Exercise Heart Rate During Training and Competitive Matches in Elite Soccer: More Questions than Answers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Monthly HR Exposure

3.1.1. Volume

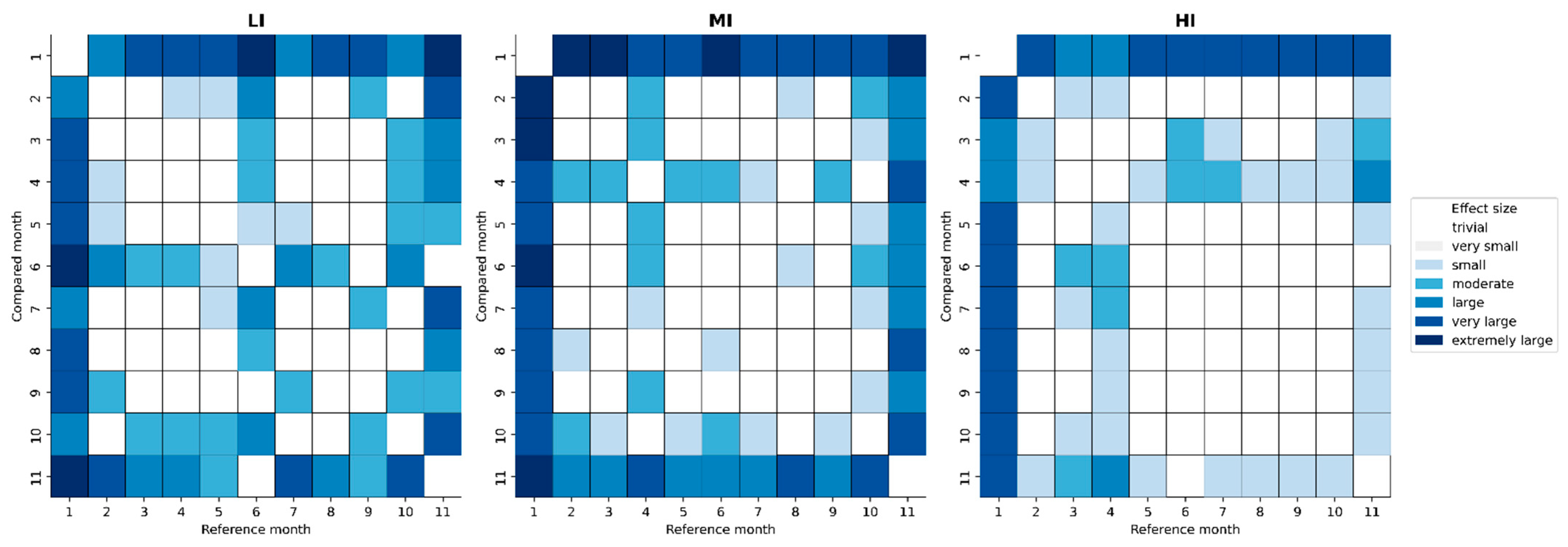

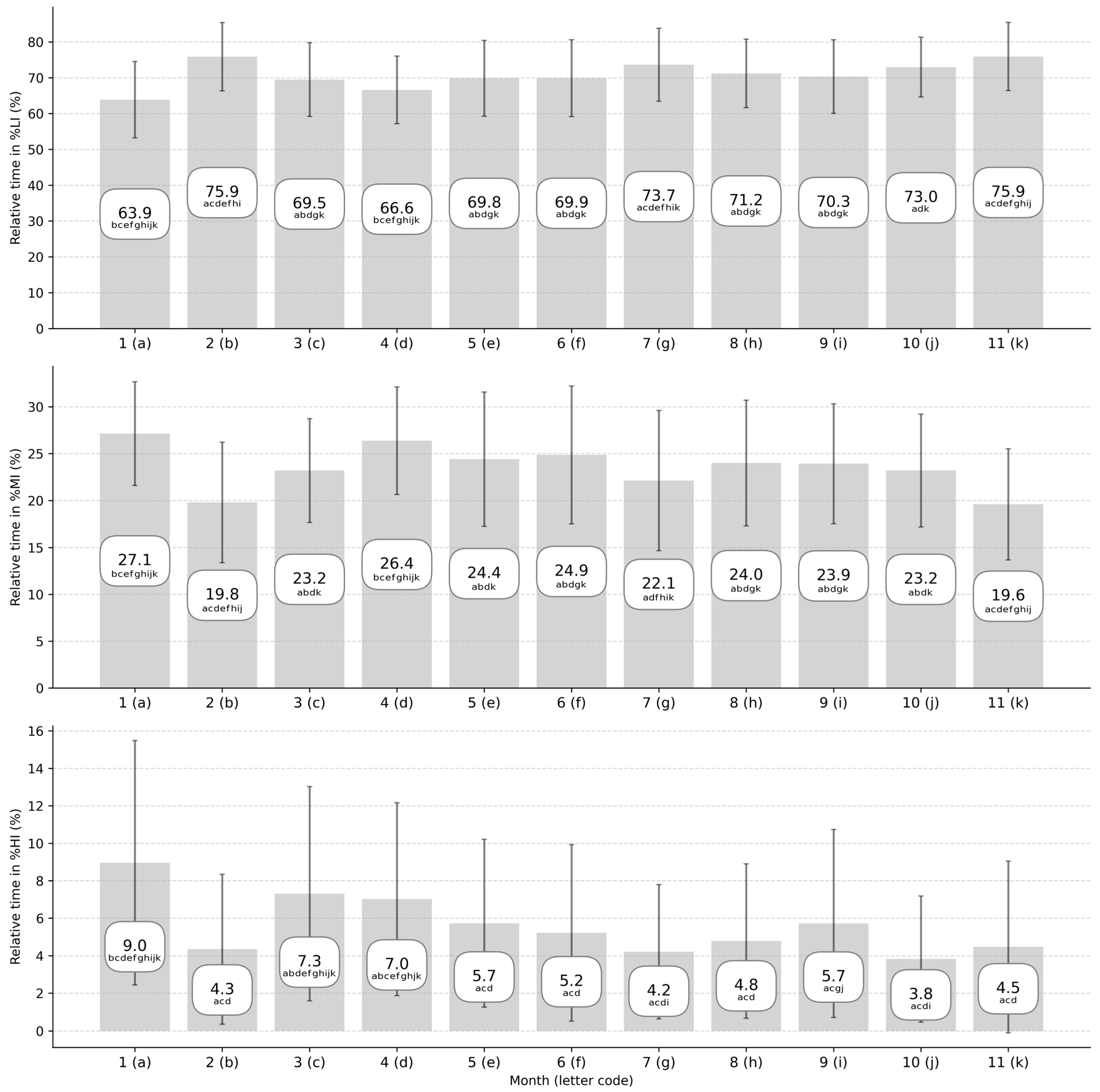

3.1.2. Intensity

3.2. Weekly HR Exposure

3.2.1. Volume

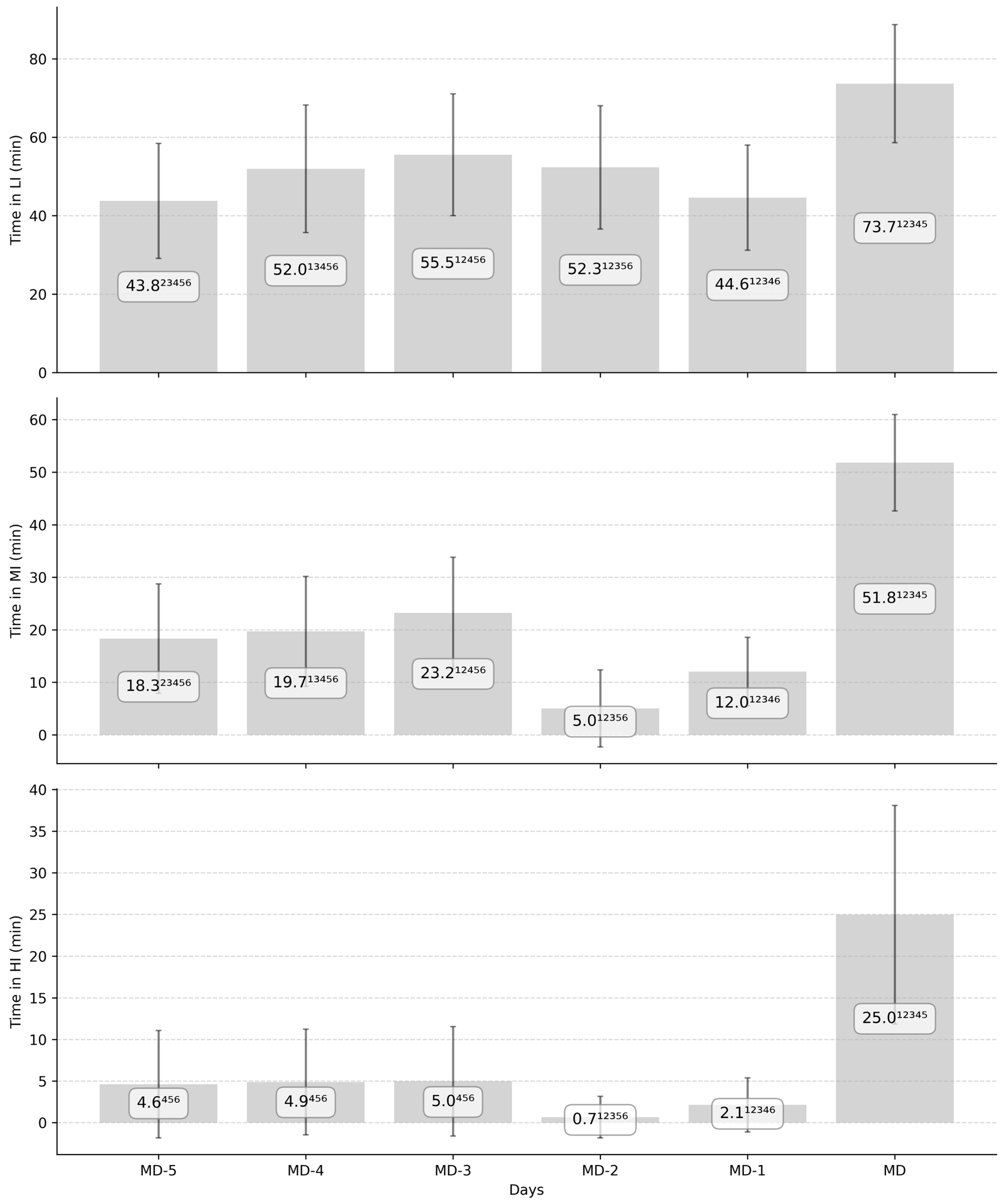

3.2.2. Intensity

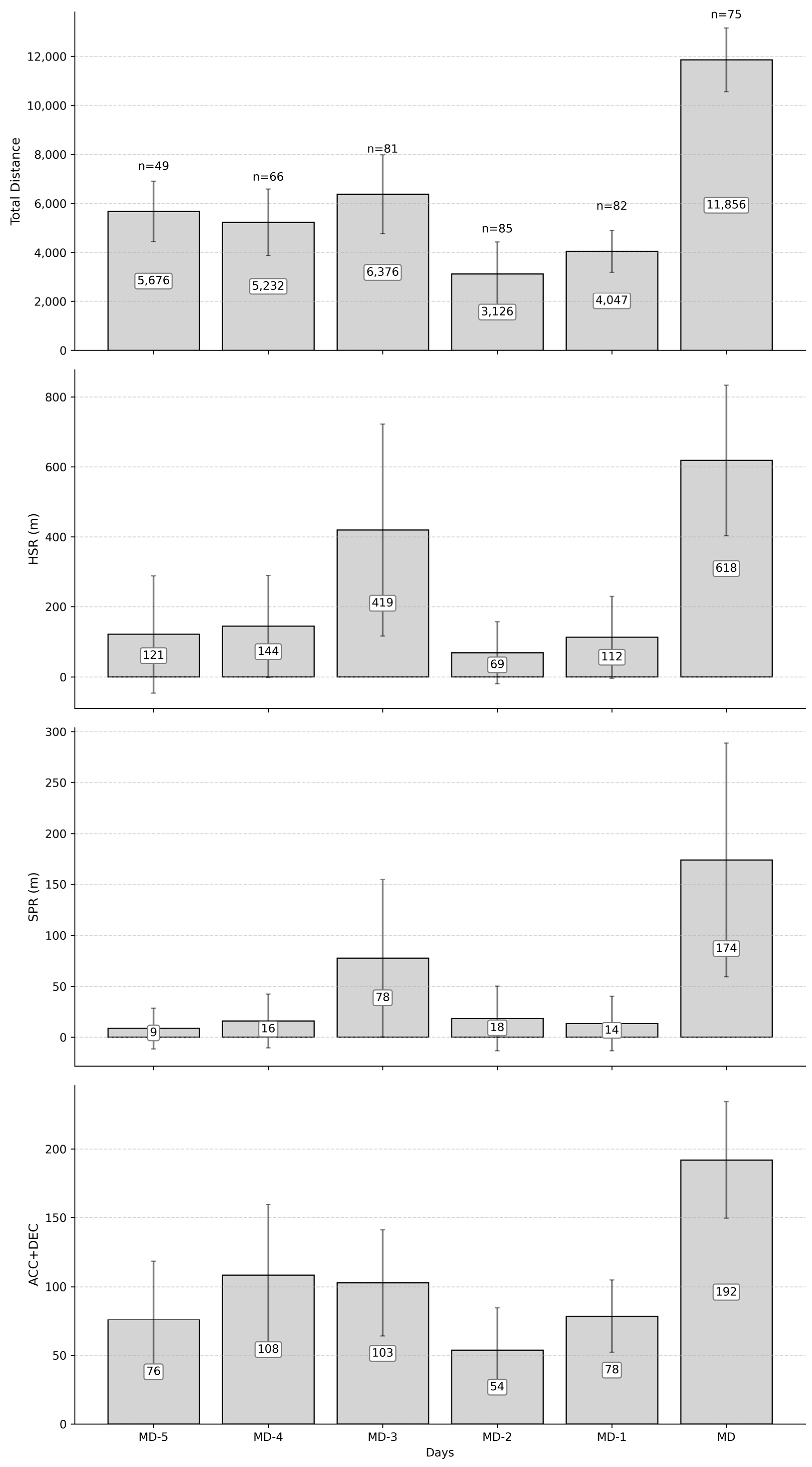

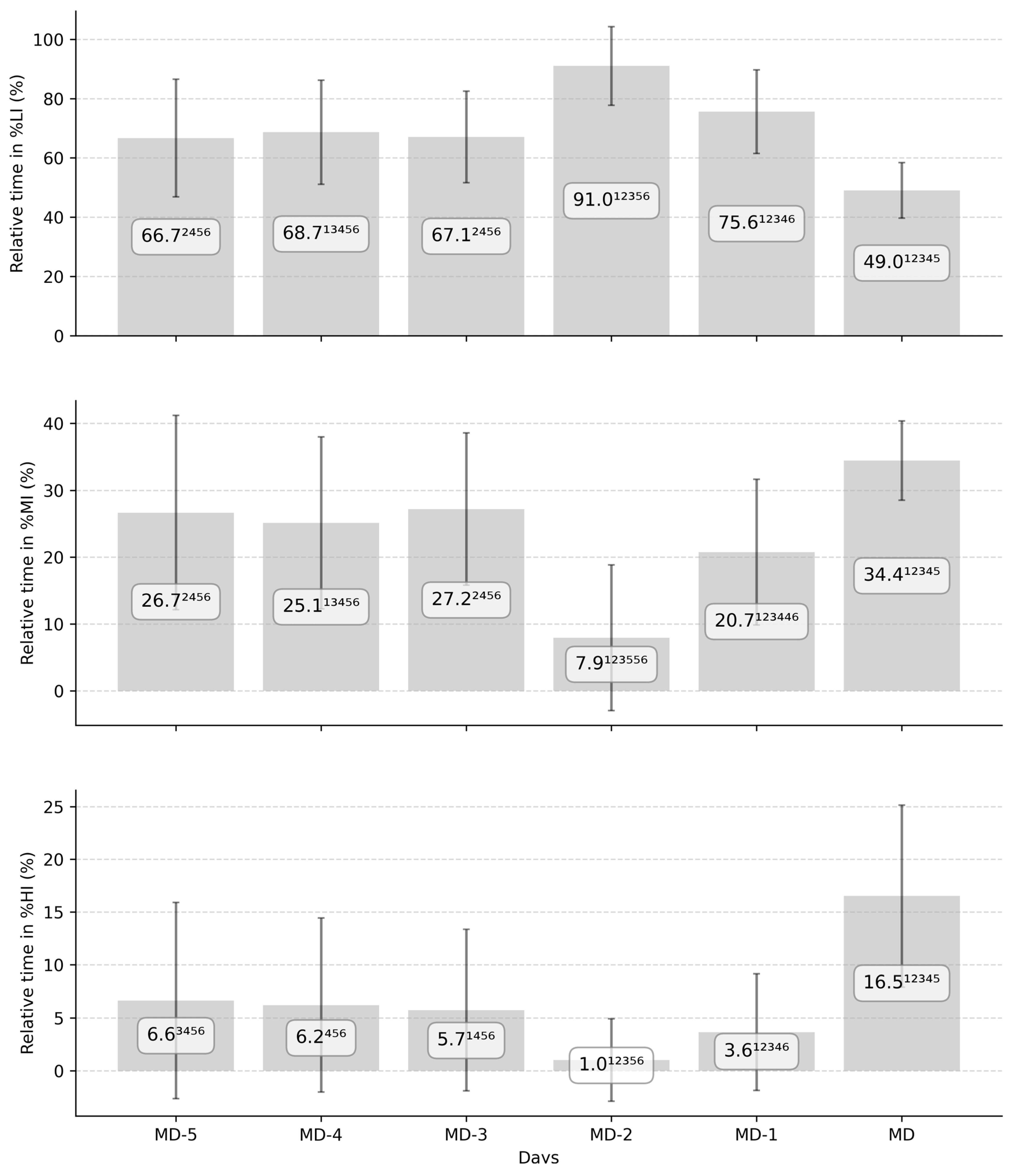

3.3. Match HR Exposure

4. Discussions

4.1. Monthly HR Exposure

4.2. Weekly HR Exposure

4.3. Match HR Exposure

4.4. Current Limitations and Perspectives

5. Conclusions and Practical Applications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Impellizzeri, F.M.; Shrier, I.; McLaren, S.J.; Coutts, A.J.; McCall, A.; Slattery, K.; Jeffries, A.C.; Kalkhoven, J.T. Understanding Training Load as Exposure and Dose. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 1667–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Hader, K. Data everywhere, insight nowhere: A practical quadrant-based model for monitoring training load vs. response in elite football. Sport Perform. Sci. Rep. 2025, 258, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Impellizzeri, F.M.; Marcora, S.M.; Coutts, A.J. Internal and External Training Load: 15 Years On. Int. J. Sport. Physiol. Perform. 2019, 14, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellenger, C.R.; Fuller, J.T.; Thomson, R.L.; Davison, K.; Robertson, E.Y.; Buckley, J.D. Monitoring Athletic Training Status Through Autonomic Heart Rate Regulation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1461–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M. Monitoring training status with HR measures: Do all roads lead to Rome? Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carling, C.; Lacome, M.; McCall, A.; Dupont, G.; Le Gall, F.; Simpson, B.; Buchheit, M. Monitoring of Post-match Fatigue in Professional Soccer: Welcome to the Real World. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2695–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leduc, C.; Lacome, M.; Buchheit, M. The use of standardised runs (and associated data analysis) to monitor neuromuscular status in team sports players: A call to action. Sport Perform. Sci. Rep. 2020, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Viru, A.; Viru, M. Nature of training effects. In Exercise and Sport Science; Garret, W., Kirkendall, D., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Williams: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 67–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bangsbo, J. Energy demands in competitive soccer. J. Sports Sci. 1994, 12, S5–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krustrup, P.; Mohr, M.; Steensberg, A.; Bencke, J.; Kjær, M.; Bangsbo, J. Muscle and blood metabolites during a soccer game: Implications for sprint performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallo, J.; Mena, E.; Nevado, F.; Paredes, V. Physical Demands of Top-Class Soccer Friendly Matches in Relation to a Playing Position Using Global Positioning System Technology. J. Hum. Kinet. 2015, 47, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.; Archer, D.T.; Hogg, B.; Bush, M.; Bradley, P.S. The evolution of physical and technical performance parameters in the English Premier League. Int. J. Sports Med. 2014, 35, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, H.; Coutts, A.J. A comparison of methods used for quantifying internal training load in women soccer players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2008, 3, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Vazquez, M.A.; Toscano-Bendala, F.J.; Mora-Ferrera, J.C.; Suarez-Arrones, L.J. Relationship Between Internal Load Indicators and Changes on Intermittent Performance After the Preseason in Professional Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Impellizzeri, F.M.; Rampinini, E.; Coutts, A.J.; Sassi, A.; Marcora, S.M. Use of RPE-based training load in soccer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 1042–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.R.; Lockie, R.G.; Knight, T.J.; Clark, A.C.; de Jonge, X.A.J. A comparison of methods to quantify the in-season training load of professional soccer players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2013, 8, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, P.; Dos Santos, E.; Grishin, M.; Rocha, J.M. Validity of Heart Rate-Based Indices to Measure Training Load and Intensity in Elite Football Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 2340–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Lacome, M.; Cholley, Y.; Simpson, B.M. Neuromuscular Responses to Conditioned Soccer Sessions Assessed via GPS-Embedded Accelerometers: Insights into Tactical Periodization. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, T.G.A.; de Ruiter, C.J.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Savelsbergh, G.J.P.; Beek, P.J. Quantification of in-season training load relative to match load in professional Dutch Eredivisie football players. Sci. Med. Footb. 2017, 1, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banister, E.W.; Calvert, T.W.; Savage, M.V.; Bach, T.M. A systems model training for athletic performance. Aust. J. Sports Med. 1975, 7, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Akubat, I.; Abt, G. Intermittent exercise alters the heart rate-blood lactate relationship used for calculating the training impulse (TRIMP) in team sport players. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2011, 14, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, V.; Iellamo, F.; Impellizzeri, F.; D’Ottavio, S.; Castagna, C. Relation between individualized training impulses and performance in distance runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 2090–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagno, K.M.; Thatcher, R.; van Someren, K.A. A modified TRIMP to quantify the in-season training load of team sport players. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez-Villanueva, A. Tactical Periodization: Mourinho’s Best-kept secret? Soccer J. 2012, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, E.M.; Maughan, R.J. Requirements for ethics approvals. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunicht, P.; Makayed, K.; Meysman, P.; Laukens, K.; Knaepen, L.; Vervoort, Y.; De Bliek, E.; Hens, W.