Sex Differences in the Metabolic Cost of a Military Load Carriage Task: A Field Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

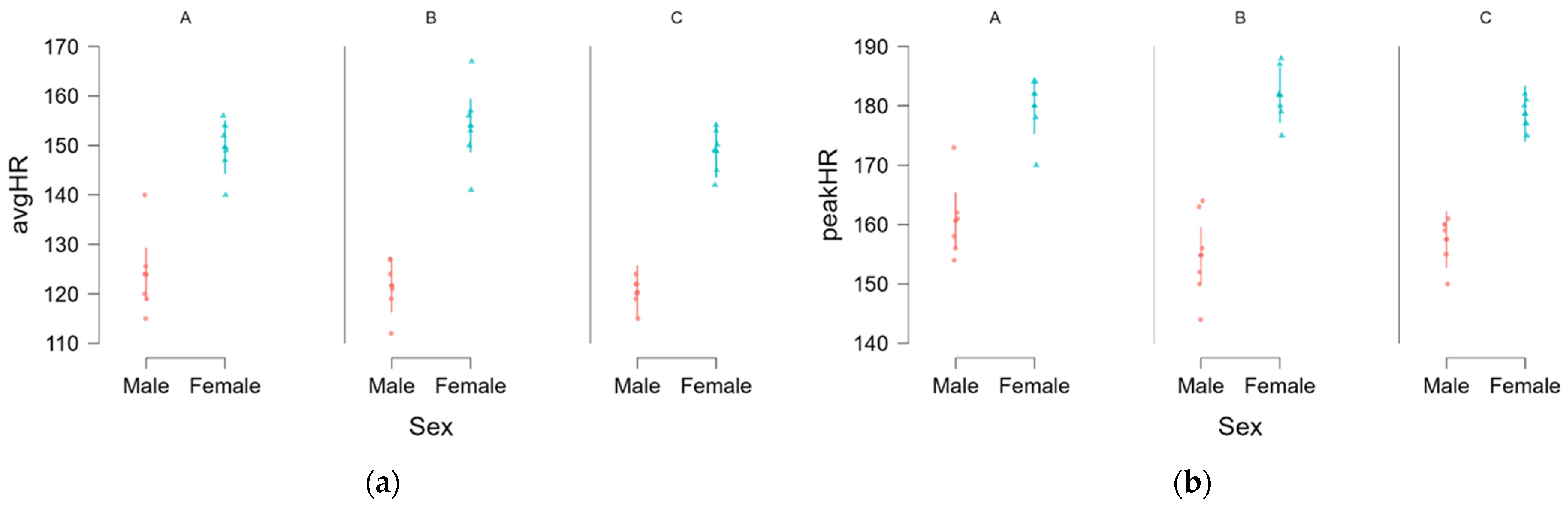

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HR | Heart Rate |

| VO2 | Oxygen Consumption |

References

- Knapik, J.; Reynolds, K. Chapter 11: Load carriage in military operations: A review of historical, physiological, biomechanical and medical aspects. In Military Quantitative Physiology: Problems and Concepts in Military Operational Medicine; Borden Institute: Maryland, MD, USA, 2012; pp. 303–337. [Google Scholar]

