Simulation and Experiment for Retractable Four-Point Flexible Gripper for Grape Picking End-Effector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological and Mechanical Property Analysis of Table Grapes

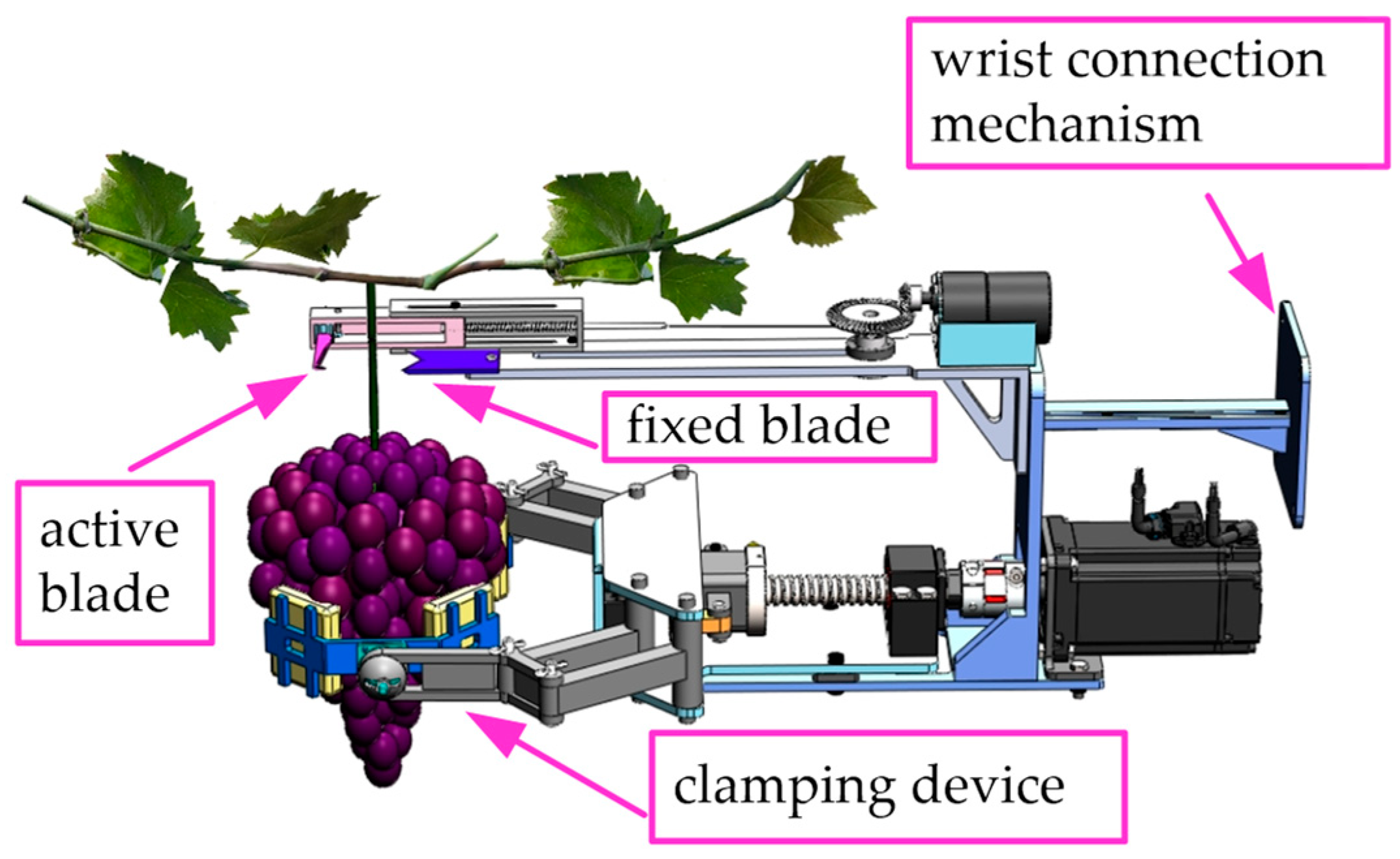

2.2. End-Effector Design Scheme

2.3. Clamping Device Force Closure Analysis

- (1)

- The grasp matrix must be full rank. The rank(G) = 6, ensuring that the force spiral space covers any disturbance direction (satisfying the completeness of the force spiral space).

- (2)

- The existence of internal points: A set of solutions exists that strictly satisfy > 0.

