Microneedle Mediated Gas Delivery for Rapid Separation, Enhanced Drug Penetration, and Combined Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. MNs-Mediated Gas Delivery Facilitate Rapid Separation

3. MNs-Mediated Gas Delivery for Enhanced Drug Penetration

4. MNs-Mediated Gas Delivery for Combined Therapy

4.1. Gas Species for Disease Treatment

4.1.1. Hydrogen (H2)

4.1.2. Carbon Monoxide (CO)

4.1.3. Nitric Oxide (NO)

4.1.4. Oxygen (O2)

4.1.5. Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S)

4.1.6. Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

| Gas Type | Gas Carrier or Precursor | Driving Force or Stimulation | Treatment of Disease | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | Pt-Bi2S3 | Anti-4T1 tumor therapy | [57] | |

| Nanoscale CaH2 particles | Anti-orthotopic liver tumor therapy | [60] | ||

| Carbon/potassium doped heptazine-based red polymer carbon nitride (RPCN) | Anti-4T1 tumor therapy | [61] | ||

| CO | CORM (donor) | Treatment of inflammation, cardiovascular disease, microbial infections, cancer | [62] | |

| Chemiexcitation-triggered AIE nanobomb (PBPTV@mPEG(CO)) | Anti-4T1 tumor therapy | [63] | ||

| Gas nano-adjuvant (MTHMS) | Anti-4T1 tumor therapy | [64] | ||

| Hydrochloride-containing M2 exosomes (HAL@M2 Exo) | Anti-Atherosclerosis | [65] | ||

| NO | NO-loaded nanocapsules (NO-NCPs) | Anti-EMT6 tumor therapy | [68] | |

| Carbon-dot doped carbon nitrid and E. coli MG1655 (CCN@ E. coli) | Anti-4T1 tumor therapy | [69] | ||

| Electrostatically spun nanocomposite membrane (UCNP@PCN@LA-PVDF) | Antimicrobial therapy | [70] | ||

| Carboxymethyl chitosan/2,3,4-trihydroxybenzaldehyde/copper chloride/graphene oxide-N, N′-di-sec-butyl-N, N′-dinitroso-1,4-phenylenediamine hydrogel(CMCS/THB/Cu/GB) | Diabetic wound healing treatment | [71] | ||

| O2 | Iron oxide-linoleic acid hydroperoxide nanoparticles (IO-LAHP NPs) | Anti-U87MG tumor therapy | [74] | |

| Hemoglobin-nanoparticles @liposomes (Hb-NPs@liposome) | Anti-tumor therapy | [75] | ||

| Gel beads of S. elongatus PCC7942 | Diabetic wound healing therapy | [76] | ||

| Oxygen releasing microspheres (ORM) | Diabetic wound healing therapy | [77] | ||

| H2S | NAGYY (donor) | Alzheimer’s disease treatment | [79] | |

| MTHMS | Anti-4T1 tumor therapy | [64] | ||

| Ferrous sulfide-embedded bovine serum albumin nanoclusters (FeS@BSA nanoclusters) | Anti-Huh7 tumor therapy | [80] | ||

| GYY4137 (donor) | Anti-atherosclerosis treatment | [81] | ||

| Sodium hydrogen sulfide (NaHS) (exogenous donor) | Relief of emphysema and airway inflammation | [82] | ||

| CO2 | Bicarbonate | Accelerated wound healing | [85] | |

| Core–shell hybrid nanoparticles consisting of CaCO3 and MnSiOx (CaCO3@MS nanoparticles) | Anti-4T1 tumor therapy | [86] | ||

| Immunostimulatory CRET nanoparticles (iCRET NPs) | Anti-CT26 tumor therapy | [87] |

4.2. Application of MNs-Mediated Gas Therapy

4.2.1. Cancer

4.2.2. Diabetic Wound

4.2.3. Wound Infection

4.2.4. Other Diseases

| Application | Gas | MN Types | Gas-Producing Components | Condition | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitate rapid separation | CO2 | Dissolving MNs | NaHCO3 | Growth hormone deficiency | [26] |

| CO2 | Dissolving MNs | NaHCO3, citric acid | Long-acting contraception | [28] | |

| H2 | Dissolving MNs | Mg | Chronic wounds | [21] | |

| Enhanced drug penetration | CO2 | Dissolving MNs | K2CO3, citric acid | / | [22] |

| CO2 | Dissolving MNs | NaHCO3, citric acid | Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) | [37] | |

