Abstract

This study evaluates crushed bamboo as a coarse aggregate for structural–thermal wall composites, comparing its performance against mixes with wood sawdust and rice husk. Crushed bamboo was used in both smooth and surface-roughened conditions, where particle morphology and surface features were characterized by SEM and AFM methods. The roughened bamboo aggregate exhibited greater surface roughness, thereby improving interfacial adhesion with cement. Surface roughening increased 28-day compressive strength by ~39–44% relative to smooth particles. Incorporating fine plant-based fillers into cement–bamboo composites increased their compressive strength by ~33–75% and reduced thermal conductivity by ~12–18%, compared with the analogues without fine particles. Water-absorption tests on bamboo aggregate showed rapid uptake in the first 24 h (43–45%) and saturation after 7 days of ~65–70%, values lower than typical wood by-products, thereby helping to limit mix water demand. Findings indicate that crushed, surface-roughened bamboo, especially with fine bio-fillers, can produce sustainable wall materials with a strong balance between strength and insulation.

1. Introduction

At present, the scope of bamboo applications as a raw material has expanded significantly across various industrial sectors due to its unique properties and rapid renewability. Crushed bamboo can serve as an alternative to wood by-products such as sawdust, shavings, or chips. It is a rapidly renewable raw material widely available in Asia, Africa, and both North and South America, with a growth rate of up to 50 cm per day. Scientific research and technological advances have enabled the integration of bamboo into industrial products where its use was previously considered unlikely. For example, bamboo fibres and stems are now employed as substitutes for plastics [1], incorporated into formulations for 3D printing [2], and used in asphalt production [3,4], cardboard manufacturing [5], sorbents [6], composite materials [7], and hygiene products [8]. In addition, laboratory studies are actively investigating the thermal and mechanical properties of bamboo stems and fibres [9,10].

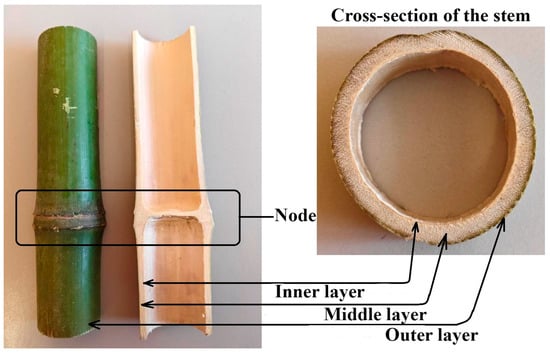

A review of available data on the structure of bamboo shows that, in its cross-section, the stem consists of three layers: outer, middle, and inner (Figure 1). The outer protective layer contains a series of cells elongated along the circumference of the stem, characterized by relatively thick walls, and is covered externally with a waxy coating. The inner layer comprises one to two rows of similarly elongated cells, but with comparatively thinner walls [11]. The thickest, middle layer consists of parenchymal cells interspersed with vascular–fibrous bundles, which appear as dark rhomboid structures in the cross-section.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal and transverse (cross-) sections of the bamboo stem.

One of the most promising fields for the utilization of bamboo fibres and stems is the construction industry. Bamboo shows particular potential for the production of insulating and wall materials, as demonstrated in several studies [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. To reduce shrinkage and enhance mechanical strength, it has been proposed to use bamboo fibres together with steel fibres in the production of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) [12,13].

A study [14] reported that the thermal conductivity coefficient of concrete reinforced with bamboo fibres decreased by 68.8% compared with conventional concrete. The results presented in [15,16] showed that bamboo fibres effectively reduced crack propagation and improved the load-bearing capacity of reinforced concrete beams. Moreover, concrete reinforced with bamboo fibres pretreated with calcium hydroxide exhibited significantly improved water resistance [17]. Bamboo fibres have also been incorporated into clay-based geopolymer composites in amounts of 1–3%, where heat curing at 70–120 °C increased composite strength by 10% [18]. In [19], alkali-treated bamboo fibres were added to lightweight concrete mixes at 30–50% of the cement mass. The results demonstrated that increasing fibre content reduced the thermal conductivity by 70%, down to 0.502 W/(m·K).

In another study [20], a technology was developed for the production of panels using leather fibre (LF) and semi-liquid bamboo fibre (SLB), resulting in products with a thermal conductivity coefficient of 0.0502 W/(m·K) and a sound transmission loss of 25–45 dB in the frequency range of 500–14,000 Hz.

Under the hot climate conditions of Indonesia, researchers [21] conducted field tests on residential buildings constructed with bamboo panels. The panels were composed of vertically arranged bamboo stems placed tightly together, with coconut oil poured into the hollow cavities of the stems. These wall panels served as load-bearing elements of the buildings while maintaining indoor temperatures with a variation of only about 1 °C between day and night.

This study investigates the feasibility of using crushed bamboo as a coarse aggregate in cement-based composites to produce structural wall materials with improved insulation performance. The aim of this research was to develop and validate a technological solution for improving the adhesion between bamboo and the cementitious matrix by using controlled surface roughness on the naturally smooth bamboo stem, thereby enhancing bonding and overall composite performance. Drawing on analogies with wood-chip concrete (arbolite) [22,23,24] and prior research on bamboo in construction, we hypothesize that crushed bamboo can reduce thermal conductivity while maintaining adequate mechanical strength when properly combined with cement and auxiliary fillers derived from wood-based by-products. The novelty of this study lies in the systematic use, head-to-head comparison, and SEM/AFM characterization of crushed bamboo aggregates with smooth versus surface-roughened textures, isolating aggregate surface texture as a processing parameter that significantly affects composite properties. To validate this hypothesis, a comprehensive experimental programme was designed, including microstructural, physical–mechanical, and thermal characterization of bamboo-based wall composites, together with a comparative evaluation against composites incorporating other wood-based by-products such as rice husk and wood sawdust.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The quantitative composition of the main chemical constituents of the studied bamboo is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Principal constituents of bamboo.

The raw material consisted of dry bamboo stems with diameters ranging from 10 to 25 mm. To impart roughness to the naturally smooth surface, the stems were first treated with abrasive wheels using an angle grinder. The prepared stems were then cut into cylinders 15 and 25 mm in length using a band saw. These cylinders were placed horizontally on a support and crushed with a low-power press, producing bamboo aggregate in the form of elongated plates with lengths of 15 mm (fine fraction) and 25 mm (coarse fraction) and widths of 3–10 mm (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Coarse aggregate from crushed bamboo.

The studied rice husk consists of convex thin plates with lengths of 5–7 mm and was used without additional processing. The composition of the rice husk is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Principal constituents of rice husk.

Fine sawdust with particle lengths of 2–4 mm, obtained from sawing softwood with a band saw, was used in the study. The material composition of the sawdust is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Principal constituents of sawdust.

For the production of wall materials, CEM I 42.5R cement conforming to the EN 197-1:2011 standard [25] was used, supplied by the manufacturer “Krichevtsementnoshifer”. The mineralogical composition of the cement shows large amounts of C3S (65.9%), C2S (16.8%), C4AF (10.9%), and C3A (6.4%). The chemical composition of the cement is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Chemical composition of the cement.

Technological parameters of the cement used in this study are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Technological characteristics of the cement.

2.2. Methods

The chemical composition of the cement was determined using X-ray fluorescence analysis (Rigaku ZSX Primus IV, Japan). The mineralogical composition was identified using X-ray diffraction (DRON-7 diffractometer, Russia). Microscopic analysis of the structure and the surface of the studied materials was carried out using a JSM-5610 LV scanning electron microscope (SEM, Japan) and an NT-206 atomic force microscope (AFM, Belarus). Data from the atomic force microscope were processed using the dedicated control software SurfaceScan (ver. 1.0) and the image processing programmes SurfaceView (ver. 1.0) and SurfaceXplorer (ver. 1.0).

The main physical and mechanical parameters of the wall material, such as density, compressive strength, and water absorption of crushed bamboo particles, were determined in accordance with the procedure described in EN 1520:2011 standard [26]. Compressive strength tests of the cement-based wall materials containing bamboo, wood sawdust, and rice husk were performed on a Matest C041N (Italy) hydraulic press. The testing machine complies with ASTM C39 [27] and has a maximum loading capacity of 1500 kN. The allowable relative error in load measurement is ±1%. The load measurement device has a resolution of 0.001 kN. The loading rate was maintained at 0.6 ± 0.2 MPa/s, specified for lightweight concretes. Compressive strength tests were performed on five cube specimens with an edge length of 150 mm at the age of 28 days.

The thermal conductivity of the investigated materials was measured according to EN 12667:2001 standard [28]. The measurements were carried out on plate specimens with dimensions of 250 × 250 × 50 mm, which were placed in an ITP-MG4-250 (Russia) apparatus to determine the thermal conductivity coefficient. The specimens were dried to constant mass in a drying chamber at 50 °C. After drying, they were placed in the ITP-MG4-250 apparatus to determine the thermal conductivity coefficient λ25. During the measurement, the temperature of the hot plate was maintained at 40 °C, while the cold plate was kept at 10 °C. Tests were performed on five specimens for each composition.

