Intra-Urban CO2 Spatiotemporal Patterns and Driving Factors Using Multi-Source Data and AI Methods: A Case Study of Shanghai, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Preparation

2.3. Model Setting

2.3.1. Spatial Distribution Analysis of CO2 Concentration in Shanghai

2.3.2. Analyzing Urban–Rural and Inter-District CO2 Concentration Differences in Shanghai

2.3.3. Analyzing the Vertical and Temporal Distribution of CO2 Concentration in Shanghai

2.3.4. Diagnostic Screening of Influencing Variables on CO2 Concentration

2.3.5. Assessing the Importance of CO2 Influencing Factors Using Random Forest

2.3.6. Explaining the Contributions of Influencing Factors with SHAP

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distributions of CO2 Concentration in Shanghai

3.2. CO2 Concentration Urban–Rural and Inter-District Differences in Shanghai

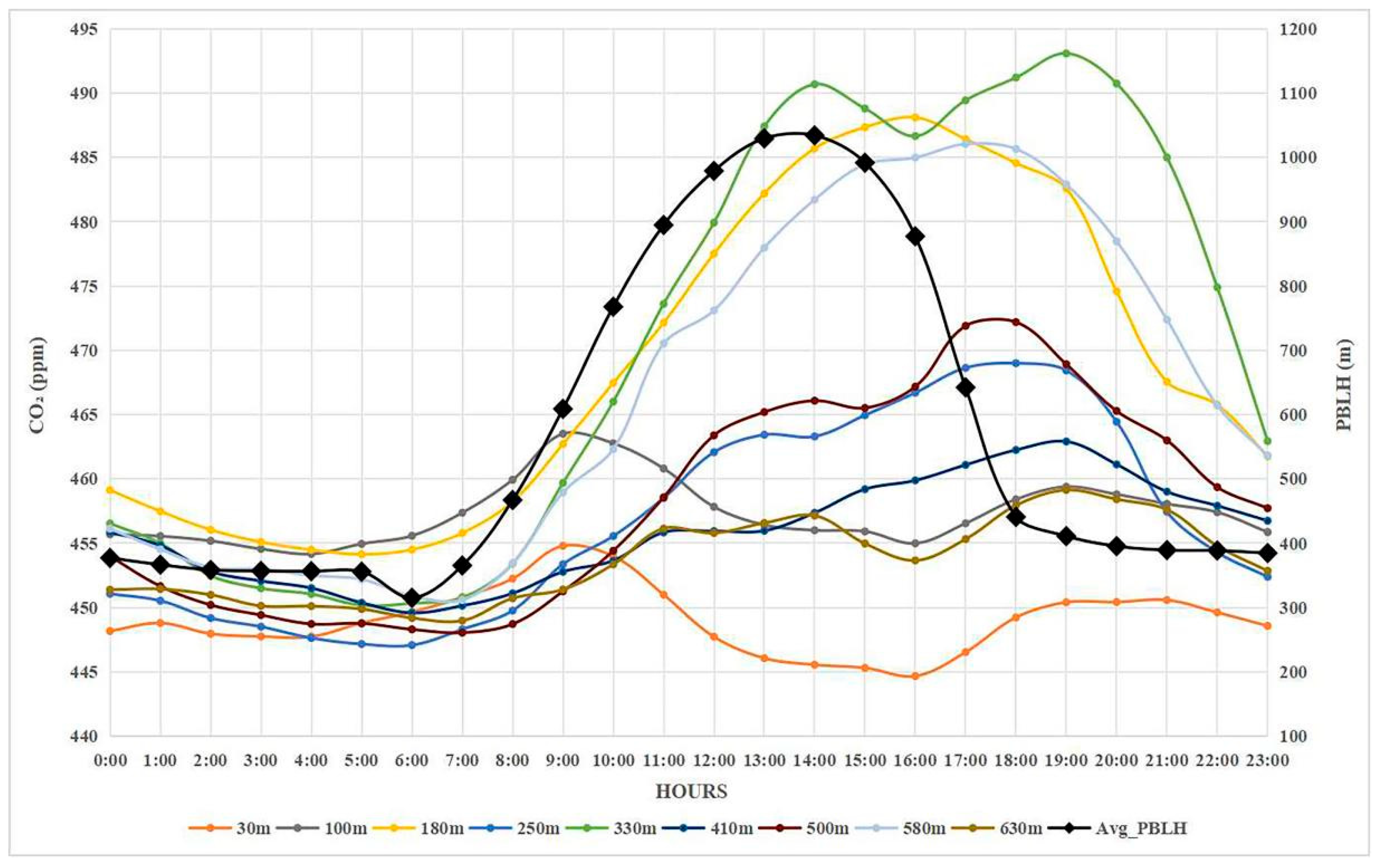

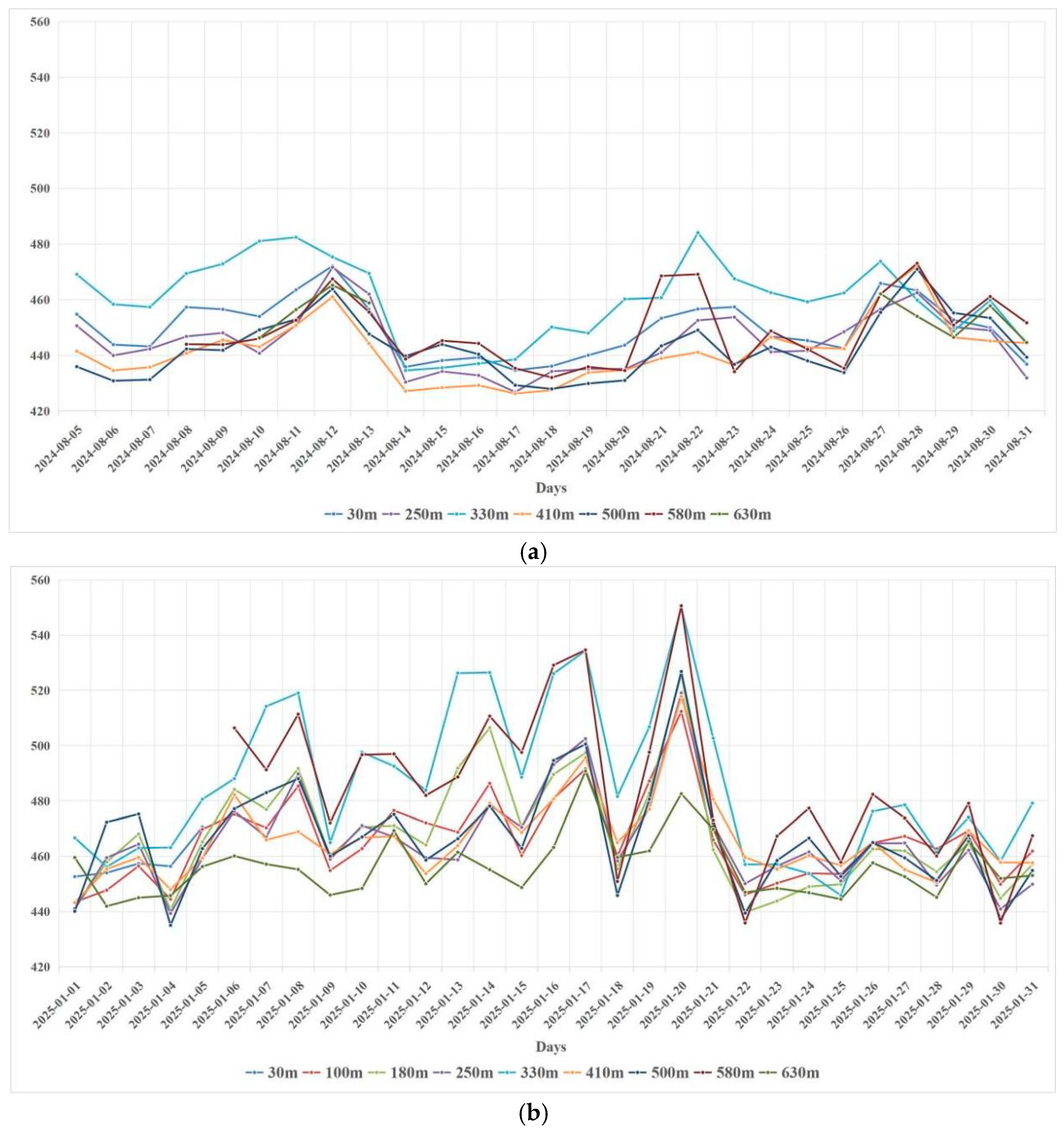

3.3. Vertical and Temporal Distribution Patterns of CO2 Concentration in Shanghai

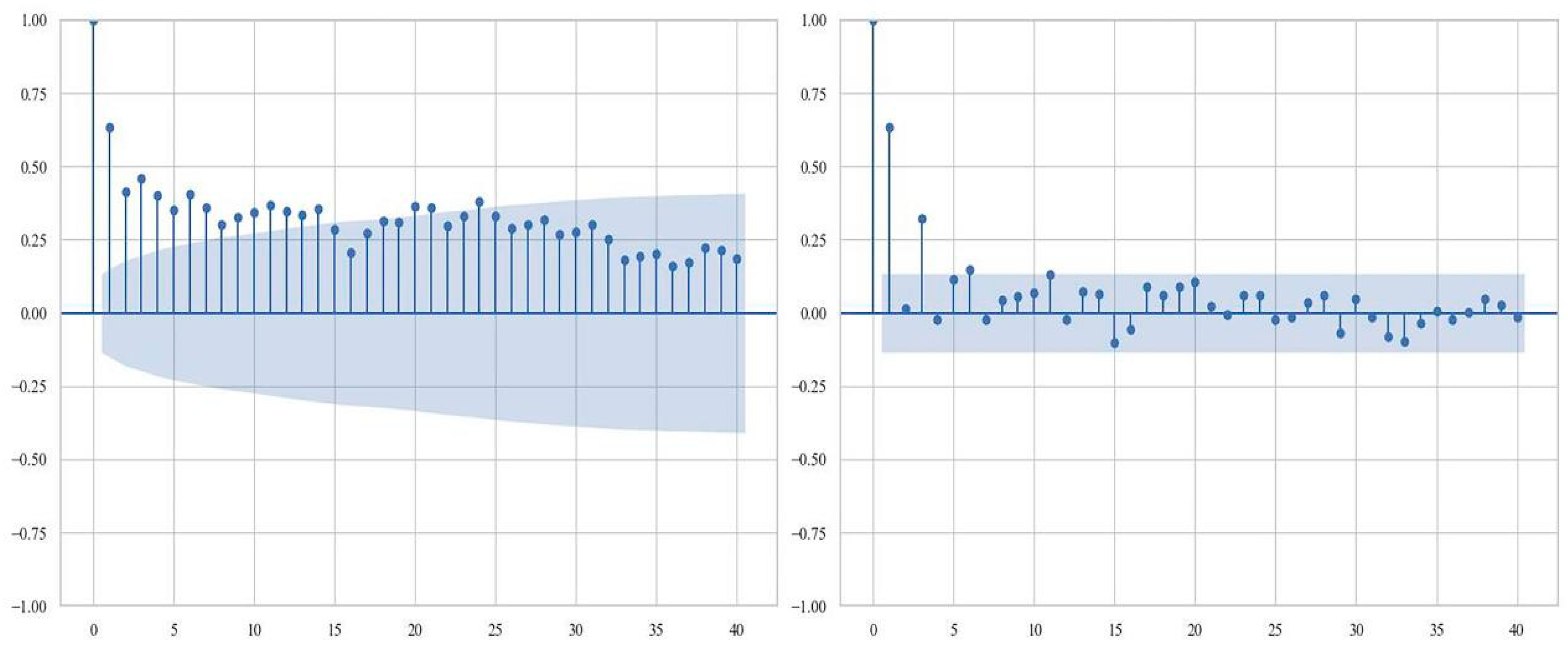

3.4. OLS Model Results for CO2 Concentration and Urban Factors

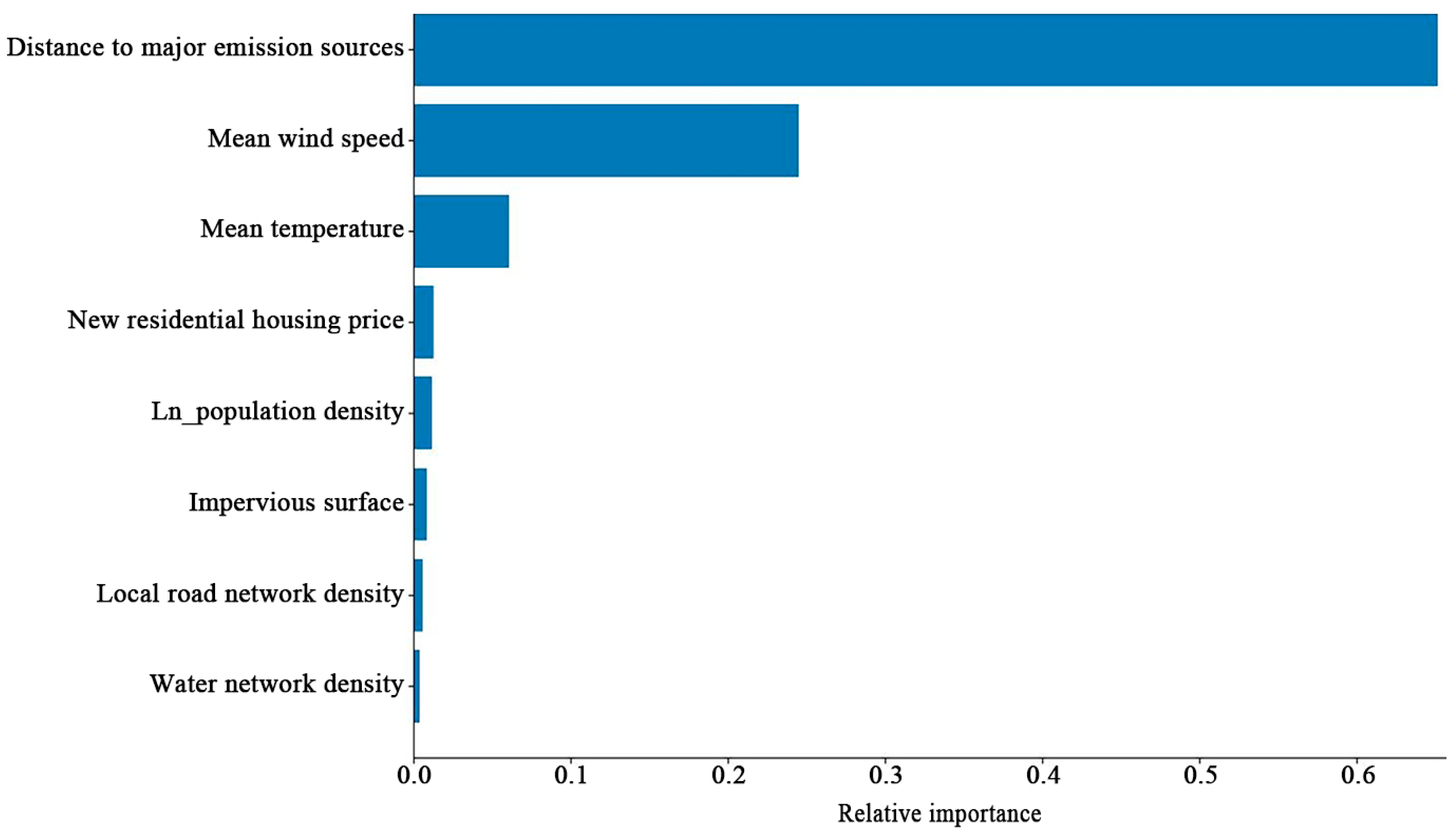

3.5. Random Forest Results for CO2 Driver Importance

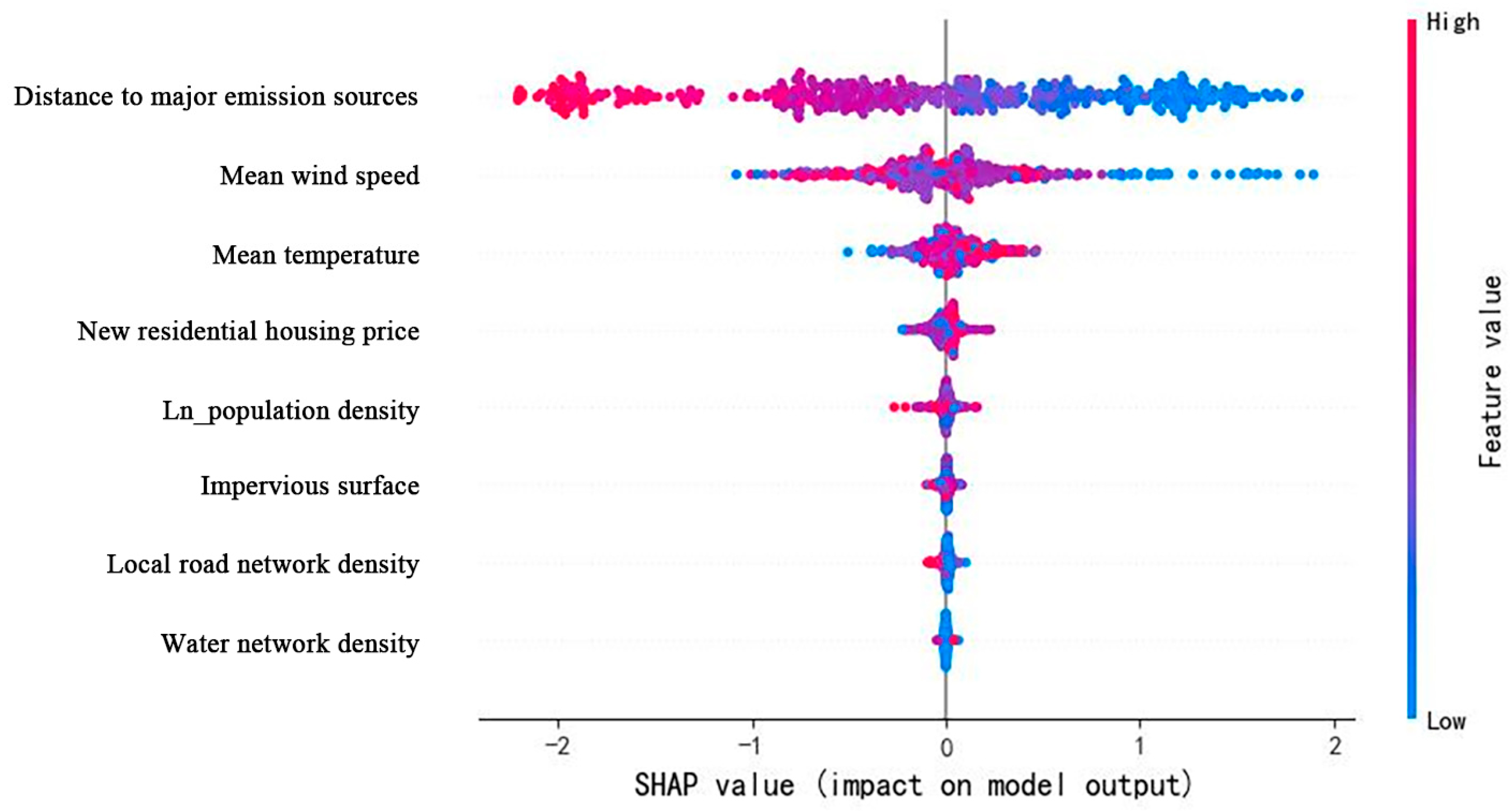

3.6. SHAP Results for CO2 Driver Mechanisms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Y.; Lee, X.; Liu, S.; Hu, N.; Wei, X.; Hu, C.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y. Spatiotemporal Variability of the Near-Surface CO2 Concentration across an Industrial-Urban-Rural Transect, Nanjing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Fifteenth Session; United Nations: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010.

