillers, increasing solid volume without significantly increasing water demand [

37].

In contrast, MK increased yield stress to 28.5 Pa (+19%) and reduced mini slump to 8 cm (−4%), due to its high surface area and lamellar morphology, which enhance water adsorption and promote flocculation through edge-to-face interactions [

37]. As noted by Shanahan et al. [

24], yield stress tends to correlate with BET surface area in binary OPC/SCM systems, a trend confirmed in the present data. Conversely, the reduced yield stress with slag, Limestone filler and fly ash is consistent with their lower surface area and smoother morphology. According to Ahari et al. [

25], the distinct rheological responses of SCMs arise from their intrinsic morphology and fineness: MK exhibits irregular and elongated particles promoting internal friction, while FA, S and LF possess smoother, spherical surfaces facilitating flow.

Overall, the results highlight that the rheological behavior of blended systems cannot be attributed solely to water demand or chemical reactivity. Instead, particle morphology, surface energy, and packing density control the formation of the particle network [

38,

39,

40]. The observed ranking of yield stress (MK > LF ≈ FA > S) agrees with the microstructural interpretations provided by Shanahan et al. [

24] and Yuan et al. [

12], confirming that SCMs affect the early rheological response primarily through physical and colloidal mechanisms, which set the initial conditions for subsequent structural build-up. In addition, according to Cai et al. [

34], the rheological response of SCM-containing mixtures reflects the combined effects of particle morphology, packing, and water film dynamics. In the present study, spherical fly ash reduces interparticle friction, whereas angular metakaolin promotes flocculation and higher yield stress, consistent with these principles.

3.2. Effect of SCMs on Cement Hydration Kinetics

Figure 3 presents the effect of the four SCMs on hydration kinetics, expressed through the induction period and setting time. The induction period corresponds to the dormant phase or the low-activity period before the acceleration of hydration, while the setting time reflects the overall rate of structure formation within the paste [

8].

For the reference cement paste (CEM I), the induction period was 2.7 h, and the final setting time was 4.6 h. All SCMs modified the early hydration behavior with effects that varied according to their intrinsic nature and reactivity. Slag, limestone filler, and metakaolin all reduced the induction period and the setting time, indicating an acceleration of early hydration processes. Slag and limestone filler mainly act through nucleation and seeding effects, providing additional surfaces for the precipitation of hydrates from the cement phase [

10,

12]. On the other hand, metakaolin exhibits partial pozzolanic activity even at an early age, which enhances the dissolution of aluminate phases and the formation of secondary hydrates [

41,

42].

However, the influence of SCMs on hydration kinetics cannot be interpreted as a direct indicator of their impact on early structuration. Indeed, several studies [

12,

25] have emphasized that the rate of heat release or setting time does not necessarily correlate with the degree of structural build-up. For example, slag-blended systems may show faster hydration but remain more fluid because their smooth, vitreous particles reduce interparticle friction. Conversely, MK increases yield stress without necessarily producing a higher heat release, due to strong interparticle flocculation that dominates the early stage of rest.

The present results confirm a decoupling between hydration kinetics and rheological evolution. At an identical w/b ratio, slag exhibited a shorter induction period but the lowest yield stress and the highest mini slump (

Section 3.1). This suggests that the dominant effect of slag at an early age is physical rather than chemical. Similarly, LF accelerates hydration through seeding but generates only moderate changes in yield stress, reflecting improved dispersion rather than strong network formation. In contrast, MK showed both accelerated hydration and higher yield stress, indicating that its fine lamellar structure enhances both nucleation and flocculation. Comparable observations were made by Johari et al. [

29], who reported that SCMs such as metakaolin and silica fume enhance early hydration and microstructural densification, whereas fly ash and slag delay mechanical strength development despite their nucleation potential. This underlines that early-age reactivity alone does not guarantee greater rigidity; the morphology and surface energy of particles play an equally important role. Consistently, El Bitouri [

26] demonstrated that the irreversible fraction of structural build-up remains low even when hydration is accelerated by temperature or reactive SCMs, confirming that early-age structuration is mainly governed by colloidal and flocculated interactions, while chemical bonding through hydrate formation becomes dominant only at later stages.

In summary, SCMs influence the hydration kinetics of cement pastes through distinct mechanisms, including nucleation, dilution, and pozzolanic reactions. However, these effects are not directly translated into higher rheological properties such as structural build-up, yield stress, or viscosity. The interplay between physical dispersion and chemical activation determines whether accelerated hydration results in greater or lower yield stress. Understanding this decoupling between hydration rate and structural build-up is crucial for optimizing the formulation of blended systems that maintain both flowability and early-age stability.

