Abstract

The first systematic chemical investigation on Sinularia mollis resulted in the isolation and identification of 36 seven-membered cembranolides, including 14 new compounds named sinumollolides A–N (1–14) and 22 known analogs (15–36) by HSQC-based small molecule accurate recognition technology (SMART). Their structures were characterized by spectroscopic methods (1D/2D NMR and UV), HRESIMS, quantum chemical calculations (DP4+ analysis and ECD calculations), and X-ray diffraction analysis. In zebrafish assays, compounds 1, 2, 4, and 5 exhibited anti-inflammatory activity at 20 μM by inhibiting the number of macrophages around the neuromasts, with inhibition rates ranging from 30.4% to 45.6%. Moreover, the two most bioactive and less toxic compounds, 1 and 5, featuring a 14-membered macrocyclic lactone scaffold with several hydroxyl groups and a seven-membered α, β-unsaturated lactone moiety, can inhibit inflammation by suppressing the secretion of inflammatory cytokines at 10 μM in LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells.

1. Introduction

Soft corals of the genus Sinularia (family Alcyoniidae), widely distribute from the waters of East Africa to the Western Pacific, comprise approximately 150 species and over 70 of these species have been chemically investigated [1]. Diterpenes of the cembrane type are some of the most frequent secondary metabolites and most structurally diverse class from various Sinularia species [2]. The cembrane-type diterpenes feature a core 14-membered carbocyclic skeleton, typically featuring an isopropyl group at C-1 and three methyl groups at the C-4, C-8, and C-12 positions, and are categorized into several subtypes, such as isopropyl cembranes, isopropenyl cembranes, and cembranolides by enzymatic processes [3,4]. Research on cembranes has garnered considerable attention due to the wide range of biological activities, including anti-inflammatory activity [5,6], anti-cancer activity [7], cytotoxic activity [8], anti-fouling activity [9], antioxidant activity [10], and anti-hepatitis B virus activity [11].

Particularly, in those subtypes of cembranes, cembranolides are a series of diverse and complex cembrane-type diterpenoids with a typical 14-membered carbocyclic skeleton fused with a five-, six-, or seven-membered lactone moiety bearing either an unsaturation or an exo-double bond, and they demonstrate numerous biological activities, especially anti-inflammatory activities [12]. Notably, extensive research on five-membered cembranolides has illustrated key anti-inflammatory functional groups like the 3,4-epoxy functionality, β-hydroperoxyl group at C-7, the acetoxy group at C-13, and the acetoxy group at C-18 [2] For instance, five-membered cembranolide sinularolide F showed potential anti-inflammatory activities against LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells [13]. While six- and seven-membered cembranolides have been reported to exhibit anti-inflammatory activity, research on them remains relatively insufficient; only no more than 20 six- and seven-membered cembranolides have been reported to exhibit anti-inflammatory activity in previous studies [2]. For example, flexibilin D, a six-membered cembranolide, was found to reduce the levels of iNOS and COX-2 to 19.27 ± 2.72% and 30.08 ± 9.07% at 20 μM, respectively [14]. Seven-membered cembranolide sinusiaeolide A showed significant inhibitory effects on IL-1β and IL-6 in RAW 264.7 cells [15]. Recent studies on the structure–activity relationship (SAR) of seven-membered cembranolides have indicated that a seven-membered lactone moiety at C-1 is essential for their anti-inflammatory activity [16,17]. The compounds, 11-epi-sinulariolide acetate and 5-dehydrosinulariolide, can inhibit inflammation by suppressing NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, and reduce the secretion of inflammatory cytokines [17]. Although five-membered cembranolides have been reported to exhibit anti-inflammatory activity, studies on six- and seven-membered cembranolides and their structure–activity relationships remain relatively limited. Therefore, we employed the SMART technique to guide the isolation of six- and seven-membered cembranolides, aiming to discover anti-inflammatory cembranolide compounds and analyze their structure–activity relationships, thereby providing references for subsequent research.

SMART, the artificial intelligence tool, utilizes a Siamese architecture based on convolutional neural networks and employs Squeeze-Net to map 1H-13C HSQC spectra into a 180-dimensional embedding space. The algorithm was trained on 53,076 HSQC spectra of natural products, including 25,434 experimental and 27,642 predicted spectra, enabling structural annotation of unknown compounds. Compared to conventional methods, SMART-guided screening and isolation significantly shorten experimental cycles and enable targeted isolation of known structures. The entire workflow, from NMR data acquisition to structural prediction, is completed within 30 min, with structural prediction taking only about 8 s [18]. This tool facilitates the rapid mining of targeted compounds, making it invaluable for screening and prioritizing samples [19,20,21].

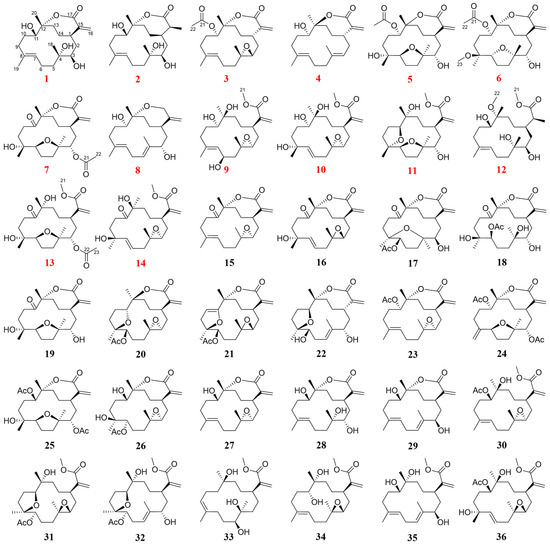

Herein, to streamline the isolation process and achieve the targeted isolation of seven-membered cembranolides, the soft coral S. mollis collected from the South China Sea was subjected to its first chemical investigation using an HSQC-based SMART-guided strategy. A total of 36 cembrane-type diterpenoids were isolated and structurally identified, including 22 seven-membered cembranolides and 14 related analogs (Figure 1). Furthermore, we evaluated their anti-inflammatory activities using zebrafish assays, and we elucidated their potential anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-induced BV-2 microglial cells.

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds 1−36 (red numbers represent new compounds).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. SMART-Guided Isolation

The methanolic extract of S. mollis was fractionated into 14 primary fractions (Frs. 1–14). These fractions were subjected to HSQC analysis, and the resulting data were uploaded to the SMART platform to assess their chemical profiles. The analysis revealed that Frs. 6, 7, 9, 10, and 13 were correlated with cembranolides. Consequently, five fractions were prioritized for further chromatographic separation, leading to the successful isolation of 23 cembranolides, one cembranoid with a seven-membered ether ring, and 12 related analogs. In contrast to traditional separation strategies that necessitate the extensive screening of every fraction, the SMART method rapidly identified five specific fractions rich in seven-membered cembranolides from the fourteen primary fractions. By offering accurate structural predictions, this approach significantly minimized redundancy and effectively guided the subsequent chromatographic separation process.