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.; Desteghe, L.; et al. Validation of Polar H10 chest strap and Fitbit Inspire 2 tracker for measuring continuous heart rate in cardiac patients: Impact of artefact removal algorithm. Europace 2023, 25 (Suppl. S1), euad122.550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S. The Heart Rate Monitor Book; Polar Electro Oy: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Seiler, K.S.; Kjerland, G.Ø. Quantifying training intensity distribution in elite endurance athletes: Is there evidence for an “optimal” distribution? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2006, 16, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schielzeth, H. Simple means to improve the interpretability of regression coefficients. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, J.; Kenny, D.A.; Judd, C.M. Statistical power and optimal design in experiments in which samples of participants respond to samples of stimuli. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2014, 143, 2020–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawilowsky, S.S. New effect size rules of thumb. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2009, 8, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, T. The Science of Training—Soccer: A Scientific Approach to Developing Strength, Speed and Endurance, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Weaving, D.; Jones, B.; Ireton, M.; Whitehead, S.; Till, K.; Beggs, C.B. Overcoming the problem of multicollinearity in sports performance data: A novel application of partial least squares correlation analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, H.; Keizer, H.A. Overtraining in Elite Athletes. Sports Med. 1988, 6, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujika, I.; Padilla, S. Detraining: Loss of training-induced physiological and performance adaptations. Part I: Short term insufficient training stimulus. Sports Med. 2000, 30, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, A.; Fuk, A.; Gallo, G.; Gotti, D.; Meloni, A.; La Torre, A.; Filipas, L.; Codella, R. Cardiorespiratory and metabolic consequences of detraining in endurance athletes. Front. Physiol. 