1. Introduction

With the rapid development of urban construction, large-scale buildings have emerged continuously, featuring expanding scales, increasingly complex internal layouts, and significantly rising pedestrian density. Once a disaster occurs in such buildings, severe casualties and property losses are highly likely, attracting great attention from all sectors of society [

1]. During pedestrian evacuation after a fire, evacuation efficiency is often compromised by the combined effects of multiple complex factors: insufficient coordination among pedestrians makes it difficult to form an orderly evacuation; panic triggered by sudden fires spreads among the crowd, leading to frequent irrational behaviors; some pedestrians may suffer from syncope due to thick smoke and high temperatures, further blocking evacuation routes; in addition, unreasonable layout of some shopping malls significantly increases the difficulty of successful evacuation [

2]. Key factors restricting efficient evacuation include whether the evacuation path planning for pedestrians in shopping malls is scientific, whether the building layout meets emergency evacuation requirements, and whether the number of pedestrians meets safety thresholds [

3]. Establishing an algorithm capable of simulating pedestrian evacuation drills in fire scenarios and formulating scientific and effective fire-guided evacuation routes based on this algorithm not only provides practical guidance for pedestrian disaster avoidance in sudden fires but also offers important technical support and theoretical basis for the optimization and improvement of building structures.

To tackle these challenges, scholars have developed various pedestrian evacuation models, with mainstream approaches categorized into Cellular Automaton models [

4], Agent models [

5], Social Force models [

6], and Multi-Agent models [

7]. These models have been widely adopted for in-depth analysis and research on pedestrian evacuation within building areas, laying the foundation for understanding evacuation dynamics [

8]. In terms of Cellular Automaton models, Lili Liu et al. [

9] proposed a method considering pedestrian group cooperation, adopting a leader-follower mode to study evacuation efficiency under this framework. Dewei Li et al. [

10] further explored pedestrian evacuation characteristics based on site familiarity and aggressive strategies, finding that the proportion of conservative pedestrians significantly affects the distribution of these two factors. While these studies have advanced understanding of group cooperation and site familiarity, they lack consideration of individual physiological and psychological factors. Complementing this, Kelly Rendón Rozo et al. [

11] proposed a model integrating human behavioral heterogeneity and environmental interaction, incorporating special signal indicators to encourage pedestrians to open new routes during congestion.

Parallel to Cellular Automaton research, Agent models have been leveraged to integrate multiple evacuation-related indicators. Peng Lu and Yufei Li [

12] constructed an Agent-based evacuation model that incorporates evacuation time, stampede risk, and pedestrian health, revealing that evacuation risk is minimized during off-peak periods. Sheng-Hui Qin et al. [

13] further developed an Agent model based on group behavior characteristics, analyzing the effectiveness of individual and multi-person combined evacuation and providing technical references for university canteen evacuations. In the domain of Social Force models, Zhilu Yuan, Hongfei Jia et al. [

14] studied the impact of emergency signs on pedestrian evacuation under smoky conditions, identifying herding behavior and expected speed as key influencing factors. Nathan Wood et al. [

15] extended this line of research to tsunami evacuation, comparing standard and extreme evacuation zones to explore speed differences. Masayuki Fujita et al. [

16] further refined direction selection by incorporating environmental unfamiliarity, accessibility, attractiveness, popularity, and path congestion. Beyond traditional models, intelligent algorithms have emerged as powerful tools: Nan Jiang et al. [

17] proposed a deep learning-based pedestrian dynamics model to evaluate curve entry feasibility, while Jinlei Gu et al. [

18] used deep reinforcement learning to model panic-induced evacuation and dynamic sign guidance. Other scholars have supplemented these efforts through pedestrian flow prediction, model optimization, and reinforcement learning applications [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], further enriching the research landscape.

Collectively, these existing studies have conducted extensive and valuable explorations on pedestrian evacuation modeling. Based on Cellular Automaton models, scholars have advanced understanding of group cooperation modes and the impacts of site familiarity and aggressive strategies; Agent models have enabled comprehensive evaluation of multi-dimensional indicators; Social Force models have clarified the effects of emergency signs and herding behavior in smoky environments; and the integration of deep learning and reinforcement learning has optimized scenario modeling and dynamic guidance. These achievements have revealed core evacuation influencing factors from multiple dimensions, laying an important theoretical and technical foundation for evacuation simulation.

Despite these significant advancements, the increasing complexity of modern building environments has exposed three key limitations in current research. First, Cellular Automaton and Agent models primarily focus on group-level evacuation efficiency optimization but rarely analyze the dynamic selection mechanism between autonomous and herding strategies based on individual physiological and psychological differences. Second, existing Multi-Agent models generally simplify individual characteristics and adopt static environmental interaction frameworks, failing to reflect real-world complexity. Third, traditional PSO algorithms for evacuation path planning mostly prioritize geometric shortest path search, without integrating pedestrian density congestion costs or hazard field risk optimization—making them ill-suited for practical complex disaster scenarios.

To address these aforementioned limitations, this study constructs a comprehensive pedestrian evacuation analysis system through three core improvements. First, a hybrid-characteristic Multi-Agent model is developed based on multi-dimensional feature coupling (integrating individual physiological and psychological characteristics, dynamic hazard field characteristics, and pedestrian density characteristics) and dynamic environmental interaction design, overcoming the simplification of individual traits and static interaction in traditional models. Second, a PSO pedestrian density cost function and micro-objective update strategy are introduced to decompose long-term exit targets into locally perceivable micro-objectives, while jointly modeling herd following and density congestion suppression mechanisms to solve the problems of insufficient risk optimization and single-strategy dependence in traditional PSO. Third, Cellular Automaton (CA) is used to discretize evacuation space and visualize dynamic processes, with a simultaneous establishment of an interpretability analysis (Shapley/Sobol analysis), Uncertainty Quantification (UQ), and algorithm robustness/vulnerability evaluation system. The effectiveness of each improved module is verified through key module ablation experiments [

24]. Finally, this study provides quantitative basis and technical suggestions for the optimization of practical building evacuation systems and disaster emergency strategy formulation by analyzing core indicators such as clearance time, congestion duration, and pedestrian arrival rate.