- Drain, J.; Billing, D.; Neesham-Smith, D.; Aisbett, B. Predicting physiological capacity of human load carriage—A review. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 52, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayville, W.C. A Soldier’s Load. Infantry 1987. Vol. 77, No. 1. Available online: https://www.regimentalrogue.com/soldiers_load/1987_Mayville_A_Soldiers_Load.htm (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Orr, R.; Pope, R.; Lopes, T.J.A.; Leyk, D.; Blacker, S.; Bustillo-Aguirre, B.S.; Knapik, J.J. Soldier Load Carriage, Injuries, Rehabilitation and Physical Conditioning: An International Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.; Pope, R.; Johnston, V.; Coyle, J. Soldier self-reported reductions in task performance associated with operational load carriage. J. Aust. Strength. Cond. 2013, 21, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, N.A.; Peoples, G.E.; Petersen, S.R. Load carriage, human performance, and employment standards. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S131–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Tan, M.; Tan, P. Effects of loaded march on marksmanship performance. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, S176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Cosano, J.; Orantes-Gonzalez, E.; Heredia-Jimenez, J. Effect of carrying different military equipment during a fatigue test on shooting performance. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2019, 19, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapik, J.J.; Reynolds, K.L.; Harman, E. Soldier load carriage: Historical, physiological, biomechanical, and medical aspects. Mil. Med. 2004, 169, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billing, D.C.; Silk, A.J.; Tofari, P.J.; Hunt, A.P. Effects of military load carriage on susceptibility to enemy fire during tactical combat movements. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2015, 29, S134–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, N.C.; Smith, S.; Risius, D.; Doyle, D.; Wardle, S.; Greeves, J.; House, J.; Tipton, M.; Lomax, M. Cognitive performance of military men and women during prolonged load carriage. BMJ Mil. Health 2023, 169, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, B.; Tomporowski, P.D.; Ferrara, M. Effects of backpack load on balance and decisional processes. Mil. Med. 2009, 174, 1308–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, C.R.; Hirsch, E.; Hasselquist, L.; Lesher, L.L.; Lieberman, H.R. The effects of movement and physical exertion on soldier vigilance. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2007, 78, B51–B57. [Google Scholar]

- Schram, B.; Canetti, E.; Orr, R.; Pope, R. Injury rates in female and male military personnel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schram, B.; Canetti, E.; Orr, R.; Pope, R. Risk factors for injuries in female soldiers: A systematic review. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schram, B.; Orr, R.; Niederberger, B.; Givens, A.; Bernards, J.; Kelly, K.R. Cardiovascular Demand Differences Between Male and Female US Marine Recruits During Progressive Loaded Hikes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, e454–e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.M.; Pope, R.; Coyle, J.; Johnston, V. Occupational loads carried by Australian soldiers on military operations. J. Health Saf. Environ. 2015, 31, 451–467. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, N.C. Reducing the Burden on the Dismounted Soldier. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.M.; Pope, R. Gender differences in load carriage injuries of Australian army soldiers. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, J.; Dencker, M.; Bremander, A.; Olsson, M.C. Cardiorespiratory responses of load carriage in female and male soldiers. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 101, 103710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, K.; Vickery-Howe, D.; Dascombe, B.; Clarke, A.; Wheat, J.; McClelland, J.; Drain, J. Mechanical Differences between Men and Women during Overground Load Carriage at Self-Selected Walking Speeds. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickery-Howe, D.; Dascombe, B.; Drain, J.; Clarke, A.; Hoolihan, B.; Carstairs, G.; Reddy, A.; Middleton, K. Physiological, Perceptual, and Biomechanical Responses to Load Carriage While Walking at Military-Relevant Speeds and Loads—Are There Differences between Males and Females? Biomechanics 2024, 4, 382–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoolihan, B.; Wheat, J.; Dascombe, B.; Vickery-Howe, D.; Middleton, K. The effect of external loads and biological sex on coupling variability during load carriage. Gait Posture 2023, 100, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, T.J.; Saunders, S.C.; McGuire, S.J.; Izard, R.M. Sex differences in neuromuscular fatigability in response to load carriage in the field in British Army recruits. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, B. Doctors revise declaration of Helsinki. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2000, 321, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health & Medical Research Council. Ethical Considerations in Quality Assurance and Evaluation Activities. 2014. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/ethical-considerations-quality-assurance-and-evaluation-activities (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Roberts, D.E.; Reading, J.E.; Daley, J.L.; Hodgdon, J.A.; Pozos, R.S. A Physiological and Biomechanical Evaluation of Commercial Load-Bearing Ensembles for the US Marine Corps; Naval Health Research Center: San Diego, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Burger, S.; Bertram, S.; Stewart, R. Assessment of the 2, 4 km run as a predictor of aerobic capacity. South. Afr. Med. J. 1990, 78, 327–329. [Google Scholar]

