Rainfall-Induced Landslide Prediction Models, Part I: Empirical–Statistical and Physically Based Causative Thresholds

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Study | Content |

|---|---|

| Zhang et al. [12] * | Geotechnical and hydrological concepts related to rainfall-triggered landslides |

| Chae et al. [20] * | Landslide susceptibility, modeling of runout, monitoring, and early warning systems |

| Segoni et al. [21] * | Rainfall-based landslide thresholds |

| Merghadi et al. [22] * | Application of machine learning algorithms for assessing landslide susceptibility |

| Shano et al. [23] * | Overview of various prediction methods, emphasizing statistical models |

| Yanbin et al. [24] * | Use of machine learning techniques in landslide susceptibility analysis |

| Zou & Zheng [25] ** | Scientometric review, limited physical prediction models, and case studies |

| Huang et al. [26] *** | Landslide susceptibility models based on Geographic Information System (GIS) data |

| Petrucci [27] * | Analysis of the main causes behind landslide-related fatalities |

| Vung et al. [28] * | Exploration of challenges, opportunities, and future research directions for rainfall-induced landslides |

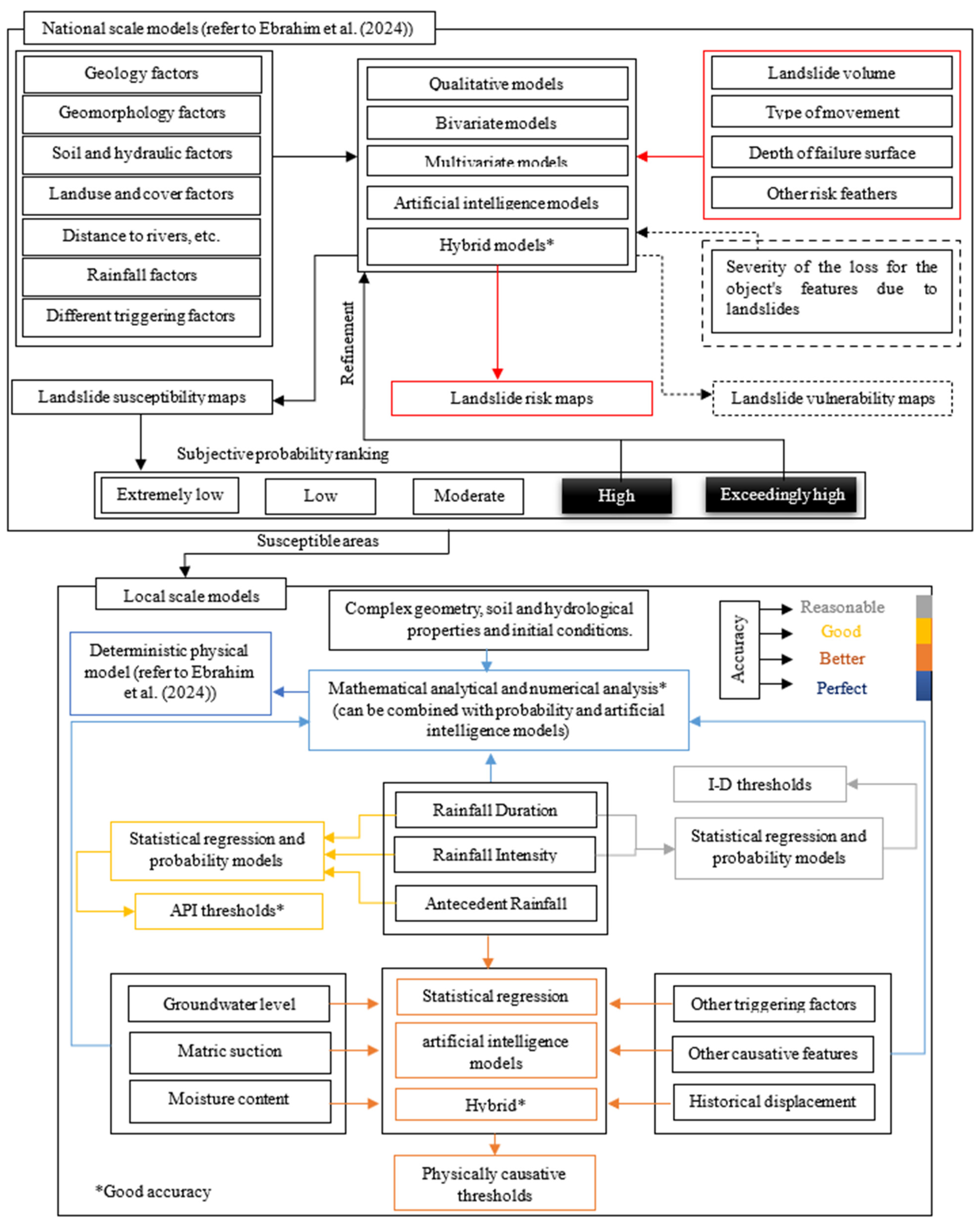

| Ebrahim et al. [19] * | Deterministic and susceptibility-based landslide prediction models |