| CO2 | Dissolving MNs | NaHCO3, citric acid | Diabetic | [36] | |

| CO2 | Dissolving MNs | NaHCO3, citric acid | Hypertrophic scar | [38] | |

| CO2 | Dissolving MNs | NaHCO3 | Melanoma | [40] | |

| CO2 | Dissolving MNs | NaHCO3 | Melanoma | [41] | |

| CO2 | Dissolving MNs | NaHCO3 | / | [42] | |

| CO2 | Dissolving MNs | NaHCO3 | Postoperative pain | [43] | |

| CO2 | Coated MNs | NaHCO3 | Diabetic | [44] | |

| H2 | Dissolving MNs | Mg | Melanoma | [47] | |

| Combined therapy | H2 | Dissolving MNs | AB-MSN | Melanoma | [99] |

| H2 | Dissolving MNs | AB-MSN | Diabetic wounds | [123] | |

| H2 | Dissolving MNs | MgH2 | Diabetic wounds | [122] | |

| H2 | Dissolving MNs | E.A. | Psoriasis | [24] | |

| H2 | Dissolving MNs | PDA@ZIF-8@AB | Postoperative pain | [140] | |

| H2 | Dissolving MNs | PtRu/C3N5 | Wound infection | [131] | |

| H2 | Galvanic cell MNs | Mg | Skin photoaging | [143] | |

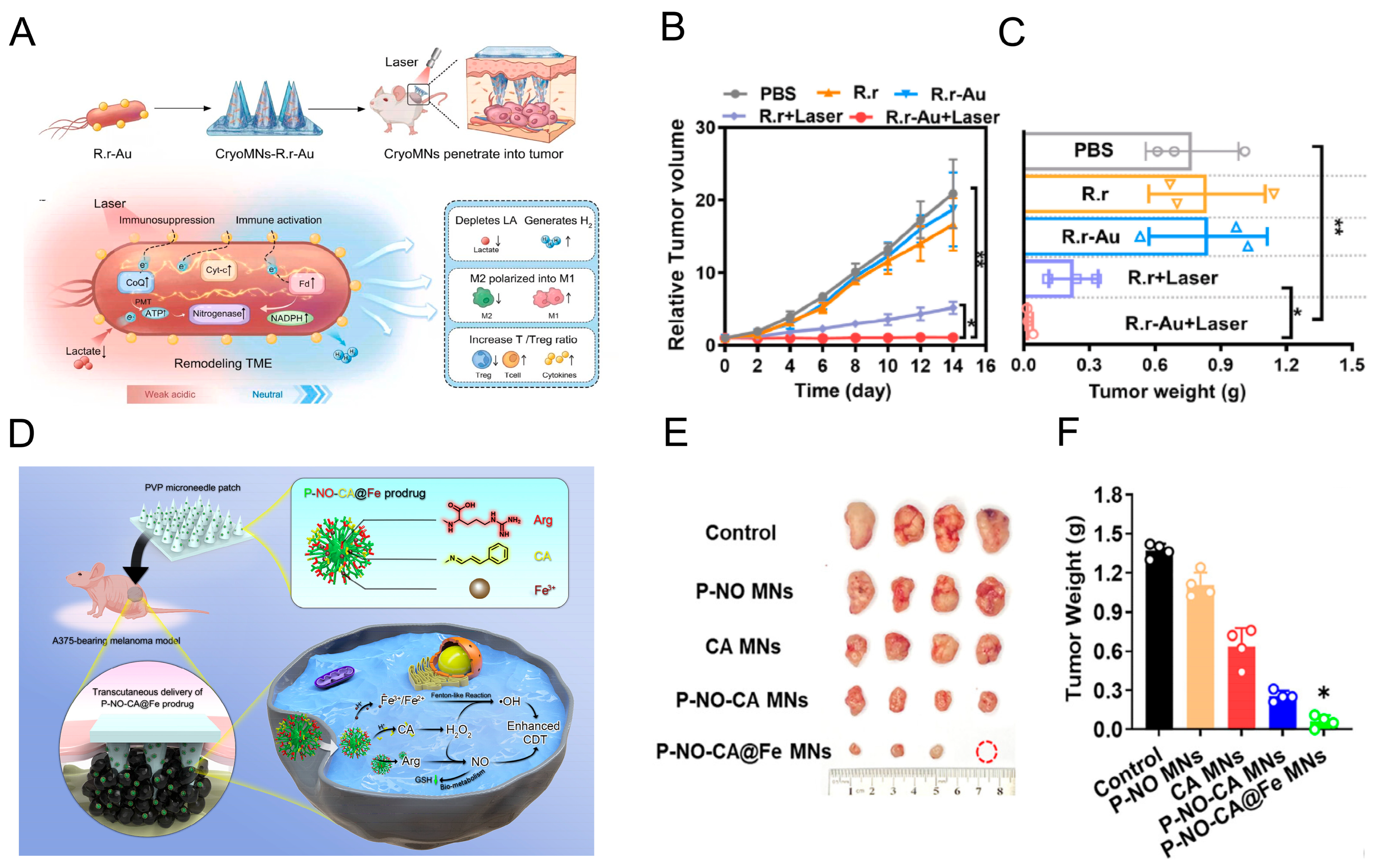

| H2 | Cryomicroneedles | R.r-Au | Melanoma | [100] | |

| NO | Dissolving MNs | P-NO-CA@Fe | Melanoma | [101] | |

| NO | Dissolving MNs | SNAP | Melanoma | [106] | |

| NO | Dissolving MNs | SNP-Fe | Maxillofacial malignant skin tumors | [102] | |

| NO | Dissolving MNs | RE@SA-ConA/SNO | Wound infection | [132] | |

| NO | Hydrogel MNs | mNOGO | TBI | [138] | |

| NO | Hydrogel MNs | CLMS | AMI | [139] | |

| O2 | Hydrogel MNs | Oxygen-carrying protein hemoglobin | Diabetic wounds | [127] | |

| O2 | Hydrogel MNs | Dopamine-functionalized sericin protein (SDA) | Diabetic wounds | [128] | |

| O2 | Hydrogel MNs | Chlorella vulgaris | Diabetic wounds | [129] | |

| O2 | Hydrogel MNs | Chlorella | Diabetic wounds | [130] | |

| O2 | Hydrogel MNs | Calcium peroxide | Diabetic wounds | [125] | |

| O2 | Dissolving MNs | Manganese/Dopamine-enhanced calcium peroxide | Diabetic wounds | [126] | |