2.4. Contact Force Control System Design

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Finite Element Simulation Analysis of Pedicel Cutting Based on ANSYS/LS-DYNA

3.1.1. Simulation Parameter Setup for Grape Pedicel–Blade System

3.1.2. Post-Processing and Simulation Result Analysis

3.2. The Kinematic Simulation of the Clamping Device Based on ADAMS

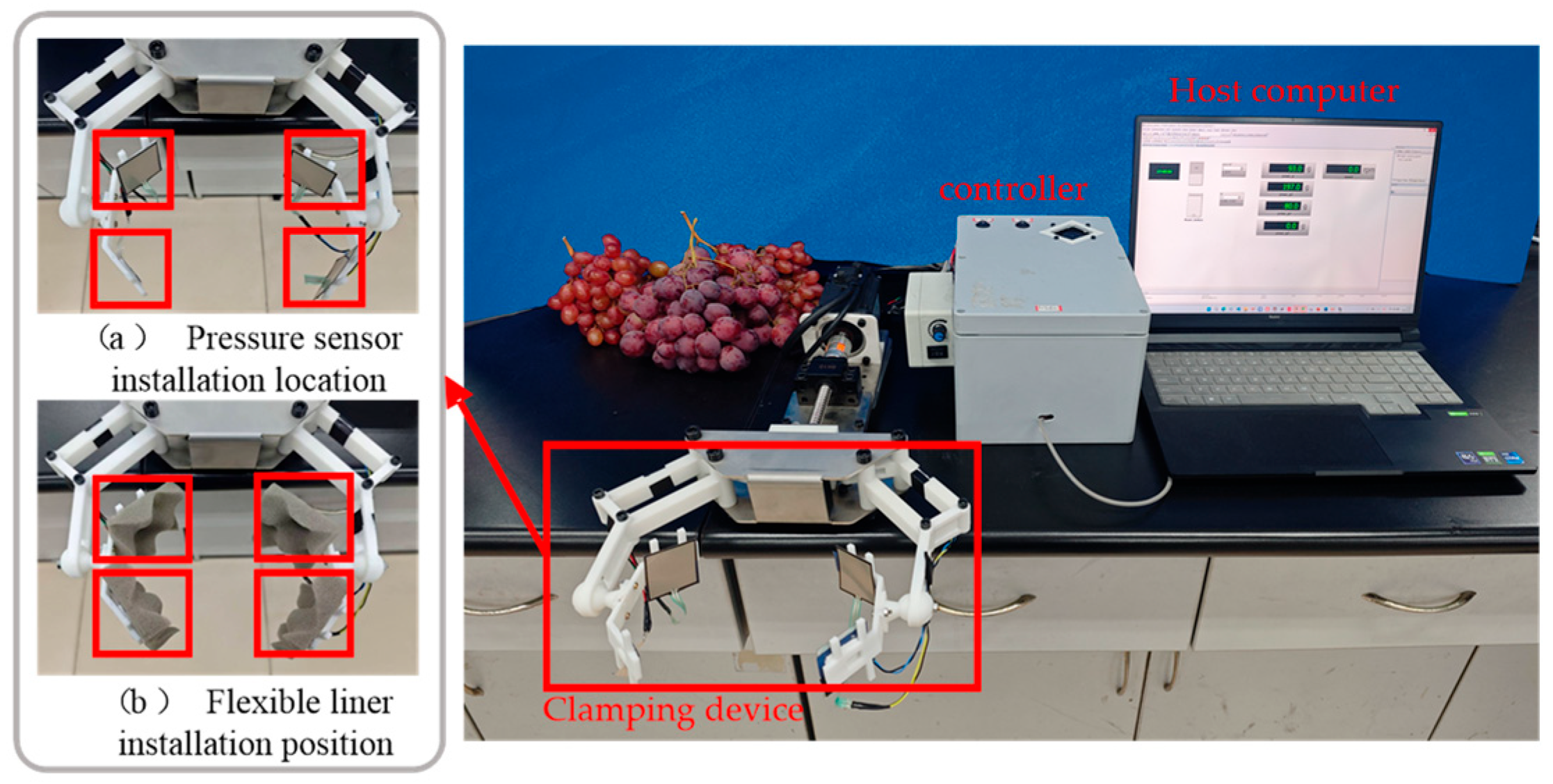

3.2.1. Contact Force Test Platform

3.2.2. Motor Three-Loop Control System Design

- (1)

- Torque Loop: The three-phase stator currents are sampled via shunt resistors and transformed into d- and q-axis currents in the stationary reference frame. Under the = 0 control strategy, the q-axis current reference is generated by the speed loop controller. It is then compared with the measured and values, and the error signals are processed by the torque loop controller to generate compensated voltage signals. These signals are modulated via SVPWM to drive the three-phase inverter, thereby controlling the motor and forming the torque closed-loop control system.

