1. Introduction

The genus

Sorbus (Rosaceae) comprises a diverse group of temperate woody plants with increasing promise for agricultural and food applications. Several

Sorbus species, including

S. domestica,

S. aucuparia, and

S. aria, produce edible fruits that are rich in phenolic compounds, flavonoids, anthocyanins, and organic acids that contribute to their antioxidant, nutraceutical, and functional value [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These bioactive properties highlight the potential of

Sorbus spp. as alternative fruit crops that can be cultivated under marginal environmental conditions, supporting diversification and sustainability in temperate horticulture [

5].

Despite this potential, the agricultural utilization of

Sorbus species is limited by biological constraints, including irregular seed germination, low seed viability, and the low success rate of conventional vegetative propagation methods such as grafting or cutting [

6,

7]. In vitro micropropagation provides a practical solution by enabling rapid clonal multiplication, producing disease-free plants, and maintaining uniform propagation material for orchard establishment and breeding purposes [

8,

9].

In addition to supporting agricultural production, micropropagation also plays an essential role in the ex situ conservation of woody species and valuable cultivars. This ensures the long-term maintenance of valuable germplasm for breeding and restoration programs [

10,

11,

12]. However, developing reproducible micropropagation systems for woody plants is challenging due to high levels of phenolic oxidation, recalcitrance to rooting, and genotype-specific responses to culture media and plant growth regulators [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Advances such as temporary immersion systems and optimized cytokinin/auxin ratios have improved shoot multiplication and rooting efficiency in several fruit trees, including those in the

Prunus genus and

S. domestica [

17,

18].

Micropropagation is widely used in fruit crops such as apple, pear, and cherry but has been less explored in

Sorbus spp., despite similar propagation challenges and agricultural potential [

7,

19].

Protocols for microclonal propagation were initially developed for economically important species of the genus

Sorbus. These species hold significant value from both economic and industrial value, particularly the valuable timber species whose wood is used in the furniture industry and ornamental horticulture. Examples include

S. torminalis,

S. aucuparia, and

S. domestica [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Material maintained in Czech pomological germplasm collections in the Research and Breeding Institute of Pomology Holovousy Ltd. (RBIP) under the cultivar name ‘Discolor’ represents a long-established, morphologically stable sweet rowanberry genotype. Based on comparative observations and the current understanding of hybridization processes in Euro-Asian

Sorbus taxa [

22], ‘Discolor’ can be considered as part of the

Sorbus aucuparia/

S. discolor complex.

The rowanberry ‘Discolor’ is valued in Czech fruit genetic-resource collections for its edible berries and favorable sensory attributes. It is examined in terms of content of phenolic compounds, flavonoids and other antioxidants [

4]. These traits, combined with its striking autumn foliage, underscore both its horticultural appeal and its potential as a source of functional food ingredients and breeding material for rowanberry improvement programs.

However, efficient in vitro propagation methods for rowanberry ‘Discolor’ variety have yet to be described. Establishing a reliable micropropagation system is essential for maintaining genetically valuable clones, ensuring pathogen-free propagation material, and supporting both breeding and conservation objectives [

9]. Previous in vitro studies on related Sorbus species, such as

S. aucuparia and

S. domestica, have demonstrated that optimizing the combination of cytokinin and auxin is critical for successful shoot initiation, proliferation, and rooting [

7,

18].

Micropropagation trials with ‘Discolor’ began in January 2012 as part of a comprehensive strategic initiative to conserve rare and valuable berry fruit germplasm for agricultural use. This initiative aimed at the future utilization of these plants in commercial cultivation and breeding programs tailored to the diverse fruit-growing sector. After the in vitro propagation and root development stages, the plantlets were acclimated gradually and grown under greenhouse conditions for two years before being transplanted into the field. After a prolonged juvenile period, the plants began fruiting. Over five consecutive years of fruit collection, consistent the fruit coloration and an absence of somaclonal variation were confirmed, suggesting that the applied micropropagation methodology did not induce genetic alterations. After this was confirmed, the micropropagation dataset underwent detailed statistical analysis in 2025.