3.3. Effect of SCMs on Cement Paste Stability (Bleeding)

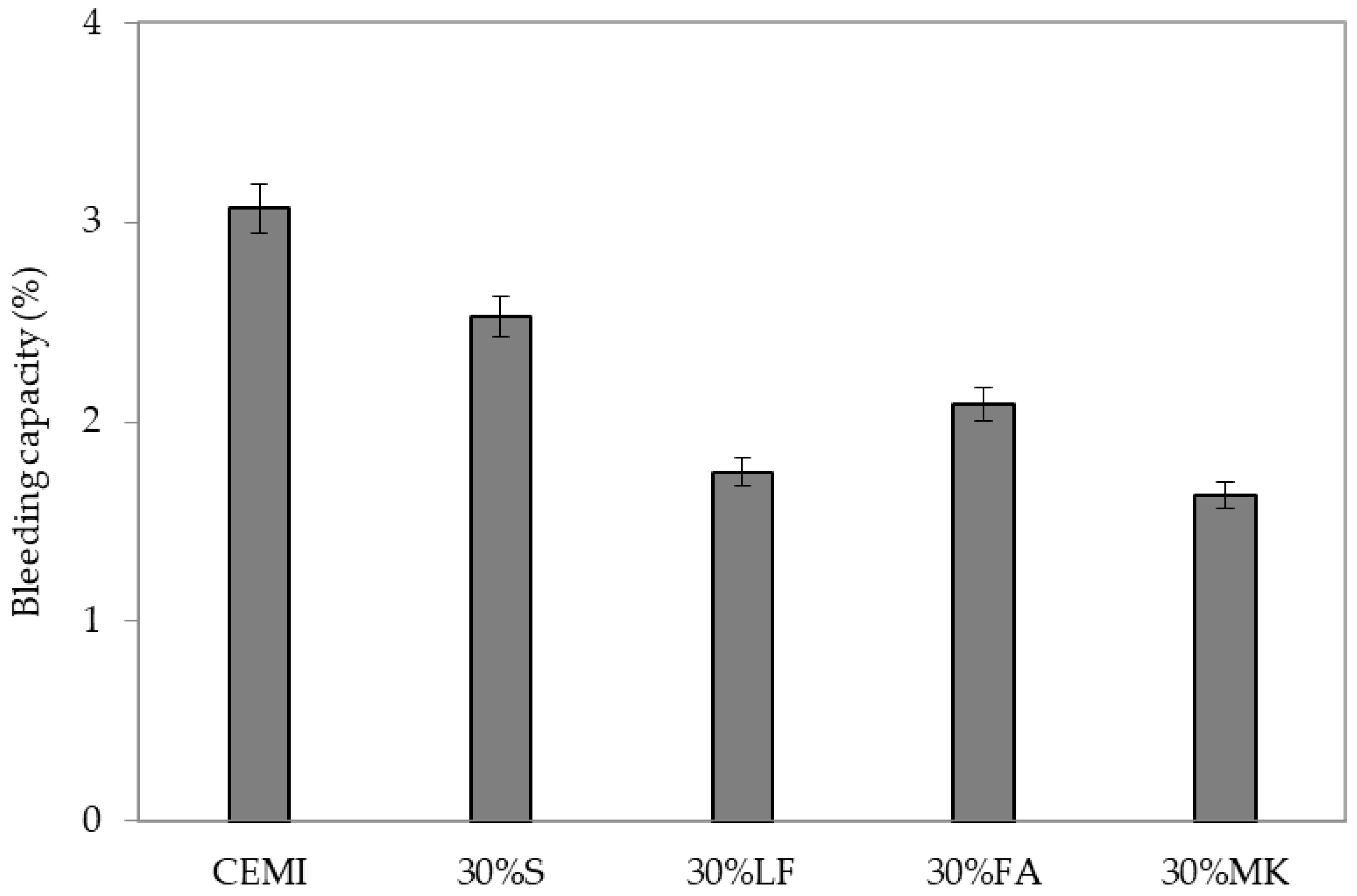

Figure 4 presents the bleeding capacity of cement pastes incorporating 30% of various SCMs. Bleeding reflects the tendency of free water to separate from the paste during early resting period, indicating both the development of the particle network and the ability of the solid skeleton to retain water [

43]. The reference paste (CEM I) exhibited the highest bleeding rate (3%), typical of mixtures with limited early network formation. The incorporation of SCMs systematically reduced bleeding, though to different extents depending on the type and properties of the mineral addition.

Among the SCMs, LF and MK exhibited the lowest bleeding capacities (1.8% and 1.6%), respectively. These materials refine the microstructure and improve water retention through two complementary mechanisms: (i) their fine particle size and high specific surface area enhance packing density, reducing capillary channels for water migration; and (ii) both LF and MK act as nucleation sites that promote early formation of hydrates, partially blocking percolation paths. These results are consistent with previous studies [

12,

44,

45], which reported that high-surface-area SCMs enhance stability by promoting finer particle packing and limiting segregation, even in systems with lower yield stress.

Slag also reduced bleeding compared with CEM I (2.5%), although its effect was less pronounced. Its fine, glassy particles improve packing density and reduce pore connectivity, leading to bleeding decrease despite enhanced flowability. Similarly, FA also produced a reduction in bleeding (2.1%). These trends align with the findings of Ahari et al. [

25], who observed that slag and fly ash enhance dynamic thixotropic recovery, thereby maintaining workability while improving static stability.

The comparative analysis of

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 reveals a consistent relationship between rheology, hydration, and stability. Mixtures with low yield stress and high flowability, such as slag- and fly ash-based systems, still achieved lower bleeding rates, indicating that physical packing and dispersion effects can stabilize the system even without high rigidity. Conversely, pastes with higher yield stress, such as those containing MK, showed negligible bleeding due to stronger flocculation and early hydrate bridging. This suggests that multiple mechanisms can lead to similar macroscopic stability: either through microstructural refinement (MK) or through optimized packing and reduced pore continuity (LF, S, FA). The observed link between stability and microstructure is consistent with the microstructural improvements reported by Johari et al. [

29], where SCMs such as MK and LF reduced porosity and improved homogeneity of the cement matrix. These results confirm that minimizing water migration during rest not only enhances fresh-state uniformity but also contributes to improved durability at later ages.

In summary, the incorporation of SCMs improves the early-age stability of cement pastes compared with cement, albeit via different mechanisms. Reactive and fine additions (MK) increase water retention through flocculation and nucleation effects, while less reactive additions (LF, S, FA) enhance stability mainly through packing and dilution effects. This duality highlights that reduced bleeding does not necessarily require higher yield stress. It can also arise from optimized particle arrangement and microstructural densification. Such stability enhancement is essential for the design of low-clinker, self-compacting, and 3D-printable binders that combine flowability with homogeneity.