2024, 14, 1334766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diouron, I.; Imoussaten, A.; Harispe, S.; Escudier, G.; Dray, G.; Perrey, S. Monitoring of cardiac adaptation in elite soccer players over a season through machine learning. J. Sports Sci. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujika, I.; Padilla, S. Scientific bases for precompetition tapering strategies. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1182–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shushan, T.; Lovell, R.; Buchheit, M.; Scott, T.J.; Barrett, S.; Norris, D.; McLaren, S.J. Submaximal Fitness Test in Team Sports: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Exercise Heart Rate Measurement Properties. Sports Med. Open 2023, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, J.J.; Di Michele, R.; Morgans, R.; Burgess, D.; Morton, J.P.; Drust, B. Seasonal training-load quantification in elite English premier league soccer players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravé, G.; Granacher, U.; Boullosa, D.; Hackney, A.C.; Zouhal, H. How to Use Global Positioning Systems (GPS) Data to Monitor Training Load in the “Real World” of Elite Soccer. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F.M.; Owen, A.; Serra-Olivares, J.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; van der Linden, C.M.I.; Mendes, B. Characterization of the Weekly External Load Profile of Professional Soccer Teams from Portugal and the Netherlands. J. Hum. Kinet. 2019, 66, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-García, A.; Gómez Díaz, A.; Bradley, P.S.; Morera, F.; Casamichana, D. Quantification of a Professional Football Team’s External Load Using a Microcycle Structure. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 3511–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, A.L.; Lago-Peñas, C.; Gómez, M.-Á.; Mendes, B.; Dellal, A. Analysis of a training mesocycle and positional quantification in elite European soccer players. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2017, 12, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, D.B.; Mortimer, L.