2.3. Preparation of Experimental Wall Samples

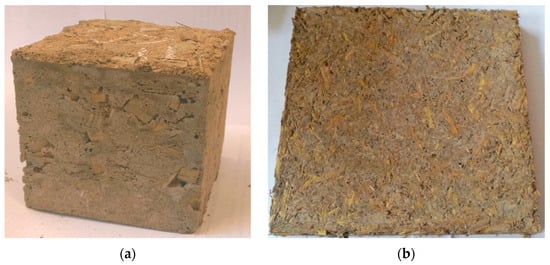

To demonstrate the effectiveness of bamboo with both rough and smooth textures as an aggregate for wall materials with effective insulation and mechanical performance, cubic specimens were produced for mechanical characterization (Figure 3a), and plate specimens were prepared for thermal conductivity testing (Figure 3b). The specimens were moulded using a Matest C041N (Italy) hydraulic press under a pressure of 0.7–0.8 MPa and kept in the moulds for 24 h. After demolding, they were stored under natural conditions at a temperature of 20 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 60–65% until the age of 28 days. The selected relative humidity of 60–65% for specimens made with cement and plant-based aggregates was intended to reduce moisture-related deformation of the aggregate and to prevent mould growth during strength development. At 28 days, the specimens were dried in an oven at 40–50 °C to a constant mass (i.e., to an oven-dry condition).

Figure 3.

Examples of produced building materials: (a) cube made of bamboo and wood sawdust; (b) panel made of bamboo and rice husk.

A series of mix-design studies were conducted, including the selection and preparation of aggregates of specific fractions (Table 6). The main physico-mechanical properties of the resulting composites were then evaluated using five specimens of each type (cubes for mechanical testing and plates for thermal conductivity measurements).

Table 6.

Compositions of experimental materials.

Crushed bamboo was used as the coarse aggregate in the experimental mixtures, while the voids within the bamboo framework were filled with wood sawdust or rice husk as fine fillers. Cement was used as the binder, and aluminum sulphate (Al2(SO4)3) was added at 2% of the cement mass as a hardening accelerator. Such accelerators are widely used to counteract the inhibitory effects of water-soluble sugars and extractives naturally present in organic aggregates, including bamboo and wood sawdust [29,30,31,32,33]. The selected dosage follows the previous findings of Yagubkin et al. [23], who developed a dedicated methodology for assessing accelerator performance in wood–cement systems. Their study demonstrated that a 2% addition of aluminum sulphate improves the early compressive strength of cement paste by approximately 22–23% compared to the additive-free composition, confirming its effectiveness in neutralizing the adverse impact of sucrose, glucose, hemicellulose derivatives, and other extractives released from plant-based fillers. At this concentration, aluminum sulphate ensures rapid setting and early hydration while avoiding the negative effects associated with both insufficient and excessive dosing.

Initially, the required amount of water for the experimental mixes was selected based on published formulations of wood-chip concrete (arbolite), where a water-to-cement ratio of 1.1 is typically reported [23,29,30,31,32,33]. Subsequently, the optimal water-to-cement ratio for each mix was determined experimentally, taking into account the mixing sequence, the water absorption characteristics of the aggregates, and the consistency needed to ensure uniform dispersion of the cement paste. The amount of water strongly depended not only on the type of natural components used (bamboo, rice husk, wood sawdust) but also on the fraction of bamboo employed (coarse or fine). The selected water-to-cement ratios for the different experimental mixes are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Water-to-cement ratio of the experimental mixes.

To ensure uniform dispersion of the lightweight bio-aggregates, specific mixing procedures were applied for each type of natural filler. Despite the relatively low density of bamboo aggregates (approximately 500 kg/m3), its mechanical characteristics are comparable to those of hardwood species, with a hardness coefficient of up to 4, compressive strength reaching 60 MPa, and tensile strength up to 100 MPa [24]. These properties contribute to its stable behaviour during mixing, preventing fragmentation and supporting uniform distribution within the cementitious matrix. For bamboo-only (control) mixes, cement pastes with W/C = 0.57 (coarse fraction) and 0.61 (fine fraction) were first prepared, producing a viscous paste capable of preventing particle flotation. During mixing, the viscous cement matrix coated the bamboo pieces uniformly, and no upward migration of the low-density particles was observed during casting. In mixtures containing both bamboo and wood sawdust, a more fluid cement slurry (W/C = 1.22–1.29) was prepared initially; the sawdust was mixed with this slurry to allow partial water absorption, yielding a cohesive, viscous mass with evenly distributed sawdust. Crushed bamboo was then introduced and dispersed uniformly within this thickened matrix. A similar approach was used for bamboo–rice husk mixtures, though higher W/C ratios (0.77–0.80) were required due to the high absorptivity of rice husk. In this case, the cement paste was first blended with the rice husk before adding the bamboo aggregate to ensure uniform distribution of both fillers in the final composite.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructural Analysis of Bamboo by Electron and Atomic Force Microscopy

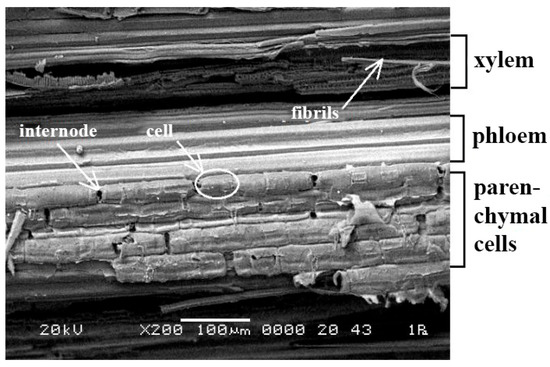

Microscopic analysis of crushed bamboo was conducted to evaluate its effect on the strength and thermal properties of the wall material. In the longitudinal section (Figure 4), regions of parenchymal cells measuring 50–70 µm in length are clearly visible. Within the internodes, these cell cavities are oriented along the axial direction. All structural components of bamboo interact with each other and collectively contribute to reinforcing and strengthening the material. The walls of bamboo fibres exhibit a degree of plasticity, which increases the material’s resistance to failure under external loading.

Figure 4.

Surface morphology of a longitudinal bamboo section (200× magnification).

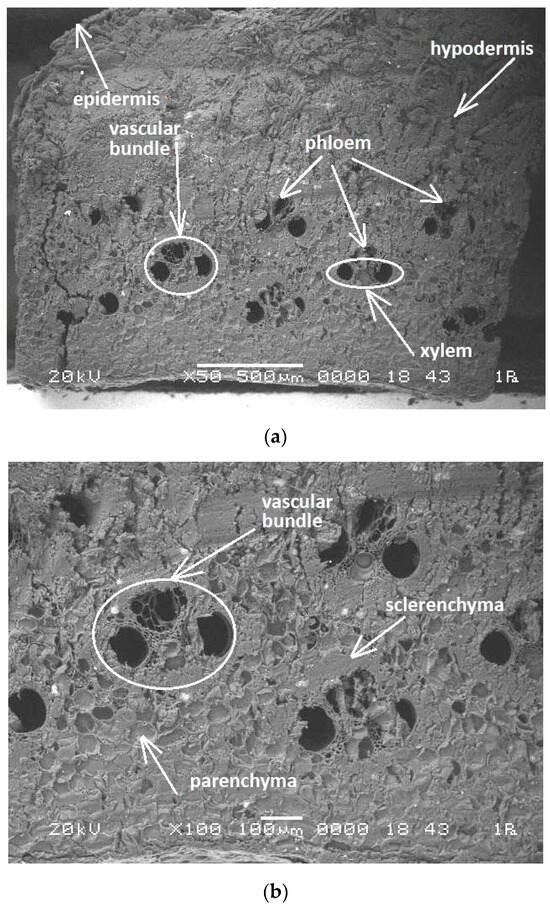

The vascular bundles in the transverse (cross-) section of bamboo (Figure 5a,b) are densely packed near the hypodermis and therefore only weakly distinguishable. Each bundle consists of two regions: the xylem and the phloem. The xylem contains two vessels (annular and spiral) with diameters of 50–70 µm, while the phloem includes a cavity intended for the transport of nutrients. The vessels and the cavity are arranged in a characteristic “Y” shape and are surrounded by a continuous sclerenchyma cell structure. Toward the outer region, the vessels become elliptical, whereas toward the centre they appear more rounded. The high strength of bamboo as a construction material is ensured by the abundance of fibres and their dense packing within the hypodermis [34].

Figure 5.

Surface morphology of a bamboo cross-section: (a) 50× magnification; (b) 100× magnification.