3.4. Effect of w/b Ration on Structural Build-Up

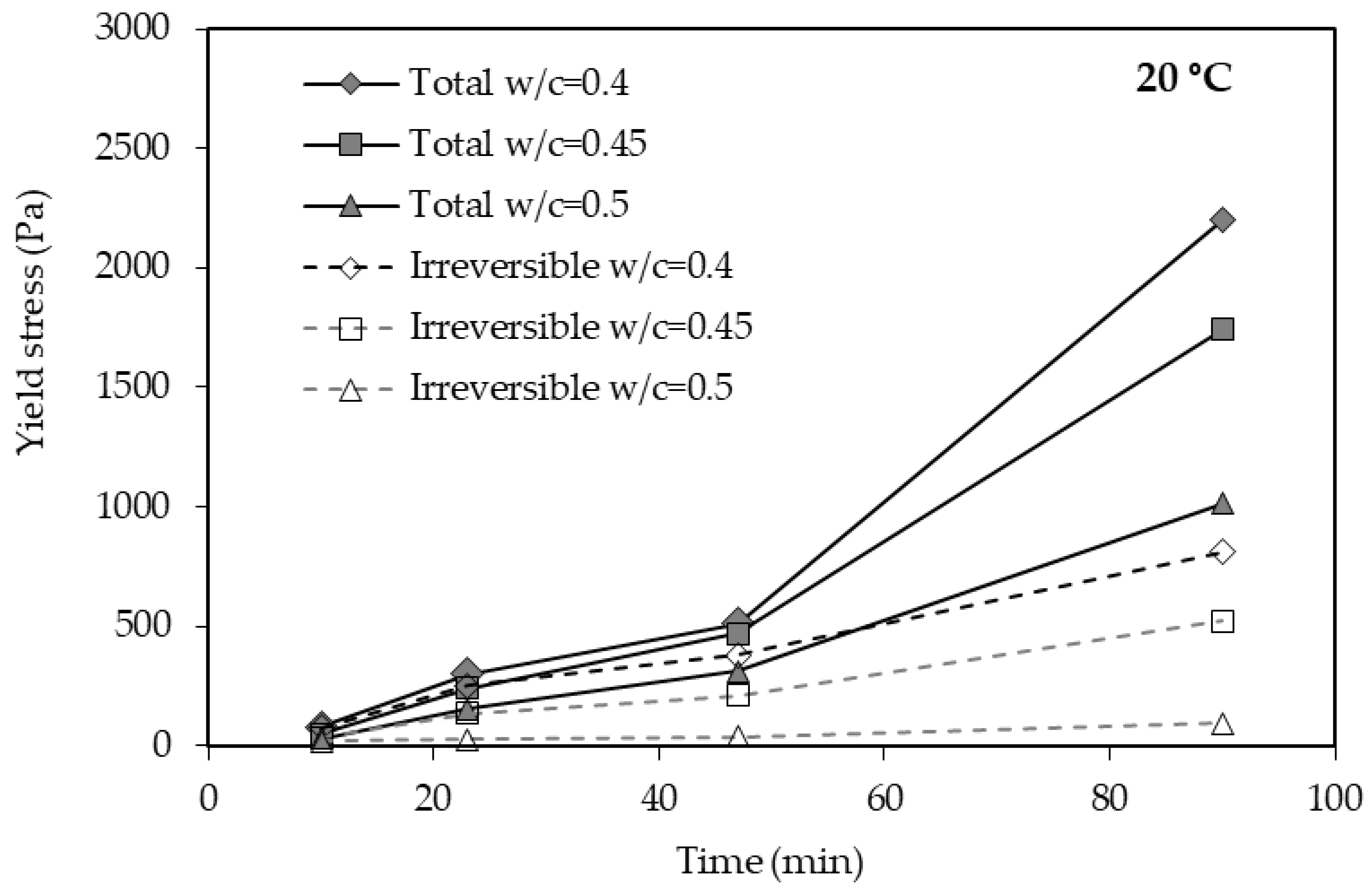

Figure 5 illustrates the evolution of the static yield stress of reference cement pastes prepared at three w/c ratios (0.40, 0.45, 0.50). Both the total and irreversible build-up components are reported as a function of rest time.

As expected, decreasing the water content led to a pronounced increase in yield stress and in the structuration rate. After 90 min of rest, the total yield stress reached 2200 Pa for w/c = 0.40, 1740 Pa for w/c = 0.45, and 1015 Pa for w/c = 0.50. This rise observed at lower w/c ratios indicates denser particle packing and stronger interparticle interactions that accelerate network formation. The higher solid fraction favors particle-particle contacts and shortens the distance required for hydrate bridges to form, resulting in faster structural build-up [

3].

The irreversible portion, representing the hydration-driven contribution that cannot be destroyed by re-shear, also increased markedly as the water content decreased. This trend highlights the direct coupling between water availability, hydration rate, and irreversible structuration. At low w/c, the limited amount of free water promotes rapid ion supersaturation in the pore solution, enhancing the nucleation and growth of early hydrates (mainly C–S–H and ettringite) [

36]. These precipitates form permanent particle–hydrate bridges, increasing the fraction of irreversible structural build-up. Conversely, at higher w/c = 0.50, the larger interparticle spacing and higher dilution delay percolation reduce both flocculation and hydrate connectivity, leading to a slower structural build-up and a lower irreversible fraction.

These observations are consistent with the findings of Yuan et al. [

12], who showed that the rate of structural build-up is strongly governed by solid volume fraction and interparticle distance rather than by hydration rate alone. Similarly, El Bitouri [

26] demonstrated that lower w/b ratios promote a higher irreversible fraction of build-up due to the closer proximity of reactive surfaces, which facilitates the formation of particle–hydrate bridges. In addition to physical packing, Ahari et al. [

25] highlighted that reduced water content enhances the structural build-up of cement pastes by strengthening the flocculated structure through increased colloidal attraction. The denser microstructure increases both the reversible and irreversible contributions to rigidity, thus promoting faster structural recovery after rest.

Therefore, these results confirm that the w/b ratio governs not only the kinetics but also the nature of structuration, by shifting the balance between physical flocculation and chemical bonding. At low w/c, van der Waals and electrostatic forces act over short distances, while fast ion accumulation favors the early precipitation of hydrates that permanently connect adjacent particles. At higher w/c, these forces are weaker and less frequent, and the structure remains mostly reversible, dominated by loose flocculation rather than solid bridging.

Overall, these results confirm that the w/c ratio is one of the most critical parameters governing the time-dependent structuration of cement pastes. Lower w/c ratios accelerate both physical flocculation and chemical bonding, leading to faster build-up and reduced formwork pressure. Conversely, higher w/c ratios improve flowability and delay structural development, providing longer workability windows but lower early rigidity. Achieving an optimal balance between these competing effects is therefore essential for designing mixtures adapted to self-compacting or 3D-printed concretes, where both flow retention and shape stability are required.