- (2)

- Speed Loop: An incremental encoder measures the motor rotor speed in real time. The speed error is calculated by comparing this measured value with the output of the speed loop controller. This error is processed by the speed loop controller, whose output serves as the current reference for the torque loop, adjusting the motor torque to ensure smooth system operation and forming a nested dual closed-loop control system with the torque loop.

- (3)

- Position Loop: The motor’s current position is obtained by integrating the speed information measured by the encoder. The position error is calculated by comparing this value with the position reference. This error is processed by the position loop controller, which outputs the desired speed reference for the speed loop. This ensures the precise tracking of position commands and accurate control of the end-effector’s motion, constituting the overall position closed-loop control system.

3.3. Prototype Fabrication and Field Testing

3.4. Discussion

- (1)

- In the ANSYS/LS-DYNA simulation of the pedicel cutting process, the pedicel is completely severed at 0.7951 s, with a peak cutting stress of 1.515 MPa, exceeding the measured pedicel shear strength of 1.349~1.426 MPa. This confirms the rationality of the blade structure design and its effective cutting capability. In the ADAMS contact force simulation, the peak contact force between the clamping fingers and the grape is 11 N, which is close to the preliminarily determined clamping threshold of 11 N for stable, non-damaging gripping. Moreover, it remains significantly below the grape’s critical compressive rupture force (25.79~34.54 N), confirming that the clamping process ensures cluster stability without inducing mechanical damage.

- (2)

- The contact force bench test further verifies that 11 N is an appropriate clamping threshold, and the Root Mean Square (RMS) method is selected as the optimal algorithm for processing the four-channel sensor data. For motor control, a position–speed–torque three-loop control strategy is implemented to achieve precise control of the clamping motor. Both the simulation and the empirical results show that when the rotor target position is set to 1 rad, the motor completes a rapid response within 0.2~0.25 s, with no noticeable overshoot and minimal steady-state errors. The control response error remains within ±0.2 s, indicating excellent dynamic responsiveness and robustness—meeting the real-time and stability requirements of the clamping control system.

- (3)

- The field tests of our prototype yielded key performance metrics, including a harvesting success rate of 96.7%, a cycle time of 13.7 s, a bruise rate of 2.8%, and a berry drop rate of 3.2%. Compared to existing studies, our system demonstrates a competitive performance, particularly in its balanced efficiency and low damage.

- (4)

- The harvesting tests performed in this study involved a total of 60 samples across three grape varieties, with 20 samples per variety. The relatively small sample size may introduce some uncertainty in the test results. Our research team plans to expand the sample database and conduct more repeated trials in the next harvesting season to improve the certainty of the test outcomes.

- (5)

- However, numerous issues warrant further investigation. Significant room for improvement remains in the optimization of the end-effector, as instances of the incomplete severing of grape pedicels during field trials persist, leading to system halts that require manual intervention. Integrating technologies such as environmental perception systems and autonomous navigation could substantially enhance the harvesting performance and intelligence level of the robotic harvester.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- To address issues such as high clamping damage rates in automated grape harvesting, diverse grape varieties and shapes, and dispersed pedicel regions, a retractable four-point flexible clamping end-effector was proposed. The theoretical analysis confirmed that the clamping mechanism met force-closure requirements, and an optimal contact force threshold of 11 N was determined to ensure stable gripping without damaging the grapes.

- (2)