| Ebrahim et al. [29] * | Time series-based prediction models for landslides |

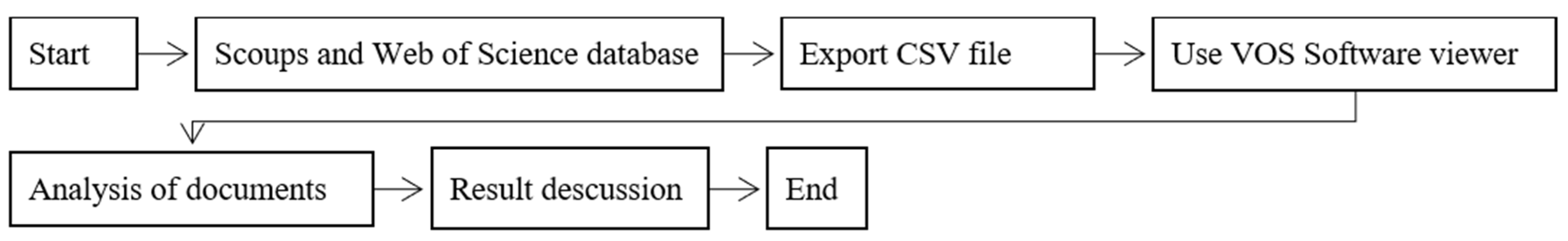

2. Methodology of the Study

2.1. Search Strategy Design

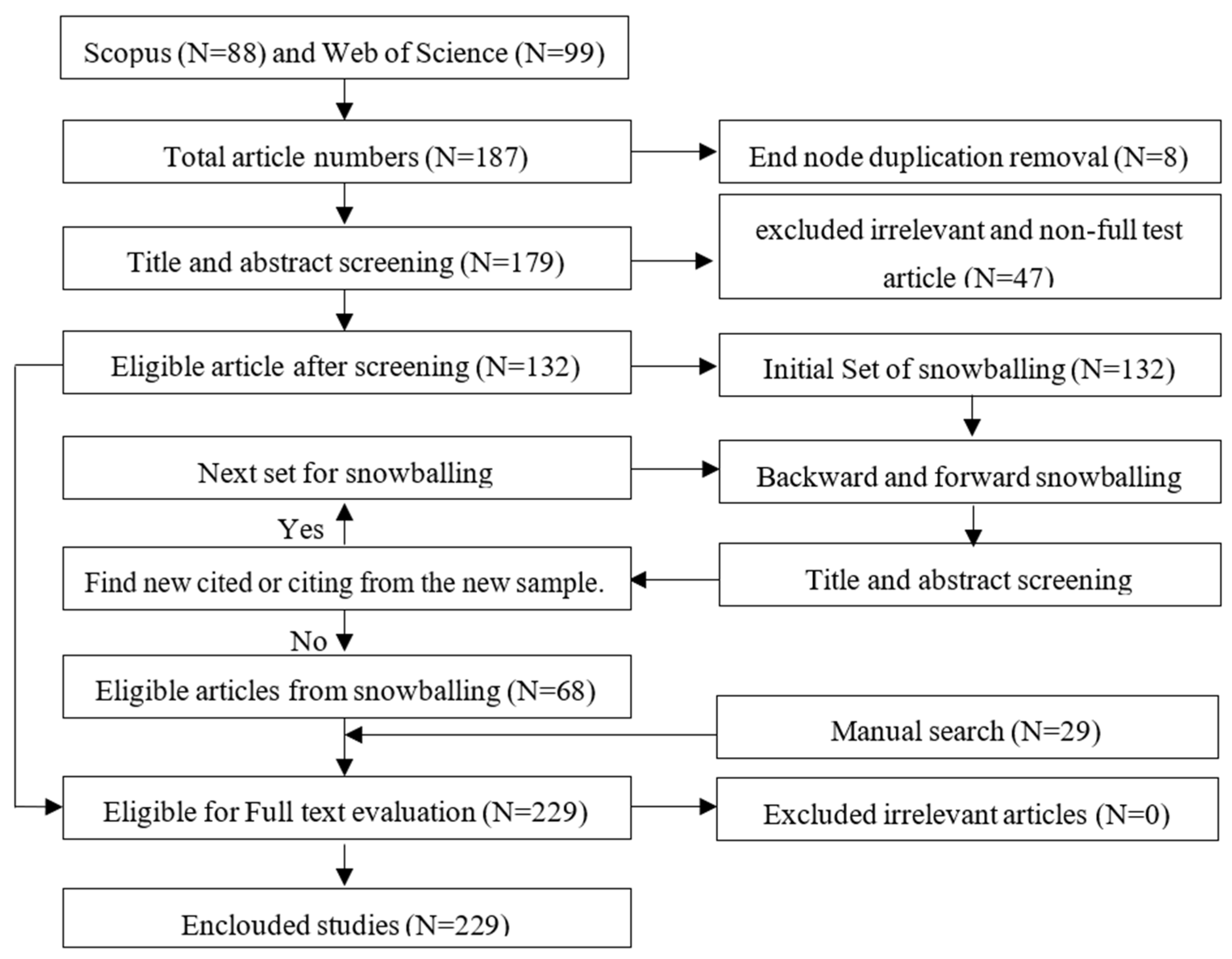

2.2. Database Selection and Search Execution

2.3. Screening and Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Screening and Assessment of Collected Articles

2.5. Limitations of the Methodology

3. Scientometric Analysis

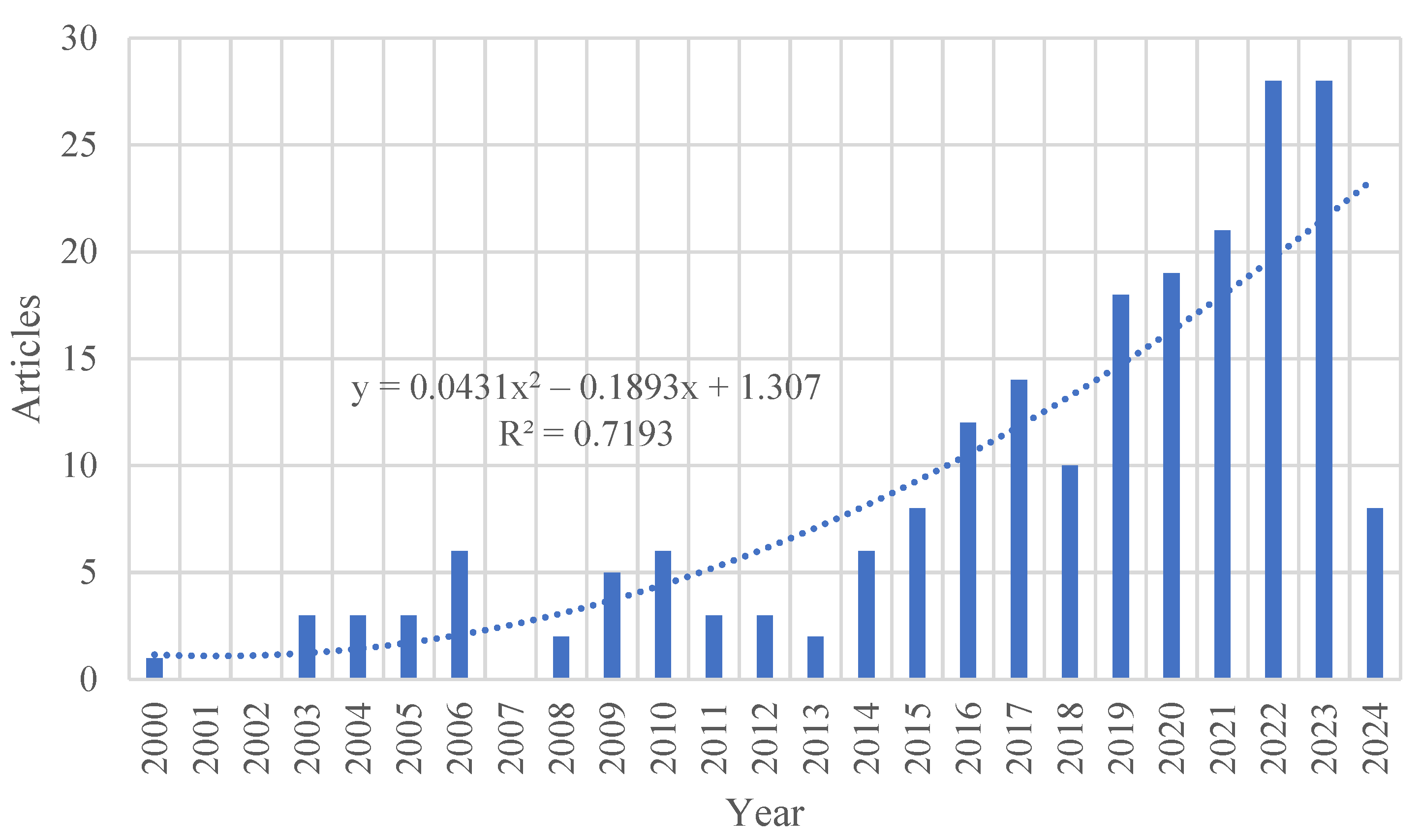

3.1. The Trend in Annual Publications for Landslide Prediction

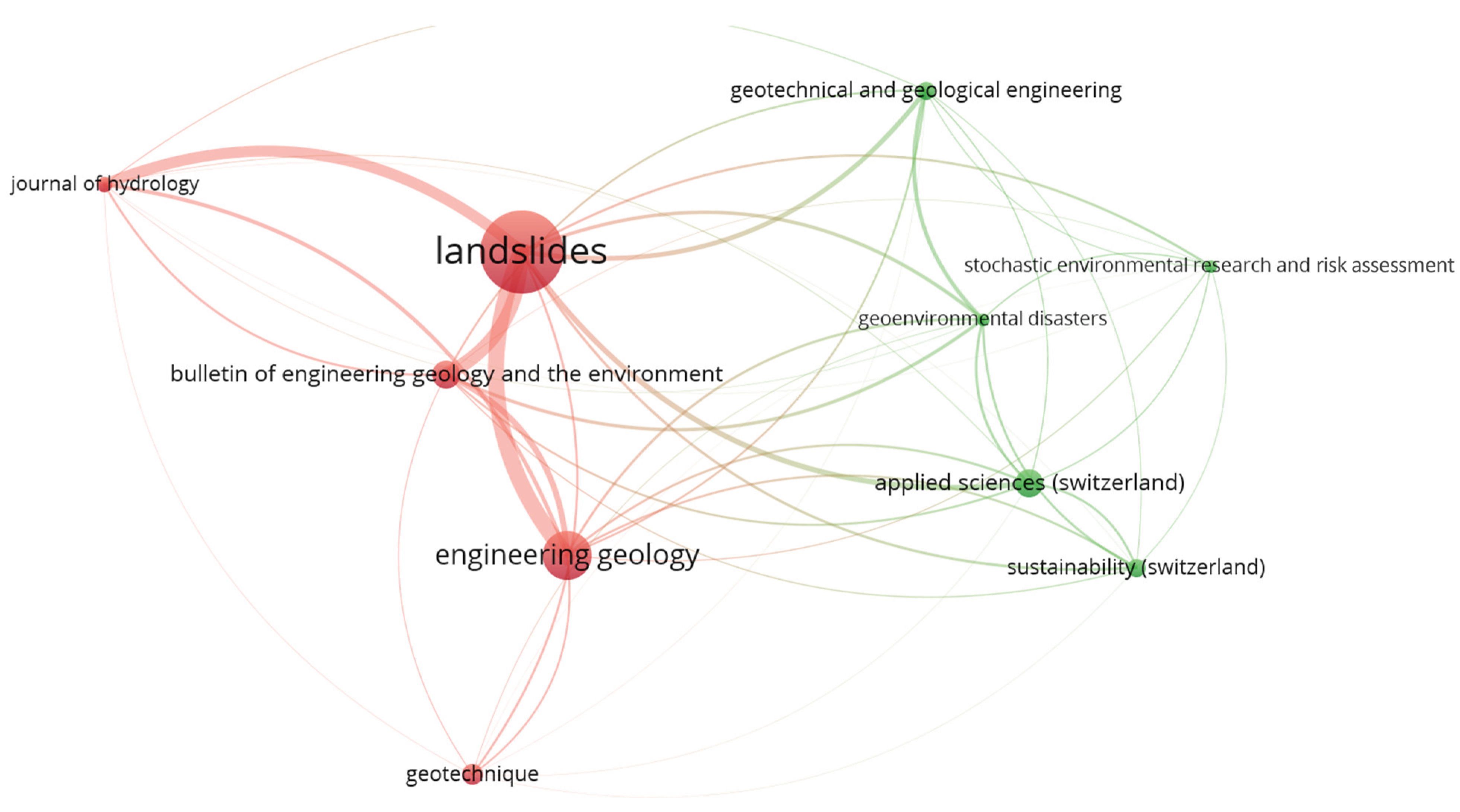

3.2. Leading Journals in Landslide Prediction Contributions

3.3. Active Nations in Landslide Prediction

3.4. Article Co-Citation Analysis in Landslide Prediction

| Author | Article | Journal | Citation | NS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Merghadi et al. [22] | Machine learning methods for landslide susceptibility studies: A comparative overview of algorithm performance | Earth-Science Reviews | 603 | 8.20 |

| Soga et al. [37] | Trends in large-deformation analysis of landslide mass movements with particular emphasis on the material point method | Géotechnique | 383 | 5.80 |

| Froude & Petley [3] | Global fatal landslide occurrence from 2004 to 2016 | Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences | 1164 | 5.62 |

| Ebrahim et al. [33] | Recent Phenomenal and Investigational Subsurface Landslide Monitoring Techniques: A Mixed Review | Remote Sensing | 7 | 4.90 |

| Hungr et al. [6] | The Varnes classification of landslide types, an update | Landslides | 2274 | 4.32 |

| Ikram et al. [38] | A novel swarm intelligence: cuckoo optimization algorithm (COA) and SailFish optimizer (SFO) in landslide susceptibility assessment | Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment | 37 | 4.16 |

| Zhang et al. [39] | Application of an enhanced BP neural network model with water cycle algorithm on landslide prediction | Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment | 140 | 3.50 |

| Mondini et al. [40] | Deep learning forecast of rainfall-induced shallow landslides | Nature communications | 31 | 3.49 |

| Chae et al. [20] | Landslide prediction, monitoring and early warning: a concise review of state-of-the-art | Geosciences Journal | 267 | 3.03 |

| Long et al. [41] | A multi-feature fusion transfer learning method for displacement prediction of rainfall reservoir-induced landslide with step-like deformation characteristics | Engineering Geology | 47 | 2.94 |

