The Tetrapeptide HAEE Promotes Amyloid-Beta Clearance from the Brain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

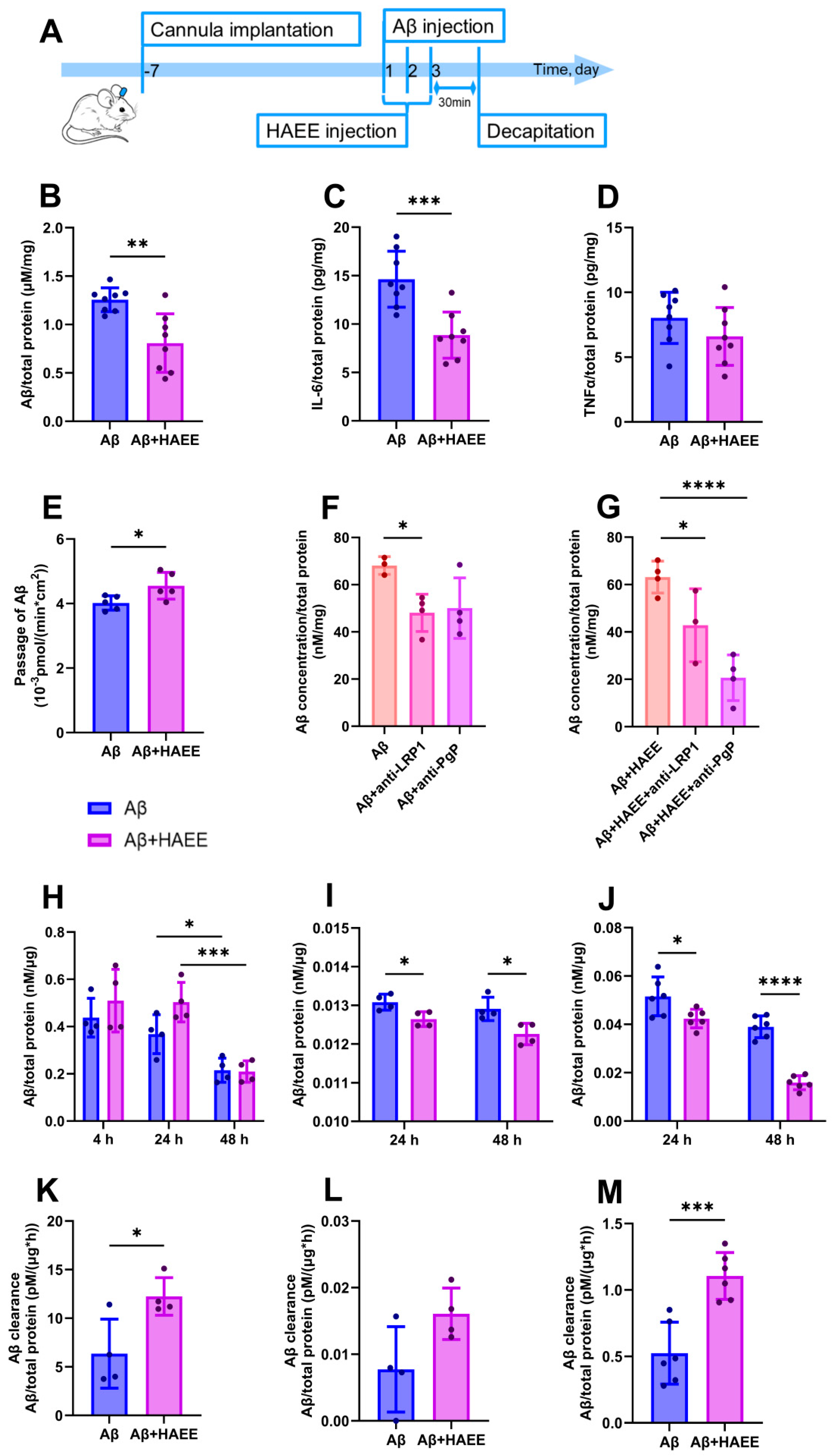

2.1. HAEE Reduces Aβ and IL-6 Levels in the Mouse Brain and Accelerates Aβ Transport Across the BBB In Vitro