- Board, L.; Ispoglou, T.; Ingle, L. Validity of telemetric-derived measures of heart rate variability: A systematic review. J. Exerc. Physiol. Online 2016, 19, 64–84. [Google Scholar]

- Merrigan, J.J.; Stovall, J.H.; Stone, J.D.; Stephenson, M.; Finomore, V.S.; Hagen, J.A. Validation of Garmin and Polar Devices for Continuous Heart Rate Monitoring During Common Training Movements in Tactical Populations. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2023, 27, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoye, A.H.K.; Vondrasek, J.D.; Hancock, J.B., II. Validity and Reliability of the VO2 Master Pro for Oxygen Consumption and Ventilation Assessment. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2020, 13, 1382–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Roberts, A.; Irving, S.; Orr, R. Aerobic Fitness is of Greater Importance than Strength and Power in the Load Carriage Performance of Specialist Police. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2018, 11, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauschild, V.D.; DeGroot, D.W.; Hall, S.M.; Grier, T.L.; Deaver, K.D.; Hauret, K.G.; Jones, B.H. Fitness tests and occupational tasks of military interest: A systematic review of correlations. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.H.; Hauret, K.G.; Dye, S.K.; Hauschild, V.D.; Rossi, S.P.; Richardson, M.D.; Friedl, K.E. Impact of physical fitness and body composition on injury risk among active young adults: A study of Army trainees. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, S17–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, P.R. The reliability of the VO2 Master Pro metabolic analyzer and comparison with the Cosmed Quark. Sci. Sports 2024, 39, 706–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiessen, J.; Guluzade, N.; Faricier, R.; Keir, D. (Re)assessment of the COSMED Quark CPET and VO2Master Pro Systems for Measuring Pulmonary Gas Exchange and Ventilation. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2025, 35, 70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keselman, H.J.; Algina, J.; Kowalchuk, R.K.; Wolfinger, R.D. The analysis of repeated measurements: A comparison of mixed-model satterthwaite f tests and a nonpooled adjusted degrees of freedom multivariate test. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 1999, 28, 2967–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Christensen, R.H.B. lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijders, T.A.; Bosker, R. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling; Sage Pubns Ltd.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, A. Scaling regression inputs by dividing by two standard deviations. Stat. Med. 2007, 27, 2865–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Barwood, M.; Low, C.; Wills, J.; Fish, M. A systematic review of the physiological and biomechanical differences between males and females in response to load carriage during walking activities. Appl. Ergon. 2024, 114, 104123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godhe, M.; Helge, T.; Mattsson, C.M.; Ekblom, Ö.; Ekblom, B. Physiological factors of importance for load carriage in experienced and inexperienced men and women. Mil. Med. 2020, 185, e1168–e1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santee, W.R.; Allison, W.F.; Blanchard, L.A.; Small, M.G. A proposed model for load carriage on sloped terrain. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2001, 72, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Atakan, M.M.; Yan, X.; Turnagöl, H.H.; Duan, H.; Peng, L. Graded exercise test with or without load carriage similarly measures maximal oxygen uptake in young males and females. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapik, J.; Harman, E.; Steelman, R.; Graham, B. A systematic review of the effects of physical training on load carriage performance. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.M.; Robinson, J.; Hasanki, K.; Talaber, K.A.; Schram, B.; Roberts, A. The Relationship Between Strength Measures and Task Performance in Specialist Tactical Police. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratamess, N. ACSM’s Foundations of Strength Training and Conditioning; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei, S.; Grillone, G.; Di Michele, R.; Cortesi, M. A comparison between male and female athletes in relative strength and power performances. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2021, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuzzo, J.L. Narrative review of sex differences in muscle strength, endurance, activation, size, fiber type, and strength training participation rates, preferences, motivations, injuries, and neuromuscular adaptations. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 494–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varley-Campbell, J.; Cooper, C.; Wilkerson, D.; Wardle, S.; Greeves, J.; Lorenc, T. Sex-specific changes in physical performance following military training: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2623–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, N.S.; Mangione, T.W.; Hemenway, D.; Amoroso, P.J.; Jones, B.H. High injury rates among female army trainees: A function of gender? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000, 18, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, J.A.; Drain, J.; Fuller, J.T.; Doyle, T.L. Physiological responses of female load carriage improves after 10 weeks of training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 1763–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, Y.; Fleischmann, C.; Yanovich, R.; Heled, Y. Physiological and Medical Aspects That Put Women Soldiers at Increased Risk for Overuse Injuries. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29 (Suppl. S11), S107–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Males (n = 6) | Females (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 26.3 ± 5.0 | 26.5 ± 6.6 |