3.5. Keyword Co-Occurrence Mapping in Landslide Prediction

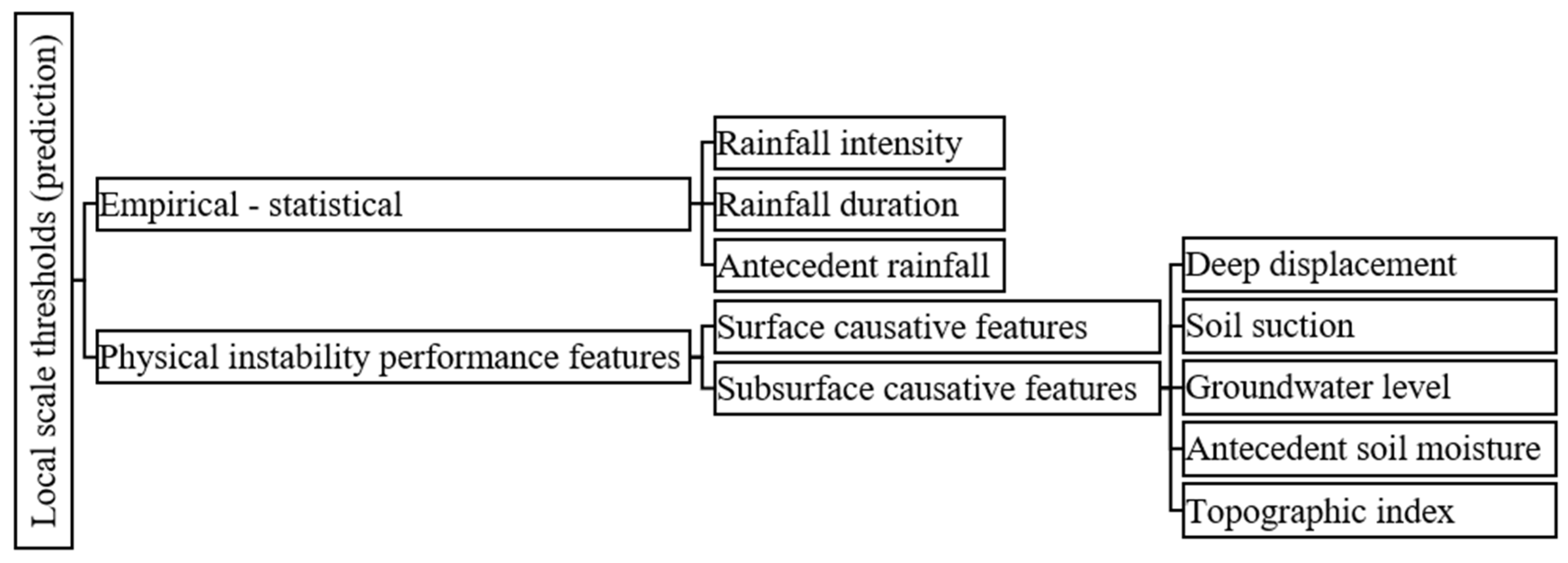

4. Systematic Review

4.1. Empirical–Statistical I-D Thresholds

4.1.1. Intensity–Duration Thresholds

4.1.2. Antecedent Rainfall Thresholds

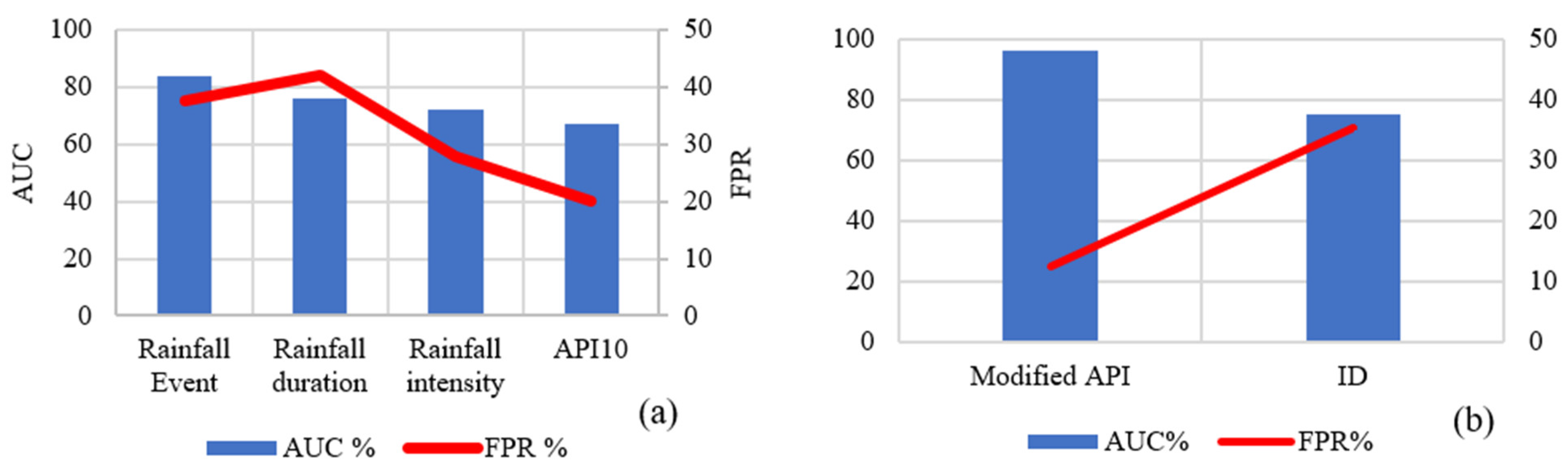

4.1.3. I-D Thresholds Prediction Accuracy

4.2. Physically Based Causative Thresholds and Prediction

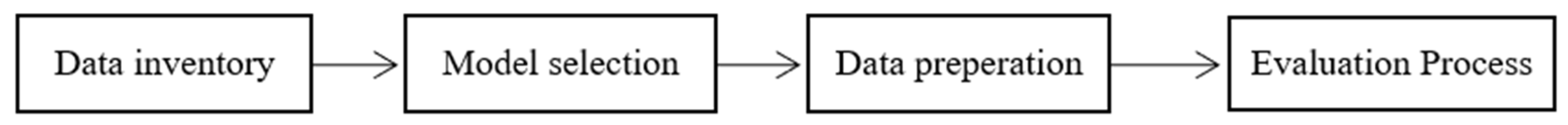

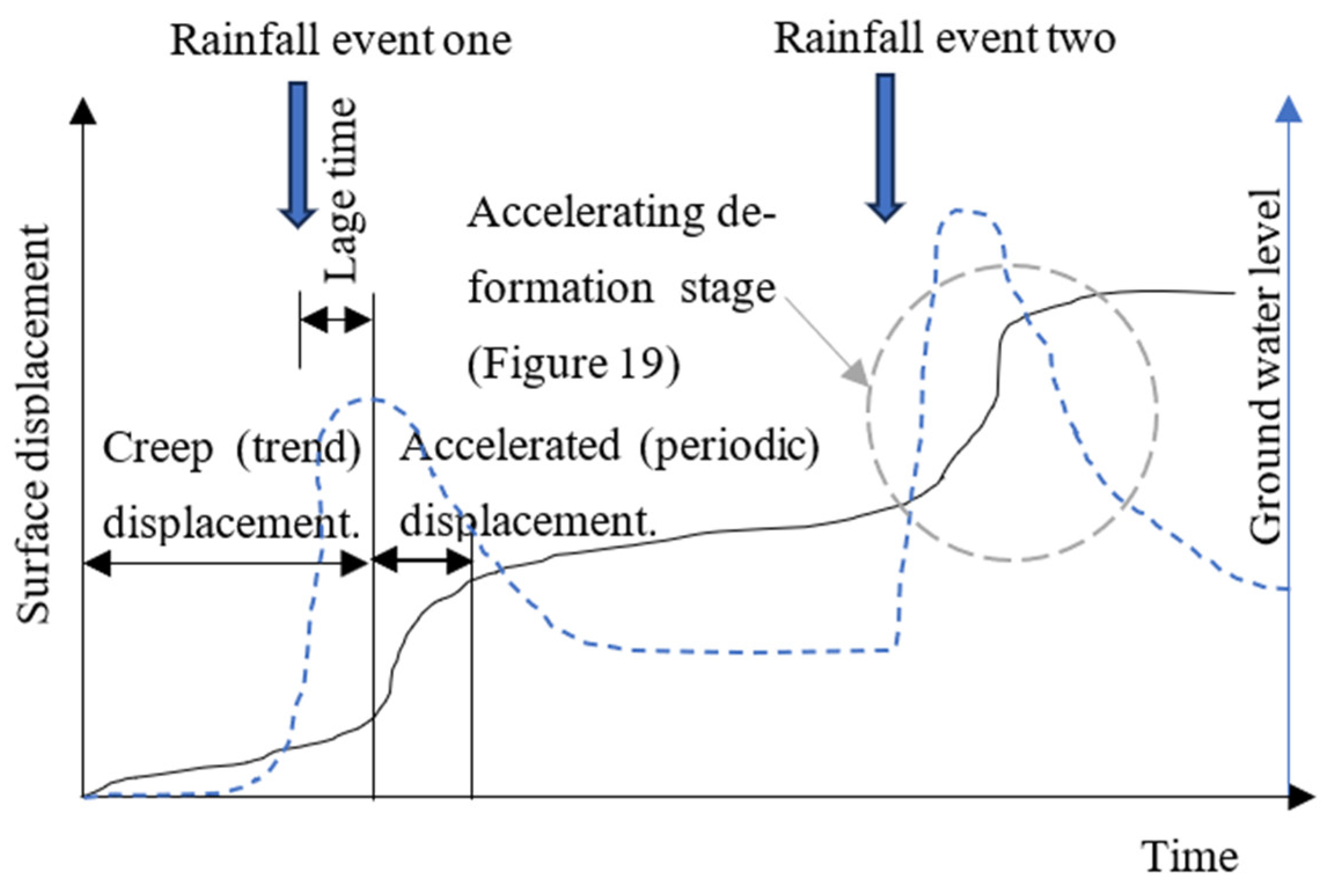

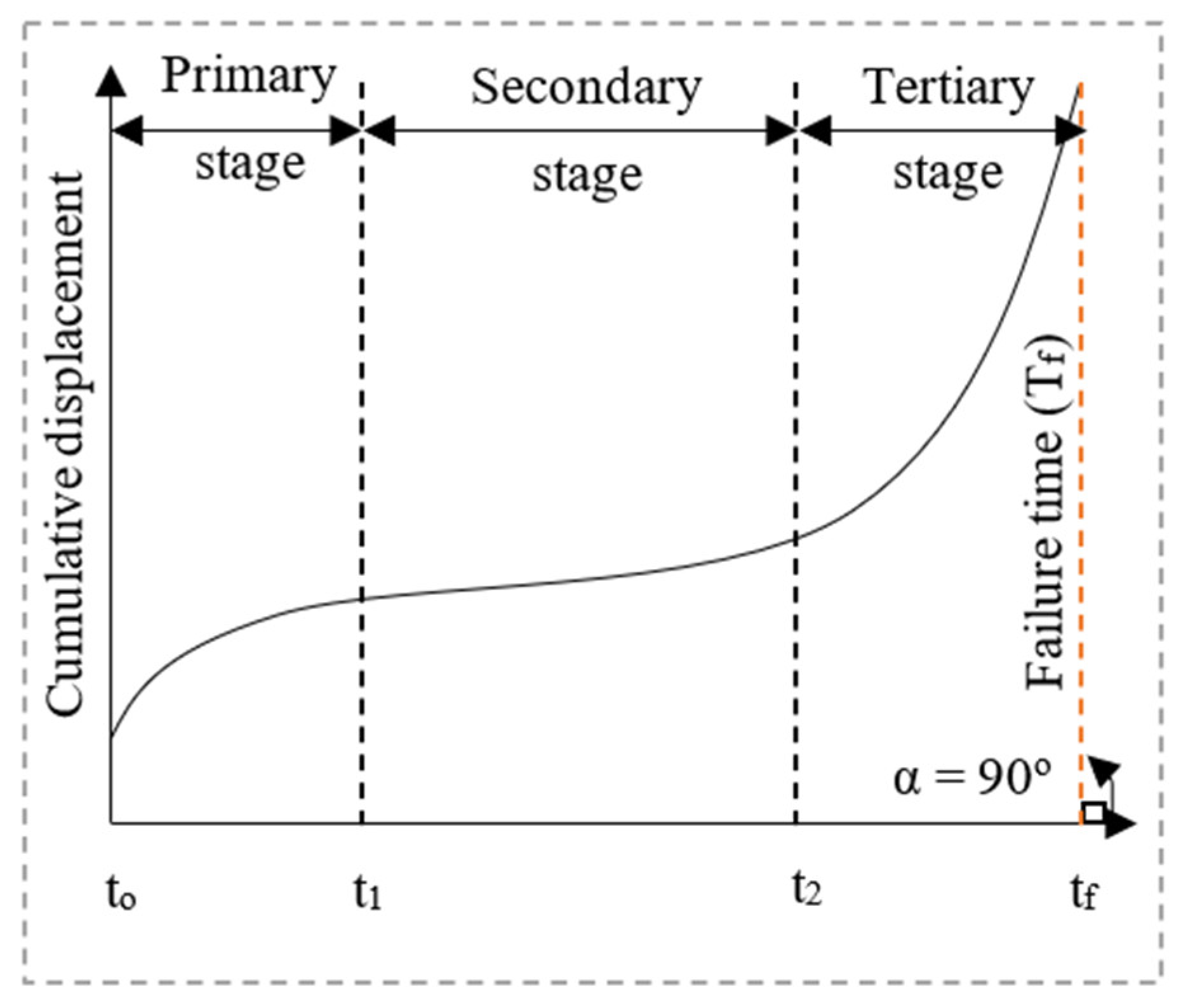

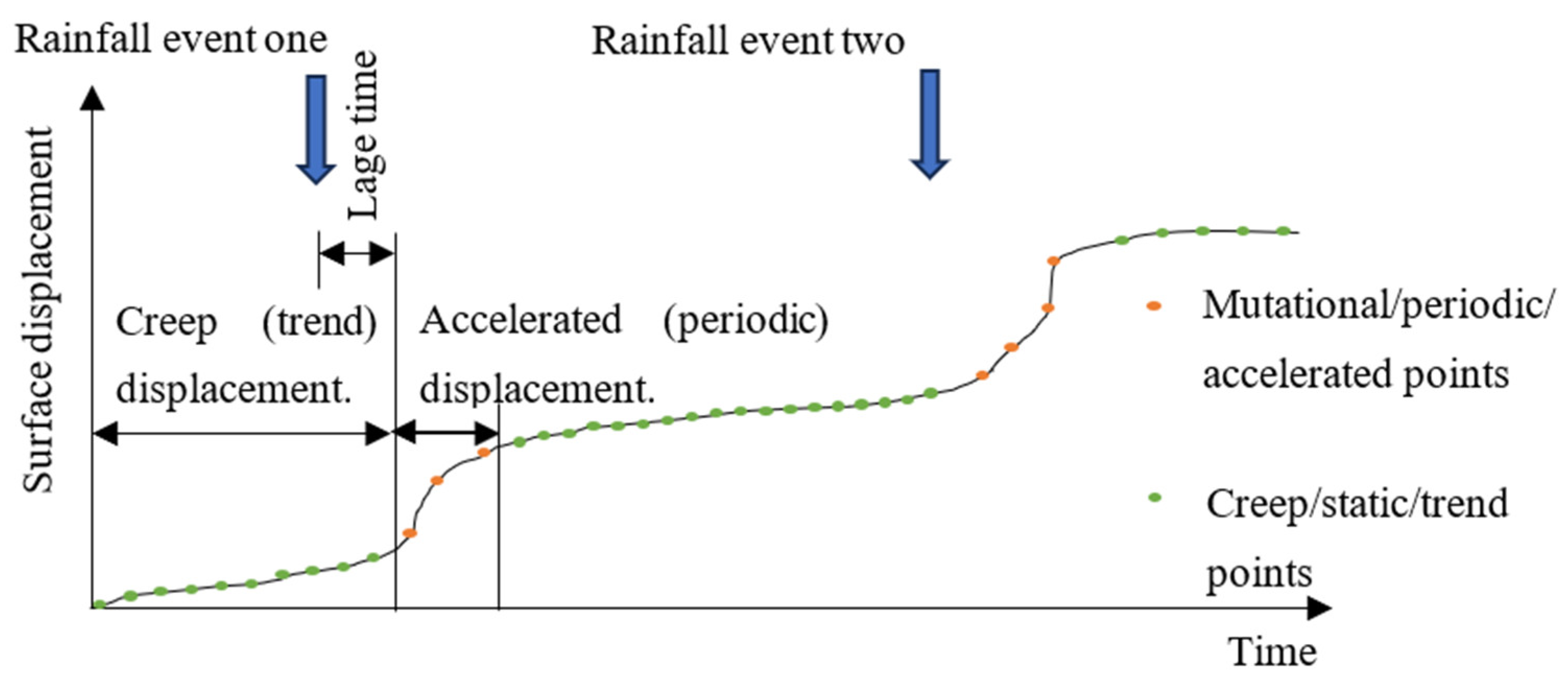

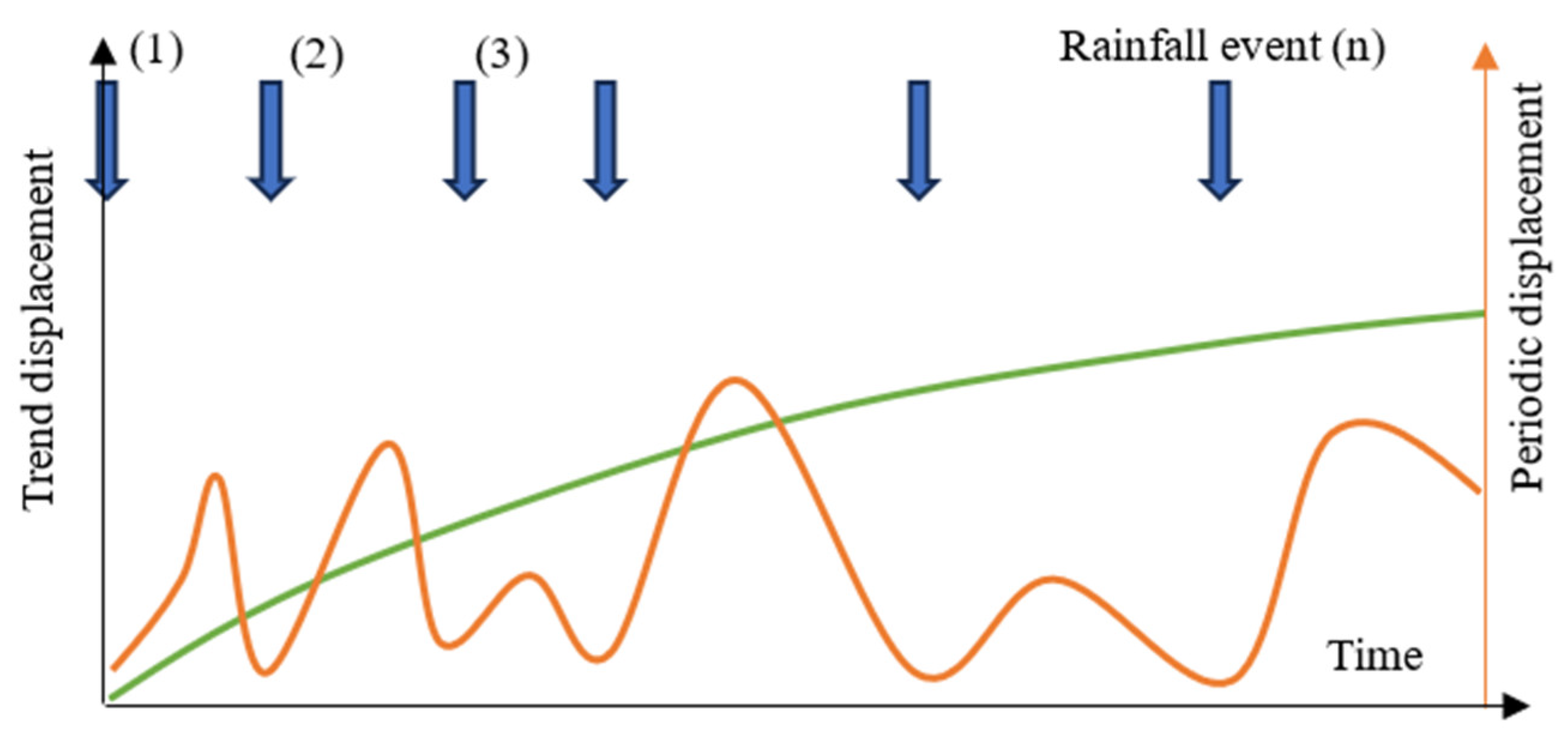

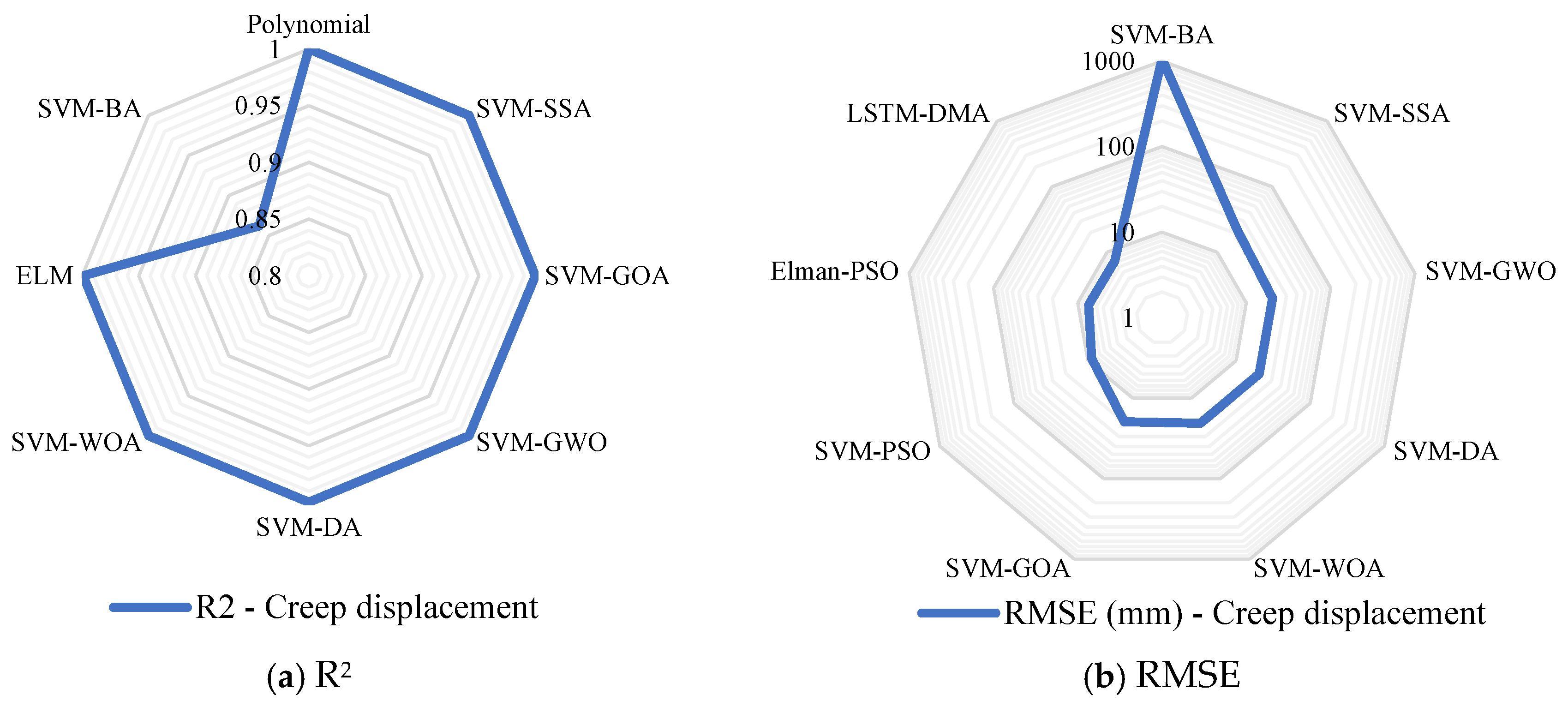

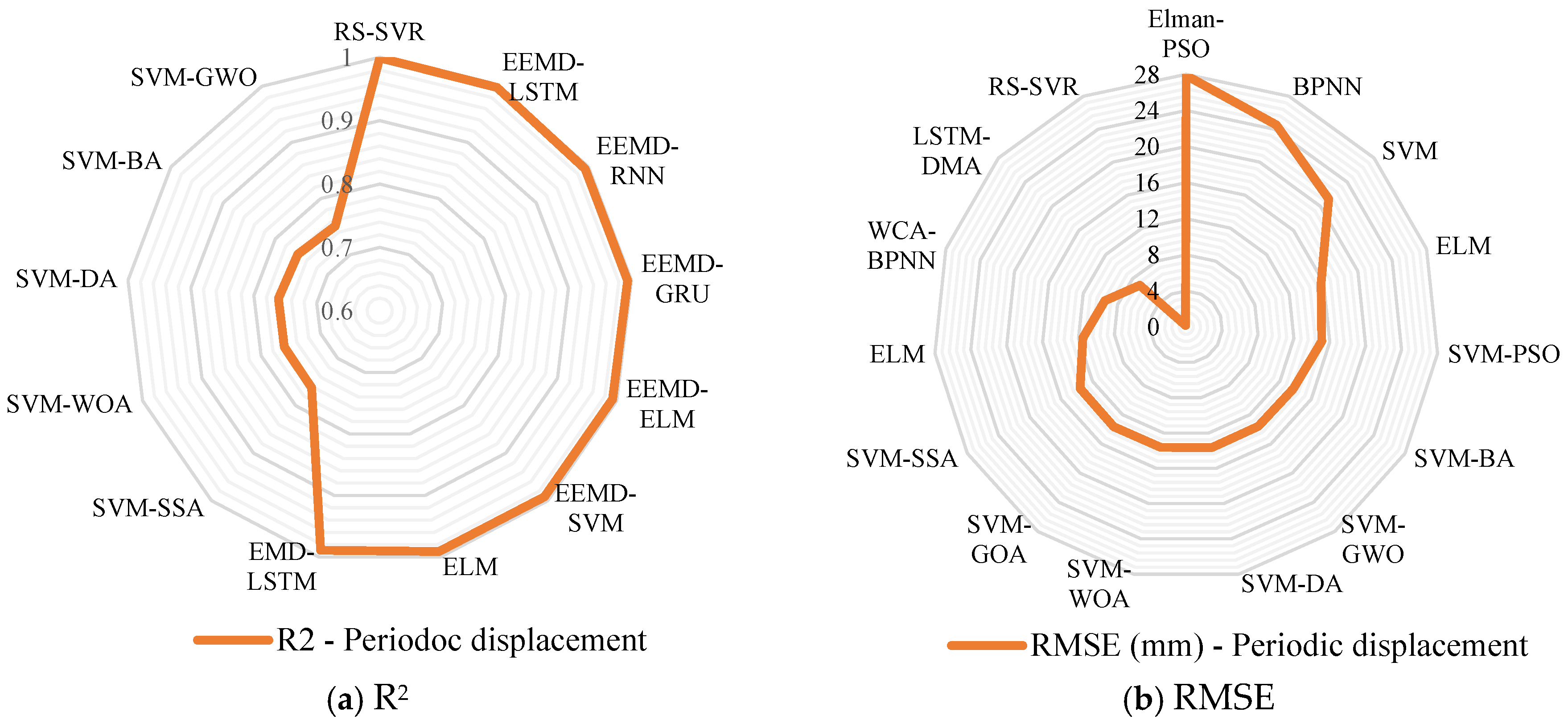

4.2.1. Displacement Instability Performance and Prediction

- 1.

- Data inventory and input model parameters

- 2.

- Model selection

- 3.