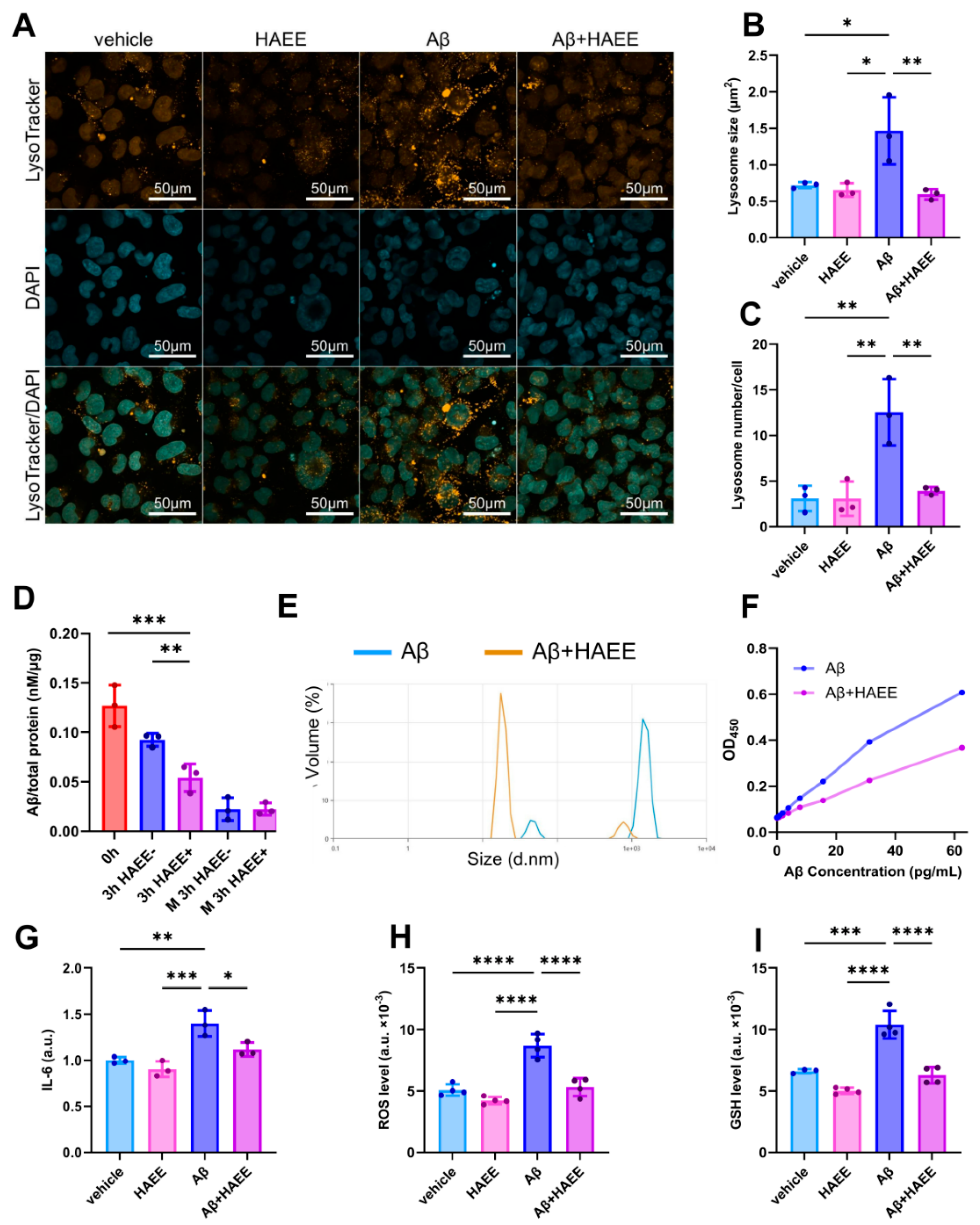

2.2. HAEE Enhances Aβ Clearance by Microglia and Reduces Aβ-Induced Microglial Activation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Oligomeric Aβ and HAEE for Intracerebroventricular Injections