Parenchymal cells are predominantly pentagonal in cross-section and form a honeycomb-like structure. Their size in the transverse direction ranges from 20 to 60 µm. Thus, these cells can be regarded as units resembling regular pentagonal prisms. The dimensions of these prisms are comparable to the cellular structure of expanded polystyrene, which hinders the transfer of heat or cold and therefore provides bamboo with its insulating properties. Each wall of a bamboo fibre cell exhibits a unique multilayered configuration, in which every layer is reinforced with cellulose fibrils oriented at different angles. This arrangement defines the mechanical performance of the fibres and contributes to the overall strength of the bamboo matrix.

SEM results of both transverse and longitudinal sections further show that the dense microstructure of fibres, particularly in the hypodermis region, results in a relatively high density of bamboo and correspondingly high compressive strength, enabling its use as a coarse aggregate in wall materials.

For cement-based composites, a critical factor is the adhesion between the cement matrix and the aggregate. Cement inherently exhibits relatively weak bonding with many materials, particularly those with smooth surfaces [35,36]. To ensure adequate adhesion with bamboo aggregate, the texture of particles obtained from crushed bamboo was examined along both the outer and lateral surfaces.

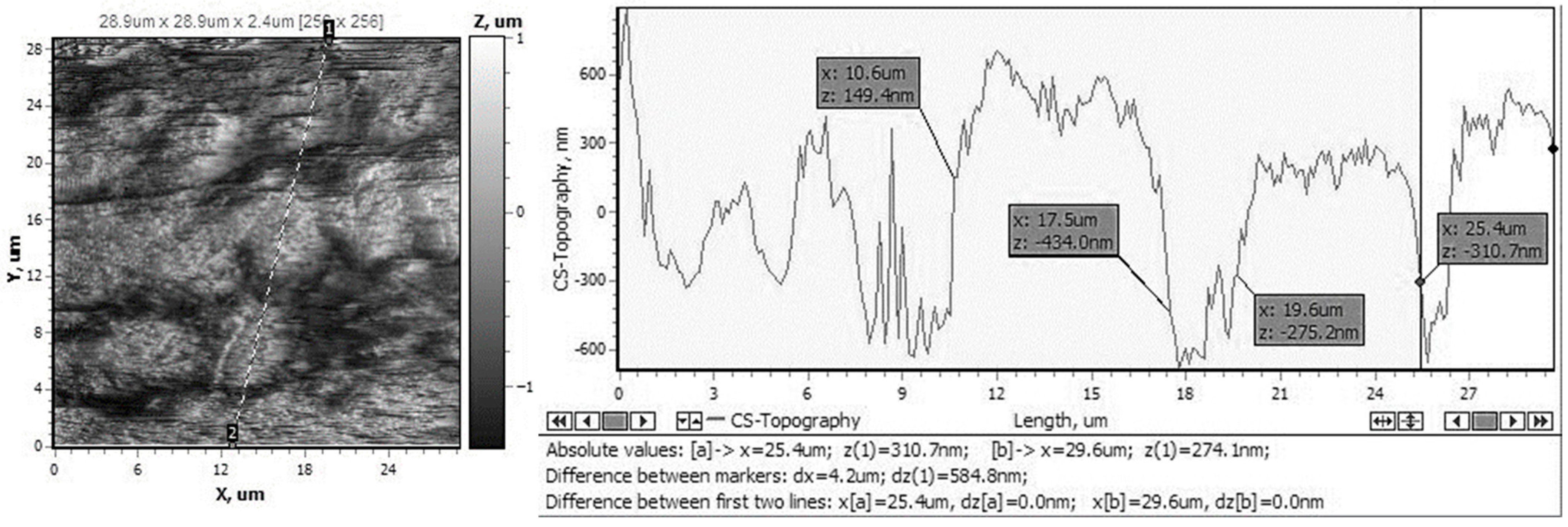

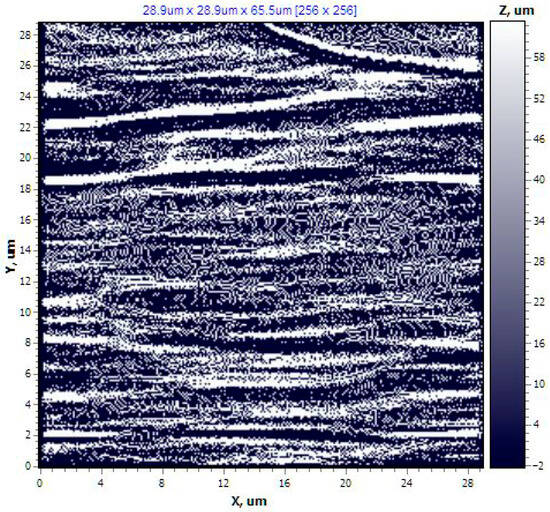

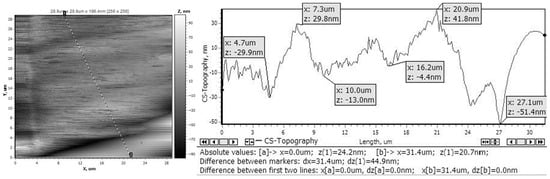

Application of the Laplacian filter for improved visualization revealed a distinctly fibrous structure on the transverse section of bamboo. The 2D scan image (Figure 6) shows the fibrous arrangement of stem rings without significant height variations. The average surface roughness was measured as Ra = 69.4 nm, while the root-mean-square roughness reached Rq = 84.1 nm.

Figure 6.

Surface of a bamboo cross-section (29 × 29 µm).

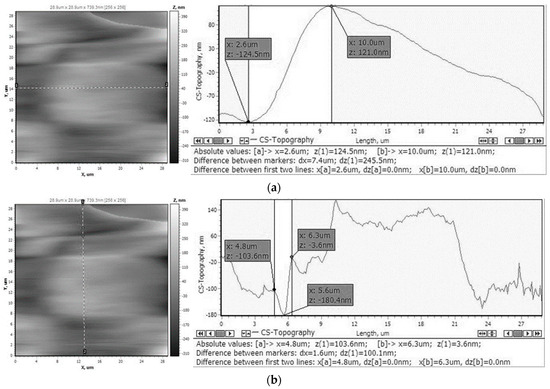

Figure 7a presents the surface profile of the transverse section of bamboo along horizontal vector 1–2, showing a relief variation of 245.5 nm. The highlighted elevation in the profile of the light-coloured region (Figure 7a) corresponds to a fragment of the fibrous bamboo structure at coordinates X = 16–23 nm and Y = 14 nm.

Figure 7.

Surface profile of a cross-sectional bamboo cut: (a) along horizontal scan vector 1–2; (b) along vertical scan vector 1–2.

The surface profile of the transverse section of bamboo along vertical vector 1–2 is shown in Figure 7b. As can be seen, the bamboo structure along this vector exhibits a more complex surface with higher relief and roughness, further confirming its fibrous nature. The maximum amplitude reaches 320.4 nm. On the transverse section, the action of sawing or crushing tools causes partial destruction of the fibrous structure, resulting in a pronounced surface relief that enhances adhesion to the cementitious matrix.

When bamboo is fractured along the stem, the rupture occurs along the fibre contact boundaries, leading to discontinuities in the fibre surface. This is evidenced by frequent and sharp fluctuations along the vertical vector, i.e., across the fibres (Figure 7b), and is further confirmed by SEM (Figure 4).

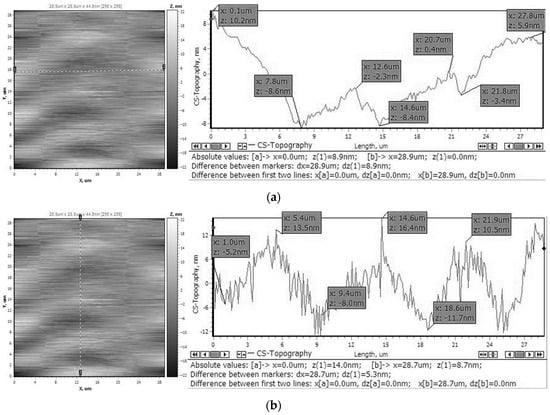

Figure 8a,b show the surface profiles of bamboo along horizontal and vertical vectors 1–2 of the longitudinal section through the phloem wall, with height variations of up to 28.1 nm and 428.8 nm, respectively. In other regions, including parenchymal cells and xylem, the AFM method could not be applied due to the high complexity of the relief. In these areas, pronounced height variations of 5–30 µm were observed, which are expected to further improve the adhesion between bamboo particles and the cementitious binder.

Figure 8.

Surface profile of a longitudinal bamboo section: (a) along horizontal scan vector 1–2; (b) along vertical scan vector 1–2.

