Plant-Derived miRNAs as Potential Cross-Kingdom Cancer Regulators

Abstract

1. Introduction

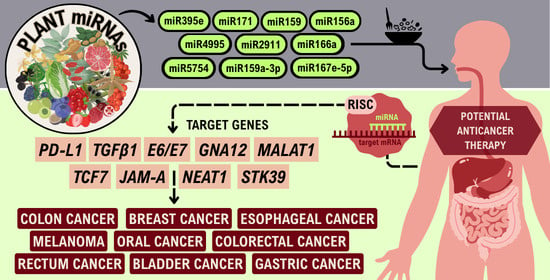

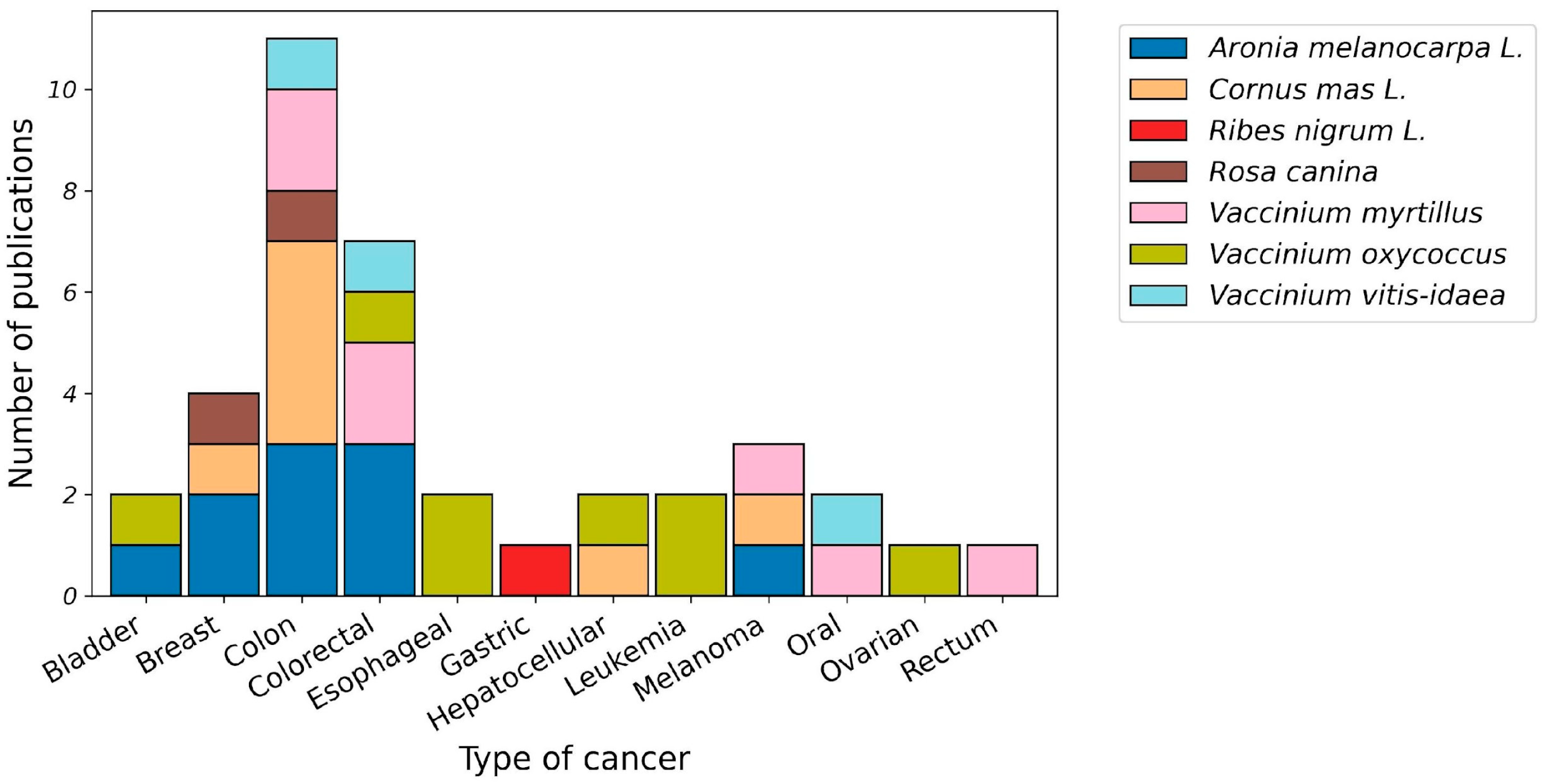

2. Plant-Derived miRNAs and Cancer

3. Future Perspectives

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shenouda, S.K.; Alahari, S.K. MicroRNA Function in Cancer: Oncogene or a Tumor Suppressor? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009, 28, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Croce, C.M. The Role of MicroRNAs in Human Cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2016, 1, 15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasculli, E.; Gadaleta, R.M.; Arconzo, M.; Cariello, M.; Moschetta, A. The Role of Exogenous microRNAs on Human Health: The Plant–Human Trans-Kingdom Hypothesis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Li, R.; Cao, C.; Shi, L.; Wu, W.; He, K. A Timely Review of Cross-Kingdom Regulation of Plant-Derived MicroRNAs. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 613197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.J.; Li, Y.Y.; Xiang, Z.H.; Deng, J.; Li, W.; Lin, Q.L.; Fang, Y.; Liu, F.; Bai, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Emerging Evidence on the Effects of Plant-Derived microRNAs in Colorectal Cancer: A Review. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Rosenberg, I.; Uauy, R. History of Modern Nutrition Science-Implications for Current Research, Dietary Guidelines, and Food Policy. BMJ 2018, 361, k2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Pagliai, G.; Angelino, D.; Rosi, A.; Dall’Asta, M.; Bresciani, L.; Ferraris, C.; Guglielmetti, M.; Godos, J.; Del Bo’, C.; et al. Effects of Popular Diets on Anthropometric and Cardiometabolic Parameters: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 815–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.B.; Rizvi, S.I. Plant Polyphenols as Dietary Antioxidants in Human Health and Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2009, 2, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Wazed, M.A.; Asha, S.; Amin, M.R.; Shimul, I.M. Dietary Phytochemicals in Health and Disease: Mechanisms, Clinical Evidence, and Applications—A Comprehensive Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N.; Zidane, L. Plant-Derived Natural Products: A Source for Drug Discovery and Development. Drugs Drug Candidates 2024, 3, 184–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letchuman, S.; Madhuranga, H.D.T.; Madhurangi, B.L.N.K.; Premarathna, A.D.; Saravanan, M. Alkaloids Unveiled: A Comprehensive Analysis of Novel Therapeutic Properties, Mechanisms, and Plant-Based Innovations. Intell. Pharm. 2025, 3, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsena, Y.P.; Phosanam, A.; Stockmann, R. Perspectives on Saponins: Food Functionality and Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.-L.; Gong, X.; Ji, M.-Y.; Wang, C.-C.; Wang, J.-H.; Li, M.-H. Bioactive Compounds from Plant-Based Functional Foods: A Promising Choice for the Prevention and Management of Hyperuricemia. Foods 2020, 9, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, E.M.; Hirschi, K.D. Roles of Regulatory RNAs in Nutritional Control. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2020, 40, 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo-Acebo, L.; López de Las Hazas, M.C.; Margollés, A.; Dávalos, A.; García-Ruiz, A. Eating microRNAs: Pharmacological Opportunities for Cross-Kingdom Regulation and Implications in Host Gene and Gut Microbiota Modulation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 2218–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchita; Trivedi, R.; Asif, M.H.; Trivedi, P.K. Dietary Plant miRNAs as an Augmented Therapy: Cross-Kingdom Gene Regulation. RNA Biol. 2018, 15, 1433–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.F.A.; Kamaroddin, M.F.; Sajad, M. Cross-Kingdom Regulation by Plant microRNAs Provides Novel Insight into Gene Regulation. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajczyk, M.; Jarmolowski, A.; Jozwiak, M.; Pacak, A.; Pietrykowska, H.; Sierocka, I.; Swida-Barteczka, A.; Szewc, L.; Szweykowska-Kulinska, Z. Recent Insights into Plant miRNA Biogenesis: Multiple Layers of miRNA Level Regulation. Plants 2023, 12, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, P.Y.; Shabir, P.A.; Hakeem, K.R. miRNAomics and Stress Management in Plants, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-003-24845-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, L. MicroRNAs in Plants Development and Stress Resistance. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 5909–5929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samynathan, R.; Venkidasamy, B.; Shanmugam, A.; Ramalingam, S.; Thiruvengadam, M. Functional Role of microRNA in the Regulation of Biotic and Abiotic Stress in Agronomic Plants. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Li, W.; Li, F.; Ren, M.; Wang, W. microRNAs: Key Regulators in Plant Responses to Abiotic and Biotic Stresses via Endogenous and Cross-Kingdom Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, L.L.; Zhang, L.L.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J. Role of microRNA miR171 in Plant Development. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Hu, B.; Zhang, C. microRNAs and Their Roles in Plant Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 824240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, A.A.; Waterhouse, P.M. Plant and Animal microRNAs: Similarities and Differences. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2005, 5, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, K.; Chen, X. Biogenesis, Turnover, and Mode of Action of Plant microRNAs. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 2383–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axtell, M.J.; Westholm, J.O.; Lai, E.C. Vive la différence: Biogenesis and Evolution of microRNAs in Plants and Animals. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Chen, X.; Yu, B. Small RNAs Meet Their Targets: When Methylation Defends miRNAs from Uridylation. RNA Biol. 2014, 11, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Chekanova, J.A. Small RNAs: Essential Regulators of Gene Expression and Defenses against Environmental Stresses in Plants. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2016, 7, 356–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; He, J.; Bai, W.; Lin, Q.; Deng, J.; Li, W.; Bai, J.; Fu, D.; Ma, Y.; Ren, J.; et al. Cross-Kingdom Regulation by Dietary Plant miRNAs: An Evidence-Based Review with Recent Updates. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 9549–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Ren, C.Q.; Cao, Y.N.; Ren, Y.; Zou, L.; Zhou, C.; Peng, L.X. Role of MicroRNAs in Dietary Interventions for Obesity and Obesity-Related Diseases. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 14396–14412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar-Aguilar, F.; Arreola-Triana, A.; Mata-Cardona, D.; Gonzalez-Villasana, V.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C.; Reséndez-Pérez, D. Evidence of Transfer of miRNAs from the Diet to the Blood Still Inconclusive. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, M.A.; Bueso-Ramos, C.; Ferdin, J.; Lopez-Berestein, G.; Sood, A.K.; Calin, G.A. MicroRNAs in Body Fluids--the Mix of Hormones and Biomarkers. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 8, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasik, A.; Brzozowska, I.; Zielenkiewicz, U.; Zielenkiewicz, P. Detection of Plant miRNAs Abundance in Human Breast Milk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasik, A.; Zielenkiewicz, P. In Silico Identification of Plant miRNAs in Mammalian Breast Milk Exosomes—A Small Step Forward? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroux, C.; Chervet, M.L.; German, J.B. Perspective: Milk microRNAs as Important Players in Infant Physiology and Development. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1625–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaweed, M.; Hartmann, P.E.; Geddes, D.T.; Kakulas, F. MicroRNAs in Breastmilk and the Lactating Breast: Potential Immunoprotectors and Developmental Regulators for the Infant and the Mother. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 13981–14020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembo, K.M.; Wang, X.; Bolideei, M.; Liu, Q.; Baboni, F.; Mehran, M.J.; Sun, F.; Wang, C.-Y. Exploring the Bioactivity of MicroRNAs Originated from Plant-Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticles (PELNs): Current Perspectives. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hou, D.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Bian, Z.; Liang, X.; Cai, X.; et al. Exogenous Plant MIR168a Specifically Targets Mammalian LDLRAP1: Evidence of Cross-Kingdom Regulation by microRNA. Cell Res. 2012, 22, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, B. Plant-Derived XenomiRs and Cancer: Cross-Kingdom Gene Regulation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 2408–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Karunairetnam, S.; Lo, K.R.; Kralicek, A.V.; Crowhurst, R.N.; Gleave, A.P.; MacDiarmid, R.M.; Ingram, J.R. Common Variants of the Plant microRNA-168a Exhibit Differing Silencing Efficacy for Human Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor Adaptor Protein 1 (LDLRAP1). MicroRNA 2019, 8, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, B.; Shao, Y.; Jing, A.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Z. Assessing the Survival of Exogenous Plant microRNA in Mice. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 2, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Wang, C.; Li, F.; Peng, Y.; Sima, J.; Li, Y.; Deng, L.; Wu, K.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Z. Cross-Kingdom Regulation of Gene Expression in Giant Pandas via Plant-Derived miRNA. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1509698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, M.T.D.; Tagliaferri, P.; Tassone, P. MicroRNA in Cancer Therapy: Breakthroughs and Challenges in Early Clinical Applications. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávalos, A.; Pinilla, L.; López de Las Hazas, M.C.; Pinto-Hernández, P.; Barbé, F.; Iglesias-Gutiérrez, E.; de Gonzalo-Calvo, D. Dietary microRNAs and Cancer: A New Therapeutic Approach? Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 73, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Guo, C.; Fang, M.; Yang, Y.; Yin, F.; Shen, Y. Cross-Kingdom Regulation of Plant microRNAs: Potential Application in Crop Improvement and Human Disease Therapeutics. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1512047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Xu, B. Cross-Kingdom Regulation of Plant-Derived miRNAs in Modulating Insect Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, X.; Qi, B.; Liang, Q.; Yang, X.; Li, L.; Li, S. Digestion of Plant Dietary miRNAs Starts in the Mouth under the Protection of Coingested Food Components and Plant-Derived Exosome-Like Nanoparticles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 4316–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślik, M.; Bryniarski, K.; Nazimek, K. Dietary and Orally-Delivered miRNAs: Are They Functional and Ready to Modulate Immunity? AIMS Allergy Immunol. 2023, 7, 104–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, T.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-L. Dietary microRNA—A Novel Functional Component of Food. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Sainz, E.; Milagro, F.I.; Aranaz, P.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Lorente-Cebrián, S. MicroRNAs from Edible Plants Reach the Human Gastrointestinal Tract and May Act as Potential Regulators of Gene Expression. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 80, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Xu, F.; Zhang, X.; Mu, J.; Sayed, M.; Hu, X.; Lei, C.; Sriwastva, M.; Kumar, A.; Sundaram, K.; et al. Plant-Derived Exosomal microRNAs Inhibit Lung Inflammation Induced by Exosomes SARS-CoV-2 Nsp12. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 2424–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ren, X.; Ning, L.; Wang, P.; Xu, K. Stability and Absorption Mechanism of Typical Plant miRNAs in an In Vitro Gastrointestinal Environment: Basis for Their Cross-Kingdom Nutritional Effects. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 81, 108376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Lin, H.; Jiang, X.; Li, W.; Gao, Y.; Li, M.; Yu, Y.; Chen, N.; Gao, J. Exosome-Like Nanoparticles Derived from Fruits, Vegetables, and Herbs: Innovative Strategies of Therapeutic and Drug Delivery. Theranostics 2024, 14, 4598–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Gao, B.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Pei, X.; Yue, B.; Zhen, X.; Zhang, M. Leveraging Plant-Derived Nanovesicles for Advanced Nucleic Acid-Based Gene Therapy. Theranostics 2025, 15, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.; Guo, H. A Decade Later: Future Perspectives on Dietary microRNAs. ExRNA 2024, 1, 0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Chu, Q.; Sun, S.; Wu, Y.; Tong, Z.; Fang, W.; Timko, M.P.; Fan, L. Large-Scale Identification of Extracellular Plant miRNAs in Mammals Implicates Their Dietary Intake. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Chen, W.L.; Kung, W.-H.; Huang, H.D. Plant miRNAs Found in Human Circulating System Provide Evidences of Cross-Kingdom RNAi. BMC Genom. 2017, 18 (Suppl. 2), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Feng, H. Cross-Kingdom Regulation by Plant-Derived miRNAs in Mammalian Systems. Anim. Models Exp. Med. 2023, 6, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potestà, M.; Roglia, V.; Fanelli, M.; Pietrobono, E.; Gismondi, A.; Vumbaca, S.; Nguedia Tsangueu, R.G.; Canini, A.; Colizzi, V.; Grelli, S.; et al. Effect of Microvesicles from Moringa Oleifera Containing miRNA on Proliferation and Apoptosis in Tumor Cell Lines. Cell Death Discov. 2020, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, A.R.; Fong, M.Y.; Somlo, G.; Wu, J.; Swiderski, P.; Wu, X.; Wang, S.E. Cross-Kingdom Inhibition of Breast Cancer Growth by Plant miR159. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Cai, L.; Tian, Y.; Tu, Y.; Qiu, H.; Xie, G.; Huang, D.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, W. miR156a Mimic Represses the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of Human Nasopharyngeal Cancer Cells by Targeting Junctional Adhesion Molecule A. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, B.; Sun, G.; He, W.; Gao, J.; Huang, T.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Q.; He, X.; Zhang, S.; et al. Selenium Biofortification Enhanced miR167a Expression in Broccoli Extracellular Vesicles Inducing Apoptosis in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells by Targeting IRS1. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 2431–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, T.; He, J.-J.; Wu, J.-H.; Luo, J.-Y.; Ye, R.-S.; Xie, M.-Y.; Zhang, H.