2.2. Structure Elucidation

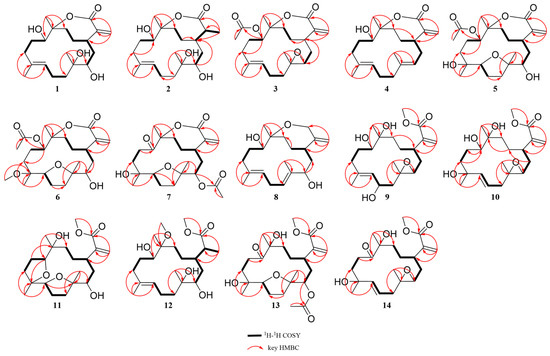

Sinumollolide A (1) had a molecular formula of C20H32O5, determined by the HRESIMS [M + H]+ ion at m/z 353.2321 (calcd for C20H33O5, m/z 353.2323), and it showed five degrees of unsaturation. The 1H NMR (Table 1) spectrum showed the presence of three olefinic protons at δH 6.34 (1H, s, H-16a), δH 5.85 (1H, s, H-16b), and δH 5.09 (1H, d, H-7); two oxygenated protons at δH 4.16 (1H, d, H-11) and δH 3.27 (1H, d, H-3); and three methyl groups at δH 1.29 (3H, s, H-20), δH 1.49 (3H, s, H-19), and δH 1.21 (3H, s, H-18). The 13C NMR (Table 2) and HSQC spectral data revealed the presence of 20 carbon resonances, divided into five non-protonated carbons (δC 172.0, 143.6, 136.2, 89.4, and 75.9), four methine carbons (δC 128.7, 74.0, 68.7, and 38.5), eight methylene carbons (δC 126.0, 39.8, 37.8, 37.2, 32.8, 31.3, 29.1, and 23.4), and three methyl carbons (δC 24.1, 23.3, and 15.8). The presence of two double bonds in 1 was evident from the 1H NMR signals at δH 5.09 and δH 6.34, 5.85 (H-16a/b), as well as the 13C NMR signals at δC 136.2 (C-8), 128.7 (C-7), 143.6 (C-15), and 126.0 (C-16). The HMBC correlations (Figure 2) from H-16 to C-1, C-15, and C-17; from H-20 to C-13, C-12, and C-11; from H-19 to C-7, C-8, and C-9; and from H-18 to C-3, C-4, and C-5 combined with the 1H–1H COSY correlations: H-3/H-2/H-1/H-14/H-13, H-9/H-10/H-11, and H-5/H-6/H-7 established a cembrane skeleton. Three of the five degrees of unsaturation were accounted for by two olefinic bonds and one ester carbonyl group (δC 172.0, C-17), indicating that 1 must be a tricyclic compound. The α, β-unsaturated lactone substructure was confirmed by the HMBC correlations of H-16a/b to C-1, C-15, and C-17 combined with the molecular formula. Additionally, the resonance of C-12 at δC 89.4 (oxygenated quaternary carbon) indicated that 1 was a cembranolide. Thus, the planar structure of 1 was established (Figure 1).

Table 1.

1H NMR spectroscopic data for compounds 1, 2, and 5 in CD3OD and 3, 4, 6, and 7 in CDCl3.

Table 2.

13C NMR spectroscopic data for compounds 1, 2, and 5 in CD3OD, 3, 4, 6–12, and 14 in CDCl3, and 13 in DMSO-d6.

Figure 2.

Key 1H-1H COSY and HMBC correlations of 1–14.

