Inulin Reverses Intestinal Mrp2 Downregulation in a Diet-Induced Obesity Mouse Model: Role of Intestinal Microbiota as a Pivotal Modulator

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Animals and Treatments

2.3. Specimen Collection

2.4. Biochemical Assays

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

2.6. Microscopy Studies

2.7. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Studies

2.8. Assessment of Mrp2 Activity In Vitro

2.9. Intestinal Microbiome Analysis

2.10. Assessment of Intestinal Paracellular Permeability

2.11. Assessment of Plasma Endotoxin Levels

2.12. Assessment of Lipid Peroxidation and ROS Production

2.13. Assessment of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of the HFD-Induced Obesity Model

3.2. Effect of HFD on Mrp2 Expression and Activity

3.3. Effect of HFD and Inulin Treatment on the Intestinal Microbiota

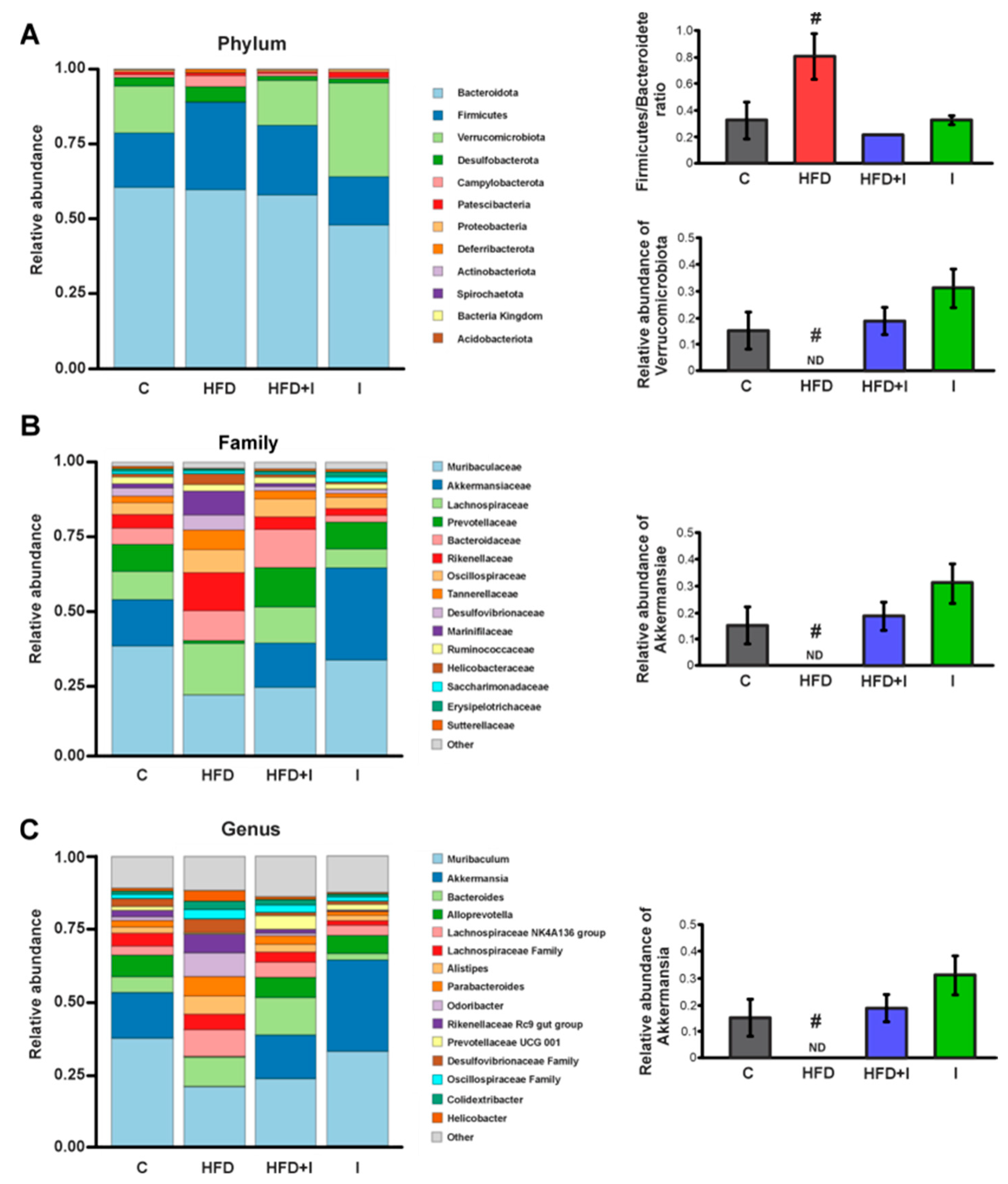

3.4. Effect of HFD and Inulin Treatment on Physiological Parameters and Energy Intake

3.5. Effect of HFD and Inulin Treatment on Biochemical Parameters

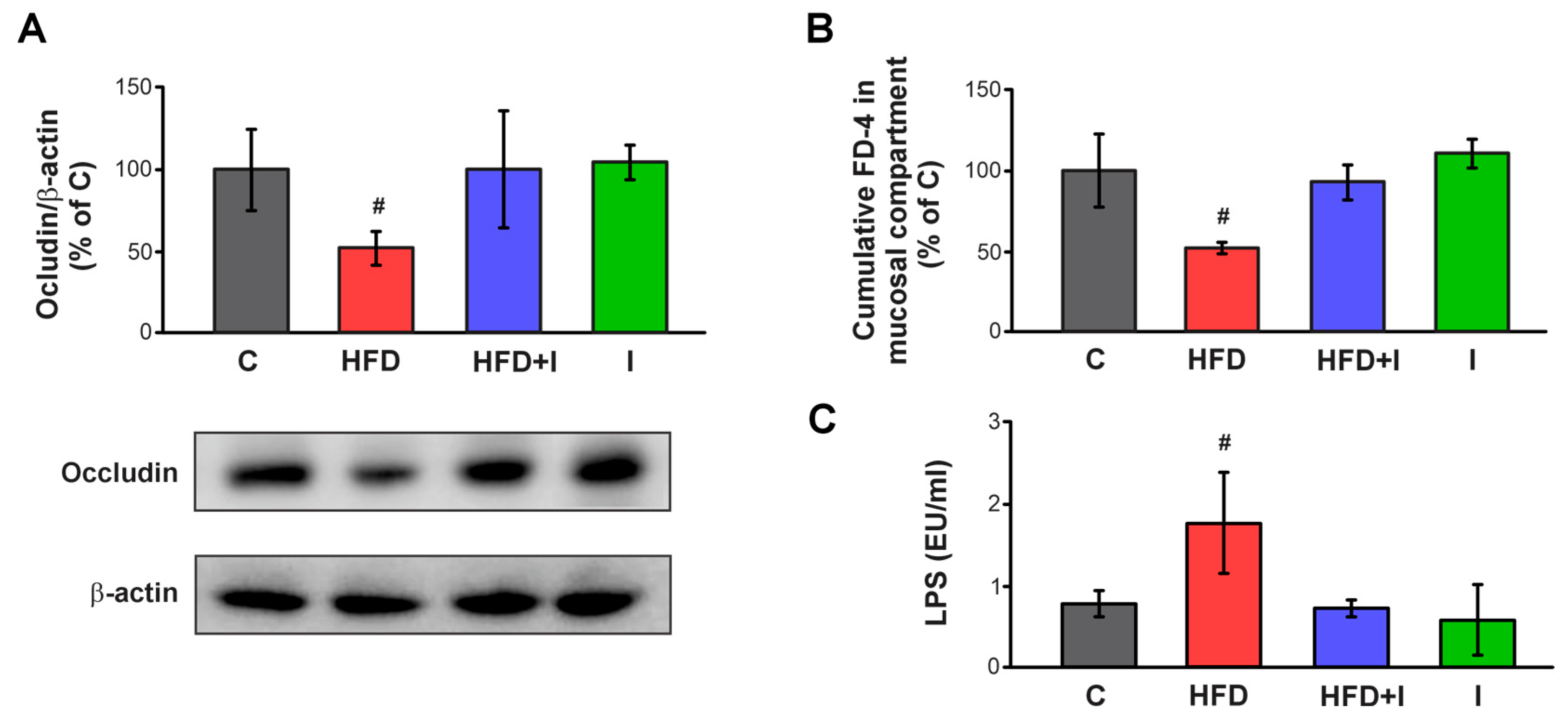

3.6. Effect of HFD and Inulin Treatment on Intestinal Paracellular Barrier and Plasma Endotoxin Levels

3.7. Effect of HFD and Inulin Treatment on Intestinal Proinflammatory Cytokine Levels

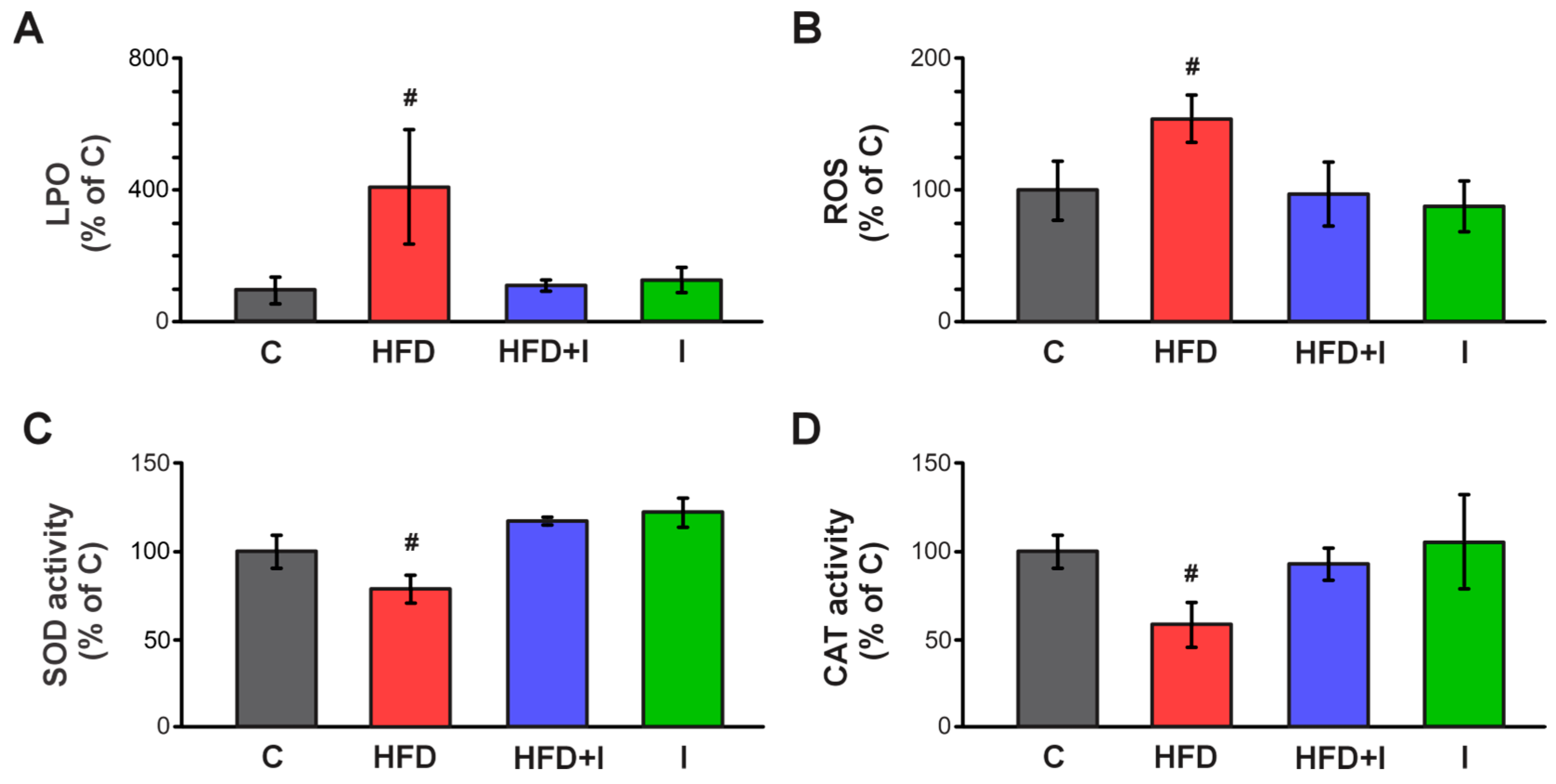

3.8. Effect of HFD and Inulin Treatment on Intestinal Redox Balance and Antioxidant Defenses

3.9. Effect of HFD Administration and Inulin Treatment on Intestinal Mrp2

3.10. Correlation Analysis Between Akkermansia Abundance and Metabolic, Inflammatory, OS, Paracellular Barrier and Mrp2 Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABC | ATP-Binding Cassette |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BBM | Brush Border Membranes |

| BW | Body weight |

| C | Control |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CDNB | 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene |

| DCF | 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein |

| DCFH-DA | Fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| DNP-SG | dinitrophenyl-S-glutathione |

| FD-4 | fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran |

| FRD | Fructose-Rich Diet |

| GTT | Glucose Tolerance Test |

| HFD | High-Fat Diet |

| I | Inulin |

| IM | Intestinal Microbiota |

| ITT | Intraperitoneal Insulin Tolerance Test |

| LPO | Lipoperoxidation |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| Mrp2/Abcc2 | Multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 |

| MS | Metabolic Syndrome |

| NBT | Nitroblue tetrazolium |

| OS | Oxidative Stress |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances |

| w/w | Weight to weight |

References

- Mottino, A.D.; Hoffman, T.; Jennes, L.; Vore, M. Expression and Localization of Multidrug Resistant Protein Mrp2 in Rat Small Intestine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 293, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, C.G.; de Waart, D.R.; Ottenhoff, R.; Schoots, I.G.; Elferink, R.P.J.O. Increased Bioavailability of the Food-Derived Carcinogen 2-Amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine in MRP2-Deficient Rats. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 59, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Takano, M. Intestinal Efflux Transporters and Drug Absorption. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2008, 4, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, M.R.; Tocchetti, G.N.; Rigalli, J.P.; Mottino, A.D.; Villanueva, S.S.M. Physiological and Pathophysiological Factors Affecting the Expression and Activity of the Drug Transporter MRP2 in Intestine. Impact on Its Function as Membrane Barrier. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 109, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.V.; Pedersen, O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, J.M.; Martínez-Martínez, D.; Rubio, T.; Gracia, C.; Peña, M.; Latorre, A.; Moya, A.; Garay, C.P. Health and Disease Imprinted in the Time Variability of the Human Microbiome. mSystems 2017, 2, e00144-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.; Blaser, M.J. The Human Microbiome: At the Interface of Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, R.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Klein, S.; Gordon, J.I. Microbial Ecology: Human Gut Microbes Associated with Obesity. Nature 2006, 444, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ridaura, V.K.; Faith, J.J.; Rey, F.E.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I. The Effect of Diet on the Human Gut Microbiome: A Metagenomic Analysis in Humanized Gnotobiotic Mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2009, 1, 6ra14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrieze, A.; Van Nood, E.; Holleman, F.; Salojärvi, J.; Kootte, R.S.; Bartelsman, J.F.W.M.; Dallinga-Thie, G.M.; Ackermans, M.T.; Serlie, M.J.; Oozeer, R.; et al. Transfer of Intestinal Microbiota from Lean Donors Increases Insulin Sensitivity in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 913–916.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L. The Gut Microbiota and Obesity: From Correlation to Causality. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bays, H.E.; Bindlish, S.; Clayton, T.L. Obesity, Diabetes Mellitus, and Cardiometabolic Risk: An Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Clinical Practice Statement (CPS) 2023. Obes. Pillars 2023, 5, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.; Irfan, W.; Jameel, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R.K. Obesity and Cancer: A Current Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Outcomes, and Management. Cancers 2023, 15, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Amar, J.; Iglesias, M.A.; Poggi, M.; Knauf, C.; Bastelica, D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.M.; Chabo, C.; et al. Metabolic Endotoxemia Initiates Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Bibiloni, R.; Knauf, C.; Waget, A.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Delzenne, N.M.; Burcelin, R. Changes in Gut Microbiota Control Metabolic Endotoxemia-Induced Inflammation in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity and Diabetes in Mice. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1470–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cândido, F.G.; Valente, F.X.; Grześkowiak, Ł.M.; Moreira, A.P.B.; Rocha, D.M.U.P.; Alfenas, R.d.C.G. Impact of Dietary Fat on Gut Microbiota and Low-Grade Systemic Inflammation: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications on Obesity. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 69, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randeni, N.; Bordiga, M.; Xu, B. A Comprehensive Review of the Triangular Relationship among Diet–Gut Microbiota–Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesza, I.J.; Malesza, M.; Walkowiak, J.; Mussin, N.; Walkowiak, D.; Aringazina, R.; Bartkowiak-Wieczorek, J.; Mądry, E. High-Fat, Western-Style Diet, Systemic Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota: A Narrative Review. Cells 2021, 10, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, M.R.; Dominguez, C.J.; Zecchinati, F.; Tocchetti, G.N.; Mottino, A.D.; Villanueva, S.S.M. Role of Interleukin 1 Beta in the Regulation of Rat Intestinal Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 2 under Conditions of Experimental Endotoxemia. Toxicology 2020, 441, 152527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londero, A.S.; Arana, M.R.; Perdomo, V.G.; Tocchetti, G.N.; Zecchinati, F.; Ghanem, C.I.; Ruiz, M.L.; Rigalli, J.P.; Mottino, A.D.; García, F.; et al. Intestinal Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 2 Is down-Regulated in Fructose-Fed Rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 40, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zecchinati, F.; Barranco, M.M.; Arana, M.R.; Tocchetti, G.N.; Domínguez, C.J.; Perdomo, V.G.; Ruiz, M.L.; Mottino, A.D.; García, F.; Villanueva, S.S.M. Reversion of Down-Regulation of Intestinal Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 2 in Fructose-Fed Rats by Geraniol and Vitamin C: Potential Role of Inflammatory Response and Oxidative Stress. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 68, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Luccia, B.; Crescenzo, R.; Mazzoli, A.; Cigliano, L.; Venditti, P.; Walser, J.C.; Widmer, A.; Baccigalupi, L.; Ricca, E.; Iossa, S. Rescue of Fructose-Induced Metabolic Syndrome by Antibiotics or Faecal Transplantation in a Rat Model of Obesity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, G.; Mohanty, B. Probiotics Modulation of the Endotoxemic Effect on the Gut and Liver of the Lipopolysaccharide Challenged Mice. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 48, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, C.; De Hoogd, S.; Brüggemann, R.J.M.; Knibbe, C.A.J. Obesity and Drug Pharmacology: A Review of the Influence of Obesity on Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Parameters. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Han, Y.; Huang, W.; Jin, M.; Gao, Z. The Influence of the Gut Microbiota on the Bioavailability of Oral Drugs. Acta Pharm. Sinica B. Chin. Acad. Med. Sci. 2021, 11, 1789–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuno, T.; Hirayama-Kurogi, M.; Ito, S.; Ohtsuki, S. Effect of Intestinal Flora on Protein Expression of Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes and Transporters in the Liver and Kidney of Germ-Free and Antibiotics-Treated Mice. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 2691–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momper, J.D.; Nigam, S.K. Developmental Regulation of Kidney and Liver Solute Carrier and ATP-Binding Cassette Drug Transporters and Drug Metabolizing Enzymes: The Role of Remote Organ Communication. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.; Gheorghe, C.E.; Lyte, J.M.; van de Wouw, M.; Boehme, M.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F.; Griffin, B.T.; Clarke, G.; Hyland, N.P. Gut Microbiome-Mediated Modulation of Hepatic Cytochrome P450 and P-Glycoprotein: Impact of Butyrate and Fructo-Oligosaccharide-Inulin. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2020, 72, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.; Meng, M.; Luo, P.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y. Tetrahydrocurcumin Alleviates Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis in Mice by Regulating Serum Lipids, Bile Acids, and Gut Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, L.L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhu, H.Z.; Cao, S.S.; Shi, Y.; Shangguan, H.Z.; Liu, J.P.; Xie, Y.D. Ameliorative Effect of Glycyrrhizic Acid on Diosbulbin B-Induced Liver Injury and Its Mechanism. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2025, 53, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; Zhu, H.; Shangguan, H.; Ding, L.; Zhang, D.; Deng, C.; Liu, J.; Xie, Y. Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. Attenuates Dioscorea bulbifera L.-Induced Liver Injury by Regulating the FXR/Nrf2-BAs-Related Proteins and Intestinal Microbiota. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 341, 119319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, R.; Guo, P.; Li, P.; Huang, X.; Wei, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhou, J.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; et al. Effects of Intestinal Microbiota on Pharmacokinetics of Cyclosporine a in Rats. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1032290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.L.; Alvarado, D.A.; Swanson, K.S.; Holscher, H.D. The Prebiotic Potential of Inulin-Type Fructans: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 492–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Mu, T.; Cao, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Ren, D.; Zhao, K. Response of Gut Microbiota and Ileal Transcriptome to Inulin Intervention in HFD Induced Obese Mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Dong, Y.; Jian, Z.; Li, Q.; Gong, L.; Tang, L.; Zhou, X.; Liu, M. Systematic Investigation of the Effects of Long-Term Administration of a High-Fat Diet on Drug Transporters in the Mouse Liver, Kidney and Intestine. Curr. Drug Metab. 2019, 20, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barranco, M.M.; Perdomo, V.G.; Zecchinati, F.; Manarin, R.; Massuh, G.; Sigal, N.; Vignaduzzo, S.; Mottino, A.D.; Villanueva, S.S.M.; García, F. Downregulation of Intestinal Multidrug Resistance Transporter 1 in Obese Mice: Effect on Its Barrier Function and Role of TNF-α Receptor 1 Signaling. Nutrition 2023, 111, 112050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barranco, M.M.; Zecchinati, F.; Perdomo, V.G.; Habib, M.J.; Rico, M.J.; Rozados, V.R.; Salazar, M.; Fusini, M.E.; Scharovsky, O.G.; Villanueva, S.S.M.; et al. Intestinal ABC Transporters: Influence on the Metronomic Cyclophosphamide-Induced Toxic Effect in an Obese Mouse Mammary Cancer Model. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2024, 492, 117130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambertucci, F.; Arboatti, A.; Sedlmeier, M.G.; Motiño, O.; Alvarez, M.d.L.; Ceballos, M.P.; Villar, S.R.; Roggero, E.; Monti, J.A.; Pisani, G.; et al. Disruption of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Receptor 1 Signaling Accelerates NAFLD Progression in Mice upon a High-Fat Diet. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 58, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecchinati, F.; Barranco, M.M.; Tocchetti, G.N.; Domínguez, C.J.; Arana, M.R.; Perdomo, V.G.; Mottino, A.D.; García, F.; Villanueva, S.S.M. Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 2 Is Negatively Regulated by Oxidative Stress in Rat Intestine via a Posttranslational Mechanism. Impact on Its Membrane Barrier Function. Toxicology 2021, 460, 152873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T.; He, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Z.; Lu, H.; Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, H. Inulin Exerts Beneficial Effects on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via Modulating Gut Microbiome and Suppressing the Lipopolysaccharide-Toll-Like Receptor 4-Mψ-Nuclear Factor-ΚB-Nod-Like Receptor Protein 3 Pathway via Gut-Liver Axis in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 558525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein Measurement with the Folin Phenol Reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottino, A.D.; Hoffman, T.; Jennes, L.; Cao, J.; Vore, M. Expression of Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 2 in Small Intestine from Pregnant and Postpartum Rats. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2001, 280, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, C.; Li, J.; Jia, Q.; Shi, Y.; Wang, P.; Guo, L.; Qiao, H.; et al. The Impact of High Polymerization Inulin on Body Weight Reduction in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice: Correlation with Cecal Akkermansia. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1428308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keely, S.; Rullay, A.; Wilson, C.; Carmichael, A.; Carrington, S.; Corfield, A.; Haddleton, D.M.; Brayden, D.J. In Vitro and Ex Vivo Intestinal Tissue Models to Measure Mucoadhesion of Poly (Methacrylate) and N-Trimethylated Chitosan Polymers. Pharm. Res. 2005, 22, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Rincon, N.; Wood, D.E.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Pockrandt, C.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L.; Steinegger, M. Metagenome Analysis Using the Kraken Software Suite. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 2815–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, D.; Arts, I.; Penders, J. MicroViz: An R Package for Microbiome Data Visualization and Statistics. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2011, 3, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for Lipid Peroxides in Animal Tissues by Thiobarbituric Acid Reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979, 95, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardi, L.L.; Zecchinati, F.; Perdomo, V.G.; Basiglio, C.L.; García, F.; Arana, M.R.; Villanueva, S.S.M. Oxidative Stress Promotes Post-Translational down-Regulation of MRP2 in Caco-2 Cells: Involvement of Proteasomal Degradation and Toxicological Implications. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 201, 115459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y.Y.; Ha, C.W.Y.; Campbell, C.R.; Mitchell, A.J.; Dinudom, A.; Oscarsson, J.; Cook, D.I.; Hunt, N.H.; Caterson, I.D.; Holmes, A.J.; et al. Increased Gut Permeability and Microbiota Change Associate with Mesenteric Fat Inflammation and Metabolic Dysfunction in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 34233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.A.; Lee, I.A.; Gu, W.; Hyam, S.R.; Kim, D.H. β-Sitosterol Attenuates High-Fat Diet-Induced Intestinal Inflammation in Mice by Inhibiting the Binding of Lipopolysaccharide to Toll-like Receptor 4 in the NF-ΚB Pathway. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Zhao, A.; Wang, Q.; Yang, X.; Ren, D. Supplementation of Inulin with Various Degree of Polymerization Ameliorates Liver Injury and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in High Fat-Fed Obese Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.L.A.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Liston, A.; Raes, J. How Informative Is the Mouse for Human Gut Microbiota Research? DMM Dis. Model. Mech. 2015, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez Dieguez, T.; Galvan, M.; López Rodriguez, G.; Olivo, D.; Olvera Nájera, M. Efecto de la dieta sobre la modulación de la microbiota en el desarrollo de la obesidad. RESPYN Rev. Salud Pública Y Nutr. 2018, 17, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Srivastava, G. Obesity Management in Children and Adolescents. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 52, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, R.; Schölmerich, J.; Bollheimer, L.C. High-Fat Diets: Modeling the Metabolic Disorders of Human Obesity in Rodents. Obesity 2007, 15, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzell, M.S.; Ahrén, B. The High-Fat Diet-Fed Mouse: A Model for Studying Mechanisms and Treatment of Impaired Glucose Tolerance and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2004, 53, S215–S219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, J.R.; Tomas, J.; Brenner, C.; Sansonetti, P.J. Impact of High-Fat Diet on the Intestinal Microbiota and Small Intestinal Physiology before and after the Onset of Obesity. Biochimie 2017, 141, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalitsky-Szirtes, J.; Shayeganpour, A.; Brocks, D.R.; Piquette-Miller, M. Suppression of Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes and Efflux Transporters in the Intestine of Endotoxin-Treated Rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delzenne, N.M.