On the Analysis Dependence of DESI Dynamical Dark Energy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Analysis

3. Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Methodology Check

| 1 | |

| 2 | See [24] for a manifestation of the anti-correlated trends. |

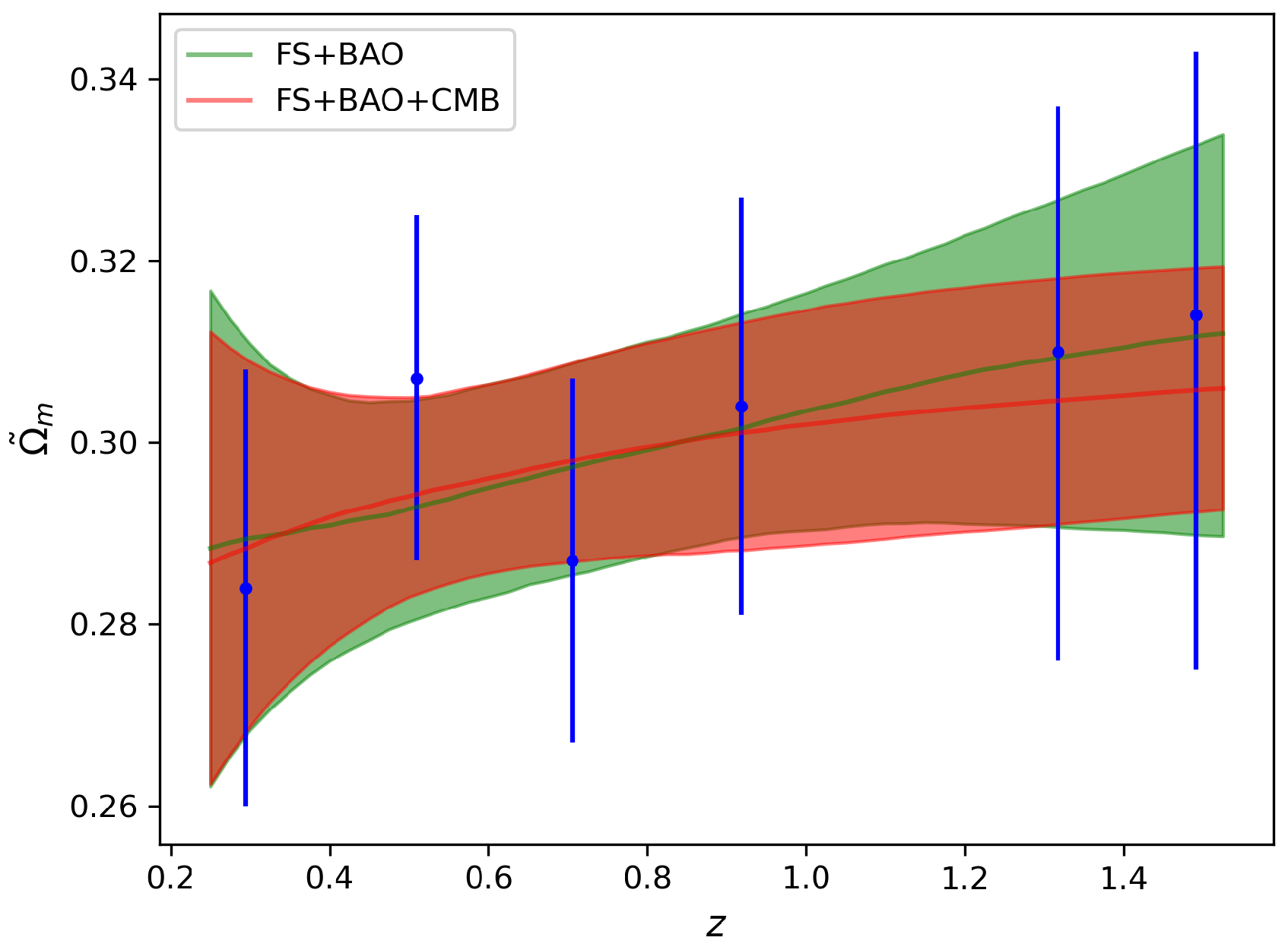

| 3 | Concretely, decreasing with redshift, increasing with redshift and increasing with redshift. |

