Genetic, Clinical and Neuroradiological Spectrum of MED-Related Disorders: An Updated Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Rationale, Scope, and Structural Roadmap

3. Composition and Structure of MED Complex

4. MED1 (MIM *604311) [7]

5. MED8 (MIM *607956) [12]

6. MED11 (MIM *612383) [18]

7. MED12 (MIM *300188) [21]

8. MED12L (MIM *611318) [37]

9. MED13 (MIM *603808) [39]

10. MED13L (MIM *608771) [46]

11. MED14 (MIM *300182) [55]

12. MED16 (MIM *604062) [57]

13. MED17 (MIM *603810) [59]

14. MED20 (MIM *612915) [67]

15. MED23 (MIM *605042) [70]

16. MED25 (MIM *610197) [74]

17. MED27 (MIM *605044) [86]

18. CDK8 (MIM *603184) [90]

19. CDK19 (MIM *614720) [94]

20. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic Hormone |

| ADHD | Attention-deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorders |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| BVSYS | Basel-Vanaigate-Smirin-Yosef Syndrome |

| CARS | Childhood Autism Rating Scale |

| CC | Corpus Callosum |

| CMT | Charcot-Marie-Tooth |

| COFS | Cerebro-oculo-facio-skeletal Syndrome |

| DEE87 | Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathy 87 |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| ER | Estrogen Receptor |

| ID | Intellectual Disability |

| KS | Kabuki Syndrome |

| LS | Lujan Syndrome |

| MAE | Myoclonic–Atonic Epilepsy |

| MED | Mediator Complex |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MRS | Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy |

| NSID | Nonspecific Intellectual Disability |

| PRS | Pierre Robin Syndrome |

| WES | Whole Exome Sequencing |

| WSG | Whole-genome Sequencing |

| XLOS | X-linked Ohdo Syndrome |

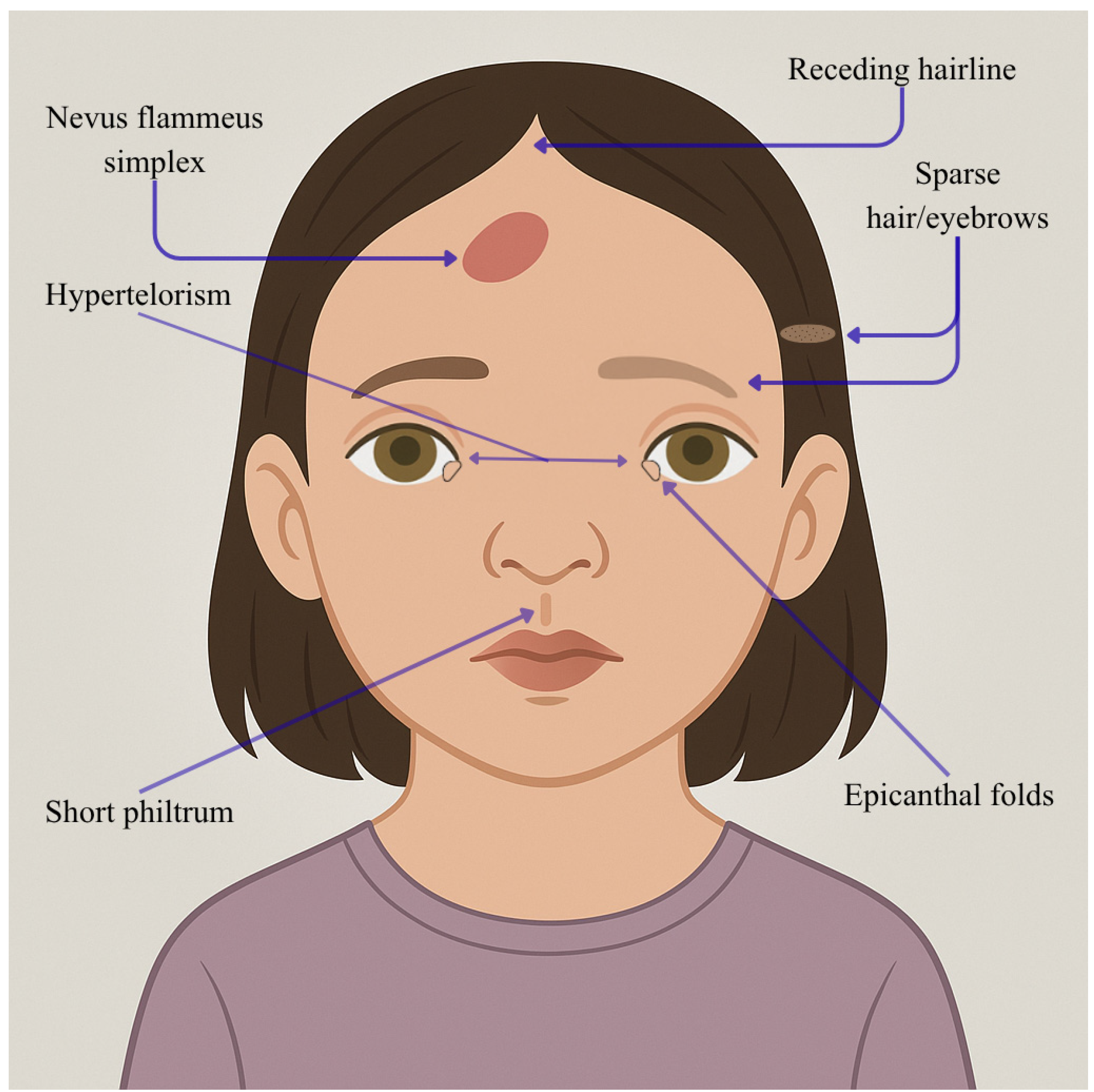

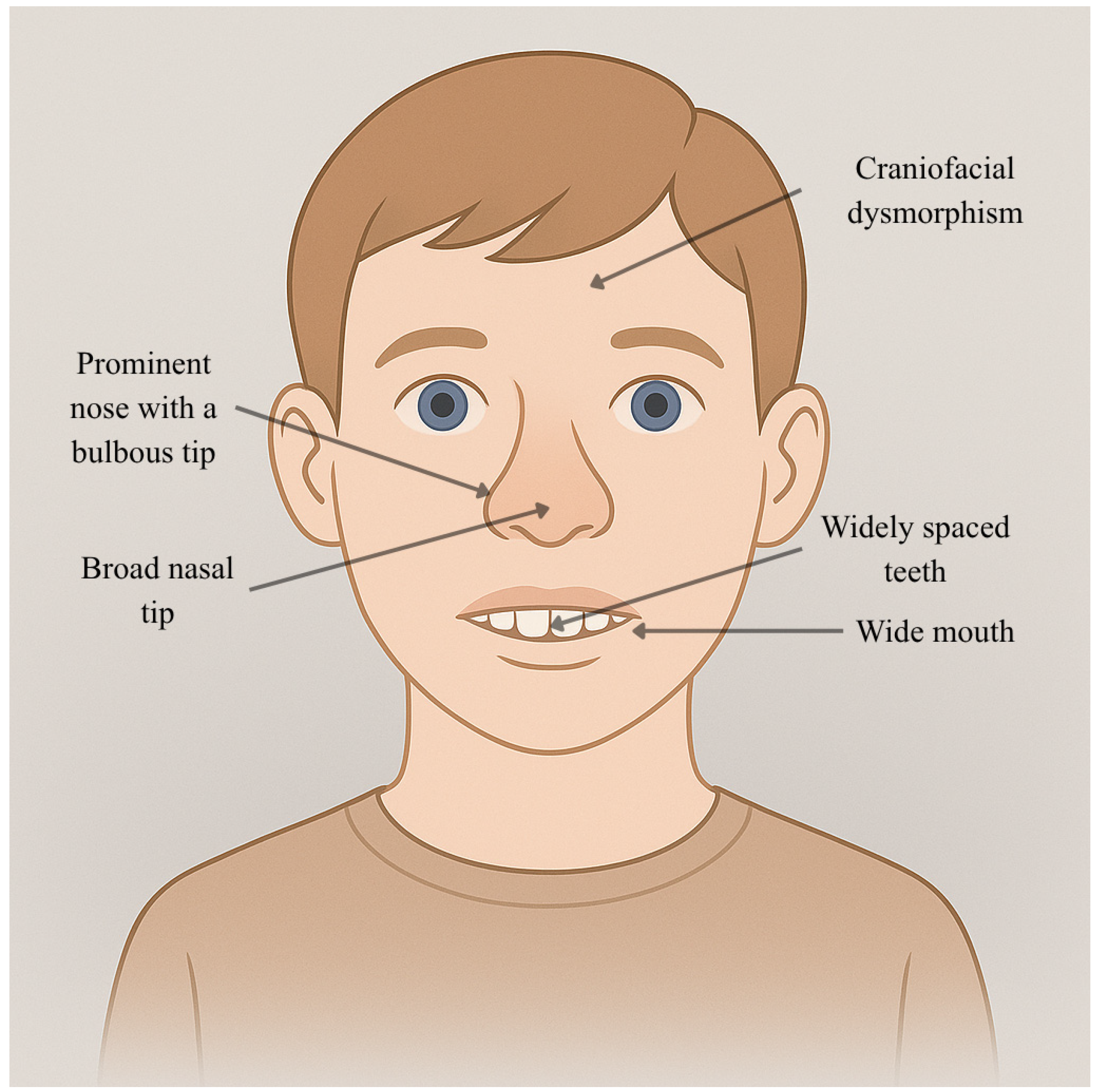

Appendix A. AI-Generated Illustrations Based on Structured Clinical Descriptions

References

- Schiano, C.; Luongo, L.; Maione, S.; Napoli, C. Mediator complex in neurological disease. Life Sci. 2023, 329, 121986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.L.; Tomomori-Sato, C.; Sato, S.; Conaway, R.C.; Conaway, J.W.; Asturias, F.J. Subunit architecture and functional modular rearrangements of the transcriptional mediator complex. Cell 2014, 157, 1430–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdella, R.; Talyzina, A.; Chen, S.; Inouye, C.J.; Tjian, R.; He, Y. Structure of the human Mediator-bound transcription preinitiation complex. Science 2021, 372, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khattabi, L.; Zhao, H.; Kalchschmidt, J.; Young, N.; Jung, S.; Van Blerkom, P.; Kieffer-Kwon, P.; Kieffer-Kwon, K.R.; Park, S.; Wang, X.; et al. A Pliable Mediator Acts as a Functional Rather than an Architectural Bridge between Promoters and Enhancers. Cell 2019, 178, 1145–1158.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutourina, J. Transcription regulation by the Mediator complex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, W.F.; Nayak, S.; Iwasa, J.; Taatjes, D.J. The Mediator complex as a master regulator of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 732–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 1; MED1; MIM Number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/604311 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Belorusova, A.Y.; Bourguet, M.; Hessmann, S.; Chalhoub, S.; Kieffer, B.; Cianférani, S.; Rochel, N. Molecular determinants of MED1 interaction with the DNA bound VDR-RXR heterodimer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 11199–11213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infantino, R.; Schiano, C.; Luongo, L.; Paino, S.; Mansueto, G.; Boccella, S.; Guida, F.; Ricciardi, F.; Iannotta, M.; Belardo, C.; et al. MED1/BDNF/TrkB pathway is involved in thalamic hemorrhage-induced pain and depression by regulating microglia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2022, 164, 105611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, M.; Zhang, X. Estrogen receptor coactivator Mediator Subunit 1 (MED1) as a tissue-specific therapeutic target in breast cancer. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2019, 20, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Krutchinsky, A.; Fukuda, A.; Chen, W.; Yamamura, S.; Chait, B.T.; Roeder, R.G. MED1/TRAP220 exists predominantly in a TRAP/Mediator subpopulation enriched in RNA polymerase II and is required for ER-mediated transcription. Mol. Cell 2005, 19, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 8; MED8; MIM Number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/607956 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Conaway, R.C.; Conaway, J.W. Origins and Activity of the Mediator Complex. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011, 22, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). SEIZURE THRESHOLD 2 HOMOLOG.; SZT2; MIM Number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/615463 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Pizzino, A.; Whitehead, M.; Sabet Rasekh, P.; Murphy, J.; Helman, G.; Bloom, M.; Evans, S.H.; Murnick, J.G.; Conry, J.; Taft, R.J.; et al. Mutations in SZT2 result in early-onset epileptic encephalopathy and leukoencephalopathy. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2018, 176, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankel, W.N.; Yang, Y.; Mahaffey, C.L.; Beyer, B.J.; O’Brien, T.P. Szt2, a novel gene for seizure threshold in mice. Genes. Brain Behav. 2009, 8, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Zhong, X.; Li, T. Novel SZT2 mutations in three patients with developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2019, 7, e926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 11; MED11; MIM Number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/612383 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Schiano, C.; Napoli, C. Mediator complex: Update of key insights into transcriptional regulation of ancestral framework and its role in cardiovascular diseases. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calì, E.; Lin, S.J.; Rocca, C.; Sahin, Y.; Al Shamsi, A.; El Chehadeh, S.; Chaabouni, M.; Mankad, K.; Galanaki, E.; Efthymiou, S.; et al. A homozygous MED11 C-terminal variant causes a lethal neurodegenerative disease. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 2194–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 12; MED12; MIM number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/300188 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Knuesel, M.T.; Meyer, K.D.; Bernecky, C.; Taatjes, D.J. The human CDK8 subcomplex is a molecular switch that controls Mediator coactivator function. Genes. Dev. 2009, 23, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, J.E. Drosophila homologues of the transcriptional coactivation complex subunits TRAP240 and TRAP230 are required for identical processes in eye-antennal disc development. Development 2001, 128, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Rhee, M.S. Synergistic bactericidal action of phytic acid and sodium chloride against Escherichia coli O157: H7 cells protected by a biofilm. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 227, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.K.; Haldin, C.E.; Lawson, N.D.; Weinstein, B.M.; Dawid, I.B.; Hukriede, N.A. The zebrafish kohtalo/trap230 gene is required for the development of the brain, neural crest, and pronephric kidney. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18473–18478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polla, D.L.; Bhoj, E.J.; Verheij, J.B.G.M.; Wassink-Ruiter, J.S.K.; Reis, A.; Deshpande, C.; Gregor, A.; Hill-Karfe, K.; Silfhout, A.T.V.; Pfundt, R.; et al. De novo variants in MED12 cause X-linked syndromic neurodevelopmental disorders in 18 females. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). FG SYNDROME 1; FGS1; MIM Number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/305450 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDER, X-LINKED, WITH MARFANOID HABITUS.; LUFNS.; MIM Number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/309520 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). BLEPHAROPHIMOSIS-INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY SYNDROME, MKB TYPE.; MKBBS.; MIM Number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/300895 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Rubinato, E.; Rondeau, S.; Giuliano, F.; Kossorotoff, M.; Parodi, M.; Gherbi, S.; Steffan, J.; Jonard, L.; Marlin, S. MED12 missense mutation in a three-generation family. Clinical characterization of MED12-related disorders and literature review. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2020, 63, 103768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.P.; Feldman, J.; Mirzaa, G.M. MED12-Related Disorders. In GeneReviews® [Internet]; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J.H., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Strong, A.; Shen, K.M.; Cassiman, D.; Van Dyck, M.; Linhares, N.D.; Valadares, E.R.; Wang, T.; Pena, S.D.J.; Jaeken, J.; et al. De novo loss-of-function variants in X-linked MED12 are associated with Hardikar syndrome in females. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). HARDIKAR SYNDROME.; HDKR MIM.; Number: #301068. Available online: https://omim.org/entry/301068 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Kaya, N.; Colak, D.; Albakheet, A.; Al-Owain, M.; Abu-Dheim, N.; Al-Younes, B.; Al-Zahrani, J.; Mukaddes, N.M.; Dervent, A.; Al-Dosari, N.; et al. A novel X-linked disorder with developmental delay and autistic features. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 71, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prontera, P.; Ottaviani, V.; Rogaia, D.; Isidori, I.; Mencarelli, A.; Malerba, N.; Cocciadiferro, D.; Rolph, P.; Stangoni, G.; Vulto-van Silfhout, A.; et al. A novel MED12 mutation: Evidence for a fourth phenotype. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2016, 170, 2377–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Qian, Y.Q.; Yang, M.M.; Zhan, Q.T.; Chen, Y.; Xi, F.F.; Sagnelli, M.; Dong, M.Y.; Zhao, B.H.; Luo, Q. Whole-Exome Sequencing Revealed Mutations of MED12 and EFNB1 in Fetal Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 12-LIKE.; MED12L.; MIM Number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/611318 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Nizon, M.; Laugel, V.; Flanigan, K.M.; Pastore, M.; Waldrop, M.A.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Marom, R.; Xiao, R.; Gerard, A.; Pichon, O.; et al. Variants in MED12L, encoding a subunit of the mediator kinase module, are responsible for intellectual disability associated with transcriptional defect. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 2713–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 13; MED13; MIM number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/603808 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Snijders Blok, L.; Hiatt, S.M.; Bowling, K.M.; Prokop, J.W.; Engel, K.L.; Cochran, J.N.; Bebin, E.M.; Bijlsma, E.K.; Ruivenkamp, C.A.L.; Terhal, P.; et al. De novo mutations in MED13, a component of the Mediator complex, are associated with a novel neurodevelopmental disorder. Hum. Genet. 