| H2S | Dissolving MNs | DATS | Breast cancer | [23] | |

| H2S | Dissolving MNs | Biomineralized nanoenzyme functionalized with Polymyxin B | Diabetic wounds | [121] | |

| CO | Dissolving MNs | TICO | Wound infection | [133] |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramadon, D.; McCrudden, M.T.C.; Courtenay, A.J.; Donnelly, R.F. Enhancement strategies for transdermal drug delivery systems: Current trends and applications. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 758–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.F.; Correia, I.J.; Silva, A.S.; Mano, J.F. Biomaterials for drug delivery patches. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 118, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waghule, T.; Singhvi, G.; Dubey, S.K.; Pandey, M.M.; Gupta, G.; Singh, M.; Dua, K. Microneedles: A smart approach and increasing potential for transdermal drug delivery system. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.X.; Nguyen, C.N. Microneedle-mediated transdermal delivery of biopharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.H.; Jin, S.G. Microneedle for transdermal drug delivery: Current trends and fabrication. J. Pharm. Investig. 2021, 51, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, W.; Ma, Q.; Gao, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liang, Y.; Han, S.; et al. Functional nano-systems for transdermal drug delivery and skin therapy. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 1527–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, F.; Geng, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J. Advanced nanocarrier- and microneedle-based transdermal drug delivery strategies for skin diseases treatment. Theranostics 2022, 12, 3372–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Mittal, A.; Ali, J.; Sahoo, J. Current updates in transdermal therapeutic systems and their role in neurological disorders. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2021, 22, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ita, K. Recent trends in the transdermal delivery of therapeutic agents used for the management of neurodegenerative diseases. J. Drug Target. 2017, 25, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Cao, J.; Fang, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhen, Y.; Wu, F.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Applications and recent advances in transdermal drug delivery systems for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 4417–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Alle, M.; Chakraborty, C.; Kim, J.-C. Strategies for transdermal drug delivery against bone disorders: A preclinical and clinical update. J. Control. Release 2021, 336, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y. Investigation of microemulsion system for transdermal delivery of ligustrazine phosphate. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 5, 1674–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ahad, A.; Aqil, M.; Ali, A. Investigation of antihypertensive activity of carbopol valsartan transdermal gel containing 1,8-cineole. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 64, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedipour, F.; Hosseini, S.A.; Reiner, Ž.; Tedeschi-Reiner, E.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Therapeutic effects of statins: Promising drug for topical and transdermal administration. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 3149–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahad, A.; Raish, M.; Bin Jardan, Y.A.; Al-Mohizea, A.M.; Al-Jenoobi, F.I. Delivery of insulin via skin route for the management of diabetes mellitus: Approaches for breaching the obstacles. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Kahkoska, A.R.; Wang, J.; Buse, J.B.; Gu, Z. Advances in transdermal insulin delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 139, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Mao, W.; Ye, Y.; Kahkoska, A.R.; Buse, J.B.; Langer, R.; Gu, Z. Glucose-responsive insulin patch for the regulation of blood glucose in mice and minipigs. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, L.R.; Harada, L.K.; Silva, E.C.; Campos, W.F.; Moreli, F.C.; Shimamoto, G.; Pereira, J.F.B.; Oliveira, J.M.; Tubino, M.; Vila, M.M.D.C.; et al. Non-invasive transdermal delivery of human insulin using ionic liquids: In vitro studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaghi, M.; Ninan, J.A.; Azimzadeh, M.; Askari, E.; Najafabadi, A.H.; Khademhosseini, A.; Akbari, M. Remote-controlled sensing and drug delivery via 3D-printed hollow microneedles. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2400881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, T. Extensible and swellable hydrogel-forming microneedles for deep point-of-care sampling and drug deployment. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, T.; Yang, F.; Chen, D.; Jia, Z.; Yuan, R.; Du, Z.; Liu, S.; Yu, Y.; Dai, X.; Niu, X.; et al. Synergistically detachable microneedle dressing for programmed treatment of chronic wounds. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, e2102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, B.; Luan, X.; Jiang, L.; Lu, C.; Wu, C.; Pan, X.; Peng, T. State of the art in constructing gas-propelled dissolving microneedles for significantly enhanced drug-loading and delivery efficiency. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Jia, L.; Li, H.; Yang, C.; Yan, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, F.; Qu, F.; Guo, W. An intelligent and soluble microneedle composed of Bi/BiVO4 schottky heterojunction for tumor ct imaging and starvation/gas therapy-promoted synergistic cancer treatment. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, e2303147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Li, Q.; Fang, L.; Cai, X.; Liu, Y.; Duo, Y.; Li, B.; Wu, Z.; Shen, B.; Bai, Y.; et al. Microorganism microneedle micro-engine depth drug delivery. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhang, X.; Nie, M.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y. Photothermal responsive microspheres-triggered separable microneedles for versatile drug delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2110746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Gao, N.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Mei, L.; Zeng, X. Actively separated microneedle patch for sustained-release of growth hormone to treat growth hormone deficiency. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Hu, D.; Chen, Z.; Xu, J.; Xu, R.; Gong, Y.; Fang, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, W. Immunotherapy for type 1 diabetes mellitus by adjuvant-free schistosoma japonicum-egg tip-loaded asymmetric microneedle patch (STAMP). J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Tang, J.; Terry, R.N.; Li, S.; Brunie, A.; Callahan, R.L.; Noel, R.K.; Rodríguez, C.A.; Schwendeman, S.P.; Prausnitz, M.R. Long-acting reversible contraception by effervescent microneedle patch. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw8145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauleth-Ramos, T.; El-Sayed, N.; Fontana, F.; Lobita, M.; Shahbazi, M.-A.; Santos, H.A. Recent approaches for enhancing the performance of dissolving microneedles in drug delivery applications. Mater. Today 2023, 63, 239–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ye, R.; Gong, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, B.; Xu, Y.; Nie, G.; Xie, X.; Jiang, L. Iontophoresis-driven microneedle patch for the active transdermal delivery of vaccine macromolecules. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2023, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, M.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Z. Advances in biomedical systems based on microneedles: Design, fabrication, and application. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 530–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; He, G.; Zhao, H.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Li, W. Enhancing deep-seated melanoma therapy through wearable self-powered microneedle patch. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2311246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, D.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. Topical adhesive spatio-temporal nanosystem co-delivering chlorin e6 and HMGB1 inhibitor glycyrrhizic acid for in situ psoriasis chemo-phototherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 1126–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Li, G.; Chen, W. Ultrasound-activatable and skin-associated minimally invasive microdevices for smart drug delivery and diagnosis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 203, 115133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaneththi, V.R.; Aw, K.; Sharma, M.; Wen, J.; Svirskis, D.; McDaid, A. Controlled transdermal drug delivery using a wireless magnetic microneedle patch: Preclinical device development. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 297, 126708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Yang, C.; Han, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Wang, S.; Cai, R.; Li, H.; et al. Ultrarapid-acting microneedles for immediate delivery of biotherapeutics. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2304582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ren, T.; Wu, W.; Yang, B.; Lu, A.; Pan, K.; Xu, J.; Lu, C.; Quan, G.; Wu, C.; et al. Gas-propelled anti-hair follicle aging microneedle patch for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. J. Control. Release 2025, 379, 636–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Fu, Y.; Yi, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, W.; Shi, C.; Chang, Z.; Yang, B.; Li, S.; Lu, C.; et al. Autonomous drug delivery and scar microenvironment remodeling using micromotor-driven microneedles for hypertrophic scars therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 3738–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellesso, F.; Orban, M.P.; Shirgaonkar, N.; Berardi, E.; Serneels, J.; Neveu, M.-A.; Di Molfetta, D.; Piccapane, F.; Caroppo, R.; Debellis, L.; et al. Targeting the bicarbonate transporter SLC4A4 overcomes immunosuppression and immunotherapy resistance in pancreatic cancer. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 1464–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Wang, B.; Dong, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, S.; Jiang, T.; Zhao, X. Photothermal and acid-responsive fucoidan-CuS bubble pump microneedles for combined CDT/PTT/CT treatment of melanoma. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 40267–40279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Ma, Q.; Su, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, X.; Ge, C.; Kong, F.; et al. Effervescent cannabidiol solid dispersion-doped dissolving microneedles for boosted melanoma therapy via the “TRPV1-NFATc1-ATF3” pathway and tumor microenvironment engineering. Biomater. Res. 2023, 27, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, C.J.; Lin, Y.J.; Hu, Y.C.; Chiang, W.-L.; Chen, K.-J.; Yang, W.-C.; Liu, H.-L.; Fu, C.-C.; Sung, H.-W. Multidrug release based on microneedle arrays filled with pH-responsive PLGA hollow microspheres. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 5156–5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Zeng, Y.; Xiong, B.; Jiang, X.; Jin, Y.; Wang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Li, W.; Peng, M. A pH-responsive core-shell microneedle patch with self-monitoring capability for local long-lasting analgesia. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2314048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Choi, H.J.; Jang, M.; An, S.; Kim, G.M. Smart microneedles with porous polymer layer for glucose-responsive insulin delivery. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Al Mamun, A.; Zaidi, M.B.; Roome, T.; Hasan, A. A calcium peroxide incorporated oxygen releasing chitosan-PVA patch for diabetic wound healing. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Fu, Y.; Wei, F.; Ma, T.; Ren, J.; Xie, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Tao, J.; et al. Microneedle patches with O2 propellant for deeply and fast delivering photosensitizers: Towards improved photodynamic therapy. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2202591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ramirez, M.A.; Soto, F.; Wang, C.; Rueda, R.; Shukla, S.; Silva-Lopez, C.; Kupor, D.; McBride, D.A.; Pokorski, J.K.; Nourhani, A.; et al. Built-In active microneedle patch with enhanced autonomous drug delivery. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1905740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibrian, D.; de la Fuente, H.; Sánchez-Madrid, F. Metabolic pathways that control skin homeostasis and inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opoku-Damoah, Y.; Zhang, R.; Ta, H.T.; Xu, Z.P. Therapeutic gas-releasing nanomedicines with controlled release: Advances and perspectives. Exploration 2022, 2, 20210181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q. Precision gas therapy using intelligent nanomedicine. Biomater. Sci. 2017, 5, 2226–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Liang, B.; Hu, A.; Zhou, H.; Jia, C.; Aji, A.; Chen, Q.; Ma, Y.; Cui, W.; Jiang, L.; et al. Engineered biomimetic cancer cell membrane nanosystems trigger gas-immunometabolic therapy for spinal-metastasized tumors. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2412655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Zhong, J.; Pan, W.; Li, Y.; Li, N.; Tang, B. Gas-mediated cancer therapy: Advances in delivery strategies and therapeutic mechanisms. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 18535–18558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jia, H.; Ji, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Dai, C.; Ding, D.; Tang, B.Z.; Feng, G. Dual-mode reactive oxygen species-stimulated carbon monoxide release for synergistic photodynamic and gas tumor therapy. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 31286–31299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, T.; He, Q. Strategies for engineering advanced nanomedicines for gas therapy of cancer. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1485–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, M.; Yan, Y.; Li, P.; Huang, W. Flexible monitoring, diagnosis, and therapy by microneedles with versatile materials and devices toward multifunction scope. Research 2023, 6, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Zhao, J.N.; Bao, N.R. Hydrogen applications: Advances in the field of medical therapy. Med. Gas Res. 2023, 13, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Liang, S.; Yang, L.; Li, F.; Liu, B.; Yang, C.; Yang, Z.; Bian, Y.; Ma, P.; Cheng, Z.; et al. Rational design of platinum-bismuth sulfide schottky heterostructure for sonocatalysis-mediated hydrogen therapy. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2209589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wu, F.; Hu, Y.H. Microfactories for intracellular locally generated hydrogen therapy: Advanced materials, challenges, and opportunities. ChemPlusChem 2020, 85, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Z.; Zhao, P.; Wang, Z.; Jin, Z.; Chen, L.; Su, B.-L.; He, Q. Acid-responsive H2-releasing Fe nanoparticles for safe and effective cancer therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 2759–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, F.; Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Yang, N.; Cheng, L.; Huang, P.; Wang, C.; Chen, Q.; Ni, C.; Liu, Z. Nanoscale CaH2 materials for synergistic hydrogen-immune cancer therapy. Chem 2022, 8, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fan, M.; Yang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zeng, L.; Wu, X.; Xu, Q.; Su, C.; He, Q. Homogeneous carbon/potassium-incorporation strategy for synthesizing red polymeric carbon nitride capable of near-infrared photocatalytic H2 production. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, K.; Men, F.; Wang, W.C.; Zhou, Y.-Q.; Zhang, H.-W.; Ye, D.-W. Carbon monoxide and its controlled release: Therapeutic application, detection, and development of carbon monoxide releasing molecules (CORMs). J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 2611–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, C.; Chen, H.; Kwok, R.T.K.; Zhang, P.; Tang, B.Z.; Cai, L.; Gong, P. H2O2-responsive NIR-II AIE nanobomb for carbon monoxide boosting low-temperature photothermal therapy. Angew. Chem. 2022, 61, e202207213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, L.; Fan, X.; Wan, B.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.; He, Z.; et al. Gas therapy potentiates aggregation-induced emission luminogen-based photoimmunotherapy of poorly immunogenic tumors through cGAS-STING pathway activation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Zhuang, W.; Ding, J.; Zhang, C.; Gao, H.; Pang, D.-W.; Pu, K.; Xie, H.-Y. Molecularly engineered macrophage-derived exosomes with inflammation tropism and intrinsic heme biosynthesis for atherosclerosis treatment. Angew. Chem. 2020, 59, 4068–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, G.; Shen, H.; Li, J.; Chen, G. Mechanisms of nitric oxide in spinal cord injury. Med. Gas Res. 2024, 14, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Zheng, G.; Li, G.; Chen, J.; Qi, L.; Luo, Y.; Ke, T.; Xiong, J.; Ji, X. Ultrasound-responsive nanoparticles for nitric oxide release to inhibit the growth of breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhan, M.; Li, W.; Chu, C.; Xing, D.; Lu, S.; Hu, X. Photoacoustic cavitation-ignited reactive oxygen species to amplify peroxynitrite burst by photosensitization-free polymeric nanocapsules. Angew. Chem. 2021, 60, 4720–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.W.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.H.; Xu, L.; Li, C.-X.; Li, B.; Fan, J.-X.; Cheng, S.-X.; Zhang, X.-Z. Optically-controlled bacterial metabolite for cancer therapy. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Fan, Y.; Ye, W.; Tian, L.; Niu, S.; Ming, W.; Zhao, J.; Ren, L. Near-infrared light triggered photodynamic and nitric oxide synergistic antibacterial nanocomposite membrane. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 128049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, T.; Chen, J.; Duan, X.; Guo, B. Photothermal antibacterial antioxidant conductive self-healing hydrogel with nitric oxide release accelerates diabetic wound healing. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 266, 110985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Sen, S. Therapeutic effects of hyperbaric oxygen: Integrated review. Med. Gas Res. 2021, 11, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Sun, Z.; Wu, J.; Ruan, J.; Zhao, P.; Liu, K.; Zhao, C.; Sheng, J.; Liang, T.; Chen, D. Nanoparticle-stabilized oxygen microcapsules prepared by interfacial polymerization for enhanced oxygen delivery. Angew. Chem. 2021, 60, 9284–9289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Song, J.; Tian, R.; Yang, Z.; Yu, G.; Lin, L.; Zhang, G.; Fan, W.; Zhang, F.; Niu, G.; et al. Activatable singlet oxygen generation from lipid hydroperoxide nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Angew. Chem. 2017, 56, 6492–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Bai, H.; Liu, L.; Lv, F.; Ren, X.; Wang, S. Luminescent, oxygen-supplying, hemoglobin-linked conjugated polymer nanoparticles for photodynamic therapy. Angew. Chem. 2019, 58, 10660–10665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Cheng, Y.; Tian, J.; Yang, P.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wu, J. Dissolved oxygen from microalgae-gel patch promotes chronic wound healing in diabetes. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.; Niu, H.; Liu, Z.; Dang, Y.; Shen, J.; Zayed, M.; Ma, L.; Guan, J. Sustained oxygenation accelerates diabetic wound healing by promoting epithelialization and angiogenesis and decreasing inflammation. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabj0153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.C.; Jin, P.R.; Chu, L.A.; Hsu, F.-F.; Wang, M.-R.; Chang, C.-C.; Chiou, S.-J.; Qiu, J.T.; Gao, D.