Á.; Condessa, L.A.; Morandi, R.F.; Oliveira, B.M.; Marins, J.C.B.; Soares, D.D.; Garcia, E.S. Intensity of real competitive soccer matches and differences among player positions. Rev. Bras. Cineantropometria Desempenho Hum. 2011, 13, 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Emmonds, S.; Bower, P.; Weaving, D. External and internal maximal intensity periods of elite youth male soccer matches. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 41, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stølen, T.; Chamari, K.; Castagna, C.; Wisløff, U. Physiology of soccer: An update. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 501–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.S.; Sheldon, W.; Wooster, B.; Olsen, P.; Boanas, P.; Krustrup, P. High-intensity running in English FA Premier League soccer matches. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.S.; Di Mascio, M.; Peart, D.; Olsen, P.; Sheldon, B. High-intensity activity profiles of elite soccer players at different performance levels. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 2343–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingebrigtsen, J.; Dalen, T.; Hjelde, G.H.; Drust, B.; Wisløff, U. Acceleration and sprint profiles of a professional elite football team in match play. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2015, 15, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domene, A. Evaluation of movement and physiological demands of full-back and center-back soccer players using global positioning systems. J. Hum. Sport. Exerc. 2013, 8, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, A.L.; Dunlop, G.; Rouissi, M.; Haddad, M.; Mendes, B.; Chamari, K. Analysis of positional training loads (ratings of perceived exertion) during various-sided games in European professional soccer players. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2016, 11, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abt, G.; Lovell, R. The use of individualized speed and intensity thresholds for determining the distance run at high-intensity in professional soccer. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Season 1 (2023–2024) | Season 2 (2024–2025) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Overall | 37 | 37 |