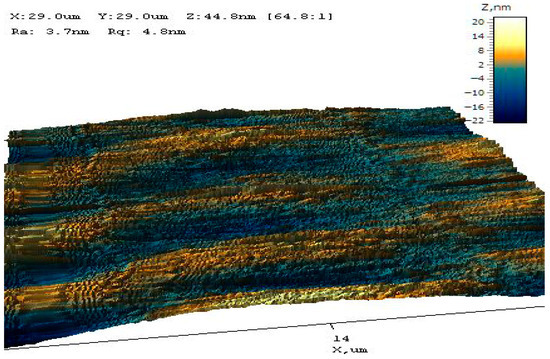

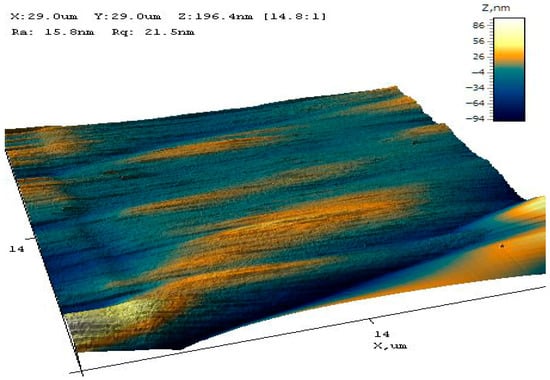

The 3D image of the longitudinal bamboo section in the phloem region is presented in Figure 9. The structure exhibits a relief surface with a pronounced orientation, resulting from the longitudinal alignment of fibres. The maximum height variation in the examined area reaches 42 nm.

Figure 9.

Three-dimensional scan image of a longitudinal bamboo section (29 × 29 µm).

Thus, the rough relief textures of the transverse and longitudinal faces of crushed bamboo particles enhance adhesion between the aggregate and the binder, thereby contributing to increased compressive strength of the composite material as a whole.

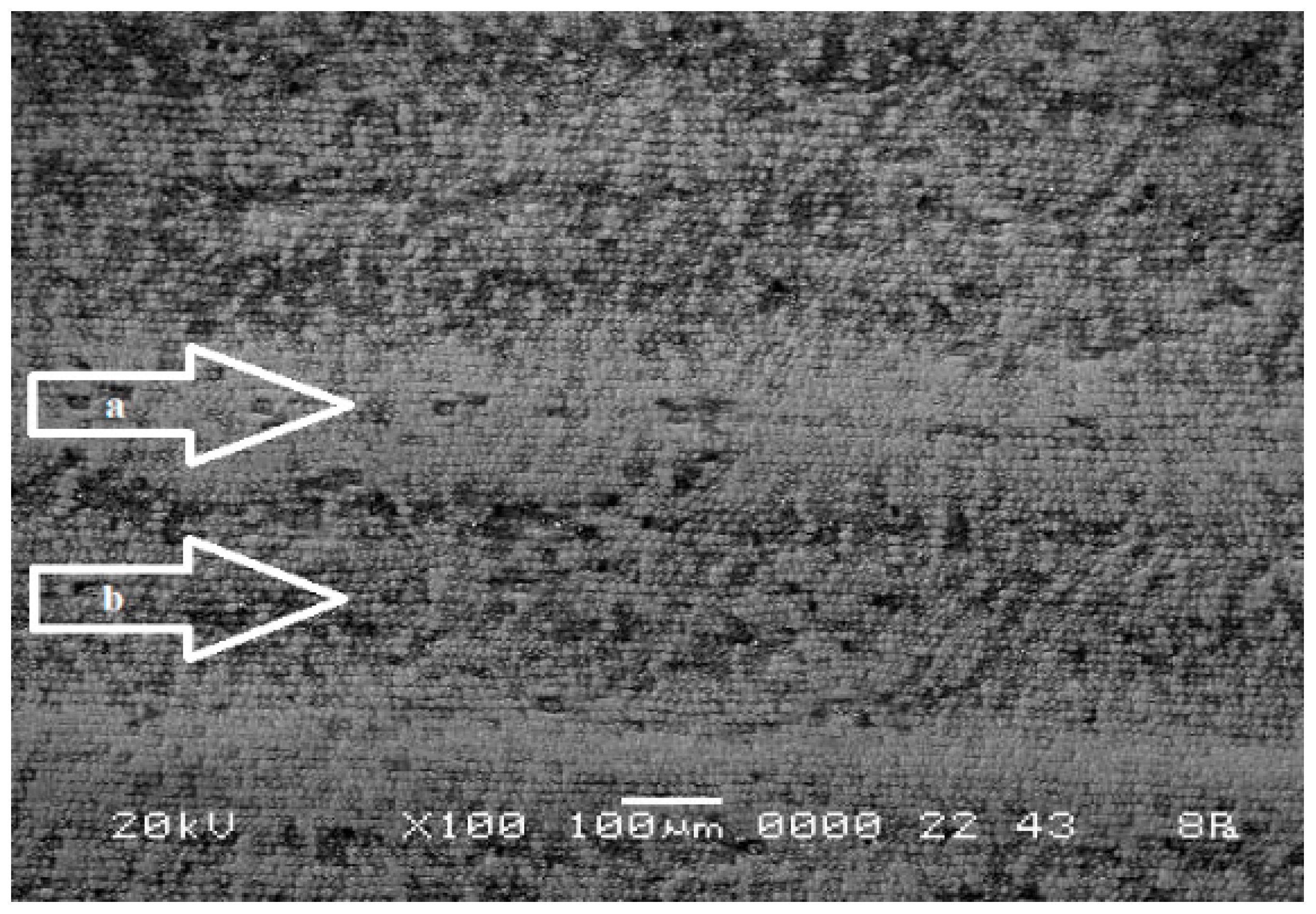

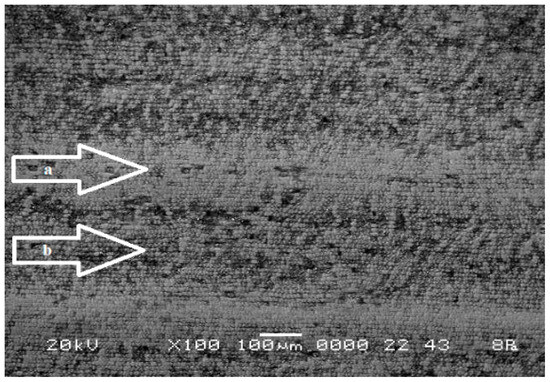

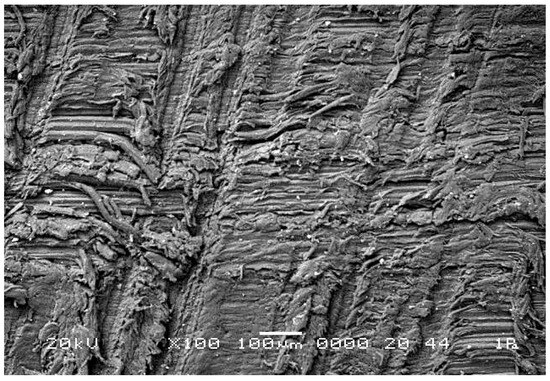

3.2. Surface Texture Analysis of Bamboo Stem Before and After Mechanical Treatment

Following the same procedure described in Section 3.1, the surface texture of the outer bamboo stem was also examined. SEM revealed that the outer covering layer is an epidermis composed of fibres bound with lignin and characterized by relatively thick cell walls (Figure 10). These fibres are densely packed around the circumference of the stem, and their quantity is greater compared with the inner regions. The outer surface is also covered with a waxy layer. Furthermore, in region “a” the fibres are arranged more densely than in region “b,” forming an almost smooth surface. The dense packing of fibres in region “a” further reduces adhesion with the cement matrix.

Figure 10.

Surface morphology of the smooth outer surface of bamboo (100× magnification).

The surface analysis along the vertical axis (Figure 11) shows that the relief amplitude reaches 93.2 nm, while the average height variation ranges between 40 and 50 nm, confirming the formation of a texture that is close to a smooth surface.

Figure 11.

Surface profile of bamboo with the outer covering layer along vertical scan vector 1–2.