3.5. Effect of SCMs on Structural Build-Up

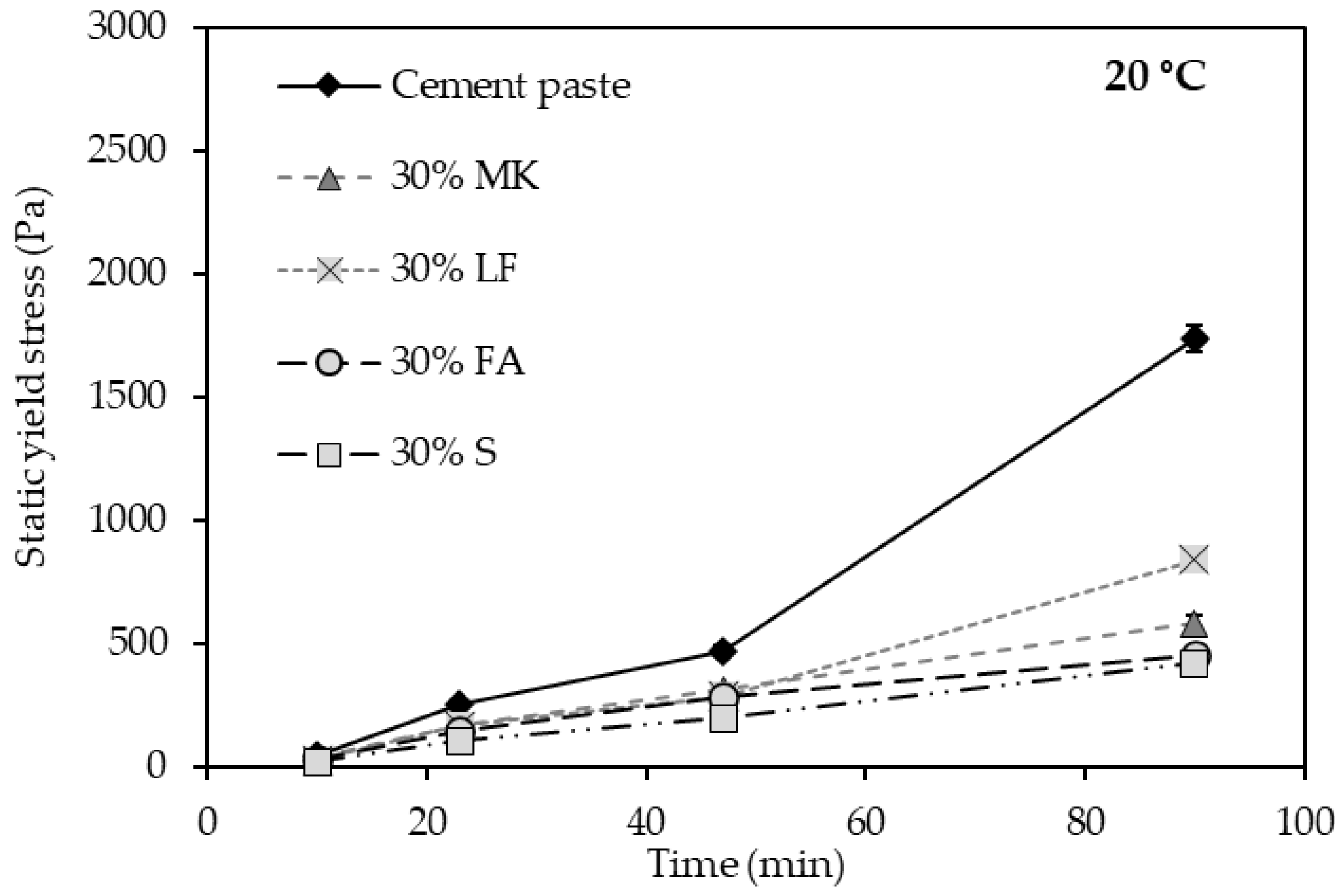

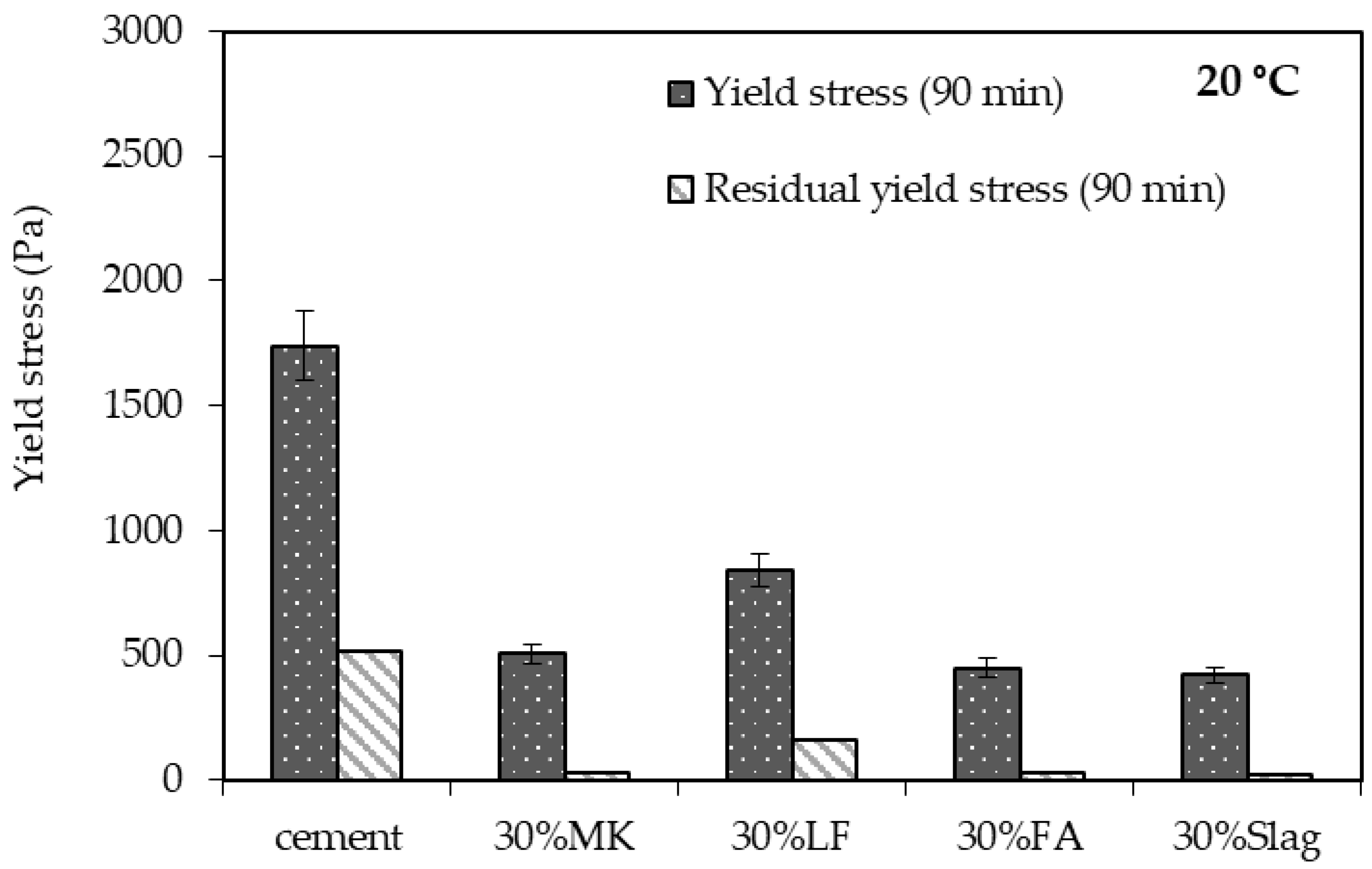

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 present the time-dependent evolution of static yield stress for cement pastes containing 30% of different SCMs, as well as the corresponding residual (irreversible) yield stress after 90 min of rest. These results provide complementary insights into how mineral additions influence both the kinetics and the nature of structuration.

The reference paste (CEM I) exhibited a rapid and continuous increase in yield stress, reaching 1740 Pa after 90 min, confirming its strong tendency for structural build-up at rest. In contrast, all SCM-blended systems displayed slower and weaker structural build-up, with final yield stress values ranging between 420 and 840 Pa (a reduction of 50% to 75%), depending on the SCM type. This reduction can be related to a combination of physical and chemical effects. First, the dilution of reactive clinker reduces the number of available nucleation and growth sites for hydrate formation, limiting the development of a percolated rigid network [

3]. Second, modifications in surface morphology and texture, such as smoother surfaces in slag and fly ash or strong water adsorption in metakaolin, decrease interparticle cohesion and delay hydrate bridging. Similar trends were reported by Yuan et al. [

12] and Ahari et al. [

25], who observed that replacing cement with SCMs decreases the rate of yield stress evolution, mainly due to dilution and reduced interparticle bonding.