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Cani, P.D. Modulation of the Gut Microbiota by Nutrients with Prebiotic Properties: Consequences for Host Health in the Context of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011, 10 (Suppl. S1), S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ying, N.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, J.; Teow, S.Y.; Dong, W.; Lin, M.; Jiang, L.; Zheng, H. Amelioration of Obesity-Related Disorders in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice Following Fecal Microbiota Transplantation from Inulin-Dosed Mice. Molecules 2023, 28, 3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, L.; Jin, M.; Xu, L. Chain Length-Dependent Inulin Alleviates Diet-Induced Obesity and Metabolic Disorders in Mice. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 3470–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Mei, Y. Phellinus Linteus Polysaccharide Extract Improves Insulin Resistance by Regulating Gut Microbiota Composition. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, R.; Xue, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, C. Strain-Specific Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Two Akkermansia Muciniphila Strains on Chronic Colitis in Mice. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Feng, Y.; Duan, B.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, J. Isoorientin Alleviates DSS-Treated Acute Colitis in Mice by Regulating Intestinal Epithelial P-Glycoprotein (P-gp) Expression. DNA Cell Biol. 2024, 43, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, M.A.; Hoffmann, C.; Sherrill-Mix, S.A.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Hamady, M.; Chen, Y.Y.; Knight, R.; Ahima, R.S.; Bushman, F.; Wu, G.D. High-Fat Diet Determines the Composition of the Murine Gut Microbiome Independently of Obesity. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1716–1724.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolnick, D.I.; Snowberg, L.K.; Hirsch, P.E.; Lauber, C.L.; Org, E.; Parks, B.; Lusis, A.J.; Knight, R.; Caporaso, J.G.; Svanbäck, R. Individual Diet Has Sex-Dependent Effects on Vertebrate Gut Microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, M.S.; Newell, C.; Bomhof, M.R.; Reimer, R.A.; Hittel, D.S.; Rho, J.M.; Vogel, H.J.; Shearer, J. Metabolomic Modeling to Monitor Host Responsiveness to Gut Microbiota Manipulation in the BTBRT+tf/j Mouse. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Klaassen, C. Gender Differences in MRNA Expression of ATP-Binding Cassette Efflux and Bile Acid Transporters in Kidney, Liver, and Intestine of 5/6 Nephrectomized Rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zecchinati, F.; Ricardi, L.; Blancato, V.; Pereyra, E.; Arana, M.; Ghanem, C.; Perdomo, V.; Villanueva, S. Inulin Reverses Intestinal Mrp2 Downregulation in a Diet-Induced Obesity Mouse Model: Role of Intestinal Microbiota as a Pivotal Modulator. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1575. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121575

Zecchinati F, Ricardi L, Blancato V, Pereyra E, Arana M, Ghanem C, Perdomo V, Villanueva S. Inulin Reverses Intestinal Mrp2 Downregulation in a Diet-Induced Obesity Mouse Model: Role of Intestinal Microbiota as a Pivotal Modulator. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1575. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121575

Chicago/Turabian StyleZecchinati, Felipe, Laura Ricardi, Víctor Blancato, Emmanuel Pereyra, Maite Arana, Carolina Ghanem, Virginia Perdomo, and Silvina Villanueva. 2025. "Inulin Reverses Intestinal Mrp2 Downregulation in a Diet-Induced Obesity Mouse Model: Role of Intestinal Microbiota as a Pivotal Modulator" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1575. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121575

APA StyleZecchinati, F., Ricardi, L., Blancato, V., Pereyra, E., Arana, M., Ghanem, C., Perdomo, V., & Villanueva, S. (2025). Inulin Reverses Intestinal Mrp2 Downregulation in a Diet-Induced Obesity Mouse Model: Role of Intestinal Microbiota as a Pivotal Modulator. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1575. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121575