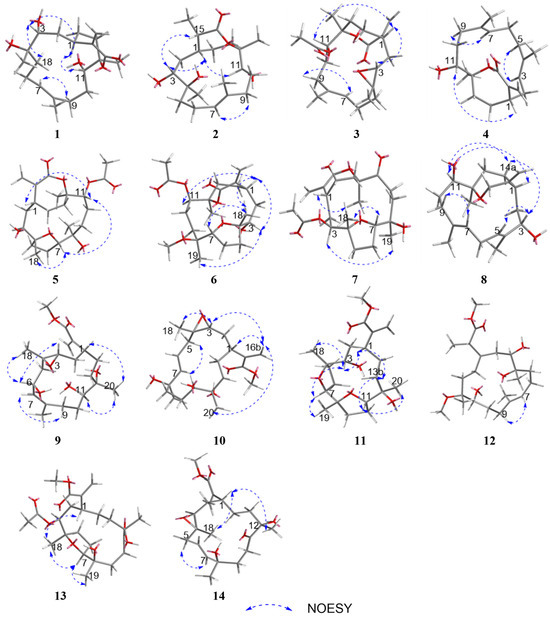

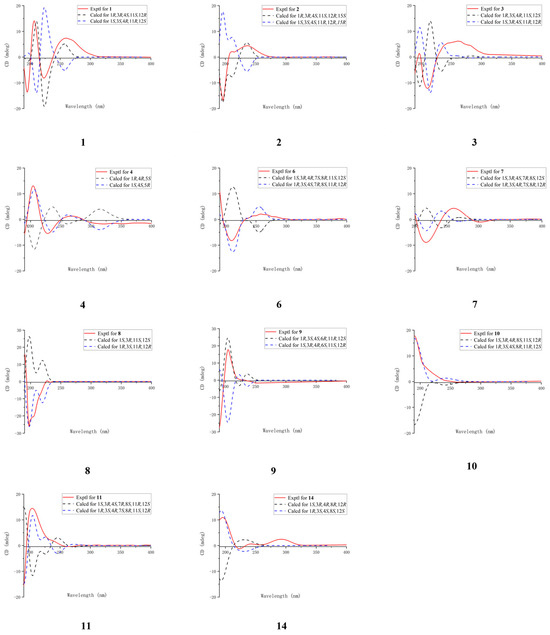

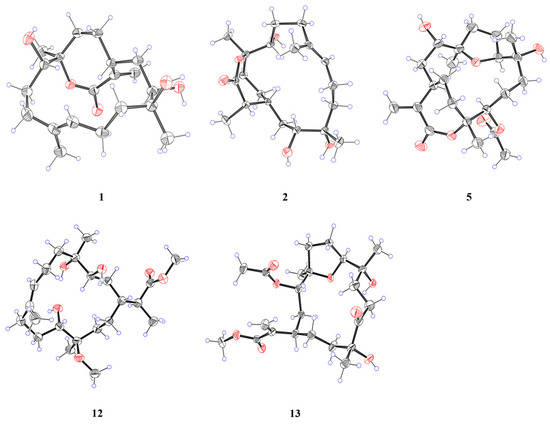

The configuration of the double bond was assigned as E based on the NOESY correlations between H-9b and H-7 (Figure 3). The NOESY correlations of H-1/H-11, H-3/H-18, and H-3/H-1 implied that H-1, H-3, H-11, and H-18 were on the same side of the molecule. To confirm the holistic relative stereochemistry of 1, the GIAO method was employed at the PCM/B3LYP/6-311+G (d, p) level was employed to calculate the 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts for two candidate configurations: 1a (1R*, 3R*, 4S*, 11S*, 12R*) and 1b (1R*, 3R*, 4S*, 11S*, 12S*). The DP4+ probability analyses were performed, which indicated the 1a configurations. Furthermore, the absolute configuration of 1R, 3R, 4S, 11S, 12R was suggested by electronic circular dichroism (ECD) calculations performed using the time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) method at the RB3LYP/DGDZVP level (Figure 4). The absolute configuration of 1 was further confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis as 1R, 3R, 4S, 11S, 12R. (Figure 5). These results show that the application of DP4+ is reliable for the stereochemical elucidation of most compounds.

Figure 3.

Key NOESY correlations of 1–14.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the experimental and calculated ECD spectra of compounds 1−4, 6−11, and 14.

Figure 5.

X-ray crystal structures of 1, 2, 5, 12, and 13.

Analysis of the 1D NMR and 2D NMR (Table 1 and Table 2 and Figure 2) data, along with UV and HRESIMS, revealed that sinumollolide B (2) possesses the same carbon skeleton as 1. A significant difference between 1 and 2 was the reduced double bond at Δ15,16, which was further confirmed by the HMBC (Figure 2) correlations from H-16 to C-1, C-15, and C-17, as well as the 1H−1H COSY correlations of H-16/H-15/H-1. The NOESY (Figure 3) correlations of H-9/H-7, H-3/H-1/H-15, and H-11/H-1 indicated the 8E, 1R*, 3R*, 11S*, 15S* configuration, but the chirality of C-4 and C-12 could not be elucidated from NOESY data. Accordingly, NMR shifts and DP4+ probability analysis were calculated for four possible relative configurations, 2a (1R*, 3R*, 4R*, 11S*, 12R*, 15S*), 2b (1R*, 3R*, 4R*, 11S*, 12S*, 15S*), 2c (1R*, 3R*, 4S*, 11S*, 12R*, 15S*), and 2d (1R*, 3R*, 4S*, 11S*, 12S*, 15S*), and the results showed that 2c was the best fit. The absolute configuration of 2 was determined as 1R, 3R, 4S, 11S, 12R, 15S by ECD calculations (Figure 4) and single crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 5).

The 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 1 and Table 2) displayed close similarity between sinumollolide C (3) and 1. The most pronounced differences were the presence of an acetyl group in 3 at C-11 and an oxygen bridge between C-3 and C-4, as verified by HMBC correlations from H-22 to C-21, from H-11 to C-21, and the key chemical shift observed for C-4 and C-3 in comparison with the known compound 15. In the NOESY (Figure 3) spectrum of 3, the E-configuration of Δ7,8 was confirmed by the correlation between H-7 and H-9b. The relative configuration of 3 was based on NOESY correlations of H-3/H-1 and H-11/H-1, suggested the 3a (1R*, 3S*, 4R*, 11S*, 12S*), 3b (1R*, 3S*, 4S*, 11S*, 12S*), 3c (1R*, 3S*, 4R*, 11S*, 12R*), and 3d (1R*, 3S*, 4S*, 11S*, 12R*) configurations. The relative configuration of the C-4 and C-12 chiral centers in 3 was determined by calculating the above four relative configurations. Ultimately, the absolute configuration of 3 was suggested by DP4+ analysis (100% for 3a) combined with ECD calculations as 1S, 3R, 4S, 11R, 12R (Figure 4).

The carbon skeleton of sinumollolide D (4) was readily assignable as the same as 1 by 1D NMR, HSQC, HMBC, and COSY correlations. One difference was the presence of an additional olefinic bond (δC 136.6 and 125.0) at Δ3,4. Further confirmation of this new bond came from a key HMBC (Figure 2) correlation between H-18, C-3, and C-4. The configurations of the Δ3,4 and the Δ7,8 double bonds were assigned as E based on the NOESY (Figure 3) correlations from H-9a to H-7 and from H-3 to H-5a/b, respectively. Furthermore, the NOESY correlation of H-1/H-11 confirmed the partial relative configuration of 1R*,11S*. The DP4+ analysis deduced the entire relative configuration as 1R*,11S*, 12R*, and the ECD calculation determined the absolute configuration of 1S, 11R, 12S (Figure 4).

Sinumollolide E (5) was isolated as a colorless crystal. Similar to compounds 1–4, the analysis of 1D (Table 1 and Table 2) and 2D (Figure 2) NMR correlations from four methyl groups established the consecutive fragment of the classic 12,17-α, β-unsaturated seven-membered cembranolides skeleton with an acetyl group at C-11, which was indicated by HMBC correlations from H-11 to C-21 and H-22 to C-21. Based on the HRESIMS data, compound 5 had the molecular formula C22H34O7 and six degrees of unsaturation. A tricyclic framework was thus required to account for these after excluding one double bond and two ester carbonyls. The presence of an oxygen bridge between C-4 and C-7 was confirmed by the molecular formula, the remaining one degree of unsaturation, and the resonances of C-7 at δC 85.7 and C-4 at δC 88.9. Therefore, the planar structure of 5 was established. The NOESY spectrum (Figure 3) correlations from H-7 to H-18, H-7 to H-11, and H-11 to H-1 were observed, and the chirality of C-3 and C-12 could not be elucidated. Fortunately, a suitable crystal of 5 was obtained, and its absolute structure (1R, 3S, 4R, 7S, 8R, 11R, 12R) was unambiguously determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction with Cu Kα radiation (Figure 5).

Analysis of the 1D, 2D NMR data (Table 1 and Table 2 and Figure 2), and HRESIMS revealed that sinumollolide F (6) possessed the same carbon skeleton as 5, except for the presence of a methoxy group in 6. The methoxy group was placed at C-8 (δC 78.3) because of the clear HMBC signal from C-23 (δC 49.1) to C-8. Additionally, the NOESY correlations from H-1 to H-11, H-1 to H-3, H-7 to H-18, H-1 to H-18, and H-19 to H-3 indicated two possible configurations 6a (1S*, 3R*, 4R*, 7S*, 8R*, 11S*, 12R*) and 6b (1S*, 3R*, 4R*, 7S*, 8R*, 11S*, 12S*). The DP4+ analysis deduced the relative configuration as 6b, and the absolute configuration 1R, 3S, 4S, 7R, 8S, 11R, 12R was determined by ECD calculations (Figure 4).

