Enhancing Soil Texture Mapping and Drought Stress Assessment Through Dual-Phase Remote Sensing in Typical Black Soil Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Acquisition and Processing

2.2.1. Sample Point Data Acquisition

2.2.2. Image Acquisition and Treatment

2.2.3. Determination of Yearly Information

2.3. Establishment and Validation of Random Forest Prediction Models

2.4. Correlation Analysis

2.5. Elasticity Analysis

2.6. Analysis of the Effect of Soil Moisture Content on the Accuracy of Soil Texture Prediction

2.7. Methods

- Data acquisition and model selection

- 2.

- Dual-phase image combination and prediction optimization

- 3.

- Drought year identification and crop growth status extraction

- 4.

- Analysis of the correlation between Soil texture and crop growth

- 5.

- Quantitative evaluation of drought stress threshold

3. Results

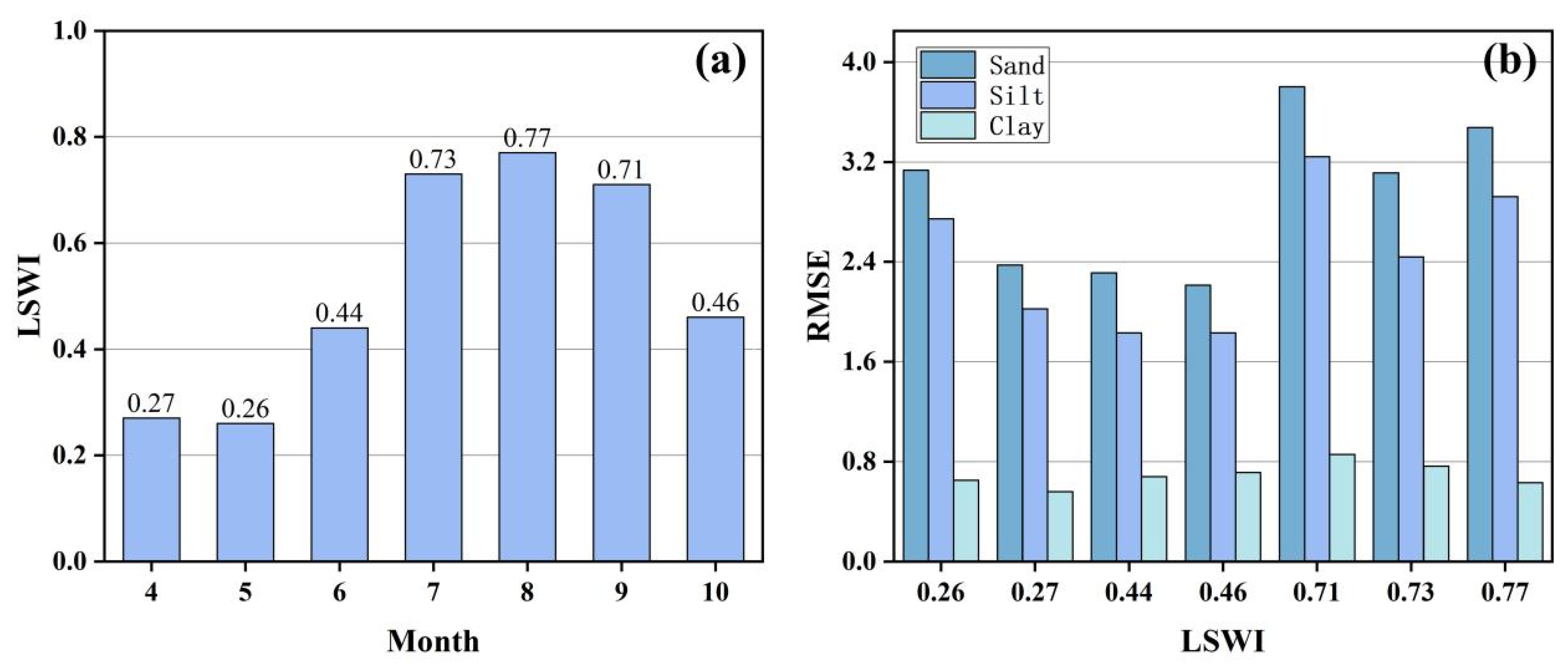

3.1. Accuracy Analysis of Soil Texture Prediction from Single Time-Phase Remote Sensing Images

3.2. Improved Accuracy of Soil Texture Prediction from Dual Time-Phase Remote Sensing Imagery

3.3. Spatial Distribution of Soil Texture in the Study Area

3.4. Influence of Soil Texture on Crop Growth in Dry Years and Identification of Effect Thresholds for Important Indicators

