What Do Single-Cell Models Already Know About Perturbations?

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A simple, model-agnostic gradient probe that turns any single-cell decoder into a simulator of infinitesimal perturbations over its outputs—no need for labeled samples or tailored architectures.

- Arbitrary perturbation types can be added by training lightweight task heads.

- Pretrained models at scale reveal flows aligned with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) when probing an scVI decoder, enabling hypothesis testing without task-specific training.

- Evaluating gene set analyses with an LLM (large language model) opens a new direction for understanding the quality of gene set enrichments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Preprocessing and Filtering

| Dataset | Cells | Transcripts | HVGs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irf8 knockout M. m. brains | 13,931 | 14,581 | 3451 | Van Hove et al. [10] |

| Cardiotoxin M. m. injury | 53,230 | 21,809 | 1950 | Takada et al. [11] |

| C. e. embryogenesis | 85,951 | 17,711 | 1832 | Packer et al. [12] |

| CELL GENE islet subset | 10,000 | 8000 | n/a | CZI Cell Science Program et al. [14] |

2.3. Base Model: Negative Binomial -VAE

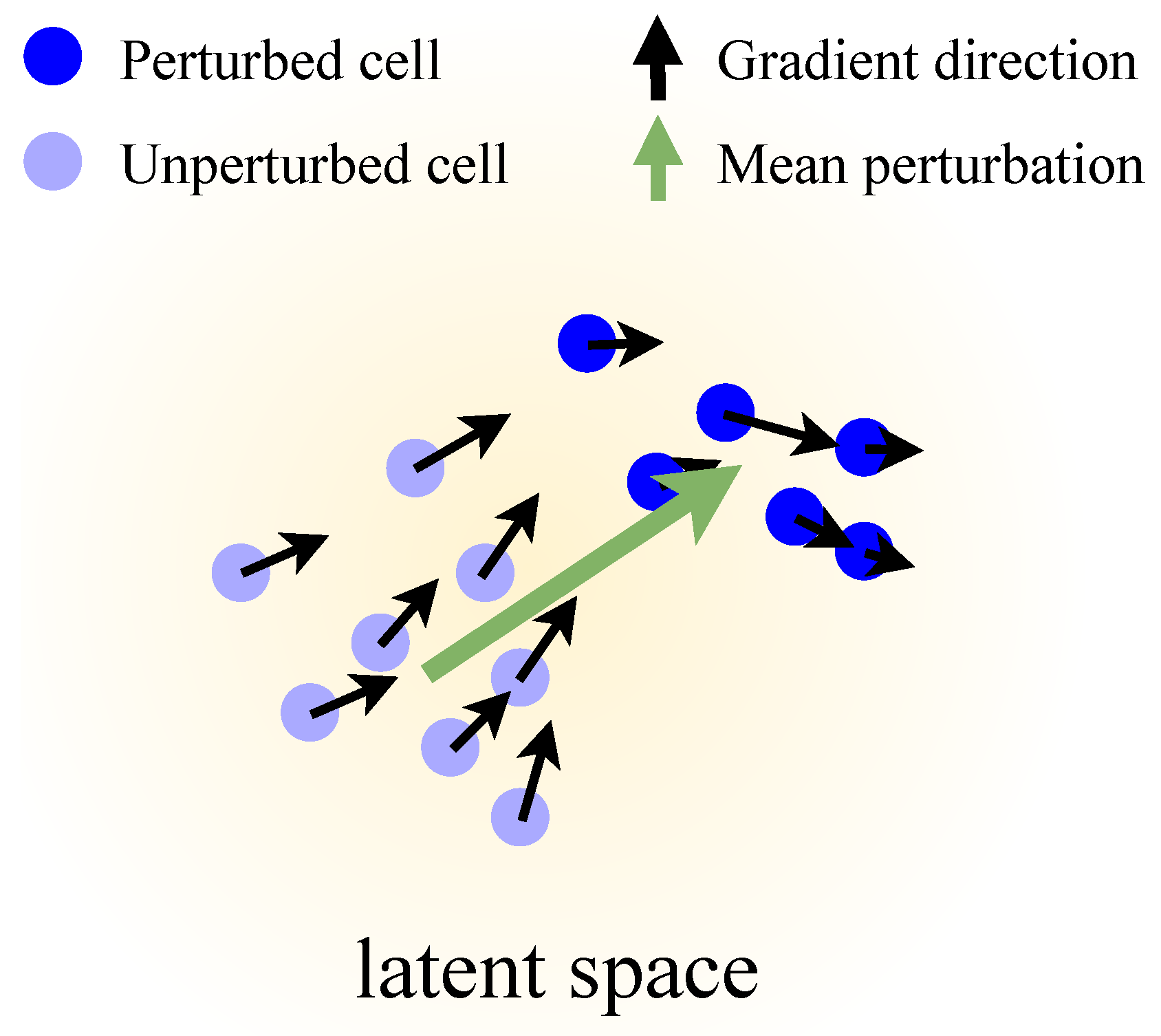

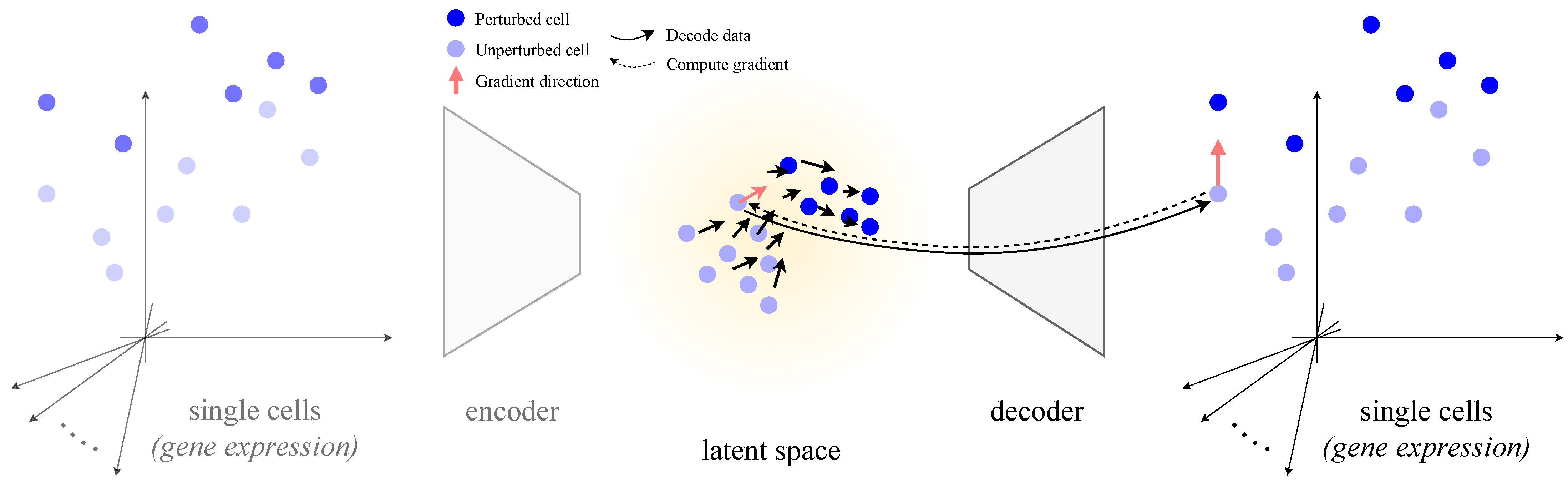

2.4. Core Idea: Perturbations from Decoder Gradients

2.5. Scoring Genes by Their Alignment with a Healthy-to-Disease Axis

2.6. Evaluating Pathways for a Complex Disease

Prompt 1. You have an expert perspective in bioinformatics. Is [pathway] highly relevant for type 2 diabetes mellitus in Mus musculus? Answer with Yes or No. Afterwards, describe shortly your explanation for whether the pathway involves type 2 diabetes, providing references for your claims.