The 1H and 13C NMR data (Table 1 and Table 2) displayed the close similarity of sinumollolide G (7) with 5. Two major differences were the presence of the acetoxyl group at C-11 in 5 instead of the acetoxyl group at C-3 (δC 76.1) in 7, which was further confirmed by the HMBC (Figure 2) correlation from H-22 (δH 2.02) to C-21 (δC 170.1) and H-3 (δH 4.72) to C-21, and a keto group at C-11 in 7 instead of the acetoxyl group at C-11 in 5. The NOESY (Figure 3) correlations from H-1 to H-18, H-7 to H-18, and H-3 to H-19 indicated that there were four possible configurations: 7a (1S*, 3S*, 4S*, 7R*, 8R*, 12S*), 7b (1S*, 3R*, 4S*, 7R*, 8S*, 12S*), 7c (1S*, 3S*, 4S*, 7R*, 8R*, 12S*), and 7d (1S*, 3R*, 4S*, 7R*, 8S*, 12S*). This was also confirmed by the DP4+ analysis, which supported the 7d. The absolute configuration of 7 was 1R, 3S, 4R, 7S, 8R, 12R, indicated by ECD calculation (Figure 4).

The 1D and 2D NMR (Table 2 and Table 3 and Figure 2) spectra of sinumollolide H (8) were quite similar to 29, indicating that 8 had an analogous planar structure of 29 except for the presence of a methylene group at C-17 (δC 64.9) in 8 instead of the lactone group in 29. Compound 8 comprised a 7-membered ether ring, rather than the α, β-unsaturated lactone found in other related compounds. The NOESY (Figure 3) correlations from H-9a/b to H-7 and H-5b to H-3 indicated both the E-configurations of Δ4,5 and Δ7,8, while correlations from H-1 to H-11 and H-3 to H-14a, and H-14a to H-11 confirmed the partial relative configurations of 1R*,3S*,11R*,12R*, and 1R*,3S*,11R*,12S*. The DP4+ analysis predicted the relative configuration (12R*) to match the experimental results with 100% probability. The absolute configuration of 1R, 3S, 11R, 12R was determined by ECD calculations (Figure 4).

Table 3.

1H NMR spectroscopic data for compounds 8–12, 14 in CDCl3, and 13 in DMSO-d6.

A comparison of the 1D NMR (Table 2 and Table 3) spectra of sinumollolide I (9) and 27 revealed similar structural relationships. The most notable difference was the presence of a hydroxyl group at C-6 (δC 65.7) in 9 and that the seven-membered lactone ring of 27 underwent ring-opening, resulting in a quaternary carbon at C-12 (δC 74.3) with a hydroxyl substitution and a methoxy group connected to C-17, indicated by HMBC correlations from H-21 to C-17. To determine the relative configuration of 9, the NOESY signals from H-7 to H-9b indicated that the Δ7,8 double bond had an E configuration, as well as the related signals from H-1 to H-11, H-11 to H-20, H-6 to H-3, and H-6 to H-18. Thus, two possible configurations, 9a (1R*, 3S*, 4S*, 6R*, 11R*, 12S*) and 9b (1S*, 3S*, 4S*, 6R*, 11S*, 12R*), were calculated and 9a showed the best result. Based on the ECD analysis, the structure and absolute configuration of 9 were tentatively determined to be 1R, 3S, 4S, 6R, 11R, 12S (Figure 4).

Analysis of the 1D NMR (Table 2 and Table 3) data, 2D NMR (Figure 2) data, and HRESIMS revealed that sinumollolide J (10) possessed the same carbon skeleton as 9, with the main differences observed in the 2D NMR data for C-6, C-7, and C-8. This suggested that the trisubstituted double bond Δ7,8 and the hydroxyl group at C-6 in 9 were replaced by the disubstituted double bond Δ6,7 and a hydroxyl group at C-8 (δC 84.3) in 10, as indicated by the HMBC correlations from H-18 to C-7, C-8, and C-9. The NOESY experiment (Figure 3) of 10 showed correlations from H-7 to H-5, which indicated the E geometry of Δ6,7. Additional NOESY correlations were observed of H-16b to H-3, H-1, and H-20, of H-3 to H-18, and of H-7 to H-5. Thus, two possible configurations, 10a (1R*, 3R*, 4R*, 8R*, 11S*, 12R*) and 10b (1R*, 3R*, 4R*, 8S*, 11S*, 12R*) were calculated, and 10b showed the best result. The absolute configuration of 10 were determined as 1R, 3S, 4S, 8R, 11R, 12S by ECD calculation (Figure 4).

Sinumollolide K (11) was a colorless oil. The analysis of the 1D and 2D NMR (Table 2 and Table 3 and Figure 2) data indicated that 11 possessed a similar planar structure to 5. One difference between 5 and 11 was that the seven-membered lactone ring of 11 underwent ring-opening, resulting in a quaternary carbon at C-12 (δC 75.7) with a hydroxyl substitution and a methoxy group connected to C-17, indicated by HMBC correlation from H-21 to C-17. Another difference between 5 and 11 was the presence of a new five-membered ring provided by the key HMBC correlation from H-11 to C-8. The NOESY correlations from H-1 to H-3, H-3 to H-7, H-7 to H-19, H-3 to H-18, H-11 to H-20, H-11 to H-13a and H-13a to H-1 confirmed the relative configurations of 11. The absolute configuration of 11 was finally determined to be 1R, 3S, 4R, 7S, 8R, 11S, 12R by ECD comparison (Figure 4).

Sinumollolide L (12) was isolated as a colorless crystal. The NMR spectra of 12 (Table 2 and Table 3 and Figure 2) showed great similarities to those of the co-isolated compound 2, with main differences in the 1H NMR of δH 3.67 (3H, s) and δH 3.14 (3H, s). The HMBC correlations H-21 (δH 3.67) to C-17 (δC 177.6) and H-22 (δH 3.14) to C-12 (δC 78.5) suggested the opening of the seven-membered lactone ring and two methoxy substitutions. The absolute configuration of 12 was determined as 1R, 3R, 4R, 11S, 12R, 15S by X-ray crystallography (Figure 5).

A comparison of the 1D NMR spectra of sinumollolide M (13) with those of 7 (Table 2 and Table 3) revealed a similar structural relationship. The noticeable difference occurred in the opening of the seven-membered lactone ring in 13. The key HMBC (Figure 2) correlation from H-21 (δH 3.69) to C-17 (δC 166.5) also verified this deduction. Thus, 13 was determined to be the open-loop derivative of 7. Finally, the absolute configuration of 13 was unambiguously determined as 1R, 3S, 4R, 7S, 8R, 12R (Figure 5) by single-crystal X-ray diffraction with Cu Kα radiation.