| 4 |

References

- Adame, A.G.; Aguilar, J.; Ahlen, S.; Alam, S.; Alexander, D.M.; Alvarez, M.; Alves, O.; Anand, A.; Andrade, U.; Armengaud, E.; et al. DESI 2024 VI: Cosmological constraints from the measurements of baryon acoustic oscillations. JCAP 2025, 02, 021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adame, A.G.; Aguilar, J.; Ahlen, S.; Alam, S.; Alexander, D.M.; Prieto, C.A.; Alvarez, M.; Alves, O.; Anand, A.; Andrade, U.; et al. DESI 2024 VII: Cosmological Constraints from the Full-Shape Modeling of Clustering Measurements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Karim, M.; Aguilar, J.; Ahlen, S.; Alam, S.; Alexander, D.M.; Prieto, C.A.; Alvarez, M.; Alves, O.; Anand, A.; Andrade, U.; et al. DESI DR2 Results II: Measurements of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations and Cosmological Constraints. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.14738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adame, A.G.; Aguilar, J.; Ahlen, S.; Alam, S.; Alexander, D.M.; Prieto, C.A.; Alvarez, M.; Alves, O.; Anand, A.; Andrade, U.; et al. DESI 2024 V: Full-Shape Galaxy Clustering from Galaxies and Quasars. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghanim, N.; Miville-Deschênes, M.A.; Pettorino, V.; Bucher, M.; Delabrouille, J.; Ganga, K.; Le Jeune, M.; Patanchon, G.; Rosset, C.; Roudier, G.; et al. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6, Erratum in Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 652, C4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Colgáin, E.; Dainotti, M.G.; Capozziello, S.; Pourojaghi, S.; Sheikh-Jabbari, M.M.; Stojkovic, D. Does DESI 2024 confirm ΛCDM? JHEAp 2026, 49, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, B.R. A new diagnostic for the null test of dynamical dark energy in light of DESI 2024 and other BAO data. JCAP 2024, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, S.; Ding, Z.; Hu, B. The role of LRG1 and LRG2’s monopole in inferring the DESI 2024 BAO cosmology. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2024, 534, 3869–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudaykin, A.; Kunz, M. Modified gravity interpretation of the evolving dark energy in light of DESI data. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, 123524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, W. Impact of LRG1 and LRG2 in DESI 2024 BAO data on dark energy evolution. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.04385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilardi, S.; Capozziello, S.; Brescia, M. Discriminating among cosmological models by data-driven methods. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.01563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapone, D.; Nesseris, S. Outliers in DESI BAO: Robustness and cosmological implications. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.01740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, M.; Polarski, D. Accelerating universes with scaling dark matter. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2001, 10, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, E.V. Exploring the expansion history of the universe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 90, 091301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawetz, J.; Zhang, H.; Bonici, M.; Percival, W.; Crespi, A.; Aguilar, J.N.; Ahlen, S.; Bianchi, D.; Brooks, D.; Castander, F.J.; et al. Frequentist Cosmological Constraints from Full-Shape Clustering Measurements in DESI DR1. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.11811. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Colgáin, E.; Pourojaghi, S.; Sheikh-Jabbari, M.M.; Yin, L. How much has DESI dark energy evolved since DR1? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.04417, 4417. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Colgáin, E.; Sheikh-Jabbari, M.M. DESI and SNe: Dynamical dark energy, Ωm tension or systematics? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Lett. 2025, 542, L24–L30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, V.; Shafieloo, A.; Starobinsky, A.A. Two new diagnostics of dark energy. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 78, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman-Mackey, D.; Hogg, D.W.; Lang, D.; Goodman, J. emcee: The MCMC Hammer. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2013, 125, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A. GetDist: A Python package for analysing Monte Carlo samples. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.13970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. The Self-Consistency of DESI Analysis and Comment on “Does DESI 2024 Confirm ΛCDM?”. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.13833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Mota, D. Did DESI DR2 truly reveal dynamical dark energy? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.15222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, H.; Wu, P. Revisiting cosmic acceleration with DESI BAO. Eur. Phys. J. C 2025, 85, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Colgáin, E.; Pourojaghi, S.; Sheikh-Jabbari, M.M. Implications of DES 5YR SNe Dataset for ΛCDM. Eur. Phys. J. C 2025, 85, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Valentino, E.; Said, J.L.; Riess, A.; Pollo, A.; Poulin, V.; Gómez-Valent, A.; Weltman, A.; Palmese, A.; Huang, C.D.; van de Bruck, C.; et al. The CosmoVerse White Paper: Addressing observational tensions in cosmology with systematics and fundamental physics. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.01669. [Google Scholar]