Prompt 2. You have an expert perspective in bioinformatics. Your task is to very concisely judge whether a pathway is relevant for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) in Mus musculus. When asked whether [pathway] is highly relevant for T2D in Mus musculus, these were your answers from three distinct runs:

Answer 1: [answer 1]

Answer 2: [answer 2]

Answer 3: [answer 3]

Now give your final critical verdict with a Yes or No, and describe very concisely your explanation (with a few sentences at most), using correct scientific references.

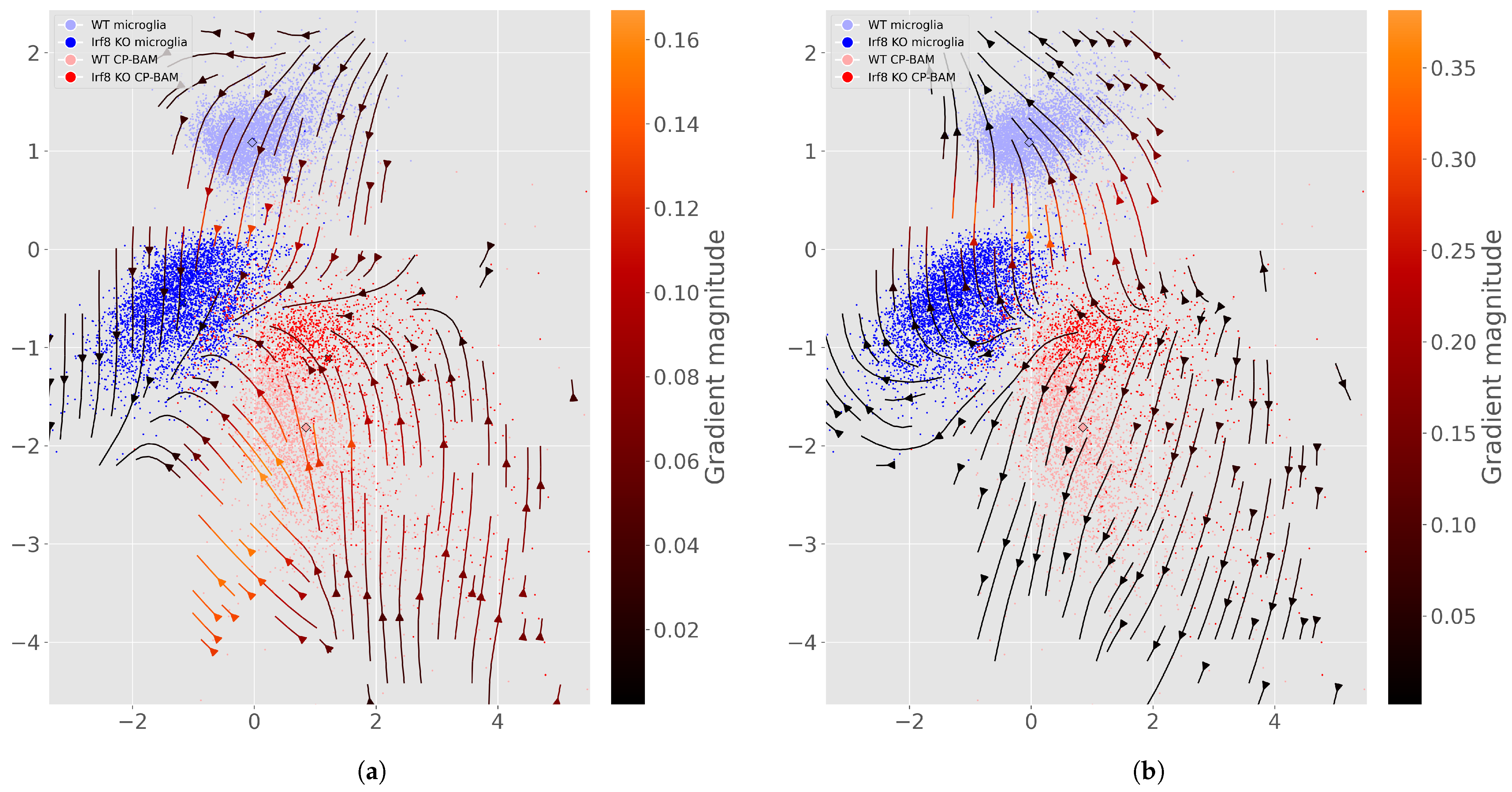

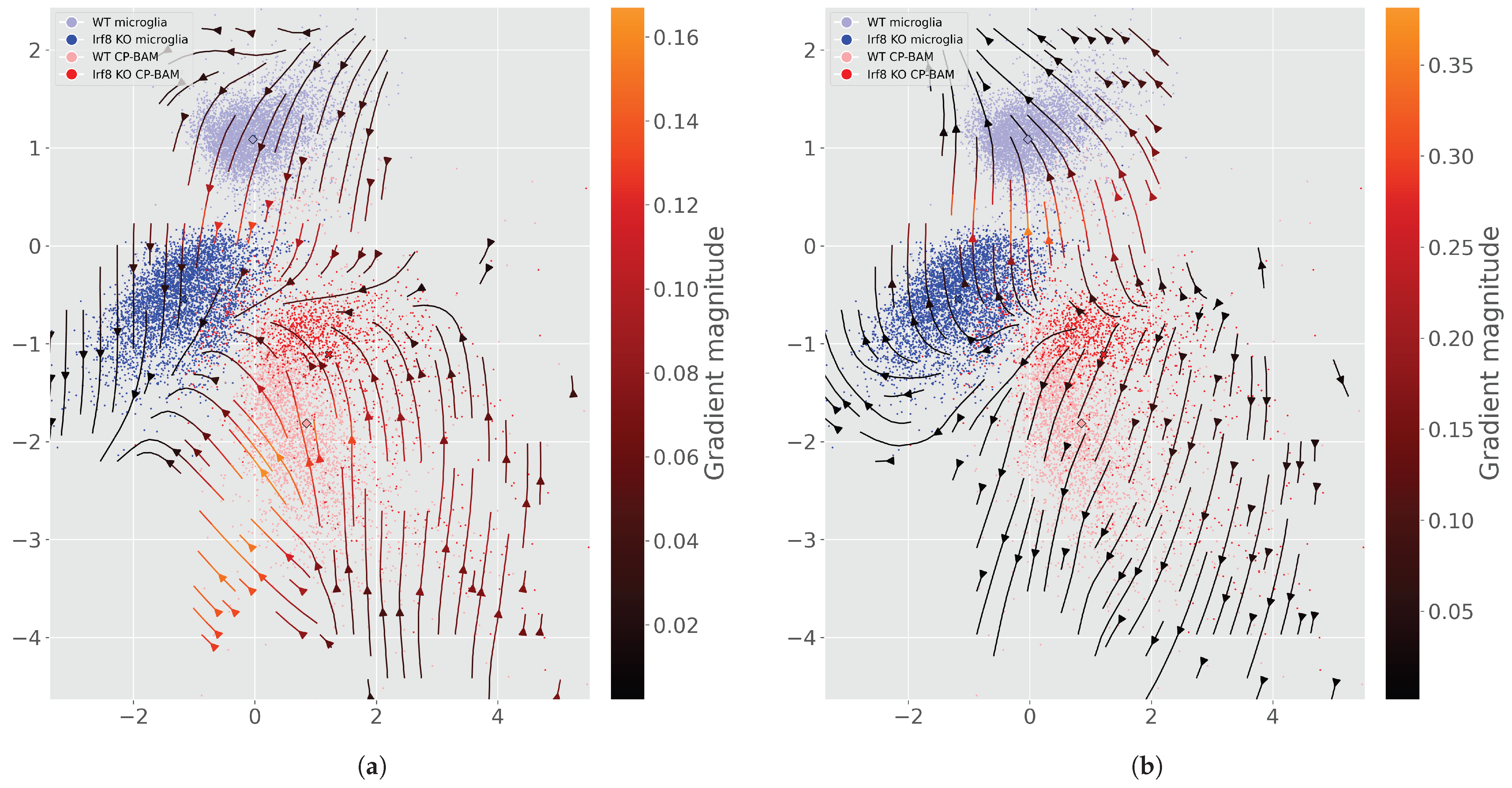

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Single-Cell Models Encode Perturbation Effects Without Using Labels

4.2. Auxiliary Outputs Extend to Treatment and Time

4.3. Flow Maps Scale to High-Dimensional Latents and Can Improve Projections

4.4. Type 2 Diabetes: Probing a Pretrained Model at Scale

4.5. Output Features Can Be Scored According to an Observed Perturbation

4.6. Summary and Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cKO | conditional knockout |

| C. e. | Caenorhabditis elegans |

| CP-BAM | choroid-plexus border-associated macrophages |

| FDR | false discovery rate |

| HVG | highly variable genes |

| KL | Kullback–Leibler divergence |