4.2. Animals

4.3. Surgical Procedure and Drug Administration

4.4. Sample Collection and Biochemical Analysis

4.5. Cell Cultures

4.6. Analysis of HAEE’s and Aβ’s Effects on the Cells

4.7. ELISA

4.8. Oligomer-Specific ELISA

4.9. BBB Transwell Model

4.10. Inhibitory Assay

4.11. Aβ Degradation Assay

4.12. Flow Cytometry Analysis

4.13. Lysosomal Staining and Visualization

4.14. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

4.15. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Li, X.; Feng, X.; Sun, X.; Hou, N.; Han, F.; Liu, Y. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 937486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, X. Alzheimer’s disease: Insights into pathology, molecular mechanisms, and therapy. Protein Cell 2025, 16, 83–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viles, J.H. Imaging Amyloid-β Membrane Interactions: Ion-Channel Pores and Lipid-Bilayer Permeability in Alzheimer’s Disease. Angew. Chem. (Int. Ed. Engl.) 2023, 62, e202215785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranjape, G.S.; Gouwens, L.K.; Osborn, D.C.; Nichols, M.R. Isolated amyloid-β(1-42) protofibrils, but not isolated fibrils, are robust stimulators of microglia. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2012, 3, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolobova, E.; Petrushanko, I.; Mitkevich, V.; Makarov, A.A.; Grigorova, I.L. β-Amyloids and Immune Responses Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2024, 13, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elamin, S.A.; Al Shibli, A.N.; Shaito, A.; Al-Maadhadi, M.J.M.B.; Zolezzi, M.; Pedersen, S. Anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody therapies in Alzheimer’s disease—A scoping review. Neuroscience 2025, 589, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, E.; Paylor, S.; Van, C.; Mathews, B.; Sobhanian, M.J.; Mansour, D.Z.; Hennawi, G.; Brandt, N.J. Review of anti-amyloid-beta (Aβ) monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozin, S.A.; Barykin, E.P.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Makarov, A.A. Anti-amyloid Therapy of Alzheimer’s Disease: Current State and Prospects. Biochemistry. Biokhimiia 2018, 83, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, L.; Wimo, A.; Handels, R.; Johansson, G.; Boada, M.; Engelborghs, S.; Frölich, L.; Jessen, F.; Kehoe, P.G.; Kramberger, M.; et al. The affordability of lecanemab, an amyloid-targeting therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: An EADC-EC viewpoint. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2023, 29, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechko, O.I.; Mukhina, K.A.; Yanvarev, D.V.; Eremina, S.Y.; Katkova-Zhukotskaya, O.A.; Chaprov, K.D.; Drutskaya, M.S.; Kozin, S.A.; Makarov, A.A.; Mitkevich, V.A. Therapeutic Potential of HAEEPGP Peptide Against β-Amyloid Induced Neuropathology. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 63, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barykin, E.P.; Garifulina, A.I.; Tolstova, A.P.; Anashkina, A.A.; Adzhubei, A.A.; Mezentsev, Y.V.; Shelukhina, I.V.; Kozin, S.A.; Tsetlin, V.I.; Makarov, A.A. Tetrapeptide Ac-HAEE-NH2 Protects α4β2 nAChR from Inhibition by Aβ. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, P.O.; Kulikova, A.A.; Golovin, A.V.; Tkachev, Y.V.; Archakov, A.I.; Kozin, S.A.; Makarov, A.A. Minimal Zn2+ binding site of amyloid-β. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, L84–L86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolotarev, Y.A.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Shram, S.I.; Adzhubei, A.A.; Tolstova, A.P.; Talibov, O.B.; Dadayan, A.K.; Myasoyedov, N.F.; Makarov, A.A.; Kozin, S.A. Pharmacokinetics and Molecular Modeling Indicate nAChRα4-Derived Peptide HAEE Goes through the Blood-Brain Barrier. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Zhao, Z.; Montagne, A.; Nelson, A.R.; Zlokovic, B.V. Blood-Brain Barrier: From Physiology to Disease and Back. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 21–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Landreth, G.E. The role of microglia in amyloid clearance from the AD brain. J. Neural Transm. 2010, 117, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söllvander, S.; Nikitidou, E.; Brolin, R.; Söderberg, L.; Sehlin, D.; Lannfelt, L.; Erlandsson, A. Accumulation of amyloid-β by astrocytes result in enlarged endosomes and microvesicle-induced apoptosis of neurons. Mol. Neurodegener. 