- Zhang, J.J.Y.; Sun, L.; Rainham, D.; Dummer, T.J.B.; Wheeler, A.J.; Anastasopolos, A.; Gibson, M.; Johnson, M. Predicting Intraurban Airborne PM1.0-Trace Elements in a Port City: Land Use Regression by Ordinary Least Squares and a Machine Learning Algorithm. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Meng, Z.; She, Q.; Zhu, X.; Wei, N.; Peng, X.; Xu, Q. Spatial Variability and Determinants of Atmospheric Methane Concentrations in the Metropolitan City of Shanghai, China. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 214, 116834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, S.; Cabassi, J.; Tassi, F.; Maioli, G.; Randazzo, A.; Capecchiacci, F.; Vaselli, O. Near-Surface Atmospheric Concentrations of Greenhouse Gases (CO2 and CH4) in Florence Urban Area: Inferring Emitting Sources through Carbon Isotopic Analysis. Urban Clim. 2021, 39, 100968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazzeri, G.; Graven, H.; Xu, X.; Saboya, E.; Blyth, L.; Manning, A.J.; Chawner, H.; Wu, D.; Hammer, S. Radiocarbon Measurements Reveal Underestimated Fossil CH4 and CO2 Emissions in London. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL103834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.B.; Lehman, S.J.; Verhulst, K.R.; Miller, C.E.; Duren, R.M.; Yadav, V.; Newman, S.; Sloop, C.D. Large and Seasonally Varying Biospheric CO2 Fluxes in the Los Angeles Megacity Revealed by Atmospheric Radiocarbon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26681–26687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sweeney, J. Modelling the Impact of Urban Form on Household Energy Demand and Related CO2 Emissions in the Greater Dublin Region. Energy Policy 2012, 46, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focas, C. Travel Behaviour and CO2 Emissions in Urban and Exurban London and New York. Transp. Policy 2016, 46, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodzicki, T.; Jankiewicz, M. The Impact of Renewable Energy and Urbanization on CO2 Emissions in Europe—Spatio-Temporal Approach. Environ. Dev. 2022, 44, 100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callewaert, S.; Brioude, J.; Langerock, B.; Duflot, V.; Fonteyn, D.; Müller, J.-F.; Metzger, J.-M.; Hermans, C.; Kumps, N.; Ramonet, M.; et al. Analysis of CO2, CH4, and CO Surface and Column Concentrations Observed at Réunion Island by Assessing WRF-Chem Simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 7763–7792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivas, G.; Mahesh, P.; Mahalakshmi, D.V.; Kanchana, A.L.; Chandra, N.; Patra, P.K.; Raja, P.; Sesha Sai, M.V.R.; Sripada, S.; Rao, P.V.N.; et al. Seasonal and Annual Variations of CO2 and CH4 at Shadnagar, a Semi-Urban Site. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 819, 153114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiya, S.; Gansukh, T.-E.; Batbold, B. Evaluating Seasonal Variations of CO2 Fluxes from Peatland Areas in the Mongolian Permafrost Region. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology (EST 2023), Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 10–11 August 2023; Batdelger, O., Damdinsuren, A., Avirmed, D., Erdenee, B., Eds.; Advances in Engineering Research. Atlantis Press International BV: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 224, pp. 7–16, ISBN 978-94-6463-277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Du, R.; Qi, B.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, G.; Chen, B.; Li, J. Variation of Carbon Dioxide Mole Fraction at a Typical Urban Area in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Atmos. Res. 2022, 265, 105884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graven, H.; Fischer, M.L.; Lueker, T.; Jeong, S.; Guilderson, T.P.; Keeling, R.F.; Bambha, R.; Brophy, K.; Callahan, W.; Cui, X.; et al. Assessing Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions in California Using Atmospheric Observations and Models. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 065007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soegaard, H.; Møller-Jensen, L. Towards a Spatial CO2 Budget of a Metropolitan Region Based on Textural Image Classification and Flux Measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 87, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makido, Y.; Dhakal, S.; Yamagata, Y. Relationship between Urban Form and CO2 Emissions: Evidence from Fifty Japanese Cities. Urban Clim. 2012, 2, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, S.; Kuttler, W. Near Surface Carbon Dioxide within the Urban Area of Essen, Germany. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2010, 35, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Qi, B.; Ma, Q.; Zang, K.; Lin, Y.; Liu, S.; Pan, F.; Li, S.; Guo, P.; et al. Atmospheric CO2 in the Megacity Hangzhou, China: Urban-Suburban Differences, Sources and Impact Factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Zhu, X.; Wei, N.; Zhu, X.; She, Q.; Jia, W.; Liu, M.; Xiang, W. Spatial Variability of Daytime CO2 Concentration with Landscape Structure across Urbanization Gradients, Shanghai, China. Clim. Res. 2016, 69, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Han, W.; Cai, Y.; Wen, Q.; Kong, K.; Guan, W. Near-Surface CO2 Concentration Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors in Korla. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 24, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, T.; Yao, B.; Han, P.; Ji, D.; Zhou, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, P. Spatial and Temporal Variations of CO2 Mole Fractions Observed at Beijing, Xianghe and Xinglong in North China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 11741–11757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.E.; Lin, J.C.; Bowling, D.R.; Pataki, D.E.; Strong, C.; Schauer, A.J.; Bares, R.; Bush, S.E.; Stephens, B.B.; Mendoza, D.; et al. Long-Term Urban Carbon Dioxide Observations Reveal Spatial and Temporal Dynamics Related to Urban Characteristics and Growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 2912–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Shi, Y.; Zang, S.; Sun, L. Spatial and Temporal Variations of Atmospheric CO2 Concentration in China and Its Influencing Factors. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Ye, T.; Chen, X.; Dong, H.; Wang, W.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y. Full-Coverage Mapping High-Resolution Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations in China from 2015 to 2020: Spatiotemporal Variations and Coupled Trends with Particulate Pollution. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428, 139290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, W.; Niu, Z.; Xiong, X.; Wu, S.; Cheng, P.; Hou, Y.; Lu, X.; Du, H. Spatio-Temporal Variability of Atmospheric CO2 and Its Main Causes: A Case Study in Xi’an City, China. Atmos. Res. 2021, 249, 105346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Palmer, P.I.; Yang, Y.; Yantosca, R.M.; Kawa, S.R.; Paris, J.-D.; Matsueda, H.; Machida, T. Evaluating a 3-D Transport Model of Atmospheric CO2 Using Ground-Based, Aircraft, and Space-Borne Data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 2789–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett-Heaps, C.A.; Rayner, P.J.; Law, R.M.; Ciais, P.; Patra, P.K.; Bousquet, P.; Peylin, P.; Maksyutov, S.; Marshall, J.; Rödenbeck, C.; et al. Atmospheric CO2 Inversion Validation Using Vertical Profile Measurements: Analysis of Four Independent Inversion Models. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, D12305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, J.; Mu, C.; Xing, Z.; Du, K. Vertical Distribution of CO2 in the Atmospheric Boundary Layer: Characteristics and Impact of Meteorological Variables. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 91, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siabi, Z.; Falahatkar, S.; Alavi, S.J. Spatial Distribution of XCO2 Using OCO-2 Data in Growing Seasons. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 244, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhou, Y.; Gu, H.; Tian, Z. Seasonal Dynamics and Impact Factors of Urban Forest CO2 Concentration in Harbin, China. J. For. Res. 2017, 28, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.; Bu, L.; Wang, Q.; Shahzaman, M.; Bilal, M.; Aslam, R.W.; Dong, C. Spatiotemporal Investigation of Near-Surface CO2 and Its Affecting Factors Over Asia. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4108316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, P. The Climate Legacy of Svante Arrhenius. Icon 2020, 25, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling, C.D. The Concentration and Isotopic Abundances of Carbon Dioxide in the Atmosphere. Tellus 1960, 12, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNutt, M. Climate Warning, 50 Years Later. Science 2015, 350, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1992.

