Obesity and Depression: A Pathophysiotoxic Relationship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Epidemiology

3.1. Obesity (HP:0001513)

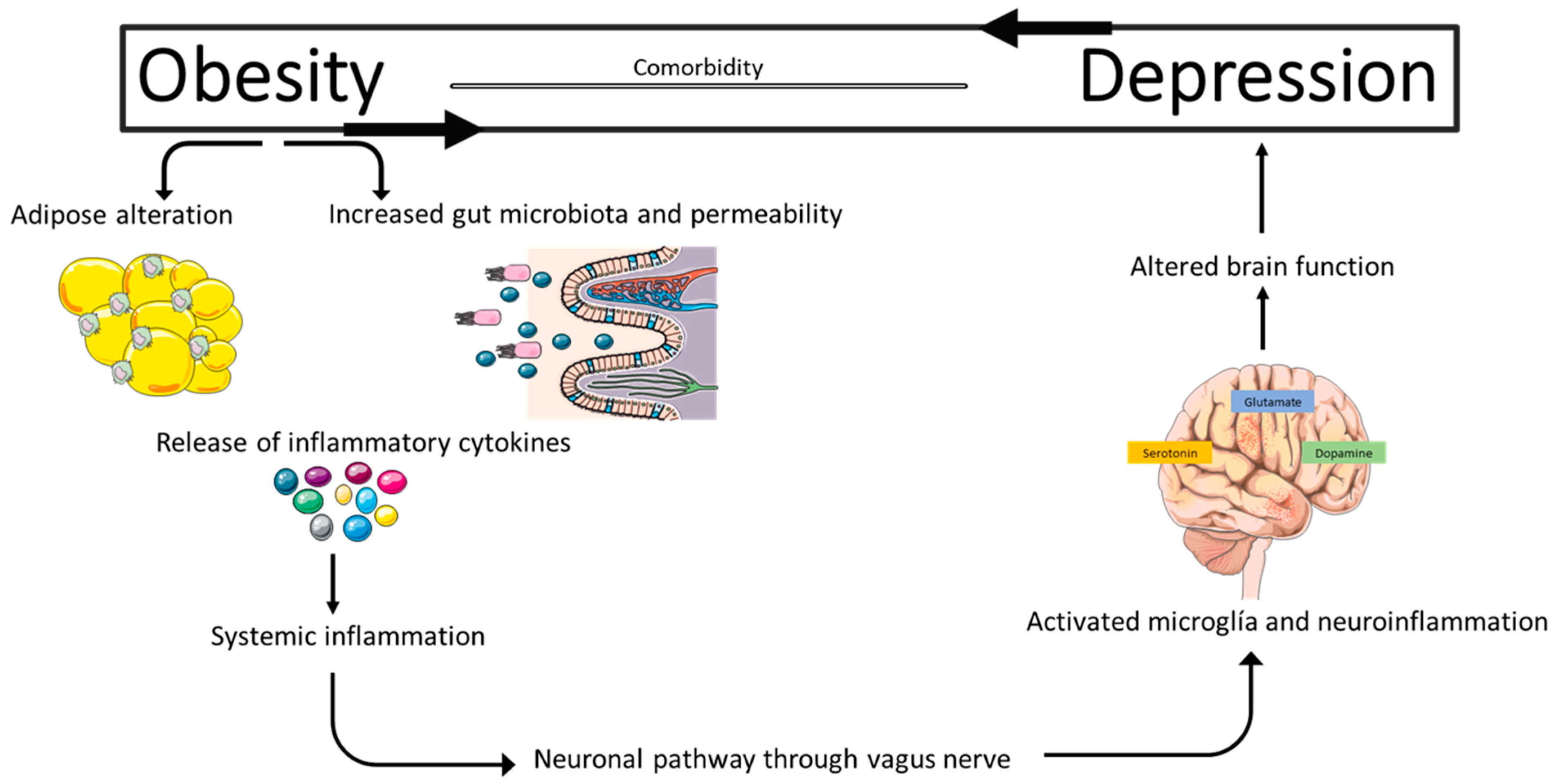

3.2. Major Depressive Disorder (OMIM:608516)

4. Pathophysiology of Obesity

4.1. Genetics

4.2. Neuroendocrine Dysregulation

4.3. Peripheral Metabolic Dysregulation

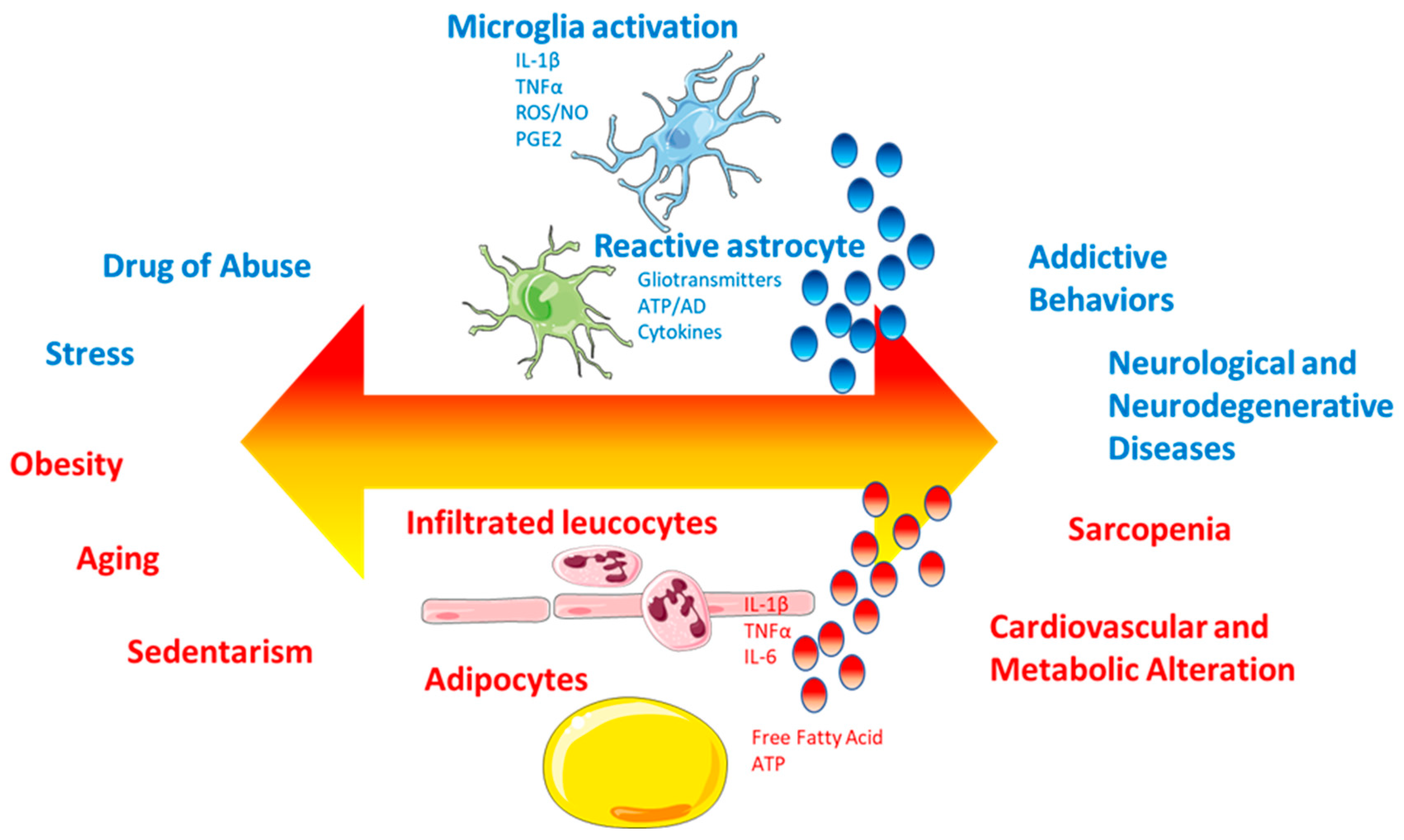

4.4. Peripheral and Central Inflammation

4.5. Microbiota-Gut–Brain Axis

5. Pathophysiology of Depression

5.1. Monoaminergic Hypothesis

5.2. Inflammatory Hypothesis

5.3. Neurotrophic Hypothesis and Neurogenesis

6. A Pathophysiological and Toxic Relationship

6.1. Chronic Systemic Inflammation as a Central Link

6.2. Neurotoxic Effects of Lipids and Adipokines

6.3. Gut–Brain Axis Dysfunction

6.4. HPA Axis and Cortisol: Pathophysiological Mediator

6.5. Clinical Implications

7. Research Projections

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Milaneschi, Y.; Lamers, F.; Peyrot, W.J.; Baune, B.T.; Breen, G.; Dehghan, A.; Forstner, A.J.; Grabe, H.J.; Homuth, G.; Kan, C.; et al. Genetic Association of Major Depression with Atypical Features and Obesity-Related Immunometabolic Dysregulations. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 1214–1225, Erratum in JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgland, S.L. Can treatment of obesity reduce depression or vice versa? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2021, 46, E313–E318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lores, T.; Musker, M.; Collins, K.; Burke, A.; Perry, S.W.; Wong, M.L.; Licinio, J. Pilot trial of a group cognitive behavioural therapy program for comorbid depression and obesity. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębski, J.; Przybyłowski, J.; Skibiak, K.; Czerwińska, M.; Walędziak, M.; Różańska-Walędziak, A. Depression and Obesity-Do We Know Everything about It? A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molyneaux, E.; Poston, L.; Ashurst-Williams, S.; Howard, L.M. Obesity and mental disorders during pregnancy and postpartum: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul-Haq, Z.; Smith, D.J.; Nicholl, B.I.; Cullen, B.; Martin, D.; Gill, J.M.; Evans, J.; Roberts, B.; Deary, I.J.; Gallacher, J.; et al. Gender differences in the association between adiposity and probable major depression: A cross-sectional study of 140,564 UK Biobank participants. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gower, B.A.; Shelton, R.C.; Wu, X. Gender-Specific Relationship between Obesity and Major Depression. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría. Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales (DSM-5®), 5th ed.; Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría: Arlington, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Capuron, L.; Lasselin, J.; Castanon, N. Role of Adiposity-Driven Inflammation in Depressive Morbidity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.E.; Stunkard, A.; Srole, L. Obesity, social class, and mental illness. JAMA 1962, 181, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, A.J.; Maggard-Gibbons, M.; Maher, A.R.; Booth, M.J.; Miake-Lye, I.; Beroes, J.M.; Shekelle, P.G. Mental Health Conditions Among Patients Seeking and Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: A Meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 315, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, L.; Luppino, F.; van Straten, A.; Penninx, B.; Zitman, F.; Cuijpers, P. Depression and obesity: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 178, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milano, W.; Ambrosio, P.; Carizzone, F.; De Biasio, V.; Di Munzio, W.; Foia, M.G.; Capasso, A. Depression and Obesity: Analysis of Common Biomarkers. Diseases 2020, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preiss, K.; Brennan, L.; Clarke, D. A systematic review of variables associated with the relationship between obesity and depression. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve, F.A.; Delgado-López, F.; Fernández-Tapia, B.; González, D.R. Adipose Tissue, Non-Communicable Diseases, and Physical Exercise: An Imperfect Triangle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargano, M.A.; Matentzoglu, N.; Coleman, B.; Addo-Lartey, E.B.; Anagnostopoulos, A.V.; Anderton, J.; Avillach, P.; Bagley, A.M.; Bakštein, E.; Balhoff, J.P. The Human Phenotype Ontology in 2024: Phenotypes around the world. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1333–D1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Obesity Federation. World Obesity Atlas 2024; World Obesity Federation: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rubino, F.; Cummings, D.E.; Eckel, R.H.; Cohen, R.V.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Brown, W.A.; Stanford, F.C.; Batterham, R.L.; Farooqi, I.S.; Farpour-Lambert, N.J. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 221–262, Erratum in Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjermeni, E.; Kirstein, A.S.; Kolbig, F.; Kirchhof, M.; Bundalian, L.; Katzmann, J.L.; Laufs, U.; Blüher, M.; Garten, A.; Le Duc, D. Obesity-An Update on the Basic Pathophysiology and Review of Recent Therapeutic Advances. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Collaborators, G.R.F. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2162–2203, Erratum in Lancet 2024, 404, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunogbe, A.; Nugent, R.; Spencer, G.; Powis, J.; Ralston, J.; Wilding, J. Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: Current and future estimates for 161 countries. BMJ Glob Health 2022, 7, e009773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battle, D.E. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Codas 2013, 25, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesulola, E.; Micalos, P.; Baguley, I.J. Understanding the pathophysiology of depression: From monoamines to the neurogenesis hypothesis model—Are we there yet? Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 341, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Fan, L.; Xia, F.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Feng, L.; Xie, S.; Xu, W.; Xie, Z.; He, J. Global, regional, and national time trends in incidence for depressive disorders, from 1990 to 2019: An age-period-cohort analysis for the GBD 2019. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2024, 23, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navío Acosta, M.; Pérez Solá, V. Depresión y Suicidio: Documento Estratégico Para la Promoción de la Salud Mental; Fundación Española de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Bruffaerts, R.; Chiu, W.T.; Florescu, S.; de Girolamo, G.; Gureje, O. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 1560–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salum, K.C.R.; Rolando, J.M.; Zembrzuski, V.M.; Carneiro, J.R.I.; Mello, C.B.; Maya-Monteiro, C.M.; Bozza, P.T.; Kohlrausch, F.B.; da Fonseca, A.C.P. When Leptin Is Not There: A Review of What Nonsyndromic Monogenic Obesity Cases Tell Us and the Benefits of Exogenous Leptin. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 722441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.S.; Loos, R.J.; McCaffery, J.M.; Ling, C.; Franks, P.W.; Weinstock, G.M.; Snyder, M.P.; Vassy, J.L.; Agurs-Collins, T.; Conference Working Group. NIH working group report-using genomic information to guide weight management: From universal to precision treatment. Obesity 2016, 24, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busebee, B.; Ghusn, W.; Cifuentes, L.; Acosta, A. Obesity: A Review of Pathophysiology and Classification. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2023, 98, 1842–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, M.; Svensson, S.I.A.; Rohde-Zimmermann, K.; Kovacs, P.; Böttcher, Y. Genetics and Epigenetics in Obesity: What Do We Know so Far? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigeyre, M.; Yazdi, F.T.; Kaur, Y.; Meyre, D. Recent progress in genetics, epigenetics and metagenomics unveils the pathophysiology of human obesity. Clin. Sci. 2016, 130, 943–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhou, D.; Xi, B.; Ge, X.; Zhu, P.; Wang, B.; Zhou, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yu, Y.; et al. ENPP1/PC-1 gene K121Q polymorphism is associated with obesity in European adult populations: Evidence from a meta-analysis involving 24,324 subjects. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2011, 24, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayling, T.M.; Timpson, N.J.; Weedon, M.N.; Zeggini, E.; Freathy, R.M.; Lindgren, C.M.; Perry, J.R.; Elliott, K.S.; Lango, H.; Rayner, N.W. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science 2007, 316, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siljee, J.E.; Wang, Y.; Bernard, A.A.; Ersoy, B.A.; Zhang, S.; Marley, A.; Von Zastrow, M.; Reiter, J.F.; Vaisse, C. Subcellular localization of MC4R with ADCY3 at neuronal primary cilia underlies a common pathway for genetic predisposition to obesity. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yengo, L.; Sidorenko, J.; Kemper, K.E.; Zheng, Z.; Wood, A.R.; Weedon, M.N.; Frayling, T.M.; Hirschhorn, J.; Yang, J.; Visscher, P.M. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in ~700,000 individuals of European ancestry. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 3641–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, E.V.; Klenotich, S.J.; McMurray, M.S.; Dulawa, S.C. Activity-Based Anorexia Alters the Expression of BDNF Transcripts in the Mesocorticolimbic Reward Circuit. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horstmann, A.; Kovacs, P.; Kabisch, S.; Boettcher, Y.; Schloegl, H.; Tönjes Stumvoll, M.; Pleger, B.; Villringer, A. Common genetic variation near MC4R has a sex-specific impact on human brain structure and eating behavior. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loos, R.J.F.; Yeo, G.S.H. The genetics of obesity: From discovery to biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.N.; Wang, Y.B.; Wnag, C.G.; Wei, H.P. Network analysis identifies common genes associated with obesity in six obesity-related diseases. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2017, 18, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh Anvar, L.; Ahmadalipour, A. Fatty acid amide hydrolase C385A polymorphism affects susceptibility to various diseases. Biofactors 2023, 49, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, M.; Greco, D.; Treccarichi, S.; Musumeci, A.; Gloria, A.; Federico, C.; Saccone, S.; Calì, F.; Sirrs, S. Investigating the role of a novel hemizygous FAAH2 variant in neurological and metabolic disorders. Gene 2025, 966, 149703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, P.; Bifulco, M.; Maina, G.; Tortorella, A.; Gazzerro, P.; Proto, M.C.; Di Filippo, C.; Monteleone, F.; Canestrelli, B.; Buonerba, G. Investigation of CNR1 and FAAH endocannabinoid gene polymorphisms in bipolar disorder and major depression. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 61, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, A.M.; García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Planelles, B.; Femenía, T.; Mingote, C.; Jiménez-Treviño, L.; Martínez-Barrondo, S.; García-Portilla, M.P.; Saiz, P.A.; Bobes, J.; et al. Association of cannabinoid receptor genes. Anxiety Stress. Coping 2020, 33, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serefko, A.; Lachowicz-Radulska, J.; Jach, M.E.; Świąder, K.; Szopa, A. The Endocannabinoid System in the Development and Treatment of Obesity: Searching for New Ideas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, T.; Boone, S.; de Mutsert, R.; Penninx, B.; Rosendaal, F.; le Cessie, S.; Milaneschi, Y.; Mook-Kanamori, D. The association between overall and abdominal adiposity and depressive mood: A cross-sectional analysis in 6459 participants. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 110, 104429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigos, C.; Chrousos, G.P. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 53, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouakinin, S.R.S.; Barreira, D.P.; Gois, C.J. Depression and Obesity: Integrating the Role of Stress, Neuroendocrine Dysfunction and Inflammatory Pathways. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niraula, A.; Wang, Y.; Godbout, J.P.; Sheridan, J.F. Corticosterone Production during Repeated Social Defeat Causes Monocyte Mobilization from the Bone Marrow, Glucocorticoid Resistance, and Neurovascular Adhesion Molecule Expression. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 2328–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardet, L.; Fève, B. Systemic glucocorticoid therapy: A review of its metabolic and cardiovascular adverse events. Drugs 2014, 74, 1731–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulton, S.; Décarie-Spain, L.; Fioramonti, X.; Guiard, B.; Nakajima, S. The menace of obesity to depression and anxiety prevalence. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 33, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D.; Doyle, W.J.; Miller, G.E.; Frank, E.; Rabin, B.S.; Turner, R.B. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5995–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, T.W.; Miller, A.H. Cytokines and glucocorticoid receptor signaling. Relevance to major depression. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2009, 1179, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juruena, M.F.; Bocharova, M.; Agustini, B.; Young, A.H. Atypical depression and non-atypical depression: Is HPA axis function a biomarker? A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 233, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Incollingo Rodriguez, A.C.; Epel, E.S.; White, M.L.; Standen, E.C.; Seckl, J.R.; Tomiyama, A.J. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation and cortisol activity in obesity: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 62, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uranga, R.M.; Keller, J.N. The Complex Interactions Between Obesity, Metabolism and the Brain. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleh, M.W.; Caslin, H.L.; Garcia, J.N.; Mashayekhi, M.; Srivastava, G.; Bradley, A.B.; Hasty, A.H. Metaflammation in obesity and its therapeutic targeting. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eadf9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Liu, S.; Zhang, C. The Related Metabolic Diseases and Treatments of Obesity. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachiya, R.; Tanaka, M.; Itoh, M.; Suganami, T. Molecular mechanism of crosstalk between immune and metabolic systems in metabolic syndrome. Inflamm. Regen. 2022, 42, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carobbio, S.; Pellegrinelli, V.; Vidal-Puig, A. Adipose Tissue Function and Expandability as Determinants of Lipotoxicity and the Metabolic Syndrome. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 960, 161–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshmane, S.L.; Kremlev, S.; Amini, S.; Sawaya, B.E. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): An overview. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009, 29, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatterale, F.; Longo, M.; Naderi, J.; Raciti, G.A.; Desiderio, A.; Miele, C.; Beguinot, F. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation Linking Obesity to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Zhao, J.; Meng, H.; Zhang, X. Adipose Tissue-Resident Immune Cells in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaneschi, Y.; Simmons, W.K.; van Rossum, E.F.C.; Penninx, B.W. Depression and obesity: Evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G.S.; Shargill, N.S.; Spiegelman, B.M. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: Direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science 1993, 259, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakers, A.; De Siqueira, M.K.; Seale, P.; Villanueva, C.J. Adipose-tissue plasticity in health and disease. Cell 2022, 185, 419–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNelis, J.C.; Olefsky, J.M. Macrophages, immunity, and metabolic disease. Immunity 2014, 41, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumeng, C.N.; DelProposto, J.B.; Westcott, D.J.; Saltiel, A.R. Phenotypic switching of adipose tissue macrophages with obesity is generated by spatiotemporal differences in macrophage subtypes. Diabetes 2008, 57, 3239–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, W.; Kumar, J.; Alghamdi, B.S.; Soliman, A.H.; Toshihide, Y. Neurodegeneration and inflammation crosstalk: Therapeutic targets and perspectives. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2023, 14, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takata, F.; Nakagawa, S.; Matsumoto, J.; Dohgu, S. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction Amplifies the Development of Neuroinflammation: Understanding of Cellular Events in Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells for Prevention and Treatment of BBB Dysfunction. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021, 15, 661838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Jo, M.; Kim, J.H.; Suk, K. Microglia-Astrocyte Crosstalk: An Intimate Molecular Conversation. Neuroscientist 2019, 25, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, N.J.; Lyons, D.A. Glia as architects of central nervous system formation and function. Science 2018, 362, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.L. Immune dysregulation and cognitive vulnerability in the aging brain: Interactions of microglia, IL-1β, BDNF and synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology 2015, 96 Pt A, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustí, A.; García-Pardo, M.P.; López-Almela, I.; Campillo, I.; Maes, M.; Romaní-Pérez, M.; Sanz, Y. Interplay Between the Gut-Brain Axis, Obesity and Cognitive Function. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.A.; Rinaman, L.; Cryan, J.F. Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiol. Stress. 2017, 7, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasset, E.; Puel, A.; Charpentier, J.; Collet, X.; Christensen, J.E.; Tercé, F.; Burcelin, R. A Specific Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis of Type 2 Diabetic Mice Induces GLP-1 Resistance through an Enteric NO-Dependent and Gut-Brain Axis Mechanism. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, S.M.; Hyland, N.P.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Maternal separation as a model of brain-gut axis dysfunction. Psychopharmacology 2011, 214, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, J.A.; Blaser, M.J.; Caporaso, J.G.; Jansson, J.K.; Lynch, S.V.; Knight, R. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Roth, S.; Llovera, G.; Sadler, R.; Garzetti, D.; Stecher, B.; Dichgans, M.; Liesz, A. Microbiota Dysbiosis Controls the Neuroinflammatory Response after Stroke. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 7428–7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.R.; Osadchiy, V.; Kalani, A.; Mayer, E.A. The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghikia, A.; Jörg, S.; Duscha, A.; Berg, J.; Manzel, A.; Waschbisch, A.; Hammer, A.; Lee, D.H.; May, C.; Wilck, N. Dietary Fatty Acids Directly Impact Central Nervous System Autoimmunity via the Small Intestine. Immunity 2015, 43, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, N.C.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Production of Psychoactive Metabolites by Gut Bacteria. Mod. Trends Psychiatry 2021, 32, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spichak, S.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Berding, K.; Vlckova, K.; Clarke, G.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Mining microbes for mental health: Determining the role of microbial metabolic pathways in human brain health and disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 125, 698–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.; Dwivedi, R.; Bansal, M.; Tripathi, M.; Dada, R. Role of Gut Microbiota in Neurological Disorders and Its Therapeutic Significance. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Tu, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, N.; Zhang, K. Gut microbiota composition in depressive disorder: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrazek, D.A.; Hornberger, J.C.; Altar, C.A.; Degtiar, I. A review of the clinical, economic, and societal burden of treatment-resistant depression: 1996–2013. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Deng, T.; Wu, M.; Zhu, A.; Zhu, G. Botanicals as modulators of depression and mechanisms involved. Chin. Med. 2019, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Südhof, T.C. The cell biology of synapse formation. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202103052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, F.H.; Samhani, I.; Mustafa, M.Z.; Shafin, N. Pathophysiology of Depression: Stingless Bee Honey Promising as an Antidepressant. Molecules 2022, 27, 5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maletic, V.; Eramo, A.; Gwin, K.; Offord, S.J.; Duffy, R.A. The Role of Norepinephrine and Its α-Adrenergic Receptors in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder and Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, A.A. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, G.E. The psychiatric side-effects of iproniazid. Am. J. Psychiatry 1956, 112, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, G.E. Further studies on iproniazid phosphate; isonicotinil-isopropyl-hydrazine phosphate marsilid. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1956, 124, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, R. The treatment of depressive states with G 22355 (imipramine hydrochloride). Am. J. Psychiatry 1958, 115, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowinski, J.; Axelrod, J. Inhibition of uptake of tritiated-noradrenaline in the intact rat brain by imipramine and structurally related compounds. Nature 1964, 204, 1318–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freis, E.D. Mental depression in hypertensive patients treated for long periods with large doses of reserpine. N. Engl. J. Med. 1954, 251, 1006–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletscher, A. The discovery of antidepressants: A winding path. Experientia 1991, 47, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, H.B.; Hwang, E.S.; Kim, E.S.; Kim, S.S.; Jeon, T.D.; Song, M.C.; Lee, J.S.; Chung, M.C.; Maeng, S.; et al. Antidepressant-like Effects of p-Coumaric Acid on LPS-induced Depressive and Inflammatory Changes in Rats. Exp. Neurobiol. 2018, 27, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhong, S.; Liao, X.; Chen, J.; He, T.; Lai, S.; Jia, Y. A Meta-Analysis of Oxidative Stress Markers in Depression. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.A.; Parrott, J.M.; McCusker, R.H.; Dantzer, R.; Kelley, K.W.; O’Connor, J.C. Intracerebroventricular administration of lipopolysaccharide induces indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase-dependent depression-like behaviors. J. Neuroinflamm. 2013, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, R.; O’Connor, J.C.; Freund, G.G.; Johnson, R.W.; Kelley, K.W. From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucci, F.; Marazziti, D.; Della Vecchia, A.; Baroni, S.; Morana, P.; Carpita, B.; Mangiapane, P.; Morana, F.; Morana, B.; Dell’Osso, L. State-of-the-Art: Inflammatory and Metabolic Markers in Mood Disorders. Life 2020, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, M.; Kubera, M.; Leunis, J.C.; Berk, M. Increased IgA and IgM responses against gut commensals in chronic depression: Further evidence for increased bacterial translocation or leaky gut. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flinkkilä, E.; Keski-Rahkonen, A.; Marttunen, M.; Raevuori, A. Prenatal Inflammation, Infections and Mental Disorders. Psychopathology 2016, 49, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, G.R.; Saldana, V.A.; Finnstein, J.; Rein, T. Molecular pathways of major depressive disorder converge on the synapse. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, R.; Cassar, D. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor—Major Depressive Disorder and Suicide. Open Access Libr. J. 2019, 6, 5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkholm, C.; Monteggia, L.M. BDNF—A key transducer of antidepressant effects. Neuropharmacology 2016, 102, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheleznyakova, G.Y.; Cao, H.; Schiöth, H.B. BDNF DNA methylation changes as a biomarker of psychiatric disorders: Literature review and open access database analysis. Behav. Brain Funct. 