Among the tested materials, LF and MK showed higher yield stress levels than S and FA, although all remained well below the reference cement paste. LF promotes partial seeding and microstructural densification, whereas MK contributes through high surface area and strong adsorption capacity. Nevertheless, both additions mainly strengthen reversible flocculation rather than generating irreversible bonds, which explains the limited residual yield stress. In contrast, the smoother surfaces and lower reactivity of S and FA further weaken flocculated structures, producing minimal irreversible build-up.

The residual yield stress results support this interpretation. The reference paste exhibited an irreversible component of about 25% of the total, while all SCM systems displayed values below 10%, with the lowest for FA and S. These findings confirm that the early structuration of blended systems is dominated by physical flocculation rather than by chemical bonding, as also emphasized by El Bitouri [

26]. Although certain SCMs (e.g., MK, LF) can accelerate hydration (

Section 3.2), the limited clinker content restricts hydrate connectivity and delays the formation of permanent particle–hydrate bridges.

In summary, the addition of SCMs systematically reduces the kinetics and intensity of structural build-up by diluting cement reactivity and moderating particle cohesion. While this behavior can be advantageous for preserving workability, it may lead to higher formwork pressure and lower early structural rigidity if not properly controlled. The design of low-clinker binders should therefore balance these opposing effects to ensure adequate build-up for stability and pressure reduction, without compromising flow performance during placement.