2. Materials and Methods

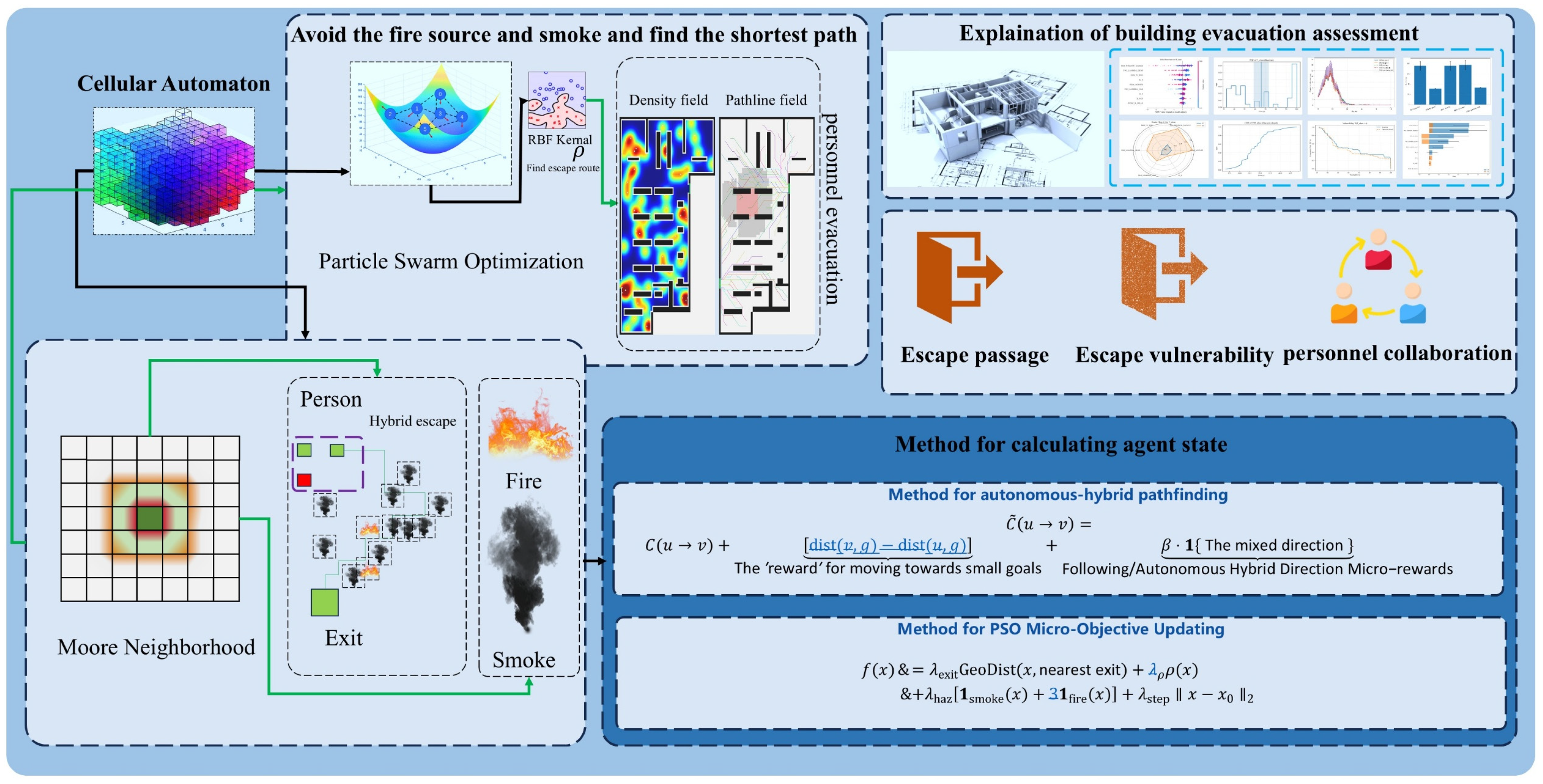

Figure 1 shows the overall framework of the pedestrian evacuation model proposed in this study. As a core visualization carrier, it fully presents the entire process of the model from algorithm integration to evaluation implementation: at the bottom layer, Cellular Automaton (responsible for spatial discretization and group movement simulation) is combined with PSO micro-strategies (optimizing individual evacuation decisions). Based on this, an autonomous-hybrid pathfinding model is constructed, which can not only perceive dynamic environmental changes in real time to adjust strategies autonomously but also integrate static preset and dynamic planned paths to adapt to complex scenarios. Meanwhile, the framework embeds interpretability Shap/Sobol analysis (quantitatively decomposing the contribution of influencing factors and evaluating the impact of parameter fluctuations on results) and CDF/PDF analysis (statistically analyzing the probability laws of indicators such as evacuation time and pedestrian safe arrival probability). Finally, a comprehensive evaluation of pedestrian evacuation strategies during building disasters is completed from the dimensions of feasibility (e.g., whether high-proportion safe evacuation can be achieved) and reliability (e.g., the fluctuation range of results under different scenarios) [

25,

26].

Figure 2 outlines the “CA Grid + PSO Micro-objective” model adopted in this study and its evaluation process. Subfigure (A) illustrates the scenario on a discrete grid: circles represent pedestrians, arrows indicate single-step movements, green areas denote exits, light blue/grey regions represent smoke, and orange regions indicate the fire source. Pedestrians advance towards exits under the influence of fire and smoke as well as geometric constraints. Subfigure (B) presents the PSO micro-objective mechanism: particles are placed within a local window centered on each pedestrian, and a search is performed based on the objective function to identify the global best particle, which serves as the micro-objective for the current step. The legend labels elements such as “evacuees, smoke/fire, and step size regularization”. Subfigure (C) depicts conflict resolution: when multiple pedestrians compete for the same target grid cell, processing is conducted in accordance with rules to avoid collisions. Subfigure (D) shows the output indicators: total clearance time, the 95th percentile time of surviving pedestrians, and optional bottleneck occupancy curves are recorded and summarized.

2.1. Establishment Method of Cellular Automaton

In the Cellular Automaton modeling space, the grid is divided into a two-dimensional raster, denoted as , where represents rows and represents columns. The model is established according to actual on-site scenarios. Subsequently, the unit length is fixed as the size of the cellular grid, and the time step is fixed as . Cells are allowed to move in 8 directions, defined as , which is used to describe the movement direction of cellular particles.

2.2. Establishment of Cellular Particle Geometric Distance Field

For any passable grid, the 8-neighborhood shortest distance

from the grid to the exit set

is defined as shown in Equation (1). Here,

is a static geometric potential field, which reflects the pure geometric shortest path and is used for PSO fitness and geometric guidance analysis in subsequent algorithm design.

where the grid weight

is defined as shown in Equation (2), which clarifies the distances of diagonal and right-angle neighborhoods.

2.3. Kernel Estimation Method for Pedestrian Density

During pedestrian movement, for each surviving and non-evacuated agent

i with coordinates

, a smooth density field

is obtained by superimposing Gaussian discrete kernels

. Discrete pedestrian groups are converted into a continuous field using kernel density, which is used in fitness modeling to avoid pedestrian congestion. The specific formulas are shown in Equations (3) and (4).

2.4. Propagation Method of Hazard Field

Based on the Moore norm, a random rounding method is used to construct the theoretical continuous propagation distance, i.e., . Subsequently, the continuous distance is randomly rounded to an integer radius , so that the statistical characteristics of the integer radius are consistent with the theoretical continuous distance .

Then, a method for calculating the fire spread probability is constructed. If the current burning grid is

, the ignition probability of the flammable grid

within its Moore radius is assigned according to the adjacency type, defined as shown in Equation (5).

where

;

is defined as the ignition probability of right-angle neighborhoods, set to 1.0;

is defined as the ignition probability of diagonal neighborhoods, set to 0.8. The smoke spread probability is the same as that of fire.

2.5. Calculation of Candidate Grid Cost Function

Let the current grid be

and the candidate next grid be

. A greedy step-by-step method is adopted to score each of the 8 neighboring candidates, and the grid with the minimum total cost is selected as the final candidate. The core cost is defined as shown in Equation (6).

In the equation: is the geometric step cost; is the value of the pedestrian density field at ; and are indicators for smoke and fire, respectively, which impose fixed penalties when entering smoke or fire areas; is the repulsion field; indicates complete sensitivity to smoke, and indicates complete insensitivity to smoke. The values of , , , and are set to 0.5, 2.0, 12.0, and 0.05, respectively. The penalty for fire is +12, which is much larger than the geometric cost, so fire is almost always avoided; the penalty for smoke is +2, whose intensity is linearly related to individual risk; the flexible penalty for density is +0.5, which is used to avoid congestion.

Finally, the calculation method for the next step is shown in Equation (7). By enabling autonomous-following hybrid mode, pedestrians are guided to move toward micro-objectives and in the hybrid autonomous-following direction.

In the equation: is the local micro-objective searched by PSO; if moving closer to , , this term becomes negative, and the system coefficient is set to . Micro-objectives decompose the long-term exit target into small steps toward micro-objectives, forming perceivable local attraction. If the discrete direction of the current step is consistent with the autonomous-following hybrid direction, is added to provide a slight push in the same direction.

2.6. Autonomous-Hybrid Direction Relationship

For each individual, two types of expected directions are calculated and linearly integrated to obtain the discrete preference direction

, as shown in Equations (8) and (9). Through PSO-based micro-objective calculation at each step, a small direction micro-reward is obtained, which further affects the total score of each step, achieving guidance without domination.

where

is the unit grid direction toward the micro-objective g;

is the maximum discrete direction of the intensity field

within the neighborhood;

is the weight of the autonomous term, set to 1.0;

is the weight of the following term, set to 1.0;

is the mixing coefficient, set to 0.4.