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). World Climate Conference-1 (WCC-1). In Proceedings of the World Climate Conference: A Conference of Experts on Climate and Mankind, Geneva, Switzerland, 12–23 February 1979; World Meteorological Organization, Ed.; Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, L.; Ogink, N.; Edouard, N.; Van Dooren, H.; Tinôco, I.; Mosquera, J. NDIR Gas Sensor for Spatial Monitoring of Carbon Dioxide Concentrations in Naturally Ventilated Livestock Buildings. Sensors 2015, 15, 11239–11257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.R.; Zeng, N.; Karion, A.; Dickerson, R.R.; Ren, X.; Turpie, B.N.; Weber, K.J. Evaluation and Environmental Correction of Ambient CO2 Measurements from a Low-Cost NDIR Sensor. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 2383–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, J.A.; Villen-Guzman, M.; Rodriguez-Maroto, J.M.; Paz-Garcia, J.M. Comparing CO2 Storage and Utilization: Enhancing Sustainability through Renewable Energy Integration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adames, Á.F.; Kim, D.; Sobel, A.H.; Del Genio, A.; Wu, J. Changes in the Structure and Propagation of the M JO with Increasing CO2. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2017, 9, 1251–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Paris Agreement Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC): Bonn, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, P.B.; Edwards, N.R.; Ridgwell, A.; Wilkinson, R.D.; Fraedrich, K.; Lunkeit, F.; Pollitt, H.; Mercure, J.-F.; Salas, P.; Lam, A.; et al. Climate–Carbon Cycle Uncertainties and the Paris Agreement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Xu, Y.; Ma, J. The Potential of CO2 Satellite Monitoring for Climate Governance: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 111423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Marinello, F. Spatial Variation of NO2 and Its Impact Factors in China: An Application of Sentinel-5P Products. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louet, J.; Bruzzi, S. ENVISAT Mission and System. In Proceedings of the IEEE 1999 International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. IGARSS’99 (Cat. No.99CH36293), Hamburg, Germany, 28 June–2 July 1999; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 3, pp. 1680–1682. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, C.L. The Earth-Observing Aqua Satellite Mission: 20 Years and Counting. Earth Space Sci. 2022, 9, e2022EA002481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeberl, M.R.; Douglass, A.R.; Hilsenrath, E.; Luce, M.; Bamett, J.; Beer, R.; Waters, J.; Gille, J.; Levelt, P.F.; DeCola, P. The EOS Aura Mission. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2001. Scanning the Present and Resolving the Future. Proceedings. IEEE 2001 International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (Cat. No.01CH37217), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 9–13 June 2001; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2001; Volume 1, pp. 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- August, T.; Klaes, D.; Schlüssel, P.; Hultberg, T.; Crapeau, M.; Arriaga, A.; O’Carroll, A.; Coppens, D.; Munro, R.; Calbet, X. IASI on Metop-A: Operational Level 2 Retrievals after Five Years in Orbit. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2012, 113, 1340–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaes, K.D.; Montagner, F.; Larigauderie, C. Metop-B, the Second Satellite of the EUMETSAT Polar System, in Orbit; Butler, J.J., Xiong, X., Gu, X., Eds.; SPIE: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; p. 886613. [Google Scholar]

- Righetti, P.L.; De Juana Gamo, J.M.; Sancho, F. Metop-C Deployment and Start of Three-Satellite Operations. Aeronaut. J. 2020, 124, 902–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuya, M.; Nakajima, M.; Hamazaki, T. Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite (GOSAT) Program Overview and Its Development Status. Trans. JSASS Space Tech. Japan 2009, 7, To_4_5–To_4_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisp, D.; Pollock, H.R.; Rosenberg, R.; Chapsky, L.; Lee, R.A.M.; Oyafuso, F.A.; Frankenberg, C.; O’Dell, C.W.; Bruegge, C.J.; Doran, G.B.; et al. The On-Orbit Performance of the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) Instrument and Its Radiometrically Calibrated Products. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yao, L.; Chen, X.; Cai, Z.; Yang, D.; Yin, Z.; Gu, S.; Tian, L.; Lu, N.; et al. The TanSat Mission: Preliminary Global Observations. Sci. Bull. 2018, 63, 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldering, A.; O’Dell, C.W.; Wennberg, P.O.; Crisp, D.; Gunson, M.R.; Viatte, C.; Avis, C.; Braverman, A.; Castano, R.; Chang, A.; et al. The Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2: First 18 Months of Science Data Products. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwandner, F.M.; Gunson, M.R.; Miller, C.E.; Carn, S.A.; Eldering, A.; Krings, T.; Verhulst, K.R.; Schimel, D.S.; Nguyen, H.M.; Crisp, D.; et al. Spaceborne Detection of Localized Carbon Dioxide Sources. Science 2017, 358, eaam5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kort, E.A.; Frankenberg, C.; Miller, C.E.; Oda, T. Space-based Observations of Megacity Carbon Dioxide. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, 2012GL052738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Lin, J.C.; Fasoli, B.; Oda, T.; Ye, X.; Lauvaux, T.; Yang, E.G.; Kort, E.A. A Lagrangian Approach towards Extracting Signals of Urban CO2 Emissions from Satellite Observations of Atmospheric Column CO2 (XCO2): X-Stochastic Time-Inverted Lagrangian Transport Model (“X-STILT V1”). Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 4843–4871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Lauvaux, T.; Kort, E.A.; Oda, T.; Feng, S.; Lin, J.C.; Yang, E.G.; Wu, D. Constraining Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions From Urban Area Using OCO-2 Observations of Total Column CO2. JGR Atmos. 2020, 125, e2019JD030528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldering, A.; Taylor, T.E.; O’Dell, C.W.; Pavlick, R. The OCO-3 Mission: Measurement Objectives and Expected Performance Based on 1 Year of Simulated Data. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 12, 2341–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, M.; Eldering, A.; Roten, D.D.; Lin, J.C.; Feng, S.; Lei, R.; Lauvaux, T.; Oda, T.; Roehl, C.M.; Blavier, J.-F.; et al. Urban-Focused Satellite CO2 Observations from the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-3: A First Look at the Los Angeles Megacity. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutayeb, A.; Lahsen-cherif, I.; Khadimi, A.E. A Comprehensive GeoAI Review: Progress, Challenges and Outlooks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.11643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Arundel, S.; Gao, S.; Goodchild, M.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zipf, A. GeoAI for Science and the Science of GeoAI. J. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Biljecki, F. A Review of Spatially-Explicit GeoAI Applications in Urban Geography. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 112, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Population. In China Statistical Yearbook 2024; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2024; Tables 2–5; ISBN 978-7-5230-0486-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; et al. ERA5 Hourly Data on Single Levels from 1940 to Present 2023; Climate Data Store (CDS). Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=documentation (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Science Computing Facility, J.P.L. OCO-2 Level 2 Geolocated XCO2 Retrievals Results, Physical Model, Retrospective Processing V11r 2017. Available online: https://cmr.earthdata.nasa.gov/search/concepts/C2248652620-GES_DISC.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X. Comparison Analysis of the Global Carbon Dioxide Concentration Column Derived from SCIAMACHY, AIRS, and GOSAT with Surface Station Measurements. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2015, 36, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA National Centers of Environmental Information. Global Surface Summary of the Day—GSOD; National Centers of Environmental Information: Asheville, NC, USA, 1999.