- Model decomposition and data preparation

- 4.

- Training and testing data split ratio

- 5.

- Missing data and training data shortage

- 6.

- Regression performance evaluation

- 7.

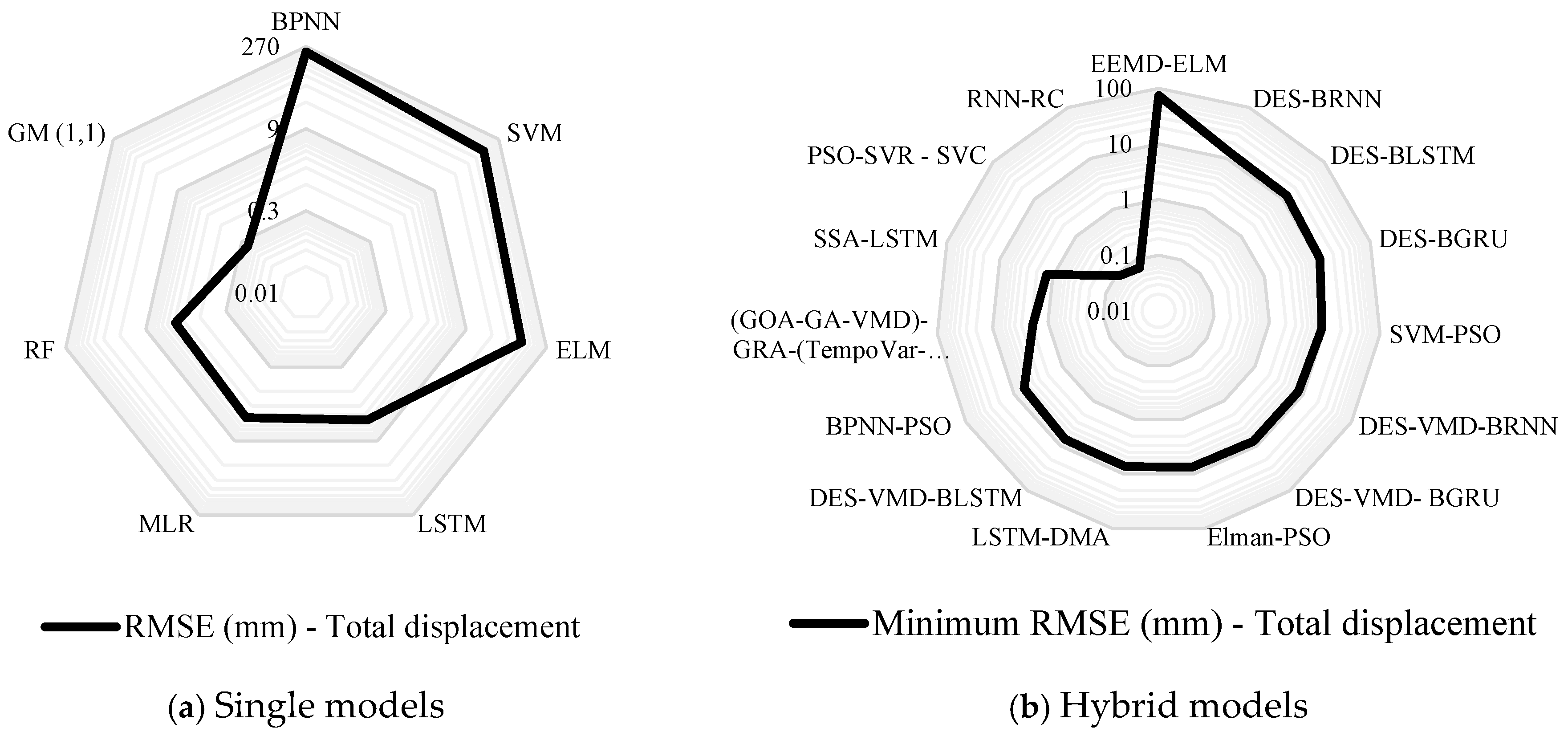

- Displacement models’ prediction accuracy

| Study | Key Features | Model with the Best Accuracy | Sampling Ratio (Training: Testing) | Model Performance: (R2) 1, RMSE (mm) 2, MAPE% 3, MSE (mm2) 4, Minimum Error% 5, Maximum Error % 6, MAE (mm) 7, MAPE (mm) 8 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Neaupane and Achet [92]; Yao et al. [69]; Cao et al. [76]; Liu et al. [78]; Krkač et al. [73]; Krkač et al. [83]; Li et al. [70]; Yang et al. [93]) |

| Creep | Periodic | Decomposition |

| Creep displacement | Periodic displacement |

| BPNN | - | 0.891 1 | |||||

| ELM | - | 0.984 1 | |||||

| RF | - | 0.998 1 2.56 2 | |||||