2018, 137, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). KABUKI SYNDROME 1; KABUK1; MIM number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/147920 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- De Nardi, L.; Faletra, F.; D’Adamo, A.P.; Bianco, A.M.R.; Athanasakis, E.; Bruno, I.; Barbi, E. Could the MED13 mutations manifest as a Kabuki-like syndrome? Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2021, 185, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivisano, M.; De Dominicis, A.; Micalizzi, A.; Ferretti, A.; Dentici, M.L.; Terracciano, A.; Calabrese, C.; Vigevano, F.; Novelli, G.; Novelli, G.; et al. MED13 mutation: A novel cause of developmental and epileptic encephalopathy with infantile spasms. Seizure 2022, 101, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, I.E.; Berkovic, S.; Capovilla, G.; Connolly, M.B.; French, J.; Guilhoto, L.; Hirsch, E.; Jain, S.; Mathern, G.W.; Moshé, S.L.; et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A.P.; Friend, K.; Rawlings, L.; Barnett, C.P. A de novo missense variant in MED13 in a patient with global developmental delay, marked facial dysmorphism, macroglossia, short stature, and macrocephaly. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2021, 185, 2586–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 13-LIKE.; MED13L.; MIM number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/608862 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Davis, M.A.; Larimore, E.A.; Fissel, B.M.; Swanger, J.; Taatjes, D.J.; Clurman, B.E. The SCF–Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase degrades MED13 and MED13L and regulates CDK8 module association with Mediator. Genes. Dev. 2013, 27, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muncke, N.; Jung, C.; Rüdiger, H.; Ulmer, H.; Roeth, R.; Hubert, A.; Goldmuntz, E.; Driscoll, D.; Goodship, J.; Schön, K.; et al. Missense mutations and gene interruption in PROSIT240, a novel TRAP240-like gene, in patients with congenital heart defect (transposition of the great arteries). Circulation 2003, 108, 2843–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadollahi, R.; Oneda, B.; Sheth, F.; Azzarello-Burri, S.; Baldinger, R.; Joset, P.; Latal, B.; Knirsch, W.; Desai, S.; Baumer, A.; et al. Dosage changes of MED13L further delineate its role in congenital heart defects and intellectual disability. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). PIERRE ROBIN SEQUENCE.; PRS.; MIM number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/261800 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Gordon, C.T.; Chopra, M.; Oufadem, M.; Alibeu, O.; Bras, M.; Boddaert, N.; Bole-Feysot, C.; Nitschké, P.; Abadie, V.; Lyonnet, S.; et al. MED13L loss-of-function variants in two patients with syndromic Pierre Robin sequence. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2018, 176, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbola, A.; Musante, L.; Callewaert, B.; Maciel, P.; Hu, H.; Isidor, B.; Picker-Minh, S.; Le Caignec, C.; Delle Chiaie, B.; Vanakker, O.; et al. Redefining the MED13L syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 23, 1308–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.M.L.; Dias, A.T.; Rocha, G.; Santos, H.; Soares, G.; Leão, M. Two novel pathogenic variants in MED13L: One familial and one isolated case. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2021, 65, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessenyei, B.; Balogh, I.; Mokánszki, A.; Ujfalusi, A.; Pfundt, R.; Szakszon, K. MED13L-related intellectual disability due to paternal germinal mosaicism. Mol. Case Stud. 2022, 8, a006124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 14; MED14; MIM number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/300182 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Lou, X.; Burrows, J.T.A.; Scott, I.C. Med14 cooperates with brg1 in the differentiation of skeletogenic neural crest. BMC Dev. Biol. 2015, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 16; MED16; MIM number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/604062 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Guillouet, C.; Agostini, V.; Baujat, G.; Cocciadiferro, D.; Pippucci, T.; Lesieur-Sebellin, M.; Georget, M.; Schatz, U.; Fauth, C.; Louie, R.J.; et al. Bi-allelic MED16 variants cause a MEDopathy with intellectual disability, motor delay, and craniofacial, cardiac, and limb malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 112, 829–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 17; MED17; MIM number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/603810 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Ryu, S.; Zhou, S.; Ladurner, A.G.; Tjian, R. The transcriptional cofactor complex CRSP is required for activity of the enhancer-binding protein Sp1. Nature 1999, 397, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaindl, A.M.; Passemard, S.; Kumar, P.; Kraemer, N.; Issa, L.; Zwirner, A.; Gerard, B.; Verloes, A.; Mani, S.; Gressens, P. Many roads lead to primary autosomal recessive microcephaly. Prog. Neurobiol. 