Sinumollolide N (14) was isolated as a colorless oil. By comparing the 1D NMR spectra (Table 2 and Table 3), it was found that 14 and 10 had similar planar structures. The molecular formula was elucidated as C21H32O6 based on the HRESIMS data, which was two mass units less than that of 10. The key HMBC (Figure 2) correlation from H-20 to C-11 also verified that the hydroxyl-substituted C-11 in 10 was oxidized to a carbonyl group in 14. The NOESY (Figure 3) correlations H-7 to H-5a suggested that the E geometry of the double bond Δ6,7, and the relative configuration of 14, was determined by the correlations from H-18 to H-1 and H-1 to H-12. To confirm the relative stereochemistry of C-3 and C-8, the computed chemical shifts in the four configurations, 14a (1S*, 3R*, 4R*, 8R*, 12R*), 14b (1S*, 3R*, 4R*, 8S*, 12R*), 14c (1S*, 3S*, 4R*, 8R*, 12R*), and 14d (1S*, 3S*, 4R*, 8R*, 12R*), were compared with the experimental values, and the results showed that 14a provided the best fit. The absolute configuration of 14 was finally determined to be 1R, 3S, 4S, 8S, 12S by comparing the experimental and calculated ECD spectra (Figure 4).

Those known cembranolides diterpenes were identified as 11-dehydrosinulariolide (15) [22], Flexibilisolide D (16) [23], querciformolide A (17) [24], sinulaflexiolide C (18) [25], sinulariolone (19) [24], 5,8-epoxycembranolide (20) [26], flexibilisolide E (21) [23], flexibolide (22) [26], 11-epi-sinulariolide acetate (23) [27], granosolide B (24) [24], dendronpholide Q (25) [28], sinulariaoid D (26) [8], sandensolide (27) [29], capillolide (28) [30], (−)-sandensolide (29) [31], granosolide D (30) [32], sinulaflexiolide E (31) [25], dendronpholide P (32) [28], sinuflexibilin A (33) [33], flexibilisin B (34) [34], dendronpholide C (35) [28], and granosolide C (36) [32], by comparing with reported spectroscopic data, respectively.

2.3. Biological Activity and SAR

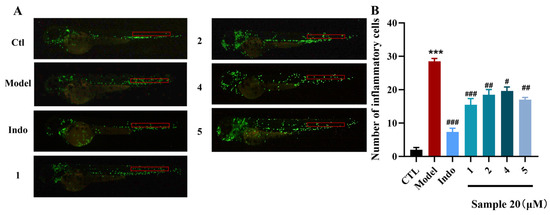

Zebrafish serves as an ideal vertebrate model for neurological research because it exhibits high homology with humans, possesses a nervous system that retains key mammalian characteristics, including conserved brain structure and myelination, and offers a short developmental cycle and a relatively simple neural system for practical experimental advantages [35]. The zebrafish were divided into blank (CTL), model, positive drug (indomethacin), and sample groups. Exposure of model zebrafish to CuSO4 resulted in a significant increase in the number of macrophages within the zebrafish neuromast region compared to the control group. The number of macrophages in the neuromast region significantly increased from 2.00 ± 0.68 in the control group to 28.50 ± 0.85 in model zebrafish (p < 0.001) (Figure 6A). This finding suggested that initial nerve injury triggers the activation and aggregation of local immune cells, leading to a subsequent neuroinflammatory response. The positive drug group, indomethacin (Indo) at a concentration of 20 μM reduced the number of macrophages in the neuromasts of inflamed zebrafish, with an inhibition rate of 73.9%. After treatment with compounds 1−14 at 20 μM, as shown in Figure 6B, compounds 1, 2, 4, and 5 showed moderate anti-inflammatory activity by alleviating migration and decreasing the number of macrophages surrounding the neuromasts in CuSO4-induced transgenic fluorescent zebrafish with the inhibition rates 45.6%, 35.1%, 30.4% and 39.7%, respectively. In addition, compounds did not cause obvious developmental abnormalities or death in zebrafish at 20 μM, confirming their low toxicity.

Figure 6.

Anti-inflammatory effect of compounds 1, 2, 4, and 5. (A) Inflammatory areas (red box) in transgenic fluorescent zebrafish (Tg: zlyz-EGFP) generated by CuSO4 that express enhanced green fluorescent protein after being treated with compounds 1, 2, 4, and 5. (B) Quantitative evaluation of fluorescent macrophage counts in the vicinity of inflammatory sites in zebrafish treated with compounds 1, 2, 4, and 5. Ordinary one-way ANOVA, n = 3 biological replicates. *** p ≤ 0.001 vs. CTL, # p ≤ 0.05 vs. model, ## p ≤ 0.01 vs. model, ### p ≤ 0.001 vs. model.

Analysis of the structure-activity relationship (SAR) revealed several key determinants for the bioactivity of these cembranolides. The presence of the seven-membered lactone moiety (2, 16) conferred significantly greater activity than its absence (12, 14), indicating the fragment was essential. Furthermore, the presence of a C-15, C-16 double bond enhanced anti-inflammatory activity, evidenced by the comparison between 1 and 2. Hydroxyl substitution at the C-3 position is an essential group for activity (7 vs. 19). Conversely, in seven-membered cembranolides featuring a C-4 and C-7 furan ring, substitution at the C-8 position with a methoxy group or configuration of C-4, C-7, and C-8 was detrimental, leading to a marked reduction or even a complete loss of activity (5 vs. 6).

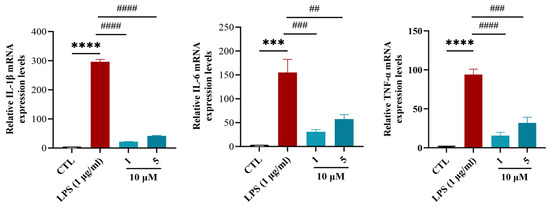

Anti-inflammatory effects were investigated in an LPS-induced BV-2 microglial model to circumvent the confounding influences of peripheral inflammation and complex in vivo cellular interactions. LPS stimulation significantly upregulated the mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in BV-2 cells, indicating the successful activation of microglia and initiation of an inflammatory response [36]. In addition, we used CCK8 to detect whether the cytotoxicity of compounds 1 and 5 had a significant impact on BV-2 cell viability at 10 μM, showing inhibition rates of only 5.6% and 7.4%, respectively. These favorable safety profiles supported their selection for subsequent anti-inflammatory studies. Cells were divided into blank (CTL), LPS-stimulated (1 μg/mL LPS), and sample groups (1 μg/mL LPS + 10μM compounds 1 or 5) (n = 3 biological replicates). In the LPS-treated sample group, treatment with compounds 1 and 5 at 10 μM downregulated the mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 compared with the LPS-treated group. Among these, compound 1 exhibited the best inhibitory effect (Figure 7). This demonstrated that the compounds inhibited levels of inflammatory factors and directly inhibited inflammation in microglia.