The objectives of this study were therefore to develop an in vitro propagation protocol for the rowanberry ‘Discolor’ cultivar by (i) defining the optimal combinations of media and plant growth regulators for shoot initiation and multiplication, and (ii) optimizing rooting conditions in controlled culture environments. Factorial experiments were conducted using different cytokinins and auxin treatments to assess their influence on proliferation and root induction.

These results are expected to establish the first methodological framework for the in vitro propagation of the ‘Discolor’ rowanberry, which will contribute to the long-term conservation, selection, and agricultural utilization of the Sorbus genus worldwide.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Vitro Culture Initiation

The rowanberry cultivar ‘Discolor’ used in this study originated in Czech fruit germplasm collections as standard, tree-form specimens grafted onto European rowan

S. aucuparia seedling rootstocks. It is characterized by the distinctly light red color of its fruits. Micropropagation experiments were conducted at RBIP. In the winter, dormant shoots were collected from healthy mother plants and rinsed with running tap water to remove surface debris and microorganisms. The shoots were then trimmed into 20–25 cm segments, with diagonal cuts on the basal ends. The segments were placed in water at 22 °C for 2–3 weeks to promote bud sprouting. Next, 52 protruding shoot tips (5–10 mm) with a differentiated apical meristem were aseptically excised in a laminar flow cabinet. Bud scales and any leaf primordia were removed. The resulting explants were surface-sterilized in a 0.15% mercuric chloride solution containing Tween 20 for 1 min, followed by a rinse with sterile distilled water. Five explants were placed in each 100 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 25 mL of agar solidified Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium [

24]. The medium contained 30 g L

−1 sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) and 7 g L

−1 agar type A (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). prior to adding the agar and autoclaving at 120 °C and 100 kPa for 15 min, the pH of the medium was adjusted to a value of 5.8. To initiate the culture, the medium was supplemented with 1.5 mg L

−1 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) and 0.1 mg L

−1 indole-3-butyric acid (IBA). After 24 h, explants exuding phenolics were transferred to fresh medium and malformed or contaminated cultures were discarded. One week after sterilization, the cultures were examined for contamination and survival. Developing shoots were subcultured every four weeks for six passages to establish a uniform stock for multiplication experiments.

From the beginning of the initiation phase, all cultures were maintained in a high-capacity cultivation room at a temperature of 22 ± 1 °C. Cultures were exposed to cool, neutral-white fluorescent light (Sylvania F18W/840-TB, Erlangen, Germany) at an intensity of 60 μmol·m−2·s−1 and with a photoperiod of 16 h of light and 8 h of darkness. The light sources were positioned 30 cm above the cultures. All manipulations were performed aseptically in a laminar flow cabinet.