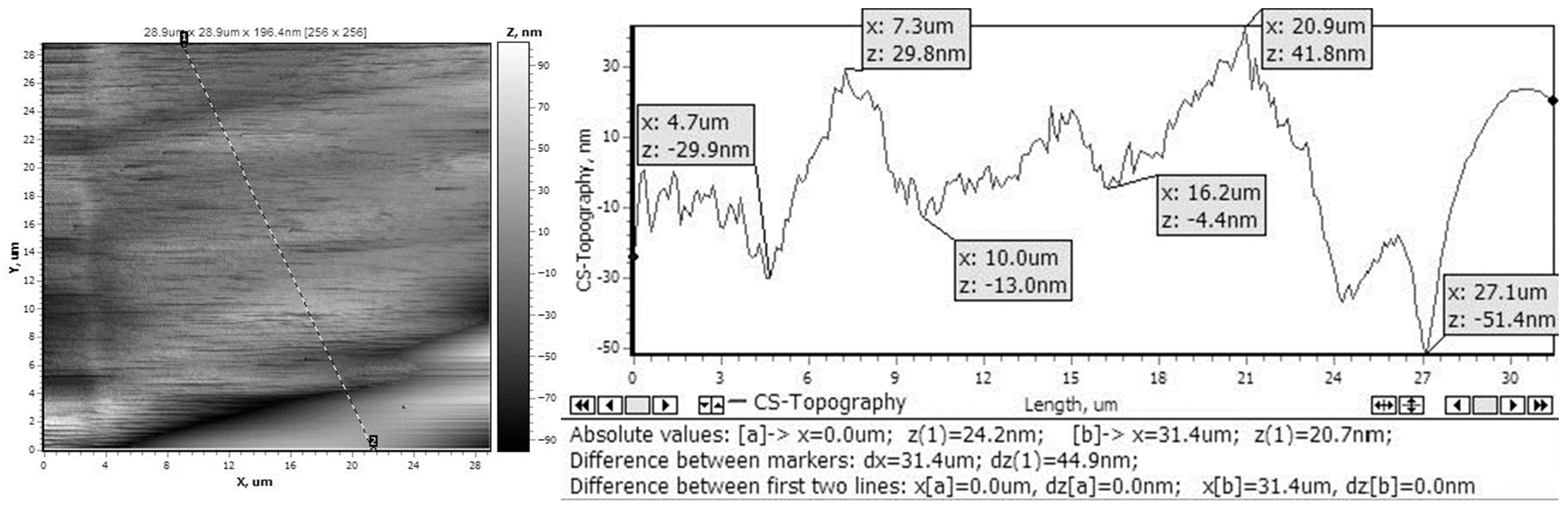

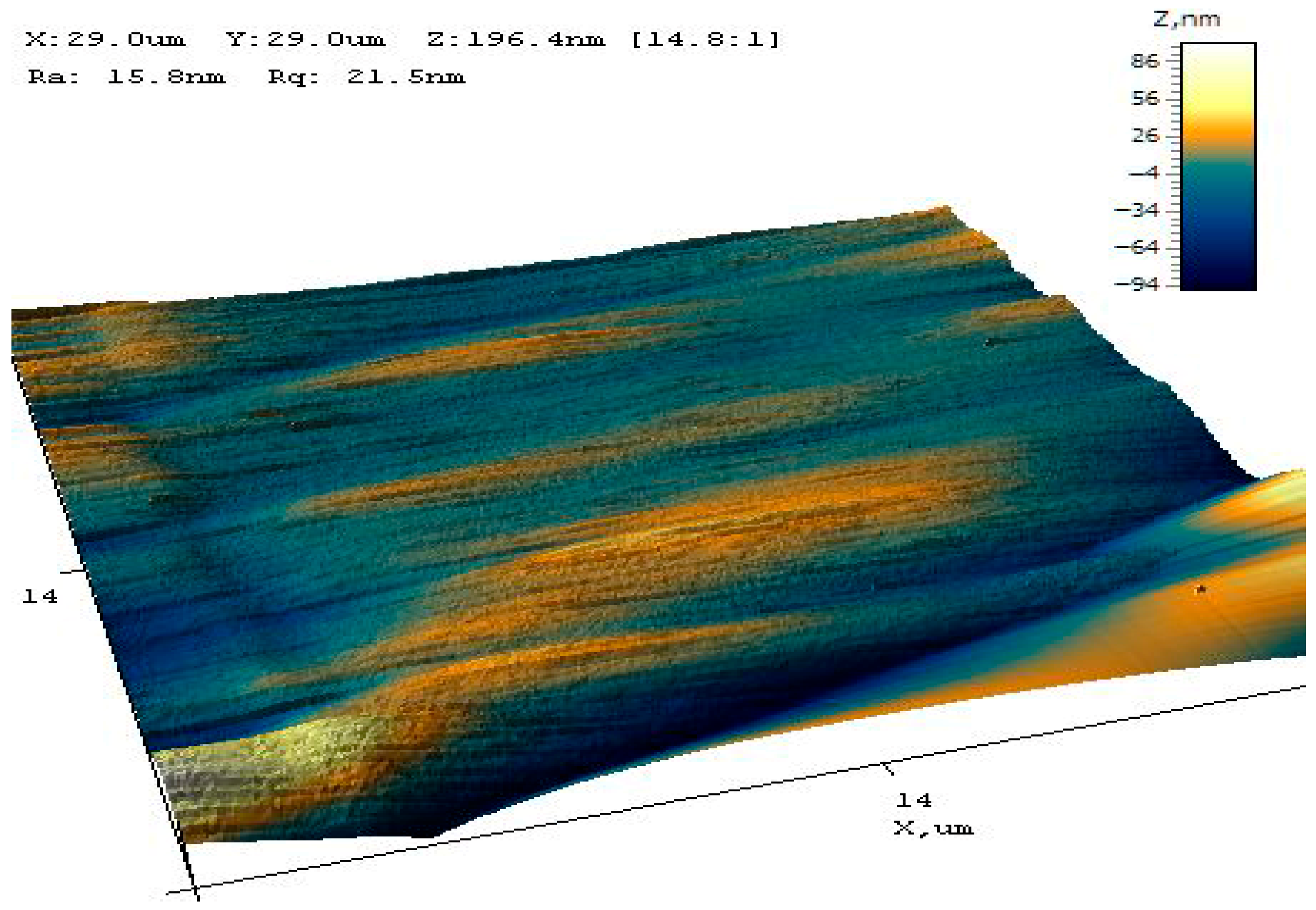

The results of the 3D atomic force microscopy analysis likewise indicate a low-relief texture on the outer surface of the bamboo stem (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Three-dimensional-scan image of bamboo with the outer covering layer.

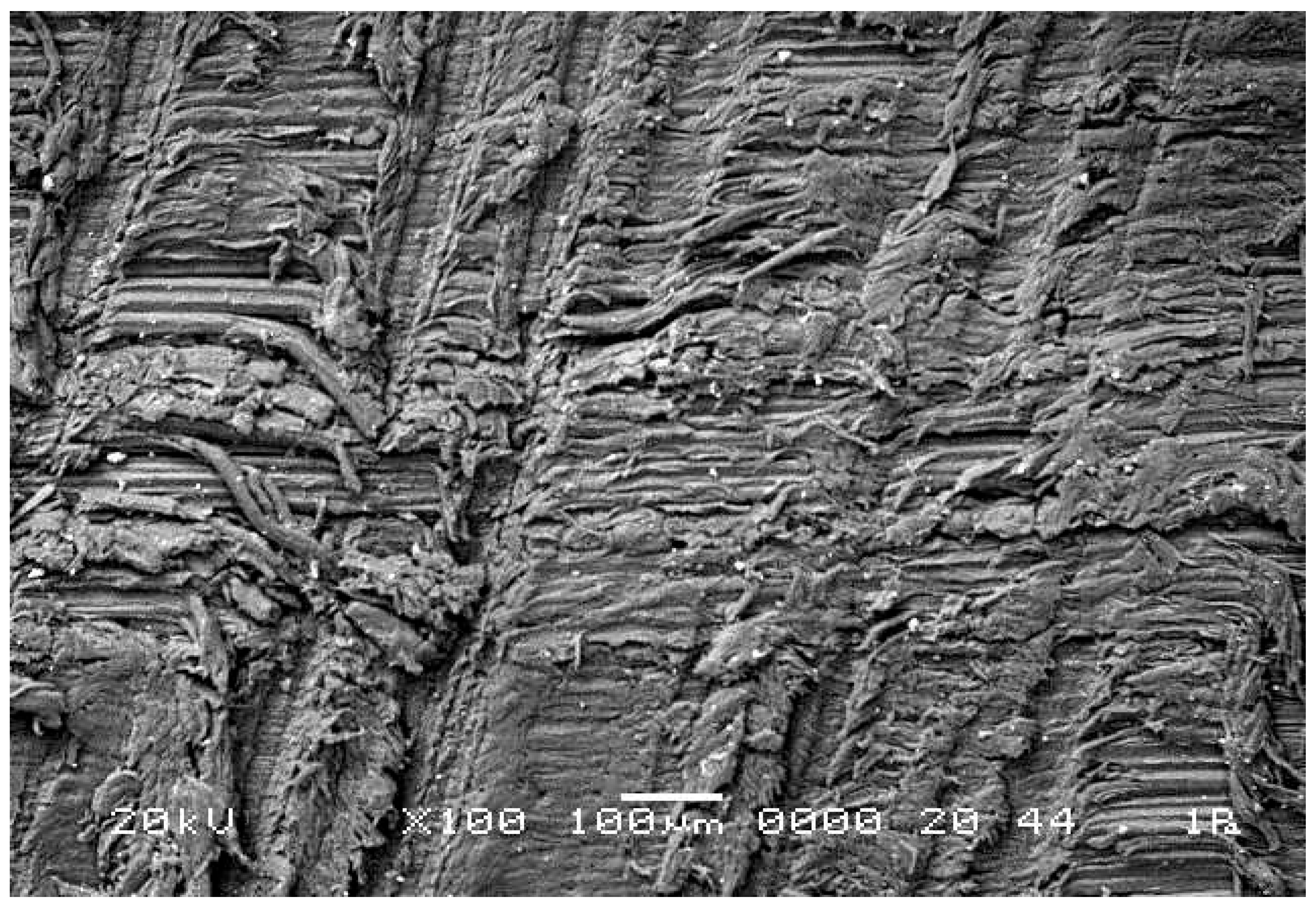

To increase surface roughness, the outer coating layer with its waxy film was removed using sandpaper abrasion, producing an exposed fibrous structure with a disrupted epidermal morphology. The surface micrograph (Figure 13) clearly shows a pronounced grooved relief with numerous peaks and valleys, resulting from the removal of the surface layer and the disruption of fibre integrity. This treatment enhances the adhesion of bamboo, when used as a coarse aggregate, to the cement matrix, which in turn positively affects the strength characteristics of the wall material.