| CD | 8 | 9 | |

| WD | 7 | 6 | |

| CM | 9 | 11 | |

| FW | 13 | 11 | |

| Age (years) | Overall | 24.0 ± 4.4 | 24.5 ± 5.1 |

| CD | 24.8 ± 5.3 | 24.6 ± 5.3 | |

| WD | 24.3 ± 4.3 | 24.9 ± 4.7 | |

| CM | 23.8 ± 4.8 | 24.4 ± 5.6 | |

| FW | 23.4 ± 4.1 | 24.3 ± 5.5 | |

| Height (cm) | Overall | 181.8 ± 6.6 | 181.0 ± 6.5 |

| CD | 189.1 ± 4.5 | 188.3 ± 5.0 | |

| WD | 180.3 ± 2.6 | 178.2 ± 3.8 | |

| CM | 179.3 ± 6.8 | 178.6 ± 5.3 | |

| FW | 179.7 ± 6.3 | 178.8 ± 5.6 | |

| Body mass (kg) | Overall | 77.0 ± 7.4 | 77.3 ± 7.2 |

| CD | 82.7 ± 7.3 | 83.2 ± 5.3 | |

| WD | 74.0 ± 6.4 | 70.9 ± 3.9 | |

| CM | 74.5 ± 5.8 | 74.3 ± 3.3 | |

| FW | 77.0 ± 7.7 | 78.9 ± 8.7 | |

| Maximal HR (bpm) | Overall | 194.2 ± 9.1 | 196.1 ± 7.5 |

| CD | 186 ± 6.3 | 192.4 ± 9.2 | |

| WD | 194.7 ± 10.2 | 197.7 ± 6.9 | |

| CM | 198.2 ± 8.1 | 197.5 ± 6.3 | |

| FW | 196.2 ± 8.3 | 196.9 ± 7.5 | |

| Modified Intensity Zone | Edwards’ Intensity Zone | Percentage of Maximal Heart Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Low intensity | 1 | 0–40% |

| 2 | 40–60% | |

| 3 | 60–70% | |

| 4 | 70–80% | |

| Moderate intensity | 5 | 80–90% |

| High intensity | 6 | 90–100% |

| Months | Low Intensity | Moderate Intensity | High Intensity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | WD | CM | FW | CD | WD | CM | FW | CD | WD | CM | FW | |

| 1 ** | 1112 ± 417 [362, 1840] | 1077 ± 388 [510, 1667] | 1034 ± 379 [514, 1722] | 1232 ± 507 [362, 1840] | 549 ± 136 [318, 710] | 503 ± 166 [167, 763] | 439 ± 144 [190, 725] | 405 ± 118 [156, 619] | 178 ± 89 [75, 294] | 187 ± 129 [46, 372] | 130 ± 80 [39, 299] | 106 ± 86 [17, 284] |

| 2 * | 833 ± 122 [632, 1030] | 785 ± 139 [548, 956] | 907 ± 164 [516, 1154] | 946 ± 153 [715, 1200] | 274 ± 66 [181, 363] | 269 ± 90 [128, 374] | 227 ± 89 [78, 368] | 190 ± 84 [40, 323] | 54 ± 31 [10, 93] | 88 ± 60 [32, 203] | 45 ± 58 [0, 223] | 36 ± 42 [0, 126] |

| 3 | 661 ± 247 [342, 968] | 607 ± 126 [450, 812] | 946 ± 170 [679, 1209] | 834 ± 265 [373, 1185] | 242 ± 91 [117, 394] | 283 ± 106 [155, 401] | 267 ± 62 [180, 345] | 249 ± 78 [183, 411] | 81 ± 61 [2, 177] | 108 ± 64 [21, 185] | 65 ± 67 [4, 241] | 80 ± 69 [5, 238] |

| 4 | 626 ± 66 [543, 712] | 696 ± 135 [419, 895] | 862 ± 216 [448, 1155] | 869 ± 140 [612, 1041] | 255 ± 92 [104, 327] | 356 ± 144 [181, 554] | 313 ± 84 [227, 529] | 315 ± 94 [159, 483] | 93 ± 64 [3, 166] | 11 ± 75 [21, 279] | 66 ± 60 [8, 228] | 78 ± 83 [8, 280] |

| 5 | 664 ± 151 [505, 837] | 679 ± 182 [393, 990] | 852 ± 194 [414, 1137] | 839 ± 181 [514, 1152] | 270 ± 140 [98, 486] | 305 ± 118 [91, 428] | 258 ± 94 [127, 445] | 275 ± 82 [164, 409] | 103 ± 54 [21, 164] | 82 ± 53 [5, 154] | 38 ± 27 [5, 82] | 63 ± 67 [9, 217] |

| 6 | 553 ± 126 [407, 827] | 586 ± 111 [438, 772] | 781 ± 162 [584, 1072] | 706 ± 128 [407, 827] | 256 ± 75 [129, 350] | 227 ± 94 [108, 384] | 215 ± 66 [123, 323] | 256 ± 105 [128, 489] | 80 ± 60 [5, 179] | 54 ± 31 [8, 86] | 24 ± 23 [2, 79] | 43 ± 37 [1, 104] |

| 7 | 737 ± 217 [406, 1100] | 834 ± 215 [524, 1117] | 1060 ± 151 [785, 1318] | 797 ± 170 [477, 1070] | 314 ± 102 [145, 500] | 203 ± 103 [83, 333] | 282 ± 116 [104, 476] | 239 ± 103 [76, 477] | 80 ± 59 [38, 231] | 22 ± 16 [8, 39] | 38 ± 37 [4, 138] | 53 ± 56 [1, 182] |