- Akarsu, O.; Ó Colgáin, E.; Sen, A.A.; Sheikh-Jabbari, M.M. ΛCDM Tensions: Localising Missing Physics through Consistency Checks. Universe 2024, 10, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.; Sen, A.A. Model-Agnostic Cosmological Inference with SDSS-IV eBOSS: Simultaneous Probing for Background and Perturbed Universe. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.13973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.M.; Giarè, W.; Hogg, N.B.; Montandon, T.; Poudou, A.; Poulin, V. Implications of distance duality violation for the H0 tension and evolving dark energy. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.10464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, S.; Mukherjee, S. Hint towards inconsistency between BAO and Supernovae Dataset: The Evidence of Redshift Evolving Dark Energy from DESI DR2 is Absent. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.16868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Valent, A. Fast test to assess the impact of marginalization in Monte Carlo analyses and its application to cosmology. Phys. Rev. D 2022, 106, 063506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Colgáin, E.; Pourojaghi, S.; Sheikh-Jabbari, M.M.; Sherwin, D. A comparison of Bayesian and frequentist confidence intervals in the presence of a late Universe degeneracy. Eur. Phys. J. C 2025, 85, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, S.S. The Large-Sample Distribution of the Likelihood Ratio for Testing Composite Hypotheses. Annals Math. Statist. 1938, 9, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Colgáin, E.; Sheikh-Jabbari, M.M.; Yin, L. Do high redshift QSOs and GRBs corroborate JWST? Phys. Dark Univ. 2025, 49, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotta, R. Bayesian Methods in Cosmology. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1701.01467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tracer | ||