Figure 7.

The effects of compounds 1 and 5 on the mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in LPS-induced BV-2 cells. Ordinary one-way ANOVA, n = 3 biological replicates. *** p ≤ 0.001 vs. CTL, **** p ≤ 0.0001 vs. CTL, # p ≤ 0.05 vs. LPS (1 μg/mL), ## p ≤ 0.01 vs. LPS (1 μg/mL), ### p ≤ 0.001 vs. LPS (1 μg/mL), #### p ≤ 0.0001 vs. LPS (1 μg/mL).

Compounds 1 and 5 suppressed TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells at 10 μM, with compound 1 showing comparable or superior inhibitory effects. Based on previous studies [17], seven-membered lactone ring cembrane diterpenes, 11-epi-sinulariolide acetate and 5-dehydrosinulariolide, inhibit LPS-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in RAW 264.7 macrophages by suppressing the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65, ERK1/2, and JNK3 signaling molecules.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed by pre-coated silica gel plates (GF254, Qingdao, China), and the chromo-genic reagent was EtOH with 5% H2SO4. Column chromatography (CC) was performed with silica gel (100–400 mesh, Qingdao Marine Chemical Inc., Qingdao, China) and ODS silica gel (50 μm, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). HPLC was performed on a Waters 2695/2998 instrument with a PDA detector (Milford, Worcester, MA, American), equipped with an analytic reversed-phased column (Silgreen C18, 10 × 250 mm, 5 μm, Beijjing, China). Chiral separations were performed on the same system using a Daicel Chiral pack IC column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm, Osaka, Japan). NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AVANCE NEO 400 MHz and Bruker AVANCE NEO 500 MHz (Bruker, Faellanden, Switzerland). HRESIMS data were acquired by a Waters Micro-mass Q-Tof Ultima GLOBAL GAA076 LC mass spectrometer (Autospec-Ultima-TOF, Waters, Shanghai, China). UV and CD spectra were taken on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter (Beckman Ltd., Shanghai, China). Optical rotation spectra were measured by a Jasco P-1020 digital polarimeter (JASCO Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected by a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (Bruker, Beijing, China). Melting points were determined on a SWG X-4A microscopic melting point apparatus (Shanghai Yidian Physical Optics Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

3.2. Soft Coral Material

The soft coral Sinularia mollis was collected from the Xisha Islands in the South China Sea in 2018. The specimen was identified by Prof. Ping-Jyun Sung of the Institute of Marine Biotechnology, Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium, Pingtung 944, Taiwan. A voucher specimen (No. XS-ly-39), frozen immediately at −20 °C, was deposited at the School of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China.

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

The fresh specimen of Sinularia mollis (7.3 kg, wet weight) was crushed and extracted with MeOH six times (each time for seven days) at room temperature, and then the concentrated residue (107.2 g) was dissolved in MeOH (1 L) to remove salts. The total extract was divided into 14 fractions (Frs. 1–14) by the vacuum liquid chromatography on a silica gel column eluting with a gradient of petroleum ether/acetone (from 50:1 to 1:1, V:V) and CH2Cl2/MeOH (from 10:1 to 1:1, V:V). See the Supplementary Materials for more details.

Sinumollolide A (1): colorless crystal; [α +21.9 (c 0.70, CH3OH); m. p.: 145.4 °C–149.9 °C; UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 198 (3.1) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CD3OD) see Table 1 and Table 2; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H33O5, 353.2323; found, 353.2321. The crystallographic data have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center as CCDC 2493949.

Sinumollolide B (2): colorless crystals; [α +9.6 (c 0.28, CH3OH); m. p.: 140.4 °C− 143.6 °C; UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 193 (3.1) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CD3OD) see Table 1 and Table 2; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H35O5, 355.2479; found, 355.2478. The crystallographic data have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center as CCDC 2493954.

Sinumollolide C (3): colorless oil; [α +11.1 (c 0.09, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 194 (2.6) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CDCl3) see Table 1 and Table 2; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C22H33O5, 377.2323; found, 377.2320.

Sinumollolide D (4): colorless oil; [α +17.6 (c 0.07, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 193 (2.7) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CDCl3) see Table 1 and Table 2; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H31O3, 319.2268; found, 319.2259.

Sinumollolide E (5): colorless crystals; [α +6.5 (c 0.93, CH3OH); m. p.: 208.2 °C–210.3 °C; UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 207 (3.1) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CD3OD) see Table 1 and Table 2; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C22H35O7, 411.2377; found, 411.2373. The crystallographic data have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center as CCDC 2493967.

Sinumollolide F (6): colorless oil; [α −10.0 (c 0.05, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 201 (2.5) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CDCl3) see Table 1 and Table 2; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C23H37O7, 425.2534; found, 425.2543.

Sinumollolide G (7): colorless oil; [α −0.8 (c 0.65, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 211 (2.7) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CDCl3) see Table 1 and Table 2; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C22H33O7, 409.2221; found, 409.2226.

Sinumollolide H (8): colorless oil; [α −4.3 (c 0.07, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 197 (3.1) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CDCl3) see Table 2 and Table 3; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M −H2O+ H]+ calcd for C20H31O2, 303.2319; found, 303.2320.

Sinumollolide I (9): colorless oil; [α −9.1 (c 0.05, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 197 (3.1) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CDCl3) see Table 2 and Table 3; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C21H35O6, 383.2428; found, 383.2432.

Sinumollolide J (10): colorless oil; [α −3.5 (c 0.14, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 194 (2.7) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CDCl3) see Table 2 and Table 3; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C21H34O6Na, 405.2248; found, 405.2259.

Sinumollolide K (11): colorless oil; [α −1.1 (c 0.25, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 196 (3.0) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CDCl3) see Table 2 and Table 3; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C21H35O6Na, 383.2428; found, 383.2430.

Sinumollolide L (12): colorless crystals; [α −1.5 (c 0.34, CH3OH); m. p.: 143.7 °C–147.2 °C; UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 192 (2.6) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CDCl3) see Table 2 and Table 3; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C22H40O6Na, 423.2717; found, 423.2722. The crystallographic data have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center as CCDC 2493976.

Sinumollolide M (13): colorless crystals; [α +8.3 (c 0.70, CH3OH); m. p.: 158.0 °C–162.1 °C; UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε): 194 (3.2), 208 (3.1) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) see Table 2 and Table 3; Positive HRESIMS (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C23H36O8Na, 463.2302; found, 463.2307. The crystallographic data have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center as CCDC 2493978.