4. Discussion

4.1. Reasons Affecting the Accuracy of Soil Texture Mapping

4.2. The Extent to Which Soil Texture Affects Crop Growth

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, W. Combined effect of different amounts of irrigation and mulch films on physiological indexes and yield of drip-irrigated maize (Zea mays L.). Water 2019, 11, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian-Chakan, A.; Minasny, B.; Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Akbarifazli, R.; Darvishpasand, Z.; Khordehbin, S. Some practical aspects of predicting texture data in digital soil mapping. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 194, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkl, I.; Ließ, M. On the benefits of clustering approaches in digital soil mapping: An application example concerning soil texture regionalization. Soil 2022, 8, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, V.; Singh, C.; Sidhu, A.; Thind, S. Irrigation, tillage and mulching effects on soybean yield and water productivity in relation to soil texture. Agric. Water Manag. 2011, 98, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerji, N.; Mastrorilli, M. The effect of soil texture on the water use efficiency of irrigated crops: Results of a multi-year experiment carried out in the Mediterranean region. Eur. J. Agron. 2009, 30, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Hao, S. Effect of different textural soils on rhizosphere microorganisms and enzyme activities in maize. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2007, 40, 412–418. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, X. Effects of soil texture on soil water movement and transport on slope land. J. Irrig. Drain. 2008, 27, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ji, L.; Zhang, J.; Meng, L. Assessing the Spatial–Temporal Pattern of Spring Maize Drought in Northeast China Using an Optimised Remote Sensing Index. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Chen, J.; Nie, T.; Dai, C. Spatial–temporal changes in meteorological and agricultural droughts in Northeast China: Change patterns, response relationships and causes. Nat. Hazards 2022, 110, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, C.P.; Mohtadi, S.; Cane, M.A.; Seager, R.; Kushnir, Y. Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3241–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Men, Q.; Zhong, X.; Xie, X. Field characters of soil temperature under the wide plastic-mulch. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2001, 17, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Chen, B.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, P.; Lou, S.; Peng, X.; He, J. Effect of nitrogen applied levels on the dynamics of biomass, nitrogen accumulation of cotton plant on different soil textures. Acta Agric. Boreali Occident. Sin. 2009, 18, 160–166. [Google Scholar]