2.2. Multiplication Phase

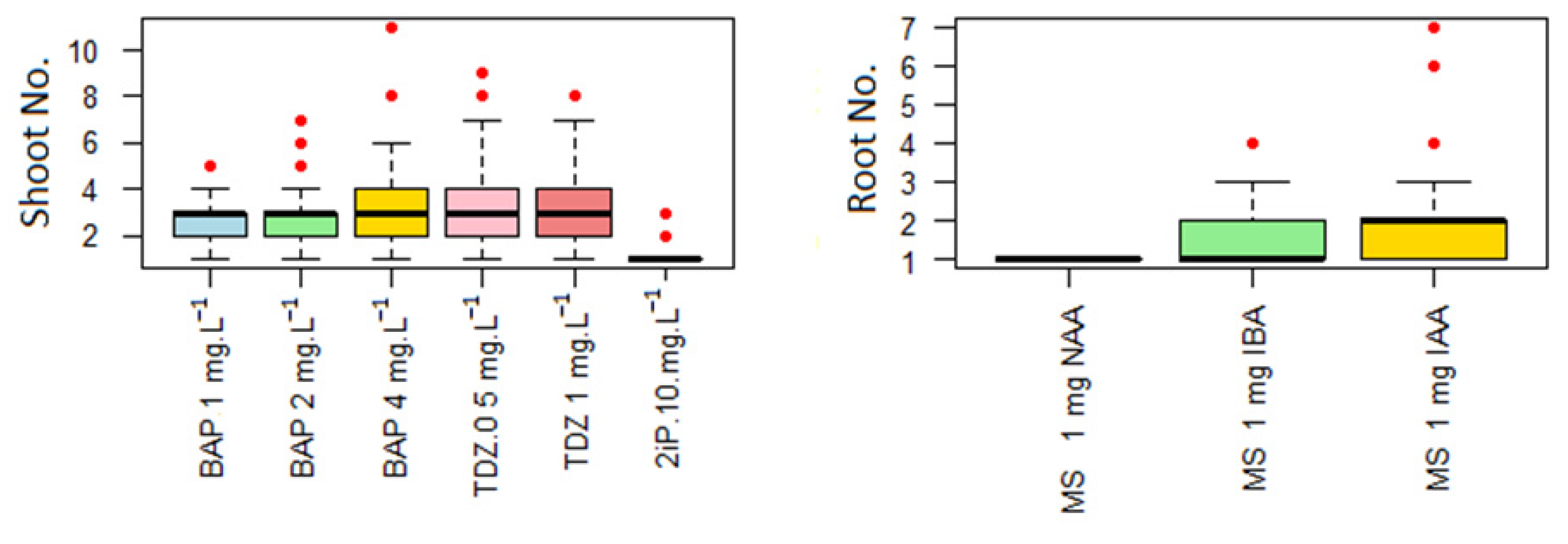

To promote multiplication, actively growing shoots (10–15 mm including the apex) were excised from stock cultures 6 months after culture initiation and transferred to a fresh MS medium supplemented with 30 g L−1 sucrose and 7 g L−1 agar (pH 5.8), under the same cultivation conditions as in the initiation phase. We studied the effect of various concentrations of 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP, 1, 2, and 4 mg L−1), thidiazuron (TDZ, 0.5 and 1 mg L−1), and 6-(γ,γ-dimethylallylamino) purine (2iP, 10 mg L−1) in MS medium on shoot multiplication. The concentrations of BAP tested (1, 2 and 4 mg L−1) were selected to represent low, intermediate and high practical levels used in micropropagation trials of woody species. This approach enables the identification of an economically viable optimum rather than exhaustive gradient screening. TDZ was included as a strong reference cytokinin known to induce high multiplication, and 2iP was tested to evaluate genotype sensitivity to an alternative aromatic cytokinin. The TDZ and 2iP were filter-sterilized through 25 mm, 0.2 µm Supor® Membrane (Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY, USA) filtration membranes and added aseptically after autoclaving. Each treatment included 25 explants with four replicates. After 30 days, the proliferation rate was calculated as the average number of shoots greater than 10 mm per explant. Callus formation and shoot morphology, including leaf development and the presence of a differentiated apex were also recorded.

2.3. Rooting and Acclimatization

Uniform shoots (15–25 mm) obtained from the multiplication phase, which lasted 4 to 6 subcultures were transferred to half-strength MS medium supplemented with 30 g L−1 sucrose and 7 g L−1 agar to initiate in vitro rooting. Prior to autoclaving at 120 °C and 100 kPa for 15 min, the pH of the medium was adjusted to 5.8 and agar was added. The rooting medium was supplemented with indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), or α-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) at a concentration of 1 mg L−1. These auxins were filter-sterilized through 0.2 µm Supor® membranes and added aseptically to the medium after autoclaving. Rooting cultures were maintained under conditions identical to those used during the initiation and multiplication phases: controlled temperature, light intensity, and photoperiod. Each treatment included 100 replicates, and rooting success was evaluated after 30 days. Rooting efficiency was assessed as the percentage of rooted shoots and the average number of roots per explant. The rooted plantlets were rinsed to remove the agar and then transplanted into pre-soaked peat pellets (Jiffy 7, AS Jiffy Products, Kristiansand, Norway). The pellets were pre-soaked in water for 30 min to ensure adequate moisture prior to planting. The plantlets were misted with sterile water and placed in trays covered with transparent lids to maintain nearly 100% humidity. The trays were kept at 22 °C under a 16 h light/8 h dark cycle with an irradiance of 60 μmol·m−2·s−1. Over 14 days, the lids were gradually opened to allow the plantlets to acclimate to ex vitro conditions.