2010, 90, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, R.; Straussberg, R.; Mandel, H.; Fattal-Valevski, A.; Ben-Zeev, B.; Naamati, A.; Shaag, A.; Zenvirt, S.; Konen, O.; Mimouni-Bloch, A.; et al. Infantile cerebral and cerebellar atrophy is associated with a mutation in the MED17 subunit of the transcription preinitiation mediator complex. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 87, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini, A.; Marchetti, D.; Izzi, C.; Cocco, I.; Pinelli, L.; Accorsi, P.; Iascone Maria, R.; Giordano, L. Expanding the phenotype of MED 17 mutations: Description of two new cases and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2018, 177, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattal-Valevski, A.; Ben Sira, L.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; Strausberg, R.; Bloch-Mimouni, A.; Edvardson, S.; Kaufman, R.; Chernuha, V.; Schneebaum Sender, N.; Heimer, G.; et al. Delineation of the phenotype of MED17-related disease in Caucasus-Jewish families. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2021, 32, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiullah, R.; Albalawi, A.M.; Alaradi, S.R.; Alluqmani, M.; Mushtaq, M.; Wali, A.; Basit, S. An expansion of phenotype: Novel homozygous variant in the MED17 identified in patients with progressive microcephaly and global developmental delay. J. Neurogenet. 2022, 36, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, S.; Saitsu, H.; Matsumoto, N. Distinct but milder phenotypes with choreiform movements in siblings with compound heterozygous mutations in the transcription preinitiation mediator complex subunit 17 (MED17). Brain Dev. 2016, 38, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 20; MED20; MIM number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/612915 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). BASAL GANGLIA DEGENERATION, INFANTILE-ONSET, WITH BRAIN ATROPHY.; IBGDA.; MIM Number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/616145 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Vodopiutz, J.; Schmook, M.T.; Konstantopoulou, V.; Plecko, B.; Greber-Platzer, S.; Creus, M.; Seidl, R.; Janecke, A.R. MED20 mutation associated with infantile basal ganglia degeneration and brain atrophy. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015, 174, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 23; MED23; MIM Number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/605042 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Hashimoto, S.; Boissel, S.; Zarhrate, M.; Rio, M.; Munnich, A.; Egly, J.M.; Colleaux, L. MED23 mutation links intellectual disability to dysregulation of immediate early gene expression. Science 2011, 333, 1161–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trehan, A.; Brady, J.M.; Maduro, V.; Bone, W.P.; Huang, Y.; Golas, G.A.; Kane, M.S.; Lee, P.R.; Thurm, A.; Gropman, A.L.; et al. MED23-associated intellectual disability in a non-consanguineous family. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2015, 167, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionel, A.C.; Monfared, N.; Scherer, S.W.; Marshall, C.R.; Mercimek-Mahmutoglu, S. MED23-associated refractory epilepsy successfully treated with the ketogenic diet. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2016, 170, 2421–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 25; MED25; MIM number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/610197 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Kazan, K. The Multitalented MEDIATOR. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). WARBURG MICRO SYNDROME 1; WARBM1; MIM number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/600118 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). KAUFMAN OCULOCEREBROFACIAL SYNDROME.; KOS.; MIM number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/244450 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). CEREBROOCULOFACIOSKELETAL SYNDROME 1; COFS1; MIM number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/214150 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). KAHRIZI SYNDROME.; KHRZ.; MIM number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/612713 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Basel-Vanagaite, L.; Smirin-Yosef, P.; Essakow, J.L.; Tzur, S.; Lagovsky, I.; Maya, I.; Pasmanik-Chor, M.; Yeheskel, A.; Konen, O.; Orenstein, N.; et al. Homozygous MED25 mutation implicated in eye-intellectual disability syndrome. Hum. Genet. 2015, 134, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, T.; Melo, U.S.; Pessoa, A.L.; Nobrega, P.R.; Kitajima, J.P.; Correa, I.; Zatz, M.; Kok, F.; Santos, S. Homozygous missense mutation in MED25 segregates with syndromic intellectual disability in a large consanguineous family. J. Med. Genet. 