- McBratney, A.B.; Santos, M.M.; Minasny, B. On digital soil mapping. Geoderma 2003, 117, 3–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharumarajan, S.; Hegde, R.; Janani, N.; Singh, S. The need for digital soil mapping in India. Geoderma Reg. 2019, 16, e00204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Bao, Y.; Luo, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. SOC content of global Mollisols at a 30 m spatial resolution from 1984 to 2021 generated by the novel ML-CNN prediction model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 300, 113911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Luo, C.; Meng, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, H. Intelligent mapping paradigm to overcome systematic bias in remote sensing SOC estimation: A case study of the black soil region in China and the United States. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 230, 644–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittstruck, L.; Waske, B.; Jarmer, T. Multi-Modal Vision Transformer for high-resolution soil texture prediction of German agricultural soils using remote sensing imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 331, 114985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobin, A.; Campling, P.; Feyen, J. Soil-landscape modelling to quantify spatial variability of soil texture. Phys. Chem. Earth Part B Hydrol. Ocean. Atmos. 2001, 26, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chow, T.L.; Rees, H.W.; Yang, Q.; Xing, Z.; Meng, F.-R. Predict soil texture distributions using an artificial neural network model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2009, 65, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, C.; Dharumarajan, S.; Féret, J.-B.; Lagacherie, P.; Ruiz, L.; Sekhar, M. Use of sentinel-2 time-series images for classification and uncertainty analysis of inherent biophysical property: Case of soil texture mapping. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shi, W.; Xu, Z. Systematic comparison of five machine-learning models in classification and interpolation of soil particle size fractions using different transformed data. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 2505–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousbih, S.; Zribi, M.; Pelletier, C.; Gorrab, A.; Lili-Chabaane, Z.; Baghdadi, N.; Ben Aissa, N.; Mougenot, B. Soil texture estimation using radar and optical data from Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Ashraf, M.N.; Sanaullah, M.; Maqsood, M.A.; Waqas, M.A.; Rahman, S.U.; Hussain, S.; Ahmad, H.R.; Mustafa, A.; Minggang, X. Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Mineralization Potential of Manures Regulated by Soil Microbial Activities in Contrasting Soil Textures. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 3056–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Shi, H.-B.; Li, R.-P.; Miao, Q.-F.; Tian, F.; Yu, D.-D.; Zhou, L.-Y. Assessing the efficiency of subsurface drain in controlling soil salinization in Hetao Irrigation District. J. Irrig. Drain. 2020, 39, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Dan, Y.; Qiao, R.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J.; Wu, J. How to quantify the cooling effect of urban parks? Linking maximum and accumulation perspectives. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 252, 112135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianying, X.; Jixing, C.; Yanxu, L. Partitioned responses of ecosystem services and their tradeoffs to human activities in the Belt and Road region. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 123205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Tian, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Hu, Y.N.; Wu, J. Ecosystem services response to urbanization in metropolitan areas: Thresholds identification. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francesco Ficetola, G.; Denoël, M. Ecological thresholds: An assessment of methods to identify abrupt changes in species–habitat relationships. Ecography 2009, 32, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Luo, C.; Liu, H. Integrative remote sensing and machine learning approaches for SOC and TN spatial distribution: Unveiling C: N ratio in Black Soil region. Soil Tillage Res. 2026, 255, 106809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zang, D.; Yang, Q.; Liu, H.; Luo, C. Using Satellites to Monitor Soil Texture in Typical Black Soil Areas and Assess Its Impact on Crop Growth. Agriculture 2025, 15, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H. Integration of bare soil and crop growth remote sensing data to improve the accuracy of soil organic matter mapping in black soil areas. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 244, 106269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Luo, C.; Liu, H. Enhancing soil organic matter mapping in saline-alkali and black soil areas with prior knowledge and multi-temporal remote sensing. J. Integr. Agric. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Ghorbanian, A.; Ahmadi, S.A.; Kakooei, M.; Moghimi, A.; Mirmazloumi, S.M.; Moghaddam, S.H.A.; Mahdavi, S.; Ghahremanloo, M.; Parsian, S. Google earth engine cloud computing platform for remote sensing big data applications: A comprehensive review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 5326–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.R.; Chakraborty, P.; Panigrahi, N.; Vasava, H.B.; Reddy, N.N.; Roy, S.; Majeed, I.; Das, B.S. Estimation of soil texture using Sentinel-2 multispectral imaging data: An ensemble modeling approach. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 213, 105134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.L.; Alonzo, M.; Meerdink, S.K.; Allen, M.A.; Tague, C.L.; Roberts, D.A.; McFadden, J.P. Seasonal and interannual drought responses of vegetation in a California urbanized area measured using complementary remote sensing indices. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 183, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, J.; Cai, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhou, W.; Hu, Q.; Wang, C.; You, L.; Xu, B. A phenology-based vegetation index for improving ratoon rice mapping using harmonized Landsat and Sentinel-2 data. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 1164–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, F.Y. The inverse texture effect of soil on vegetation in temperate grasslands of China: Benchmarking soil texture effect. Geoderma 2023, 438, 116641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Zhang, X.; Shang, K.; Xiao, Q.; Wang, W.; Rehman, A.U. Removal of environmental influences for estimating soil texture fractions based on ZY1 satellite hyperspectral images. Catena 2024, 236, 107713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Fu, Z.; Wang, K. Effects of vegetation restoration on soil properties along an elevation gradient in the karst region of southwest China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 320, 107572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Mapping of soil organic matter in a typical black soil area using Landsat-8 synthetic images at different time periods. Catena 2023, 231, 107336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Bao, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. A new digital soil mapping method with temporal-spatial-spectral information derived from multi-source satellite images. Geoderma 2022, 425, 116065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Qin, L.; Huang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; He, H. Water footprint of rain-fed maize in different growth stages and associated climatic driving forces in Northeast China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 263, 107463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Singh, V.P.; Xu, C.-Y. Modified drought severity index: Model improvement and its application in drought monitoring in China. J. Hydrol. 2022, 612, 128097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Rattan, B.; Sekharan, S.; Manna, U. Quantifying the interactive effect of water absorbing polymer (WAP)-soil texture on plant available water content and irrigation frequency. Geoderma 2020, 368, 114310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Chen, F.; Yu, H.; Hu, J.; Zhou, X.; Xu, H. PS-MTL-LUCAS: A partially shared multi-task learning model for simultaneously predicting multiple soil properties. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Guo, X.; Xu, Z.; Ding, M. Soil properties: Their prediction and feature extraction from the LUCAS spectral library using deep convolutional neural networks. Geoderma 2021, 402, 115366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Yao, F.; Meng, X.; Fan, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Mouazen, A.M. Dynamic modeling of topsoil organic carbon and its scenarios forecast in global Mollisols regions. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 421, 138544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankmüller, F.J.; Delval, L.; Lehmann, P.; Baur, M.J.; Cecere, A.; Wolf, S.; Or, D.; Javaux, M.; Carminati, A. Global influence of soil texture on ecosystem water limitation. Nature 2024, 635, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Sentinel-2 Bands | Central Wavelength (μm) | Resolution (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 April 2021 17 May 2021 23 June 2021 18 July 2021 17 August 2021 6 September 2021 1 October 2021 | Band1-Coastal aerosol | 0.443 | 60 |