2.7. PSO Micro-Objective Update Strategy

2.7.1. Calculation of Objective Function

For the particle position

, its fitness is calculated as shown in Equation (10).

In the equation: is the current position of the agent; are weights; ensures that particles never enter fire areas. The values of , , , and are set to 1.0, 0.6, 3.0, and 0.10, respectively. For more accurate analysis, perturbation sampling is conducted on these parameters in subsequent SHAP/Sobol analysis to ensure reasonable parameter selection.

2.7.2. PSO Update Method

For the

-th particle at the

-th iteration, updates are performed using the following equations (Equations (11)–(13)).

where

is the historical individual best of particle

;

is the global best;

and

are dimension-wise independent random vectors;

denotes element-wise multiplication;

decreases linearly;

and

are set to 1.5.

2.8. Indicators and Statistics

In this study, clearance time T_clear and 95% pedestrian evacuation time are selected as core evacuation indicators. For UQ sampling, fixed parameters are used [

27], 50 random seeds are set, and PDF/CDF boxplots are generated. Under the baseline of closed exit conditions, the vulnerability curve is calculated as

, where

is the scanning interval. On this basis, guidance baselines under geometry-only conditions (without PSO), no herd following, no density term, and geometry-only state are established for ablation experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Experiment of Pedestrian Evacuation

To conduct effective pedestrian evacuation experiments, tests were carried out in an underground shopping mall in Shaanxi Province, China, and a scenario with an irregular internal structure of the mall was constructed. According to verification by the mall operator and public records, no similar fire incidents had occurred at the site by the time of the study.

Figure 3 shows a schematic plan view of the fire evacuation simulation. Black lines define the distribution of walls (Wall), which divide the space into different areas to simulate the internal structure of the building. Green “A” symbols represent alarms (Alarm), which can trigger alerts to prompt pedestrian evacuation when a fire occurs. Open areas without connections are marked as escape exits (Escape Exit), which are key channels for pedestrian evacuation during fires. Colored dots represent pedestrians escaping from the fire (People Who Escaping). The overall layout is presented in a grid form, clearly showing the spatial distribution, obstacle locations, alarm settings, and escape exit positions within the building, providing an intuitive spatial reference for fire evacuation simulation research. The evacuation area in the figure is an irregular region with a length of 54 m and a width of 43 m. In this study,

is set to 0.1 s, the grid size

is set to 0.25 m, and the number of pedestrians is 60.

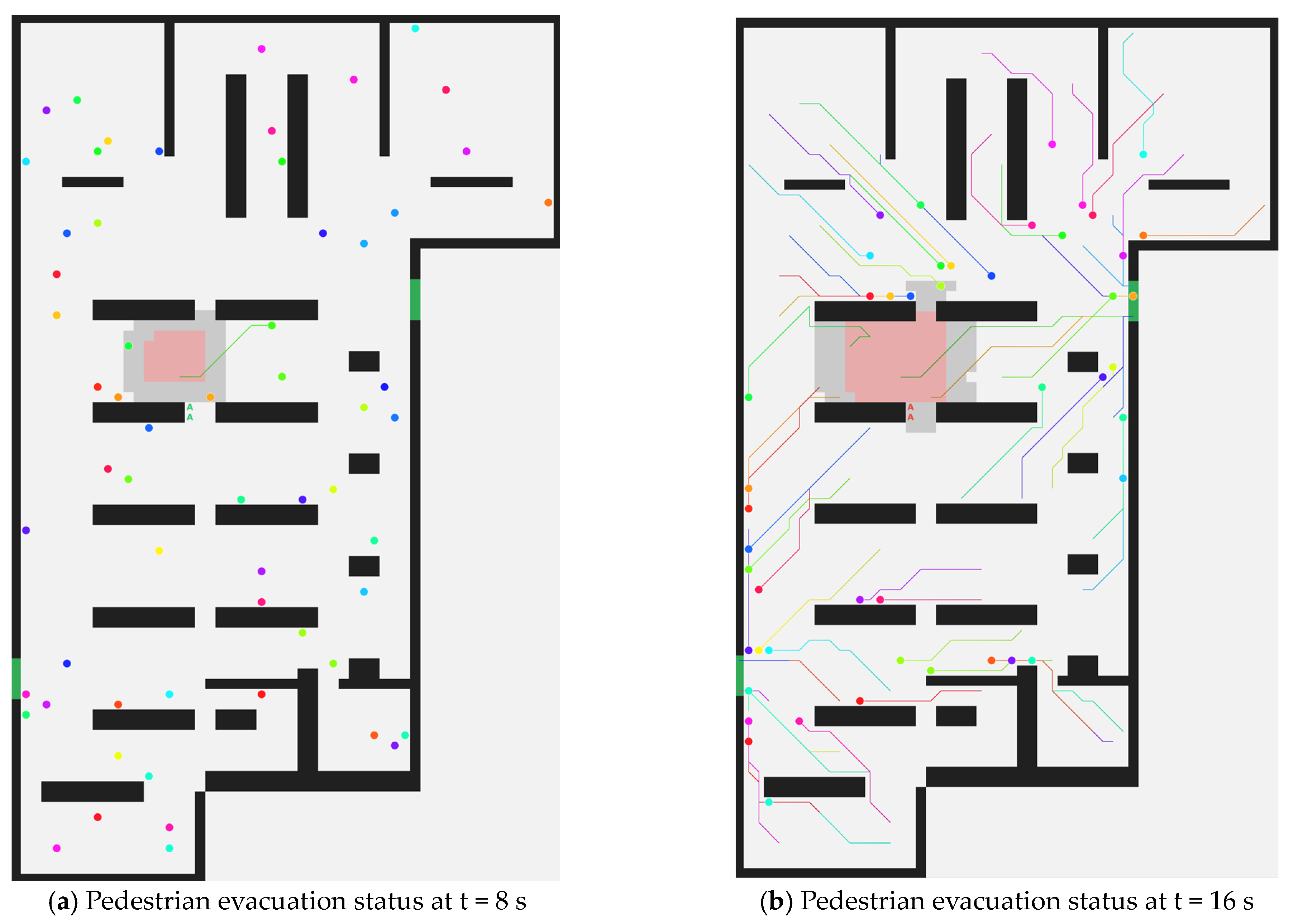

Figure 4 shows the combined pedestrian evacuation path planning and trajectory diagram. Two color schemes are used to indicate the pedestrian combination state: blue indicates pedestrians adopting autonomous hazard avoidance, while other colors indicate pedestrians adopting hybrid hazard avoidance. All pedestrians completed evacuation a t = 33 s. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) show the evacuation status at t = 8 s, t = 16 s, and t = 24 s, respectively; the movement trajectory of each particle is shown in subfigure (d).

Figure 5 shows the density heatmap of combined pedestrian evacuation during the evacuation process, presenting the density distribution of pedestrians. White dots represent pedestrians, and the red-blue color scale indicates the pedestrian distribution: darker red indicates a larger number of pedestrians, while darker blue indicates a smaller number of pedestrians. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) show the pedestrian distribution during evacuation: pedestrians are evenly distributed in (a); pedestrians gradually move closer to the two exits in (b); pedestrians are mainly concentrated at the exits in (c); all pedestrians have completed evacuation in (d). This figure can be used to analyze the reasonable building structure and pedestrian evacuation congestion, providing a basis for subsequent analysis.

3.2. Interpretability Analysis of Pedestrian Evacuation Results

For the algorithm results, key physical variables in this study are decomposed into items with physical meanings and adjustable frequencies. The parameter selection is shown in

Table 1, and Shapley and Sobol analyses are used to analyze the algorithm results.