-Y.; Lin, C.-C.; et al. Delivery of nitric oxide with a nanocarrier promotes tumour vessel normalization and potentiates anti-cancer therapies. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 1160–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovinazzo, D.; Bursac, B.; Sbodio, J.I.; Nalluru, S.; Vignane, T.; Snowman, A.M.; Albacarys, L.M.; Sedlak, T.W.; Torregrossa, R.; Whiteman, M.; et al. Hydrogen sulfide is neuroprotective in Alzheimer’s disease by sulfhydrating GSK3β and inhibiting Tau hyperphosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2017225118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Cen, D.; Ren, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Han, G.; Cai, X. FeS@BSA Nanoclusters to Enable H2S-Amplified ROS-Based Therapy with MRI Guidance. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1903512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Gu, Y.; Wen, M.; Zhao, S.; Wang, W.; Ma, Y.; Meng, G.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; et al. Hydrogen sulfide induces Keap1 S-sulfhydration and suppresses diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis via Nrf2 activation. Diabetes 2016, 65, 3171–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liao, S.; Pan, Z.; Jiang, S.; Fan, J.; Yu, S.; Xue, L.; Yang, J.; Ma, S.; Liu, T.; et al. Hydrogen sulfide alleviates particulate matter-induced emphysema and airway inflammation by suppressing ferroptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 186, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratano, S.; Jovanovic, B.; Ouabo, E.C. Effects of the percutaneous carbon dioxide therapy on post-surgical and post-traumatic hematoma, edema and pain. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2023, 13, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, P.; Yang, K.; Xu, Q.; Qin, G.; Zhu, Q.; Qian, Y.; Yao, W. Mechanisms and application of gas-based anticancer therapies. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, G.; Zhou, N.; Gao, Y.; Du, S.; Du, H.; Tao, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J. On-demand release of CO2 from photothermal hydrogels for accelerating skin wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 403, 126353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Zhang, T.; Fu, Y.; Han, G.; Li, X. CaCO3-MnSiOx hybrid particles to enable CO2-mediated combinational tumor therapy. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 8281–8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Yoon, B.; Song, S.H.; Um, W.; Song, Y.; Lee, J.; Gil You, D.; An, J.Y.; Park, J.H. Chemiluminescence resonance energy transfer-based immunostimulatory nanoparticles for sonoimmunotherapy. Biomaterials 2022, 283, 121466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, C.; Rumgay, H.; Vignat, J.; Ginsburg, O.; Nolte, E.; Bray, F.; Soerjomataram, I. Quantitative estimates of preventable and treatable deaths from 36 cancers worldwide: A population-based study. The Lancet. Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1700–e1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, P.; Xu, Y.; Yan, J.; Liu, Z.; Lau, W.B.; Lau, B.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wei, Y.; et al. Surgical stress and cancer progression: The twisted tango. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Guan, B.; Xia, H.; Zheng, R.; Xu, B. Particle radiotherapy in the era of radioimmunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2023, 567, 216268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Awasthi, R.; Malviya, R. Bioinspired microrobots: Opportunities and challenges in targeted cancer therapy. J. Control. Release 2023, 354, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.; Yuan, X.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, B.; Ding, G.; Bai, J. Recent progress in nanocarrier-based drug delivery systems for antitumour metastasis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 252, 115259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, R.; Yin, J.; Liu, Y.; Xue, J. FLASH radiotherapy: A new milestone in the field of cancer radiotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2024, 587, 216651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shi, M.; Ren, Y.; Xu, H.; Weng, S.; Ning, W.; Ge, X.; Liu, L.; Guo, C.; Duo, M.; et al. Recent advances and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 in cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waarts, M.R.; Stonestrom, A.J.; Park, Y.C.; Levine, R.L. Targeting mutations in cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e154943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xu, B.; Li, S.; Wu, Q.; Lu, M.; Han, A.; Liu, H. A photoresponsive nanozyme for synergistic catalytic therapy and dual phototherapy. Small 2021, 17, e2007090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Meng, Z.; Exner, A.A.; Cai, X.; Xie, X.; Hu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Y. Biodegradable cascade nanocatalysts enable tumor-microenvironment remodeling for controllable CO release and targeted/synergistic cancer nanotherapy. Biomaterials 2021, 276, 121001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Tiemuer, A.; Yao, X.; Zuo, M.; Wang, H.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X. Mitochondria-specific near-infrared photoactivation of peroxynitrite upconversion luminescent nanogenerator for precision cancer gas therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Li, G.; Yuan, J.; Jing, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Li, G.; Xie, G.; et al. A smart silk-based microneedle for cancer stem cell synergistic immunity/hydrogen therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2206406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Yin, T.; Zeng, C.; Pan, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Zheng, M.; Cai, L. Cryomicroneedle delivery of nanogold-engineered rhodospirillum rubrum for photochemical transformation and tumor optical biotherapy. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 37, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Jia, F.; Fu, J.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Jin, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ji, J. Enhanced transcutaneous chemodynamic therapy for melanoma treatment through cascaded fenton-like reactions and nitric oxide delivery. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 15713–15723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mei, Y.; Sina, A.; Zou, R.; Niu, L. A novel multifunctional microneedle patch for synergistic photothermal- gas therapy against maxillofacial malignant melanoma and associated skin defects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Xu, Z.; Wang, S.; Cai, N.; He, M.; Xiao, Y.; Ding, Y.; Sun, M.; et al. Local exosome inhibition potentiates mild photothermal immunotherapy against breast cancer. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2406328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Duan, Q.Y.; Wu, F.G. Low-temperature photothermal therapy: Strategies and applications. Research 2021, 2021, 9816594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Feng, L.; He, F.; Gai, S.; Xie, Y.; Yang, P. “Electron transport chain interference” strategy of amplified mild-photothermal therapy and defect-engineered multi-enzymatic activities for synergistic tumor-personalized suppression. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 9488–9507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Tao, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, A.; Xiang, G.; Li, S.; Jiang, T.; Zhao, X. Partitioned microneedle patch based on NO release and HSP inhibition for mPTT/GT combination treatment of melanoma. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 49104–49113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Wen, Y.; Xiong, L.; Yang, T.; Zhao, P.; Tan, L.; Wang, T.; Qian, Z.; Su, B.-L.; He, Q. Intratumoral H2O2-triggered release of CO from a metal carbonyl-based nanomedicine for efficient CO therapy. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 5557–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Yu, W.; Qian, X.; Wang, Y.; Ji, J. A photocatalytic carbon monoxide-generating effervescent microneedle patch for improved transdermal chemotherapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 5406–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, G.; Wang, B.; Zhang, W.; Dong, Y.; Tao, J.; Zhang, A.; Chen, R.; Jiang, T.; Zhao, X. A Zn-MOF-GOx-based cascade nanoreactor promotes diabetic infected wound healing by NO release and microenvironment regulation. Acta Biomater. 2024, 182, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Peng, M.; He, W.; Hu, X.; Xiao, J.; Shi, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Microenvironment-adaptive nanodecoy synergizes bacterial eradication, inflammation alleviation, and immunomodulation in promoting biofilm-associated diabetic chronic wound healing cascade. Aggregate 2024, 5, e640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhao, B.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, Q.; Gao, H.; Feng, Q.; Cao, X. Microenvironment responsive nanocomposite hydrogel with NIR photothermal therapy, vascularization and anti-inflammation for diabetic infected wound healing. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 26, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, K.; Wei, W.; Dai, H. A multifunctional hydrogel with photothermal antibacterial and antioxidant activity for smart monitoring and promotion of diabetic wound healing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F.; Huang, H.; Xiao, S.; Xia, Z.; Zheng, Y. Netrin-1 co-cross-linked hydrogel accelerates diabetic wound healing in situ by modulating macrophage heterogeneity and promoting angiogenesis. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 39, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Qin, S.; Li, M.; Shi, L.; Zhou, C.; Liao, T.; Li, C.; Lv, Q.; et al. Nickel-based metal-organic frameworks promote diabetic wound healing via scavenging reactive oxygen species and enhancing angiogenesis. Small 2024, 20, e2305076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Lu, H.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, D.; Zeng, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, X.; Cai, X. H2S-releasing versatile montmorillonite nanoformulation trilogically renovates the gut microenvironment for inflammatory bowel disease modulation. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2308092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Lv, X.; Li, H.; Yang, D.; Wang, W.; Hu, Y.; Liu, L.; Dong, X.; Cai, Y. Environment-triggered nanoagent with programmed gas release performance for accelerating diabetic infected wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 147645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Luo, L.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, M.; Pan, H.; Shangguan, J.; Yao, Q.; Xu, S.; Xu, H. In situ hydrogel capturing nitric oxide microbubbles accelerates the healing of diabetic foot. J. Control. Release 2022, 350, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Rong, F.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Xu, F.; Chen, J.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Glucose oxidase driven hydrogen sulfide-releasing nanocascade for diabetic infection treatment. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 6610–6618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, D.; Chen, J.; Shen, T.; Jin, T.; Zeng, B.; Li, L.; Yang, C.; Mu, Z.; Deng, H.; et al. An all-in-one CO gas therapy-based hydrogel dressing with sustained insulin release, anti-oxidative stress, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory capabilities for infected diabetic wounds. Acta Biomater. 2022, 146, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Wang, Y.; Chi, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y. Porous MOF microneedle array patch with photothermal responsive nitric oxide delivery for wound healing. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2103449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Li, R.; Chai, X.; Cai, X.; Zheng, K.; Wang, Y.; Fan, K.; Guo, Z.; Guo, J.; Jiang, W. Catalase-templated nanozyme-loaded microneedles integrated with polymyxin B for immunoregulation and antibacterial activity in diabetic wounds. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 667, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Wu, J.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Yao, T.; Liu, C.; Gong, Y.; Wang, M.; Ji, G.; Huang, P.; et al. Intelligent microneedle patch with prolonged local release of hydrogen and magnesium ions for diabetic wound healing. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 24, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Xia, Y.; Tang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, S.; Chen, J.; Xu, Z.; Li, L.; Qiu, J.; Wang, P.; et al. Self-responsive H2-releasing microneedle patch temporally adapts to the sequential microenvironment requirements for optimal diabetic wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Yin, T.; Jiang, J.; He, Y.; Xiang, T.; Zhou, S. Wound microenvironment self-adaptive hydrogel with efficient angiogenesis for promoting diabetic wound healing. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 20, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Zhong, X.; Dai, M.; Feng, X.; Tang, C.; Cao, L.; Liu, L. Antibacterial microneedle patch releases oxygen to enhance diabetic wound healing. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 24, 100945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, J.; Xie, Z.; Yan, L.; Ye, C.; Hou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lu, X.; Xie, C. Oxygen-propelled dual-modular microneedles with dopamine-enhanced RNA delivery for regulating each stage of diabetic wounds. Small 2024, 20, e2404538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Liu, Y.; Sun, L.; Sun, L.; Zhao, Y. Black phosphorus-loaded separable microneedles as responsive oxygen delivery carriers for wound healing. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 5901–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Qin, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Deng, Y.; Liu, M.; Chen, W.; Wang, Z.; et al. Silk sericin-based ROS-responsive oxygen generating microneedle platform promotes angiogenesis and decreases inflammation for scarless diabetic wound healing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2404461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, E.; Xiao, T.; Tan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K.; Ou, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; et al. Separable microneedles with photosynthesis-driven oxygen manufactory for diabetic wound healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 7725–7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Rao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Yan, F. Chlorella-loaded antibacterial microneedles for microacupuncture oxygen therapy of diabetic bacterial infected wounds. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2307585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liang, M.; Bai, Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, D.; Sui, N.; Zhu, Z. Piezo-augmented and photocatalytic nanozyme integrated microneedles for antibacterial and anti-inflammatory combination therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2210850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Ruan, Q.; Li, W. Multifunctional microneedle patches loaded with engineered nitric oxide-releasing nanocarriers for targeted and synergistic chronic wound therapy. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2413108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Kang, X.; Zhang, P.; Chen, T.; Li, Y.; Wu, H.; Qi, J.; Li, X.; Bing, W.; et al. Bacterial microenvironment-responsive microneedle patches for real-time monitoring and synergistic eradication of infection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2414834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Bai, L.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Cui, W.; Hao, Y.; Yang, X. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory injectable hydrogel microspheres for in situ treatment of tendinopathy. Regen. Biomater. 2024, 11, rbae007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; He, G.; Guo, Y.; Tang, H.; Shi, Y.; Bian, X.; Zhu, M.; Kang, X.; Zhou, M.; Lyu, J.; et al. Exosomes from tendon stem cells promote injury tendon healing through balancing synthesis and degradation of the tendon extracellular matrix. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 5475–5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, R.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Sun, K.; Sun, Z.; Lv, Z.; Xu, J.; et al. Nitric oxide nanomotor driving exosomes-loaded microneedles for achilles tendinopathy healing. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 13339–13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Hang, D.; Jin, J.; Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, H. Targeting pyroptosis with nanoparticles to alleviate neuroinflammatory for preventing secondary damage following traumatic brain injury. Sci. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, M.R.; Lin, Y.H.; Zhao, W.J.; Liu, H.; Hsu, R.; Chou, T.; Lu, T.; Lee, I.; Liao, L.; Chiou, S.; et al. In situ forming of nitric oxide and electric stimulus for nerve therapy by wireless chargeable gold yarn-dynamos. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2303566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Cao, S.; Zhang, T.; Lv, F.; Zhai, M.; Bai, D.; Zhao, M.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X. Reactive oxide species and ultrasound dual-responsive bilayer microneedle array for in-situ sequential therapy of acute myocardial infarction. Biomater. Adv. 2024, 162, 213917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Jiang, X.; Xiong, B.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Li, B.; Peng, M.; Li, W. Sustained-release photothermal microneedles for postoperative incisional analgesia and wound healing via hydrogen therapy. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e03698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, T.W.; Watson, R.E.B.; Langton, A.K. Skin ageing and topical rejuvenation strategies. Br. J. Dermatol. 2023, 189, i17–i23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, C.P.; Xia, J.; Costa, C.S.; Gemperli, R.; Tatini, M.D.; Bulsara, M.K.; Riera, R. Botulinum toxin type a for facial wrinkles. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 7, CD011301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Jia, Q.; Lin, X.; Shi, J.; Gong, W.; Shen, K.; Liu, B.; Sun, L.; Fan, Z. Galvanic cell bipolar microneedle patches for reversing photoaging wrinkles. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2500552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Albakr, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, A.; Chen, W.; Shao, T.; Zhu, L.; Yuan, H.; Yang, G.; et al. Microneedle-enabled therapeutics delivery and biosensing in clinical trials. J. Control. Release 2023, 360, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, Z.; Zhou, T.; Li, H.; Zeng, J.J.X.L.; Fu, Y.; Lu, C.; Peng, T.; Wu, C.; Quan, G. Microneedle Mediated Gas Delivery for Rapid Separation, Enhanced Drug Penetration, and Combined Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121576

Zheng Z, Zhou T, Li H, Zeng JJXL, Fu Y, Lu C, Peng T, Wu C, Quan G. Microneedle Mediated Gas Delivery for Rapid Separation, Enhanced Drug Penetration, and Combined Therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121576

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Ziyang, Ting Zhou, Hongluo Li, Jade Jillian Xian Lan Zeng, Yanping Fu, Chao Lu, Tingting Peng, Chuanbin Wu, and Guilan Quan. 2025. "Microneedle Mediated Gas Delivery for Rapid Separation, Enhanced Drug Penetration, and Combined Therapy" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121576

APA StyleZheng, Z., Zhou, T., Li, H., Zeng, J. J. X. L., Fu, Y., Lu, C., Peng, T., Wu, C., & Quan, G. (2025). Microneedle Mediated Gas Delivery for Rapid Separation, Enhanced Drug Penetration, and Combined Therapy. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121576