| Band2-Blue | 0.490 | 10 | |

| Band3-Green | 0.560 | 10 | |

| Band4-Red | 0.665 | 10 | |

| Band5-Vegetation Red Edge | 0.705 | 20 | |

| Band6-Vegetation Red Edge | 0.740 | 20 | |

| Band7-Vegetation Red Edge | 0.783 | 20 | |

| Band8-NIR | 0.842 | 10 | |

| Band8A-Vegetation Red Edge | 0.865 | 20 | |

| Band9-Water vapour | 0.945 | 60 | |

| Band11-SWIR1 | 1.610 | 20 | |

| Band12-SWIR2 | 2.190 | 20 |

| Date | Sand | Silt | Clay | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE (%) | R2 | RMSE (%) | R2 | RMSE (%) | |

| April | 0.617 | 10.210 | 0.606 | 8.648 | 0.604 | 1.945 |

| May | 0.587 | 10.601 | 0.575 | 8.976 | 0.545 | 2.084 |

| June | 0.446 | 12.288 | 0.452 | 10.193 | 0.318 | 2.552 |

| July | 0.402 | 12.759 | 0.412 | 10.563 | 0.307 | 2.573 |

| August | 0.488 | 11.806 | 0.501 | 9.724 | 0.345 | 2.501 |

| September | 0.341 | 13.399 | 0.354 | 11.068 | 0.240 | 2.693 |

| October | 0.423 | 12.538 | 0.438 | 10.327 | 0.308 | 2.570 |

| DPI | Sand | Silt | Clay | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE (%) | R2 Improvement | R2 | RMSE (%) | R2 Improvement | R2 | RMSE (%) | R2 Improvement | |

| April + May | 0.632 | 10.017 | +0.015 | 0.618 | 8.516 | +0.012 | 0.602 | 1.949 | −0.002 |

| April + June | 0.629 | 10.050 | +0.012 | 0.622 | 8.468 | +0.016 | 0.590 | 1.979 | −0.014 |

| April + October | 0.677 | 9.386 | +0.060 | 0.660 | 8.034 | +0.054 | 0.658 | 1.807 | +0.054 |

| May + June | 0.634 | 9.986 | +0.017 | 0.626 | 8.417 | +0.020 | 0.580 | 2.002 | −0.024 |

| May + October | 0.652 | 9.734 | +0.035 | 0.645 | 8.207 | +0.039 | 0.570 | 2.027 | −0.034 |

| June + October | 0.532 | 11.295 | −0.085 | 0.534 | 9.403 | −0.072 | 0.409 | 2.375 | −0.195 |

| Sand | Silt | Clay | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean | −0.163 * | 0.147 * | 0.092 * |

| Maize | −0.375 * | 0.38 * | 0.247 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Dou, W.; Gao, L.; Li, X.; Luo, C. Enhancing Soil Texture Mapping and Drought Stress Assessment Through Dual-Phase Remote Sensing in Typical Black Soil Regions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310793

Zhang W, Dou W, Gao L, Li X, Luo C. Enhancing Soil Texture Mapping and Drought Stress Assessment Through Dual-Phase Remote Sensing in Typical Black Soil Regions. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310793

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wenqi, Wenzhu Dou, Liren Gao, Xue Li, and Chong Luo. 2025. "Enhancing Soil Texture Mapping and Drought Stress Assessment Through Dual-Phase Remote Sensing in Typical Black Soil Regions" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310793

APA StyleZhang, W., Dou, W., Gao, L., Li, X., & Luo, C. (2025). Enhancing Soil Texture Mapping and Drought Stress Assessment Through Dual-Phase Remote Sensing in Typical Black Soil Regions. Sustainability, 17(23), 10793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310793