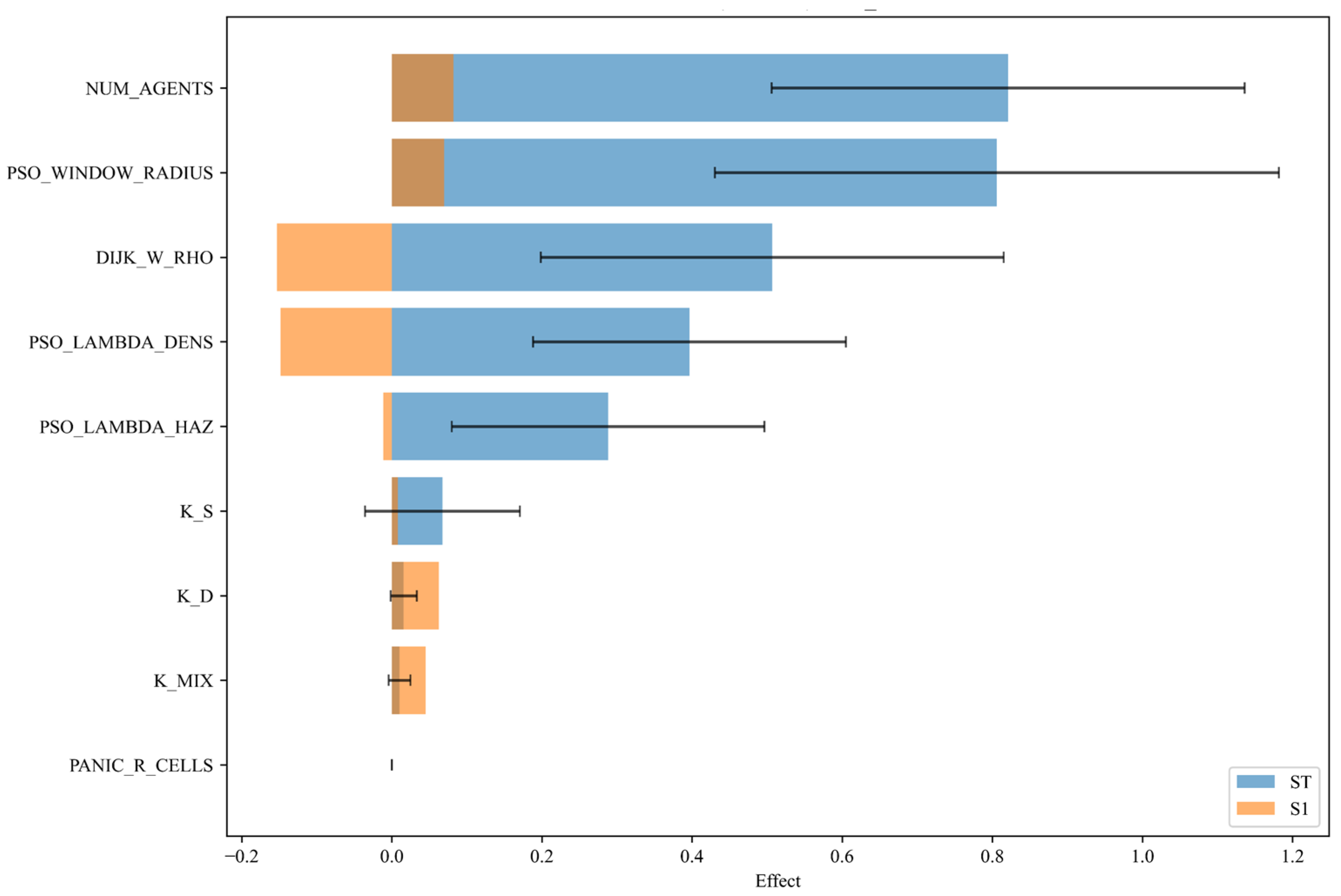

3.2.1. Shapley Analysis

For more accurate analysis, we employed Shapley Analysis to evaluate the algorithm’s operational performance, and the results are presented below.

Shapley analysis was conducted using 100 sets of independent parameters, with 4 random seeds for each set. The results are shown in

Figure 6: subfigure (a) presents the Shapley analysis results for full pedestrian evacuation, and subfigure (b) presents those for the 95th percentile evacuation time of surviving pedestrians, corresponding to subfigures (c) and (d), respectively.

The SHAP beeswarm plot for T_clear (subfigure (a)) reveals the key parameters affecting the total evacuation clearance time and their mechanisms, with the “vision range-density avoidance” parameter combination as the core dominant factor (corresponding to subfigure (c)). Specifically, PSO_WINDOW_RADIUS is the most influential parameter; its high values (red dots concentrated in the right region of SHAP values) show a strong positive correlation with T_clear. This is because although a larger vision range allows individuals to avoid local congestion or hazard areas, it leads to excessive detours in path selection. Combined with the constraints of Cellular Automaton (CA) rules and conflict blocking effects, the overall evacuation process is prolonged.

High values of PSO_LAMBDA_DENS and DIJK_W_RHO (both representing density aversion coefficients) also show the characteristic of red dots shifting to the right, indicating that an overly strong density penalty mechanism triggers synchronized detour behavior among the crowd, leading to extended congestion waves or stagnation at bottlenecks, and ultimately increasing T_clear.

The impact of K_D (herd intensity coefficient) on T_clear is generally weakly positive. Although herd movement may improve local evacuation efficiency in some scenarios, it is more likely to cause aggregation effects at key nodes such as narrow passages, increasing the average congestion probability. The impact of NUM_AGENTS (number of evacuees) conforms to capacity constraint intuition; high values (red dots distributed on the right) correspond to longer T_clear, reflecting the direct constraint of pedestrian quantity on the evacuation system capacity. The impact of PSO_LAMBDA_HAZ (hazard aversion coefficient) on T_clear is of moderate intensity with uncertain direction: moderate hazard avoidance can reduce individual stagnation caused by hazards such as fire and smoke, but an overly strong avoidance tendency leads to excessive detours, also exerting a negative impact on evacuation efficiency.

In contrast, the marginal contributions of K_S, K_MIX, and PANIC_R_CELLS to T_clear are small, with SHAP values concentrated near 0. This suggests that within the current parameter range and scenario geometry, these parameters have limited regulatory effects on the total clearance time.

The SHAP beeswarm plot for the 95th percentile evacuation time of survivors (subfigure (b)) clearly shows that hazard aversion-related parameters are the core dominant factors regulating T_clear, presenting a rule of “single factor dominating the long-tail characteristic” (corresponding to subfigure (d)). Among them, PSO_LAMBDA_HAZ (hazard aversion coefficient) has the most significant and strongly monotonic impact on T 95% alive: high values of this parameter (red dots) are concentrated in the right region of SHAP values, while low values (blue dots) are concentrated in the left region, indicating a significant positive correlation between hazard penalty intensity and T 95% alive. The mechanism is that higher hazard sensitivity drives surviving individuals to prioritize evacuation paths with higher safety but greater detours and lower efficiency. Although this ensures individual survival, it significantly prolongs the evacuation time of the tail-end surviving group, ultimately increasing the 95th percentile evacuation time.

DIJK_W_RHO (density weight coefficient), PSO_WINDOW_RADIUS (vision range radius), and PSO_LAMBDA_DENS (density aversion coefficient) exert secondary positive impacts on T 95% alive: high values of all three parameters correspond to positive SHAP values, indicating that enhanced density aversion and expanded vision range also prolong the tail-end evacuation time of survivors. However, from the dispersion and distribution range of SHAP values, their intensity and directness are significantly weaker than those of PSO_LAMBDA_HAZ.

The marginal impacts of K_D (herd intensity coefficient), K_S, K_MIX, and PANIC_R_CELLS (panic impact grid radius) on T 95% alive are generally weak, with SHAP values concentrated near 0. This indicates that within the parameter range and scenario settings of this study, these parameters have limited regulatory effects on the 95th percentile evacuation time of survivors. Notably, the impact of NUM_AGENTS (number of evacuees) on T 95% alive is also insignificant: although an increase in pedestrian quantity usually prolongs the overall evacuation clearance time (e.g.,T_clear), its priority is far lower than that of the hazard aversion mechanism for the “slow tail-end evacuation process of the surviving group”, reflecting that T 95% alive is significantly more sensitive to hazard avoidance strategies than to the total number of pedestrians.