Figure 13.

Surface morphology of the rough bamboo (100× magnification).

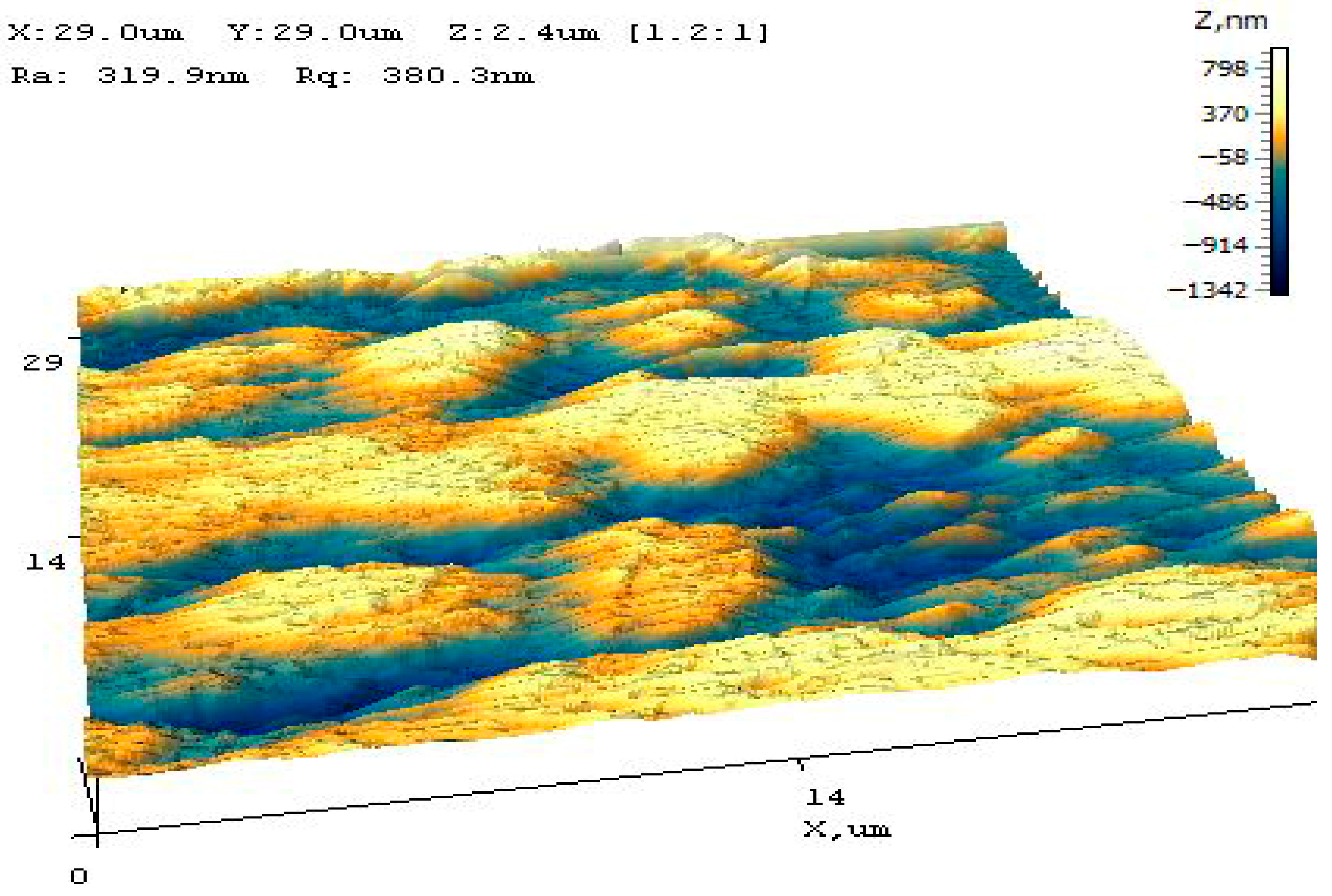

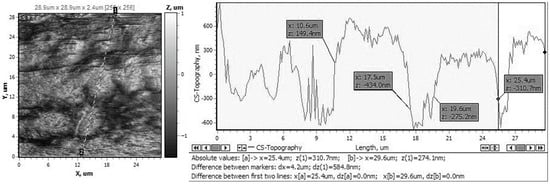

The bamboo stem surface after abrasive treatment was also analyzed by the AFM method. Figure 14 shows the surface profile along vertical vector 1–2, revealing a grooved texture with ridge heights of up to 1550 nm (1.55 µm).

Figure 14.

Surface profile of bamboo with the removed outer covering layer along vertical scan vector 1–2.

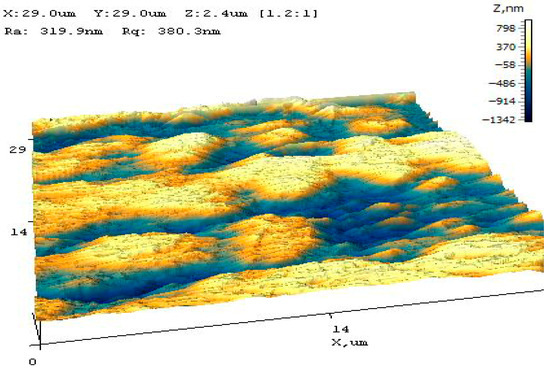

The 3D image of the surface fragment (Figure 15) clearly demonstrates the presence of grooves formed after abrasive treatment, and the accompanying scale indicates that the maximum surface height variation in the examined area reaches 2140 nm (2.14 µm).

Figure 15.

Three-dimensional image of a bamboo surface after removal of the outer coating layer.

Analysis of the obtained results highlights that the outer bamboo layer is covered with a waxy film, which negatively affects adhesion to the cement matrix. Abrasive treatment effectively removes this waxy coating, thereby enhancing the bonding of the binder to the aggregate. Moreover, the removal of the outer layer increases the surface height variation by a factor of 18, producing a significantly rougher texture that is expected to improve interfacial strength between bamboo and cement. As a result of this treatment, the smooth external layer is partially removed, exposing a structure of fibres damaged by the abrasive, which further increases surface roughness and promotes stronger adhesion of the binder to the aggregate. To validate this assumption, a series of experiments were carried out to design structural–thermal insulation composites incorporating crushed bamboo.