2015, 52, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). CHARCOT-MARIE-TOOTH DISEASE, AXONAL, TYPE 2B2; CMT2B2; MIM Number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/605589 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Leal, A.; Huehne, K.; Bauer, F.; Sticht, H.; Berger, P.; Suter, U.; Morera, B.; Del Valle, G.; Lupski, J.R.; Ekici, A.; et al. Identification of the variant Ala335Val of MED25 as responsible for CMT2B2: Molecular data, functional studies of the SH3 recognition motif and correlation between wild-type MED25 and PMP22 RNA levels in CMT1A animal models. Neurogenetics 2009, 10, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). BASEL-VANAGAITE-SMIRIN-YOSEF SYNDROME.; BVSYS.; MIM number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/616449 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Maini, I.; Errichiello, E.; Caraffi, S.G.; Rosato, S.; Bizzarri, V.; Pollazzon, M.; Trimarchi, G.; Contrò, G.; Cavirani, B.; Gelmini, C.; et al. Improving the phenotype description of Basel-Vanagaite-Smirin-Yosef syndrome, MED25-related: Polymicrogyria as a distinctive neuroradiological finding. Neurogenetics 2021, 22, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). MEDIATOR COMPLEX SUBUNIT 27; MED27; MIM number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/605044 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Maldonado, E.; Morales-Pison, S.; Urbina, F.; Jara, L.; Solari, A. Role of the Mediator Complex and MicroRNAs in Breast Cancer Etiology. Genes 2022, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Wang, K.; Li, T.; Gan, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. MED27 Variants Cause Developmental Delay, Dystonia, and Cerebellar Hypoplasia. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 89, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroofian, R.; Kaiyrzhanov, R.; Cali, E.; Zamani, M.; Zaki, M.S.; Ferla, M.; Tortora, D.; Sadeghian, S.; Saadi, S.M.; Abdullah, U.; et al. Biallelic MED27 variants lead to variable ponto-cerebello-lental degeneration with movement disorders. Brain 2023, 146, 5031–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASE 8; CDK8; MIM number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/603184 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Osman, S.; Mohammad, E.; Lidschreiber, M.; Stuetzer, A.; Bazsó, F.L.; Maier, K.C.; Urlaub, H.; Cramer, P. The Cdk8 kinase module regulates interaction of the mediator complex with RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calpena, E.; Hervieu, A.; Kaserer, T.; Swagemakers, S.M.A.; Goos, J.A.C.; Popoola, O.; Ortiz-Ruiz, M.J.; Barbaro-Dieber, T.; Bownass, L.; Brilstra, E.H.; et al. De Novo Missense Substitutions in the Gene Encoding CDK8, a Regulator of the Mediator Complex, Cause a Syndromic Developmental Disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, S.; Kato, M.; Hiraide, T.; Shiohama, T.; Goto, T.; Hojo, A.; Ebata, A.; Suzuki, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Chong, P.F.; et al. Comprehensive genetic analysis confers high diagnostic yield in 16 Japanese patients with corpus callosum anomalies. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 66, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASE 19; CDK19; MIM number: *. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/614720 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Chung, H.L.; Mao, X.; Wang, H.; Park, Y.J.; Marcogliese, P.C.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Burrage, L.C.; Liu, P.; Murdock, D.R.; Yamamoto, S.; et al. De Novo Variants in CDK19 Are Associated with a Syndrome Involving Intellectual Disability and Epileptic Encephalopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 106, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD). DEVELOPMENTAL AND EPILEPTIC ENCEPHALOPATHY 87; DEE87; MIM number: #. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/618916 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Zarate, Y.A.; Uehara, T.; Abe, K.; Oginuma, M.; Harako, S.; Ishitani, S.; Lehesjoki, A.E.; Bierhals, T.; Kloth, K.; Ehmke, N.; et al. CDK19-related disorder results from both loss-of-function and gain-of-function de novo missense variants. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, Y.; Mizuno, T.; Moriyama, K.; Ishiwata, H.; Kato, M.; Nakashima, M.; Mizuguchi, T.; Matsumoto, N. Cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in developmental and epileptic encephalopathy with a de novo CDK19 variant. Neurol Genet. 2020, 6, e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Yu, W.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X. A novel variant of CDK19 causes a severe neurodevelopmental disorder with infantile spasms. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2021, 7, a006082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Individual | Scan Age | Radiological Findings |