| LLM | large language model |

| M. m. | Mus musculus |

| NB | negative binomial |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| scRNA-seq | single-cell RNA sequencing |

| scVI | single-cell variational inference (model name) |

| T2D | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| UMAP | uniform manifold approximation and projection |

| UMI | unique molecular identifier |

| VAE | variational autoencoder |

| WT | wild type |

Appendix A. On Using a Pretrained scVI Model

Rationale. Our perturbation flows require , where is the decoder output for gene i (or an auxiliary head). The usual scVI model API makes this impossible as it detaches tensors and hides intermediate objects. However, calling the internal m.module.generative method for a model m keeps the computation graph intact. We utilize this function to make a minimal decoder forward pass.

Minimal Decode and Gradient Functions (Pseudocode)

- def decode(z, library, batch_idx):

- def grad_wrt_i(z, i, library, batch_idx):

Appendix B. Tabular Overview of Trained Models

| Train Set | Test Set | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instance | ARI | RMSE | MAE | Task | ARI | RMSE | MAE | Task |

| Irf8 cKO | ± 0.02 | ± 0.00 | ± 0.00 | − | ± 0.02 | ± 0.00 | ± 0.00 | − |

| 32D Irf8 cKO | ± 0.02 | ± 0.00 | ± 0.00 | − | ± 0.17 | ± 0.00 | ± 0.00 | − |

| Cardiotoxin | ± 0.05 | ± 0.00 | ± 0.00 | ± 0.00 | ± 0.05 | ± 0.00 | ± 0.00 | ± 0.00 |

| Embryogenesis | ± 0.04 | ± 0.01 | ± 0.00 | ± 3.81 | ± 0.04 | ± 0.01 | ± 0.00 | ± 1.75 |

Appendix C. Computing Alignment Scores

Appendix D. Pathway Relevance According to LLM AI Agents

| Pathway | Verdict | Explanation | Relevant Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins | Yes (3/3) | There is experimental and transcriptomic evidence in mouse and human islets linking cytoplasmic (and mitochondrial) ribosomal proteins and ribosome biogenesis to -cell protein synthesis, mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired insulin secretion and dysregulated insulin/AKT signaling — mechanisms directly relevant to T2D pathogenesis in Mus musculus. | Ribosomal biogenesis regulator DIMT1 controls -cell protein synthesis, mitochondrial function, and insulin secretion (2022), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35148993/. Mitoribosome insufficiency in cells is associated with type 2 diabetes-like islet failure (2022), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35804190/. Ribosomal Protein Mutations Induce Autophagy through S6 Kinase Inhibition of the Insulin Pathway (2014), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4038485/. |

