Skin Temperature as a Marker of Physical Fitness Profile: The Impact of High-Speed Running in Professional Soccer Players

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Description of IRT Assessment

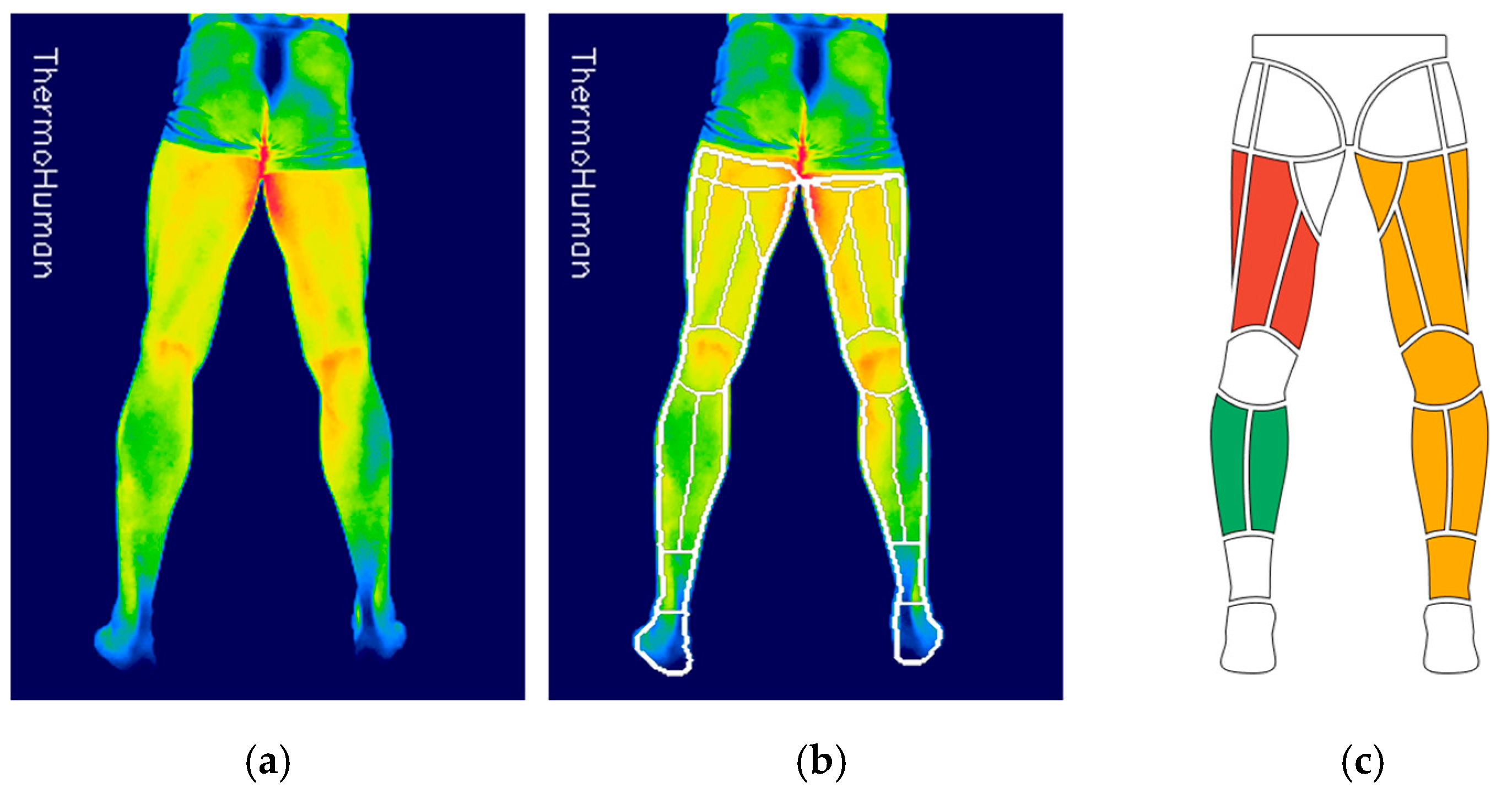

2.2.2. Extraction of Thermal Regions Using the Software

2.2.3. Acquisition of GPS Data During the Season

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HSR | High-speed running |

| GPS | Global Positioning Systems |

| IRT | Infrared thermography |

| PI | Postero-inferior |

| ΔT | Relative temperature change |

| MD | Match day |

| DIST | Total distance |

References

- Pons, E.; Ponce-Bordón, J.C.; Díaz-García, J.; López del Campo, R.; Resta, R.; Peirau, X.; García-Calvo, T. A longitudinal exploration of match running performance during a football match in the Spanish La Liga: A four-season study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.E.; Forte, P.; Ferraz, R.; Leal, M.; Ribeiro, J.; Silva, A.J.; Barbosa, T.M.; Monteiro, A.M. Monitoring accumulated training and match load in football: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, W.; Doran, D.; Hawkins, R.; Evans, M.; Laws, A.; Bradley, P. Contextualised high-intensity running profiles of elite football players with reference to general and specialised tactical roles. Biol. Sport 2023, 40, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, M.; Krustrup, P.; Bangsbo, J. Match performance of high-standard soccer players with special reference to development of fatigue. J. Sports Sci. 2003, 21, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimpchen, J.; Gopaladesikan, S.; Meyer, T. The intermittent nature of player physical output in professional football matches: An analysis of sequences of peak intensity and associated fatigue responses. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 21, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hernández, D.; Quinn, M.; Jones, P. Linear advancing actions followed by deceleration and turn are the most common movements preceding goals in male professional soccer. Sci. Med. Footb. 2023, 7, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hostrup, M.; Bangsbo, J. Performance Adaptations to Intensified Training in Top-Level Football. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, C.; Edwards, A.; Fysh, M.; Drust, B. Effects of high-intensity running training on soccer-specific fitness in professional male players. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, S.; Owen, A.; Mendes, B.; Hughes, B.; Collins, K.; Gabbett, T.J. High-speed running and sprinting as an injury risk factor in soccer: Can well-developed physical qualities reduce the risk? J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djaoui, L.; Garcia, J.D.-C.; Hautier, C.; Dellal, A. Kinetic post-match fatigue in professional and youth soccer players during the competitive period. Asian J. Sports Med. 2016, 7, e28267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krustrup, P.; Ørtenblad, N.; Nielsen, J.; Nybo, L.; Gunnarsson, T.P.; Iaia, F.M.; Madsen, K.; Stephens, F.; Greenhaff, P.; Bangsbo, J. Maximal voluntary contraction force, SR function and glycogen resynthesis during the first 72 h after a high-level competitive soccer game. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 2987–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nédélec, M.; McCall, A.; Carling, C.; Legall, F.; Berthoin, S.; Dupont, G. Recovery in soccer: Part I—Post-match fatigue and time course of recovery. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 997–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Castillo, Í.M.; Rueda, R.; Bouzamondo, H.; López-Chicharro, J.; Mihic, N. Biomarkers of post-match recovery in semi-professional and professional football (soccer). Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, R.; Page, R.M.; Harper, L.D. The effect of fixture congestion on performance during professional male soccer match-play: A systematic critical review with meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, T.R.; Weckström, K. Fixture congestion modulates post-match recovery kinetics in professional soccer players. Res. Sports Med. 2017, 25, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva Lozano, J.M.; Muyor, J.M.; Pérez-Guerra, A.; Gómez, D.; Garcia-Unanue, J.; Sanchez-Sanchez, J.; Felipe, J.L. Effect of the length of the microcycle on the daily external load, fatigue, sleep quality, stress, and muscle soreness of professional soccer players: A full-season study. Sports Health 2023, 15, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Lozano, J.M.; Muyor, J.M.; Fortes, V.; McLaren, S.J. Decomposing the variability of match physical performance in professional soccer: Implications for monitoring individuals. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 21, 1588–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, R.; Brito, J.P.; Martins, A.; Mendes, B.; Marinho, D.A.; Ferraz, R.; Marques, M.C. In-season internal and external training load quantification of an elite European soccer team. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaruk, H.; Starzak, M.; Porter, J.M. Influence of attentional manipulation on jumping performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hum. Kinet. 2020, 75, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Cuevas, I.; Marins, J.C.B.; Lastras, J.A.; Carmona, P.M.G.; Cano, S.P.; García-Concepción, M.Á.; Sillero-Quintana, M. Classification of factors influencing the use of infrared thermography in humans: A review. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2015, 71, 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marins, J.C.B.; Fernandes, A.A.; Cano, S.P.; Moreira, D.G.; da Silva, F.S.; Costa, C.M.A.; Fernandez-Cuevas, I.; Sillero-Quintana, M. Thermal body patterns for healthy Brazilian adults (male and female). J. Therm. Biol. 2014, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, W.; Júnior, J.L.R.; Paula, L.V.; Chagas, M.H.; Andrade, A.G.; Veneroso, C.E.; Chaves, S.F.; Serpa, T.K.; Pimenta, E.M. C-Reactive Protein and Skin Temperature of the lower limbs of Brazilian elite soccer players like load markers following three consecutive games. J. Therm. Biol. 2022, 105, 103188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majano, C.; García-Unanue, J.; Hernandez-Martin, A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J.; Gallardo, L.; Felipe, J.L. Relationship between Repeated Sprint Ability, Countermovement Jump and Thermography in Elite Football Players. Sensors 2023, 23, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Andrade Fernandes, A.; Pimenta, E.M.; Moreira, D.G.; Sillero-Quintana, M.; Marins, J.C.B.; Morandi, R.F.; Kanope, T.; Garcia, E.S. Effect of a professional soccer match in skin temperature of the lower limbs: A case study. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2017, 13, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, J.L.R.; Duarte, W.; Falqueto, H.; Andrade, A.G.; Morandi, R.F.; Albuquerque, M.R.; de Assis, M.G.; Serpa, T.K.; Pimenta, E.M. Correlation between strength and skin temperature asymmetries in the lower limbs of Brazilian elite soccer players before and after a competitive season. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 99, 102919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, L.; Rhea, M.R.; Maior, A.S. Physiological evaluation post-match as implications to prevent injury in elite soccer players. In Archivos de Medicina del Deporte: Revista de la Federación Española de Medicina del Deporte y de la Confederación Iberoamericana de Medicina del Deporte; Spanish Federation of Sports Medicine: Zaragoza, Spain, 2019; Volume 36, pp. 220–226. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, D.G.; Costello, J.T.; Brito, C.J.; Adamczyk, J.G.; Ammer, K.; Bach, A.J.; Costa, C.M.; Eglin, C.; Fernandes, A.A.; Fernández-Cuevas, I. Thermographic imaging in sports and exercise medicine: A Delphi study and consensus statement on the measurement of human skin temperature. J. Therm. Biol. 2017, 69, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena-Bueno, L.; Priego-Quesada, J.I.; Jimenez-Perez, I.; Gil-Calvo, M.; Pérez-Soriano, P. Validation of ThermoHuman automatic thermographic software for assessing foot temperature before and after running. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 92, 102639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe, J.L.; Garcia-Unanue, J.; Viejo-Romero, D.; Navandar, A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J. Validation of a video-based performance analysis system (Mediacoach®) to analyze the physical demands during matches in LaLiga. Sensors 2019, 19, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priego-Quesada, J.I.; De la Fuente, C.; Kunzler, M.R.; Perez-Soriano, P.; Hervás-Marín, D.; Carpes, F.P. Relationship between skin temperature, electrical manifestations of muscle fatigue, and exercise-induced delayed onset muscle soreness for dynamic contractions: A preliminary study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillen, B.; Pfirrmann, D.; Nägele, M.; Simon, P. Infrared thermography in exercise physiology: The dawning of exercise radiomics. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, R.T. Post-exercise recovery: Cooling and heating, a periodized approach. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 707503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Load Variable (DIST in km; HSR in m) | Minutes Played (min) | Pre PI ST (°C) | Post PI ST (°C) | PI (%ΔT) | Pre Hamstrings ST (°C) | Post Hamstrings ST (°C) | Hamstrings (%ΔT) | Pre Calves ST (°C) | Post Calves ST (°C) | Calves (%ΔT) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIST | +DIST | 10.5 ± 0.6 | 97.5 ± 3.5 | 31.82 ± 0.6 | 31.97 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 2 | 31.9 ± 0.7 | 32.1 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 2 | 31.9 ± 0.7 | 32 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 2 |