|---|---|---|

| A-II-1 | 1 month | Progressive global neurodegeneration and atrophy involving the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres |

| A-II-1 | 4 months | Progressive global neurodegeneration and atrophy involving the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres |

| A-II-1 | 2 years | Progressive global neurodegeneration and atrophy involving cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres with cerebral dysgyria | |

| A-II-1 | Fetus (31 weeks) | Progressive atrophy of intracranial structures with increasing extra-axial spaces, cerebral dysgyria, and marked cerebellar atrophy |

| A-II-1 | Fetus (34 weeks) | Progressive atrophy of intracranial structures with increasing extra-axial spaces, cerebral dysgyria, and marked cerebellar atrophy |

| B-II-1 | Not reported | Similar features of global brain underdevelopment with cerebral dysgyria and particular cerebellar atrophy |

| B-II-2 | Not reported | Similar features of global brain underdevelopment with cerebral dysgyria and cerebellar atrophy |

| B-II-1 | Not reported | Similar features of global brain underdevelopment with cerebral dysgyria, underdevelopment of white matter, and cerebellar atrophy |

| Condition | Genetic Basis | Clinical Features | Radiological Features | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG Syndrome Type 1 (FGS1) (MIM #305450) [27] | Mutation in MED12 | Intellectual disability, congenital hypotonia, distinctive facial features | Partial or complete agenesis of the corpus callosum | Role of MED12 in neurodevelopment |

| Nonspecific Intellectual Disability (NSID) | Genetic heterogeneity | Cognitive impairment without specific physical characteristics | Abnormalities of the corpus callosum; ventriculomegaly | Diverse genetic underpinnings |

| Lujan Syndrome (LS) (MIM #309520) [28] | Missense mutation in MED12 (p.Asn1007Ser) | Intellectual disability, marfanoid habitus, behavioral anomalies | Ventricular dilatation, corpus callosum abnormalities | Impact on brain structure and function |

| X-Linked Ohdo Syndrome (XLOS) (MIM #300895) [29] | Missense mutation in MED12 | Intellectual disability, distinctive facial features, and congenital heart defects | Distinctive changes in brain morphology (Seizures and corpus callosum dysgenesis) | Neurodevelopmental consequences |

| Features | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 10 Years | 4 Years | 36 Years |

| Motor Development | Delayed: independent sitting at 15 months, walking at 48 months | Development like patient 1, but more sociable | Slow development, progressive muscle atrophy, periods of agitation |

| Expressive Language | Limited: single words at 7 years, two-word phrases at 10 years | Parallel to Patient 1, but more sociable | Periods of agitation, language decline, and refusal of detailed psychiatric examination |

| Physical Anomalies | Microcephaly, slightly triangular face, flattened nasal bridge, bilateral epicanthic folds, bilateral nicked/crenelated ear lobes, pectus excavatum, partially fused fingers | Similar to Patient 1, but more sociable | Hypertelorism, bilateral cleft of ear lobes, pectus excavatum |

| Radiological Findings (7 years) | Mild signal changes bilaterally in dentate nuclei, tegmentum, cerebellar peduncle, and periaqueductal gray matter; mild ventricular enlargement and thinned corpus callosum | Not specified | Thinned corpus callosum, bilaterally enlarged lateral ventricles |

| Neurological Examinations (7 years) | Balance problems, poor muscle tone and strength, and no pathological reflexes | Not specified | Muscle weakness, refusal of a detailed psychiatric examination |

| Therapies | Not specified | Steroids for controlling West syndrome | Not specified |

| Study | Year | Population | MED17 Mutation | Clinical Symptoms | MRI Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaufman et al. [62] | 2010 | Israeli children of Caucasian descent | Homozygous missense | Progressive postnatal microcephaly, severe developmental delay | Extensive and pronounced cerebral and cerebellar atrophy, inadequate myelination, diminished thalamic size, and slender brainstem |

| Agostini et al. [63] | 2018 | Two adult sisters | Compound heterozygous | Progressive microcephaly, moderate cognitive impairment, epilepsy | Slight cerebellar vermis shrinkage, no cerebral atrophy |

| Hirabayashi et al. [66] | 2019 | Two unrelated brothers | Compound heterozygous | Nystagmus, opisthotonic posture, developmental delay, choreiform movements, hypotonia | Slight delays in myelination, anterior horn dilation, and mild cerebellar atrophy |

| Fattal-Valevski et al. [64] | 2020 | Unrelated Caucasian-Jewish families | Homozygous | Progressive microcephaly, severe developmental delays, diverse neurological symptoms | Significant cerebral and cerebellar atrophy, reduced white matter volume, delayed myelination, corpus callosum thinning, pronounced ventral pons flattening |

| Rafiullah et al. [65] | 2022 | Consanguineous family | Novel homozygous missense | Severe ID, seizures, progressive microcephaly | Mild atrophy, myelination defects |

| Study | Mutation | Clinical Manifestations | MRI Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lina Basel-Vanagaite et al. [80] | Tyr39Cys in MED25 | Profound intellectual disability, distinctive dysmorphic traits, congenital eye defects, and abnormalities of the corpus callosum | Abnormal hyperintense signals in the bilateral occipital periventricular white matter, thin corpus callosum |

| Figueiredo et al. [81] | c.418C>T, p.Arg140Trp in MED25 | Syndromic intellectual disability, distinct facial features not seen in parents or unaffected siblings | Not specified |

| I. Maini et al. [85] | Homozygous frameshift mutation in MED25 | Severe developmental retardation, diminished muscle tone, cardiac malformations, distinctive facial and limb deformities | Thin corpus callosum, enlargement of the lateral ventricles, bilateral perisylvian polymicrogyria |