-J.; Zeng, B.; Liu, J.; et al. Plant MIR167e-5p Inhibits Enterocyte Proliferation by Targeting β-Catenin. Cells 2019, 8, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Weng, Z.; Sui, X.; Fang, Y.; Tang, X.; Shen, X. Soybean-Derived miRNAs Specifically Inhibit Proliferation and Stimulate Apoptosis of Human Colonic Caco-2 Cancer Cells but Not Normal Mucosal Cells in Culture. Genomics 2020, 112, 2949–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, F.; Caratozzolo, M.F.; Consiglio, A.; Licciulli, F.; Liuni, S.; Sbisà, E.; D’Elia, D.; Tullo, A.; Catalano, D. Plant miRNAs Reduce Cancer Cell Proliferation by Targeting MALAT1 and NEAT1: A Beneficial Cross-Kingdom Interaction. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 552490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismondi, A.; Nanni, V.; Monteleone, V.; Colao, C.; Di Marco, G.; Canini, A. Plant miR171 Modulates mTOR Pathway in HEK293 Cells by Targeting GNA12. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Xu, M.; Yan, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Dong, L. Honeysuckle-Derived microRNA2911 Inhibits Tumor Growth by Targeting TGF-Β1. Chin. Med. 2021, 16, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xie, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Shi, H.; Zhao, R.; Yang, X.; Tian, J.; Ma, L. The Potential of Lycium Barbarum miR166a in Kidney Cancer Treatment. Exp. Cell Res. 2023, 423, 113455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Lv, Y.; Yuan, C.; Tian, J.; Liu, X. Cross-Border Regulation of the STK39/MAPK14 Pathway by Lycium Barbarum miR166a to Inhibit Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2024, 16, 2683–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, Y.; Shi, L.; Lu, S.; Cui, H.; Zha, W.; Shan, L.; Shen, Y. Inhibitory Effect of Lonicera Japonica-Derived Exosomal miR2911 on Human Papilloma Virus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 318, 116969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusławska, J.; Rakhmetullina, A.; Grzanka, M.; Białas, A.; Rybicka, B.; Życka-Krzesińska, J.; Molcan, T.; Zielenkiewicz, P.; Pączek, L.; Piekiełko-Witkowska, A. miR395e from Manihot Esculenta Decreases Expression of PD-L1 in Renal Cancer: A Preliminary Study. Genes 2025, 16, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, F.; Dong, L.; Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. SIDT1-Dependent Absorption in the Stomach Mediates Host Uptake of Dietary and Orally Administered microRNAs. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, M.; Xie, M.; He, L.; Wang, Y.; Shi, S.; Tang, T. Expression Variations of miRNAs and mRNAs in Rice (Oryza Sativa). Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 3529–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, S.; Kumar, A.; Sarkar Das, S.; Yadav, S.; Gautam, V.; Singh, A.; Singh, S.; Sarkar, A.K. Coevolution Pattern and Functional Conservation or Divergence of miR167s and Their Targets across Diverse Plant Species. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Yang, X.; Gao, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Li, L. Identification and Characterization of a Subset of microRNAs in Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). Genomics 2014, 103, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mica, E.; Gianfranceschi, L.; Pè, M.E. Characterization of Five microRNA Families in Maize. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 2601–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.H. Therapeutic Potential of Phenolic Compounds in Medicinal Plants-Natural Health Products for Human Health. Molecules 2023, 28, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; P, N.; Kumar, M.; Jose, A.; Tomer, V.; Oz, E.; Proestos, C.; Zeng, M.; Elobeid, T.; K, S.; et al. Major Phytochemicals: Recent Advances in Health Benefits and Extraction Method. Molecules 2023, 28, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidinejad, A. Bioactive Compounds from New Zealand’s Native Edible Plants: Their Role in Future Functional Foods. Future Postharvest Food 2024, 1, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Khalid, R.; Afzal, M.; Anjum, F.; Fatima, H.; Zia, S.; Rasool, G.; Egbuna, C.; Mtewa, A.G.; Uche, C.Z.; et al. Phytobioactive Compounds as Therapeutic Agents for Human Diseases: A Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 2500–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga-Corral, M.; Otero, P.; Cassani, L.; Echave, J.