2.4. Statistical Evaluation of Multiplication and Rooting

The experiment was performed using a completely randomized design. The independent variables were the plant growth regulators used and their concentrations. The dependent variables were the number of shoots (>10 mm) per explant and the number of roots per explant, as well as the proportion of rooted shoots, which were used for multiplication and rooting evaluation, respectively. We examined the data for residual normality and homogeneity of variance using the exact Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests, respectively. Since both datasets were characterized as non-normally distributed, they were processed using non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. Then a Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the treatments. To characterize the variability of the populations within particular treatments, standard deviation (SD) and standard error (SE) were calculated. Outliers observed in the data for both multiplication and rooting were maintained for the statistical analyses. The proportion of rooted explants among the treatments was analyzed using Chi-squared test. All results were considered statistically significant at

p < 0.05. The analysis of outlier occurrence was performed using the interquartile range, as described by in the following equation:

where OL is the outlier, Q1 is the first quartile, IQR is the interquartile range, and Q3 is the third quartile.

All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical computer software (R Development Core Team, 2010, version 2025) [

25].

4. Discussion

Given that woody

Sorbus material is generally prone to contamination and exhibits limited regenerative potential during the early stages of in vitro culture, an overall initiation success rate of 63.5%, can be considered satisfactory. Similar initiation frequencies have been reported for

S. domestica and

S. aucuparia [

7], confirming that the sterilization and establishment protocols are effective for this genus.

The efficiency of growth regulators, particularly of the class of hormones known as auxins, of cytokinins, is a crucial determinant of success in the vitro propagation of

Sorbus species. The type and concentration of the applied cytokinins strongly influence morphogenetic responses, shoot multiplication, and regeneration capacity. Since genotypic sensitivity varies considerably among

Sorbus taxa, it is necessary to evaluate and subsequently optimize cultivation parameters for each genotype [

26,

27].

The present study found that TDZ significantly stimulates shoot multiplication. Multiplication coefficients of 3.39 and 2.88 were obtained at concentrations of 1.0 and 0.5 mg L

−1, respectively. These results align with the general trend reported by Chalupa (2002) [

6], who documented a positive correlation between TDZ concentration and multiplication rate. However, in our experiment, TDZ at a concentration of 1.0 mg L

−1 induced the occurrence of slightly dwarfed leaves and callus formation at the base of the explants (

Figure 6). These responses suggest that increasing the TDZ concentration further could elevate the risk of somaclonal variation or undesirable morphogenetic deviations. While TDZ effectively stimulated shoot formation, these results underscore the importance of balancing morphogenetic efficiency with morphological stability when optimizing levels of the cytokinin.

In contrast, the results showed that 2iP did not stimulate shoot proliferation or cause phytotoxicity (

Figure 7). Due to its limited efficacy and the absence of any visible morphogenetic response, further testing of higher 2iP concentrations was discontinued for economic and practical reasons.

Within the tested concentration range, BAP acted as a more conservative and robust treatment for the production of plant tissue cultures, providing high multiplication together with good shoot quality, stable morphology and an absence of basal callus formation. In cases of individual very high multiplication coefficients (outliners), such as a tenfold increase in a single explant in medium containing 4 mg L−1 BAP, this can likely be attributed to an uneven distribution of endogenous native phytohormones among the initial explants. This uneven distribution is caused by the subdivision and cutting of these explants during subcultivation, and their correlation with the externally added synthetic growth regulator.

While the present study did not compare different genotypes, previous research has shown that genotype strongly influences in vitro multiplication efficiency in

Sorbus species. Reported average multiplication coefficients in

Sorbus species vary widely (approximately 1.1–7.8), reflecting the high level of genetic heterogeneity within the genus [

7,

28]. This variation supports the hypothesis that the optimal type and concentration of the cytokinin must be determined for each genotype individually rather than applying a uniform protocol. In other

Sorbus taxa, combinations of cytokinins, particularly BAP with kinetin, have enhanced shoot induction, achieving multiplication coefficients of up to 7.2 [

29]. Similarly, the type of explant and its physiological state play critical roles in determining the success of shoot proliferation. Arrillaga et al. [

30] reported that

S. domestica apical explants cultured on a medium containing 22.2 µM 6-BAP produced the highest proliferation rate (8.5 shoots per explant).