- Simulations conducted using ANSYS/LS-DYNA and ADAMS confirmed the cutting device’s effective capability to sever the pedicel and verified the rationality of the contact force applied by the clamping mechanism. The contact force bench testing further determines that a maximum contact force threshold of 11 N enables stable clamping without damaging the grape berries. A prototype was fabricated and tested in vineyard field trials, which demonstrated a harvesting success rate of 96.7%, with drop and rupture rates controlled within 3.2% and 2.8%, respectively. The average time per harvesting cycle was 13.7 s. The system exhibited strong adaptability and stability across different grape varieties.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pan, B.W.; Lin, M.L.; Ju, Y.L.; Su, B.; Sun, L.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Jiang, J.; et al. Research on leaf identification of table grape varieties based on deep learning. J. Fruit Sci. 2025, 42, 1883–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ru, M.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Zhao, C. Fruit flexible collecting trajectory planning based on manual skill imitation for grape harvesting robot. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Wu, Z.; Bai, R.; Meng, G. Ergonomic and efficiency analysis of conventional apple harvest process. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2019, 12, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q. Review of smart robots for fruit and vegetable picking in agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2022, 15, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Cai, L.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xie, B. Realtime Picking Point Decision Algorithm of Trellis Grape for High-Speed Robotic Cut-and-Catch Harvesting. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.L.; Gong, L.; Yuan, J.; Li, Y.M. Research Status and Development Trends of Key Technologies in Agricultural Robots. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yan, D.; Cai, X.; Chen, Y.; Luo, L.; Pan, Y.; Zou, X. Multidirectional Dynamic Response and Swing Shedding of Grapes: An Experimental and Simulation Investigation under Vibration Excitation. Agronomy 2023, 13, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yin, C.K.; Guo, Z.L.; Wang, J.P.; Zhou, H.P.; Jiang, X.S. Research Status and Development Trends of Key Technologies in Apple Harvesting Robots. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2023, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.Y.; Yan, J.W.; Zhang, F.G.; Gou, T.; Xu, Y. Research Progress on Vegetable Harvesting Robots and Their Key Technologies. J. Chin. Agric. Mac. 2023, 44, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liang, J.; Zhao, S.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Jin, Y. Design of a Virtual Multi-Interaction Operation System for Hand–Eye Coordination of Grape Harvesting Robots. Agronomy 2023, 13, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Peng, Y.; Shan, H. Development of a dual-arm rapid grape-harvesting robot for horizontal trellis cultivation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 881904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Park, Y.; Son, H.I. A suction cup-based soft robotic gripper for cucumber harvesting: Design and validation. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 238, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, F.; Castellini, F.; Muradore, R. A soft, sensorized gripper for delicate harvesting of small fruits. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 213, 108202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Yang, H.; Yang, H. Application of Soft Grippers in the Field of Agricultural Harvesting: A Review. Machines 2025, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lv, M.; Xu, Q.; Xu, R. Design and Analysis of a Robotic Gripper Mechanism for Fruit Picking. Actuators 2024, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Peng, C.; Grimstad, L.; From, P.J.; Isler, V. Development and field evaluation of a strawberry harvesting robot with a cable-driven gripper. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 157, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrochidou, E.; Tziridis, K.; Nikolaou, A.; Kalampokas, T.; Papakostas, G.A.; Pachidis, T.P.; Mamalis, S.; Koundouras, S.; Kaburlasos, V.G. An Autonomous Grape-Harvester Robot: Integrated System Architecture. Electronics 2021, 10, 2079–9292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrochidou, E.; Bazinas, C.; Manios, M.; Papakostas, G.A.; Pachidis, T.P.; Kaburlasos, V.G. Machine Vision for Ripeness Estimation in Viticulture Automation. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Yin, J.; He, K.; Yu, C. Grape Picking 4-DOF Robot Arm Design and Virtual Prototype Simulation. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2019, 41, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.N.; Yin, Z.J.; Hu, H.W.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, Z. Design of a Bio-inspired Suction Cup with High Surface Adaptability. J. Jilin Univ. Eng. Technol. Ed. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.H.; Ji, C.H.; Dou, M.Y.; Wang, X. Bionic Design and Research of a Flexible Soft Gripper. China Mech. Eng. 2023, 34, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, E.; Fernández, R.; Sepúlveda, D.; Armada, M.; Gonzalez-De-Santos, P. Soft Grippers for Automatic Crop Harvesting: A Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Lv, J.; Dong, C.; Li, J.; Luo, Y.; Wu, W.; Abdeen, M.A. Classification, Advanced Technologies, and Typical Applications of End-Effector for Fruit and Vegetable Picking Robots. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Tian, F.; Dong, X.; Li, F. The Structure and Control Analysis of AMR Automatic Harvesting Robot. In Recent Developments in Mechatronics and Intelligent Robotics (ICMIR 2017); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, Z.; Hao, W.; Wang, X.; Ding, X.; Cui, Y. Kiwifruit harvesting impedance control and optimization. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 251, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H. Design and Experiment of Robotic Hand-Arm Cooperative Damage-Freeharvesting System for Trellis Grapes. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhengjiang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Design of the Structure and Control System of Grapeharvesting Robot. Master’s Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cong, M.; Liu, D.; Du, Y.; Xu, X. Stable grasp planning based on minimum force for dexterous hands. Intel. Serv. Robot. 2020, 13, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sui, S.; Du, W.; Li, X.; Liu, P. Picking point localization method of table grape picking robot based on you only look once version. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 146, 110266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y. Integrated Grape Harvesting and Transportation Automatic Harvesting System. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang A&F University, Hangzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Grape Cluster Length/mm | Grape Cluster Equatorial Diameter/mm | Mass/g | Pedicel Diameter/mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kyoho Grape | 140~245 | 100~200 | 300~1600 | 5.8~10 |