3.3. Characterization of Bamboo-Based Wall Materials

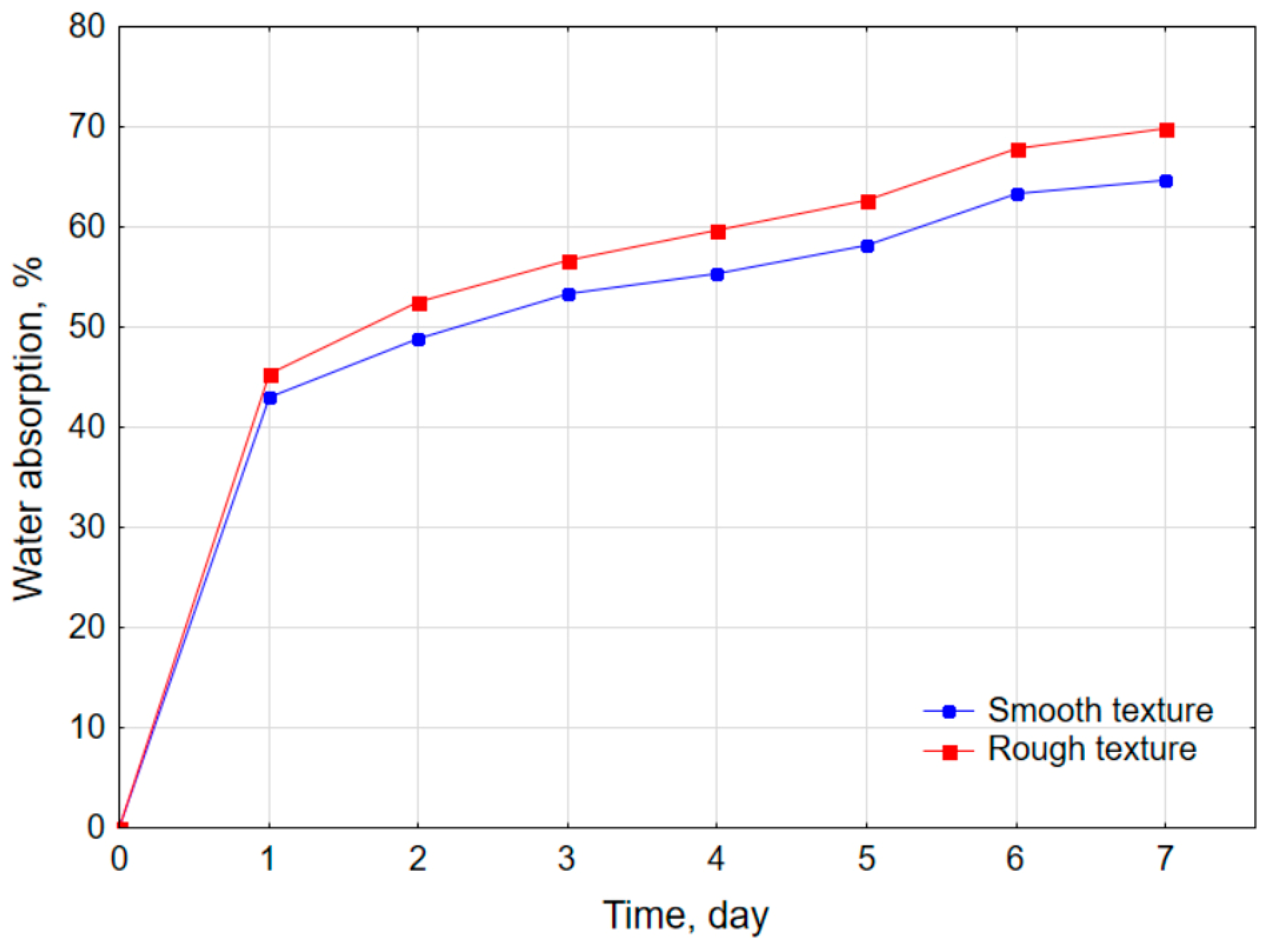

Before evaluating the physical–mechanical properties of the bamboo-based wall materials, an investigation of the water absorption of crushed bamboo with smooth and roughened surface textures was carried out, in order to assess its potential as a coarse aggregate for wall block production. Table 8 presents the bamboo’s water absorption with both smooth and rough texture.

Table 8.

Water absorption of bamboo depending on immersion time.

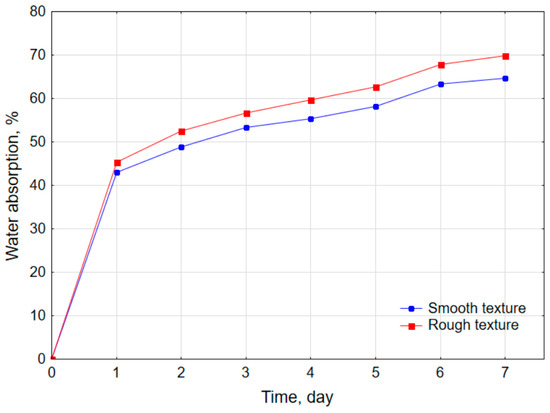

The kinetics of bamboo water absorption are presented in Figure 16. The results indicate that the most intensive increase in water uptake, by 43–45.3%, occurs within the first 24 h of exposure to moisture. Beyond this period, the absorption rate decreases significantly, with an additional increase of 50–54% over the following six days. After seven days, the water absorption reached 64.7% for smooth bamboo and 69.9% for roughened bamboo. The absorption capacity of roughened bamboo was only slightly higher than that of smooth bamboo, differing by 5–8%. However, both values were more than 2.8 times lower than those reported for wood and 3.4 times lower than for wood chips [34,35].

Figure 16.

Water absorption of bamboo over 7 days.

This finding demonstrates that surface roughening does not significantly increase the water saturation of crushed bamboo, which can be attributed to the dense arrangement of surface fibres in the plant structure. The relatively low water absorption of crushed bamboo particles is advantageous, as it reduces the water demand during mixture preparation, thereby limiting the leaching of soluble sugars from the bamboo structure and contributing to improved strength development in the cement matrix [24].

To develop wall materials with reduced thermal conductivity and reasonable mechanical characteristics, a series of mix-design experiments was conducted, including the selection and preparation of aggregates of specific fractions. The physico-mechanical properties of the resulting composites were then evaluated on prepared specimens, and the results for materials containing bamboo, wood sawdust, and rice husk are summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Compositions and properties of experimental wall materials.

A comparison of the compressive strength results of mixtures 1 and 2, both containing coarse bamboo fractions, shows that the strength of mixture 2 increased by 44%. This improvement is attributed to the enhanced adhesion of the cement matrix to the roughened bamboo surface. A similar trend was observed for fine bamboo fractions: the use of roughened particles in mixture 6 increased compressive strength by 39% compared with mixture 5, which contained smooth particles. Furthermore, comparing mixtures 1 and 5 demonstrates that additional grinding of bamboo, even with a smooth surface texture, led to a 53% increase in strength. The same dependence was observed between mixtures 2 and 6 with roughened bamboo, where mixture 6 exhibited a 48% increase in compressive strength compared with mixture 2.

To further improve the composite structure, wood sawdust was introduced to fill the voids within the crushed bamboo framework. Despite the increase in density from 660 to 800 kg/m3, the addition of sawdust reduced thermal conductivity from 0.15 to 0.13 W/(m∙K). The presence of sawdust also enhanced the cohesion of the composite structure, which had a positive effect on compressive strength. For mixtures 1–4, which were based on coarse bamboo fractions, the addition of sawdust increased compressive strength by 33–75%, regardless of the surface texture of the aggregate. A similar effect was observed in mixtures 5–8 with fine bamboo fractions, where the addition of sawdust improved compressive strength by 35–58%.

The replacement of sawdust with rice husk did not significantly affect thermal conductivity, which remained within 0.137–0.140 W/(m∙K) for mixtures 9–12. However, the use of fine bamboo fractions (mixtures 11 and 12) increased compressive strength by 31–37% compared with mixtures 9 and 10. Additionally, samples containing bamboo with a smooth texture (mixtures 9 and 11) showed 16–19% lower compressive strength compared with those containing roughened bamboo (mixtures 10 and 12).

An important distinction between mixtures with rice husk and those with sawdust is the reduced water demand. Mixtures 9–12 required 1.6 times less water during preparation, due to the substantially lower water absorption capacity of rice husk compared with wood sawdust [37]. The reduced water demand, combined with the inherently rough surface texture of rice husk, contributed to an 11–19% increase in compressive strength for mixtures 9–12 compared with the sawdust-containing mixtures. However, replacing sawdust with rice husk resulted in a slight increase in thermal conductivity, by approximately 6%, which is consistent with the higher intrinsic thermal conductivity of rice husk compared with wood sawdust [38].

The composites developed in this study are intended for use as lightweight wall materials. According to the obtained density values of 660–800 kg/m3 and compressive strength of 0.8–2.6 MPa, the composites fall within the range of lightweight aggregate concretes with open structure (LAC), which may be used for structural–insulating masonry [39]. The strongest composites (No. 8, 11, and 12), with a compressive strength of 2.1–2.6 MPa and a thermal conductivity of 0.132–0.140 W/(m·K), can be applied as load-bearing or self-bearing external and internal walls in single-storey or low-rise buildings, corresponding to class LAC 2 according to the EN 1520:2011 [26] standard. The remaining mixtures (0.8–1.9 MPa) are more suitable for non-load-bearing or lightly loaded applications, where their low thermal conductivity (0.129–0.162 W/(m·K)) provides the primary functional benefit.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a technical solution for the rational utilization of bamboo, a rapidly renewable raw material, in the production of environmentally safe structural–thermal insulation wall blocks and panels for construction applications. The investigations demonstrated that mechanical surface roughening of bamboo stems enhances the interfacial adhesion between bamboo aggregate particles and the cement matrix, thereby enabling the effective use of crushed bamboo as an aggregate in structural–insulating composites. Microscopic analyses confirmed that imparting a grooved surface texture with an average depth of approximately 2140 nm (2.14 µm) is sufficient to increase compressive strength by 42–50%, yielding values of 1.2–1.7 MPa. At the same time, microstructural features such as parenchyma cells (20 × 60 µm) in the inner stem contribute to low thermal conductivity, while the abundance and dense packing of fibres in the hypodermis of the outer stem provide inherent mechanical strength. The synergistic effect of crushed bamboo with fine fillers, such as wood sawdust or rice husk, further optimized the material performance by filling voids between coarse particles, resulting in a denser structure. This modification improved compressive strength by 33–58% and simultaneously reduced thermal conductivity by 12–18%. Consequently, optimal formulations of structural–thermal insulation wall composites were identified: mixtures with crushed bamboo and wood sawdust achieved a density of 800 kg/m3, compressive strength of 2.3 MPa, and thermal conductivity of 0.132 W/(m∙K), while composites containing bamboo and rice husk reached 2.6 MPa compressive strength with a thermal conductivity of 0.14 W/(m∙K) at the same density. These results highlight the potential of crushed bamboo, particularly when combined with secondary plant-based fillers, as a sustainable aggregate for effective structural–insulation materials.