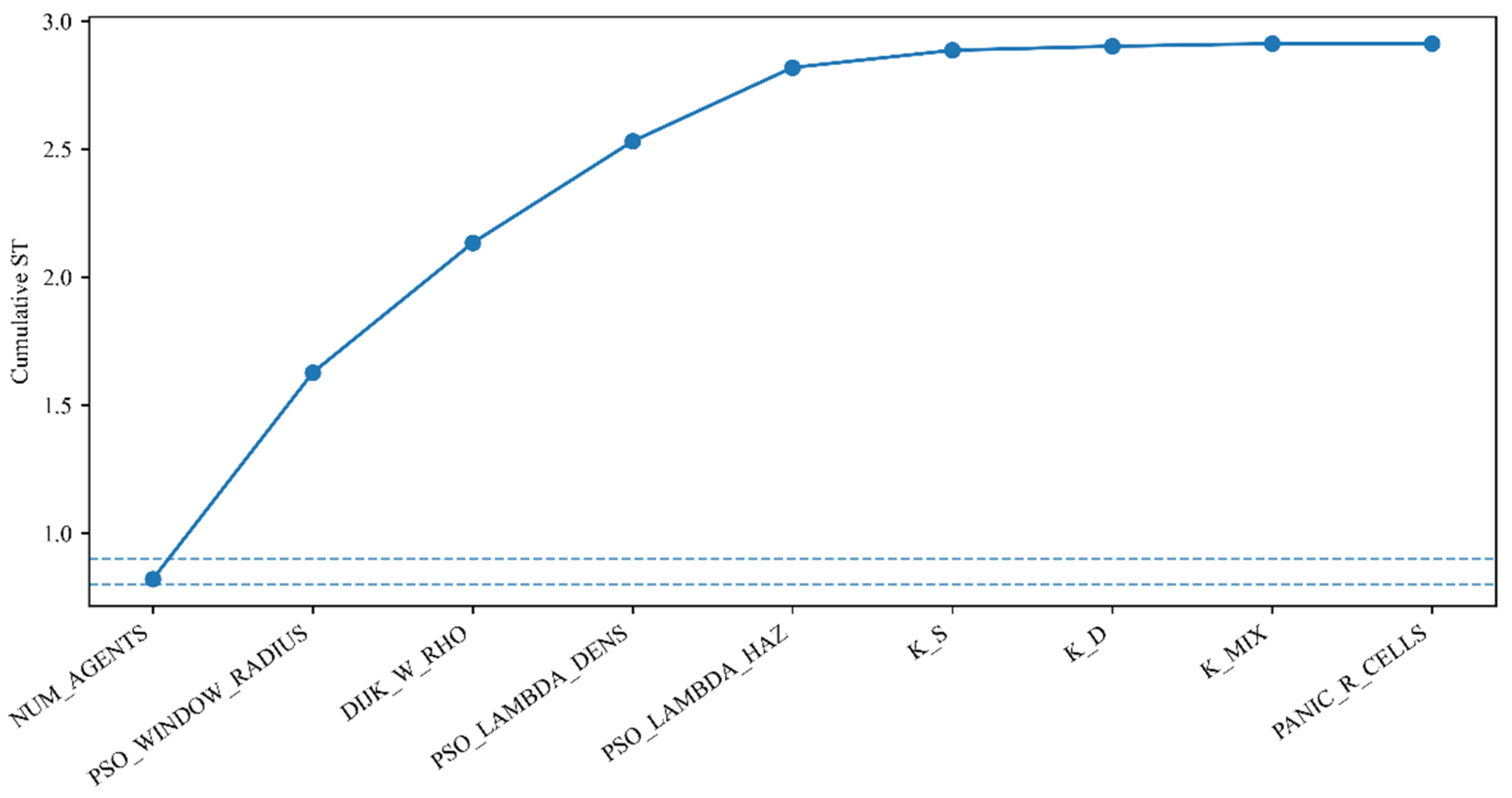

3.2.2. Sobol Analysis

Sobol analysis uses the same set of features and ranges as Shapley analysis (shown in

Table 1). The first-order effect S_1 and total effect S_T are selected for comparative analysis, and the results are shown in

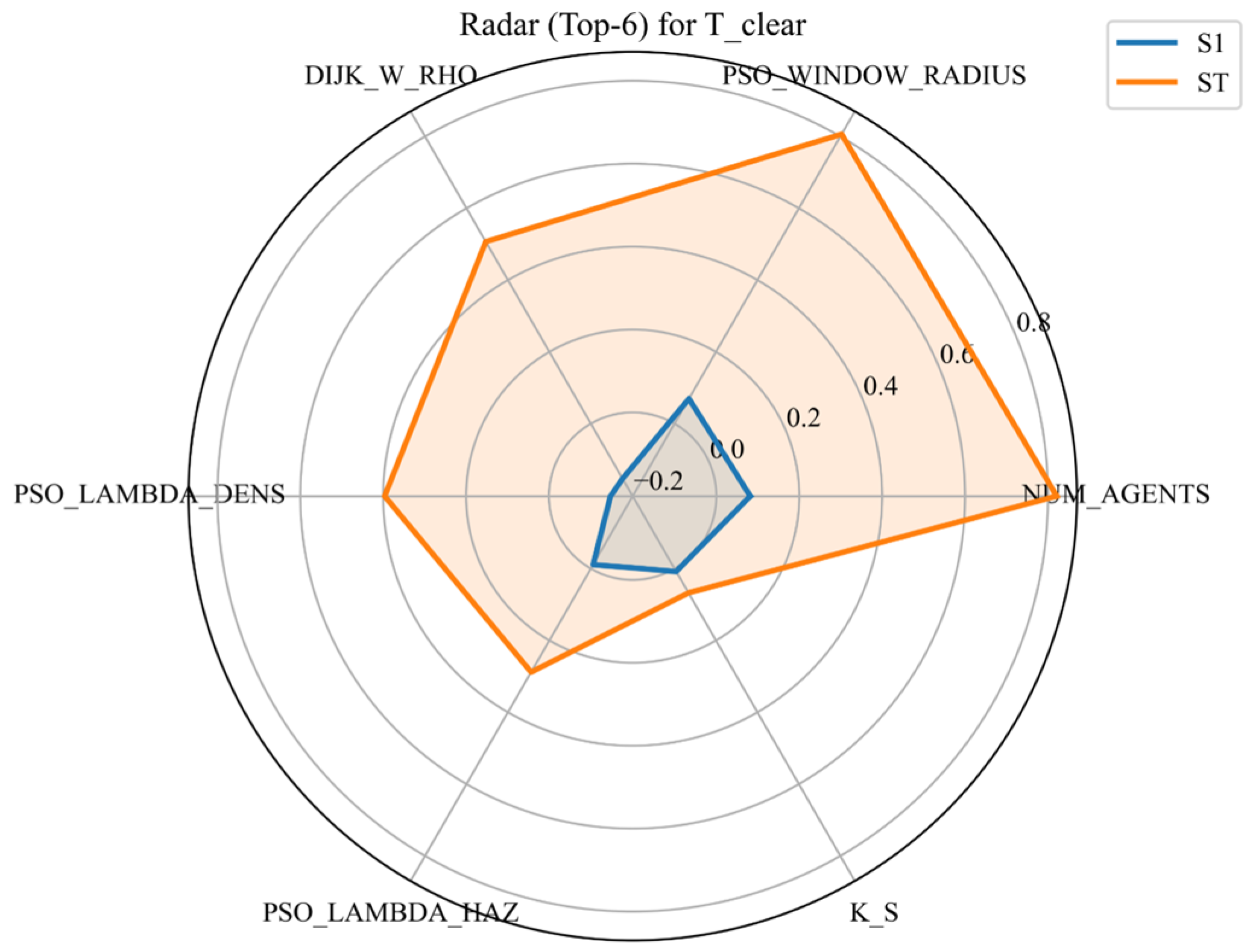

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

Figure 7 shows a tornado plot comparing the Sobol first-order effect S_1, orange) and total effect (S_T, blue). Confidence intervals for S_T are indicated by black horizontal error bars; blue bars represent the point estimates of S_T; black error bars represent uncertainties caused by limited samples and model randomness. Results show that S_T of NUM_AGENTS and PSO_WINDOW_RADIUS is approximately 0.8, much higher than that of other parameters, indicating that the uncertainty of the total pedestrian evacuation time is mainly driven by “pedestrian quantity scale” and “micro-objective search window”. In contrast, their S_1 values are very small (close to 0), while DIJK_W_RHO, PSO_LAMBDA_DENS, and PSO_LAMBDA_HAZ have moderate S_T values (approximately 0.3–0.5). Slightly negative small S_1 values are attributed to sampling estimation noise, which is equivalent to “weak first-order impact” and does not affect the conclusion that “total importance is mainly judged by S_T”.

