On the Origin and Nature of Double-Double Radio Galaxies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Double-Double Radio Galaxies

2.1. Double-Double Radio Galaxies–Observations

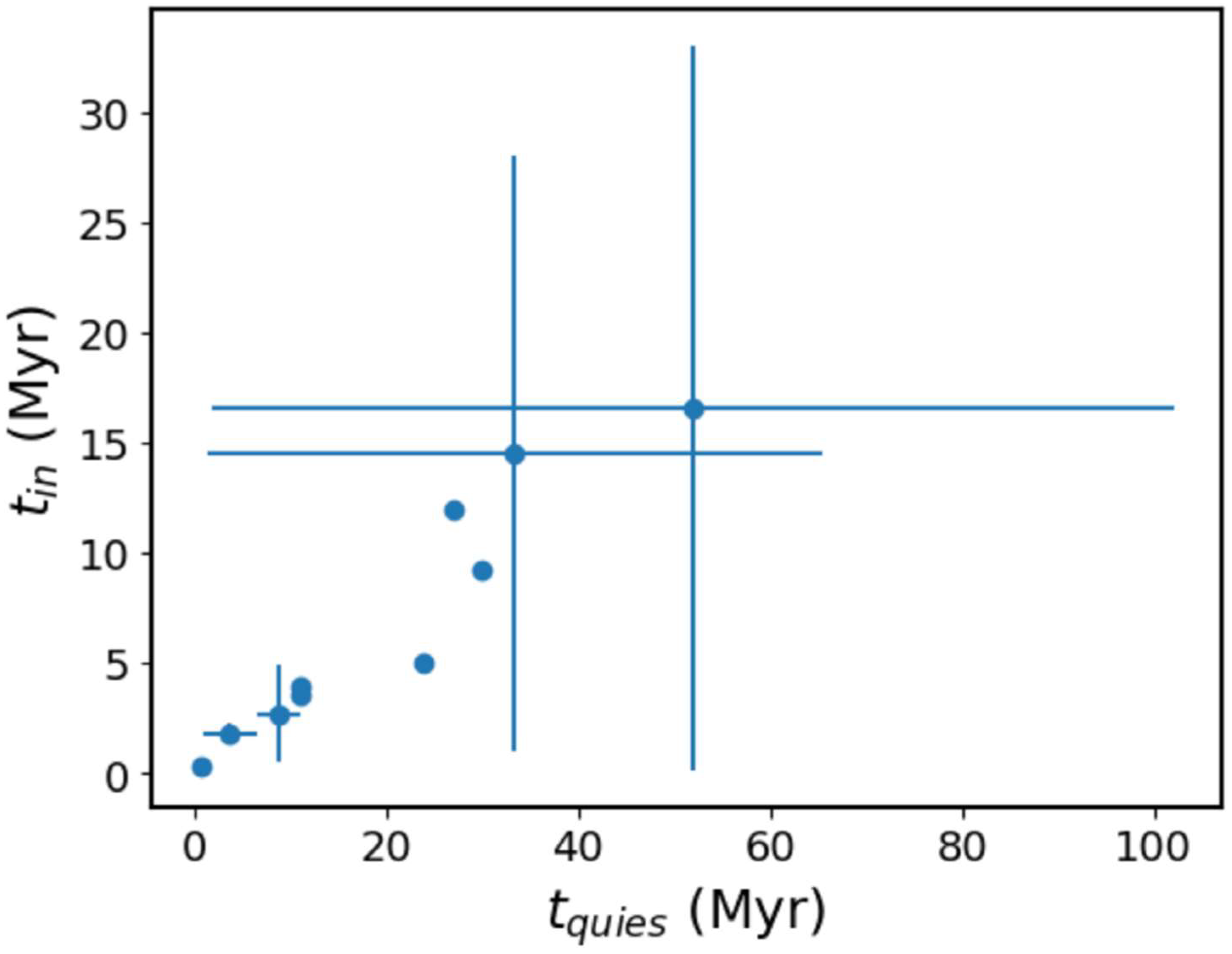

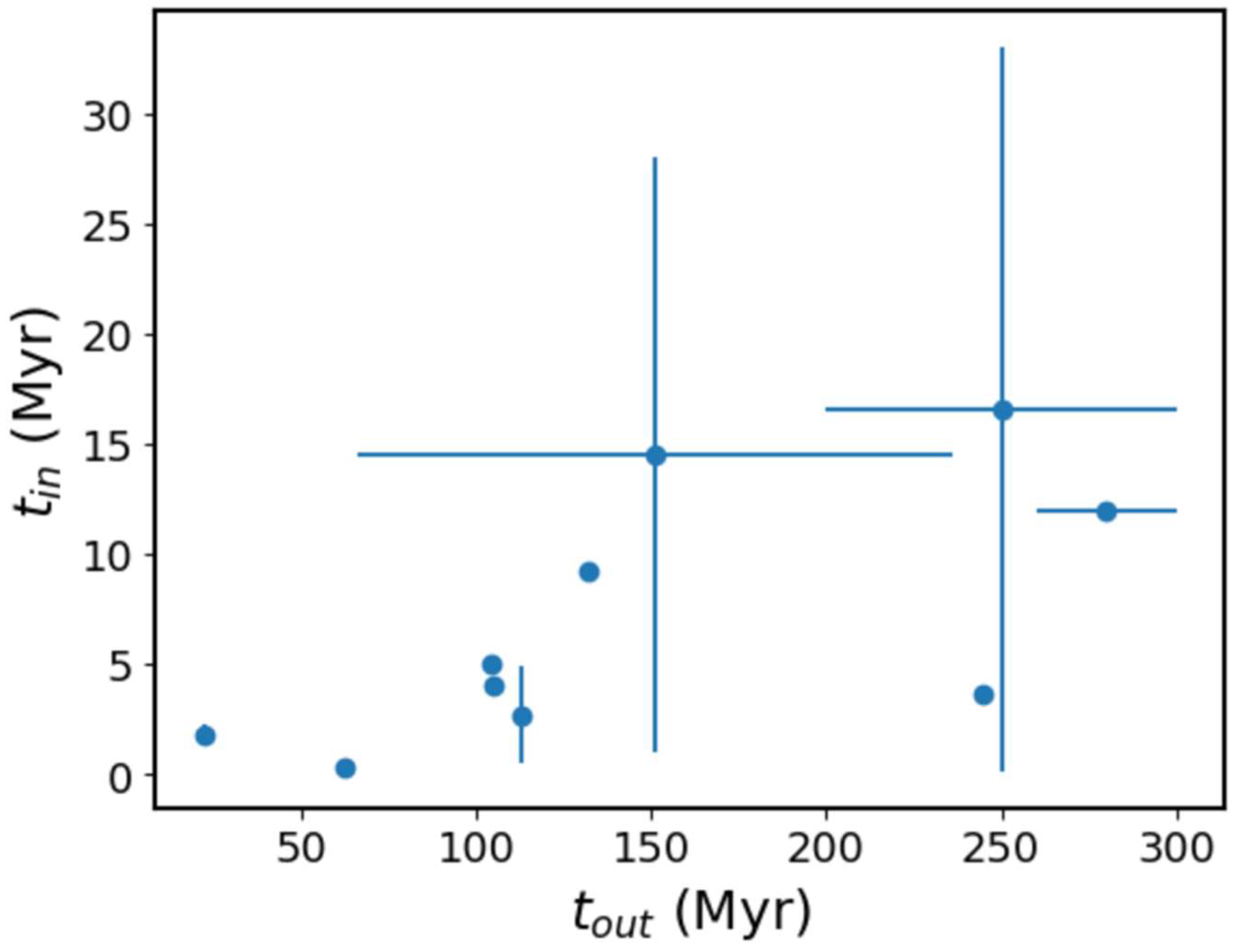

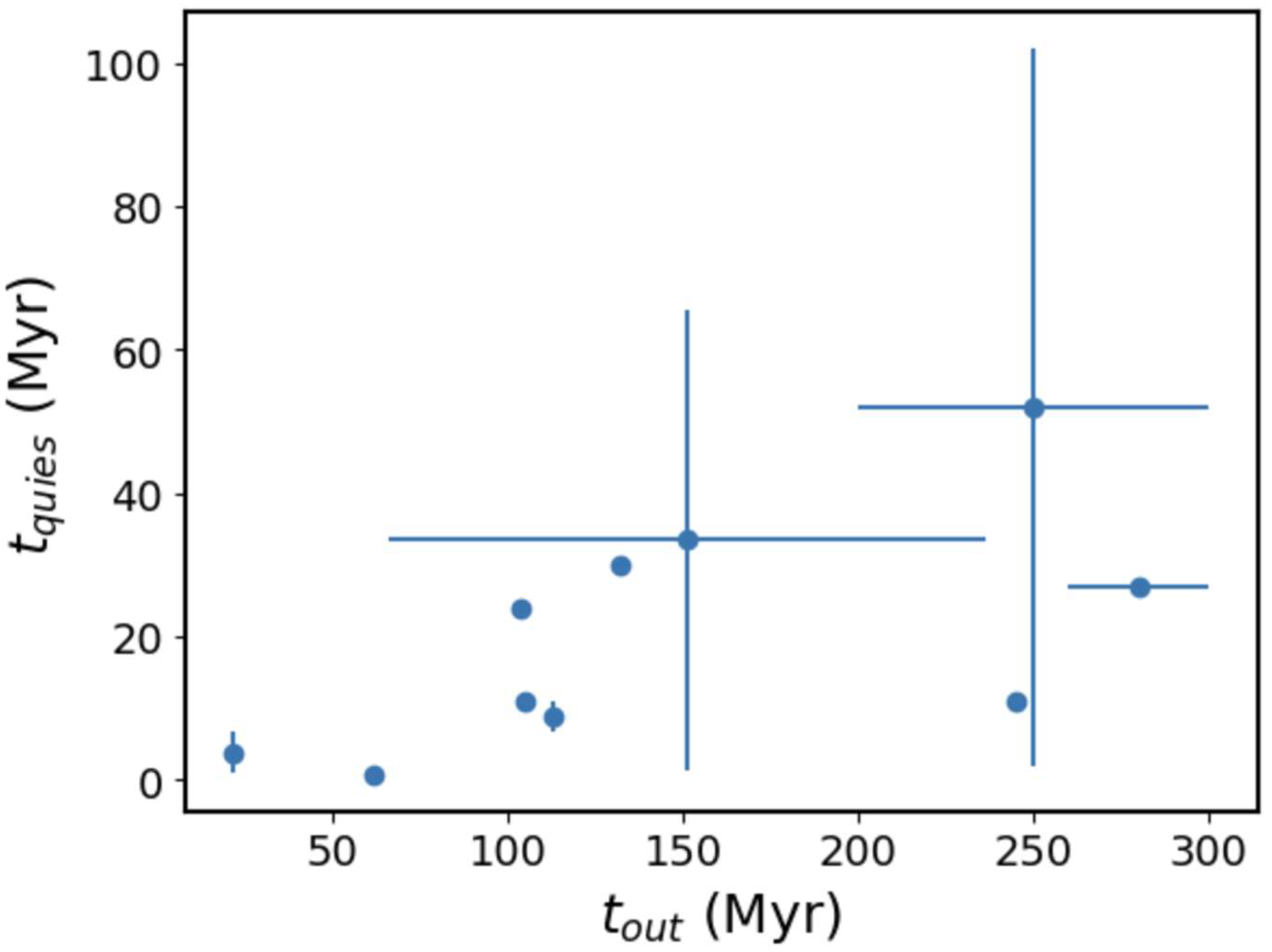

| Source Name | Z | tin (Myrs.) | tout (Myrs.) | tquies (Myrs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| J0028+0035 | 0.3985 | 3.6 | 245 | 11 |