| MLR | - | 3.06 2 | |||||

| KGM | - | 0.9998 1 | |||||

| RNN-RC | 0.07 2 0.04 3 | ||||||

| BPNN-PSO | - | 38.4 4 | |||||

| SSA-LSTM | - | 0.965 1 1.307 2 | |||||

| (Lian et al. [68]; Gao et al. [80]; Xing et al. [79]; Niu et al. [67]; Zhang et al. [39]; Zhang et al. [71]; Han et al. [74]; Wang et al. [82]; Wang et al. [72]; Ye et al. [94]) | PSO-SVR | SVC | 0.08827 2 0.02105 8 | ||||

| DES | VMD-BLSTM | DES-BDNN | 0.983 1 7.224 2 | ||||

| GM (1,1) | ENN | - | 0.2 5 | 9.73 6 | |||

| ELM | RS-SVR | - | 0.9991 1 | 0.9991 1 0.1993 2 | |||

| Polynomial | WCA-BPNN | High Pass (HP) filter | >0.991 | 40.60 3 9.47 2 | |||

| LSTM-DMA | DMA | 7.28 2 6.02 7 | 6.92 2 5.7 3 | ||||

| EEMD-ELM | EEMD | 74.00 2 | 2.3944 3 | ||||

| Polynomial | EEMD-LSTM | EEMD and the kurtosis criterion | 1 1 | 0.998 1 0.25 3 | |||