Figure 8 shows the cumulative sum of S_T in descending order, quantifying “how many parameters are needed to explain most of the variance”. The curve exceeds 1.6 after the first two parameters (NUM_AGENTS, PSO_WINDOW_RADIUS), approaches 2.1 after adding DIJK_W_RHO, and reaches approximately 2.5–2.8 after further adding PSO_LAMBDA_DENS and PSO_LAMBDA_HAZ. Combined with the 0.8/0.9 reference lines in the figure, it can be seen that the first 2–3 parameters can cover most of the total effect, and the first 5 parameters can explain almost all observable variations. This provides direct basis for subsequent model simplification and experimental design (prioritizing control of the first 3–5 key factors).

By definition, the total-order index satisfies S_T

S_1; thus S_T

S_1 quantifies contributions from interactions and higher-order/non-monotonic effects.”

Figure 9 compares the first-order

and total-order

Sobol indices for the top six parameters. For all parameters, S_T ≥ S_1 by definition. The largest gaps S_T-S_1 occur for NUM_AGENTS and PSO_WINDOW_RADIUS, indicating strong interaction and/or non-monotonic effects beyond first-order contributions. Large gaps for NUM_AGENTS and PSO_WINDOW_RADIUS imply that their influence is dominated by interactions; DIJK_W_RHO, PSO_LAMBDA_DENS, and PSO_LAMBDA_HAZ form secondary lobes, suggesting coupling between congestion penalties and hazard aversion.

3.3. Uncertainty and Robustness Analysis

For effective analysis, 50 runs were conducted, and two scenarios (Baseline with two original exits and “One exit closed” with one exit closed) were compared using T_clear and T 95% alive as indicators. Empirical CDF, PDF, boxplots, and vulnerability curves were used to characterize differences from three perspectives: distribution, quantile, and exceedance probability.

Figure 10 generally depicts the box plots comparing the scenario with exits closed and the baseline scenario. In

Figure 11, subfigures (a) to (d) show the CDF plots of the two indicators under the “Baseline” and “One exit closed” scenarios, presenting the distribution positions and tail behaviors. For T 95% alive, the two curves highly overlap in the 0.2–0.9 quantile range, with only a slight misalignment near the median. This indicates that closing one exit has little impact on the overall position of the “time required for 95% of surviving pedestrians to complete evacuation”, but the right tail converges slightly, resulting in fewer extremely slow cases. For T_clear, the curve for the exit-closed scenario shifts to the left in the high quantile range (e.g., 0.8–0.95), indicating a reduced probability of long clearance times; in other words, the long-tail risk of very long clearance is mitigated. Overall, the key conclusion from the CDF plots is that closing one exit does not significantly change the evacuation efficiency of typical cases, but it can suppress the long tail of T_clear and reduce the probability of clearance delays caused by extreme congestion. This implies that management does not need to adopt a one-size-fits-all approach of “more exits are better”; instead, the “system benefit” of each exit should be evaluated through simulation/monitoring. Under necessary circumstances, some underperforming exits can be temporarily closed or restricted, or crowds can be guided to merge into more efficient paths earlier to mitigate long-tail risks.

Subfigures (e) to (h) show the PDF plots, which further characterize the central tendency and dispersion. For T 95% alive, both scenarios show a single peak, with the main distribution concentrated in the 30 s range; compared with the Baseline, the “One exit closed” scenario shows a narrower main peak and a shorter right tail, indicating slightly smaller differences between individuals and better stability. For T_clear, the density under the Baseline is more dispersed, with an obvious long tail and secondary peak on the right, reflecting delayed clearance in some simulations; in the “One exit closed” scenario, the density is more concentrated in the medium-time range, with reduced weight in the right tail, suggesting that extreme congestion cases are suppressed. Consistent with the CDF conclusions, the PDF plots focus on revealing changes in distribution shape: the typical level remains basically unchanged, but the fluctuation range and the incidence of ultra-long-time events decrease when one exit is closed.

Figure 12 shows the exceedance probability curve (survival function) of the clearance time T_clear:

. A lower curve indicates a smaller probability that “clearance time exceeds

at a given threshold

, meaning a more robust system. Overall, the orange dashed line (one exit closed) lies below the blue solid line (Baseline) in the range of

, with a typical difference of 3–10 percentage points (e.g., decreasing from

to

at

. This indicates that under the current layout and behavior rules, closing one exit reduces the probability of clearance time exceeding the threshold, making evacuation faster and more predictable. The two curves almost overlap at very short thresholds

, indicating that extremely fast clearance is inherently rare. The gap between the two curves converges at larger thresholds

and both decrease to 0 as

. However, long-tail risks still exist, and reducing exit options actually mitigates path diversion and conflicts. Nevertheless, the effect magnitude is limited and model-dependent, so careful evaluation based on geometry and crowd management strategies is still required in practical facilities.

3.4. Comparative and Ablation Analysis

To better analyze the algorithm results, comparative and ablation analyses were conducted using the Dijkstra algorithm and the proposed CA + PSO algorithm, with 50 experiments performed for each [