| J0041+3224 | 0.45 | 4.0 | 105 | 11 |

| J0116-4722 | 0.1461 | 1–28 | 66–236 | 1.4–65.4 |

| J0840+2949 | 0.0647 | 0.12–33 | >200 | 2.0–102.0 |

| J1158+2621 | 0.1121 | 0.5–4.9 | 113 | 6.6–11.0 |

| J1352+3126 | 0.045 | 0.3 | 62 | 0.7 |

| J1453+3308 | 0.2482 | 5.0 | 104 | 24 |

| J1548-3216 | 0.1082 | 9.2 | 132 | 30 |

| J1706+4340 | 0.525 | 12 | 260–300 | 27 |

| J1835+6204 | 0.5194 | 1.34–2.25 | 22 | 1.0–6.6 |

| J0921+4538 (3C 219) | 0.1747 | 0.15 | N/A | 0.5 |

| J1844+455 (3C 388) | 0.091 | 6 | N/A | 4 |

2.2. Double-Double Radio Galaxies–Theory

2.2.1. Timescale of Jet Quiescence

2.2.2. Origin of the Time Correlation

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schoenmakers, A.P.; de Bruyn, A.G.; Rottgering, H.J.A.; van der Laan, H.; Kaiser, C.R. Radio galaxies with a ‘double-double morphology’ - I. Analysis of the radio properties and evidence for interrupted activity in active galactic nuclei. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2000, 315, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, A.C. Observational Evidence of Active Galactic Nuclei Feedback. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 50, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moderski, R.; Sikora, M.; Lasota, J.-P. On the spin paradigm and the radio dichotomy of quasars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1998, 301, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.S.; Colbert, E.J.M. The Difference between Radio-loud and Radio-quiet Active Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 1995, 438, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, M.; Stawarz, L.; Lasota, J.-P. Radio Loudness of Active Galactic Nuclei: Observational Facts and Theoretical Implications. Astrophys. J. 2007, 658, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, D.J.; Jamrozy, M. Recurrent activity in Active Galactic Nuclei. Bull. Astron. Soc. India 2009, 37, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmicz, A.; Jamrozy, M.; Koziel-Wierzbowska, D.; Wezgowiec, M. Optical and radio properties of extragalactic radio sources with recurrent jet activity. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 471, 3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahatma, V.H.; Hardcastle, M.J.; Williams, W.L.; Best, P.N.; Croston, J.H.; Duncan, K.; Mingo, B.; Morganti, R.; Brienza, M.; Cochrane, R.K.; et al. LoTSS DR1: Double-double radio galaxies in the HETDEX field. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 622, A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marecki, A.; Jamrozy, M.; Machalski, J.; Pajdosz-Smierciak, U. Multifrequency study of a double-double radio galaxy J0028+0035. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 501, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, C.; Hardcastle, M.J.; Jamrozy, M.; Croston, J.H.; Nandi, S. Rejuvenated radio galaxies J0041+3224 and J1835+6204: How long can the quiescent phase of nuclear activity last? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 424, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanaroff, B.L.; Riley, J.M. The morphology of extragalactic radio sources of high and low luminosity. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1974, 167, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, D.; Joshi, R.; Yang, X.; Singh, C.B.; North, M.; Hopkins, M. A Unified Framework for X-shaped Radio Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2020, 889, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.B.; Williams, M.; Garofalo, D.; Rojas-Castillo, L.; Taylor, L.; Harmon, E. Characteristics of Powerful Radio Galaxies. Universe 2024, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.B.; Garofalo, D. The massive black holes, high accretion rates, and non-tilted jet feedback, of jetted AGN triggered by secular processes. High Energy Astrophys. 2023, 39, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrù, E.; Van Velzen, S.; Pizzo, R.F.; Yatawatta, S.; Paladino, R.; Iacobelli, M.; Murgia, M.; Falcke, H.; Morganti, R.; De Bruyn, A.G.; et al. Wide-field LOFAR imaging of the field around the double-double radio galaxy B1834+620. A fresh view on a restarted AGN and doubeltjes. Astron. Astrophys. 2015, 584, A112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brienza, M.; Morganti, R.; Harwood, J.; Duchet, T.; Rajpurohit, K.; Shulevski, A.; Hardcastle, M.J.; Mahatma, V.; Godfrey, L.E.H.; Prandoni, I.; et al. Radio spectral properties and jet duty cycle in the restarted radio galaxy 3C388. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 638, A29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolnik, K.; Jurusik, W.; Jamrozy, M. Spectral aging analysis of the 3C 219 double-double radio galaxy. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 691, A76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machalski, J.; Jamrozy, M.; Stawarz, Ł.; Kozieł-Wierzbowska, D. Understanding Giant Radio Galaxy J1420-0545: Large-scale Morphology, Environment, and Energetics. Astrophys. J. 2011, 740, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, C.; Hardcastle, M.J.; Jamrozy, M.; Croston, J.H. Episodic radio galaxies J0116-4722 and J1158+2621: Can we constrain the quiescent phase of nuclear activity? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 430, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrozy, M.; Konar, C.; Saikia, D.J.; Stawarz, Ł.; Mack, K.-H.; Siemiginowska, A. Intermittent jet activity in the radio galaxy 4C29.30? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2007, 378, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machalski, J.; Jamrozy, M.; Stawarz, Ł.; Wezgowiec, M. Dynamical analysis of the complex radio structure in 3C 293: Clues on a rapid jet realignment in X-shaped radio galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 2016, 595, A46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marecki, A.; Jamrozy, M.; Machalski, J. Multifrequency study of a double-double radio galaxy J1706+4340. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 463, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, C.; Hardcastle, M.J. Particle acceleration and dynamics of double-double radio galaxies: Theory versus observations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 436, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocksopp, C.; Kaiser, C.R.; Schoenmakers, A.P.; de Bruyn, A.G. Double-double radio galaxies: Further insights into the formation of the radio structures. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2011, 410, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.I.; Christian, D.J.; Garofalo, D.; D’Avanzo, J. Possible evolution of supermassive black holes from FRI quasars. Mon.Not.R.Astron.Soc 2016, 460, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.M.; Press, W.H.; Teukolsky, S.A. Rotating Black Holes: Locally Nonrotating Frames, Energy Extraction, and Scalar Synchrotron Radiation. Astrophys. J. 1972, 178, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, C.P.; Saikia, D.J. Compact steep-spectrum and peaked-spectrum radio sources. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 2021, 29, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, C.P.; Koekemoer, A.M.; Baum, S.A.; Sparks, W.B.; Martel, A.R.; Allen, M.G.; Macchetto, F.D.; Miley, G.K. 3C 236: Radio Source, Interrupted? Astron. J. 2001, 121, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulevski, A.; Morganti, R.; Oosterloo, T.; Struve, C. Recurrent radio emission and gas supply: The radio galaxy B2 0258+35. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 545, A91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.A.; Nandi, S.; Saikia, D.J.; Ishwara-Chandra, C.H.; Konar, C.J. The Double–Double Radio Galaxy 3C293. Astrophys. Astron. 2011, 32, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, D.; Evans, D.A.; Sambruna, R.M. The evolution of radio-loud active galactic nuclei as a function of black hole spin. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2010, 406, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridle, A.H.; Perley, R.A. Extragalactic Radio Jets. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 1984, 22, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, D.J.J. Jets in radio galaxies and quasars: An observational perspective. Astrophys. Astr. 2022, 43, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, D. The Spin Dependence of the Blandford-Znajek Effect. Astrophys. J. 2009, 699, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, D.; Moravec, E.; Macconi, D.; Singh, C.B. Is Jet Re-orientation the Elusive Trigger for Star Formation Suppression in Radio Galaxies? Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac 2022, 134, 114101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocksopp, C.; Kaiser, C.R.; Schoenmakers, A.P.; de Bruyn, A.G. Three episodes of jet activity in the Fanaroff-Riley type II radio galaxy B0925+420. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2007, 382, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerny, B.; Siemiginowska, A.; Janiuk, A.; Nikiel-Wroczynski, B.; Stawarz, L. Accretion Disk Model of Short-Timescale Intermittent Activity in Young Radio Sources. Astrophys. J. 2009, 698, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Garofalo, D.; Liu, Z.; Magerko, A.V. On the Origin and Nature of Double-Double Radio Galaxies. Galaxies 2026, 14, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies14010002

Garofalo D, Liu Z, Magerko AV. On the Origin and Nature of Double-Double Radio Galaxies. Galaxies. 2026; 14(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies14010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarofalo, David, Zhiyuan Liu, and Atticus V. Magerko. 2026. "On the Origin and Nature of Double-Double Radio Galaxies" Galaxies 14, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies14010002

APA StyleGarofalo, D., Liu, Z., & Magerko, A. V. (2026). On the Origin and Nature of Double-Double Radio Galaxies. Galaxies, 14(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies14010002