| SVM-SSA | CEEMD | 0.9998 1 22.766 4 | 0.762 1 13.589 2 | ||||

| GRA-TempoVar-Transformer | GOA-GA-VMD | 1.86 2 4.85 7 | |||||

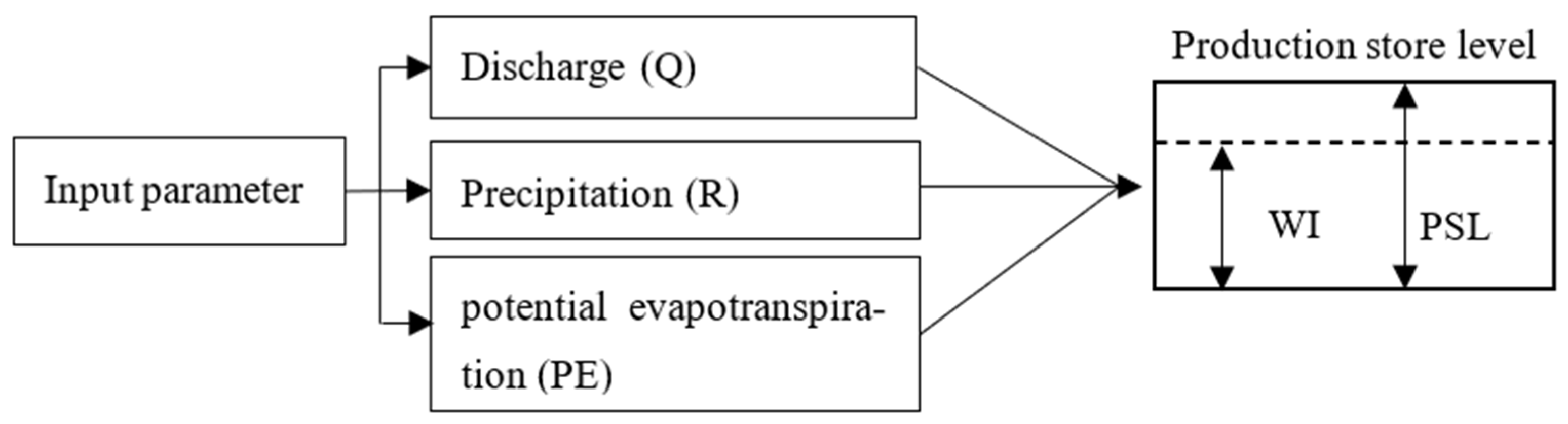

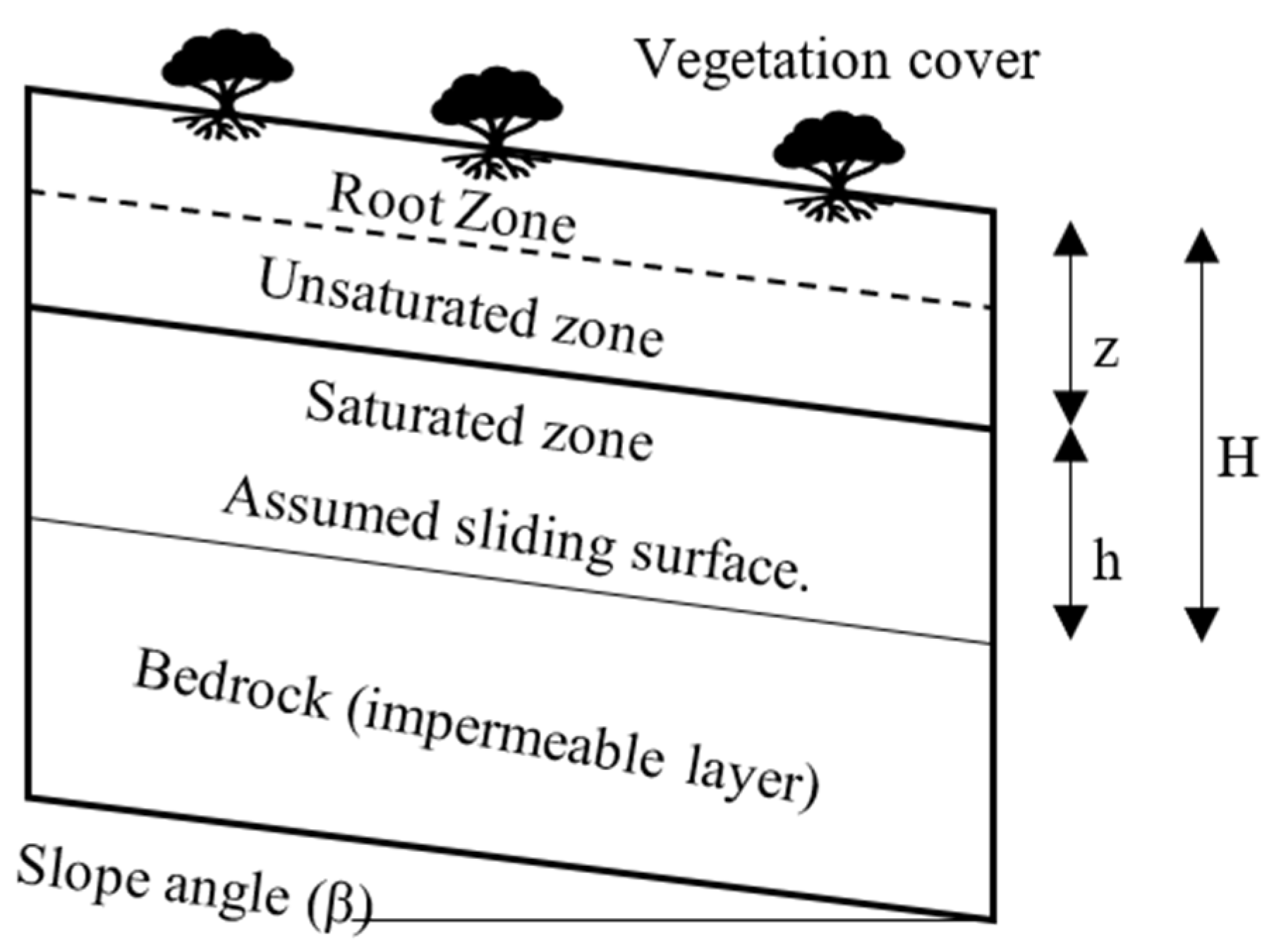

4.2.2. Matric Suction and Groundwater Prediction

4.2.3. Moisture Content and Topographic Thresholds

5. Discussion

5.1. Synthesis of Findings and Comparative Analysis of Model Approaches

5.2. Consolidating Fragmented Knowledge

6. Conclusions

7. Future Directions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Notation and Abbreviations

| Notation | |||

| D | Rainfall duration | ε | Scaling parameter |

| I | Rainfall intensity | ζ | Shape parameter |

| EN | Rainfall event, | υ | Dimensionless parameter |

| APIN | Antecedent precipitation index | Yi | Value of real data |

| N | Number of rainy days | Xi | Value of predicted data |

| Ra | Antecedent rainfall | C | Cohesion |

| Ro | Rolling rainfall | ϕ | Internal friction angle |

| R | Cumulative rainfall | Q | Discharge |

| PE | Potential evaporation | g | Gravitational acceleration |

| S | Displacement | γw | The unit weight of water |

| Ξ (t) | Gamma-type transfer function | γt | Wet unit weight |

| t | time | H | Thickness above the bedrock layer |

| T | Temporal scale/Time intervals | z | Unsaturated thickness |

| M | Temporal memory | h | Saturated thickness |

| Abbreviations | |||

| EWS | Early warning systems | GRU | Gated recurrent unit |

| FLaIR | Forecasting of Landslides Induced by Rainfall | BRNN | Bayesian recurrent neural network |

| GFM | Generalized FLaIR model | BLSTM | Bayesian long short-term memory network |

| IETDs | Inter-event time definitions | BGRU | Bayesian gated recurrent unit network |

| SMS | Soil matric suction | BDNN | Bayesian deep neural networks |

| VSMC | Volumetric soil moisture content | EMD | Empirical mode decomposition |

| PSL | Production storage level | EEMD | Ensemble empirical mode decomposition |

| WI | Wetness increase | CEEMD | Complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition |

| TWI | Topographic Witness Index | DMA | Double moving average |

| SWI | Soil wetness index | SMA | Single moving average |

| SHETRAN | Système Hydrologique Européen TRANsport | DES | Double exponential smoothing |

| AUC | The area under the ROC curve | VMD | Variational mode decomposition |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic | KGM | Kernel-based gray model |

| FPR | False positive rate | MKGM | Multi-kernel gray model |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination | WMKGM | Weighted multi-kernel gray model |

| RMSE | Root mean square error | WCA | Water cycle algorithm |

| MSE | Mean square error | MSI | Multiple Swarm intelligence |

| MAE | Mean absolute error | BA | Bat algorithm |

| SDR | Standard deviation ratio | GWO | Gray wolf optimization |

| PRC | Pearson-R correlation | DA | Dragonfly optimization algorithm |

| GM | Gray model | WOA | Whale optimization algorithm |

| MLR | Multilinear regression | GOA | Grasshopper optimization algorithm |

| ANN | Artificial neural networks | SSA | Sparrow search algorithm |

| BPNN | Backpropagation neural networks | PCA | Principal component analysis |

| SVM | Support vector mechanism | FOBGM | Feedback optimization background gray model |

| RF | Random forest model | MLATC | Mean-based low-rank autoregressive tensor completion |

| SVC | Support vector classifier | MFTL | Multi-fusion transfer learning |

| SVR | Support vector regression | NWE | Non-uniform weight error |

| RS | Random Search | BR-BP | Bayesian regularization backpropagation |

| RNN | Recurrent neural networks | BOA | Butterfly Optimization Algorithm |

| ENN | Evolutionary neural network | GA | Genetic algorism |

| ELM | Extreme learning machine | GPR | Gaussian process regression |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory | GRA | Gray correlation analysis |