2016, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Olst, L.; Simonton, B.; Edwards, A.J.; Forsyth, A.V.; Boles, J.; Jamshidi, P.; Watson, T.; Shepard, N.; Krainc, T.; Argue, B.M.; et al. Microglial mechanisms drive amyloid-β clearance in immunized patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1604–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrekar, S.; Jiang, Q.; Lee, C.Y.; Koenigsknecht-Talboo, J.; Holtzman, D.M.; Landreth, G.E. Microglia mediate the clearance of soluble Abeta through fluid phase macropinocytosis. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 4252–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, P.O.; Cheglakov, I.B.; Ovsepyan, A.A.; Mediannikov, O.Y.; Morozov, A.O.; Telegin, G.B.; Kozin, S.A. Peripherally Applied Synthetic Tetrapeptides HAEE and RADD Slow Down the Development of Cerebral β-Amyloidosis in AβPP/PS1 Transgenic Mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 46, 849–853, Erratum in J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 49, 265. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-159005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zong, S.; Cui, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Z. The effects of microglia-associated neuroinflammation on Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1117172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.S.A.; Oliver, P.L. ROS Generation in Microglia: Understanding Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhalifa, A.E.; Al Mokhlf, A.; Ali, H.; Al-Ghraiybah, N.F.; Syropoulou, V. Anti-Amyloid Monoclonal Antibodies for Alzheimer’s Disease: Evidence, ARIA Risk, and Precision Patient Selection. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroczko, B.; Groblewska, M.; Litman-Zawadzka, A.; Kornhuber, J.; Lewczuk, P. Amyloid β oligomers (AβOs) in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2018, 125, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haass, C.; Selkoe, D. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: Lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Yang, J. Interactions between amyloid β peptide and lipid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembranes 2018, 1860, 1663–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, L.C. Aβ Plaques. Free Neuropathol. 2020, 1, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, D.; Sharma, V.; Deshmukh, R. Activation of microglia and astrocytes: A roadway to neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitkevich, V.A.; Barykin, E.P.; Eremina, S.; Pani, B.; Katkova-Zhukotskaya, O.; Polshakov, V.I.; Adzhubei, A.A.; Kozin, S.A.; Mironov, A.S.; Makarov, A.A.; et al. Zn-dependent β-amyloid Aggregation and its Reversal by the Tetrapeptide HAEE. Aging Dis. 2023, 14, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeth, T.R.; Julian, R.R. Proteolysis of Amyloid β by Lysosomal Enzymes as a Function of Fibril Morphology. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 31520–31527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Lee, E.J. Advances in Amyloid-β Clearance in the Brain and Periphery: Implications for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Exp. Neurobiol. 2023, 32, 216–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xiang, P.; Duro-Castano, A.; Cai, H.; Guo, B.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Lui, S.; Luo, K.; Ke, B.; et al. Rapid amyloid-β clearance and cognitive recovery through multivalent modulation of blood-brain barrier transport. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirrito, J.R.; Deane, R.; Fagan, A.M.; Spinner, M.L.; Parsadanian, M.; Finn, M.B.; Jiang, H.; Prior, J.L.; Sagare, A.; Bales, K.R.; et al. P-glycoprotein deficiency at the blood-brain barrier increases amyloid-beta deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 3285–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, A.B.; Leung, G.K.F.; Callaghan, R.; Gelissen, I.C. P-glycoprotein: A role in the export of amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease? FEBS J. 2020, 287, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Baldeshwiler, A.; Abner, E.L.; Bauer, B.; Hartz, A.M.S. Protecting P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier from degradation in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Fluids Barriers