3.4. HSQC-Based SMART Analysis

HSQC spectra of 14 primary fractions were acquired by Bruker AVANCE NEO 500 MHz NMR (solvents: CD3OD, CDCl3, DMSO-d6) and processed with MestReNova (baseline correction, phase adjustment, peak picking). The HSQC spectra of the fractions were uploaded to the SMART 2.1 online platform (http://smart.ucsd.edu/classic, accessed on 20 December 2023) for dereplication and scaffold predictions. The platform generated candidate structures with cosine similarity scores (>0.7 significant) and predicted cembranolide-enriched fractions (Frs. 6, 7, 9, 10, 13), guiding their prioritization for further separation.

3.5. X-Ray Diffraction Data Analysis

The crystallographic data and X-ray structure analyses of 1, 2, 5, 12, and 13 (Figure 4) were provided in the Supplementary Material.

3.6. Anti-Inflammatory Assays in Zebrafish

The assay was performed using 3 dpf (days post-fertilization) healthy macrophage fluorescent transgenic zebrafish (Tg: zlyz-EGFP), which were provided by the Zebrafish Drug Screening Platform of the Institute of Biology, Shandong Academy of Sciences. The zebrafish were divided into blank (CTL), model, positive drug (indomethacin), and sample groups (n = 3 biological replicates). Following a 2 h co-incubation with compounds 1−14 (for sample groups), the zebrafish underwent a 1 h treatment with 20 μM CuSO4 in the dark. Macrophage counts around neuromasts were performed using a fluorescence microscope (Tokyo, Japan), and statistical analysis was performed using ordinary one-way ANOVA (GraphPad Prism 10), with p < 0.05 considered significant.

3.7. Anti-Inflammatory Assays in BV-2 Cells

Cell culture. Mouse microglial cells (BV-2 cell line) were obtained from Servicebio Biotechnology Co. (Wuhan, China). The cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were incubated in a condition of 5% CO2 and 95% humidity at 37 °C. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the BeyoRT™ II First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (RNase H-) (D7168L, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Real-time PCR was performed using Hieff® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (11203ES03, Yeasen, Shanghai, China). Relative mRNA expression of the respective genes was normalized to GAPDH in the same sample using the 2–ΔΔCT method. The mouse primers used in this study are listed below: IL-1β, 5′-CTTTCCCGTGGACCTTCCA′-3′ and 5′-CTCGGAGCCTGTAGTGCAGTT-3′; TNF-α, 5′-ACAAGGCTGCCCCGACTAC-3′ and 5′-TGGGCTCATACCAGGGTTTG-3′; IL-6, 5′-ACCACTCCCAACAGACCTGTCT-3′ and 5′-CAGATTGTTTTCTGCAAGTGCAT’-3′.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test with GraphPad Prism 10. A p-value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

4. Conclusions

Marine cembranolides fused with a seven-membered lactone moiety at C-1 are known for their anti-inflammatory activities. Inspired by this, we conducted the first targeted investigation of S. mollis. Employing a SMART-guided isolation strategy, we efficiently obtained 36 cembranolides, including 14 new (1–14) and 22 known (15–36) analogs. The anti-inflammatory potential of 14 new compounds was evaluated in CuSO4-induced transgenic fluorescent zebrafish. Compounds 1, 2, 4, and 5 exhibited potent inhibition rates at 20 μM, with an inhibition from 30.4% to 45.6% compared to the positive drug group. Subsequent inflammatory effects studies revealed that compounds 1 and 5 at 10 μM significantly suppressed the LPS-induced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. In summary, these findings enrich the chemical diversity of marine cembranolides and confirm their anti-inflammatory activities. They provide potential active structures and experimental basis for the development of anti-inflammatory agents targeting immune cell function, offering valuable insights into soft coral-derived anti-inflammatory drug discovery.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/md23120465/s1, Figures S1–S5: SMART results of Frs. 6, 7, 9, 10, and 13; Figures S6–S19: NMR, UV and MS spectrum of compounds 1–14; Tables S1–S5: X-ray crystallographic analysis of 1, 2, 5, 12, and 13. Tables S6–16: Calculation Details of 1–4, 6–11, and 14.