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Carpena, M.; Chamorro, F.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Traditional Applications of Tannin Rich Extracts Supported by Scientific Data: Chemical Composition, Bioavailability and Bioaccessibility. Foods 2021, 10, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzi, A. Tannins Medical / Pharmacological and Related Applications: A Critical Review. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2021, 22, 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.V.; Edirisinghe, I.; Burton-Freeman, B.M. Berries: Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Humans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3886–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishayee, A.; Mbimba, T.; Thoppil, R.J.; Háznagy-Radnai, E.; Sipos, P.; Darvesh, A.S.; Folkesson, H.G.; Hohmann, J. Anthocyanin-Rich Black Currant (Ribes nigrum L.) Extract Affords Chemoprevention against Diethylnitrosamine-Induced Hepatocellular Carcinogenesis in Rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorska, D.; Mazurakova, A.; Lackova, L.; Sebova, D.; Kajo, K.; Samec, M.; Brany, D.; Svajdlenka, E.; Treml, J.; Mersakova, S.; et al. Aronia Melanocarpa L. Fruit Peels Show Anti-Cancer Effects in Preclinical Models of Breast Carcinoma: The Perspectives in the Chemoprevention and Therapy Modulation. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1463656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, B.; Yaman, M.; Sanci, T.Ö.; Güngörmüş, M.; Köprü, Ç.Z.; Güneş, F.E. Acetone Extracts of Berberis Vulgaris and Cornus Mas L. Induce Apoptosis in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 53, 1476–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, K.; Demir, S.; Turan, I.; Mentese, A.; Orem, A.; Sonmez, M.; Aliyazicioglu, Y. Rosa Canina Extract Has Antiproliferative and Proapoptotic Effects on Human Lung and Prostate Cancer Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2020, 72, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H.; Yang, J.; Li, W.; Luo, X.; Xu, Y.; Sun, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Hou, L.; Tan, G.; et al. Solanum Nigrum Linn.: Advances in Anti-Cancer Activity and Mechanism in Digestive System Tumors. Med. Oncol. 2023, 40, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onali, T.; Kivimäki, A.; Mauramo, M.; Salo, T.; Korpela, R. Anticancer Effects of Lingonberry and Bilberry on Digestive Tract Cancers. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.; MacKinnon, S.L.; Craft, C.C.; Matchett, M.D.; Hurta, R.A.R.; Neto, C.C. Ursolic Acid and Its Esters: Occurrence in Cranberries and Other Vaccinium Fruit and Effects on Matrix Metalloproteinase Activity in DU145 Prostate Tumor Cells. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goo, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, I.-S.; Jeong, C. Extracellular Vesicles in Therapeutics: A Comprehensive Review on Applications, Challenges, and Clinical Progress. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheideler, M.; Vidakovic, I.; Prassl, R. Lipid Nanocarriers for microRNA Delivery. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2020, 226, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Li, X.; Tian, Y.; Su, M.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Cui, Y.; Bian, S. Identification and Characterization of microRNAs and Their Targets from Expression Sequence Tags of Ribes Nigrum. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2016, 96, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