- Peng, S.; Ding, Y.; Li, Z. High-Spatial-Resolution Monthly Precipitation Dataset over China during 1901–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2019, 11, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Ding, Y.; Li, W.; Li, Z. 1-Km Monthly Mean Temperature Dataset for China (1901–2024). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 11, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. The 30 m Annual Land Cover Datasets and Its Dynamics in China from 1985 to 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 13, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Shen, W.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, Y. China Regional 250m Normalized Difference Vegetation Index Data Set (2000–2024); National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lebakula, V.; Epting, J.; Moehl, J.; Stipek, C.; Adams, D.; Reith, A.; Kaufman, J.; Gonzales, J.; Reynolds, B.; Basford, S.; et al. LandScan Silver Edition 2024. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/2574458 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Juhui Data Shanghai Housing Price 2023. 2023. Available online: https://fangjia.gotohui.com/years/3/2023/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Khamdan, S.A.A.; Al Madany, I.M.; Buhussain, E. Temporal and Spatial Variations of the Quality of Ambient Air in the Kingdom of Bahrain during 2007. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 154, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, P.E.; Najab, J. Mann-Whitney U Test. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; Weiner, I.B., Craighead, W.E., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 1. ISBN 978-0-470-17024-3. [Google Scholar]

- Aref’ev, V.N.; Kamenogradsky, N.Y.; Kashin, F.V.; Shilkin, A.V. Background Component of Carbon Dioxide Concentration in the Near-Surface Air. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2014, 50, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurney, K.R.; Liang, J.; O’Keeffe, D.; Patarasuk, R.; Hutchins, M.; Huang, J.; Rao, P.; Song, Y. Comparison of Global Downscaled Versus Bottom-Up Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions at the Urban Scale in Four U.S. Urban Areas. JGR Atmos. 2019, 124, 2823–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Yang, L.; Yu, M.; Yu, M. Estimation, Characteristics, and Determinants of Energy-Related Industrial CO2 Emissions in Shanghai (China), 1994–2009. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 6476–6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, D.; Kuhlmann, G.; Marshall, J.; Clément, V.; Fuhrer, O.; Broquet, G.; Löscher, A.; Meijer, Y. Accounting for the Vertical Distribution of Emissions in Atmospheric CO2 Simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 4541–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępalska, D.; Myszkowska, D.; Piotrowicz, K.; Kluska, K.; Chłopek, K.; Grewling, Ł.; Lafférsová, J.; Majkowska-Wojciechowska, B.; Malkiewicz, M.; Piotrowska-Weryszko, K.; et al. High Ambrosia Pollen Concentrations in Poland Respecting the Long Distance Transport (LDT). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winderlich, J.; Chen, H.; Gerbig, C.; Seifert, T.; Kolle, O.; Lavrič, J.V.; Kaiser, C.; Höfer, A.; Heimann, M. Continuous Low-Maintenance CO2/CH4 /H2 O Measurements at the Zotino Tall Tower Observatory (ZOTTO) in Central Siberia. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2010, 3, 1113–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteki, K.; Prakash, N.; Li, Y.; Mu, C.; Du, K. Seasonal Variation of CO2 Vertical Distribution in the Atmospheric Boundary Layer and Impact of Meteorological Parameters. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2017, 11, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Guan, D.; Zhao, X.; Han, S.; Jin, C.; Yu, G. Characteristic of the energy balance in broad-leaved Korean pine forest of northeastern China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2005, 25, 2520–2526. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.; Jeong, S.; Park, H.; Sim, S.; Hong, J.; Oh, E. Comprehensive Assessment of Vertical Variations in Urban Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations by Using Tall Tower Measurement and an Atmospheric Transport Model. Urban Clim. 2022, 45, 101283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.M.; Branham, M.; Hutchins, M.G.; Welker, J.; Woodard, D.L.; Badurek, C.A.; Ruseva, T.; Marland, E.; Marland, G. The Role of CO2 Emissions from Large Point Sources in Emissions Totals, Responsibility, and Policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 44, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Jeong, S.; Koo, J.-H.; Sim, S.; Bae, Y.; Kim, Y.; Park, C.; Bang, J. Lessons from COVID-19 and Seoul: Effects of Reduced Human Activity from Social Distancing on Urban CO2 Concentration and Air Quality. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2021, 21, 200376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassler, B.; McDonald, B.C.; Frost, G.J.; Borbon, A.; Carslaw, D.C.; Civerolo, K.; Granier, C.; Monks, P.S.; Monks, S.; Parrish, D.D.; et al. Analysis of Long-term Observations of NOx and CO in Megacities and Application to Constraining Emissions Inventories. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 9920–9930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, S.H.; Fan, H.; Habib, Y.; Riaz, A. Non-Linear Relationship between Urbanization Paths and CO2 Emissions: A Case of South, South-East and East Asian Economies. Urban Clim. 2021, 37, 100814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, L.; Cui, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, J.; Streets, D.G.; Lin, B. Effects of Urbanization on Airport CO2 Emissions: A Geographically Weighted Approach Using Nighttime Light Data in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Woo, D.; Lee, S.-B.; Bae, G.-N. On-Road Measurements of Ultrafine Particles and Associated Air Pollutants in a Densely Populated Area of Seoul, Korea. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, H.A.; Dixon-Hardy, D.; Wadud, Z. Aircraft Cost Index and the Future of Carbon Emissions from Air Travel. Appl. Energy 2016, 164, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Gong, Y.; Escobedo, F.J.; Bracho, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, M. Measuring Multi-Scale Urban Forest Carbon Flux Dynamics Using an Integrated Eddy Covariance Technique. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarkamand, S.; Wooldridge, C.; Darbra, R.M. Review of Initiatives and Methodologies to Reduce CO2 Emissions and Climate Change Effects in Ports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, I.; Denier Van Der Gon, H.A.C.; Visschedijk, A.J.H.; Moerman, M.M.; Chen, H.; Van Der Molen, M.K.; Peters, W. Interpreting Continuous In-Situ Observations of Carbon Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide in the Urban Port Area of Rotterdam. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2017, 8, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imasu, R.; Tanabe, Y. Diurnal and Seasonal Variations of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Concentration in Urban, Suburban, and Rural Areas around Tokyo. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Data Source | Temporal Coverage | Spatial Resolution | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBLH (Planetary Boundary Layer Height) | ERA5 reanalysis dataset, ECMWF | August 2024–August 2025, hourly | 0.25° × 0.25° | 31.25° N, 121.50° E (SC station at 31.23° N, 121.48° E) |