28,

29]. The results are shown in

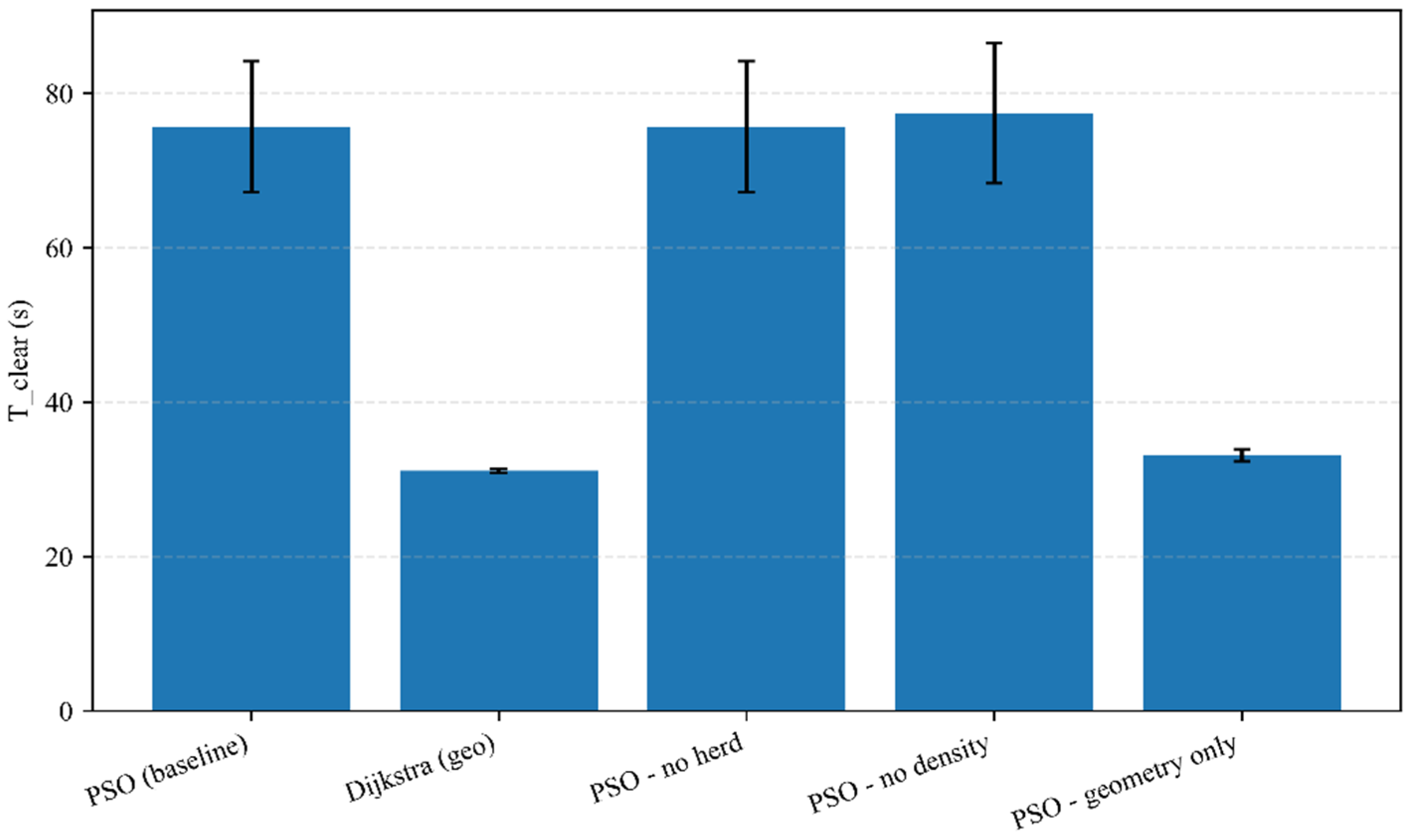

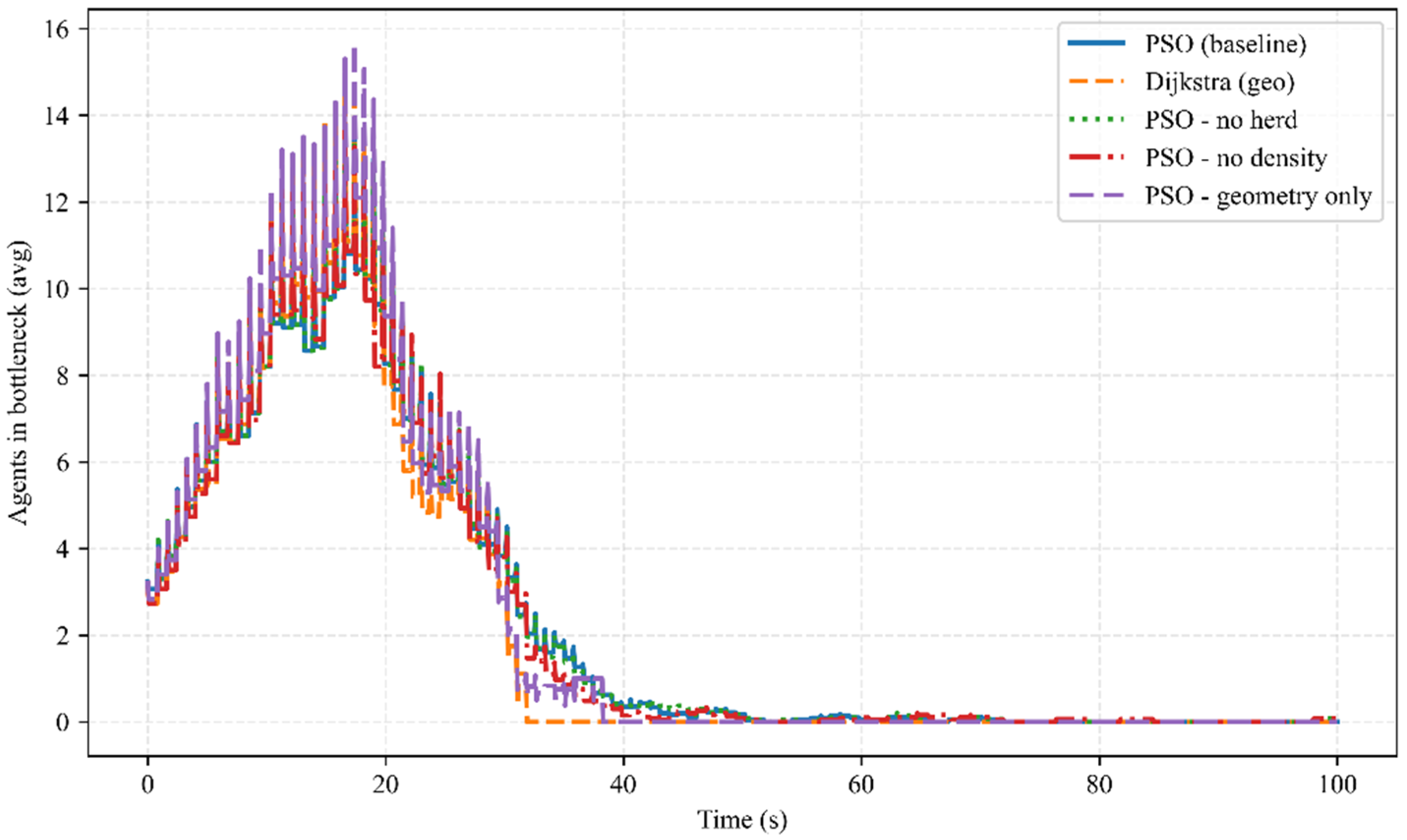

Figure 13 and

Figure 14.

Figure 13 compares the impacts of different baselines/ablation configurations on the total clearance time T_clear. Two geometry-shortest-path-oriented strategies—Dijkstra (geo) and “PSO-geometry only” (micro-objective search with only geometric terms retained)—yield the shortest average T_clear(approximately 30–35 s, with minimal error). In contrast, the PSO series including density and hazard avoidance terms (baseline, no-herd, no-density) show significantly longer overall T_clear and larger variance. This indicates that incorporating density/fire-smoke costs into micro-objectives guides agents to detour and diverge, thereby reducing local congestion and risks, but at the cost of prolonging the system-level clearance time. Conversely, purely pursuing the geometric shortest path can minimize time but may lead to greater pressure on passages. Furthermore, the impact of “removing herd following (no-herd)” or “removing density term (no-density)” on the average time is less significant than that of “removing all environmental fields and retaining only geometry”, implying that geometric terms dominate time efficiency, while behavioral/environmental terms mainly regulate risk and congestion patterns.

Figure 14 shows the curve of the average number of pedestrians at the main bottleneck over time, intuitively revealing the above trade-off mechanism. The two geometry-priority curves (Dijkstra and geometry-only, purple/orange) show higher and sharper peak occupancy (stronger queuing and congestion) around 15–20 s, followed by a rapid decline and approaching zero earlier. In contrast, the PSO variants including density/hazard terms (blue/green/red) show lower and wider peaks, indicating that traffic flow is dispersed to more paths and “smoothed” over time, but the tail is longer, and the overall evacuation ends later. Combined with the two figures, it can be seen that the environmental perception of PSO indeed reduces the peak load and instantaneous congestion risk at bottlenecks, but at the cost of prolonged total clearance time. There is an adjustable strategy space between “minimum time” and “controlled congestion/risk”, and the choice of configuration should be based on the safety constraints and efficiency goals of the application scenario.