| Dravet syndrome Scn1a A1783V point mutation model | No (0/3) | The Scn1a A1783V (Nav1.1) Dravet mouse is a CNS-focused loss-of-function epilepsy model with published phenotypes confined to brain/behavior, seizures and respiratory dysfunction; there is no evidence this SCN1A -subunit variant perturbs pancreatic -cell function or produces insulin resistance/T2D in mouse. Voltage-gated Na+ channel isoforms relevant to islet excitation–secretion are Scn3a/Scn9a ( subunits) and the subunit Scn1b, not Scn1a, and loss/variation in those genes — not SCN1A A1783V — has been linked to altered insulin/glucagon secretion. | Na+ current properties in islet - and -cells reflect cell-specific Scn3a and Scn9a expression (2014), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25172946/. Sodium channel 1 regulatory subunit deficiency reduces pancreatic islet glucose-stimulated insulin and glucagon secretion (2008), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2654754/. Dravet variant SCN1A A1783V impairs interneuron firing predominantly by altered channel activation (2021), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34776868/. Proteomic signature of the Dravet syndrome in the genetic Scn1a-A1783V mouse model (2021), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34144125/. |

| mRNA processing | Yes (3/3) | Strong experimental and genetic evidence in mice (and conserved mammalian mechanisms) shows mRNA processing — especially alternative splicing, RNA-binding proteins and m6A RNA modification — directly regulates insulin production, -cell function and insulin signalling, and perturbations produce glucose-homeostasis defects and diabetes-like phenotypes in Mus musculus. | N6-adenosine methylation controls the translation of insulin mRNA (2023), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11756593/. Haplo-Insufficiency of the Insulin Receptor in the presence of a splice-site mutation in Ppp2r2a results in a novel digenic mouse model of type 2 diabetes (2018), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5947768/. mRNA Processing: An Emerging Frontier in the Regulation of Pancreatic Cell Function (2020), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7490333/. |

| Serotonin and anxiety | Yes (3/3) | Strong, mechanistic mouse data show serotonergic signaling directly regulates pancreatic -cell function (TPH1, Htr3a/Htr2b) and central 5-HT receptors (Htr2c in POMC neurons) control glucose homeostasis; anxiety/stress-related alterations in 5-HT circuits in mouse models further modulate glycemia and insulin sensitivity, supporting high relevance of the serotonin–anxiety axis to T2D in Mus musculus. | Serotonin Regulates Adult -Cell Mass by Stimulating Perinatal -Cell Proliferation (2019), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6971487/. Functional role of serotonin in insulin secretion in a diet-induced insulin-resistant state (2015), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25426873/. Serotonin 2C receptors in pro-opiomelanocortin neurons regulate energy and glucose homeostasis (2013), https://www.jci.org/articles/view/70338. |

| Estrogen signaling | Yes (3/3) | Strong experimental evidence in Mus musculus shows estrogen signaling (primarily via ER, also ER/GPER) modulates hepatic and muscle insulin sensitivity, suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis, preserves -cell lipid homeostasis/function and prevents diet- or ovariectomy-induced insulin resistance — mechanisms directly relevant to T2D pathogenesis in mice. | Estrogen Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Suppresses Gluconeogenesis via the Transcription Factor Foxo1 (2018), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30487265/. Estrogen signaling prevents diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance in male mice with obesity (2014), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24691030/. Estrogen receptor activation reduces lipid synthesis in pancreatic islets and prevents cell failure in rodent models of type 2 diabetes (2011), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21747171/. Estrogen signaling pathway — Mus musculus (KEGG mmu04915), https://www.kegg.jp/pathway/mmu04915. |

