- Article

Estimating H I Mass Fraction in Galaxies with Bayesian Neural Networks

- Joelson Sartori,

- Cristian G. Bernal and

- Carlos Frajuca

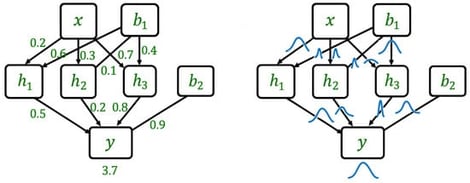

Neutral atomic hydrogen (H I) regulates galaxy growth and quenching, but direct 21 cm measurements remain observationally expensive and affected by selection biases. We develop Bayesian neural networks (BNNs)—a type of neural model that returns both a prediction and an associated uncertainty—to infer the H I mass, , from widely available optical properties (e.g., stellar mass, apparent magnitudes, and diagnostic colors) and simple structural parameters. For continuity with the photometric gas fraction (PGF) literature, we also report the gas-to-stellar-mass ratio, , where explicitly noted. Our dataset is a reproducible cross-match of SDSS DR12, the MPA–JHU value-added catalogs, and the 100% ALFALFA release, resulting in 31,501 galaxies after quality controls. To ensure fair evaluation, we adopt fixed train/validation/test partitions and an additional sky-holdout region to probe domain shift, i.e., how well the model extrapolates to sky regions that were not used for training. We also audit features to avoid information leakage and benchmark the BNNs against deterministic models, including a feed-forward neural network baseline and gradient-boosted trees (GBTs, a standard tree-based ensemble method in machine learning). Performance is assessed using mean absolute error (MAE), root-mean-square error (RMSE), and probabilistic diagnostics such as the negative log-likelihood (NLL, a loss that rewards models that assign high probability to the observed H I masses), reliability diagrams (plots comparing predicted probabilities to observed frequencies), and empirical 68%/95% coverage. The Bayesian models achieve point accuracy comparable to the deterministic baselines while additionally providing calibrated prediction intervals that adapt to stellar mass, surface density, and color. This enables galaxy-by-galaxy uncertainty estimation and prioritization for 21 cm follow-up that explicitly accounts for predicted uncertainties (“risk-aware” target selection). Overall, the results demonstrate that uncertainty-aware machine-learning methods offer a scalable and reproducible route to inferring galactic H I content from widely available optical data.

2 February 2026

![(Top): the light curve of TV UMi. The phase-binned TESS observations are plotted as green circles, and the best-fitting model (detailed in Table 2) is plotted as a black line. The circle size is indicative of the mean observational error (≈0.0004). (Bottom): the velocity curves of TV UMi. The observed radial velocities from Pribulla et al. [6] are plotted as red dots for the primary, and as blue dots for the secondary star, and the best-fitting model is plotted as a black line. The residuals between the observations and the model are shown below the corresponding plots.](https://mdpi-res.com/cdn-cgi/image/w=281,h=192/https://mdpi-res.com/galaxies/galaxies-14-00009/article_deploy/html/images/galaxies-14-00009-g001-550.jpg)