The contrasting behavior of TDZ and BAP in this study likely reflects their different levels of cytokinin activity and the specific sensitivity of the ‘Discolor’ genotype. TDZ is known as a potent cytokinin in woody plants. In our material, even moderate increase in TDZ concentrations rapidly shifted the response from favorable stimulation of shoot number to the formation of compact shoot clusters and basal callus. TDZ-based protocols that have been successful in other

Sorbus taxa [

6,

27] probably benefited from different genotypes, explant types, levels of internal phytohormones, and medium compositions. These factors allow for a balance between TDZ high stimulatory potential and the risk of morphological disturbance.

Regarding root induction, the literature identifies IBA as the most commonly used and generally effective auxin for rhizogenesis in

Sorbus species [

6,

20,

31,

32]. However, our results showed that IBA and IAA produced similar outcomes: 26% and 31% of the explants formed roots, respectively, whereas NAA produced roots in only 4% of the explants. There were statistically significant differences between IAA and IBA were statistically significant compared to NAA, but not between IAA and IBA. These results suggest that these auxins exhibit similar physiological activity in ‘Discolor’ under the conditions of our experiment. The highest average number of roots (2.13 per explant) was obtained with IAA at 1 mg L

−1, confirming its effectiveness in inducing moderate yet consistent rooting under the tested conditions.

Our results are consistent with those of Dinçer [

29], who observed a positive response to IAA at the same concentration (62% rooting) in

S. aucuparia. Variability in auxin efficacy has been reported across

Sorbus species. For example, Arrillaga [

30] discovered that IAA was the least effective auxin for rooting

S. domestica, with rooting percentage ranging from 6% to 44%. However, higher IAA concentrations (26–52 µM) reduced rooting efficiency and promoted callus formation [

30]. In contrast, IBA or NAA at concentrations of 5.2–26 µM in modified Heller’s medium resulted in 80–87% rooting, demonstrating the strong genotype dependence of auxin responsiveness.

From a methodological perspective, the applied rooting procedure was both efficient and conservative. Although the rooting percentages were moderate, all non-rooted explants remained physiologically healthy after one month of exposure in auxin-containing media and showed no signs of chlorosis or necrosis. These results suggests that the rooting stage can safely be extended or repeated with modified auxin treatments to provide additional opportunities for root induction without compromising explant viability.

In addition to hormonal factors, mineral nutrition significantly impacts morphogenetic outcomes. For example, the addition of non-chelated iron sulfate (FeSO

4) or iron ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Fe-EDTA) has been demonstrated to substantially increase biomass accumulation and organ formation. These supplements increase shoot and root numbers by up to 2.5- and 2-fold, respectively, compared to untreated controls [

33].

In vitro propagation of Sorbus species is successful when a complex interaction is achieved among the balance of cytokinin and auxin, genotype, explant type, and nutrient medium composition. This study confirms that carefully optimizing these parameters for each genotype is crucial for achieving stable morphogenetic outcomes, high multiplication coefficients, and reliable root system formation, while minimizing the risk of somaclonal variation and maintaining economic efficiency in establishing cultures. Our single-factor design focuses on the practical selection of individual hormones and concentrations for an applied propagation protocol aimed at usable and economically feasible methods.

Due to the agricultural and horticultural potential of Sorbus species as alternative fruit crops that are rich in bioactive compounds, the developed micropropagation system is a key step toward the sustainable use and conservation of the valuable genetic resources of this genus. The Research and Breeding Institute of Pomology is currently evaluating the bioactive compound profiles of additional Sorbus species that are of interest to agriculture and the food industry. Based on these evaluations, the RBIP is systematically investigating micropropagation possibilities and assessing genetic stability following micropropagation. The goal is to support breeding programs and genetic resource preservation in these taxa. The institute also aims to diversify and enrich the portfolio of agriculturally cultivated crops, contributing to the development of valuable new fruit crop alternatives. Sorbus species are recognized for their resilience and adaptability to environmental stressors, making them ideal candidates for future sustainable and climate-resilient agricultural and horticultural systems. These characteristics make them robust candidates for future sustainable and climate-resilient agricultural and horticultural systems.