| 8 | 620 ± 33 [579, 655] | 822 ± 106 [648, 1028] | 956 ± 99 [772, 1083] | 830 ± 117 [685, 1012] | 319 ± 95 [173, 404] | 325 ± 100 [160, 452] | 261 ± 74 [177, 387] | 260 ± 91 [171, 410] | 79 ± 87 [15, 225] | 75 ± 50 [8, 142] | 45 ± 49 [3, 170] | 46 ± 36 [9, 123] |

| 9 | 645 ± 202 [438, 990] | 649 ± 142 [487, 810] | 876 ± 151 [588, 1110] | 799 ± 164 [456, 984] | 277 ± 119 [81, 442] | 282 ± 115 [155, 458] | 269 ± 83 [151, 420] | 229 ± 98 [121, 427] | 90 ± 68 [0, 173] | 82 ± 49 [27, 164] | 50 ± 53 [9, 199] | 36 ± 28 [8, 83] |

| 10 | 833 ± 187 [639, 1180] | 887 ± 154 [569, 1059] | 1010 ± 216 [686, 1325] | 905 ± 199 [505, 1157] | 344 ± 67 [279, 480] | 326 ± 79 [196, 409] | 278 ± 85 [143, 438] | 235 ± 84 [134, 401] | 62 ± 60 [15, 196] | 82 ± 52 [18, 174] | 36 ± 41 [0, 130] | 25 ± 18 [8, 58] |

| 11 | 559 ± 94 [459, 676] | 561 ± 113 [446, 774] | 673 ± 105 [435, 782] | 607 ± 92 [501, 669] | 170 ± 21 [149, 196] | 175 ± 57 [74, 227] | 140 ± 47 [59, 201] | 138 ± 28 [106, 155] | 37 ± 26 [15, 70] | 57 ± 57 [1, 167] | 25 ± 25 [0, 77] | 15 ± 3 [12, 17] |

| Zone | Match (min) | Training (min) | Difference (min) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low intensity | 73.7 | 248.2 | 174.5 | 3.4 |

| Moderate intensity | 51.8 | 78.3 | 26.5 | 1.5 |

| High intensity | 25.0 | 17.3 | −7.7 | 0.7 |

| Field Position | Low Intensity | Moderate Intensity | High Intensity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (min) | Intensity (%) | Volume (min) | Intensity (%) | Volume (min) | Intensity (%) | |

| CD | 30.2 ± 10.0 [6.65, 63.4] | 30.4 ± 9.9 [6.9, 63.9] | 46.2 ± 7.5 [28.4, 62.8] | 46.7 ± 7.4 [27.7, 65.7] | 22.1 ± 12.3 [0.0, 60.0] | 22.4 ± 12.5 [0.0, 62.4] |

| WD | 25.4 ± 9.2 [3.5, 51.5] | 25.8 ± 9.4 [3.6, 52.5] | 44.8 ± 6.7 [21.6, 65.7] | 45.5 ± 7.0 [22.4, 67.7] | 28.3 ± 11.6 [5.6, 71.0] | 28.6 ± 11.7 [5.7, 73.9] |

| CM | 22.5 ± 8.8 [8.2, 45.2] | 22.9 ± 9.0 [8.4, 47.0] | 47.4 ± 7.1 [28.7, 66.0] | 48.3 ± 7.2 [28.8, 66.1] | 28.2 ± 12.5 [6.3, 56.4] | 28.7 ± 12.7 [6.7, 56.6] |

| FW | 33.0 ± 10.6 [13.7, 54.2] | 33.6 ± 10.6 [14.3, 55.3] | 44.4 ± 7.8 [31.5, 60.5] | 45.3 ± 8.1 [30.1, 63.1] | 20.5 ± 9.3 [2.9, 41.4] | 20.9 ± 9.5 [3.1, 42.4] |

| Overall | 27.3 ± 10.3 [3.5, 36.4] | 27.6 ± 10.3 [3.6, 63.9] | 45.9 ± 7.3 [21.6, 66.0] | 46.7 ± 7.4 [22.4, 67.7] | 25.1 ± 12.2 [0.0, 71.0] | 25.5 ± 12.4 [0.0, 73.9] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diouron, I.; Leduc, C.; Escudier, G.; Perrey, S. Exercise Heart Rate During Training and Competitive Matches in Elite Soccer: More Questions than Answers. Sports 2025, 13, 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120441

Diouron I, Leduc C, Escudier G, Perrey S. Exercise Heart Rate During Training and Competitive Matches in Elite Soccer: More Questions than Answers. Sports. 2025; 13(12):441. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120441

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiouron, Iwen, Cédric Leduc, Guilhem Escudier, and Stéphane Perrey. 2025. "Exercise Heart Rate During Training and Competitive Matches in Elite Soccer: More Questions than Answers" Sports 13, no. 12: 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120441

APA StyleDiouron, I., Leduc, C., Escudier, G., & Perrey, S. (2025). Exercise Heart Rate During Training and Competitive Matches in Elite Soccer: More Questions than Answers. Sports, 13(12), 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120441