3.6. Effect of Temperature on Structural Build-Up of Ordinary and Blended Cement Pastes

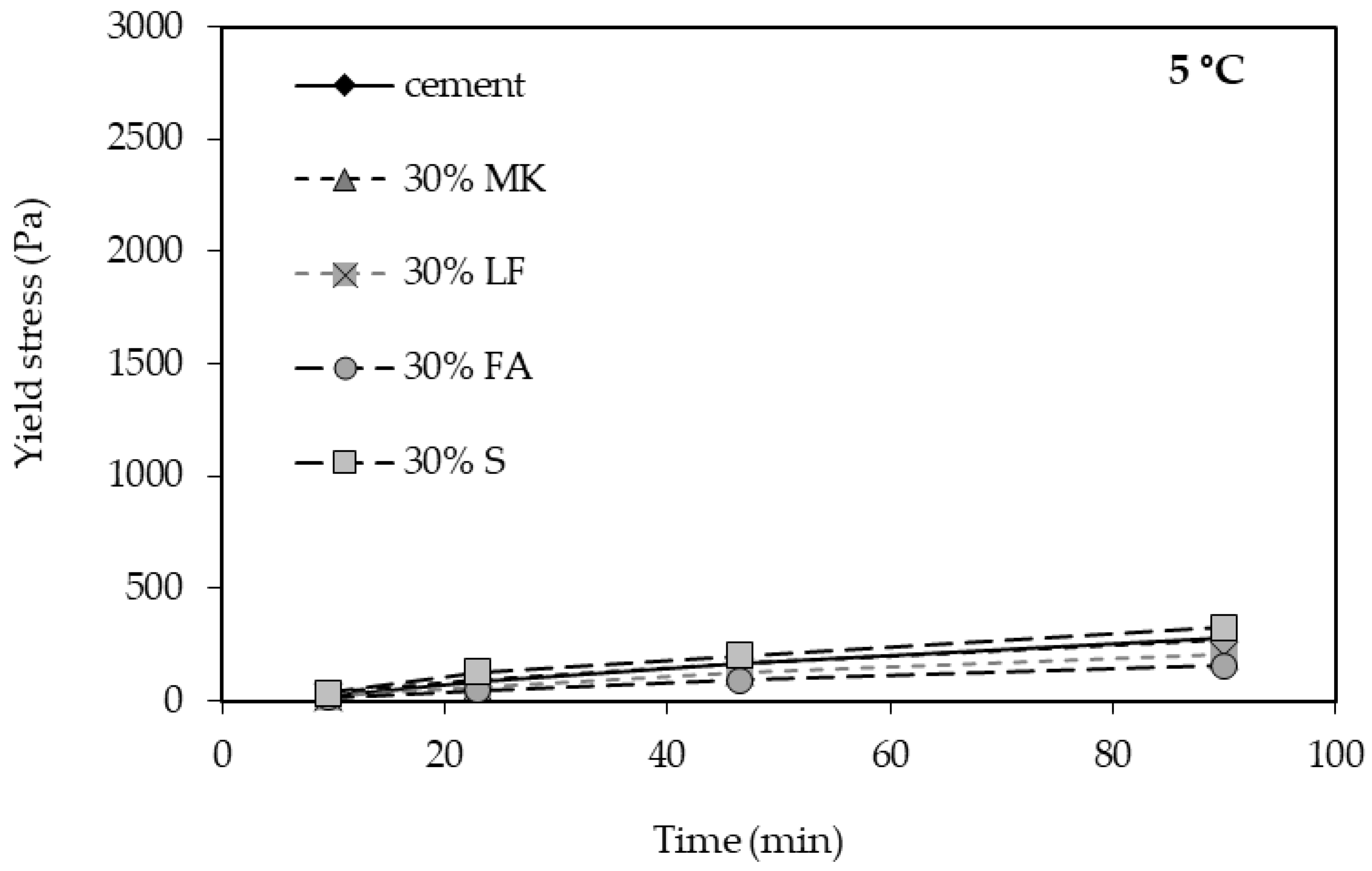

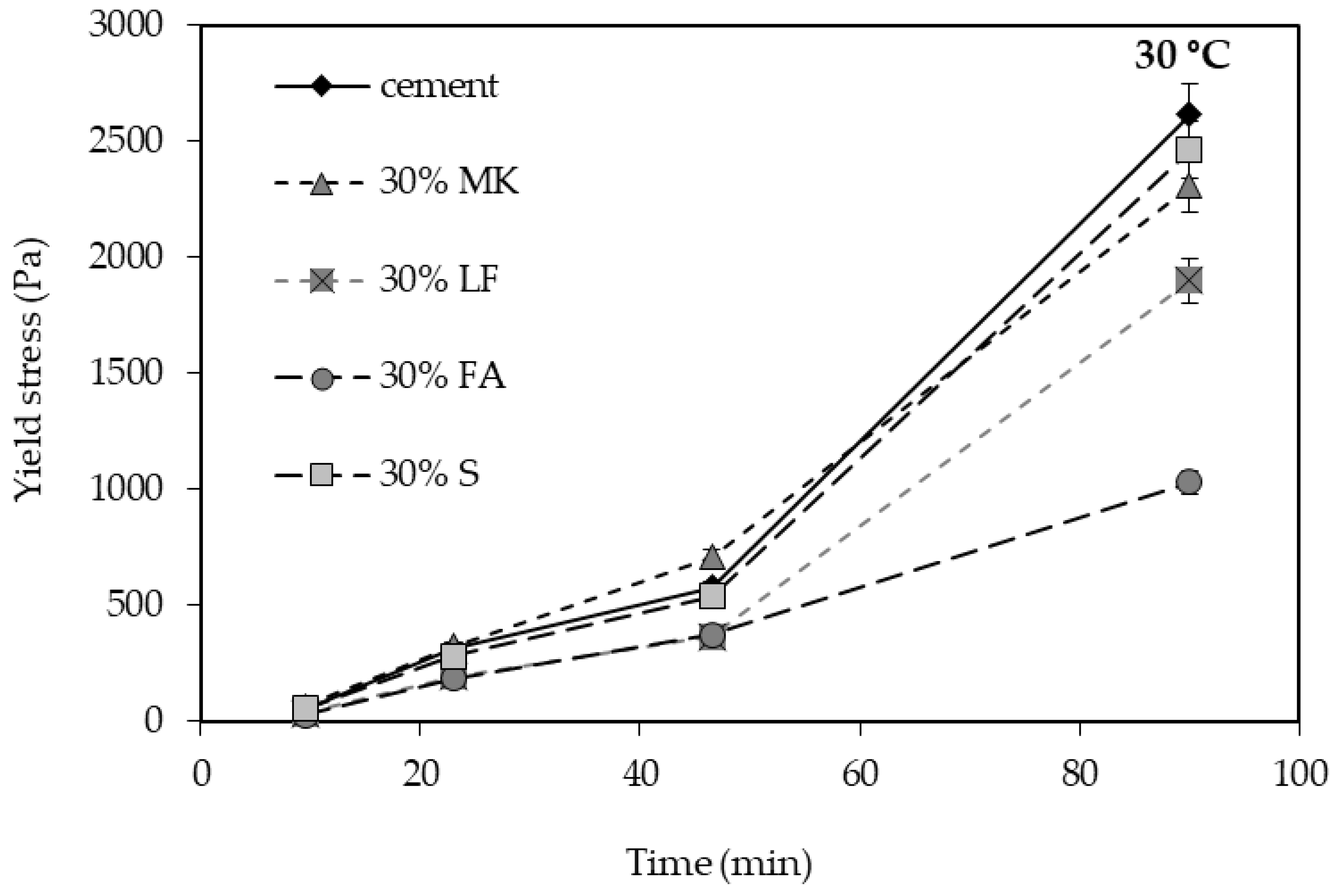

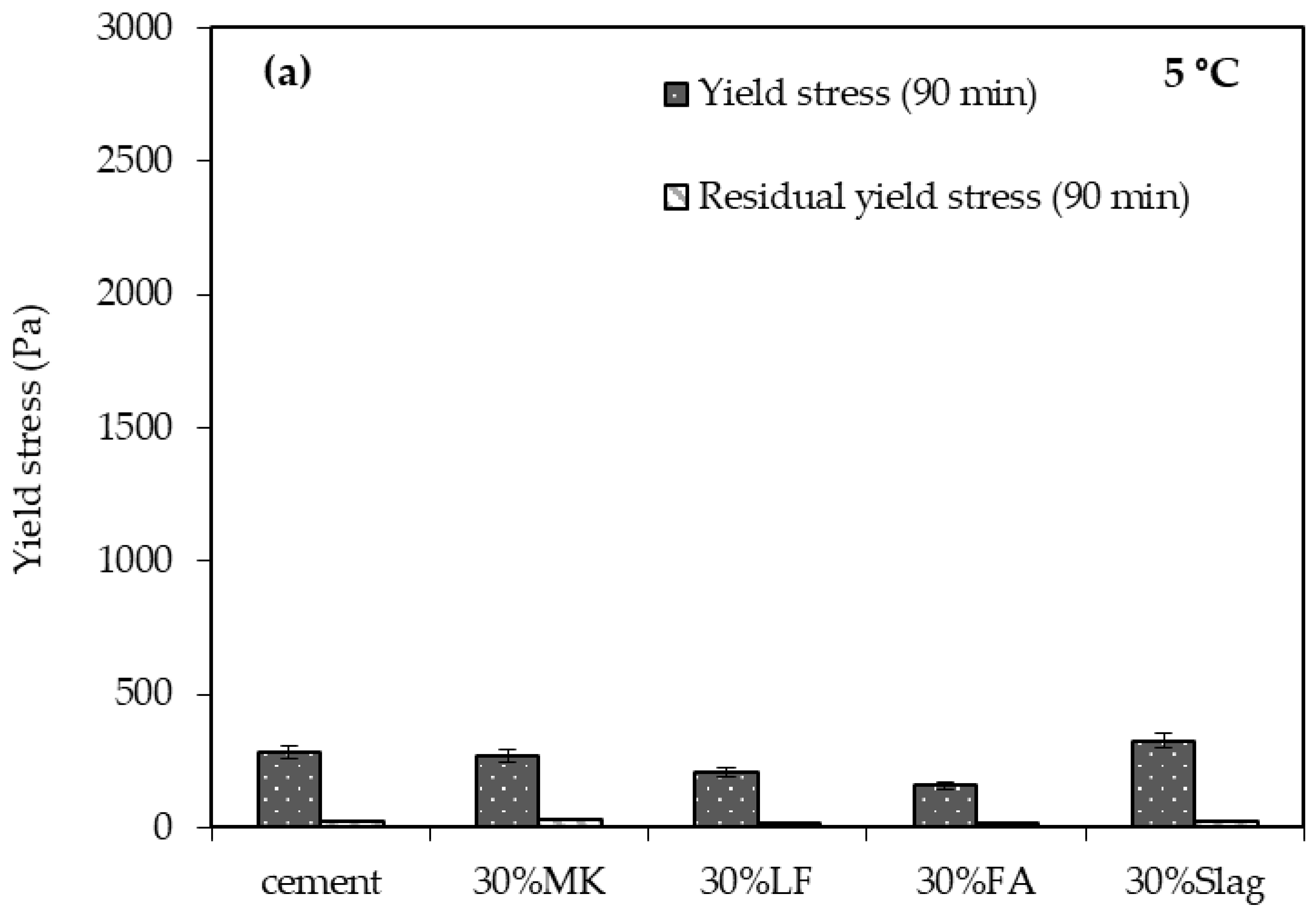

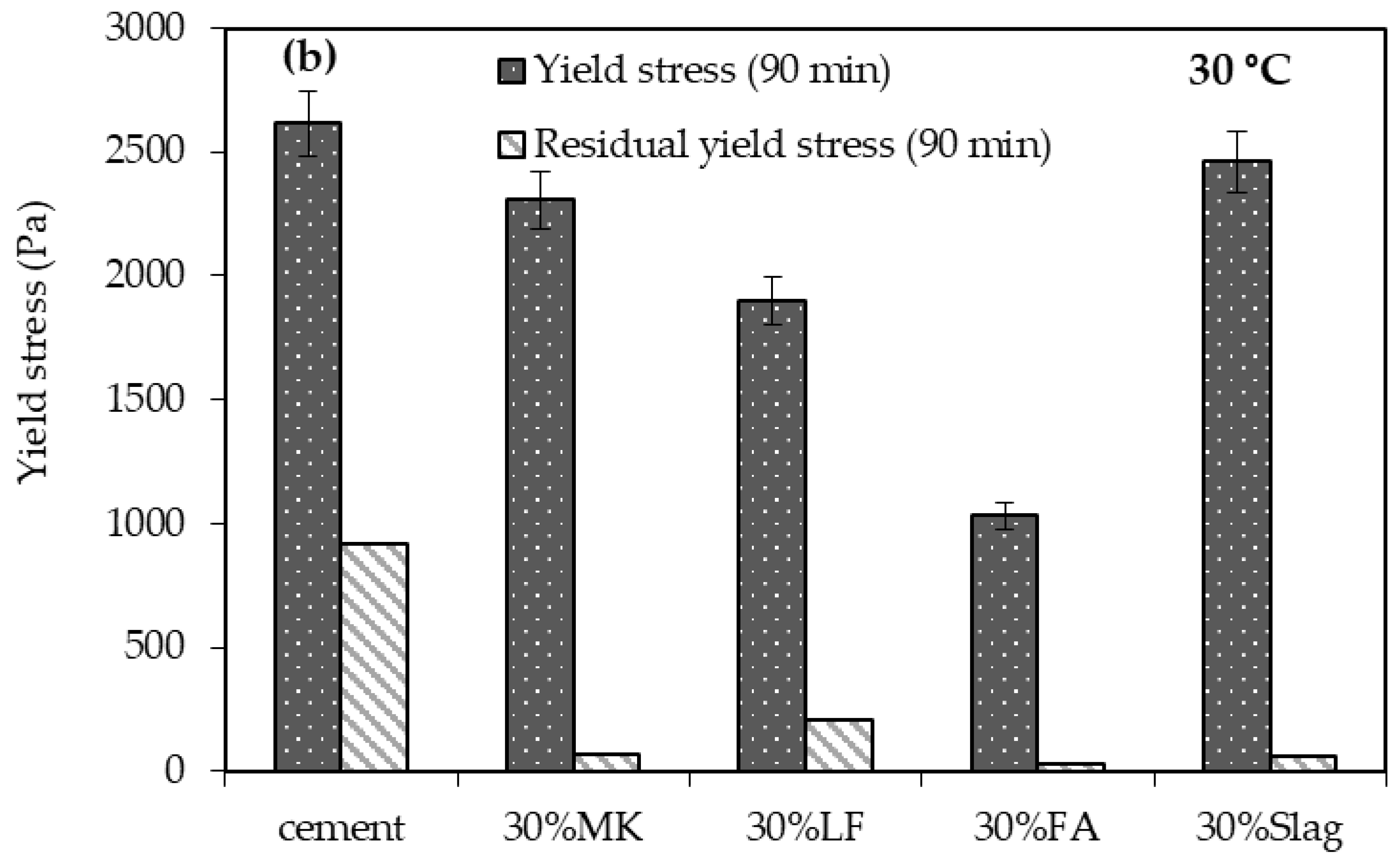

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 present the evolution of the total and residual (irreversible) yield stress of the reference and blended cement pastes tested at 5 °C and 30 °C. The results highlight the pronounced influence of temperature on the kinetics of structural build-up.