| Variable | VIF | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|

| Population density | 1.520 | 0.658 |

| Second-hand housing price | 4.796 | 0.208 |

| New housing price | 4.351 | 0.230 |

| Water system | 1.063 | 0.941 |

| Impervious surface | 2.693 | 0.371 |

| Distance to emissions | 3.603 | 0.278 |

| Longitude | 10.022 | 0.100 |

| Local road network | 1.462 | 0.684 |

| Highway density | 1.078 | 0.927 |

| NDVI | 1.111 | 0.900 |

| Average wind speed | 3.200 | 0.312 |

| Average precipitation | 1.999 | 0.500 |

| Average temperature | 3.802 | 0.263 |

| Districts | Mean CO2 (ppm) | Std |

|---|---|---|

| Putuo (Urban) | 425.35 | 0.295 |

| Jingan (Urban) | 425.18 | 0.565 |

| Baoshan (Urban–Suburban) | 425.11 | 0.559 |

| Hongkou (Urban) | 424.95 | 0.490 |

| Xuhui (Urban) | 424.74 | 1.001 |

| Yangpu (Urban) | 424.19 | 0.298 |

| Huangpu (Urban) | 424.05 | 0.375 |

| Changning (Urban) | 423.78 | 0.583 |

| Chongming (Suburban) | 423.66 | 0.533 |

| Minhang (Urban–Suburban) | 423.30 | 0.776 |

| Pudong (Urban–Suburban) | 423.24 | 0.821 |

| Qingpu (Suburban) | 422.98 | 0.388 |

| Jiading (Suburban) | 422.85 | 0.407 |

| Jinshan (Suburban) | 422.72 | 0.409 |

| Fengxian (Suburban) | 422.61 | 0.587 |

| Songjiang (Suburban) | 422.58 | 0.415 |

| Coef. | Std. Coef. | Std. Error | t | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 423.401 | - | 0.497 | 852.732 | 0.000 ** | 422.428~424.374 |

| Population density | 0.021 | 0.025 | 0.008 | 2.680 | 0.007 ** | 0.006~0.036 |

| New housing price | 0.000 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 2.876 | 0.004 ** | 0.000~0.000 |

| Water system | −0.000 | −0.024 | 0.000 | −3.086 | 0.002 ** | −0.000~−0.000 |

| Impervious surface | −0.000 | −0.107 | 0.000 | −8.683 | 0.000 ** | −0.000~−0.000 |

| Distance to emissions | −0.000 | −0.750 | 0.000 | −59.844 | 0.000 ** | −0.000~−0.000 |

| Local road network | −0.060 | −0.053 | 0.010 | −5.792 | 0.000 ** | −0.081~−0.040 |

| Highway density | −0.076 | −0.023 | 0.026 | −2.947 | 0.003 ** | −0.126~−0.025 |

| NDVI | −0.217 | −0.015 | 0.115 | −1.881 | 0.060 | −0.443~0.009 |

| Average wind speed | −0.168 | −0.205 | 0.007 | −23.375 | 0.000 ** | −0.182~−0.154 |

| Average precipitation | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.007 | 1.760 | 0.078 | −0.001~0.025 |

| Average temperature | 0.751 | 0.183 | 0.041 | 18.128 | 0.000 ** | 0.670~0.832 |

| R2 | 0.670 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.669 | |||||

| F | F(11,5615) = 1036.036, p = 0.000 | |||||

| Durbin-Watson | 0.152 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, L.; Fu, Q.; Yang, F.; Shao, Y.; Liu, C. Intra-Urban CO2 Spatiotemporal Patterns and Driving Factors Using Multi-Source Data and AI Methods: A Case Study of Shanghai, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310794

Pan L, Fu Q, Yang F, Shao Y, Liu C. Intra-Urban CO2 Spatiotemporal Patterns and Driving Factors Using Multi-Source Data and AI Methods: A Case Study of Shanghai, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310794

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Leyi, Qingyan Fu, Fan Yang, Yuchen Shao, and Chao Liu. 2025. "Intra-Urban CO2 Spatiotemporal Patterns and Driving Factors Using Multi-Source Data and AI Methods: A Case Study of Shanghai, China" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310794

APA StylePan, L., Fu, Q., Yang, F., Shao, Y., & Liu, C. (2025). Intra-Urban CO2 Spatiotemporal Patterns and Driving Factors Using Multi-Source Data and AI Methods: A Case Study of Shanghai, China. Sustainability, 17(23), 10794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310794