| Metapathway biotransformation | No (1/3) | Metapathway biotransformation (phase I/II xenobiotic metabolism) is a hepatic/cellular detoxification module that is reproducibly altered in mouse models of obesity/T2D and can modulate insulin sensitivity (e.g., CYP epoxygenases/EETs), but it is not a core insulin-signalling or glucose-homeostasis pathway driving T2D in Mus musculus. Thus it is indirectly relevant and may modify disease severity, but it is not “highly” relevant as a primary T2D pathway. | Metapathway biotransformation (WP1251) — Mus musculus (2024), https://www.wikipathways.org/pathways/WP1251.html. Cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids contribute to insulin sensitivity in mice and in humans (2017), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28352940/. CYP2J2 attenuates metabolic dysfunction in diabetic mice by reducing hepatic inflammation via the PPAR (2015), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4329496/. |

| Exercise-induced circadian regulation | Yes (3/3) | Strong experimental evidence in Mus musculus shows (1) timed exercise entrains peripheral clocks in muscle and liver and modifies CLOCK/BMAL1/PER2 and SIRT1–NAD+ pathways, (2) chrono-exercise alters insulin sensitivity, GLUT4-mediated glucose uptake and mitochondrial quality in diabetic mouse models, and (3) circadian disruption causes glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in mice—together supporting high relevance of exercise-induced circadian regulation for T2D in mouse. | Chrono-Aerobic Exercise Optimizes Metabolic State in DB/DB Mice through CLOCK–Mitophagy–Apoptosis (2022), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36012573/. Aerobic exercise timing affects mitochondrial dynamics and insulin resistance by regulating the circadian clock protein expression and NAD+-SIRT1-PPAR-MFN2 pathway in the skeletal muscle of high-fat-diet-induced diabetes mice (2024), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39715985/. Circadian Disruption across Lifespan Impairs Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Sensitivity in Adult Mice (2023), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38393018/. Skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity shows circadian rhythmicity which is independent of exercise training status (2018), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6121032/. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (2021), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8939263/. |