3.5. Grid Sensitivity Check of the Algorithm

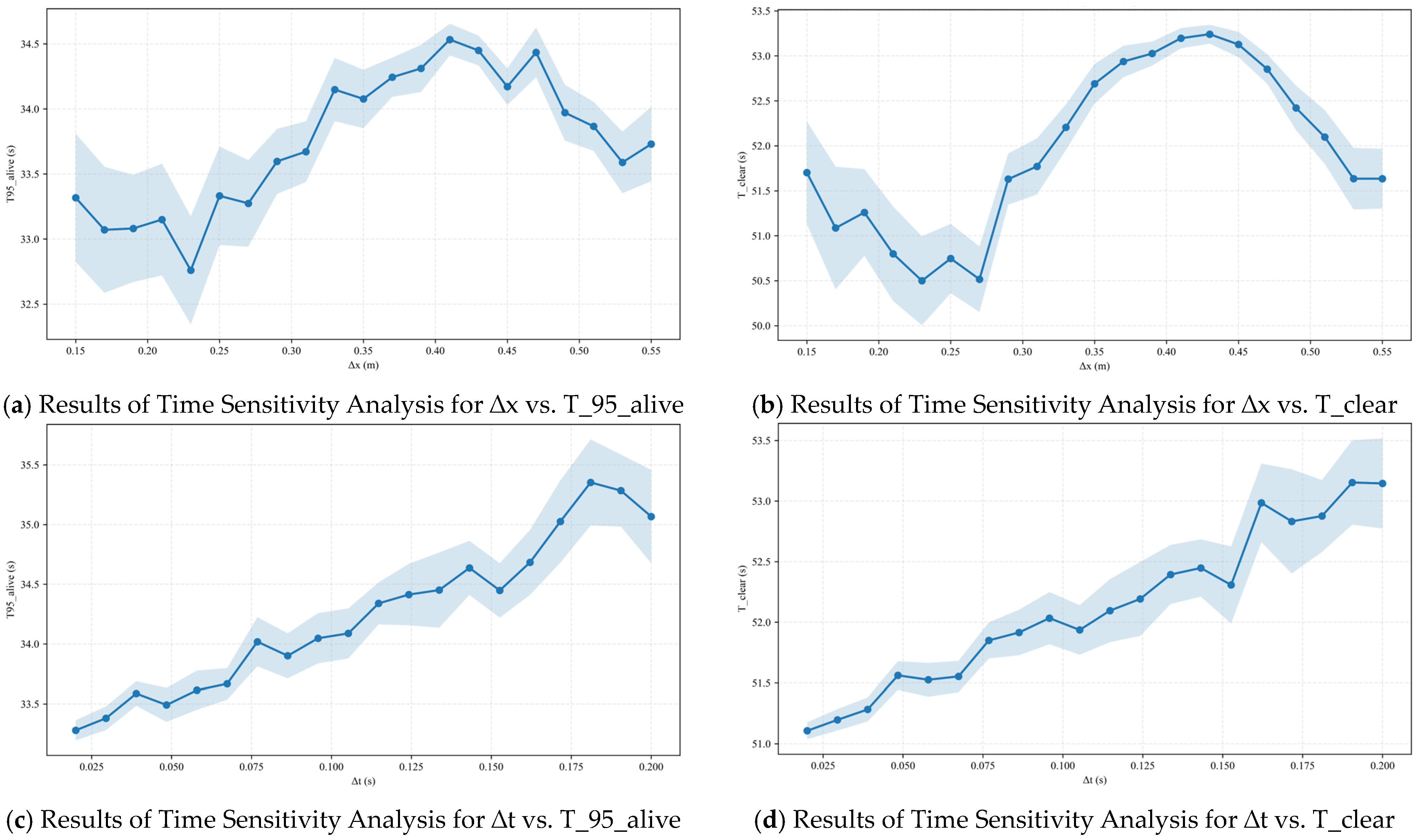

To enable more precise analysis of the algorithm’s results, a sensitivity analysis was performed on the algorithm’s time step and grid size to ensure the accuracy of the model construction. Based on the existing computational results and using the PSO baseline as the reference, the T_clear and T_95_alive times were analyzed, with the results presented in

Figure 15.

For Δx–T95_alive: Under the premise of maintaining geometric invariance and automatic resampling, T95_alive exhibits slow fluctuations as the grid size varies between 0.15 and 0.55 m. The curve reaches its minimum around 0.23–0.27 m and shows a slight peak near 0.41–0.45 m, with a total fluctuation of approximately 1.5–1.6 s. The 95% confidence intervals of each data point overlap substantially, indicating that the differences are of limited statistical significance—i.e., the CA exhibits weak sensitivity to Δx.

For Δx–T_clear: It shares a similar shape to the aforementioned curve, with lower values around 0.23–0.27 m and higher values at 0.41–0.45 m, with a magnitude of approximately 2.5–2.7 s. Similarly, the high degree of overlap in the confidence bands indicates that the effects induced by Δx are second-order effects/discrete resonance rather than systematic biases; thus, selecting Δx ≈ 0.25 m can serve as a robust baseline.

For Δt–T95_alive: When only the internal update time step is refined while the step rhythm remains unchanged, T95_alive shows a basically monotonic increase as Δt rises from 0.02 to 0.20 s. This reflects the numerical viscosity/collisions and delayed fire-smoke propagation caused by coarser time steps, leading to an overestimation of evacuation time.

4. Conclusions and Future Research

A hybrid-characteristic pedestrian evacuation model integrating Cellular Automaton (CA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) micro-objectives is proposed in this study. This model realizes the visualized simulation of pedestrian evacuation dynamics, optimized design of evacuation strategies, and quantitative evaluation of system feasibility and reliability in hazardous field propagation environments, providing technical support for the formulation of emergency evacuation plans and structural optimization of buildings during disasters.

A CA-PSO multi-field coupled evacuation model framework is proposed: Cellular Automaton is used to discretize the evacuation space into a two-dimensional raster; Gaussian kernel estimation is combined to construct a smooth density field for avoiding pedestrian congestion; a hazard field propagation model is established based on the Moore norm and random rounding method; meanwhile, a PSO micro-objective update strategy is adopted to decompose the long-term exit target into local micro-objectives, realizing dynamic optimization of individual evacuation decisions and solving the disconnection between spatial simulation and individual decision-making in traditional models.

An autonomous-hybrid pathfinding mechanism is proposed: by linearly integrating the “autonomous direction toward micro-objectives” and “herd following direction”, and introducing a mixing coefficient and a micro-reward for consistent directions, this mechanism not only ensures the individual’s ability to autonomously perceive and adjust paths based on hazard and density fields but also realizes orderly collaboration at the group level. It avoids path chaos caused by single autonomous decision-making or congestion aggregation caused by single following decision-making, balancing evacuation efficiency and group order.

A multi-dimensional interpretability and robustness evaluation system is proposed: Shapley and Sobol analyses are introduced to quantify the impacts of key parameters on evacuation indicators—identifying PSO_WINDOW_RADIUS as the core influencing factor of T_clear and PSO_LAMBDA_HAZ as the dominant factor of T 95% alive; CDF/PDF distribution analysis and vulnerability curves are used to evaluate the system robustness under the exit-closed scenario, revealing that closing one exit can suppress the long-tail risk of T_clear; combined with ablation experiments, the key role of coupling between density and hazard fields in “reducing bottleneck congestion and balancing efficiency and risk” is verified.

Finally, the model shows good practicality in the test scenario of an underground shopping mall in Shaanxi Province (54 m in length, 43 m in width): in the test mall scenario (54 m × 43 m) with 60 pedestrians, the geometry-only baseline yields an average clearance time of ≈33 s (range ≈ 30–35 s), while hazard-/density-aware strategies produce slightly longer T_clear but reduce peak bottleneck congestion by 20–30%. Meanwhile, the priority of parameter regulation is clarified through interpretability analysis, providing clear basis for parameter debugging in practical applications. Future research can be expanded in three directions: first, expanding to multi-disaster scenarios and adding coupling mechanisms between different disaster types; second, incorporating pedestrian heterogeneity characteristics to improve the model’s adaptability to real crowds; third, combining real-time perception data to construct a closed-loop control system of “real-time data input–dynamic model adjustment–on-site guidance output”, promoting the model from simulation analysis to dynamic emergency guidance in practical buildings.