At 5 °C (

Figure 8), all mixtures exhibited a very slow and limited increase in total yield stress, while the irreversible fraction was almost negligible (

Figure 10). This observation provides clear evidence that, at low temperature, chemical hydration reactions are strongly suppressed, and the observed structuration arises almost exclusively from physical flocculation and weak colloidal attractions. The long induction period and low ion mobility in the pore solution prevent the formation of stable hydration products such as C–S–H or ettringite, leading to a reversible network that can be completely destroyed upon re-shearing. This behavior highlights that irreversibility in build-up is directly governed by hydration kinetics: when hydration is inhibited, structural build-up becomes entirely reversible.

At 30 °C (

Figure 9), the overall rate of structural build-up increased markedly for all mixtures. Interestingly, the total yield stresses of S, LF, and MK became comparable to that of the reference paste, while FA remained significantly less structured. This convergence can be attributed to thermal activation of dissolution and ion diffusion, which accelerates both cement hydration and the limited reactivity of certain SCMs. Slag and Metakaolin, in particular, exhibit partial hydration at elevated temperature, contributing to a denser interparticle network, while limestone filler enhances hydrate nucleation and early particle cohesion.

However, the residual (irreversible) fraction remained significantly lower for all SCM-blended systems than for the pure cement paste, even at 30 °C (

Figure 10). This finding indicates that the mechanisms driving the apparent increase in structural build-up differ between the reference and the blended systems. In the CEM I paste, the acceleration of hydration leads to the rapid formation of permanent hydrate bridges (C–S–H bridging), producing a significant irreversible component. In contrast, in SCM-modified pastes, the temperature rise primarily amplifies physical flocculation and short-range colloidal interactions, without a proportional increase in chemical bonding. As reported by El Bitouri [

26], most of the structural build-up at elevated temperature remains reversible and is dominated by physical processes rather than by permanent hydrate connectivity.

Therefore, these results reveal that similar macroscopic stiffness can originate from distinct microscopic mechanisms. In the reference paste, higher temperature promotes hydrate precipitation and chemical rigidity, whereas in SCM-containing pastes, it mainly intensifies physical aggregation and temporary cohesion of particles. The persistence of a low irreversible fraction even at 30 °C (<10%) confirms that the early network remains weakly bonded. Comparable trends were reported by other authors [

12,

25], who reported that the structural build-up of blended systems is dominated by reversible interactions during the dormant period, with limited contribution from true hydration bonding.

In summary, increasing temperature amplifies the overall rate of structural build-up but does not necessarily enhance its irreversible component in SCM-containing pastes. At 30 °C, reactive additions such as slag, limestone filler, and metakaolin exhibit total structuration values approaching that of plain cement paste due to thermal acceleration, yet their mechanisms remain primarily physical and reversible. Fly ash, being the least reactive, maintains the lowest build-up. These findings highlight that an apparent increase in yield stress can arise from different microscopic mechanisms, chemical in neat cement and physical in blended systems, which must be considered when predicting early-age formwork pressure and stability.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the time-dependent structural build-up of cement pastes incorporating various SCMs under different w/b ratios and temperatures. Static yield stress measurements were used to quantify both the total and irreversible components of structural build-up, supported by complementary tests on flowability, hydration, and bleeding. This work provides a comparative quantification of total vs. irreversible structural build-up for several SCM-blended systems under varying temperatures. The results reveal that SCMs systematically reduce irreversible structuration, even when total structural build-up increases, highlighting a fundamental difference in the mechanisms governing early structuration between plain and blended binders.

The main conclusions can be summarized as follows:

Slag and fly ash decreased yield stress (−33% and −10%, respectively, vs. reference) and enhanced flowability due to their smooth particle surfaces and dilution effects, whereas metakaolin increased yield stress (+19% vs. reference) owing to its high surface area and angular or lamellar morphology.

Slag, limestone filler, and metakaolin accelerated early hydration; however, this acceleration did not translate into higher structural build-up. These results confirm that the early evolution of yield stress is governed primarily by physical flocculation and colloidal interactions, rather than by hydration-driven bonding.

All tested SCMs reduced bleeding compared with the reference paste. Fine or reactive additions (metakaolin, limestone filler) enhanced water retention through flocculation and nucleation effects, while smoother SCMs (slag, fly ash) improved stability mainly through packing refinement. These results show that early-age stability can be improved without increasing yield stress.

Elevated temperature (30 °C) significantly accelerated the structural build-up of all mixtures. However, while the reference cement paste exhibited a clear increase in irreversible structuration (from 25% at 20 °C to 35% at 30 °C), SCM-containing systems remained largely governed by reversible mechanisms, with the irreversible fraction consistently below 10%. This indicates that, in low-clinker binders, temperature predominantly amplifies physical aggregation rather than promoting hydration-driven chemical bonding.

In summary, the structural build-up of blended cement pastes results from a complex interplay between physical dispersion, colloidal aggregation, and early hydration processes. The present findings highlight that SCM-containing systems are predominantly governed by reversible, physically driven mechanisms, while hydration-induced bonding remains limited at an early age, especially under low-clinker conditions. These insights are directly applicable to the design of sustainable mixtures for self-compacting, pumpable, and 3D-printable concretes, where achieving an optimal balance between flowability, early stability, and buildability is essential. A clear understanding of how physical and chemical contributions interact, and how they respond to temperature variations, is therefore critical for optimizing the fresh-state performance and robustness of modern low-carbon cementitious systems.