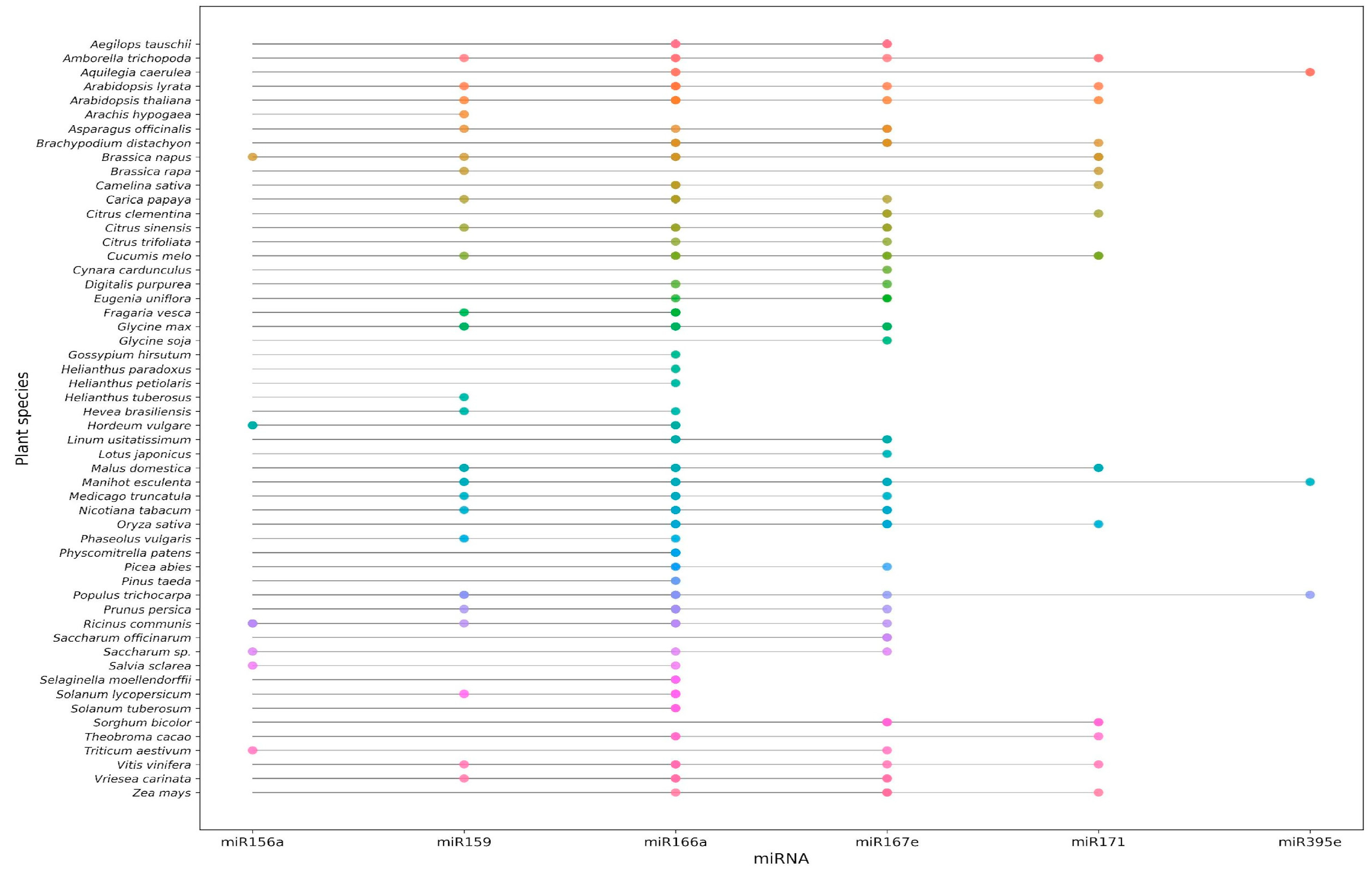

| No. | miRNA | Plant | Target | In Vitro/ In Vivo | Cell Line/Animal Model | Type of Cancer | Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | miR-159 | A.thaliana | TCF7 | in vitro/in vivo | MDA-MB-231 MCF-10A/NSG mice | breast | 2016 | [61] |

| 2 | miR-156a | B.oleracea | JAMA | in vitro | CNE2, HONE1, C666-1 | nasopharyngeal | 2016 | [62] |

| 3 | miR-167a | B.oleracea | IRS1 | in vitro | PANC-1, HEK293T | pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 2023 | [63] |

| 4 | miR-167e-5p | 33 plants * | β-catenin | in vitro | IPEC-J2, Caco-2 | colorectal | 2019 | [64] |

| 5 | miR-159a-3p | Glycine Max | TCF7 | in vitro | NCM460, Caco-2 | colon | 2020 | [65] |

| 6 | miR-5754 | Medicago truncatula | MALAT1 | in vitro | LAN-1, T98G, HepG2, HCT116 | colon | 2020 | [66] |

| 7 | miR-4995 | Glycine Max | NEAT1 | in vitro | LAN-1, T98G, HepG2, HCT116 | colon | 2020 | [66] |

| 8 | miR-171 | 15 plants ** | GNA12 | in vitro | HEK293 | oral, breast, prostate adenocarcinoma | 2021 | [67] |

| 9 | miR-2911 | Lonicera japonica | TGFβ1 | in vitro/in vivo | CT26/C57Bl/6, BALB/c mice | colon | 2021 | [68] |

| 10 | miR-166a | Lycium barbarum | CCNA2, CCND1, CCNE2, CCNB1, CDC20 | in vitro/in vivo | Caki-1, ACHN/nude mice | kidney | 2023 | [69] |