Appendix E. Additional Perturbation Flow and Latent Space Figures

References

- Hicks, S.C.; Teng, M.; Irizarry, R.A. On the widespread and critical impact of systematic bias and batch effects in single-cell RNA-Seq data. BioRxiv 2015, 10, 025528. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, R.; Gayoso, A.; Yosef, N. Enhancing scientific discoveries in molecular biology with deep generative models. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2020, 16, e9198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønbech, C.H.; Vording, M.F.; Timshel, P.N.; Sønderby, C.K.; Pers, T.H.; Winther, O. scVAE: Variational auto-encoders for single-cell gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 4415–4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotfollahi, M.; Wolf, F.A.; Theis, F.J. scGen predicts single-cell perturbation responses. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfollahi, M.; Naghipourfar, M.; Theis, F.J.; Wolf, F.A. Conditional out-of-distribution generation for unpaired data using transfer VAE. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, i610–i617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimoto, K.; Stringa, B.; Hoffmann, C.M.; Jindal, K.; Solnica-Krezel, L.; Morris, S.A. Dissecting cell identity via network inference and in silico gene perturbation. Nature 2023, 614, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunne, C.; Stark, S.G.; Gut, G.; Del Castillo, J.S.; Levesque, M.; Lehmann, K.V.; Pelkmans, L.; Krause, A.; Rätsch, G. Learning single-cell perturbation responses using neural optimal transport. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 1759–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Jiang, R. scPRAM accurately predicts single-cell gene expression perturbation response based on attention mechanism. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, D.; Palla, G.; Lange, M.; Klein, M.; Piran, Z.; Gander, M.; Meng-Papaxanthos, L.; Sterr, M.; Saber, L.; Jing, C.; et al. Mapping cells through time and space with moscot. Nature 2025, 638, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hove, H.; Martens, L.; Scheyltjens, I.; De Vlaminck, K.; Pombo Antunes, A.R.; De Prijck, S.; Vandamme, N.; De Schepper, S.; Van Isterdael, G.; Scott, C.L.; et al. A single-cell atlas of mouse brain macrophages reveals unique transcriptional identities shaped by ontogeny and tissue environment. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, N.; Takasugi, M.; Nonaka, Y.; Kamiya, T.; Takemura, K.; Satoh, J.; Ito, S.; Fujimoto, K.; Uematsu, S.; Yoshida, K.; et al. Galectin-3 promotes the adipogenic differentiation of PDGFRα+ cells and ectopic fat formation in regenerating muscle. Development 2022, 149, dev199443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, J.S.; Zhu, Q.; Huynh, C.; Sivaramakrishnan, P.; Preston, E.; Dueck, H.; Stefanik, D.; Tan, K.; Trapnell, C.; Kim, J.; et al. A lineage-resolved molecular atlas of C. elegans embryogenesis at single-cell resolution. Science 2019, 365, eaax1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- scvi-tools Model Hub; CELL×GENE Census. SCVI Model Trained on the CELL×GENE Discover Census (Mus musculus)—Snapshot 2024-02-12. 2024. Available online: https://cellxgene-contrib-public.s3.amazonaws.com/models/scvi/2024-02-12/mus_musculus/model.pt (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- CZI Cell Science Program; Abdulla, S.; Aevermann, B.; Assis, P.; Badajoz, S.; Bell, S.M.; Bezzi, E.; Cakir, B.; Chaffer, J.; Chambers, S.; et al. CZ CELLxGENE Discover: A single-cell data platform for scalable exploration, analysis and modeling of aggregated data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D886–D900. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, I.; Matthey, L.; Pal, A.; Burgess, C.; Glorot, X.; Botvinick, M.; Mohamed, S.; Lerchner, A. beta-vae: Learning basic visual concepts with a constrained variational framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.D.; Smyth, G.K. Moderated statistical tests for assessing differences in tag abundance. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2881–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshlack, A.; Robinson, M.D.; Young, M.D. From RNA-seq reads to differential expression results. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.; Regier, J.; Cole, M.B.; Jordan, M.I.; Yosef, N. Deep generative modeling for single-cell transcriptomics. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerregaard, A. Save the Mice: In-Silico Perturbation of Genes in Deep Generative Models. Master’s Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, V.; Krogh, A. The Deep Generative Decoder: MAP estimation of representations improves modelling of single-cell RNA data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerregaard, A.; Hauberg, S.; Krogh, A. Riemannian generative decoder. In Proceedings of the ICML 2025 Workshop on Generative AI and Biology, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ergen, C.; Amiri, V.V.P.; Kim, M.; Kronfeld, O.; Streets, A.; Gayoso, A.; Yosef, N. Scvi-hub: An actionable repository for model-driven single-cell analysis. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 1836–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizarraras, J.M.; Liao, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Pico, A.R.; Zhang, B. WebGestalt 2024: Faster gene set analysis and new support for metabolomics and multi-omics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W415–W421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Balcı, H.; Hanspers, K.; Coort, S.L.; Martens, M.; Slenter, D.N.; Ehrhart, F.; Digles, D.; Waagmeester, A.; Wassink, I.; et al. WikiPathways 2024: Next generation pathway database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D679–D689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashcroft, F.M.; Rorsman, P. Diabetes mellitus and the β cell: The last ten years. Cell 2012, 148, 1160–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, R.H.; Cherrington, A.D. Glucagonocentric restructuring of diabetes: A pathophysiologic and therapeutic makeover. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bjerregaard, A.; Prada-Luengo, I.; Das, V.; Krogh, A. What Do Single-Cell Models Already Know About Perturbations? Genes 2025, 16, 1439. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121439

Bjerregaard A, Prada-Luengo I, Das V, Krogh A. What Do Single-Cell Models Already Know About Perturbations? Genes. 2025; 16(12):1439. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121439

Chicago/Turabian StyleBjerregaard, Andreas, Iñigo Prada-Luengo, Vivek Das, and Anders Krogh. 2025. "What Do Single-Cell Models Already Know About Perturbations?" Genes 16, no. 12: 1439. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121439

APA StyleBjerregaard, A., Prada-Luengo, I., Das, V., & Krogh, A. (2025). What Do Single-Cell Models Already Know About Perturbations? Genes, 16(12), 1439. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121439