| MED Subunit | MIM | Molecular Mechanism | Chromosomal Location | Clinical Features | MRI Findings | Key Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MED1 | *604311 | Gene/protein downregulation | 17q12 |

| - | Role in growth and differentiation. |

| MED8 | *607956 | SZT2 gene regulation | 1q23.1 | - | - | Neurological diseases; possible role in epileptogenesis. |

| MED11 | *612383 | Homozygous truncating mutation | 17p13.2 |

|

| Neurodegenerative disorder. |

| MED12 | *300188 | Gene missense and duplication mutations | Xq13.1 | Intellectual disability; hypotonia; macrocephaly; hyperactivity. | Abnormalities of the corpus callosum; ventriculomegaly | Neurodevelopmental disorders; autism disorders. |

| MED12L | *611318 | Deletions, duplications, nonsense mutations, frameshifts, and splicing mutations | 3q25.1 | Intellectual disability; developmental delay; attention deficit with hyperactivity; sleep disorders; hypotonia. | Corpus callosum abnormalities. | Autism disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| MED13 | *603808 | Truncating, missense mutations, and a single amino acid deletion | 17q23.2 | Intellectual and developmental delays, language impairments, focal epileptic crisis, and infantile spasms. | Frontal atrophy; dysmorphic corpus callosum. | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathies |

| MED13L | *608771 | Translocations, deletions, and copy number mutations | 12q24.21 | Intellectual disability; cardiac defects; distinctive facial features | White matter anomalies; abnormalities of the corpus callosum; ventricular dilatation | Pierre Robin’s syndrome; transposition of the Great vessels |

| MED14 | *300182 | Unknown mutations | Xp11.4 | - | - | Alteration in neural crest cell differentiation |

| MED 16 | *604062 | Homozygous truncating variant (novel) | 19p13.3 |

|

| Novel MEDopathy linking MED16 to severe neurodevelopmental disorder |

| MED17 | *603810 | Homozygous and heterozygous mutation | 11q21 | Microcephaly; intellectual disability; epilepsy; ataxia | Cerebral and cerebellar atrophy; inadequate myelination; corpus callosum thinning. | Severe developmental delays. |

| MED20 | *612915 | Gene mutations | 17q22 | Spasticity; dystonia | Cerebral and cerebellar atrophy; basal ganglia hyperintensity | Neurodegenerative movement disorder. |

| MED23 | *605042 | Homozygous and heterozygous mutation | 6p21.1 | Intellectual disability | Pontine hypoplasia; corpus callosum abnormalities; hypomyelination | Epilepsy; developmental delays. |

| MED25 | *610197 |

| 19q13.33 | Intellectual disability; eye abnormalities; congenital defects. | Abnormal hyperintense signals in bilateral occipital periventricular white matter, abnormalities of the corpus callosum | Multiple syndromes involving intellectual disability and eye/brain abnormalities; Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease [82] |

| MED27 | *605044 | Biallelic gene mutations | 9q34.13 | Intellectual impairment; developmental delays; axial hypotonia; distal spasticity; dystonic movements | Abnormalities of cerebellum and corpus callosum; simplification of the cortical gyri; “hot cross bun” sign | Neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. |

| CDK8 | *603184 | Missense substitutions | 13q12.13 | Hypotonia; developmental delays; neurological, sensory, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and facial abnormalities. | Agenesis or thinning of the corpus callosum | Neurodevelopmental disorders overlap with other neurological syndromes |

| CDK19 | *614720 | Heterozygous de novo missense variants (hotspots p.Gly28, p.Tyr32, p.Thr196) | 6q21 |

|

| Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathy 87 (DEE87); kinase dysregulation with dual loss- and gain-of-function; likely “synaptopathy” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fazio, A.; Leonardi, R.; Aliotta, L.; Lo Bianco, M.; Anastasio, G.; Messina, G.; Spatola, C.; Foti, P.V.; Palmucci, S.; Basile, A.; et al. Genetic, Clinical and Neuroradiological Spectrum of MED-Related Disorders: An Updated Review. Genes 2025, 16, 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121444

Fazio A, Leonardi R, Aliotta L, Lo Bianco M, Anastasio G, Messina G, Spatola C, Foti PV, Palmucci S, Basile A, et al. Genetic, Clinical and Neuroradiological Spectrum of MED-Related Disorders: An Updated Review. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121444

Chicago/Turabian StyleFazio, Alessandro, Roberta Leonardi, Lorenzo Aliotta, Manuela Lo Bianco, Gennaro Anastasio, Giuseppe Messina, Corrado Spatola, Pietro Valerio Foti, Stefano Palmucci, Antonio Basile, and et al. 2025. "Genetic, Clinical and Neuroradiological Spectrum of MED-Related Disorders: An Updated Review" Genes 16, no. 12: 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121444

APA StyleFazio, A., Leonardi, R., Aliotta, L., Lo Bianco, M., Anastasio, G., Messina, G., Spatola, C., Foti, P. V., Palmucci, S., Basile, A., Ruggieri, M., & David, E. (2025). Genetic, Clinical and Neuroradiological Spectrum of MED-Related Disorders: An Updated Review. Genes, 16(12), 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121444