2016, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numakawa, T.; Odaka, H.; Adachi, N. Actions of Brain-Derived Neurotrophin Factor in the Neurogenesis and Neuronal Function, and Its Involvement in the Pathophysiology of Brain Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.J.; Song, Z.J.; Wang, X.C.; Zhang, Z.R.; Wu, S.B.; Zhu, G.Q. Curculigoside facilitates fear extinction and prevents depression-like behaviors in a mouse learned helplessness model through increasing hippocampal BDNF. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2019, 40, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Q.; Li, C.F.; Chen, S.J.; Liang, W.N.; Wang, M.; Wang, S.S.; Dong, S.Q.; Yi, L.T.; Li, C.D. The antidepressant-like effects of Chaihu Shugan San: Dependent on the hippocampal BDNF-TrkB-ERK/Akt signaling activation in perimenopausal depression-like rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 105, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, H.Y.; Wang, Q.; Lu, W.Y.; Ju, W.; Ahmadian, G.; Liu, L.; D’Souza, S.; Wong, T.P.; Taghibiglou, C.; Lu, J. Activation of PI3-kinase is required for AMPA receptor insertion during LTP of mEPSCs in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron 2003, 38, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandy, K.; Kim, S.; Sharp, C.; Dindo, L.; Maletic-Savatic, M.; Calarge, C. Pattern Separation: A Potential Marker of Impaired Hippocampal Adult Neurogenesis in Major Depressive Disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, F.A.; Vollmayr, B. Neurogenesis and depression: Etiology or epiphenomenon? Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 56, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, D.J.; Samuels, B.A.; Rainer, Q.; Wang, J.W.; Marsteller, D.; Mendez, I.; Drew, M.; Craig, D.A.; Guiard, B.P.; Guilloux, J.P. Neurogenesis-dependent and -independent effects of fluoxetine in an animal model of anxiety/depression. Neuron 2009, 62, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, N.D.; Owens, M.J.; Nemeroff, C.B. Depression, antidepressants, and neurogenesis: A critical reappraisal. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 36, 2589–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbins, E.; Walter, S.; Becker, K.A.; Halmer, R.; Liu, Y.; Reichel, M.; Edwards, M.J.; Müller, C.P.; Fassbender, K.; Kornhuber, J. A central role for the acid sphingomyelinase/ceramide system in neurogenesis and major depression. J. Neurochem. 2015, 134, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Huang, C.; Chen, X.F.; Tong, L.J.; Zhang, W. Tetramethylpyrazine Produces Antidepressant-Like Effects in Mice Through Promotion of BDNF Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 18, pyv010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autry, A.E.; Adachi, M.; Nosyreva, E.; Na, E.S.; Los, M.F.; Cheng, P.F.; Kavalali, E.T.; Monteggia, L.M. NMDA receptor blockade at rest triggers rapid behavioural antidepressant responses. Nature 2011, 475, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.C.; Yao, W.; Hashimoto, K. Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF)-TrkB Signaling in Inflammation-related Depression and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Raison, C.L. The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanon, N.; Lasselin, J.; Capuron, L. Neuropsychiatric comorbidity in obesity: Role of inflammatory processes. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liukkonen, T.; Räsänen, P.; Jokelainen, J.; Leinonen, M.; Järvelin, M.R.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B.; Timonen, M. The association between anxiety and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels: Results from the Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort study. Eur. Psychiatry 2011, 26, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, R.J.; Khambaty, T.; Stewart, J.C. C-reactive protein is elevated in atypical but not nonatypical depression: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. J. Behav. Med. 2014, 37, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Kokoeva, M.V.; Inouye, K.; Tzameli, I.; Yin, H.; Flier, J.S. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernstedt Asterholm, I.; Tao, C.; Morley, T.S.; Wang, Q.A.; Delgado-Lopez, F.; Wang, Z.V.; Scherer, P.E. Adipocyte inflammation is essential for healthy adipose tissue expansion and remodeling. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, B.J.; Contreras, G.A. Adipose Tissue Inflammation: Linking Physiological Stressors to Disease Susceptibility. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 12, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, R.; Neeland, I.J.; Yamashita, S.; Shai, I.; Seidell, J.; Magni, P.; Santos, R.D.; Arsenault, B.; Cuevas, A.; Hu, F.B. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: A Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Anderson, D.; Lurie-Beck, J. The relationship between abdominal obesity and depression in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2011, 5, e267–e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hryhorczuk, C.; Florea, M.; Rodaros, D.; Poirier, I.; Daneault, C.; Des Rosiers, C.; Arvanitogiannis, A.; Alquier, T.; Fulton, S. Dampened Mesolimbic Dopamine Function and Signaling by Saturated but not Monounsaturated Dietary Lipids. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.M.; Caldas, A.P.; Oliveira, L.L.; Bressan, J.; Hermsdorff, H.H. Saturated fatty acids trigger TLR4-mediated inflammatory response. Atherosclerosis 2016, 244, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, W.A. The blood-brain barrier in neuroimmunology: Tales of separation and assimilation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanada, K.; Nakajima, S.; Kurokawa, S.; Barceló-Soler, A.; Ikuse, D.; Hirata, A.; Yoshizawa, A.; Tomizawa, Y.; Salas-Valero, M.; Noda, Y. Gut microbiota and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.; Herzog, C.; Pacheco, J.A.; Fujisaka, S.; Bullock, K.; Clish, C.B.; Kahn, C.R. Gut microbiota modulate neurobehavior through changes in brain insulin sensitivity and metabolism. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 2287–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, C.; Bell, R.; Klag, K.A.; Lee, S.H.; Soto, R.; Ghazaryan, A.; Buhrke, K.; Ekiz, H.A.; Ost, K.S.; Boudina, S. T cell-mediated regulation of the microbiota protects against obesity. Science 2019, 365, eaat9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 873–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rossum, E.F. Obesity and cortisol: New perspectives on an old theme. Obesity 2017, 25, 500–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallman, M.F. Stress-induced obesity and the emotional nervous system. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 21, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo, R. Depression and inflammation: A relationship beyond random? Rev. Med. Clin. Condes. 2020, 32, 188–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kushner, P.; Kahan, S.; McIntyre, R.S. Treating obesity in patients with depression: A narrative review and treatment recommendation. Postgrad. Med. 2025, 137, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monsalve, F.A.; Fernández-Tapia, B.; Arriagada, O.C.; González, D.R.; Delgado-López, F. Obesity and Depression: A Pathophysiotoxic Relationship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311590

Monsalve FA, Fernández-Tapia B, Arriagada OC, González DR, Delgado-López F. Obesity and Depression: A Pathophysiotoxic Relationship. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311590

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonsalve, Francisco A., Barbra Fernández-Tapia, Oscar C. Arriagada, Daniel R. González, and Fernando Delgado-López. 2025. "Obesity and Depression: A Pathophysiotoxic Relationship" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311590

APA StyleMonsalve, F. A., Fernández-Tapia, B., Arriagada, O. C., González, D. R., & Delgado-López, F. (2025). Obesity and Depression: A Pathophysiotoxic Relationship. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311590