| GA | Genetic algorithm | ||

References

- Cruden, D.M. A simple definition of a landslide. Bull. Int. Assoc. Eng. Geol. 1991, 43, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, B.G.; Wu, Y.H.; Liu, K.F.; Choi, J.; Park, H.J. Simulation of debris-flow runout near a construction site in Korea. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froude, M.J.; Petley, D.N. Global fatal landslide occurrence from 2004 to 2016. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 2161–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Steger, S.; Pittore, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Jiang, T.; Wang, Y. Evaluation of potential changes in landslide susceptibility and landslide occurrence frequency in China under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 158049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman Quintero, D.C.; Marino, P.; Abdullah, A.; Santonastaso, G.F.; Greco, R. Large-scale assessment of rainfall-induced landslide hazard based on hydrometeorological information: Application to Partenio Massif (Italy). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 25, 2679–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungr, O.; Leroueil, S.; Picarelli, L. The Varnes classification of landslide types, an update. Landslides 2014, 11, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, R.; Li, X. Hydro-Mechanical Analysis of Rainfall-Induced Landslides; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsa, H.; Anistia, M.H.; Mulsandi, A.; Suprihadi, B.; Kurniawan, R.; Habibie, M.N.; Hutapea, T.D.; Swarinoto, Y.S.; Makmur, E.E.S.; Fitria, W.; et al. Machine learning and artificial intelligence models development in rainfall-induced landslide prediction. IAES Int. J. Artif. Intell. 2023, 12, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Patwa, D.; Bharat, T.V. Influencing factors on the simulation of rainfall-induced landslide prediction based on case study. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, N.V.; Wakai, A.; Sato, G.; Viet, T.T.; Kitamura, N. Simple Method for Shallow Landslide Prediction Based on Wide-Area Terrain Analysis Incorporated with Surface and Subsurface Flows. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2022, 23, 04022028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, N. The rainfall intensity-duration control of shallow landslides and debris flows. Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 1980, 62, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.M.; Tang, W.H. Stability analysis of rainfall-induced slope failure: A review. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Geotech. Eng. 2011, 164, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ju, N.P.; Liao, Y.J.; Liu, D.D. Determination of rainfall thresholds for shallow landslides by a probabilistic and empirical method. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 15, 2715–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Koo, R.C.; Kwan, J.S. Development of a slope digital twin for predicting temporal variation of rainfall-induced slope instability using past slope performance records and monitoring data. Eng. Geol. 2022, 308, 106825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formetta, G.; Capparelli, G. Quantifying the three-dimensional effects of anisotropic soil horizons on hillslope hydrology and stability. J. Hydrol. 2019, 570, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; He, Z. Rainfall-oriented resilient design for slope system: Resilience-enhancing strategies. Soils Found. 2023, 63, 101297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.L.; Uchida, T. Performance and topographic preferences of dynamic and steady models for shallow landslide prediction in a small catchment. Landslides 2022, 19, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Tang, H.; Hu, X.; Bobet, A.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, T.; Song, Y.; Ez Eldin, M.A.M. Identification of causal factors for the Majiagou landslide using modern data mining methods. Landslides 2017, 14, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, K.M.P.; Gomaa, S.M.M.H.; Zayed, T.; Alfalah, G. Rainfall-induced landslide prediction models, part ii: Deterministic physical and phenomenologically models. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, B.G.; Park, H.J.; Catani, F.; Simoni, A.; Berti, M. Landslide prediction, monitoring and early warning: A concise review of state-of-the-art. Geosci. J. 2017, 21, 1033–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segoni, S.; Piciullo, L.; Gariano, S.L. A review of the recent literature on rainfall thresholds for landslide occurrence. Landslides 2018, 15, 1483–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merghadi, A.; Yunus, A.P.; Dou, J.; Whiteley, J.; ThaiPham, B.; Bui, D.T.; Avtar, R.; Abderrahmane, B. Machine learning methods for landslide susceptibility studies: A comparative overview of algorithm performance. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 207, 103225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shano, L.; Raghuvanshi, T.K.; Meten, M. Landslide susceptibility evaluation and hazard zonation techniques–a review. Geoenviron. Disasters 2020, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, L.; Yuan, X. Machine learning algorithms and techniques for landslide susceptibility investigation: A literature review. Tumu Yu Huanjing Gongcheng Xuebao/J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2022, 44, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zheng, C. A Scientometric analysis of predicting methods for identifying the environmental risks caused by landslides. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wu, X.; Ling, S.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Peng, L.; He, Z. A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends on GIS-based landslide susceptibility from 2001 to 2020. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 86954–86993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, O. Landslide fatality occurrence: A systematic review of research published between January 2010 and March 2022. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vung, D.V.; Tran, T.V.; Ha, N.D.; Duong, N.H. Advancements, Challenges, and Future Directions in Rainfall-Induced Landslide Prediction: A Comprehensive Review. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2023, 55, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, K.M.P.; Fares, A.; Faris, N.; Zayed, T. Exploring time series models for landslide prediction: A literature review. Geoenviron. Disasters 2024, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Al-Hussein, M. Building information modelling for off-site construction: Review and future directions. Autom. Constr. 2019, 101, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuni, I.Y.; Shen, G.Q. Critical success factors for modular integrated construction projects: A review. Build. Res. Inf. 2020, 48, 763–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, E.M.; Al-Sakkaf, A.; Ebrahim, K.; Elkabalawy, M. Maintenance Budget Allocation Models of Existing Bridge Structures: Systematic Literature and Scientometric Reviews of the Last Three Decades. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, K.M.P.; Gomaa, S.M.M.H.; Zayed, T.; Alfalah, G. Recent Phenomenal and Investigational Subsurface Landslide Monitoring Techniques: A Mixed Review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlin, C. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software, London, UK, 13–14 May 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, K.; Alonso, E.; Yerro, A.; Kumar, K.; Bandara, S. Trends in large-deformation analysis of landslide mass movements with particular emphasis on the material point method. Géotechnique 2016, 66, 248–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, R.M.A.; Dehrashid, A.A.; Zhang, B.; Le, B.N.; Moayedi, H. A novel swarm intelligence: Cuckoo optimization algorithm (COA) and SailFish optimizer (SFO) in landslide susceptibility assessment. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37, 1717–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Tang, J.; Liao, R.P.; Zhang, M.F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.M.; Su, Z.Y. Application of an enhanced BP neural network model with water cycle algorithm on landslide prediction. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2021, 35, 1273–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondini, A.C.; Guzzetti, F.; Melillo, M. Deep learning forecast of rainfall-induced shallow landslides. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Feng, P.; Zuo, Q. A multi-feature fusion transfer learning method for displacement prediction of rainfall reservoir-induced landslide with step-like deformation characteristics. Eng. Geol. 2022, 297, 106494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Zayed, T. Crane operations and planning in modular integrated construction: Mixed review of literature. Autom. Constr. 2021, 122, 103466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguz, E.A.; Depina, I.; Thakur, V. Effects of soil heterogeneity on susceptibility of shallow landslides. Landslides 2022, 19, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AECOM Asia Company Limited. Detailed Study of the 29 August 2018 Landslides on the Natural Hillside Above Fan Kam Road, Pat Heung; Geotechnical Engineering Office: Hong Kong SAR, China, 2019; Volume 363, p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.; Adler, R.; Huffman, G. Evaluation of the potential of NASA multi-satellite precipitation analysis in global landslide hazard assessment. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L22402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.L.; Ng, K.Y.; Huang, Y.F.; Li, W.C. Rainfall-induced landslides in Hulu Kelang area, Malaysia. Nat. Hazards 2014, 70, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariano, S.L.; Sarkar, R.; Dikshit, A.; Dorji, K.; Brunetti, M.T.; Peruccacci, S.; Melillo, M. Automatic calculation of rainfall thresholds for landslide occurrence in Chukha Dzongkhag, Bhutan. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 4325–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; Lan, H.X.; Gao, X.; Li, L.P.; Yang, Z.H. A simplified physically based coupled rainfall threshold model for triggering landslides. Eng. Geol. 2015, 195, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Dai, Q.; Han, D.; Dai, H.; Mao, J.; Zhuo, L. Probabilistic thresholds for landslides warning by integrating soil moisture conditions with rainfall thresholds. J. Hydrol. 2019, 574, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, F.; Melillo, M.; Mondini, A.C. Landslide predictions through combined rainfall threshold models. Landslides 2024, 22, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruccacci, S.; Brunetti, M.T.; Gariano, S.L.; Melillo, M.; Rossi, M.; Guzzetti, F. Rainfall thresholds for possible landslide occurrence in Italy. Geomorphology 2017, 290, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melillo, M.; Brunetti, M.T.; Peruccacci, S.; Gariano, S.L.; Roccati, A.; Guzzetti, F. A tool for the automatic calculation of rainfall thresholds for landslide occurrence. Environ. Model. Softw. 2018, 105, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ering, P.; Babu, G.S. Characterization of critical rainfall for slopes prone to rainfall-induced landslides. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2020, 21, 06020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Kim, J.; Jeong, S. Rainfall intensity-duration thresholds for landslide prediction in South Korea by considering the effects of antecedent rainfall. Landslides 2018, 15, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwihirwe, J.; Hrachowitz, M.; Bogaard, T.A. Landslide precipitation thresholds in Rwanda. Landslides 2020, 17, 2469–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhorn, C.; Yune, C.Y.; Kim, G.; Lee, S.W. Study for assessment of rainfall duration inducing landslides. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Munic. Eng. 2016, 169, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Dai, Q.; Han, D.; Dai, H.; Mao, J.; Zhuo, L.; Rong, G. Estimation of soil moisture using modified antecedent precipitation index with application in landslide predictions. Landslides 2019, 16, 2381–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, M.T.; Peruccacci, S.; Rossi, M.; Luciani, S.; Valigi, D.; Guzzetti, F. Rainfall thresholds for the possible occurrence of landslides in Italy. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryastana, P.; Dewi, L.; Wahyuni, P.I. A study of rainfall thresholds for landslides in Badung Regency using satellite-derived rainfall grid datasets. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2024, 13, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaard, T.A.; Greco, R. Hydrological perspectives on precipitation intensity-duration thresholds for a landslide initiation: Proposing hydro-meteorological thresholds. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, D.L.; Versace, P. A comprehensive framework for empirical modeling of landslides induced by rainfall: The Generalized FLaIR Model (GFM). Landslides 2017, 14, 1009–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezak, N.; Jemec Auflič, M.; Mikoš, M. Application of hydrological modelling for temporal prediction of rainfall-induced shallow landslides. Landslides 2019, 16, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.Y.; Lee, K.T.; Chang, T.C.; Wang, Z.Y.; Liao, Y.H. Influences of spatial distribution of soil thickness on shallow landslide prediction. Eng. Geol. 2012, 124, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, Z. Identification of flysch landslide triggers using conventional and ‘nearly real-time monitoring methods–An example from the Carpathian Mountains, Poland. Eng. Geol. 2018, 244, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davar, S.; Nobahar, M.; Khan, M.S.; Amini, F. The development of PSO-ANN and BOA-ANN models for predicting matric suction in expansive clay soil. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yin, K.; Zhou, C.; Ahmed, B. Establishment of landslide groundwater level prediction model based on GA-SVM and influencing factor analysis. Sensors 2020, 20, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Tang, H. A novel decomposition-ensemble learning model based on ensemble empirical mode decomposition and recurrent neural network for landslide displacement prediction. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, C.; Zeng, Z.; Yao, W.; Tang, H. Extreme learning machine for the displacement prediction of landslide under rainfall and reservoir level. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2014, 28, 1957–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Zeng, Z.; Lian, C.; Tang, H. Training enhanced reservoir computing predictor for landslide displacement. Eng. Geol. 2015, 188, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, P.; Zheng, J. Prediction of time to slope failure based on a new model. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 5279–5291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, H.; Tannant, D.D.; Lin, C.; Xia, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. A novel model for landslide displacement prediction based on EDR selection and multi-swarm intelligence optimization algorithm. Sensors 2021, 21, 8352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Long, G.; Shao, P.; Lv, Y.; Gan, F.; Liao, J. A DES-BDNN based probabilistic forecasting approach for step-like landslide displacement. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 394, 136281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krkač, M.; Špoljarić, D.; Bernat, S.; Arbanas, S.M. Method for prediction of landslide movements based on random forests. Landslides 2017, 14, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Shi, B.; Zhang, L. Prediction of landslide sharp increase displacement by SVM with considering hysteresis of groundwater change. Eng. Geol. 2021, 280, 105876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shentu, N.; Yang, J.; Li, Q.; Qiu, G.; Wang, F. Research on the Landslide Prediction Based on the Dual Mutual-Inductance Deep Displacement 3D Measuring Sensor. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yin, K.; Alexander, D.E.; Zhou, C. Using an extreme learning machine to predict the displacement of step-like landslides in relation to controlling factors. Landslides 2016, 13, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, C.; Chen, C.P.; Zeng, Z.; Yao, W.; Tang, H. Prediction intervals for landslide displacement based on switched neural networks. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2016, 65, 1483–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Qin, Z.; Liu, F.; Liu, L. Rainfall data feature extraction and its verification in displacement prediction of Baishuihe landslide in China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2016, 75, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Yue, J.; Chen, C. Interval estimation of landslide displacement prediction based on time series decomposition and long short-term memory network. IEEE Access 2019, 8, 3187–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Dai, S.; Chen, X. Landslide prediction based on a combination intelligent method using the GM and ENN: Two cases of landslides in the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Landslides 2020, 17, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, Y. Time Series Prediction Model of Landslide Displacement Using Mean-Based Low-Rank Autoregressive Tensor Completion. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, K.; Wang, W.; Meng, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, H. Hydrodynamic landslide displacement prediction using combined extreme learning machine and random search support vector regression model. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2023, 27, 2345–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krkač, M.; Bernat Gazibara, S.; Arbanas, Ž.; Sečanj, M.; Mihalić Arbanas, S. A comparative study of random forests and multiple linear regression in the prediction of landslide velocity. Landslides 2020, 17, 2515–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasahara, K. Prediction of the shear deformation of a sandy model slope generated by rainfall based on the monitoring of the shear strain and the pore pressure in the slope. Eng. Geol. 2017, 224, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Goh, A.T.; Zhang, Y. Multivariate adaptive regression splines application for multivariate geotechnical problems with big data. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2016, 34, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, G.; Lu, S.; Wang, X. An attempt to quantify the lag time of hydrodynamic action based on the long-term monitoring of a typical landslide, Three Gorges, China. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 2018, 5958436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolmasov, B.; Milenković, S.; Marjanović, M.; Đurić, U.; Jelisavac, B. A geotechnical model of the Umka landslide with reference to landslides in weathered Neogene marls in Serbia. Landslides 2015, 12, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengtrairat, N.; Woo, W.L.; Parathai, P.; Aryupong, C.; Jitsangiam, P.; Rinchumphu, D. Automated landslide-risk prediction using web gis and machine learning models. Sensors 2021, 21, 4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, F.T.; Ebecken, N.F. A data based model to predict landslide induced by rainfall in Rio de Janeiro city. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2012, 30, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrapu, B.M.; Kukunuri, A.; Jakka, R.S. Improvement in prediction of slope stability relative importance factors using ANN. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2021, 39, 5879–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.J.; Lee, S. Shallow landslide susceptibility modeling using the data mining models artificial neural network and boosted tree. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaupane, K.M.; Achet, S.H. Use of backpropagation neural network for landslide monitoring: A case study in the higher Himalaya. Eng. Geol. 2004, 74, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jin, A.; Nie, W.; Liu, C.; Li, Y. Research on SSA-LSTM-based slope monitoring and early warning model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Liu, Y.; Xie, K.; Wen, C.; Tian, H.-L.; He, J.-B.; Zhang, W. Study on Landslide Displacement Prediction Considering Inducement under Composite Model Optimization. Electronics 2024, 13, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J.; Matsuura, K. Advantages of the mean absolute error (MAE) over the root mean square error (RMSE) in assessing average model performance. Clim. Res. 2005, 30, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistics notes: Measurement error. Br. Med. J. 1996, 313, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.R. An introduction to error analysis: The study of uncertainties in physical measurements. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1998, 9, 022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Seno, N.; Evangelista, D.; Piccolomini, E.; Berti, M. Comparative analysis of conventional and machine learning techniques for rainfall threshold evaluation under complex geological conditions. Landslides 2024, 21, 2893–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jian, W.; Nie, W. Rainstorm-induced landslides early warning system in mountainous cities based on groundwater level change fast prediction. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69, 102817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.W.W.; Usman, M.; Guo, H. Spatiotemporal pore-water pressure prediction using multi-input long short-term memory. Eng. Geol. 2023, 322, 107194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, C.; Michel, C.; Andréassian, V. Improvement of a parsimonious model for streamflow simulation. J. Hydrol. 2003, 279, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.T.; Ho, J.Y. Prediction of landslide occurrence based on slope-instability analysis and hydrological model simulation. J. Hydrol. 2009, 375, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.E. Prediction of shallow landslide by surficial stability analysis considering rainfall infiltration. Eng. Geol. 2017, 231, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.Y.; Lee, K.T. Performance evaluation of a physically based model for shallow landslide prediction. Landslides 2017, 14, 961–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkby, M.J. Hydrograph Modeling Strategies. Process Phys. Hum. Geogr. 1975, 69–90. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1573668924582225152 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Wang, S.; Zhang, K.; van Beek, L.P.; Tian, X.; Bogaard, T.A. Physically-based landslide prediction over a large region: Scaling low-resolution hydrological model results for high-resolution slope stability assessment. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 124, 104607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, R.; Meisina, C.; Montrasio, L.; Losi, G.L.; Zizioli, D. Predictive power evaluation of a physically based model for shallow landslides in the area of Oltrepò Pavese, Northern Italy. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2014, 32, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yan, E.; Wang, Y.; Huang, S.; Liu, Y. Load-Unload Response Characteristics and Prediction of Reservoir Landslides. Electron. J. Geotech. Eng. 2016, 21, 5599–5608. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues Neto, J.M.D.S.; Bhandary, N.P.; Fujita, Y. An Analytical Study on Soil Water Index (SWI), Landslide Prediction and Other Related Factors Using XRAIN Data during the July 2018 Heavy Rain Disasters in Hiroshima, Japan. Geotechnics 2023, 3, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Dai, Q.; Han, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhuo, L.; Berti, M. Application of hydrological model simulations in landslide predictions. Landslides 2020, 17, 877–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, S.J.; Ewen, J. Nitrogen transformation component for SHETRAN catchment nitrate transport modelling. J. Hydrol. 2000, 230, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, L.; Picarelli, L.; Rianna, G.; Urciuoli, G. A simple numerical procedure for timely prediction of precipitation-induced landslides in unsaturated pyroclastic soils. Landslides 2010, 7, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, K.; Taiwo, R.; Zayed, T. OWHK: Operational volumetric water content forecasting model for shallow rainfall-induced landslides in Hong Kong. Eng. Geol. 2025, 355, 108228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, K.; Abdelkader, E.M.; Zayed, T.; Meguid, M.A. A deep learning-based model for endorsing predictive accuracies of landslide prediction: Insights into soil moisture dynamics. Geoenviron. Disasters 2025, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Source | Documents (No.) | Citations (No.) | Total Strength Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Landslides | 32 | 4195 | 1190 |