| −DIST | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 82.60 ± 13.57 | 31.5 ± 0.6 | 31.96 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 2 | 31.6 ± 0.7 | 32.1 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 3 | 31.6 ± 0.6 | 31.9 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 3 | |

| HSR | +HSR | 584.79 ± 176.32 | 91.76 ± 11.16 | 31.70 ± 0.6 | 31.76 ± 0.7 | 0.1 ± 2 | 31.80 ± 0.6 | 31.79 ± 0.8 | −0.1 ± 3 | 31.65 ± 0.74 | 31.74 ± 0.71 | 0.3 ± 2 |

| −HSR | 269.70 ± 66.48 | 88.23 ± 13.44 | 31.69 ± 0.5 | 32.17 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 2 | 31.74 ± 0.7 | 32.3 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 3 | 31.75 ± 0.57 | 32.21 ± 0.61 | 1.5 ± 2 |

| HSR (m) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | β1 Minutes | β2 HSR Group | CI 95% | p-Value | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | R2 (Marginal = Conditional) | |

| PI (°C) ΔT | −2.57 × 10−5 | −0.006 | −1.46 ± 0.52 | [−2.49, −0.43] | 0.005 * | 0.56 | 0.13 |

| Hamstring (°C) ΔT | −2.69 × 10−5 | −0.009 | −1.79 ± 0.54 | [−2.87, −0.72] | 0.001 * | 0.67 | 0.18 |

| Calves (°C) ΔT | −2.74 × 10−5 | −0.007 | −1.23 ± 0.55 | [−2.32, −0.13] | 0.027 * | 0.48 | 0.09 |

| Total Distance (m) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | β1 Minutes | β2 Dist Group | CI 95% | p-Value | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | R2 (Marginal = Conditional) | |

| PI (°C) ΔT | −2.62 × 10−5 | 0.01 | −1.26 ± 0.69 | [−2.62, 0.09] | 0.06 | 0.32 | 0.07 |

| Hamstring (°C) ΔT | −2.77 × 10−5 | 0.01 | −1.46 ± 0.73 | [−2.90, −0.3] | 0.04 * | 0.36 | 0.09 |

| Calves (°C) ΔT | −2.79 × 10−5 | 0.003 | −0.82 ± 0.73 | [−2.26, 0.62] | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Escamilla-Galindo, V.-L.; Vega-Ramos, A.; Felipe, J.L.; Alonso-Callejo, A.; Fernandez-Cuevas, I. Skin Temperature as a Marker of Physical Fitness Profile: The Impact of High-Speed Running in Professional Soccer Players. Sports 2025, 13, 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120443

Escamilla-Galindo V-L, Vega-Ramos A, Felipe JL, Alonso-Callejo A, Fernandez-Cuevas I. Skin Temperature as a Marker of Physical Fitness Profile: The Impact of High-Speed Running in Professional Soccer Players. Sports. 2025; 13(12):443. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120443

Chicago/Turabian StyleEscamilla-Galindo, Victor-Luis, Armiche Vega-Ramos, Jose Luis Felipe, Antonio Alonso-Callejo, and Ismael Fernandez-Cuevas. 2025. "Skin Temperature as a Marker of Physical Fitness Profile: The Impact of High-Speed Running in Professional Soccer Players" Sports 13, no. 12: 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120443

APA StyleEscamilla-Galindo, V.-L., Vega-Ramos, A., Felipe, J. L., Alonso-Callejo, A., & Fernandez-Cuevas, I. (2025). Skin Temperature as a Marker of Physical Fitness Profile: The Impact of High-Speed Running in Professional Soccer Players. Sports, 13(12), 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120443