|---|---|---|

| BGS | ||

| LRG1 | ||

| LRG2 | ||

| LRG3 | ||

| ELG2 | ||

| QSO |

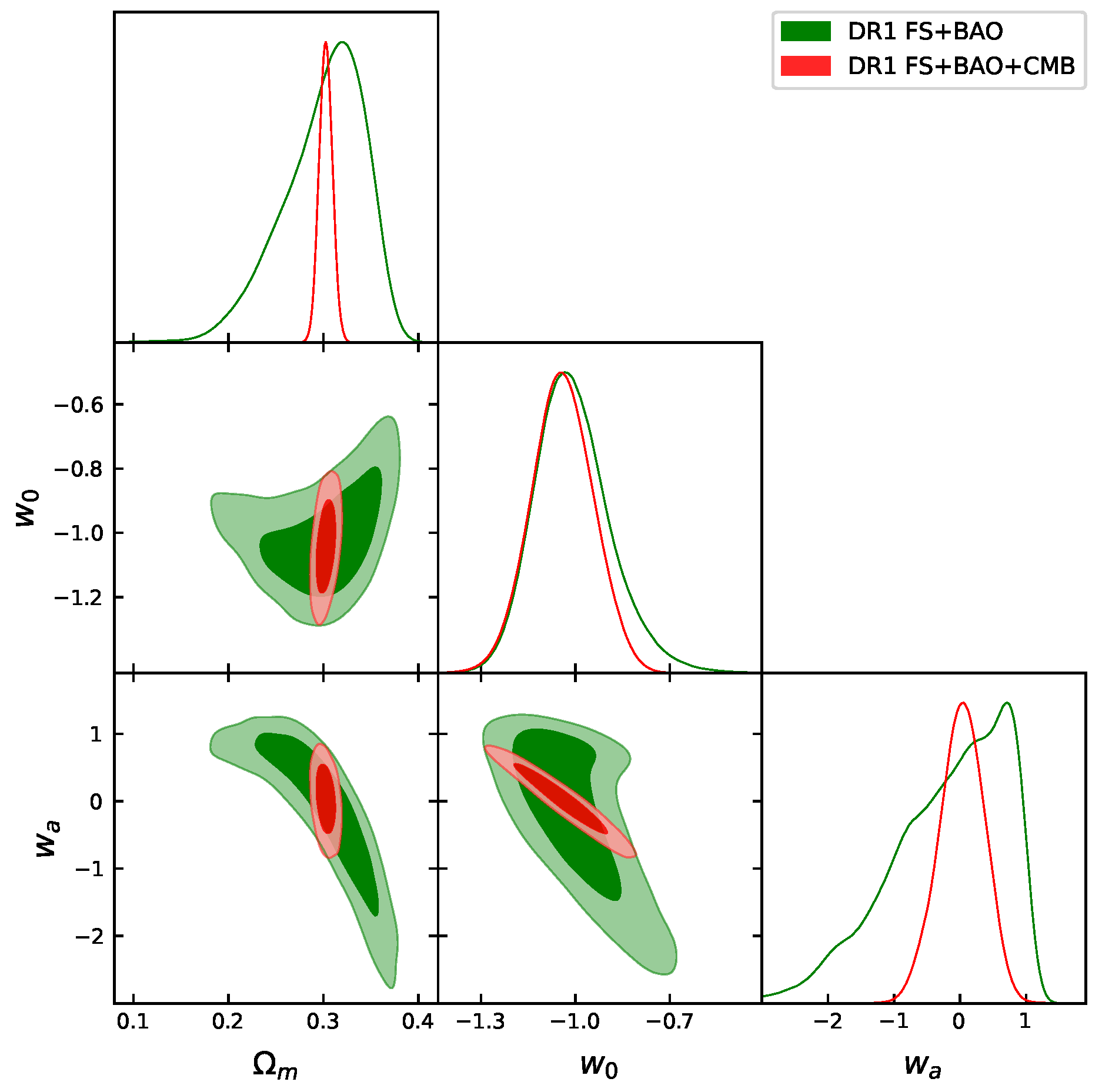

| Data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS + BAO | ||||

| FS + BAO + CMB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ó Colgáin, E.; Pourojaghi, S.; Sheikh-Jabbari, M.M. On the Analysis Dependence of DESI Dynamical Dark Energy. Galaxies 2025, 13, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060133

Ó Colgáin E, Pourojaghi S, Sheikh-Jabbari MM. On the Analysis Dependence of DESI Dynamical Dark Energy. Galaxies. 2025; 13(6):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060133

Chicago/Turabian StyleÓ Colgáin, Eoin, Saeed Pourojaghi, and M. M. Sheikh-Jabbari. 2025. "On the Analysis Dependence of DESI Dynamical Dark Energy" Galaxies 13, no. 6: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060133

APA StyleÓ Colgáin, E., Pourojaghi, S., & Sheikh-Jabbari, M. M. (2025). On the Analysis Dependence of DESI Dynamical Dark Energy. Galaxies, 13(6), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060133