| 2 | Engineering Geology | 19 | 1414 | 733 |

| 3 | Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment | 11 | 317 | 625 |

| 4 | Applied Sciences (Switzerland) | 11 | 178 | 354 |

| 5 | Géotechnique | 8 | 6117 | 142 |

| 6 | Geotechnical and Geological engineering | 7 | 173 | 330 |

| 7 | Sustainability (Switzerland) | 7 | 76 | 253 |

| 8 | Journal of Hydrology | 6 | 1456 | 396 |

| 9 | Geoenvironmental disaster | 5 | 404 | 405 |

| 10 | stochastic environmental research and risk assessment | 5 | 290 | 172 |

| Country | Documents | Citations | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 77 | 3896 | 7348 |

| Italy | 30 | 5007 | 5622 |

| United States | 26 | 5146 | 2963 |

| United Kingdom | 20 | 6299 | 2623 |

| Japan | 11 | 2351 | 2098 |

| Gap | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| High false-positive rates in I-D thresholds due to two primary oversights: (1) the influence of infiltration capacity and subsurface hydrology, and (2) the role of slope-specific properties (e.g., geometry, geotechnical parameters). | 1. Conduct field experiments to quantitatively establish the relationship between rainfall, evaporation, infiltration, and surface runoff. 2. Perform sensitivity analyses to identify the dominant physical parameters, enabling the development of refined I-D thresholds that retain simplicity while improving accuracy. |

| Over-reliance on surface displacement data in physically based models, which fails to capture sudden failure mechanisms driven by subsurface processes (e.g., deep-seated displacement, tilting, suction stress, groundwater fluctuations). | Develop and deploy comprehensive subsurface monitoring systems to create high-resolution datasets. These datasets should be used to train hybrid AI models capable of predicting complex, nonlinear landslide mechanisms and precursor signals of sudden failure [113,114]. |

| Inadequate consideration of practical field constraints, including data loss from sensor failure in harsh environments and limitations imposed by telecommunication data rates. | Implement robust data validation and gap-filling techniques. Furthermore, conduct sensitivity analysis to optimize the trade-off between data transmission rates, model complexity, and prediction reliability under realistic operational constraints. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ebrahim, K.; Gomaa, S.M.M.H.; Zayed, T.; Alfalah, G. Rainfall-Induced Landslide Prediction Models, Part I: Empirical–Statistical and Physically Based Causative Thresholds. Water 2025, 17, 3273. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223273

Ebrahim K, Gomaa SMMH, Zayed T, Alfalah G. Rainfall-Induced Landslide Prediction Models, Part I: Empirical–Statistical and Physically Based Causative Thresholds. Water. 2025; 17(22):3273. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223273

Chicago/Turabian StyleEbrahim, Kyrillos, Sherif M. M. H. Gomaa, Tarek Zayed, and Ghasan Alfalah. 2025. "Rainfall-Induced Landslide Prediction Models, Part I: Empirical–Statistical and Physically Based Causative Thresholds" Water 17, no. 22: 3273. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223273

APA StyleEbrahim, K., Gomaa, S. M. M. H., Zayed, T., & Alfalah, G. (2025). Rainfall-Induced Landslide Prediction Models, Part I: Empirical–Statistical and Physically Based Causative Thresholds. Water, 17(22), 3273. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223273