Author Contributions

Performed the experiments, isolated the compounds, and analyzed the spectral data, H.H.; funding acquisition, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.42576088, 42276088), the foundation of the State Key Laboratory of Component-based Chinese Medicine (Grant No. CBCM2024203), and supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 202461058).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article or Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yan, X.; Liu, J.; Leng, X.; Ouyang, H. Chemical Diversity and Biological Activity of Secondary Metabolites from Soft Coral Genus Sinularia since 2013. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Xu, W.; Yan, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, H.; Chen, L. Cembrane diterpenoids: Chemistry and pharmacological activities. Phytochemistry 2023, 212, 113703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, G. Structural and Biological Insights into the Hot-Spot Marine Natural Products Reported from 2012 to 2021. Chin. J. Chem. 2022, 40, 1867–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurrachma, M.Y.; Sakaraga, D.; Nugraha, A.Y.; Rahmawati, S.I.; Bayu, A.; Sukmarini, L.; Atikana, A.; Prasetyoputri, A.; Izzati, F.; Warsito, M.F.; et al. Cembranoids of Soft Corals: Recent Updates and Their Biological Activities. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2021, 11, 243–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N.; Li, H.; Wang, J.R.; Tang, W.; Zheng, M.Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, C.S.; Guo, Y.W. New Cembrane-Type Diterpenoids from the South China Sea Soft Coral Sinularia nanolobata. Chin. J. Chem. 2022, 40, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.-H.; Lin, K.-H.; Huang, C.-Y.; Hwang, T.-L.; Dai, C.-F.; Huang, H.-C.; Sheu, J.-H. Computationally Assisted Structural Elucidation of Cembranoids from the Soft Coral Sarcophyton tortuosum. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfanoudaki, M.; Shaikh, A.F.; Wang, D.; Singh, V.; Du, L.; Wilson, J.A.; Wamiru, A.; Goncharova, E.I.; Pruett, N.; Hoang, C.D.; et al. Identification of Cembrane Diterpenoids from Sinularia sp. That Reduce the Viability of Diffuse Pleural Mesothelioma Cell Lines. J. Nat. Prod. 2025, 88, 2193–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.-F.; Chen, M.-F.; Wang, T.; He, X.-X.; Liu, B.-X.; Deng, Y.; Chen, X.-J.; Li, Y.-T.; Guan, S.-Y.; Yao, J.-H.; et al. Novel cytotoxic nine-membered macrocyclic polysulfur cembranoid lactones from the soft coral Sinularia sp. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 6851–6858. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 6851–6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigami, S.; Nakagawa, R.; Yagi, F.; Takada, H.; Suzuki, A.; Kamada, T.; Nimura, K.; Oshima, I.; Phan, C.-S.; Ishii, T. Anti-biofouling marine diterpenoids from Okinawan soft corals. Biofouling 2025, 41, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.K.; Gu, F.F.; Li, S.W.; Guo, Y.W.; Gong, Y.X.; Su, M.Z. Two New Cembranoids from the Soft Coral Sinularia sp. with Antioxidant Activity. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202500141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Jin, Y.; Sun, R.N.; Hu, K.Y.; Yao, L.G.; Guo, Y.W.; Yuan, Z.H.; Li, X.W. Anti-HBV Activities of Cembranoids from the South China Sea Soft Coral Sinularia pedunculata and Their Structure Activity Relationship. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202401146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhouly, H.B.; Attia, E.Z.; Khedr, A.I.M.; Samy, M.N.; Fouad, M.A. Recent Updates on Sinularia Soft Coral. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 1152–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, T.; Kang, M.-C.; Phan, C.-S.; Zanil, I.; Jeon, Y.-J.; Vairappan, C. Bioactive Cembranoids from the Soft Coral Genus Sinularia sp. in Borneo. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.-C.; Yen, W.-H.; Su, J.-H.; Chiang, M.; Wen, Z.-H.; Chen, W.-F.; Lu, T.-J.; Chang, Y.-W.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, W.-H.; et al. Cembrane Derivatives from the Soft Corals, Sinularia gaweli and Sinularia flexibilis. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 2154–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.-H.; Li, W.-S.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Luo, H.; Wang, J.-R.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Zeng, Z.-R.; Chen, B.; Li, X.-W.; Guo, Y.-W. Sinusiaetone A, an Anti-inflammatory Norditerpenoid with a Bicyclo [11.3.0] hexadecane Nucleus from the Hainan Soft Coral Sinularia siaesensis. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 5621–5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, T.-C.; Chen, H.-Y.; Sheu, J.-H.; Chiang, M.Y.; Wen, Z.-H.; Dai, C.-F.; Su, J.-H. Structural Elucidation and Structure–Anti-inflammatory Activity Relationships of Cembranoids from Cultured Soft Corals Sinularia sandensis and Sinularia flexibilis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7211–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.-Y.; Jin, Y.; Sun, R.-N.; Wang, X.; Gao, C.-L.; Cui, X.-Y.; Chen, K.-X.; Sun, Y.-L.; Guo, Y.-W.; Li, J.; et al. The First Discovery of Marine Polyoxygenated Cembranolides as Potential Agents for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 12248–12260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reher, R.; Kim, H.W.; Zhang, C.; Mao, H.H.; Wang, M.; Nothias, L.-F.; Caraballo-Rodriguez, A.M.; Glukhov, E.; Teke, B.; Leao, T.; et al. A Convolutional Neural Network-Based Approach for the Rapid Annotation of Molecularly Diverse Natural Products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 4114–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yao, L.; Li, X.; Guo, Y. Yonarolide A, an unprecedented furanobutenolide-containing norcembranoid derivative formed by photoinduced intramolecular [2+2] cycloaddition. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Li, S.; Wei, Y.; Sun, Y.; Fu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Bioassay and NMR-HSQC-Guided Isolation and Identification of Phthalide Dimers with Anti-Inflammatory Activity from the Rhizomes of Angelica sinensis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 4630–4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Cui, Q.-Y.; Lin, Y.-W.; Lu, Q.-R.; Wu, S.-Q.; Fu, Y.-F.; Zhou, Q.-L.; Yuan, T.; et al. HSQC-guided discovery and structural optimization of antiadipogenic indole diterpenoids from endophytic fungus Penicillium janthinellum H-6. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 297, 117956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Su, P.; Gu, Q.; Li, W.D.; Guo, J.L.; Qiao, W.; Feng, D.Q.; Tang, S.A. Antifouling activity against bryozoan and barnacle by cembrane diterpenes from the soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 120, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.-J.; Tseng, Y.-J.; Huang, C.-Y.; Wen, Z.-H.; Dai, C.-F.; Sheu, J.-H. Cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory diterpenoids from the Dongsha Atoll soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-F.; Wen, Z.-H.; Su, J.-H.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Chiang, M.Y.; Sheu, J.-H. Anti-inflammatory Cembranoids from the Soft Corals Sinularia querciformis and Sinularia granosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1754–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Ding, Y.; Deng, Z.; van Ofwegen, L.; Proksch, P.; Lin, W. Sinulaflexiolides A–K, Cembrane-Type Diterpenoids from the Chinese Soft Coral Sinularia flexibilis. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjaneyulu, A.S.R.; Sagar, K.S.; Rao, G.V. New Cembranoid Lactones from the Indian Ocean Soft Coral Sinularia flexibilis. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.-W.; Chang, F.-R.; McPhail, A.T.; Lee, K.-H.; Wu, Y.-C. New cembranolide analogues from the formosan soft coral Sinularia flexibilis and their cytotoxicity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2003, 17, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Deng, Z.; van Ofwegen, L.; Bayer, M.; Proksch, P.; Lin, W. Dendronpholides A–R, Cembranoid Diterpenes from the Chinese Soft Coral Dendronephthya sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1152–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjaneyulu, A.S.R.; Rao, G.V.; Sagar, K.S.; Kumar, K.R.; Mohan, K.C. Sandensolide: A New Dihydroxycembranolide from the Soft Coral, Sinularia sandensis Verseveldt of the Indian Ocean. Nat. Prod. Lett. 1995, 7, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Yang, R.; Kuang, Y.; Zeng, L. A New Cembranolide from the Soft Coral Sinularia capillosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1543–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-C.; Su, J.-H.; Chiang, M.; Lu, M.-C.; Hwang, T.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Hu, W.-P.; Lin, N.-C.; Wang, W.-H.; Fang, L.-S.; et al. Flexibilins A–C, New Cembrane-Type Diterpenoids from the Formosan Soft Coral, Sinularia flexibilis. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 1999–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Su, J.-H.; Huang, C.-Y.; Liu, Y.-C.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Wen, Z.-H.; Hsu, C.-H.; Sheu, J.-H. Cembranoids from the Soft Corals Sinularia granosa and Sinularia querciformis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 58, 464–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Zhou, X.; Huang, H.; Yang, X.-W.; Liu, J.; Lin, X.; Li, X.; Peng, Y.; Liu, Y. New Cembrane Diterpenoids from a Hainan Soft Coral Sinularia sp. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 2023–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.-H.; Lin, Y.-F.; Lu, Y.; Yeh, H.-C.; Wang, W.-H.; Fan, T.-Y.; Sheu, J.-H. Oxygenated Cembranoids from the Cultured and Wild-Type Soft Corals Sinularia flexibilis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 57, 1189–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrogiovanni, M.; Martínez-Navarro, F.J.; Bowman, T.V.; Cayuela, M.L. Inflammation in Development and Aging: Insights from the Zebrafish Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Huang, M.-Y.; Song, X.-J. Characterization of Inflammatory Signals in BV-2 Microglia in Response to Wnt3a. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).