| Rose Grape | 130~200 | 90~190 | 320~1300 | 4.6~9.5 |

| Red Globe | 180~290 | 100~180 | 400~2000 | 5.3~10.8 |

| Property | Kyoho Grape | Rose Grape | Red Globe Grape |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral Compression Critical Rupture Force/N | 31.59 | 27.96 | 34.54 |

| Longitudinal Compression Critical Rupture Force/N | 27.86 | 25.79 | 29.51 |

| Pedicel Shear Force/N | 88.75 | 85.37 | 92.36 |

| Shear Strength/MPa | 1.387 | 1.349 | 1.426 |

| Material | Density/g·mm−3 | Ea/MPa | Eb/MPa | Ec/MPa | vab | vac | vbc | Gab/MPa | Gac/MPa | Gbc/MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedicel | 4.5 × 10−4 | 300 | 450 | 1.2 × 10−4 | 0.4 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 50 | 300 | 200 |

| Material | Density (g/cm3) | Modulus of Elasticity (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| aluminum alloy | 2.7 | 70 | 0.33 |

| structural steel | 7.8 | 200 | 0.28 |

| PLA | 1.25 | 3.5 | 0.35 |

| grape cluster | 0.9 | 0.01 | 0.45 |

| Serial Number | Constraint Type | Constrained Components |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fixed Pair | Support Plate—Ground |

| 2 | Fixed Pair | Base Plate—Ball Screw |

| 3 | Fixed Pair | Finger—Link 3 |

| 4 | Fixed Pair | Finger—Pressure Sensor |

| 5 | Fixed Pair | Pressure Sensor—Rubber |

| 6 | Revolute Pair | Link 1—Support Plate |

| 7 | Revolute Pair | Link 2—Support Plate |

| 8 | Revolute Pair | Link 1—Link 3 |

| 9 | Revolute Pair | Link 2—Link 3 |

| 10 | Revolute Pair | Link 1—Link 4 |

| 11 | Revolute Pair | Link 4—Ball Nut |

| 12 | Prismatic Pair | Lead Screw—Ball Nut |

| 13 | Contact Constraint | Rubber—Grape Cluster |

| Calculation Method | Mean/N | Standard Deviation/N | Error Ratio (Standard Deviation/Mean) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9.994 | 0.256 | 0.0256 | |

| 9.753 | 0.255 | 0.0261 | |

| 10.001 | 0.254 | 0.0255 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Torque Loop Kp | 0.02 |

| Torque Loop Ki | 0.5 |

| Speed Loop Kp | 2 |

| Speed Loop Ki | 5 |

| Position Loop Ki | 80 |

| The Variety of Grapes | Test Count | Stable Grasp Count | Successful Cutting Count | Average Drop Rate/% | Average Rupture Rate/% | Average Harvest Time/s | Harvesting Success Rate/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kyoho | 20 | 20 | 19 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 13.2 | 95 |

| Rose | 20 | 20 | 19 | 3.5 | 3 | 14.9 | 95 |

| Red Globe | 20 | 20 | 20 | 3 | 2.5 | 13 | 100 |

| total/60 | total/60 | total/58 | average/3.2 | average/2.8 | average/13.7 | average/96.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, C. Simulation and Experiment for Retractable Four-Point Flexible Gripper for Grape Picking End-Effector. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2813. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122813

Hu X, Zhang Q, Hu C. Simulation and Experiment for Retractable Four-Point Flexible Gripper for Grape Picking End-Effector. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2813. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122813

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Xiaoqi, Qian Zhang, and Caiqi Hu. 2025. "Simulation and Experiment for Retractable Four-Point Flexible Gripper for Grape Picking End-Effector" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2813. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122813

APA StyleHu, X., Zhang, Q., & Hu, C. (2025). Simulation and Experiment for Retractable Four-Point Flexible Gripper for Grape Picking End-Effector. Agronomy, 15(12), 2813. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122813