| 11 | miR-166a | Lycium barbarum | STK39 | in vivo/in vitro | MB-231/nude mice | triple-negative breast cancer | 2024 | [70] |

| 12 | miR-2911 | Lonicera japonica | E6/E7 | in vitro | HEK293T, CaSki, SiHa, HeLa | cervical | 2024 | [71] |

| 13 | miR-395e | Manihot esculenta | PD-L1 | in vitro | RCC 786-O, Caki-1, KIJ265T | renal | 2025 | [72] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rakhmetullina, A.; Lubas, Z.; Zielenkiewicz, P. Plant-Derived miRNAs as Potential Cross-Kingdom Cancer Regulators. Genes 2025, 16, 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121441

Rakhmetullina A, Lubas Z, Zielenkiewicz P. Plant-Derived miRNAs as Potential Cross-Kingdom Cancer Regulators. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121441

Chicago/Turabian StyleRakhmetullina, Aizhan, Zuzanna Lubas, and Piotr Zielenkiewicz. 2025. "Plant-Derived miRNAs as Potential Cross-Kingdom Cancer Regulators" Genes 16, no. 12: 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121441

APA StyleRakhmetullina, A., Lubas, Z., & Zielenkiewicz, P. (2025). Plant-Derived miRNAs as Potential Cross-Kingdom Cancer Regulators. Genes, 16(12), 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121441