CNS 2021, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D. Astrocytic and microglial cells as the modulators of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Osse, A.M.L.; Cammann, D.; Powell, J.; Chen, J. Anti-Amyloid Monoclonal Antibodies for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. BioDrugs Clin. Immunother. Biopharm. Gene Ther. 2024, 38, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirescu, C. Characterization of the first TREM2 small molecule agonist, VG-3927, for clinical development in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 20 (Suppl. S6), e084622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Pan, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Tian, F.; Li, M.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; Qin, C. Interleukin-6 deficiency reduces neuroinflammation by inhibiting the STAT3-cGAS-STING pathway in Alzheimer’s disease mice. J. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 21, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyra, E.; Silva, N.M.; Gonçalves, R.A.; Pascoal, T.A.; Lima-Filho, R.A.S.; Resende, E.P.F.; Vieira, E.L.M.; Teixeira, A.L.; de Souza, L.C.; Peny, J.A.; et al. Pro-inflammatory interleukin-6 signaling links cognitive impairments and peripheral metabolic alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiukas, Z.; Tangalakis, K.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Feehan, J. Microglial activation states and their implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 12, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jin, H.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Găman, M.A.; Zou, Z. The multifaceted roles of apolipoprotein E4 in Alzheimer’s disease pathology and potential therapeutic strategies. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.I.; Yu, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, B.; Jang, M.J.; Jo, H.; Kim, N.Y.; Pak, M.E.; Kim, J.K.; Cho, S.; et al. Astrocyte priming enhances microglial Aβ clearance and is compromised by APOE4. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhina, K.A.; Kechko, O.I.; Osypov, A.A.; Petrushanko, I.Y.; Makarov, A.A.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Popova, I.Y. Short-Term Inhibition of NOX2 Prevents the Development of Aβ-Induced Pathology in Mice. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxinos, G.; Franklin, K.B.J. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schildge, S.; Bohrer, C.; Beck, K.; Schachtrup, C. Isolation and culture of mouse cortical astrocytes. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 71, 50079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshavskaya, K.B.; Petrushanko, I.Y.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Barykin, E.P.; Makarov, A.A. Post-translational modifications of beta-amyloid alter its transport in the blood-brain barrier in vitro model. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1362581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Hong, S.; O’Malley, T.; Sperling, R.A.; Walsh, D.M.; Selkoe, D.J. New ELISAs with high specificity for soluble oligomers of amyloid β-protein detect natural Aβ oligomers in human brain but not CSF. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2013, 9, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mukhina, K.A.; Varshavskaya, K.B.; Rybak, A.D.; Grishchenko, V.V.; Kuzubova, E.V.; Korokin, M.V.; Kechko, O.I.; Mitkevich, V.A. The Tetrapeptide HAEE Promotes Amyloid-Beta Clearance from the Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311591

Mukhina KA, Varshavskaya KB, Rybak AD, Grishchenko VV, Kuzubova EV, Korokin MV, Kechko OI, Mitkevich VA. The Tetrapeptide HAEE Promotes Amyloid-Beta Clearance from the Brain. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311591

Chicago/Turabian StyleMukhina, Kristina A., Kseniya B. Varshavskaya, Aleksandra D. Rybak, Viktor V. Grishchenko, Elena V. Kuzubova, Mikhail V. Korokin, Olga I. Kechko, and Vladimir A. Mitkevich. 2025. "The Tetrapeptide HAEE Promotes Amyloid-Beta Clearance from the Brain" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311591

APA StyleMukhina, K. A., Varshavskaya, K. B., Rybak, A. D., Grishchenko, V. V., Kuzubova, E. V., Korokin, M. V., Kechko, O. I., & Mitkevich, V. A. (2025). The Tetrapeptide HAEE Promotes Amyloid-Beta Clearance from the Brain. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311591