Future studies are planned to concentrate on the development of mixtures based on crushed bamboo and the investigation of a broader set of performance characteristics, including temperature–humidity curing conditions, sorption moisture, the effect of moisture on thermal conductivity, biological resistance (fungal growth resistance), long-term durability, and climatic chamber testing to determine heat flux densities, thermal conductivity coefficients, and moisture content of the samples. Full-scale testing under real building operating conditions is also envisaged.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B., A.Y. and O.K.; methodology, A.B., A.Y. and O.K.; investigation, A.B., N.B., Y.T. and J.W.; validation, A.Y., N.B., O.K. and J.W.; data curation, A.B., N.B., Y.T. and J.W.; visualization, Y.T. and J.W.; supervision, A.B., N.B., O.K. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, N.B. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, A.B., A.Y., O.K. and Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wei, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, L.; Qin, Z.; Wang, G. Bamboo as a substitute for plastic: Effects of moisture content on the flexibility and flexural toughness of bamboo with cellulose fibres at multiple scales. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Q.; Zhang, W.; Pan, Z.; Zheng, J.; Yu, C.; Zhang, G. Study on the mechanical and durability properties of 3D-printed bamboo fibre-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 478, 141464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, L.; He, L.; Guo, R.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Muhammad, Y.; Liu, Y. Research progresses of fibres in asphalt and cement materials: A review. J. Road Eng. 2023, 3, 35–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Duan, S.; Yu, W.; Kang, J.; Xu, L.; Sheng, Y. Performance evaluation and durability assessment of bamboo fibre-reinforced stone mastic asphalt mixtures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.; Urdaneta, F.; Cordoba, Y.; Meza, L.; Urdaneta, I.; Jameel, H.; Gonzalez, R.W. Assessing bleached bamboo fibres as a hardwood replacement via kraft co-cooking for paperboard applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 232, 121252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Chen, T.; Ba, C.; Reina, T.R.; Yu, J. Preparation of sorbents derived from bamboo and bromine flame retardant for elemental mercury removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 410, 124583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.; Zulkifli, R.; Mat Tahir, M.F.; Gaaz, T.S.; Salih, A.A. Optimization of fibre parameters for the mechanical strength of bamboo fibre/epoxy composites using central composite design. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, G.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, D.; Lal, P.S. Preparation and characterization of fluff from bamboo as source of fibre for the production of hygiene products. Adv. Bamboo Sci. 2025, 12, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.M.; Chandrasekhara, S.M. Chapter Five—Properties of bamboo fibres: Physical, performance, comfort, thermal, and low-stress mechanical properties. In Bamboo Fibres; Babu, K.M., Chandrasekhara, S.M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 101–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N.; Ramyasree, P.; Mallik, M.; Dubey, S. A novel dataset for green bamboo compressive strength analysis. Adv. Bamboo Sci. 2024, 9, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, Z.; Tang, J.; Zhou, T.; Xiong, T.; Gao, X. Reducing steel fibre segregation and enhancing UHPC performance with hybrid bamboo fibres: An eco-friendly approach. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 107, 112741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, T.; Tang, J.; Li, Z.; Yao, C.; Gao, X. Temperature-adaptive mechanism of bamboo fibres for regulating elevated temperature performance of UHPC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 471, 140674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, C.; Mazlan, D.; Kumar, S.S.N. Sustainable thermoelectric energy harvesting in fly ash bamboo fibre reinforced concrete for smart infrastructure. Energy Build. 2025, 343, 115927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, L.; Hu, S.; Zhu, B.; Ye, P. Experimental and theoretical studies on fracture performance of bamboo fibre-reinforced lightweight aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 465, 140250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Ding, M.; Wang, L.; Wei, Y. Experimental study on mechanical properties of raw bamboo fibre-reinforced concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e04003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Y. Mechanical and impermeability properties of bamboo fibre reinforced concrete before and after wet-dry cycling. Structures 2025, 73, 108363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilar, F.A.; Shilar, M.A.; Ganachari, S.V. Advancing sustainable construction: Bamboo fibres in clay-based geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 104, 112247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, M.; Ngo, T.T.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, W.; Li, B. Mechanical and thermal properties of structural lightweight bamboo fibre-reinforced insulating mortar. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Shu, C.; Dai, R.; Chen, H.; Shan, Z. Mechanical, thermal and acoustical characteristics of composite board kneaded by leather fibre and semi-liquefied bamboo. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 340, 128146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, O.C.; Putra, N.; Rahmasari, K.; Salsabila, N.D.; Smitha, K.D.; Widyarko, W.; Nasution, G.G.; Waasthia, D.; Alkadri, M.F.; Setyowardhani, H.; et al. Thermal performance of bio-based phase change material encapsulated in a bamboo wall for residential buildings: A field experiment. Energy Build. Environ. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, K.; Feng, Z.; Zhao, J.; Huang, G.; Liu, W.V. Developing thermal insulation concrete with enhanced mechanical strength using belitic calcium sulfoaluminate cement and wood chips. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 447, 138146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas Hernandez, G.; García Chumacero, J.M.; Villegas Granados, L.M.; Arriola Carrasco, G.G.; Marín Bardales, N.H. Sustainable use of wood sawdust as a replacement for fine aggregate to improve the properties of concrete: A Peruvian case study. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagubkin, A.; Shabanov, A.M.; Niyakovskii, V.I.; Romanovski, V. Maximizing strength and durability in wood concrete (arbolite) via innovative additive control and consumption. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2025, 15, 13365–13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, B.; Gao, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z. Biological, Anatomical, and Chemical Characteristics of Bamboo. In Secondary Xylem Biology; Kim, Y.S., Funada, R., Singh, A.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 197-1:2011; Cement—Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- EN 1520:2011; Prefabricated Reinforced Components of Lightweight Aggregate Concrete with Open Structure with Structural or Non-Structural Reinforcement. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- ASTM C39/C39M-24; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- EN 12667:2001; Thermal Performance of Building Materials and Products—Determination of Thermal Resistance by Means of Guarded Hot Plate and Heat Flow Meter Methods—Products of High and Medium Thermal Resistance. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2001.

- LeBorgne, M.R.; Gutkowski, R. Effects of various admixtures and shear keys in wood–concrete composite beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1730–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohestani, B.; Koubaa, A.; Belem, T.; Bussière, B.; Bouzahzah, H. Experimental investigation of mechanical and microstructural properties of cemented paste backfill containing maple-wood filler. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 121, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olorunnisola, A.O. Effects of husk particle size and calcium chloride on strength and sorption properties of coconut husk–cement composites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2009, 29, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbotina, N.; Gorlenko, N.; Sarkisov, Y.; Naumova, L.; Minakova, T. Control of structurization processes in wood–cement systems at fixed pH. AIP Conf. Proc. 2016, 1698, 060003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govin, A.; Peschard, A.; Guyonnet, R. Modification of cement hydration at early ages by natural and heated wood. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2006, 28, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.K.; Das, S.K.; Mondal, S. Microstructural characterization of bamboo. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhu, D.; Fan, S.; Rahman, M.Z.; Guo, S.; Chen, F. Structural and mechanical properties of bamboo fibre bundle and fibre/bundle reinforced composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 1162–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xie, Y.; Long, G.; Li, J. Effect of surface characteristics of aggregates on the compressive damage of high-strength concrete based on 3D discrete element method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 301, 124101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, G.C.; Jang, S.S.; Kwak, H.J.; Lee, S.R.; Oh, Y.K.; Park, K.K. Characteristics of rice hulls, sawdust, wood shavings and a mixture of sawdust and wood shavings, and their usefulness according to the pen location for Hanwoo cattle. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 29, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, F.; Bakatovich, A.; Davydenko, N.; Joshi, A. Building insulation materials based on agricultural wastes. In Bio-Based Materials and Biotechnologies for Eco-Efficient Construction; Pacheco-Torgal, F., Ivanov, V., Tsang, D.C.W., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thienel, K.-C.; Haller, T.; Beuntner, N. Lightweight Concrete—From Basics to Innovations. Materials 2020, 13, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).