| Years of Experience (yrs) | 7.2 ± 4.9 | 6.3 ± 5.5 |

| Height (cm) | 182.3 ± 6.2 | 167.4 ± 6.9 * |

| Uniformed weight (kg) | 88.2 ± 8.7 | 70.9 ± 10.6 * |

| Relative load (%) | 34.3 ± 3.4 | 43.2±7.5 * |

| Predicted VO2 (mL/kg/min) | 56.7 ± 6.1 | 45.0 ± 2.9 * |

| Term | b | SE b | df | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average HR | ||||

| Intercept | 136.410 | 1.390 | 10 | 98.17 |

| Sex (F) | −14.436 | 1.390 | 10 | −10.389 |

| Variant (B) | 0.386 | 1.224 | 20 | 0.315 |

| Variant (C) | 1.419 | 1.224 | 20 | 1.159 |

| Sex (F) × Variant (B) | 1.569 | 1.224 | 20 | 1.282 |

| Sex (F) × Variant (C) | −1.731 | 1.224 | 20 | −1.413 |

| Peak HR | ||||

| Intercept | 168.917 | 1.324 | 10 | 127.571 |

| Sex (F) | −11.25 | 1.324 | 10 | −8.496 |

| Variant (B) | 1.417 | 0.899 | 20 | 1.577 |

| Variant (C) | −0.583 | 0.899 | 20 | −0.649 |

| Sex (F) × Variant (B) | 1.583 | 0.899 | 20 | 1.762 |

| Sex (F) × Variant (C) | −2.25 | 0.899 | 20 | −2.504 |

| Term | B | SE B | df | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average VO2 | ||||

| Intercept | 26.100 | 1.49 | 4 | 17.521 |

| Sex (F) | −4.678 | 1.49 | 4 | −3.14 |

| Variant (B) | 0.033 | 0.657 | 8 | 0.051 |

| Variant (C) | 0.533 | 0.657 | 8 | 0.812 |

| Sex (F) × Variant (B) | −0.922 | 0.657 | 8 | −1.404 |

| Sex (F) × Variant (C) | 0.244 | 0.657 | 8 | 0.372 |

| Peak VO2 | ||||

| Intercept | 45.639 | 1.72 | 4 | 26.561 |

| Sex (F) | −3.972 | 1.718 | 4 | −2.312 |

| Variant (B) | 0.644 | 0.619 | 8 | 1.04 |

| Variant (C) | −1.089 | 0.619 | 8 | −1.758 |

| Sex (F) × Variant (B) | −0.011 | 0.619 | 8 | −0.018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schram, B.; Rosseau, J.; Canetti, E.F.D.; Orr, R. Sex Differences in the Metabolic Cost of a Military Load Carriage Task: A Field Based Study. Sports 2025, 13, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120442

Schram B, Rosseau J, Canetti EFD, Orr R. Sex Differences in the Metabolic Cost of a Military Load Carriage Task: A Field Based Study. Sports. 2025; 13(12):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120442

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchram, Ben, Jacques Rosseau, Elisa F. D. Canetti, and Robin Orr. 2025. "Sex Differences in the Metabolic Cost of a Military Load Carriage Task: A Field Based Study" Sports 13, no. 12: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120442

APA StyleSchram, B., Rosseau, J., Canetti, E. F. D., & Orr, R. (2025). Sex Differences in the Metabolic Cost of a Military Load Carriage Task: A Field Based Study. Sports, 13(12), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120442